?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Ethiopia has been experiencing resettlement programs primarily as a response to the tragedy of land degradation. The program, however, resulted in massive deforestation in the resettled sites. This study, therefore, aimed at evaluating the impact of resettlement on the moist evergreen Afromontane forest cover between 2000 and 2018 in the Hawa-Galan district. Landsat TM of 2000, ETM+ of 2010, and OLI of 2018 were used to detect forest cover change. Likewise, an explanatory sequential approach of mixed research design was used. Hence, 118 participants out of the total 2232 indigenous and resettled households were employed to survey the impact of deforestation.The study area lost 55% of its total area over the last two decades, corresponding to average deforestation rates of 2.06, 6.75, and 4.14% for the corresponding periods: 2000–2010, 2010–2018, and 2000–2018, respectively. Our findings also revealed the demographic, socioeconomic, and backgrounds of the resettlers were the prominent triggers. Conversion of forests to other uses will have far-reaching impacts on the residual biodiversity and ecosystem services. Therefore, in the light of resettlement, it is high time for the Ethiopian government to revisit its intervention strategies and resettlement policies in the forest priority areas.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Promoting resettlement programs to advance modernization has been a great concern to the Ethiopian government over the last few decades. Ethiopia has been implementing this policy in response to the tragedy of recurrent drought due to severe degradation. However, in the event of deforestation in the resettlement sites, such strategies might be ineffective in maintaining the impacts. Our analysis echoed this fact that resettlement programs pose a significant influence on forest sustainability in the Hawa-Galan district. Since the study area is a forest priority area, the resettling of migrants would expose deforestation to peril. The conversion of forests to other uses in the study area will have far-reaching impacts. Therefore, in the light of resettlement in the forest area, it is high time for the government to revisit its intervention strategies and resettlement policies.

1. Introduction

Resettlement is a planned or spontaneous phenomenon of population redistribution. It can be voluntary or forced; it can also be temporary or permanent (Abebe et al., Citation2019; Deribew, Citation2020; Gebre, Citation2002; Wilmsen & Wang, Citation2015). Resettling drought, earthquakes, floods, and other natural calamity sufferers evacuated to relatively safer sites has been one of the areas where governments of developing countries have been very active since the middle of the last century (Belay, Citation2004; Limenih et al., Citation2012). Such activity has been perceived as a problem and solution to housing needs in the rapidly growing cities of many developing countries (Getahun et al., Citation2017). The study confirms resettlement policy has a positive and negative impact on the environment, and socio-economic planning policy (Boillat et al., Citation2015). Even though the government’s goal of resettlement policy is advancing towards modernization, it can cause multiple, complex impacts on social, economic, cultural, and environmental characteristics on the destination areas (Pankhurst, Citation1990; Shchankina, Citation2019). Generally, governments prefer to relocate famine-affected villages to safer locations, even if the villagers prefer to remain in their original location and receive relief assistance. Accelerated deforestation, soil degradation, and depletion or pollution of surface and subsurface water resources are some of the evidence of the severe environmental degradation caused by resettlers in different parts of the world (Boillat et al., Citation2015; Hammond, Citation2008). In this regard, there is a sign of a decrease in forest loss, but it is still alarmingly high due to different triggers that have been reported. Accordingly, a study confirmed that 8.3 m ha of forest loss was recorded between 1990 and 2000, though it significantly decreased to 5.2 m ha in the years between 2000 and 2010 (FAO Citation2010). Despite high average plantation (5 million ha since 2000), forest cover loss due to ineffective resettlement policies is a serious global problem that has worsened in Sub-Saharan African countries (Goll et al., Citation2014).

Ethiopia has been practicing population resettlement going back to the 1960s and early 1970s under the imperial regime (1930–1974) when, through a combination of spontaneous and planned resettlement programs, mainly from famine-affected and degraded areas (Deribew & Dalacho, Citation2019; Rahmato, Citation2009). This relocation of peasants was highly experienced from northern highlands (Tigray and Wollo) areas suffering from high population pressure, soil erosion, and deforestation to the south and southwestern regions where there are scattered populations, under-utilized and fertile land (Abera et al., Citation2020; Clarke, Citation1986; Pankhurst, Citation2009; Rahmato, Citation1988).

Resettlement schemes in Ethiopia have side effects on the environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural settings of the area (Abebe et al., Citation2019; Brink & Eva, Citation2009; Deribew, Citation2019; Porter, Citation1986). These studies indicate that there was more deforestation, overexploitation of forest resources, expansion of agricultural lands into the frontier of forest cover, and grazing lands in their respective destination areas than natives did. The recent internal villagization program has also resulted in large damage to the natural forest of the resettlement areas. Forest cover was diminished from 19.55% in 1986 to 11.8% by 2001 in forest land in the Bench Maji zone resettlement site (Wubie, Citation2015). As a result, the resettlement experienced extensive destruction of woody plants. Moreover, research conducted to assess the impact of resettlement programs on the environment in SNNPR and Oromia regions revealed that there has been clear natural resource degradation, particularly loss of forest, fertile soil, and wildlife resources from the resettlement sites (Assefa and Bork, Citation2013). The forest and woodlands in the resettlement sites had to be cleared to create farmland, for house construction, for firewood, etc.

In the recent resettlement programs conducted since the 2000s, migrants from densely populated areas, northern regions of Ethiopia, might have been involved in environmental damage despite differences in scale. The study area, the Hawa-Galan district, is among the major destinations of resettlers in the southwestern regions of Ethiopia. It is where resettlers have uncontrolled access to natural forest resources. In the district, attention has not been given to the impact of resettlement on environmental aspects. Large areas of forest, shrubs, and bushlands in the area have been cleared to satisfy their needs. It is hypothesized that these resources are being reduced due to the rapid population growth of the resettlers and their increasing need for construction materials and the expansion of agricultural land to yield more production. Based on the researchers’ prior knowledge and views from agricultural officers, extensive forest-covered land has been converted into cultivated land and built-up areas. From field visits, it is evident that forest cover change is very widespread, and continuing at an alarming rate.

