Abstract

This article discusses Jewish women who emigrated from Islamic countries to the State of Israel during the 1950s. When they arrived in the country, they encountered a secular establishment that had originated in Europe (Ashkenazic) and possessed an entirely different culture than that of these women, who were religious and had come from Africa and Asia (Mizrahim). Alongside the secular establishment, they also encountered a small ultra-Orthodox community, which had its origins in Europe. The religious customs of this group differed greatly from those of the émigrés from Africa and Asia. In this society, the role of the woman is to financially support her sons and husbands, who immerse themselves in the study of Torah for numerous years after marriage. The article focuses on the manner in which the role of these Mizrahi women was configured and strengthened after their demise, by political leaders and rabbis, in accordance with the paradigm of contemporary Ashkenazic ultra-Orthodox society. The primary research tools are obituaries of first-generation immigrant women, authored by the male political elite in the weekly party newspaper, throughout the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The findings are that ultra-Orthodox Mizrahi party in Israel—the Shas party—is shaping a new religious society for Jewish immigrants from Africa and Asia. This society’s current ideal was never extant outside of Israel. It also differs from women’s traditional Diaspora role as homemakers. The uniqueness of these findings lies in their evidence regarding the manner in which the party creates this society by shaping a new image of deceased immigrant women.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The article discusses Jewish women who immigrated from Islamic countries to the State of Israel during the 1950s. It examines how an ultra-Orthodox party creates an ultra-Orthodox society by shaping a special feminine model, which empowered the poor immigrant women, most of whom lacked education. The party transformed these women into nurturers of the male Torah world, without earning a living. A model which had never existed in their countries of origin.

This invented model influenced the second generation of women. Many apply it even though they are more educated. The study is based on unique sources which have never been used in academic research – the obituaries of women in a party political newspaper.

1. Introduction

This article analyses how an Israeli political party (Shas) is shaping a new religious society—a society with its highest ideal being the desire that young boys and adolescents, married and unmarried men, all study Torah as their main occupation. This is a socio-political model, shaped in Israel by Jewish immigrants from Europe (Ashkenazim). Its aim is to nurture the ‘Torah world”, in which men studying Torah for many years is the overarching value (Brown, Citation2017; Friedman, Citation1987, Citation1991). All family and community resources are harnessed to this objective. The result is an impoverished society that forgoes a comfortable existence for the sake of Torah study. This situation never previously existed among the Jews in Africa and Asia, where women were homemakers while the men worked and provided for their families.

The importance of the article lies in the demonstration and analysis of the female aspect of shaping a new sociopolitical reality, and heretofore unutilised research tools: obituaries of first-generation immigrant women. The article discusses an ultra-Orthodox political party in Israel with unique characteristics: the Shas Party. The Shas party was established by rabbis who were second-generation immigrants from Africa and Asia (Mizrahim) in Israel (Feldman, Citation2013). The article analyses the means by which this party creates the Ashkenazic ideal of the “Torah world”, utilising the evocation of first-generation immigrant women, despite the fact that this behaviour is representative only of a minority. It also demonstrates how twenty-first century ultra-Orthodox women, the second generation to immigrants from Africa and Asia, help manufacture and maintain this society. Today, Mizrahi educated women, integrated within secular Israeli society, maintain the boundaries of their conservative, patriarchal society.

Studies in Israel (see for example: Lehmann & Siebzehner, Citation2006; Leon, Citation2009; Lupu, Citation2004) found various and varying factors which brought about the socioreligious change created by the Shas Party. However, the woman’s role in this important sociopolitical change has not yet been studied. The article would have us believe that changing the image of the woman is one of several means by which the Shas Party shapes an ultra-Orthodox Mizrahi society. The article has two goals. The first is to examine the overt message manifest in the obituaries, by means of the question:

What are the characteristics of the new political feminine model, as configured by the party?

The second goal is analysing the masked message. The article examines the manner in which this covert sociopolitical message has impacted upon the second-generation women, utilising the second question:

How do second-generation women operate within this construct today?

After discussing the research findings and an answer to these questions, this paper would suggest an as-yet unexplored and unique track—the political fashioning of a community, using obituaries about women. The principal assertion is that to achieve such a significant socioreligious change, the women must acquiesce to the process, since it is they who are required to shoulder the burden.

The research is based on obituaries of local first-generation immigrant women in a political weekly. Through the obituaries, the article analyses the means by which a political party formulates a model of women supporting men studying Torah, as well as the manner in which this sociopolitical model impacts upon the second-generation women.

Researchers studying women’s image in the media have not yet focused upon and debated obituaries as a practicable tool and source for the conveyance of political and ideological content. Nor has this been viewed as a tool for shaping a feminine model using a political newspaper. I hope, additionally, that this study will contribute to the meagre information available on this topic.

2. Mizrahi Jewish society in Israel

2.1. The religious community contends with a secular establishment

Israel’s founders emigrated from Eastern Europe; most were secular (Halamish, Citation2006). This was one of the purposes for their implementation of secular coercion and Western culture with their adoption of the “melting pot” policy (Zameret, Citation2002). However, this policy was unsuitable for the immigrants from Africa and Asia. Therefore, the government derided and attempted to obliterate their flexible religious tradition, along with their Arab culture and mentality. The government’s “melting pot” approach was to modify what they termed the “Diaspora characteristics” of all Jews in Israel, such that society would be homogeneous and all individuals would resemble one another.

Most of the Jews in the state during its first three years of existence (1948–1950) had immigrated from Europe (see, ). Aside from the fact that they ruled the country, they also worked in public bureaucracy, controlled many employment opportunities via the workers’ unions, and managed its pedagogical institutions.

Table 1. Immigrants according to continent of birth (1948–1951)Footnote3

The second generation of those immigrants restored their status in Israeli society with a political party—Shas—founded for this purpose in 1984. Its founders’ intent was to direct the immigrants from Africa and Asia toward a more religious lifestyle (Feldman, Citation2013), than the one they had practised in their countries of origin (Yadgar, Citation2010). During the 1980s the abandoned synagogues became filled with young people (Leon, Citation2006). Ethnic holidays and culture gained incredible popularity (Feldman, Citation2012, Citation2020c; Sharaby, Citation2009; Weingrod, Citation1990). And the religious educational system established by the party served as a platform for a return to religious life (Feldman, Citation2011). During the early twenty-first century, most Shas party supporters defined themselves as ultra-Orthodox (Ettinger & Leon, Citation2018; Leon, Citation2009). The party thus succeeds in promoting the “Torah world” according to the Ashkenazic model and remoulds its supporters into a socioreligious model that differs from the one they practiced in the Diaspora (Doron, Citation2012; Zohar, Citation2006). Nevertheless, the role of the women supporting the party during the process of religious intensification has still not achieved the position it deserves in research. Only the studies by Feldman (Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2017b, Citation2020a) scrutinised women’s role in this reality.

