Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2019 has posed an unprecedented threat to the global economy. Due to the pandemic, the hotel industry has undergone fundamental changes. In particular, social distancing technology (SDT) has become an indispensable tool in this industry and has played a vital role in its recovery. This study explores the factors that affect customer trust in using SDT in hotels during COVID-19 and how this trust affects their booking intention. The research uses social exchange theory (SET) as the theoretical basis and measures the benefits and perceived risks of using SDT through the benefit-risk method. In addition, the technology acceptance model (TAM) is introduced, and two attributes are added: perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. A total of 437 questionnaires were distributed, of which 405 were valid. Research results show that benefits, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use positively affect trust in SDT, while privacy concerns have a negative impact. Health risks and social rewards are not directly related to trust in SDT.This study provides ideas for future research on the health aspects of SDT by studying the benefits and health risks brought about by its use. For relevant practitioners, hotels should reasonably incorporate SDT into their daily operations and conduct regular disinfection to reduce the risks caused by direct and indirect contact to protect the lives and health of both customers and workers.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research background

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2019 has posed an unprecedented threat to the global economy, and the presence of COVID-19 has led to fundamental changes in the hotel industry. As the hotel industry is characterized by a high risk of infection, the business hours, scale and a series of activities of hotels have significantly reduced or closed down (Gursoy & Chi, Citation2020). Therefore, the hotel industry is one of the most affected industries by COVID-19 (Zemke et al., Citation2015).

According to data released by China Hotel Association, the average revenue loss of the hotel industry has reached 67.81% since the outbreak of the pandemic. More than 89% of the hotel revenue loss is higher than average. The main reason is that COVID-19 is highly infectious and can harm people’s life and health. This leads people to take self-protection measures, such as reducing travel and minimizing contact with others to reduce the risk of infection. A series of emerging technologies can play an important role in facing these challenges (Jones & Comfort, Citation2020).

Social distancing technology has been adopted to reduce the risk of infection and ensure the health and safety of customers (Kussmann, 2020). Many large chain luxury hotels have begun to adopt AI intelligent robots, which can help guests check-in, provide room service, help with disinfection and so on. Some advantages of using social distancing technology include: (1) it can maintain proper social distance and reduce health risks; and (2) it can be managed more efficiently (Nguyen, Saputra, Van, Nguyen, Khoa, Nguyen et al., Citation2020).

However, the application of social distancing technology (SDT) in Macau’s hotel industry is still immature and has not yet become popular. Most hotels in Macau are luxury hotels. Adopting social distancing technology may change the way services were originally provided. Therefore, customer intention cannot be ignored when using social distancing technology.

Technology in hotels has always been a popular topic in research. Most of the literature is more focused on the effectiveness of hotel technology in providing services and enhancing the consumer experience (Krishnan et al., Citation1996; Morosan & DeFranco, Citation2019; Rahimi, Citation2017). Several studies examined the pandemic’s effects on hospitality with the outbreak of the epidemic (Jiang & Wen, Citation2020; Jones & Comfort, Citation2005; J. Zhang et al., Citation2020) and how hotels are preventing the spread of the virus and acknowledging the important role of technology in reducing interaction between guests and hotel staff (Kussmann, 2020; Garcia, 2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2020). However, customers are the ones who use this technology, so their level of trust is necessary for increased application.

This research aims to explore the important factors that affect customer trust in social distancing technology and the relationship between these factors and trust and customer booking intention. It provides the basis for the management and technical improvement of the hotel industry during the pandemic. It provides strategies on how to create a safe hotel environment for customers, thus promoting the recovery of the hotel industry.

This study is based on four dimensions (benefits, health risks, social rewards, and privacy concerns) of the attributes of SDT, which were identified in the study of Social Distance Technology by Morosan and DeFranco (Citation2021). It also adds perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness as per the technology acceptance model (TAM). Based on the research background and purpose, this study poses the following research questions: Is the customer’s trust in social distancing technology influenced by these six factors? Will these factors and trust further affect customers’ hotel booking intention?

2. Literature review

2.1. Social distancing technology (SDT)

Social distancing is defined as using a range of non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce the frequency and closeness of person-to-person contact and distance during a pandemic, e.g., high-risk group quarantine, closing large events, controlling the movement of people, etc. (Kelso et al., Citation2009). Social distancing technology (SDT) is information technology used to reduce the frequency, closeness and contact between people at potentially risky sources of outbreaks, such as self-service check-in kiosks in airports. Through pre-printed boarding passes, customers can reduce contact with airport employees (Shin & Perdue, Citation2019). There are also WeChat mobile payment, Alipay mobile payment, and other similar applications that can be used to avoid contact and reduce the probability of virus transmission. Restaurants are using automated delivery services and QR codes to order food. Robots are used to automatically deliver food to the table (Morosan & DeFranco, Citation2021). SDT is now widely used and has reduced the inconvenience caused by epidemic prevention measures.

Some scholars divide SDT into two aspects. One is related to the benefits it brings to the hotel industry (Sorrells, Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2020; Krishnan et al., Citation1996; Sharma, Shin, María, & Nicolau, Citation2021), and the other is the risk posed by its use (Tu et al., Citation2018; Ha, Shakur, & Do, Citation2020).

