Abstract

This qualitative study focused on employment barriers and opportunities faced by youths with albinism. Despite extensive legislation outlawing discrimination of persons with disabilities, persons with albinism continue to face employment challenges. The concept of othering informed the study. Forty-five participants were purposively sampled and interviewed using semi-structured interview guides. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Findings have revealed that biological constraints that characterise persons with albinism negatively impacts on their prospects of getting employed and staying in employment. Furthermore, discrimination against persons with albinism has led to their challenges in penetrating workplace social networks. To overcome employment challenges for persons with albinism, there is a need to capacitate them with adequate gadgets such as spectacles at a tender age. Other stakeholders such as the schools, the corporate world, parents and organisations representing persons with albinism have different roles to play in enhancing employment opportunities for persons with albinism.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Persons with albinism face employment challenges due to social discrimination and biological constraints. Their employment opportunities are further compromised by poor education which is a common feature among persons with albinism. Those who venture into self-help projects also suffer from discrimination and stigmatisation due to the uniqueness of their skin. To address employment challenges faced by persons with albinism, there is need for a multi-sectoral approach involving educators, employers, respective associations for persons with albinism and persons with albinism themselves.

1. Introduction

The proportion of persons with disabilities in the workplace remains subdued (Almalky, Citation2020; Bonaccio et al., Citation2020; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al., Citation2020; Mckinney & Swartz, Citation2021). This trend has not been different for persons with albinism in Africa (Bam & Ronnie, Citation2020; Ebuenyi et al., Citation2020; Etieyibo, Citation2020) and in Zimbabwe in particular (Choguya, Citation2021; Franklin et al., Citation2018a; Kasu, Citation2021; Mavindidze et al., Citation2021). Despite the existence of international, regional and national human rights instruments, persons with albinism continue to face employment-related challenges. Of importance in this study are the freedom from non-discrimination, right to safety and security, right to education and right to employment.

Research on persons with albinism has been conducted on different aspects, particularly focusing on specific challenges they face in different spaces. The challenges range from socio-cultural conceptions of albinism and sexuality challenges (Huang et al., Citation2020; Ikuomola, Citation2015; Tinkham, Citation2021), surgical challenges and outcomes of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in albinism (Sinha et al., Citation2016), challenges and opportunities in educating persons with albinism (Ndomondo, Citation2015; Tambala-Kaliati et al., Citation2021a), challenges and prospects for women and girls with albinism in sub-Saharan Africa (Masanja et al., Citation2020b; Ojilere & Saleh, Citation2019).

From a Zimbabwean perspective, studies on albinism have focused on the names of children born with albinism (Kadenge et al., Citation2014), myths and misconceptions around albinism (Baker et al., Citation2010), prevalence of persons with albinism (Lund & Roberts, Citation2018), challenges of children with albinism (Franklin et al., Citation2018a) and insecurities of women with albinism (Duri & Makama, Citation2018).

Although research on albinism has been wide, there seems to be a dearth of empirical research specifically on albinism and employment from a Southern African perspective, particularly Zimbabwe. The study therefore sought to examine barriers and opportunities to employment of persons with albinism in Zimbabwe with a view to advocating for inclusion in employment of this vulnerable group while tasking the relevant stakeholders on the need to structure employment policies and environments that accommodate persons with albinism.

The paucity of empirical work on employment and albinism in Africa limits the development of appropriate interventions to support, empower and, most importantly, protect them from unfair labour practices. This study proposes a conceptual model to act as a platform for research on which to build and enhance our understanding of employment challenges and opportunities for persons with albinism.

The study will be of importance to persons with albinism themselves as they thrive to get into the world of work as equals. Furthermore, captains of industry will have a lot to learn about issues around albinism that seem to put them at a disadvantage compared to those without albinism. Lastly, institutions and bodies that lobby for the rights of persons with albinism will have a lot to learn from this study as they will lobby and advise from a well-informed position.

The paper starts by outlining the concept of albinism as it occurs in different spaces before focusing on the theoretical framework underpinning the study. It proceeds to attend to the methodology which was used followed by findings and discussion. Conclusion and recommendations mark the end of the paper.

2. Albinism and experiences in different spaces

2.1. The anatomy of albinism and its prevalence in Africa

Albinism as a condition involves a group of inherited disorders of melanin synthesis, a pigment that protects the skin from ultraviolet light from the sun. People with albinism may lack pigmentation in the hair, eyes and skin, a condition known as oculocutaneous albinism (Sajid et al., Citation2021).

Oculocutaneous albinism has a potential of causing visual impairment resulting from hypopigmentation of the retina and iris, hypoplastic fovea, photophobia, hyperopia, strabismus, nystagmus and loss of stereoscopic perception (Eballé et al., Citation2013). Persons with albinism are prone to irreversible skin pathology such as skin cancer resulting from lack of melanin that protects the skins against ultraviolet (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Mouhari-Toure et al., Citation2021).

Oculocutaneous albinism is common among indigenous people in Africa. Wiete (Citation2011) notes that although the prevalence of albinism among humans is not clear, the ratio is estimated to be 1 in 17,000. In Africa, as presented by Phatoli et al. (Citation2015), the ratio stands at 1 in 5000. Due to its uniqueness, particularly within communities of people of an African origin, albinism as a condition is more noticeable in Africa than in light skinned populations (Hong et al., Citation2006). Due to its rarity, the condition has attracted some myths and misconceptions especially on the African continent as discussed in the next section.

2.2. Myths and misconceptions

Albinism has over the years been associated with some myths, misconceptions and misunderstandings (Kajiru & Nyimbi, Citation2020; Tambala-Kaliati et al., Citation2021a). Differences in skin creates socialization and adaptation challenges, leading to many myths and misconceptions surrounding the concept of albinism that have characterized the majority of African communities (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Ngubane, Citation2020; Thuku, Citation2011).

Evidence from Tanzania and Zimbabwe has shown that albinism is believed to bring good health, both financial and material wealths, cures HIV and AIDS as well as appeasing the gods of the mountain when a volcano starts erupting (Machoko, Citation2013; Roura et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, Bryceson et al. (Citation2010) established that bones of persons with albinism are used by miners in Tanzania as amulets or bury them where they are drilling for gold. The same study has also revealed that fishermen weave the hair of persons with albinism into their nets to increase their catch. Persons with albinism are also believed to be ghosts who cannot die, but rather, they disappear. This myth has led to the perception that persons with albinism are mysterious and dangerous beings (Braathen & Ingstad, Citation2006; Dapi et al., Citation2018a). Furthermore, Baker et al. (Citation2021) have it that it is assumed that the hair, genitals and bones of persons with albinism possess distinct powers. The authors went on to highlight that some parts of persons with albinism which are alleged to bring success are dried and ground. Thereafter, they are put into a package which is carried, to be concealed in boats, businesses, homes or clothing, or the package is scattered in the sea.

In South Africa, when a person with albinism gets into a taxi, people move to the opposite side or in some extreme cases, people may even refuse to use that taxi (Fazel, Citation2012). It is, however, important to note that persons with albinism, just like any other person, deserve to have their rights to life and security protected, as well as the right to be free from torture and ill-treatment (Dapi et al., Citation2018a).

