Abstract

The study sought to answer: How can participatory and visual methodology enable women teachers to lead change against intimate partner violence (IPV) at a state university in Zimbabwe? The study was qualitative and informed by the critical paradigm and employed visual participatory research methodology. Six women educators from a state university were selected by means of snowballing. The methods of data generation that were employed were drawings and focus group discussions. Data generated from the drawings depicted the participants’ positioning and how they are positioned in intimate relationships. The findings indicated that the participants understand intimate partner violence as a complex issue and through their voices can initiate change by breaking down barriers as they address the issue. The participants also indicated that gendered social structures affect intimate partner relationships. The women educators are actors who are aware of intimate partner violence and can participate and inform intervention programs. The study concludes that using participatory visual methodology (PVM) provided a safe space for the women to talk about intimate partner violence and propose solutions to a phenomenon that has always been a taboo.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Women remain vulnerable to intimate partner violence and there seems to be complicity to perpetuate gender-based violence against women as there is weak implementation of the law enacted to protect women from violence. The study redefines the gender narrative by exploring the experiences and understanding of intimate partner violence by women educators. The work explores how a wide variety of perceptions of what it is to be a woman in an intimate partner relationship are depicted through the drawings of a cactus, the bright sun, a stone on a woman’s head, an eagle, a pilot and a river. The use of participatory research techniques to meaningfully engage educators are a valuable contribution given the gap in women centered research methods to address intimate partner violence. The study observes that culture and religion among other factors continue to disadvantage most women in Africa from enjoying universal human rights.

1. Background and statement of the problem

The study explored intimate partner violence against women educators and the critical steps that can be taken in the fight against IPV. The study was carried out in a state university in Zimbabwe. Gender- based violence (GBV) occurs in both the public and private spaces of women and men’s lives. GBV maybe perpetuated by institutional practices and policies, for example, the military, immigration authorities, the courts and police officers. Globally, violence against women is recognized not only as a health concern but also an economic development and human rights issue. (UN, Citation1993; WHO, Citation2001). Domestic violence is prevalent in most of sub Saharan Africa with a prevalence of 36% above the global prevalence of 30% (Lasong et al., Citation2020). A report by the Women’s Coalition of Zimbabwe and Stopping Abuse and Female Exploitation and Zimbabwe Technical Assistance Facility (2020), intimate partner cases increased during the lockdown. The report further indicates that partner perpetration of violence increased from 68% of all reports with an identified perpetrator in 2019 (March to May) to 71.1% in 2020 (March to May).

The term IPV describes “physical violence, sexual violence and psychological aggression by a current or former intimate (Garcia-Moreno et al., Citation2005, p. 15). Russo and Pirlott (Citation2006, p. 184) focused their work on gender- based IPV, which “encompasses acts performed by an intimate partner that include physical, sexual and emotional abuse”. Mama (Citation2004) includes other aspects not covered by Garcia-Moreno et al. (Citation2005) and Russo and Pirlott (Citation2006) in her definition of the phenomenon. She explains gender- based IPV as including other forms of sexual coercion that restrict and control one’s freedom of action and forced intercourse.

Much of the work to combat domestic violence in Africa is shaped by the international feminists’ movements’ campaigns, whose efforts cascaded to Africa and influenced how GBV is addressed (Burrill et al., Citation2010, p. 11). The Zimbabwean government adopted several criminal law measures to protect and advance the rights of women and protect them from GBV as guided by the UN CEDAW article 5 and AU Charter Article 2 (d). The domestication of elective protocols that Zimbabwe acceded to has been hindered by poor implementation, administrative practices by the state and non-state institutions (Mukamana et al., Citation2020). However, culture and religion, among other factors, continues to disadvantage most women in Africa from enjoying universal human rights, hence the need for the protocol to focus on women’s human rights (Adu-Gyamfi, Citation2014). The African Union feels that CEDAW may not adequately address these needs.

To advance the argument further, Burrill et al. (Citation2010) hold that global human rights discourse has not been translated into local or national discourses. Merry, Citation2013) posits that international discourses fail to fit into local discourses about dignity, equity and emancipation. This resonates with observations made by Duramy Faedi (Citation2014) that regionally- based human rights courts and commissions would help to close the “local cultures gap” that often delays the implementation of local and regional legislations. These observations pertain to Zimbabwe in that recourse to customary laws and practices implies that the law and society do not protect women survivors of IPV. As a result women may be reluctant to seek legal assistance, as they distrust the law and related institutions. Such pertinent issues are rarely, if ever, addressed by mainstream white feminism and such injustices and inequalities are perpetuated.

In a study by Chuma and Chazovachii (Citation2012) found that law enforcement agents treat domestic violence as an issue in the private sphere and as a result women remain vulnerable to IPV (Musingafi & Tom, Citation2013). Similarly, findings from a study by Fidan and Bui (Citation2016) in Zimbabwe indicate that gender relationships have an important role in violence against women as husband’s patriarchal behavior increases the likelihood of violence. Bhattacharya (Citation2009, p. 272) asserts that “forms of violence against women that don’t fall strictly within state defined categories of violence are globally, typically identified as personal concerns”. This can be viewed as complicity to perpetuate GBV against women because there is weak implementation of the laws enacted to protect women from violence. According to Nigam (Citation2014, p. 199) “the police, the lawyers, the judicial community all appear to be colluding against a woman who … steps out to share her ordeal of violence”. She is often reminded that the matter is a private one and should remain thus. The media in Zimbabwe and Africa pay little attention to issues of intimate partner violence and project them as private issues that the affected parties can solve (Mukamana et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Sithole (Citation2007) holds that from a cultural perspective the law should not interfere with family matters as the traditional leaders argue that the family unit is sacred. In some instances, the use of GBV against women is tolerated by the local community which views male use of violence as way to control women (Ayedapo et al., Citation2017).

