Abstract

People with Disabilities (PwDs) suffer and are susceptible to social inequalities, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. In West Africa, these are influenced by how services geared towards PwDs are administered. This study explores the government policies implemented in West Africa during the Covid-19 pandemic and their impact on PwDs in line with the SDGs with disability targets. Thematic analysis was adopted to analyze eighty-one (81) documents, including legislation, reports and official documents that communicated measures taken in response to Covid-19 and SDGs with disability targets. The study found that various governments outlined pragmatic steps to address the needs of PwDs. It was unraveled that the policies and recommendations that the governments have published on disability inclusiveness in response to Covid-19 did not reflected in the lives PwDs. This is evident based on the difficulty PwDs have to go through to access all the available benefits. It takes a while to see such policies and recommendations reflected in the lives of PwDs. Measuring the expected improvements in the lives of PwDs relative to the SGD’s attainment can not happen overnight. This study is the first of its kind in West Africa and urges various governments to pay close attention to their policies to improve their policies toward PwDs. The study recognizes governments’ vital role in ensuring that PwDs are better off, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the government needs to provide adequate education on how PwDs will readily access policies to better their lives.

Public Interest Statement

Globally, People with Disabilities (PwDs) continue to suffer from discrimination. Various governments have shown efforts by enacting policies to better the lives of PwDs. Most governments have a target to achieve SDGs by 2030, and issues of disability inclusiveness cannot be overlooked. In the wake of the novel Covid-19, these policies and recommendations have not reflected in the lives of PwDs. Thus, these policies and recommendations do not necessarily translate to action. Several barriers and inherent structural inequities prevent individuals with disabilities from accessing necessary support (education, health, employment, food security, etc.). The study emphasizes the need for governments to realize that policy action does not necessarily translate equitably. There is a responsibility to consider inequities faced by vulnerable populations who already face intersecting barriers, then emergencies happen, and these inequities are magnified.

1. Introduction

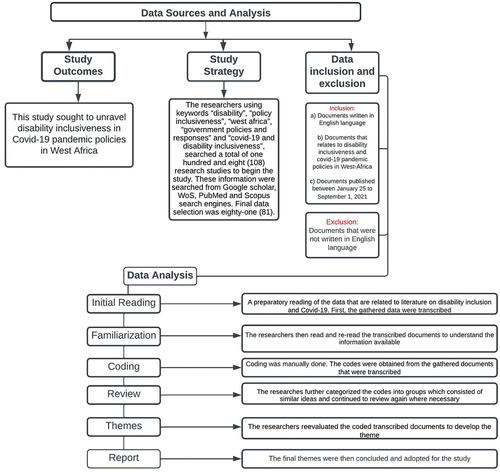

An unfortunate pandemic hit the World in December 2019, identified as the novel coronavirus (Covid-19). The Covid-19 pandemic is a highly infectious respiratory disease that spreads quickly (Aboagye et al., Citation2021; Dong et al., Citation2020). Shortly after the breakout of Covid-19, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a pandemic due to its quick spread (Xie & Chen, Citation2020). As of September Citation2021, World Meter Info announced that 11,921,074 persons had been infected with the virus in Africa (see, Figure ). Although some vaccines had been produced to control the virus (Busquet et al., Citation2020), researchers explain that they do not have 100% potency.

Figure 1. Reported Covid-19 cases amongst the countries under discussion.Source: World meters info (Citation2021)Data was retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?zarsrc=130 on 5th May, 2022

The international community and various governments across the globe outlined various strategies and protocols like social distancing and lockdowns to control the fast-spreading virus and the adverse impacts it causes (Aboagye et al., Citation2021; Gupta et al., Citation2020). As Covid-19 threatens humanity, many social activists have asked how the disabled can follow these protocols to protect themselves from the deadly pandemic. Even before the “new normal” Covid-19 pandemic,

Persons with Disabilities (PwDs) have been marginalized in society. Such persons do not get better access to health care, employment, education and little or no participation in society’s decision-making, especially in Africa (Craig et al., Citation2020; Schormans et al., Citation2021). In Africa, PwDs mostly live in poverty, abuse, and suffer violence (Muderedzi et al., Citation2017). The situation has intensified in this era of Covid-19, where PwDs are stigmatized directly or indirectly (Banks et al., Citation2020).

