Abstract

One of the nineteenth century’s leading sociologists, Auguste Comte (1798–1857) argued that all political communities—irrespective of geography, race, or ideological inclinations—in their efforts to make sense of the world, pass through similar developmental and evolutionary stages: the religious stage is usually the first, and is followed by the metaphysical stage and later ends in the scientific stage. Weaving from Comte’s paradigms, this paper aims to demonstrate the utility of the interactions among the three study areas of science, religion and culture and the influence that each one of them yields over the others in polity governance. Most significantly, their reciprocal relationship is emphasized. However, one of the pathologies surrounding the study of these three topics is the controversy that they generate among scholars: some researchers argue that science is a stand-alone concept, which should be delinked from the other two knowledge-seeking endeavors. The ground for their argument is that unlike religion and culture, scientific premises are—in principle—falsifiable. Other scholars argue to the contrary: that there is, in fact, a close connection among the three study areas, which helps to sustain human life. In bridging these research trajectories, this paper argues in favor of the latter argument, which acknowledges the reciprocal roles that each one of these endeavors play in enhancing the others. This position is also in synchronicity with Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s standpoint that the ontology of human nature is best understood from the prism of integration, adaptation, and cooperation rather than from competition and contestation. Although the comparative analysis of the three study areas reveals both the homogeneities and contrasts among them, the study concludes that science, enriched with philosophical underpinnings from culture and religion offers the best radar for optimal social development. In discussing the issues articulated, this paper adopts a mixed method of enquiry consisting of both the quantitative and qualitative methods. The paper also draws on secondary methods of enquiry through academic journals, scholarly books, and online publications.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study examines how science, culture, and religion influence each other in shaping societal dispositions. To achieve this, the study takes a transdisciplinary approach, which disbands the boundaries between these conventional disciplines and attempt to (re)construct their meaning in the context of real-life enigmas. On the one hand, science lends its utility from pragmatic and experimental approaches that may employ a variety of empirical methods and technological approaches such as computational methods, data archiving and artificial intelligence: this is how science interprets world phenomenon. On the other hand, the ontology of culture and religion spins on hermeneutics, rhetorical, and historical approaches as guides in the interpretation of world occurrences: the philosophy of culture and religion assumes that epistemology is incomplete if it ignores history.

While this cultural and religious epistemological underpinning cannot be dismissed as idle speculation, societies must be wary of the snares of blanket reliance on history as an unchanging database for evaluating societal premises and insights. Similarly, scientific novelties must equally be scrutinized as some of them do not lend themselves to ethical designs. The overall context of this study’s argument is that due to the contingency nature of life situations, it is imperative to pay attention to when and how the meanings of some of the key societal notions are undergoing transformation.

1. Introduction

This paper aims to make a reciprocal connection and appreciation of the study areas of science, culture, and religion. The research question that the paper sought to answer is: how does science, culture and religion interact and influence each other? To appreciate their interplay and interface, the paper provides a brief description or definition of each one of them. This way, the nuances and premise upon which their influences are built will be grasped more fully. Most significantly, due to their distinctiveness, they also operate as forms of 'checks and balances' on each other—thereby building upon each other. In deliberating these research configurations, certain passages in this paper will use religion and culture interchangeably due to their close relationship in their practical application in society.

1.1. What is science?

Science may be defined as a systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through objective observation, experiment, verification, and falsification processes. Science is an enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable and reliable explanations and predictions about the universe (Rosenberg, Citation2005). Science may also be defined as a branch of knowledge dealing with a body of facts that are systematically arranged and showing operation of general laws. Science encourages truth and understanding of events by exposing its processes to scrutiny and peer review assessment. Science is a result of revolutionary interaction—revolutions challenge the status quo and expand levels of human imagination.

Science also develops cumulatively and incrementally. This ultimately injects a mindset of critical thinking in its processes. In science, truth is something that can be tested and proved (ibid). According to William Whewell, a scientist is any practitioner of diverse natural philosophies (Whewell, Citation1834).

1.2. What is culture?

The concept of culture and values are complex with no clear ideological consensus among scholars. The United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organization (Citation1945) defines culture as a 'set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of a society, which encompasses value systems, tradition customs and beliefs in the areas such as in the arts, literature, lifestyles, and ways of living together.'

According to Woodhead (Citation2011), culture can be defined as the characteristics of a group of people described by a common language, common bonds, common beliefs, family ties, religion, shared life, and social habits. Culture may also be defined as a set of ideas, rules, arts, customs, laws, customary beliefs, and norms including material objects commonly practiced by a group of people that can be used to define them as a collective. Culture can also be seen as a symbol of group identity, monuments, style of dress, flags, and distinctive foods and a general agreement on what the collective considers to be societal values. Expanding on these categories, culture is made up of common sense, assumptions, and certain expectations. Here, truth is something that emanates from normative assumptions and moral judgements (Prinz, Citation2012).

1.3. What is religion?

Scholars offer varied definitions. Religion may be defined as a social-cultural system of designated behaviors, practices, morals, beliefs, prophesies, ethics, and world views that relates humanity to the supernatural and spirit rudiments. Idinopulos (Citation1998) would define religion as a unified system and practices of worship, faith, sacred ceremonies, a belief in God as the supreme supernatural being. Religion may also be defined as a social system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, world views, ethics, prophesies, and institutions that relate humanity to supernatural elements. Other scholars could define religion an organized collection of beliefs, cultural systems and world views that relate humanity to an order of existence. Religions have narratives, symbols and sacred histories that are intended to explain the meaning of life or the origin of life. Religions are comprised of a set of feelings, dogmas and practices that define the relations between the human being and the holy, the sacred, the spiritual and the divine. Under religion, truth is derived from beliefs of the supernatural and divine elements (Hammer, Citation2019).

Religion as a cultural system comprises myths, rituals, and beliefs as a way of creating a sense of meaning in the lives of human beings. Woodhead (Citation2011) argued that although faith is linked to belief in unseen realities, people have always wanted to see the sacred. As such, rituals work as tangible symbols of the intangible realm. Rituals not only denote spiritual truths but also outline how power is comprehended in the material world. Sacred stories of important historical events also form part of the religious belief system.

2. Methodology

This study aimed at assessing the interplay of science, culture, and religion in advancing the human knowledge. The research question that the paper sought to answer is: how does science, culture and religion interact and influence each other? The research, therefore, lies within the realm of these three specific relationships. The instruments used for empirical data collection were both quantitative and qualitative methods.

