Abstract

Muslim-Friendly Beauty and Wellness (MFBW) is rapidly becoming a component of Muslim-Friendly Tourism packages and Muslim-Friendly Hospitality Services. As Malaysia intensifies its effort to attract more Muslim tourists, it is introducing various types of initiatives. MFBW is among the latest services being offered. While there have been several attempts to define MFBW, a variety of authors have differed in their conceptualisations of it. Nonetheless, their definitions do contain some similarities, such as gender segregation in the provision of services. The aim of this study is to review the literature pertaining to MFBW and subsequently develop a taxonomy and measures that represent MFBW implementation. The taxonomy can be used to develop a measurement tool for the beauty and wellness industry’s readiness to embrace MFBW.

1. Introduction

Muslim-Friendly Tourism (MFT) is gaining attention not only in Malaysia but also in other parts of the world that generally target Muslim travelers. These travelers comprise an attractive market segment, growing at a rate that is well above average; there was an increase from 108 million Muslim travelers in 2014 to 150 million in 2020. MFT is based on Islamic Sharia Law, which guides all aspects of a Muslim’s life from birth to death. The term Muslim-Friendly (MF) is used interchangeably with terms such as halal, Islamic and Sharia-compliant. An overview of the available literature reveals that MFT has been studied in many contexts, including the implementation of MFT in hotels and by tourism business operators (Junaidi, Citation2020; Md Salleh et al., Citation2019), MFT status in countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia (Aziz, Citation2018; Bastaman, Citation2018; Marican et al., Citation2021; Ristawati et al., Citation2019) and an examination of constructs such as tourist attitude toward destination, destination image and travel intention within the tourism industry (Liu et al., Citation2018).

According to Junaidi (Citation2020), most travelers in this market segment search for an integrated MFT package, and professional beauty and wellness services are recognised as part of MFT or Muslim-Friendly Hospitality services. Professional Muslim-Friendly Beauty and Wellness services (MFBW) are in high demand as a result of economic development, globalisation, urbanisation, health concerns and religious requirements (Othman et al., Citation2015). Sobari et al. (Citation2019) state the following:

[T]he wellness industry consists of ten sectors providing goods and services that are of significant value and interrelated with one another. They are spa; wellness tourism; thermal/mineral springs; workplace wellness; wellness lifestyle real estate; healthy eating, nutrition and weight loss; fitness and mind-body; beauty and anti-aging; preventive and personalized medicine and public health; and complementary and alternative medicine. (p. 2)

A subcategory within MFT is MFBW. The available literature indicates that there is an increased interest in MFBW. Most studies focus on Muslim-friendly spas. A few studies examine the perception of the spa services provided and the development of a conceptual framework (Bafadhal et al., Citation2017; Mutimmatul, Citation2015). Other authors propose a specific MF spa framework (Chanin, Citation2016; Jamaluddin et al., Citation2018; Zikri & Yahaya, Citation2019), while Noipom et al. (Citation2019) recommend MF wellness spa service standards. These studies, however, are conceptual in nature. Notably, one empirical study examines ten Muslim-friendly spas using the case study method (Yaman et al., Citation2012).

An assessment of the current discussion regarding MFBW reveals the need to create a standard taxonomy or instrument to measure MFBW. Hence, the present study aims to fill this gap. The demand for MFBW services is high and growing steadily in both Muslim and non-Muslim countries. The term “Muslim-friendly” has a strong association with halal, which is globally recognised as a benchmark for product safety and quality (Azmi et al., Citation2018). Moreover, service providers are aware that Muslim consumers are always vigilant and conscientious in their efforts to obtain services that comply with the Sharia principles. The providers perceive MFBW as an opportunity to be part of the Malaysian government’s MF Tourism initiative, which includes MFBW as a component. The present study proposes an MFBW standardised measurement to be adopted by various stakeholders and endorsed by relevant authorities such as JAKIM, the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia. Thus, the following objectives are formulated:

To develop a taxonomy that presents MFBW implementation

To establish an instrument that measures MFBW.

