Abstract

Infrastructure poverty and poor service delivery that characterise rural spaces are more evident in developing countries. In Nigeria, tackling the exclusionary practices in rural service delivery is dependent on the responsiveness of numerous stakeholders. In this study, planners and political office holders are identified to be critical to rural service delivery. Based on ten interviews, two FGD, and geospatial data, collected from eleven rural communities in Oyo State, Nigeria, the aim of the study is to examine the governance of rural service delivery in Oyo State, Nigeria. Findings show that households children traveled more than one hour to school. However, distance disparity existed between peri-urban villages closer to capital city (1.8 km), villages in secondary or lesser towns (1.2 km) and rural villages (6.9 km). The study concluded that planning and local politics in sampled communities are diametrically opposed on the public interest and common good of rural dwellers. Recommendations were made for planning to be more rural-oriented, and inclusive of the spatially excluded rural residents. This is because the need for a more participatory and responsive rural governance towards achieving inclusion in service delivery will promote national rather than urban development.

1. Introduction

The concepts of rural villagisation, urban estates in rural communities, and sub-urbanization continue to provoke doubt about the total disappearance of rurality, or rural areas. Despite the movement towards the urban framed agenda and movement, Grgić et al. (Citation2010) have alluded that rural people will remain a key component of the spatial fabric of the national space. This argument is further buttressed in the population (Mellor, Citation2014), the recent renaissance of rural agenda and development (Rauch, Citation2014), the move toward ending hunger, poverty, and sustainable communities as embedded in sustainable development goals (Agboeze & Nwankwo, Citation2018; Bernstein et al., Citation2019).

Despite rural population concentration, poverty from weak human capacity and service delivery have a rural face. The view is that there exists a relationship between service delivery and livelihood conditions. This, according to Popoola et al. (Citation2021), was due to segregation in service delivery availability, access, and affordability across various spaces. In Nigeria, rural exclusion and segregation can be attributed to weak capacity and political interference along the State and Local government in effective and responsive public good provision process (Ibok, Citation2014). Okojie (Citation2009) posited that governance decentralization evident in Federal, State, and Local government structures have not positively improve rural service delivery. The author mentioned that weak political will for autonomy in the developmental process continues to limit rural development. That is why it has been averred that institutional, political, social, and economic variable are the limiting factors to rural service delivery (Lawal, Citation2014; Mangai, Citation2016; Popoola, Citation2022a). The institutional dimension to improved service delivery recognises the need for progressive cooperation among stakeholders. This study, therefore, argue that planners, and political office holders are key to rural infrastructure location, and service delivery (Popoola & Magidimisha, Citation2019b, Citation2020b).

The notion is that, this problem of service delivery and infrastructure provision calls for a responsive, effective, and collective positive action of various stakeholders. This, therefore, points to the relevance of collaborative governance toward achieving the public goal and good. This is because limited progressive collaboration in decision-making may limit service delivery (Woldesenbet, Citation2020). In rural Nigeria, Ama et al. (Citation2020) alluded to the effect of stakeholders’ collaboration in improving quality and equal basic education. To this end, Acey (Citation2016) posited that local governance is critical to the solving grassroots wicked problems which undermine her sustainability. Studies (Popoola et al., Citation2022; Popoola et al., Citation2021; Popoola & Hangwelani, Citation2019a; Popoola & Magidimisha, Citation2020a) listed that weak stakeholder collaboration, development corruption, political interference, developmental overlap, clash in departmental and agency roles, limited operational autonomy by government departments, corruption and lack of transparency are limitation to developmental governance.

This study is based on the gap in knowledge about the role of local stakeholders (planners and political office holders) in rural service delivery. Studies (Bye et al., Citation2021; Islam, Citation2021; Leone, Citation2013; Popoola & Magidimisha, Citation2020b) have recognised the gap in rural planning and grassroot politics literature in ensuring rural sustainability. Islam (Citation2021) mentioned that empowered local governance, rural political security, effective, and inclusive participation in development planning through a multi-stakeholder approach are key to collective rural development. Why this study authors recognised the relevance of rural political representative through elections in decision-making (as in Bye et al., Citation2021), the gap in literature remains the responsiveness of the democratically voted rural political representative in promoting service delivery. Like McKay et al. (Citation2021), this study assumes that poor service delivery in rural areas is associated with political representation and planning.

Therefore, using experience from Nigeria, the authors questioned the interaction between planning and politics in rural areas. This is because political actors as a part of rural governance must exhibit fairness, justice, and responsiveness to achieve inclusive growth. In Nigeria, the roles of the democratically elected political office holders in Federal, State, and Local tiers of government (Abe and Omotoso, Citation2021; Abdullahi & Ahmad, Citation2018) cannot be over-emphasised. This is because local political actors allow for grassroots social inclusion toward public good and interest (Adesopo, Citation2011). However, in a situation where the representation is biased, the share of public good (i.e., public services) remains devoid of equity and public interest. Such that the location and allocation of services may be political rather than a reflection of public interest.

In this study, political office holders as key part of governance and decision-making entities and planners, as actors in shaping the rural environment were examined to establish their roles in achieving sustainability for the rural people. Performance as a principle of good governance was identified as key to understanding governance of service delivery. Thus, governance performance according to United Nations Development Programme (Citation1997, pp. 11–64) includes responsiveness (this connotes a system, institutions/stakeholders and processes which are dedicated to meeting the needs of all) and effectiveness and efficiency (this entails the processes and institutions/stakeholders involved in meeting the needs of the people to ensure that resources are properly managed). Therefore, the study recognises that this can further be understood by examining the governance stakeholders in rural service delivery in Oyo State, Nigeria. To achieve this, the following objectives were forwarded:

To assess the service delivery experience of rural residents in the sampled local communities;

Examine the role of politicians and planning in ensuring improved service delivery; and

To carry out the geospatial mapping of infrastructure accessibility to rural communities using the planning standards as a guide for infrastructure allocation and location.

2. Theorising rural inclusion through planning and governance

Collective interaction and collaboration among relevant stakeholders are critical to rural developmental inclusion. To this regard, the authors recognise that the rational comprehensive theory and the concept of governance offer a gateway to understanding service delivery. The rational comprehensive theory as a social planning theory (Friedmann, Citation1987) places emphasis on rationality in the advent of numerous institutional and political demands and pressures (Grant, Citation1985). The plethora of institutional pressures amongst actors toward public good and interest also justifies the application of the concept of governance. In the same sense, studies (Altshuler, Citation1965; Campbell & Marshall, Citation2002; Faludi, Citation2013; Innes, Citation1996) have iterated on the place of public interest through consensus building and communicative approach as key to comprehensive planning. Most especially the argument of the need for political discussion and decision-making towards arriving at a logical plan. A preposition that Faludi (Citation2013) identified to be accommodating public interest. Thus, the authors argue that the notion of governance focuses on a system regulating the relationships between the government and societal stakeholders. Such that the legal interests of various groups are accommodated. In this regard, governance is related to public sector improvement (Grindle (Citation2004) through the collective and efficient legal management of the political, social, and economic endowments of such nation (Asian Development Bank, Citation1995; United Nations Development Programme, Citation1997; World Bank, Citation1992). It then can be seen as the process whereby policies on public life and allocation of resources are enacted for the public interest (physical, economic, and social development).

Planning for the public interest is common knowledge. Studies by Sandercock (Citation1998) and Allmendinger and Thomas (Citation1998) alluded that comprehensive planning highlights the need for logical decision-making. This perceived to be birthed from the good governance of service delivery through responsive political representation and effective planning. The planning effectiveness and responsiveness to decision-making according to Faludi (Citation1983) are based on relative mental skill of planners. This skill is conceptualized within the planning standards adopted in the location and allocation of infrastructure in Oyo State (Vagale, Citation2000). That was why Marios (Citation1979) mentioned that comprehensive planning implies the process of satisfying the needs (through coordinated and responsive planning) of all groups in a heterogeneous democratic society in such a way that a common good called the public interest is reached. The public interest and good can therefore be said to be the underlying driver of the principles of governance. This is because governance decisions through social planning and decentralised management and local government-citizen interaction are focused on public interest. Owing to this, this study examined the roles played by these actors in rural infrastructure inclusion and service delivery.

Following Buhr (Citation2003), the conceptualization of infrastructure is done along the material capacity understanding. As in Jochimsen (Citation1966) and Popoola (Citation2022b), the view is that material infrastructure is an enumeration of essentially public facilities characterized by specific attributes. The Investopedia Team (Citation2022) explained that infrastructure is the basic facilities and system serving a country, region, or community. Examples include transportation systems (road network), communication networks, sewage (drainages), water (wells, boreholes), and school systems (primary, secondary or tertiary). Frischmann (Citation2017) pointed out that the choice of what to use as an infrastructure provided within a particular location is dependent on the user but nonetheless, its provision cannot be undermined. This is because the human capacity to maximise the potentials of a resource varies across space, as the value or priority placed on a social facility, or a service delivered is often subjected to the narratives of the provider (public/government or private stakeholders) and consumer (rural dwellers). In this study, focus is on road, educational, water, health, and power infrastructure. Thus, facility and infrastructure are used interchangeably.

3. Understanding the governance and planning system in Oyo State, Nigeria

3.1. The governance system in Nigeria

The governance system in Nigeria is embedded in the three tiers and three arms of government. The three tiers are the Federal, States and Local government Areas (LGA). There are, however, political wards in each LGA. The States, LGAs, and Wards in the country are numbered 36 plus the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, 774 and 9572, respectively. Distributed along six geopolitical zones (South-East, South-South, South-West, North-Central, North-East, and North-West), with each zone comprising five to seven states. At each tier of government, there are three arms of government including executive, legislature, and judiciary. The executive arms include the President (with his ministers) at the federal level, the Governors (with their Commissioners) at the state level, and the Chairmen (with their Advisory Counsellors) at the LGA level. The legislative arms at these levels include Senators/Members House of Representatives, Members House of Assemblies, and Councilors, respectively. The heads of the judicial arm are Chief Justice of the Federation at the federal level, and Chief Judges at the state level, who also oversee judicial issues at the LGA level of their various states. All heads of the executive arms and the legislators are democratically elected positions, different from the heads of the judicial arms who emerge by executive appointment followed by legislative approval. The key political stakeholders considered in this study are the LGA Chairmen, members Houses of Representative, Senators, the Governor, and Federal Ministers in various ministries as designate of the Office of the Presidency.

Popoola and Magidimisha (Citation2020a) have extensively documented the roles of the three (the Federal, State and LGA) in Nigeria and their roles and constitutional mandate in service delivery. It was highlighted that the Federal sphere at the peak of service delivery authority is supported by both the State and LGA authorities. The Federal government of Nigeria is focused on the national delivery of the public good (infrastructure in this context), the State and LGAs are perceived as the main public service provider. Bello-Schunemann and Porter (Citation2017) and Alobo (Citation2014) reported that why the Federal government is tasked with the nationwide upgrade of infrastructure in Nigeria, the LGA remains grassroot tier of government that attends to rural people primary needs.

Although, studies (Khemani, Citation2001; Popoola & Magidimisha, Citation2020a) have emphasised the need for improved coordination in service delivery. The argument was along the need for a more coordinated inter-governmental physical and fiscal relationship that will promote and achieve an inclusive delivery of basic public services. Omar (Citation2009) listed that the three impediments to effective service delivery in Nigeria includes the lack of transparency and accountability in governance: the inadequacy of skilled and professional manpower in local government and the tenuous relationship between urban local governments and residents. Attributed to the incapacitation of the State and LGA is the federalism form of government practiced in the country (Popoola & Magidimisha, Citation2020a).

Majekodunmi (Citation2012, p. 90) mentioned that the local government is essentially created as a viable political and administrative organ for the transformation of all communities and for delivery of essential services to the citizens. It was recognised that the law mandates the LGA to provide the following public goods and services: establishment and maintenance of roads within the towns of the district, including sidewalks, streetlights, and street drainage system, construction of water reservoirs in towns and villages, construction and management of primary schools. Other essential functions include the construction and management of centres for the care of the mother and the child, physical planning of the settlements of the districts and registration of the immovable property, solid waste collection and disposal, food and livestock markets, slaughterhouses, management of self-help projects, registration and maintenance of civil register, and issuing business licenses, among others. Popoola and Magidimisha (Citation2020a) mentioned that the Federal government is mandated to perform the function of infrastructure regulatory, guideline development, masterplan development, funding, exploration of natural resources and technical partnership in service delivery.

Oyo State, a state in Southwestern geopolitical region of Nigeria is made up of 33 LGA, and 337 political wards. The State is made up of three senatorial districts (Oyo South, Oyo Central and Oyo North). Due to lack of administrative map according to ward, households delineated along the senatorial districts and LGAs forms the unit of analysis. The local government areas comprise wards, Federal Constituencies and Senatorial Districts. The rural areas consist of several settlements which are classified as Wards for administrative purposes. The sampling of the settlements across the LGAs and senatorial district is discussed in the study methodology.

3.2. Local planning arrangement in Oyo State, Nigeria

Local planning management and administration in Nigeria are done by the Bureau of Physical Planning and Development Control. In Oyo State, the Bureau of Physical Planning and Development Control, which was created from the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey in April, 2017, administers planning in the State. With the headquarters at the State secretariat in the capital city, Ibadan, the zonal offices of the Bureau of Physical Planning and Development Control manages the local planning activities in LGAs. The offices are present across sixty-eight (68) town planning offices located in the 33 LGAs and 35 Local Council Development Areas (LCDA) in Oyo State. The execution of the planning mandate across the LGAs is based on the planning standard (see, Vagale, Citation2000).

The planning standard is one of the legal tools used to guide the ordering of space and the arrangement of infrastructures. The physical planning standard has been adopted within the built environment and aims to maintain effective planning regulation through the prevention of contraventions and haphazard development. The process of maintaining an effective spatial arrangement by deploying the planning standard tool is known as development control. Planning regulations coded as standards are tools and yardsticks to regulate the use of infrastructure which have a level of flexibility but are mandatory (Agbola, Citation2001). Olujimi (Citation2008, Citation2009) classified planning standards into locational and space. Space standards are the minimal or the extent of land needs for a particular infrastructure. Olujimi explained that locational standards focus on the concept of range and threshold as identified by this study. For every physical infrastructure located in space, there are expected distance coverages for a user, giving an example of a ten-minute walk from home to a primary school. This study focus was not on the planning standard as it relates to development, but rather on the place utilizing planning standards as a yardstick to dictate infrastructure provision. The planning standard by Vagale (Citation2000) served as instrument to measure range (distance to infrastructure) in this study.

4. Study materials and methods

The study was evidence based, with data collected through interviews and focus group discussion (FGD) with purposively sampled rural stakeholders in selected villages of Oyo State, Nigeria. The villages and communities, having aligned to some rural criteria (population, nature of activity, outlook, geographical isolation, cultural configuration, and economic variables as defined in poverty and income) following reconnaissance survey, perception of the State Ministry of Agriculture, and expert advice, were purposively sampled for this study. The study provided a thematic analysis from qualitative data responses to the questions. This was based on a local ethnographic analysis and case study evidence. According to Sarantakos (Citation2005), ethnographic research is used when critical and descriptive analysis is involved. This is relevant as the research was focused on exploring people’s understanding, conditions, survival and experiences of their rural world with a focus on governance, planning and infrastructure.

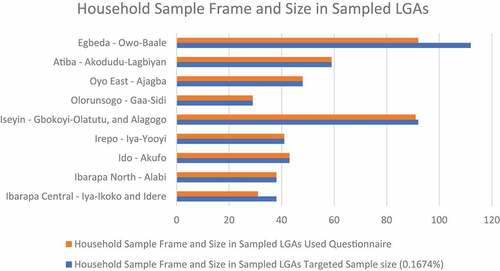

The study units of analysis were households, villages, and Local Government Areas within the geographically mapped Senatorial Districts of Nigeria. The study made use of a mixed methods approach with both qualitative and quantitative data obtained from a questionnaire, field observations, in-depth interviews, and FGD as tools of data collection. The household sample size was calculated at 500 households, but after data cleansing, only 472 (Figure —representing 94.4% response rate) questionnaire responses were arrived at for the analysis (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017). Household questionnaire responder is the household head, mother of the house or most matured household members.

5. Descriptive and content analysis

To understand the liveability, affordability and accessibility experience of the sampled respondents, descriptive analysis through frequency tables and cross-tabs allowed for deductive reasoning in the study. The thematic content analysis of transcribed interviews provided empirical justification for the frequency analysis. The authors recognized that distance is key to explaining access and affordability. Thus, the distance travel to the nearest facility by the sampled households were captured in kilometer. The distance captured was based on the range of facility as mentioned in Vagale (Citation2000). The cost of transportation to the facility and cost of utilization of selected facilities formed the basis for explaining affordability among sampled households. The cost of transport was the amount paid to a transporter (mostly commercial motorcycle riders), while the cost of utilization was represented by the levy paid by each student at school, or the consultation fee at nearest health facility. The effect of high cost of transportation and utilization among the sampled households in the communities have been presented in Popoola et al. (Citation2022).

Interview transcripts of the ten interviewees from both public (three planners, and three government officials) and private (two businessmen and two rural residents) stakeholders and FGD conducted in Iya-Ikoko and Akodudu, village provided a narrative to responsiveness of political actors in infrastructure provision in the sampled communities. The relevance of interview to the study is that it helps to decode the actions, and experiences of residents in the sampled rural communities (Zhang & Wildemuth, Citation2009).

In Iya-Ikoko village of Ibarapa Central LGA, eight rural stakeholders were part of the discussants while in Akodudu village in Iseyin LGA, seven persons formed the FGD. The discussant comprises of the village head (called baale or agba-ile) of the sampled settlement, some notable dwellers, and officials of the government in the area. The question outline was prepared to ensure that the relevant areas of interested were fully explored and it consisted of rural perception and understanding of rurality, infrastructure condition, rural needs and planning, and community participation and governance

6. Geospatial analysis

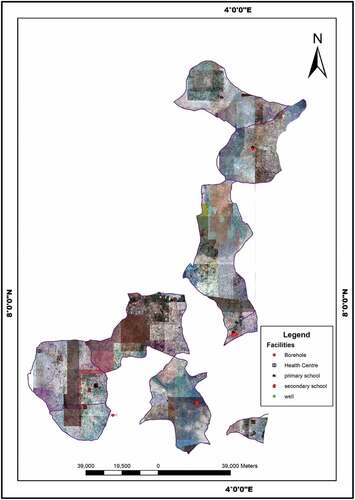

Geospatial mapping was done through Open Data Kit (ODK) and ArcGIS. The efficacy of the planning tool using Vagale (Citation2000) (this is guiding instrument for facility allocation and location) planning standards were tested through geospatial analysis. This was done by mapping the sampled nearest facility to the communities and then compared with the recommended planning standard. The infrastructure range was captured through the identification of imaginary community centre vis-à-vis the nearest facility utilized by the sampled community. The infrastructure buffer circle represented the expected farthest distance (as stated in planning standard—Vagale, Citation2000) that a community (as comprising households) should not travel beyond to access the sampled facility.

7. Results and discussion

7.1. Infrastructure condition in rural areas and struggle for the city

The study authors recognised that infrastructure is imperative to improving livelihood. Rural dwellers have over the years perceived the lack or inadequate infrastructure as a dimension to exclusion. Iterating this, an interviewee alluded that poverty experience abound among rural dwellers due to limited infrastructure availability and accessibility. A public official stated that “ … there is poverty. It is because of no power supply and internet that make the rural dwellers migrate. They (rural dwellers) are being referred to as being poor in terms of rural facilities, not in terms of money. Rural people have businesses and make profit. However, there exists limited access to portable water owing to poor roads condition, so they spend more to access the city … ” The preposition for the right to the city as a reflection for inclusiveness in city agenda, is due to their excluded infrastructure experience. This “rural infrastructure-poverty” experience is explained as where there is lack of infrastructure in villages, results in increase infrastructure cost burden to access the town or city services. Thus, resulting into increased poverty footprint in such areas.

An interviewee (Rural Crop Management Project Manager, Oyo State Office) argued that the absence of infrastructure in rural areas has considerably affected their livelihood opportunities. This was reported to have resulted from decline in income due to the increasing access and travel costs to the nearest facilities. This explains that infrastructure exclusion remains a barrier to rural inclusion. Participants’ observation through reconnaissance survey and interview revealed that it takes between forty minutes and two hours to travel on a motorcycle to the nearest public school at sampled villages in Olorunsogo and Irepo LGA. An experience that often exceeds the 20-to-40-minute walk distance expected to the nearest primary school (see, Vagale, Citation2000). Evidence points that factor such as village isolation, poor road condition and lack of infrastructure are drivers of rural exclusion which evidently influence liveability.

7.2. Rural political “Actioning”: questioning the responsiveness of local representative in service delivery

In rural areas, reshaping for inclusion demands for a multi-sectoral stakeholder involvement. Politicians (depicted as rural democratically elected or politically appointed representatives) are expected to play a key part in the responsive shaping of rural areas. The decisions of these actors are expected to be in public interest and less of political show. In this study and setting, political actioning is termed as “behaviour (mostly devoid of public interest, irresponsive and irrational) that rural politician and politics display in their setting”. In explaining this, the authors exemplified the state of rural education infrastructure to explain political failures in achieving improved rural facility inclusion.

Evidence as presented in , along with interviews with stakeholders and observation, revealed that there was a display of political wits among the local government infrastructure providers (councillors, and chairmen) and various stakeholders of infrastructure (house of representative and department of works officials). It was observed that in the sampled villages, there existed numerous abandoned infrastructure projects (). Interviews revealed that this was due to poor infrastructure maintenance (a situation in which a democratically elected officer refused to maintain a dilapidating school facility constructed by his or her predecessor, rather preferred to erect a new one). This situation reflects weak collaborative and progressive governance in the areas. It has been established that the “politicisation” of educational facility provision in rural areas results in availability and accessibility challenge. As scarce rural resources are not effectively utilised for common good. This is more evident when educational infrastructure provision between urban, sub-urban and rural are compared.

Despite the role of local government and other political stakeholders in promoting the common interest of the populace (Agbakoba & Ogbonna, Citation2004), empirical evidence from this study shows that the politics rather than the collective governance of local area shapes the place of service delivery. This is supported by 59.1% and 64.8% of the sampled households that perceive political affiliation between the State, LGA and communities rather than communal needs often influence infrastructure development (Table ). For example, Adebayo (Citation2018) reported that the dearth of infrastructure in Apete-Akufo communities of Ido LGA was because the rural communities did not collectively vote for the ruling political party (All Progressive Congress [APC]). Adebayo (Citation2018) listed that executive bureaucracy and politicking among the tiers of government, political neglect, and “voting” revenge, accounted for the poor service delivery conditions.

Table 1. Mental knowledge of rural households of the political arrangement

Secondary evidence in form of a press brief from the Office of Oyo State Governor recognised the with the same political party (APC) as the President of the country, the State would benefit more than States that are not within the same political party (OYSG, Citation2019). This statement indicates the politicking of infrastructure location and provision, and a psycho-perception of that political alignment among party structures across the tiers of government plays a great role in service access. Thus, further emphasizing the need for local government independence as reported by 82.4% of the sampled households (Table ).

An interviewee reported that the politics of the environment has now resulted in what the researcher terms the “Few Excluded among the Commonly Excluded”. This study argues that while rural areas are generally the most excluded in the country, the politicking of rural infrastructure has further excluded and neglected some fewer rural communities in facility provision.

Although the relevance of politics and political representation can be said to be somewhat influential on facility location, the FGD identified, in some cases that the political representative does not usually translate into improved service delivery (see FGD commentary in Table ). It was further observed that communities with a history of political representative have quite a higher share of facility provision. Examples in this study include the boreholes and road paving in some villages (Figures ). Field observation backed by pictures (Figures ) shows that there existed a scatter of the effect of federal legislative political representative facility projects within the LGA. Some of which were in poor condition.

Table 2. Narrative report of rural dwellers of political actors

Why the federal representative infrastructure project was quite represented across some of the sampled villages in the LGA. Field observation and interview revealed that the project output of the legislative arm of the State government (House of Assembly members) were not available or reported by the rural dwellers to exist. During a key informant interview with a government official at Atiba LGA, he was asked of his view about the representation of the rural community in the house of assembly and what it translates into infrastructure provision. He responded thus:

“ … I can confidently say they are not performing based on infrastructure or any other thing. If government wants them to be effective there should be a monitoring team that will put a check on their activities and when the money is released to them giving feed back to the government … ” Official of Department of Works, Atiba LGA

This ineffectiveness of the democratically elected representatives in delivering the output of governance in infrastructure was one of the reasons for reported perception in Table that there were more infrastructure investments during the military regime than the present democratic dispensation. Based on the responses, 53.2% were of the view that there were more infrastructure investments in the military dispensation as against 36.9% that disagreed and the remaining 10% that didn’t respond to the question. As reported during the interview, the dwellers and stakeholders interviewed responded that corruptions, lack of rigid infrastructure development plans, politics of nepotism, bureaucratic overhauling and manipulation by the higher tier of government to the LGA, weak and limited capital investments, poor political will to invest in rural areas and excessive focus on oil-driven allocation from the federal government were some of the factors that triggered the perception of infrastructure investments during military era.

The infrastructure footprint of the Directorate of Food, Roads, and Rural Infrastructures (DFFRRI) program is still appreciable, with some of the roads connecting villages dating back to the military era in the LGAs. A dweller at Iya-Yooyi village of Irepo LGA lamented that history shows that the civilian-democratic regime has used the rural electorate, with little or nothing to show in infrastructural and livelihood enhancement initiatives and programs. She said if permitted, in her own view, she would prefer the military era, as there was evidence of infrastructure development despite the forceful nature and lack of participation of the governing regime. Supporting her perception, an interviewee who resides in Ajagba village, Oyo East LGA said: “ … Despite some infrastructure put in place during the military the only problem then was lack of freedom and democracy … ”

This infrastructure neglect is compounded by the state of failed “rural governance and political representation” in Oyo State (Tables ). The interviews with the respondents established that many of the local political representatives once elected relocate to the urban areas, thus, resulting into failed participation and representation of the local voters. This is a divergence from the views of Agu et al. (Citation2013) who iterated on voters’ apathy and participation. However, the relevance and public interest-driven representation remain a silent topic to rural political participation. As Agu et al. (Citation2013), we ask if rural political representation in this area makes a difference for common good and rural interest. When related to infrastructure delivery, Ọmọbọwale and Olutayọ (Citation2010) has discussed this in the rural political clientelism. A situation in which political representation does not translate to rural interest. This situation when completely played out (after the election) despite their (rural people and voters) massive voting results into unimpactful representation in public good (service aelismnd infrastructure) but rather in numbers (a village representative). This may continually put equity and inclusion in infrastructure to shock and rural neglect continuum.

7.3. The affordability and accessibility experience in rural Area

Examining public educational and health facilities affordability (Table ), preference, due to access to all social group was given to public primary and secondary educational facility. To establish the affordability, the study took into consideration a yardstick of an average of ₦600 (2USD) spent on accessing the nearest facility (electricity) in the study areas (see, Popoola & Hangwelani, Citation2019a). The study of Popoola et al. (Citation2022) has justified the use of expenditure rather than income as an explanation to livelihood experience in rural studies.

Table 3. Affordability index of household on education and health facility

Analysis shows that there was higher household’s representation of reported cases of spending above ₦1000 for using health and education facilities in villages within urban and township corridors (Egbeda, Ibarapa North, Ido and Irepo LGAs). The study argues that city-peri-urban interaction effect accounted for the high cost in peri-urban corridors, while geospatial distance and lack of facilities accounted for the hike in cost in interior rural LGAs (as in public schools in rural LGA of Ibarapa central). That, therefore, influences affordability experience. This is evident as between 11–18% of the household respondent perceived educational and health facility to be unaffordable (Table ). This attributed service charge of between ₦501 and ₦1000 (18.0%), or above ₦1000 (47.3%) claimed to be paid by respondents.

Table shows about thirteen households children traveled more than one hour to school. The travel time following observation and interview was because walking was the common modal choice among rural children. Few (45.6%) made use of fared public transport, such as motorcycle or buses. The daily transport cost could range from ₦250 (16.3%), ₦251 and ₦500 (3.3%), to above ₦500 (4.7%). Despite this household burden expenses, it was revealed that 14% more (than education sample cost) household paid above ₦500 to make use of health facility (Table ). This explains why Popoola et al. (Citation2022) reported that educational trip accounted for over 34 per cent of the household income.

Table 4. Accessibility to education and health facility across the study area

7.4. Rural planning dilemma

Over the year, planning has been observed to focus on the urban space. The study interview revealed that rural planning remains limited in rural areas. This is attributed to the gap in communication and participation in planning by rural resident. An interview session revealed that the lack of rural planning can be traced to poor political will to support planning ideas. Narrating his views and experiences, a planner in Ibarapa North LGA reported there have been various attempts at preparing a masterplan for this LGA without any positive outcome or support or encouragement from the local government. He went further and noted that:

“ … Many rural LGAs don’t have masterplan. However, one major planning challenge is that the rural people see planning as an instrument of the government (The Political class). Therefore, termed the government planning, not the peoples planning. The need to regulate ancestral or indigenous land still remains unclear to them … ”

The rural perception of planning as “government planning” rather than “planning for all” is one of the limitations to efficient and responsive service delivery in rural areas. The perception of planning as a modern instrument of the government (local, state, and federal), as against a professional practice that incorporates the people, has limited the acceptance of rural planning and appreciation of the duty of rural planners in the study area. These evidence-based findings are further collapsed in the limited applicability of the planning standard as proposed by Vagale (Citation2000). The view is that the layer of culture, politics and traditional leadership that is dominant in rural communities limits the “generic” planning tool and standard applicability. This is because, in most instances, rural setting demands are at variance to conventional planning (as urban suggested in the planning standard).

For instance, the rural communal experience and collective socialisation as embedded in the people culture might serve as a threat to unbiased functioning of rural planners. A planner stated that “ … our efforts are still subjected to a lot of stress owing to the culture of the people. Rural people rarely have cognizance for the Bureau of Physical Planning and Development Control. Many build houses on the road and when you now roll out the development control mechanism for either demolition or contravention, because they know your family owing to familiarity, they go to your father to complain … . He went further and buttressed that sometimes last year, someone was building a commercial centre at a wrong location without planning approval, we (local planning unit) gave two prior notices before demolition notice, after which the unit engaged in ‘token demolition’, the owners came to my home with cutlass to harass me and my family … ” These are some of the existing planning peculiarities in the rural Oyo State. This failed attempt of planning is embedded in both the framing of the unit (as physical planning and urban development) and the less adaptation of rural identity to planning. This, Sirayi et al. (Citation2021) in their book argued that local culture has been downplayed in the explained urban-rural linkages, sustainability, revitalization and grassroot development plans and planning. The main threat may be adoption of urban theories, principles, and standards in a rural setting. Thus, a need for planning to be localized and adaptive of grassroot experiences cannot be ignored.

7.5. The infrastructure dilemma: planning, accessibility and affordability

This study sees the accessibility and affordability of infrastructure (educational and health facility) based on household perception of mileage (km) and time (minutes) distance travel and cost of transport and use in Naira, respectively. Taking into consideration LGA size and the expected planning criteria, Vagale (Citation2000) identified types of health and educational facilities that was located in rural areas (see, Table ).

Table 5. Set-out planning standards for the location of health and educational facility

The notion of the study authors is that since rural areas are spatially disperse and characterized by low population, managing access to and affordability for service in the context of good governance may be somewhat impossible if planning standard in local places are not carefully applied. The preposition is that with limited syncing between rural facility needs and location (in context of planning standard), the local dwellers remain at the negative receiving end of this facility planning and allocation dilemma. This argument as proposed in this study provokes the thinking along the applicability and acceptability of the range (radius of catchment) criteria as a defining factor for the provision of facilities (Table ) in rural areas. The question is based on availability of facility, mobility choices, distance of nearest facility and the village characteristics. For example, travel time increases based on mobility choices (as most pupils travel via foot or motorcycle) to the school. However, participant observation and reconnaissance survey revealed that rural households maximize their knowledge of the rural terrain in accessing rural infrastructure. It was found that while the travel time across the conventional circulation infrastructure may be longer, villagers walk via “short-cuts” (mobility routes created along unconventional bush and foot paths to connect communities) in easing transport cost and achieving affordability and access to facilities.

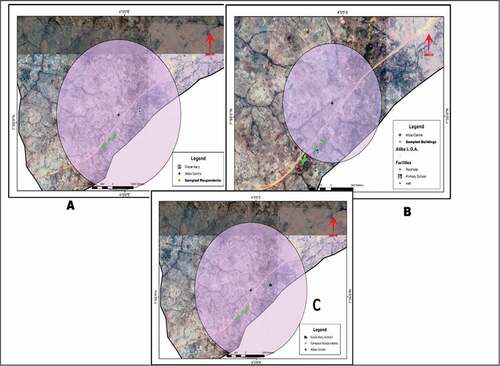

A geospatial experience based on Vagale (Citation2000), and imaginary village centre (usually communal meeting point), was used to examine health and education accessibility (facility radius). The focus on health and education facility was due to the point feature of this facility and the limited likelihood of its mobility for the present locations. Post-field mapping of health facility on ArcGIS using catchment radius of 4.8 km revealed that all sampled households were within facility range (). The post-field mapping of the health facility on ArcGIS used a catchment radius of 4.8 km, as the accessibility distance (with less consideration of the functionality, village hierarchy and outlook of the health infrastructure). It was revealed that the “bigger” villages fall within the travel radius of 4.8 km for the establishment of a health facility.

However, the researchers contend that radius of (range) accessibility, in this case, might not be a true reflection of the accessibility experiences of the “unmapped lesser villages” that are dependents on the big villages for livelihood and infrastructure access. Studies (Cader et al., Citation2018; Correa & Pavez, Citation2016; Mawani, Citation2019) have reported that many “unmapped isolated villages” and “small homesteads” remain at disadvantage to service accessibility. This was iterated in an interview with a health official in one of the sample village. She reported that strategic and collective decision among homesteads and villages for ease of access among smaller homesteads that surround the village led to the location of health facility in the village. In achieving access by health officials and communities, another health dispensary in a different location (Ijawaya—) was located on the highway that links Oyo and Ogbomosho town. Following participant observation, mapping and interview, other sampled rural localities without health facility in their immediate environment travel between 25 to 60 minutes to the nearest facility.

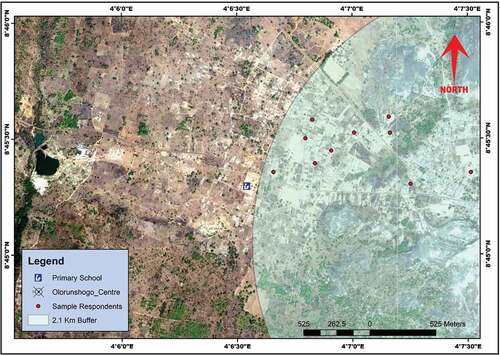

The same selected exclusion among village or households as shown in () where the Fulani herders’ migrant settlement (Gaa-sidi village) is not within the 2.1 km range buffer circle to the nearest primary school (). The secondary school catchment radius analysis across the villages sampled revealed that from the sampled villages, only four villages (Owo-Baale village in Egbeda LGA, Ajagba in Oyo-East LGA, Akodudu village in Atiba LGA and Akufo village in Ido LGA) had the standard access radius to secondary school facility. All these villages can be classified as rural scape within an “urban setting” as the villages were relatively located within the close proximity of city and towns such as Ibadan (capital city), Oyo, Ogbomoso, and Kisihi towns. The other sampled villages (Alabi, Iya-Yooyi, Gaa-Sidi, Alagogo, Olatutu-Gbokoyi and Idere villages) did not have access to secondary school within the mapped catchment radius (see for example, ).

The study geospatially examined the few excluded among the commonly excluded rural settlement (Popoola et al., Citation2022) by mapping the average rural and peri-urban villages distance from home to primary school. Evidence shows that average distance across the sampled settlements to the primary school was 2 km. However, distance disparity existed between peri-urban villages closer to capital city (1.8 km), villages in secondary or lesser towns (1.2 km) and rural villages (6.9 km). Likewise, geo-spatial analysis between the nearest public secondary school infrastructure and village shows an average distance of 1.18 km across the four settlements. However, villages located in peri-urban LGAs had an average distance of 1.km from village centre to the secondary school while it was 1.4 km in villages close to secondary towns. This geospatial analysis of the average catchment radius distance from village centre to nearest public secondary school shows that distance increases away from State capital or town—LGA headquarter. This explains that households travel farther as their location changes from cities to townships and interior rural settlements. Thus, explaining that distance (conceptualized as access) covered to facility is higher at rural than township and city spaces. Observations of travel time revealed that from the peri-urban village to LGA headquarter took between 20 to 25 mins, and between 45 and 50 mins to the state capital headquarter (Ibadan), while for lesser villages it was between 25 to 30 mins to the LGA headquarters and 120 mins to the state capital city in Ibadan.

Interviews revealed that quest for school access led to an increase in costs of transport and school levy, which shaped the rural dwellers affordability. The study is of the view that the dilemma of range and threshold in rural setting is flawed by the increasing time travel via the unconventional road track. The view is that while range may be achieved, affordability (most especially transport expenses) is a concern and often remains unachievable. The notion is that with little syncing between rural infrastructure needs and facility location planning standards, the local dwellers remain at the negative receiving-end of this dilemma of facility need, planning and politics of facility allocations.

8. Concluding remarks

The study questioned planning and political representatives’ role in service delivery. In explaining this, the study recognised distance as a stressor to rural access and affordability. It further explained that planning and politics in the location of facilities have been less efficient in correcting and managing rural accessibility and affordability. The study points that political representative as an actor in the advocacy for the provision of rural public good (facility and service delivery) remains irresponsive to rural interest. The evidence in the politicization of service delivery as against the justified facility maintenance and planning requirement limits achieving good governance. Studies (Agba et al., Citation2013; Gafar, Citation2017; Gauri, Citation2013; Koenane & Mangena, Citation2017; Omotoso, Citation2014) have mentioned that fairness and accountability remains as an underlying principle to governance. The fair as it relates to the study speaks to effective and responsive location of facility. With the needs and rural characteristics taken into consideration.

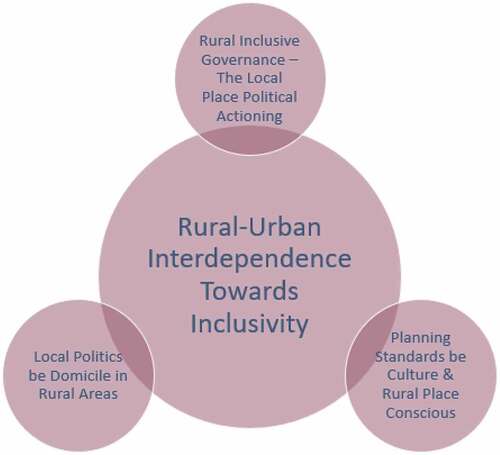

In this regard, the study evidence shows that political actors remain irresponsive and exhibit locational bias when public good (services) are to be allocated. This view can be attributed to limited participation, political interference across tiers of government, poor representation, and weak communicative democracy. This is justified in the view that collaboration among stakeholders and participation of local communities and residents in governance is key to infrastructure location and allocation. In Popoola (Citation2022b, p. 115), it was presented that a participatory local government chairman has the indirect possibility of influencing rural infrastructure development in Oyo State, Nigeria (p-value of 0.007933). To this end, the study recognise that the quest for space equality, advocacy planning and inclusive governance, bringing the rural areas into the fold of governance remains the way towards bringing about equality, inclusion, and representation which will indirectly lead to improved service delivery in the rural LGAs (ibid). The authors recognise that poor representation can be attributed to the idea of rural political representative resident in the city as against the village. A situation in which rural political representative resides in urban areas result to a colossal political misrepresentation experience. Therefore, political office holders must be made accountable for their offices and investment in facilities provided. This can only be achieved if they reside within their political constituent. Likewise, service delivery should be devoid of politicking and bias as against rural political party alignment or votes received during elections.

Further, the argument for rural place aligns for political representation to be less urban dweller and configured to be more rural domicile. The view is that this will further manage political representation and indirectly cultivate governance that is inclusive and participatory for the rural voters. Such that proper rural representation by the political class reflects good governance that is local place and planning conscious. In driving governance responsiveness and consciousness, local government managers as custodian and representative of governance should endeavour to focus on continuous maintenance of infrastructure as against a politically driven ideology of constructing a new one. The political show of facility construction as against maintenance in a rural area is what the study terms “irresponsible behaviour” in rural political governance. This when collectively looked at captures the argument along the quality of representation in service delivery towards achieving public interest for their continued needed good (service delivery).

In ensuring good governance in service delivery, the authors recognise that improving affordability and accessibility is critical. In achieving this, the role of local setting-oriented planning standard was forwarded. This is evident in the dichotomy of average travel distance across sampled villages. The study forwarded a need to create a physical (as in travel distance/access) and economic (cost in affordability) balance in facility location across rural spaces. To achieve this, the study recognise that dispersed and linear village arrangement should be discouraged to reduce access time to infrastructure and LGA headquarters and increase affordability in transport cost. This is because geographically dispersed, isolated remote villages are the worst affected in terms of infrastructure access, provision, and affordability.

Thus, the study recognises through framework () the need for a place-base, culture, and rural setting conscious service delivery responsiveness towards rural inclusion. The relevance of setting is also embedded in the varying needs of communities () based on their variant governance impact towards common good and interest experiences. These needs according to Chambers and Conway (Citation1992) speaks to capacity and assets (tangible and intangible) towards the achievement of a sustainable rural livelihood. According to Bano (Citation2019) and Popoola and Magidimisha (Citation2020b), these needs are embedded in good governance and effective planning. The relevance of the promoted access to the holistic social and physical infrastructure was elaborated in the reported experience in sampled villages.

The study points that the governance and planning for service delivery in rural areas is captured in the range and threshold dilemma. Thus, in arguing for improved service delivery, the authors recognise that there are other issues such as small and scattered population that explain the rural neglect—diseconomies of scale in service delivery as many of these facilities may suffer from investment error or under-utilisation. To manage this, the authors argue that the advocacy for compact or smart villages or rural communities is long overdue. As this remains one of the most viable and possible solutions to the affordability and accessibility problem that may arise due to facility range and threshold in rural areas. This approach will also attend to the needs of the existing unmapped and isolated smaller villages within the rural community. The view is that smart communities within the context of this study is a collection of villages that are easily accessible to each other to come together and motivate the provision of shared facilities. This is a smart-rural settlement that is made up of a collection of villages that has the needed threshold capacity to service infrastructure and the users travel experience, and the cost is within the range stipulated by planning standard. With this smart-rural area, a modern life within a rural space will be achieved thereby limiting rural-urban migration.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the comments of audience and anonymous reviewers at the International Symposium on Inclusive Cities in South Africa where the shorter version was presented. The research support under the SARChI Chair for Inclusive Cities is also appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ayobami Popoola

Ayobami Popoola is a trained geographer and now an Urban and Regional Planner with lifelong interest in Human Wellbeing and Livelihood. He has a BSc in Geography and MSc in Urban and Regional Planning, both from the University of Ibadan. His PhD in Town and Regional Planning was from University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Dr Popoola is currently a part of the team in the SARChI Chair for Inclusive Cities project located in the Department of Town and Regional Planning, School of Built Environment and Development Studies, UKZN as Post-Doctoral Research Fellow. The research chair is funded by NRF, South African Cities Network and others.

Hangwelani Magidimisha-Chipungu

Hangwelani Magidimisha-Chipungu is the SARChI-Chair for Inclusive Cities and a Professor in the Department of Town and Regional Planning at the University of Kwazulu-Natal. She serves on a number of boards at both national and international levels. She has also won numerous awards of excellence based on her work which has received international recognition. She has published widely in peer-reviewed journals and books; and her areas of interest are Inclusive Cities, Spatial Planning, Urban Design, Migration and Planning policy.

Lovemore Chipungu

Lovemore Chipungu is the co-chair SARChI-Chair for Inclusive Cities and a Professor in the Department of Housing at the University of Kwazulu-Natal. He is a Town and Regional Planner with a PhD in Town and Regional Planning; MSc in Rural and Urban Planning, BSc in Rural and Urban Planning.

References

- Abdullahi, A., & Ahmad, S. (2018). Good governance and local government administration in Nigeria: An imperative for sustainable development. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 7(4), 1522–23 https://isdsnet.com/ijds-v7n4-20.pdf.

- Abe, T., & Omotoso, F. (2021). Local government/governance system in Nigeria. In R. Ajayi & J. Fashagba (Eds.), Nigerian Politics (pp. 185–216). Springer.

- Acey, C. (2016). Managing wickedness in the Niger Delta: Can a new approach to multi-stakeholder governance increase voice and sustainability? Landscape and Urban Planning, 154 October 2016 , 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.03.014

- Adebayo, K. 2018. Apete-Awotan road: A menace Ajimobi abandoned for 7 years because residents voted opposition candidate. International Centre for Investigative Reporting. https://www.icirnigeria.org/apete-awotan-road-a-menace-ajimobi-abandoned-for-7-years-because-people-voted-opposition-candidate/ [Accessed 11 April 2019]

- Adesopo, A. (2011). Inventing participatory planning and budgeting for participatory local governance in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(7), 111–125 http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._7%3B_Special_Issue_April_2011/13.pdf.

- Agba, M. S., Akwara, A. F., & Idu, A. (2013). Local government and social service delivery in Nigeria: A content analysis. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2(2), 455–462 http://dx.doi.org/10.5901/ajis.2013.v2n2p455.

- Agbakoba, O., & Ogbonna, H. (2004). Local government administration and development in Nigeria. Hurilaws.

- Agboeze, M., & Nwankwo, E. (2018). Actualizing sustainable development goal‐11 in rural Nigeria: The role of adult literacy education and tourism development. Business Strategy & Development, 1(3), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.21

- Agbola, T. 2001. Planning laws, building standards and the politics of illegality in human settlement: A case study from Ibadan, Nigeria. Network-Association of European Researchers on Urbanisation in the South. http://n-aerus.net/web/sat/workshops/2001/papers/agbola.pdf.

- Agu, S., Okeke, V., & Idike, A. (2013). Voters apathy and revival of genuine political participation in Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3), 439–448 http://dx.doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n3p439

- Allmendinger, P., & Thomas, H. (Eds). (1998). Urban planning and the new right. Routledge.

- Alobo, E. (2014). Promoting the culture of democracy and good governance in local government councils in Nigeria: The role of the legislature. British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 18(1):19–38 http://www.bjournal.co.uk/BJASS.aspx.

- Altshuler, A. (1965). The goals of comprehensive planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(3), 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978165

- Ama, H., Moorad, F., & Mukhopadyay, S. (2020). Assessment of stakeholders views on accessing quality and equity of basic education in rural communities of Abia State, Nigeria. Educational Research and Reviews, 15(8), 454–464. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2020.4018

- Asian Development Bank. 1995. Governance: Sound development management. ADB. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_nlinks&ref=000097&pid=S1414-753X200700020000700006&lng=en [Accessed 04 April 2022]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017. Online sample size calculator. National statistical service. www.Nss.gov.au [Accessed 18 July 2017]

- Bano, M. (2019). Partnerships and the good-governance agenda: Improving service delivery through state–NGO collaborations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(6), 1270–1283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9937-y

- Bello-Schunemann, J., & Porter, A. (2017). Building the future infrastructure in Nigeria until 2040. Institute for Security Studies (ISS) and the Frederick S. In Pardee center for international futures at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies. University of Denver 28 10260404 https://issafrica.org/research/west-africa-report/building-the-future-infrastructure-in-nigeria-until-2040 .

- Bernstein, J., Johnson, N., & Arslan, A. (2019). Meta-evidence review on the impacts of investments in agricultural and rural development on sustainable development goals 1 and 2. IFAD Research Series 2019 , 38 http://www.ifad.org/research/annex_38.

- Buhr, W. (2003). What is infrastructure? In Volkswirtschaftliche Diskussionsbeiträge, No. 107-03. Universität Siegen, Fakultät III, Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Wirtschaftsinformatik und Wirtschaftsrecht.

- Bye, H., Bygnes, S., & Ivarsflaten, E. (2021). The local-national gap in intergroup attitudes and far-right underperformance in local elections. Frontiers in Political Science, 3 May 2021 , 48. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.660088

- Cader, C., Radu, A., Bertheau, P., & Blechinger, P. (2018). Remote sensing techniques for village identification: Improved electrification planning for Zambia Mpholo, M, Steuerwald, D, Kukeera, T. In Africa-EU renewable energy research and innovation symposium (pp. 91–96). Springer.

- Campbell, H., & Marshall, R. (2002). Utilitarianism’s bad breath? A re-evaluation of the public interest justification for planning. Planning Theory, 1(2), 163–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/147309520200100205

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Institute of Development Studies (UK).

- Correa, T., & Pavez, I. (2016). Digital inclusion in rural areas: A qualitative exploration of challenges faced by people from isolated communities. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12154

- Faludi, A. (1983). Critical rationalism and planning methodology. Urban Studies, 20(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420988320080521

- Faludi, A. (2013). A reader in planning theory of Urban and Regional Planning Series. Elsevier. 5(1483292894), 9781483292892 https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-10937-6.

- Friedmann, J Planning in the Public Domain. From Knowledge to Action (Princeton University Press)9780691022680

- Frischmann, B. M. 2017. Understanding the Role of the BBC as a Provider of Public Infrastructure. Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper No. 507. Jacob Burns Institute for Advanced Legal Studies. [Online]. Available at: [Accessed 12 April http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2897777].

- Gafar, B. (2017). The travail of service delivery and developmental failure in post-Independence Nigeria. Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research, 9(3), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPAPR2017.0406

- Gauri, V. (2013). Redressing grievances and complaints regarding basic service delivery. World Development, 41 January 2013 , 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.027

- Grant, L. (1985). Urban innovation, the transformation of London’s Docklands (1968-1984). Gower Publishing Company.

- Grgić, I., Žimbrek, T., Tratnik, M., Markovina, J., & Juračak, J. (2010). Quality of life in rural areas of Croatia: To stay or to leave? African Journal of Agricultural Research, 5(8), 650–653 doi:10.5897/AJAR10.613.

- Grindle, M. (2004). Good enough governance: Poverty reduction and reform in developing Countries’. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions, 17(4), 525–548. 10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00256.x

- Ibok, E. (2014). Local governance and service delivery in Nigeria. Caribbean Journal of Sciences and Technology (CJST), 2(1), 536–541 https://caribjscitech.com/index.php/cjst/article/view/134/108.

- Innes, J. (1996). Planning through consensus building: A new view of the comprehensive planning ideal. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(4), 460–472. https://do.org/10.1080/01944369608975712

- Islam, M. 2021. An academic overview on how to bridge the gap between the government and the rural people. https://www.highereducationdigest.com/an-academic-overview-on-how-to-bridge-the-gap-between-the-government-and-the-rural-people/ Higher Education Digest

- Jochimsen, R. (1966). Theorie der Infrastruktur, Grundlagen dermarktwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. J C B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tübingen.

- Khemani, S. 2001. Fiscal federalism and service delivery in Nigeria: The role of states and local governments. Prepared for the Nigerian PER Steering Committee. World Bank, 24th July. http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/decentralization/March2003Seminar/FiscalFedReport.pdf. accessed August 03 2022

- Koenane, M., & Mangena, F. (2017). Ethics, accountability and democracy as pillars of good governance-case of South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(5), 61–73 https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/59098.

- Lawal, T. (2014). Local government and rural infrastructural delivery in Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 4(4), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v4-i4/771

- Leone, F. (2013). The role of politics in the planning process. Regional Insights, 4(2), 15–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/20429843.2013.10795999

- Majekodunmi, A. (2012). The state of local government and service delivery in Nigeria: Challenges and prospects. Africa’s Public Service Delivery & Performance Review, 1(3), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v1i3.37

- Mangai, M. (2016). The dynamics of failing service delivery in Nigeria and Ghana. Developments in Administration, 1(1), 85–116. https://doi.org/10.46996/dina.v1i1.5101

- Marios, C. (1979). Planning Theory and Philosophy. USA, Tavistock Publications Ltd.

- Mawani, V. (2019). Unmapped water access: Locating the role of religion in access to municipal water supply in Ahmedabad. Water, 11(6), 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11061282

- McKay, L., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2021). Political trust in the “Places that don’t matter”. Frontiers in Political Science, 3 April , 31. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.642236

- Mellor, J. (2014). High rural population density Africa–What are the growth requirements and who participates? Food Policy, 48 October 2014 , 66–75. https://do.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.03.002

- Okojie, CA. 2009. Decentralization and public service delivery in Nigeria. Nigeria Strategy Support Program (NSSP) Background paper no. NSSP 004. International Food Policy Research Institute: Abuja, Nigeria. https://media.africaportal.org/documents/NSSP_Background_Paper_4.pdf

- Olujimi, J. (2008). Development control. Department of Geography and Planning, Adekunle Ajasin University.

- Olujimi, J. 2009. Planning standards as effective tools for development control. Paper presented at Stakeholder Forum Conference organised by Ondo State Ministry of Physical Planning and Urban Development at Ondo State Cultural Centre, Akure, Nigeria on (Ondo State Ministry of Physical Planning and Urban Development) 23-24 November.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267982549_PLANNING_STANDARDS_AS_EFFECTIVE_TOOLS_FOR_DEVELOPMENT_CONTROL/citations

- Omar, M. (2009). Urban governance and service delivery in Nigeria. Development in Practice, 19(1), 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520802576393

- Ọmọbọwale, A., & Olutayọ, A. (2010). Political clientelism and rural development in south-western Nigeria. Africa, 80(3), 453–472. https://doi.org/10.3366/afr.2010.0305

- Omotoso, F. (2014). Public-service ethics and accountability for effective service delivery in Nigeria. Africa Today, 60(3), 119–139. https://oyostate.gov.ng/ajimobi-congratulates-buhari-seeks-support-for-apc-governorship-assembly-candidates/

- OYSG. 2019. Ajimobi congratulates Buhari, seeks support for APC Governorship, Assembly Candidates. https://oyostate.gov.ng/ajimobi-congratulates-buhari-seeks-support-for-apc-governorship-assembly-candidates/. Accessed 11 April 2019

- Popoola, A. (2022a). Rural setting: The paradox of its accessibility and affordability in the urban planning and political actioning. Conference proceedings for international symposium on inclusive cities: achieving inclusive cities through a multidisciplinary approach. Journal of Inclusive Cities and Built Environment, 2(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.54030/2788-564X/2022/cp1v2a11

- Popoola, A. (2022b). The politics of infrastructural provision in rural areas of Oyo State Nigeria. African Sociological Review, 26(1), 94–126.

- Popoola, A., Blamah, N., Mosima, C., Nkosi, M., Medayese, S., Chipungu, L., & Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. (2021). The language of struggle and radical activism as an inclusive city tool among the neglected urban poor of South Africa. In H. Magidimisha-Chipungu & L. Chipungu (Eds.), Urban Inclusivity in Southern Africa (pp. 417–445). Springer International Publishing.

- Popoola, A., & Hangwelani, H. (2019a). Rural energy condition in Oyo State: Present and future perspectives to the untapped resources. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 9(5), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.7558

- Popoola, A., & Magidimisha, H. 2019b. Will rural areas disappear? Participatory governance and infrastructure provision in Oyo State, Nigeria. In C. Tembo-Silungwe, I. Musonda, & C. Okoro eds. (Pp. 12–26). Proceedings for the 6th International Conference of Development and Investment-Strategied for Africa. DII-2019, 24-26 July 2019, Livingstone, Zambia.

- Popoola, A., & Magidimisha, H. (2020a). Investigating the roles played by selected agencies in infrastructure development, M. A. Mafukata & K. A Tshikolomo Eds., African perspectives on reshaping rural development. 289–319. IGI Global. 23303271; e. 23303271; e 2330328X.2330328X.

- Popoola, A., & Magidimisha, H. (2020b). The dilemma of rural planning and planners in Oyo State, Nigeria. Bulletin of Geography, 47(47), 75–93 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/bog-2020-0005.

- Popoola, A. A., Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. H., & Chipungu, L. (2022). Profiling the wellbeing of residents in peri-urban villages and rural communities. African Journal of Development Studies (Formerly AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society), 12(1), 267–295. https://doi.org/10.31920/2634-3649/2022/v12n1a14

- Rauch, T. (2014). New ruralities in the context of global economic and environmental change – Are small-scale farmers bound to disappear? Geographica Helvetica, 69(4), 227–237. https://do.org/10.5194/gh-69-227-2014

- Sandercock, L. (1998). Towards cosmopolis: Planning for multicultural cities. John Wiley and Sons.

- Sarantakos, S. (2005). Social Research (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sirayi, M., Kanyane, M., & Verdini, G. (Eds.). (2021). Culture and rural–urban revitalisation in South Africa: Indigenous knowledge, policies, and planning. Routledge.

- The Investopedia Team. 2022. What is infrastructure. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/infrastructure.asp

- United Nations Development Programme. (1997). Governance for sustainable human Development. UNDP policy document.

- Vagale, L. R. (eds). (2000). Manual of space standard for urban development. A publication of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Polytechnic Ibadan. Nigeria.

- Woldesenbet, W. (2020). Analyzing multi-stakeholder collaborative governance practices in urban water projects in Addis Ababa City: Procedures, priorities, and structures. Applied Water Science, 10(1), 1–19. https://do.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1137-z

- World Bank. (1992). Governance and Development (World Bank: Washington D.C)0-8213-2094-7 https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/604951468739447676/pdf/multi-page.pdf .

- Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. (2009). Unstructured interviews. In B. Wildemuth (Ed.), Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science (pp. 222–231). Libraries Unlimited.