Quantitative methods were employed to justify the use of statistical information. However, more data were collected from qualitative methods, such as through the following: (a) from the landmark court rulings of the Dutch Supreme Court, and the Hague District Court (b) from a report from the United Nations (UN) climate summit, the UN Economic Commission for Africa, (c) from speeches and excerpts from men of letters and prominent personalities. Other forms of information that supported the evidence in the study were gathered from secondary sources such as from academic journals, scholarly books, and online publications. This mixed method approach of data collection was employed for the purpose of cross-checking information to ensure that data collected were harmonized (Crewell, Citation1990).

3. Conceptual issues—science, culture and religion

Throughout history, the relationship of science, culture and religion has always offered a mixed bag of reactions and competition because all of them keep evolving and are divergent across cultures. Science and religion emerged to prominence at different times (Draper, Citation1874). Religion emerged to greater heights in the 1600s, while science became more prominent in the 1800s. One of the ways in which science can be distinguished from religion stems from the claim that science concerns only the natural world, while religion encompasses both the natural world and the supernatural. More specifically, scientific theories do not lend themselves to supernatural entities such as gods, angels, karma, miracles, magic, and witchcraft. Their differing assumptions have been twofold; whereby on the one hand, we have conflicting assumptions, and on the other hand, the harmonizing assumptions. A major point of observation is that prior to the scientific revolution, scientific inventions were conducted by communities under religious traditions (White, Citation2009).

Scholars such as Karl Popper see the relationship between science, culture and religion as different entities attempting to address different things (Rees, Citation2017). Also, scientific language and religious language are at variance. Scholars in the category of Popper argue that religion and culture are corrosive to science and vice-versa and as such, each should stay in its own domain (Popper, Citation1959). It is argued that the historical pedigree of religion and culture is notorious for nurturing orthodox conceptions of lifestyles, which result in the (re)production of distorted images and identities of individual talent and acumen in the polity development discourse. Ethologist Richard Dawkins posits that science need not accommodate religious and cultural beliefs because religion degrades the scientific enterprise by weakening and undermining the intellect. Further, the rigid disposition of religious norms tends to make the converted followers susceptible to chauvinist effusions that often lead to radicalization and religious fanaticism, which otherwise could be described as the blind devotion to a particular cause (Dawkins, Citation2002).

Religious fanaticism and extremism have often high ability to use applied science and are not confined to a particular religion or culture. The misleading postulation that assumes, for instance, that religious fanaticism is necessarily linked to violence or terrorism, is a narrow conception which overlooks the wider sphere within which radicalism, extremism and fanaticism is situated. For instance, the Christian fanfare regularly exhibited by some Pentecostal evangelists where they organize so-called 'healing rallies' and 'healing conferences' where they supposedly perform 'prosperity and healing miracles', and where some attendees 'speak in tongues', and others falling to the ground upon being touched or anointed by the evangelist, is—from a prism of a scientist—a form of religious fanaticism. In Pakistan, for instance, honor killings, otherwise the cold-blooded murders, often of women for alleged violations of conservative norms that administer (marital) relationships have continued despite the 2016 Pakistan national legislation that prescribes stiff prison sentences for such killings. From a perspective of science, such cultural practices would be classified as acts of cultural fanaticism (The Guardian, 24 May Citation2022). To appreciate further the expanded scope of religious and cultural fanaticism, another example involving an Islamic organization, the Muslim Brotherhood, will be used: internationally, the movement is perceived to be a radical and extremist organization with violence-predisposed religious blueprints. The West, in particular, argue that the groups’ maneuvers and its mobilization strategy—to all intents and purposes—point to an organization that positions itself as a fertile incubator of terrorist activities. To the contrary, within their local jurisdictions, the Muslim Brotherhood is generally viewed in a positive light as an organisation that promotes charity works, community welfare ventures, and disseminates Islamic values of social justice (Vannetzel, Citation2017).

An analysis of the educational background of key figures within the ranks of the Muslim Brotherhood suggest that majority of them have attained high qualifications such as in the natural science fields of biology, engineering, technology, and earth science. Several other officials hold degrees in the social and human sciences. Paradoxically, only a handful within their leadership ranks have qualifications in religious studies (Vannetzel, Citation2017). The question that one might ask is: how does a person who is skilled in the analysis of empirical data turn out to be a religious fundamentalist? On face value, one would be inclined to assume that the efficacy of science itself would eliminate fanatical views. However, two of the following analyses might provide answers to this paradox:

The absence of societal freedoms: Polities that promote freedom in their communities also intrinsically expand the horizons of critical thinking, and hence diminish rigid and orthodox thinking. In restrictive societies, science may be exploited and utilised as a tool that validates absolute and inflexible religious attitudes. More bizarrely, rigid societies also tend to impose their dogmatic beliefs on other people; believing in simplistic notions that people are either with them, or against them, i.e., the tendency to view scenerios only in black and white versions.

Religious entities provide incentives, prestige, and privileges to elite members: Due to the inherent linear thinking, religious institutions prefer to attract the scientific elite to propel the religious agenda. This is because science yields enormous influence in society. This influence means that scientific knowledge pauses tremendous threat to religious authority, hence the calculated moves to entice scientific scholars. This might explain why, for instance, the Muslim Brotherhood relied on the elite science scholars as leaders. With scientists on board, the religious project gains significant traction. It can be argued, however, that the practical or real scientific contributions of these science scholars to the wider (global) scientific family remains negligible. This shows that the scientific elites in extremist organisations may only serve as superficial garments that provide effervescence to organizations that are engrossed in ideological positivism (Vannetzel, Citation2017).

Dawkins (Citation2002) points out that given that culture and religion makes claims of the supernatural—claims which science refutes—the incompatibility could not be clearer, and further opines that:

… culture and religion teach people to believe in trivial, supernatural non-explanations that we have within our grasp. Religion teaches people to obey authority, revelation, and faith instead of insisting on evidence …

Karl Popper would further argue that philosophers of science must delineate science from other knowledge-seeking endeavors such as religion because unlike religion and culture, the utility of scientific theories depends largely on their ability to be falsified (Popper, Citation1959). Neurologists (scientists), for instance, normally explain human thoughts in terms of the state of the brain, instead of referring to the soul or to the spirit, which is what religion and culture does. Put simply, science helps to identify causal mechanisms of phenomenon that are both verifiable and falsifiable (Forrest, Citation2000).