2.2. The human capital of Mizrahi immigrants

In Western society, it is normative to view education as human capital which enables people to enjoy a respectable social and economic status, particularly as combined with the concurrent potential to transition to another profession and provide an upgraded education for their children. As is visible in , the educational status of the women immigrants from Africa and Asia in Israel was exceedingly deficient.

Table 2. Educational level of immigrants arriving 1948–1954Footnote4

The educational level of the first generation of Mizrahi women is important, since this article will focus on the female Shas Party supporters (Feldman, Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2017b, Citation2020a) and their role in the changes. Table displays the education of the immigrants according to continent.

The table displays the fact that over half the women immigrants from Africa and Asia received no formal schooling, and 26.2% had not completed elementary education. A total of 84% of the women had limited access to education as children.

Those immigrant women, who were compelled to find employment outside the home due to their economic situation in Israel, were employed in occupations of menial labour or providing services, with commensurately low salaries and lacking the opportunity for professional advancement. Thus, they found themselves on the very lowest rungs of Israeli society. When we examine the figures for the Mizrahi men, it emerges that they, too, were incapable of extricating their families from poverty and their inferior social status.

Approximately one quarter of Mizrahi men had received no formal schooling, and almost half had not completed their elementary education. A total of 72% had a very poor education. It can be deduced that the lifestyle of the majority of Jews from Africa and Asia did not include formal schooling, which explicates their long-term difficulty in integrating in the new state (Ben-Porat, Citation1989, pp. 105–117; Cohen & Haberfeld, Citation2004; Hacohen, Citation1994; Lissak, Citation1986, Citation1999; Sikron, Citation1986). Immigrants with such poor human capital—aside from their lack of knowledge of Hebrew, the language of the country—found it difficult to support their families financially or to assist their children with their high school or academic education (Cohen, Citation1998).

2.3. The Shas party—A Mizrahi party for advancing Ashkenazic ultra-Orthodox values

Shas is an ultra-Orthodox party, founded in Israel prior to the 1984 parliamentary elections. Its followers and leaders immigrated to Israel from Muslim countries during the 1950s. Most of these preserved their traditional religious lifestyle (Feldman, Citation2006, Citation2013). But over the last twenty years, the majority of its adherents have chosen to become more religious and ultra-Orthodox (Cohen, Citation2006; Caplan, Citation2006; Lehmann & Siebzehner, Citation2006; Leon, Citation2006). However, all its spiritual and political leaders emanated from the ultra-Orthodox stream.

The main features of Israel’s Ashkenazic ultra-Orthodox society are being a society of men who study religion for many years, during which period of time they do not function as the main financial support for their families (Brown, Citation2017; Friedman, Citation1987, Citation1988, Citation1991, Citation1995). The Ashkenazic ultra-Orthodox stream created in Israel is relevant, since the second generation of Mizrahi immigrants aspires to adopt its values, despite the fact that such a style of male religious scholarship was never extant amongst the Jews of Asia or Africa. As such, the party’s initial project was to establish a network of government-funded ultra-Orthodox preschools and elementary schools spanning the entire country (Feldman, Citation2011, Citation2017a, Citation2020b). Later, the party also founded its organization for women (Feldman, Citation2005) to provide them with a professional education, religious culture, and social activities within an ultra-Orthodox framework. Correspondingly, the party championed the establishment of an ultra-Orthodox academic college for women (Kalagy, Citation2007), with the objective of encouraging their advancement within the Israeli labour market, to earn remunerative salaries and underwrite their husbands, who were engaged in Torah study (Feldman, Citation2020a).

It is important to note that whereas the Shas Party adopted the Ashkenazic model of a society of male learners, it did so without the corresponding strict constraints on women’s academic education and employment (Feldman, Citation2007, Citation2020a).

3. Methodology

3.1. Obituaries of women in the Yom LeYom newspaper

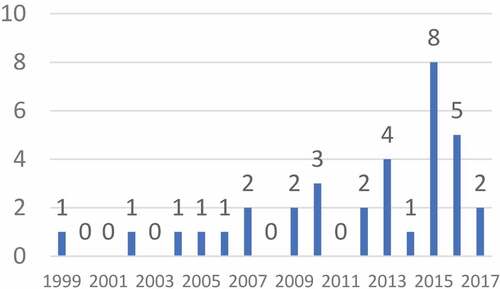

As a subscriber to Yom LeYom, the official Shas Party newspaper, I compiled most obituaries for women published in the newspaper over a period of approximately twenty years (1999–2017), a total of 34 articles. This acquisition concluded in 2017 with the newspaper’s sale to a commercial investor. shows the number of obituaries each year.

The obituaries noted in are not death notices, but rather articles delineating the pursuits, undertakings and lineage of these women. The question arising from these figures is, how was it possible that so few female party supporters passed away during this period? A closer perusal of the obituaries clarifies that the women thus honoured were only those women from rabbinical families or those who chose to be active in the party’s institutions. Put differently, only women who suited the party’s desired sociopolitical change.

3.2. Analysing the obituaries

The social constructionist approach is important for understanding the social process in which gender roles are defined and internalized. The primary assumption in this approach is that reality has symbolic significance, which imparts concepts with a varying significance in every personal and social interaction (Adoni and Mane Citation1984), as well as in various forms of media (Hall, Citation1997). This is a dynamic process which imparts actual significance into the symbolic reality of every community, and defines its new constructs for future generations (Adoni and Mane Citation1984; Boudreau, Citation1986).

To analyze the obituaries and the new “social constructionism”, the article also employed qualitative-ethnography analysis, in accordance with the hegemonic approach to researching the media. According to the hegemonic approach, derived from Neo-Marxism, texts drafted with hegemony are intended to change awareness.

This theory examines the manner in which hegemony utilises media to buttress the social order, while slowly adopting changes to be integrated with societal values (Gitlin, Citation1978, Citation1979; Gramsci, Citation1992). As the obituaries were printed in a political newspaper available by subscription, both the written and unwritten messages contained therein will be analysed as being political (Heck, Citation1981). To understand both overt and covert messages, the article will regard the obituaries as political communications.