Additionally, PwDs face inequality in accessing health care, especially in the deprived areas of developing countries. The Covid-19 pandemic has further widened this inequity. Thus, the Covid-19 pandemic increases the inequalities faced by PwDs and PwDs exclusion has been exposed (Allam, Cai, Ganesh, Venkatesan, Doodhwala, Song, Hu, Kumar, Heit, Coskun, Coskun et al., Citation2020). The term “disability” has been a topic of debate for a long time. Researchers have not been able to ascribe a particular definition, especially in the social context. However, “disability” basically expounds on dysfunction’s physical and mental characteristics (Appleman, Citation2018; Jaffee, Citation2016). There are individual or social limitations that are associated with the dysfunction. PwDs are heterogeneous; thus, disabilities include Attention Deficit Disorder, Blindness, Brain Injuries, Hard of Hearing, Learning Disabilities, Medical Disabilities, Physical Disabilities, and Speech and Language Disabilities (Crow, Citation2008; Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Sinclair & Xiang, Citation2008).

Disability is a dynamic communication between health conditions and environmental and personal factors (Awuviry et al., Citation2019)(Zuurmond et al., Citation2019). Approximately, there are about 1 billion PwDs across the globe (Banks et al., Citation2020). The World Bank (Citation2020) data reveal that about 1/5th of the world’s population lives with a disability, and the prevalence rate is associated with developing countries. Although many countries have enacted laws to improve the living conditions of PwDs, many PwDs are denied the right to choose to live independently in the community (Sabatello et al., Citation2020).

The United Nations (United Nations, Citation2020) reveals that PwDs are heavily affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, especially in Africa. In addition, they are less likely to receive health care, employment, education, or to experience violence. The cases of PwDs, especially among people who have grown weak, have aggravated due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Naami & Mfoafo-M’Carthy, Citation2020). For instance, such people find it challenging to adjust to hygienic measures, access quality health or even receive general health information. In the situation where people are mentally challenged, Covid-19 has also worsened the situation across global health. Mental health conditions have increased significantly during lockdown periods because medical staff who could manage the situation need to be cautious and ensure good self-isolation (Fofana et al., Citation2020).

All plans and strategies during and after the deadly Covid-19 pandemic should robustly emphasize bridging the gap of inequalities and exclusion in society, especially for PwDs. The decisions of various countries and their efforts toward achieving social and economic recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic will be critical for developing and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. This will address disparities and ensure that no one is left behind, especially PwDs. The United Nations (Citation2020) quickly pronounced in their “Disability-Inclusive Response to Covid-19” to ensure that no PwD is left out of the developmental agenda. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, Article 11) highlights that countries that have ratified this convention should develop “all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of PwDs in situations of risk” (Kelly, Citation2021). Several reports indicate that PwDs face problems accessing treatment for Covid-19. Many of the public health measures implemented to contain the virus do not consider the needs of disabled people (Sabatello et al., Citation2020; United Nations, Citation2020).

Several researches have explored the inequalities and exclusions PwDs face in Africa (Kwegyir Tsiboe, Citation2020; Naami & Mfoafo-M’Carthy, Citation2020). Yet, the issue persists due to non-compliance with the policies and plans outlined by governments and other stakeholders. With the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, PwDs are challenged. They are excluded from society and government policies to a more significant extent. There have been limited reports and records on the care and support given to PwDs in Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, and Cape Verde even before the Covid-19. In the same vein, there is insufficient literature on the inclusion of PwDs, mainly due to limited research, lack of awareness and total neglect by the relatives of such PwDs (Sakellariou et al., Citation2020). More theoretical and empirical research is needed to determine the state and situation of PwDs in Africa amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. Four countries in West Africa namely, Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal and Cape Verde, were purposively selected to inform the discussion in this study (see, Table ). It could be realized and estimated that Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal and Cape Verde are the countries that have recorded the highest number of coronavirus cases as of May 2022 in West Africa (World meters info, Citation2021) and are known to have records for PwDs. It is of pressing demand that this research examines the influence of the Covid-19 pandemic on the inclusion of PwDs and the implications for attaining SDGs by 2030. This paper contributes to the literature by exploring the policies of various governments in some selected West African countries towards PwDs in the Covid-19 era and their implications for achieving SDGs by 2030. To the best of the authors knowledge, no study has examined the disability inclusiveness in Covid-19 pandemic policies in West African countries.

Table 1. Demographic, socioeconomic, health-related, and COVID-19-related characteristics of Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal and Cape Verde

2. Methods

The researchers adopted a qualitative study using thematic analysis and the interpretive document approach to explore remove government responses to Covid-19 concerning PwDs. This approach adopted by the researchers reflects a pattern of logic that demonstrate fairness in exploring the data gathered to understand this study. This analysis method confirmed the reliability and validity of the data examined (Tuffour, Citation2017). Thus, the researchers had the opportunity to read and review the documents multiple times and remained unchanged by the researchers’ influence (Bowen, Citation2009, p. 31). The researchers used published documents from governmental agencies, local government authorities and stakeholders in charge of Covid-19 issues and responses. The documents were gathered between January 25 to 1 September 2021, by two (2) authors KOE and ME. Authors EMA and NOO further analyzed the gathered data, and FM did thorough proofreading.