The melting point of this incompatibility argument can be traced back to the days of Nicolas Copernicus and Galileo who found themselves at loggerheads with the powerful catholic church at the time for advocating heliocentrism—a scientific concept that argued that the sun, not the earth, was at the center of the universe (White, Citation2009). The Pope denounced this conception arguing that it contradicted the teachings of the church; in those days, the architecture, muzzle, and influence of the Catholic Church on polity affairs papered over the cracks. It is contended that the major difference between science, culture and religion is that in science, explanations are expected to be evidence-based. Scientific experiments that disagree with an explanation must either be amended or may require that the explanation altogether be ended. In religion and culture, on the other hand, teachings do not rely on empirical evidence and cannot be modified in the face of conflicting evidence because they lean on divine and supernatural powers. As White (Citation2009) has contended, given that divine matters are not part of nature, it is, therefore, not possible for science to investigate them. In this connection, it can be contended that science and religion are separate since they address crucial aspects of human grasp in different, if not entirely in opposing ways. Thomas Kuhn opined that people in different paradigms cannot speak the same language and even where communication is possible, scientists, on their part, will use a different standard of evidence and argument evaluation (Kuhn, Citation2012).

3.1. The differing perspectives within the scientific body—Positivism, Logical Positivism, Post-Positivism, and Marxism

Scientific perspectives themselves have taken opposing views: for instance, positivism which came to prominence in the nineteenth century was championed by Auguste Comte, and later refined by Emile Durkheim, stressed that empiricism and objectivity were crucial anchors in knowledge formation. The positivist standpoint was that knowledge is derived from sensory information relying on the scientist as an objective medium. In addition, positivism regarded the natural sciences as the only real sciences; in this context, the social sciences fell outside that framework on the understanding that social sciences derive their knowledge from subjective experiences of people. Put simply, the knowledge obtained from societal attitudes could not have an objective basis (Moses & Knutsen, Citation2007).

By the early twentieth century, logical positivism emerged and challenged the idealist knitting of positivism and took an anti-idealist stance towards science. Among those who propelled logical positivism was Moritz Schlick, a leading figure of an influential scientific grouping at the time, the Vienna Circle. The main point of departure was that whereas Comte’s positivism saw a transitional connection from religion, metaphysics, and science, logical positivism did not recognise that connection, hence rejected a core underpinning of positivism. Logical positivism’s central argument was that single observations (which were acceptable under positivism) are not enough and cannot always be relied upon as they are prone to subjectivity. Instead, logical positivism proposed verification and triangulation as the alternative method of scientific enquiry (Moses & Knutsen, Citation2007).

However, towards the 1930s, post-positivism philosophers such as D.C. Phillip and Karl Popper emerged and challenged logical positivism almost entirely. In the ensuing years, Popper remained the dominant figure of the post-positivist agenda whose main point of disapproval of logical positivism was that scientific knowledge is always provisional; that in experiments, verification is not a sufficient means to disprove a supposition; and that no number of positive outcomes could confirm a theory, yet a single refutation is logically decisive. For Popper, scientists are never objective because observation is 'theory-laden' —the world appears to us in the context of theories we already hold.

The two pictures below help to illustrate Popper’s argument in the context of the intrigues of a human mind and its susceptibility to subjective views. In the first picture, one supposition might hold the view that a Zebra is white with black stripes, yet another opposing belief could suggest that a Zebra is in fact black with white stripes (.

With reference to the second picture, one line of thought might posit that the image shown is a tumbler, yet an alternative viewpoint could argue to the contrary and suggest that in fact the image represents two people looking at each other at close range.

Post-positivism takes a social constructivist perspective that contends that not everything is completely knowable. This position sits germane with the views of former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s political allegory, unknown unknowns which he expounded at the height of the 2003 Iraq war saga. In his allegory, the point that Rumsfeld was driving was that 'there are many things (or hidden activities) of which we are so unaware that we do not even know that we are unaware of them' (Rumsfeld, Citation2011).

Coming to the emergence of post-positivism, Popper replaced the positivist classical 'inductivist disposition' with the theory of falsification as an alternative and solid method of scientific enquiry, arguing that this technique demarcated science from non-science. Popper’s key philosophical contribution was the proposition that progressive science must endeavour to disprove a theory rather than seek solace in attempts that continuously support the prevailing theoretical hypotheses. The notable scientists that followed Popper’s work and who have furthered his insights are Imre Lakatos and Paul Feyerabend. Thomas Kuhn’s thought of the paradigm shifts in science further neutralised the theoretical pillars of logical positivism (Kuhn, Citation2012).

So, by the beginning of the second half of the twentieth century, positivism had waned, and took a moderate position, which was named as, logical empiricism, championed by logician Carl Hempel. To remain relevant, Hempel preferred to adopt the phrase, 'logical empiricism' as opposed to maintaining 'logical positivism' because the latter carried undertones of metaphysical propositions whose hypotheses are not capable of confirming or disconfirming the evidence presented (Popper, Citation1959).

The innovative conception of these old debates, particularly those of Comte and Popper, has provided seminal scientific foundations upon which contemporary scientists and philosophers are drawing and building broader scientific constellations.

Scientific inquiry thrives mainly in polities that foster the free flow of ideas and information: culture and religion—due to their dogmatic disposition—rarely provide environments for the free flow of ideas and innovation. Crucially for the global south, and Africa in particular, the dynamics of the twenty-first-century ideas of development depend on the intellectual, free, and open discussion of recurrent developmental challenges of governance, industrialization, education, and technology. From this analysis, it can be deduced that today, majority of countries that are thriving are those that promote free-thinking and are forward-looking (Vorvornator, Citation2022).

Sociologists such as Durkheim argued that religious beliefs are only intended to serve the purpose of creating a harmonious societal environment to keep communities together. Like Durkheim, critical theorists such as Max Weber and Karl Marx held the view that religion would decline in the face of the growth of science and technology (Rees, Citation2017). It is also not a coincidence that most poverty-stricken polities tend to be more religious than affluent societies—many poor people hold fallacy religious views that their economic doldrums would improve with divine or supernatural intervention. As Karl Marx put it, 'religion is the opium of the people'. Marx’s contextual 'opium' metaphor is very instructive: it challenges the population to put a premium on practical and sustainable economic models that have the capacity to alleviate poverty rather than focus on religious convictions as solutions (Pedersen, Citation2015).

So, how does Marxism relate to this study topic? The utility of the Marxist theory here is that it infuses a critical theory perspective in its influences that helps to guide our understanding of the disposition of economic relations and its residual effects of class conflict. Marxism blends with critical theory ideas of the Frankfurt School scholars such as Jurgen Habermas and Max Weber whose aim is to unravel conditions for social change. In doing so, Marxism unmasks the obscured misconceptions of some societal ideologies and assumptions that keep the population from truly understanding how the economic systems work against them, in a counterfeit fashion. Marx puts this economic debate in perspective when he argues that:

… as participants in a capitalist market economy, we fall into thinking of the economy in terms of private property rights, free exchange, the laws of supply and demand, etc. … and in doing so, we fall into thinking of capitalist economic social relations as justified, as how things should be. This way of thinking is nothing but an ideology: it obscures, even from those people who suffer them, the pervasive and destructive forms of alienation, powerlessness and exploitation that define capitalism’s economic relations. Any prospects for change, reform or revolution requires first that people come to see capitalism for what it is; for they must first see the ways in which they themselves are alienated, powerless and exploited before they can try to free themselves from it (Koltonski, Citation2014).

