?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the global tourism industry and forced the industry to reevaluate methods for improving tourism quality and opportunities to develop sustainable and ecofriendly tourism. This paper uses an online questionnaire survey to investigate whether tourists who visited Maokong Region(in Taipei) before and after the pandemic would be more appreciative of the value of urban eco-tourism and be willing to increase their willingness to pay (WTP). Since the value of eco-tourism cannot be measured by market goods, this paper develops a Contingent Valuation Method and tests it by Negative Binomial Regression. The empirical results confirmed that the pandemic substantially affected tourists’ psychological perceptions and increased their willingness to pay for the value of ecotourism. The factors affecting the willingness to pay include frequency of visit, willingness to revisit, length of stay, acceptance of ecotourism, and ecotourism preference. Ecotourism plans for Maokong were proposed to fulfill tourists’ desire to travel during the pandemic and to mitigate the impact of tourist behaviors on natural environments. This paper attempts to quantify how the pandemic caused changes in people’s psychological perceptions and reflect this in terms of willingness to pay. Also, it proposes urban eco-tourism programs appropriate to the period of the pandemic. The results of this study may serve as a reference for countries promoting short-term, short-distance, and outdoor urban ecotourism and thereby achieve ecological protection, and physical and psychological health maintenance during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are the innovations and contributions of this paper.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The COVID-19 outbreak has had a severe impact on people’s safety and psychological health and has changed the way people travel. The public prefers short-term, short-distance, outdoor nature-based tourism to maintain their physical and mental health during the epidemic and to satisfy their travel desires. This paper uses questionnaires and quantitative research to demonstrate that tourists are more aware of the value of urban eco-tourism due to the outbreak and are willing to increase their willingness to pay to support eco-tourism development. This paper further analyses the impact of frequency of travel, length of stay, and willingness to revisit on the willingness to pay and proposes a proposal for urban eco-tourism that can serve as a reference for countries to promote urban eco-tourism activities during the pandemic.

1. Introduction

By August, 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2019, had caused approximately 226 million infections and 4.68 million deaths. In addition to life safety, COVID-19 has threatened national economic development and affected individual behavior. Specifically, the pandemic has affected activity across countries (e.g., industrial, economic, cultural, and tourist exchanges); caused a rise in unemployment; led to changes in work, school, consumption, and transportation patterns; and undermined individuals’ psychological health (Beck & Hensher, Citation2020; Litvin & Smith, Citation2021; Ornell et al., Citation2020; De Vos, Citation2020).

According to a 2020 report by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the pandemic had led to a 74% decrease in the number of international tourists compared with that of the preceding year and had caused a loss in international tourism income of US$330 billion, which was significantly higher than the loss experienced in the Great Recession of 2009. The tourism industries in the countries of Asia and the Pacific region experienced the most severe decline, with tourist numbers decreasing by 84% compared with those of the preceding year (UNWTO, Citation2021b). In Taiwan, according to the Tourism Bureau, due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on international tourism, the number of international arrivals decreased by more than 80%, and the number of business closures in the tourism industry increased drastically compared with those of the same period in the preceding year (Tourism Bureau of Ministry of Transport, Citation2021). This highlights the challenges the pandemic has brought to domestic and international tourism.

Nevertheless, the pandemic has also provided an opportunity for the industry to reevaluate its approach to improve the quality of tourism and adjust conventional tourism models. According to UNWTO secretary general Pololikashvili, this pandemic has presented an opportunity for the industry to not only reconsider the manner through which tourism contributes to society and the Earth but also to establish a sustainable, inclusive, and resilient model for tourism (UNWTO, Citation2021a). Ecological tourism was proposed in the 1960s in response to the environmental damage caused by an increase in tourist activities and numbers; it was intended to reduce the negative effects of tourism on natural and cultural landscapes, preserve local cultures, and provide local communities with appropriate economic benefits and thereby attain resource sustainability and economic development (Miller, Citation2001). After ecotourism was proposed by the UNWTO at the World Tourism Convention in Manila in 1980, fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals became a major objective for the tourism industry.

In 2003, the SARS pandemic led to an increase in psychological health problems, including fear, anxiety, loneliness, anger, and severe mental disorder. The effects of the pandemic on psychological health were equivalent to those of a major disaster (Chua et al., Citation2004; Lee et al., Citation2007) with respect to instinctual reactions to uncertainties and risks. Using experience incurred through responding to the SARS and MERS pandemics, the health and sanitation units of each country have proposed strategies for mitigating the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which social distancing, home quarantine, and lockdowns have most notably affected behaviors and psychological health (Adalja et al., Citation2020; Asmundson & Taylor, Citation2020). Although the pandemic and related control measures have affected daily living and psychological adjustment, they have also prompted changes in behaviors and perceptions in the face of the uncertainty brought by the pandemic. People have begun to increase the amount of attention they give to their own psychological feelings, cherish opportunities to spend time with family and friends, appreciate everything they have, and cherish travel opportunities (Lee et al., Citation2007; Ornell et al., Citation2020).

To maintain their physical and psychological health and also fulfill their desire to travel amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, people have considerably changed their travel behaviors. For example, people generally plan excursions for locations near their homes, select family and friends as their travel companions, select ecological and open natural landscapes, and avoid public transportation or peak holiday travel periods (Troko et al., Citation2011; De Vos, Citation2020). In Taiwan, due to pandemic control measures and vaccination distribution, the tourism market rose drastically in spite of international travel restrictions. Counties and cities across Taiwan developed high-quality, in-depth tours focusing on ecotourism, cultural tourism, and pastoral experience to attract tourists. The Ministry of Transportation and Communications developed the Taiwan Sustainable Tourism Development Plan, which began with the 2017 “Year of Ecotourism” and expanded to the 2019 “Year of Small Town Ramble” and the 2020 “Year of Bicycle Touriing” (Tourism Bureau of Ministry of Transport, Citation2017). The goals of this plan, in addition to increasing local income through tourism, include improving tourism quality, establishing a sense of place identity among tourists and local residents, and providing Taiwanese people with opportunities to experience outdoor natural environments.

Ecotourism has become generally accepted by the public, and studies on the subject have reported that accessing natural environments does not necessarily require travel to remote, natural ecological areas. Many ecological environments that have not been disrupted exist in urban areas and are easily accessible by transportation systems (Chirgwin & Hughes, Citation1997). Because, at the time of this study, the COVID-19 pandemic has not yet subsided completely, urban tourism has become a part of urban life and has become a means of satisfying the need for tourism within the context of changing travel behaviors. The Maokong region in Taipei has benefited from the restrictions on hillside development so its rich ecological environment includes fauna, flora and unusual terrain features. Tea growing used to be a mainstay of Maokong (Wenshan District Office of Taipei City, Citation2002). To integrate the local specialty tea industry with the recreational tourism industry, Taipei City rezoned some of the preserves for recreational industry use. The government also encouraged the development of the local recreational tourism industry and provided counseling to tourism tea plantation managers. Recreational teahouses gradually became popular in the Maokong region and large numbers of tourists flooding into the area during public holidays. In 2020, the Ministry of Transportation and Communications selected the Maokong region as the “Taiwan Classic Town” to promote its eco-tourism and local characteristics (Tourism Bureau of Ministry of Transport, Citation2020).

In response to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the development of the tourism industry and tourists’ cognitive behaviors, urban ecotourism has been promoted as a means of recovering the industry, improving tourism quality, and enhancing the depth and breadth of tourism in coordination with changing trends in tourist behaviors during the pandemic. With reference to the findings of Liu (Citation2009)Footnote1 and from the perspectives of ecotourism, travel choice behavior, and the nonmarket values of ecotourism, this study explored whether tourists who traveled in the Maokong region during the pandemic experienced a change in their psychological perceptions and understanding of the value of urban ecotourism, which thus increased their willingness to pay (WTP) for the nonmarket value of ecotourism in Maokong.

