?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In Ethiopia, rural livelihoods are commonly subjected to diverse social, economic, institutional and natural-induced vulnerabilities, which affect the welfare state of households in rural hemisphere. In spite of that, rural farm households run-through different coping strategies to improve their resilience. Therefore, this study is going to assess the vulnerability context, contributory factors and its coping strategies in Takusa Woreda of North Western Ethiopia. The study employed multistage sampling techniques to select 200 sampled respondents, and descriptive statistics and logit model were employed for analysis. According to the result, on-farm activities include: crop and livestock production were highly vulnerable. Although vulnerabilities were occurred in off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities, households alternatively chooses these livelihood activities in combination with on-farm only strategy. According to the model result, sex, access to irrigation, income, and livestock production risk was significant (p < 0.01). Likewise, crop production risk and total livestock unit were also significant (p < 0.05). Based on the degree of vulnerability contexts rural farm households followed different coping strategies in line with the nature of livelihood strategies. Therefore, Ethiopian livelihood programs is advised to consider household socio-economic contexts and incorporate farm households coping strategies in policy designing to achieve livelihood security.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Livelihood vulnerability refers to the defenselessness of livelihoods in risks, trends and seasonality whereas coping strategy refers to households means of responding vulnerabilities. Livelihoods are subjected to social, economic, institutional, and natural-induced vulnerabilities which affect the welfare state of households in rural area. As a result, households run-through different coping strategies to improve their resilience. In Ethiopia, where agriculture is highly vulnerable to social, institutional, economic, and natural shocks, in turn identification of contributing factors and its coping strategies becomes inevitable so as to maintain livelihood security. In addition, off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities also faced vulnerabilities which is an alternative livelihood for agrarian households. Therefore, households take different coping strategies for agricultural and non-agricultural livelihoods to safeguard their livelihoods. Therefore, this study will be of public interest meanwhile it was conducted to determine the existing sources of livelihood vulnerability, contributing factors and households coping strategies.

1. Introduction

In the late 1970s and 1980s, the link between human livelihood activities and the impact of vulnerability was well articulated and organized, particularly in documentation in the 1980s. Furthermore, in the 1980s and early 1990s, the conceptual models of the overall understanding of the sources of vulnerability to shocks, risks, trends, and means of dealing with these vulnerabilities were documented as general theory (Twigg et al., Citation2001). Across all disciplines, livelihood vulnerability is considered a common theme as it is compared to the required public welfare assistance and explores how it falls under the normal welfare of households. The impact of risks could depend on the level of difficulty and the nature of livelihoods to cope (USAID (United States Agency for International Development), Citation2017).

Livelihood activities are provisional, ever-changing and alerted to the political, economic, and socio-cultural vulnerabilities occurred at a comprehensive household circumstances. All livelihood arrangements are not strategic and supportive but rather can ground disturbances to prospects for imminent livelihood capital development and hollow out poverty embeddedness. As the change in wider political and economic settings, the livelihood actions of the rearranges also regulated by farm households (Cornish, Citation2020). Hence, sustainable rural development policies and strategies give high emphasis in responding vulnerabilities of livelihood practices. Among the strategies such as: conservation practices of natural resources have been implemented for supporting people’s livelihood alongside vulnerabilities (WFP &CSA (World Food Program and Central Statistical Agency), Citation2019).

Therefore, vulnerability reduction is a fundamental part of adapting and managing disaster threats. It establishes a significant common pulverization of policies and practices (Cardona et al., Citation2012). Similarly, alongside the agricultural sector, the Ethiopian development plans of GTP I and GTP II mainly focused on the diversification of non-agricultural activities to reduce the vulnerability of farm households (FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia), Citation2018). Therefore, examining the factors contributing to livelihood vulnerability could be important for further policy interventions in the study area.

Despite development policies emphasizing vulnerability, agrarian societies in the Horn of Africa have faced serious livelihood degradation and poverty over the past year. Hence, farming households have been engaged and follow various adaptive schemes to increase their resilience. Therefore, the level of household adaptation and coping mechanisms could lead to changes in people’s livelihoods under different economic and environmental aspects associated with their food security status (Mengistu, Citation2017). Nevertheless, in Ethiopia, the lack of agricultural land and increasing landlessness in rural highland areas are becoming serious livelihood challenges (Belay et al., Citation2017).

Since the 1970s, Ethiopia has experienced more than 10 major drought episodes. Climate change has been shown to exacerbate the situation and pose a formidable challenge to predominantly rain-fed agricultural livelihoods. Given the similar exposure to climate variability and drought episodes, the vulnerability of community livelihoods has been mainly attributed to their low adaptive capacity and higher sensitivity indicators. Adaptability has been constrained by a lack of participation in community-based organizations and a lack of income diversification (Abeje et al., Citation2019). Hence, examining livelihood vulnerability, its contributing factors, and household coping strategies could be crucial to livelihood programming and other policy issues.

In addition, the main sources of vulnerability include: degradation of arable land, high population pressures on arable land, excessive drought, water scarcity, instability, erratic rainfall, and unavailability of livestock resources. For this reason, the poor and the rich members of society had to adopt different coping strategies depending on their wealth and level of vulnerability (Mengistu, Citation2017). Therefore, households design different coping strategies for precipitation variabilities, such as adaptive selection of crop varieties, arrangement of planting timing based on rainfall intensity, mixed crop species, annual rotation of crop fields, and use of water harvesting technologies. In addition, lending and borrowing food, selling livestock, engaging in non-agricultural activities, and remittances are considered important strategies to address livelihood challenges (Sime, Citation2019). Indeed, the factors that contribute to the occurrence of livelihood threats are multiple considerations. For this reason, this study was undertaken to provide some kind of knowledge to understand the contribution of household characteristics to livelihood vulnerability.

