Abstract

Santiago de Compostela is one of the best-known pilgrimage routes globally, and it connects many countries in Europe. Its historic center was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985. This article aims to assess the types and quality of social interaction among residents and visitors (city users) of this particular World Heritage City. Many studies were conducted prior to this one about Santiago. However, most of them have missed some recent approaches to the overtourism phase. The “overtourism” is a phase, which was notorious until 2019. The primary sourcing was assessed by a quantitative study accompanied by a questionnaire responded by 588 residents. The results confirmed that those more exposed to tourism were the most critical of their relationship with the visitor. Thus, we confirm a direct relationship between the intensity of contact with the visitor and the negative perception of tourism. The results are helpful for local and regional planners to implement more collaborative and democratic planning in the tourism sector. This is more relevant to destinations recognized as UNESCO and revealed an overtourism scenario. This new approach is urgent and must be prepared in the on-going COVID-19 pandemic and a short and long-term perspective.

1. Introduction

As an activity in the service sector, tourism is confirmed as one of the main activities of the world’s economy. It is considered an economic activity capable of bringing development to undeveloped areas (Organización Mundial del Turismo, Citation2018) through transformations in the economic, social, and cultural sphere (Dias & Cassar, Citation2005). Tourism activity must be faced as a complex system (Roxas et al., Citation2020), that without proper planning can also have a series of negative impacts (Mathieson & Wall, Citation1982; Su et al., Citation2018; Goffi et al., Citation2019). For that, more and more locations are looking to tourism as an alternative to attract foreign exchange and create jobs and income. In parallel with the increase in revenues, this activity has undergone essential changes in planning and execution (Buhalis & O’Connor, Citation2005; Su et al., Citation2018). Therefore, understanding what the natives think and feel about tourism should concern the planners, managers, and organizers of tourism and the destinations. Also, because they are crucial for the establishing of sustainable tourism destinations (Erul et al., Citation2020; Jackson, Citation2008; Vodeb et al., Citation2021).

Tourism activity plays a significant role in society. In addition to providing development through creating jobs and income, it can become an excellent incentive for culture and, therefore, result in valorizing a people’s historical and cultural heritage (Perinotto & Santos, Citation2011; World Tourism Organization (UNTWO), Citation2018). Santiago de Compostela has a vast potential of cultural attraction, and it is necessary to consider that a heritage commercialized through tourism must have, beforehand, a relationship of local identity and a consolidated memory with the local population. Consequently, it is crucial to determine whether autochthonous tourism as a good that must be respected and preserved and if this sort of touristic good is fit to be “shared” with visitors, though, for example, Cultural Tourism practices. Thus, it is assumed that the local population is an integral part of the heritage appreciation and one of those responsible for its preservation and valorization.

Consequently, the host communities suffer numerous impacts from the touristic activity (Carneiro et al., Citation2018; García Gómez et al., Citation2018; Gursoy et al., Citation2019; Soares et al., Citation2022). Cultural daily interaction amongst tourists and locals may affect the residents’ daily lives causing modifications in habits, attitudes, and behaviors (Cañizares et al., Citation2014; Pizam & Milman, Citation1984). These premises are the base premises on which the study is designed, and it aims to assess the type and the quality of social interaction among residents and visitors (the city’s users). The study of residents’ perceptions is justified by the need to develop effective, sustainable tourism projects that support the local community. It is also imperative to consider the urgency for a tourism sector that is planned more democratically. In addition, a UNESCO-certified city can offer more cultural activities, a more preserved tangible and intangible heritage. These cultural activities and the heritage aspects can (and must) be profitable for both residents and visitors. The interaction among them is crucial to the success of the destination.

Additionally, it is vital to identify and find solutions for potential conflicts of interest amongst residents and public stakeholders. These public stakeholders are involved in local tourism development planning, and their active participation is fundamental to offer quality tourism capable of improving the perceived benefits and reducing the negative impacts of tourism (Cañizares et al., Citation2014; Royo & Ruiz, Citation2009). Ultimately, it is urgent to undertake this approach during the current on-going COVID-19 pandemic. The current sanitary crisis is perceived as an opportunity to prepare and adjust the tourism offer to the ex-post COVID-19 period.

Santiago de Compostela was the destination in focus. It is the Galician capital, and it has been receiving a large number of visitors for centuries due to the Camino de Santiago. The Camino is a well-known pilgrimage route that unites several countries in Europe, and it holds a World Heritage designation for its entire historic district.

A quantitative in nature methodology was used throughout the study. The perceptions of those who use the city of Santiago de Compostela have been analyzed simultaneously, i.e., the residents and the non-residents. This is not a current way to do it, as the perceptions of the two stakeholders are usually analysed separately. The same questions were applied to both groups.

The paper is organized into five sections. Beyond this initial introduction to the topic, the literature review is carried out regarding the host community’s relationship with the tourist. The destination overview is found in the third section of this paper, along with the investigation methodological steps. The fourth section presents the main results, and some discussion is carried out. The last section presents the study’s conclusions, some limitations, and recommendations for future work.

2. The studies on residents’ perception regarding tourism

The impacts of tourism began in the early 1970s and continued to increase in the 1980s (when some negative impacts began to be felt in several destinations). On another hand, the subject “The residents’ perceptions about the impacts of tourism” has been of interest in an increasing number of academic studies also since de 1970s (e.g., Ap, Citation1992; Gursoy et al., Citation2019; Hadinejad et al., Citation2019; Pizam, Citation1978; Rothman, Citation1978; Scalabrini & Remoaldo, Citation2020; Vodeb et al., Citation2021). The main reason is the increasing awareness of the positive and the adverse effects of tourism development at a local level (Gursoy et al., Citation2019; Ko & Stewart, Citation2002; Lankford & Howard, Citation1994; Lopes et al., Citation2019; Remoaldo et al., Citation2015).

An evolution took place since the late 2000s involving analytical perspectives, which mainly concerned a deeper analysis of other types of impacts instead of just the economic impacts (economic impacts are most tangible and easily measured). Despite the 2000s evolution, the studies published tend to evaluate the residents’ and the non-residents’ perceptions separately. In fact, the perceptions and evaluations about the tourism industry began with the visitors’ perception and only later was passed to the residents’ perspective. As the approaches are different, their theoretical support tends to differ, even when the same analytical techniques are performed. Self-applied questionnaires has been the predominant technique even if the sorts of questions differ between residents and visitors.

In the second scenario, the destination’s attributes, along with the profile and visitors’ motivations, were the most relevant. Thus, it is essential to state that some questions about the perception of the impacts of tourism were also asked.