Variations in cultural context that exist throughout the world make IPV a complex issue (Attteraya et al. Citation2014, p. 2339). Temmerman (Citation2015) confirms that gaps still exist in research on GBV as the phenomenon largely remains hidden and ignored. This resonates with Tamale (Citation2011) observations that discourse on sexuality reflects realities and experiences outside Africa. In a study conducted on IPV in Liberia, Allen and Devitt (Citation2012, p. 3517), opine that “religious beliefs and local cultural belief systems define power hierarchies between women and men which support violence against women”. Studies (Abrahams, Matthews, Jewkes, Martin and Lombard, Citation2012; Machisa et al., Citation2011, Watson, Citation2015) indicate that IPV is prevalent in South Africa. Similarly, Abbi and Lul (Citation2010, p. 437) posit that violence against women is a problem that is accepted and goes unchallenged in Ethiopia. Therefore at societal level, a lot still needs to be done to deal with issues of masculinity and tolerance of physical punishment. In addition, the political landscape needs to open up more for women so that their participation in these spaces can lead to changes in the criminal justice systems and enforcement of legislation pertaining to GBV. Fite (Citation2014) furthers the discussion by arguing that there are no specific “remedies for victims or survivors such as the right to obtain protection order, monetary compensatory relief, shelter or medical benefits”. The Spotlight Initiative launched in 2019 aims to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls in Zimbabwe and seeks to ensure improved legislation and policies, violence prevention institutions among other measures (https:www.spotlightinitiative.org). This means that as much as legal frameworks have been put in place, on domestic violence against women, what remains contentious is the implementation of the said laws, whereby no provisions that protect the survivors were put in place.

In Zimbabwe, violence within the marriage institution is common and widely tolerated and the vulnerability of women to violence is compounded by their lack of power and lower status in the family (Ayedapo et al., Citation2017; Wekwete et al., Citation2014). Similarly, violence may be used to enforce gender norms and often on women who fail to perform expected domestic chores. This in a way legitimizes violence as a form of social control over subordinate family members and may perpetuate hegemonic masculinity. As a result, the women may accept GBV as normal in that she may underplay the impact that violence has on her (Bennett (Citation2010). The Zimbabwe Gender Commission Chairperson noted that though legal and policy frameworks are in place, structural barriers to gender equality and gender- based discrimination still persist in the country (Country Policy and Information Note: Zimbabwe women fearing gender based harm or violence, Citation2018).

Fulu et al. (Citation2013, p. 106) discuss how violence against women may also be triggered by men’s perceived disempowerment in environments in which rapid social and economic structural changes impact perceptions of women’s and men’s roles and rights within society. Women have gained increased financial and decision making power through formal employment but for social and economic reasons these women do not necessarily leave abusive relationships (Fulu & Miedema, Citation2013). This includes how abusive men tend to restrict women’s contact with people outside the home and restrict the women’s movement to the confines of the private sphere (Sitaker, Citation2008). In her personal narrative on IPV, Sweetnam (Citation2013, p. 135) explains thus, “ … in addition, my abuser did not want anyone feeding me ideas that threatened the authority I gave him”. This illustrates that abusers are controlling and want to ensure the victim has no outside assistance. The woman may withdraw from interacting with family and friends as a result, not because she wants to, but because the perpetrator enforces it through isolating and controlling the victim’s movements and relationships with family and friends. The use of participatory research techniques to meaningfully engage women educators is a valuable contribution given the gap in women centered research methods to address intimate partner violence in Zimbabwe.

2. Theoretical framing of the study

Critical theory informed the study as the researcher and participants are interactively linked (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1994) as the participants interrogate intimate partner violence. This resonates with Price’s (2007) assertion that in critical research, knowledge is not objective but subjective, as values and power are keys to shaping what is deemed knowledge. The production of knowledge is enhanced through involving the critical voices of the participants so that they are heard and acknowledged (Taylor & Medina, Citation2013). The research was interventionist in its thrust reflecting the critical stance of the post- modern feminist theory which adopts a transformative approach in a bid to achieve gender equality.

Transformative feminist research addresses the relationship between structural oppression and lived experiences, between the public and personal experiences (Walby, Citation2005). It becomes imperative to explore how intimate partner violence is reproduced and recreated in the personal spaces of the female students/ educators in a state university. In other words the participatory processes in the study can support and promote awareness as the participants engage in self-inquiry of their acknowledged vulnerabilities (Bhattacharya, Citation2009) in the face of intimate partner violence.

African feminism also informs the study as it interrogates the negotiation for voice and recognition of African women. It is a feminism that stands for “voice, personal integrity” and recognition of women’s productive and reproductive labor (Shaw, Citation2017, p. 14). Thus the voices of the “silenced and oppressed” (Heise-Biber, Citation2014, p. 3) in the private space of “gendered power struggles” (Bennett, Citation2010, p. 29) are explored in the lived reality of intimate partner violence. The implication of this is that the theory should speak to the lived experiences and knowledge of the subject as well as creating knowledge and enhance transformative social change (Tamale, Citation2011). It is against this background that the study interrogates the gendered power relations that perpetuate intimate partner violence and provide an avenue for women educators to participate in an empowering process of self-reflection and voice in a traditional context.