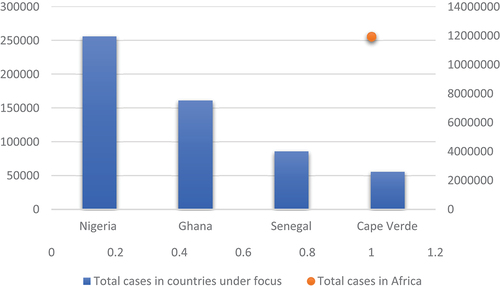

2.1. Data sources and analysis

Data and information identified and retrieved from the documents were primary data sources for this study. The researchers using keywords “disability,” “policy inclusiveness,” “West Africa,” “government policies and responses,” and “covid-19 and disability inclusiveness,” searched a total of one hundred and eight (108) research studies to begin the study. This information was searched from Google scholar, Web of Science (WoS), PubMed and Scopus search engines. From the 108 research documents, eighty-one (81) documents were selected. Documents were excluded from the screening process based on language. Thus, the researchers excluded all documents not written in the English Language. Hence the selection of the eighty-one (81) papers was finally included in this screening. The identified and retrieved documents included the measures reported to affect PwDs directly or indirectly. Thus, some measures are geared towards PwDs and measures that are not geared towards PwDs but impact their lives. The identified and examined documents included reports on disability and Covid-19, legislations, declarations and other documents that expound on the measures taken to respond to Covid-19 and PwDs and the deadly Covid-19 pandemic. The researchers carefully searched the official web pages of the health and employment ministries and the Covid-19 pandemic government web pages of each country under discussion. The researchers further resorted to official reports and other communique issued by the organizations responsible for PwDs. These organizations included the United Nations (UN), World Health Organization (WHO) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Based on the paper’s aims, the information identified and retrieved were summarized, and the main ideas were grouped into themes. The specifics of the literature screening procedures are shown in Figure .

As part of the data collection, data were also analyzed. This allowed for the assessment of saturation of data. Data were analyzed inductively using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Citation2006). First, the gathered data were transcribed. The researchers then read and re-read the transcribed documents to understand the information available. The transcripts were manually coded because there was no available software to assist the researchers. The codes were obtained from the gathered documents that were transcribed. The researchers further categorized the codes into groups of similar ideas for further review where necessary. The researchers reevaluated the generated codes and compared them with the transcripts concurrently. Questions were asked to validate, confirm and create comprehensible meanings related to the data. This helped create the themes (see, Table and Figure ).

3. Results and discussion

The identified results suggest that all governments in the four countries under study have policies that include the needs of PwDs. Table shows government responses on PwDs and the Covid-19 pandemic for each studied country. During this period of Covid-19, various governments enacted several policies to address the concerns of PwDs. PwDs especially are among the vulnerable group in society that has been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic (Courtenay & Cooper, Citation2021; Vieira et al., Citation2020). This current study expounds on how governments of various countries respond to the needs of PwDs. Whether these responses currently address the needs of PwDs and the implications of attaining SDGs targeted toward the needs of PwDs. Unfortunately, not all these policies and strategies directly address the needs of PwDs as a counter-response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Countries in West Africa are considered developing countries, suggesting a high level of inequalities in all spheres of life (Dominic et al., Citation2017). One area of global debate has been social inequalities, especially in the health sectors, which has left most West African countries exposed to the deadly Covid-19 pandemic (Chirisa et al., Citation2020; Martinez-juarez et al., Citation2020; See, Table ).

Table 2. Thematic areas

Table 3. Government responses to disability inclusivity during Covid-19 pandemic

There are numerous measures that all the four countries leveled regarding education. For instance, due to the various press conferences and sensitization on the deadly Covid-19 virus, various governments recommended that learning platforms be established and televised with sign languages and interpretation (see, Table ). These were not only limited to conferences but applied to online education since there was a lockdown in all these four countries. Thus, people with hearing disabilities could easily follow all this vital information being shared through sign languages that accompany the televised conferences and programs. There have been some contradictions between the government’s policies and recommendations and the implementations of the policies and recommendations (Sakellariou et al., Citation2020). For example, in all these four countries, the recommendations made by the government on education (see, Table ) to improve the lives of PwDs did not reflect in practice. Most PwDs did not have access to continuous online or televised education during this pandemic era (Braun & Naami, Citation2019; Dosu & Hanrahan, Citation2021).