2.2. Social exchange theory (SET)

The concept of social exchange theory (SET) was first proposed by G. C. Homans (Citation1958), who believed that social exchange was a process of resource exchange between people, in which the resources may be tangible or intangible, such as time, money, family, status and reputation (Y. S. Chen & Chang, Citation2013). Blau (Citation1964) pointed out that social exchange is a reciprocal behavior between two parties. Since there is no clear stipulation of responsibilities and obligations, there are risks and uncertainties in social exchange (Molm et al., Citation2000), which leads to trust between the two parties.According to SET, individuals proactively seek to maximize their benefits and minimize costs when exchanging resources with others (Molm, Citation1997). Benefits refer to those resources one receives as a result of a social exchange or a positive outcome. Cost refers to those resources one gives away during a social exchange or any adverse outcome of an exchange (Kankanhalli et al.). The tenets of SET have an important implication for the current study. Studies have underlined the major source of cost in information technology use as risks, which may be due to information security and privacy threats (S. Chen & Williams, Citation2009; Casaló & Romero, Citation2019; Qin et al., Citation2009). The downside to this study is the health threat and risk to consumers. Therefore, a benefit-risk theoretical framework is constructed to discuss consumer trust in the hotel industry’s use of epidemic prevention technology (Morosan & DeFranco, Citation2021).

SET is widely used in business and hospitality settings (Rather & Hollebeek, Citation2019; Kim, So & Wirtz, Citation2022). This study focuses on the principle of reciprocity in SET and conducts research based on a benefit-risk framework by measuring the benefits customers receive and the risks they face when participating in activities. These two important factors are evaluated in this study to examine their effect on customer trust in SDT and customer booking intention (H. K. Wang et al., Citation2015). People choose to maintain this exchange relationship only when the expected benefits outweigh the risks (Golder, Wilkinson & Huberman, Citation2007). This benefit-risk approach is important during COVID-19, as consumers may use it to change their incentives to purchase services, and managers may adjust their management strategies and approaches to deal with the new business, economic, and social conditions, as well as new anti-epidemic policies (Liu et al., Citation2021; Yang & Han, Citation2021).

2.3. Technology acceptance model (TAM)—perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness

Davis (Citation1989) designed the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) based on rational behavior theory. Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are the determinants of TAM. Perceived ease of use is defined by Davis (Citation1989) as the degree to which people believe technology can be used without effort, while perceived usefulness is the degree to which it increases the corresponding efficiency when using technology. A study by Israel Jeng(Citation2019) pointed out that in a large number of analytical TAM on the factors of virtual technology use in the hotel industry, perceived usefulness has a certain impact on customer hotel booking intention. In addition, Sahli and Legohérel (Citation2016) also proposed a framework to test the influencing factors of customers’ online hotel booking intention and found that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are important.

Although SET is used to predict and explain attitude problems, it lacks theoretical complexity. Therefore, this study explores the theoretical connotation of SET and combines it with other theories (C. Zhang et al., Citation2021). Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (Citation2011) believe that trust is an important factor in SET, but they are not included in the previous model. Pappas (Citation2014 believes that combining SET and other important variables can help improve the predictive power of the model.

TAM is one of the most widely used models for studying new information technology adoption (Davis, Citation1989; Venkatesh & Davis, Citation1996). TAM suggests that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use regarding new things can affect a person’s attitude toward the acceptance of that technology (Akbari et al., Citation2020; Cheung & Vogel, Citation2013; Davis et al., Citation1989; Yudiarti & Puspaningrum, Citation2018). To further increase the precision of the conceptual framework, this study adds a theoretical structure (TAM) that accurately describes the perception (usefulness, ease of use) of consumer systems.

This study considers benefits, health risks, social rewards, and privacy concerns in SET as external factors influencing consumers. The perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of the TAM are internal factors for consumers’ perception of new technologies. Therefore, this study combines SET and TAM. Through a combination of internal and external factors, consumer trust in social distancing technologies and behavioral intentions under COVID-19 are provided with a detailed framework.

2.4. Trust

Trust is a concept with many concepts and complex structures. In SET, trust is defined as the expectation that exchange partners will behave in good faith based on positive perceptions and willingness in situations of uncertainty and risk. The development of trust can only occur when there is a certain risk in the relationship between the parties (Molm et al., Citation2000).

Over time, consumer choice and use of technology have become more routine, but many studies have shown uncertainty in most economic and social exchanges. The element of trust needs to be the basis of an exchange relationship. Coleman (Citation1988) highlights the importance of trust in exchange relationships as it boosts the confidence of the parties involved in the exchange.

Social theory also states, “trust is the foundation of exchange behavior between individuals” (Zhao et al., Citation2017, p. 373). Ponnapureddy et al. (Citation2017) found that when customers have positive trust in a product, it has a positive impact on the perceived usefulness of the product and hotel booking intention. In addition, findings show that trust is a key variable when participating in social exchange. That is, customers’ higher trust in services leads to a higher desire to use the service (Boateng et al., Citation2019).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people have felt uneasy and skeptical about travel due to concerns about their safety and health (Akbari et al., Citation2020). It has caused people to restrict and avoid travel. New technologies for epidemic prevention may change people’s psychological concerns and enhance travel confidence (Park, Citation2020; Kussmann, 2020). Therefore, it is crucial to understand people’s attitudes towards new technologies for epidemic prevention. Drawing on the reciprocal perspective of SET, some scholars have discussed the relational and psychological states of consumers towards hotel intelligent technology (Pillai & Sivathanu, 2020; Wirtz et al., Citation2018). Findings reveal significant positive effects of perceived intelligence, perceived social presence, and perceived social interactivity on trust, leading to usage intentions (H. Kim et al., Citation2022). Hence, based on the benefit-risk framework of SET, we explore the trust customers have in hotel technology and measure the benefits and risks they receive when participating in activities using this technology.