This study explored the travel behaviors of the tourists in Maokong during the pandemic, their WTP for ecotourism (including use and conservation values), and the factors affecting WTP, and suggestions were accordingly proposed for the development of urban ecotourism in that region. The systematicity, innovation and contribution of this paper are described below ():

1.1. Studies on the correlation between pandemic outbreaks and tourism have mainly focused on the sudden decrease in tourism and changes in tourism patterns after a pandemic (Beck & Hensher, Citation2020; Troko et al., Citation2011; De Vos, Citation2020). Could changes in psychological factors, such as a greater appreciation of feelings and opportunities to travel during the pandemic (Lee et al., Citation2007; Ornell et al., Citation2020), increase people’s perception of the value of travel? Could this increase in the willingness to pay to reflect an increase in the value of tourism and serve as a reference for governments to promote sustainable, ecological, and short-distance tourism during the pandemic? No research has been conducted on these issues. This paper examines the changes in travel patterns, personal behavioral perceptions, and travel choice behavior in the pandemic context. Through an empirical study, this paper examines whether the pandemic outbreak has triggered a greater appreciation of the existing travel environment and increased their willingness to pay for eco-tourism. Quantitative figures are used to reflect the extent to which the “pandemic” factor influences the value of the tourism environment. This is the main difference between this paper and other studies and is one of the innovations and contributions of this paper.

1.2 This paper aims to understand the changes in the willingness to pay for eco-tourism in urban areas before and after the pandemic. Based on Liu’s (Citation2009) study, a questionnaire survey was conducted among tourists who visited the Maokong region before and after the pandemic. Comparing Liu’s (Citation2009) research findings, this study provided a more objective and realistic answer to the questionnaire on the pandemic’s impact on the willingness to pay. In addition to the COVID-19 factor, changes in travel cognitive behavior, such as frequency of travel, willingness to revisit, length of stay, and preference for travel content (Nvight, Citation1996; White & Lovett, Citation1999; Whitehead & Blomquist, Citation1991), were further tested as factors influencing willingness to pay. Based on the empirical findings, this study will propose a proposal to develop urban eco-tourism in the Maokong area. The use of different periods of tourism will help plan the development of the tourism industry during the pandemic. These are also the innovations and contributions of this paper.

1.3 The results of this study may provide a reference for tourists making travel decisions during the pandemic, increase the depth and breadth of ecotourism, and facilitate the development of local characteristics to enhance tourists’ and local residents’ identification with local areas. These developments may enable Maokong to serve as a reference for all countries developing short-term, short-distance, and outdoor urban ecotourism during the pandemic and to be featured as an ecotourism area for foreign tourists after the pandemic subsides and Taiwanese tourism is respond for foreign tourists.

The paper begins with the introduction before continuing to a review of urban ecotourism, travel choice behavior and non-market valuation, an introduction to the ecotourism resources of the Maokong region, research design and questionnaire survey, analysis of empirical results, and then finally recommendations based on the empirical findings.

2. Literature review

Before the pandemic, people could choose where, how, and when to travel. After the outbreak, governments took measures such as border closures, city closures, and travel controls to prevent the spread of the pandemic (Adalja et al., Citation2020). The public also changed their travel behavior to short-distance, short-term trips and preferred the outdoors for their safety (Beck & Hensher, Citation2020; Troko et al., Citation2011; De Vos, Citation2020). This paper considers the potential for eco-tourism in the urban suburbs to meet the demand for short-term, short-distance, and outdoor nature tourism during the pandemic. In Section 2.1, the characteristics of urban eco-tourism are introduced to support the value of the eco-tourism environment in the Maokong area during the pandemic. These include closer proximity to people’s living spaces, the diversity of natural and human tourism resources, accessibility to urban areas, and the ability to achieve environmental sustainability (Andari, Citation2019; Haghi & Heidarzadeh, Citation2021).

In order to understand the selection process and the influencing factors of tourism locations, the impact of the pandemic on tourism behavior can be further explored. Section 2.2 analyses the decision-making process of travel choices, including individual psychological and social factors (Bianchi et al., Citation2017; Han & Kim, Citation2010; Soliman, Citation2019). The occurrence of a pandemic affects psychological factors and subjective norms and whether this triggers tourists to identify with the urban eco-tourism environment and thus increase their willingness to pay. As the willingness to pay for eco-tourism cannot be measured by market values, the model will be tested through the 2.3 non-market value assessment method to obtain empirical findings. The review of literature in each section is analyzed as follows:

2.1. Urban ecotourism

Ecotourism is nature-oriented tourism based on the ideal of sustainable development. Local actors such as residents, tourists, tourism industry operators (e.g., government, businesses) and conservation groups all work together to provide an educational and enlightening tourism experience while respecting local community development. The goal is to balance the needs of recreational industry development and sustainable resource conservation (Aronsson, Citation1994). By participating in the development of ecotourism, increased employment opportunities, tourism revenues, better infrastructure and public facilities will help improve local residents’ economic circumstances and quality of life (Ross & Wall, Citation1999). The promotion of ecotourism can therefore protect natural resources, promote education, improve tourism quality, encourage local participation and boost income all at the same time. To realize these goals, a common compliance mechanism involving local residents, tourism operators and conservation groups must be established. Proper planning and management will reduce the bad impact on the ecological environment from tourism development (Ross & Wall, Citation1999).

Traditional ecotourism destinations tend to be more primitive, remote and undeveloped natural or cultural landscapes. More time must be spent on transport, thereby reducing the popularity of traditional ecotourism for the general public. Chirgwin and Hughes (Citation1997) felt that ecotourism should not be limited to primitive regions and there are many relatively unspoiled natural cultural landscapes near cities that are worth visiting. Lawton and Weaver (Citation2001) even included modified spaces as ecotourism destinations. While traditional ecotourism focused on natural regions, they felt that it was unreasonable to exclude modified spaces as ecotourism destinations. Developed urban areas can also be full of green spaces, so urban green land development and beltways can help boost the opportunities for sustainable urban tourism. The urban infrastructure and public facilities can also be harnessed to support the development of urban ecotourism (Gibson et al., Citation2003). Dodds and Joppe (Citation2001) analyzed Toronto’s experience with the development of urban tourism and confirmed the feasibility of urban ecotourism. At this point, a clear outline of urban ecotourism began to emerge.

Urban ecotourism is where urban development, guided by eco-conservation concepts, is used to find meaningful and low-impact tourism options. Tourists are encouraged to choose walking, bike paths and public transportation to explore the natural regions and experience the local cultural activities in the areas around the city in a low-carbon and energy-saving manner. The result is an educational and recreational tourism experience (Gibson et al., Citation2003). A certain level of man-made construction is also allowed for harmonizing the natural landscape. By developing tourism through appropriate construction, urban sprawl can be reduced and the natural ecology of the city protected (Gibson et al., Citation2003; Lawton & Weaver, Citation2001).