3. Research design and methods

The study adopted the qualitative feminist approach as it sought to explain the social phenomenon of IPV as it was experienced by women educators (Malterud, Citation2001). The study is a narrative inquiry, which allows for a story or narrative to be told and is an appropriate way to collect data about lived experiences. The qualitative feminist approach allowed for in depth exploration of direct experiences, attitudes and perceptions of intimate partner violence.

The study explored how the participants see themselves as wives and partners in intimate relationships and to do this each research participant came up with individual drawings. The individual drawings formed the basis of the first data sets which the participants presented as they made sense of their understanding of IPV. In total it was envisaged that each participant would present two sets of drawings. The participants gave explanatory details on the drawings during the group discussions that were conducted. In doing so they were making sense of the data. Each participant was given a prompt which is summarized as follows:

Drawing prompt

1. Make a drawing that depicts how you see yourself as a woman within an intimate relationship in the first prompt.

2. Make a drawing that depicts how you are positioned as a woman in an intimate relationship in the second prompt.

3. Write an explanation of what the drawing means to you and why you made the particular drawing for the two prompts.

Furthermore, the participants engaged in focus group discussions which according to Madriz (Citation2000) serve to explore and validate women’s everyday experiences of subjugation and resistance strategies and the participants shared their stories in a group. As with qualitative feminist research, the thrust was to privilege women’s voices in the identification of issues and measures to address them rather than the usual experts (Moletsane et al., Citation2009) who give voice to the women’s lived experience. The focus group discussions centered on what the drawings meant for the woman. The participants explained how each woman sees herself as a partner and how the women educators viewed themselves. The explanations were in the context of IPV. The participants were requested to explain what the drawings conveyed in writing and verbally (Mitchell, Citation2011). As they explained the depictions during the focus group discussions, the participants were co-analysts of the data, thereby heightening the trustworthiness of the data analysis process (Theron, Stuart and Mitchell, Citation2011).

Snowball sampling technique was adopted to select the six research participants. The first participant who is a student and educator was approached during the course of her studies. The participant agreed to participate in the study and identified the second participant. The women participants’ ages ranged from 35 to 46 years. The researchers explained to the participants the objective and nature of the study so that they could decide whether to take part or withdraw from the research. After assuring the research participants of confidentiality and privacy of the information they would provide, they were encouraged to complete consent forms. Pseudonyms were used. The researchers removed identifiers so that participants’ identities were protected when communicating the findings. The participants also voluntarily agreed to allow the researchers to use their narratives that are a result of their participation in the study.

All data was transcribed and patterns and themes were derived inductively (Creswell, Citation2014). The transcribed data was taken back to the participants to verify and clarify particular issues raised. Emerging themes were identified which related to the lived experiences of the women. During the inductive analysis, the data were organised, encoded and categorized thematically. The categories formed broad themes which were consistent with the research objectives.

4. Findings

O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, and Cook (Citation2014) postulate that for ethical research practice, the participants become part of the “sense making processes” as they are co-analysts of the data generated. The participants explained their portrayals in varied depictions. shows these depictions: and the participants’ profiles. presents biographies of the participants, a summary of the depictions of the woman as a partner and how the woman sees herself. The participants’ understandings of their positioning were informed by the social context in which the abusive experiences occurred as shown by their explanations which follow.

Table 1. Participants’ biographies, partner and how the woman sees herself

4.1. The cactus—Sharai

A cactus is a plant that survives under harsh conditions. I am surviving under harsh conditions. It has rich nutritional components. It can be found in dry land but in the gardens too. It is prickly and has thorns. (see F1) It can hurt if one touches it. When it rains it saps up water and keeps this water when it is dry. In other words it has reserves. It is used for medicinal purposes but is poisonous.

I am surviving under harsh conditions of gender-based violence. I am surviving where no other woman survives. I am misunderstood by many as I remain in this abusive environment. Like the cactus I survive under all weather conditions where other plants and vegetation may dry and wither in summer, I am resilient. Other women have left their abusive husbands but I have this strength to go on—to endure another season. I am quite adaptive. My husband admires my resilience and patience with him. My spikes can hurt though when I want to protect myself from danger.

4.2. The sun—Chipiwa

The sun is the source of energy and life to plants, animals and people. It is not selective about with whom to share its rays, both good and bad. It is constant and an ever present presence. At its brightest it can destroy with its ultra violet rays.

I am like the sunshine amongst all the ordeals I face in life. I believe no one and nowhere can I be outshone. My husband, my in-laws and my friends are in my shadow. I outshine them all. I have made it and I am a victor. I share with them all. The sun shines on all who are in its path so I touch many lives and I do not discriminate.and Chipiwa demonstrates this assertion in a depiction of the sun in F2.

4.3. The eagle—Hope

The eagle looks after its young up to a certain period. It teaches the young how to hunt for prey, how to fly, how to build a nest. It passes its wisdom to the young. It flies close to the sun.

I am in this relationship for my children. I am preparing them for their future and I do not want them to be abusive like their father. I am cunning like the eagle, which flies so high in the sky and then swoops down on its unsuspecting prey. Each time it hits the jackpot and scores a meal. As a partner, I am feeding the children alone but my husband is uninvolved. I do not think he realizes what he is doing to the children whom he neglects. To him I am like a speck in the sky, he does not consult me on issues to do with the family upkeep. He does everything alone except when he wants sex. I am a loner like the eagle that hunts alone. I feel lonely and alone yet I am married. Hope’s drawing of an eagle is shown in F3.

