?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The tourism industry often views heritage as a commodity rather than a way of conserving resources. This paper clarifies the challenges faced by Community-Based Tourism (CBT) from the perspective of heritage resources consumption caused by tourism development with the aid of a countrywide database. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis are performed on 549 communities endorsed by government and non-government agencies. The results reveal three major clusters: nature-based ecotourism, group of buildings and historical district-based shopping tourism, and cultural landscape-based agritourism. These clusters share resource-based interests and perspectives on tourism management. Each cluster exhibited the identity of CBT, was associated with local management, and represented how individuals interpret their heritage. This data helps and supports tourism policy changes at both local and national level.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Community-Based Tourism (CBT) in Thailand is used to promote community economies and community-based conservation of natural and cultural resources. These communities rely on heritage resources to express and interpret their identity, which reflects a mixture of influences and results in the creation of a unique tourism activity. This study examined tourism communities scattered throughout Thailand to reveal the pattern of heritage consumption in CBT by integrating geospatial and statistical methods. This data could help support tourism policymaking at both local and national levels.

1. Introduction

The tourism industry requires a variety of resources to meet the demand from consumers for both cultural and natural heritage. Consequently, heritage has become a prominent feature of modern-day tourism (Timothy, Citation2011). Natural forests, mountains, rivers, seas, places of scenic beauty, and historical sites are mainly used as tourist attractions, while culture and the Thai way of life are brought to the tourism market as cultural products. Therefore, these resources are attractive factors for persuading tourists to visit the various heritage sites inherited across generations and requiring preservation to ensure they can be passed down to the next generations.

The establishment of CBT began by utilizing local heritage resources through the development of tourism communities to improve their living standards in a viable way (Boonratana, Citation2010; Dhiana & Winanto, Citation2018). Hence, these resources not only made destinations more appealing but also generated income for the community (Baedcharoen, Citation2006). Furthermore, the Government of Thailand hopes that CBT will help the tourism industry grow while balancing the available resources through creativity to ensure tourist satisfaction and public interest to achieve long-term suitability and equity (”Ministry of tourism and sport,” Citation2020). This has made CBT one of the most popular tourism development schematics for the country.

However, among the 3,273 tourism communities scattered throughout the country (Community Development Department, Citation2017), there has been very little discussion on the wider area of CBT and the utilization of resources. CBT models tend to focus on economic and social value (Zielinski et al., Citation2020) and the available heritage resources by assessing tourism management plans. Studies on tourism management in any CBT area usually provide an outstanding example of public involvement and participation in community development (Hall & Richards, Citation2000; Johnson, Citation2010; Nandita & Ronnakorn, Citation2003; Ohe, Citation2020; Sharon, Citation2010; Yanes et al., Citation2019; Zielinski et al., Citation2020). Therefore, to bridge the study gap, this paper highlights the importance of heritage resources in the tourism community by proposing the establishment of a countrywide database to clarify CBT based on heritage utilization and consumption. This may be the first step toward improving tourism development using a resource-based approach. The results provide a new definition and additional knowledge on heritage tourism in CBT areas and ideas for strengthening policy implementation and decision-making in this setting.

1.1. Heritage resources in CBT operations: local identity reflection

The concept of sustainable tourism is based on promoting socio-cultural authenticity and the optimal use of natural and environmental resources (United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization, Citation2005). Even though the definition of a sustainable community has been widely discussed, sustainability in the community tends to be related to place and time. Total sustainability can be defined as the overlap of natural, economic, and social dimensions to ensure they meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Sverdrup & Svensson, Citation2002). Dixon (Citation2012) also states that sustainable communities are places where people want to live and work—now and in the future. It is believed that sustaining CBT could ensure local stakeholders have the opportunity to fulfill their social and financial requirements over time (Han et al., Citation2019; Lo et al., Citation2020; Pham Hong et al., Citation2021). Within the concept of tourism, cultural heritage and natural environment are major tourist attractions (Jugmohan et al., Citation2016). These tourist attractions have been inherited across generations and worthy of preservation. Verovšek et al. (Citation2016) mentioned that the relationship between a tourism destination and the local residents reflects the integrity of the interpreted identity. In this sense, heritage resources are manifested in tourism destinations and reflected in local identity. It is critical that an alternative way is considered, which takes a more community-driven approach toward sustainable development. Thus, this study focuses on heritage values at all levels within the tourist development schematic rather than only the immediate requirements of visitors and the tourism industry (Ruhanen & Whitford, Citation2019).

The concepts of heritage, culture, and identity are closely aligned and strongly influence heritage tourism (Di Pietro et al., Citation2018). The identity of a place is presented and interpreted through tangible (i.e., architecture, skyline, urban space and circulation patterns, views and scenery, small elements, and vegetation) and intangible forms (i.e., city function, name of place, social events/traditions, story/history, lifestyle, food, and local wisdom/beliefs; Sirisrisak, Citation2007). Systematic interpretation and presentation can effectively communicate information and the value of a place to the public and provide visitors with a positive, valuable experience (Liu & Lin, Citation2021). These tools involve stakeholders and local actors facilitating civic engagement and helping communities to develop visions and identify key aspects of places and landscapes (Amoruso & I. R. Management Association, Citation2016).

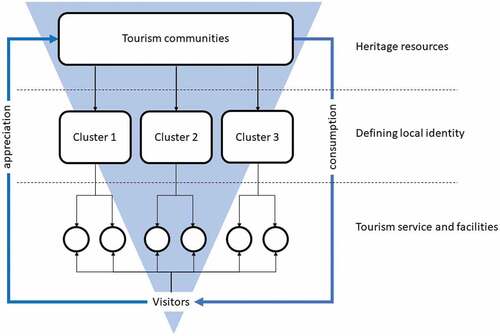

However, there is a dearth of studies on the establishment of heritage resources for CBT to support tourism programs and activities, despite heritage playing an important role in activity development for visitors through local identity and the tangible and intangible characteristics of a place. However, a critical issue in using heritage resources for CBT is that tourism and heritage management embrace different mandates and focuses. Particularly, an inappropriate economic activity may damage heritage resources due to overuse by tourists or commoditization, trivialization, and standardization (Ho & McKercher, Citation2004). The key linkage between both fields lies in the interpretation of authenticity (Dolezal, Citation2011; Li, Citation2003). Thus, authenticity could refer to both the power of a place and the heritage consumption dilemma. Power distribution represents an authentic scene to visitors; whether authentic or not, it satisfies their needs. However, individuals may perceive authenticity differently according to how the site is presented and used (Su et al., Citation2020). The definition of authenticity has changed over time, with its paradigm in the modern-day moving away from original material to the acknowledgment of multicultural starting points and living traditions (Niskasaari, Citation2008). However, the definitions of authenticity still revolve around the quality of values (ICOMOS, Citation1994). The perception and utilization of heritage resources in CBT can be investigated using a classification method ().