2.5. Factors influencing customer trust in social distancing technology

2.5.1. Benefits and health risks

In the past literature, we have found that consumers evaluate the use of technology through a benefit-risk framework based on a reliable conceptualization of the benefits of that technology (Zeithaml, Citation1988). The conceptualization of the benefits of technology is the need to capture the use of specific functions to facilitate a task (Kim & Lee, Citation2008). In this paper, the benefit is defined as the ability of customers to effectively maintain social distance when using SDT in the hotel, reducing the risk of infection and protecting their physical and mental health and safety (Metzger, Citation2006). In the context of COVID-19, SDT is deployed in hotels to effectively promote social distancing. For example, service robots in hotels effectively maintain social distancing without having to contact staff, effectively reducing the risks that may arise during contact.

Health risk comes from a dimension in risk theory, divided into physical and psychological aspects by Suhartanto et al. (Citation2021). Personal anxiety and worry caused by COVID-19 are regarded as psychological health problems. This study defines health risk as the negative physical and emotional impact on customers using SDT.

Past research has shown that perceived risk will negatively affect customer behavioral intentions. For example, when consumers perceive a product as high risk, they will be reluctant to trust it (Y. S. Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Corritore, Kracher, & Wiedenbeck, Citation2003; Eid, Citation2011; Harridge‐March, Citation2006; Rehman, Baharun, & Salleh, Citation2020). In addition, research by Y. S. Chen and Chang (Citation2013) shows that mental health problems such as anxiety and worry can also negatively affect trust. In the context of COVID-19, the deployment of SDT in hotels is to reduce the risk of infection through contactless payment, hotel service robots and other facilities. However, while certain risks are reduced, such technologies cannot ensure zero contact. Based on this, our study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The benefits of using social distancing technology in hotels have a positive impact on their trust.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The health risks of using social distancing technology in hotels have a negative impact on their trust.

2.5.2. Social rewards and privacy concerns

In the past, we have found that consumers use a benefit-risk framework to calculate their decisions when using a certain technology. This is called privacy computing, which consists of two components: social rewards and privacy concerns. A person uses privacy computing to balance privacy concerns with tangible benefits; that is when consumers are faced with a decision whether to use a certain technology or not.

A social reward is the happiness, comfort and satisfaction that a person obtains through participating in a relationship (Jiang et al., Citation2013). In social interaction, bound by the principle of reciprocity, people will exchange information fairly, and when this relationship is beneficial, people will make more efforts to maintain this relationship. This can further develop and gradually evolve into trust (Blau, Citation1964; Lawler & Thye, Citation1999). For example, in a survey of location-based services, it was found that the willingness of customers to disclose personal information was influenced by corresponding rewards (Milne & Gordon, Citation1993).

Privacy concerns are defined as a person’s fear of privacy leakage and abuse when faced with information exchange (Li et al., Citation2011). Research on consumer privacy found that privacy concerns affect the level of trust customers place in a technology or system. The privacy-trust-willingness model established by Liu, Marchewka, Lu, and Yu (Citation2005) proved that privacy affects trust, and trust affects consumers’ willingness to act. M. K. Kim et al. (Citation2015) also showed that strengthening relevant privacy protection policies will increase people’s trust in websites. In a study by Gashami, Chang, Rho, and Park (Citation2016), it was proved that customers’ privacy concerns have a negative impact on supplier trust. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The social reward of using social distancing in hotels has a positive impact on their trust.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The privacy concerns of using social distancing technology in hotels have a negative impact on their trust.

2.5.3. Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness

Lee and Jun (Citation2007) pointed out that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are important predictors of consumer trust in mobile transactions. In the research on trust in the field of e-commerce, it is found that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are helpful for consumers to understand what is currently happening. It is easy for them to understand processes, and this can have a positive impact on building trust (Kumar, Citation1996). Gefen et al. (Citation2003) found that perceived ease of use has a significant impact on customers’ attitudes toward trusting a website, and customers will ultimately increase or decrease their trust in the system because of this ease of use. Hence, customer trust is directly affected by perceived ease of use. In addition, Ponnapureddy et al. (Citation2017) found an interaction between trust and perceived usefulness; that is, when people perceive a product to be effective, their trust in the product increases. Therefore, a strong correlation exists between perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness and trust. In summary, the following assumptions are made:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). The perceived ease of use of using social distancing in hotels has a positive impact on their trust.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). The perceived usefulness of using social distancing technology in hotels has a positive impact on their trust.

2.6. Intention to book hotels

2.6.1. Concept of hotel booking intention

Hoyer, MacInnis and Pieters (Citation2012) define behavioral intention as a person’s behavior toward something or an individual’s willingness to behave in a desired manner. Behavioral intentions are also described as emotional dispositions and behaviors that consumers have after experiencing/using a product or service (Davis et al., Citation1992). The hotel booking intention in this study is defined as the customer’s positive evaluation of the hotel, their willingness to recommend the hotel to others, and their willingness to book the hotel again.