Mahboob et al. (Citation2021) used the example of Lahore, an urban eco-tourism destination in Pakistan. The factors influencing tourists’ choices of destination and willingness to pay were analyzed, including the destination’s specific human and natural landscape, satisfaction with previous travel experiences, the purpose of travel (family or friends, stress relief), and age. As for the analysis of the willingness to pay, since the study only used the age and income variables, the analysis results were based on income as an influencing factor of the willingness to pay. Visitors’ satisfaction with the urban eco-tourism destination also influenced their willingness to pay. Satisfaction measures include satisfaction with the unique natural or human environments of the destination, satisfaction with opportunities to interact with the local community, satisfaction with participation in local eco-activities, satisfaction with accessibility, satisfaction with the tourism programs, and satisfaction with cultural and historical characteristics (Simon et al., Citation2020; Yang, Citation2018). In addition, the more frequently tourists visit a destination, the more willing they are to revisit or the longer they stay, the more they like the destination and the more attractive it is to tourists, who are then willing to pay higher prices (Back et al., Citation2018; Bianchi et al., Citation2017; C.-F. Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Mahboob et al., Citation2021).

The above analysis clearly shows that urban eco-tourism is located in the urban areas, where natural ecological resources, human resources, urban green space, and local culture can all be included in urban eco-tourism. With easy access to transportation and close to people’s living spaces, the promotion of urban eco-tourism can satisfy people’s desire for outdoor activities during the pandemic and become part of their daily lives (Andari, Citation2019; Haghi & Heidarzadeh, Citation2021).Maokong has urban ecotourism potential due to its rich natural and cultural landscape such as fauna, flora, unusual terrain features, tea industry, famous temples and Maokong Gondola as well as its location on the outskirts of Taipei City.

This paper considers the above factors in influencing the willingness to pay and includes a questionnaire survey. In addition, the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) was used to analyze the factors affecting the willingness to pay for eco-tourism in the Maokong during the pandemic and the willingness to increase the willingness to pay. This study uses this method to verify the pandemic’s impact on the value of urban eco-tourism and make recommendations for tourism development during the pandemic.

2.2. Travel choice behavior

Travel choice behaviors in tourists are influenced by psychological (i.e., cognition and attitudes) and social (i.e., subjective norms) factors (Bianchi et al., Citation2017; Han & Kim, Citation2010; Soliman, Citation2019). Cognition refers to individuals’ recognition and understanding of external information through its internalization, compilation, and organization and the actions resulting from this understanding (Bower, Citation1975; Tanford & Montgomery, Citation2015). Because the information individuals receive is complex and cannot be comprehensively retained when reacting, individuals selectively take in portions of information through subjective, selective, and organized cognitive processes during decision-making. Therefore, cognition is substantially determined by the characteristics of the individual. Travel choices are influenced by tourists’ personal characteristics, such as their sex, age, education level, place of residence, knowledge of ecotourism, and feelings toward tourist destinations(Back et al., Citation2018; C.-F. Chen & Tsai, Citation2007).

Attitudes refer to individuals’ feelings toward or appraisals of people or things and are influenced by three subjective psychological factors (Ajzen, Citation1991), namely cognition, affection, and behavioral intention (Best et al., Citation2007). Affection refers to the individual’s emotional reaction toward a person or thing, such as a like or dislike. Affection, therefore, represents the effects of positive and negative experiences on the individual’s appraisal of objects or behaviors. Behavioral intentions are behavioral tendencies toward objects; they can be used to predict individuals’ behaviors and be appropriately measured in formulating tours (Baker & Crompton, Citation2000; Lutz, Citation1991). Within the context of tourist behaviors, behavioral intentions generally manifest as tourists’ willingness to revisit, participate, or pay, all of which indicate the value of a tourist destination to these tourists (Back et al., Citation2018; C.-F. Chen & Tsai, Citation2007). Best et al. (Citation2007) indicated that all the three factors cause changes in attitudes. Because behavioral intentions are easily observable, cognition and affection are generally predicted through behavioral intentions. Attitudes are dynamic and change with time and external environments. When an attitude is formed, it affects a tourist’s behavioral intentions, which are then reflected in the tourist’s tourism choices.

A subjective norm refers to the social support or pressure individuals perceive themselves to receive from socially valued individuals (e.g., family, friends, or groups) when performing an action (Ajzen, Citation1991). Although attitudes can determine behavioral intentions, subjective norms often have an even more profound influence on such intentions. Individuals who intend to travel during the pandmic may cancel or change their plans because of opposition from their families.

Before the outbreak, people had the freedom to choose where, how and when to travel. Less than two years have passed since the COVID-19 outbreak, and national governments have maintained a conservative stance on reopening tourism due to fears of spreading the disease. For example, in New Zealand and the United States, border controls, restrictions on when or where people could go out, and even city closures were used to avoid the virus’s rapid spread through contact between people during severe outbreaks. This has resulted in a change in travel patterns and behavior (De Vos, Citation2020). This paper aims to highlight the impact of the pandemic on the willingness to pay. As of the review, although countries are opening their borders, the travel patterns are still very different from those before the pandemic while the pandemic is still in flux.

Individuals have also changed their travel plans and styles in response to pandemic prevention measures to reduce their likelihood of infection (Asmundson & Taylor, Citation2020; Beck & Hensher, Citation2020; De Vos, Citation2020). Based on a survey regarding the changes in family travel styles of 1,073 respondents at the early stage of the pandemic in Australia (March 2020), Beck and Hensher (Citation2020) reported that 78% of respondents had changed their weekly travel plans (32% of respondents had families with children). A higher percentage of respondents with families with children had reduced travel than that of those with families with only middle-aged and older adults; accordingly, this decrease in travel was associated with parents’ concern for their children’s health. A higher percentage of moderate- or high-income families reduced their travel frequency than that of low-income families. Moreover, 58% of respondents expressed concern over being infected on public transportation, which led them to more frequently use private vehicles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a multitude of lifestyle changes. Working from home, online learning, and fewer large-scale events have led to a decrease in travel demands. Moreover, to maintain their health through outdoor exercise, people have favored destinations close to their homes, including parks or natural ecological environments, to avoid long-distance driving or use of public transportation (De Vos, Citation2020). Additionally, people have changed tourist behaviors to maintain social distance, such as more frequent use of private vehicles to avoid public transportation and minimize potential contact with other passengers (Troko et al., Citation2011). Tourists who cannot avoid public transportation have avoided travel during rush hours whenever possible (De Vos, Citation2020).

Studies conducted during the SARS and MERS pandemics have supported that pandemics can affect emotional and psychological health (Chua et al., Citation2004; Lee et al., Citation2007; Person et al., Citation2004). Although the COVID-19 pandemic has undermined daily living and psychological health, it has also caused changes in behavioral cognition. For example, people have increasingly become more aware of their own feelings, appreciative of the opportunities to be with family and friends, and satisfied with what they have and their opportunities to travel (Lee et al., Citation2007; Ornell et al., Citation2020).

Regarding travel choice, personal factors such as gender, age, education, income, and place of residence all influence travel choices (C.-F. Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Mahboob et al., Citation2021). Psychological factors (including attitudes and perceptions) of tourists towards the destination are expressed through tourists’ willingness to revisit, satisfaction with the destination, frequency of travel, length of stay, willingness to participate in tourism activities, and willingness to pay the price (Back et al., Citation2018; Simon et al., Citation2020; Yang, Citation2018). Accordingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected tourists’ attitudes toward and appraisals of their travel choices (C.-F. Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Ornell et al., Citation2020). In deciding on travel behaviors, tourists—from the perspective of cognition—collect information related to their destinations and changes in external environments, establish a relationship with the information, convert it into subjective perceptions, and determine their tourist destination and willingness to pay according to their appraisal.

This paper selected section 2.1 and this section to assess relevant variables such as travel behavior, personal factors, and the willingness to pay. A questionnaire was used to collect information on tourists’ willingness to revisit, satisfaction, frequency of travel, length of stay, participation in tourism activities, and willingness to pay higher prices during the pandemic. The empirical analysis in section 6 was used to verify the extent to which the “pandemic” factor influenced the value of the tourism environment and the factors that influenced the willingness to pay.