4.4. A woman carrying a heavy stone on her head—Kuziva

A stone is generally heavy and a strain to carry. It is burdensome. It is an unexpected sight to see someone carrying a stone on their head. For me the stone represents the pain that I endure in the marriage. I have faced more trouble than love, misunderstanding than understanding, pain than love. I am isolated, I am alone. It is burdensome. My life is crumbling down. My self-esteem is low and my stress levels are quite high. I am under strain and it is weighing me down just like carrying a stone can weigh one down. I cannot move as I do not have feet. My feet were rendered useless by the environment I live in. My husband has cut off my feet, as he does not want me to go anywhere without him. So we go together and I cannot tell my relatives about the abuse, as he is so good to them. My heavy burden remains unsupported by anyone and it gets heavier and is weighing me down. I wish my feet could grow again. But how did I allow him to render my feet useless? I will get back on my feet. But why is it I cannot walk, I cannot put down this heavy load, why?

I see, I hear, I have hands to hold and touch but I cannot fight physically. I have no feet so I am immobilized. I am immobilized in my fear of my husband. Where can I go without feet? I can crawl. I have no mouth to speak. I cannot articulate the issues that affect me. Even though I cannot speak, other people speak on my behalf and in so doing I fight back through them. I hear quite a lot when my husband tells me what to do. He takes me where he wants to take me. He decides on my behalf. I used to think it is normal for the man to decide everything but I see and hear differently. I have to speak out. the depiction of the stone is shown in F4.

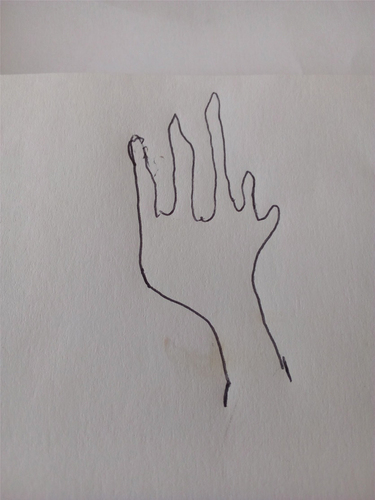

4.5. The hand and its fingers—Chiedza

The hand and its five fingers are disembodied. This implies no connection with the body it belongs to. It has been disconnected from its life source—the rest of the body. This is shown in F5. However, on each finger is written the following: wife; mother; friend; teacher and daughter-in-law.

The five relationships I identified portray who I am. I am a wife and a mother. These roles have their demands and I sometimes forget I am a partner in a relationship. I love my job and it keeps me sane. My responsibilities and roles as a daughter-in-law complement my roles asa wife. As in our Shona custom, I am a wife to my husband’s five brothers and his two sisters behave no differently from the brothers in their expectations of the in-law’s roles. The disconnection I feel is that I am quite far from my immediate paternal family. I am disconnected from my husband, as he sees me as a wife and the mother of his children. He does not see me as a partner. The connections are there but the circumstances of my life in an environment of gender-based violence have rendered me to feel like I am groping in the dark. My support base is nonexistent from my husband and in-laws. I hang on and look after my children and I do not want to expose them to further trauma of a disintegrated family. I cherish my role as their mother and I want to keep them under a family unit that is intact.

5. How the women are positioned in intimate relationships

The participants interrogate how they view themselves as women in the following excerpts.

5.1. The elephant—Sharai

The elephant is a beautiful and strong animal. An elephant I am told is pregnant for 22 months. That’s strength and endurance. Imagine carrying a young one for close to two years. An elephant reaches sexual maturity at 9 to 12 years and the cow can get pregnant at 13 years and may remain fertile in old age. I realize I am strong and have endured hardships in my marriage. I am able to withstand any pressures, although society may restrict me with its taboos and norms. My mental capacity and strength stand me in good stead and I am a beacon of hope in my family and social networks. I am larger than the challenges I face.

5.2. The baobab tree—Chipiwa

A baobab tree is a big tree in its maturity. It survives in dry lands. It produces fruit that is used by both human beings and animals. The tree stands in its majesty providing food, shelter and a source of income for those who harvest its produce. The tree has many sturdy branches.

I see myself as this gigantic tree that spans its wings far and wide. My roots are firmly planted in the (ground of the) family I married into. After all, I have three sons and this has secured my place as a wife and mother. Like the baobab tree, I survive in dry lands and am a mother, a daughter-in-law, a wife, a sister-in-law, a teacher and an entrepreneur among my several roles. From all these multifaceted roles I produce results, which are my fruits. My husband takes me for granted just like people take any fruit producing tree for granted and only remember the tree’s existence and importance when it bears much fruit in its season. When my husband is broke, he remembers my extra stream of income and any other reserves I have, so that the financial problem can be resolved.

I am resilient like the baobab tree and I do not bow down to the challenges of life and relationships. Equally, my in-laws undervalue my contributions as a professional, in their eyes I am an in-law, wife and mother. When he beats me he is exercising his right as my husband and I should not complain but endure. That is why I see myself as a baobab tree. I am a fixture in their lives and I should not run away from any problems, be they marital or otherwise. After all, a neglected tree can still produce some fruit when it is in season, as it may use some of its reserves to replenish itself so that people continue to feed from it.