Similar studies in Ethiopia also showed that the vulnerability of rural livelihoods to shocks, risks, and seasonality can result from naturally occurring events, poor institutional performance, and physical factors. Unexpected rainy seasons and the ineffectiveness of a premature threat program may have deteriorated livelihoods and thrown the food system out of balance. Farmer responses to livelihood vulnerability vary depending on wealth level and socioeconomic status such as number of herds, land size, land productivity, engagement in social services, access to financial institutions and income level (Mengistu, Citation2017; Sime, Citation2019; Theodrose, Citation2016).

Overall, rural livelihoods in Ethiopia faced various social, economic, institutional, and natural vulnerabilities that affect the welfare status of households in the rural hemisphere. In order to withstand the vulnerabilities of livelihoods, governments and non-governmental organizations mainly intervene to improve livelihood security. Hence, the wealth-related, climate-related factors and other natural factors are identified as the main causes of livelihood vulnerability. However, most studies did not focus on sources of vulnerability rather they mainly emphasizes on the livelihood vulnerability to climate variability, livelihood vulnerability and coping strategies, and impacts of vulnerability. Therefore, analyzing contributed factors such as: the effect of socio-demographic and institutional factors on the occurrence of livelihood vulnerability through statistical inference could be vital to show contributing factors of livelihood vulnerability. In line with this, the households in the study area were also exposed to different subsistence vulnerabilities. However, the contributing factors for its occurrence have not been statistically identified and studied (Takusa Woreda office of Agriculture (TWAO), Citation2020). Consequently, this study is conducted to assess the existing rural livelihood vulnerabilities, factors contributing to livelihood vulnerability, and household coping strategies in Takusa Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia.

2. Literature review

2.1. Conceptual focus

Through different disciplines, vulnerability is generalized as the risk of dropping below a recognized level of welfare. Its effects can be determined by the level of exposure to a given risk and the ability to manage risk and cope with its consequences. Therefore, it can be expressed as the sum of risk and response (USAID (United States Agency for International Development), Citation2017). It is characterized as insecurity in the well-being of households in the face of changes in their external environment. The vulnerability has s two facets: an external side of seasonality’s, and critical trends; and an internal side of defenselessness caused by a lack of ability and means to cope with these (Asian Development Bank, Citation2017). Vulnerability to shocks can also vary. A drought could impact on natural capital causing field reduction, on other capital it may have little impact. Alike, flooding may destruct both physical and natural capital with little effect on the others. Thus, the nature of the capital determines the degree of vulnerability and showed a different level of resilience (Morse et al., Citation2013).

In recent years, droughts have resulted in crop damage, yield reduction, and serious water shortage. Water availability and the nature of livelihood strategies are the most important predictors of the livelihood vulnerability of households (Thao et al., Citation2019).

Vulnerability contexts are not the same across different farm households. It varies because of differences in the households’ sensitivity, adaptive capacity, exposure to natural disasters, and coping strategies. Different assets played a key role in coping with the vulnerability that the households experience. Households apply Coping strategies which may be used as an ex-ante risk management strategy or accumulation of assets rather than as an ex-post coping strategy to deal with stress or shocks confronting households (Madhuri et al., Citation2018; Osawe, Citation2013). Commonly rural farm households had higher exposure to vulnerability with low and poor coping strategies to resilient the changes. They are highly susceptible to bear changes in their livelihood. The variation in agriculture productivity and water availability negatively affects rural livelihoods (Shahzad et al., Citation2019).

Since the 1970s, Ethiopia has faced more than 10 major drought incidents. Climate change worsens the situation and presents an intimidating challenge to rain-fed agricultural livelihood system. Under conditions similar to climate variability and drought incidents, household livelihood vulnerability has been mainly attributed to their low adaptability and high sensitivity to livelihood vulnerability (Abeje et al., Citation2019). Large-scale farming exposure to farm household wealth and livelihoods of agrarian households was higher than that of small-scale farming. Households were more sensitive to large-scale than small-scale farming risk. Farm household assets and livelihoods are more vulnerable to the risk of large-scale farming practices than to the risk of small-scale ones (Abankwah, Citation2021).

The agricultural transformation from subsistence to export-oriented agricultural production helps households to be dependent on volatile agricultural commodity markets and may increase household exposure to crop shocks. Larger farm size has less likelihood of falling below optimal farm income. The production of high value and commercialized crops is resilient to yield reduction and loss (Junquera & Grêt-Regamey, Citation2020). Also, farm households engage in various subsistence activities that are less capital intensive and fewer skill to improve income levels and food security. But different livelihood practices are determined by different socioeconomic contexts, and these factors also determine levels of livelihood vulnerability. Anything that interferes with one livelihood affects opportunities for another livelihood (Yamba et al., Citation2017). Therefore, looking at the factors that contribute to livelihood vulnerability is a focus of this study. Furthermore, vulnerability and resilience are not linked but have separate entities. Resilience coping strategies help households implement planned mitigation actions. In addition, it can be seen that households with low human, financial, social, and physical capital have less capacity to cope with disasters. However, low vulnerability does not mean that they are highly resistant to damage (Madhuri et al., Citation2018).

2.2. Driving factors to livelihood vulnerability

The connections between climate change and threats to livelihoods are increasing. Factors associated with caste/ethnicity and gender dimensions also contribute to livelihood vulnerability. Female-headed households and those belonging to disadvantaged social groups are more vulnerable and have disrupted livelihood patterns. Factors such as climate extremes and associated hazards, dependence on natural resources, lack of financial assets, and weak social networks have been identified as components that determine overall levels of household livelihood vulnerability. Financial assets can be enhanced to increase household adaptability and ultimately reduce their vulnerability (Sujakhu et al., Citation2019).

According to Cardona et al. (Citation2012), vulnerability and exposure are not static across time and space scales. It depends on socio-economic, geographic, cultural, institutional, governance, and environmental factors. Individuals and communities are at different risk levels based on factors such as wealth, education, race/ethnicity/religion, gender, age, disability, and health status. A lack of flexibility and the ability to anticipate, be resilient and adapt to change are also important causal factors of livelihood vulnerability. High levels of vulnerability are generally the result of perverted development practices associated with ecological misconduct, rapid and unintended urbanization in risk zones, devastating dominance, and scarcity of livelihoods for the underprivileged.