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Classification: interpretation of CBT’s identity

In tourism, market segmentation refers to the classification of consumers into different market segments (Dolnicar & Kemp, Citation2009). Each of the segments represents a homogeneous group within a larger market (Smith, Citation1956). The segmentation criteria may be based on a single visitor’s characteristics, a larger set of visitors’ characteristics involving the environment, or expenditure patterns (Dolnicar et al., Citation2018). The segmentation of CBT destinations reflects their perspectives and purposes.

The tourism strategies in Thailand can be divided into several typologies for promoting and supporting the tourism market. Focusing on local resources, the TAT classified 12 types of attractions based on the activities and environment destination: ecotourism, arts and sciences educational standards, historical, natural, recreational, cultural, hot springs, beaches, waterfalls, caves, island, and rafting (Effinity, Citation2016). However, this classification defined local resources as another tourism product, with no differentiation among groups within these categories. In certain cases, the definition of their features was unclear, especially regarding the recognition of tourism patterns, although they shared similar local features with neighboring categories.

Another typology of CBT in Thailand is the pattern of tourism in the community (TiC) as a consequence of promoting cultural attractions and nature-based tourism in the 1990s (Leksakundilok, Citation2004). This classification defined tourism in rural communities based on the most attractive features, such as culture, minority groups, traditions and events, pilgrimages, agro-based, and nature-based. However, these patterns tend to be observed as combined, without a clear distinction between each group. Again, the attraction’s local resources seem to be used as a tourism commodity. This controversial issue raises questions about the CBT program, which considers heritage as a commodity rather than a means of conserving natural and cultural resources.

There is a gap in CBT research from the systematic review perspective, which, if filled, would advance community stability and sustainability (Jakkrit & Dachanee, Citation2018). This study emphasizes the heritage resources and tourism activities by conducting a systematic overview of heritage resources for CBT to incorporate visitors’ experiences through the local identity to clarify the characteristics and features of tourism communities. To drive communities toward effective tourism management, this paper classifies them into meaningful groups to provide accurate data for CBT management by integrating geospatial and statistical methods. The relationships between heritage resources in CBT are examined according to their contexts, usage, reflection of local identities, and community preparation for social and environmental change.

2.2. Variables for defining local heritage in CBT

The first step in developing sustainable tourism is to define the local heritage since this aspect must be considered to assess the suitability of the attraction for tourism development (Jones et al., Citation2007). Thus, this analysis focuses on the relationships among heritage resources, tourism services, and facilities in CBT, classifying similar community clusters based on their attributes. A conceptual framework is used to define the scope of the subject matter in this study by identifying heritage resources, tourism service, and facility indicators. Under this conceptual model, visitors can consume heritage through the tourism process and, subsequently, gain a better understanding and appreciation of the site ().

The government implemented an advocacy tool for community tourism in 2017 by promoting CBT activities and products under the “OTOP Inno-Life Tourism-Based Community” scheme (Pratomlek, Citation2020). With the support of the Designated Areas for Sustainable Tourism Administration (DASTA), Tourism Agency of Thailand (TAT), Community Development Department (CDD), and Ministry of Interior Affairs, use of the CBT approach is increasing significantly. Throughout Thailand, 3,273 communities are associated with tourism-oriented products and services.

The samples were selected based on the documentation grantee of proper community-based management as a representation of nationwide CBT. From 2017–2020, 549 communities throughout Thailand had their programs endorsed by government and non-government agencies (Table ). The development of these CBT programs created opportunities and challenges for local individuals who had to adopt various tourism standards and different means of approaching tourism management. However, the programs imposed no limit on tourism community participation regarding the development and promotion of tourism attractions. Among the communities, 214 participated in more than one program (maximum of eight programs each). The selected tourism community sample represents all the CBT sites across Thailand, acknowledged by both government and non-government agencies.

Table 1. Samples taken from the 549 community-based tourism programs

Heritage resources indicators (Table ) were expanded through the World Heritage Convention, featuring three domains. Ten measurements were used to assess the heritage resources at tourist destinations to ascertain the complexity of the tourism community setting (Hua, Citation2010; Kurniawan et al., Citation2021; Petti et al., Citation2020). These heritage properties were the main resources for tourism development and consumption, providing both a tourist attraction and raw material for the tourism content in the area.

Table 2. Heritage resource indicators

The availability of tourism services to accommodate and support visitors to the site was assessed, regardless of whether it is a direct tourism destination. The tourism services and facilities indicated in Table reveal the utilization of heritage resources (Buhalis, Citation2000; Guilherme & Alexandre Panosso, Citation2017; Pelasol et al., Citation2012). These key indicators are used to measure the appearance of the built environment and its ability to meet the basic needs of local residents and visitors while positively influencing the visitor’s perception of the tourist destination (Specht, Citation2014). The growing trend in cultural tourism has created a strong link with the construction of iconic structures to meet the demand from visitors to learn more about the culture and lifestyles of people in a particular area, such as museums, art galleries, and iconic architecture, elaborating the value of the site and stimulating the economy of the community (Zukin, Citation1995). However, the impact of the built environment on tourism potentially causes irreversible, undesirable effects on the landscape and heritage.