Nunkoo et al. (Citation2013) confirmed these statements. These three writers made a very extensive analysis of this subject. They carefully analyzed 140 articles published between 1984 and 2010. The 140 articles discuss the resident’s attitudes towards tourism, and they were able to identify that there are few published theoretical studies. Nowadays, the majority of these studies are empirical. Milito et al. (Citation2013) brought a contrasting approach, which claims that the action to seek to understand the residents’ position must be an object of study for both theoretical and empirical fields in the context of tourism. Despite the different perspectives on this theme, most studies focus mainly on perceptions and attitudes towards the socio-cultural and environmental impacts of tourism (Almeida & Balbuena, Citation2014; Almeida-García et al., Citation2015; Andereck & Nyaupane, Citation2011; Bujosa & Rossello, Citation2007; García López et al., Citation2018; Oviedo et al., Citation2008; Pacheco et al., Citation2019; Remoaldo et al., Citation2015; Wall & Mathieson, Citation2006; World Tourism Organization (UNTWO), Citation2018).

It can be noted that one line of work is adopted by a group of authors that have performed studies about the perceptions of socio-cultural impacts in a destination (Brunt & Courtney, Citation1999; Eshliki & Kaboudi, Citation2012; Gu & Wong, Citation2006; Lopes et al., Citation2019; Navarro Favela et al., Citation2018), while another line of work is performed by another group of writers when writing studies on the resident’s perceptions be the comparison method of various destinations (Jaafar, Noor et al., Citation2015; Latkova & Vogt, Citation2012; Madrigal, Citation1995; S. M Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2017; Tosun, Citation2002). Moreover, Monterrubio-Cordero (Citation2008) showed that there exists the possibility to find theoretical studies focused on the development of models to evaluate the study of perceptions towards tourism (Lankford & Howard, Citation1994), and it is possible to find literature review studies aimed to develop theoretical frameworks (Ap, Citation1992; Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004). Besides, according to the literature review carried out by Monterrubio-Cordero (Citation2008), some of these studies compared the perceptions of different groups in the same region (Besculides et al., Citation2002) or by comparing the perceptions of several subgroups within a community (Petrzelka et al., Citation2005).

On the other hand, one can not forget that some studies focus on identifying a set of variables that could help to develop a resident profile based on sociodemographic characteristics and attitude towards the impact of tourism on the local environment, economy, and cultural life (Almeida-García et al., Citation2015). In light of this, Brida et al.’s (Citation2010) studies are outstanding, as these authors used cluster analysis and multinomial logistic model techniques to analyze the residents’ perception of tourism in Northern Italy. The results of their study identified different groups with homogeneous opinions being influenced by employment opportunities in the tourism sector and the visitors’ demographic profiles. The study written by Williams and Lawson (Citation2001) followed this same methodological approach in 10 towns in New Zealand. The researchers divided the samples according to the homogeneity of opinions, and they applied the cluster analysis method. They found that community issues are more important among the variables that most influence residents’ perceptions than those related to the respondents’ demographic characteristics. The authors argue that the most positive people towards tourism pay less attention to community issues.

Getz (Citation1994) mentioned that the study of residents’ perceptions could be a critical element in identifying, measuring, and improving the impacts of tourism. The literature review undertaken by Campón-Cerro et al. (Citation2019) concluded that most of the studies related to quality life and tourism are mainly focused on exploring the perception of residents and tourists toward the effects of tourism (Jaafar, Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2006).

Zhang et al. (Citation2006) found that the theoretical frameworks of the studies about the resident-tourist interaction are simplistic, and that exists a need to include already established socio-psychological theories. Thus, the authors published a series of studies applying different qualitative techniques, and they tested some models to understand and predict the behaviors in the interaction of locals and visitors. Among these many studies, the paper published by Zhang, Inbakaran and Jackson (Citation2006) stands out. It analyses community attitudes towards tourism and host-guest interaction, and it took place in ten selected communities in the urban-rural fringes of Melbourne (Australia). The authors applied the cluster analysis technique using ANOVA to process the data and found that residents who live far from the main tourist attractions have a more positive attitude towards tourism. They also learned that there are significant correlations between negative perceptions and level of education, residence period length, and employment in the tourism sector. Finally, a significant correlation between the residence period length and less negative attitudes towards the impacts of tourism.

No one must ignore the negative aspect that tourism can cause friction between residents and visitors due to environmental, economic, and social impacts. The disturbances for residents are numerous and can range from problems with parking, infrastructure saturation, and heavy traffic (Palmer-Tous et al., Citation2007) and significant increases in noise and waste (Andereck et al., Citation2005; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004; Valencia, Citation2017). The negative attitudes of tourism can be a handicap for the development and sustainability of this activity (Diedrich & García, Citation2009; Sharpley, Citation2014). In addition, the inconveniences and collateral damage that tourism can cause to the local population can generate and perpetuate negative attitudes towards tourism (Almeida-García et al., Citation2015), and be a limiting factor for the sector. On the other hand, a positive attitude can foster tourism development (S. Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2015). The community can undoubtedly be considered the most critical part of any project, as it is the most positively or negatively affected by tourism planning and development (Eshliki & Kaboudi, Citation2012). As Gabriel et al. (Citation2017) point out, residents of tourist destinations are more aware of the positive and negative impacts of tourism development. On the contrary, people who live in places with little or nothing “touristized” do not have the same perception of this problem.

The negative impacts of tourism are perceived mainly in urban destinations, or it can be found at places where there is shared use of the interurban structures among domestic and international tourists. Such places are recognized as having various facilities shared by different types of users, and they can be classified as tourist and non-tourist (Ashworth, Citation2009). Ashworth and Page (Citation2011) follow the same line of reasoning, as they define those tourists, residents, city workers, students, and day-trippers, as city users. Often, the tourist activity is very close to locals, which affects the shapes and city’s functionality.

It is imperative to note the relevance of studies that focus on the touristic consumption in destinations which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites (WHS), and to analyze the perception of the destination’s community. In addition, it is crucial to understand the tourist’s behavior, especially when regards a sensitive and tourism-dependent destination (Md Khairi et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). The growing number of visitors to a WHS destination can be managed by applying this information from tourists at WHS locations. Notably, an effective management plan will also help maintain WHS status over the long term. It is relevant to emphasize that tourist behavior is essential, especially for those responsible for managing the heritage area.