Koirala (Citation2015) argues that households were most vulnerable to financial capital, followed by other capitals. However, livelihood vulnerability has been shaped by a set of interacting socio-environmental stressors. Limited access to the forest-centric natural resources, wasteful manipulation of water and land resources, unfortunate infrastructure, restricted access to basic public services are major factors that contributed to the study’s vulnerable livelihood. However, no socio-demographic factors were identified by the study to show their contributions to household vulnerability.

In addition, many factors contribute to the emergence of livelihood vulnerabilities, such as lack of access to infrastructure, resources, and services, including knowledge and technological means. They bear the impacts and consequences of large-scale environmental changes, including land degradation, biodiversity loss, and climate change, which affect the well-being of the most vulnerable populations (Devi et al., Citation2016).

The study conducted using the multinomial logit model on household-level determinants of vulnerability to livelihood insecurity: evidence from Maphutseng, Lesotho. The result showed that increasing head of household age, female-headed household, more family members, access to counseling services, and small property size are positively significant determinants of the occurrence of livelihood vulnerabilities (Thabane, Citation2015). Therefore, examining contributing factors could be a relevant for policy intervention in the study area.

Depending on the literature, livelihood vulnerability is determined by various man-made, natural, institutional, and wealth factors. Previous studies have identified mostly natural-induced factors and asset-related factors contributes to livelihood vulnerability. Also, most of the studies used different methodological approaches to examine the drivers of livelihood vulnerabilities. However, this study have identified particularly household demographic and related factors contributing to the occurrences of livelihood vulnerabilities through a binary logistic regression model.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Description of the study area

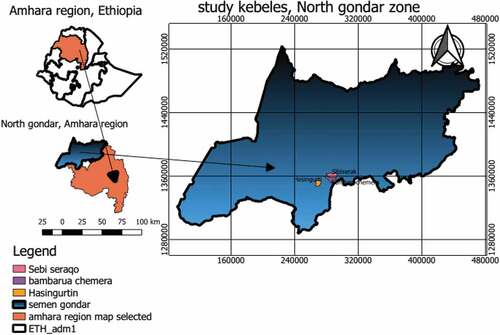

The study area, Takusa Woreda,Footnote1 is located in the North Gondar Zone of Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. About 830 km northwest of Addis Ababa. The Woreda is located about 95 km in the south west of Gondar town, and 135 km North West of Bahr Dar (the capital of the Region). It is located at 12°1ʹ56.64” N and 36°56ʹ47.76” E in North Western part of Ethiopia (CSA (Central Statistical Agency), Citation2007). The altitude in Takusa Woreda ranges from 600 to 2000 m above sea level. Based on the population projection of Ethiopia, Takusa Woreda had a total population of 153,253, of which 77,631 were male, and 75, 622 were female (CSA (Central Statistical Agency), Citation2013).

3.1.1. Livelihoods of the area

Takusa Woreda is well known by agricultural-based livelihoods, off-farm livelihood options, non-farm livelihood options, and seasonal migration. Although livelihood diversification exists, vulnerability contexts were observed in different livelihood activities like on-farm, off-farm and non-farm activities). Most commonly, the area is uniquely identified as the source of off-farm and non-farm activities due to the presence of investment activities in producing sesamen, cotton, barely and different cereal crops. Similarly, in the Woreda different cash crops were cultivated and create better market opportunities for households to be engaged and benefited. So, the Woreda is identified as one of the livelihood zone comprising diversification activities in addition to crop production and livestock husbandry (Takusa Woreda office of Agriculture (TWAO), Citation2020). The location of the study map is shown in the .

3.2. Research design

Cross-sectional survey research designs were used to organize and set findings of the study.

3.3. Sampling methods and procedures

The study applied a multi-stage sampling technique. Firstly, Takusa Woreda was selected by using purposive sampling because of the presence of vulnerability situations. Secondly, three representative kebelesFootnote2 were selected randomly from 18 rural kebeles. Thirdly, sampled households were randomly selected by lottery method. Lastly, probability to proportion to sample size were used to select samples of each sampled kebele. A total of 200 sample respondents were determined by using Yemane formula considering 95% of the confidence level (z = 1.96) and ±5% precision (Yamane, Citation1967).

Where, n = sample size, N = population size, and e = precisio

n level (0.05)

3.4. Data types and sources

The study employed both quantitative and qualitative data to achieve its objectives. The study uses data from both primary and secondary sources. Quantitative data include the socio economic data. Whereas qualitative data include: personal observation, key informant interview, and focused group discussion.

3.5. Data collection methods

Data from primary sources were obtained by using interview schedule of 200 sampled respondents, Focus Group Discussions and Key informant interview for the purpose of cross-checking. Additional data are also collected by reviewing formal reports from the Woreda (WoA), books, and other published and unpublished journals.

3.6. Method of data analysis

Both descriptive statistical tools, and qualitative narration were employed for analysis. Quantitative data were analyzed by using statistical tools (range, frequency, and percentage). Whereas qualitative data were collected from note taking and recording activities, key informant interview and focused group discussion. In the analysis of qualitative data, outputs were triangulated with quantitative survey results and it is also analyzed by narration of words/thematic analysis. Additionally, for the analysis of contributing factors of livelihood vulnerability binary logit model were applied and STATA software were used for the model outputs.