5.3. Revolving door—Hope

In most buildings there is a revolving door, which if you do not get out when it is your time to do so, the door continues to revolve with you inside. It makes it easy for those coming in and going out to be at different points as the door revolves. I see myself as a revolving door and that depicts my life that is revolving. I often find myself in the same spot where I am restricted by custom, which forces me to stay in this relationship. The way out is there but the impetus to do so is not there. I ask myself, where would I go? After all I have several children and divorce is frowned upon in my community. Life goes on. Each time I want to get out, my children hold me back, because I know my husband and his family would not let me take them with me.

5.4. The good wife—Kuziva

A good wife in my society is caring, loving. She is a good influence, can influence good behavior in the husband. A good wife loves everyone, she is not lazy, she does not complain. My husband is the head of the family so I must submit to him. This implies I have no power, as my husband has the power and authority to make decisions without my input.

I agree with my husband’s decisions as a submissive wife and I am loyal. I look after the family, cooking, laundry and all household chores. The man has power and leadership in the home. I implement his decisions. I do not make financial decisions. I help the man. He has power over me. A good wife normally has a homestead in the rural area and this is symbolized by the hut.

5.5. A river—Chiedza

A river in a community has a number of uses, water for drinking, bathing and watering crops. Both animals and people depend on a water source. If the water source dries up, in times of drought there are challenges.

I see my woman self as a river, because I have many gender roles in my household and community. I am a source of comfort to my children and husband. I look after the family’s emotional, social, economic and spiritual needs. I am a pillar of strength in my multiple roles as a mother, wife, neighbor, in-law, daughter and sister. In Shona we have a saying “musha mukadzi” (a wife makes a home). As a river, one may not see the source, but sees the portion of the river that passes through their locality. My husband does not realise the source of my strength, as he is unaware of my capabilities. When he sees me quietly going about my business, he does not realise still waters run deep. He may abuse me like people do as they pollute water sources, which continue to be their source of livelihood, even if the source is polluted. I discharge my duties well.

5.6. A pilot—Venekai

A pilot in an airplane is at the controls in the air, although he or she is always in contact with the ground crew. The pilot works with the co-pilot and is in charge of a large number of lives for the duration of the flight.

I see myself as a pilot in my relationship. I make decisions that affect my family in all aspects of their lives. I am responsible for anything that may go wrong in their lives. I have to be in constant communication with the co-pilot and ground crew but they sometimes let me down. For example, my co-pilot, my husband, has often let me down when his eye wanders and he has relationships with other women. We have had turbulence in the weather and near fatal crashes in our relationship but with the grace of God we have survived the turbulent times. The ground crew, my children, is very helpful as a support mechanism that has kept us on course. My children are my cheerleaders who cheer me on each time I land safely on the tarmac.

6. Discussion

The drawings were discussed by all the participants during the focus group discussions to explore the women teachers’ positioning in intimate partner relationships. The following themes were identified: the power of a woman; women as nurturers, women as appendages and women as sexual beings.

6.1. The power of a woman

The resilience, strength and not giving up of a woman is portrayed in the metaphors of the cactus and the eagle. The women survivors of sexual coercion cope with abuse in various ways. The women have adopted coping mechanism of silently enduring the gender-based violence for the sake of the children. The custom of lobola has increased in value and bestowed more control on the man over his wife which has changed and shaped household relationships (Burrill et al., Citation2010).

The portrayal of the sun is another metaphor that attests to the power of the woman. She is the sustainer of life. The woman seems unable to separate her role as a partner and conveys the message that in Shona marriages, the roles of a wife, mother and daughter-in-law are of paramount importance. This resonates with findings made by Kambarami (Citation2006, p. 4) that for most Shona women the desired destination is marriage.

I travel to Botswana to buy goods for resale at my school. The extra income I get helps me to pay for my sons’ school fees.

I sell second hand clothing and I realize quite a profit. This supplements our incomes.

It is good to have another stream of income and not to rely on the monthly salary. I am a representative for one of the beauty products companies and I take orders from people and sell for a marginal profit.

The idea of having another stream of income is quite empowering, as the women are not totally dependent on the spouses’ income or their own salary. Such a paradigm shift is necessary given the economy of the country. They engage in empowering activities that enhance their livelihoods and this speaks to their resilience and strength in an adverse economic environment.

The feminist post-structural perspective argues that the social context in which an individual finds herself informs her interpretation of events and several meanings can be garnered from the events (Goldman and Dumont, 2001 as cited in Dekel & Andipatin, Citation2016). The metaphors of the river, the baobab tree and the elephant depict a woman who has strength to withstand the challenges she faces. The women are able to survive IPV because inherent in them is an inner strength and an acknowledgement and realization that they possess a deeper strength that enables them to endure. The participants say:

I draw on an inner strength, a power that enables me to survive.

I often wonder how I have survived this long in this relationship. I never thought I had it in me to endure for so long and not give up on my marriage.

It is tough and it has been tough but I am holding on.

However, despite the restrictions of taboos and custom, the participants were aware of their strength to break free and speak out. This implies that culture is contested, changing and is influenced by history (Burrill et al., Citation2010). The women’s resilience is reframed within the local context where gender socialization constructs the belief that despite the marital problems one remains in one’s marital home. Some of the rules and norms in the matrimony may include not talking about gender-based violence in public but enduring it in the private space as “a good wife” and by extension, a “good mother”.

6.2. Women as nurturers

All the depictions that the women presented demonstrated that being good care givers of their children and the extended family defined their womanhood. The wife’s role included being a nurturer to the children she bore as well as other children fathered by the husband, or his relatives. The women explained how this role is important among the Shona and they explained their resilience in the face of the intimate partner violence as follows:

My in-laws have high expectations of me as their first daughter-in-law in the family. They expect me to look after all my husband’s seven siblings in their times of need.

