Abstract

The “Suku Anak Dalam” tribe (abbreviated as SAD) as an isolated tribe in Jambi, Indonesia, has become a topic of interest for several studies. The lack of in-depth study of education and leadership gives a negative perception of SAD. This article aims to reveal the influence of the Tumenggung leadership and the educational model in the context of SAD’s social life. The study used mixed methods. Data were obtained through questionnaires, observations, interviews, and documentation. Using stratified random sampling, the research samples of as many as 242 people were selected. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 with regression and flowchart analysis. The study partially proves that the variables presented are significant, namely the leadership of Tumenggung (77.9%), the read-write-count education model (56.5%), the political education model (72.2%), the environmental education model (67.5%), and health education model (77%). Simultaneously, the five variables also significantly influence the social life of SAD by 66.7%. It can be concluded that Tumenggung’s leadership and educational model have a significant and positive impact on SAD’s social life, as shown by the rise of awareness of reading, writing, and counting and political, environmental, and health-related awareness.

Public interest statement

As an isolated tribe, education has an important position for Suku Anak Dalam (SAD), education is needed to improve the quality of their social life, especially education in reading, writing, counting, political education, environmental education, and health education. With the modernity of the external environment of the SAD community, it has gradually threatened their social life because of their illiteracy, being politicized, their ecosystem is threatened with extinction, and their health status is low. It is recognized that the isolated tribal community certainly has its own culture that needs to be preserved, but this is closely related to the role of the Tumenggung leadership in leading the community. With this in mind, the author seeks to investigate the role of Tumenggung’s leadership in receiving external education to change the quality of the social life of the SAD. The results show that Tumenggung’s leadership plays an important role in transferring education to their community.

1. Introduction

Indonesia as a country, has many isolated tribes, they are tribes who live inland and isolated from the outside. In Aceh there are Mante tribes, in Jambi (Suku Anak Dalam tribes; well-known SAD), in Kalimantan (Badui tribes), in Riau (Sakai tribes), in Gorontalo (Polahi tribes), in Sulawesi (Togutil tribes), and in Papua (Korowai tribes). This study focused on the Suku Anak Dalam (SAD) in Jambi, especially SAD in Muaro Jambi Regency. The SAD are an isolated tribe that has lived for hundreds of years in the interior of Jambi, especially in several districts such as Sarolangun, Merangin, Batanghari, and Muaro Jambi regencies. They live in the interior by relying on the potential of nature to meet their needs. The SAD cultural entity that demands to live in the interior causes them to be isolated from the outside.

As one of an isolated community, the Suku Anak Dalam (SAD) tribe is different from other ethnic groups who have numerous chances and access to a decent life, education, technology, and a better future. SAD, on the other hand, is far from it all. Previous studies related to SAD focused more on the basic to nature approach (Prasetijo, Citation2013; Sager, Citation2008; Saleh, Citation2014), for example, discussed the lifestyle of SAD, local wisdom, and the role of the forest that is dwindling and will disappear. Since the early reports on SAD, they have always been described as living in deplorable conditions (Effendi & Purnomo, Citation2020; Marindatama, Citation2019; Persoon & Minter, Citation2020). The existence of social inequality for SAD makes this research interesting to study, primarily related to education. Indigenous education programs developed for or by indigenous communities have rarely been addressed SAD.

Nonetheless, compared to mainstream urban community education, interventions heavily promote instrumental approaches to “functional literacy” (Corson, Citation1998; Rao & Robinson-Pant, Citation2006), such as 12 years of compulsory education, character education, etc. Community-based education is a social action within the SAD community developed through agencies like NGOs as an institution. It begins with SAD and its immediate reality. To allow them to become meaningfully involved in shaping their futures through the NGOs in their community.

So far, studies on SAD have paid little attention to the educational aspect. In contrast to previous studies, this one explains how a systemic framework has enabled SAD who reject education to accept outside education as capital for their future. This paper aims to complement the lack of research on SAD from a leadership perspective by analyzing how it models and influences SAD. This paper is based on the argument that the leadership of the Tumenggung is not only beneficial for logistical and cultural matters but is also a way out of various problems. The SAD has a traditional leader or head called Tumenggung. The term Tumenggung in SAD is a leader or a tribal chief. The leadership role of the Tumenggung, the existence of models of political education, environmental education, and health education are solutions for SAD’s social life to survive, both on a SAD internal scale and SAD sustainability.

The article is organized into seven sections. First, it briefly explains the origin of SAD in Jambi. Second, it briefly explains the social hierarchy of SAD leadership. Third, it was followed by SAD education. Fourth, the section discusses significance of study. Fifth, methods. Sixth, results, and discussion. Seventh, conclusion, acknowledgments, and references.

2. Literature review

2.1. The origin of “Suku Anak Dalam” in Jambi

The origins of SAD as an isolated tribe are intimately connected to the tribe’s naming, which is complicated by the fact that the tribe has been given several names. Some of these names are SAD, Orang Rimba, Kubu, or Sanak. SAD is the name given by the government, while Orang Rimba is the name given by many NGOs such as Walhi and Warsi. The villagers gave the name Kubu, which means stronghold or defense. However, they despise being called Kubu since it makes them feel offended or ridiculed. They dislike the term Kubu since it has a negative connotation, whereas the term Sanak is used to refer to an isolated tribe. These terms are the same as seen from their position as isolated tribes, but some experts use different designations. This is due to differences in social background. Orang Rimba, for example, are characterized by nomadic, primitivism in dress, atheism, and upholding custom. SAD is characterized by openness, religious life, a sedentary lifestyle, and customary adjustments. The Kubu is characterized by primitivism in dress, atheism, and always protecting themselves from outside influences. The term SAD is used more frequently in this study.