Table 3. Tourism service and facility indicators

2.3. Analysis methods

The sampling method provided a complete list with no errors. Data collection was performed by collecting physical data through a rapid survey at the community level. By recording the physical conditions and collecting and evaluating query data from binary-dependent variables, the actual conditions, and validity of the properties could be assessed. Quantitative assessment was carried out by conducting a statistical analysis of heritage resources, the tourism thematic, programs and activities, and tourism services and facilities. The hierarchical clustering was defined as the n × p data matrix, where n refers to the tourism community and p the previously mentioned variables by a decomposition S(k) of set n communities to k certain clusters (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, Citation1990; Trebuňa & Halčinová, Citation2013)

The clustering method employed the Euclidean distance and complete linkage to find the element farthest apart. The two clusters and

, denoted

(

,

), are defined as

, where

refers to the distance between elements x and y (Krznaric & Levcopoulos, Citation2002). The results obtained from the hierarchical clustering identified the data pattern in order, classifying the relationships among heritage resources, the tourism thematic, programs and activities, and tourism services and facilities into groups or subgroups. Identical tourism communities were classified into the same group for analysis; members of the same group shared the same characteristics (). Once the data was explored by cluster analysis, multivariate principal component analysis (PCA) was used to interpret the pattern complexity in tourism communities. The basic equation of PCA involves a data matrix, X, which consists of

observation communities on

variables. These values define pn-dimensional vectors

, …,

, then ith principal component, Zi is component score. Thus,

…

, where

is a component loading a1,a2,…,ap (Cornish, Citation2007; Sratthaphut et al., Citation2013). All loadings (and scores) presenting in each principal component were used for data interpretation. Then, the analysis and qualitative assessment are discussed later in this paper.

2.4. Social and economic impact evaluation

The evaluation fulfilled the limitation of CBT research concerning the monitoring and management of the tourism community’s utilization and consumption of natural and cultural heritage resources overall. This study contributes to the countrywide macroscale analysis of heritage resources consumption in the tourism community throughout Thailand to encode the association of resources, environmental and cultural features, tourism activities and services, and physical structures. All these data are in the form of fragments which provide an incomplete picture, but by integrating these fragments, the study can be further expanded to cover the whole country and construct a system in which policymaking, medical care, engineering, and technology can be merged together (Ali et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the results of this study reveal that separate tourism communities can be categorized into relevant groups based on their heritage consumption, potentially helping to contextualize policy implementation and management at both the local and national level. Although data classification could help to support tourism policy changes, the measurement of strong correlations may create a political backlash and an aversion to political decisions based on data (Höchtl et al., Citation2015). However, for the sake of community tourism development, the government agencies and independent organizations involved could apply the findings of this research during the policymaking process to promote and support community tourism while preventing a negative impact on local heritage resources.

3. Results

3.1. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis

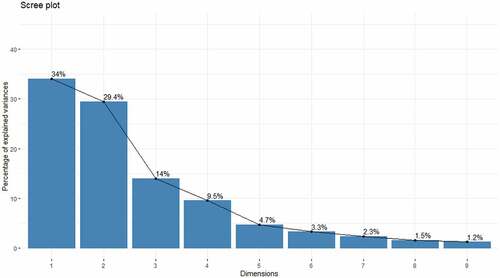

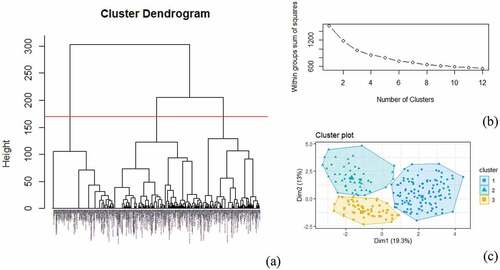

The results of hierarchical clustering revealed similarities in data distribution patterns among 549 tourism communities. The elbow method was used to determine the optimal clusters (k) and interpret and validate the data clusters. As a result, three major clusters were identified based on their distinguishing features in the dataset (Figure ), sizes 230, 149, and 170. The cluster sets were used as target variables in the principal component analysis to identify the features.

Figure 4. (a) Dendrogram showing the three identified clusters. (b) Scree plot showing a slow decrease in inertia after k = 3. (c) Visualized k-means cluster plot.

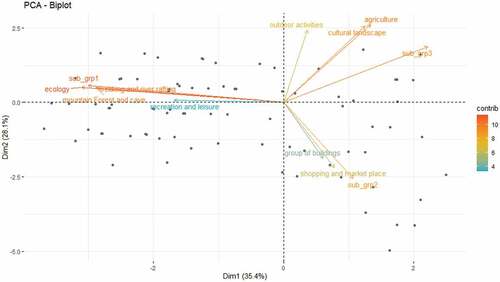

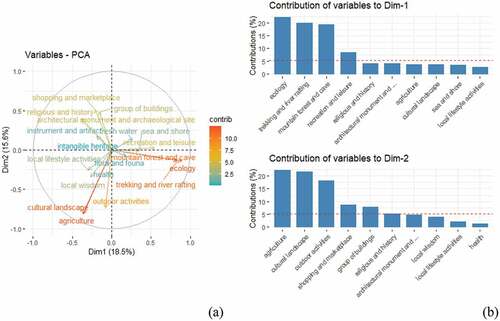

This survey dataset contained nine variables of heritage resources and the constituents of ten CBT programs and activities presented in-situ. To simplify the descriptions for further analysis, PCA was implemented to reduce the dimensionality of data. The variables making the most contribution are highlighted on the bar plot (Figure ). The bar plot contribution variance of row/column referenced by a dashed line corresponds to the expected average percentage of the explained variance, namely 5.2%. For a given dimension, any row/column with a contribution larger than this cut-off reference line could be considered important in contributing to the dimension when the variables with low contribution were removed to simplify the overall analysis. The data were then reduced from 19 to nine variables.

Figure 5. The highest contribution of variance to the Dim1 and Dim2 correlation circle (a) and PC contribution bar plot on 19 variables (b). Ecology; trekking and river rafting; mountains, forest, and caves; recreation and leisure in Dim-1; agriculture; cultural landscape; outdoor activities; shopping and marketplace; group of buildings and historical districts in Dim-2.

The visualizations indicate that three dimensions tend to increase together when the proportion of variance-explained criteria implemented using the number of principal components for a valid construction was 70% for less than 30 variables analyzed (Stevens, Citation2002). The screen plot using the elbow point at the first three PCs captured 77.4% of the variance (Figure ).

