Abstract

The search for alternative knowledge, conspiracy theories, distrust of expertise and anti-science movements are gaining momentum and post-truth populism is speeding up on the back of fake news. The crisis of truth refers to an era where evidence and objective facts get lost in sentiment, emotion, and personal beliefs. Relying on emotions, creationism, religious beliefs, and common sense over expertise deliberately creates counter-knowledge referred to as pseudo-science, troll-science or fake-science. As the worth of scientific expertise is devalued, the counter-scientific discourses supported through populist political rhetoric help to produce a culture of resistance to science. Our qualitative content analysis of Twitter posts along with the news regarding anti-vaccine arguments from two selected online news sites, revealed three major themes, which we referred to as strategies used by the COVID-19 vaccine deniers in Turkey to disseminate their views. These were: an emphasis on bodily freedom and personal choice and the use of “my body my choice” rhetoric; the denying, devaluing, and shifting of scientific evidence; and the dismissal and/or attacking of alternative views and the deepening of the polarisation between the supporters of the COVID-19 restrictions, vaccine supporters and deniers. We conclude the paper by arguing that there is a link between the distrust of doctors and the anti-vaccination ideas, and the quest for alternative knowledge and expert authority.

1. Introduction

Take a square to represent the class of all statements of a language in which we intend to formulate a science; draw a broad horizontal line, dividing it into an upper and lower half; write ‘science’ and ‘testable’ into the upper half, and ‘metaphysics’ and ‘non-testable’ into the lower: then, I hope, you will realize that I do not propose to draw the line of demarcation in such a way that it coincides with the limits of a language, leaving science inside, and banning metaphysics by excluding it from the class of meaningful statements. (Shearmur, Citation2002).

Science is a system of knowledge production which includes the interplay between intellectual curiosity, empirical testing and peer review. Scientific knowledge is also a form of cultural design (Popper, Citation2005). It is formed through extended processes of selection and retention, first in the scientific community, and then gradually in the public at large. What is scientific knowledge is one thing, and how we approach it, is another. The authority of science has an impact on how we perceive scientific knowledge; usually we take it for granted and do not question its production processes.

Practical life, composed of contingent situations, is always provisional and always fallible. The Greeks also used another term for knowledge, which refers to a particular personal kind of knowledge. This was Gnosis; knowledge based on personal experience; “lived experience”. Since science does not often refer to our intuitions and desires, what we see today is that “objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” (McIntyre, Citation2018, p. 5). The belief that “the truth will set you free” appropriated by the Enlightenment is shaken, “truth has been eclipsed” (McIntyre, Citation2018, p. 5) and the road of progress built by scientific discovery and technological invention is questioned. The crisis of truth stems from the increasing disconnection between what people can bear witness to in their own lives and what they take to be officially recognized by the institutions. The promised possibilities—liberty, equality, prosperity, and health—lose their compelling force. Because of this disconnect, in the absence of ties, scientific authority is easily reduced to non-scientific spokespersons (Arendt & Kohn, Citation2006, pp. 92–93).

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us that people seek a “finished” and certain science (Babich, Citation2021). This may be because an unknown virus with unknown consequences entailed a restriction of lifestyles as the rule for an unknown period. The positive experience of being in a community, or face-to-face interaction and feeling safe when we are with other people, were not supported by the changes in the science of pandemics. Even the health recommendations issued by the World Health Organization (WHO)—the two-metre social-distancing rule, along with many other recommendations—became government-mandated health restrictions.

During the pandemic, the internet offered fake news, as well as conspiracy theories, from a diversity of sources. Counter-movements emerged that challenged scientific discourses and research results. As we will show later in this paper, for some people seeking alternative knowledge served to echo practical personal experiences with emotions. Borrowing Eslen-Ziya et al.’s (Citation2019) emotional-echo-chamber theory, we study how alternative knowledge, once loaded with emotions, acts as a self-expressive tool that connects individuals with similar beliefs to one another. In this paper, by studying the tweets shared to invite people to protest against COVID-19 vaccination and COVID-19 imposed restrictions in three major Turkish cities (Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir), we will explore how the anti-science misinformation and conspiracies are discursively framed and interpreted and linked to the attacks on medical expertise. Before we go into the anti-COVID mobilisation, we will first study how in Turkey the distrust of scientific authority has been fostered by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government as a populist propaganda strategy.