There are various versions of the origin of SAD in Jambi. According to (Sager, Citation2008), Jambi is a region in Sumatra with unique cultures and tribes, specifically those that identify as SAD and have roughly 3,000 people. Maulana even stated that their population is estimated at around 200,000 people. SAD are Maalau Sesat people who fled to the forest known as Segayo’s ancestors. Some claim that the SAD has inhabited forest areas in Jambi Province, particularly Muaro Jambi Regency and Batanghari Regency, Sarolangun Regency, and Merangin Regency, since hundreds of years ago. It is estimated that there are 3,198 people scattered on the island of Sumatra, mostly from Jambi Province, apart from South Sumatra, more precisely in the Bukit Dua Belas National Park area, as many as 1,775 of the total population of 3,000 people in 2013 (Astarika, Citation2016). Ningsih and Sihid also said the SAD population in Muaro Jambi were 3,544 people spread over 11 regional points in Muaro Jambi. At the same time, SAD was located on the Serengam River, Batin XXIV, with as many as 89 families (Ningsih & Sihidi, Citation2022).

SADs in Jambi have traditionally lived in upstream lowland forest, which begins at the base of the Bukit Barisan mountains, with their customary forest ending around the Tembesi River or the central region of the province. In contrast to other nations in Sumatra, SAD has a unique and very diverse economy, which is constantly changing between the two basic subsystem strategies of shifting agriculture (behuma), nomadism (bebenor or remayo), and foraging for wild sweet potatoes (benor, especially Dioscorea sp.). Nomadism occurs mainly after the death of a group member but can also occur or be prolonged due to a preference only for lifestyle. It was traditionally combined with hunting, trapping, fishing, damming and poisoning rivers, and gathering forest products for trade. For many, part-time rubber tapping and participation in logging have gradually replaced forest product collection. In addition, some say that the origin of SAD comes from Palembang, namely the Panukal area, with the name Rajo Samikat. He is called the Kubu of shifting cultivation, and since hundreds of years ago, he has inhabited the forests of Muaro Jambi, Batanghari, Sarolangun, and Merangin in Jambi Province (Salam et al., Citation2020).

Many books, articles, lectures, and presentations teach us that, particularly for SAD as indigenous people, human beings have no ownership over the land (Greenwood & de Leeuw, Citation2007). SAD as foreigners were led by the Tumenggung, and in carrying out their lives, they are in groups. Each group is divided into small groups according to the bed or where they live (Putra, Citation2019). The SAD economy is unique and flexible in moving from a period of sedentary gardening and a very nomadic life based on digging wild yams and a large number of deaths (Sager, Citation2008). SAD has a small residence, is nomadic, and becomes the size of the nuclear family for a certain period, especially during SAD digging for wild yams, but is generally based around a large family (Sager, Citation2008; Viveiros de Castro, Citation1992). Based on the existing data, the SAD population of this study area is located in three places: Pengeratan Hamlet, Lubuk Kayu Aro Hamlet, and Skaladi Hamlet, Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency, as shown in Table .

Table 1. Distribution of SAD population in plempang village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency

3. Social hierarchy of SAD leadership

As essential factor, leadership can influence community involvement in realizing their characters (Samsu et al., Citation2021), no exception of social life SAD in Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency. Studying the leadership hierarchy in indigenous peoples such as SAD is essential in determining their presence in specific locations. The SAD leadership’s hierarchical structure in Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency can be summarized as follows.

Figure 1. Leadership hierarchy of SAD in Plempang village, Mestong district, Muaro Jambi Regency (Asman Hatta, interview, Skaladi hamlet, 5 September 2021).

Interpretations:

Tumenggung is the king of SAD

Depati is the vice king of SAD

Customary stakeholders are the judge of justice for SAD

Menti is the ministry of SAD

Dubalang is a commander of war for SAD

Jenang is the public relations of SAD.

Tumenggung, as SAD’s king, occupies a strategic position because of the activities he leads. The leadership of the Tumenggung can be seen in several activities such as weddings, besalih (magic), mutual cooperation (building traditional halls, residences, and houses of worship), learning to spear, self-defense, and food hunting with equipment like kujur and tiruk. In addition, the Tumenggung became the center of all policies related to SAD. In the context of leadership, the Tumenggung as a leader, tribal chief, or king for SAD, is to lead his community not through an election process but a hereditary system. The Tumenggung is selected based on the characteristics of the prospective Tumenggung, which include being knowledgeable and authoritative. The Tumenggung leadership has had a long-standing selection system in place. Tumenggung is selected as the leader based on a set of criteria. Tumenggung was then nominated and appointed at a ceremony. In the framework of his leadership system, SAD has incorporated “Jenton Turun Jenton” into its customary regulations. Jenton refers to Anak Dalam’s true son. In the context of political leadership, the SAD kinship system strengthened Tumenggung’s power as a respected leader. As for the health context, the Tumenggung’s involvement in the implementation of clean and healthy living behavior is also marked by their gradual openness to carry out health checks and hygiene through washing hands before eating, bathing, brushing teeth, cleaning for women who are menstruating, child immunization, and the formation of a taklim assembly for SAD mothers (Saputra et al., Citation2018).