Due to these myths and misunderstandings, persons with albinism, especially in Africa, have mostly experienced societal discrimination, stigmatization violations of human rights, as well as frustration due to rejection (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Tambala-Kaliati et al., Citation2021a). The ill-treatment has continued in Africa despite the United Nations Human Rights Council as well as the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted resolutions calling for the prevention of attacks and discrimination against persons with albinism (Dapi et al., Citation2018a).

2.3. Albinism and education

Despite the existence of various international treaties and pieces of legislation in different jurisdictions emphasising the rights of children to education, this has remained aspirational to vulnerable groups of children with disabilities, in this case, children with albinism (Adelakun & Ajayi, Citation2020b; Franklin et al., Citation2018a).

As noted by Adelakun and Ajayi (Citation2020b), although children with albinism have rights to education just like any other children, their rights are limited by difficulties usually experienced by both educators and parents in understanding the condition. Due to lack of facts on albinism both at school and at home, young persons with albinism seem to experience challenges associated with their physical appearance (Adelakun & Ajayi, Citation2020b).

It appears the skin of persons with albinism makes their lives difficult as most of them are ridiculed. Educators are not also exempted from this behavior of ridiculing persons with albinism. As argued by Tambala-Kaliati et al. (Citation2021a), most regular teachers may not realize the struggles encountered by a child with albinism. Due to the general lack of understanding of the condition, most regular teachers and school administrators struggle to accommodate children with albinism, hence the subsequent poor academic performance of the latter (Tambala-Kaliati et al., Citation2021a).

Myths and misconceptions surrounding albinism expose children with the condition to stigmatization, hence they usually feel more inferior to their peers at school. The position of persons with albinism is further worsened by their impeded academic progress due to poor vision, social adaptation and physical environment (Franklin et al., Citation2018a; Mubangizi & Kajiru, Citation2020).

2.4. Albinism and employment

Just like any other minority group, the number of persons with albinism in formal employment has remained suppressed. The under-representation of persons with albinism in formal employment has been attributed to perceived incompetence by prospective employers (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Masanja et al., Citation2020a; Uromi, Citation2014).

Uromi (Citation2014) also notes that persons with albinism are frequently shunned from employment by both governments and private employers due to their biological makeup as they are perceived as incapable or as being a burden to the organization employing them. In isolated cases when they are employed, they are assigned to carry out tasks that require them to work for long periods in the sun, thus exposing them to sun burns which may eventually cause skin cancer. Some of the working environments are not compatible with poor sight that characterizes persons with albinism (Uromi, Citation2014).

Without a proper education, most individuals with albinism do not aspire any form of formal employment. Instead, they opt to cultivate their own fields, working on the land of others as hired laborers or undertaking various manual jobs which expose them to the sun, despite the sensitivity of their skin (Dapi et al., Citation2018a).

Persons with albinism may also deliberately shun formal employment in an effort to circumvent discrimination and segregation which is rife in some formal organizations. They create their own jobs where they enjoy some level of independence and autonomy (Dapi et al., Citation2018a).

3. Theoretical framework

The study was premised on the classic work of Gayatri Spivak (Citation1980) which focused on the notion of othering. In this study, the definition of othering is adopted from (Crang, Citation2014, p. 61) who describes the terms as “a process through which identities are set up in an unequal relationship”. Othering is the simultaneous construction of the self or in-group and the other or out-group in mutual and unequal opposition through identification of some desirable characteristic that the self/in-group has and the other/out-group lacks and/or some undesirable characteristic that the other/out-group has and the self/in-group lacks.

Othering as a process therefore sets up a superior self or in-group that is cognitively constructed to an inferior other or out-group. The superiority/inferiority is, however, almost always left implicit (Brons, Citation2015). A perceived difference exists between the self or in-group and the other or the out-group. The differences are in most cases conceptualized through the construction of desirable and undesirable characteristics (Jensen, Citation2011). The concept of othering leads to the self-other distancing themselves and dehumanizing the other. A platform is set for a superior self or in-group that is different from inferior other or out-group (Visel, Citation1988).

Within the context of this study, the self/in-group would be people who do not have albinism whilst persons with albinism constitute the other/out-group. Undesirable characteristics of albinism differentiate those with the condition from those who do not have it, with the former being dehumanized and kept at arm’s length by those who do have the condition. We argue that othering is prevalent between persons with albinism and those who do not have the condition, with the former being perceived as inferior to the latter. We submit to the aspect that othering disadvantages persons with albinism within educational and employment spaces.

4. Methodology

Due to the subjective experiences of persons with albinism in as far as employment challenges and opportunities are concerned, the study adopted an interpretivist paradigm. Packard (Citation2017) acknowledges the existence of multiple realities which is a fundamental tenet of the interpretivism paradigm. Another important characteristic of this paradigm is its direct effort to understand the world of human experience (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Iofrida et al., Citation2018; Packard, Citation2017). These characteristics directly tally with the study’s purpose of unravelling and understanding the dynamics surrounding albinism and employment in Zimbabwe from the persons with albinism themselves according to their own personal experiences.

The study adopted a qualitative approach due to its unique characteristics which spoke to the objectives of this study. Qualitative research considers the insider perspective (Mouton & Babbie, Citation2001b). In this case, persons with albinism were insiders together with some key informants whilst researchers maintained the outsider position. In simpler words, the researchers would learn of the trends and experiences of albinism and employment from the insiders. Meanings of action in a social context form the center of qualitative studies (Coolican, Citation2017b; Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Matthews & Ross, Citation2014; Walliman, Citation2017); thus, behaviours of persons with albinism cannot be detached from their environment, perceived or real. Therefore, it is important to have an in-depth understanding of the meaning of these behaviours within a specific context. In relation to this, researchers as noted by Coolican (Citation2017b) and Iofrida et al. (Citation2018) are interested in people, their experiences and perceptions of the world around them. The study seeks to understand the dynamics surrounding albinism and employment within their context and how they interpret and perceive both the environment and their subsequent behaviors. Persons with albinism had to tell the story from their perspective.

Forty-five participants were purposively sampled and interviewed using semi-structured interview guides. The interviews were conducted in Harare and the surrounding peri-urban areas in the months of September and October 2020. Of the 45, 39 were persons with albinism. depict the biographical characteristics of persons who took part in the study. shows the sex and ages of participants with albinism.

Table 1. Age range and sex of participants with albinism

Table 2. Geographical settings and sex of participants with albinism

Table 3. Employment status and sex of participants with albinism

Table 4. Educational qualifications and sex of participants with albinism

As shown in , most participants with albinism were drawn from the urban setting, whilst a few were from the peri urban. The table also reveals the gender-related dynamics in the different geographical settings.

Participants with albinism as outlined in were of different employment statuses.

The educational qualifications of persons with albinism who participated in the study are depicted in .

According to a Zimbabwe Albino Association 2018 pamphlet, Harare and its surrounding areas have an estimated 4000 persons with albinism (ZIMAS, Citation2018). The sample of persons with albinism who participated in the study constituted nearly 1% of the total population. It is, however, important to note that by nature, qualitative studies are not interested in generalising findings to a wider population, hence there is no need to have a representative sample (Babbie & Mouton, Citation2010; Coolican, Citation2017a; Mouton & Babbie, Citation2001a). In the same context, Dworkin (Citation2012) argues that in qualitative studies, the ideal number of participants ranges between 5 and 50.

Furthermore, six of the participants were key informants, namely a human resource consultant, an educationist, an ophthalmologist and three people drawn from organizations representing persons with albinism.