2. Crises of truth or scientific authority?

We claim that truth is a social construction, and it is not the truth that is in crisis, the authority of scientific truth is going through a challenging phase (Hekman, Citation1997). This is clear from the “anthropogenic climate change” discussions, whereby the authority of science is insistently contested by a range of non-experts (Latour, Citation2018, pp. 79 − 80), where “the smallest study will immediately be plunged into a full-scale battle of interpretations” (Latour, Citation2018, p. 79; cf., Citation2017, pp. 245–246). This was even more evident during the pandemic:

“[We are] not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic. Fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus, and is just as dangerous” (World Health Organization, Citation2020).

It is when the scientific authority fails (Enroth, Citation2021) that the populist discourses supply a demand for the disenchanted scientific knowledge and produce and reproduce alternative knowledges (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, Citation2017). These alternative forms of knowledge, also discussed as “pseudo-science” by Dawes (Citation2018), “troll-science” by Eslen-Ziya (Citation2020), or as “counter-science” by Ylä-Anttila (Citation2018), all brings forth the importance of studying the relationship between the populism and counter-scientific developments.

Different from the development of anti-science—opposition to science and scientific methods—pseudo-, troll-, or counter-science “denotes the growth of alternative methods for developing knowledge that oppose well-established science … (and) contest and undermine collective trust in established scientific knowledge and commonly accepted sources of expertise and competence” (Giorgi & Eslen-Ziya, Citation2022, p. 6). This form of knowledge is argued to be widespread in contemporary populist politics (Ylä-Anttila, Citation2018). In his research, Ylä-Anttila (Citation2018) has studied how populists advocate counter-knowledge. By focusing on the Finnish anti-immigrant online publics, and how they discuss and interpret events he concludes that:

[…] while often subscribing to fringe populist views, many anti-immigration activists nevertheless claim to hold knowledge, truth, and evidence in high esteem, even professing strictly positivist views, and strongly opposing ambivalent or relativist truth orientations. These communities, consisting mainly not of career politicians but ordinary people […] often employ ‘scientistic’ language and engage in popularization of scientific knowledge and rhetoric. (Ylä-Anttila, Citation2018, p. 358)

While these populist groups, he states, do not necessarily oppose expertise, they promote a new form of counter-expertise, counter-knowledge. They do this by using statistical science to define their scientific truths and to make claims to rule the society with scientific objectivity and scientific rationality. This, in turn, makes it difficult to dispute. Also, as they construct themselves, Ylä-Anttila (Citation2018) argues, they also position the scientific elite as the “corrupt research community’ or “multiculturalists [who] not just have the wrong opinions, they are delusional about reality” (Ylä-Anttila, Citation2018, p. 369). Such post-truth populism is then interconnected with the post-truth politics. The protests and tensions against COVID-19 vaccines, coupled with other contesting initiatives—such as 5 G or masks—intensified the polarisation among the scientists and the counter-knowledge producers (the anti-mask, anti-vaccine or anti-5 G groups).

According to Lasco and Curato (Lasco & Curato, Citation2019, p. 1), as “politics becomes increasingly stylised, audiences fragmented, and established knowledge claims contested, health crises have become even more vulnerable to politicisation”. Medical populism that takes hold during medical crises is, according to Lasco and Curato (Citation2019):

A political style based on performances of public health crises that pit ‘the people’ against ‘the establishment.’ While some health emergencies lead to technocratic responses that soothe anxieties of a panicked public, medical populism thrives by politicizing, simplifying, and spectacularizing complex public health issues.. (Lasco & Curato, Citation2019, p. 1)