3.7. Econometric model

The study employed binary logistic regression model to identify the contributing factors of livelihood vulnerability. Although the binary logit and probit provide similar parameter estimates, the binary logit has an advantage over the probit when analyzing dichotomous outcome variables because it is extremely flexible and easy to use. Furthermore, it transforms the problem of predicting probabilities within the (0, 1) interval into the problem of predicting the probabilities of an event occurring within the real line (Hosmer, Citation2000). In addition, extra replications show that logit analysis is fairly indifferent to pure misspecification of the disturbance (Cramer, Citation2007). The dependent variable is livelihood vulnerability having to nature as 1 for vulnerable and 0 otherwise. Value 1 for vulnerability means households that are affected by vulnerability at least in one of their livelihoods and 0 if households were not affected by any vulnerability in their livelihoods. Different independent variables were selected for the study to infer their contributions on households being vulnerable or not. The model is specified as:

Following Gujarati (Citation2003), the functional form of logistic regression model was specified as follows:

where Xi is the independent variables and Y = 1 means the household is vulnerable. But now consider the following representation of livelihood vulnerability:

For ease of exposition, we write (3) as

Where Zi = β1+ β2Xi

It can be linearized, which can be shown as follows:

If Pi, the probability of livelihood vulnerability is given by (4), then (1− Pi), the probability of not vulnerable is:

Therefore we can write as

Now Pi/ (1− Pi) is simply the odds ratio in favor of being vulnerable and the ratio of the probability that a household will be vulnerable to the probability that it will not vulnerable. Now if we take the natural log of (6), we obtain a very interesting result, namely,

That is, L, the log of the odds ratio, is not only linear in X but also (from the estimation viewpoint) linear in the parameters. L is called the logit, and the name logit model.

Before conducting the model, multicollinearity among the continuous variables (Variance Inflation Factors (VIF)) and the associations (computing contingency coefficient) among discrete variables was checked. Also, results of robustness checks among variables showed non-existence of multicollinearity among variables. The robustness checks can be analyzed by employing heteroskedasticity checks and if it is insignificant there is no multicollinearity problem (Cramer, Citation2007). Hence, the study had check heteroskedasticity problem and the result showed insignificant (see appendix-1). The model results are estimated and interpreted in terms of marginal effect.

Own computation, 2020

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The vulnerability contexts

Livelihood vulnerability is understood as the insecurity of people’s well-being and lack of environmental friendliness, which collectively respond to an area’s difficulties (Theodrose, Citation2016). Most often, the social, economic, and natural factors tentatively determine the state of vulnerability at the household level. In addition, the geographical location of farm households also determines the level of exposure to risks, hazards, and seasonality (DFID (Department for International Development), Citation2000). In the study area, households experienced various shocks that affected their on-farm, wage, and resource-based livelihoods and non-farm livelihoods. Accordingly, different contexts of vulnerability were identified and ranked according to frequency and degree of impact on each livelihood activities such as on farm, off-farm, and non-farm. Even when the vulnerabilities in each livelihood strategy have been categorized, the problems observed in one livelihood activity become a problem for other livelihood activities as well. Therefore, assuming the differential impact of vulnerabilities on different livelihood diversification activities, the most frequently observed problems in each livelihood activity were identified and ranked. The details of the vulnerability contexts across all livelihood activities are discussed as follows.

4.1.1. Sources of vulnerability to on-farm activities

According to the survey result, there were problems in crop and animal production. As shown in Table , 75.5% of the total sampled households were vulnerable to crop production risks and shocks. Plant diseases such as root rot of peppers (89.9%) and lack of arable land (89.2%) were the first and second ranked problems in crop production, respectively. Sample households reported the following crop production risks they faced: pests (87.2%), low availability of improved seed and fertilizer (81.6%), shortage of capital and labor (72.2%), low soil fertility (41%), land degradation, and flooding (36.8%), frost (34%) and lack of rainfall (28.5%). It is important to note that the magnitude of the impact of the above issues varied from household to household. The key informant interview with Kebele-level development agents also found that households facing problems such as crop disease, lack of farm size, land degradation, and flooding were more likely to be involved in off-farm and non-agricultural livelihood activities than households did not face these problems. Similar findings by DFID (Department for International Development; Citation2000) argue that, vulnerability is a continuous reality for many poor small holder farmers. Rural livelihood activities might be made more or less vulnerable by short and extended trends. Moreover, as the total land that a household owned for cropping increases households are less likely to be exposed to livelihood vulnerability (Thabane, Citation2015). The hypothetical relationship of independent variables and dependent variable with variable nature, measurment and expected sign are shown in the

Table 1. The relationships between dependent and independent variables of the study

Table 2. Sources of vulnerability on crop and livestock production

Likewise, problems faced on livestock production were also identified and ranked based on their level of difficulty imposed on households’ production level. In the study area, insufficient grazing land was the critical trends that affect livestock production and productivity. According to the surveyed result, 93.2% of vulnerable households were challenged by highly fragmented, less fertile and insufficient grazing land. Which is first ranked problem of livestock production. Additionally, inaccessibility of veterinary medicine was a great challenge and second ranked problems for livestock production. The presence of animal diseases and lack of drinking water were also other problems that are faced in livestock production. In consistent to this finding, the study conducted by Welderufael (Citation2015), confirms that vulnerability of livestock production in Ethiopia were common and the problem exacerbates from one household to another. Also, marginal and limited natural grasslands are used as the chief sources of livestock vulnerability (Sime, Citation2019).

The result of focused group discussion also showed that household’s livestock production under vulnerabilities decreases the income earned from livestock products such as: milk, butter, sale of cattle’s/ruminants and other byproducts. In addition, the presence of animal disease such as: Anthrax (koreba), Bloating (locally called wajima), un expected removal of fetus, livestock Ticks (locally called meziger), fout and mouth(locally called Afe meyaz) are a great challenging problem of livestock production . As a result, they are obliged to choose the off farm and non-farm livelihoods and additional earning to their living. Vulnerability sources on on-farm livelihood activities are shown in Table below.