These Marxist revelations are critical to societal emancipation because they further expose the fact that knowledge levels at global level are biased and compromised. For instance, world philosophy and science are dominated by Western scholarship as if the global south did not have reservoirs of rich scientific and philosophical conceptions. It is certain that not every one agrees that the West is the only place in the world that produced scientific and philosophical knowledge. To be sure, the global south has always had prowess in scientific ventures, but their skills have been subdued for centuries at the hands of imperial and colonial powers (Simuziya, Citation2021). Specifically, on Africa, the African question in science and philosophy remains mysterious because of the intentional effort by the colonial project to rationalize Africans out of humanity. Eurocentric scholars maimed African history and invented a false image of an African which they presented as the substantive African identity. Famous Western scholars such as G.W. Hegel, David Hume and Charles de Montesquieu gave weight to the idea that Africans are inferior compared to Western races (Uduma, Citation2014). A more apt description of this exploitation and marginalization of African scholarship is laid bare when Uduma (Citation2014) argues that:

… the colonialists concocted an image and identity of Africans that present them as pre-logical, barbaric, and as such, incapable of having philosophical thoughts. This identity was foisted and consolidated on humanity including on Africans themselves, and intellectually accepted as the true African identity for over four centuries. Consequently, while the racist Eurocentric description of the African makes it impossible for one to suggest that there can be anything like African science and philosophy, the enslavement, balkanization, colonialization, and the introduction of a Western-oriented form of education into Africa further dehumanized, traumatized, and alienated Africans from their culture. This experience is what precipitated the identity problem in Africa.

From the African continent, the civilization of ancient Egypt is evidence that the continent possessed unique aptitude of scientific and philosophical workings. These include the traditional African medicines and healing plants whose compositions today are clandestinely syphoned to the West without providing sufficient acknowledgement that these medicinal plants are in fact indigenously African (Simuziya, Citation2021).

From Asia, the ancient teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius have had profound influence on the development of the Chinese people. So, both the Asian and African examples bear witness to the fact that scientific and philosophical knowledge is not a preserve of the West. Also, the fact that the West itself occasionally—reluctantly though—refers to ancient Egypt and to the Confucius studies as sources of knowledge confirms that tanks of scientific knowledge from the global south have long provided valuable human knowledge beyond their continental borders (Taam, Citation1953).

Coming to religion, Kenyan law professor Patrick Lumumba is in synchroneity with the view that religious dogmas pose a potential detrimental effect on the economic growth prospects of Africa when he argues that 'Africans are notoriously religious' believing that prayers will bring economic revival. Professor Lumumba observes that this simplistic understanding, and over-the-top dramatization of religious scripts is fundamentally flawed and only works to perpetuate poverty in (African) societies: many religious Africans have tended to grasp religious doctrines out of context. Like Karl Marx, Professor Lumumba’s allegorical reference of Africans being 'notoriously religious' is equality informative as it exposes the widespread deficiency of reflective reasoning in religious circles on how economic growth can be attained (Lumumba, Citation2020).

The utility of religion in the context of economic emancipation (particularly in Africa) is further put into question when an African scholar Ousma Touray argues that:

… when we (Africans) analyze the systems that we have today … spirituality for instance, has been narrowed down to religion. Religion promises us unity, love, kindness, trustworthiness, health, and heaven (abundant life) - but are these the living reality of the religions that we belong to in Africa today? Are we (the Africans) united as a continent? Are we trustworthy as individuals? Are we patriotic as Africans, and are we ready to build (economic) growth solutions for the continent? If (harmony and abundance) is the promise of religion, do the facts on the ground across the continent reflect a living reality of those religious promises? (Touray, Citation2021).

On the other hand, however, scholars who see a silver lining in the compatibility argument (i.e., those who claim that religion and science are in harmony), have cautioned that scientific grandstanding over cultural and religious enquiries need self-moderation: they argue that all knowledge is personal and therefore the scientist must be performing a personal (and hence a subjective) mission when conducting research … scientists merely follow intuitions of ‘experimental agreement’. Further, for science to be sustained, it needs moral guidance and obligations like those found in culture and religion (Harrison, Citation2015).

Scholars in this category see a close relationship between science, religion and culture and consider this relationship to be harmonious. In general, however, most religious scholars see science as being complementary to their beliefs while at the same time acknowledging that there are conflicts on methodology. Likewise, scientists who are religious also see this compatibility (Lama, Citation2005).

Ironically, although natural philosophers such as Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton had the tendency to favor philosophy (and science), nevertheless were also keen to explore the supernatural in their (scientific) works. This revelation confirms that each one of the three topics under discussion advances the frontiers of scholarship on the ontology of polity governance (Forrest, Citation2000).

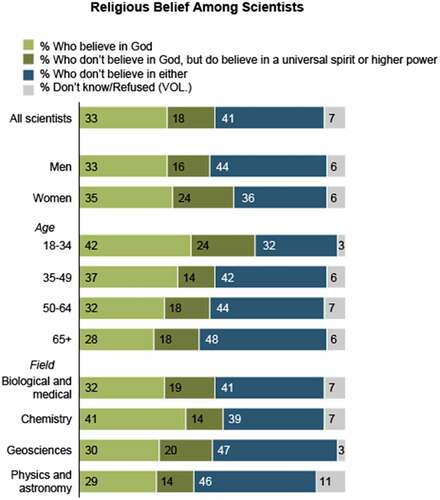

Historian, Peter Harrison argues that biblical teachings have in fact been instrumental in providing building blocks for modern science and that theological conceptions of nature and humanity helped to give rise to science; hence, there are colorations and compatibilities (Harrison, Citation2015). This position is also supported by a survey that was carried out in the USA in 2009 to find out the percentage of scientists who are religious. The survey suggests that at least 33% of scientists at the material time were religious. The diagram below )illustrates this compatibility (Pew Research Centre, Citation2009).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Excesses of science and how they are mitigated by cultural and religious underpinnings

In contemporary IR, the excesses of science can be seen in major technological innovations. Science, which is usually driven by an insatiable appetite to enhance the engineering, mechanical, technical, medical, and social efficiency of global systems is not always able to apply its innovations in ways that lend themselves to ethical designs. The pathologies of modern science are more aptly explained by Podvoyskiy (Citation2022) when he argues that:

… technology is ‘fetishized’ by the modern thinking … excessive specialization, standardization, algorithmization, routinization of activities, technological and functional operationalization of the work process and professional roles, the dominance of means over goals, administrative and bureaucratic regulation and control have become ‘signs of the time’ and distinctive features of the ‘rhythm of activity’ not only in industrial enterprises, but also in non-physical labor. An important aspect (and background circumstance) in the diagnosis of modernity is the fact that in recent centuries, modern societies have developed mainly in the urban social-ecological environment …

For instance, artificial intelligence systems such as video surveillance and biometric tracking are increasingly being used today to monitor, track, and thwart (suspected) criminal and terrorist activities. While these measures might help to improve security, they do violate the privacy of ordinary people. Most notably, these gages could potentially aid future discriminations (using stored surveillance data) based on ethnic affiliations, race, religious beliefs, and political ideologies (Cataleta & Cataleta, Citation2020).