Principal component analysis was performed using psych R packages (Revelle, Citation2021) in varimax rotation of the full dataset on n = 549 samples in nine variables plus three targeted clusters, showing correlation coefficients for the variables loaded on the single principal component. The results of the principal component analysis revealed three component indexes for three identified clusters. The component correlations were at least 0.4 (p value ≤ 0.05) and considered substantial reference points for interpretative purposes. Next, the component loading was removed for a loading ≤0.40 (Table ). The interpretation of the PCI for the values is described in the following section.

Table 4. Principal component index. Numbers indicate the strength of the correlation, where over 0.4 is considered important for defining the principal component. Asterisk marked components (*) show the heritage-related factors

The principal component analysis shows the loading of the sample clusters based on their similarity (Figure ). The black dots are the samples, while the lines correspond to the eigenvectors of the principal components. The assigned cluster variables led by Sub_grp2 and Sub_grp3 have positive values in Dim-1 axis; the opposite Sub_grp1 is negative, while the Dim-2 axis Sub_grp2 and Sub_grp3 have positive values; Sub_grp2 is negative. The remaining component indexes, based on their values, are given to each side. The variables on the same side approximate the variance of the value according to its similarity. The partitioning of Sub_grp1, Sub_grp2, and Sub_grp3 in the principal component are clear. Sub_grp_1 strongly correlates with the variables of ecology, trekking and river rafting, mountains, forest, caves, recreation, and leisure. Sub_grp_3 correlates with the variables of agriculture, cultural landscape, and outdoor activities. The group of buildings and historical districts, shopping, and marketplace variables correlate with Sub_grp_2.

4. Discussion

Although differences in heritage usage and tourism activities were identified between the three emerging clusters, they shared resource-based interests and perspectives on community management. In contrast to commodification-based classification, the resulting clusters responded to CBT’s thematic, while activities bonded to local heritage resources. This classification might be described as being similar to the theme of heritage tourism (Nicholls et al., Citation2004), with community identity or inheritance categorized into three approaches: natural, cultural, and built heritage. However, their classification has typically been based on the heritage attraction of individual sites, areas, routes, corridors, and trails as tourist destinations. As destinations became more complex, it has been frequently overlooked that tourist products represent a combination of individually produced products and services (Buhalis, Citation2000).

Additionally, each derived cluster revealed that the local community, both directly and indirectly, stimulated the utilization of heritage resources by CBT operators to develop tourism schematics in their settings. To reify the description of each cluster, it was described by its component features. The results of the principal component analysis and qualitative assessment were assessed to extract the main characteristics of heritage resources and tourism activities. The combination of clusters depicts the relationship between heritage and its exploitation in community tourism.

The principal components led by Sub_grp1 were based on the ecological and recreational thematic of tourism in a natural heritage resource setting (especially geological). Conveying the ecological values of sites requires a strong orientation toward visitors’ needs and an ideological commitment to the environment (Uriely et al., Citation2007). Thus, communities tend to offer trekking and river rafting tours in and around the village with a local interpreter. This cluster is described as nature-based ecotourism and represents the majority of the population involved in Thailand’s tourism community, with 230 sampling clusters. The trend of ecotourism started as a consequence of an increase in tourism during the 1980s under the alternative tourism schematic (Yanapa et al., Citation2020) and social and community values.

The nature-based ecotourism cluster represents an abundance of natural resources, and communities actively use them in their CBT operations. Communities offer their natural resources and social traditions to visitors. In these natural settings, there is a controversial connection between tourism income and natural environmental quality. Income from tourism causes communal resource management systems to decay, thereby accelerating environmental degradation (Buckley, Citation2011). This phenomenon forced natural heritage resources to become consumable commodities through tourism activities, although there is always a mediator between consumers and products; someone who delivers a message of authenticity. This authenticity is a pivotal component in experiencing heritage as interpreted by an individual and social culture (Park et al., Citation2019).

Due to the effectiveness of tourism promotion since the 1980s, the image of heritage tourism in Thailand continues to be led by the cultural heritage sector, from the Golden Grand Palace to the secular presence of the Buddhist faith in a small provincial town and hill tribe minorities, although authenticity has not yet been addressed (Peleggi, Citation1996). However, the CBT is able to offer the essence of an authentic and often exotic rural village through actually traveling to places (Sin & Minca, Citation2014). Thus, CBT needs to create interactions between the host and visitor through participation in tourism activities that lead to a deep understanding of the community’s roots (authenticity). Cultural heritage in tourism is emphasized by Sub_grp2 and Sub_grp3.

The components led by Sub_grp2 are described as a group of buildings and historical district-based shopping tourism cluster because communities offered individuals the opportunity to acquire goods in a group of buildings and historical setting. This cluster consists of 149 vernacular commercial communities, considered to be one of the important cultural resources in the socio-cultural and local economic development. This cluster is an indication of the social, cultural, and economic prosperity of the past. Most buildings were built more than 100 years ago and formed into Chinese settlements with the cultural transmission of housing, trading, and services. A better understanding of tourist shopping experiences at local markets would be beneficial to local stakeholders (Sangkaew & Zhu, Citation2020). The income earned from tourism could be distributed to the local economy (Somchan, Citation2019). Therefore, traditional foods, cultural dwellings, and the expression of a physical built environment represent the concept of nostalgic tourism activities to increase the shopping experience of visitors.

The components led by Sub_grp3 represent the communities offering lifestyle activities with local wisdom as the main program in a cultural landscape setting. Thus, this cluster is described as the cultural landscape-based agritourism cluster, with 252 clusters representing the important role of the cultural landscape in creating tourism activities. The cultural landscape in the community might include activities carried out by its inhabitants: the natural processes of all biological species, including humans (Kaya, Citation2002). The interaction between humans and nature provides the landscape components. Paddy fields dominate Thailand’s river basins. The crisscross watercourse, rice culture, and associated communities represent the majority of the cluster population, mostly located in the central plains and northeast area (Yodsurang et al., Citation2015). Thus, this cluster highlights the local activities and their effect on the actual setting rather than the built heritage resources, e.g., palaces, temples, and pagodas. This cluster also shows the linkages among individuals, nature, and culture.