The impact of resettlement schemes on the livelihood of the host communities and/or settlers, food security and natural resource utilization (Deribew, Citation2020; Getachew, Citation1989; Wayessa & Nygren, Citation2016); on land use/ land cover change (Messay & Woldesemait, Citation2011); on rangeland condition and natural vegetation (Mulugeta, Citation2009; Yonas et al., Citation2013) were conducted in different resettlement sites in Ethiopia. Despite the aforementioned studies were conducted in various parts of Ethiopia, none of them considered the impact of resettlement on the extent and rate of forest cover change, which was directly addressed and determined using combined geospatial techniques and socioeconomic in the study area, where significant numbers of households resettled. These resettlers in the study area introduced and taught natives who were entirely dependent on traditional economic activities (hunting, gathering, and shifting cultivations) for the era to forest destruction and modern farming practices.

So the current lack of knowledge on the extent and rate of forest cover change that resulted in the implementation of the resettlement program in the study area should be addressed to promote sustainable forest management. Forest cover change due to the recent resettlement in the early 2000s remains the main problem of the interest of research and the investigator is encouraged to address it so that coherent conservation measures could be suggested and implemented to protect and wisely use the valuable forest resources. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the impacts of the recent resettlement programs on moist evergreen Afromontane forest loss in the Hawa-Galan district through detection and mapping of forest cover change and deforestation in space and different periods (2000, 2010, and 2018). The collection and analysis of information on the impact of recent resettlement on forest cover loss, and investigating the socio-economic and environmental impacts of deforestation in the study area have also been assessed. The outcome of this study adds to the literature in the field of biodiversity, forestry, ecosystem, and society to investigate resettlement programs and forest loss, and potential drivers of deforestation, thereby offering site-specific forest management and participatory measures.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

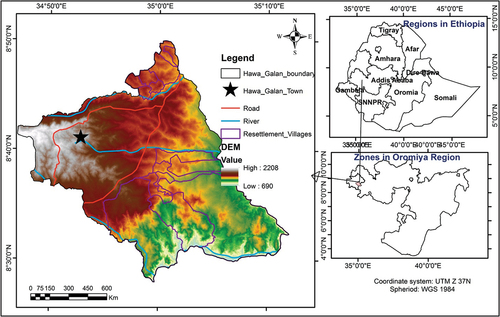

The study was conducted in the Hawa-Galan district in the Oromia National Regional State of Ethiopia. The study area extends between 8°28’ to 8° 51’ North latitude and 34° 46’ to 35° 12’ 3″ East longitude and covers a total area of about 82779 ha ().

Topographically, it is generally characterized by an alternation of flat plateaus, undulating hills, and mountains with a mean elevation of 1465masl. The study area receives annual rainfall ranging from 1167–1500 mm, whereas the average temperature varies between 18 and 28°C.

According to the Central Statistical Authority (Central Statistical Authority (CSA), Citation2013) population data projected for 2017, the district has a total population of 123,957 of whom 114,985 are rural population. The major livelihoods of the population of the district are mainly dependent on forestry and subsistence mixed agriculture that entirely depends on the growing of crops and rearing animals. The major crops grown in the study area include cereals: maize (Zea mays), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), wheat, barley (Hordeum vulgare), millet, and teff (eragrotis tef)), Pulses (field peas, haricot beans, and soy able horse beans), fruit trees (mango, banana, papaya), root crops or tuber crops (onion, potato, yam, inset, carrot, sugar cane, and anchote, Oilseeds (noug, groundnut, sesame, rapeseed, and linseed), and cash crops such as Coffee (Coffea Arabica).

2.2. Study design, sampling design, and data sources

2.2.1. Study design

In this study, the explanatory sequential approach of the mixed research design was implemented using the formula developed by Creswell (Citation2005). The overall intent of this design is to have the qualitative data that helps to explain in more detail the initial quantitative results. With this particular study, the spatial data and household survey data were considered as quantitative data whereas the socio-economic data generated through key informants (KII) and Focus Group Discussion (FGDs) was qualitative. Therefore, a household survey from village administrations was conducted to recognize the relationship between observed forest cover change and local livelihood responses in the study area. As formalized, 118 indigenous and resettled household villagers were selected to respond to the structured questionnaire (). These were diverse in gender, age (above 50 who can narrate the history of the forest in the area), indigenous, and migrants. Totally thirteen in the number key informants: local elders both from the indigenous and the migrants, experts in agriculture, rural land and environmental protection offices, development agents, women, and managers of the villages were selected. All these were purposefully selected to represent the widest possible range of information on the impact of resettlement on forest cover change. The FGDs comprising 8 to 12 participants were held in each of the four selected villages of the resettlement sites in the study area. Local elders from both indigenous and migrant communities (only voluntary) who are more knowledgeable in discussions were purposefully chosen as participants. In this study, ethics approval and consent to participate is not applicable. As researchers, accordingly, we had paid attention to the basic research ethical issues: voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and result communication, only to mention a few. Since it is not the objective of this study, no human experiment has applied in this study. In this study, therefore, the output of the socio economic data i.e. information (from the participants) on the ethical processes of this study had implemented the specific research ethics guidelines, and the guideline of this journal. Data obtained through KII interviews and FGDs were narrated for analysis and interpretation. The data collected from households was analyzed using the SPSS software package, and summary statistics were presented using frequency tables, percentages, and graphs. This data was carried out to provide information on the resettlement’s impact on the land-use dynamics and deforestation of the study area in the study period. The socioeconomic aspect of the study was used to explore the perception of settler and host communities’ on factors that contributed to deforestation and how the resettlement affects the forest resources in the study area. And it was obtained through the household survey (questionnaire), KII, and FGDs, which suggested these, were used to supplement remotely sensed data. The purpose of the mixed-method design is to collect data from different sources and apply the triangulation method to enhance and improve the quality of the data during the analysis and interpretation phase.

