Abstract

While many researchers have investigated the structural causative factors of ethnic conflict in Ghana, elite mobilisation as a cause of ethnic conflict in Ghana has received less academic attention. This study investigated the role of ethnic elites in the onset of ethnic conflicts within Bawku Traditional Area of Ghana in the context of the General Theory of Ethnic Conflict. A qualitative method, using a grounded theory perspective with a systematic design was adopted where structured interview guides were used to gather primary data from 30 participants. The data collected was analysed using inductive thematic analysis. It was found that ethnic elites from both the Kusasi and the Mamprusi tribes, amidst favourable political atmosphere, mobilised their people into violence interchangeably with changing political regimes. It was therefore, recommended that the outbidding process which allows for intense mobilisation be regulated and guarded from degenerating into inspiration for violence.

1. Introduction

Ethnicity is a state of belonging to a social group that share common tradition, culture, spoken language and ancestral history (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2019). Ethnic elite mobilisation, therefore, is a situation where members of an ethnic group are incited by the elites from the same group to engage in collective actions that are supposed to promote the wellbeing of the entire group (Bos et al., Citation2020). Many countries in Africa are made up of different ethnic groups. While this does not constitute a problem in itself, the anchoring of democracies in the new independent states of Africa exclusively along ethnic lines at the immediate post-independence era led to the polarisation of citizens along ethnic lines and so provided grounds for ethnic outbidding. In the outbidding process, ethnic elites mobilised members of their ethnic groups to demand greater shares of state resources including appointment into public offices. This led to competition over state resources and, many times, violent conflicts. For instance, elite politics was responsible for the conflict between the Hutu and the Tutsi ethnic groups in Rwanda which killed about 800000 people (Baldwin, Citation2019; Cheeseman et al., Citation2018; Mironko, Citation2017). In Congo, ethnic politics is responsible for the protracted clashes between the Herma and the Lendu ethnic groups who are considered descendants of an elder and younger brother and speak the same language but yet feel divided. The various rebel groups that fought against the governments of Emmanuel Doe between 1989 and 1996 and subsequently that of Charles Taylor between 2002 and 2003 were all clad in ethnic ropes (Amanor-Lartey, Citation2015; Twagiramungu et al., Citation2019). Ethnic politics in South Sudan resulted in the clash between the Dinka and Nuer tribes that killed many people and destroyed properties. It also explains the conflict between the Murle tribe and the Lou tribe of south Sudan (Yoshida, 2013). Such conflicts are ubiquitous within the continent and are fought mostly in the rural and peri-urban areas with devastating humanitarian consequences (Boone, Citation2017). What then are the escalatory factors of ethnic conflicts?

Ethnic conflicts have received huge academic attention as a good number of academics have investigated the phenomenon using different research approaches. Quantitative studies of ethnic conflict have identified varied independent influencing factors and varied escalatory dynamics of ethnic conflicts. Most of such studies single out structural factors like competition over land (Kuusaana & Bukari, Citation2015; Maher, Citation2019), resource distribution (Johannes et al., Citation2015; Morelli & Rohner, Citation2015; Zallé, Citation2019), ethnic domination (Harff & Gurr, Citation2018; Harkness, Citation2016; Ukiwo, Citation2003), state failure (Oucho, Citation2021; Stavenhagen, Citation2016) and deprivation (Meuleman et al., Citation2020; Taras & Ganguly, Citation2015) as the main drivers of ethnic conflicts. Some qualitative studies go beyond the structural factors to include agent-specific factors such as fear, hatred, honour, capabilities and opportunities (Bhavnani & Backer, Citation2000; Cederman et al., Citation2010; Dowd, Citation2015; Horowitz, Citation2000; Moritz, Citation2010; Warren & Troy, Citation2015) as the leading drivers of ethnic conflicts. Some researchers also tie ethnic conflicts to the narratives of autochthones- settlers dichotomy (Martell, Citation2019; Mees, Citation2019), historical injustices, patronage politics as well as ancient hatred (Amighetti & Nuti, Citation2015; Knop & Riles, Citation2016; Venugopal, Citation2018).

While the structural explanatory factors of ethnic conflict in Ghana have been well investigated, the extent to which these potentially escalatory factors are integrated and manipulated by ethnic elites to cause ethnic conflicts in the specific expanse of Bawku Traditional Area has not received adequate academic attention. This study relies on the General Theory of Ethnic Wars as posited by Tang (Citation2015) as an analytical framework to explore the role of ethnic elite in the Kusassi-Mamprusi conflict in the Bawku Traditional Area of Northern Ghana. The study investigated the activities of ethnic elites in the Kussasu-Mamprusi conflict starting from the colonial period, through the immediate post-independent era to the present day while indicating the effect of different types of leadership on the fate of ethnic mobilisations in the Bawku Traditional Area.

2. Theoretical Framework

As indicated earlier, this study relies on the General Theory of Ethnic Wars as posited by Tang (Citation2015) as an analytical framework. The theory argues that structural and agent-specific escalatory factors of ethnic conflicts so identified by researchers, in their inertia, do not detect the contours of ethnic conflict unless pollinated by ethnic external agents using varied mechanisms. It further posits that there is no single factor that explains conflict but a combination of factors and mechanisms interact to produce social outcomes including ethnic conflicts. Tang (Citation2015) further condensed all the structural and agent-specific factors such as resource scarcity, state failure, weak States, competition over lands, deprivation, domination, hatred and rage that researchers had earlier identified as explaining ethnic conflict into four major components which he called “master drivers” of ethnic conflict. He argued that none of these influence ethnic conflict independently. Instead, they interact with each other and with other mechanisms to predict the onset of ethnic conflict. Tang (Citation2015) understands mechanisms as elements that drive changes or maintain the status quo in a social system. According to him, mechanisms interact with factors to drive changes in a social system including conflict.