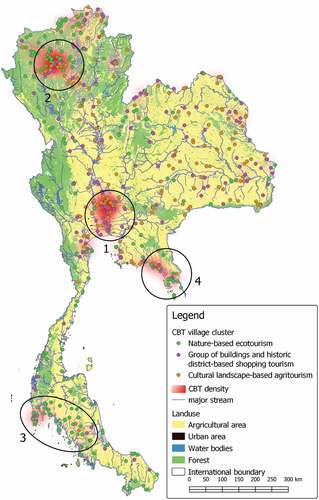

The rapid survey reveals that tourism communities are scattered throughout the country (Figure ). An overview of the tourism communities’ spatial characteristics provides an observation schematic of heritage-based classification. The heat map reveals four unique groups of tourism communities by location. The tourism communities are densely grouped in the central region, Chiang Mai and the mountainous area, Phuket and the Andaman shoreline, and the far-east Thai gulf shoreline. Since CBT is optional, it is considered a platform for the local community to share the benefits of the larger-scale tourism industry; these clusters are located close to the country’s most popular tourist destinations. Seemingly, the tourism community being attached to the main tourist routes helps to distribute tourism benefits to the local communities.

Figure 8. Location of tourism communities. Base map: Thailand land use from Landsat TM satellite image in 2000 (Royal Forest Department of Thailand, Citation2001).

The cultural-based tourism clusters in the central region (1), where the World Heritage Site of Ayutthaya is located, contain numerous archaeological sites, depicting the nation’s past glory and surrounded by a vast rice field and crisscrossed canal system which are still in use. Since the area is not far from Bangkok, visitors are attracted to the rural village culture and impressive scenery. The tourism community in this area offers visitors a cultural-based tourism program. Tourism activities incorporate the cultural landscape and surrounding rice fields into a boat trip along the canal, which are some of the most popular activities.

The CBT density in and around Chiang Mai and the mountainous area in the northern part of Thailand (2) provides another CBT hub for the country. Chiang Mai is known as a UNESCO Creative City of Craft and Folk Art, and its handicraft culture and indigenous industrious scene are emphasized in tourism programs. Its surrounding mountainous area and hilltop landscape, as well as the local culture and indigenous plantations, help to create the unique scenic beauty of the northern villages. Traveling to an ethnic setting allows tourists to experience minority cultures and their livelihoods, combining adventure and ecotourism (Weaver, Citation2002). Besides attractions, a range of authentic crafts involving heterogeneous products are on offer by minorities and hill tribes. However, mass tourism has resulted in some places losing their authenticity (Husa, Citation2020). The complexities of authenticity include the attribution of objects, rituals places, personal relationships with hosts, and the opportunity for visitors to learn about the local culture (Walter, Citation2015). Additionally, CBT has adopted a new role in helping to build political status. Minorities and hill tribe people can express their cultural identity to stand out in a multicultural society. Chiang Mai has 61 tourism communities, making the area the CBT capital of Thailand.

The nature-based ecotourism clusters are grouped along the Andaman shoreline (3), particularly the west coast, including Phuket, Phangnga, Trang, Satun, and Krabi, with their beautiful houses, world-famous beaches, and exotic islands. Traditional coastal livelihood activities and the natural resources in the area appeal to tourists. The place has been transformed into a unique sanctuary and provides the perfect hideaway destination. Competing with mass tourism, genuine ecotourism is of minor significance and has not been sufficiently established to be considered an important sector and play a meaningful conservation role (Potter, Citation2009). However, the CBT clusters in this area remain rural and natural. The community wants to maintain its original identity by setting rules and regulations for tourists to prevent undesirable impacts, demonstrating the intention of the villagers to choose a specific type of quality tourist (Satarat, Citation2010). The multiracial ethnic (combining Thai Buddhism, Chinese, Thai Muslim, and Chao Lay, e.g., Urak Lawoi, and Moken) are represented in community tourism, and natural heritage resources are consumed through food, dress, performing arts, and beliefs.

The Thai gulf shoreline to the far-east (4) is also famous for its pristine islands and beaches, and since they are not far from Bangkok, there are several travel options for traveling. The area is a flagship in the development of Thailand’s eastern provinces and being transformed into a major ASEAN Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). This area is home to the country’s largest exporting industrial zone, with an influx of international labor migration and mass tourism. The mass of incoming tourists has made Pattaya a major travel destination in Thailand. The earthen travel route circle extends to Chachoengsao and other provinces with cultural and natural attractions. These tourism communities along the Eastern Corridor are agricultural, rural, and natural landscape-oriented, providing a wide range of activities, from a fishing village homestay to shopping at a famous historical market in an ancient port town. However, the communities have become dissatisfied with the quality of their environment and experience difficulties in maintaining the community’s farming and fishing activities due to the natural resource consumption, cost of living, and low community cultural conservation indicators (Unhasuta et al., Citation2021). The local community is expected to gain a significantly higher number of visitors and share the benefits of the EEC in future with respect to carrying capacity and local resources.

5. Policy suggestions

The results of this study offer ideas for managing the expansion of CBT products and services that should be considered in the context of heritage resources. The interpretation and presentation of local heritage have been improved but remain underdeveloped. In conclusion, the recommendations for tourism community development proposed by DASTA, the National Tourism Policy Committee, and related agencies should be based on this dataset. This would strengthen policy decision-making and implementation by creating the appropriate criteria to promote and support sustainable tourism using heritage-based approaches as a benchmark for creating tourism activities in specific areas ().

Table 5. Critical issues and policy suggestions for CBT clusters

Surprisingly, the tourism density of cultural-based tourism (cultural landscape-based agritourism and group of buildings and historical district-based shopping tourism clusters) is not revealed in this spatial characteristic. The nature-based ecotourism cluster plays a dominant role in Thailand’s community tourism. This may indicate that Thailand’s CBT has increasingly relied on natural resources. Meanwhile, countries with ample financial and natural resources are more successful at utilizing them (Tang et al., Citation2022). However, mobilizing and spending billions of baht on progressing investment is not the only factor, but a successful tourism industry also involves integrating good governance, environmental, social, and economic practices. However, most potential investors appear to view heritage investment as a sunk cost, even though the government could yield financial gains for the locals through job creation and auxiliary industries (Phanomvan & Pitsuwan, Citation2015).