4.1.2. Sources of vulnerability to off-farm and non -farm activities

Off farm and nonfarm livelihood activities are diverse livelihood activities that are performed in addition to on-farm activities to generate additional income and support production of crop and livestock (Yenesew et al., Citation2015). In the study area, different vulnerability contexts impose difficulties on off and/or non-agricultural livelihood activities. As indicated in , The surveyed results showed that 81.5% of respondents who engage in off-farm activities were vulnerable to transportation problem and it is a first ranked problem that affect their movement to different places for doing the off-farm activities. As such, it affected their benefits from off-farm livelihood opportunities. It is also observed that the majority 79.8% of respondents were cited security problem, which was ranked second. It limited their daily operations and contract wage agricultural activities. Moreover, about 75.6% of respondents faced lack of job/unemployment opportunity which was ranked as third and 73.1% were vulnerable to price fluctuation as fourth ranked problem of off-farm activities. Even though, households were engaged in diversification of off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities, their level of choice and vulnerability is determined by wealth category. Households having poor wealth category are more vulnerable as compared to better wealth category farm households (Yishak, Citation2014)

Table 3. Sources of vulnerability to off-farm and non-farm activities

The result of focused group discussion confirmed that off-farm activities were challenged by several problems like security problem. Obviously, there was ample employment opportunities in the side of Metema and Quara by investors doing investment on sesame, cotton, and sorghum production. However, movement of households from one area to another was minimized as compared to past working conditions especially on the side of Metema and Quara investment areas due lack of order and law. Most landless households perform daily wage labour and contract weeding in these areas. Nonetheless, there was a conflict between Kimant and Amhara on the issue of demarcation and independence. Because of the conflict, illegal movement of individuals destruct the farm activities and led to loss of income and death of human beings. Also, it causes frustration for those investors, daily and contractual wage workers, and poor households. As a result, income generating opportunities of off-farm activities becomes at risk in these investment areas.

Similarly, household’s participation in non-agricultural activities was exposed to many vulnerability situations (). Shortage of capital (84.1%) was the first ranked vulnerability for nonfarm livelihood activities. Households that choose to participate in petty trade and trading of livestock’s (ruminants and cattle’s) were influenced by low financial capital which affects their trading activities. The main sources of vulnerabilities observed in non-farm activities were: Lack of non-farm training (79.4%), poor infrastructure (transportation) (77.8%), security problem (76.2%), low market linkage (75.4%), price fluctuation (71.4%), lack of job/unemployment (64.3%), high tax on small trade (58.7%), and death of small ruminants/cattle (12.7%).

Focused group result also showed that, non-farm activities are bound with diverse challenges resulted from infrastructural and institutional bottlenecks. Even though, farm households are engaged in non-farm livelihood activities, they are restricted to small and low earning non-farm activities. The main challenges were high tax assigned to small trading activities. Also, political instability, security issues, road facility and accessibility of financial capitals for running non-farm activities. The other challenge identified by focused group discussants was the lack of market information in conducting non-farm livelihood activities. Mostly, the price, preferred goods, and other market information are from traders that are less-advantageous for local non-farm livelihood practitioners.

“I was lived with my husband and my daughter. Unfortunately, I was not happy with my husband and led to a divorce. Since I’m divorced, my family let me live in a small cabin and make my own living with an acre of land. After that I got credit from the government and raised sheep. Although the work is interesting, it has been difficult to get grazing land to feed and I want a job that gives me a short-term income for consumption and supports sheep production. In the meantime, in addition to raising sheep, I have also started making pottery. But other senior potters dominated my work in terms of quality and challenged me to win customers. Over time I’ve tried selling pottery (like Mitad, Dist, Minichet/Genibo, Gan,Footnote3 etc.). Although I earn income from pottery work and support my family, various vulnerabilities emerged including: Decrease of pottery due to shortage of firewood, Limited number of customers seasonally, Expensive firewood, Lack of public transportation, Excessive cost of transportation by motors and bajajs, Low acceptance in of the community, lack of home to work during the summer season, etc.) (Key informant interview, 2020). The picture of sampled pottery products with the key informant women is shown in .

4.2. Contributing factors of livelihood vulnerabilities

An econometric model, binary logit regression was employed to assess the contributing factors of livelihood vulnerability. Sixteen independent variables were included in the model. The model output revealed that Sex (sex), access to irrigation (ACCIRRIG), Income (Income), and Livestock production risk (LPR) was significant (p < 0.01). Crop production risk (CPR) and Total Livestock unit (TLU) were also found to be significant (p < 0.05). The remaining nine variables were statistically insignificant to household’s livelihood vulnerability. In light of the above model results shown in , possible explanations for each significant independent variable are given sequentially as follows:

Table 4. The logistic regression results for the contributing factors of livelihood vulnerability

4.2.1 Sex of the household head

As hypothesized sex of the household head was statistically significant at less than 1% probability level. It showed a negative relationship with household livelihood vulnerability status. So, all factors being equal, if the female head of the household increases by one, the likelihood of households being livelihood vulnerability increases by a factor of 26%. The possible reason could be that female heads household do not have access to training, do not have timely information about unexpected shocks, are not treated equally and benefit from government support programs. Also, female heads households are culturally shaped and may not have an opportunity to realize their full potential. The vulnerability indices showed that female-headed households were more affected by fluctuations. The result is consistent with the study by (Alhassan & Kuwornu, Citation2018; Sujakhu et al., Citation2019; Thabane, Citation2015); since the household is headed by female, there is more likely to be vulnerable to threats to their livelihood.

4.2.2 Crop production risk (CPR)

As hypothesized, crop production risk was significant with a probability of less than 5% and showed a positive association with threats to household livelihoods. Assuming other factors remain constant, the likelihood of households exposed being at risk of livelihoods increases by a factor of 18.4% for a one unit increase in crop production risk. The possible reason could be that the risk of crop production in the production of household’s production reduces the amount of crop yield, poor management practices, unplanned cultivation practices, and leads to the occurrence of livelihood vulnerability. The risk of cop production could be at the heart of the vulnerability of household’s overall livelihood activities. The result agrees with the results of (Devi et al., Citation2016; Sujakhu et al., Citation2019; Yenesew et al., Citation2015); Crop production risk is the main cause of livelihood vulnerability in farming households positive and significant.