2.6.2. Relationship between perceived ease of use, Perceived usefulness, trust, and booking intention

Research shows that consumer trust is an important factor that affects online shopping and consumers’ behavioral tendencies (Kim & Lee, Citation2008). Bijlsma-Frankema and Woolthuis (Citation2005) believe that consumers will buy more products from a trusted party than from an untrusted party. In the hotel industry, consumers are very cautious when booking hotels, hoping to reduce the uncertainty of products or services by collecting enough information (Ladhari & Michaud, Citation2015). Pavlou and Gefen’s (Citation2004) research shows that when consumers trust hotels, they will perceive a lower risk when booking and their willingness to book will also be higher. Based on this, our study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Trust in using social distancing technology has a positive impact on booking intention.

Sahli and Legohérel (Citation2016) proposed a framework to examine the influencing factors of customers’ online hotel booking intention and proved the impact of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use on hotel booking intention. Israel et al.’s (Citation2019) research pointed out that in a large number of analyses, TAM factors on the use of virtual technology in the hotel industry and perceived usefulness have a certain impact on customers’ hotel booking intention. Although some studies suggest that perceived usefulness has a greater impact on customer behavior intention than perceived ease of use, the relationship between perceived ease of use and behavior intention is positively correlated (Huang et al., Citation2019). Based on this, our study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Perceived ease of use of using social distancing technology has a positive impact on booking intention.

Hypothesis 9 (H9). Perceived usefulness of using social distancing technology has a positive impact on booking intention.

3. Research design

3.1. Research design

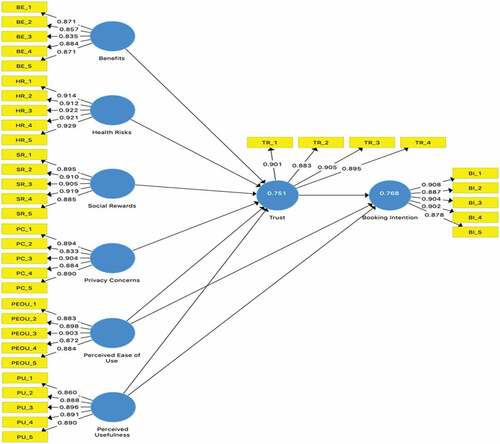

This study mainly explores the factors that affect customer trust in using SDT in hotels during the COVID-19 period and how customer trust in SDT affects customer booking intention. Therefore, the four dimensions (benefits, health risks, social rewards, and privacy concerns) of the attributes of SDT will be identified by adopting the research of Morosan and DeFranco (Citation2021) as the basis. This study uses SET as a theoretical basis to measure the perceived benefits and risks of using social distancing techniques by calculating the benefit-risk approach, conceptualizing the perceived benefits and social rewards of using social distancing techniques as benefits; health risks and privacy concerns perceived by social distancing technologies are conceptualized as risks (Morosan, Citation2018). In addition, the TAM (Davis, Citation1989) is also introduced, adding two properties: perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. Customer trust in SDT was measured by measuring these six factors to understand how these factors affect customers’ trust in SDT and explore the relationship between these factors with trust and booking intention. The research hypothesis diagram is shown in .

3.2. Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was designed by sorting out and summarizing the relevant literature on eight variables. These include benefits, health risks, social rewards, privacy concerns, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, trust, and hotel booking intention. Information about these variables in literatures is in English, but the questionnaire is distributed in Macau, China. Most customers are from mainland China. Therefore, to make the respondents understand the items of the questionnaire better, all English items were translated into Chinese. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part uses a seven-point Likert scale and contains 39 items related to the eight variables. The second part collects the basic information of the individual for analysis of the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

3.3. Sample collection

In November 2021, a pre-survey was conducted. A total of 130 questionnaires were distributed, of which 122 were valid responses. Through statistical software analysis, the alpha coefficient of the pre-questionnaire was between 0.813 and 0.942, which has good reliability (Cronbach, Citation1951). To avoid ambiguity in responses, the language expressions were adjusted when the pre-questionnaire was distributed. Formal questionnaires were distributed at the end of November 2021. The questionnaires were distributed at the Gongbei Border Gate in Macau, Hengqin Port in Macau, Guanye Street in Macau, outside of major luxury hotels in Macau, and in selected areas with high traffic flow. A total of 437 questionnaires were distributed by simple random sampling, and 405 valid questionnaires were recovered, with an effective recovery rate of 92.67%.

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Descriptive analysis

From the sample data results, the ratio of males (47.1%) and females (52.9%) in this study is relatively balanced. From the aspect of age, it was found that most respondents were between 18–29 years old (60.2%). The educational level of the vast majority of respondents was mostly concentrated between undergraduate degree (65.2%) and master’s degree and above (28.6%). The income level of the vast majority of people was in the middle, between 4051RMB/5001HKD/ 651USD–8000RMB/10000HKD/1300USD (30.4%). The vast majority of respondents were from Mainland China (82.0%), as the questionnaires were distributed in Macau.

As per the responses, most people had five or more hotel stays a year (42.2%), suggesting that with higher income levels, people tend to pursue a better quality of life. The average hotel stay of respondents was 2–3 nights (49.6%). The respondents were mainly students (25.7%) and those working in the service industry (22.0%). The sample demographic information is shown in .

Table 1. Respondents’ demographic characteristics (N = 405)

4.2. Reliability analysis

Cronbach (Citation1951) believed that Cronbach’s alpha coefficient must be greater than 0.7 if the variable is to have good reliability. The reliability of all variables in this study is between 0.915–0.954, which is greater than the recommended value of 0.7.