Earlier, Horowitz (Citation2000) expressed a similar idea. He separated the immediate triggers of ethnic conflicts from the underlying triggers of ethnic conflict although he did not provide a nexus that the two interact to predict ethnic conflict. Collins (Citation2012) also identified the emotions of hatred, fear and anger as the immediate triggers of conflict behaviours, and political and ancestral history of war as the underlying causes. However, he did not indicate how the two might be integrated and complementary in explaining ethnic conflict. He also failed to indicate how these interact and are acted upon by external forces to explain conflict. Kaufman (2001) also argued that ancient hatred, State weakness, economic rivalry and ethnic domination do not explain ethnic conflict alone. He identified two main causative factors of ethnic conflict: instrumentalism and security dilemma. He argued that some people mobilise their ethnic groups along the lines of parochial interest to pursue individual or common goals. He further argued that ethnic groups take up arms against others or in self-defence for reasons of security. The collapse or weaknesses of nascent States in Africa have created anxieties about security among groups who are continuously engaged in premeditated actions to ensure the security of their members. Sometimes, such actions are misinterpreted by other groups as preparations to attack and annihilate these groups. This triggers reciprocal gestures on a larger scale, and thus, ethnic conflict arises.

The two positions of Kaufman (2001) are now referred to as “the instrumentalists” and “security dilemma” approaches, respectively, in conflict studies circles. Although Kaufman (2011) provided a general understanding of how structural factors alone are inadequate to explain ethnic conflicts, he failed to touch on how other conditions are integrated and manipulated by ethnic elites in explaining conflict. Petersen (Citation2001) attempted to integrate various factors that predict ethnic conflicts by arguing that ethnic conflicts are caused by symbolic values as much as they are caused by material variables. A manipulation of symbolic values arouses emotions of hate, anger and rage. These, he says, trigger conflict. He further argues that often individuals are motivated by various factors to participate in ethnic violence and so the causative factors of this violence are not to be taken in isolation, they integrate, sophisticate and conflagrate into ethnic conflicts of varied scales and dimensions. While he succeeded in integrating the escalatory factors of ethnic conflict, he failed to touch on the role of ethnic elite in mobilising their people along near irreparable antagonistic splits.

3. The Historical Development of the Kusasi-Mamprusi Conflict in Bawku

Unlike many ethnic conflicts in Ghana, which are fought between families and groups with the same ancestral history, the Mamprusis and Kussasis are separate ethnic groups with no common ancestral history. They speak different languages and belong to different religions. There are very few cases of intermarriages due to the distinctiveness in their religions as well as the protracted conflict between the two groups. According to the oral tradition which has been adopted by many contemporary Ghanaian historians, the Mamprusis were part of the Mole-Dagbani group that migrated from present-day Nigeria in the 11th century to settle in what was then the Mali Empire. By the 13th Century, they moved from Mali into present-day northern conquering the indigenous populations of the north, including the Kussasis, Frafras, Konkombas and Bimobas, and founded the Gbewa Kingdom at Pusiga, a few kilometres from the town of Bawku (Plange & Plange, Citation2007). Although the Gbewa kingdom was later dissolved due to succession differences between the three grandsons of Gbewa, the Mamprugu kingdom that emerged from this disintegartion remained in control of most communities and villages of upper eastern Ghana, including Bawku, until the arrival of colonists in 1902.

The colonists used a method called indirect rule in their African colonies including Ghana. This method of administration relied on existing traditional political systems to administer colonies while introducing such colonies to the British system of political administration. Such arrangements saw traditional African chiefs co-opted as administrators of the colonies albeit earlier resistance (Naseemullah & Staniland, Citation2016). Ghana then referred to as the Gold Coast is a country on the West African coast which was known for its vast gold and other mineral deposits. This made it a trading hub during the Trans Saharan trade with the Maghreb Arab Berbers. Ghana subsequently established trade relations with the Europeans in the late 15th century (Dueppen, Citation2016) and traded mainly in gold and ivory. The colonisation of Ghana started when it was made a Chartered Company Territory of the African Company of Merchants along the coast in the 18th century (Mulich, Citation2018). In 1844, the British took firm control of the then Gold Coast (Plange & Plange, Citation2007). During this time, the communities were integrated into one country and placed under British rule. They did this through the existing traditional political structures headed by the chiefs. The chiefs, while controlling local affairs, had to do so within the boundaries set by the colonists. Chiefs who tried to be recalcitrant were met with stronger force, as exemplified by the deposition and subsequent banishment of the Cape Coast king, Aggrey (Plange & Plange, Citation2007). Through the Native Jurisdiction Ordinance, the traditional judicial systems were also overhauled to suit the British judicial structure and more adjudicative powers were given to the governor and his district commissioners.

In 1902, the colonial state was extended to Northern Ghana (Mulich, Citation2018). The British had earlier contested this area with the French and Germans, but through unsolicited protective treaties with the northern chiefs, they managed to get hold of almost all of it. Although the Northern Protectorate was administered through indirect rule, the colonists started up with a Military rule which saw the establishment of a military post at Gambaga after the Mamprusi chiefs began to agitate against the destabilisation of existing traditional political structures (Plange & Plange, Citation2007). The colonists’ experience with the Ashanti Kings in the South would have probably informed this approach. The Military were later replaced by a Constabulary force to reduce administration costs. This again proved effective for over 30 years (Nyaaba & Bob-Milliar, Citation2019). When they had gained full control of the area, they then began to use the existing political structures to draw loyalist chiefs into the administration of the area. Although the communities were allowed to elect chiefs, the District Commissioners were empowered to accept or reject elected chiefs from the north (Soeters, Citation2012). They were also responsible for overseeing the election of local chiefs. It was within this context that contestations over chieftaincy in Bawku started.

The Indirect Rule system saw the rise of Kings in Bawku district even in Kusasi-dominated areas. Earlier, a Mamprusi district was created in the Mamprugu Traditional Area and was headed by the Nayiri; the Paramount Chief of Mamprugu. Bawku district was created subsequently. This district was made up of Mamprusis and Kussasis but the Kusasis outnumbered the Mamprusis (Lund, Citation2003). Although Bawku district also had canton chiefs, the activities of such chiefs were supervised by the Nayiri of Mamprugu as they were also “enskinned” by him. In Northern Ghana, the process of installing a chief is called “enskinment”. Subsequently, there was a need for a higher chief in Bawku that will supervise the activities of the canton chiefs. Wuni Brugri Saa, a Mamprusi was made a Bawkunaba (Bawku chief). This was the beginning of grievances between the two tribes. The appointment of a Mamprusi to rule over a Kussasi dominated Bawku did not go well with most of the Kussasi Canton chiefs. The Bawkunaba who was a Mamprusi was placed above all other Canton Chiefs in Bawku.