The group of buildings and historical district-based shopping tourism cluster is a combination of a historical market with wooden rowhouses mainly aligned along the river. However, due to the country’s transportation development over the past 50 years, unpreceded urban expansion has resulted in commercial centers shifting away and historic waterfront markets and commercial activities being abandoned (Panin & Jirathutsanakul, Citation2001). People have relocated as a result of the economic downturn, although over the past ten years, the popularity of nostalgic tourism has increased significantly (Buasorn, Citation2011). The historical market has become a gimmick for the tourism community, potentially providing economic stimulation and revitalization for the local economy. However, the cooperation of institutions, organizations, and/or government agencies is required to enable local businesses to meet the demand for modern-day tourism activities. In many communities, there has been a change in trade patterns and local commodities, with housing and dwelling units revitalized during the process, which in some cases causes a loss of local identity.

The cultural landscape-based agritourism clusters are scattered in agricultural areas (shown in yellow on the map) of the central floodplain and northeastern region. Geographically, in contrast to other areas, a vast amount of flat terrain is observed, where hills and crisscross canals can rarely be found. The landscape is dominated by rice paddy field landscape, providing a strong link to the rural culture. The agriculture sector has been repositioned to optimize the integration of indigenous cuisine, culture, wellness, and the environment into a sustainable tourist experience (Srithong et al., Citation2019). The adoption of sustainable agriculture practices and preservation of the local cultural heritage are essential factors in the development of the rice community toward tourism using GAP and organic, environmentally friendly production standards (Sattaka, Citation2019). This unique cultural landscape thus requires interaction between humans and nature to reveal the local identity to visitors.

6. Conclusion

Most of the classifications and tourism types are based on the value visitors attach to them Dolnicar et al. (Citation2018). This study reveals an upside-down classification approach based on the preservation of cultural and natural heritage. A tourism community connected to its heritage resources should maintain those resources in principle through community tourism activities. Particularly, on a local scale, tourism could affect the quality and availability of heritage resources in unprotected local settings.

In this study, the tourism communities in Thailand are classified into three clusters based on common preferences: nature-based ecotourism, group of buildings and historical district-based shopping tourism, and cultural landscape-based agritourism clusters. These clusters represent the diversity and relationship between locally available heritage resources and CBT tourism activities. These clusters focus on various “tourism activities” that affect or are affected by natural heritage, group of buildings and historical districts, and cultural landscape resources, rather than a structured built heritage (e.g., palaces, temples, old buildings, and archaeological sites). Thus, there is a key linkage between authentic identity and the in-situ activities of visitors. The results of this study reveal that the identity of CBT is associated with local management and how individuals interpreted their heritage. This is reflected in a mixture of influences, creating a unique tourism activity. Although the statistical analysis highlights the significant differences between each community tourism cluster, they share certain characteristics. The need for a “local identity” which represents the surrounding nature and culture heritage of the community, such as trees, mountains, forests, caves, beaches, group of buildings, historical districts, as well as cultural landscapes such as rice fields and coastal fisheries, widen the perspective on how the tourism boundaries are perceived.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Patiphol Yodsurang

The authors belong to the Built Environment in Heritage and Tourism (BEiHT) research unit, Faculty of Architecture, Kasetsart University. This research unit tends to work on cultural and natural heritage, built environment, vernacular architecture, and issues related to tourism facilities from local to global level. They are engaged in research projects aimed at supporting people to ensure appropriate use and sustainability in the design and planning of the built environment in a sensitive context.

Patiphol Yodsurang, the first author, graduated from the Doctoral Program in World Cultural Heritage Studies at the University of Tsukuba. He is currently a lecturer at the Graduate Program in Built Environment, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand. His professional experience and research topics include World Heritage Studies, Cultural Heritage Theory and Policy Studies, Heritage Management and an Interpretative Master Plan, Traditional Settlement and Vernacular Architecture, and Spatial Data Analysis. His research interests encompass the theoretical and methodological concerns of minorities and local heritage.

References

- Ali, A., Qadir, J., Rasool, R. U., Sathiaseelan, A., Zwitter, A., & Crowcroft, J. (2016, July). Big data for development: Applications and techniques. Big Data Analytics, 1(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41044-016-0002-4

- Amoruso, G. (2016). The image of historic urban landscapes: Representation codes. In I. R. Management Association (Ed.), Geospatial research: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 344–20). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-9845-1.ch014

- Baedcharoen, I. (2006). Heritage tourism in Chiang Mai: Measuring the perceptions of opportunities, impacts and challenges for the local community. Najua Special Issue, 31(4), 22. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/NAJUA-Arch/article/download/78985/63195/190286

- Boonratana, R. (2010). Community-based tourism in Thailand: The need and justification for an operational definition. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 31(2), 10. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/kjss/article/view/246681

- Buasorn, P. (2011). The revitalization of the old markets in Thailand. Veridian E-Journal SU, 4(1), 20. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/Veridian-E-Journal/article/view/6981/6029

- Buckley, R. (2011). Tourism and environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 36(1), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-041210-132637

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

- Community Development Department. (2017). OTOP village management guideline for 8 tourism routes. Ministry of Interior Affair. https://korat.cdd.go.th/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2018/05/%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%B9%E0%B9%88%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%B7%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A3OTOP-Village.pdf

- Cornish, R. (2007). Principal component analysis. Mathematics Learning Support Centre. https://www.statstutor.ac.uk/resources/uploaded/principle-components-analysis.pdf

- Dhiana, E., & Winanto, N. (2018, October 31). Utilization of resources through community-based tourism. UG Economic Faculty-International Conferenc.

- Di Pietro, L., Guglielmetti Mugion, R., & Renzi, M. F. (2018). Heritage and identity: Technology, values and visitor experiences. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 13(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2017.1384478

- Dixon, T. J. (2012). Brownfield development and housing supply. In S. J. Smith (Ed.), International encyclopedia of housing and home (pp. 103–109). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-047163-1.00705-0

- Dolezal, C. (2011, June 7). Community-based tourism in Thailand: (Dis-)illusions of authenticity and the necessity for dynamic concepts of culture and power. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 4(1), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-4.1-7

- Dolnicar, S., & Kemp, B. (2009). Tourism segmentation by consumer-based variables. In Kozak, M. & Decrop, A.Handbook of tourist behavior (pp. 195–212). Routledge.