Data were analysed using thematic analysis (TA; Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). TA was guided by the process of open, axial and selective coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). TA involves systematically identifying, organising and offering insight into patterns of meaning in a data set (Braun et al., Citation2019). Analysis of data commenced with a detailed reading and re-reading of the transcribed interview scripts read in conjunction with brief notes noted down during interview sessions. This was meant to deal with the aspect of critical distance. Researchers played numerous roles in the research process, particularly, the roles of designer and evaluator. Continuously interacting with data maintained critical distance. During the reading of each interview script, notes were made on the margins of the transcriptions so as to identify and describe discourses in the text.

Basing on the work of Braun et al. (Citation2019) and Nowell et al. (Citation2017), researchers began with a few predetermined codes and themes which were derived from the objectives of the study and the existing literature. Through continuous interaction with data, more codes, themes and sub-themes emerged. The codes, themes and sub-themes were loaded into Atlas TI version 8, a qualitative data analysis software which was used to aid in the analysis of data.

5. Findings and discussion

As earlier on alluded to, data were analysed using thematic analysis. This section focuses on findings and the associated discussion as they relate to the objectives of the study as well as the existing body of knowledge. As noted by Bloomberg and Volpe (Citation2018), researchers may combine findings and discussion of data. The section starts with a focus on biological constraints that impact on the prospects of persons with albinism to get employed. The section continues to investigate reasons which facilitate or hinder persons with albinism to join existing social systems within employment circles before concluding by proffering possible ways of enhancing employment opportunities for persons with albinism.

5.1. Biological constraints and employment

The study has established a number of biological constraints that impact on the employability of persons with albinism. The constraints are cancer-induced skin damages, inability to focus visually, poor eyesight, skin sensitivity to chemicals, skin sensitivity to the sun and general uniqueness. It is important to note that the impact of these constraints on an individual relates more closely to the nature of the work one engages in.

Seventy-one per cent of the participants argued that employment of persons with albinism is affected by some damages to their skin resulting from skin cancer. In line with the existing body of knowledge (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Ngubane, Citation2020; Schwering et al., Citation2015; Tambala-Kaliati et al., Citation2021a), the damages include wounds, scars and some other forms of marks brought about by skin cancer. Employers, as reported by most participants, are usually reluctant to employ persons with albinism with visible cancer-related marks on their skin. This behaviour by some employers confirms the notion of othering (Brons, Citation2015; Jensen, Citation2011), where in this case, those who do not have albinism and have no cancer-induced skin damages view themselves as the in-group with those persons with albinism whose skin has been affected by the sun are seen as members of the out-group. This leads to, as argued by Dapi et al. (Citation2018a) and Baker et al. (Citation2010), discrimination. One participant, a 33-year-old male with albinism, had this to say;

I had my ear removed due to skin cancer. I have some scars on my skin due to excessive exposure I experienced whilst I was growing up. The moment you get to a prospective employer, they usually react negatively. Employing someone who does not have an ear and with these marks on their skin? They will hesitate

A human resource consultant who participated as a key informant argued that some employers are just afraid of persons with albinism, especially considering the myths and misconceptions surrounding the condition as highlighted in previous studies (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Thuku, Citation2011). The fears are further exacerbated by visible marks and wounds. The key informant further argued that discrimination of persons with albinism with visible cancer-related marks is more rampant in the food and beverage industry, especially those whose work involves direct interaction with customers. Inadequate knowledge about the condition has been cited as one of the reasons why some employers are reluctant to employ persons with albinism. The consultant, however, was quick to point out that the myths and misconceptions are continuously being challenged, arguing that there has been a steady increase in the number of persons with albinism being employed in formal employment.

It has also emerged that damages to the skin affected persons with albinism who were self-employed, mostly vendors. Customers, the study has revealed, frequently shun buying from these people, especially those selling food stuffs, thus affecting the entrepreneurial efforts by persons with albinism. Unlike previous studies (Dapi et al., Citation2018a; Uromi, Citation2014) which focused on formal employment and discrimination of persons with albinism, this study has established that discrimination and othering also happen in informal employment, in this case, the in-group being composed of customers and persons with albinism as the out-group members.

In convergence with literature (Adelakun & Ajayi, Citation2020a; Eballé et al., Citation2013; Naipal & Rampersad, Citation2020), another biological constraint that affects employment opportunities of persons with albinism is the nature of their sight. All the participants highlighted that poor sight and difficulties in visual focusing hampered their chances of getting employed. Although vision and eye-related deficits associated with albinism were cited by all the participants as affecting employment chances, the effects were found to be more thorough in jobs that require robust and accurate sight such as those whose work involves use of a computer and money handling. Due to lack of eye pigmentation, the reflection of a computer screen makes it difficult for persons with albinism to both focus on a screen and see properly.

Given the increased use of ICT-related gadgets in organisations, persons with albinism are frequently found wanting in as far as employment opportunities are concerned. The position of persons with albinism is further complicated by the fact that most of them do not use vision enhancing gadgets due to the costs associated, either in renewing one’s lenses or acquiring a new set of spectacles. As noted by Jhetam and Mashige (Citation2020), these gadgets are instrumental in addressing some of the vision-related constraints associated with albinism. The study has also revealed that those who use vision-enhancing gadgets stand a better chance in employment circles than those who do not.

In a related argument, an ophthalmologist emphasized the need for persons with albinism to get adequate career guidance in choosing careers that correspond well with their eye-related challenges and limitations. He maintains that careers that require sharp and accurate vision are not ideal for persons with albinism as they end up straining their eye ligaments.

Eighty-two per cent of the participants revealed that persons with albinism have difficulties in securing employment due to the sensitive nature of their skin. Sensitivity has been cited from two fronts, namely, sensitivity to the sun and sensitivity to potentially harmful chemicals. Due to lack of pigmentation of their skin, persons with albinism are prone to sunburns. Being exposed to the sun during work exposes them to sunburns, thereby making them more vulnerable to skin cancer, thus as seen above, further compromising their chances of getting employed. Low levels of education which characterizes most persons with albinism as highlighted by Franklin et al. (Citation2018a) and Adelakun and Ajayi (Citation2020b) has seen the majority of them settling for outdoor jobs where exposure to the sun is rife. In line with the argument by Dapi et al. (Citation2018b), the situation is further complicated by an inability of most persons with albinism to acquire sunscreen lotions due to the cost as well as the poor economic condition currently prevailing in Zimbabwe. Under such circumstances, the study has revealed that some persons with albinism end up quitting their jobs or are forced by their employers to quit or are not even recruited right from the onset. From a human resource management expert, it has emerged that the high unemployment rate which has characterised Zimbabwe for more than two decades has left persons with albinism with no option but to work in any environment that may make them earn something, even though it exposes them to the sun.

Those whose qualifications or otherwise exposes them to chemicals have also lamented some employers’ reluctance to employ them on the basis of their skin being potentially sensitive to some chemicals. One pharmacist with albinism had this to say;

Before I eventually decided to be an academic, I tried my luck in a number of pharmaceutical firms, but most of them would say my skin could be sensitive to some of the chemicals used in the production of drugs. Fun enough in Algeria where I did my degree, I had my attachment in a pharmaceutical firm, where I worked well. Here, it could be more to do with stigmatisation than the sensitivity of my skin.