The Kusasi chiefs were unhappy with the arrangement but had to accede because of the prevailing force at that time. An opportunity, however, presented itself for them to push back against this arrangement when Nkrumah, in the build up to the 1957 elections, aligned with the Kusasi and Frafra youths, soliciting for their votes at the general elections. They did give him their support and he eventually won the elections. Once he did win, the Kusasis, emboldened by his victory, moved to change the traditional political arrangement in Bawku. They installed Abugrago Azoka immediately after Wuni Bugri Saa passed away. This was contrary to the customary arrangement for chieftaincy successions in Bawku. The funeral of the late chief should have been performed first after which the Nayiri of Mamprugu would “enskin” the succeeding chief. The resolve of the Kusasis to set aside the hitherto prevailing customary arrangement eventually led in 1957 to the first clash of the two ethnic groups. A Commission of Inquiry that was set up to look into the conflict later ruled that the Kusasis were forced into the earlier chieftaincy arrangements and that the disrespect and inhumane treatment meted out to them was in sharp contradiction with the tenets of modern states. Abugrago was later promoted to be a Paramount Chief, making him equal in status to the Nayiri, the Paramount Chief of Mamprugu Kingdom.

Nkrumah was overthrown in 1966 by the National Liberation Council (NLC) led by Colonel Afrifa. Afrifa later handed over to Busia in 1969 when the latter was elected a Prime Minister. Under the new regime, prominent Mamprusis from Bawku were appointed to key positions in government: Adam Amande was made a Deputy State Minister while Imoro Salifu was made a Regional Minister (Gasu, Citation2020). In Ghana, a Regional Minister represents the President in a particular geographical area deliberately carved for administrative purposes. They therefore had the leverage to lobby for the reversal of the earlier ruling made by the Commission of Inquiry that was set up during the Nkrumah era. The duo successfully pushed for the removal of Abugurago Azoka through the Chieftaincy Amendment Decree of 1966 and had Prince Adams Azangbeo installed as the legitimate Bawkunaba (Government of Ghana, 1966).

In 1979, there was yet another change in government. Jerry John Rawlings forcefully removed Hilla Liman as the president and took over the affairs of the country. He later formed the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC). Most of the PNDC members were Nkrumah sympathisers. The Kusasis saw this as yet another opportunity to claim back the Bawku throne. Led by a staunch supporter and lawyer, John Ndebugre, the Kusasis pushed for the withdrawal of the 1966 decree which “dis-enskinned” Abugrago Azoka with his 18 divisional chiefs. As expected, this was done. Even though Abugrago Azoka died three months before the reversal, he was re-enskinned posthumously by the Chieftaincy Restoration Law of 1983. His son, Abugrago Azoka II succeeded him (Government of Ghana, 1983). This change triggered another clash in 1983.

The PNDC metamorphosed into the National Democratic Congress (NDC) at the return of democracy in 1992 from the military junta, meanwhile the Bawkunaba remained with the Kusasis. Bawku had earlier been divided into Bawku East and Bawku West, with Bawku and Zebila as their respective administrative capitals (Gasu, Citation2020). In the build-up to the 2000 elections, Cletus Apul Avoka who later became a Member of Parliament for Zebila Constituency announced that Bawku West District Assembly had changed the name of the district to Kusasi Toende and Bawku East was to be changed to Kusasi Agolle; the respective names the towns were known as prior to colonisation. This attracted a response from one Rahaman Gumah, of the Mamprusi elite. Tension again built up but was repressed by the presence of heavy Military personnel (Lund, Citation2003).

General elections were held in 2000 and were fiercely contested between the National Democratic Party (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). The NPP candidate, John Agyekum Kufuor eventually won the elections to the excitement of the Mamprusis and the anxiety of the Kusasis (Gasu, Citation2020). As is always the case, Kufuor started to make appointments. Mahami Salifu, a staunch Mamprusi convert to NPP, was made the Upper East Regional Minister. A District Chief Executive (DCE) was also to be appointed. The constitution, however, requires that such appointments must be confirmed by the members of the district assembly through voting (Agyeman, Citation2021). Rahaman Gumah was nominated by the president but failed to get the approval of the assembly members. He could not get even the 50% that was required for him to be re-nominated (Lund, Citation2003). Bawku had no DCE. The president then made Mahami Salifu Acting-DCE in addition to his post as a regional Minister. Mahami Salifu, in turn delegated that power to Rahaman Gumah who had earlier failed to get a vote of confidence from the Assembly members (Mahami, 2001). This was met with strong resistance from the Kusasi dominated assembly members. Tensions between the Kusasis and the Mamprusis grew to a very serious level. It found an outlet in the market. An argument between two women about the US invasion of Afghanistan was enough to trigger a violent clash in 2001 (Longi, Citation2014).

There was relative peace since 2003 until 2007, then 2008, when the groups rose against each other again. The State was able to restore calm through curfews and bans on motor cycle use (Adonteng-Kissi et al., Citation2019). From 2008, there was relative calm once more until an academic presentation in 2021 by Professor Akeya Agbango, who is of Kusasi lineage, ignited tensions between the two ethnic groups yet again. Each group organised press conferences, issuing warnings and declaring readiness for war. This led to a clash on 24 January 2022 and, as this article is being crafted, Bawku has been placed under a dusk to dawn curfew. A police officer and two military officers were shot to dead in separate attacks. The situation in Bawku is still volatile.

4. Method

4.1. The study Area

The study was conducted in “Bawku Traditional Area” which the Kusasi group prefer to call Kusaug Traditional Area. The Traditional Area comprises of six administrative districts: Bawku East, Bawku West, Binduri, Pusiga, Garu, Tempane (G.S.S, 2021). Bawku Township is the administrative centre for Bawku East as well as the commercial nerve centre of the three districts. The Traditional Area is headed by a Bawkunaba whom the Kusasi prefer to call a Zugrana (Lund, Citation2003).While the Kusasis are believed to be the first occupiers of the area, modern history indicates that the Mole-Dagbon people who consists of Dagombas, Mamprusis and Nanumbas, migrated from Zamfara in Northern Nigeria and, under the leadership of Naa Gbewa, invaded the northern territories of Ghana where they captured all the acephalous tribes which inhabited the area including the Kusasis of Bawku to create a Mole-Dagbon Kingdom with its capital at Pusiga, near Bawku Township (Longi, Citation2014; Lund, Citation2003; Bukari,Citation2013). The Kusasis speak Kusaal while the Mamprusis speak Mamprusi. The two languages are nearly mutually intelligible as they both originated from the Gur language which is widely spoken in the Upper East region. While the Kusasis largely practice Christianity as a religion, most of the Mamprusis adhere to Islam.

