?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The world’s population is ageing. The problems with an ageing population are a decline in savings and uncertainty of the effect of ageing on savings over time. This paper examines the impact of the growth of the population aged 65 and above on savings in ASEAN-5. The annual gross savings and the growth of the population aged 65 and above are retrieved from the World Development Indicator database for the sampling period between 1975 to 2020. The autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimation technique is employed to study the impact of the growth in the population aged 65 and above on savings in ASEAN-5. The novelty of this study is twofold. First, this study refers to the Life Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) to examine the short and long-run effects of the growth of the population aged 65 and above on the gross savings of ASEAN-5 economies. Second, this paper evaluates a time-varying 40 + k sub-sample period to gauge the impact of an ageing population on savings over time. This paper found that the growth in the population aged 65 and above had a significant and persistent impact on the gross savings of Indonesia over time. Nonetheless, the growth of the population aged 65 and above did not affect the gross savings of ASEAN-5 in the short run. The population aged 65 and above affected the gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore the most in the long run.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The world’s population is ageing. An ageing country will face an ageing workforce and a possible decline in aggregate savings. Savings is a vital source of funds to finance consumption during old age. The problems with an ageing population are a decline in savings and uncertainty of the effect of ageing on savings over time. This paper examines the impact of the growth of the population aged 65 and above on savings in ASEAN-5. This paper found that the growth in the population aged 65 and above had a significant and persistent impact on the gross savings of Indonesia over time. Nonetheless, the growth of the population aged 65 and above did not affect the gross savings of any ASEAN-5 economies in the short run. The population aged 65 and above affected the gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore the most in the long run.

1. Introduction

The World Population Prospects reported that one in six people would be 65 and above by 2050 (United Nations, Citation2019). Although the world population grew, the number of population aged 65 and above had outnumbered children below five years old in 2018. Many counties were ageing due to increased longevity and a reduction in fertility (World Bank, Citation2016).

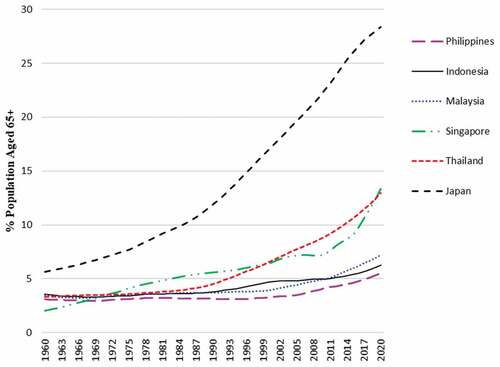

Among ASEAN-5,Footnote1 Singapore has the largest percentage of population aged 65 and above, followed by Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia. In 1960, Singapore’s population aged 65 and above was 2.04% of its total population. In 2020, the same population group was 13.35% of its total population, more than 6.5 folds of its 1960 record. Thailand’s population aged 65 and above was 3.31% of its total population in 1960. The same population group is 16.96% of its total population in 2020, almost fourfold of its record in 1960.

Malaysia’s population aged 65 and above was 3.42% of its total population in 1960. The same population group made up 7.18% of its total population in 2020, about double of its population aged 65 and above in 1960. The Philippines and Indonesia’s population aged 65 and above was 3.09% and 3.55% of their total population in 1960. The same population group made up 5.51% (Philippines) and 6.26% (Indonesia) of their total population in 2020. See, for details.

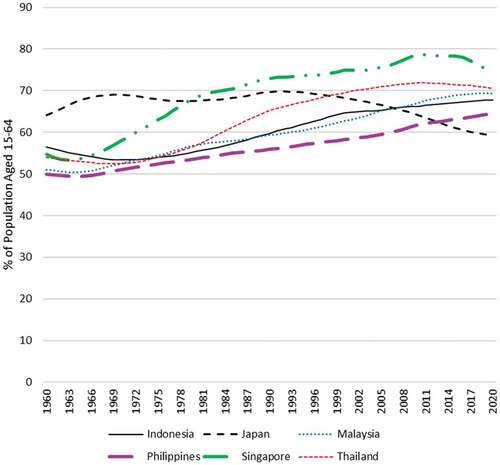

ASEAN was known for its cheap and abundant labour resources (Cui & Lu, Citation2018). However, the size of Singapore and Thailand’s population aged 15–64 years has decreased since 2011. Malaysia’s population aged 15–64 years also decreased in 2020. According to Malaysia’s National Population and Family Development Board, the prolonged covid19 pandemic will cause Malaysians to age sooner than 2030. The prolonged covid 19 pandemic has resulted in lower birth rates due to a lack of savings, fear of contracting Covid-19 and anxiety of inaccessibility to prenatal treatments. Since 2018, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines’ growth in the population aged 15–64 years has reduced. Japan recorded a noticeably reduced percentage of the population aged 15–64 years between 1960 and 2020. See, for details.

A decrease in the size of the population aged 15–64 years indicates a fewer young and productive adult labour force (Uddin et al., Citation2016). Take Japan, for instance, it is ageing fast due to its rapid increase in ageing population and decreasing population growth (Okamoto, Citation2022). An ageing Japan implies an increase in the demand for long-term care services, medical services and labour immobility (Kato, Citation2022). A summary of ASEAN-5 gross savings and other socio-economic indicators is presented in Appendix B.

The problems with an ageing population were twofold. First, the increase in the age of the labour force causes a decline in productivity and agility (Kato, Citation2022; Lee & Shin, Citation2019). An ageing population causes a decline in aggregate savings (Bussolo et al., Citation2017; Pascual-Saez et al., Citation2020) and adversely affects economic growth.

The Life Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) explains rational consumption and saving decisions (Martini & Spataro, Citation2022). Households save for future consumption, especially in old age (Oinonen & Viren, Citation2022). Based on LCH, a decrease in aggregate savings is expected due to ageing (Bussolo et al., Citation2017), but households’ confidence in their financial condition also affects their savings (Vanlaer et al., Citation2020). Lower-income households may not save as much for old age compared to financially sound households. If ageing is inevitable in ASEAN-5, it is vital to ensure sufficient savings to support consumption in later years of life.

Second, it is uncertain if the growth of an ageing ASEAN-5 affects its savings over time. The minimum retirement age for Singapore is 62 years old, with optional three years of extension for those eligible. The retirement age for Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines is 60. As people age, their demand for medical services increases. Without a steady income, medical expenses were paid from savings or financial support from other family members.

Life expectancy at birth for Singapore was 83.6 years, Thailand was 77.2 years, Malaysia was 76.2 years, Indonesia was 71.7 years, and the Philippines was 71.2 years (UNDP, Citation2020). Hence, those who retire at 65 years old in Singapore need sufficient savings to sustain their lifestyle for at least 18 years. A negative relationship between the ageing population and savings may adversely affect the lifestyle of the older population, especially those who live beyond the life expectancy age.

This paper examines the short and long-run effects of the growth in the population aged 65 and above on the gross savings of ASEAN-5 economies. Time-varying analysis of the impact of the growth in the population aged 65 and above on the gross savings of ASEAN-5 economies is studied over time.

The implication of an ageing population is reviewed in the next section, followed by the study’s research methodology, findings, and discussions. The paper ends with some concluding remarks.

2. Life cycle hypothesis

The Life Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) was specified based on the utility function to assess the impact of the consumption-income effect on an individual’s entire life cycle (Ando & Modigliani, Citation1963). Households would distribute their consumption over their lifetime through rational consumption and saving decisions. Savings in the earlier part of the life cycle is necessary to reserve adequate wealth to eventually finance consumption in the later part of life through dissaving. The preference for consumption over savings depends on household income, the rate of return of assets and the age structure of the population (Franco Modigliani, Citation1966).

The LCH utility function of Slovakia’s pension system was optimised, subject to lifecycle savings and individual welfare. The welfare optimisation model found that the pension scheme was dominant in individual welfare contribution (Balco, Citation2018). An ageing population is expected to cause a decline in aggregate savings, but a change in economic growth and reform in pension systems would affect savings more than ageing (Bussolo et al., Citation2017).

The LCH two-stage least square regression estimation found that Chinese family size and age significantly affected savings (Lugauer et al., Citation2019). An augmented LCH model estimated the impact of consumer confidence on gross household savings and discovered that confidence in household financial condition has a more prominent effect on household savings than confidence in the general economic situation (Vanlaer et al., Citation2020).

Horioka (Citation2010) stated that the LCH model could explain the dissaving behaviour of near retired and retired Japanese workers. The Japanese dissaving behaviour was mainly due to the reductions in social security benefits and increased consumption, spending, and social insurance premiums. In central Europe, its ageing population has caused a decline in aggregate savings over recent years (Pascual-Saez et al., Citation2020). Besides savings, it was suggested that investments could finance consumption during old age. As the population structure ages, a decline in the working-age population will cause economic growth to fall (Lee & Shin, Citation2019).

An autoregressive distributed lag estimation model was applied to study how GDP and real interest rate in Ghana, Togo, Burkina Faso, and Cote d’Ivoire affected gross savings. The study discovered that GDP and real interest rate positively affected gross savings. The age dependency ratio was negative but insignificant to gross savings (Abasimi & Martin, Citation2018). The age dependency ratio can be computed as the summation of the population aged below 14 years and those aged 65 and above, divided by the working-age population of 15–64 years old. The age dependency ratio did not affect the gross savings of Ghana, Togo, Burkina Faso, and Cote d’Ivoire.

The LCH explains rational consumption and saving decisions. LCH related studies argue that the ageing population reduces aggregate savings (Lee & Shin, Citation2019; Pascual-Saez et al., Citation2020), affect households’ confidence in their financial condition and their ability to save (Vanlaer et al., Citation2020), and is influenced by age dependency ratio (Abasimi & Martin, Citation2018), pension system (Balco, Citation2018) and retirement reforms (Bussolo et al., Citation2017). Besides ageing, savings is also influenced by economic growth, interest rates and inflation (Oinonen & Viren, Citation2022). Economic output and pension system reforms influence aggregate savings more than ageing (Bussolo et al., Citation2017).

It is uncertain if savings in ASEAN-5 diminish as its population ages. If ageing is inevitable in ASEAN-5, it is vital to examine the effect of the growth of the population aged 65 and above on its savings.

3. Methodology

This paper examines the impact of the population aged 65 and above on the gross savings of ASEAN-5 economies by applying the LCH framework. The data for the change in the population aged 65 and above is proxied by the growth rate of the population group aged 65 and above. Savings is represented by the gross savings rate over Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Economic activities are represented by the real GDP measured in local currency. Since ASEAN-5 is not ageing yet, this study does not include the age dependency ratio (Abasimi & Martin, Citation2018). All data are annual series, retrieved from the World Development Indicator database. The sampling period applied in this paper was from 1975 to 2020. The fundamental estimation model for this paper is defined as follows:-

where S is gross savings rate, rY is the natural log of real GDP, Pop is the growth rate of the population aged 65 and above.

The Dickey-Fuller Generalised Least Square (DF-GLS) extends the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test. The lag for DF-GLS tests is selected based on the Schwarz Bayesian criterion to test the null hypothesis of the unit root problem in each time series (Elliott et al., Citation1996). Next, the variables’ long-run relationships are examined using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) unrestricted error correction model (UECM) bounds test. The ARDL estimation can be employed for series that are I(1) as well as I(0), for both long-run and short-run analysis (Ahmed et al., Citation2021; Aslam & Sivarajasingham, Citation2021). Other advantages of the ARDL estimation include suitability for small sample size estimation and addressing any possible multicollinearity and endogeneity issues (Ahmed et al., Citation2021). The UECM in this study is stated as Equation (2).

where

The ARDL UECM Equation (2) is estimated for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. The existence of the co-integration relationship is tested by applying the F-statistic of the bounds test of the following hypothesis.

Rejection of the null hypothesis confirms the long-run co-integrated relationship. The ARDL vector ECM estimated Equation (3) as follows:-

where

Equation (3) is estimated for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. The time-varying rolling convergence estimation of the Johansen and Juselius (JJ) rank test is further employed to determine the existence of convergence during different sub-sample periods of analysis. Brada et al. (Citation2005) applied 60 observations of sub-sample to analyse their rolling convergence estimation. Due to the lack of sufficiently long time-series data, this study uses a 40 + k sub-sample and scales the trace statistics and Max Eigenvalues to 95% critical values. The value of k = 1 is the lag length determined by the Schwarz Bayesian criterion (SBC). The scaled trace statistics and Max Eigenvalues of the JJ test of more than one would indicate a rejection of the no co-integration at the 5% level.

4. Findings

The DF-GLS unit root test is conducted for each time series at constant and at constant with trend. At the 5% significance level, all time series are stationary at constant with trend after taking the first difference. At the 5% level of significance, all time series are also stationary at constant after taking the first difference, except for S-mal, the gross national savings of Malaysia. See, for details.

Table 1. DF-GLS results

S-indo is stationary at level at 1% level. Pop-mal is also I(0) at constant and trend at a 10% significance level. All other series are stationary at I(1). Equation (2) is estimated for all ASEAN-5 economies using the ARDL bounds test. The F-statistics of the ARDL bounds test rejects the null hypothesis of no co-integration for gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore at a 1% level of significance. That indicated long-run co-integration from the ageing population and real GDP on gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore. There is no significant long-run co-integrating relationship between the ageing population and the real GDP of the Philippines, Malaysia, and Thailand gross savings. See, for details.

Table 2. Bounds test

The optimum lag length for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore is lag one, based on the Akaike information criterion and Schwarz Bayesian criterion. The optimum lag length for Thailand is lag two. See Appendix C for details.

In the short run, there is no significant effect of the growth of the ageing population and real GDP on the gross savings of ASEAN-5. The Wald test is applied to model estimation for Thailand and there is no significant evidence of a short-run relationship between the growth of the ageing population and real GDP on gross savings.

The negative and significance of the error correction term is known as the speed of adjustment term (Ahmed et al., Citation2021; Özer et al., Citation2021). At the 10% level of significance, the speed of adjustment (lag of ECT-indo) is approximately 65% to restore Indonesia’s long-run gross savings equilibrium relationship after a shock. At the 1% significance level, Singapore will fully restore its long-run equilibrium relationship after a shock. There is no significant evidence that the gross savings of Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand will restore to their long-run equilibrium relationship after a shock. See, for details.

Table 3. Short-run coefficient tests

At the 1% level of significance, two positive significant long-run effects run from rY-indo and rY-sp to gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore, respectively. There are no significant long-run effects from the growth of the ageing population on gross savings of the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand. Bussolo et al. (Citation2017), (Lee & Shin, Citation2019) and Pascual-Saez et al. (Citation2020) argued that ageing caused savings to decline. The growth of the population aged 65 and above negatively affects the gross savings of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore in the long run, but the t-statistics indicate an insignificant relationship.

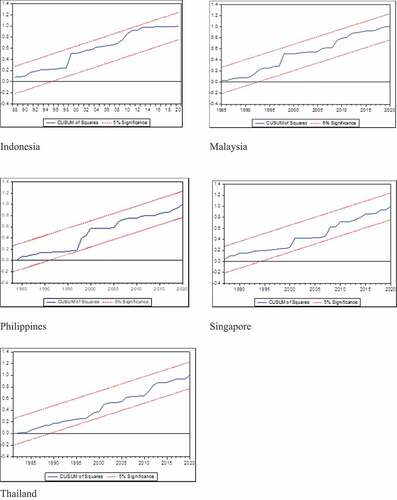

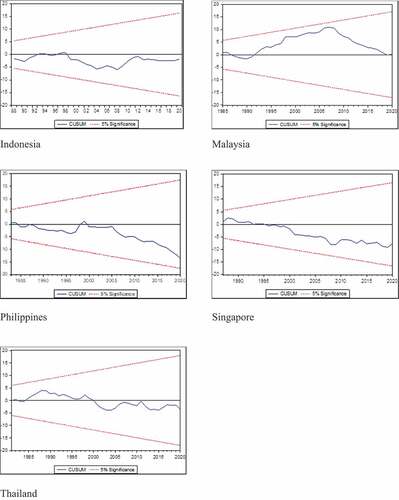

The estimated residual of Equation (3) for all ASEAN-5 had no serial correlation and heteroscedastic problems. All residuals are normally distributed, except for the Philippines. See, for details. Both Cusum and Cusum squares tests show that all coefficients are stable at the 5% significance level. See Appendix D and Appendix E for details.

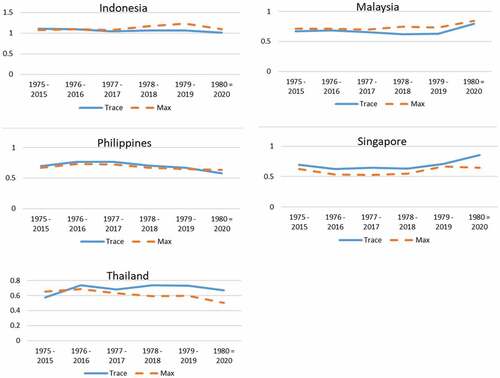

Table 4. Long-run coefficients estimates

The rolling co-integration of Pop, rY and S is analysed to detect the time-varying convergence of the variables for ASEAN-5. The Trace statistics and Max Eigenvalues are scaled to 95% critical values using n = 40 + k sample frame of 1975–2015, 1976–2016, … . 1980–2020, plus k, where k is the lag length determined by the SBC. At the 5% level, the gross savings of Indonesia indicated a gradual increase in co-integrating relationship with the growth in the population (Pop) aged 65 and economic output (rY). Except for Indonesia, no significant time-varying relationship is found between the growth of the population aged 65 and economic output for all other ASEAN-5 gross savings. See, for details.

5. Discussion and policy implication

In summary, the growth in the population aged 65 and above and economic output significantly affect the gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore. The effect is persistent over time for Indonesia. The short-run coefficient results do not show any significant evidence that the growth in the population aged 65 affects the gross savings of ASEAN-5.

The gross savings of Indonesia and Singapore adjust to restore their long-run equilibrium after a shock. There were no significant findings on the adjustment for Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand. The outcome of the findings and policy implications are discussed in detail by country.

5.1. Indonesia

There ARDL bounds test reveals that the growth in the population aged 65 and real GDP are linked to the gross savings of Indonesia. Both the growth in the population aged 65 and the real GDP of Indonesia significantly converge with its gross savings in the long run.

After a shock, Indonesia’s speed of adjustment is approximately 65% to restore its long-run gross savings equilibrium relationship. In the short run, there is no significant effect of the growth of the ageing population and real GDP on the gross savings of Indonesia.

Over time, the gross savings of Indonesia indicates a gradual increase in co-integrating relationship with the growth in the population aged 65 and economic output. The growth of the population aged 65 and economic output are linked to the gross savings of Indonesia over time.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has established an “Age-friendly Cities (AFCFootnote2) framework” to enhance greater connectivity of 8 domains, namely “community and healthcare, transportation, housing, social participation, outdoor space and buildings, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication and information” to a rewarding and enjoyable old age. The AFC has a network of 1,333 cities from 47 countries, but Indonesia is not part of its network.

Thus, Suriastini et al. (Citation2019) suggested that Indonesia could adapt the AFC framework to facilitate age-friendly city planning. In addition to age-friendly city planning, Indonesia’s Ministry of Social Affairs also includes population growth policies such as childcare benefits, maternity and paternity leaves, childcare services for working mothers, and tax relief to encourage childbirth.

5.2. Malaysia

There is no significant long-run and short-run co-integrating relationship between the growth in the population aged 65 and the real GDP on gross savings of Malaysia. There is no significant time-varying relationship between the growth of the population aged 65 and the economic output of Malaysia’s gross savings.

Malaysians have begun to age, but its growing ageing population has yet to cause any significant impact on gross savings in the short and long run. However, an age-inclusive policy is important for older people to have a positive outlook on their future to enjoy their everyday lives. Since Malaysians lack financial literacy and awareness to save for old age (Jaafar et al., Citation2018; Shariff & Ishak, Citation2021), it is crucial to implement policies to encourage savings for retirement.

Taiping and Ipoh are two cities enlisted in the WHO’s AFC framework. Malaysia should initiate an age-inclusive policy in more cities in Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia to address its growing numbers of an ageing population.

Malaysia also has a population policy, “Towards a Population of 70 Million”, to be achieved by 2100 (National Population and Family Development Board of Malaysia, Citation1984). The policy plan should be reviewed to incorporate more effective and relevant strategies to promote population growth effectively.

5.3. The Philippines

There is no significant long-run and short-run co-integrating relationship between the growth in the population aged 65 and the real GDP on gross savings of the Philippines. There is no significant relationship between the growth of the population aged 65 and the economic output of the Philippines over time.

The growth of the Philippines’ population aged 15–64 years has reduced since 2018. The Ministry of Social Services and Development ought to refer to the AFC to establish childbirth and social well-being policies to promote population growth.

5.4. Singapore

The bounds test result reveals that the growth in the population aged 65 and real GDP will significantly affect the gross savings of Singapore. The Singapore Housing Development Board has to offer affordable housing (Bozovic-Stamenovic, Citation2015) that elevates the physical, mental and social health of old age living (Seah et al., Citation2021).

In the short run, there is no significant effect of the growth of the ageing population and real GDP on the gross savings of Singapore. Over time, no significant time-varying relationship is found between the growth of the population aged 65 and the economic output of Singapore.

After a shock, Singapore would fully adjust to restore its long-run gross savings equilibrium despite ageing. Singapore’s speed of adjustment is probably due to its close vicinity to its neighbours like Malaysia, which has a pool of skilled workforce willing to emigrate to Singapore (Fong & Hassan, Citation2017; Jauhar et al., Citation2015) to replace its ageing workforce.

5.5. Thailand

There is no significant long-run and short-run adjustment of the growth of the ageing population and real GDP on the gross savings of Thailand. The Wald test verifies that there is no significant evidence of a short-run relationship between the growth of the ageing population and real GDP on gross savings. Over time, no significant time-varying relationship is found between the growth of the population aged 65 and the economic output for Thailand’s gross savings.

Thailand has relied on its religious belief to deal with ageing and caregiving to the elderly (Ratanakul, Citation2013). Establishing a community-based enterprise that includes the elderly participation is another recommendation to resolve social security and sustainability of ageing population issues (Charoenwisal & Dhammasaccakarn, Citation2022).

There are limited studies on how an increase in the ageing population in ASEAN might affect savings. Earlier studies disclosed that longevity positively impacted savings in high-income countries but the impact of the old-age dependency ratio on savings is uncertain (Wong & Tang, Citation2013). Recent studies on savings for retirement in ASEAN focused on work engagement (Guzman & Dumantay, Citation2019), determinants of private savings (Tang et al., Citation2020), mitigating adverse socio-economic spending (Kwan & Asher, Citation2022) and community support for the ageing elderly (Charoenwisal & Dhammasaccakarn, Citation2022) do not address issues related to an increase in the ageing population on savings.

6. Conclusion

There is an increase in the population aged 65 and above in ASEAN-5. The problems with an ageing population are declining savings and uncertainty of the effect of ageing on savings over time. The growth in the population aged 65 and above has a significant and persistent impact on the gross savings of Indonesia over time. Nonetheless, the current growth in the population aged 65 does not affect the gross savings of ASEAN-5 in the short run.

Among ASEAN-5, the growth of the population aged 65 and above affects Indonesia and Singapore the most in the long run. There is no evidence that the growth in the population aged 65 and above changes the gross savings of Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand.

Some policy implications include adapting to the AFC framework for Indonesia (Suriastini et al., Citation2019), Malaysia and the Philippines to facilitate an ageing friendly city planning. Singapore could promote a purposeful old age living environment that is physically, mentally and socially healthy (Seah et al., Citation2021). Thailand could establish a community-based enterprise that includes elderly participation (Charoenwisal & Dhammasaccakarn, Citation2022).

All ASEAN-5 countries must establish childbirth and social well-being policies to promote population growth. Malaysia’s 70 Million population policy should be reviewed and reintroduced with relevant strategies to promote population growth effectively.

The limitation of this study is the unavailability of the breakdown of the population aged 65 and above. A detailed breakdown of the population age would provide greater insight into the impact of different categories of the aged population on a country’s gross savings. Future research that studies the connection between different aged population and their savings would be able to recommend policy plans to meet the demand for transfer payments and health-related services of their ageing population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hway-Boon Ong

Dr. Ong Hway Boon is an Associate Professor at Multimedia University, Cyberjaya campus. She earned her M.Sc. (Economics) from the University Putra Malaysia, MPhil in Banking from MMU and Ph.D. in Financial Economics from the University Putra Malaysia. Her areas of research interest are money, banking and social economics.

Notes

1. The founding members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nation (ASEAN) were Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. At present, ASEAN consists of ten member countries, which includes Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. The geographical boundary of the study area is provided in Appendix A.

2. The AFC was established in 2010 to address ageing communities in cities globally. Details about AFC are available at https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/age-friendly-practices/

References

- Abasimi, I., & Martin, A. Y. A. (2018). Determinants of national saving in four West African countries. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 10(5), 67. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v10n5p67

- Ahmed, Z., Zhang, B., & Cary, M. (2021). Linking economic globalization, economic growth, financial development, and ecological footprint: Evidence from symmetric and asymmetric ARDL. Ecological Indicators, 121(October), 107060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107060

- Ando, A., & Modigliani, F. (1963). The “Life Cycle” hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. The American Economic Review, 53(1), 55–21.

- Aslam, A. L. M., & Sivarajasingham, S. (2021). The inter-temporal relationship between workers’ remittances and consumption expenditure in Sri Lanka. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 37(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-03-2020-0030

- Balco, M. (2018). Application of the lifecycle theory in Slovak pension system. Ekonomický Časopis, 66(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/mt-1999-417-807

- Bozovic-Stamenovic, R. (2015). A supportive healthful housing environment for ageing: Singapore experiences and potentials for improvements. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 25(4), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2015.1116195

- Brada, J. C., Kutan, A. M., & Zhou, S. (2005). Real and monetary convergence between the European Union’s core and recent member countries: A rolling cointegration approach. Journal of Banking and Finance, 29(1), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.06.024

- Bussolo, M., Schotte, S., & Matytsin, M. (2017). Accounting for the bias against the life-cycle hypothesis in survey data: An example for Russia. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 9, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2017.03.001

- Charoenwisal, R., & Dhammasaccakarn, W. (2022). Ageing society development strategy from a marginalised elderly group in Southern Thailand. Development in Practice, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2021.2013775

- Cui, Y., & Lu, C. (2018). Are China’s unit labour costs still competitive? A comparison with ASEAN countries. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature, 32(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/apel.12217

- Elliott, G., Rothenberg, T. J., & Stock, J. H. (1996). Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica, 64(4), 813. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171846

- Fong, T., & Hassan, Z. (2017). Factors contributing brain drain in Malaysia. International Journal of Education, Learning and Training, 2(2), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.24924/ijelt/2017.11/v2.iss2/14.31

- Guzman, A. B., & Dumantay, M. C. F. (2019). Examining the role of future time perspective (FTP) and affective commitment on the work engagement of aging Filipino professors: A structural equation model. Educational Gerontology, 45(5), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1622243

- Horioka, C. Y. (2010). The (dis)saving behavior of the aged in Japan. Japan and the World Economy, 22(3), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2010.02.001

- Jaafar, M. H., Villiers-Tuthill, A., Sim, S. H., Lim, M. A., & Morgan, K. (2018). Validation of the brief ageing perceptions questionnaire (B-APQ) in Malaysia. Aging and Mental Health, 24(4), 620–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1550631