Given the health and safety obligations on the part of the employer, the potentially sensitive nature of the skin of persons with albinism should not be used against them, especially in this day and age where most operations are computerised. As argued by the above participant, one is forced to think that the move could be mere discrimination than factual. This could be another form of othering, though expressed in a more subtle manner.

An interviewed human resource consultant acknowledged the role played by skin sensitivity of persons with albinism in employment circles. She, however, argued that persons with albinism must go through tailor-made career guidance, especially around form three, a time they start specialising in career-specific subjects at school. She highlighted that ideally, persons with albinism must work in indoor environments where exposure to the sun is minimal.

This study has established that skin sensitivity to the sun and chemicals has not only affected those in formal employment or those willing to join the formal working environment but those plying their trade in the informal environment as well. The prevailing poor economic condition in Zimbabwe coupled with poor educational background has seen most persons with albinism engaging in informal trade in one form or another. The study has established that 78% percent of the participants were informal traders, with the majority of them being vendors. They reported doing their vending in the sun despite the sensitivity of their skin. Exposure to the sun has led to the majority of them developing some visible marks on their skin, especially considering the fact that most of them are not in a position to frequently access sunscreen lotions due to the prohibitive cost. Fourteen per cent of those who engaged in informal trade used some chemicals in their line of trade, with the potential to harm their sensitive skin. These included, among others, gold panning and shoe making and repairs.

Although Dapi et al. (Citation2018a) emphasised the damaging of skin of persons with albinism working in their fields, their study is silent on the potential harm to the skin due to informal work involving chemicals. Furthermore, unlike the position postulated by Dapi et al. (Citation2018a) where persons with albinism in Tanzania voluntarily engage in self-employment projects to avoid formal employment discrimination, most of the participants highlighted that they are in informal trade because of a poor economic performance coupled with their poor academic qualifications; otherwise, they were prepared to join formal employment.

The mere fact of physically looking different from the majority of people has seen some people with albinism failing to secure employment. This has been cited by 82% of the participants. Being observably unique combined with myths and misconceptions as stipulated by Dapi et al. (Citation2018a), Kajiru and Nyimbi (Citation2020), and Tambala-Kaliati et al. (Citation2021a) have been argued to be contributing to difficulties experienced by persons with albinism in as far as employment is concerned. The impact of the uniqueness is further negatively exacerbated by visible cancer-related marks on some of the persons with albinism due to lack of sunscreen lotions which are in most of the cases beyond the reach of the majority. These differences have led to the othering where persons with albinism are considered members of the out-group, while those who do not have considered themselves as in-group members. As ascertained by Anderson (Citation2021), othering leads dehumanization, discrimination and stigmatization.

Although in most cases, biological constraints work against persons with albinism in employment and in their quest to secure employment, unlike previous studies, this research has revealed that in some instances, albinism can also be instrumental in one securing employment or getting some unusual favors through direct or indirect affirmative action within employment circles. Eleven percent of the participants recalled moments when albinism worked to their advantage. One participant, a 34-year-old with albinism had this to say;

We were so many, and we had come to apply for a security officer job. I was singled out, possible because I had albinism. To make matters worse, I had three O’level [subjects] yet the minimum required was 5 O’levels [subjects], but still, they took me in and I am employed there as a security officer.

Commenting on persons with albinism and employment opportunities, a human resource consultant argued that it is high time corporates go beyond providing consumables such as sunscreen lotions and protective clothing but to give them employment as long as they qualify or almost qualify. Anecdotal evidence has shown that some corporate institutions usually engage in corporate social responsibility through providing sunscreen lotions and other consumables to persons with albinism. Although this is a noble gesture, a human resource consultant argued that it is more empowering to recruit persons with albinism into employment. By so doing, she argued, an organisation would be empowering the individual at the same time, demystifying the condition. highlights the biological limitations that impinge on the employment of persons with albinism.

Having focused on the biological limitations in this section, the next section addresses reasons that facilitate or hinder persons with albinism potential of interacting with others at work through participating in existing social systems.

5.2. Social settings and persons with albinism at the workplace

Organisations are social systems where social interactions are inevitable. The study, among other objectives, also sought to establish the extent to which persons with albinism are prepared to be part of these social systems in their respective working spaces. Sixty-six per cent highlighted that they took longer to be full participants of existing social groupings at their respective workstations, be it in informal or formal working arrangements. The main reason cited was the general stigmatisation of persons with albinism in social settings. As noted by a human resource consultant, the majority of persons with albinism have suffered segregation and discrimination, thus affecting their prospects of interacting in social settings at work through a dented self-esteem. Overt biological differences mainly characterised by limitations have also emerged as limiting factors which act against the chances of persons with albinism joining social systems at their respective workplaces. These limitations have been argued to keep them as outgroup members compared to the rest of the organisations’ members, thus in line with the Tambala-Kaliati et al. (Citation2021b), confirming the existence of othering being practiced in the workplace. Another aspect which compromises persons with albinism’s propensity to interact in social occupational settings is the low educational status most of them have. Seventy-six per cent indicated that they did not do well in their ordinary level, forcing them not to proceed with their education. Findings converge with the assertion by Franklin et al. (Citation2018a), Adelakun and Ajayi (Citation2020d), and Tambala-Kaliati et al. (Citation2021a) who maintain that persons with albinism are academically disadvantaged, despite the existence of rights to education every individual should enjoy. The low academic status that characterises most persons with albinism has been highlighted to be one of the reasons why most of them shun being part of social groupings at work and maintain a distance from the rest of the members of an organisation. Although persons with albinism are frequently discriminated against in employment circles through the process of othering, it is important to note that they reinforce this process by also consciously or unconsciously withdrawing themselves from social systems due to low self-esteem (Aborisade Citation2021). This tendency can be addressed by deliberately initiating efforts to boost the self-esteem of persons with albinism which will enable them to penetrate existing social systems at their respective workplaces.

In agreement with the work of Dapi et al. (Citation2018a), 0.6% revealed that their negative life experiences have led them never to look for employment in formal environments. One participant, a 34-year-old male cobbler, had this to say;

I am sorry to tell you this, I have seen it all. I have been sidelined, I have been stigmatised, I have been left alone when I desperately needed company. These experiences have taught me one thing, never to look for formal employment. I have lost trust in these formal organisations, I no longer have an interest in joining them. I just have to do my own things.

Findings have confirmed the position of the majority of existing literature that persons with albinism have low self-esteem, especially in Africa (Aborisade Citation2021; Chinhanu et al., Citation2021; Taylor et al., Citation2019). It is, however, important to note that not all persons with albinism have low self-esteem and experience difficulties in joining social systems at their workplaces. Thirteen percent of participants who had done well academically and were professionals revealed that they had high self-esteem and had no problems penetrating social circles in employment circles. It is our submission that academic and professional breakthroughs are important ingredients in boosting one’s self-esteem even though they have albinism. Furthermore, as noted by Aborisade (Citation2021), continuous efforts by interested stakeholders to boost the self-esteem of persons with albinism in different countries, including Zimbabwe could be yielding some positive results.

Generally, persons with albinism have low levels of confidence and self-esteem owing to their differences from the rest, their natural limitations as well as the segregation and discrimination most of them have suffered at the hands of the society. These aspects have seen most of them maintaining their distance or taking long to join and be part of social groupings at work. However, academic and professional achievements have been seen to be important factors that can lead to an increase in confidence and self-esteem, thereby facilitating persons with albinism to comfortably join social groupings at their respective workplaces.