WHS are mainly located in Europe (42% of the total), followed by Asia Pacific (20%) and the Americas (17%—the sum of North and South America). The other areas (Africa and the countries of the Middle East) each add up about 10% (Farid, Citation2015). The number of WHS sites can have a positive and significant effect on international tourist estimates. Therefore, a country with WHS sites is in an advantageous position not only for the sustainable conservation of cultural achievements and natural resources, but also for developing the tourism economy. These two purposes are not contradictory. In truth, they are complementary. Conservation is the only way to keep WHS sustainable tourism revenue, and revenue from tourism is indispensable to the preservation of the WHS. Yang et al. (Citation2019) argue that the effect of increased tourism has been considered more significant in recent years in cultural WHS sites and developing countries, but complementary less in natural WHS sites and dyadic datasets.

The literature regarding the impacts of tourism and the resident’s attitudes towards tourism suggests that the assessment of social impacts is done thru some conceptual models (Monterrubio-Cordero, Citation2008; Wall & Mathieson, Citation2006). Some of these models focus on changing residents’ attitudes towards tourism over time (Butler, Citation2006; Dogan, Citation1989; Doxey, Citation1975). Other models focus on the continuum of possible strategies to answer for the impacts of tourism (Ap & Crompton, Citation1993). In their model, Ap and Crompton (Citation1993) proposed strategies to combat tourism impacts through a model based on primary qualitative data from some determined communities. According to these authors, categorizing residents’ reactions is possible through a “continuum” of attitudes, such as reception, tolerance, adjustment, and withdrawal. However, the authors stated that the proposed model must not be rigid.

Finally, according to bibliometric studies carried out by Nunkoo et al. (Citation2013), the methods used to study residents’ perceptions of tourism are qualitative, quantitative, and quanti-quali. Concerning theoretical bases, Milito et al. (Citation2013) identified that most of the recent research is based on the Social Exchange Theory (SET—quantitative approach) and Ethnography—qualitative approach).

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire used

A self-administered questionnaire survey was applied and launched in 2018 to 588 residents of Santiago de Compostela (capital of Galicia region). It aimed to evaluate the quality of contact between resident and tourist who visits the city.

The questionnaire had 26 questions. Initially, a pre-test was carried out with 11 people of different levels of education, age group, and gender. On average, it took nine minutes to complete the questionnaire. For the final version, some adjustments were made to make some questions clearer and more objective, and, as the answer was online, it was mandatory to answer all questions to finalize the questionnaire.

We used a five-point Likert scale to classify the impacts (ranging from 1—“completely disagree” to 5—“completely agree”), which is the most commonly mentioned scale in the literature on tourism impacts.

This kind of scale has been used worldwide in several studies concerning perceptions on tourism impacts perceived by the residents (e.g., Kuvan & Akan, Citation2005; Lopes et al., Citation2019; Scalabrini & Remoaldo, Citation2020; Vareiro et al., Citation2013). The data were collected between February and June 2018. An initial question was asked to ensure that no one who did not live or did not work daily in the city could not answer the questionnaire. A total of 614 people completed the questionnaire, with 588 valid responses.

Various facilities such as educational establishments, social centers, sports centers, cultural centers, and neighborhood associations were used for data collection. The questionnaires were sent to these venues around to all the districts of the city.

The questionnaire consisted of 26 questions, and it was divided into three parts: the first part related to the quality of contact; followed by the residents’ perceptions of the impacts of tourism; and demographic data from respondents (sex, age, marital status, education, and neighborhood of residence). A descriptive statistical analysis of the survey responses was performed using SPSS (version 24.0). This paper discusses the issues related to the first part of the questionnaire regarding the quality of contact with tourists visiting the city of Santiago de Compostela.

The analysis of the impact of contact, as perceived by the residents of Santiago de Compostela, was based on a set of indicators extracted from the implemented research. The indicators allowed the researchers to classify the data into three distinctive intensities (positive contact—negative contact—indifferent contact). Some descriptive statistics were used in the analyzes. The chi-square test was used as a test of independence, which assesses whether paired observations on two selected variables are independent of each other. Other studies used this test to evaluate residents’ perception concerning the quality of the touristic employment (Marrero Rodríguez & Huete Nieves, Citation2013). It was also used to classify their perceptions about the impacts of tourism (Carballo Cruz et al., Citation2012; Han et al., Citation2010). Additionally, it was used from tourists’ perspectives about the impacts of tourism activity (Liu & Yen, Citation2010).

3.2. Territory object of study

Tourism in heritage cities can be seen as an essential ally for heritage (it may be the object of interest in public policies for conservation, restoration, valuation, and generation of investments for the destination), but it can also be an enemy. In this second case, the massification of heritage tourism can lead to a loss of authenticity or deterioration. In addition, it can affect the quality of life of the host community.

Santiago de Compostela is the Galician capital and has received many visitors for centuries due to the Camino de Santiago, a pilgrimage route that unites several countries in Europe. Another relevant feature is the designation of World Heritage in 1985, by UNESCO, of the entire historic district. Santiago has an annual tourist flow of around four million visitors and a population of approximately 96,000 inhabitants (INE, Citation2018). In other words, tourism pressure on residents in Santiago and neighboring municipalities was 1.90 tourists per 100 inhabitants in 2017 (IGE, Citation2017). Thus, the place is configured as the Galician city with the closest visitor/resident ratio to larger cities such as Barcelona or Valencia.

According to the Concello de Santiago (Citation2018), the number of inhabitants of the Historic City (central tourist district of the city) is decreasing due to: population aging, a deficit of services compared to other neighborhoods, parking problems, and also the tourist phenomenon. The tremendous pressure of tourism encourages those residential properties are dedicated to the tourist offer.

Its rich heritage attracts millions of tourists annually. In addition, the number of people who take one of the “Caminos de Santiago” itineraries every year keeps breaking records. This is due to the efforts of the state government to promote culture and boost the itineraries of the Camino de Santiago since 1991 (Xacopedia, Citation2015). Likewise, as Santiago Turismo (Citation2019) highlights, the city receives millions of visitors throughout the year out of devotion to hold its professional events for the festivities declared of International Tourist Interest. These aspects explain the sustained increase in the number of visitors to the city since the beginning of this millennium, a consolidated international destination for religious and cultural tourism.

However, according to Coco (Citation2017), for the geographer and economist Juan Requejo, cities have the right to remain alive. They are entitled to decide the tourism model they want to receive. Therefore, the results of this investigation can also be used so that local managers can work on aspects identified in the investigation carried out to improve the relationship between residents and tourists. Therefore, considering that dialectic is attentive to conflicts and interests, Schmid’s (Citation2012) thinks that nothing is absolute and may be loaded with contradictions and conflicts. Therefore, we understand that the resident’s perception cannot be neglected under the penalty of reaching a unilateral, relativized, or biased “truth”.