Based on Benjamin Moffitt’s work on populism as political style, Lasco and Curato (Citation2019) define the term medical populism through three main characteristics. First, medical populism works by creating “the people” as a group that is neglected, let down or ripped off by the system (i.e., in most cases the medical expertise). According to this assumption, the failure of medical expertise in turn resulted in the crisis (Moffitt & Tormey, Citation2014, p. 391). Second, for medical populism to exist, moral panics and crises are essential. The moral panic during medical emergencies provides the necessary discourses for populists to act immediately, legitimising the populist performance of the “swiftest possible response” (Lasco & Curato, Citation2019, p. 3). The third factor that enables medical populism rests in the simplification of the political vocabulary; the simplified discourses. Such non-complexity, and directness, together with anti-intellectualism or scientific populism, create exaggerated threats to public health and safety and common-sense solutions to these threats.

This all-in return, while creating distrust of the established medicine (Trujillo & Motta, Citation2020), promotes the value of choice and taking responsibility into one’s own hands. According to Giorgi and Eslen-Ziya (Citation2022), opposing vaccinations indicates a fight for the inconvenient truth that science so far has been ignoring. At the same time, populists make promises of their own, claiming or assuming the authority to speak and act in the name of the people (Müller, Citation2017). In this sense, populism in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic is an outcome of a legitimation crisis of scientific institutions (Porpora, Citation2020).

We propose that the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the spread of false and misleading information, and distrust in vaccines, science, and scientific communities. As the COVID-19 restrictions and the measures imposed by the government increased, so did the pseudo-scientific and fake information. The level of non-scientific information went from recommendations to consume ginger tea or garlic, to rejection of the COVID-19 vaccine. Although attitudes vary by population, current research on the acceptance and refusal of the COVID-19 vaccine shows that hesitancy is a universal problem (Kucukali et al. Citation2022). According to the “Understanding Society” UK Household Longitudinal Survey (Robertson et al., Citation2021, the main reason for hesitancy was concerns about future unknown effects and lack of trust in vaccines. Some reports indicate a rise in vaccine hesitancy following the AstraZeneca vaccine safety scare across Europe and Africa (Dahir, Citation2021; Razai et al., Citation2021). This vaccine hesitancy led to an anti-vaccination movement across the world. Although not a real organised group, research has identified some common factors in the membership of this movement, including a readiness to believe conspiracy theories (Hornsey et al., Citation2020). According to Edis (Citation2020, p. 4), conspiracy theorists have the power to affect political discourses, and the advancement of digital media technologies has intensified the spread of this false information.

Conspiracy theorists are not just convinced for instance, that the United States (US) government is hiding evidence of space aliens, but they also shape the political discourse. In the US, many Republicans worry about a Deep State that schemes that blocked President Trump; or think the Trump presidency was a Russian plot. In Muslim countries, conspiracy theories about the CIA, Jews, or Freemasons are never far from the popular political imagination. And so, it goes across the globe. The internet lowers the cost of dissemination for crank notions, and the echo chambers and information bubbles promoted by social media give counter-science an ideal environment to flourish. Similarly, the conspiracy theories and misinformation have circulated widely, claiming that vaccine developments aim to microchip the population, some of these theories implicate “pharmaceutical companies—often with the complicity of government agencies and communities of scientists—in withholding from the public the ‘true’ risks of vaccination, and/or exaggerating their benefits” (Hornsey et al., Citation2020, p. 2). Even a false a false story circulated that one of the first volunteers in the Oxford University COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial had died from complicationsFootnote1 The anti-vaccination movement also actively used social media during COVID-19 pandemic to spread its messaging and aimed to reach people who are unsure about vaccines. A study of more than 500 Facebook ads between December 2018 and February 2019 found that 145 featured anti-vaccination sentiment (Jamison et al., Citation2020, p. 517).