This section focused on the propensity of persons with albinism to penetrate social systems at their respective workstations. The following section looks into ways that can be adopted by different stakeholders to enhance employment for persons with albinism.

5.3. Enhancing chances of employment for persons with albinism

The preceding sections have revealed that persons with albinism have some biological limitations which in most cases work against their chances of getting employed. As also highlighted by Dapi et al. (Citation2018a), Tambala-Kaliati et al. (Citation2021a), and Masanja et al. (Citation2020a) as well as the findings of this study, the same constraints also diminish their chances of succeeding even in self-help projects and intrapreneurial initiatives. Except in a few cases, these limitations coupled with discrimination and stigmatisation of persons with albinism have undermined the prospects of people with albinism to penetrate social circles in employment environments. Compromised self-esteem and confidence in oneself have been the general consequences of both the natural limitations, stigmatisation and discrimination of persons with albinism. This section focused on potential steps that can be initiated to address challenges faced by persons with albinism with regard to employment in Zimbabwe. Issues to be discussed include provision of an enabling academic environment, career guidance, self-esteem enhancing programs and demystifying albinism to both employees and management.

An enabling academic environment encompasses a number of aspects. However, in this study, these are limited to the provision of appropriate materials such as low vision devices and large font textbooks as well teachers’ knowledge about albinism.

Provision of relevant materials such as spectacles and sunscreen lotions within the educational setting may go a long way in improving the grades of persons with albinism, thus making them more competitive in the job market. Low educational levels and grades were cited by 87% of the participants as one of the key reasons why persons with albinism encounter challenges in securing employment, especially formal employment. The findings of this study pertaining to the education of persons with albinism concur with the findings of previous researchers (Adelakun & Ajayi, Citation2020c; Franklin et al., Citation2018b). The majority of these indicated that sight-related challenges significantly contributed to their poor grades and failure to proceed with their education, thus, their difficulties in securing employment. Limited access to spectacles due to different reasons has emerged as one of the reasons why persons with albinism do not do well at school, subsequently compromising their employment opportunities. depicts the time persons with albinism were exposed to spectacles.

Table 5. Use of spectacles among persons with albinism

Schwering et al. (Citation2015) have it that corrective lenses are important in improving the vision of persons with albinism. Similar sentiments were also echoed by an ophthalmologist who took part in the study as a key informant who argued that the use of spectacles may significantly improve the grades of persons with albinism, thus enhancing their employment opportunities.

clearly shows that most persons with albinism are introduced to spectacles late, early for a short time only or never at all, thus compromising their education, a situation which negatively impacts on their employment prospects. Seventy-four percent of participants who participated as persons with albinism highlighted that their chances of getting employed might have been significantly enhanced had they accessed spectacles on time and consistently, thus potentially improving their academic performance. An educationist shared similar sentiments by arguing that poor eyesight remains a major constraint in the education of persons with albinism, an aspect that can be addressed by exposing one to spectacles on time, according to him, around the third grade. The study has also established that the cost of acquiring spectacles was beyond the reach of the majority of persons with albinism as most of them come from low-income families. Another hindrance to the acquisition of spectacles cited in the study was the poor economic performance of the country, thus pushing the cost beyond the majority of persons.

Within the same argument, an educationist highlighted that school administrators, parents and persons with albinism themselves must be enlightened of the existence of such provisions as large font textbooks and additional time on exams of persons with low vision. These, however, do not necessarily replace the need for spectacles, particularly for better grades for persons with albinism. A human resource expert also highlighted that better grades and high academic achievements remain key for one to gain access into employment, thus calling for access to spectacles timely and consistently.

Although most participants with albinism cited failure to access spectacles due to reasons beyond their control, a few participants argued that they deliberately declined using spectacles. The main reason for declining using spectacles was the information they claim to have received from some eye specialists or some other specialists, arguing that the use of these gadgets would lead to a further deterioration of their eyes. Another cited reason was that some eye specialists told them that spectacles were of no use to persons with albinism. An ophthalmologist acknowledged the existence of these views among some eye experts. He, however, dismissed this school of thought arguing that spectacles improve both vision and clarity of objects for persons with albinism. According to him, the main reason why spectacles fail to work for some persons with albinism lies in poor diagnosis where wrong lenses are prescribed to an individual. These sentiments concur with the arguments presented by Schwering et al. (Citation2015) who has it that spectacles improve the vision of persons with albinism.

On a similar note, provision of sunscreen lotion is important in protecting persons with albinism from potential skin damage and cancer. Provision of these basic necessities to persons with albinism will not only help to enhance their grades but will also boost their self-esteem and confidence as they will be in a position to academically compete equally with those who do not have albinism. Higher academic achievements improve employment chances even for persons with albinism.

Inadequate or complete lack of knowledge about albinism on the part of some school teachers has been cited as a major limiting factor in the education of children with albinism. Ninety per cent of persons with albinism who took part in the study revealed that they had at least a teacher who had problems understanding them at one point in time in their educational life. The findings are in line with the arguments by Tambala-Kaliati et al. (Citation2021a) and Franklin et al. (Citation2018a) who have it that some teachers lack understanding of albinism, thus potentially and unconsciously mistreating children with albinism, thereby resulting in poor grades. Similar narratives were also presented by an educationist who highlighted that in most teacher training curricula, albinism is not presented as a disability; where and when it is talked about, the information is very minimal.

In an effort to address this knowledge gap on the part of educators, there is a need for teacher-training institutions to incorporate albinism in their respective curricula with the full attention it deserves. It is also imperative for a teacher who has a child with albinism in his/her class to take it upon themselves to gather knowledge about the condition and treat the child accordingly. Improved knowledge on the part of educators may mean better grades on children with albinism, subsequently leading to better employment opportunities.

Although only 15% of persons with albinism indicated the need for tailor-made career guidance, this remedy was cited by all the key informants. It was argued that persons with albinism should be guided on careers to avoid as these may cause significant challenges in employment. Due to their biological limitations, almost all the key informants indicated that persons with albinism must avoid careers that overexpose then to the sun as well as careers that require robust eyesight and accurate readings. Existing literature is silent about this intervention strategy to improve chances of employment among persons with albinism.

Another way of improving the employability of persons with albinism that emerged from the study is initiating self-esteem enhancement programs. Seventy-nine per cent of the participants highlighted having some self-esteem challenges or at least, once had such challenges in as far as employment and related aspects are concerned. All the key informants concurred that addressing the self-esteem of persons with albinism would go a long way in making them penetrate the employment challenges most of them seem to face. An educationist postulated that self-esteem programs should start during schooling years to challenge the possible negative impact of stigmatisation and discrimination suffered by most persons with albinism. Key informants from organisations dealing with persons with albinism also insisted that self-esteem efforts be made across the board, thus at home, school and even in the workplace. Also, of interest were the sentiments by a human resource expert who argued that most persons with albinism have accepted the negative label from the society and this has affected their performance even at work. She highlighted that some do not even bother to apply for employment simply because they have albinism. Findings about the need to address the self-esteem of persons with albinism resonate very well with other scholars, although their focus was not necessarily on employment issues (Lund, Citation2005; Taylor et al., Citation2019).