4.2.3. Total Livestock Unit (TLU)

It was found to have a negative and significant impact on household livelihood vulnerability, being is statistically significant at less than 5% (at p < 5%). If the total livestock unit increases by one TLU, the household’s livelihood vulnerability decreases by 28.9%. This could be due to rural households accumulating their wealth in form of livestock and it helps to respond to risk and reduces the outcomes that households are exposed to the vulnerability of their livelihoods. Model results from this study support that households with relatively large livestock size (TLU) as less vulnerable. The result is agrees with (Panthi et al., Citation2015; Thabane, Citation2015); Livestock ownership by households is a deterministic power, whether or not household livelihoods are at risk. Because livestock farming is an important livelihood sector, it is a significant indicator of livelihood vulnerability. On the contrary, Devi et al. (Citation2016) showed that gaps in infrastructure and crop production are more sensitive to the occurrence of livelihood vulnerability.

4.2.4. Access to irrigation (ACCIRRIG)

It was found to have a negative and significant impact on household livelihood vulnerability, being statistically significant at less than 1% (at p < 1%). As household access to irrigation increases by one unit, household livelihood vulnerability decreases by 23.1%. The possible reason could be that access to irrigation increases household well-being and reduces the likelihood of livelihood threats occurring. Apparently, irrigation practices were developed to improve for improving livelihood and reduce its vulnerability by practicing different portfolios during the off-season. The result agrees with the results of (Gravitiani et al., Citation2018; Koirala, Citation2015);The level of irrigated agriculture is practiced has a low likelihood of livelihoods being at risk to livelihood vulnerability.

4.2.5. Total income of household head (Income)

It was found to have a negative and significant impact on household livelihood vulnerability, being statistically significant at less than 1% (at p < 1%). If total household income increases by one birr (ETB), household livelihood vulnerability falls by 10%. The possible reason could be that households have higher income which helps them meet their family needs, get inputs for production and helps them to make a living (Alhassan & Kuwornu, Citation2018). Also, the result of Thabane (Citation2015), suggested that higher yields are more likely to make households less vulnerable to livelihoods. Being more affluent means less likely to face of livelihood threats (Cardona et al., Citation2012)

4.2.6. Livestock production Risk (LPR)

It was found to have a positive and significant impact on household livelihood vulnerability, being statistically significant at less than 1% (at p < 1%). If the risk of household livestock production increases by one unit, the vulnerability to household livelihood increases by 24.2%. This could be due to the risks of reduced household livestock production potential and the emergence of household livelihood vulnerability. The result agrees with (Panthi et al., Citation2015; Sujakhu et al., Citation2019); the households that faced risks in livestock production were more vulnerable to threats to their livelihoods.

4.3. Rural households coping strategies

According to Mengistu (Citation2017), common household strategies to manage with vulnerability include: selling assets, reducing consumption and livelihood diversification, and the strategies differ between rich and poor households. Rural households in the study area employed different strategies to address vulnerabilities encountered in their livelihoods. Accordingly, the selection and practice of coping strategies depends mainly on their level of wealth and the level of difficulties encountered in farm households. In the study area, 95.4% of vulnerable households adopted non-agriculture livelihood diversification as their main coping strategy, 74% engaged in non-agriculture livelihood activities, and 63.8% used the cultivation of drought-resistant crop varieties as a response to vulnerabilities (). Therefore, rural farming households had different coping strategies, determined by their own capabilities and existing environmental situations. According to the findings of (Sime, Citation2019), Farmers also dissimilar in their vulnerability and proficiency to managing risks. Hence, households pursue different livelihood coping strategies to increase resilience over vulnerabilities. The identified strategies includes; distribution grain food items, sale of small livestock’s, engagement in off-farm livelihood activities and migration were significant coping strategies to switch vulnerabilities. Capital level of households can mainly determine household’s level of vulnerability and their coping strategies to achieve sustainable livelihood activities.

Table 5. Coping strategies adopted by rural farm households

In addition, focused group discussants and key informants demonstrated that households design different mechanisms to cope with the vulnerability of their livelihoods. Even when households follow different coping mechanisms, being the sole livelihood becomes a challenge to their resilience and coping skills. All livelihoods are subject to vulnerabilities, but practicing diverse livelihood activities is an opportunity to reduce the impact of vulnerabilities on specific livelihoods. Because households allow for different livelihoods, the impact of vulnerabilities in one activity may not pose a challenge for another activity. Thus, there is an opportunity to address the impact of vulnerabilities on a single livelihood activity by allowing for multiple livelihood opportunities.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Vulnerabilities of livelihoods are encompassed with multidimensional problems exhibited differently by different environmental situations in terms of social, economic, physical, and institutional specification of peoples in a given area. Based on the findings of the study, vulnerability contexts were identified and ranked within the nature and type of livelihood activities performed by rural farm households. Crop diseases like root rot of pepper, and shortage of farm land were the first and second ranked problems in crop production, respectively. For crop production both natural and human induced factors were largely threatens crop-based livelihood activities. Whereas, vulnerability situations of livestock production were insufficient grazing land was the critical trends that affect livestock production and productivity and it is first ranked problem of livestock production. Additionally, inaccessibility of veterinary medicine was a great challenge and second ranked problems for livestock production. Similarly, sources of vulnerability situations in off farm and nonfarm livelihood options were identified. Thus, transportation problem and it is a first ranked problem that affect their movement to different places for doing the off-farm activities and security problem, which was ranked second.