Lemert (Citation1984, Citation1992) wrote about “mobilising information”. His intention was that the role of print media is to provide the public with information about the political system and to enable the public to understand the implications of life within their community. In accordance with the hegemonic approach, the women’s obituaries in the Shas political newspaper represent the party’s goals. They need not reflect the general modernisation processes of the second-generation women, but rather the political change the party desires to implement. As Hamilton (Citation2004, p. 7) wrote, “News is a commodity, not a mirror image of reality”. The premise of the current study corresponds with this, viewing the obituaries as a political commodity intended to reshape the second-generation immigrants.

In Israel, the political ultra-Orthodox media is run according to the hegemonic approach, guarded and implemented by a spiritual council, which supervises the content of the articles and commercial advertising (Caplan, Citation2001; Michelson & Zimmermann, Citation1990). The Shas weekly Yom LeYom was also carefully supervised by the party leadership. Its editor previously served as party spokesperson. The editor told me that most obituaries were written by male journalists, as directed by rabbis. Few were authored by family members.

To answer the overt research question—regarding the feminine model: The article analyses the obituaries according to two categories:

The Home Expanse: How the women run their home and educate their children.

The Personal Expanse: Isolated from their family; living in the periphery; the relationship with their spouse, and self-actualization.

To answer the covert question of whether and how the political feminine model influenced the second generation, I interviewed many women active in the party. I chose the stories of three particularly prominent women.

Before analysing the obituaries, we must familiarise ourselves with the ideal female paradigm of the first generation of immigrants from Islamic countries.

4. Findings

4.1. Shaping the paradigm of ideal first-generation women

This section seeks to illustrate the characteristics of the ideal woman, using the figure of the most important woman in the party’s history—Margalit Yosef, because she was the wife of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the party’s spiritual leader from the day of its establishment (1984), until his death in 2013. This was the rationale as to why there were many obituaries written about her over the years, some of which the article will refer to later.

The section is based on the biography written by her granddaughter (Katzir, Citation1999).

4.1.1. Margalit Yosef

Margalit Yosef was born in 1927 in Syria, into a family considered “comfortable” financially. Her mother was a homemaker, like most Jewish women of her time. Her father was apparently a rabbi and teacher. Margalit studied in a secular Jewish school, and learned Jewish customs informally at home. The fact that there was a non-religious school for Jewish girls in Damascus informs us about the moderate religious character of that community, as existed in the Jewish communities in the Arab countries.

She was orphaned from her mother at the age of eight, and her father decided to immigrate to Israel to provide his daughter with a Jewish environment (Katzir, Citation1999, p. 9). Margalit divided her youth between her home in Jerusalem and that of her older sister in Damascus. She occupied herself with housework while in Jerusalem, and while in Syria she assisted her sister in raising her children. Never again did she attend school. Her biography does not mention her age, but I have calculated that she was no older than ten. Her family did not perceive any problem with her not going to school. Margalit was quoted in the book as saying, “At least I knew how to read” (28). Her level of education corresponds to the poor standard of education of the Jewish women immigrants from Islamic countries after the establishment of the State of Israel.

People began to suggest matches for her when she was 17, but she refused them all. In the end, she chose a boy who was poor, but a great Torah genius—Ovadia Yosef. At the age of 17, Margalit knew she was willing to live a life of poverty with a “true Torah scholar” (Katzir, Citation1999, pp. 39–42). After their marriage, Margalit and Ovadia moved into their new home, consisting of one room, with an external bathroom and shower that was shared by all the residents of the building. The small room contained almost no possessions, other than Rabbi Ovadia’s holy books. The Yosef's had two children, and their financial situation was dire.

The conditions of Margalit Yosef’s life are similar to those of the women in the obituaries: few years of formal schooling, an aspiration to have a husband who studies Torah, and an agreement to live with him in poverty.

Rabbi Ovadia was offered the position of rabbi in Cairo, which would improve his economic situation. Margalit did not want to leave her father, brother, and friends in Jerusalem. However, she said to her husband, “For whither thou goest, I will go … until the end” (Katzir, Citation1999, p. 60). They spent three years in Egypt, and then returned to Jerusalem after the establishment of the state.

Economic hardship forced them to move to various cities, where Rabbi Ovadia found employment as a rabbi and rabbinic judge. Margalit’s biography describes how she relinquished her own desires for those of her husband, who was transformed from a poor student into the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel. This article will demonstrate later that leaving her city, family, and friends is another shared characteristic of Margalit Yosef and the women in the obituaries.

When Rabbi Ovadia was appointed Chief Rabbi of Israel, their home became open to all. Margalit set up the “Kindness Headquarters” in her Jerusalem home—assisting women who were experiencing financial privation (Katzir, Citation1999, pp. 135–138). Doing kind deeds is one of the Jewish commandments, with the reward being spiritual. I will demonstrate below that all the obituaries contain descriptions of the deeds of kindness performed by the women of the first generation of immigrants.

The book ends with the statement that accompanied Margalit from the time of her nuptials: “I live to serve the rabbi” (207).

Margalit is the only woman who had a biography written about her. The information about the other female Shas supporters is found only in their obituaries. Since all the obituaries are similar, the article elaborates on one example to illustrate the political trend.

4.1.2. Chana Malka

Chana Malka was born in 1941 in Morocco. The obituary does not supply biographical details of her childhood or adolescence, but rather begins just prior to her marriage in Israel. During a period when most immigrants sought to assimilate into Israeli society, Moshe Malka made a unique stipulation to the young Chana: “I am seeking a wife who will help me disseminate Torah; if you agree, we will get married.” Chana agreed to marry the poor man who promised her a life of material suffering, “and from their wedding until her final day, she dedicated herself to the teaching of Torah, and devotedly helped her husband maintain his glorious institutions.” The obituary notes, too, that she dealt with everything connected with the yeshiva that her husband founded. “She taught her children to love Torah and sacrifice themselves to disseminate Torah” (Yom LeYom 15 August 2013).

The models of Margalit Yosef and Chana Malka are those of the ideal female. Both devoted their lives to a poverty-stricken husband who desired to become a Torah scholar. Both were forced to leave their homes and friends due to economic privation, and to live in distant cities. As we will discern later, this political message features in all the obituaries, despite these being Israel’s early years, when the entire population suffered dire financial straits, and despite Zionist ideology during the 1950s marketing values of tilling the soil and establishing new settlements for the immigrants. In the early twenty-first century, the Shas Party newspaper describes a completely different reality, one of male Torah scholars. Yom LeYom possesses great importance as the creator of a reality, as it addresses its subscribers, most of whom had not yet been born during the 1950s. The Shas Party operated in accordance with the hegemonic approach, creating a new social recollection—one in which the role of women is to nurture men studying Torah. Therefore, the newspaper wrote about just a few women out of the tens of thousands of women who immigrated to Israel: those who suited the “social order” which the party desired to advance.