2. Materials and methods

MFBW is a retail and service concept that promotes wellness through the provision of therapeutic and other professional services aimed at renewing, restoring, refreshing and rejuvenating the body, mind and spirit while adhering to the Sharia principles. In other words, an MFBW establishment offers professional services in accordance with Sharia law in terms of services, management and products (Halim & Hatta, Citation2017). Studies performed regarding MFBW have adopted interviews (Bafadhal et al., Citation2017; Zikri & Yahaya, Citation2019) and case study methods (Mutimmatul, Citation2015; Yaman et al., Citation2012). Most studies were conducted in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia (Zikri & Yahaya, Citation2019), Indonesia (Bafadhal et al., Citation2017; Mutimmatul, Citation2015), Thailand (Noipom et al., Citation2019b) and Brunei (Md Salleh et al., Citation2019).

In order to determine the MFBW elements, we referred to studies on MF spas. One study focused on ten elements that cover operations, products and services offered, facilities provided, layout and design (Yaman et al., Citation2012). Another study examined facilities and equipment, products and services, staff, finance, design and decoration (Halim & Hatta, Citation2017). A study by Noipom et al. (Citation2019) proposed halal spa service standards, consisting of seven criteria that are related to place, manager, therapist, service standards, products, equipment and accessories, services criteria and safety criteria. Similarly, Marican et al. (Citation2021) proposed a framework for a Sharia-compliant spa that includes the Islamic Spa Practices and Maqasid Shar’iyyah elements. These elements include protection of religion (Al-Diin), protection of life (Al-Hayah), protection of mind (Al-‘Aql), protection of dignity (Al-Muru’ah) and protection of wealth (Al-Mal).

The present study first examined existing literature related to MFBW. We adopted the content analysis approach in order to arrive upon a standard taxonomy and evaluation instrument; this method is appropriate because it employs the process of identifying, coding and categorising the primary patterns in the data (Dezdar & Sulaiman, Citation2011). There are numerous ways to conduct content analysis. In this study we adopted Neuman’s (Citation1997) approach, which involved data collection and coding.

2.1. Data collection

We began the search for articles relevant to MFBW in the Scopus and Web of Science databases; however, the search did not result in many hits. Hence, we used Google Scholar to access articles published in journals that are not indexed in these databases. The keywords used to extract past studies were “Muslim friendly or Sharia compliance”, “halal”, “spa”, “beauty”, “wellness” and “health”. Using these keywords, a total of 8,410 hits were obtained. Subsequently, the researchers used the advanced search features to narrow down the search, and they found 25 articles pertaining to the area of study. The other articles focused on Islamic hospitality, accommodation, tourism and services in a more general manner. Finally, the researchers reviewed the 25 articles and concluded that only 14 articles were relevant to the objectives of the study. Following the data collection, coding was performed by three coders to increase the reliability of the outcome. The coding process is described in basic terms in the following section.

2.2. Coding process

Coding was carried out in four stages. In line with the first objective of the study to develop a taxonomy, coders first identified categories of factors (constructs) that constitute MFBW in the 14 articles. Each coder listed the constructs in an Excel sheet. Next, the coders met together to compare their results, and they found that nearly 90% of their entries were similar. The coders then discussed the differences and arrived at a final consensus. In this stage they identified 21 factors.

The second coding stage involved reviewing all MFBW constructs (21 in total) and recategorising them. All three coders recoded the constructs independently and then compared their results. They discovered that nearly 85% of the time, the coding was consistent among them. The items that were not similarly coded were highlighted and discussed until a consensus was reached.

Subsequently, in the third round of coding the coders reviewed all items (which were listed in Excel and distributed to the coders) that were used to describe MFBW. In this stage the coders were instructed to perform two functions: 1) remove items that do not reflect MFBW specifically and 2) remove duplications. All coders compared their analyses at the end of this stage. Results showed that there was 75% consistency in the removal of items that were not entirely relevant and 95% consistency in the process of duplication removal. They held a discussion to finalise the number of items.

The fourth round of coding focused on the selected final items. The coders classified each item according to the constructs agreed upon in stage two. At this stage, based on the definition of the constructs given to each coder, there was a high level of consistency among the coders (98%). The coders then performed a final validation of all the items.