The model result showed that Sex, access to irrigation, Income, and Livestock production risk was significantly contributing for the occurrence of livelihood vulnerability and statistically significant at less than 1% probability level. Crop production risk and Total Livestock unit were also found to be significantly contributing for households being vulnerable to risks, shocks and seasonality on their livelihoods and significant at less than 5% probability level. Additionally, households that had livelihood activities which is exposed to vulnerability contexts were follow different coping mechanisms to strengthen and enhance a sustainable livelihood opportunities. Depending on the environmental and existed livelihood options households were shifted as well as diversify their livelihood activities by taking one strategy as a coping mechanism for other livelihood options.

In response to the diverse sources and drivers of livelihood vulnerabilities, rural households in the study area employed different coping strategies for their livelihoods. Also, the selection and practice of coping strategies mainly depends on their asset level and also the level of difficulty of vulnerabilities happened in the level of farm households. The coping strategies identified in the study area were diversification of off-farm livelihoods as a main coping strategy (95.4%), engaged in nonfarm livelihood activities (74%), and cultivation of drought-resistant crop varieties (63.8%) as a responsive strategy of livelihood vulnerabilities.

Based on the findings, the researcher recommends the following:

The study has identified diverse sources of vulnerability across different livelihood activities, such as on-farm, off-farm and non-farm activities. Therefore, tackling these problems is very important for small holder farmer’s livelihood activities. In turn, sector-based vulnerability reduction approach could be vital in achieving livelihood security.

The socio economic characteristics such as: sex, access to irrigation, income, and total livestock unit were significantly determine households exposure to livelihood vulnerability. Therefore, household demographics are the main driver of livelihood vulnerabilities. So that, livelihood security enhancement programs is advised to look on these sources of vulnerabilities in different livelihood practices.

The common risks such as livestock production risk and crop production risk strongly contributed to the room for happening of livelihood vulnerability. As a result, the Woreda experts should give attention to minimize risks that could be easily handled by woreda level and also, upper agricultural offices might intervene on large-scale risks.

As identified by the study, households have followed different local-based coping strategies in response to vulnerabilities. Mostly, coping strategies at household level were minimally emphasized by policy issues. Therefore, giving policy attention for local livelihood coping mechanisms and doing an integration with scientific resilience approaches could be important to improve livelihood activities and win over vulnerabilities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Negusie Abuhay Mengistu

Negusie Abuhay Mengistu is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, at Woldia University, Ethiopia. He has MSc degree in Rural Development from Hawassa University and BSc. degree in Rural Development and Agricultural Extension from Gondar University. Currently, he has been teaching several courses for Rural Development and Agricultural Extension and Agricultural Economics students. His research areas of interests are livelihood, poverty, food security, gender and agricultural extension.

Notes

1. The third administrative division of Ethiopia consisting number of Kebeles.

2. The smallest administrative unit of Ethiopia.

3. Mitad, Dist, Minichet/Genibo, Gan are local names of pottery products.

References

- Abankwah, V. (2021). Measuring livelihood vulnerability to large-scale and small-scale mining in Rural Ghana : A comparative examination of agrarian households. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 39(2), 50–20. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJAEES/2021/v39i230529

- Abeje, M. T., Tsunekawa, A., Haregeweyn, N., Nigussie, Z., Adgo, E., Ayalew, Z., Tsubo, M., Elias, A., Berihun, D., Quandt, A., Berihun, M., & Masunaga, M. (2019). Communities’ livelihood vulnerability to climate variability in Ethiopia. Sustainability, 11, 1–22. www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability

- Alhassan, S. I., & Kuwornu, J. K. M. (2018). Gender dimension of vulnerability to climate change and variability Empirical evidence of smallholder farming households in Ghana. Climate Change and Variability, 11(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-10-2016-0156

- Asian Development Bank. (2017). the sustainable livelihoods approach. Serrat, Knowledge Solutions, 5, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9

- Belay, M., Abegaz, A., & Bewket, W. (2017). Livelihood options of landless households and land contracts in north-west Ethiopia. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 19(141), 164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9727-x

- Cardona, O. D., van Aalst, M. K., Birkmann, J., Fordham, M., McGregor, G., Perez, R., Pulwarty, R. S., Schipper, E. L. F., & Sinh, B. T. (2012). Determinants of risk: Exposure and vulnerability. In D. Henri, K. Mark (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. A special report of working groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (pp. 65–108). Cambridge University Press.

- Cornish, G. E. (2020). Settling into a New Place : Livelihood recovery and belongingness of households forced to relocate in Yangon, Myanmar. Univrsity of Queensland Australia. Doctoral Thesis, (Hons 1).

- Cramer, J. S. (2007). Robustness of logit analysis: Unobserved heterogeneity and miss specified distrubance. University of Oxford Department of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2007.00445

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2007). Ethiopia demographic and health survey key findings. Addis Ababa.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2013). Population projection of ethiopia for all regions at. Addis Ababa. Wereda Level from 2014 – 2017.

- Devi, L. G., Dhirendra, V., & Mukund, A. K. (2016). The livelihood vulnerability analysis: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change a case study of livestock farming in Karnataka. India, 9(2), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.9790/2380-09221519

- DFID (Department for International Development). (2000). Sustainable rural livelihoods guidance sheet. Department for international development.

- FDRE (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia). (2018).The Second Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II) Midterm Review Report National Planning Commission, Addis Ababa

- Gravitiani, E., Fitriana, S. N., & Suryanto. (2018). Community livelihood vulnerability level in northern and southern coastal area of Java, Indonesia; IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/202/1/012050

- Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic Econometrics (Fourth ed.). United States Military Academy, West Point.

- Hosmer, D. (2000). Applied logistic regression (Second ed.). New York Wiley-Inter science Publication John Wiley & Sons, INC.

- Junquera, V., & Grêt-Regamey, A. (2020). Assessing livelihood vulnerability using a Bayesian network : A case study in northern Laos. Ecology and Society, 25(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12049-250438

- Koirala, S. (2015). ‘Livelihood vulnerability assessment to the impacts of socio-environmental stressors in raksirang VDC of Makwanpur District Nepal. Norwegian University of Life Sciences the Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric’.