Bawku became a trading centre as far back as the days of the Trans Saharan Trade. These attracted many traders from the then Western Sudanese States into Bawku central town. The ethnic composition of Bawku became increasingly cosmopolitan as traders moved in and has remained so to date. Bawku, therefore, is comprised of several ethnic groups such as Hausa, Moshi, Busanga, Asante, Frafra, Mamprusi and Kusasi (Bukari et al., Citation2021). The Kusasis, however claim to be the main indigenes of Bawku, a claim which is fiercely opposed by the Mamprusis. According to the 2021 Population and Housing Census, the Kusasi ethnic group are the majority in the traditional area (41.2%) followed by Mamprusi (34.1%) and Moshi (15%; G.S.S, 2021). In both ethnic groups, there are more women than men. Of the 41.2% Kusasis in the traditional area 21.2% are female while 20% are male meanwhile, of the 34.1% Mamprusis, 18.3 are females while 16.1% are males. In terms of age, Bawku Traditional Area has a youthful population as 67.1% of the entire population is made up of people who are aged between 15 and 45 (G.S.S, 2021)

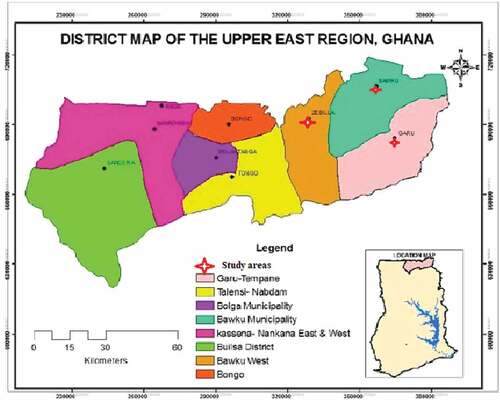

While Bawku Township conducts strong commercial activities, the majority of the people within the traditional area who reside outside the Township depend on rain-fed subsistent farming. Overall, 72.2% of the people of the traditional area depend on agriculture, 13% on trading, 10% on service provision and 5.8% work in various state departments within the traditional area (G.S.S, 2021). indicates the map of the study area and the communities that data was gathered from

4.2. Data Collection Procedure

The study adopted a qualitative approach using an exploratory design to investigate the role of ethnic elite mobilisation in the protracted Kusasi-Mamprusi conflict. The role of elite mobilisation cannot be subjected to quantitative measurement since it has no defined dimensions. To fully understand how ethnic elites mobilise politics and violence almost exclusively along ethnic contours requires a deep interaction with participants. The adoption of a qualitative approach, therefore, provided an opportunity for the researchers to conduct interviews and probe for further details that revealed all the dimensions of the ethnic mobilisation and manipulation processes (Saunders & Bezzina, Citation2015). The study recruited chiefs and opinion leaders within the Bawku Traditional areas as participants. This group was of particular interest to the researchers because they had in-depth knowledge about chieftaincy issues within the traditional area. Thirty of them were selected using Expert Purposive Sampling technique for personal interviews. The interview guides were structured so as to provide a focus on the main issues that answered the research questions as shown in

Table 1. Interview guide

Although 30 participants were selected for the interview, only 18 of them were actually interviewed. This is because it got to a point where participants were reporting the same things with no additional information. The researchers, therefore, considered this as a case of data saturation and decided to stop the interviews after the eighteenth person was interviewed. The profile of the respondents is shown in .

Table 2. List of informants

The interview with each respondent lasted for at least 30 minutes as indicated in . In addition to these, the researchers obtained and reviewed archival documents about the Bawku chieftaincy conflict from the Public Records and Archives Administration Department (PRAAD) in Tamale. Collected data were analysed using themes. First of all the results of the interviews were transcribed by two of the authors and shared among all the authors for text familiarisation, edits and reviews. After that each researcher was asked to develop codes, subthemes and main themes from the transcribed data. Emerging themes from the codes were identified, categorised and named by individual researchers. To ensure consistency, reliability and relevance, after the individual coding and theming process, the identified themes were compared.

Codes from all three researchers were almost the same except for one who had identified three other codes. This was later rectified as it was realised that the difference was caused by some ambiguity in the language of some of the respondents. These codes were then organised into basic themes by the researchers as a team and later combined into organising themes as presented in . The results of the data were interpreted base on the identified themes in reference to the objectives of the study.

Table 3. Participants understanding of the escalatory factors of kusasi-mamprusi conflict

5. Findings

5.1. Colonial Legacy

Most of the participants (90%) blamed the conflict on the activities of the British Colonialists which were carried out under the stewardship of J.G Syme, the then District Commissioner for Bawku. They said the decision processes that led to the appointment of the first Bawkunaba set the stage for the conflict that Bawku has been experiencing since independence. This was put forth by respondent B2 as this:

”what you see here today is the legacy of colonialism. They merged two distinct ethnic groups together, how do they expect them to understand each other?”

Another respondent B9 also explained:

“This conflict started when the colonial masters decided to place the Bawkunaba above all the other divisional chiefs in Bawkuland. Most of the chiefs were Kussasis, so placing them under the suzerainty of a Mamprusi chief was something that was not sustainable”.

An empirical study by Longi (Citation2014) on this shows similar findings. The study of Agyeman (Citation2021) also shows similar findings but concludes that such arrangements were administratively necessitated and should have been rectified 50 years after colonialism. A review of the archival documents shows that both Kusasi and the Mamprusi tribes occupied the North-Eastern territories of Ghana as far back as the late 15th Century (Syme, 1917). The coexistence of these two groups within this geographical demarcation predates colonialism. While the Mamprusi ethnic group had a centralised administrative system characterised by a High King and divisional chiefs as well as village heads and earth priests (Tindanaas), the Kusasi were never centralised but instead were organised along family lines with symbolic family heads who were the eldest of the family but had neither power to command nor punish; an arrangement archetypal to what anthropologists describe as acephalous societies (Syme, Citation1931). Jones (Citation1918) also reports that there were evidences of pre-colonial relationship between the two ethnic groups as seen in the resolve of the Nayiri Na Atabiya (1690–1741) to offer military assistance to the Kusasi people when they were being attacked by the Bissa people who occupy parts of modern day Burkina Faso. The Military established posts at Bawku, Sinnabaga, Binduri, Teshi, Tanga and Woriknambo.