Seventy-nine percent of participants with albinism concurred that there is need for the main stakeholders in employment (management and other employees) to acquire adequate knowledge about albinism. Such knowledge will help to reduce or completely eradicate discrimination and segregation that usually emanates from myths and misconceptions surrounding the condition of albinism which are carried from the mainstream society into the workplace community, thus disadvantaging persons with albinism. Knowledge and appreciation of albinism, particularly by management, is important when it comes to allocation of tasks to the former, considering their natural limitations such as short sightedness and sensitivity of their skin to the sun. In simpler terms, when these relevant stakeholders have adequate and correct information about albinism, persons with albinism may stand better chances of getting employed as well as having to work in environments that are in tandem with their biological constraints.

Within the same context, an interviewed human resource expert argued that corporates must move beyond giving aid in the form of sunscreen lotions and protective clothing and start employing persons with albinism who qualify for certain positions in their organisations. This gesture, he assumed, will address the employment imbalance tilting against persons with albinism.

Key informants whose organisations represent persons with albinism extended the argument that key stakeholders in employment circles must have adequate and correct knowledge about albinism as they maintained that the same knowledge must be given to the wider general society. The fact that the majority of persons with albinism are involved in self-help projects calls for the society who in this case are the clients or customers, suppliers, business partners among others to be well informed about the condition of albinism, thus eliminating potential discrimination and segregation through correcting myths and misconceptions surrounding the condition. In this context, othering can be addressed by disseminating the correct information about albinism.

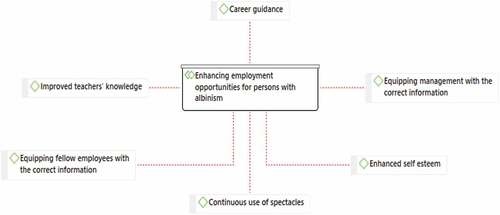

depicts possible actions that can be pursued in order to improve employment chances of persons with albinism.

As shown in this section, the study has established that employment opportunities for persons with albinism can be enhanced through a multiple-stakeholder approach where all those involved come together and pull in the same direction.

6. Conclusion

This section focuses on the extent to which the objectives of the study were met. The study was guided by three objectives. First, it was in the interest of the study to establish the perceived biological limitations of persons with albinism with regard to employment. Second, the study sought to ascertain the extent to which persons with albinism are likely to be part of existing social networks within employment circles and lastly, focus was on proffering possible solutions meant to enhance employment chances of persons with albinism.

The study has revealed that persons with albinism have some inherent biological limitations that in most cases affect their chances of employment. The constraints are mainly in the form of poor eyesight as well as skin sensitivity to the sun, with the latter usually leading to skin cancer and skin damage. Vision-related challenges have seen most persons with albinism failing to excel in their educational endeavors, subsequently leading to difficulties in securing employment, particularly in the formal sector. Furthermore, within the employment environment, the study has indicated that these biological constraints limit their chances of getting employed, especially in areas where accurate and strong sight is required. The same biological limitations have also been seen to affect some persons with albinism in informal employment. Biological limitations have led persons with albinism to look different from the rest of the people with pigmentation, and this has also frequently led to discrimination and segregation even within employment circles through a process called othering. However, in rare cases, the study has revealed that the existing inherent constraints of the condition can open employment opportunities as potential employers make efforts to promote the interests of previously marginalised groups such as persons with albinism. Furthermore, to the advantage of persons with albinism, some employers have exempted them from some tasks and environments which can potentially be harmful to their skin or which may make them strain their eyes.

Persons with albinism generally have challenges of penetrating social systems at work, the study has established. These challenges are mainly due to the stigmatisation and discrimination most of them have suffered in life. Biological constraints that characterise albinism as well as general poor academic achievement have also been argued to be contributing to low confidence and a sense of inferiority complex as they compare themselves with others. Inherent limitations combined with negative social experiences have generally led most persons with albinism to have low self-esteem, an element that has been found to work against their potential to penetrate social groupings at work.

The study has revealed ways through which employment of persons with albinism can be enhanced. Different stakeholders have different roles to play in a multi-sectoral approach. These include, parents, educators, management in corporates, fellow employees, organisations for persons with albinism, the general society at large as well as persons with albinism themselves.

7. Recommendations

Various recommendations for various stakeholders have been proffered in this study. Recommendations are divided into two categories, namely, recommendations for relevant stakeholders and recommendations for future studies.

7.1. Recommendations for relevant stakeholders

Relevant stakeholders in the employment of persons with albinism include potential employers, current employers, parents, educators or school administrators, organisations for persons with albinism as well as persons with albinism themselves. Each of these categories is recommended to consider the plight of persons with albinism in an effort to enhance their chances of getting employed.

Potential employers, current employers and the entire business community must make conscious efforts to understand the dynamics of albinism. This knowledge is instrumental in enabling them to make sound decisions ranging from recruitment and allocation of tasks when dealing with persons with albinism. One way of achieving this could be the engagement of organisations of persons with albinism. These organisations are strategically positioned to help corporates comprehend the uniqueness of this condition. On another note, recruitment of qualifying persons with albinism will help in demystifying myths and misconceptions surrounding the condition at the same time, addressing some historical imbalances which have seen persons with albinism being marginalised in employment circles. Affirmative action similar to that applied to minorities in some other sectors such as tertiary education may also be extended to the employment sector. This will see persons with albinism who, although falling short of the exact requirements, their qualifications approximate the expected level to a greater extent of getting employed.

Educators and school administrators have a unique role to play in improving the employability of persons with albinism. An enabling school environment and infrastructure together with a well-informed workforce about albinism will necessitate improved grades for persons with albinism, thus making them more employable. Through the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education or through their own initiatives, schools may regularly organise themselves and invite personnel from organisations representing persons with albinism for seminars concerning albinism. Educators, for instance, will have a good appreciation of the need for persons with albinism to sit as close to the chalkboard as possible as well as encouraging them to pursue in-house sporting activities that do not over-expose them to the sun. It will also be easy for school administrators to commit funds to aspects such as large print textbooks when they understand the anatomy of the eyes of persons with albinism. Adequate and correct information pertaining to albinism by educators and school administrators may go a long way in improving the plight and grades of persons with albinism, thus, positively impacting on their chances of getting employed.

Parents, corporate organisations, educators and organisations of persons with albinism all have a role to play in enhancing employment opportunities for persons with albinism. Most persons with albinism have been found to have low self-esteem and suffer from an inferiority complex mainly due to the myths and misconceptions surrounding the condition that lead to stigmatisation and discrimination. These stakeholders may formally or informally engage persons with albinism on a continuous basis to boost their self-esteem. Parents, as primary socialising agents, have a significant role to play in enhancing the self-esteem of their children with albinism. This can be achieved when, for example, parents accept their children with albinism, treat them fairly and stand up for them in times of stigmatisation and segregation by some outside forces. Parents can also continuously praise their children with albinism when they excel in whatever areas, at the same time, telling them that they look good and have all it takes to make it in life. Corporate organisations also have a role to play in enhancing the self-esteem of their employees with albinism. Accepting them as they are without judging them will go a long way in uplifting the self-esteem of persons with albinism. Managers may also assign persons with albinism duties that tally well with their physical constraints. Funds permitting, organisations may also send their employees with albinism for self-esteem coaching, having in mind the discrimination the majority of them have suffered in their previous years. Educators also have a role in addressing issues to do with the self-esteem of persons with albinism. Within the school setup, responsible authorities must make sure the condition is explained in full to learners who do not have albinism so that they appreciate their colleagues with albinism, instead of discriminating against them. Educators may also frequently conduct one-on-one sessions with learners with albinism in efforts to boost their self-esteem, telling them how good they are at the same time, encouraging them to speak out whenever they feel their rights are being tampered with in or outside the school premises. An enhanced self-esteem may be instrumental in making persons with albinism do well at school, apply for possible jobs in the market and compete with all the others on an equal platform.