Three of the following examples provide telling instances of these gaps in science and how the philosophical foundations embedded in culture and religion offer the necessary remedies.

On 6 February 2020, the Hague District Court ordered the Dutch government to stop the use of the SyRI, an automated system that analyses a wide range of personal and sensitive data to predict how likely people are to commit tax or benefits fraud. The court ruling affirms that individuals who need social security support should be treated as rights-holders whose privacy matters, and not suspects to be constantly surveilled. The court argued that transparency is needed to guard against such technology-enabled abuses of privacy and related rights (Human Rights Watch, Citation2020). During the hearing, the government representatives failed to provide evocative information about how SyRI uses personal data to draw inferences about such possible fraud. The court was dissatisfied that government officials had to hide how the system’s risk calculation model works. But to counter the court’s concerns, the government argued that the SyRI does not automatically trigger legal consequences or even a full investigation. But even this argument failed to dispel the courts’ concerns that the SyRI risk-scoring process itself created significant potential for abuse. Under the SyRI system, the court argued, individuals have no way of knowing or challenging their risk scores, which are stored in government databases to which they have no access. Human Rights Watch (Citation2020) points out that the court further argued that:

… without (access to) this information, it is nearly impossible for individuals under suspicion to challenge the governments’ decisions to investigate them for fraud. This lack of transparency is particularly troubling given that SyRI has been exclusively deployed in so-called ‘problem’ neighborhoods – a potential proxy for discrimination and bias based on individuals’ social-economic backgrounds and immigration status …

The court’s ruling justifies the efforts of human rights campaigners to ensure that due diligence is given to the design of automated decision-making systems. Claims by government representatives that a single data protection impact assessment that it conducted for the SyRI was enough attracted further rebuke from the court; the court argued that this on-size-fits-all assessment may have overlooked the need to conduct similar assessments for each municipal-level project that adapted SyRI to its specific fraud detection needs (Human Rights Watch, Citation2020).

By stopping SyRI, the court has drawn a line in the sand—that such technological innovations must be sensitive to moral values, ethics, and human rights, particularly the rights of the poor in the age of automation. Other governments such as the US and the UK that have relied on data analytics to regulate access to social security should heed the Dutch court’s warning about the human rights risks involved in treating social security beneficiaries as perpetual suspects.

Although artificial intelligence as a cognitive technology has the capacity to improve human lives, it also has profound penalties for societies and cultures. Some of the social pathologies could be in forms of enticing alienation (i.e., subjugating people from a position of the subject to the position of object in social relations), increasing misinformation, aggravating existing imbalances and inequalities and the consequences for human rights.

(2) Some of the powerful nations of the global north in their pursuit for industrial growth have failed to fully implement the 1997 Kyoto protocol that seek to limit gas emissions to mitigate the effects of climate change. The US in its desire for unfelted technological advancement has gone a step further in its defiance by renouncing the Paris Climate Treaty of 2017. The worst culprits of emissions at global level are regions of North America, Asia, and the EU (Nwankwo, Citation2019). Climate change affects ecological patterns that may create conflicts in certain areas. Conflicts related to these challenges could be likened to the case in the Darfur region of Sudan, where the scarcity of grazing land led to conflicts to the scale of genocide over pastoral land. African states have called on the US to scale down its emissions as the impact of climate change affects people of the global south much more than those of the global north. Effects of climate change are varied and may include acid rain, global warming, and biodiversity loss (Dunn & Shaw, Citation2001). So, climate change issues have come to shape African orientation to global governance with demands for more equitable inclusion in multilateral structures.

The 2009 Algiers Declaration Forum on climate change (the African Common Platform to Copenhagen) formed a solid framework for subsequent African claims on environmental issues (UN Economic Commission for Africa, Citation2010).

Former Ethiopian Prime Minister, Meles Zenawi made a profound speech in support of African claims in September 2009. Arguing on the collective position of the Algiers Forum of 2009 and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (Citation2010), Zenawi said,

… we (Africans) will never accept any global deal that does not limit global warming to the minimum unavoidable level, no matter what levels of compensation and assistance are promised to us … while we will reason with everyone to achieve our objective, we will not rubberstamp an agreement by the powers that be as the best we could get for the moment. We will use our numbers to delegitimize any agreement that is not consistent with our minimal position. If needs be, we are prepared to walk out of any negotiations that threaten to be another rape of our continent …

This confirms that stronger African philosophical and cultural claims for environmental justice against the biggest environmental culprits should not be understated. This statement also signals the deep resentment that Africans have on neo-imperialist tendencies such as unfair trade deals and the use of hard-power politics (particularly by the US) as opposed to the use of soft power politics approaches. On the flip side of the coin however, it can be argued that the options and influence of the African states are limited and decisions at regional or continental level remain hard to take due to Africa’s weak industrial capacity. For instance, Ethiopia’s hardline stance and a demand for a different sequencing for developing nations is—in the long run—curtailed by the fact that the US provides Ethiopia with funds to support its growing textile industry under the US initiative program, the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) (Cornelissen et al., Citation2012).

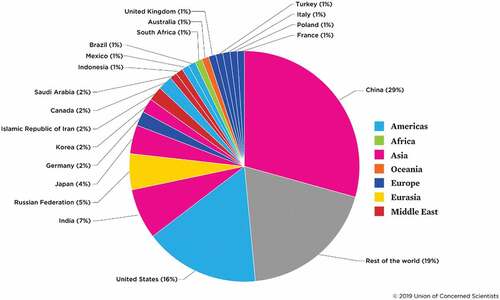

The diagram below )illustrates the carbon emissions that disadvantages Africa.

On 20 December 2019, the Dutch Supreme Court made a groundbreaking ruling by ordering the government of The Netherlands to reduce greenhouse emissions by at least 25% (Fortune Daily News, 20 December 2019).