Participants who were either Kusasis or Frafras had a common narrative that while the Kusasis had no system of Kinship and were not interested in it, the Mamprusis, who stayed with them, were used to it and appreciated the value of Kingship. Some of the Mamprusis in Bawku appointed themselves kings and went to the Nayiri to be “enskinned” (installed) but these had no real power over the people that inhabited Bawku and were recognised only among the Mamprusis who were resident in Bawku. This practice continued until the 1900 when colonisation destabilised traditional political arrangements in Bawku. However, participants who were either Mamprusis or Moshi disagreed in part to this narrative and had a common understanding that the Nayiri installed chiefs were recognised by all as such and controlled everyone within their area of jurisprudence.

The results of the interviews also show that the Kusasi/Frafra participants had a common understanding that the first Bawkunaba forced the Kusasi people to pay extra taxes, supply-free labour and present installation fees to the Bawkunaba to be installed as divisional chiefs and that representation at the Local Council was also dominated by the Mamprusis. Their narratives further suggested that the Mamprusi dominated Local Council also denied scholarships to Kusasi students but instead offered them to the Mamprusi students. This claim was, however, denied, in part, by the participants who were Mamprusis. They had a common explanation suggesting that paying taxes and working for a king was a normal practice in Mamprugu Kingdom. Jones (Citation1918), reports that the Kusasi people understood their treatment as an act of domination, subjugation and oppression and were determined to break the hegemony. The Mamprusis, on the other hand, agreed with the arrangement and were bent on maintaining it. The resistance of the Kusasi to Mamprusi domination and the persistence of the Mamprusis to maintain the status quo partly explain the onset of the intractable Kusasi-Mamprusi Conflict in Bawku.

5.2. Political Opportunism

All the participants expressed the view that politicians have not been committed to resolving the conflict but instead have been keen on reaping political benefits from the antagonistic relationship between the Kusasis and the Mamprusi ethnic groups in Bawku. This was captured by respondent B5 as this:

“Right from the days of Kwame Nkrumah till date, politicians have manipulated us to reap political gains. Nkrumah started it all. He mobilised political support through the Frafra and Kusasi youths. He created a Kusasi Traditional Area out of the Mamprugu Traditional Area and renamed Bawku district to Kusasi district. His Commission of Inquiry also upheld the illegal installation of Abugrago Azoka … … … this was the onset of the conflict”

This indicates that Nkrumah, with intent, threw his weight on the side of the Kusasis so as to win their votes during the 1956 elections. The results of the interviews indicate that this narrative is common among the Mamprusis but the Kusasis rather see the action of Nkrumah as the right thing that was done to liberate them from Mamprusi hegemony. This was implicit in the response of respondent B11 when he says:

“Nkrumah wanted the right things to be done. He separated the two tribes so that there would be no conflict. How could a minority tribe rule over a majority tribe in their own ancestral land? This is same as ethnic invasion. The Afrifa/Busia regime is responsible for all this mess. Dividing districts and kingdoms for easy administrative purposes is a characteristic of every modern state. Kusasi Traditional Area was carved out of Mamprugu, and that is in line with modern practice. Even the British granted Ghana independence so what is wrong with creating an autonomous Kingdom out of an existing one? They reversed Nkrumah’s decisions out of mere hatred for Nkrumah but not for any superior reasons. See the impact of their actions today?”

During the interviews, three of the participants (B14, B1 and B5) argued that even Rawlings and Kufuor explored the friction between the two tribes for political gains. They had a common narrative which suggested that while Rawlings was sure of winning elections, he was also sure that the Mamprusis in Bawku supported the Dankwa/Busia traditions which meant that they would surely vote against him. So he threw his weight behind the Kusasi. This was captured by respondent B1 as this:

“Rawlings knew he was going to win, but he can’t be exonerated from this political opportunism I am talking about. He was the Chairman of PNDC who returned the Bawkunaba seat to the Kusasis. He knew the Mamprusis would surely vote against him and so to bolster his victory, he was in bed with the Kusasis to the best of my knowledge”

Respondent B9; however, had a contrary opinion. He expressed it thus:

“I believe all the politicians did what they did in Bawku because they needed votes with the exception of Rawlings. Rawlings, as the Chairman of the PNDC, forced the Kusasis to returned lands that they confiscated from the Mamprusis and banned the Kusasi Youth Association which was a very powerful mobilising tool for the Kusasis. He further suspended John Ndebugre, one of the strongest Mobilisers of the Kusasis, as the District Secretary just to ensure that there was peace in Bawku. So, to me, he was the only leader who acted in the interest of peace. The rest were opportunists”

Similar studies on the intractable chieftaincy conflict between the Andani and Abudu families in the Dagbong Kingdom of the north, which led to the assassination of the paramount chief of Dabong in 2002, also suggests that politicians exploited the differences between the two families to gain political support and win votes in elections (Adu-Amankwaah, 2008; Bukari et al., Citation2021; Tonah, Citation2012). They found that the Abdu family favoured the National Patriotic Party (NPP), while the Andani family supported the National Democratic Party (NDP) based on the promises that were made to them regarding the conflict. These are the two main political parties that have ruled Ghana since the Fourth Republic. In a related study, Tonah and Anamzoya (2016) found evidence of political opportunism in the chieftaincy conflict that killed over 166 people and caused millions of dollars in property damage to rural communities in Northern Ghana. Although Ibrahim et al (Citation2022) denied any element of political opportunism in the Bole chieftaincy conflict in northern Ghana, they acknowledged, at the end of their study, that members of the feuding families had different political affiliations as demonstrated in their voting patterns but could not correlate this directly to political opportunism. Situations were politicians take advantage of conflictual relationships to win one party to their side has been demonstrated in this study and many other studies. This situation demonstrates irresponsibility on the part of those who are mandated to protect the lives and properties of citizen.