Currently the Tumenggung in Plempang village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency is Datuk Soleh who has been a Tumenggung since 1960 until now. The age of Tumenggung Datuk Soleh is around 90 years old. The process of changing the Tumenggung will only be carried out if the Tumenggung Datuk Soleh dies. The change of leadership under the new Tumenggung occurred at the Menti level, namely from Menti Kohar to Menti Mansur. Dubalang Batin 1 is still led by Arbai since 1990, and Rubianto still leads Jenang until now. Rubianto can be selected as Jenang since he is married to the son of a Tumenggung named Mak Pia. He is not from SAD, but rather from outside (Palembang).

In terms of authority, the Tumenggung has the executive power to gather, direct, and decide on any case in the SAD community. Among these powers, the Tumenggung agreed that several NGOs should be included in the SAD community’s jurisdiction, but the Tumenggung resisted this because they thought their customs would be lost. Warsi, Walhi, and volunteers were among the NGOs that attempted to enter but failed, because none succeeded in influencing them in Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency. KAT da’i, on the other hand, has been successful in entering since 10 years ago. Since 2010, KAT da’i has taught SAD to write, read, and count, from animism to teaching Islam. Initially, the SAD taught were 40 children, the taklim assembly 50 SAD, and now all SAD, including members of the taklim assembly in Plempang Village, have all learned. With education, it is intended that SAD will become knowledgeable, capable of establishing settlements as communities, cultivating crops, organizing their culture and customs, and maintaining their health. Even though their leader is ignorant, the Tumenggung provides opportunities for SAD to learn. The following table represents the educational backgrounds of the Tumenggung, Depati, Menti, Pemangku Adat (Customary Holder), Dubalang, and Jenang.

The leadership of Tumenggung in SAD community can assist in understanding the community’s existence (Putra, Citation2019), including human capital and education are needed for economic growth and, finally, for poverty reduction (Awan et al., Citation2011). SAD gave the title of their leader the term Tumenggung. The concept of Tumenggung as a tribal chief is identical to cultural heritage from the era of the Srivijaya kingdom. Tumenggung is responsible for leading the SAD community according to customary law. Therefore, a Tumenggung needs the expertise to maintain control over his community and establish relationships with outside parties.

Tumenggung’s leadership is seen in their community problem-solving. Tumenggung’s ability to resolve cases fairly is critical if he intends to be respected by his community. Disobedience and flight to other groups are a response to dissatisfaction, bad policies, and political decisions (Erwin et al., Citation2020).

4. Suku Anak Dalam education

The SAD are synonymous with the concept of poverty, deplorable education, lack of political insight, lack of understanding of environmental quality, and quality of health. This condition boils down to the tradition they have built, namely melangun. The concept of melangun has implications for sedentary life patterns, ignoring the quality of their social life. Animist beliefs also influence sedentary lifestyles. This can be seen at the death of their family members, by leaving their place of residence, because death is considered a disaster for them.

Though the SAD were among the very first ethnic groups to be identified by the government as being in urgent need of civilization and development, and numerous efforts have been made to settle them, the resettlement villages have not generally been prosperous. In various documents reasons are given as to why this is the case. They refer to arguments such as the fact that the SAD are not used to the heat, the regular work rhythm in the agricultural fields. Mention is often made of the tradition of melangun, as the reason why people do not stay in a permanent settlement. The tradition of melangun refers to the custom of moving away from their dwelling place when a family member has passed away. This is done during a long period of mourning (Castillo & Strecker, Citation2017).

The cultural entity that is considered to be able to improve the quality of social life is through education, and this means that it must pass the Tumenggung’s power as policy makers in their community. Instilling education for SAD is important to do and understand because of the demands for the quality of their social life, which is difficult to change, except with education awareness for them.

The direct influence of the education model on poverty alleviation is through increasing income/wages while indirectly is important with respecting “human poverty” as education increases income, fulfillment of basic needs becomes more effortless and improves the standard of living. Education helps indirectly in meeting basic needs such as water and sanitation, utilization of health facilities, housing, and also affect behavior and decisions (Awan et al., Citation2011).

5. Significance of the study

Previous researchers have yet not attempted to link the model of education of SAD to indigenous leadership, even though, education has a vital role in the progress of an individual, community group, ethnic group, and even the life of a nation. Education is an effort made by a person or group so that they become adults and can achieve a higher level of life. All Indonesian citizens, including SAD, have the right to education and information to live properly because it is impossible to predict what will happen in the system of human civilization if an individual or group does not get an education. As a result, the government and the community seek education that fulfills high educational requirements for human empowerment.