4.2. The home expanse: “Not a mirror image of reality”

Most Mizrahi female first-generation Shas supporters were of low status. The majority were housewives without a high school education; some were even illiterate. If they were employed outside the home, it was in jobs associated with the home, such as service industries, cleaning, or cooking, because these women were presumably expected to be active in the home (Walter & Wilson, Citation1996; Wood, Citation1998). However, this information does not materialise in the obituaries of the first-generation immigrant women. As Heck (Citation1981) writes, what is not written and why also carries significance. In the case of the Shas Party, this means it emphasised women’s activity only on behalf of boys and men studying Torah.

4.2.1. Margalit Yosef

Many obituaries about Margalit Yosef (1927–1994) were published over the years, and all describe only her sacrifice for her husband. What kind of housewife was she? What did she cook? We don’t know, although she never worked outside the home. Rabbi Yosef eulogises his wife, “everything belongs to her. A wise son comes from her.” According to his words, their success is not manifestly linked with his greatness and diligence in Torah study, whereas Margalit herself had had no more than three or four years of education (Katzir, Citation1999).

In line with the hegemonic theory, the eulogy Rabbi Yosef delivered about his wife enhances the social order, while slowly appropriating changes to be combined with societal values (Gitlin, Citation1978, Citation1979; Gramsci, Citation1992). As Hamilton (Citation2004, p. 7) writes, “News is a commodity, not a mirror image of reality”. A reader unfamiliar with the Torah genius of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef will be unaware of the covert message in his words: women’s role is to nurture sons who study Torah.

4.2.2. Other women

Next in the hierarchy is Margalit Ziv, founder of the party’s preschool network. No information is provided about typical household chores in the obituaries about her or other women. Rather than simply ignoring their lack of education, their devotion to the education of the children and men is emphasised. The obituaries state, for example, “She made certain to educate her sons and daughters to observe the Torah and its commandments.” “She devoted herself to educating and strengthening faith.” “She demanded that husbands toiling in their Torah study would be chosen for her daughters.” The message is unequivocal: a woman’s task is to raise children who will study Torah diligently for many years. This contrasts with the pre-Shas reality in Mizrahi society, both overseas and in Israel, where no tradition existed of men studying Torah without supporting their families. Before the party’s establishment, most Mizrahi children in Israel attended State religious or secular schools. The majority of second-generation immigrants began their employment in various forms of physical labour after elementary school, to support their families. Therefore, the emphasis on Torah-oriented education indicates the political aspiration to shape a different generation from that of the immigrant parents. As Heck (Citation1981) writes, one needs to pay attention regarding which messages Shas emphasises and which remain unspoken. The party has succeeded impressively, because over the past twenty years thousands of Mizrahi children have studied mainly religious studies in its political educational network (Feldman, Citation2011, Citation2017a, Citation2020b).

This article does not argue that the social change among the party supporters in the twenty-first century succeeded exclusively due to the women of the first generation of immigrants to Israel. Instead, we argue that there is inordinate leverage to their being harnessed for the men’s study ethos. With the obituaries, the party succeeded in shaping a historical image of a society of men studying Torah, in stark contrast to the dominant and silent majority who preserved the patriarchal social structure from other lands in Israel, in which men support their families economically and women serve as homemakers.

4.3. The personal expanse: “Strengthening the social order”

This section describes the women’s individual choices, examining their personal choice to live in the Torah world. Their agreement to abide in poverty with their husbands studying religious texts and barely supporting them. And their attitude towards moving to the periphery, far from their families. It will also examine primary values in the Jewish religious world: acts of kindness and modesty.

4.3.1. Margalit Yosef

Margalit Yosef was the First Woman of the Shas party, and therefore many obituaries were written about her. See for example:

She would live a life of poverty … [She] literally saved money from her own food, [because] it’s not easy to be the wife of the greatest Torah scholar of the generation; it demands extreme sacrifices for the wife’s needs … There’s no free time to go out together to family celebrations or visits, or even to doctors. She even went to give birth to her children with her neighbour, so her husband could continue giving his Torah lectures … she suffered indescribable poverty and want (Yom LeYom 18 August 2009).

Their penurious state is clearly illustrated in the following description, which has been related in various places since Margalit’s death:

To publish his first book [Margalit] gave their savings intended for buying a closet for the house… She ensured there would be quiet in the house… all to preserve the rabbi’s serenity… (Yom LeYom 18 August2011)

Margalit Yosef devoted her life to her husband becoming an important rabbi. She relinquished her desires, aspirations, and comfort for his sake. There is not a single word of criticism or amazement regarding the lack of gender-based equality and her choices. And despite the one-dimensional model she presents, the obituaries paint her as a figure to be emulated. Such a paradigm can be marketed only when the party completely controls the newspaper. However, this model does not precisely match that of the immigrant women during the 1950s. Margalit grew up and married before the establishment of the state. Therefore, the family had no financial support and her husband had to both study and earn a living. After Shas was founded, it joined the coalition and achieved an extensive budget from the government, which assisted the society of learners financially. It was only through this that the party could create a society wherein the women supported their families.

The following obituaries about two other women fit the model marketed by Shas—relinquishing one’s personal life and nurturing a male Ashkenazic world of Torah.

4.3.2. Rachel Batzri

Before Rachel Batzri’s marriage, her future husband wanted to become a Torah scholar and knew that meant a life of poverty. He asked her:

‘What will you do if our income is insufficient?’ She answered with Jewish humility, ‘I’ll wash floors and stairwells, and you won’t lose a moment of your spiritual elevation in Torah … Around two years after their marriage … they moved … to the unknown … to a town in southern Israel, far from her family and friends. (Yom LeYom 18 April 2013)

4.3.3. Esther HaCohen

She wished to assist her husband, who was a Torah scholar and righteous man, devote himself to Torah and deeds of kindness … Anyone who entered her home saw how she was satisfied with little … She would refuse to accept gifts people brought her. She always wanted only to give to others … At the age of fifty-five she resolved to learn how to read, so that she would be able to pray from a prayer book. (Yom LeYom 10 September 1999)

The motif of women relinquishing their personal lives and following their husbands to far off places to enable them to study Torah appears in most of the obituaries. The obituaries describe the women only immediately before their marriage and once married. They discuss their contribution to the community, religious scholars, and their children’s education.