Table 1. Target population and sample size of the study of area

AL = Agricultural land, BL = Bare land, BL/SL = Bush/shrub land, FL = Forest land, ST = settlement, WL = wet land

2.2.2. Sampling design

The study area district is purposefully chosen based on prior knowledge of the area. In the Hawa-Galan district, there are 29 rural kebele administrations. Among these rural kebele administrations, 14 rural kebeles are resettlement sites in the district. These resettlement kebeles are grouped under four clusters: Birkii Canqo, Birkii 21, Birkii 18, and Birkii Gudina Mucoo. One rural kebele from each cluster was chosen at random, for a total of four rural kebeles: Chiro Tulama, Chiro Badeyi, Burka Tokkuma, and Mada Talila, with 731, 589, 242, and 670 household numbers, respectively. Accordingly, sample households were derived as indicated in Table . This sampling technique was used to ensure that all resettlement kebeles had an equal chance of being selected. Depending on the available time and resources, the sample size of this study was determined by using the following Equationequation 1(1)

(1) formula of sample size determination which is adopted by Kothari (Citation2004).

Where n is the sample size, Z standard variation at 95% confidence interval (1.96), P is sample proportion in the target population, estimated to have the characteristics being measured (0.03) as q is 1-p, N is the size of the target population, e is the estimated(standard error within 3% of the true value of (0.03). Therefore, the desired sample is;

Based on the sampling frame obtained from the four rural kebeles administration offices, 118 households were sampled for the questionnaire survey using proportional stratified random sampling techniques (Table ). In such proportional stratified sampling, the size of the sample selected from each kebele is proportional to the size of that kebele’s entire household population.

2.3. Data used and image pre-processing

Cloud-free Landsat ETM+ (2000), Landsat TM (2010), and Landsat OLI (2018) satellite images were obtained for free from the US Geological Survey (USGS) to assess forest cover change. Because the remotely sensed satellite imageries were collected at different times, radiometric correction (Chander et al., Citation2009) and atmospheric correction (Vermote & Saleous, Citation2006) were performed in the ERDAS imagine software.

2.4. Forest cover mapping

The study area’s forest cover was mapped using a three-time series of Landsat images: TM from 2000, ETM+ from 2010, and 2018 captured during the dry period to obtain cloud-free images. The main purpose of the utilization of the three series images was to quantify and map the extent of forest cover change and deforestation in the study area over the past 18 years. The 2000 image was used to map the extent of forest cover and to investigate the LULC conditions before the implementation of the resettlement scheme. The 2010 and 2018 images were used to see the post resettlement conditions/trends of the study area in terms of forest cover change. It gives a clear picture of the level and intensity of deforested land. In this regard, forest land units for 2000, 2010, and 2018 were mapped following the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO Citation2006) guidelines, whereby a land unit is considered forested if it covers an area of > 0.5 ha and has a canopy cover of more than 10%. Accordingly, forestland units in the study area were identified visually based on their texture and color, typically red or infrared on false-color composite imagery (Deribew, Citation2019).

The annual rate of deforestation was calculated for each span period using the following EquationEquation 2(2)

(2) formula developed by Puyravaud (Citation2003).

Where P is the percentage of the annual rate of loss and A1 and A2 refer to the area of forest cover at times t1 and t2, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Forest cover change from satellite images

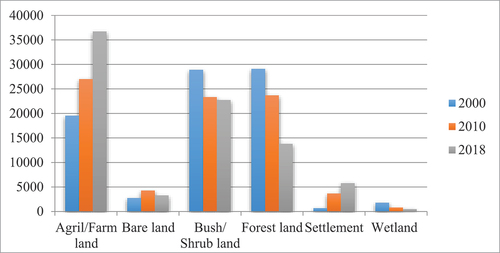

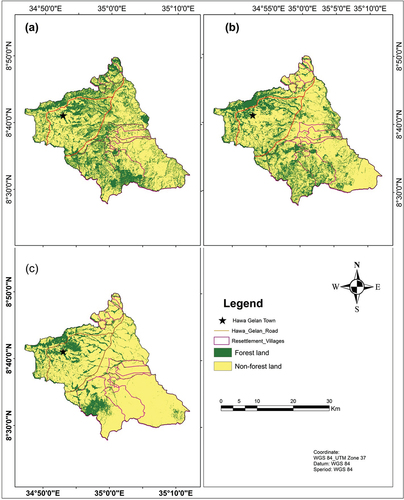

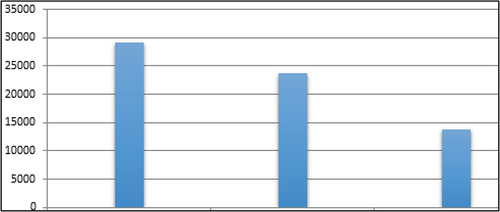

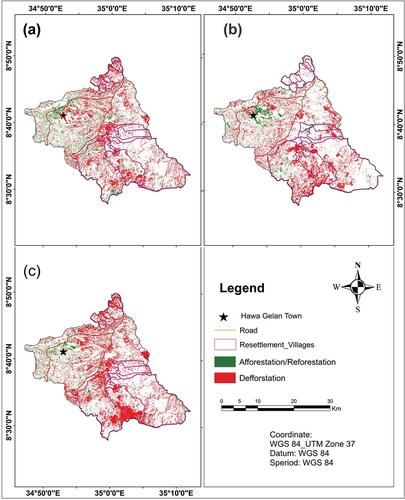

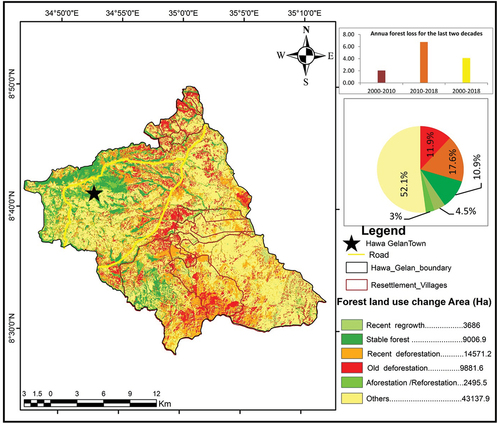

Results of forest cover change mapping revealed that the forest cover in the study area drastically declined from 29,090.61 ha (35.14%) in 2000, to 23,683.23 ha (28.61%) in 2010, to 13,798.17 ha (16.67%) in 2018 ( and ). This is a shrink of about 55% in two decades. This resembles the average annual deforestation rates of 2.06, 6.75, and 4.14% for the corresponding periods: 2000–2010, 2010–2018, and 2000–2018, respectively (). The highest deforestation rate of 6.75% coincides with changes in demographics through recent resettlement and socioeconomic situations during the period in the study area. Consequently, it was during the recent deforestation period (2010–2018) where nearly 14,571.2 ha (17.6%) forest loss occurred and much of the forest land was converted into built-up areas and croplands (). Overall, during the last two decades (2000–2028), only 9006.9 ha (10.9%) forest land remained stable, and 2495.5 ha (3%) forest recovered. The rate of forest loss during the entire study period of 4.14% suggested the 1970s-1980s when most migrants from acute drought-prone areas (e.g., northern and north-central regions of Ethiopia) were resettled in parts of the study area.