2.3. Non-market valuation of urban ecotourism

The value of tourism-related ecological resources has been discussed by many researchers (Bowker & Stoll, Citation1988; Damigos & Kaliampakos, Citation2003). As natural resources linked to tourism spending have no market equivalent, their value is difficult to determine through market transactions (Barbier, Citation1994) so a non-market asset approach is usually employed. The Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) is a frequently used method that was proposed and empirically proven by Ciriacy-Wantrup (Citation1947). The Contingent Valuation Method is now extensively used to evaluate natural resources and environmental benefits (Bowker & Stoll, Citation1988; Damigos & Kaliampakos, Citation2003). The Contingent Valuation Method uses a questionnaire survey to establish a contingent market and asks the interview subject their willingness to pay (WTP) for a non-market asset, or their willingness to accept (WTA) to compensate for environmental change.

Value can be assessed based on use value and non-use value. Use value assesses the price that the user is willing to pay, after using the tourism sources of that region, to preserve the right to future use. The measure is based on subjective satisfaction following the tourism (Whitehead & Blomquist, Citation1991); non-use value is also referred to as conservation value (Krutilla, Citation1967).These values represent the price that people are willing to pay for the permanent preservation of a resource or to make it available for future generations. Whether the resource itself can actually be used is not taken into consideration (Whitehead & Blomquist, Citation1991). In this paper, the value of ecotourism resources in Maokong are examined including their use values and conservation values in order to assess the price that users are willing to pay for the preservation of Maokong’s ecotourism resources. The total value can then be derived.

Assets can be classified as market assets or non-market assets based on their characteristics. The former gains its value through transactions while no transaction markets exist for the latter and its value cannot be assessed through transactions. The natural scenery, ecology and cultural resources possessed by the Maokong region have no comparable assets in the market, so the Contingent Valuation Method was used in this study as the assessment tool. The Contingent Valuation Method uses questionnaire surveys to establish a contingent market to ask respondents the price they would be willing to pay for the ecotourism assets of the Maokong region as a reflection of the respondents’ preferences.

3. Ecotourism resources in the Maokong regionFootnote2

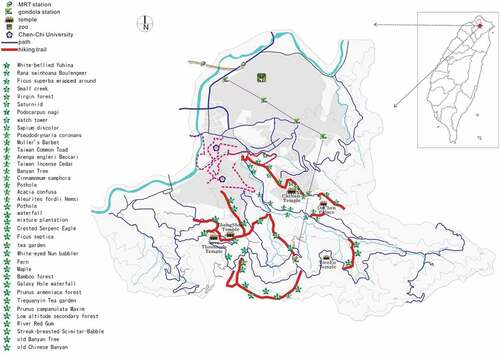

Based on the above description of urban ecotourism’s attributes, the Maokong area has the potential for urban ecotourism development. Maokong is located in the south of Taipei City where hillside development restrictions means that the area has retained most of its natural fauna, flora and pothole terrain. The nearby tea estates, historic temples, nature walking trails and convenient transportation system all further enhance Maokong’s prospects (see, ). An analysis of the existing tourism resources in Maokong based on its natural resources, industry, humanities resources and associated development is provided below.

3.1. Natural resources

The highest point of the Maokong region is the Erge mountain system with an altitude of 678m. The forest form consists mainly of tropical and sub-tropical broad-leaf forests as well as some temperate broad-leaf forests. Thanks to the complete plant ecosystem, the changing appearance of these low-altitude secondary forests throughout the year attracts outdoor education and leisure activities. The almond forest in Laoquan-li is particularly famous and has been gradually expanded over the past decade or so by local tea farmers. When the trees bloom in February and March each year, hordes of tourists are drawn by the sight.

In terms of faunal resources, the region is rich in birdlife. Around 56 species from 26 families are represented, including 31% of all resident species in Taiwan. Commonly sighted birds include the Chinese Bulbul, Japanese White-eye and White-eyed Nun Babbler. On weekends, numerous bird watchers take up position in the forests to admire the rich birdlife. The area is also home to many species of butterflies. Around a quarter of all butterfly species can be found here and the sight of large, colorful butterflies fluttering about the trees provides extra interest for tourists.

3.2. Industry and cultural resources

Tea is an important industry in the Maokong region with tourists tea plantations concentrated between Zhinan Elementary School and the Maokong mountains. The fresh air and green mountains attract many tourists looking to sample fine tea. The Taipei City Government has built a Tea Promotion Center to complement the development of tourism tea plantations and offer the general public a way to learn more about the history of tea making and tea plantations. The Muzha region is also a major producer of green bamboo shoots. The government organizes events during the green bamboo shoot season every year to attract tourists to the area.

As for cultural resources, the Maokong region is rich in cultural history and educational resources, with its temples being particularly well-known. The many temples in the region are all unique and include the Zhinan Temple, the Zhangshan Temple and the Tian-en Temple. The general public can use the inter-linked walking trails to reach each temple. National Chengchi University and Taipei City Zoo are also important destinations. The comprehensive walking trails within National Chengchi University campus and the zoo draw many hikers and tourists while National Chengchi University and the zoo business districts can provide any tourism services that tourists might need.

3.3. Associated tourism infrastructure

Infrastructure built by the local government in the Maokong region has been an important factor in its tourism development. The expansion of industrial roads has improved Maokong’s links with the outside world while small shuttle buses running between popular destinations have improved the convenience of international transportation. Free Maokong tour buses are even available on weekends to help tourists move between Maokong’s various sights, making it a more attractive destination. The opening of the Maokong Gondola has seen a surge in tourist numbers as well. To help meet city residents’ recreational requirements, the area around Maokong now has the Jingmei Riverside Park, bike paths, historical mountain trails, pavilions and signage systems. All of these link the various sites in Maokong together into one complete recreational system. The tourism resources of Maokong region are as listed in .

Table 1. Summary of tourism resources in the Maokong region

As for the introduction, Maokong has retained most of its natural fauna, flora and pothole terrain. The nearby tea estates, historic temples, nature walking trails, convenient transportation system and Maokong gondola all further enhance Maokong’s urban ecotourism potential, and the Maokong region can become an important recreational attraction in Taipei.。

Studies on tourism in the Maokong region can analyze from three perspectives: gondola, tea industry development, and travel choice behavior (see ). The Maokong Gondola was the first urban tourist gondola in Taiwan. Its installation helped increase the attractiveness of Maokong tourism and improve accessibility, but the introduction of tourists also impacted the lives of local residents, which is a problem faced by all tourist areas (Chou Yen & Chao, Citation2008; Lei et al., Citation2009; Lin & David Chang, Citation2009). By the perspective of industry development, tea industry development can be considered a cultural industry in the Maokong area. In order to promote the culture of the tea industry, a tourism itinerary with entertainment experience, education experience, and aesthetic experience should be proposed, taking into account the surrounding natural ecology and human environments, in order to highlight the unique characteristics of tourism in the Maokong region (Chuang & Lei, Citation2016; Huang, Citation2014; Lin, Citation2010; Lin & David Chang, Citation2009).

Table 2. Literature on Maokong tourism

Finally, customer perception and the shaping of spatial ambiance are also essential factors that influence choices of a trip to a Maokong region. The more satisfied people are with the spatial ambiance, quality of service, price, and experience of a destination, the more likely they will revisit. In order to increase tourism satisfaction, it is recommended to integrate Maokong tourism resources and different design programs for different tourism purposes to enhance tourism attractiveness (J.-H. Chen & Yeh, Citation2017; Lei et al., Citation2009; Tsai & Song, Citation2015). The results of Section 2 and Section 3 literature analysis will be incorporated into the subsequent questionnaire design and the selection of variables.