The picture gleaned is that the men studied only religious texts. This, despite the fact that when the immigrants had come to Israel the yeshivah world had been very small, and barely funded by the state. Furthermore, most male immigrants and their children worked, with the women serving as homemakers. This was in contrast to today, when hundreds of thousands of young men study Torah and receive a stipend from the state and charitable contributions obtained by the yeshivah.

Through such obituaries, the party blurs Zionist history and advances a feminine model that never existed. In practice, most women could not read or write Hebrew, as Esther HaCohen, and had to work in jobs that entailed poorly paid physical labour.

The women were awarded obituaries in the newspaper thanks to their positions as the elite of the party, wives or daughters of rabbis or politicians—or due to helping the party. shows the distribution of the obituaries according to women’s “role” or status and type.

The findings demonstrate that “ordinary” women were almost never awarded obituaries in the party newspaper. The obituaries are a means used by the party to shape an ultra-Orthodox society in which boys and men are expected to study Torah. The women were the tool for the social change.

4.4. The political influence on the second-generation women

The obituaries of the first-generation women hint to the Shas Party’s hidden agenda: shaping the second-generation to be more Orthodox than their parents, wherein men were expected to study Torah and women were expected to support them. However, the “tools” it possessed—a poor immigrant society with little education, particularly among the women—required a new social construct. Therefore, the party chose to emphasise in the obituaries only the characteristics which would help it shape a new society. Consequently, the obituaries do not describe the daily life of the women in particular or of the society of immigrants in general, but rather may be viewed as a political aspiration. The new social construct of the Shas Party is a dynamic process in which first-generation women immigrants nurture the men’s Torah study. In this manner, they define the new constructs to future generations (Adoni and Mane Citation1984; Boudreau, Citation1986).

The second research question discusses the hidden hegemonic message. Does the party succeed in creating a new social construct in late-twentieth century and early twenty-first century Israel? This question is examined through overt means—the party manifesto and interviews with second-generation women immigrants.

The Shas Party manifesto is an example of how an ideological vision is shaped. Shas’s platform includes a section entitled “Empowerment of Women,” outlining the party’s vision for improving women’s status through education and employment. This holds true especially outside the community, so as to “break out of poverty and distress, [and] take their place in society with positions of economic strength and strong self-esteem.” The section includes modern concepts of empowering women intended to advance and promote the status of the second-generation women, in order that they not be like their mothers, who lacked education and worked in straightforward manual labour. In reality, the party adapted the platform to the situation already in existence, in which many Mizrahi women acquire a profession or academic education, and achieve employment in the general Israeli labour market (Feldman, Citation2007, Citation2020a), while slowly adopting changes that it could combine with its sociopolitical values (Gitlin, Citation1978, Citation1979; Gramsci, Citation1992).

Therefore, the second question of this article is: How do the second-generation women operate, and do they seek to breach the traditional boundaries? To answer this question, we must achieve familiarity with three famous women as examples.

4.4.1. Adina Bar-Shalom

Adina Bar-Shalom is the eldest daughter of Margalit and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (her parents emigrated from Syria and Iraq to Israel). In 2000, with her father’s encouragement, she founded an academic college for women that awarded university degrees within an ultra-Orthodox framework. Within ultra-Orthodox society in Israel, there is gender-based separation during religious and social activities, including in the education system, from preschool onwards. As a result, in the past, ultra-Orthodox women rarely enrolled in universities. Bar-Shalom’s innovation was offering an academic framework suitable to their requirements. Before the college commenced operations, no academic framework existed for ultra-Orthodox women wishing to study in a gender-separated environment, other than teaching seminaries or learning a trade.

In 2014, Bar-Shalom was awarded the Israeli establishment’s two most important awards—the Israel Prize for lifetime achievement, and the honour of lighting a ceremonial torch on Independence Day. On receipt of these awards, she emphasised her aspiration to strengthen the society of male learners—a society in which married men study Torah while their wives support them financially.

I later asked her if she had not felt that it was problematic to speak in this way at a state ceremony. She replied, “I believe this is the best way for someone able to study Torah. So did my father.” Bar-Shalom remained committed to the Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox values. The state’s embrace and esteem have not changed her views on the importance of the male Torah world. However, in practice, her father Rabbi Ovadia Yosef both studied Torah and worked throughout his lifetime. He supported his family through employment, not charity. It is important to know that the model of the “society of learners”, adopted by the party and encouraged by Bar-Shalom, was not that of her own family.

The implication behind her words is that the purpose of the ultra-Orthodox College is in order to train women who would then have the ability to support a society of male learners. In this manner, she utilises academic education for women to reinforce the social order of the male Torah world. Not in order to break out of it, nor to demand gender-based equality. As a result, the party feels capable of accepting women with academic degrees who work in the general Israeli employment market.

Before the 2015 national elections, Adina Bar-Shalom stated that ultra-Orthodox women can be members of the Knesset (Israeli parliament), but only with rabbinical authorization. She did not question the rabbis’ political right to decide—nevertheless, she was greatly disappointed that she had been barred. Unlike educated women who contribute to strengthening the male Torah world, women in the Knesset clash with the male hierarchy, because they occupy men’s places. This is too extreme a change, and to date the party leadership has declined to authorise it.

4.4.2. Tzippi Yishai

Tzippi Yishai (her parents emigrated to Israel from Tunisia) is married to Eli Yishai, Shas Party chairperson from 1999–2013. She established three girls’ technological high schools and charitable organizations that help poor brides and families in crisis. During her husband’s term as chair, she organised women’s cultural conventions and managed the electoral campaign’s women’s division. Her personal desire is for her sons to learn in yeshiva and not to enlist in the army as their father did. When her daughters married, they learned a profession and found employment, but their husbands studied with a view to continuing in Torah-oriented employment. She explained to me that she believes every boy and man who is able to do so should study Torah, and only those who are unable to do so should go to work.

4.4.3. Liat Malka

Liat Malka (her parents immigrated to Israel from Morocco) is a social activist and member of her municipal religious council. She is a university graduate and leads a national project for a private company that establishes technological high schools for ultra-Orthodox boys. During the course of one conversation, she related to me some details regarding her son, who had finished yeshivah ketanah [a Torah study framework for high-school age boys]. “He excelled, but decided it has been enough and wants to go to the army.Footnote1 His decision is very difficult for us [for her and her husband]. We wanted him to continue studying Torah.” This is despite the fact that her husband works and never studied Torah full-time.