Figure 5. Map that shows deforestation and afforestation during 2000–2010 a, 2010–2018 b, and 2000–2018 c.

Figure 6. Forest cover trajectories due to recent resettlement programs over the past two decades (2000–2018).

Table 2. The extent of Land use/ land cover classes change in the study area (hectare)

3.2. The views of respondents and ground survey observation on the impact of resettlement on forest cover loss

In this study, 118 of 2232 selected households participated in the interviews. In this regard, 20% were selected from migrant households, which resemble the evaluated tool percentage of migrant household heads. About 4.2% of the respondents hold a college diploma and above, and 103 and 9 of the total respondents were agrarian and government employers, respectively (Table ).

Table 3. Household characteristics of the respondents and their impacts on forest

According to the household survey results, about 96% were male-headed households while 4% were female-headed households. Both sexes contributed to the deforestation of the study area even though the degree varies. The analysis of FGDs revealed that women were responsible for most of the household activities and collection of firewood and small timber from the forest. Similarly, the participants revealed that males are also responsible for the removal of the forest for agricultural land and settlement expansion as well as for house construction in the study area. Generally, the survey results showed that in the study area, both sexes are responsible for deforestation. The family size of the respondents was one of the factors that affected landholding size and agricultural expansion of farm households in the study area. With increasing numbers of household sizes, there has been a related change in the pattern of agricultural land, which is essentially smallholders depend on expanding the cultivated area, often into vegetation cover areas rather than adopting intensification techniques in the study area.

More than 95% of the households interviewed confirmed the presence of intact forest resources and bushlands in the resettlement sites when they first knew/came to the area. Only less than 5% of the households mentioned that they didn’t remember about the area. The household respondents, the key informants, and focus group discussion participants attributed the major cause of deforestation in the study area to the inter-regional resettlement programs that were implemented in 2003/04 which had triggered the other causes like agricultural farmland expansion, population increases, high demand for wood consumption, overgrazing, informal settlement and forest fire in . Moreover, low levels of education and awareness of the conservation of the settlers pointed to be among the factors that contributed to deforestation in the study area.

Table 4. Respondents response on drivers and impacts of deforestation due to resettlement in the study area

According to the survey conducted, 83% and 17% of the respondents have lived in the study area for 10–20 and > 20 years, respectively. The results revealed that the areas, particularly the resettlement sites, were covered by dense forests before the coming of the settlers. The respondents confirmed that the area was covered by dense vegetation like a forest, bushland, grazing land, and grassland. Accordingly, 43% of the household respondents reported that the area was covered by forest, whereas 52% of them concluded that the area was covered with forest and grassland mixed. They all agreed, however, on the presence of forest cover loss in their life experiences when compared to the current spatial distribution of forest resources over time. Accordingly, 94.1% of them confirmed that the forest cover has been decreasing very fast from time to time.

To satisfy the cropland requirements, the farmers in the study area are extending the farmlands to the delicate forest ecosystem in an effort to satisfy the demand for food (). Consistent with the key informants, focus group discussions and household survey respondents of the district, the vegetation area of the resettlement sites began to become agricultural land in 2003/2004 following the resettlement programs. The key informants have also confirmed that, among other places in Ethiopia, Hawa-Galan district had received large numbers of resettlers from the degraded highlands of the southeastern part, particularly from western and eastern Hararghe Zones by clearing an outsized part of the forested areas. Moreover, immigrants from northern and north-central Ethiopia (Wollo and Tigray) in the mid-1980s have also resulted in a massive scale of forest destruction. The respondents also confirmed that these ancient settlers during the military regime continued to call up their kindred from different corners of the country. In line with the respondents, the main dominant economic activity practiced in the area is mixed agriculture (70.3%). This expansion of agricultural farmland is especially intensified by resettlement programs implemented in the area.

The inevitably rising demand for fuelwood, particularly for in-home cooking and nearby towns, is the most vital for the expansion of forest depletion within the study area. The household respondent’s results revealed that 91.5% of the respondents use firewood as a source of energy in their homes. According to the informants, firewood has become more commercialized in recent years as demand has increased, particularly in the district’s town areas (Dembi Dollo, Mechara, and Gaba Robi). Moreover, the agricultural office of the district has also reported that firewood and charcoal production experienced by resettled villages were the major causes of forest cover change.

also revealed that despite a common desired effect of resettlement on development and conservation, resettlement policies have had different impacts on hosted villages of the district. Approximately 85.6% of respondents were confident that the resettled villages were to blame for the massive scale of forest destruction in the study area. The respondents confirmed that this policy had an impact on farmland expansion (27%), destruction of flora and grassland (25%), loss of avifauna (14%), built-up area expansion (12%) in the study area. Despite its impact, about 14% of respondents revealed that the resettlement conducted in the study area didn’t have an impact on the study area.

The forest products for construction purposes are obtained either by collecting or commercially depending on the accessibility. Nearly 24% saw dramatic exploitation of native trees, especially Cordia Africana (Waddeessa) for timber production (). This overexploitation of the distributed forest ecosystem for local construction purposes and commercialization of it has induced substantial pressure on the avifauna of the area.