This landmark court ruling could have similar repercussions across the world. On passing judgment, the court argued that climate change is part of the human rights discourse and as such, failure by the Dutch government to adhere to the UN Climate Convention guidelines was inconsistent with the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (European Convention on Human Rights, 1950). This ruling is a fatal blow below the belt to other governments such as the US which continue to refuse to respect international treaties on climate change. Human rights campaigners have applauded the ruling as it has the potential to inspire similar lawsuits in other countries (Fortune Daily News, 20 December 2019).

The significance of the Court interventions mentioned above is that laws are largely derived from cultural and religious conceptions but are not limited to these conceptions—laws also get insights from scientific innovations. This way, laws operate as a balancing act to “weed” out excesses from any discipline.

(3) Literary professor Lionel Trilling provides a comparison of how polities in the past centuries were held together by the commitment of people fulfilling their posts in life, whether they were craft workers or moguls: unlike in the past, people in contemporary societies are obsessed with the culture of authenticity—a self-centered preoccupation that spins on cut-throat contests—as a quality of life and criterion of art. For instance, to rise to the top in most science-related fields today such as medicine, political philosophy, engineering, economics and Information Technology, people tend to equate the dog-eat-dog type of output competition with high quality—believing that in the fight for success, the best ideas (coming at any cost) will be the ones that will shine (The Conversation, Citation2022). However, such competitions entail a zero-sum noncooperative mindset that seldom drives excellence, hence renders the enterprise counterproductive. More damningly for the UN gender and equality project, societal stereotype often equates brilliance with men. Competition is not a bad thing, but in this context, everyone suffers in a culture focused on attaining status and dominance at any cost. Adejuwon Soyinka summarized this new age of technological discrepancy when he said:

… workplaces that emphasize brilliance are perceived to have a masculine work culture which undermines gender diversity due to the ruthless competition that glorifies traits such as aggression. Traditionally, women are taught to be modest, kind, and cooperative, so, such aggressive and competitive work atmospheres might ultimately not appeal to women. To thrive and succeed in so-called modern and technologically driven workplaces, employees must appear tough, conceal any weaknesses, put work above all else, be ready to step on others, and constantly watch their backs … (The Conversation, Citation2022).

4.2. Excesses of culture and religion and how they are mitigated by scientific underpinnings

Harmful cultural and religious practices such as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) which are still practiced in some parts of Africa particularly in West Africa, and the practice (in some countries of the Middle East) of stoning women to death (women who commit adultery), and honor killings cannot be justified in contemporary IR theory or in international jurisprudence. These outmoded and otherwise primitive practices of the Victorian times have no place in contemporary human rights discourses of the twenty-first century. Such cruel treatment of women under the banner of religion, culture, and national sovereignty is not only a transgression of international human rights laws but also against religious norms themselves—religious teachings emphasize forgiveness and repentance (Kusha & Ammar, Citation2014). These practices amount to violence against women because they violate the tenets enshrined in international human rights protocols, which are sanctioned by the UN such as the Convention for the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1979) and the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (Citation1948).

Donnelly (Citation2013) defines human rights as rights that are equal, inalienable, and universal, even with considerations of cross-cultural relativism. The main argument here is that human rights are not culturally relative because culture is not the cause or a factor in the development of human rights practices. Donnelly (Citation2013) further opines that the primary sense of universality is not merely compatible with but necessarily includes an essential element of relativity. The question, therefore, is not whether human rights are universal or relative, but how human rights are. To put it another way, human rights transcend cultural and religious boundaries. In this age of science and technology, there are better ways of providing remedies for those who are accused of wrongdoing. Religious people claim that God is merciful—so, if this claim is indeed valid, one must wonder then how a merciful God would be pleased to see women being stoned to death.

However, part of the bigger challenge in the global south is that most of the population seem to be trapped in cultural and religious orthodoxy whereby there is an unhealthy growing culture of religious fanaticism. A strong belief in superstitions, witchcraft and magic by political and church leaders has taken a new twist: politicians promise miracles to the population and so do the fake priests and prophets. In Zambia for instance, conmen of all hues purporting to be prophets have taken advantage of the illiterate masses to swindle them of their money through the provision of 'prayers' and 'holy anointing oil'. In Tanzania, 20 people in 2019 were reported to have died at a stadium stampede as they attempted to get so-called 'holy anointing oil' from a self-styled pastor who was promising prosperity and cure of disease from unsuspecting worshippers. So, education (and by extension, scientific knowledge) is an important element for the population if these shallow and primitive practices are to cease (The Guardian Newspaper, 2 February Citation2020).

Another area that has become prominent in the cultural, religious and political discourse is that of homosexuality: while culture and religion in most conservative polities such as Africa forbid gay practices on grounds that such practices are Western, empirical evidence suggest that gay practices have always existed on the continent. The argument that homosexual practices were brought by European colonialists have failed to hold water—facts on the ground simply do not support this simplistic narrative. Oral African history of the 1800s has confirmed that homosexuality is not new in Africa and has always existed … what is new in Africa is homophobia which Europeans brought clothed in religious doctrines (Tendi, Citation2010). Attempts therefore by some (African) governments to pass legislation banning homosexuality are not tenable in the long run. Discriminatory tendencies such as legislation are not a sustainable solution to this matter—the real solution lies in societies coming to terms with the reality that gay practices (like prostitution) do exit in every polity. Scholars such as Msibi (Citation2011) and Mwaura (Citation2006) would argue that scientific evidence has shown that homosexuality is not a fashion show, but an orientation. In this modern age of fast-track scientific evolution, homosexuality need not be a topic that carries headlines … it is not an issue … it is like hair color … some people have blonde hair while others have black, brunette, or red hair. For instance, some women are so hairy that they even have beards on their chins—inclinations that are usually associated with men, while some men have soft voices that are often associated with the female gender. These differences demonstrate the diversity of the compositions of human biology. From this standpoint, it makes little sense, if at all, for any government to attempt to legislate an orientation. A preference of who someone choses to love lies outside the province of the religious dictates and government control (Zwissler, Citation2019). Like feminists, homosexuals also believe that they live in a culture of contempt where they are still devalued based on what they are or look like. Modern societies cannot encourage cultural practices that perpetuate forms of stereotyping and discrimination (Dunton & Palmberg, Citation1996).

A turning point in this gay debate can be illustrated by the June 2019 landmark Botswana High Court decision, which decriminalized homosexuality. In this court case, cultural relativists had put up a challenge in court arguing that homosexuality was eroding cultural values of Botswana and therefore urged the court not to grant homosexuals the right to exercise their sexual orientations freely. But on passing judgement, Judge Michael Leburu said that a democratic society is one that embraces tolerance, diversity, and open mindedness. Discriminatory laws not only serve as a detriment to gay people but holds back all of society. Specifically for Africa, the lofty aspirations inscribed in the much-proclaimed African Renaissance project cannot truly be realized without the full liberation of all marginalized groups. Neela Ghoshal, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch applauded the Botswana judgement; that it sent a powerful precedent on the continent that gay laws belong in the museum or the archives, not in modern life. Culture is malleable—not static—and is a patriarchal construct that can be reconstructed (BBC News, Citation2019).