4. Main results and discussion

The total number of questionnaires achieved is in line with those of other researchers, such as Faulkner and Tideswell (Citation1997), who targeted 400 respondents. Williams and Lawson (Citation2001), who used a sample size of 415 respondents, McDwall and Choi (Citation2010), where 352 complete surveys were used, Brida et al. (Citation2010), which obtained 295 usable questionnaires and Vareiro et al. (Citation2013), which received 400 valid responses.

The questionnaire developed was based on previous studies on residents’ perceptions of the impacts of tourism (Besculides et al., Citation2002; Jackson, Citation2008; Kuvan & Akan, Citation2005; Monjardino, Citation2009; Remoaldo et al., Citation2015; Sharma & Dyer, Citation2009; Vareiro et al., Citation2013, Citation2016; Williams & Lawson, Citation2001).

In this article, only questions about contact with tourists were considered for analysis (Do you usually have contact with tourists?, and In general, how would you qualify your contact with tourists?). Various statistical procedures were carried out. In the first step, before another statistical analysis was carried out, univariate statistical data were calculated for the research items. Inthe second stage, the chi-square test was performed to identify a possible association among the variables used in the study (relationship between contact and perception).

4.1. The respondents’ profile

summarizes the profile of the subjects using the main sociodemographic variables. The majority of respondents answering the questionnaire were female (58%). This correlates with the municipality’s population (universe). According to data from the National Statistics Institute (INE, Citation2018), 54% of the inhabitants were female. An age categorization distribution was done considering the generations according to the criteria of Díaz-Sarmiento et al. (Citation2017). When comparing the population sample to Galician population (IGE, Citation2017), it was found that there is a limitation to this work due to a large concentration of the Millenniums Generation and a smaller representativity of the age of 59 and older (represented in 21.96% and 33.85% in the IGE, respectively). 30% of the total respondents work in the tourism sector. It was observed that a large part of the respondents had a high level of education: 48.5% with university studies, and 27.2% have achieved a master’s or doctor’s degree.

Table 1. Respondents’ Profile

Regarding the residential neighborhoods, 11.6% of the sample was living outside the predominantly urban area, but most maintained some daily relationship (work or study) with the city. Most respondents lived in off-site neighborhoods with greater tourist interest, such as the Historic City or the neighborhood of San Pedro (62.9%). However, almost ¼ of the population of Santiago de Compostela lived in neighborhoods considered to be touristic within the city. That is, 25.5% of respondents lived in Zona Vella or the neighborhood of San Pedro, consideredin this study as the city’s touristic city districts. According to data from the Municipality of Santiago de Compostela (2019), 16.95% of the city’s population lives in this sector of the city. Therefore, our sample approximates the percentage of the population that resides in this sector.

4.2. Results

The research asked questions about whether contact with the tourist changes the locals’ habits in Compostela (work routines and time of leisure and free time). We found that the vast majority of respondents (81.6%) do not see their work routines altered by the presence of the tourist. However, when taking into consideration the time of leisure and free time, the results indicate that almost half (47%) of these individuals see their day-to-day life altered by contact with tourists in the city during their free time.

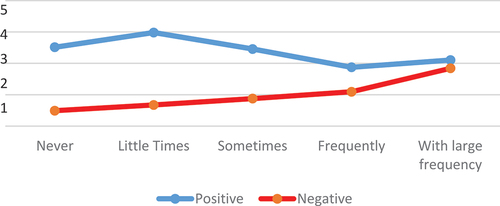

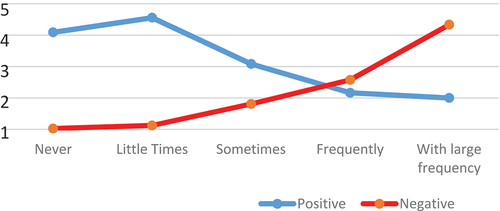

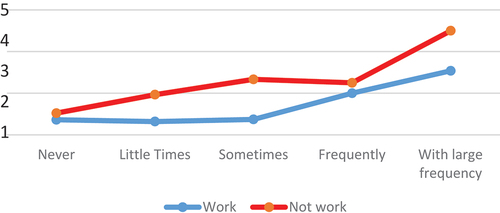

We related the questions 6a. (Contact with the tourist alters my habits in my leisure time <Never—A few times—Sometimes—Often—Very often>) and the questions 6b. (Contact with the tourist alters my habits in my work <Never—A few times—Sometimes—Often—Very often>) with question 7. (In general, how would you describe your contact with tourists? <Positive—Indifferent—Negative>). The result is that less contact with the tourist changes the resident’s habits (questions 6a and 6b), the best contact is considered (question 7). Likewise, the more the contact with the tourist changes the resident’s habits (questions 6a and 6b), the more the possibility of the evaluated contact as a negative increased. This relationship is easily visualized on the lines resulting from this relationship ( and ), but it will be discussed in .

Table 2. Relationship between changing work habits and contact assessment *

Table 3. Relationship between habit alteration during leisure time and contact assessment*

When checking the relationship between the resident and the tourist during their working time (), we can identify that the perception of this contact is mostly positive (). However, there is a slight increase in negative perception, as this contact with the tourist changes their work habits. However, if we verify the perception from the contact with the tourist in the leisure time of the respondents, we will see a more intense relationship ().

Graph 1. Working time versus perception of contact with the tourist.

If we analyze the relationship with the tourist during the leisure time of the respondents in Compostela (), a percentage of 30% of the total numbers indicated that the contact with the tourist never alters locals’ habits during leisure time. This number is the most representative category. In addition to that, only 12.4% of the subjects mentioned that the contact altered “Frequently” their habits, and fewer than (5.1%) of the subjects considered the category “With Large Frequency.” Hence, this interaction is expected to be a friendly relationship or not negatively affect the resident’s life. In addition, what interests us the most is the possibility to analyze the relationship among changing habits due to tourism and the perception of the contact on the resident’s life.

As can be seen, the percentages of negative perceptions increase as the contact becomes more intense. The negative perception of contact goes from 0.5% (for those who never have contact with tourists during leisure time) to 66.7%, for those who have contact very often. Checking in detail, we see that the intensity of the contact (Never—A few times—Sometimes—Often—Very often) can be considered almost as an ascending line for negative perception and descending for positive impressions ().

Graph 2. Leisure time versus perception of contact with the tourist.