One of the most undesirable side effects of the resettlement program is that it created a loophole for informal settlements in the vicinity of the resettlement sites which affects the environmental resources (). Participants of focus group discussions and key informants revealed that unpredictable illegal migration that began with the implementation of the resettlement program in the study was one of the factors that initiated forest degradation in the area. The illegal settlers come to the area using their links to those who were legally resettled and gradually settle in the forests. In the 1970s and mid-1980s, in addition to migrants from northern and north-central areas, many people from different areas of eastern and western Hararghe Zone (origin of former settlers) came to the area of their interest without the knowledge of the local government, indicating that this long-standing problem was destroying the area’s forest cover. This has been reported by respondents and key informants as being the prominent problem that puts tough pressure on the remaining forests and the environment in general.

One can argue that unrestricted removal of vegetation cover from the land is the most important factor encouraging land degradation. Soil erosion due to land degradation in one way or another has resulted from the cumulative effect of human activity in the study area, suggesting a great effect on the economies of the local people. This is because most of those people in the area depend heavily on their natural resource bases.

Deforestation successfully brings about the loss of biodiversity, both flora, and fauna. Several plant species are being threatened due to owing to the increasing pressure. Consistent with local elderly respondents () in the area, before the disappearance of local forests, there had been an outsized number of untamed animal species found in the forest like buffalo, tiger, lion, elephant, etc. which have disappeared from the area. The decline of vegetation areas was related to a subsequent decline of wildlife through death and migration. As a result, the situation endangers both forest-bared flora and fauna species in the study area.

Key informants and focus group discussion participants cited that deforestation has become the most threatening factor in medicinal native plants. The focus group discussion also revealed that, although plants play an important role in treating various human and livestock ailments, they’re currently under pressure due to deforestation in the study area. Moreover, indigenous knowledge of the usage of medicinal plants as folk remedies is getting lost because the practice has been seizing up with the disappearance of the species.

4. Discussion

Results from this study show that the study area has experienced widespread and rapid forest loss over the past two decades (2000–2018). The recent resettlement program in the early 2000s and inter-resettlement up to 2010 resulted in ecological deterioration. This is in line with the findings of Getahun et al. (Citation2017), and Yilak and Debelo (Citation2019) who detected acute deforestation of moist evergreen Afromontane forests in southwest Ethiopia and Chamen-Didhessa forest in southwestern Ethiopia, respectively. The same experience has also been observed in Laos, Southeast Asia, where resettlement policies are found to be responsible for forest loss that occurred in all resettled villages: Luang Prabang, Phongsaley, Houaphan, and Salavan provinces (Boillat et al., Citation2015). In contrast, the study reported in the Lembus forest in Kenya found that a decline in forest cover destruction by 3.2% over the past two decades (Kimutai & Watanabe, Citation2016). They confirmed that community participation is thought to most likely be the cause of the decline of decreasing forest loss.

First, the deforestation observed in the study area can be linked to the dramatic expansion of agricultural land within the specified period because of population pressure both from the host communities and settlers who occupied the area as a result of resettlement programs. The same pattern has also been reported in western China, which is facing severe problems following resettlement policy (Liu et al., Citation2019). Yet, poverty alleviation as a basic underlying force more than a proximate cause of forest loss has been reported in Peninsular Malaysia (Miyamoto et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, in our study, natives have been practicing traditional agricultural practices: hunting, gathering, and shifting cultivation for a lifetime. Nevertheless, the migrants (resettlers) introduced modern farming practices and houses. Since then, forests have been rapidly used for different purposes, and the demand for new cropland expansions has been raised.

This demand is the result of high population pressure caused by the influx of a large number of migrants from other parts of Ethiopia. The resettlement schemes in Ethiopia have been concentrated in the west and southwest parts of the country. In 2003 and 2004, about 7927 household settlers drawn from East Hararghe and West Hararghe Zones were resettled in the Hawa-Galan resettlement sites. Various studies have investigated that the recent resettlement programs conducted in densely populated regions: Sichuan province, China (Tan et al., Citation2013), Laos PDR, Southeast Asia (Boillat et al., Citation2015), Nono resettlement sites, Ethiopia (Mulugeta & Woldesemait, Citation2011) have involved natural resources deterioration despite differences in scale. Environmental degradation due to resettled communities’ colossal deforestation has also been reported in Uganda (Ssekandi et al., Citation2017). They found nearly 81% of forest loss (vegetation and wood) for construction, domestic energy, and farmland expansion during the post-eviction stage in oil exploitation areas of Buliisa and Hoima areas.

When interviewed, over 95% of the households confirmed the presence of intact forest resources and bushlands in the resettlement sites when they first knew/came to the area. Only less than 5% of the households mentioned that they didn’t remember about the area. Besides, Messay (Citation2009) has also confirmed that acute deforestation seen in southwestern Ethiopia is relatively more severe than before recorded in the mid-1980s.

Deforestation is activated by various factors that undermine the forest cover potential and its productivity, which leads to irreversible deterioration (Deribew, Citation2020; Fisher & Colson, Citation1973; Li et al., Citation2017; Tejada et al., Citation2013). Besides, forest cover change is a direct reflection of the dynamics of socio-economic activities. Likewise, several factors stimulated by the activity of man are responsible for the massive conversion of forest cover land into other land cover and land use units in Hawa-Galan. In the study area, especially in the resettlement sites of the district, forest resources were severely deforested.

Regarding the marital status and family size of the household, the majority of the respondents (81.4%) were married and about 74% of the sampled households have 5–10 family sizes (). The family size of the respondents was one of the factors that affected landholding size and agricultural expansion of farm households in the study area. Similarly, the finding from satellite image analysis has also confirmed that deforestation for cropland expansion is found to be amplified in a large number of household resettlement sites: Chiro Tulama and Mada Talila kebeles. As a result, with increasing household sizes, there has been a corresponding change in the pattern of agricultural land, with smallholders relying on expanding the cultivated area, often into vegetation cover areas, rather than adopting intensification techniques in the study area. Similarly, Woube (Citation1995) discovered that local people with small landholdings rely more on forest products than those with relatively large landholdings in Ethiopia’s Southward-Northward resettlement sites.