SAD, on the other hand, who prefer to hunt and melangun, are less able to accept change, and are less inclined to accept progress and development. Although they have been provided explanations regarding new things like education, SAD will find it more difficult to embrace new things. They still prefer to wander rather than sit in class and listen to teachers’ lessons (Hidayat et al., Citation2013). In fact, the space for movement and culture of carrying out SAD is increasingly limited due to the development of industrially managed plantations. This fact affects the life of SAD who rely a lot on the forest environment. Hunting activities are getting narrower, food sources and livelihoods are getting more complicated. Jernang, the bark of kelatak, and rattan as an economical source are increasingly difficult to obtain. The difficulty of obtaining access to health also adds to the difficulty of SAD’s life, because their lives are in direct contact with nature, sleeping, and outdoor activities are very vulnerable to diseases, such as fever, diarrhea, and tuberculosis (TB).

As a result of the principle of SAD’s life, in the end they never get an education, because they are less open to people outside their ethnic group and new things. When meeting persons from other ethnic groups, SAD will be embarrassed. This is because it is assumed that even if SAD can read and write, they would be fooled by people who are not of their ethnicity, and that not everyone can open SAD’s minds to new possibilities. The habits discovered in SAD have the objective of opposing education, because education is the only thing that can change their habits (Lestari & Anwar, Citation2015).

SAD has negative thought if the school is a formal education. This negative view was obtained because of the lack of educational insight provided by Tumenggung, parents, and their ancestors. According to them, school education is not something they must do, because if they study at school, they will have less time for forestry. Thus, the threat is that if they cannot meet their basic needs from the forest, they will lose their livelihood and die (Hidayat et al., Citation2013). Formal education is a structured, tiered, systematic and multilevel activity from elementary school to university or its equivalent, including academic and general-oriented learning activities, and professional training programs that are carried out continuously (Darlin & Tandi, Citation2021; Leijon et al., Citation2022). This formal education is obviously in contrast to the SAD people’s lifestyle, as they live in the forest and exclusively use the forest’s natural resources to supply their daily requirements, therefore they spend their entire lives in the forest.

This study is eager to know, how the reality of SAD in Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency, Jambi-Indonesia especially relates to the impact of Tumenggung leadership on SAD’s education model and social life.

6. Methods

6.1. Study design and procedure

This mixed method approach with descriptive analysis was carried out from September 2020 through December 2021. The study used a questionnaire. A questionnaire was developed using the data collection instrument sheet, and was distributed through different each location (Pengeratan, Lubuk Kayu Aro, and Skaladi hamlets) by assisting from different research assistants, because the different location, and most of the subject are illiterate. The contribution of research assistants in this survey was voluntary and free of charge. Research assistant comes from volunteer. The anonymity of volunteer was guaranteed during the data collection process.

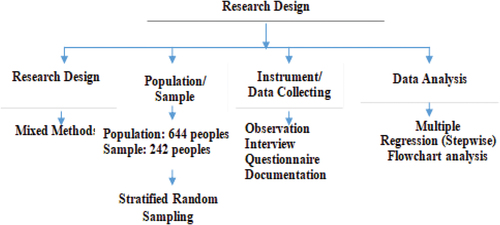

The study was conducted at Pengeratan, Lubuk Kayu Aro, and Skaladi hamlets, Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency in Jambi Province. The current study aimed to reveal the influence of the Tumenggung leadership and the educational model in the context of SAD’s social life. The study was mixed-methods conducted based on the data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 with regression and flowchart analysis. The primary quantitative data was obtained using a questionnaire to explore variables with a partial and simultaneous on Tumenggung leadership, and educational model in leading indigenous people. The direction of the project was guided by conversations with community members and elders to ensure that our research and research questions responded to concerns identified by indigenous peoples and that our relationship was ethical and non-exploitive [17]. The research design can be shown in .

6.2. Sample size calculations

The total population was 644 people, and the number of respondents as a sample was 242, including Tumenggung, Depati, Pemangku Adat, Menti, Dubalang, Jenang, the head of Plempang village, da’i KAT, and 234 SAD participants, were informed and invited to participate in this study. The participants had the same background and had lived in the forest long years ago. The researcher told them to give accurate answers in the questionnaire and interview. Researcher informed them that their data would be published publicly. Considerations in determining the number of samples are based on the difficulty of reaching the location of SAD and guided by the opinion of Krejcie and Morgan [19]. Based on the opinion of Krejcie and Morgan [19] which concluded that if there were 644 population, it means only 242 peoples can be sampled, and it can be a confidence level.

6.3. Data collection

From the total population of 644 people, the researcher identified that the existence of SAD in three areas, namely Pengeratan, Lubuk Kayu Aro, and Skaladi hamlets. It may be noted that all of them have inadequate and decent quality of social life, and this can only be broken down through education in a broad sense, namely their ability to write, read, count, political awareness, environment and health. Tumenggung has the policy authority and control over SAD to accept outside influences including education, politics, environment, and health issues. Tumenggung’s position is very decisive for their community.

Using this background, the researcher organized a dramatic viewing of SAD social life. Copies were made of all the 242 samples. For this, prior written permission was secured from LP2M as the representative of Rector, the head of Plempang village, and Tumenggung representative. The following days writing output samples were collected as data of SAD. These samples were collected in one step to ensure the adequate output. When the data is deemed sufficient, then the analysis stage is carried out.