The various governments of the countries under discussion had made declarations to protect the rights of the vulnerable in society during this pandemic, including PwDs. For instance, PwDs were given free PPEs (see, Table ) to ensure they were protected well enough from the Covid-19 virus infection. In Senegal, the government formed a community network to identify disabled people, monitor their well-being, and offer support (Loewenson et al., Citation2021). Also, in Ghana, the government recommended the introduction of telemedicine for people with Covid-19-related symptoms (Blayney et al., Citation2021). Due to the continuous health reforms in West Africa, which necessarily reflect on people’s everyday lives, there has been a disproportionate effect on PwDs. This issue has been severe during the deadly Covid-19 pandemic, and PwDs have suffered the consequences. Governments in the countries under discussion believe that their policies and recommendations have improved the quality of life of PwDs. However, PwDs believe that these policies and recommendations are not sufficiently recognized and have not informed the policies in this pandemic era. For example, PwDs are challenged by poverty, quality education, lack of access to quality healthcare, and participation in decision-making. These PwDs are affected such that they cannot dissociate themselves from such challenging situations but compromise since they are far from reaching the plans and recommendations of the government.

PwDs can not access an official government agency to access their benefits entirely. For instance, PwDs in Ghana need to register with the Ghana Federation of Disability Organizations (GFD). Those in Nigeria need to register with the Joint National Association of Persons with Disabilities (JONAPWD). PwDs in Cape Verde need to register with the Ministry of Youth, Employment, and Human Resources (MERHJ). Unfortunately, most PwDs have not been registered to confirm the actual status of PwDs under these specialized agencies, hence have not been able to access these benefits during this Covid-19 pandemic (Kwegyir Tsiboe, Citation2020; Sabatello et al., Citation2020). Sakellariou et al. (Citation2020) suggest that these are attributed to incomplete registration, making many PwDs not fully registered.

Also, the awareness of these agencies is limited as many PwDs are not known. PwDs who are aware of what is due them have been unable to register because they think the process is complex, especially the documents that need to be registered. These issues have increased the level of exclusion of PwDs from the various recommendations the governments have made to improve the lives of PwDs. This further suggests that the policies and recommendations that have been highlighted to benefit PwDs call for a collective responsibility from the government and other stakeholders. Clearly, this emphasizes the vulnerability of the disabled to poverty; their rights to education and quality healthcare.

Caregivers are categorized as frontline health workers and susceptible to contracting the Covid-19 virus (Banks et al., Citation2020; Krubiner et al., Citation2021). Even to a more considerable extent, governments did not have any special legislation to protect such frontline workers but only made suggestions and recommendations. During this pandemic, the countries’ government has not explicitly provided specific accommodation to support PwDs. However, to a more considerable extent, the government of these countries have instead permitted caregivers of PwDs to go to work, even in areas under lockdown, to better care for disabled people, especially the mentally challenged (see, Table ). More so, caregivers for PwDs have been given special incentives and increased wages and salaries as a form of motivation to give better attention to PwDs. Government officials believe that even if there is adequate accommodation to cater to all PwDs, motivating caregivers will contribute a lot to bettering the lives of PwDs.

With the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic intersecting with the issues of PwDs, it’s evident that in West Africa, such people are vulnerable, and the policies and strategies put into addressing their issues are not of priority. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has put policies in place to strengthen the co-existence of the West African States and policies. ECOWAS proposed establishing the ECOWAS Regional Action on Disability at the emergence of Covid-19 to ensure that PwDs are not left out in the developmental agenda. However, there have been minimal impacts of this intervention from the ECOWAS due to bureaucracy; resulting in a poor policy response to the issues of PwDs, especially in these challenging moments of emergencies (Okoro et al., Citation2020; Prado & Hoffman, Citation2019).

Although the ECOWAS Regional Action on Disability has been documented and implemented, ECOWAS has spearheaded the distribution of Covid-19 vaccines across countries in West Africa. ECOWAS has called for an all-inclusive educational program online to include sign languages to support PwDs with hearing impairment (Kyereko & Faas,Citation2021). These two initiatives that the ECOWAS has spearheaded align with access to education and health in the areas these four (4) countries under discussion sought to address. To a larger extent, the ECOWAS would be able to properly support its member states to comprehensively address the needs of PwDs when the ECOWAS Regional Action on Disability is adopted officially. The government’s response must take the form of legislation, policies, and recommendations for developing countries and address the needs of PwDs more comprehensively. Also, the countries under discussion have made recommendations, but these recommendations have not been translated into policies (Swanwick et al., Citation2020). The countries under discussion during the Covid-19 city lockdown especially did not pass any special legislation to protect the rights of PwDs. However, these countries have ratified the CRPD. This is evident in the various responses that have been outlined in Table . Despite all these pragmatic steps taken by these countries to address the situation of PwDs, the problem still exists in the face of this global emergency. Their needs are not met as expected by the appropriate state agencies responsible for addressing the needs of PwDs in West Africa.