- Dolnicar, S., Grün, B., & Leisch, F. (2018). Market Segmentation. In S. Dolnicar, B. Grün, & F. Leisch (Eds.), Market segmentation analysis: Understanding it, doing it, and making it useful (pp. 3–9). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8818-6_1

- Effinity. (2016). Direction of tourism development in Thailand in 10 years project. https://secretary.mots.go.th/ewtadmin/ewt/policy/article_attach/02FinalReportDirection10Year.pdf

- Guilherme, L., & Alexandre Panosso, N. (2017). Tourism theory: Concepts, models and systems. CAB International. https://www.cabi.org/cabebooks/ebook/20163390571

- Hall, D., & Richards, G. (2000). Tourism and sustainable community development. Routledge.

- Han, H., Eom, T., Al-Ansi, A., Ryu, H. B., & Kim, W. (2019). Community-based tourism as a sustainable direction in destination development: An empirical examination of visitor behaviors. Sustainability, 11(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102864

- Ho, P. S. Y., & McKercher, B. (2004, September). Managing heritage resources as tourism products. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 9(3), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/1094166042000290655

- Höchtl, J., Parycek, P., & Schoellhammer, R. (2015, December 2). Big data in the policy cycle: policy decision making in the digital era. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 26, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/10919392.2015.1125187

- Hua, S. (2010). World heritage classification and related issues—A case study of the convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(5), 6954–6961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.05.048.

- Husa, L. C. (2020). The ‘souvenirization’ and ‘touristification’ of material culture in Thailand – Mutual constructions of ‘otherness’ in the tourism and souvenir industries. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1611835

- ICOMOS. (1994). The Nara Document on Authenticity (). Retrieved from https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf

- Jakkrit, C., & Dachanee, E. (2018). Analyzing research gap on community based tourism in Thailand. Damrong Journal: Journal of the Faculty of Archaeology Silpakorn University, 1(17), 30. https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/damrong/article/view/131829/98973

- Johnson, P. (2010, January 1). Realizing rural community based tourism development: Prospects for social-economy enterprises. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 5(1), 150–162. https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/349

- Jones, T., Hughes, M., Peel, V., Wood, D., & Frost, W. (2007). Assisting communities to develop heritage tourism opportunities. CRC for Sustainable Tourism. https://www.csu.edu/cerc/researchreports/documents/AssitingCommunitiesToDevelopHeritageTourismOpportunities2007.pdf

- Jugmohan, S., Spencer, J., & Steyn, J. (2016). Local natural and cultural heritage assets and community based tourism: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 22(1–2), 306–317. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajpherd/article/view/146685

- Kaufman, L., & Rousseeuw, P. (1990 (Wiley)). . https://doi.org/10.2307/2532178

- Kaya, L. G. (2002). Cultural landscape for tourism. Journal of Bartin Faculty of Forestry, 4(4), 38–53. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/barofd/issue/3410/46903

- Krznaric, D., & Levcopoulos, C. (2002, September). Optimal algorithms for complete linkage clustering in d dimensions. Theoretical Computer Science, 286(1), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3975(01)00239-0

- Kurniawan, H., Salim, A., Suhartanto, H., & Hasibuan, Z. (2021). E-cultural heritage and natural history framework: An integrated approach to digital preservation. 2011 International Conference on Telecommunication Technology and Applications. Singapore 5 (IACSIT Press,), 177–182. http://www.ipcsit.com/vol5/32-ICCCM2011-A094.pdf

- Leksakundilok, A. (2004). Community Participation in Ecotourism Development in Thailand. University of Sydney. Faculty of Science, School of Geosciences. https://doi.org/10.0000/handle.net/2123/668

- Li, Y. (2003). Heritage tourism: The contradictions between conservation and change. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(3), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840300400305

- Liu, Y., & Lin, H.-W. (2021). Construction of interpretation and presentation system of cultural heritage site: An analysis of the Old City, Zuoying. Heritage, 4(1), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4010020

- Lo, Y.-C., Janta, P., Pammi, V. S. C., & Dutt, V. (2020, July 24). Resident’s perspective on developing community-based tourism – A qualitative study of Muen Ngoen Kong Community, Chiang Mai, Thailand [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01493

- Ministry of tourism and sport. (2020). Guideline for Promoting Sustainable Tourism Development. https://mots.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=12288

- Nandita, J., & Ronnakorn, T. (2003). Community-based tourism for conservation and development: A training manual. RECOFTC. The Mountain Instite

- Nicholls, S., Vogt, C., Hyun, S., & Nicholls, J. (2004, June 11). Heeding the call for heritage tourism: More visitors want an “experience” in their vacations—something a historical park can provide. Parks & Recreation (Ashburn), 39(9), 38–49. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.602.6461&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Niskasaari, K. (2008). Towards a socio-culturally sustainable definition of authenticity: Re-thinking the spirit of place 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the spirit of place – between the tangible and the intangible’, Quebec, Canada. ICOMOS. http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2/

- Ohe, Y. (2020). Community-based rural tourism and entrepreneurship: A microeconomic approach. Springer Singapore.

- Panin, O., & Jirathutsanakul, S. (2001). Urban vernacular commercial house. NAJUA: Architecture, Design and Built Environment, 18(1), 43–58. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/NAJUA-Arch/article/view/45813

- Park, E., Choi, B.-K., & Lee, T. J. (2019, October 1). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 74(1) , 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.03.001

- Pelasol, M., Tayoba, M., Mondero, E., Jugado, K., & Lahaylahay, C. (2012, September). Destination in the southern part of Iloilo, Philippines. JPAIR Multidisciplinary Research, 8(1), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.7719/jpair.v8i1.173

- Peleggi, M. (1996, January). National heritage and global tourism in Thailand. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 432–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00071-2

- Petti, L., Trillo, C., & Makore, B. N. (2020). Cultural heritage and sustainable development targets: A possible harmonisation? Insights from the European perspective. Sustainability, 12(3), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030926

- Pham Hong, L., Ngo, H. T., Pham, L. T., & Coetzee, W. (2021, January). Community-based tourism: Opportunities and challenges a case study in Thanh Ha pottery village, Hoi An city, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1926100. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1926100