For Eslen-Ziya (Citation2022), in addition to the information that is shared, the emotions attached to it help to amplify the importance of the message. In this process, she adds, the speed of its dissemination is also significant. In other words, she argues that the discourses that have a reference to the ideological versions become loaded with emotions and create emotional echo-chambers (Eslen-Ziya et al., Citation2019), thereby enabling their rapid distribution among and acceptance by ideologically polarised groups. Troll-scientific arguments that spread fake information and invoke arguments and ideologies become emotionally loaded and easily accepted in such circles. They become so intertwined that the rejection of troll science becomes a rejection of a doctrine; hence, no one dares to question the former without being accused of questioning the latter (Eslen-Ziya, Citation2020).

3. Emotional dynamics and networked discourse

While change-oriented social movements (such as: women’s movement, green movement) aim to foster amendment, the counter movements (such as: the anti-climate change movement, men’s movement) resist change to preserve the status quo. As these counter movements argue that social movements are disrupting their social statuses, they mobilise to “turn back the clock” (Chafetz & Dworkin, Citation1987, p. 37) and return to the old days. They form their networks both in offline but also in online spaces, via the help of digital technologies. Hence, studying these networked publics enables us to highlight the role that digital technologies play in creating new forms of social structures as well as the demands presented. As the network society allows the formation of a new social structure (Castells, Citation2004), it also starts accommodating what Papacharissi (Citation2016, p. 310) refers as “the feelings of engagement”. Here our take on such feelings of engagement will be like Boler and Davis’s (Citation2018, p. 75) conceptualization of affect and emotions where the emphasis is its relational nature. Such feelings of engagement are especially important in digital spaces where certain emotions may be triggered for the furtherance of the networked publics (Papacharissi, Citation2016).

Following Papacharissi’s (Citation2016) take on how online and offline spaces are interconnected; in this paper we argue that the online publics created, shape our life just like the offline interactions in everyday life. Hence for us the online expressions (via memes, images, or texts) provide valuable insights to the causal everyday discussions. Highlighted by scholars like McGarry et al. (Citation2019), Papacharissi and de Fatima Oliveira (Citation2012), similar to the everyday offline interactions, these network publics are activated through the use of emotions, such as feelings of solidarity and unity. It is in these online space’s that emotions like hope solidarity as well as anger or resentment help communicate and unite protestors for instance, (McGarry et al., Citation2019) in guiding and legitimizing their actions. Within this performative arena public discourses are shaped and challenged through the dissemination of views loaded with emotions, leading to what Eslen-Ziya et al. (Citation2019) refers as the emotional echo-chambers. Like the echo-chambers on social media that help gather, infer, and spread information in accordance with one’s beliefs and the emotional echo-chambers help both sharing and the intensification of emotions. In other words, emotional echo-chambers within the online platforms via the spread of both factual and emotional information reinforce the already existing views. This in return enables the social media platforms to increase or intensify the existing differences on polarized topics, leading to further polarization. As the emotional echo-chambers are created social media users stop catching not only the opposite side of the arguments, but also the emotions associated with those arguments but only focus on their views and reactions. The echoing of their own opinions and emotions in these chambers in return causes a continuous reaffirmation of their already existing views and emotions, further intensifying the link between them. In the following section we will discuss how the distrust to scientific authority has been intensified through the discourses targeting the medical personnel in Turkey is shared within these echo chambers.

4. Stimulating distrust of scientific authority—targeting of medical personnel in Turkey

Instituted in the 2000s, the healthcare reform process has been the most comprehensive of AKP’s reform projects (Dorlach, Citation2015; Yilmaz, Citation2017). The reforms unified the fragmented public health insurance schemes, including the non-contributory health insurance programme (Green Cards) for low-income groups, under the newly established SGK (Sosyal Güvenlik Kurumu—Social Security Institution). Turkey’s healthcare system is oriented towards hospital-based services. As of 2010, primary care doctors are no longer civil servants but contracted independent professionals. Rather than providing service to a specified geographical area (Aslan Akman, Citation2020), a family doctor on average is responsible for more than 3,000 patients. The absence of a referral system allows patients to skip primary care services, resulting in a disjointed system where frequent consultations occur at the second and third tier institutions and physicians experience an increased workload (Elçi, Citation2019).