4. Research design

4.1. Research hypotheses

Travel choice behaviors are influenced by tourists’ psychological perceptions, attitudes, and subjective norms (Bianchi et al., Citation2017; Han & Kim, Citation2010; Soliman, Citation2019). Attitudes comprise tourists’ cognition, affection, and behavioral intentions (Best et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, the effects of the pandemic on tourists’ psychological perceptions and travel choices has caused them to value urban ecological environments and has increased their WTP for urban ecotourism.

H1: The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourists’ psychological perceptions has caused them to value ecological tourist environments which has increased their WTP for the ecotourism of Maokong (including use and conservation values).

The factors affecting tourists’ willingness to pay for ecotourism include frequency of visit, willingness to revisit, length of stay, and tour preferences (Nvight, Citation1996; White & Lovett, Citation1999; Whitehead & Blomquist, Citation1991). The following hypotheses were proposed to clarify the effects of these factors on tourists’ willingness to pay for the ecotourism in Maokong during the pandemic:

H2: Tourists’ WTP is positively correlated with their frequency of visit during the pandemic.

H3: Tourists’ WTP is positively correlated with their willingness to revisit.

H4: Tourists’ WTP is positively correlated with their length of stay during the pandemic.

H5: Tourists’ WTP is positively correlated with their tour preferences.

The contents of each hypothesis test and the relevant references are collated in .

Table 3. List of hypotheses

4.2. Empirical model—contingent valuation method

The Contingent Valuation Method evaluation process includes “establishing a contingent market”, “selecting the investigation method”, “determining the method of pricing inquiry”, “choose between willing to pay or willing to want” and “value estimation”. Price inquiries can take the form of a bidding game or payment card, and be open-ended or close-ended. With a payment card, the researcher compiles a payment card that shows the willing to pay or willing to want that the respondent is willing to accept under the conditions assumed on the card. The respondent’s choices can then be recorded. This approach preserves the advantage of the open-ended price inquiry while avoiding bias from different start points in price. It also offers an improvement on the close-ended price inquiry method that can only determine the lower limit of the willing to pay (Mitchell et al., Citation1989).

This paper used the payment card for the questionnaire survey since the method offers the strengths of open-ended price inquiries and is better at determining the respondents’ real willing to pay. The method has also been proven to be more exact and feasible (Bishop & Heberlein, Citation1979; Bowker & Stoll, Citation1988); to avoid the problem of starting bias, this paper conducted test interviews using the open-ended price inquiry method and used the results to compile the payment cards. Open-ended short answer questions were also retained in the hopes of establishing the respondents’ true willing to pay.

The willing to pay and willing to want exhibit asymmetric valuation tendencies (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation2013). Empirical research has found that respondents tended to be more generous on the willing to want but more conservative when it comes to the willing to pay, leading to quite disparate results (Bishop & Heberlein, Citation1979; Cummings et al., Citation1986); the willing to pay can’t exceed the respondent’s income while there is potentially no limit on the willing to want (Hanemann, Citation1984). As the goal of this paper is to learn what price tourists would be willing to pay for the preservation of Maokong’s ecotourism resources, the willing to pay was chosen as the basis of valuation to avoid the unlimited escalation of the willing to want. One-time payment was set as the payment tool to determine the true value that tourists assign to urban ecotourism resources.

During the actual survey, the payment card method involved the respondents circling the willing to pay; the circled prices were expressed in terms of frequency and thus can be considered discrete data. In this paper, the ordinal regression model was used for approximation while the Poisson regression model and negative binomial model were used for testing. The former is the most basic model among the ordinal variable statistical methods with all events assumed to be independent. Utilization of this model assumes that the conditional mean is equal to the conditional variance. The model can then be expressed as:

Here is the estimated WTP,

is the independent matrix and

the parametric matrix. Empirical research has found that the conditional variance often exceeds the conditional mean. Here the negative binomial regression model developed from the Poisson regression function and gamma distribution can resolve the inequality between conditional variance and condition mean.

The willing to pay of individual users can be estimated using (2) while the mean willing to pay can be estimated using (3).

5. Questionnaire design and survey

This study investigated whether the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourists’ psychological perceptions and travel choices has caused them to view ecotourism as more valuable and whether this has increased their willingness to pay for the ecotourism in Maokong (including use and conservation values) using a questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of the following three sections:

5.1 This section evaluated the effects of the pandemic on travel choice behaviors and perceptions through examination of participants’ frequency of Maokong visits before and after the outbreak, their willingness to revisit Maokong during the pandemic, their purpose for travel (i.e., whether their trip was specifically to Maokong), their length of stay, the transportation they used, their willingness to take public transportation during the pandemic (e.g., gondolas and buses), and the categories of their tourist activities.

5.2 This section evaluated respondents’ willingness to pay for the ecotourism in Maokong during the pandemic through the following items:

5.2.1 Respondents were asked whether the pandemic has affected their psychological perceptions and increased the value of Maokong as an ecotourism site.

5.2.2 Liu (Citation2009) reported that each interviewee was willing to pay an average of NT$1,794 for ecotourism. In this study, the respondents were asked whether they were willing to pay more than NT$1,794 to continue conserving and using the ecotourism resources of Maokong after the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents were then asked their reasons for being willing to pay more and how much more they would be willing to pay.

5.2.3 Liu (Citation2009) reported that each respondent was willing to pay an average of NT$2,608 to conserve ecotourism resources.Footnote3 In this study, the respondents were asked whether they would be willing to pay more than NT$2,608 to conserve the ecotourism resources of Maokong for future generations. Respondents were then asked their reasons for being willing to pay more and the how much more they would be willing to pay.

To provide recommendations on future ecotourism planning for the Maokong region, the survey presented four types of day tours for respondents to choose from. Asking respondents what eco-tourism options they would be willing to pay more for. The four types of tours were: Trail Guide Tour: Professional guides lead a tour of the walking trails while introducing the history of the Maokong region as well as tales of early settlers; Tea Industry Experience Tour: Introduction to the tea species in Maokong and the tea leaf baking process, with guides to introduce tourists the fun of tea appreciation; Religious Scenery Tour: This includes a tour of the historical Zhinan Temple to experience the Confucian/Taoist spirit and understand temple building characteristics as well as learn about Maokong’s unique pothole terrain; Ecotourism Tour: Professional guides will lead tourists on a tour of ecological resources including the cherry flowers, almond flowers, lupin flowers, acacia trees as well as other plants and fauna.

Part 3 covered the tourists' basic personal details including gender, age, education, occupation, income and place of residence.

The online questionnaire was conducted from March 1 to 14 March 2021, during which time Taiwan was under Level 2 pandemic alert; the government did not restrict people from participating in outdoor activities but required them to wear masks and maintain social distance at all times. The questionnaire was initially administered to tourists who had travelled to Maokong and was continued through snowball sampling, with 573 samples being returned. Because the goal of this study was to analyze the effects of the pandemic on tourists’ willingness to pay for the ecotourism in Maokong, we focused on responses from tourists who had travelled to Maokong during the pandemic and excluded responses from those who had not. We further excluded invalid responses. A total of 257 valid responses were obtained. As it was impractical to estimate the size of the parent body, using the calculation formula proposed by Bateman et al. (Citation2002)with a confidence interval of 95% gave an effective sample size of 249. As257 valid responses were recovered this should be representative of the parent body.