As to the educational status (), 61.9% of the household respondents had no formal education while 24.6% of them had attended primary school. There were only 9.3% and 4.2% of the heads of households who have attended secondary school and have a diploma respectively. From the survey result, it might be possible to conclude that the educational level of the household respondents can determine the level of the utilization of forest and protection of the environment through their unhealthy agricultural practices and unwise use of these resources in the study area. The uprooting of tree seedlings in forest schemes of resettlement areas was one of the issues raised in focus group discussion as the best example concerning the lower awareness level of the settlers. This is in line with Belay (Citation2004) and Getahun et al. (Citation2017), that farmers with higher educational levels are expected to be better in perception and response to soil conservation and deforestation problems.

According to the results from the household survey, key informant interview, and focus group discussions, some of the causes of forest destruction in the study area were; new cropland expansion, fuel-wood and construction materials, and illegal encroachment. The same finding has also been reported by Oyinloye et al. (Citation2018), that Osogbo resettled communities in Nigeria expand their agricultural land by cutting trees and clearing, often cutting most of the trees in the fields. The sampled household respondents revealed that new cropland expansion was a major socioeconomic cause of large-scale deforestation in the study area.

Likewise, the major environmental problems in the study area, which resulted from forest cover loss () such as increased climate variability, land degradation, soil erosion as well as deteriorating biodiversity. Yilak and Debelo (Citation2019) also argued that the resettlement program has resulted in large damage to the natural forest of the resettlement area as well as the killing and fleeing of wild animals: common, endemic, and endangered animals. In general, we can conclude from the field survey results that many endemic and endangered animals are extinct and migrate to another area from the study area’s resettlement site. This situation occurred due to the massive destruction of forest resources for the resettlement program in the study area. The same study has also been conveyed in the neighboring country, Uganda, where post-eviction resettlement is responsible for important wild animals’ migration and eventual loss (Ssekandi et al., Citation2017).

As the interview with the experts of the Agricultural and Rural Development Forestry Department of the district revealed, the avifauna found in the woodland ecosystem was subjected to threat and extinction because of increased pressure from the spontaneous/planned resettlement scheme, which has many economic and ecological implications in the study area. Similarly, (Abebe et al., Citation2019; Assefa et al., Citation2013; Deribew, Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2018) revealed that the resettlement program in the forest region devastating the natural resource base, which opposes the government’s “poverty alleviation” intention.

After the implementation of the resettlement program in the study area, the role of vegetation in regulating the microclimate (weather) of the area has been reduced due to its degradation. Hence, weather change has become a serious problem in the study area. This is in line with (Abebe et al., Citation2019; Deribew & Dalacho, Citation2019; Foley et al., Citation2005; Palmate et al., Citation2017; Rahmato, Citation2009) finding show that deforestation may result in local climate changes following the negative response of deforestation to vegetation.

Key informants and focus group discussion participants confirmed that deforestation has become the most threatening factor in medicinal plants. The focus group discussion also adhered to the fact that, while plants play an important role in treating various human and livestock ailments, they are currently under pressure due to deforestation caused by resettlement in the study area’s resettled villages. Moreover, indigenous knowledge of the usage of medicinal plants as folk remedies is getting lost as the practice has been seized up with the disappearance of the species. Similarly, Annys et al. (Citation2016) and Abrha et al. (Citation2017) in their findings reported that habitats and species are being lost rapidly because of human disturbances through agricultural expansion and deforestation.

5. Conclusions

The resettlement program is condemned for having negative impacts on the ecosystem unless it is carried out carefully. The basic premises for a government-sponsored resettlement program are to secure food in the country. However, little attention was given to the spatial extent and rate of forest loss due to resettlement programs and their impact on the environment. Currently, what is observed in resettlement sites is that the program has precipitated some negative effects on the natural forest, soil resources, biodiversity species, and natural environments of the area.

Accordingly, the finding revealed that the satellite image analysis and participants in the household survey, key informant interview, and focus group discussions recognized the existence of massive forest loss in the resettlement area.

Forest cover change in the form of deforestation is a major environmental problem manifested in the Hawa-Galan district. The current study is a vivid example of how rapidly the forests are disappearing in the district. The situation in the study area shows that extensive resettlement sites of forest land have been completely deforested.

In line with this, the finding shows that recent resettlement programs drive massive forest loss (55% of the total area): hence, the government should intend to revise the program and should brand more preparation and efforts before implementing the policy. Moreover, identifying potentially suitable resettlement sites using scientific and technological tools may minimize the swift rate of deforestation in the destination site.

From the analyzed results, the magnitude of forest cover change was drastically changed between 2000 and 2018. Particularly, expansion of agricultural lands and settlement on one hand, and the decline of forest cover, shrubland/bushland, and wetland, on the other hand, were observed. Furthermore, the area of forest cover land has been reduced from time to time. As empirical findings indicated, the total area of the district, about 29,090.6 ha of land, was covered with forest in the first study period. But, this figure declined to 13,798.2 ha in the year 2018. On top of this, considering the annual rate of forest cover change between the former and latter study periods, the computed result indicated that about 4.14% of forest land is changed into other land use/ land cover annually.

Conversion of forest to other land uses, particularly to agricultural land and settlement at an annual average of 4.32% has been recorded. In light of this conversion, a high deforestation rate may resemble climate change. The forest loss we conducted and the climate data we collected show the likelihood of decreased precipitation in the study area. Therefore, priority should be given to carrying out replanting plants, and growing cash crop products: coffee, banana, timber, cocoa, and tea plantations. Likewise, acquainting and promoting biogas and solar energy off-farm activities to communities may reduce the potential climate change risk.

The study proves some resettlement sites are severely degraded. Hence, creating buffer analysis and benchmark mainly on Chiro Tulama and Mada Talila sites using participatory decision making and strong law enforcement may restore the loss of native vegetation.

The socio-economic analysis reveals that the large family sizes and illiterate societies are found to be among the most households who engaged in forest loss. Therefore, working on integrating family planning with non-governmental organizations and expanding education sectors on the resettlement based on clusters may improve the family status and attention of societies to forest management.

As a result, the problem of forest degradation as well as deforestation with other related factors have aggravated land degradation with soil erosion and deterioration of biodiversity in the district. Finally, it is concluded that time-series satellite image and socioeconomic data analysis reveal spontaneous/planned resettlement programs in the forest priority areas like the Hawa-Galan district are bad for forest resources. As a result, satellite imagery and household surveys can assist concerned parties in protecting the remaining forest resources from destruction.