In Nigeria and Ghana, Government agencies and stakeholders have adequately published information suggesting PwDs are included when decisions are being made to address their situation. Nigeria has ratified the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018, though implementation is yet to materialize. This Act will require that decisions cannot be reached for PwDs when they do not have a representative to participate in the decision-making process (Adewale et al., Citation2021). Also, in Ghana, the Ghana Somubi Dwumadie (Ghana Participation Program) is a four-year disability inclusion program that focuses on mental health, has been adopted. This program gives ears to the actual situation of PwDs and the best solutions to address these problems (see, Table ; Naami & Mfoafo-M’Carthy, Citation2020). However, in Senegal and Cape Verde, there has not been specific information published on how PwDs are involved in decision-making (see, Table ). Although specific information has not been published in these countries, governments in these countries have tackled other aspects of social life that better the lives of PwDs. This suggests that governments still have issues with PwDs at the center of decision-making.

3.1. Implication for SDGs

Countries in West Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal and Cape Verde, have made commitments to achieve their SDG targets to improve the lives of PwDs by 2030. These SDGs targeted at PwDs include 1- No poverty, 3- Good health and well-being, 4-Quality education, 8- decent work and economic growth and 10-Reduced inequalities. The United Nations approved the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 to replace the Millennium Development Goals. These SDGs have been operational in the last six (6) years and already look unpromising that many countries can achieve the set targets by 2030. The recent Covid-19 pandemic will affect these countries in achieving their targets by 2030 (Filho et al., Citation2020).

Table outlines government responses on specific SDG targets that various governments want to achieve by 2030 concerning PwDs. Thus, the table shows various governments’ responses to achieving specific SGD targets geared towards improving the lives of PwDs. During this Covid-19 pandemic, there were signs that PwDs have been affected adversely. The situation looks more worrying such that the situation may intensify if the government’s responses to include vulnerable people in the society are not given the needed attention. These impacts posed to the vulnerable in society, especially PwDs, put a severe threat to the development of many countries. This further hinders the attainment of the SDGs by 2030. Society must understand that life during and after the Covid-19 pandemic must be focused on building a non-discriminatory, all-inclusive economy that will benefit all. The efforts by various governments to include the issue of PwDs in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic is a pragmatic approach to ensure that countries progress towards achieving their SDGs by 2030, especially the targets that relate to PwDs (see, Table ).

Table 4. Government response on SDGs targets towards PwDs in Covid-19 pandemic

It is quite evident that with the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the SDG targets geared toward improving the lives of PwDs cannot be achieved within the 15 years (2015–2030). Although various governments have outlined major projects and recommendations, projects do not necessarily reflect PwDs (Sakellariou et al., Citation2020). There have been threats to SDG targets 1- No poverty, 3-Good health and well-being, 4-Quality education, 8-decent work and economic growth, and 10-Reduced inequalities, which seek to address issues of PwDs in this pandemic era. Although there have been several projects outlined by various countries (see, Table ), PwDs feel that their concerns are not fully integrated and included in the decision-making process. In this Covid-19 pandemic, when PwDs access medical care, they must pay for some services. This nullifies the efforts to achieve the targets geared toward improving the lives of PwDs under SDGs 1 and 3 since several disabled people do not have access to paid work (Bush & Tassé, Citation2017) and cannot afford pay for such health services.

Undeniably, the living conditions of these PwDs will be worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic, a situation seen as a critical setback to the SDGs (Finatto et al., Citation2021). The government of Senegal established the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (DSRP II) (see, Table ), highlighting the national program for disaster prevention, major risk reduction, and management to promote coordinated implementation. During this Covid-19 pandemic era, PwDs in Senegal unraveled that their needs have not been adequately met, although there are strategies to ease their poverty level (Loewenson et al., Citation2021). These impending challenges will further impact SDGs’ realization, especially SDG 3 targets highlighting PwDs. There should be more funds in such areas; otherwise, we will be far from realizing these goals. The current circumstances and agitations of PwDs urge us to reassess the flexibility of the SDGs in the face of such a global pandemic.

SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), and SDG 10 (reduced inequality) targets geared toward improving the lives of PwDs are threatened by Covid-19 because of the diversion of priorities. Diversion of priorities relates to the inconsistencies in the systems that have been put in place by various governments. Resolving these inconsistencies may, directly and indirectly, threaten the global funds needed to implement and realize other SDGs to address the needs of PwDs. Subsequently, global cohesion and shared obligation will be influential in ensuring governments improve from fatalities and regain energy toward achieving the SDGs in the post-pandemic era.