6. Analysis of empirical results

6.1. Analysis of questionnaire survey results

According to the valid responses, 99 (38.52%) and 44 (17.12%) respondents had travelled to Maokong at least once per year and at least once every six months before the outbreak, respectively; 170 (66.15%) and 36 (14.01%) respondents had travelled to Maokong at least once per year and at least once every six months after the outbreak, respectively. Accordingly, 61.48% of the respondents had travelled to Maokong at least twice before the outbreak. At the time of this study, the pandemic had lasted for more than 1 year, and the unpredictability of the pandemic had already affected people’s willingness to travel. Therefore, relatively few tourists had travelled to Maokong, and only 33.85% of the respondents had travelled there at least twice after the outbreak. Before the pandemic stabilized, most tourists traveled conservatively; only 38.52% of respondents expressed intentions to increase their frequency of travelling to Maokong. Of the respondents, 192 had travelled specifically to Maokong (74.17%) and 37 had stopped by Maokong on an itinerary (14.40%), which indicates that 74% of the tourists viewed Maokong as an attractive tourist destination. A total of 143 respondents stayed in Maokong for less than 3 h (55.64%); 46.58% stayed for 3–6 h. This differed significantly from the findings of Liu (Citation2009), in which 50% of the respondents stayed at their tourist destinations for 3–6 h. This is likely because Maokong currently prioritizes food and beverage consumption as its primary travel motivators and is easily accessible from the Taipei Metropolitan area and, therefore, does not attract tourists for long stays. A total of 138 (53.70%) and 45 (17.51%) respondents travelled to Maokong in private vehicles and gondolas, respectively. This indicates that tourists increased private vehicle use to reduce the likelihood of contact with others on public transportation. Moreover, 46.3% of respondents agreed that the pandemic affected their willingness to take gondolas and public transportation and scored an average of 3.28 in their agreement. This aligns with the findings of Beck and Hensher (Citation2020) on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on family travel styles.

Of the respondents, 184 (27.75%), 166 (25.04%), and 124 (18.70%) indicated drinking tea and eating, hiking, and strolling as their primary leisure activities in Maokong, respectively. Accordingly, hiking and strolling in addition to dining were common leisure activities among Maokong tourists; this result may provide a reference for future formulations of ecotourism plans.

Regarding the value of the ecotourism in Maokong during the pandemic, 239 respondents expressed that they recognized the value of ecotourism because of the pandemic (92.99%), scoring an average of 4.38 on the level of agreement. This indicates that people have increasingly come to appreciate the natural ecological environments around their homes after the COVID-19 outbreak. Regarding use value, a total of 130 respondents expressed a willingness to pay more than NT$1,794 for ecotourism after the outbreak (50.58%), with 71 (27.63%) and 58 (22.57%) respondents reporting being willing to increase spending by NT$200 and NT$500, respectively. The average increase in WTP was NT$744.07. Regarding conservation value, only 62 respondents reported being willing to pay more than NT$2,608 to conserve the ecological environment of Maokong for future generations (24.12%). Furthermore, 73 respondents were willing to increase the amount by NT$200 (45.06%), 52 were unwilling to increase their WTP (32.10%), and 52 were willing to increase their WTP by NT$500 (32.10%). The average increase in WTP was NT$642.21. Rather than preserving the ecological tourism environment in Maokong for future generations, respondents preferred spending on themselves. This may be associated with an increased focus on realism and a sense of uncertainty about the future due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Chua et al., Citation2004; Lee et al., Citation2007; Person et al., Citation2004).

Regarding the four ecotourism tours, 179 (69.65%), 33 (12.48%), and 27 (10.51%) respondents expressed that all, only the ecotourism, and only the tea industry experience tours would increase their WTP, respectively. Accordingly, the tea industry experience and ecotourism tours should be prioritized as the primary models for tourist experiences in Maokong.

Finally, the respondents’ basic profile and the descriptive statistical data of the respondents are listed in the in the Appendix.

6.2. Analysis of empirical variables

This study aimed to explore whether the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced tourists’ psychological perceptions and travel choices and increase their WTP to highlight the importance of ecotourism in Maokong. The factors for the WTP were also analyzed for reference in promoting ecotourism in Maokong. The empirical variables used are as shown in .

Table 4. Description of the variables included in the empirical model variables

6.3. Model calibration

The data from the questionnaire was analyzed using LIMDEP software. On the choice of discrete variable test model, if the mean and variance of the variables are equal, then the Poisson regression calibration results can be trusted. If not, the calibration results from the negative binomial regression model can be trusted. Model selection can use testing for over-dispersion.

First, testing was conducted on the price willing to be paid for the use value, assuming the significance level is 0.05, the t value of g(ui) and g(ui2) was hypothesized to be significant, indicating that the variance and mean of the price willing to be paid is not equal, and that the t value is positive; therefore it can be judged that the price willing to be paid related to the use value test result should depend on Negative Binomial Regression.

The next step was to substitute the empirical variables into the negative binominal regression model. The results () showed that the six variables of” Frequency of visit after COVID-19 “, “ Willingness to revisit, “Length of stay time”, “Agreement on ecotourism preciousness”, “Choice of travel tours” and “Age” all achieved 95% confidence interval, indicating a very significant influence on willing to pay. “Willingness to increase the use value more than NT$1794” reached the 90% confidence interval so it had a slight influence on the willing to pay. The influence of the remaining variables was found to be not significant.

Table 5. Calibration results for the willingness to pay of use value

The non-influential variables above were screened and then tested to derive the corrected calibration results. The result was that the significance of the variables increased so “Frequency of visit after COVID-19”, “Willingness to revisit”, “Length of stay time”, “Agreement on ecotourism preciousness”, “Willingness to increase the use value more than NT$1794”, and “Age” all achieved 99% confidence interval, indicating a very significant influence on the willingness to pay (WTP). The model’s ᵪ2 is significant and has an explanatory power as high as 0.98, making it quite appropriate for use with the negative binomial regression model.

Testing on the WTP for conservation value found that the calibration results for negative binomial regression should be trusted as well. During the test, the variable of “Length of stay time” reached 99% confidence interval, so it has a very significant influence. Three variables of “Willingness to revisit”, “Choice of travel tours” and “Age” all had a confidence interval of 95%, showing a significant influence. The remaining variables did not have a significant influence.

The non-influential variables listed above were screened and then tested to derive the corrected calibration results. The result was that the significance of the variables increased so “Willingness to revisit” achieved 99% confidence interval, indicating a very significant influence on the WTP. The model’s is significant and has an explanatory power as high as 0.99, making it quite appropriate for use with the negative binomial regression model ().

Table 6. Calibration results for the willing to pay of conservation value

6.4. Discussion

6.4.1. Hypothesis verification

The COVID-19 pandemic has cost lives, psychological health, and opportunities to travel. Tourists’ intentions and attitudes are affected by external environments, affection, and psychological perceptions (Asmundson & Taylor, Citation2020; Beck & Hensher, Citation2020). Changes in their psychological perceptions may cause tourists to increase their acceptance of urban ecotourism and their willingness to pay. According to the empirical results of the use value model (), the agreement on ecotourism preciousness (X6) satisfied the 99% confidence interval, indicating its significant positive influence on the use value of the ecotourism resources of Maokong. According to the empirical results of the conservation value model (), the agreement on ecotourism preciousness (X6) did not significantly influence the conservation value of the ecotourism resources of Maokong. Accordingly, H1 was partially supported. During the SARS and COVID-19 pandemics, people felt powerless with respect to future changes and grasped only onto immediate reality (Lee et al., Citation2007). This was reflected in the respondents’ willingness to pay for the ecotourism of Maokong; although those who accepted ecotourism were willing to pay significantly higher prices for its use value, acceptance did not significantly affect their willingness to pay to conserve the ecotourist environment.