4.5. The new social construction: Women maintaining ultra-Orthodox values

Second-generation immigrant women from Africa and Asia support the traditional values marketed by the Shas Party. They do not rebel at the Social Construction painted in the obituaries, but instead support and buttress it. There is little difference between their aspirations and those of the first-generation women. Both desire the male “society of learners,” with the women providing financial support. This remains the case despite today’s women being more educated, earning more, and being active in the general Israeli arena. The second-generation women can ameliorate and upgrade their socioeconomic standing precisely because they do not question the men’s political position or attempt to the traditional patriarchal communal walls. Therefore, the party is able countenance their modernity.

These findings correspond with the study conducted by Margaret Bryant (Citation1979) on women’s entry into universities in England during the latter half of the nineteenth century. She demonstrates the manner in which women improved their social status and expanded their fields of activity, but did so without changing the social structure. On the contrary, they preserved it. The findings of this article also concur with the situation of Catholic women in the United States of America. They studied and worked in communal-religious frameworks and improved their personal status. Nevertheless, they effectively adopted and marketed the patriarchal values (Casanova, Citation2009).

The second-generation women identified with the Shas Party represent “conservative feminism” (Kabeer, Citation2005; Kabeer & Subramanian, Citation1996). Conservative feminism discusses women who are educated, enter the employment market, and advance economically and culturally. They have seemingly achieved equality within their communities, while actually maintaining male superiority and hierarchy. They are excluded from the communal centres of power, yet still choose to be members.

The second-generation women identified with the Shas Party are better educated and more independent than their mothers. They run academic and professional education systems in various areas of knowledge and throughout the country, but not religious studies. Despite their personal achievements, the second-generation women willingly accept the patriarchal structure, and the need for men to approve of their communal activity and acquisition of an academic education. Thus, they maintain the boundaries of the ultra-Orthodox society which were shaped through the obituaries, while also participating in general Israeli society.

There is an extensive study today in Israel about women in religious and ultra-Orthodox society who serve as agents of change within their communities. For example, girls from the Religious Zionist community enlist in the army in opposition to the opinions of important rabbis in their communities (Lebel & Masad, Citation2021). Ultra-Orthodox women who work outside their communities constantly examine their place and the abilities of their community to countenance the change which they promote. Most compromise, ask for their studies or work to be authorised by rabbis, or hide their activities from them, and sometimes even from their community or family (Gilboa, Citation2014/2015/2015; Kook & Harel-Shalev, Citation2020; Layosh, Citation2015). The similarity between them and the Mizrahi women lies in their being agents of change for Israeli society within the society in which they live. They are fully aware of the boundaries in their communities and try to make them more elastic, but without leaving the community. The difference between the Mizrahi and Ashkenazic women is that the Shas platform encourages the women to acquire an academic or professional education, with the goal of also being employed outside the community in order to support their families with ease and to strengthen the society of male Torah learners.

5. Discussion

Analysis of the obituaries according to the social construct approach reveals that they openly symbolise that which is self-understood—sorrow and sadness. And covertly emphasise the party’s political messages—shaping a society of men who study Torah. The primary assumption in the social construct approach is that reality has symbolic significance (Adoni and Mane Citation1984). Thus, the article examines how a party covertly moulded a social paradigm in which the roles of women are redefined from homemakers into those providing the financial support for their families, with the husband studying Torah as his main occupation. The weighty import which this study imparts to obituaries as a tool for shaping social construct is due to the hegemonic character of ultra-Orthodox media in Israel—one in which the political and spiritual leadership determine exactly what will appear in the newspaper (Caplan, Citation2001; Michelson & Zimmermann, Citation1990). Therefore, the first question in this article discusses the overt texts appearing within the obituaries: What are the characteristics of the new political feminine paradigm, shaped by the Shas party?

The research indicates that the characteristics of the first-generation women are found to be total devotion to strengthening the society headed by men who study Torah. With women’s role being to support them, and to agree to live a life of material poverty, in exchange for spiritual riches.

In addition, the covert goal of the obituaries is to shape a new social construct by means of a shift in awareness. The obituaries do not reflect the modern practice of the political platform, or the socioeconomic reality of the female party supporters today. But they are a political example to the second-generation, encouraging them to form their society to be as that of the Ashkenazic ultra-Orthodox.

The second question is, how do second-generation women operate within this model today? The question discusses the unwritten message of the obituaries (Heck, Citation1981)—How does a party intervene to change the awareness of its supporters and shape an ultra-Orthodox “society of learners,” according to the Ashkenazic model. To examine this question, I interviewed many second-generation women. All are socially active, with an academic or professional education, and involved in general Israeli society. The findings indicate that these women realise the party’s ideal of education, professionalism, and employment, as it appears in the “Empowerment of Women” section in the Shas political manifesto. However, similar to pioneering women in other traditional societies, we can see how the Shas party alters their awareness. The second-generation women use their talents to preserve, rather than change, the social hierarchy. The female Shas Party supporters are intended to maintain the new values of Mizrahi society—male Torah scholars. The party can countenance the modern women because they do not encroach upon the male elite and the social order as determined by men. In this way they resemble ground-breaking women in the Religious Zionist and ultra-Orthodox communities in Israel.

It is also important to understand that such social change for poor immigrants requires funding of a magnitude that only governments possess. For this reason, Shas has joined government coalitions since its establishment (Feldman, Citation2017a, Citation2020b).Footnote2 Thanks to its important position in the government coalitions, it has succeeded in obtaining large budgetary sums and legislative changes, allowing it to maintain its educational network and create a society of male learners which women can support with low salaries.

It is difficult to quantify whether the feminine model of the first-generation of immigrant women influenced those of the second generation. However, the mass return to religious life since the party’s establishment, and the aforementioned examples of three dominant women, hint to the widespread influence of the new political feminine model the party promotes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anat Feldman

Dr. Anat Feldman is a senior lecturer at Achva Academic College in Israel. Dr. Feldman specializes in research on the Shas party. Her recent publications on Shas party include: “The Shas woman: Social political boundaries” (2005), “The Shas Movement as a socio-cultural phenomenon” (2005), “The rise of the Shas Movement: Goals and activities” (2006), “Professionalization of women: The Shas Movement towards a new social political worldview” (2007), “Ethnic religion politics in Israel: The case of the Shas party” (2013), “The Establishment of a Political Education Network in the State of Israel” (2013); “The role of Haredi women leaders according to Shas party” (2017); “The determination of educational policy: Shas, politics, and religion” (2017); “Education and Employment among Ultra-Orthodox Women in Israel: Modernity and Conservatism—The Case of the Shas Party” (2020); “The shaping of a national educational policy through coalition agreements: How did the Shas Party establish an education network?” (2020).