The type of qualitative data collected was about Tumenggung’s leadership with interview procedures with introducing researcher’s themselves, conveying intent, and focused questions. Then, quantitative data collected were about education in reading, writing, arithmetic, politics, the environment, and health, as well as the social life of SAD. This data was carried out using a questionnaire procedure, with the help of a research assistant. Data collection instruments were made in the form of interview guides, and questionnaires and audio recorders. Some of the question items in the instrument changed during the study, and were corrected according to the results of audio recordings and the reality in the field.

6.4. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was distributed in bahasa melayu, the native language of Indonesian Language. The questionnaire was structured initially in bahasa melayu and then asked to SAD tribes by researcher, an expert research assistant who understood their local language was empowered to verified and explained the difficulties and mis-understanding questions which are given. The back-local language questionnaire answer was subsequently checked with original bahasa melayu one, by the researcher, aiming to repair the mistake and solve any inconsistencies between the two language versions. The questionnaire items were coded as 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). SPSS version 25.0 was used to calculate the findings. Descriptive analysis was conducted including the presenting of percentage.

The current questionnaire, methods, and tools used in this study were mainly adapted from the main issues that arise among SAD tribes they are read-write-count educational, political, environmental, and health issues. The questionnaire was constructed in all aspects that covered to leadership knowledge of Tumenggung in selected areas. The questionnaire was structured to collect information about leadership in term of Tumenggung leadership affects to each educational models, and social life of SAD.

The second section evaluated the general knowledge related to each educational models effects the social life of SAD. Participants responded to whether social life of SAD affected from 1) read-write-count educationa model, 2) political education model, 3) environmental education model, 4) health education model.

6.5. Data analysis

For quantitative, data collected were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25.0 (SPSS; https://www.ibm.com/be-en/products/spss-statistics). The stated variables were presented as mean standard deviation and 95% (.05) significance level. Categorical and ordinal variables were shown as percentage (%), and frequencies (n).

Correlation between Tumenggung leadership, educational models which were offered, and social life of SAD were determined by the multiple regression test. The result were presented in the form of descriptive statistics, coefficients, and model summary, and 95% significance level.

Furthermore, for qualitative, the data were analyzed using flowchart analysis [18]. The researcher produced a portopolio of all possible answers to classify the SAD educational model. The portopolio constructed of data coverage i.e., reading, writing, counting, Election of SAD leaders and general elections, preserving forestal area, eating, drinking, dressing, and personal health, and empathy, external interaction. The researcher checked each of the samples and classify them based on their answers. The researcher then carefully parses each corrected answer to identify each answer and records it in a portfolio.

The research design can be described in Figure .

7. Results

Based on the proposed hypothesis, partially the Tumenggung leadership (X1), read- write-count education model (X2), political education model (X3), environmental education model (X4), and the health education model (X5) separately have an influence on the social life of SAD (Y). Simultaneously, X1, X2, X3, X4 and X5 together have an influence on SAD’s social life (Y). Statistical analysis of this hypothesis was carried out through multiple regression analysis (stepwise). Statistical analysis of multiple regression (stepwise) followed by qualitative descriptive analysis, was conducted to provide understanding and conclusions about the data regarding the response of SAD to the leadership of Tumenggung and the educational model carried out on the social life of SAD. The study’s findings were revealed through qualitative descriptive analysis and hypothesis testing on data from the X1, X2, X3, X4, and X5. summarizes the above findings.

Table 2. Profile of SAD leadership in Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

The following section presents the hypothesis test results to identify the impact of Tumenggung leadership and educational model on SAD’s social life.

Quantitatively, five hypotheses (see, Table ) and one hypothesis (see, Table ) seemed to impact SAD’s social life. Partially, the first variable of leadership of Tumenggung (X1) affects the social life of SAD (Y) as much as 77.9%. Second, the variable read-write-count education model (X2) affects the social life of SAD (Y) by 56.5%. Third, political education model variables (X3) effect on social life of SAD (Y) by 72.2%. Fourth, environmental education model (X4) effects on social life SAD (Y) of 67.5%. Fifth, the health education model variable (X5) affects the social life of SAD (Y) by 77.0%, and sixth, simultaneously statistical analysis between the variables of X1, X2, X3, X4 and X5 affect the social life of SAD (Y) by 66.7%.

Table 4. The effect of variable X1-5 against Y (statistical analysis)

Table 5. The analysis results of determination coefficients of Tumenggung leadership (X1), read-write-count (X2), politics (X3), environment (X4), and health (X5) on SAD social life (Y)

Based on these findings, the read-write-count, political, environmental, and health education models may be classified as qualitatively the social life of SAD as indigenous people practiced by Tumenggung leadership. The read-write-count model is an education model which emphasizes the ability in reading, writing, and counting by SAD. Meanwhile, the political model is an education model which emphasizes engagement factors in political elections. The environmental model is an education model which emphasizes preserving forest areas, and forest product utilization of the SAD community. Meanwhile, the health model is an education model which emphasizes the health of eating, drinking, clothing, and personal health of SAD. Table shows the education model practiced on SAD in Plempang village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency, Jambi-Indonesia.