My three sons keep me sane in my marriage and I will not leave them.

My in-laws initially rejected me and influenced my husband to abandon me. However, one of my sisters-in-law intervened and helped to restore my relationship. I later learnt that the in-laws preferred my husband’s ex-girlfriend who had borne a son who was named after my deceased father-in-law.

As a mother I have to look after my children’s financial, emotional, spiritual and social needs. I can say they have an absentee father, although he is around. The children look up to me and I cannot let them down by walking away from this marriage.

The discourse on fecundity and the ability to provide heirs is viewed as making the woman worthy of the family she married into. With regard to this, the participants said:

My in-laws were quite disappointed in me as a wife for their son and relatives when I failed to produce any children during my marriage. They viewed me as a failure and a waste of resources they had paid in the form of lobola.

You know it is sad that society blames the woman, no wonder women may seek outside help when they realise the husband is impotent. The pressure on the woman is just too much.

My girls, who are a source of joy to me, are like a bane to my husband. He wants sons. How can we have sons if he spends his time outside the marital home with other women?

The woman’s reproductive gender role of bearing and rearing children is characteristic of Shona communities. These findings are corroborated by Kambarami (Citation2006, p. 3) positing that, “Shona women are socialized to be obedient and submissive housekeepers”. To add on, the gendered social structures and the environment in which IPV takes place need to be interrogated holistically. From this study it shows that there is need to understand the culture and socio-economic status of the partners as patriarchal privilege allows a man to engage in extra marital affairs. The findings from the study reveal that three of the men were involved in extra marital relationships and this could be a contributor to IPV. In addition to being wives, the women in this study have a further burden of being in a profession. Her job is viewed as a hobby but her actual trademark as a woman is a wife who works hard to look after the family and community. The women argued that:

I am irked that when I come from work and go to pay my condolences at a funeral wake, the ladies who would have been there during the day expect a lot from me. They expect me to do the dishes because I did not cook … to sing hymns.

Yes, funeral wakes are a contested area. If you do not participate you are labelled. So I just attend and stay late into the night then I slip away to rest and leave very early in the morning to get ready for work.

The qualitative data also reveals that patriarchal orientations may continue to be perpetuated unduly against women and are mediated by gendered social structures. The women reiterated that as part of their reproductive gender roles they cook and look after the husband even if they do have household help:

When I get home from work I must start to prepare supper for my family. My husband refuses to eat food that has been prepared by the house help. He is so traditional and does not care that I am tired.

He expects that from his wife. He has seen his mother do it all his life and if you complain, he wonders what the fuss is all about. After all, you agreed to be his wife and that means looking after him and not delegating to another woman.

6.3. Women as sexual beings

The metaphors they used to describe their positioning spoke of a position whereby their sexuality was controlled and confined by cultural expectations. Implicit in the discussions on their role as sexual partners was the idea that they had been commoditized through the payment of lobola. The metaphor of a cactus, an eagle and a stone spoke of a dormant being which is endowed with resilience and patience to deconstruct intimate partner violence.

Two of the women were able to leave and walk away from abusive and violent intimate relationships. In addition, Kuziva alludes that others walk on her behalf, inferring to the legislative measures that have been put in place through the Domestic Violence Act (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2007). The social mechanism of the aunts and uncles also acts on her behalf and she is hopeful and aware that she will walk. The implication is that the women reassert their influence in various ways to fight gender oppression. This includes finding refuge in each other as exemplified in the study, where the women educators interrogate a subject that is not often discussed publicly. By implication, it becomes imperative to understand intimate partner violence in a cultural context with cultural practices such as lobola which can encode differentiated cultural meanings on IPV. When the issue of intimate partner is interrogated from this angle, it becomes clear that it may be difficult to dismantle an entrenched practice among patriarchy but the feminists and gender advocates can still educate women and men on the effects of intimate partner violence in a community which values lobola. The findings by Mukamana et al. (Citation2020) suggest that there is need to adopt an integrated policy approach to address the increase in physical and emotional violence against women in Zimbabwe. This avenue of argument however, does not imply that the fact that they actively participated in this interrogation of the phenomenon of IPV will then by implication, minimize the GBV. The thrust has been to raise their awareness and their critical thinking and identify steps that can be taken to minimize incidents of intimate partner violence.

6.4. Women as appendages in relationships

The portrayals of the women as appendages of men in the relationships are depicted in the following statements:

It is a norm that men are the bread winners and women are the followers but of late it is the opposite. As women we are taking on the role of the breadwinner more and more, even in a marriage set up.

Ah, they think that strips them of their manhood if they lose control of the finances.

What about womanhood that is stripped by some of their actions?

In the portrayal above the participants refer to the way in which the roles are shifting. Fulu and Miedema (Citation2015) explain how the globalized trends are changing social structures, relationships and experiences. Traditionally, men believe more power should be vested in them in any relationship than in their partners (Russo & Pirlott, Citation2006) and this resonates with the way the men are portrayed in the excerpts. These men who perceive themselves as not powerful may seek to redress this through physical dominance (Dutton, Citation2012). The men would like to be in a position where they control the wealth and decision making even if the woman earns more than they do and some men may resort to violence against their partner (Mukamana et al., Citation2020). If a woman is more educated than an intimate partner, this can contribute to GBV (Chan, Citation2009; Garcia-Moreno et al., Citation2005). From an African feminist perspective, the oppressive traditions and norms which subject women as appendages in a relationship need to be dismantled. In addition, eliminating laws which sustain gender inequality as a way to combat intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe (Fidan & Bui, Citation2016) is an avenue to explore. However, African feminists still respect culture in a modified form which adopts international human rights which emancipate and allow women to function fully without treading on forbidden spaces (Nkealah, Citation2006). This resonates with the participants’ understanding of intimate partner violence and what they experienced in their intimate relationships.