To further strengthen the reliability of this study, we also tested the combined reliability (CR) of the questionnaire. The recommended value for combined reliability (CR) is above 0.7. The higher the resulting measure, the higher the internal consistency among the variables (Fornell & Larker, Citation1981). All CR values in this study ranged from 0.0.746 to 0.965, indicating that the combined reliability of the questionnaire was very good. To summarize, the Cronbach’s coefficient (α value) and CR value meet the required standard values. The results of the α value and CR value are shown in .

Table 2. Results of confirmatory factor analysis and the reliability and validity of the questionnaire

4.3. Validity analysis

Validity analyses, which measure the authenticity and accuracy of the questionnaire, include convergent and discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcher, Citation1981). If the factor loading coefficient exceeds 0.7 and the average variance extraction ratio (AVE) exceeds 0.5, the research model has good convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Discriminant validity can be measured by comparing the correlation coefficient of the square root of the average of each variable with other latent variables. If the square root of the average variance extraction rate of each variable is greater than the value of the conceptual correlation coefficient, and the value is at least 0.5, the discriminant validity is good.

The results of factor loading is shown in . demonstrates that the load coefficients of all the items of the questionnaire in this study are between 0.833–0.929, which is greater than 0.7. The AVE values are between 0.746–0.846, greater than 0.5. In , the square root of the average difference extraction rate AVE value is higher than the correlation coefficients corresponding to other variables. Therefore, the variables in this research model have high convergent and discriminant validity.

Table 3. Results of measuring the discriminative validity of questionnaires

4.4. Structural model and hypotheses test

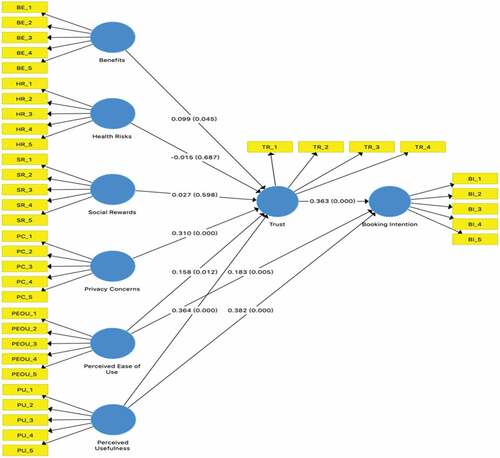

The hypotheses were tested using the Smart PLS 3.0 software to perform path analysis on the theoretical model. According to the verification criteria proposed by Wong (2013), when the T value of the path is greater than 1.96, and the P value is less than 0.05, the path coefficient of the model is significant. The model assumes the path analysis shown in .

Figure 4. Results of hypothesis path analysis for structural model.

To examine the explanatory power and predictive relevance of the variables in the research model, the explanatory variance R2 value was calculated using the PLS algorithm using the blindfolding method. Nagelkerke (Citation1991) proposed that when the value of R2 is between 0 and 1, and the closer it is to 1, the stronger the explanation is, and vice versa. When the Q2 value of the variables is greater than 0, it indicates that the model has predictive relevance (Roldán & Franco, Citation2012). In , the explanatory degree of trust is 75.1%, and the explanatory degree of hotel booking intention is 76.8%. This shows that the research model in this paper has a high degree of model interpretability. In addition, the Q2 value of trust is 0.596, and the Q2 value of hotel booking intention is 0.610, both of which are greater than 0. This indicates that the model in this study has a predictive correlation. The results of R2 value and Q2 value are shown in .

Table 4. Results of measuring R2 and Q2

5. Discussion

5.1. Results

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of consumer-facing IT in safeguarding public health has been crucial, especially when IT was used to replace critical human services. The results of this study confirm that consumers assess their trust in SDT by evaluating the overall benefits and risks of using such technologies. This also affects their booking intention. The hypothesis-testing results of this study show that benefits, privacy concerns, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness have a significant impact on customer trust in SDT, with perceived usefulness being the most significant. However, health risks and social rewards did not have a significant effect on customer trust in social distancing techniques. In terms of customers’ hotel booking intention, customer trust in SDT, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness have a significant impact. Customers’ willingness to book a hotel is directly influenced by their trust in SDT.

5.1.1. Analysis of factors affecting customers’ trust in social distancing technology

Among the factors that affect customer trust in SDT, perceived usefulness has the most significant impact. This shows that a customer’s recognition of technology in a hotel is the first evaluation criteria used to compare with traditional services. Hence, the use of technology for food delivery, service robots etc., provides customers with more convenience and safety. During a pandemic, this is more convenient.

In the context of COVID-19, this study evaluates customer trust in SDT based on a benefit-risk framework and considers benefits and health risks as a group. As the benefits are health-related, and a cure is not yet in place, successfully using SDT to safeguard health is an important task. The results show that when SDT is applied in hotels, people tend to believe that this technology can bring health benefits, reduce the risk of infection in hotels, and protect their health and safety. Health risks have no significant effect on customer trust in social distancing technology. This finding is consistent with recent studies (Shin and Kang, Citation2020). The literature review found that most of the health risks brought about by social distancing technology come from indirect contact. Hotels using SDT have a strict policy of restricting entry and exit for customers, while the facilities on the premises are regularly disinfected. This assures customers that they are less likely to be infected. The service robot mentioned in the literature review and its application reduces direct contact between people, fundamentally reduces the risk of infection, and successfully provides the required service.