Notes

1. Israel has mandatory conscription for boys and girls finishing twelfth grade. However, many are not conscripted for various reasons. One of those reasons is leading an ultra-Orthodox lifestyle and studying in a yeshiva for many years after high school.

2. There have been only two coalitions in which the party did not participate since its establishment, despite very much wishing to be part of the government.

3. Data are taken from Sikron (Citation1986).

4. Data are taken from Sikron (Citation1986).

References

- Adoni, H., & Mane, S. (1984). Media and the social construction of reality. Communication Research, 11(3), 323–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365084011003001

- Ben-Porat, A. (1989). Divided we stand: Class structure in Israel from 1948 to the 1980s. Greenwood Press.

- Boudreau, F. (1986). Sex roles, identity and socialization. In F. A. Boudreau, R. S. Sennott, & M. Wilson (Eds.), Sex roles and social patterns (pp. 63–83). Praeger.

- Brown, B. (2017). The Haredim – A guide to their beliefs and sectors. Am-Oved Publishers and the Israeli Democracy Institute.

- Bryant, M. E. (1979). The unexpected revolution: A study in the history of the education of women and girls in the nineteenth century. University of London.

- Caplan, K. (2001). Klei hatikshoret bahevrah haharedit B’Israel. Kesher, 30, 18–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23918731

- Caplan, K. (2006). Haharediut Hamizrahit Vehadat Ha’amamit: Shnei Mikrei Mivhan. In A. Ravitski (Ed.), Shas: Hebetim Tarbutiyim Veraayonim (pp. 443–483). Am Oved.

- Casanova, J. (2009). Nativism and the politics of gender in Catholicism and Islam. In H. Herzog & A. Braude (Eds.), Gendering religion and politics: untangling modernities (pp. 21–50). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cohen, Y. (1998). Pa’arim Sotsio-economi’im bein Mizrahi’im L’ashkenazim, 1975–1995. Israeli Sociology, 1(1), 115–134 https://kotar.cet.ac.il/KotarApp/Viewer.aspx?nBookID=97052880#4.1318.6.default.

- Cohen, Y., & Haberfeld, Y. (2004). Second generation Jewish immigrants in Israel: Have the ethnic gaps in schooling and earnings declined? In M. Semyonov & N. Lewin-Epstein (Eds.), Stratification in Israel – class, ethnicity, and gender (pp. 17–36). Transaction Publishers.

- Cohen, A. (2006). Periferiyah B’lev Hamerkaz. In A. Ravitski (Ed.), Shas: Hebetim Tarbutiyim Veraayonim (pp. 327–350). Am Oved.

- Doron, S. (2012). Mahsomey Zehut V’hadarah Betahalikh Hazarah Bitshuvah shel Mizrahim-Sefaradim. In K. Caplan & N. Stadler (Eds.), Mihisardut Lehitbasesut: Temurot Bahevrah Haharedit B’yisrael U’vehikrah (pp. 195–214). Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

- Ettinger, Y., & Leon, N. (2018). B’eyn Ro’eh: Shas V’hahangah Haharedit-Mizrahit aharey Idan Harav Ovadiah Yosef. Israel Democracy Institute. https://www.idi.org.il/media/10320/a-flock-with-no-shepherd-shas-leadership-the-day-after-rabbi-ovadia-yosef.pdf

- Feldman, A. (2005). Politikah, Etniut Umigdar: Irgun Hanashim shel Tnuat Shas. In T. Cohen & S. Regev (Eds.), Ishah Bamizrah – Ishah Mizrah: Sipurah shel Hayehudiyah Bat Hamizrah (pp. 295–314). Bar Ilan University.

- Feldman, A. (2006). Hakamat Tnuat Shas: Matarot Vedarkhei Peulah. In A. Ravitski (Ed.), Shas: Hebetim Tarbutiyim Veraayonim (pp. 405–442). Am Oved.

- Feldman, A. (2007). Hitmaktsut Nashim: Tnuat Shas Likrat Tefisat Olam Politit Hevratit Hadashah. Politikah, 16, 93–115 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23390812.

- Feldman, A. (2011). The establishment of a political-educational network in the state of Israel: Maayan Hahinuch Hatorani. Israel Affairs, 19(3), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2013.799863

- Feldman, A. (2012). Carnival by Night: A New Practice of Modern Tikkun Rituals. In Avi Sagi, Yedidia Z. Avi, Stern, Yedidia Z.,and Hanan Mandel, Hanan . Democratic Culture in Israel and in the World, 13 (The Israel Democracy Institute and Bar-Ilan University), 81–120.

- Feldman, A. (2013). Ethnic religious politics in Israel: The case of the Shas party. Religion and the Social Order, 23, 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004254756_013

- Feldman, A. (2017a). The determination of educational policy: Shas, politics, and religion. Israel Studies Review, 32(2), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.3167/isr.2017.320206

- Feldman, A. (2017b). ‘Hahzarat Atarah Leyoshnah’ o ‘Shinui Atarah Yeshanah’ – Tafkid Manhigot Haredi’ot Mizrahi’ot al pi Tnuat Shas. Heker Hahevrah Haharedit, 4, 81–103 https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/publications/%d7%9e%d7%a0%d7%94%d7%99%d7%92%d7%95%d7%aa-%d7%97%d7%a8%d7%93%d7%99%d7%95%d7%aa-%d7%9e%d7%96%d7%a8%d7%97%d7%99%d7%95%d7%aa/.

- Feldman, A. (2020a). Education and employment among ultra-orthodox women in Israel: Modernity and conservatism —the case of the Shas Party. Contemporary Jewry, 39(3), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-019-09304-3

- Feldman, A. (2020b). Itsuv Mediniyut Hinuch Leumit B’emtsa’ut Heskemim Ko’alitsyonim: Keitsad Hekimah Tnuat Shas Reshet Hinuch? Sugiyot Hevratiot B’yisrael, 29(6), 165–191 https://doi.org/10.26351/SIII/29-1/5.

- Feldman, A. (2020c). New sites for Rituals: Miracle seekers, burial sites, and extra-institutional religious leaders – Israel’s popular culture. In D. Sobolev & E. Nosenko-Stein (Eds.), Contemporary Israel: Languages, society, culture (pp. 116–154). Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Friedman, M. (1987). Life tradition and book tradition in the development of ultraorthodox Judaism. In H. E. Goldberg (Ed.), Judaism viewed from within and from without: Anthropological studies (pp. 235–256). SUNY Press.