As we all fight against this global menace, there is no complete solution in the form of a curable vaccine, economic activities, and the realization of SDGs. PwDs and other vulnerable people in society will continue to suffer despite the numerous recommendations projected to better such people’s lives. Therefore, the countries under discussion should bear the lessons learned from this unparalleled catastrophe and use these lessons as directions to build a more buoyant society capable of enduring future global challenges that may hamper the realization of the SDGs.

various governments need to imitate and replicate these efforts in their pledge to attain existing SDG targets that seek to better the lives of PwDs but have been threatened by the deadly pandemic (see, Table ). With the remaining eight (8) and the threats posed by the Covid-19 pandemic on the projected fifteen (15) years life span of the SDGs, their further implementation must not be delayed, despite recent dynamics worldwide that affect PwDs. Governments of the countries under discussion should restructure their development policies geared towards bettering the lives of PwDs. As we continue to stress the need to implement strategies to achieve the SDGs to better the lives of PwDs, it is also imperative to recognize the influence of shared obligation. This includes extending obligations from governments to the global community, the private sector, philanthropical organizations, and civil society (Hörisch, Citation2021; Knox, Citation2015).

4. Conclusion

The study looked at the general national or centralized government and administrative responses to the Covid-19 pandemic concerning the inclusiveness of PwDs. The discussions were based on legislation, policies, and recommendations while ascertaining the implications of these exclusions on SDGs that seeks to address issues of PwDs. The deadly Covid-19 pandemic brought to light the social inequalities that existed, leaving PwDs victimized and disregarded in society. Several policies and recommendations project that their lives have been improved. As the Covid-19 pandemic looks like ending, it is imperative for government agencies, and other social organizations committed to addressing the needs of PwDs to review their policies, especially in this challenging global time. For various governments to have a win-win affair, thus improving the lives of PwDs and achieving their SDG targets geared toward PwDs, there should be a quick assessment of their commitment to Article 4(3) of the CRPD. Governments should approach the situation with both direct and indirect approaches to better address the needs of PwDs, especially in the pandemic and post-pandemic eras.

Nevertheless, the study was limited in the following ways amidst all the contributions. The interpretive document analysis adopted in this study limited the overall scope of this paper. This was because not all the documents identified and thoroughly examined provided all the necessary information to achieve the study’s aim. Some of the documents provided valuable data, while others provided minimal information. The researchers relied on accessible study information on the Covid-19, disability inclusion in decision making and SDGs to determine the study’s intended objective. Due to the heterogeneous nature of PwDs, other researchers can also investigate specifically how African governments could target the different categories of PwDs more efficiently. These are beyond this paper’s scope, but future research on these issues is necessary to understand the full implications and draw valuable policy lessons from this Covid-19 pandemic, including the inclusivity of PwDs and SGDs.

Abbreviations

CRPD - Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

ECOWAS - Economic Community of West African States

GFD - Ghana Federation of Disability Organizations

JONAPWD - Joint National Association of Persons with Disabilities

MERHJ - Ministry of Youth, Employment, and Human Resources

MoH - Ministry of Health

NHIS - National Health Insurance Scheme

PwD – People with Disabilities

UN - United Nations UN

WHO - World Health Organization

Authors contributions

The documents were gathered between January 25 to 1 September 2021, by two (2) authors Kwaku Obeng Effah (KOE) and Michael Erzuah (ME). Authors Emmanuel Mensah Aboagye (EMA) and Nana Osei Owusu (NOO) further analyzed the gathered data, and Felix Mensah (FM) did thorough proofreading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kwaku Obeng Effah

Emmanuel Mensah Aboagye is currently a master’s student at Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, China. Through publications, he is able to satisfy his genuine passion for research. His research interests transcend varied boundaries in academia to encapsulate anything he finds interesting, Environmental law, International law, Gender studies, disability issues etc. Emmanuel is currently reading International Law (Ph.D) at Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, China.