5.3. Elite Mobilisation

The interview data gathered on this construct indicated that whenever the Kusasi-Mamprusi conflict escalated, there were influential people from both ethnic groups that had egged on their members during intra-group interactions. From the Kusasi side, the first mobilisation towards the “emancipation” of Kusasis from the Mamprusis was led by Awani Akuguri, who championed the cause of the group and triggered the installation of a Kusasi, Bawkunaba Abugragu Azoka, even before the Nayiri settled on Yerimiah Mahamah. John Ndebugri was also said to be instrumental in this, especially during the PNDC era. He was the one who challenged the legitimacy of the re-enskinment of Yerimah Mahama through a legal process by a petition to the PNDC government. His song at the annual Kusasi feast of Samanpiid also sparked outrage. It was revealed that the likes of Cletus Apul Avoka and Agbongo Akeya also played prominent roles in the build up to the 2001 clash. At every point of the mobilisation process, the elites inflamed emotions by constantly referring to the Kusasi heritage, their land and the need to assert their unique cultural, political and ethnic identities which the Mamprusis were seeking to destroy. Respondent B12 was emphatic about this:

“While the Kusasis think they are at war with the Mamprusis, the hidden truth is that their people whom they so revere next to their gods are misleading them for their parochial interests. Awani Akuguri who mobilised the installation of Abugrago Azoko became the first Member of Parliament for Zebila constituency, Ndebugri is a successful politician. He has held various political positions; you can visit the archives for details. Avoka later became a Member of Parliament. To me I feel these individuals ride on the sentiments of their people to heighten emotions that explode at the least provocation but beneath this outbidding are their hidden interests”.

The activities of ethnic elites were also reported from the Mamprusi side. Adam Amande and Salifu Imoro were reported to have spearheaded the agitations for the removal of Abugragu Azoka when the Nkrumah government was overthrown. They demanded the reversal of the 1957 ruling and a further reversal of the status of the Bawkunaba as a paramount chief. The names of Salifu Mahami and Rahaman Gumah also appeared prominently in the interviews as some of the Mamprusi elites who offered strong motivations through rigorous outbidding activities which fuelled and sustained the Kusasi-Mamprusi conflict in Bawku traditional area. Interestingly, all of them also earned enviable government appointments. Adam Amande was made a Deputy State Minister, Salifu Mahami became a Regional Minister before he died and Rahaman Gurmah was made a DCE.

It was further revealed that the Mamprusi elites constantly refer to the oral narratives of a powerful Mole-Dagbon army which came from Burkina Faso and conquered the acephalous societies of modern day Northern Ghana to establish a Mole-Dagbon Kingdom in Pusiga near Bawku, not just to lay claims to Bawku land but, to further inflame emotions and heighten resistance to any change in the traditional political order existing prior to independence. Such narratives resonate very well with the majority of the Mamprusis and make them even more resolute to die fighting for their land. Respondent B17 emphasised this point:

“If we hadn’t the likes of Amande Adams, Salifu Imoro, Salifu Mahami and Rahaman Guma, the conflict would have been less destructive and possibly ended by now. I see them as being very manipulative. They rely on ancient myths to create a sense of entitlement among the Maprusis who are resident in Bawku and it becomes very difficult for them to think objectively. This is why we are at this stage today”

The study further found that ethnic elite mobilisation was a major influencing factor in the onset of the Kusasi-Mamprusi conflict. While emotions, interest, capability and opportunity drive conflicts, they need to be integrated and the people also need to be mobilised before ethnic conflict can take place. This means that these variables enable ethnic conflicts but do not trigger them. These conditions on their own may not ignite ethnic conflicts. They require agents to act on them. The role of ethnic elite in manipulating these conditions to ignite and sustain ethnic conflicts was demonstrated clearly in the Kusasi-Mamprusi conflict. If the likes of John Ndebugri, Cletus Apul Avoka, Mahami Salifu and Rahaman Guma had been absent, there would probably not have been a Kusasi-Manprusi conflict. The 1983 violent confrontation was started after Ndebugri composed a song at the Samanpiid celebration which the Mamprusi interpreted as ridiculing them because Ibrahim Adams had been removed and Abugrago Azoka II re-enskinned as the Bawkwunaba.

Elite mobilisation may occur by two routes: legal or violent. Ethnic elites may employ the necessary legal procedures to demand equality, redistribution of resources, access to bureaucracy, power or natural resources. They may also mobilise people along ethnic lines by instigating and sustaining conflict-encouraging behaviours. Both the Kusasi and the Mamprusi elites in Bawku use combinations of these routes interchangeably. At the time the legitimacy of Yerimiah Mahama as a Bawkunaba was being challenged by lawyer Ndebugri and his legal team, the Kusasi Youth Association invaded the office of the Bawku Traditional Council (Gasu, Citation2020; Longi, Citation2014; Lund, Citation2003, Citation2006). Elite mobilisation is, therefore, a very strong driver for ethnic conflict as seen in the case of the Kusasi/Mamprusi ethnic conflict. The people are led to believe that they have been subjugated, oppressed, denied justice or denied access to their rights. This ignites emotions of anger, resentment and rage. When there is capacity and opportunity, conflict breaks out.

In ethnic mobilisation, outbidding is one of the major machinations that ethnic elites employ. As also found by Harff and Gurr (Citation2018) elites from both sides of the divide mobilised their members by creating a divisive atmosphere such as making members believe that their ethnic group is being massively discriminated against, enslaved or is facing possible annihilation if actions were not taken. The other groups are portrayed as being inherently hostile, dangerous, wicked and posing immediate threats. These elites also fanned existing resentment by portraying the other group as oppressive and officious. They also attribute the unfavourable living conditions of their people as the work of the other group. They remind their people about past atrocities committed by the other group against their people, and these come to believe that the other group is evil minded, inhumane and wicked in contrast to themselves, who are peaceful, glorious and loving. Inter-group interactions are often delineated within the narratives of a we/they dichotomy. By the time all this is done, the elite has won the massive support of almost everyone. This is exactly what happened in Bawku within both Kusasi and Mamprusi ethnic groups.

Tang (Citation2015) identified two groups of elite: moderate and radical. He finds that the moderate elites hardly get a voice or support at in-group interactions’. The chauvinistic and hawkish elites always carry the day. After the radical elites are done mobilising the people, they then look for a trigger. This could be by sending or inciting thugs to inflict violence upon the other group as can be seen in the invasion of the Bawku Traditional Council by the Kusasi Youth Association or the killing of traders in Bawku Central Market. This in turn attracts reprisal attacks and therefore creates a conflict situation.