Table 6. The educational models of SAD at Plempang village, Mestong district, Muara Jambi regency in Jambi province

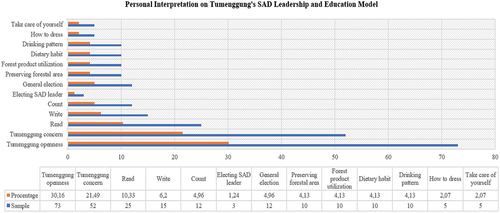

The influence of education with the education model read-write-count (see, ) in the hamlet of Plempang, District Mestong, Muaro Jambi Regency, Indonesia is demonstrated through reading, writing, and counting habits among SAD (from a total of 242 samples). Figure shows that personal interpretation on Tumenggung’s SAD leadership is carried out in the form of Tumenggung openness (30.16%) and Tumenggung concern (51.65%) (21.49%).

Similarly, the influence of education on the political education model (see, Figure ) is reflected in how SAD leaders are selected and how SAD elections are handled. Figure shows that the read-write-count education model of SAD has a 21.49 % educational influence in the form of reading (10.33 %), writing (6.2%), and counting (4.96%). The political education model (see, Figure ) is reflected in the attitude toward choosing the SAD leader and the general election conducted by the SAD. Table shows 6.20% of education influence is the read-write-count education model of SAD in the form of election of SAD leader (1.24%), and election (4.96%). Meanwhile, the influence of education with the environmental education model (see, Figure ) is reflected through the attitude of forest area conservation carried out by SAD. Figure shows 8.26% of education influence is the environmental education model of SAD in preserving forestall area (4.13%), and forest product utilization (4.13%). Meanwhile, the influence of education on the health education model (see, Figure ) is reflected in the attitude toward eating, drinking, dressing, and personal health. Figure shows 12.40% of education influence is the health education model of SAD in the form of eating (4.13%), drinking (4.13%), dressing (2.07%), and personal health (2.07%).

Based on the results of this quantitative analysis and reinforced by the results of observations on SAD social life indicating “the need for orientation to SAD social life to receive education, both related to read-write-count and education that leads to strengthen politics, the environment, and health, so that they can participate in promoting social life, smart and educated SAD”. Mu’in, a SAD resident from Hamlet Pengeratan in Plempang village, stated the SAD perspective about the importance of education:

“The parents and we believe that compulsory education is crucial so that our children do not repeat our follies, because if we can’t read, we won’t be able to choose a leader who will look after us, and there will be no more trees in the future. If you want to rely on the forest, which is no longer there, and thus there are no deer or other animals to eat, health education is also vital so that we may be healthy and not sick, as well as give and receive attention, and communicate with others. This educational awareness process is an essential part of our logic (Mu’in, interview, Pengeratan Hamlet, 8 May 2021)”.

It was hard to convince SAD to pursue reading, writing, counting education, and political, environmental, and health awareness. This is because they are terrified of being “sold” afterward. As a result, the SAD residents in the three hamlets in the Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency, Jambi Province, have always been wary of strangers entering their domain. On 6 September 2021, Asman Hatta, the Chairperson of the KAT da’i for the Muaro Jambi Regency area, stated in an interview:

“At first, SAD education was taught by volunteers, but many of them failed because SAD did not trust outsiders from their community. One of his worries about outsiders was that they would be ‘sold out.’ Because SAD people are extremely sensitive, they must employ specific techniques to calm them down, such as providing presents while influencing them and constantly teaching them until they trust us as outsiders. When that trust is established, education may take place in SAD (Asman Hatta, interview, Lubuk Kayu Aro Hamlet, 6 September 2021)”.

The following is a picture of SAD residents in Pengeratan, Lubuk Kayu Aro, and Skaladi hamlets at Plempang village, Mestong district, Muaro Jambi Regency, Jambi Province.

The Tumenggung location has become strategic due to the challenges of outsiders accessing the SAD community. SAD’s openness and concern for SAD’s life may be shown in numerous concepts, including individual concepts, societal concepts, leadership concepts, and other concepts that can be stated as follows ():

Table 7. Concept of SAD Leadership Behavior in Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency

It can be concluded that education that takes place in the social life of SAD is due to the leadership role of the Tumenggung, and educational activities brought by the da’i of the Komunitas Adat Terpencil (KAT), as well as related volunteers such as introducing SAD to how to read, write, and count, instilling education on clean and healthy living, environmental education through forest area conservation, and utilization of forest products, political education through involvement in political activities, especially in presidential and regional head elections. All of these educational activities are referred to as “education model”. This educational model grew because of Tumenggung Datuk Soleh and his staff’s willingness to let KAT da’i and other volunteers into SAD’s life and educate them ().

Figure 4. Profile of SAD at Pengeratan, Lubuk Kayu Aro, and Skaladi hamlets at Plempang village, Mestong district, Muaro Jambi regency (Asman Hatta, Observation, Pengeratan hamlet, 1 September 2021).

7.1. Discussion

Tumenggung leadership and the educational model offered to SAD natives in Pengeratan, Lubuk Kayu Aro, and Skaladi Hamlets, Plempang Village, Mestong District, Muaro Jambi Regency showed a significant effect, either partially or simultaneously, as seen from the statistical analysis presented. From this analysis, it is also known that the Tumenggung leadership model is shown by openness and concern for SAD. In addition, it is also known that the education model applied in SAD circles is the model of read-write-count education, politics, the environment, and health. The read-write-count education model is measured by SAD’s ability to read, write, and count. The political education model is measured from SAD leaders’ elections and general elections held by the government such as presidential, governor and regent elections. The environmental education model is measured from the conservation of forest areas, the use of forest products, while the health education model is measured from the pattern of eating, drinking, dressing, and personal health. These educational models are needed for local wisdom among SAD.