7. Conclusion

The study demonstrates that IPV against women in Zimbabwe has continued to be prevalent despite several studies on the phenomena. It is argued that participatory visual methodology is appropriate to interrogate the lived realities of women and the complexities of gendered social structures. The assumption is that participatory engagement of the marginalized groups of society means that those who are affected the most takes the lead in bringing about social change. The thrust has been to raise their awareness and their critical thinking and identify steps that can be taken to minimize incidents of intimate partner violence. This not only opens up democratic spaces for the participants but also demonstrates how research can be used as intervention. It was observed that IPV against women is mediated by tradition and norms which shape and change practices in intimate partner relationships. The oppressive traditions and norms which portray women as appendages in a relationship need to be minimized. Laws which sustain gender inequality have to be eliminated as a way to combat intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe. By extension, dismantling entrenched patriarchal practices through educating women and men on the effects of intimate partner violence can change the cultural meanings of IPV. This can also help to combat intimate partner violence. The study reveals that the women’s resilience is reframed within the localized context of gender socialization where a “good wife” and a “good mother” endure GBV in the private space. The study further demonstrates how women can fight gender oppression in various ways such as sharing ideas. The drawings the participants shared facilitated knowledge production, which was empowering for the participants. In other words the women help one another to negotiate the gender terrain as depicted in the discussions on the drawings which elicited a number of responses. The participants viewed themselves as sexual beings, appendages of men as well as having an inherent power within them which enables them to survive IPV. The study also shows that there is need to understand the cultural practices which encode differentiated cultural meanings of intimate partner relationships and intimate partner violence. The study thus argues that IPV can be minimized by adopting a holistic approach which is empowering and liberating to the women and provides education which reorients the mindset of both the women and men. However, a change in mindset on both the women and men takes time as their awareness and critical thinking is deepened.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nogget Matope

Nogget Matope has widely published research papers on gender- based violence in the realm of women’s lived realities in urban and rural spaces in Zimbabwe. Mathabo Khau is an accomplished researcher who has published research articles on sexuality and gender- based violence in the South African context. The article is part of Nogget Matope’s PhD thesis and Mathabo Khau was the promoter who steered the research.

References

- Abbi, K., & Lul, A. (2010). Violence against women in Ethiopia. Gender, Place and Culture, 17(4), 437–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x2010.485832 [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams, N., Matthews, S., Jewkes, R., Martin, L., & Lombard, C. (2012). Policy brief: Every eight hours: Intimate femicide in South Africa 10 years later. Medical Research Council. https://www.safespaces.org.za [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Gyamfi, E. (2014). Legal remedies against abuse of women and children: The case of Ghana. International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies, 2 (1), 61–81. https://ijgws.com [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M., & Devitt, C. (2012). Intimate partner violence and belief systems in Liberia. Sage Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27 (17), 3514–3531. https://journals.sagepub.com [Google Scolar]

- Attteraya, M. S., Gnawali, S., & Song, I. H. (2014). Factors associated with intimate partner violence against married women in Nepal. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(7). SAGE. https://journals.sagepub.com SAGE

- Ayedapo, A. O., Sokoni, O. O., & Asuzu, M. C. (2017). Pattern of intimate partner violence disclosure among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Oyo east local Government, Nigeria. South Africa Family Practice, 59(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.1272245 [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J. (2010). ‘Circles and circles’: Notes on African feminist debates around gender and violence. Feminist Africa 14: Rethinking Gender and Violence, 14(14), 21–47. African Gender Institute. http://hd.handle.net/11427/22018

- Bhattacharya, H. (2009). Introduction to gender violence and identity. Qualitative Inquiry, 15(2), 267–275. SAGE Publications. https://journals.sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Burrill, E., Roberts, R., & Thornberry, E. (2010). Domestic violence and the law in colonial and post-colonial Africa. Ohio University Press. https://ohioswallow.com [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. L. (2009). Sexual violence against women and children in Chinese societies. Trauma and Violence Abuse, 10(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838008327260

- Chuma, M., & Chazovachii, B. (2012). Domestic violence act: Opportunities and challenges for women in rural areas: The case of ward 3, Mwenezi District, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Politics and Good Governance, 3(3), 1–18. https://journals.sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Country Policy and Information Note: Zimbabwe women fearing gender based harm or violence 2018

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, B., & Andipatin, M. (2016). Abused woman’s understanding of intimate partner violence and the link to intimate femicide. Forum Qualitative, 17 (1), 1–30. http://nbn-resolving.de/umi-nbn-de.014-fgs.160196 [Google Scholar]

- Duramy Faedi, B. (2014). Gender and violence in Haiti, women’s path from victim to agents. Rutgers University Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-016-9320-1 [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, D. G. (2012). The case against the role of gender in intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior: A Review Journal, 17(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.002 [Google Scholar]

- Fidan, A., & Bui, H. N. (2016). Intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe. Violence against Women, 22 (9), 1075–1096. https://journals.sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Fite, M. D. (2014). The Ethiopia’s legal framework on domestic violence against women: A critical perspective. International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies, 2 (1), 49–60. http://ijws.com [Google Scholar]

- Fulu, E., Warner, X., Miedema, S., Jewkes, R., & Roselli, T. (2013). Why do some men use violence against women and how can we prevent it UN Multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and Pacific. Global Health Journal. [Google Scholar].