References

- Aboagye, E. M., Attobrah, J., Effah, N. A. A., Afrane, S., & Mensah, F. (2021). “Fortune amidst misfortune”: The impact of Covid-19 city lockdowns on air quality. Sustainable Environment, 7(1), 1885185. https://doi.org/10.1080/27658511.2021.1885185

- Adewale, H. G., Oluyomi, E. F., & Adebisi, R. O. (2021). Disability act of 2019: A riposte for inclusion of persons with special needs in Nigeria. Journal of Educational Research in Developing Areas, 2(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.47434/JEREDA.2.1.2021.76

- Allam, M., Cai, S., Ganesh, S., Venkatesan, M., Doodhwala, S., song, Z., Hu, T., Kumar, A., Heit, J., Coskun, A. F., & Coskun, A. F. (2020). COVID-19 diagnostics, tools, and prevention. Diagnostics, 10(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10060409

- Appleman, L. I. (2018). Deviancy, dependency, and disability: The forgotten history of eugenics and mass incarceration. Duke Law Journal, 68(3), 418–478. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol68/iss3/1

- Awuviry-Newton, K., Wales, K., Tavener, M., & Byles, J. (2020). Do factors across the World Health Organisation's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework relate to caregiver availability for community-dwelling older adults in Ghana?. PloS One, 15(5), e0233541.

- Banks, L. M., Davey, C., Shakespeare, T., & Kuper, H. (2020). Disability-inclusive responses to COVID-19: Lessons learnt from research on social protection in low- and middle-income countries. World Development Journal, 137(1), 105178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105178

- Blayney, D. W., Bariani, G., Das, D., Dawood, S., Gnant, M., De Guzman, R., & Hendricks, C. (2021). Spotlight on International Quality: COVID-19 and Its Impact on Quality Improvement in Cancer Care. JCO Global Oncology, 7, 1513–1521.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, A. M. B., & Naami, A. (2019). Access to higher education in Ghana : Examining experiences through the lens of students with mobility disabilities access to higher education in Ghana : Examining experiences through the lens of students with mobility disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 68(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1651833

- Bush, K. L., & Tassé, M. J. (2017). Employment and choice-making for adults with intellectual disability, autism, and down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 65(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.04.004

- Busquet, F., Hartung, T., Pallocca, G., Rovida, C., & Leist, M. (2020). Harnessing the power of novel animal-free test methods for the development of COVID-19 drugs and vaccines. Archives of Toxicology, 94(6), 2263–2272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-020-02787-2

- Chirisa, I., Mutambisi, T., Chivenge, M., Mabaso, E., Matamanda, A. R., & Ncube, R. (2020). The urban penalty of COVID-19 lockdowns across the globe : Manifestations and lessons for Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa. GeoJournal, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10281-6

- Courtenay, K., & Cooper, V. (2021). Covid 19 : People with learning disabilities are highly vulnerable They must be prioritised, and protected. BMJ, 3721, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1592

- Craig, K. D., Holmes, C., Hudspith, M., Moor, G., Moosa-Mitha, M., Varcoe, C., & Wallace, B. (2020). Pain in persons who are marginalized by social conditions. Pain, 161(2), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001719

- Crow, K. L. (2008). Four types of disabilities: Their impact on online learning. TechTrends, 52(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-008-0112-6

- Dominic, A., Amodu, L., Azuh, A. E., Toluwalope, O., & Oluwatoyin, M. A. (2017). Factors of gender inequality and development among selected low human development countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, 22(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2202040107

- Dong, X., Cao, Y. Y., Lu, X. X., Zhang, J. J., Du, H., Yan, Y. Q., Akdis, C. A., & Gao, Y. D. (2020). Eleven faces of coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 75(7), 1699–1709. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14289

- Dosu, B., & Hanrahan, M. (2021). Barriers to drinking water security in Rural Ghana : The vulnerability of people with disabilities. Water Alternatives, 14(2), 453–468.

- Filho, W. L., Brandli, L. L., Salvia, A. L., Rayman-bacchus, L., & Platje, J. (2020). COVID-19 and the UN sustainable development goals : Threat to solidarity or an opportunity ? Sustainability, 12(1), 5343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135343

- Finatto, C. (2021). Sustainability in Covid-19 Times: A Human Development Perspective. In S. S. Muthu (Ed.), COVID-19. Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3860-2_1

- Fofana, N. K., Latif, F., Sarfraz, S., Bilal, Bashir, M. F., Komal, B., & Komal, B. (2020). Fear and agony of the pandemic leading to stress and mental illness: An emerging crisis in the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Psychiatry Research, 291(1), 1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113230

- Gupta, A., Bherwani, H., Gautam, S., Anjum, S., Musugu, K., Kumar, N., Anshul, A., & Kumar, R. (2020). Air pollution aggravating COVID-19 lethality? Exploration in Asian cities using statistical models. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15(1) , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00878-9

- Hörisch, J. (2021). The relation of COVID-19 to the UN sustainable development goals: Implications for sustainability accounting, management and policy research. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 12(5) , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-08-2020-0277

- Jaffee, L. J. (2016). The materiality of virtual war: Post-traumatic stress disorder and the disabling effects of imperialism. Policy Futures in Education, 14(4), 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316637971

- Kelly, B. D. (2021). Mental Capacity, Human Rights, and the UN's Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 49(2), 152–156.