3. Results

The coders reviewed all 14 articles that pertained to the objectives of the study. In the first stage of the coding process, results showed that a few of the authors who studied MFBW specified some basic categorisation (Halim & Hatta, Citation2017; Zikri & Yahaya, Citation2019), while others proposed several specific categories: personnel, facilities and equipment, product and services, finance, interior design and layout, operations and information (Marican et al., Citation2021; Noipom et al., Citation2019). The coders identified a total of 21 constructs. Table presents the matrix between constructs and source.

Table 1. Matrix of constructs and source

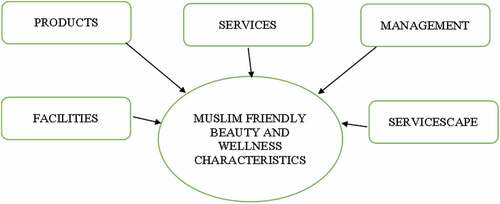

Subsequently, after the second stage of coding, the coders concluded that the constructs could be summarised into five categories: products, services, management, facilities and servicescape (see, Figure ). The product category includes the materials and ingredients in the products offered or used by a service provider (i.e., MFBW). Product ingredients can directly influence customers’ perceptions of the overall product quality (Zou & Liu, Citation2019). The service category includes all activities and acts performed by service providers for their customers. The quality of the service procedures generally creates service expectations, which can lead to satisfaction and repatronage intention (Bove & Johnson, Citation2006). The management category comprises a service company’s administration methods in terms of its policies and procedures for human resources, finances, etc. Clear, unambiguous service policies promote higher employee satisfaction and trust (Hogreve et al., Citation2017). This important service element can lead to improved customer engagement. Next, the facilities category consists of the physical features, amenities and resources offered by a service provider when delivering services to customers. Service facilities are an integral part of the service environment and can improve or worsen customers’ impressions (Sarkar et al., Citation2020). Likewise, service facility design has a crucial impact on the consumption experience (Parish et al., Citation2008). Finally, servicescape is described as the service provider’s exterior (landscape, exterior design, signage, parking, surrounding environment); interior (interior design and decor, equipment, signage, layout); and ambient conditions (air quality, temperature and lighting). A well-designed and organised store ambience tends to generate an enjoyable and fun service experience (Bian & Forsythe, Citation2012).

This categorisation process was followed by the third coding stage, in which coders listed 210 MFBW characteristics that were proposed by authors from the selected 14 articles. From the 210 listed, the coders first removed items that were not specific to MFBW but reflected general beauty and wellness, and then they removed all duplications or redundant items. At the end of this process, 76 items remained.

In the fourth stage of coding, the 76 items were grouped into the five categories (constructs) agreed upon in stage two, i.e., products, services, management, facilities and servicescape. Following a final round of coding and validation, the coders devised the final taxonomy and items, as presented in Table .

4. Discussion

Our results show that these five categories are sufficiently specific to capture the essence of the MFBW business model. Most items in the products category emphasise the importance of halal ingredients in products. Only one entry identifies the need for logistical procedures to ensure that halal products will not be transported alongside non-halal counterparts. In the services category, it is clear that segregation between the male and female genders is crucial for both customers and employees. This separation must be a core element in the provision of MFBW services. It should also be noted that illegal and sinful activities, such as gambling or selling alcohol on the business premises, are prohibited altogether. Most importantly, MFBW businesses should protect customers’ aurat (i.e parts of body that should be covered) and privacy. The management category features many items that are in line with the services category, especially concerning gender segregation and same-gender customer-employee interactions. The list specifically disallows the recruitment of employees with an ambiguous gender orientation. The other items in this category relate to operation and management practices in the areas of taxes, investment practices, financial sources, and zakat (alms giving). Next, the items in the facilities category focus on facilities, equipment and amenities provided by MFBW businesses. Again, segregation of gender is key, and consequently, space sharing between genders is forbidden. Adopting this policy can be a challenge for existing MFBW businesses, especially when they use shared facilities due to retail space or financial limitations. To comply with the requirement, the businesses would need to invest in expansions. To this end, current MFBW business owners should examine their business growth based on location, pulling power and customer growth forecast. However, a new MFBW business that is in the planning stage should give due consideration to this element of the MFBW model in advance. Lastly, the servicescape category focuses on retail ambience. Décor elements must be void of all human and animal depictions and imageries. Appropriate aromas and sounds can enhance the MFBW experience, and sensory stimulations such as these are key to developing a loyal customer base. It is important that any suggestive sexual elements in the establishment settings are removed, as the customers for this service business model are seeking Muslim-friendly and family-friendly beauty and wellness treatments.