6. Conclusion

This article explored the role of ethnic elite in ethnic conflicts using the Kusasi-Mamprusi conflict in Bawku Traditional Area as a case study. While many researchers have identified a number of independent factors such as struggle over resources, inequality, domination, discrimination, deprivation, anger, ancient and modern hatreds, instrumentalism, weaken States, failed States, fear, anger, resentment and rage as the causative factors of ethnic conflict, they failed to investigate the role of ethnic elites in mobilising their people within such enabling conditions of ethnic conflict. The grouping of these factors into broad categories only simplifies the task of identification but still does not explain the role of ethnic elite in ethnic conflicts. The integration of these factors acting in unity and not in isolation helps to explain the complexity of ethnic conflicts but still does not explain how these are enabled by ethnic elites. This study revealed that these factors are manipulated by radical ethnic elites in the course of their mobilisation process as demonstrated in the protracted conflict between the Kusasis and the Maprusis in Bawku Traditional Area of Ghana. The mobilisation process has been particularly successful because the traditional authorities who are supposed to resolve the conflict in the traditional areas of Bawku have been weakened by the ongoing debate over which ethnic group sits on the skin of Bawku Naba. The central authority, which is supposed to work with the traditional authority to manage the conflict, often uses it to gain political advantage. Without an effective traditional authority and a committed central authority, the hawkish behaviours of the ethnic elites will continue to make the conflict in Bawku more intractable.

7. Practical Implications

This study revealed that elite mobilisation is crucial to the onset of ethnic conflicts. This means that the National House of Chiefs, which is constitutionally mandated to resolve traditional disputes revolving around chieftaincy in Ghana, could engage the moderate elites among the Kusasis and the Mamprusis and empower them to remobilise and educate their people along positive lines, putting across their grievances and dissatisfaction and having them addressed without resorting to violence.

Again, the National Security apparatus may devise tactical means of identifying and engaging the hawkish ethnic elites from both groups, so that they may be guided and sensitised to embrace peaceful means to express their concerns. This may reduce the extent to which sentiments are manipulated and people inflamed to attack out-group members.

This study also found that various factors combine to cause ethnic conflict. Guided by this, the Upper East Regional House of Chiefs may adopt an integrated and inclusive approach to resolving the Kusasi-Mamprusi ethnic conflict in Bawku such as combining indigenous and modern conflict resolution mechanisms rather than rely on the usual approach of Military deployment and imposition of curfews.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the undying support of Persius Aaliebemwin Yabelang who assisted by proof reading the work and making relevant suggestions which improved the quality of the study. We also acknowledge all participants who contributed immensely in providing data for the study. We are equally indebted to the anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions have enriched the quality of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tobias Tseer

Tobias Tseer Mr Tseer Tobias teaches Organisational Conflict and Feminism at the Simon Diedong Dombo University for Business and Integrated Development Studies in Wa, Northern Ghana. His research interests are in gender and conflict studies. He has published extensively on Ethnic Conflicts in Ghana. His recent article was published in the International Annals of Criminology by Cambridge University Press. He is open to research collaboration at any level within his area of research interest.

Mohammed Sulemana

Mohammed Sulemana Professor Mohamed Suleimana is an experienced researcher and the Foundation Dean of the School of Public Policy and Governance at Simon Diedong Dombo University Business and Integrated Development Studies. He has published numerous articles on conflict, governance and housing policy. He is willing to collaborate on research projects within his area of research interest.

References

- Adonteng-Kissi, O., Adonteng-Kissi, B., Jibril, M. K., & Osei, S. K. (2019). Communal conflict versus education: Experiences of stakeholders in Ghana’s Bawku conflict. International Journal of Educational Development, 65, 68–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.08.002

- Agyeman, L. O. (2021). Understanding the causes and dynamics of conflicts in Ghana: Insights from Bawku Traditional Area. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 18(2), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v18i2.5

- Amanor-Lartey, E. (2015). A historical overview of ecowas intervention in sub-regional conflicts: the case of sierra leone. Somaliland Journal of African Studies, 2(1), 22–47. https://www.researchLartey/publication/27335owas_Intervention_In_Sub-Region

- Amighetti, S., & Nuti, A. (2015). Towards a shared redress: Achieving historical justice through democratic deliberation. Journal of Political Philosophy, 23(4), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12059

- Baldwin, G. (2019). Constructing identity through commemoration: Kwibuka and the rise of survivor nationalism in post-conflict Rwanda. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 57(3), 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X19000259

- Bhavnani, R., & Backer, D. (2000). Localized ethnic conflict and genocide: Accounting for differences in Rwanda and Burundi. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 44(3), 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002700044003001

- Boone, C. (2017). Sons of the soil conflict in Africa: Institutional determinants of ethnic conflict over land. World Development, 96, 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.012

- Bos, L., Schemer, C., Corbu, N., Hameleers, M., Andreadis, I., Schulz, A., Schmuck, D., Reinemann, C., & Fawzi, N. (2020). The effects of populism as a social identity frame on persuasion and mobilisation: Evidence from a 15‐country experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 59(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12334

- Bukari, K. N. (2013). Exploring indigenous approaches to conflict resolution: The Case of the Bawku Conflict in Ghana. Journal of Sociological Research, 4(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.5296/jsr.v4i2.3707

- Bukari, K. N., Osei-Kufuor, P., & Bukari, S. (2021). Chieftaincy conflicts in northern ghana: A constellation of actors and politics. African Security, 14(2), 156–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2021.1932244

- Cederman, L.-E., Wimmer, A., & Min, B. (2010). Why do ethnic groups rebel? New data and analysis. World Politics, 62(1), 87–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887109990219

- Cheeseman, N., Collord, M., & Reyntjens, F. (2018). War and democracy: The legacy of conflict in East Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 56(1), 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X17000623

- Collins, R. (2012). C-escalation and D-escalation: A Theory of the Time-dynamics of Conflict. American Sociological Review, 77(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411428221

- Dowd, C. (2015). Grievances, governance and Islamist violence in sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 53(4), 505–531. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X15000737

- Dueppen, S. A. (2016). The archaeology of West Africa, ca. 800 BCE to 1500 CE. History Compass, 14(6), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12316

- Gasu, J. (2020). Identity crisis and inter-ethnic conflicts in northern and upper east regions of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 17(1), 68–91. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v17i1.3

- Hall, T. H., & Ross, A. A. (2019). Rethinking affective experience and popular emotion: World War I and the construction of group emotion in international relations. Political Psychology, 40(6), 1357–1372. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12608

- Harff, B., & Gurr, T. R. (2018). Ethnic conflict in world politics. Routledge.