A higher frequency of visits to a given tourist destination reflects the desirability of the destination, and tourists who travel frequently to this destination become more emotionally attached to it and, therefore, increase their willingness to pay (Back et al., Citation2018; Bianchi et al., Citation2017). According to the data presented in , the frequency of visit after COVID-19 (X2) satisfied the 99% confidence interval regarding its effect on use value, indicating its significant positive influence on respondents’ willingness to pay for use value. However, the variable did not satisfy the 99% confidence interval regarding its effect on the conservation value, indicating that tourists’ frequency of Maokong visits did not significantly affect their willingness to pay to conserve its environment. Accordingly, H2 was partially supported. Having experienced the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their psychological health, economic development, and general activities, tourists who intended to travel to Maokong during the pandemic understood the value of its ecological environment and, therefore, increased their willingness to pay for its use value. However, due to the tourists’ sense of uncertainty toward the future, their willingness to pay to conserve the environment of Maokong was not significantly affected.

A higher willingness to revisit and longer length of stay generally indicate that tourists favor a given tourist destination and that the destination is more attractive to them (Nvight, Citation1996; White & Lovett, Citation1999; Whitehead & Blomquist, Citation1991), which increases their willingness to pay. As presented in the empirical results, the willingness to revisit (X3) and length of stay times (X5) achieved a 95% confidence interval with respect to their effects on tourists’ willingness to pay for use and conservation values. This indicated that both variables significantly reinforced the tourists’ willingness to pay for both values in spite of the pandemic, which supports H3 and H4 and indicates that Maokong remains considerably attractive to tourists even after the COVID-19 outbreak. The local government, residents, and shop owners must collaborate to formulate tours to increase tourists’ emotional attachment to Maokong and lengthen their stay and thereby establish Maokong as a major suburban ecotourism destination.

Tourist destinations with more diverse, more inspiring, more innovative, or in-depth tours are more attractive to tourists. As a result, both their willingness to revisit and the lengthen their stay are increased (Back et al., Citation2018; Han & Kim, Citation2010), which in turn increases their willingness to pay. The empirical results indicated that tourists’ tour preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic achieved a 99% confidence interval with respect to their effects on tourists’ willingness to pay for use and conservation values. Accordingly, the variable reinforced the tourists’ willingness to pay for both values significantly, supporting H5. The respondents expressed that all four tours would increase their willingness to pay, particularly the ecotourism and tea industry experience tours. All four tours, particularly the ecotourism and tea industry experience tours, may be implemented in Maokong. However, such tours must be promoted and appropriately managed and be implemented in a manner that complements the local characteristics of Maokong.

Regarding the demographic information of the respondents, age was significantly correlated with their willingness to pay for use and conservation values. Respondents’ travel behaviors were primarily influenced by their cognition and attitudes (Um & Crompton, 1990), which varied according to age group. The respondents of different age groups differed in their feelings toward the SARS and COVID-19 pandemics; thus, they also differed considerably in their willingness to pay. The results of hypothesis verification are listed in .

Table 7. Calibration results for hypotheses

6.4.2. Estimation of WTP

According to the empirical results, the revised estimates of the respondents’ willingness to pay for use and conservation values are as follows:

Where

represented willingness to pay of the use value more than NT$1794,

represented willingness to pay of increase the conservation value more than NT$2608, i represented observations (i = 1,2,3, … n), x2 represented “Frequency of visit after COVID-19”, x3 represented “ Willingness to revisit”, x5 represented “Length of stay time”, x6 represented “Agreement on ecotourism preciousness”, x7-1 represented “Willingness to increase the use value more than NT$1794”, x8 represented “Choice of travel tours”, x10 represented “Age”.

This study incorporated the above empirical results into Equationequations (3)(3)

(3) , (Equation4

(4)

(4) ) and (Equation5

(5)

(5) ), resulting in mean increase value of use and conservation values of $757and $653 for ecotourism resources in the Maokong region. Estimation of the resource’s overall non-market value was made using the average tourist numbers of 2011 ~ 2019/12/31(before the COVID-19 outbreak) for the Maokong region each year, giving an increase use value of NT$874,520,717 each year and an increase conversation value of NT$754,375,203 year. The total increase non-market value therefore reached NT$1,628,859,920 each year. If the average use and conservation values of NT$1,794 and NT$2,608, respectively (Liu, Citation2009), are applied, the annual use and conservation values of Maokong would be NT$2,947,029,995 and NT$3,767,253,945, respectively, at a total NT$6,714,283,940. Accordingly, the ecotourism resources in Maokong were invaluable to the respondents.

7. Conclusion

The effects of COVID-19 on international movements, work, daily living, and tourism are globally unavoidable, and consequently, people must adapt to the changes in their lifestyles incurred by the pandemic. However, in order to satisfy people’s need for outdoor exercise and travel during the pandemic. This paper’s findings can help countries rethink the feasibility of improving the quality of tourism and changing traditional tourism patterns during the pandemic. All countries must improve the quality of tourism and adjust traditional forms of tourism to create sustainable and inclusive eco-tourism that fulfills the Sustainable Development Goals outlined by the United Nations (SDGs).

Suburban outdoor landscapes are near places of work and residence can be easily accessed by walking or on bicycles. The ecological resources and open spaces provided by these landscapes reduce the need for long-distance trips and facilitate avoidance of personal contact and public transportation. Furthermore, access to natural environments has physical and psychological health benefits. Maokong features rich ecological resources, topographical landscapes, and cultural characteristics. Furthermore, it is accessible by Mass Rapid Transit and gondola systems and is a site for daily leisure activities for residents from the Taipei metropolitan area. Maokong, therefore, has strong potential as a site for urban ecotourism.

Most studies on the relevance of the outbreak to tourism have focused on tourism patterns after the outbreak, the significant reduction in tourism, and the impact on tourism (Beck & Hensher, Citation2020; Troko et al., Citation2011; De Vos, Citation2020). The pandemic’s impact on people’s psychological perceptions, such as a greater appreciation of their feelings, the present, and the opportunity to travel (Lee et al., Citation2007; Ornell et al., Citation2020), has not yet been discussed concerning the value of tourism. In this study, a literature review and empirical research were conducted on the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on psychological health and travel choice behaviors based on the findings of Liu (Citation2009). The results indicated that tourists’ travel choice behaviors and psychological perceptions were profoundly affected by the pandemic, which led them to increasingly recognize the value of ecological resources and increase their willingness to pay for the use and conservation value of urban ecotourism.

This paper uses the Contingent Valuation Method to quantify the impact of psychological factors on the value of eco-tourism. In terms of theoretical implications, the paper combines the exploration of individual psychological cognition, travel choice behavior, and non-market value assessment. It verifies the correlation between these three factors through empirical research. This paper is innovative and contributes to both theory and application.

Hypotheses were established to verify the relationship between travel choice behaviors and WTP during the COVID-19 pandemic. Higher frequency of visit, willingness to revisit, length of stay, acceptance of ecological tourist environments, and ecotourism preference during the pandemic increased willingness to pay for the use value of Maokong ecotourism. Furthermore, longer length of stay, along with higher willingness to revisit and ecotourism preference increased the conservation value of Maokong ecotourism. Respondents expressed that all four tours, namely the trail guide tour, the tea industry experience tour, the religious scenery tour, and the ecotourism tour, were able to highlight the unique characteristics of Maokong. However, the most preferred tours were the tea industry experience and ecotourism tours. Although all the four plans may be maintained as aspects of Maokong ecotourism, the tea industry experience and ecotourism tours should be particularly developed to complement the local characteristics of Maokong.