Social rewards and privacy concerns were not significant for customers’ trust in social distancing technology. This may be because social rewards are usually achieved through technology to facilitate communication between people to obtain a corresponding emotion, while social distancing technology is deployed in hotels. The purpose is to reduce contact and communication between people. Specifically, there is some emotional value when using social distancing techniques. But it’s more about privacy in use, which may be related to past mistrust of such technologies. In daily life, we often see companies seeking benefits by leaking the personal information of customers. This makes people more concerned about their privacy, and they have more privacy concerns when using social distancing technology in hotels. For example, mobile contactless payment methods may lead to the disclosure of one’s password. There is also the risk that the customer’s personal information will be retained on the computer. This holds a greater risk compared with traditional cash payments. Therefore, we found that the privacy concerns related to the use of SDT are greater than the social rewards provided. This can lead to low customer trust.

5.1.2. Analysis of factors affecting customers’ hotel booking intention

Among the factors that affect customers’ hotel booking intention, perceived usefulness has the most significant impact. The impact of perceived ease of use on hotel booking intention is also very significant, second only to perceived usefulness. This is consistent with the conclusion of Sahli and Legohérel (Citation2016). These results show that when making a hotel reservation, if the customer perceives social distancing technology to be useful, it will stimulate their willingness to book a hotel. Customers will affirm the use of social distance technology and believe that this technology can meet their needs during check-in. This effectively promotes customers’ booking intention. At the same time, the ease of use of social distancing technology can greatly improve the customer’s experience, thereby promoting their booking intention.

Similarly, customer trust in social distancing technology also significantly affects their hotel booking intention. This is consistent with the research results of S. Y. Kim et al. (Citation2017). When customers use social distancing technology in a hotel, and if they have trust, they will think that there is less risk associated with enjoying the hotel’s services or products, and then they will be more willing to book.

5.2. Theoretical contribution and practical significance

5.2.1. Theoretical contribution

First, this study expands the literature on technology trust in the context of COVID-19 by using the principle of reciprocity in SET to explain customer trust in SDT using a benefit-risk calculation approach. Second, this study extends the factors that influence the trust in technology according to SET by discussing the four factors (benefits, health risks, social rewards, privacy concerns) and the combination of TAM. In addition, by studying the benefits and health risks brought by using SDT, this study provides ideas for future research on its health aspects.

5.2.2. Practical advice

This study also offers several practical strategies and recommendations for hotels. First, to increase the consumers’ perceptions of using SDT in hotels, hotels should emphasize the general benefits of such technologies. As guests contemplate visiting a hotel, they should be able to find this information online before booking. This will increase their perception of SDT once they arrive on the property. Considering the current tendency to display signs to illustrate social distancing rules, hotels can provide rich information regarding the benefits of using SDT. This can reinforce customer beliefs that SDT can be used to accomplish hotel tasks while safeguarding their health.

Second, although using SDT will provide more health protection, the virus can still be transmitted through indirect contact. Therefore, hotels should regularly disinfect commonly used devices and machines to minimize the risk of indirect contact. In addition, it is important to understand the experience of customers using social distancing technology and get customer feedback. This can help hotels improve the relevant functions or existing deficiencies and further improve the benefits and convenience of social distancing technology. This will make customers feel safer in the hotel and improve their future booking intention.

Third, this study found that most customers are concerned about privacy issues when using SDT in hotels. Hence, this is an important factor affecting their trust in social distancing technology. Hotels should inform customers on matters that need their attention so that they know the corresponding risks and choose to use or not to use this technology. In addition, customers should be informed about the hotel’s policies to protect their privacy so they feel more trustworthy when using SDT. Ensuring the security of customer information and strengthening the supervision of customer privacy would enable hotels to create a safe technical environment.

The benefits-analysis of the research can also play another role. Strengthening the attributes related to perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, improving the practicability of social distancing technology in hotels, and reducing complex functions can enable customers to easily control related functions and have a good experience. In the future, SDT can be modified through regular customer feedback and evaluation of SDT, making it more functional, simpler, and suitable for customer needs. Allowing customers to experience the benefits and convenience brought by technology during their stay can help increase their future booking intention.

5.3. Limitations and future research directions

This study did not conduct an in-depth analysis of demographic characteristics and other information. Further comparative studies of different groups can be conducted in the future.

Most of the respondents in this study are from mainland China, which leads to certain limitations in the research sample. In the future, it is recommended to broaden the research scope and increase the sample diversity.

Finally, the hotels in this study are all based in Macau. Therefore, the results cannot be applied universally. Future research can include hotels in other areas to make the results more convincing and universal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akbari, M., Rezvani, A., Shahriari, E., Zúñiga, M. A., & Pouladian, H. (2020). Acceptance of 5G technology: Mediation role of trust and concentration. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 57, 101585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2020.101585

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin, 103(3), 411 doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 .

- Bijlsma-Frankema, K., & Woolthuis, R. K. (Eds.). (2005). Trust under pressure: Empirical investigations of trust and trust building in uncertain circumstances. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Blau, P. M. 1964. Exchange and power in social life 1904. John Wi. ley and Sons. Inc.

- Boateng, H., Kosiba, J. P. B., & Okoe, A. F. (2019). Determinants of consumers’ participation in the sharing economy: A social exchange perspective within an emerging economy context. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 718–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0731

- Casaló, L. V., & Romero, J. (2019). Social media promotions and travelers’ value-creating behaviors: The role of perceived support. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2017-0555

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Towards green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Management Decision.

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of business ethics, 114(3), 489–500 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0.