5. Conclusions

The MFBW industry is growing rapidly as a result of an increase in market demands for Muslim-friendly services and products. These flourishing market segments are pushing both local and global companies to adapt quickly. To make the appropriate adaptations, businesses can refer to Sharia principles as they adjust their brands and offerings to cater to this market. While halal requirements for products are clear, the boundaries of acceptable “halalness” for services can be somewhat blurry, especially for service business owners who lack the proper knowledge and understanding on the subject. Our purpose was to identify specific Sharia principles that can guide service business owners to enhance their business marketability and growth.

To achieve this purpose, the present study aimed to fill the gap in the MFBW literature. This literature is especially limited from indexed databases, so we relied only on articles listed in Google Scholar. Nonetheless, undeterred by this limitation, we successfully coded and narrowed down the list of items that can determine how MFBW businesses should operate, guided by the Sharia principles. These items are divided into five categories. We believe that our efforts are beneficial to the further development of the MFBW segment and to MFT in general. Ultimately, our lists can be used as a basis for classifying the beauty and wellness industry and ensuring Sharia compliance. Additionally, our item lists can be a quick reference for customers when they are searching for these types of beauty and wellness services. It is hoped that with MFBW, Malaysia will be able to attract more international tourists that are interested to experience MFT.

As with any research, this study has limitations. The selection and development of the constructs and items were based on 14 articles. Future research may include other articles. Moving forward, we hope to test and validate the items by conducting an expert panel evaluation with relevant stakeholders. We also hope to use our items to collect empirical evidence in the future, enabling us to analyse providers’ readiness to offer MFBW services.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of a larger study which was funded by Universiti Malaya (grant number BKS001-2019). We would also like to acknowledge the UM Halal Research Center staff for the administrative and technical support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aziz, A. H. B. A. (2018). Muslim friendly tourism: Concept, practices and challenges in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(11), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v8-i11/4908

- Azmi, F. R., Abdullah, A., Bakri, M. H., Musa, H., & Jayakrishnan, M. (2018). The adoption of Halal food supply chain towards the performance of food manufacturing in Malaysia. Management Science Letters, 8(7), 755–13. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2018.5.010

- Bafadhal, A., Yulianto, S., Siswidiyanto, E., & Hendrawan, M. R. (2017). Concept and model of Sharia salons and spas: Myth or reality? Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 70(10), 38–44. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5a71/61b9d4cc6abfc2d4c49b6bc9005061c6c0ea.pdf?_ga=2.155562168.2076069047.1663765980-1425264954.1663765980

- Bastaman, A. (2018). Lombok Islamic tourism attractiveness: Non-Moslem perspectives. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 7(2), 206–210.

- Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.010

- Bove, L. L., & Johnson, L. W. (2006). Customer loyalty to one service worker: Should it be discouraged? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.01.007

- Chanin, O. (2016). The conceptual framework for a sustainable halal spa business in the Gulf of Thailand. International Journal of Management Studies, 23(2), 83–95. https://e-journal.uum.edu.my/index.php/ijms/article/view/10471

- Dezdar, S., & Sulaiman, A. (2011). Critical success factors for ERP implementation: Insights from a Middle-Eastern Country. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 10(6), 798–808. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Critical-Success-Factors-for-Erp-Implementation%3A-a-Dezdar-Ainin/d8423f3d3f2e3a85d2899d1f2c1fc18f788c141e

- Halim, S. F. A. A., & Hatta, F. A. M. (2017). Shari’ah compliant spa practices in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 8(9), 2038–2050. https://www.majcafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/9.-Shari%E2%80%99ah-Compliant-Spa-Practices-In-Malaysia-1.pdf

- Hogreve, J., Iseke, A., Derfuss, K., & Eller, T. (2017). The service-profit chain: A meta-analytic test of a comprehensive theoretical framework. Journal of Marketing, 81(3), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0395

- Jamaluddin, N. S. N. B., Mokhtar, A. B., Hashim, K. S. H.-Y., Othman, R., Nazri, N. J. Z., Rosman, A. S., & Fadzillah, N. A. (2018). Study on Muslim friendly spa: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(9), 2039–2050. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v8-i9/5186