According to Saglik Calisanlari Siddet Arastirmasi (Health workers violence research) (Citation2011), the workload causes long waiting times, which causes the waiting individuals to become aggressive. Full workload, not being able to spare enough time for the patient leads to the weakening of communication and trust between the doctors and the patient (2013: 66). Based on these, we argue that in Turkey, the distrust of scientific authority and the targeting of medical personnel may have occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, the governmental legitimization and the visible targeting of the medical doctors, dates to the Gezi Park Protests which began on 31 May 2013. The protest that began as a peaceful sit-in against the urban development plan to construct a shopping mall across Istanbul’s Gezi Park later became heightened when the police burned protestors’ tents and started attacking them with water cannon, plastic bullets, and tear gas. In the protests that continued for nearly two weeks, 11 people died, some lost their sight, and thousands were injured. During the protest, doctors and medical students offered an immediate medical response to the Gezi protestors in the Dolmabahçe Mosque in Istanbul. Temporary medical centres were opened at Gezi Park by volunteers to provide first aid to wounded protesters. This resulted in government action to punish the healthcare professionals for providing unlicensed healthcare services. According to the Health Minister of the time, Müezzinoğlu, even though they had planned this before the Gezi Park protests, he nevertheless believed that in view of the protests, they could see that they had made the right decision:

We prepared this regulation [to bring prison sentences to those who provide unlicensed health services] before the Gezi Park incidents. But even if we had not prepared these regulations, we saw during the Gezi incidents that we needed such a regulation, so we would have done it [after Gezi]. There is no need to hide this; this is serving the people.Footnote2

He furthermore claimed that some of these volunteers were not even healthcare professionals, but protestors trying to hide from the police. He declared that his Health Ministry would be blamed if protesters suffered complications in these centers. For one of the doctors who was at the Gezi Park the situation was however different. In a piece in the Lancet, one author commented on how concerned they were about the medical personnel being targeted by the police. They stated that they were being prevented from helping those in need and were being targeted for it:

On the ground, medical personnel have been struggling. As it became apparent that ambulances were rarely able to access the protest areas and that gas capsules were being fired en masse, my colleagues and I set up makeshift first aid stations. We used Twitter to ask medical students and personnel to help us, which worked effectively. We have seen a wide range of injuries among the protesters, particularly depressed fractures to the skull and thoracic injuries from shooting of gas capsules from close range. We also saw a patient who lost an eye after being hit by a gas capsule. Despite the atrocities around us, we continued to form more organized makeshift first aid stations, using dining tables inside cafeterias as beds. The situation became worse when the police started to target us and other makeshift first aid stations. One of our medical student volunteers is currently in intensive care after being beaten by the police. He had told the police that he was a doctor and trying to help, but they continued to beat him in front of my eyes. The police have also thrown tear gas inside the first aid stations and arrested the doctors and volunteers on the service. They are now patrolling the streets at night and selectively breaking ground-floor windows of apartments and throwing tear gas into people’s homes. They have been joined by groups of AKP sympathizers with baseball bats. (No name, Citation2013, p. 381)

For Bashirov and Lancaster (Citation2018: 1220), “AKP’s response to Gezi was directed by its concerns over its hegemonic grip over Turkish society and politics”. As the Gezi protests challenged AKP’s hegemony, instead of reconciling or listening to the demands of the protestors, AKP chose to radicalize and repress them instead. By referring to this secular, non-AKP voter segment of society as the “fifty per cent”, “hooligans”, “occupiers”, “Chapulcus” and “thugs” (all terms used by Erdoğan to describe the protestors), the government justified the use of excessive force (Amnesty International, Citation2013). Hence, not only the right to peaceful protest and assembly was denied, but all those associated with the protests and protestors were constructed as traitors, and even terrorists. As the academics, journalists, lawyers, businesses and non-governmental organizations and doctors who did not vote for them were depicted as the enemy, AKP broke ties with them completely.