A study conducted by (Sinaga & Rustaman, Citation2015) shows the value of local wisdom such as harmony, balance, environmental preservation, sustainability, and the value of mutual cooperation is one form of the influence of environmental education, while in the context of the educational model (Hidayat, Citation2013; Zakiyah & Nurhafizah, Citation2021). Shows the meaning of individual SAD towards education is changing, namely by viewing education as something that is fun and profitable for their future, so that their aspirations and more decent jobs are opened.

The existence of education for SAD has opened insight and self-isolation that has been closed. The role of the educational model has revealed the social life of SAD which has been carried out under the leadership of the Tumenggung as the chief of the tribe (king) for SAD. They described in detail how they raised children in their indigenous tradition. At the same time, they acknowledged that indigenous knowledge and skills carry little value in the modern society they want their children to have access (Matengu et al., Citation2019). Although it is known that SAD finds it challenging to let go of its laws and traditions, as stated in Redcliffe Brown’s theory, isolated tribal communities believe in their traditions and laws (Asch, Citation2009; Shapiro, Citation1983). They are groups of people whose birth circumstances have limited relations with the outside world, properties that depend directly on nature, have a conservative nature, and hold a deep appreciation for traditions and customs. However, the culture adopted is easy to shift along with changes or changes in generations, including SAD. The culture change may be due to shifts in education, customs, external intervention, social politics, and leadership.

7.2. Conclusions

According to the findings, Tumenggung’s leadership has a significant impact on SAD’s social life (77.9%), the read, write, count education model has a significant impact on SAD’s social life (56.5%), the political education model has a significant impact on SAD’s social life (72.2%), the environmental education model has a significant impact on SAD’s social life (67.5%), and the health education model has a significant impact on SAD’s social life (77.00%). Likewise, simultaneously, the five variables offered significantly impact SAD’s social life by 66.7%. Thus, it can be concluded that the Tumenggung’s leadership and educational model offered are essential and influential on SAD’s social lives, as seen by the emergence of read-write-count awareness, political awareness, environmental awareness, and health awareness among SAD.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all those who have helped with completing this research. In this project thanked to Universitas Islam Negeri Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin Jambi, Indonesia, Universitas Islam Negeri Imam Bonjol Padang and Muhammadiyah University of West Sumatra, Indonesia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samsu Samsu

Samsu Samsu is an associate professor of Educational Leadership at Department of Islamic Education Management, Postgraduate, State Islamic University of Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin, Jambi, Indonesia. He has got his Master’s degree in Islamic Education Management from the State Islamic University of Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin, Jambi, Indonesia. He also has a Ph. D. degree in Educational Administration (Educational Management) from the National University of Malaysia, Malaysia. He is currently a lecturer at the Department of Islamic Education Management, Postgraduate, State Islamic University of Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin, Jambi, Indonesia. He has published for Scopus journal from reputable publisher including Elsevier and served as a reviewer for Sinta journal from several universities in Indonesia. His research interests include leadership issues in educational leadership, morals in leadership, and leadership behaviour. Our article is expected to contribute to the leadership studies and education for Indigenous people like Suku Anak Dalam (SAD) in Jambi, Indonesia.

References

- Asch, M. (2009). Radcliffe-Brown on Colonialism in Australia. Histories of Anthropology Annual, 5(1), 152–16. https://doi.org/10.1353/haa.0.0061

- Astarika, R. (2016). Konflik Agraria Suku Anak Dalam Jambi Dalam Tinjauan Sosiologi. In M. H. Arifin & R. Budiman (Eds.), Indonesia yang Berkeadilan Sosial tanpa Diskriminasi (pp. 109–124). Universitas Terbuka. http://repository.ut.ac.id/7988/1/FISIP201601-7.pdf

- Awan, M. S., Malik, N., Sarwar, H., & Waqas, M. (2011). Impact of education on poverty reduction. International Journal of Academic Research, 31826(31826). https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/31826

- Castillo, M. M., & Strecker, A. (2017). Heritage and rights of indigenous peoples=: Patrimonio y derechos de los pueblos indígenas (M. E. R. G. N. Jansen & J. Kamermans, eds.). Leiden University Press.

- Corson, D. (1998). Community-based education for indigenous cultures. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 11(3), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908319808666555

- Darlin, P., & Tandi, A. (2021). Strategy analysis of non-formal education service quality at the department of education and culture, Mamasa district. Devotion: Journal of Community Service, 3(2), 141–148. https://devotion.greenvest.co.id/index.php/dev/article/view/117/254

- De Castro, E. V. (2020). From the enemy's point of view. In From the Enemy's Point of View. University of Chicago Press.