- Phanomvan, P., & Pitsuwan, F. (2015). Heritage investment: The forgotten economic assets in Thailand. Thai Publica. https://thaipublica.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Heritage-Investment_final-2.pdf

- Potter, D. J. (2009). Ecotourism in Thailand’s Andaman coast: An assessment of modes, localities and mediators. National University of Singapore]. https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/18602

- Pratomlek, O. (2020). CRITICAL NATURE: Community-based tourism in Thailand: Impact and recovery from the COVID-19. Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University. https://www.csds-chula.org/publications/2020/6/2/critical-nature-community-based-tourism-in-thailand-impact-and-recovery-from-the-covid-19#:~:text=The%20government%20also%20provides%20incentives,by%20the%20Community%20Development%20Department

- Revelle, W. (2021). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. In https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- Royal Forest Department of Thailand. (2001). Thailand land use and forest cover in 2000. http://www.savgis.org/thailand.htm

- Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2019, May). Cultural heritage and Indigenous tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1581788

- Sangkaew, N., & Zhu, H. (2020). Understanding tourists’ experiences at local markets in Phuket: An analysis of tripadvisor reviews. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 23(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2020.1848747

- Satarat, N. (2010). Sustainable Management of Community-Based Tourism in Thailand National Institute of Development Administration]. http://libdcms.nida.ac.th/thesis6/2010/b166706.pdf

- Sattaka, P. (2019). Potential development of glutinous rice community towards new agricultural culture tourisms in upper Northeastern Thailand. Journal of the International Society for Southeast Asian Agricultural Sciences, 25(1), 92–103. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20193361902.

- Sharon, H. (2010, July 1). Planning for community based tourism in a remote location [article]. Sustainability, 2(7), 1909–1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071909.

- Sin, H. L., & Minca, C. (2014, January 1). Touring responsibility: The trouble with ‘going local’ in community-based tourism in Thailand. Geoforum, 51(1), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.004

- Sirisrisak, T. (2007). Historic urban landscape: Interpretation and presentation of the image of the city. ICOMOS Thailand International Symposium 2007, Bangkok, Thailand (ICOMOS Thailand).

- Smith, W. R. (1956). Product differentiation and market segmentation as alternative marketing strategies. Journal of Marketing, 21(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224295602100102

- Somchan, S. (2019). The guideline for shopping tourism development to promote tourism in Phayao, Thailand. Consumer Decision-Making (Sub-Topic).

- Specht, J. (2014). Architectural tourism: Building for urban travel destinations. Springer Gabler.

- Sratthaphut, L., Jamrus, S., Woothianusorn, S., & Toyama, O. (2013). Principal component analysis coupled with artificial neural networks for therapeutic indication prediction of Thai Herbal formulae. Science, Engineering and Health Studies (SEHS), 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.14456/sustj.2013.4

- Srithong, S., Suthitakon, N., & Karnjanakit, S. (2019). Participatory community-based agrotourism: A case study of bangplakod community, Nakhonnayok Province, Thailand. PSAKU International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 8(1), 9. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PSAKUIJIR/article/view/218557.

- Stevens, J. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Erlbaum.

- Su, X., Sigley, G. G., & Song, C. (2020). Relational authenticity and reconstructed heritage space: A balance of heritage preservation, tourism, and urban renewal in Luoyang Silk Road Dingding Gate. Sustainability, 12(14), 5830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145830

- Sverdrup, H., & Svensson, M. G. E. (2002). Defining sustainability. In H. Sverdrup & I. Stjernquist (Eds.), Developing principles and models for sustainable forestry in Sweden (pp. 21–32). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9888-0_3

- Tang, C., Irfan, M., Razzaq, A., & Dagar, V. (2022, June 1). Natural resources and financial development: Role of business regulations in testing the resource-curse hypothesis in ASEAN countries. Resources Policy, 76(1), 102612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102612

- Timothy, D. J. (2011). Chapter 2. Consumption of culture: Heritage demand and experience. In Dallen J. Timothy eds. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction (pp. 15–45). Channel View Publications.https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845411787-006

- Trebuňa, P., & Halčinová, J. Mathematical tools of cluster analysis. (2013). Applied Mathematics, 04(5), 3. Article 31454. https://doi.org/10.4236/am.2013.45111

- Unhasuta, S., Sasaki, N., & Kim, S. M. (2021). Impacts of tourism development on coastal communities in Cha-am Beach, the Gulf of Thailand, through analysis of local perceptions. Sustainability, 13(8), 4423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084423

- United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization. (2005). Making tourism more sustainable: A guide for policy makers (United Nations Environment Programme). https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/8741

- Uriely, N., Reichel, A., & Shani, A. (2007, September). Ecological orientation of tourists: An empirical investigation. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(3–4), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.thr.6050045

- Verovšek, Š., Juvančič, M., & Zupančič, T. (2016, January 1). Recognizing and fostering local spatial identities using a sustainability assessment framework [article]. Annales-Anali Za Istrske in Mediteranske Studije - Series Historia Et Sociologia, 26(3), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.19233/ASHS.2016.42

- Walter, P. G. 2015. Travelers’ experiences of authenticity in “hill tribe” tourism in Northern Thailand. Tourist Studies.16(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797615594744

- Weaver, D. (2002, January). Asian ecotourism: Patterns and themes. Tourism Geographies, 4(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680210124936

- Yanapa, B., Cheewin, K., & Sasiphatr, P. (2020). Emergence of ecotourism in Thailand. Dusit Thani College Journal, 13(2), 13. https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/journaldtc/article/view/241081

- Yanes, A., Zielinski, S., Kim, S. I., & Cano, M. D. (2019, May 1). Community-based tourism in developing countries: A framework for policy evaluation [article]. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(9), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092506

- Yodsurang, P., Hiromi, M., & Yasufumi, U. (2015). A traditional community in the Chao Phraya River Basin: Classification and characteristics of a waterfront community complex. Asian Culture and History, 8(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.5539/ach.v8n1p57

- Zielinski, S., Jeong, Y., & Milanés, C. B. (2020). Factors that influence community-based tourism (CBT) in developing and developed countries. Tourism Geographies, 5-6, 23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1786156

- Zukin, S. (1995). The Cultures of cities. Blackwell publishers.