- Harkness, K. A. (2016). The ethnic army and the state: Explaining coup traps and the difficulties of democratization in Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60(4), 587–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002714545332

- Horowitz, D. L. (2000). Ethnic groups in conflict, updated edition with a new preface. Univ of California Press.

- Ibrahim, M. G., Mahama, E. S., & Fuseini, M. N (2022). Cultural dynamics and conflict management: Evidence from buipe and bole chieftaincy conflicts in the Savannah Region, Ghana. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 391, 403–4019. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.21340

- Jahn, H. (2020). Identities and Representations in Georgia from the 19th Century to the Present (Vol. 103). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Johannes, E. M., Zulu, L. C., & Kalipeni, E. (2015). Oil discovery in Turkana County, Kenya: A source of conflict or development? African Geographical Review, 34(2), 142–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2014.884466

- Jones W.J (1918) [Report of the Northern Territories for the Year 1935-1936) Public Records and Archives Administration Department (Folder NRT/02/08) Tamale, Northern Region

- Kindersley, N. (2019). Rule of whose law? The geography of authority in Juba, South Sudan. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 57(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X18000629

- Klaus, K., & Paller, J. W. (2017). Defending the city, defending votes: Campaign strategies in urban Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 55(4), 681–708. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X17000453

- Knop, K., & Riles, A. (2016). Space, Time, and Historical Injustice: A Feminist Conflict-of-Laws Approach to the Comfort Women Agreement. Cornell Reviwe, 102(2016–2017), 853–875. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/clqv102&div=26&id=&page=

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2019). Elite behaviour and citizen mobilisation. European Journal of Political Research, 58(2), 769–794. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12310

- Kuusaana, E. D., & Bukari, K. N. (2015). Land conflicts between smallholders and Fulani pastoralists in Ghana: Evidence from the Asante Akim North District (AAND). Journal of Rural Studies, 42, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.09.009

- Longi, F. Y. (2014). The Kusasi-Mamprusi Conflict in Bawku: A Legacy of British Colonial Policy in Northern Ghana. Ghana Studies, 17(1), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1353/ghs.2014.0004

- Lund, C. (2003). ‘Bawku is still volatile’: Ethno-political conflict and state recognition in Northern Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 41(4), 587–610. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X03004373

- Lund, C. (2006). Twilight institutions: Public authority and local politics in Africa. Development and Change, 37(4), 685–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2006.00497.x

- Maher, R. (2019). Pragmatic community resistance within new indigenous ruralities: Lessons from a failed hydropower dam in Chile. Journal of Rural Studies, 68(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.009

- Martell, P. (2019). First raise a flag: How South Sudan won the longest war but lost the peace. Oxford University Press.

- Mees, L. (2019). The Basque contention: Ethnicity, politics, violence. Routledge.

- Meuleman, B., Abts, K., Schmidt, P., Pettigrew, T. F., & Davidov, E. (2020). Economic conditions, group relative deprivation and ethnic threat perceptions: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(3), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550157

- Mironko, C. K. (2017). Ibitero Means and Motive in the Rwandan Genocide , Susan.E. Cook. In Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda 163–189. Routledge.

- Morelli, M., & Rohner, D. (2015). Resource concentration and civil wars. Journal of Development Economics, 117 (November, 2015) , 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.06.003

- Moritz, M. (2010). Understanding herder-farmer conflicts in West Africa: Outline of a processual approach. Human Organization, 69(2), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.69.2.aq85k02453w83363

- Mulich, J. (2018). Transformation at the margins: Imperial expansion and systemic change in world politics. Review of International Studies, 44(4), 694–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210518000074

- Naseemullah, A., & Staniland, P. (2016). Indirect rule and varieties of governance. Governance, 29(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12129

- Nyaaba, A. Y., & Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2019). The economic potentials of northern Ghana: the ambivalence of the colonial and post-colonial states to develop the North. African Economic History, 47(2), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1353/aeh.2019.0007

- Oucho, J. (2021). Undercurrents of ethnic conflict in Kenya. Brill.

- Petersen, R. D. (2001). Resistance and rebellion: Lessons from Eastern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Plange, N.-K., & Plange. (2007). The Colonial state in Northern Ghana: The political economy of pacification. Review of African Political Economy, 11(31), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056248408703598

- Saunders, M. N., & Bezzina, F. (2015). Reflections on conceptions of research methodology among management academics. European Management Journal, 33(5), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2015.06.002

- Soeters, S. R. (2012). Tamale 1907-1957: Between colonial trade and colonial chieftainship. Leiden University].

- Stavenhagen, R. (2016). Ethnic conflicts and the nation-state. Springer.

- Syme J. G (1931) [Report on Bawku elections 1931] Public Records and Archives Administration Department (Folder NRT/12/31) Tamale, Northern Region

- Tang, S. (2015). The onset of ethnic war: A general theory. Sociological Theory, 33(3), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275115599558

- Taras, R., & Ganguly, R. (2015). Understanding ethnic conflict. Routledge.

- Tonah, S. (2012). The politicisation of a chieftaincy conflict: The case of Dagbon, Northern Ghana. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 21(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.53228/njas.v21i1.177

- Twagiramungu, N., Duursma, A., Berhe, M. G., & De Waal, A. (2019). Re-describing transnational conflict in Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 57(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X19000107

- Ukiwo, U. (2003). Politics, ethno-religious conflicts and democratic consolidation in Nigeria. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 41(1), 115–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X02004172

- Venugopal, R. (2018). Nationalism, development and ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka, 5. Cambridge University Press.

- Verweijen, J., & Vlassenroot, K. (2015). Armed mobilisation and the nexus of territory, identity, and authority: The contested territorial aspirations of the Banyamulenge in eastern DR Congo. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 33(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2015.1066080

- Warren, T. C., & Troy, K. K. (2015). Explaining violent intra-ethnic conflict: Group fragmentation in the shadow of state power. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(3), 484–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713515400

- Zallé, O. (2019). Natural resources and economic growth in Africa: The role of institutional quality and human capital. Resources Policy, 62(1), 616–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.11.009