To complete the analysis, when asking if the contact with the tourist was positive or negative, we found that, in general, the relationship was positive (50% of positive interaction). However, if we want to minimize the negative impacts of tourism for a population, it is essential to consider the 12.8% that qualified the contact with the tourist as negative and that 36% consider that the relationship was neither positive nor negative.

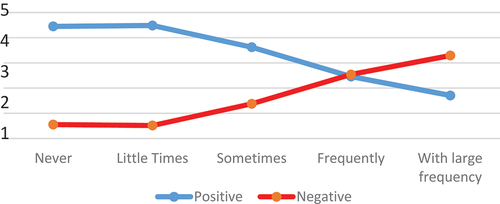

Visualizing this association between the variables on the lines, we decided to relate the general contact (Questions 6a and 6b), regardless of leisure or work time, with the qualification given to that contact (Question 7), which returns us to . The lines in this graph indicate that the more the resident sees their habits affected by tourism, whether at leisure or work, the more negative the relationship he or she has with the visitor (red line).

Graph 3. Contact with the tourist impacts the relationship with the resident.

In order to assess the association between the variables Change in the habits (Contact with the tourist alters my habits) and perception of contact with the tourist (How would you qualify your contact with tourists?), we used the Chi-square test, applying the statistical software SPSS version 24, with a level of significance of 5% and a p—value <0.05.

Therefore, the chi-square test was finally carried out to identify whether the change in the resident’s habits, due to contact with the tourist, is related to the qualification given to contact with the visitor. We performed the chi-square test for the three previous assumptions: 1) work habits altered by tourism, 2) leisure habits altered by tourism, and 3) habits altered by tourism ().

Table 4. Chi-square test result

As can be observed from the result of significance, we confirm that there is a relationship between the contact with the tourist (change habits) and the negative perception of tourism (p < 0.05 in the three assumptions). The more the resident alters their habits towards tourism, the more likely considers tourism as unfavorable. This confirms that these two variables are dependent. As detailed below, we sought to verify whether there were differences between the responses by sociodemographic characteristics and the 1-factor ANOVA test was performed using gender, age, education, work in industry, residential area and family income as the dependent variable. Significant differences were only identified for the work in industry variable (discussed below). For all the other tests, including the sociodemographic variable gender, it was found that the p value was greater than 0.05, which allows us to affirm that the variances are homogeneous. That is, there are no significant differences between perceptions regardless of these sociodemographic characteristics. Or to put it another way, men and women in the sample, of any age in Santiago de Compostela, coincide in their perception of contact with tourists.

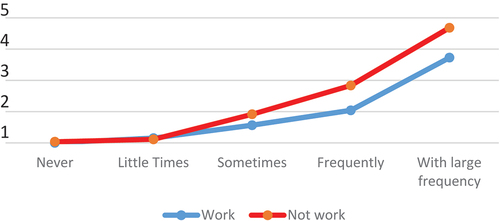

Nunkoo et al. (Citation2010) stated that “Residents’ occupational identity influences their attitudes to tourism impacts” and “Residents’ gender identity influences their perceptions of tourism impacts”. Therefore, we decided to analyze these two variables (occupation and gender) in our study. As for gender, we did not identify significant differences for the relationship between tourists and neither for the resident in leisure time (F-ratio 0.267, p-value 0.606) nor at work (F-ratio 1.039, p-value 0.309). On one side, considering residents’ leisure time, the data indicate that, regardless of whether or not they work in the tourism sector, the negative perception of tourism increases the more the frequency of contact increases during their leisure time. However, from , it seems clear that those who do not work in the area have a more negative perception of contact with tourists. We then performed a t-test, and the result indicates that there are no significant differences between these two perceptions (F-ratio 0.311 and p-value 0.577 > 0.000). These results indicate that regardless of the employment relationship with the sector, the resident of Santiago de Compostela realizes that tourism negatively affects his leisure time. This may be due to the massification of spaces for leisure (e.g., bars, restaurants, squares, gardens, and museums). Those who reside in a destination massified by tourism are unable to enjoy their free time, due to the tourists’ constantly occupied infrastructure.

Graph 4. Negative impact of contact with tourists during leisure time.

On the other hand, if we relate the perception of contact with the tourist at the time of work, the data indicate that for those who do not work in the area, the more the frequent the contact with the tourist increases, the more negative the perception of that contact is.

Graph 5. Negative impact of contact with tourists on working time.

In this study, we relate occupational identity with working or not in the tourism sector. Therefore, we understand that people who are outside the tourist area have more occupational identity. We performed the test-t again considering the respondent’s employment relationship with the tourism industry and found significant differences for these perceptions (F-ratio 80.939 and p-value 0.000). Our results coincide with that presented by Nunkoo et al. (Citation2010), who stated that residents with a high occupational identity would be more likely to see tourism as a negative impact (). In this sense, these authors remind Lindberg and Johnson (Citation1997) affirming that the development of tourism can diminish the presence of the traditional industry, and therefore it may be that people who work outside the tourist area have a more negative perception of tourism.

5. Conclusions

This research examined the resident’s perception of the quality of contact with tourists in Santiago de Compostela, one of the world’s foremost pilgrimage capitals. Understanding residents’ perceptions about the quality of contact with tourists is essential. A good relationship between the locals and the visitors is crucial to the success of the tourism activity in the destination. Locals are the ones who interact with tourists, and they hold the power to persuade the tourist to return or not return to the destination. If the relationship is positive, the locals can express higher hospitality, which will affect the tourist’s experience.

According to the empirical results extracted from the survey conducted with the residents of Santiago de Compostela in 2018, we concluded that the more the intensity of this contact increases, the more the probability of the resident also seeing disadvantages in this contact. In this sense, our results coincide with those of Nunkoo et al. (Citation2010), (Citation2013), which indicate that the general perception of tourism impacts for residents involves a mental calculation of the benefits and costs of tourism in the design of their daily lives. In their studies, the authors pointed out that although residents derive economic benefits from tourism, they also feel the negative aspects of tourism in their communities. This finding indicates the importance of integrating the different theoretical lenses to understand the residents’ perception of the impacts of tourism. This corroborates specific points presented here expressed in our work.

The analysis of the data shows that, concerning the contact (positive-negative-indifferent), in general, it is more favorable (50.9%) than negative (36.3%). However, we found that the more the degree of interaction between residents and tourists increase (measured in the frequency of contact), the more the negative perception of tourism increases. This may be because Santiago is a consolidated tourist destination, with tourist pressure per inhabitant of the highest in Spain. Thus, however is positive the impression the resident gets from tourism to the city, the fact that they see their habits constantly altered affects the relationship with the intruder, in this case, the tourist.