Anglican Archbishop of South Africa, Desmond Tutu, a rare religious voice on gay rights argued that gays are born that way. Dunton and Palmberg (Citation1996) points out that Tutu opined that:

… we blame them (homosexuals) for something which has become clear that they cannot do anything about. If indeed homosexuality was a matter of choice as cultural relativists would like us to believe, then gay people must be the craziest coots around to choose a way of life that exposes them to so much hostility, discrimination, and suffering. It is akin to saying that a black person voluntarily chooses a completion and race that exposes him or her to all the hatred, suffering and disadvantages to be found in a racist society.

Africa has witnessed placards displayed by anti-gay lobbyists and chants from cultural and religious loyalists saying, 'God created Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve'. On face value, these pronouncements might appeal to larger portions of the religious constituency but on critical examination, these sentiments lack reflective reasoning. For, while most religious people do not accept homosexuality, there are also other people who do not believe in religion itself. The right to believe in religion and the right not to believe in religion are all equal rights and yet most religious people assume that everyone must be religious—this is one of the shortcomings of religion as this attitude tends to be used as a footstall of entrenching intolerance in the wider society, a trait of religious fanaticism. This gap and lack of self-awareness by the religious fraternity needs much sensitization and (scientific) education. Here, the critical role of science in shaping peoples’ thought processes need not be overemphasized.

Former South African High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Cheryl Carolus implored African governments not to condone actions that promote any form of intolerance. In South Africa, for instance, it is government policy that the South African society needs to be characterized by diversity and cultural pluralism where marginalization of minority groups or citizens with different sexual orientation is no longer an acceptable standard. Modern society is demanding a more inclusive conception of citizenship. Dunton and Palmberg (Citation1996) point out that Ambassador Cheryl Carolus argued further that:

… for the same reason that we oppose racism and sexism, we oppose homophobia. Our position has been to oppose those who felt that we should go for generalities in the constitution because we have a past of such oppression (apartheid, colonialism, and imperialism) that we feel the need to list the areas where there is still oppression …

The Botswana high court ruling has signaled the death knell of such 'no gay' policies—notions that would never be tolerated if they referred to a person’s race, gender, or religion. Human dignity is harmed when minority groups are marginalized. The court ruling is a hint that the justice train is on the move in Africa. Political observers have predicted that despite current objections on gay rights, at some future time, most African governments will catch up with mainstream IR opinion on homosexual rights. When marriage equality for gays finally occurs, people will wonder what the fuss was about. The reality of the twenty-first century is that the states’ capacity to regulate political identities and loyalties of its citizens is gradually being weakened by the increase of global interconnectivity particularly the areas of science, information technology, finance, economics, and transnational trade (Linklater, Citation2007).

The significance of the emphasis on the importance of human rights protection here is that in contemporary IR, the human rights discourse—like education—lends much of its efficacy from scientific and philosophical underpinnings. It is argued that human rights protection makes it possible for individuals to unlock their potential and achieve limitless success in their endeavors. From a scientific perspective therefore, individuals can only fully realize their potential in an environment that is free from abuse, exploitation, racism, discrimination, marginalization, prejudice, racial profiling, stereotyping, and poverty.

5. Conclusion

This study examined how science, culture, and religion influence each other in shaping societal dispositions. To achieve this, the study took a transdisciplinary approach, which disbanded the boundaries between these conventional disciplines and attempted to (re)construct their meaning in the context of real-life societal problems. On the one hand, science lends its utility from pragmatic and experimental approaches such as employing technological methodologies that may involve computational methods, data archives, artificial intelligence and empirical observation: this is how science interprets world phenomenon. On the other hand, the ontology of culture and religion spins on hermeneutics, rhetorical, and historical approaches to interpret world occurrences: the philosophy of culture and religion assumes that epistemology is incomplete if it ignores history.

While this cultural and religious foundation cannot be dismissed as idle speculation, societies must be wary of the snares of blanket reliance on history as an unchanging database for evaluating societal premises and insights. Similarly, scientific novelties must also be scrutinized because some of their processes do not lend themselves to ethical designs. The overall context of this study’s argument, therefore, is that due to the contingent nature of life situations, it is imperative that we pay attention to when and how the meanings of some of the key societal notions are undergoing transformation. This study has endeavored to advance a distinctive conceptual argument that draws out the wider implications that surround the three disciplines under discussion. As such, the winner takes all notion holds little currency in this study's equation—instead, the equation encourages the give and take synopsis. As Rousseau argued, the ontology of human nature is best appreciated from the prism of integration, adaptation, and cooperation rather than from competition and contestation. The implication of this proposition can be summarised using Karl Marx’s philosophical inference that the less you are, the more you have.

The paper has shown how, from time in memorial, there have been conflicting positions and competition between science, culture, and religion in addressing various aspects of human endeavor. Although there are some compatibilities, it can be argued that there seems to be more disagreements than agreements. Due to the differing standpoints and orientations between science, culture and religion, these gaps and competing assumptions will most certainly remain permanent features of the scientific, cultural, and religious discourses.

These diverse viewpoints will continue to shape and moderate each one of these disciplines in ways that would otherwise not be possible if they were compatible with each other. This is a healthy development for mitigating the effects and excesses of either science or religion and culture. This way, they operate as barometers of social, cultural, political, and economic consciousness in society.

Education

4th Year Doctoral Student in Political Science (Enrolled in 2018)

(University of Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic).

MA Political Theory

(Cardiff University, United Kingdom).

MSc Economic & Social Studies in International Relations

(Cardiff University, United Kingdom).

BSc Politics & International Relations

(University of London, United Kingdom).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Philosophical Faculty—Department of Political Science of the University of Hradec Kralove for their academic assistance in my research studies.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nsama Jonathan Simuziya

Nsama Jonathan Simuziya is a PhD candidate as well as Teaching Assistant in the Philosophical Faculty––Department of Political Science (African Studies) at the University of Hradec Kralove. Currently, he teaches an undergraduate module entitled: 'Non-State Armed Groups in Africa'.

His research areas are in Human Rights & Democracy, International Security & Humanitarian Intervention, Comparative Politics, International Relations Theory, Foreign Policy Analysis, and Philosophy of Social Sciences.

References

- BBC News. (2019). Botswana decriminalizes homosexuality bbc.com/news/world-africa-48594162

- Cataleta, M. S., & Cataleta, A. (2020). Artificial intelligence and human rights, an unequal struggle. CIFILE Journal of International Law, 1(2), 40–19.