- Knox, J. H. (2015). Human rights, environmental protection, and the sustainable development goals. Washington International Law Journal, 24(3), 517–536. https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol24/iss3/6

- Krubiner, C., O'Donnell, M., Kaufman, J., & Bourgault, S. (2021). Addressing the Covid-19 Crisis's Indirect Health Impacts for Women and Girls. Center for Global Development.

- Kwegyir Tsiboe, A. (2020). Describing the experiences of older persons with visual impairments during COVID-19 in rural Ghana. Journal of Adult Protection, 22(6), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-07-2020-0026

- Kyereko, D. O., & Faas, D. (2021). Integrating marginalised students in Ghanaian schools: insights from teachers and principals. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 23(1),1–18. DOI: 10.1080/03057925.2021.1929073

- Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E., Albarico, M., Mortaji, N., & Karon, L. (2018). A systematic review of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 28(4), 634–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9756-z

- Loewenson, R., Colvin, C. J., Szabzon, F., Das, S., Coelho, V. S. P., Gansane, Z., Yao, S., Wilson, D., Rome, N., Nolan, E., Loewenson, R., Colvin, C. J., Szabzon, F., Das, S., Coelho, V. S. P., Gansane, Z., Yao, S., & Asibu, W. D. (2021). Beyond command and control : A rapid review of meaningful community-engaged responses to COVID-19. Global Public Health, 16(8), 1439–1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1900316

- Martinez-juarez, L. A., Cristina, A., Orcutt, M., & Bhopal, R. (2020). Governments and international institutions should urgently attend to the unjust disparities that COVID-19 is exposing and causing. EClinicalMedicine, 23(1), 100376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100376

- Muderedzi, J. T., Eide, A. H., Braathen, S. H., & Stray-Pedersen, B. (2017). Exploring structural violence in the context of disability and poverty in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Disability, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v6i0.274

- Naami, A., & Mfoafo-M’Carthy, M. (2020). COVID-19: Vulnerabilities of persons with disabilities in Ghana. African Journal of Social Work, 10(3), 9–17.

- Okoro, A. S., Ujunwa, A., Umar, F., & Ukemenam, A. (2020). Does regional trade promote economic growth? Evidence from Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Journal of Economics and Development, 22(1), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/JED-10-2019-0039

- Prado, M. M., & Hoffman, S. J. (2019). The promises and perils of international institutional bypasses: Defining a new concept and its policy implications for global governance. Transnational Legal Theory, 10(3–4), 275–294.

- Sabatello, M., Landes, S. D., & McDonald, K. E. (2020). People with disabilities in COVID-19: Fixing our priorities. American Journal of Bioethics, 20(7), 187–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1779396

- Sakellariou, D., Malfitano, A. P. S., & Rotarou, E. S. (2020). Disability inclusiveness of government responses to COVID-19 in South America: A framework analysis study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01244-x

- Schormans, A. F., Hutton, S., Blake, M., Earle, K., & Head, K. J. (2021). Social isolation continued: Covid-19 shines a light on what self-advocates know too well. Qualitative Social Work, 20(1–2), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020981755

- Sinclair, S. A., & Xiang, H. (2008). Injuries among US children with different types of disabilities. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1510–1516. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.097097

- Swanwick, R., Oppong, A. M., Offei, Y. N., Fobi, D., Appau, O., Fobi, J., & Frempomaa Mantey, F. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on deaf adults, children and their families in Ghana. Journal of the British Academy, 8(1), 141–165.

- Tuffour, I. (2017). A critical overview of interpretative phenomenological analysis: A contemporary qualitative research approach.

- United Nations. (2020). Policy brief: A disability-inclusive response to COVID-19. United Nation, 1–18. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_on_persons_with_disabilities_final.pdf

- Vieira, C. M., Franco, O. H., Restrepo, C. G., & Abel, T. (2020). Maturitas COVID-19 : The forgotten priorities of the pandemic. Maturitas, 136(1), 38–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.04.004

- World Bank. (2020). Global economic prospects, June 2020. The World Bank.

- World meters info (2021) Data was retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?zarsrc=130 on 5th May, 2022.

- Xie, M., & Chen, Q. (2020). Insight into 2019 novel coronavirus — An updated interim review and lessons from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 94 (1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.071

- Zuurmond, M., Mactaggart, I., Kannuri, N., Murthy, G., Oye, J. E., & Polack, S. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to accessing health services: A qualitative study amongst people with disabilities in Cameroon and India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1126.