- Junaidi, J. (2020). Halal-friendly tourism and factors influencing halal tourism. Management Science Letters, 10(8), 1755–1762. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.1.004

- Liu, Y. C., Li, I.-C., Yen, S.-Y., & Sher, P. J. (2018). What makes Muslim friendly tourism? An empirical study on destination image, tourist attitude and travel intention. Advances in Management & Applied Economics, 8(5), 27–43. https://ideas.repec.org/a/spt/admaec/v8y2018i5f8_5_3.html

- Marican, N. D., Sumardi, N. A., Che Aziz, R., Bah Simpong, D., & Hasbollah, H. R. (2021). The Shari’ah compliance spa for wellness and tourism context in Malaysia. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(3), 2978–2986. https://doi.org/10.17762/turcomat.v12i3.1329

- Md Salleh, N. Z., Md Nor, R., Selamat, R., Baharun, R., Abdullah, D. F., & Omain, S. Z. (2019). Challenges in implementing Islamic friendly hotel in Malaysia. Journal of Economic Info, 6(4), 15–17. https://doi.org/10.31580/jei.v6i4.1052

- Mutimmatul, F. (2015). The services of halal spa: The case in Surabaya Indonesia. In 1st World Islamic Social Science Congress (WISSC). Putrajaya International Convention Centre (PICC) Malaysia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328732437_The_Services_of_Halal_Spa_The_Case_in_Surabaya_Indonesia

- Mutimmatul, F., Hery, R., Lilik, R., Nia, K., & Fifi Putri, W. (2021). Exploring Muslim Tourist Needs at Halal Spa Facilities to Support Indonesia’s Sharia Tourism. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 9(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.21427/qme4-g097

- Neuman, W. L. (1997). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

- Noipom, T., Hayeemad, M., & Duereh, S. (2019b). Examining the need for and propossing major criteria and requirements of halal spa service standard in Thailand. International Conference on Islam in Malay World IX ICONIMAD (pp. 568–579).

- Noipom, T., Hayeemad, M., Hassama, A., & Nuh, R. (2019a). Halal Wellness Spa Services Standard in Thailand: Development and Challenges. International Halal Conference & Exhibition 2019 (IHCE), 1(1), 287–292. https://jurnal.pancabudi.ac.id/index.php/ihce/article/view/641

- Othman, R., Halim, S. F. A. A., Hashim, K. S. H. Y., Baharuddin, Z. M., & Mahamod, L. H. (2015). The emergence of Islamic spa concept. Advanced Science Letters, 21(6), 1750–1753. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2015.6187

- Parish, J. T., Berry, L. L., & Lam, S. Y. (2008). The effect of the servicescape on service workers. Journal of Service Research, 10(3), 220–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507310770

- Ristawati, H., Saufi, A., & Rinuastuti, H. (2019). Effect of customer experience and innovative value on halal destination image and satisfaction of domestic tourists in Lombok Island. Global Journal of Management and Business, 19(3), 1–7.

- Sarkar, J. G., Sarkar, A., & Balaji, M. S. (2020). The “right-to-refuse-service” paradox: Other customers’ perception of discretionary service denial. Journal of Business Research, 117(December), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.036

- Sobari, N., Kurniati, A., & Usman, H. (2019). The influence of Islamic attributes and religious commitments toward halal wellness services customer satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Islamic Marketing, Online, 13(1), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-11-2018-0221

- Staufenberg, J. (2015). H&M features its first Muslim model in a hijab. Independent.Co.Uk. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/h-m-features-its-first-muslim-model-hijab-a6668211.html

- Yaman, R., Alias, Z., & Ishak, N. M. (2012). Beauty treatment and spa design from Islamic perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 50, 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.08.053

- Zikri, K. N., & Yahaya, M. Z. (2019). Spa berkonsepkan Islam di Malaysia. Jurnal Penyelidikan Islam Dan Kontemporari (JOIRC), 2(3), 1–11. http://www.joirc.com/PDF/JOIRC-2019-03-06-03.pdf

- Zou, P., & Liu, J. (2019). How nutrition information influences online food sales. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(6), 1132–1150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00668-4

Appendix

Table A1. MFBW taxonomy and items