- The Conversation. (2022, March 23). An emphasis on brilliance creates a toxic, dog-eat-dog workplace atmosphere that discourages women. https://theconversation.com/an-emphasis-on-brilliance-creates-a-toxic-dog-eat-dog-workplace-atmosphere-that-discourages-women-178525

- Cornelissen, S., Cheru, F., & Shaw, T. M. (2012). Africa and international relations in the 21st century. Macmillan.

- Crewell, J. W. (1990). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. Sage.

- Dawkins, R. (2002). Militant Atheism. TED TALKS. ted.com/talks/Richard_dawkins_militant_atheism?language=en

- Donnelly, J. (2013). The relative universality of human rights. Human Rights Quarterly, 29(2), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2007.0016

- Draper, J. (1874). History of the conflict between religion and science. Appleton.

- Dunn, K., & Shaw, T. (2001). Africa’s challenge to international relations theory. Palgrave.

- Dunton, C., & Palmberg, M. (1996). Human rights and homosexuality in Southern Africa (2nd ed.). Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Forrest, B. (2000). Methodological naturalism and philosophical naturalism. Philo, 3(2), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.5840/philo20003213

- Fortune Daily News. (2019). Climate Change Litigation Enters New Era as Court Rules That Emissions Reduction Is a Human Right. Retrieved December 20, 2019. fortune.com/2019/12/20/climate-change-litigation-human-rights-netherlands

- The Guardian Newspaper. (2020, February 2). Crush during rush for ‘blessed oil’ at Tanzania church service leaves 20 dead. theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/02/crush-during-rush-for-blessed-oil-at-tanzania-church-service-leaves-20-dead

- The Guardian Newspaper. (2022, May 24). Sisters allegedly murdered by husbands in Pakistan honor killing. https://uk.yahoo.com/news/sisters-allegedly-murdered-husbands-pakistan-053055130.html

- Hammer, M. G. (2019, December). Theorizing religion and the public sphere: affect, technology, valuation. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 87(4), 1008–1049. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfz065

- Harrison, P. (2015). The territories of science and religion. University of Chicago Press.

- Human Rights Watch. (2020). Dutch ruling a victory for rights of the poor. Retrieved February 6, 2020, from hrw.org/news/2020/02/06/Dutch-ruling-victory-rights-poor

- Idinopulos, T. A. (1998). What is religion? Crosscurrent, 48(3), 366–380.

- Koltonski, D. A. (2014). Marx and critical theory. Koltonski, Daniel. https://www.amherst.edu/academiclife/departments/courses/1314S/PHIL/PHIL-366-1314S

- Kuhn, T. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago University Press.

- Kusha, H. R., & Ammar, N. H. (2014, January 2). Stoning women in the Islamic republic of Iran: Is it Holy Law or gender violence. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 5 (63), 1–9.

- Lama, D. (2005). The Universe in a single atom. Harmony Books.

- Linklater, A. (2007). Critical theory. In M. Griffiths (Ed.), International relations theory in the 21st Century (pp. 47–59). Routledge.

- Lumumba, P. (2020, October 8). Africans are waiting in vain for God: Africans must start thinking without the box. Lumumba, Patrick. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0jBzx3-QQY

- Moses, W. J., & Knutsen, L. T. (2007). Ways of Knowing. In Moses, Jonathan, and Knutsen Torbjorn (eds.),Competing methodologies in social and political research. Palgrave McMillan.

- Msibi, T. (2011). The lies we have been told: On (homo)Sexuality in Africa. Africa Today, 58(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.58.1.55

- Mwaura, P. (2006, June 5). Homosexuality un-African? It is a big lie. The Nation.

- Nwankwo, C. F. (2019). Understanding US government reluctance to accept legally binding emissions reduction targets: The import of elite interest convergence. Open Political Science, 2(1), 1–95. https://doi.org/10.1515/openps-2019-0002

- Pedersen, E. O. (2015). Religion is the opium of the people: an investigation into the intellectual context of marx’s critique of religion. History of Political Thought, 36(2), 354–387.

- Pew Research Centre. (2009). Scientists and Belief. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2009/11/05/scientists-and-belief

- Podvoyskiy, D. G. (2022). “Dangerous modernity!”, or the shadow play of modernity and its characteristics: Instrumental rationality-money -Technology (Part 2). RUDN Journal of Sociology, 22(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2272-2022-22-1-40-57

- Popper, K. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. Hutchinson.

- Prinz, J. (2012). Beyond human nature: How culture and experience shape our lives. Penguin Books.

- Rees, J. A. (2017). Religion and culture. In S. McGlinchey (Ed.), International relations: A beginner’s guide (pp. 98–111). E-International Relations.

- Rosenberg, A. (2005). Philosophy of science. Routledge.

- Rumsfeld, D. (2011). Known and unknown: A Memoir. Penguin Group.

- Simuziya, N. S. (2021). Universal human rights vs cultural and religious variations: An African perspective. Cogent Art and Humanities https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311983.2021.1988385

- Taam, C. (1953). On Studies of Confucius. Philosophy East & West, 3(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.2307/1397261

- Tendi, B. (2010). African myths about homosexuality. Guardian Newspaper. Retrieved March 2010, 23, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/mar/23/homophobia-africa-gay-rights

- Touray, O. (2021, September 23). Powerful lecture on erosion of African value system: Can youths redeem the trend?. Osun State University. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ah5o2ghBUic

- Uduma, U. O. (2014). The question of the ‘African’ in African philosophy: In search of a criterion for the Africanness of philosophy. Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, 3(1), 11–19.

- UN Economic Commission for Africa. (2010). Report on climate change and development in Africa. OPM10-0009-ORE-Report on Climate Change and Development in Africa. 28 March 2010

- United Nations (UDHR). (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr

- United Nations (UNESCO). (1945, November 16). The constitution of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ddb73094.html

- Vannetzel, M. (2017). The Muslim brotherhood’s ‘virtuous society’ and state developmentalism in Egypt: the politics of ‘goodness’. International Development Policy Series, (8), 220–245.

- Vorvornator, K. L. (2022). Do we go or we stay? Drivers of migration from the global South to the global North. African Journal of Development Studies, 12(1), 71–87.

- Whewell, W. (1834). On the Connexion of the physical sciences. By Mrs. Somerville. Quarterly Review, 51, 54–68.

- White, D. A. (2009). A history of the warfare of science with theology in Christendom. D. Appleton and Company.

- Woodhead, L. (2011). Five concepts of religion. International Review of Socialogy, 21(1), 121–143.

- Zwissler, L. (2019, December). Sex, love and an old brick building: A United Church of Canada congregation transition to LGBTQ inclusion. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 87(4), 1113–1152. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfz045