Abstract

The majority of Americans will meet the diagnostic criteria of a mental health condition during their lifetime and most will go without treatment oftentimes due to perceived stigma. This study evaluated the impact of the film, “Lift the Mask: Portraits of Life with Mental Illness”, on stigma reduction related to mental health conditions. The film ran from 2018 to 2020 and was across the United States. A total of 254 people completed a pre and post survey and were eligible for this analysis. Paired t-tests using a matched sample of participant pre and post surveys were used to assess change in attitudes toward mental health conditions before and after the film screening and results were stratified by mental health professionals and non-mental health professionals. After viewing the film, stigma related to mental health conditions was significantly reduced among mental health professionals and those outside the profession. Films focused on humanizing mental health conditions can reduce stigma and should be incorporated into interventions.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

By all measures, there is a global mental health crisis.

Nearly 800 million people on this planet live with a mental illness. In America, more than half go without treatment often due to perceived social stigma that labels people as crazy or scary. The risk of facing discrimination in personal, professional, and cultural circles creates additional barriers. The most significant negative impact of unaddressed mental health illness is suicide, the most preventable causes of death we have.

This research evaluates the ability of film intervention to positively influence viewers’ attitude toward mental health conditions pre and post-documentary screening. After viewing, stigma related to mental health conditions was significantly reduced among mental health professionals and those outside the profession.

This study aligns with our commitment to promote open, judgment-free dialogue to normalize the conversation around mental health and reduce suicide and overdoses of people living with a mental health illness.

1. Introduction

An estimated 50% of Americans will meet the diagnostic criteria of a mental health condition during their lifetime and more than half of them will go without treatment (Lê Cook et al., Citation2013; Kessler et al., Citation2007). The prevalence of mental health conditions including anxiety and depression are higher in women than in men and in younger adults compared with older adults.(Kessler et al., Citation2007; Rosenfield & Mouzon, Citation2013; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2020) Although mental health conditions are highly prevalent in the United States, they are nevertheless highly stigmatized and discriminated against (Parcesepe & Cabassa, Citation2013).

The classic definition of the term “stigma” is a “situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance” (Goffman, Citation2009). Since Goffman’s definition in 1963, psychologists and sociologists have applied this concept of stigma to several marginalized groups including people living with HIV, minority populations, and people who have been imprisoned, to name a few. Stigma has further been expanded to define several types of stigma including public stigma and self-stigma. Public stigma is prejudice and discrimination towards a particular group of people resulting in their stigmatization; whereas, self-stigma occurs when the person who is being stigmatized internalizes public stigma and applies it to their own life (Sheehan et al., Citation2017).

Public stigma related to mental health conditions, includes a general community-level perception that people living with mental health conditions are generally dangerous, blameworthy, and/or incompetent and may include other negative perceptions (Corrigan & Shapiro, Citation2010). Self-stigma related to mental health conditions occurs when individuals with a mental health condition internalize the public stigma and believe they deserve the negative attitudes held against them (Dubreucq et al., Citation2021). Stigma is not only psychologically damaging, but it often interferes with the normal daily life of people with mental health conditions, decreases their willingness to seek treatment, leads to social isolation, and increases the risk for suicide (Chi et al., Citation2014; Connell et al., Citation2012; Fox et al., Citation2018; Henderson et al., Citation2013; Herek et al., Citation2009).

While film can have positive effects on behavior, it can also negatively influence it and due to the documented impact film can have on behavior policies have been put in place to reduce and limit positive media portrayals on the use of alcohol and tobacco (Bergamini et al., Citation2013; McKay et al., Citation2020). Thus, it can be deduced that the impact of film is widely acknowledged. However, film as a positive influence on reducing stigma has not been adequately studied. While research demonstrates that entertainment and news media have oftentimes depicted people living with mental health conditions as violent or marginalized in some way creating negative portrayals, media that humanizes and creates a positive connection with the audience has the power to improve public perception and decrease stigma towards of people living with mental health conditions (Kimmerle & Cress, Citation2013; Klin & Lemish, Citation2008; Macpherson & Warrender, Citation2018; Riles et al., Citation2021). Education and positive contact with people who have a mental health conditions are effective approaches to reducing stigma (Holmes et al., Citation1999; Link & Cullen, Citation1986; Tanaka et al., Citation2003). Communication strategies, including direct and indirect contact between participants and those with a mental health condition (e.g., film, lectures, leaflets, seminars, and videos) have been used to reduce stigma (Brown et al., Citation2010; Janoušková et al., Citation2017; Quinn et al., Citation2011; Winkler et al., Citation2017). Film, in particular, can simultaneously educate about mental health conditions and connect people with others who have mental health conditions in order to build both knowledge and develop empathy and have been shown to significant decrease stigma among certain groups (Chan et al., Citation2009; Kerby et al., Citation2008). The study completed by Chan et al used a randomized case crossover design (pre-test, post-test, and 1-month follow up) to assess the effect of three versions of schizophrenia stigma reduction programs among secondary students in Hong Kong. One version included education followed by video-based content, video-based content followed by education, and finally education without the video-based content. The investigators found those in the education followed by video-based content reported significantly reduced stigmatizing attitudes, shorter social distance towards people with schizophrenia, and higher knowledge about schizophrenia compared with the education only group (Chan et al., Citation2009). In another randomized case crossover study (pre-test, post-test, and 8-week follow-up) completed by Kerby et al, subjects were randomized to either watching a “talking heads” documentary on the personal experiences of stigma from three mental health professionals and a first-person narrative on the experiences related to psychosis during one day or a control documentary unrelated to mental health. This study found that compared to the control group, the group who watched the documentaries on stigma and mental health were more likely to report shorter social distance and improved general attitudes towards people with mental health conditions. This study builds upon previous studies on the effect of film on reducing stigma on mental health conditions by evaluating a feature length documentary that follows four people who have been impacted by their own or a loved one’s mental health condition. Additionally, this study has a relatively larger sample size than the previous studies, includes new scales on mental health stigma and innovative analytic techniques that provide new insight into measuring a reduction in study, and stratifies the results by those identifying as mental health professionals and those in the general population.

This study aimed to examine the impact of the film, “Lift the Mask: Portraits of Life with Mental Illness” on decreasing stigma of people living with mental health conditions among diverse population groups across the United States. The film was created to normalize mental health conditions and conversations about mental health, which was created as a way to counteract the negative portrayal of mental health conditions through popular media outlets (Carmichael et al., Citation2019; Ross et al., Citation2019; Stuart, Citation2006). A pre-test post-test survey design was implemented to assess change in stigma felts towards people living with mental health conditions before and after the film. The hypothesis was that the film would reduce stigma related to mental health among audience members. This paper presents the findings from the pre-post evaluation and discusses the role film can play in reducing stigma related to mental health conditions.

1.1 Aims of the study

To identify the impact of the film on reducing stigma related to mental health conditions;

To explore whether the film reduced mental health stigma for the general population and those who are mental health professionals;

To develop a new framework (QPSS) to examine the effectiveness of a film intervention to reduce stigma related to mental health conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Design and study population

Between 2018 and 2020, a film developed to humanize mental health conditions entitled, “Lift the Mask: Portraits of People with Mental Illness” was screened across 16 states in the United States. Pre-test online surveys were administered prior to the person’s viewing of the film. Most pre-tests were administered within 1 hour of viewing the film and the remaining spread evenly across the ten day’s prior. Post-tests were online surveys administered within 10 days after the conclusion of the film. The film was shown on public and private university campuses, in state government training sessions, and for-profit and not-for-profit corporate mental health awareness events. Anyone over 18 years of age was eligible to consent and participate in the study. Information on participant demographics (n = 254) is available in . The event was open to the people from each organization as well as the surrounding community. Participants’ pre- and post-surveys were matched by participant initials of their best friend and their high-school mascot reported in both surveys. The study adhered to the ethical criteria put forth by the Belmont Report (Sims, Citation2010) and was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at The Penn State University College of Medicine.

Table 1. Population Characteristics

2.2 The intervention

The intervention included first a screening of the film, “Lift the Mask Portraits of Life with Mental Illness”, followed by a panel discussion. The film shown between pre- and post-tests was a high-quality film of cross-cutting vignettes with people who were living with a mental health condition. The vignettes were designed to make the viewer see the human side of those living with a mental health condition, and provide a different vantage point for what they might otherwise have experienced. Briefly, the vignettes were: a transgender youth and his mother discussing his suicidal ideation, a young adult who had undergone ECT treatment, people who had a loved one who suffered from depression, bipolar disorder, or had died by suicide, someone suffering from depression, and a student working through attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. After the film, a panel discussion was provided in order to answer questions and open a dialogue to discuss and contextualize the film.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Demographic and mental health characteristics

Age and gender were collected, as well as the location of where the participant viewed the film. The location was categorized by location as Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, West, and Southwest and by type as private university, public university, and not a university. Participants were asked if they had been diagnosed with a mental health condition and if they had disclosed their mental health condition to their family or friends. The question on whether the participant had disclosed their mental health condition had the following responses (yes, no, prefer not to say, and I do not have a mental illness) and within analyses, yes and no were compared among those who reported having a mental illness. Participants were also asked if they were a mental health professional, if their job involved providing services/treatment for persons with a mental illness, and if they had a friend, relative, or coworker with a mental illness. After the film was shown, participants were asked if they were more likely to disclose their mental health condition to their family and friends. The participants could answer this question on a 5-point Likert scale of strongly disagree to strongly agree and prefer not to say and the analysis was limited to those who reported having a mental illness in the survey.

2.3.2 Stigma of mental health conditions

The stigma of mental health conditions in the population was measured in three ways. First, a Quell Perceived Stigma Scale (QPSS), a modified Perceived Stigma Questionnaire (Ikeme, Citation2012; Link, Citation1985, Citation1987), was used. The QPSS included the following questions: “I would willingly accept a person that had a diagnosed mental illness as a close friend.”; “I am afraid of people with a mental illness.”; “I would believe that a person who has been in a mental hospital is just as intelligent as the average person.”; I believe that a person with a history of mental illness is just as trustworthy as the average person.”; If I were an employer, I would hire a person with a history of mental illness if s/he is qualified for the job.”; “I would treat a person with a history of mental illness just as I would treat anyone”; “I would be reluctant to date someone who has been hospitalized for a mental illness.”; “If I knew a person had been hospitalized for a mental health illness, I would value his or her opinion less seriously.” The possible responses were “not at all”, “a little”, “some”, “a lot”, and “a great deal”. For this scale, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.779 for the pre-survey and 0.798 for the post-survey, indicating good reliability. The kurtosis for the QPSS scale for the pre-survey was −0.48 and was −0.08 for the post-survey indicating a relatively normal distribution (Lei & Lomax, Citation2005). The skewness for the QPSS scale was −0.47 in the pre-survey −0.08 and in the post-survey was indicating that data from this scale are moderately left-skewed (Lei & Lomax, Citation2005). The scale was examined by adding the score for each question with the higher numbers indicating lower stigma. A paired t-test assessed whether the mean difference between the pre and post measurements were different from zero.

Second, questions were asked about stigma related to people receiving help for their mental illness including the following: “I would feel they were inadequate if they went to a therapist for psychological help.”; “I would have more respect for them for seeking mental health care treatment.”; “My confidence in them would NOT be threatened if they sought professional help.”; “I would feel comfortable encouraging them to seek help.”; “It would make me feel they were inferior to ask a therapist for help.”; “I would feel comfortable sitting with them on their bad days.”. The possible responses were “not at all”, “a little”, “some”, “a lot”, and “a great deal”. For this scale, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.336 for the pre-survey and 0.516 for the post-survey, indicating fair reliability. Further, the kurtosis for the pre-survey scale was −0.10 and for the post-survey scale was 6.45 indicating a non-normal distribution in the post-survey (Lei & Lomax, Citation2005). The skewness for the scale was −0.67 in the pre-survey −2.19 and in the post-survey was indicating that data from this scale are highly left-skewed for the post-survey especially (Lei & Lomax, Citation2005). Therefore, we did not test for mean differences for these questions on a scale. A paired t-test assessed whether the mean difference between the pre and post measurements were different from zero.

Third, a scale on the willingness of engaging with people who have a mental health condition in a variety of ways was included with the following questions: “How would you feel about renting a room in your home to someone with a mental illness?”; “How would you feel about working with someone with a mental illness?”; “How would you feel about having someone with a mental illness as your neighbor?”; “How would you feel about having someone with a mental health illness as the caretaker of your children?”; “How would you feel about introducing someone with a mental illness to your friends?”; “How would you feel about recommending someone with a mental illness for a job working with someone you know?”. The possible responses were “definitely willing”, “probably willing”, “probably unwilling”, and “unwilling”. For this scale, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.825 for the pre-survey and 0.838 for the post-survey, indicating good reliability. The kurtosis for this scale in the pre-survey was −0.98 and was 0.84 in the post-survey indicating a relatively normal distribution (Lei & Lomax, Citation2005). The skewness for this scale in the pre-survey was −0.09 and was −0.92 in the post-survey indicating moderate left skewness in the post-survey (Lei & Lomax, Citation2005). The scale for willingness to engage with people who have a mental health condition was examined by adding the score for each question with the higher numbers indicating lower stigma. A paired t-test assessed whether the mean difference between the pre and post measurements were different from zero.

Finally, an open-ended question, “Please comment on the film’s effectiveness to humanize mental illness” was included in the survey to collect nuanced narrative data that the quantitative scales may not uncover.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The study population included in this analysis were only those who had matched pre and post surveys (n = 254). Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare mental health professionals with those who were not mental health professionals in the demographic table. Paired t-tests were used to assess changes in pre-post survey answers on stigma-related questions, the t-test statistic, mean, standard deviation, the effect size shown by Cohen’s D, and p-value are reported for each association. Cohen’s D was calculated as the absolute value of the mean divided by the standard deviation of the paired t-test. Results were stratified by mental health professional (yes/no) as it was expected that mental health professionals may have a different experience of the film. SAS 9.4 was used to conduct the univariate and bivariate analyses and an alpha level of <0.05 was used to determine significance. To establish the overall magnitude of shift for a specific question, we calculated the average number of steps changed on the Likert scale for the same individuals between pre- and post-tests. Lastly, a venncloud was constructed from the open-ended question to assess words most commonly used for the total study population and then stratified by mental health professionals and non-mental health professionals.

3. Results

Participant demographics are reported in Table . In total, 254 people participated in the pre and post surveys. The largest age group who participated were 18–25 years of age (40.9%). The majority of participants were women (81.9%). Among the participants 31.5% reported having been diagnosed with a mental health condition, and of those 93.8% disclosed their mental health condition to their family and 87.5% disclosed their mental health condition to their friends. Within the sample, 16.5% reported they worked as a mental health professional and 43.3% reported their job involves providing services/treatment for persons with a mental illness. Further, 92.9% of participants reported they have a friend or relative with a mental illness and 70.9% reported they worked with a person who had a mental illness. The largest group of participants viewed the film in the Northeastern United States (37.0%) and viewed the film at a public university (45.3%). After the film was shown, 36.3% of participants strongly agreed they would disclose their mental health condition to family members and 39.4% of participants strongly agreed they would disclose their mental health condition to friends.

In Table , the results of a chi-square test comparing participants who were and were not mental health professionals are shown. There was no significant difference between the two groups in having a friend with a mental illness, having a mental illness themselves, or disclosing their mental illness. A significantly higher proportion of participants who were between 26–49 years of age, women, had worked with people who had a mental illness, and had a job that involves providing services for persons with a mental illness were mental health professionals. There was one person who was transgender in our sample and one person who reported they preferred not to say whether they disclosed their mental health condition to their friends, therefore we set those values to missing for the analyses. While both mental health and non-mental health professionals reported their agreement to disclosing their mental health condition to their family after the film similarly, mental health professionals were more likely to report disclosing their mental health condition to friends compared with non-mental health professionals.

Table shows the results of the QPSS which illustrates the change in stigma of mental health conditions comparing pre- and post-surveys among all participants and then stratified by not mental health professionals and mental health professionals. For each question, the mean of responses for the pre-survey was compared with the mean of responses in the post-survey and the significance determined by a paired t-test with an alpha level of less than 0.05. In every question, stigma was reduced among all participants. Among mental health professionals, stigma was low for the following questions in the pre-survey and did not change significantly in the post-survey: “I would willingly accept a person that had a diagnosed mental illness as a close friend.”; “I am afraid of people with a mental health illness.”; “I would be reluctant to date someone who has been hospitalized for a mental illness.”; and “If I knew a person had been hospitalized for a mental health illness, I would value his or her opinions less seriously.” When the QPSS was examined as a scale, stigma was reduced for all participants, and both mental health professionals and those who were not mental health professionals.

Table 2. Stigma of mental health conditions (QPSS) comparing pre- and post- survey results stratified by mental health professional

Table shows results from paired t-tests comparing the findings from the pre and post questions on the stigma related to the treatment of mental health conditions. Among the total population and the population of non-mental health professionals, stigma was reduced for all questions except, “I would feel they were inadequate if they went to a therapist for psychological help.” and “It would make me feel they were inferior to ask a therapist for help.” Among mental health professionals, the two only questions with significant stigma reduction were “I would feel comfortable sitting with them on their bad days.”; and “My confidence in them would NOT be threatened if they sought professional help.”

Table 3. Stigma of mental health treatment comparing pre- and post- survey results stratified by mental health professional

Table shows the findings from paired t-tests on questions related to feelings towards discrimination of people with a mental health condition comparing the pre and post-survey results. Discrimination was significantly reduced in all questions for the total population and for non-mental health professionals. Among mental health professionals discrimination was significantly reduced for two questions including “How would you feel about having someone with a mental illness as your neighbor?” and “How would you feel about recommending someone with a mental illness for a job working with someone you know?” Stigma was reduced for all groups when discrimination was measured as a scale.

Table 4. Discrimination of people with mental health conditions comparing pre- and post- survey results stratified by mental health professional

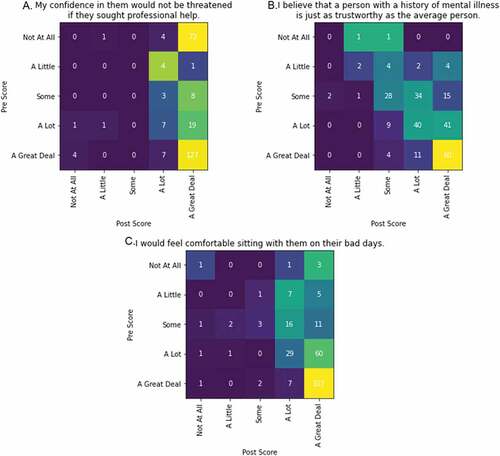

The overall magnitude of shift for each question was examined by calculating the average number of steps changed on the Likert scale for the same individuals between the pre- and post-surveys. The three questions with the largest magnitude of shift can be seen in Figure . The starting value (pre-test) can be seen on the Y-axis and ending value (post-test) can be seen on the X axis. Thus, if there was no effect to their position between the pre- post- survey, all values would be along the diagonal (i.e., all those users who start at “Not at All” in the top row, end at “Not at all” in the first column, all those users who start at “A little” in the second row, end at “A little” in the second column, and so on). Some noise is expected in the administration of the survey, as people’s attitudes and interpretations vary mildly between pre- and post-test, which would tend to put some of the people around the diagonal (i.e., some people move up or down a step between pre- and post-tests as a course of normal variability). The maximal change could be found in all of the people ending at the end of the scale indicative of minimal stigma (e.g., “I would feel comfortable sitting with them on their bad days” would have all users, regardless of starting position (row) in the “A Great Deal” column.) What we observe in Figure is that for the questions shown, there is a significant effect, with many of the respondents, regardless of starting position, ending in a position that indicates a stance with minimal stigma. For some of these questions we observe no real effect (e.g., “My confidence in them would not be threatened if they sought professional help.”) because the majority of the respondents already held the stance with the minimal stigma at the pre-test. For others, we see a small but consistent effect (e.g., “I believe that a person with mental illness is just as trustworthy as the average person”), which saw users, regardless of starting position, take one step towards the position with minimal stigma.

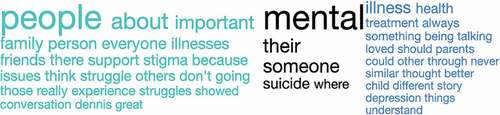

Figure shows a venncloud (Coppersmith & Kelly, Citation2014) that highlights the differences in language used in response to a question on the post survey asking about “the most important ideas or insights you took away from the film”. The words in green were more likely to be used by mental health professionals, the words in blue were more likely to be used by those who were not mental health professionals, and the words in black were about equally likely to be used by both groups.

4. Discussion

This study provides new evidence of the impact film can have on reducing stigma of mental health conditions. According to a review of stigma reduction interventions, personal testimonies are an important factor in an anti-stigma campaign, as is multiple points of social contact including film and multiple speakers (Gronholm et al., Citation2017). Specifically for students, films including people who have a mental health condition are one of the more effective interventions (Gronholm et al., Citation2017). The current research provides an evaluation of a film intervention that included multiple personal testimonies and a panel discussion including people from the film.

There is a dearth of studies examining the effect of film on the reduction of stigma focused on mental health professionals. Results from this study show that for both the general population and mental health professionals, stigma was reduced for almost every question. This is congruent with previous research suggesting film or video is an effective intervention to reduce mental health stigma (Chan et al., Citation2009; Goodwin et al., Citation2021; Gronholm et al., Citation2017; Ito-Jaeger et al., Citation2021; Kerby et al., Citation2008). In the rare cases that stigma reduction was not demonstrated when comparing the pre and post surveys, the level of stigma was already quite low before the film and, although not statistically significant, there was often a still a reduction in stigma. While a reduction in stigma was found for both the general population and those who were mental health professionals, mental health professionals did not have a demonstrated stigma reduction for all the questions that were found in the general population. This was likely due to the low stigma in the pre-survey for those questions among mental health professionals such as, “I am afraid of people with a mental health illness;” “If I knew a person had been hospitalized for a mental health illness, I would value his or her opinions less seriously;” and “I would have more respect for them for seeking mental health care treatment.” Additionally, among participants who reported having been diagnosed with a mental health condition, after the film 72.3% stated being more likely to disclose their mental illness to their friends and family (67.2%). This shows the films effectiveness in reducing stigma among those who have mental health conditions as research has shown that disclosing one’s mental health condition is associated with lower stigma stress (Rüsch et al., Citation2014).

The qualitative findings in the venncloud show that mental health professionals reflect more on the human aspects of people with mental health conditions, using words like people, person, family and friends. Contrastively, those who saw the film who were not mental health professionals more often reflected thoughts about treatment, depression, and the parent–child relationship. This finding on the different language used between mental health professionals and those who are not mental health professionals, was expected as previous research shows that mental health professionals have greater negative cognitive associations with stigmatizing words and have most likely been trained to humanize mental health conditions (Ashford et al., Citation2019; Charles & Bentley, Citation2016).

This method of screening a film and conducting a pre-post study design was a feasible method and could be used for future evaluations. In addition to showing the film, a panel discussion was held after the screening and likely contributed to the film’s success. Additionally, connecting with event registration lists to email all registered attendees to complete a survey and then to offer the survey again at the end of the film likely helped with participation in the survey. Further, the survey was mobile friendly and was made available through emailed survey links and QR codes at the screening. Including qualitative and quantitative questions allowed for our results to be comparable across sites and to include narrative data providing richer data to explain the quantitative results. We recommend including questions to ensure surveys can be matched, questions on working in the mental health profession, defining mental illness/mental health conditions at the beginning of the survey, and allowing for open-ended responses. The survey would have been improved by asking students their major (to determine who is studying psychology or a related field), asking about family history of mental illness, as well as including demographic questions such as race, ethnicity, marital status, and number of children.

The findings from this study will be useful for others who would like to evaluate the use of a media tool to decrease rates of stigma related to mental health conditions. Additionally, this evaluation highlights the importance of assessing a change in stigma separately for groups outside the mental health profession and for mental health professionals. In the future, it may be useful to target other specific population groups such as the First Responder community, Front Line Health Care Professionals, and Athletes, as these groups may have a higher burden of mental health conditions compared to people outside those professions. Furthermore, this research highlights that interventions to reduce stigma, such as film, will likely be useful for people working in the mental health field and likewise in professions such as First Responders, Front Line Health Care Professionals and Athletes.

5. Limitations

There are five important limitations to consider when interpreting the study results. The first is that our study population were people who opted to view a film on mental illness. It is likely that the study population is more interested in mental illness and were primed to have their own stigma challenged. Additionally, the people who participated in the film screenings and the pre and post surveys were mostly women (79.7% for the general population and 92.9% for mental health professionals) and younger (18–25 years for the general population and 26–49 years for the mental health professionals). This limits the generalizability of our study. It is unclear how the film would impact other populations across the United States. Future screenings and research on the film’s effectiveness should be offered across organization types and demographic profiles to ensure greater access to this tool for stigma reduction. Second, participants may have responded in a way they thought the researchers would like them to respond. This bias is known as the Hawthorne effect and it may have altered our results to show a larger change comparing pre and post surveys than actually existed. However, it is also possible the Hawthorne effect affected both the pre and post results equally resulting in non-differential misclassification which would not impact our results. Third, our study has a relatively small number of mental health professionals. As our study primarily aimed to assess change over time for the total participants who viewed the film, this is not an unexpected limitation. Future studies would benefit from showing the film in a controlled setting where participants would watch the film without choosing to and having a larger number of participants, especially mental health professionals to participate. Fourth, this study examined stigma within a 2-week period after the film was shown. Future research on longer term benefits is needed. Finally, this study used a one group pre-test post-test to assess change in stigma before and after viewing a film on mental illness. This study design has limitations including unmeasured confounders due to data collection over time (i.e., another event could have changed stigma that happened at the same time as the film) and the fact that the participants may become familiar with the survey and thereby sensitized to the questions that may only allow for generalizability to those who participated in the first survey (Knapp, Citation2016). The reason a control group was not used in this study was because we wanted all people at the study sites to have access to view the film. Further, we are less concerned about some of the limitations inherent with pre-post designs as we completed the two surveys within a limited window of time to reduce the effect of other unmeasured confounders impacting the results.

6. Conclusion

The intervention which included a screening of the film, “Lift the Mask: Portraits of Life with Mental Illness”, and a panel discussion after the film was found to significantly reduce stigma related to mental health conditions among both people mental health professionals and those not working in the mental health profession. Mental health stigma is an important barrier to healthcare for many individuals, leaving people with mental health conditions without adequate treatment and feeling alone. Films that humanize mental health conditions have the power to reduce mental health stigma and should be considered as important tools to use in stigma reduction. By reducing stigma, people will begin to recognize mental health conditions as a common part of the human experience deserving of empathy and care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the study participants and film’s subjects, creators, and executive producers who developed the film, “Lift the Mask: Portraits of Life with Mental Illness”. Further, we would like to recognize the support from Emad Tantawy and Renee Wilk who supported the research project. This study was funded by the Quell Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kristin K. Sznajder

Kristin K. Sznajder is an Assistant Professor of Public Health Sciences at the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine. She holds a PhD in Epidemiology, a master’s degree in Global Health, and a bachelor’s degree in Psychology. Her research centers on the social determinants of health, with a focus on behavioral health outcomes.

Glen Coppersmith

Glen Coppersmith is the Chief Data Officer at SonderMind. Glen earned a bachelor’s degree in Computer Science and Cognitive Psychology, a master’s degree in Psycholinguistics, and a PhD in Neuroscience, He is recognized as a leader and pioneer in the space of mental health and data science.

Kevin M. Lynch

Kevin M. Lynch is the Founder and CEO of The Quell Foundation with a mission to reduce the number of suicides, overdoses, and the incarceration of people with a mental health condition. He holds a master’s degree in Health Policy and Administration and a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration graduating with summa cum laude honors.

References

- Ashford, R. D., Brown, A. M., McDaniel, J., & Curtis, B. (2019). Biased labels: An experimental study of language and stigma among individuals in recovery and health professionals. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(8), 1376–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1581221

- Bergamini, E., Demidenko, E., & Sargent, J. D. (2013). Trends in tobacco and alcohol brand placements in popular US movies, 1996 through 2009. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 634–639. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.393

- Brown, S. A., Evans, Y., Espenschade, K., & O’Connor, M. (2010). An examination of two brief stigma reduction strategies: Filmed personal contact and hallucination simulations. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(5), 494–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9309-1

- Carmichael, V., Adamson, G., Sitter, K. C., & Whitley, R. (2019). Media coverage of mental illness: A comparison of citizen journalism vs. professional journalism portrayals. Journal of Mental Health, 28(5), 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1608934

- Chan, J. Y., Mak, W. W., & Law, L. S. (2009). Combining education and video-based contact to reduce stigma of mental illness:“The same or not the same” anti-stigma program for secondary schools in Hong Kong. Social Science & Medicine, 68(8), 1521–1526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.016

- Charles, J. L., & Bentley, K. J. (2016). Stigma as an organizing framework for understanding the early history of community mental health and psychiatric social work. Social Work in Mental Health, 14(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2014.964448

- Chi, P., Li, X., Zhao, J., & Zhao, G. (2014). Vicious circle of perceived stigma, enacted stigma and depressive symptoms among children affected by HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS and Behavior, 18(6), 1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0649-z

- Connell, J., Brazier, J., O’Cathain, A., Lloyd-Jones, M., & Paisley, S. (2012). Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-138

- Coppersmith, G., & Kelly, E. (2014). Dynamic wordclouds and vennclouds for exploratory data analysis. Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, Baltimore, USA; Association for Computing Machinery, 22–29 https://aclanthology.org/W14-3103.pdf

- Corrigan, P. W., & Shapiro, J. R. (2010). Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.004

- Dubreucq, J., Plasse, J., & Franck, N. (2021). Self-stigma in serious mental illness: A systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(5), 1261–1287. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa181

- Fox, A. B., Earnshaw, V. A., Taverna, E. C., & Vogt, D. (2018). Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma and Health, 3(4), 348. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000104

- Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster.

- Goodwin, J., Saab, M. M., Dillon, C. B., Kilty, C., McCarthy, A., O’Brien, M., & Philpott, L. F. (2021). The use of film-based interventions in adolescent mental health education: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 137, 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.055

- Gronholm, P. C., Henderson, C., Deb, T., & Thornicroft, G. (2017). Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: The state of the art. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1341-9

- Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777–780. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

- Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014672

- Holmes, E. P., Corrigan, P. W., Williams, P., Canar, J., & Kubiak, M. A. (1999). Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 25(3), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033392

- Ikeme, C. (2012). The stigma of a mental illness label: Attitudes towards individuals with mental illness. University of Dayton.

- Ito-Jaeger, S., Perez Vallejos, E., Curran, T., Spors, V., Long, Y., Liguori, A., Warwick, M., Wilson, M., & Crawford, P. (2021). Digital video interventions and mental health literacy among young people: A scoping review. Journal of Mental Health, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1922642

- Janoušková, M., Tušková, E., Weissová, A., Trančík, P., Pasz, J., Evans-Lacko, S., & Winkler, P. (2017). Can video interventions be used to effectively destigmatize mental illness among young people? A systematic review. European Psychiatry, 41(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.09.008

- Kerby, J., Calton, T., Dimambro, B., Flood, C., & Glazebrook, C. (2008). Anti-stigma films and medical students’ attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatry: Randomised controlled trial. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32(9), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.107.017152

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., De Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., Haro, J. M., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Kawakami, N., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina Mora, M. E., Oakley Browne, M. A., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D. J., Adley Tsang, C. H., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., and DE Girolamo, G. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 168. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2174588/

- Kimmerle, J., & Cress, U. (2013). The effects of TV and film exposure on knowledge about and attitudes toward mental disorders. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(8), 931–943. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21581

- Klin, A., & Lemish, D. (2008). Mental disorders stigma in the media: Review of studies on production, content, and influences. Journal of Health Communication, 13(5), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802198813

- Knapp, T. R. (2016). Why is the one-group pretest–posttest design still used? (Vol. 25, SAGE Publications Sage CA.

- Lê Cook, B., Doksum, T., Chen, C.-N., Carle, A., & Alegría, M. (2013). The role of provider supply and organization in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care in the US. Social Science & Medicine, 84, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.006

- Lei, M., & Lomax, R. G. (2005). The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 12(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1201_1

- Link, B. G. (1985). The labeling perspective and its critics: A reformulation in the area of mental disorder. In eastern sociologial association meetings, Philadephia, PA.

- Link, B. G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review, 52(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095395

- Link, B. G., & Cullen, F. T. (1986). Contact with the mentally ill and perceptions of how dangerous they are. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 27(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136945

- Macpherson, S., & Warrender, D. (2018). Using film screenings to raise public awareness of mental health. Nursing Times, 114(7), 29–31. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/mental-health-nurses/using-film-screenings-to-raise-public-awareness-of-mental-health-18-06-2018/

- McKay, A. J., Negi, N. S., Murukutla, N., Laverty, A. A., Puri, P., Uttekar, B. V., Millett, C., & Mullin, S. (2020). Trends in tobacco, alcohol and branded fast-food imagery in Bollywood films, 1994-2013. PloS One, 15(5), e0230050. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230050

- Parcesepe, A. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(5), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z

- Quinn, N., Shulman, A., Knifton, L., & Byrne, P. (2011). The impact of a national mental health arts and film festival on stigma and recovery. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 123(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01573.x

- Riles, J. M., Funk, M., Miller, B., & Morrow, E. (2021). An inclination for intimacy. Depictions of Mental Health and Interpersonal Interaction in Popular Film. International Journal of Communication, 15, 21. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16653

- Rosenfield, S., & Mouzon, D. (2013). Gender and mental health. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 277–296). Springer Netherlands.

- Ross, A. M., Morgan, A. J., Jorm, A. F., & Reavley, N. J. (2019). A systematic review of the impact of media reports of severe mental illness on stigma and discrimination, and interventions that AIM to mitigate any adverse impact. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1608-9

- Rüsch, N., Brohan, E., Gabbidon, J., Thornicroft, G., & Clement, S. (2014). Stigma and disclosing one’s mental illness to family and friends. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(7), 1157–1160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0871-7

- Sheehan, L., Nieweglowski, K., & Corrigan, P. W. (2017). Structures and types of stigma The stigma of mental illness-end of the story?. Springer.

- Sims, J. M. (2010). A brief review of the Belmont report. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 29(4), 173–174. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181de9ec5

- Stuart, H. (2006). Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments. CNS Drugs, 20(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 national survey on drug use and health. (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR1PDFW090120.pdf.

- Tanaka, G., Ogawa, T., Inadomi, H., Kikuchi, Y., & Ohta, Y. (2003). Effects of an educational program on public attitudes towards mental illness. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 57(6), 595–602. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01173.x

- Winkler, P., Janoušková, M., Kožený, J., Pasz, J., Mladá, K., Weissová, A., Evans-Lacko, S., & Evans-Lacko, S. (2017). Short video interventions to reduce mental health stigma: A multi-centre randomised controlled trial in nursing high schools. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1549–1557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1449-y