Despite this perception of positive contact between residents and tourists, it is worth highlighting the relevance given by residents to harmful contact since a relatively significant portion believes that the relationship between tourists and residents is negative. This, in a way, is worrying. If we transfer this result to the total population, more than 1/3 of them perceive a positive contact with the tourist. It demonstrates a space for political action to allocate measures to improve the relationship between tourists and residents. In this case, actions would be necessary to minimize and/or solve existing problems and reduce the negative impacts of tourism in the city.

It also must be noted that in our results, we found differences between perceptions if we consider the resident’s bond with the tourism industry. This result coincides with that proposed by Nunkoo et al. (Citation2010), who states that residents with a high occupational identity are more likely to perceive the negative impacts of tourism.

Finally, considering the Holy Year 2021–2022, and the more significant influx of tourism in the city, in future research, it is recommended to check, by 2023, the consistency of the residents’ perceptions about the impacts of tourism to generate a comparative picture. In addition, it would also be essential to check whether the assessment of the relationship with the tourist is altered after a significant event like this. As a limitation, we could highlight that although the sample is significant, with a large volume of responses, there is an over-representation of the age group from 25 to 65 years old, with a small presence of responses from those over 65 years old. Thus, the adults are the ones who interact the most with the tourists. Therefore, it is relevant to have a higher rate of response in this group.

The results obtained are useful for local and for regional planners. In the present COVID-9 pandemic, the planners are the ones that must be redefining the strategy of the tourism sector carefully. Spain has shown, in 2020 and 2021, to be one of the countries that has suffered more with the cases of COVID-19 and corresponding deaths. Santiago de Compostela is a relevant tourist destination in Spain, and additional sanitary guarantees must be offered to locals and visitors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jakson Renner Rodrigues Soares

Jakson Renner Rodrigues Soares is principal investigator of the Tourism Experience Research Group (University of A Coruña) and the Tourism, Economy and Sustainability Research Group (State University of Ceará). The authors have published other works resulting from research on the impacts of tourism. The Principal Investigator has been hired as a postdoctoral fellow with public funding from FUNCAP-Capes (Brazil) from 2018 to 2020 investigating innovation in the community tourism network and its contribution to the development of the territory. In addition, it has obtained financing in competitive calls to investigate different perspectives of tourism, such as the Impacts of tourism in Santiago de Compostela (Chair of the Camino de Santiago and Pilgrimages) and the Presence of women in the Galician tourism sector (Deputación da Coruna). The group is interested in research on the Tourist Experience considering different points of view: the industry, the host community and tourists.

References

- Almeida-García, F., Cortés-Macias, R., Peláez-Fernández, M., & Balbuena-Vázquez, A. (2015). Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tourism Management, 54, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.007

- Almeida, F., & Balbuena, A. (2014). Mar del Plata (Argentina) y Málaga (España). Estudio comparado de dos destinos turísticos. (Mar del plata (Argentina) and Malaga (Spain). Comparative study of two tourist destinations). Pasos Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 12(2), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2014.12.023

- Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001

- Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

- Ap, J., & Crompton, J. (1993). Residents’ strategies for responding to tourism impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 32(1), 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759303200108

- Ashworth, G. (2009). Questioning the Urban in Urban tourism. In G. Maciocco & S. Serreli (Eds.), Enhancing the city. Urban and landscape perspectives (pp. 6). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2419-0_11

- Ashworth, G., & Page, S. J. (2011). Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tourism Management, 32(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.02.002

- Besculides, A., Lee, M., & Mccormick, P. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00066-4

- Brida, J., Osti, L., & Barquet, A. (2010). Segmenting resident perceptions towards tourism – A cluster analysis with a multinomial logit model of a mountain community. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(5), 591–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.778

- Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00003-1

- Buhalis, D., & O’Connor, P. (2005). Information Communication Technology Revolutionizing Tourism. Journal Tourism Recreation Research, 30(3), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2005.11081482

- Bujosa, A., & Rossello, J. (2007). Modelling environmental attitudes toward tourism. Tourism Management, 28(3), 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.004

- Butler, R. W. (2006). The concept of a tourist area life cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. In R. Butler. (Ed.), The tourism area life cycle: Applications and modifications, (pp. 336). Channel View Publications. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845410278-007

- Campón-Cerro, A. M., Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., & Folgado-Fernández, J. A. (2019). Quality of Life (QOL) in Hospitality and tourism marketing and management: An approach to the research published in high impact journals. In A. M. Campón-Cerro, J. M. Hernández-Mogollón, & J. A. Folgado-Fernández (Eds.), Best practices in hospitality and tourism marketing and management. Applying quality of life research (pp. 3–22). Springer.

- Cañizares, S., Tabales, M., & Garcia, F. (2014). Local residents’ attitudes towards the impact of tourism development in Cape Verde. Tourism& Management Studies, 10(1), 87–96. https://www.tmstudies.net/index.php/ectms/article/view/652

- Carballo Cruz, E., Fernández García, O., & Santana Alfonso, R. (2012). Los impactos del turismo percibidos por la comunidad. Municipio Morón, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, 21(5), 1299–1317. http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?pid=S1851-17322012000500013&script=sci_arttext

- Carneiro, M. J., Eusébio, C., & Caldeira, A. (2018). The influence of social contact in residents’ perceptions of the tourism impact on their quality of life: A structural equation model. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 19(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2017.1314798

- Coco, A. (2017). Las ciudades tienen derecho a decidir el tipo de turismo que quieren recibir. Vi Encuentro Gestores de Patrimonio Mundial. http://www.abc.es/espana/galicia/abci-ciudades-tienen-derecho-decidir-tipo-turismo-quieren-recibir-201703301103_noticia.html

- Concello de Santiago. (2018). TURISMO: Preséntase o Plan Estratéxico do Turismo de Santiago no Consello Municipal (TOURISM: Santiago’s Strategic Tourism Plan is presented at the Municipal Council). http://santiagodecompostela.gal/hoxe/nova.php?lg=gal&id_nova=17036

- Dias, R., & Cassar, M. (2005). Fundamentos do marketing turístico. Tourism marketing. Pearson.

- Díaz-Sarmiento, C., López-Lambraño, M., & Roncallo-Lafont, L. (2017). Entendiendo las generaciones. Una revisión del concepto, clasificación y características distintivas de los Baby Boomers, X Y Millennials. CLIO América, 11(22), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.21676/23897848.2440

- Diedrich, A., & García, E. (2009). Local perceptions of tourism as indicators of destination decline. Tourism Management, 30(4), 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.009

- Dogan, H. Z. (1989). Forms of adjustment: Sociocultural impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(2), 216. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(89)90069-8

- Doxey, G. (1975). A causation theory of visitor- resident irritants. Methodology and Research Inferences, Travel and Tourism Research Associations Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings. San Diego, TTRA.