According to the empirical results of this study on the tourists in Maokong, tourists have increasingly recognized the value of suburban natural environments during the COVID-19 pandemic and are willing to increase their willingness to pay to preserve existing ecological resources and environments. The factors affecting willingness to pay include the frequency of visit, willingness to revisit, length of stay, and tour preferences. The severe impact of the outbreak on international exchanges and tourism will gradually return to pre-pandemic life as vaccines become more widely available and medical advances. Nevertheless, this is an opportunity for countries to rethink their position on domestic tourism. The results provide a reference for all countries planning domestic tourism development during the pandemic, for discovering unique urban and suburban natural environments, and for enhancing the quality of domestic tourism through tourist environment improvement and tour formulation. The relevant authorities should emphasize collaboration between local residents, shop owners, tourist industries, and local industry development associations and ecological conservation groups for tourism development and establish suburban landscape tourism that achieves both ecological resource conservation and recreational development.

In the design of tourism programs, we recommended that emphasis be placed on the value of natural and ecological resources, local humanities and historical characteristics, local industries, and the participation of local residents and tourists. We also recommended that “special local days” be set for the four seasons, unique festivals, and special days. By proposing different tourism programs, it is possible to create irreplaceable tourist attractions and activities that will increase tourists’ desire to revisit and create a sense of local attachment. Residents can thereby promote ecological conservation, tourism development, and physical and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shu-Wen Lin

The authors’ primary research area is urban planning and land use. Professor Chiu chairs The Shadow Center, which conducts cross-disciplinary and integrated research on urban planning. Professor Wang and Professor Lin chair the Industrial Land Research Lab, which focuses on the impact of urban industries on urban planning and development. The research themes include manufacturing, commerce, service industries, cultural industries, and tourism. The focus of the research is on the integration of theoretical analysis and practical application to make academic research contribute to the public. This paper studies the urban eco-tourism industry in Taipei’s Maokong Region. The findings of this study may serve as a reference for countries to promote urban eco-tourism activities during the pandemic.

Notes

1. Liu (Citation2009) reported the total urban ecotourism value of Maokong, including its use and conservation values, to be approximately NT$9 billion.

2. The Ecotourism Resources in the Maokong region are compiled from the Wenshan District Office of Taipei City (Citation2002).

3. Although more than 10 years have passed since Liu (Citation2009) reported these findings and the price index has since inflated, the focus of this study was whether respondents would raise their WTP to conserve suburban ecotourism environments after the COVID-19 outbreak to highlight the criticality of urban ecotourism during the pandemic. Therefore, the amount reported from 2009 was used as the baseline for WTP without factoring in price fluctuations.

References

- Adalja, A. A., Toner, E., & Inglesby, T. V. (2020). Priorities for the US health community responding to COVID-19. JAMA, 323(14), 1343–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3413

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Andari, R. (2019). Developing a sustainable urban tourism. Tourism and Hospitality Essentials Journal, 9(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.17509/thej.v9i1.16986

- Aronsson, L. (1994). Sustainable tourism systems: The example of sustainable rural tourism in Sweden. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2(1–2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510685

- Asmundson, G. J. G., & Taylor, S. (2020). How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: What all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 71, 102211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102211

- Back, R. M., Bufquin, D., & Park, J.-Y. (2018). Why do they come back? The effects of winery tourists’ motivations and satisfaction on the number of visits and revisit intentions. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 22(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2018.1511499

- Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

- Barbier, E. B. (1994). Valuing environmental functions: Tropical wetlands. Land Economics, 701, 155–173. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3146319

- Bateman, I. J., Carson, R. T., Day, B., Hanemann, M., Hanley, N., Hett, T., and Pearce, D. W. (2002). Economic valuation with stated preference techniques: A manual. Economic valuation with stated preference techniques: a manual. Edward Elgar.

- Beck, M. J., & Hensher, D. A. (2020). Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia - The early days under restrictions. Transport Policy (Oxford), 96, 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.001

- Best, R. J., Hawkins, D. I., & Mothersbaugh, D. L. (2007). Consumer behavior: Building marketing strategy. McGraw-Hill.

- Bianchi, C., Milberg, S., & Cúneo, A. (2017). Understanding travelers’ intentions to visit a short versus long-haul emerging vacation destination: The case of Chile. Tourism Management, 59, 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.08.013

- Bishop, R. C., & Heberlein, T. A. (1979). Measuring values of extramarket goods: Are indirect measures biased? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 61(5), 926–930. https://doi.org/10.2307/3180348

- Bower, G. H. (1975). Cognitive psychology: An introduction. Handbook of Learning and Cognitive Processes, 1, 25–80. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315781075

- Bowker, J. M., & Stoll, J. R. (1988). Use of dichotomous choice nonmarket methods to value the whooping crane resource. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 70(2), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.2307/1242078

- Chen, C.-F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

- Chen, J.-H., & Yeh, M.-H. (2017). The establish of nostalgic space a case study on the space around maokong’s gondola. Journal of Rural Tourism Research, 10(1), 1–17. https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?DocID=19973691-201706-201707270024-201707270024-1-17

- Chirgwin, S., & Hughes, K. (1997). Ecotourism: The participants’ perceptions. Journal of Tourism Studies, 8(2), 2–7.

- Chou Yen, H.-T., & Chao, C.-Y. (2008). A study of leisure traveling needs of maokong area cable car transportation. Journal of Leisur and Tourism Industry Research, 3(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.6158/JLTIR.200804_3(1).0005

- Chua, S. E., Cheung, V., McAlonan, G. M., Cheung, C., Wong, J. W., Cheung, E. P., Chan, M. T., Wong, T. K., Choy, K. M., Chu, C. M., Lee, P. W., & Tsang, K. W. (june 2004). Stress and psychological impact on SARS patients during the outbreak. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 49(6), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370404900607

- Chuang, J.-H., & Lei, L.-F. (2016). A study of the developing strategy for the tea industry in maokong. Journal of the Agricultural Association of Taiwan, 17(4), 415–425. https://doi.org/10.6730/JAAT.201612_17(4).0005

- Ciriacy-Wantrup, S. V. (1947). Capital returns from soil-conservation practices. Journal of Farm Economics, 29(4), 1181–1196. https://doi.org/10.2307/1232747

- Cummings, R. G, Arrow, K. J., and Bishop, R. C. (1986). aluing environmental goods: an assessment of the contingent valuation method. Totowa NJ: Rowman and Allanheld.

- Damigos, D., & Kaliampakos, D. (2003). Assessing the benefits of reclaiming urban quarries: A CVM analysis. Landscape and Urban Planning, 64(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00243-8

- De Vos, J. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100121

- Dodds, R., & Joppe, M. (2001). Promoting urban green tourism: The development of the other map of Toronto. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(3), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670100700306

- Gibson, A., Dodds, R., Joppe, M., & Jamieson, B. (2003). Ecotourism in the city? Toronto’s green tourism association. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15(6), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110310488168

- Haghi, M. R., & Heidarzadeh, E. (2021). Factors driving the realization of sustainable urban tourism with ecotourism approach, case study: Khansar city. Journal of Tourism and Development. https://doi.org/10.22034/JTD.2021.285189.2338

- Han, H., & Kim, Y. (2010). An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(4), 659–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.01.001

- Hanemann, W. M. (1984). Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation experiments with discrete responses. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 66(3), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.2307/1240800

- Huang, Y.-H. (2014). A study of the Tieguanyin tea industry network in Maokong, (master’s dissertation), National Chengchi University

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Leonard C. MacLean, William T. Ziemba (Eds.), Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99–127). World Scientific. https://doi.org/10.1142/8557 | July 2013