- Jauhar, J., Ghani, A. B. A., Joarder, M. H. R., Subhan, M., & Islam, R. (2015). Brain drain to Singapore: A conceptual framework of Malaysians’ diaspora. Social Sciences (Pakistan), 10(6), 702–711. https://doi.org/10.36478/sscience.2015.702.711

- Kato, R. R. (2022). Population aging and labor mobility in Japan. Japan and the World Economy, 62(February), 101130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2022.101130

- Kwan, C. Y., & Asher, M. G. (2022). Managing shocks in Singapore’s ageing and retirement arrangements. Policy Studies, 43(2), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1634189

- Lee, H. H., & Shin, K. (2019). Nonlinear effects of population aging on economic growth. Japan and the World Economy, 51(December), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2019.100963

- Lugauer, S., Ni, J., & Yin, Z. (2019). Chinese household saving and dependent children: Theory and evidence. China Economic Review, 57(September), 11–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.08.005

- Martini, A., & Spataro, L. (2022). The contribution of carlo casarosa on the forerunners of the life cycle hypothesis by franco modigliani and richard brumberg. International Review of Economics, 69(1), 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-021-00386-w

- Modigliani, F. (1966). The life cycle hypothesis of saving, the demand for wealth and the supply of capital. An International Quarterly Social Research, 33(2), 160–217.

- National Population and Family Development Board of Malaysia. (1984). Towards a population of seventy million.

- Oinonen, B. S., & Viren, M. (2022). Why do households save ? 1–7.

- Okamoto, A. (2022). Intergenerational earnings mobility and demographic dynamics: Welfare analysis of an aging Japan. Economic Analysis and Policy, 74(20), 76–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.01.006

- Özer, M., Canbay, Ş., & Kırca, M. (2021). The impact of container transport on economic growth in Turkey: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Research in Transportation Economics, 88(November), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.101002

- Pascual-Saez, M., Cantarero-Prieto, D., & Pires Manso, J. R. (2020). Does population ageing affect savings in Europe? Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(2), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.07.009

- Ratanakul, P. (2013). Reflections on Aging in Buddhist Thailand. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging, 25(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2012.738582

- Seah, B., Espnes, G. A., Ang, E. N. K., Lim, J. Y., Kowitlawakul, Y., & Wang, W. (2021). Achieving healthy ageing through the perspective of sense of coherence among senior-only households: A qualitative study. Aging and Mental Health, 25(5), 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1725805

- Shariff, N. S. M., & Ishak, W. W. M. (2021). Statistical analyses on factors affecting retirement savings decision in Malaysia. Mathematics and Statistics, 9(3), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.13189/ms.2021.090305

- Suriastini, W., Buffardi, A. L., & Fauzan, J. (2019). What prompts policy change? Comparative analyses of efforts to create age-friendly cities in 14 cities in Indonesia. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 31(3), 250–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2019.1589889

- Tang, C. F., Tan, E. C., & Chua, S. Y. (2020). What drives private savings in Malaysia? Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(2), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1508442

- Uddin, G. A., Alam, K., & Gow, J. (2016). Population age structure and savings rate impacts on economic growth: Evidence from Australia. Economic Analysis and Policy, 52, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2016.08.002

- UNDP. (2020). The next frontier: human development and the anthropocene. In Human Development Report 2020.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. (ST/ESA/SER.A/423). https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf

- Vanlaer, W., Bielen, S., & Marneffe, W. Consumer confidence and household saving behaviors: A cross-country empirical analysis. (2020). Social Indicators Research, 147(2)), 677–721. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02170-4

- Wong, B., & Tang, K. K. (2013). Do ageing economies save less? Evidence from OECD data. International Journal of Social Economics, 40(6), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068291311321875

- World Bank. (2016). Live long and prosper: Aging in East Asia and Pacific, 287.

Appendix A.

Geographical boundary of ASEAN-5

Appendix B.

Socio-economic indicators of ASEAN-5

Appendix C.

Lag selection

Appendix D.

Cummulative sum (cusum) charts

Appendix E.

Cumulative sum of squares (cusum square) charts