- Erul, E., Woosnam, K. M., Ribeiro, M. A., & Salazar, J. (2020). Complementing theories to explain emotional solidarity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1800718

- Eshliki, S., & Kaboudi, M. (2012). Community perception of tourism impacts and their participation in tourism planning: A case study of Ramsar, Iran. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 36, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.037

- Farid, S. (2015). Tourism in world heritage sites and its impact on economic development: Some African countries case studies. Proceedings of the II International Conference on Best Practices in World Heritage: People and Communities. Session 5. https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/41699/1/TourismWorldHeritageSites.pdf

- Faulkner, B., & Tideswell, C. (1997). A framework for monitoring community impacts of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 5(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589708667273

- Gabriel, L. P. M. C., Soares, J. R. R., & Godoi, C. K. (2017). O uso turístico do património: Congruências e incongruências no discurso de residentes e não residentes de uma cidade património da humanidade. (The tourist use of heritage: Congruences and incongruencies in the discourse of residents and non-residents of a World Heritage City). In H. Pina & F. Martins (Eds.), Sociedade, Economia e Património num Cenário Tendente a uma Maior Coesão Territorial (pp. 214–228). FLUP.

- García Gómez, C., Bolio Rosado, M. I., & Navarro Favela, M. A. (2018). Turismoy sus impactos: Sociales, económicos y ambientales (Tourism and its impacts: Social, economic and environmental). Conacyt.

- García López, A. M., Marchena Gómez, M. J., & Morilla Maestre, A. (2018). About the opportunity of tourist taxes: the case of Seville. Cuadernos de Turismo, 42(42), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.6018/turismo.42.07

- Getz, D. (1994). Residents‘ attitudes towards tourism. Tourism Management, 15(4), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(94)90041-8

- Goffi, G., Cucculelli, M., & Masiero, L. (2019). Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 209 (1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.208

- Gu, M., & Wong, P. P. (2006). Residents’ perception of tourism impacts: A Case Study of homestay operators in Dachangshan Dao, North-East China. Tourism Geographies, 8(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680600765222

- Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2019). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality of Marketing & Management, 28(3), 306–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2018.1516589

- Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.008

- Hadinejad, A., Moyle, B. D., Scott, N., Kralj, A., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A review. Tourism Review, 74(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-01-2018-0003

- Han, G., Fang, W. T., & Huang, Y. W. (2010). Classification and influential factors in the perceived tourism impacts of community residents on nature-based destinations: China’s tiantangzhai scenic area. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 10, 2010–2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2011.09.315

- IGE. (2017). Indicador da intensidade da demanda turística. (Indicator of the intensity of tourist demand). Instituto Galego de Estatística.

- INE. (2018). Habitantes empadronados en el Municipio de Santiago de Compostela (Inhabitants registered in the Municipality of Santiago de Compostela). Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- Jaafar, M., Noor, S., & Rasoolimanesh, S. (2015). Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: A case study of the Lenggong world cultural heritage site. Tourism Management, 48, 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.018

- Jaafar, M., Rasoolimanesh, S., & Lonik, K. (2015). Tourism growth and entrepreneurship: Empirical analysis of development of rural highlands. Tourism Management Perspectives, 14, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.02.001

- Jackson, L. (2008). Residents’ perceptions of the impacts of special event tourism. Journal of Place Management and Development, 1(3), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538330810911244

- Ko, D. W., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management, 23(5), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00006-7

- Kuvan, Y., & Akan, P. (2005). Residents’ attitudes toward general and forest-related impacts of tourism: The case of Belek, Antalya. Tourism Management, 26(5), 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.02.019

- Lankford, S. V., & Howard, D. R. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90008-6

- Latkova, P., & Vogt, C. (2012). Residents’ attitudes toward existing and future tourism development in rural communities. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510394193

- Lindberg, K., & Johnson, R. L. (1997). Modeling resident attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 402–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80009-6

- Liu, C.-H., & Yen, L.-C. (2010). The effects of service quality, tourism impact, and tourist satisfaction on tourist choice of leisure farming types. African Journal of Business Management, 4(8), 1529–1545. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM

- Lopes, H., Remoaldo, P., & Ribeiro, V. (2019). Residents’ perceptions of tourism activity in a rural North-Eastern Portuguese community: A cluster analysis. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series, 46(46), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.2478/bog-2019-0038

- Madrigal, R. (1995). Residents’ perceptions and the role of government. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00070-9Get

- Marrero Rodríguez, J. R., & Huete Nieves, R. (2013). Residents’ attitudes toward tourism employment in the region of Valencia (Spain). Cuadernos de Turismo, 32(1), 327–328. https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/177521

- Mathieson, A., & Wall, G. (1982). Tourism, economic, physical and social impacts. Longman.

- McDwall, S., & Choi, Y. (2010). A comparative analysis of Thailand residents’ perception of tourism impacts. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 11(1), 36–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15280080903520576

- McGehee, N., & Andereck, K. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268234

- Md Khairi, N. D., Ismail, H. N., & Syed Jaafar, S. M. R. (2018). Tourist behaviour through consumption in Melaka World Heritage Site. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(5), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1491534

- Md Khairi, N. D., Ismail, H. N., & Syed Jaafar, S. M. R. (2020). Embracing tourist behaviour in managing Melaka WHS IOP Conf. In Series: Earth and environmental science (Vol. 447, pp. 1–12). IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/447/1/012035

- Milito, M., Marques, S., & Alexandre, M. (2013). Percepção do Residente em Relação a Turismo e Megaevento: Análise bibliométrica de periódicos internacionais e latino-americanos. Revista Turismo em Análise, 24(3), 482–502. https://doi.org/10.11606/.1984-4867.v24i3p482-502

- Monjardino, I. (2009). Indicadores de sustentabilidade do turismo nos Açores: O papel das opiniões e da atitude dos residentes face ao turismo na região. (Indicators of sustainability of tourism Açores: The role of residents’ opinions and attitudes concerning tourism in the region). Paper presented at the 15 Congresso da APDR –. Redes e Desenvolvimento Regional, Praia, Cabo Verde.