- Cheung, R., & Vogel, D. (2013). Predicting user acceptance of collaborative technologies: An extension of the technology acceptance model for e-learning. Computers & Education, 63, 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.003

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Corritore, C. L., Kracher, B., & Wiedenbeck, S. (2003). On-line trust: concepts, evolving themes, a model. International journal of human-computer studies, 58(6), 737–758 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00041-7.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334 https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900 doi:10.1177/0149206305279602.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology 13 (3) . MIS quarterly. 319–340 doi:10.2307/249008.

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(14), 1111–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x

- Eid, M. I. (2011). Determinants of e-commerce customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 12(1), 78 doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2010.09.008.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39–50 https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Gashami, J. P. G., Chang, Y., Rho, J. J., & Park, M. C. (2016). Privacy concerns and benefits in SaaS adoption by individual users: A trade-off approach. Information Development, 32(4), 837–852 https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666915571428.

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Inexperience and experience with online stores: The importance of TAM and trust. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 50(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2003.817277

- Golder, S.A., Wilkinson, D.M., Huberman, B.A. (2007). Rhythms of Social Interaction: Messaging Within a Massive Online Network. In: Steinfield, C., Pentland, B.T., Ackerman, M., Contractor, N. (eds) Communities and Technologies . Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84628-905-7_3

- Gursoy, D., & Chi, C. G. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: review of the current situations and a research agenda. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(5), 527–529 https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1788231.

- Harridge‐March, S. (2006), ”Can the building of trust overcome consumer perceived risk online?”, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 24 No. 7, pp. 746–761. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500610711897

- Ha, T. M., Shakur, S., & Do, K. H. P. (2020). Linkages among food safety risk perception, trust and information: Evidence from Hanoi consumers. Food Control, 110, 106965 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106965.

- Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1086/222355

- Hoyer, W. D., MacInnis, D. J., & Pieters, R. (2012). Consumer behavior. Cengage Learning.

- Huang, Y. C., Chang, L. L., Yu, C. P., & Chen, J. (2019). Examining an extended technology acceptance model with experience construct on hotel consumers’ adoption of mobile applications. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(8), 957–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1580172

- Israel, K., Zerres, C., & Tscheulin, D. K. (2019). Presenting hotels in virtual reality: Does it influence the booking intention? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-03-2018-0020

- Jeng, C. R. (2019). The role of trust in explaining tourists’ behavioral intention to use e-booking services in Taiwan. Journal of China Tourism Research, 15(4), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2018.1561584

- Jiang, Z., Heng, C. S., & Choi, B. C. (2013). Research note—privacy concerns and privacy-protective behavior in synchronous online social interactions. Information Systems Research, 24(3), 579–595. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1120.0441

- Jiang, Y., & Wen, J. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: A perspective article. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(8), 2563–2573. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0237

- Jones, P., & Comfort, D. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and sustainability in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(10), 3037–3050. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0357

- Kankanhalli, A., Tan, B. C., & Wei, K. K. (2005). Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation 29 (1) . MIS quarterly. 113–143 https://doi.org/10.2307/25148670.

- Kelso, J. K., Milne, G. J., & Kelly, H. (2009). Simulation suggests that rapid activation of social distancing can arrest epidemic development due to a novel strain of influenza. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-117

- Kim, M. K., Chang, Y., Wong, S. F., & Park, M. C. (2015). The effect of perceived risks and switching barriers on the intention to use smartphones among non-adopters in Korea. Information Development, 31(3), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666913513279

- Kim, M. K., Chang, Y., Wong, S. F., & Park, M. C. (2015). The effect of perceived risks and switching barriers on the intention to use smartphones among non-adopters in Korea. Information Development, 31(3), 258–269 https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666913513279.

- Kim, S. Y., Kim, J. U., & Park, S. C. (2017). The effects of perceived value, website trust and hotel trust on online hotel booking intention. Sustainability, 9(12), 2262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122262

- Kim, J., & Lee, H. H. (2008). Consumer product search and purchase behaviour using various retail channels: The role of perceived retail usefulness. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(6), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2008.00689.x

- Kim, H., So, K. K. F., & Wirtz, J. (2022). Service robots: applying social exchange theory to better understand human–robot interactions. Tourism Management, 92, 104537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104537

- Kumar, N. (1996). The power of trust in manufacturer-retailer relationships. Harvard Business Review, 74(6), 92 https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lkcsb_research/5179.

- Ladhari, R., & Michaud, M. (2015). eWOM effects on hotel booking intentions, attitudes, trust, and website perceptions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 46, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.010

- Lawler, E. J., & Thye, S. R. (1999). Bringing emotions into social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.217

- Lee, T. and Jun, J. (2007), ”Contextual perceived value? Investigating the role of contextual marketing for customer relationship management in a mobile commerce context”, Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 798–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637150710834569

- Li, H., Sarathy, R., & Xu, H. (2011). The role of affect and cognition on online consumers’ decision to disclose personal information to unfamiliar online vendors. Decision Support Systems, 51(3), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2011.01.017

- Liu, C., Marchewka, J. T., Lu, J., & Yu, C. S. (2005). Beyond concern—a privacy-trust-behavioral intention model of electronic commerce. Information & Management, 42(2), 289–304 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2004.01.003.

- Liu, M. T., Wang, S., McCartney, G., & Wong, I. A. (2021). Taking a break is for accomplishing a longer journey: Hospitality industry in Macao under the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(4), 1249–1275. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2020-0678

- Metzger, M. J. (2006). Effects of site, vendor, and consumer characteristics on web site trust and disclosure. Communication Research, 33(3), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650206287076

- Milne, G. R., & Gordon, M. E. (1993). Direct mail privacy-efficiency trade-offs within an implied social contract framework. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 12(2), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569101200206

- Molm, L. D. (1997). Coercive power in social exchange. Cambridge University Press.