- Friedman, M. (1988). Back to the grandmother: The new ultra-Orthodox woman. Israel Studies, 1, 21–27 https://faculty.biu.ac.il/~mfriedma/Beit-Yaakov.pdf.

- Friedman, M. (1991). The Haredi ultra-Orthodox society: Sources, trends and processes. Jerusalem Institute for the Study of Israel. https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/PUB_haredcom_eng.pdf

- Friedman, M. (1995). Ha’ishah Haharedit. In Y. Azmon (Ed.), Ashnav Lehayehen shel Nashim B’hevrot Yehudiot (pp. 273–290). Zalman Shazar Center.

- Gilboa, H. (2014/2015). ‘She bringeth her food from afar’: Haredi women working in Israel’s high-tech market. Heker Hahevrah Haharedit, 2, 193–220 https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/publications/%d7%a0%d7%a9%d7%99%d7%9d-%d7%97%d7%a8%d7%93%d7%99%d7%95%d7%aa-%d7%91%d7%94%d7%99%d7%99%d7%98%d7%a7/.

- Gitlin, T. (1978). Media sociology: The dominant paradigm. Theory and Society, 6(2), 205–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01681751

- Gitlin, T. (1979). Prime time ideology: The hegemonic process in television entertainment. Social Problems, 26(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/800451

- Gramsci, A. (1992). Prison Notebooks. Colombia University Press.

- Hacohen, D. (1994). Immigrants in turmoil: The great wave of immigration to Israel and its absorption, 1948–1953. Syracuse University Press.

- Halamish, A. (2006). B’merutz Kaful Neged Hazman. Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi.

- Hall, S. (1997). Introduction. In S. Hall (Ed.), Gender, race and class in media (pp. 18–23). Sage.

- Hamilton, J. T. (2004). All the news that’s fit to sell: How the market transforms information into news. Princeton University Press.

- Heck, M. C. (1981). The ideological dimension of media messages. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language: working papers in the cultural studies, 1972–79 (pp. 122–127). Hutchinson.

- Kabeer, N., & Subramanian, R. (1996). Institutions, relations and outcomes: a framework and case studies for gender-aware planning. Zed.

- Kabeer, N. (2005). Inclusive citizenship: Meanings and expressions. Zed.

- Kalagy, T. 2007. Shamranut U’petihut B’hevrah Fundamentalistit Mitbadelet – Hama’avakim Sviv Tahalikhei Akademetziah Bamigzar Haharedi B’yisrael B’reshit Hame’ah Ha-21: Hamkamah Mikhlalah Haharedit Yerushalayim [Master’s thesis]. Bar-Ilan University.

- Katzir, M. (1999). Ba’asher Telekh. Hazon Ovadia Institute.

- Kook, R. B., & Harel-Shalev, A. (2020). Patriarchal norms, practices and changing gendered power relations – Narratives of ultra-orthodox women in Israel. Gender, Place & Culture, 28(7), 975–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1762546

- Layosh, B. (2015). Darkhei Hitmodedut Shel Nashim Harediot Im Shinuyim Hamitholelim B’hevratan Bitkhumei Hahaskalah, Hata’asukah Vehap’nai. Heker Hahevrah Haharedit, 3, 26–55 https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/publications/%d7%93%d7%a8%d7%9b%d7%99-%d7%94%d7%aa%d7%9e%d7%95%d7%93%d7%93%d7%95%d7%aa-%d7%a9%d7%9c-%d7%a0%d7%a9%d7%99%d7%9d-%d7%97%d7%a8%d7%93%d7%99%d7%95%d7%aa-%d7%a2%d7%9d-%d7%a9%d7%99%d7%a0%d7%95%d7%99%d7%99/.

- Lebel, U., & Masad, D. (2021). Life scripts, counter scripts and online videos: The struggle of religious-nationalist community epistemic authorities against military service for women. Religions, 12(9), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090750

- Lehmann, D., & Siebzehner, B. (2006). Remaking Israeli Judaism – The challenge of Shas. Hurst Company.

- Lemert, J. B. (1984). News context and the elimination of mobilizing information: An experiment. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 61(2) , 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F107769908406100201

- Lemert, J. B. (1992). effective public opinion. In J. D. Kennamer (Ed.), Public opinion, the press, and public policy (pp. 41–61). Praeger.

- Leon, N. (2006). Hatesisah Haharedit B’kerev Hayehudim Hamizrahi’im: Temunot Etnografiyot Me’ashnav Bet Haknesset Ha’adati. In A. Ravitski (Ed.), Shas: Hebetim Tarbutiyim Veraayonim (pp. 165–193). Am Oved.

- Leon, N. (2009). Harediut Rakah: Hithadshut Datit B’yahadut Hamizrah. Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi.

- Lissak, M. (1986). Medini’ut Ha’aliyah Bishnot Hahamishim. In M. Naor (Ed.), Olim U’ma’abaraot 1948–1952 (pp. 9–18). Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi.

- Lissak, M. (1999). Ha’aliyah Hagedolah Bishnot Hahamishim – Kishlono shel Kor Hahitukh. Bialik Institute.

- Lupu, J. (2004). Shas de Lita: The Lithuanian take-over of Moroccan Torah scholars. Hakibbuts Hameuchad Publishing House.

- Michelson, M., & Zimmermann, A. (1990). Itonut Haredit B’yisrael. Kesher, 8, 11–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23902877

- Sharaby, R. (2009). Hag Hamimunah: Mehaperiferiyah el Hamerkaz. Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

- Sikron, M. (1986). ‘Ha’aliyah Hahamonit’ – Memadehah, Me’afyanehah V’hashp’otehah. In M. Naor (Ed.), Olim U’ma’abaraot 1948–1952 (pp. 31–52). Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi.

- Walter, G., & Wilson, S. (1996). Silent partners: Women in farm magazine success stories, 1934–1991. Rural Sociology, 61(2), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1996.tb00618.x

- Weingrod, A. (1990). The Saint of Beersheba. SUNY Press.

- Wood, J. T. (1998). Ethics, justice, and the ‘private sphere’. Women’s Studies in Communication, 21(2), 127–149 https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.1998.10162553.

- Yadgar, Y. (2010). Hamasortim B’yisrael: Moderniut lelo Hilun. Bar-Ilan University.

- Zameret, Z. (2002). The melting pot in Israel: The commission of inquiry concerning the education of immigrant children during the early years of the state. SUNY Press.

- Zohar, Z. (2006). Shloshah Tipusim Idialiyim. In A. Ravitski (Ed.), Shas: Hebetim Tarbutiyim V’ra’ayoniyim (pp. 152–164). Am Oved.