- Monterrubio-Cordero, J. C. (2008). Residents’ perception of tourism: A Critical theoretical and methodological review. Ciencia Ergo Sum, 15(1), 35–44. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26549454_Residents_Perception_of_Tourism_A_Critical_Theoretical_and_Methodological_Review

- Navarro Favela, M. A., Sauri Palma, C. A., & Medina Martín, C. S. (2018). Percepción comunitaria de los usos cotidianos y turísticos del patrimonio en la ruta de Las Iglesias de Quintana Roo (Community perception of the daily and tourist uses of heritage on the route of Las Iglesias de Quintana Roo). In C. García Gómez, M. I. Bolio Rosado, & M. A. Navarro Favela (Eds.), Turismo y sus impactos: Sociales, Económicos y Ambientales (pp. 22–46). Conacyt.

- Nunkoo, R., Gursoy, D., & Juwaheer, T. D. (2010). Island residents’ identities and their support for tourism: An integration of two theories. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(5), 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003602341

- Nunkoo, R., Smith, S. L. J., & Ramkissoon, H. (2013). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.673621

- Organización Mundial del Turismo. (2018). La contribución del turismo a los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible en Iberoamérica (The contribution of tourism to the sustainable development goals in Ibero-America). OMT. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420018

- Oviedo, M. A., Castellanos, M., & Martin, D. (2008). Gaining residents’ support for tourism and planning. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.644

- Pacheco, J. M. S., Silva, E. V., & Cestaro, L. A. (2019). Use of environmental perception to identify the impacts associated with tourism in the community of Emboaca, Trairi/CE. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais, 10(2), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.6008/CBPC2179-6858.2019.002.0025

- Palmer-Tous, T., Riera-Font, A., & Rosselló-Nadal, J. (2007). Taxing tourism: The case of rental cars in Mallorca. Tourism Management, 28(1), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.11.015

- Perinotto, A. R. C., & Santos, A. K. P. (2011). Heritage and tourism: A case study on the relationship among Parnaíba/Pi dwellers and “Porto das barcas” complex. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 5(2), 201–225. https://doi.org/10.7784/rbtur.v5i2.413

- Petrzelka, P., Krannich, R. S., Brehm, J., & Koons, C. (2005). Rural tourism and gendered nuances. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1121–1137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.04.007

- Pizam, A. (1978). Tourist impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. Journal of Travel Research, 16(4), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757801600402

- Pizam, A., & Milman, A. (1984). The social impacts of tourism.UNEP. Industry and Environment, 7(1), 11–14.

- Rasoolimanesh, S., Jaafar, M., Kock, N., & Ramayah, T. (2015). A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.019

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ringle, C. M., Jaafar, M., & Ramayah, T. (2017). Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tourism Management, 60, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.019

- Remoaldo, P., Duque, E., & Ribeiro, J. C. (2015). The environmental impacts of hosting the “2012 Guimarães European capital of culture” as perceived by the local community. Ambiente y Desarrollo, 19(36), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.ayd19-36.eihg

- Rothman, R. (1978). Residents and transients: Community reaction to seasonal visitors. Journal of Travel Research, 16(3), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757801600303

- Roxas, F. M. Y., Rivera, J. P. R., & Gutierrez, E. L. M. (2020). Framework for creating sustainable tourism using systems thinking. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1534805

- Royo, M., & Ruiz, M. E. (2009). Resident attitude towards tourism and visitor: Determinant factors in rural-cultural tourism and excursionism. Cuadernos de Turismo, 23(1), 217–236. https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/70111

- Santiago Turismo. (2019). Presentación de Santiago de Compostela (Presentation of Santiago de Compostela). http://www.santiagoturismo.com/info-xeral/presentacion

- Scalabrini, E., & Remoaldo, P. (2020). Residents’ perception towards tourism in an industrial Brazilian city: A cluster analysis. Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional, 16(1), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.54399/rbgdr.v16i1.5359

- Schmid, C. (2012). Theory production of space by Henri Lefebvre: Toward a three – Dimentional dialetic. GEOUSP, 32(32), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.11606/.2179-0892.geousp.2012.74284

- Sharma, B., & Dyer, P. (2009). An investigation of differences in residents’ perceptions on the Sunshine Coast: Tourism impacts and demographic variables. Tourism Geographies, 11(2), 187–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680902827159

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Soares, J. R. R., Remoaldo, P., Perinotto, A. R. C., Gabriel, L. P. M. C., Lezcano-González, M. E., & Sánchez-Fernández, M. D. (2022). Residents’ perceptions regarding the implementation of a tourist tax at a UNESCO world heritage site: A cluster analysis of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Land, 11(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020189

- Su, R., Bramwell, B., & Whalley, P. A. (2018). Cultural political economy and urban heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 68(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.004

- Tosun, C. (2002). Host Perceptions of Impacts: A Comparative Tourism Study. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00039-1

- Valencia. (2017). Un estudio revela que el turismo es la principal causa del ruido nocturno estival en Valencia. (A study reveals that tourism is the main cause of summer night noise in Valencia). ABC Espanha. https://www.abc.es/espana/comunidad-valenciana/abci-estudio-revela-actividad-turistica-y-vacacional-principal-causa-ruido-nocturno-verano-201708301742_noticia.html

- Vareiro, L., Remoaldo, P. C., & Cadima, J. (2013). Residents’ perceptions towards tourism impacts in the Northern Portugal using cluster analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(6), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.707175

- Vareiro, L., Santos, J. F., Remoaldo, P. C. A., & Cadima Ribeiro, J. (2016). Evaluating the Guimaraes 2012 European Capital of Culture national and international tourists’ behaviors and perceptions. Event Management, 20(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599516X14538326025152

- Vodeb, K., Fabjan, D., & Krstinić Nižić, M. (2021). Residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and support for tourism development. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 27(1), 143–166. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.27.1.10

- Wall, G., & Mathieson, A. (2006). Tourism: Change, impacts and opportunities. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Williams, J., & Lawson, R. (2001). Community issues and resident opinions of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00030-X

- World Tourism Organization. (2018). Tourism and Culture Synergies. UNWTO.

- Xacopedia. (2015). A orixe do Xacobeo (The origin of Xacobeo). https://xacopedia.com/Xacobeo

- Yang, Y., Xue, L., & Jones, T. E. (2019). Tourism-enhancing effect of World Heritage Sites: Panacea or placebo? A meta-analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 29–41. accessed May 05 2021, Available from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329871673_Tourism-enhancing_effect_of_World_Heritage_Sites_Panacea_or_placebo_A_meta-analysis

- Zhang, J., Inbakaran, R. J., & Jackson, M. (2006). Understanding community attitudes towards tourism and host-guest interaction in the Urban-rural Border Region. Tourism Geographies, 8(2), 182–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680600585455