Author’s contribution

TY has designed the study and collected data. TY carried out the fieldwork. KTD and GD analyzed and interpreted the overall document of the manuscript. KTD analyzed the remote sensing analysis and edited the manuscript. KG, GA, and SH have contributed to read the manuscript, reviewing and editorial work.

Availability of the data and materials

The data is included in the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We agreed to submit the original manuscript for Cogent Social Science and approved the original manuscript for submission.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Hawa-Galan district resettled and native communities for their genuine collaboration and valuable time to provide their views. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers and editor in the Journal of Cogent Social Sciences-Taylor and Francis Group for their priceless and constructive comments. Finally, we are grateful to the USGS’s Earth Explorer for providing free access to Landsat imagery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Teferi Yadeta

The authors’ main research focus is on forest management, land-use change modeling, environmental modeling, eco-tourism, vulnerability assessment, and terrestrial ecosystem service sustainability areas. We also engaged in different natural resource management projects and research activities at the national level when we were called upon to do so, and served as reviewers for different eminent and reputable journals voluntarily. In this regard, Kiros Deribew (Assistant Professor) has won the Excellent Reviewer Award in 2019 from Springer Open. Currently, we are working as lecturers, examiners, advisors, and researchers in public universities (refer to the affiliations).

References

- Abebe, M. S., Deribew, K. T., & Gemeda, D. O. (2019). Exploiting temporal-spatial patterns of informal settlements using GIS and remote sensing technique: A case study of Jimma city, Southwestern Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research, 8(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-019-0133-5

- Abera, A., Yirgu, T., & Uncha, A. (2020). Impact of resettlement scheme on vegetation cover and its implications on conservation in Chewaka district of Ethiopia. Journal of Environmental Systems Research, 9(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-020-00164-7

- Abrha, A. M., Nigus, H. K., Weldetensae, G. B., Tilahun, M., Nigusse, A. G., & Deribew, K. T. (2017). Effects of human disturbances on two sympatric francolin species in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Podoces, 12(1), 13–22.

- Annys, S., Demissie, B., Abraha, A. Z., Jacob, M., & Nyssen, J. (2016). Land cover changes as impacted by Spatio-temporal rainfall variability along the Ethiopian Rift Valley escarpment. Reg Environ Change, 17(2), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100113-016-1031-2

- Assefa, E., & Bork, H-R. (2013). Deforestation and Forest Management in Southern Ethiopia: Investigations in the Chencha and Arbaminch Areas. Environmental Management, 53, 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-013-0182-x

- Belay, K (2004). Resettlement of peasants in Ethiopia. Journal Of Rural Development 27 (2), 223–253.

- Belay, K. (2004). Resettlement of peasants in Ethiopia. Journal of Rural Development, 27(2), 223–253.

- Boillat, S. , Stich, C., Bastide, J., Epprecht, M., Thongmanivong, S., & Heinimann, A. (2015). Do relocated village experience more forest cover change? Resettlements, Shifting cultivation and forests in the Laos. PDR. Environment, 2 (2) , 250–279. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2020250

- Brink, A. B., & Eva, H. D. (2009). Monitoring 25 years of land cover change dynamics in Africa. a sample based remote sensing approach. Applied Geography, 29(4), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2008.10.004

- Central Statistical Authority (CSA). (2013). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Wereda level from 2007-2015. Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa.

- Chander, G., Markham, B. L., & Hedler, D. L. (2009). Summary of current radiometric calibrations coefficient for Landsat MSS, TM, ETM+ and EO-1 ALI sensors. Remote Sensing of the Environment, 113(5), 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2009.01.007

- Clarke, J. (1986). Resettlement and Rehabilitation: Ethiopia’s Campaign against Famine. Harney & Jones Ltd.

- Creswell, J. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating qualitative and quantitative research. 2nd.ed. Merrill Prentice-Hall.

- Deribew, K. T., & Dalacho, D. W. (2019). Land use and forest cover dynamics in Northeastern Addis Ababa, central highlands of Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research, 8(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-019-0137-1

- Deribew, K. T. (2019). Spatially explicit statistical modeling of random and systematic land cover transitions in Nech Sar National park. Ecological Processes, 8(46), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-019-0199-z

- Deribew, K. T. (2020). Spatiotemporal analysis of urban growth on forest and agricultural land using geospatial techniques and Shannon entropy method in the satellite town of Ethiopia, the western fringe of Addis Ababa city. Ecological Processes, 9(46), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00248-3

- Fisher, C. W., & Colson, E. (1973). Social consequences of resettlement. International Migration Review, 6(4), 471. https:doi.org/10.2307/3002846

- Foley, R., Caglar, M., & Teeter, L. R. (2005). Global consequences of land uses. Sciences, 309(5734), 570–574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111772

- Food and Agricultural Organiation of the United Nations (FAO 2010) Global Forest Resource assessment.Forestry Paper 147.Italy.

- Gebre, Y. (2002). Differential reestablishment of voluntary and involuntary migrants: The case of Metekel settlers in Ethiopia. African Study Monographs, 23(1), 31–46.

- Getachew, W. (1989). The consequences of resettlement in Ethiopia. African Affairs, 88(352), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098187

- Getahun, K., Poesen, J., & Rompaey, A. V. (2017). Impacts of Resettlement Programs on Deforestation of Moist Evergreen Afromontane Forests in Southwest Ethiopia. Mountain Research and Development, 37(4), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-15-00034.1

- Hammond, L. (2008). Strategies of invisibilization: How Ethiopia’s resettlement program hides the poorest of the poor. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(4), 519–536 https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen041.

- Kimutai, D. K., & Watanabe, T. (2016). Forest-Cover change and participatory forest management of the Lambus forest, Kenya. Environments, 3(20), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments3030020

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques (2nd ed.). New Age International Publishers.

- Li, C., Li, S. Z., Feldman, M. W., Li, J., Zheng, H., & Daily, G. C. (2017). The impact on rural livelihoods and ecosystem services of major relocation and settlement programs: A case study Shaanxi, China. Ambio A Journal of Human Environment, 47(2), 245–259 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0941-7.