It is also important for relevant personnel in different ministries and government departments to have correct and adequate knowledge about albinism. For instance, it is important to have a full topic or chapter about albinism for teachers under training. Albinism as a condition is unique and it is important for every teacher in the making to understand this condition before qualifying as professional teachers. Such knowledge will translate into better grades for persons with albinism, hence, better chances of getting employed. Furthermore, during training health professionals such as doctors and nurses must have a chapter, specifically on albinism. Soon after the birth of a child with albinism, these health professionals should immediately counsel the parents on how to deal with the condition, what it is and what it is not. This will help in demystifying myths and misconceptions that usually lead to abuse of persons with albinism at family level, usually leading to low self-esteem, poor academic grades and damaged skin, all of these combining to cause employment challenges for persons with albinism.

7.2. Recommendations for future researchers

Although this study may be referred to by future researchers, the following recommendations may be taken into consideration in an effort to fully understand the dynamics surrounding employment of persons with albinism in Zimbabwe.

For a robust appreciation of the perceptions and attitudes of fellow employees, management and captains of industry towards persons with albinism, future studies may benefit by fully engaging these relevant stakeholders. Such knowledge will be important for intervention strategies at the level of organisations in as far as employment of persons with albinism is concerned.

Future research may also benefit from an in-depth understanding of perceptions of children with albinism towards employment, particularly those doing their secondary school. Wrong perceptions towards employment may be addressed on time, while positive perceptions are strengthened. It is assumed that by the time they reach the right age for employment, correct attitudes and perceptions would have been cultivated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aborisade, R. A. (2021). “Why always me?”: Childhood experiences of family violence and prejudicial treatment against people living with albinism in Nigeria. Journal of Family Violence, 36(8), 1081–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00264-7

- Adelakun, O. S., & Ajayi, M.-A. O. (2020a). Eliminating discrimination and enhancing equality: A case for inclusive basic education rights of children with albinism in Africa. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 29(2), 244. https://doi.org/10.4103/NJM.NJM_50_20

- Adelakun, O. S., & Ajayi, M.-A. O. (2020b). Eliminating discrimination and enhancing equality: A case for inclusive basic education rights of children with albinism in Africa. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 29(2), 244. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njm/article/view/197544

- Adelakun, O. S., & Ajayi, M. A. O. (2020c). Eliminating discrimination and enhancing equality: A case for inclusive basic education rights of children with albinism in Africa. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 29(2), 244–251. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njm/article/view/197544

- Adelakun, O. S., & Ajayi, M.-A. O. (2020d). Eliminating discrimination and enhancing equality: A case for inclusive basic education rights of children with albinism in Africa. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 29(2), 244. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njm/article/view/197544

- Almalky, H. A. (2020). Employment outcomes for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 109(104656), 104656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104656

- Anderson, A. (2021). The role of culture in the (re) production of inequalities of acceptable risk exposure: A case study in Singapore. Health, Risk & Society, 24(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2021.2003306

- Babbie, E., & Mouton, J. (2010). The Practice of Social Research (10th ed.). Republic of South Africa, Oxford University Press Southern Africa, Cape Town.

- Baker, C., Lund, P., Nyathi, R., & Taylor, J. (2010). The myths surrounding people with albinism in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 22(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2010.491412

- Baker, C., Lund, P., Massah, B., & Mawerenga, J. (2021). We are human, just like you: Albinism in Malawi–Implications for security. Journal of Humanities, 29(1), 57–84. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jh/article/view/213454

- Bam, A., & Ronnie, L. (2020). Inclusion at the workplace: An exploratory study of people with disabilities in South Africa. International Journal of Disability Management, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1017/idm.2020.5

- Bloomberg, L. D., & Volpe, M. (2018). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A road map from beginning to end. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452226613

- Bonaccio, S., Connelly, C. E., Gellatly, I. R., Jetha, A., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2020). The participation of people with disabilities in the workplace across the employment cycle: Employer concerns and research evidence. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(2), 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9602-5

- Braathen, S. H., & Ingstad, B. (2006). Albinism in Malawi: Knowledge and beliefs from an African setting. Disability & Society, 21(6), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590600918081

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (pp. 1–18). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_103-1

- Brons, L. (2015). Othering, an analysis. Transcience. A Journal of Global Studies, 6(1), 69–90. https://philpapers.org/rec/BROOAA-4

- Bryceson, D. F., Jønsson, J. B., & Sherrington, R. (2010). Miners’ magic: Artisanal mining, the albino fetish and murder in Tanzania. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 48(3), 353–382. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X10000303

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Chinhanu, C. A., Chivandikwa, N., & Seda, O. (2021). I was never a white girl and i do not want to be a white girl’: Albinism, youth theatre and disability politics in contemporary Zimbabwe. In Theatre from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe (pp. 151–167). Springer.

- Choguya, N. Z. (2021). Double jeopardy: The intersection of disability and gender in Zimbabwe. In Social, educational, and cultural perspectives of disabilities in the global South. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-4867-7.ch003

- Coolican, H. (2017a). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Psychology Press.

- Coolican, H. (2017b). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Psychology Press.

- Crang, M. (2014). Cultural geographies of tourism. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism:, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118474648

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Dapi, L. N., Tambe, B. A., & Monebenimp, F. (2018a). Myths surrounding albinism and struggles of persons with albinism to achieve human rights in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 3(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-018-0048-5

- Dapi, L. N., Tambe, B. A., & Monebenimp, F. (2018b). Myths surrounding albinism and struggles of persons with albinism to achieve human rights in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 3(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-018-0048-5

- Duri, F. P. T., & Makama, A. (2018). Disabilities and human insecurities: Women and oculocutaneous albinism in post-colonial Zimbabwe. In M. Mawere & A. Nhemachena (Ed.), Rethinking securities in an emergent technoscientific new world order: Retracing the contours for. Africa’s hi-jacked futures, (1st ed., p. 77). Makon, Bamenda: Langaa Research & Publishing CIG.

- Dworkin, S. L. (2012). Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Springer.