- Fulu, E., & Miedema, S. (2015). Violence against women: Globalizing the integrated ecological model, Violence against Women, 21(12), 1431–1455. https://journals.sagepub.com [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Moreno, C., Heise, L., Jansen, H. A., Ellsberg, M., & Watts, C. (2005). Public health. Violence against women. Science, 310 (5752), 1282–1283. [PubMed]. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1121400

- Government of Zimbabwe. (2007). The domestic violence act. Chapter, Vol. 5 16. Government Printers. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln. Eds., Handbook of qualitative research 105–117. Sage Publications. https://sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Heise-Biber, S. N. Ed. (2014). Feminist research practice: A primer 2nded. SAGE Thousand Oaks. https://sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Kambarami, M. (2006). Femininity and culture: Patriarchy and female subordination in Zimbabwe. Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Centre [Google Scholar].

- Lasong, J., Zhang, Y., Muyayalo, K. P., Njiri, O. A., Gebremedhin, S. A., Abaidoo, C. S., Liu, C. A., Zhang, H., & Zhao, K. (2020). Domestic violence among women of reproductive age in Zimbabwe: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 354. Google Scholar. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8447-9

- Machisa, M., Jewkes, H., Lowe-Morna, C., & Rama, K. (2011). The war at home: Gender-based violence indicators project. Gauteng Research Report. Medical Research Council and Gender links. https://doi.org/10.100/10402659.2022.204900 [Google Scholar]

- Madriz, E. (2000). Focus groups in feminist research. N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln. Eds., Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd 835–850. Thousand Oaks CA. SAGE. https://sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. (2001). The art of science clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. The Lancet, 358(9279), 397–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9

- Mama, A. (2004). Demythologizing gender in development: Feminist studies in African contexts. IDS Bulletin, 35(4), 121–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1529-212620210000031001 [Google Scholar]

- Merry, S. E. (2013). Law, culture and cultural appropriation. Yale Journal of the Law and Humanities, 10(2), 5–8. [Google Scholar]. https://digitalcommons.lawyale.edu/yjlh/vol10/iss2/16

- Mitchell, C. (2011). Doing visual research. SAGE. https://sagepub.com [Google Scholar]

- Moletsane, R. C., Mitchell, N., de Lange, N., Stuart, J., Buthelezi, T., & Taylor, M. (2009). What can a woman do with a camera? Turning the female gaze on poverty and HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education Taylor and Francis, 22(3), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390902835454 [Google Scholar]

- Mukamana, J. I., Machakanja, N., & Adjei, K. (2020). Trends in prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe 2005-2015. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 20(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s1294-019-0220-8 [Google Scholar]

- Musingafi, C., & Tom, T. (2013). Domestic violence in urban areas in Zimbabwe. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3 (3). [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, S. (2014). Violence, protest and change: A socio-legal analysis of extraordinary mobilization after the 2012 Delhi gang rape case. International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies, 2 (2), 197–221. [Google Scholar]

- Nkealah, N. (2006). Conceptualizing feminisms in Africa: The challenges facing African women writers and critics. English Academy Review, 23(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10131750608540431 [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, J., Beckman, T., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 80(9).

- Protocol to the African charter on human and people’s rights on the rights of women in Africa. Adopted by 2nd ordinary session of assembly of the union, 11 July 2003 [ Google Scholar]

- Russo, N. F., & Pirlott, A. (2006). Gender-based violence: Concepts, methods and findings. New York Academy of Sciences, 1087 (1), 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1385.024 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaw, J. (2017). Pathways to accountability from the margins: Reflections on participatory practice. Making all voices count Research Report. IDS. [Google Scholar]

- Sitaker, M. (2008). The ecology of intimate partner violence: Theorized impacts on women’s use of violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 15(3–4), 179–219. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/1092677802097335 [Google Scholar]

- Sithole, I. (2007). Demanding implementation, challenging obstacles. Pambazuka News, (330). http://www.pambazuka.org/en/category/comment/44709 [Google Scholar]

- Sweetnam, S. (2013). Where do you think domestic abuse hurts most? Violence Against Women, 19(1), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212475340 [Google Scholar]

- Tamale, S. (2011). African sexualities: A reader. Pambazuka Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. P., & Medina, M. N. D. (2013). Educational research paradigms: From positivism to multipragmatic. Journal of Meaning Centred Education, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3542.0905 [Google Scholar]

- Temmerman, M. (2015). Research priorities ti address violence against women and girls. The Lancet.

- L. Theron, C. Mitchell, A. Smith, and J. E. Stuart (Eds.). (2011). Picturing research design: Drawing as a visual methodology. Rotterdam. Sense Publishers.

- UN. (1993). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. Retrieved April 18, 2015, from http://www.un./org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S. (2005). Gender mainstreaming: Productive tensions in theory and practice. Social Politics International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 12(3), 321–343.

- Watson, J. (2015). Engaging with the state: Lessons learnt from social advocacy on gender-based violence. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 28(2), 58–66.

- Wekwete, N. N., Sanhokwe, H., Murenjekwa, W., Takavarasha, F., & Madzingira, N. (2014). DHS working paper no 108 (Zimbabwe working paper no. 9). ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2001). Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Department of Gender and Women’s Health. [Google Scholar]