- Limenih, M., Habetemariam, K., Kassie, G. T., Abebaw, D., & Teka, W. (2012). Resettlement and woodland management problems and options: A case study from northwestern Ethiopia. Land Degradation & Development, 25(4), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2136

- Liu, W., Xu, J., & Li, J. (2018). The influence of poverty alleviation resettlement on rural households livelihood vulnerability in the western mountainous area, China. Sustainability, 10(8) ,1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082793).

- Liu, W., Xu, J., Li, J., & Li, S. (2019). Rural households’ poverty and relocation and settlements: Evidence from Western China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(2609), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142609

- Messay, M. T. (2009). Challenges and opportunities of voluntary resettlement schemes in Ethiopia: A case from Jiru Gamachu resettlement village, Nonno District, Central Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 11(3), 83–102.

- Messay, M., & Woldesemait, B. (2011). The impact of resettlement schemes on land-use/land-cover changes in Ethiopia: A case study from Nonno Resettlement sites, central Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13(2), 269–293.

- Miyamoto, M., Parid, M. M., Aini, Z. N., & Michinaka, T. (2014). Proximate and underlying causes of forest cover change in Peninsular Malaysia. Forest Policy and Economics, 44, 18–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2014.05.007

- Mulugeta, M. T. (2009). Challenges and opportunities of voluntary resettlement schemes in Ethiopia: A case from Jiru Gamachu resettlement village, Nonno District, Central Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 11(3), 83–102.

- Mulugeta, M., & Woldesemait, B. (2011). The impact of resettlement schemes on land-use/land-cover changes in Ethiopia: A case study from Nono resettlement sites, Central Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13(2), 1520–5509.

- Nick, B., Jianhua, L., Jr, M., & John, S. (2014). Analysis on the causes of deforestation and forest degradation in Liberia: Application of the DPSIR Framework. Res. J. Agriculture and Forestry Sci, 2(3), 20–30 http://www.isca.in, http://www.isca.me.

- Oyinloye, M. A., Ogunlade, S. O., & Owoeye, J. O. (2018). Geo-spatial analysis of informal settlements on land use/cover change areas of Osogbo, Nigeria. American Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development, 3(3), 55–70.

- Palmate, S. S., Pandey, A., Kumar, D., Pandey, R. P., & Mishra, S. K. (2017). Climate change impact on forest cover and vegetation in Betwa Basin, India. Appl. Water Sci, 7(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-014-0222-6

- Pankhurst, A. (1990). Resettlement: Policy and practice.In. In S. Pausewang, C. Fantu, S. Brune, & E. C (Eds.), Ethiopia: Rural Development Options (pp. 121–134). Zed Books.

- Pankhurst, A. (2009). Revising resettlement under two regimes in Ethiopia: The 2000s programme reviewed in the light of the 1980s experience. In Eastern Africa Series (pp. 301). University of Michigan, James Currey .

- Porter, A. (1986). Resettlement in Ethiopia. The Lancet, 1(8474), 217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90694-X

- Puyravaud, J. (2003). Standardizing the Classification of the annual rate of deforestation. Forest Ecology and Management, 177(1), 593–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00335-3

- Rahmato, D. (1988). Settlement and Resettlement in Metekel, Western Ethiopia. Africa, 43(1), 14–34.

- Rahmato, D. (2009). The Peasant and the State: Studies in Agrarian Change in Ethiopia since 1950s-2000s. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa.

- Shchankina, L. N. (2019). Mordvins in Western Siberia in the Late 19th to Early 20th Century: Certain Issues in the Migration and Settlement. Journal of Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, 47(3), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.3.119-126

- Ssekandi, J., Mburu, J., Wasonga, O., Macopiyo, L., & Charles, F. (2017). Effects of Post Eviction Resettlement on Land-Use and Cover Change in Uganda’s Oil Exploration Areas. Journal of Environmental Protection, 8(10), 1144–1157. https://doi.org/10.4236/jep.2017.810072

- Tan, Y., Zuo, A., & Hugo, G. (2013). Environmental-related resettlement in China: A case study of the Ganzi Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Sichuan province. Asia Pac. Migr. J, 22(1), 77–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719681302200105

- Tejada, G. M., Dall-Nora, E., Cordoba, D., Lafortezza, R., Ovando, A., Assis, T., & Aguiar, A. P. (2013). Deforestation scenarios for the Bolivian lowlands. Conserv. Biol, 27(5), 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12079

- Vermote, E. F., & Saleous, N. Z. (2006). Operational Atmospheric Corrections of MODIS visible to middle infrared land surface data in the case of an infinite lambertian target Earth science Satellite Remote Sensing. In: Qu JJ, Gao W, Kafatos M, Murphy RE, Salomonson VV (eds) Earth Science Satellite Remote Sensing: Science and Instruments. Springer, Berlin. Science and Instrument, 123–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-37293-68

- Wayessa, G. O., & Nygren, A. (2016). Whose decisions, whose livelihood? Resettlement and Environmental justice in Ethiopia. Society & Natural Resources, 29(4), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1089612

- Wilmsen, B., & Wang, M. Y. (2015). Voluntary and involuntary resettlement in China: A false dichotomy? Dev. Prac, 25(5), 612–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1051947

- Woube, M. (1995). Southward-Northward Resettlement in Ethiopia. Northeast African Studies, 2(1), 85–106. https:doi.org/10.1353/nas.1995.0011

- Wubie, A. M. (2015). GIS and Remote Sensing based forest cover change detection for sustainable forest management in Bench Maji Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Remote Sensing and Geoscience, 4(3), 1–6.

- Yilak, D., & Debelo, D. G. (2019). Impacts of human resettlement on forests of Ethiopia: The case of Chamen-Didhessa Forest in Chewaka district, Ethiopia. Journal of Horticulture and Forestry, 11(4), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.5897/JHF2019.0583

- Yonas, B., Beyene, F., Negatu, L., & Angassa, A. (2013). Influence of resettlement on pastoral land use and local livelihoods in southwest Ethiopia. Trop Subtrop Agro-ecosyst, 16(1), 103–117.