- Eballé, A. O., Mvogo, C. E., Noche, C., Zoua, M. E. A., & Dohvoma, A. V. (2013). Refractive errors in Cameroonians diagnosed with complete oculocutaneous albinism. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 7(1), 1491. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S38194

- Ebuenyi, I. D., Rottenburg, E. S., Bunders-Aelen, J. F., & Regeer, B. J. (2020). Challenges of inclusion: A qualitative study exploring barriers and pathways to inclusion of persons with mental disabilities in technical and vocational education and training programmes in East Africa. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(4), 536–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1503729

- Etieyibo, E. (2020). Rights of persons with disabilities in Nigeria. Afrika Focus, 33(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.1163/2031356X-03301005

- Fazel, A. (2012). Albinos Blonely call for recognition. Mail & Guardian Health Supplement, 18–24. https://mg.co.za/article/2012-05-16-albinos-lonely-call-for-recognition/

- Franklin, A., Lund, P., Bradbury-Jones, C., & Taylor, J. (2018a). Children with albinism in African regions: Their rights to ‘being’and ‘doing’. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 18(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0144-8

- Franklin, A., Lund, P., Bradbury-Jones, C., & Taylor, J. (2018b). Children with albinism in African regions: Their rights to ‘being’and ‘doing’. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 18(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0144-8

- Hong, E. S., Zeeb, H., & Repacholi, M. H. (2006). Albinism in Africa as a public health issue. BMC Public Health, 6(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-212

- Huang, M.-Z., Chen, -L.-L., Hung, S.-L., & Puthussery, S. (2020). Women’s experiences of living with albinism in Taiwan and perspectives on reproductive decision making: A qualitative study. Disability & Society, 37(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1867071

- Ikuomola, A. D. (2015). Socio-cultural conception of albinism and sexuality challenges among persons with albinism (PWA) in South-West, Nigeria. AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities, 4(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v4i2.14

- Iofrida, N., De Luca, A. I., Strano, A., & Gulisano, G. (2018). Can social research paradigms justify the diversity of approaches to social life cycle assessment? The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 23(3), 464–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-016-1206-6

- Jensen, S. Q. (2011). Othering, identity formation and agency. Qualitative Studies, 2(2), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.7146/qs.v2i2.5510

- Jhetam, S., & Mashige, K. P. (2020). Effects of spectacles and telescopes on visual function in students with oculocutaneous albinism. African Health Sciences, 20(2), 758–767. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v20i2.28

- Kadenge, M., Mabugu, P. R., Chivero, E., & Chiwara, R. (2014). Anthroponyms of albinos among the Shona people of Zimbabwe. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(27 P3), 1230. https://www.mcser.org/journal/index.php/mjss/article/view/5202/5019

- Kajiru, I., & Nyimbi, I. (2020). The impact of myths, superstition and harmful cultural beliefs against albinism in Tanzania: A human rights perspective. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad, 23(1), 1–27. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/pelj/v23n1/41.pdf

- Kasu, S. (2021). Exploring pathways to work through skills development in sport for youth with intellectual disabilities in metropolitan Zimbabwe.

- Khayatzadeh-Mahani, A., Wittevrongel, K., Nicholas, D. B., & Zwicker, J. D. (2020). Prioritizing barriers and solutions to improve employment for persons with developmental disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(19), 2696–2706. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1570356

- Lund, P. (2005). Oculocutaneous albinism in Southern Africa: Population structure, health and genetic care. Annals of Human Biology, 32(2), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460500075423

- Lund, P. M., & Roberts, M. (2018). Prevalence and population genetics of albinism: Surveys in Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Tanzania. In Albinism in Africa. Elsevier.

- Machoko, C. G. (2013). Albinism: A life of ambiguity–a Zimbabwean experience. African Identities, 11(3), 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2013.838896

- Masanja, M. M., Imori, M. M., & Kaudunde, I. J. (2020a). Lifelong agony among people with albinism (PWA): Tales from lake zone in Tanzania. Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 3(2), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1991.03.02.172

- Masanja, M. M., Imori, M. M., & Kaudunde, I. J. (2020b). Factors associated with negative attitudes towards albinism and people with albinism: A case of households living with persons with albinism in lake zone, Tanzania. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8(4), 523–537. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.84038

- Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2014). Research methods. Pearson Higher Ed.

- Mavindidze, E., Van Niekerk, L., & Cloete, L. (2021). Inter-sectoral work practice in Zimbabwe: Professional competencies required by occupational therapists to facilitate work participation of persons with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(7), 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2019.1684557

- Mckinney, E. L., & Swartz, L. (2021). Employment integration barriers: Experiences of people with disabilities. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(10), 2298–2320. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579749

- Mouhari-Toure, A., Akakpo, S. A., Teclessou, J. N., Gnossike, P., Adam, S., Mahamadou, G., Kassang, P., Elegbede, Y., Darre, T., Kombate, K., Pitché, P., & Saka, B. (2021). Factors associated with skin cancers in people with albinism in Togo. Journal of Skin Cancer, 2021(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3433493

- Mouton, J., & Babbie, E. (2001a). The practice of social research. Cape Town: Wadsworth.

- Mouton, J., & Babbie, E. (2001b). The practice of social research. Cape Town: Wadsworth.

- Mubangizi, J. C., & Kajiru, I. Human rights education and the plight of vulnerable groups with specific reference to people with albinism in Tanzania. (2020). International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 20(2–3), 137–155. 1358229120948691. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229120948691

- Naipal, S., & Rampersad, N. Visual function and visual ability in adolescents with oculocutaneous albinism. (2020). British Journal of Visual Impairment, 38(2), 151–159. 0264619620973693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264619619892993

- Ndomondo, E. (2015). Educating children with albinism in Tanzanian regular secondary schools: Challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Education and Research, 3(6), 389–400.

- Ngubane, Z. L. (2020). An ethical analysis of the African traditional beliefs surrounding people living with albinism in South Africa.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Ojilere, A., & Saleh, M. M. (2019). Violation of dignity and life: Challenges and prospects for women and girls with albinism in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 4(3), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-018-0085-0

- Packard, M. D. (2017). Where did interpretivism go in the theory of entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 536–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.004

- Phatoli, R., Bila, N., & Ross, E. (2015). Being black in a white skin: Beliefs and stereotypes around albinism at a South African university. African Journal of Disability, 4(1), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v4i1.106

- Roura, M., Nsigaye, R., Nhandi, B., Wamoyi, J., Busza, J., Urassa, M., Todd, J., & Zaba, B. (2010). “Driving the devil away”: Qualitative insights into miraculous cures for AIDS in a rural Tanzanian ward. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 427. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-427

- Sajid, Z., Yousaf, S., Waryah, Y. M., Mughal, T. A., Kausar, T., Shahzad, M., Rao, A. R., Abbasi, A. A., Shaikh, R. S., Waryah, A. M., Riazuddin, S., & Ahmed, Z. M. (2021). Genetic causes of oculocutaneous albinism in Pakistani population. Genes, 12(4), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12040492

- Schwering, M. S., Kumar, N., Bohrmann, D., Msukwa, G., Kalua, K., Kayange, P., & Spitzer, M. (2015). Refractive errors, visual impairment, and the use of low-vision devices in albinism in Malawi. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 253(4), 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-015-2943-0

- Sinha, M., Chhablani, J., Shah, B., Narayanan, R., & Jalali, S. (2016). Surgical challenges and outcomes of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in albinism. Eye, 30(3), 422–425. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.245

- Spivak, G. C. (1980). Revolutions that yet have no model: Derrida‘s limited inc. Diacritics, 10(4), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/464864

- Tambala-Kaliati, T., Adomako, E. B., & Frimpong-Manso, K. (2021a). Living with albinism in an African community: Exploring the challenges of persons with albinism in Lilongwe District, Malawi. Heliyon, 7(5), e07034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07034

- Tambala-Kaliati, T., Adomako, E. B., & Frimpong-Manso, K. (2021b). Living with albinism in an African community: Exploring the challenges of persons with albinism in Lilongwe District, Malawi. Heliyon, 7(5), e07034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07034

- Taylor, J., Bradbury‐Jones, C., & Lund, P. (2019). Witchcraft-related abuse and murder of children with albinism in Sub-Saharan Africa: A conceptual review. Child Abuse Review, 28(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2549