- Effendi, G. N., & Purnomo, E. P. (2020). Collaboration Government and CSR A case study of Suku Anak Dalam in Pompa Air village, Jambi-Indonesia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business, Arts and Science, 2(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3632103

- Erwin, M., Zamheri, A., Darlies, M., Carlos, R., Seprianto, D., Rusnadi, I., & Tompunu, A. N. (2020). Criminal Law Policy on the Crime of Abuse to the Orang Rimba in the Bukit Duabelas National Park BT - Proceedings of the 3rd Forum in Research, Science, and Technology. 431(First 2019), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200407.033

- Greenwood, M., & de Leeuw, S. (2007). Teachings from the land: indigenous people, our health, our land, and our children. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 30(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.14288/cjne.v30i1.196413

- Hayward, A., Sjoblom, E., Sinclair, S., & Cidro, J. (2021). A new era of indigenous research: community-based indigenous research ethics protocols in Canada. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 16(4), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/15562646211023705

- Hidayat, M. S, Rahardjo, T., & Suprihatini, T. (2013). Penerimaan Suku Anak Dalam (SAD) terhadap Pendidikan. Universitas Diponegoro, 11, 1–14. https://ejournal3.undip.ac.id/index.php/interaksi-online/article/view/3620

- Leijon, M., Nordmo, I., Tieva, Å., & Troelsen, R. (2022). Formal learning spaces in Higher Education - a systematic review. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2066469

- Lestari, R. A., & Anwar, S. M. (2015). Pendidikan Antisipatoris Dalam Menghadapi Arus Transformasi Dunia Pada Novel Sokola Rimba Karya Butet Manurung. Buana Bastra, 2(2), 115–131. https://jurnal.unipasby.ac.id/index.php/bastra/article/view/228

- Marindatama, P. R. (2019). The effectiveness of empowerment program for indigenous communities: study case of policy about “merumahkan” Suku Anak Dalam in Sarolangun, Jambi. Gadjah Mada University. March 2019 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351194270

- Matengu, M., Korkeamäki, R. L., & Cleghorn, A. (2019). Conceptualizing meaningful education: The voices of indigenous parents of young children. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 22(May), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.05.007

- Ningsih, W. M., & Sihidi, I. T. (2022). Analysis of community empowerment programs in the Suku Anak Dalam Community (Orang Rimba) at Talang Kejumat Settlement Location, Limbur Tembesi, Bathin VIII, Sarolangun Regency. Budapest International Research and Critics in Linguistics and Education (Birle) Journal, 5(1), 3577–3588. https://doi.org/10.33258/birci.v5i1.4025

- Persoon, G. A., & Minter, T. (2020). Knowledge and practices of indigenous peoples in the context of resource management in relation to climate change in Southeast Asia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(19), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197983

- Prasetijo, A. (2013). Behind the forest: the ethnic identity of Orang Kubu (Orang Rimba), Jambi-Indonesia. 10th Conference on Hunting and Gathering Societies 25-28 June, 2013, liverpool school of archaeology, classics & egyptology, University of Liverpool.

- Putra, S. (2019). “Jenton Turun Jenton” Leadership of Tumenggung nggrip on community Orang Rimba in Kedundung Muda, Bukit Duabelas National Park, Jambi, Indonesia. Sociae Polites, 20(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.33541/sp.v20i1.1440

- Rao, N., & Robinson-Pant, A. (2006). Adult education and indigenous people: Addressing gender in policy and practice. International Journal of Educational Development, 26(2), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2005.07.026

- Sager, S. (2008). The Sky is our Roof, the Earth our Floor Orang Rimba Customs and Religion in the Bukit Duabelas region of Jambi, Sumatra. Australian National University. https://doi.org/10.25911/5d7a2d0a4fcc8

- Salam, M., Syarifuddin, A., & Wahyuni, A. (2020). Fading foraging: Changes in life patterns of the Suku Anak Dalam in Sarolangun Jambi. International Journal of Education and Social Science Research, 3(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.37500/IJESSR.2020.3601

- Saleh, S. (2014). Agama, Kepercayaan, dan Kelestarian Lingkungan Studi terhadap Gaya Hidup Orang Rimba Menjaga Lingkungan di Taman Nasional Bukit Dua Belas (Tnbd)- Jambi. Jurnal Kawistara, 4(3), 225–322. https://doi.org/10.22146/kawistara.6386

- Samsu, S., Kustati, M., Perrodin, D. D., & Suwendi, S. (2021). Community Empowerment in Leading” Pesantren”: A Research of” Nyai”‘s Leadership. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 10(4), 1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v10i4.21833

- Saputra, N. E., Kalsum, U., & Ekawati, Y. N. (2018). Upaya Meningkatkan Pengetahuan dan Keterampilan Perilaku Hidup Bersih dan Sehat (PHBS) Orang Rimba Melalui the Attempt to Improve Knowledge and Skill of Clean and Healthy. Jurnal Pengabdian Dan Pemberdayaan Masyarakat, 2(2), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.30595/jppm.v2i2.2590

- Shapiro, W. (1983). The building of British social anthropology. American Anthropologist, 85(1), 176–177. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1983.85.1.02a00400

- Sinaga, L. Y., & Rustaman, N. Y. (2015). Nilai-Nilai Kearifan Lokal Suku Anak Dalam Provinsi Jambi terhadap Perladangan di Hutan Taman Nasional Bukit Duabelas sebagai Sumber Belajar Biologi. Proceeding Biology Education Conference, 12(1), 761–766. https://jurnal.uns.ac.id/prosbi/article/view/7082

- Zakiyah, & Nurhafizah. (2021). Early childhood social and emotional development of Suku Anak Dalam (SAD). Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Early Childhood Education (ICECE 2020), 538(Icece 2020), 321–325. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210322.068