- Molm, L. D., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1396–1427. https://doi.org/10.1086/210434

- Morosan, C. (2018). Information disclosure to biometric e-gates: The roles of perceived security, benefits, and emotions. Journal of Travel Research, 57(5), 644–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517711256

- Morosan, C., & DeFranco, A. (2019). Using interactive technologies to influence guests’ unplanned dollar spending in hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.04.015

- Morosan, C., & DeFranco, A. (2021). Using social distancing technology in hotels: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(10), 3177–3198. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2020-1403

- Nagelkerke, N. J. D. (1991). A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika, 78(3), 691–692. doi:10.1093/biomet/78.3.691

- Nguyen, C. T., Saputra, Y. M., Van Huynh, N., Nguyen, N. T., Khoa, T. V., Tuan, B. M., Nguyen, D. N., Hoang, D. T., Vu, T. X., Dutkiewicz, E., Chatzinotas, S., & Ottersten, B. (2020). A comprehensive survey of enabling and emerging technologies for social distancing—Part II: Emerging technologies and open issues. IEEE Access, 8, 154209–154236. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3018124

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Developing a community support model for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 964–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.017

- Pappas, N. (2014). Hosting mega events: Londoners’ support of the 2012 olympics. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 21, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2014.02.001

- Park, S. (2020). Multifaceted trust in tourism service robots. Annals of Tourism Research, 81, 102888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102888

- Pavlou, P. A., & Gefen, D. (2004). Building effective online marketplaces with institution-based trust. Information Systems Research, 15(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1040.0015

- Ponnapureddy, S., Priskin, J., Ohnmacht, T., Vinzenz, F., & Wirth, W. (2017). The influence of trust perceptions on German tourists’ intention to book a sustainable hotel: A new approach to analysing marketing information. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 970–988.

- Rahimi, R. (2017). Customer relationship management and organisational culture in hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(5), 1380–1402. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0617

- Rather, R.A. and Hollebeek, L.D. (2019), ”Exploring and validating social identification and social exchange-based drivers of hospitality customer loyalty, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 1432–1451. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0627

- Rehman, Z. U., Baharun, R., & Salleh, N. Z. M. (2020). Antecedents, consequences, and reducers of perceived risk in social media: A systematic literature review and directions for further research. Psychology & Marketing, 37(1), 74–86 https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21281.

- Roldán, J. L., & Sánchez-Franco, M. J. (2012). Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 193–221). IGI global.

- Sahli, A. B., & Legohérel, P. (2016). The tourism web acceptance model: A study of intention to book tourism products online. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715607589

- Sharma, A., Shin, H., Santa-María, M. J., & Nicolau, J. L. (2021). Hotels' COVID-19 innovation and performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103180 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103180.

- Shin, H., & Kang, J. (2020). Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102664 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102664.

- Shin, H., & Perdue, R. R. (2019). Self-Service Technology Research: A bibliometric co-citation visualization analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 80, 101–112 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.01.012.

- Sorrells, M. (2020). Google expedites launch of contactless guest system for hotels in response to COVID.

- Suhartanto, D., Kartikasari, A., Najib, M., & Leo, G. (2021). COVID-19: Pre-purchase trust and health risk impact on M-Commerce experience–Young customers experience on food purchasing. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 34 (3) , 269–288 https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2021.1880514.

- Tu, Y., Neuhofer, B., & Viglia, G. (2018). When co-creation pays: Stimulating engagement to increase revenues. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(4), 2093–2111. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0494

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (1996). A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decision Sciences, 27(3), 451–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1996.tb01822.x

- Wang, H. K., Yen, Y. F., & Tseng, J. F. (2015). Knowledge sharing in knowledge workers: The roles of social exchange theory and the theory of planned behavior. Innovation, 17(4), 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2015.1129283

- Wirtz, J., Patterson, P. G., Kunz, W. H., Gruber, T., Lu, V. N., Paluch, S., & Martins, A. (2018). Brave new world: Service robots in the frontline. Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 907–931. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-04-2018-0119

- Yang, M. and Han, C. (2021), ”Revealing industry challenge and business response to Covid-19: a text mining approach”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 1230–1248. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2020-0920

- Yudiarti, R. F. E., & Puspaningrum, A. (2018). The role of trust as A mediation between the effect of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use to interest to buy E-book. Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen, 16(3), 494–502. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jam.2018.016.03.14

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

- Zemke, D. M. V., Neal, J., Shoemaker, S., & Kirsch, K. (2015). Hotel cleanliness: Will guests pay for enhanced disinfection? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(4), 690–710. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2014-0020

- Zhang, C., Dong, X., Zhang, S., & Guan, J. (2021). The application of social exchange theory in tourism research: A critical thinking. In The 2021 12th international conference on E-business, management and economics, 683–687.

- Zhang, J., Xie, C., Wang, J., Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2020). Responding to a major global crisis: The effects of hotel safety leadership on employee safety behavior during COVID-19. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(11), 3365–3389. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0335

- Zhao, Q., Chen, C. D., Wang, J. L., & Chen, P. C. (2017). Determinants of backers’ funding intention in crowdfunding: Social exchange theory and regulatory focus. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.06.006