- Madhuri, H., Tewari, R., & Pradip, K. B. (2018). Livelihood vulnerability index analysis : An approach to study vulnerability in the context of Bihar. Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 61. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v6i1.127

- Mengistu, S. (2017). Livelihood vulnerability and coping strategies among the Karrayu Pastoralists of Ethiopia. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 22(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2201023339

- Morse, S., McNamara, N., & Acholo, M. (2013). Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A critical analysis of theory and practice. In A.M. Mannion (Eds.), Geographical Paper No. 189.

- Osawe, O. W. (2013). Livelihood vulnerability and migration decision making nexus : The case of rural farm households in Nigeria. 4th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists. September 22-25. University of East Anglia, UK. Hammamet, Tunisia.

- Panthi, J., Aryal, S., Dahal, P., Bhandari, P., Krakauer, Y. N., & Pandey, P. V. (2015). Livelihood vulnerability approach to assessing climate change impacts on mixed agro-livestock smallholders around the Gandaki River Basin in Nepal. Regional Environmental Change, 16(4), 1121–1132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0833-y

- Shahzad, L., Tahir, A., Sharif, F., Hayyat, M. U., Ghani, N., Farhan, M., & Dogar, S. S. (2019). Socio-economic status of mountainous community ? A case study of post-earthquake ecological adaptation of balakot population. Appl Ecol Environ Res, 17(3), 6605–6624. http://dx.doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1703_66056624

- Sime, G. (2019). Rural livelihood vulnerabilities, coping strategies and outcomes: Acase study in central rift valley of Ethiopia. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev 19(3). https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.86.16815

- Sujakhu, N. M., Sailesh, R., Jun, H., Dietrich, S. V., Yufang, S., & Jianchu, X. (2019). Assessing the livelihood vulnerability of rural indigenous households to climate changes in Central Nepal, Himalaya. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(10), 2977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102977

- Takusa Woreda office of Agriculture (TWAO). (2020). Major agricultural crops produced in the Woreda on 2018/19 production year.

- Thabane, K. (2015). Determinants of vulnerability to livelihood insecurity at household level: Evidence from Maphutseng, Lesotho. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 19(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4314/jae.v19i2.1

- Thao, N. T., Dao, N. K., Tran, T. X., & Bernard, T. (2019). Assessment of livelihood vulnerability to drought: A case study in Dak Nong Province. Vietnam. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 10(4), 604–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-00230-4

- Theodrose, S. (2016). Earth science & climatic change vulnerability of smallholder farmers to climate change at Dabat and West Belesa Districts. North Gondar, Ethiopia’, 7(8), 2157–7617. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7617.1000365

- Twigg, J., Greig, B., & Lanka, S. (2001). Sustainable livelihoods and vulnerability,

- USAID (United States Agency for International Development). (2017). ‘Vulnerability assessment methodologies: A review of the literature second. Edition Vulnerability Assessment Methodologies.

- Welderufael, M. (2015). Analysis of households vulnerability and food insecurity in Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia: Using value at risk analysis. Ethiopian Journal of Economics, 23(683–2017–948), 37–78.

- WFP &CSA (World Food Program and Central Statistical Agency). (2019). Comprehensive food security and vulnerability analysis. www.wfp.organdwww.csa.gov.et

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, an introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Yamba, S., Divine, O. A., Lawrencia, P. S., & Felix, A. (2017). Smallholder farmers’ livelihood security options amidst climate variability and change in Rural Ghana. Hindawi Scientific Research, 2017, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1868290

- Yenesew, S., Eric, N., & Fekadu, B. (2015). Determinants of livelihood diversification strategies: The case of smallholder rural farm households in Debre Elias Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(19), 1998–2013. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR

- Yishak, G. (2014). Rural household livelihood strategies: Options and determinants in the case of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Social Sciences, 3(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ss.20140303.15

Appendices

Appendix 1: the results of robustness checks starring multicollinearity of logistic nature by Heteroskedasticity check

Appendix 2:

Guiding Questions for Focus Group Discussion

What are the sources of vulnerabilities on agricultural related and nonagricultural livelihood strategies?

What are the most frequently occurred vulnerabilities crop and livestock production.

What are sources of vulnerabilities in off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities?

The role of household demographic characteristics in improving livelihood activities and possibility to the occurrences of livelihood vulnerability.

Describe the context and effect of vulnerabilities in the area.

Does social relations used by farmers help to reduce vulnerability in livelihoods?

What are the households locally applied coping strategies in the area?

Appendix 3:

Key Informant Interview Guide for selected households

Describe your livelihood vulnerability contexts?

What are the sources of vulnerabilities affecting agricultural products of your household?

What factors contribute positively or negatively to your livelihood vulnerability? (Financial, technology, human, natural capital, and social ties).

What are the sources of vulnerabilities affecting off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities?

What coping strategies do your households employ during vulnerabilities?

Appendix 4:

Key informant interview for Kebele experts

What are the dominant vulnerabilities of agricultural-based livelihood activities practiced in the area?

What are the main sources of vulnerability of off-farm and non-farm livelihood activities in the kebele?

What vulnerabilities specifically characterize the Kebele?

What are the common coping strategies practiced in the Kebele?

Do you think that the coping strategies is wining power, why?

What do you think are the challenges for small holder farmers in the area?

How household’s characteristics determine livelihood vulnerability?

Appendix 5:

Key Informant Interview Guide for Woreda Agricultural Officers

Would you please describe rural livelihood vulnerabilities in the woreda?

What are the engines for the incidence of vulnerabilities in livelihoods?

Does sources of vulnerabilities are varied from one livelihood activity to another? How?

Did demographic difference and institutional factors contributes to the happening of livelihood vulnerability?

What coping strategies do the households followed during vulnerability in their livelihood?

How the woreda consider local based coping strategies?

Explain with respect to their livelihood strategies and vulnerability level (you may point in to reports from kebeles).