As said by Uluengin (Citation2013), this was a “ghettoization’ of the secular way of life by making it publicly less acceptable. According to Özbudun (Citation2014, p. 157), Erdoğan’s recent “angry, condescending and authoritarian” and polarizing policies are to be blamed for this:

Perhaps more than the substance of the AKP’s recent policies, it is the angry, condescending, and authoritarian tone of Erdoğan’s statements that aggravates concern within the secular sectors. Similarly, majoritarian, or even plebiscitarian conception of democracy, as he has come to emphasize more and more the support of the 50 per cent behind him, ignoring the feelings of the other 50 per cent. He sees the ‘ballot box’ as the only legitimate instrument of accountability in a democracy and describes the anti-government demonstrations as an attempt by the minority to impose its will on the majority by unlawful means. (Özbudun, Citation2014, p. 157)

As a result, such attitudes greatly deepened the already existing polarization (Keyman, Citation2014; Korkut & Eslen-Ziya, Citation2018) among the religious and secular sectors of society: the AKP supporters vs. the opponents.

Coupled with the broader context of anti-elite rhetoric around the healthcare reform of the early 2000s, Erdoğan had repeatedly criticised doctors and portrayed them as “self-interested professionals” (Agartan & Kuhlmann, Citation2019). This demeaning rhetoric, the redefinition of patients as consumers and the increased workload of doctors, may have prepared the basis for an upcoming polarization. This “us vs. them” rhetoric surfaced openly during the Gezi Park protests, when the protestors were presented as selfish and irresponsible citizens. Long after the Gezi protests were suppressed and the protestors were dispersed, the polarisation remained in Turkish society, where “each pole has consistently questioned each other’s mores and aims of developmentalism” (Eslen-Ziya, Citation2020, p. 170). We believe that this is one of the factors that may indirectly amplified the assaults against the healthcare professionals in Turkey.

Although assaults and violence against health workers were not uncommon in Turkey, and 31,767 health workers were attacked between 14 May 2012 and March 2015, we argue that this portrayal of the doctors and medical students as the enemy played a significant role in the legitimisation of similar attacks in hospitals. In other words, we argue that it was during the Gezi Park protests that the roots of the stigmatisation of the medical personnel and the creation of the us (AKP supporters) vs. them (the doctors, medical students) narrative were planted. This was later followed by distrust of scientific authority and verbal abuse and threats towards the doctors. Such assaults, according to the president of the Turkish Medical Association (TTB) at the time, Dr Bayazit Ilhan, were a consequence of the AKP government’s attitudes towards the healthcare professionals:

We hear frequent statements from the prime minister and ministers that present doctors as selfish and greedy people. […] Such incendiary mix of policy and government scapegoating puts doctors and nurses squarely in the line of fire. (Smith, Citation2015, p. 643)

According to Dr Beyazit, such anti-physician discourse is also dominant among the mainstream media, who put the healthcare professionals on the spot and help to spread hate.

We argue that the portrayal of the doctors as the enemy not only increased violence towards them, but also facilitated a disillusionment and suspicion towards science and a shift of the locus of power from doctors to patients themselves (Kata, Citation2012, p. 3778). This shift of power in turn led to questioning of the legitimacy of science and authority (Annandale, Citation1998). The decline of trust in medical expertise, coupled with the development of alternative forms of science (Eslen-Ziya, Citation2021) allowing patients or lay persons to hold more power, has turned everyone into “experts” (Hobson-West, Citation2004). The conspiracy theories, and the availability of online health information, allowed like-minded groups to be supported within their closed echo chambers and conspiracy theories. We argue that this was also the case in Turkey. Before going into the details of the anti-COVID vaccination and anti-mask mobilization, and presenting the strategies used to spread their views, we will first discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic was handled under the AKP rule.

5. COVID-19 pandemic under the AKP rule

Turkey reported its first COVID-19 case on 10 March 2020.Footnote3 Before entering the normalization on 1 June 2020, Turkey had 163,942 confirmed COVID-19 cases, 127,973 recoveries and 4,540 deaths, with over 20,39,194 tests completed (The Ministry of Health, Citation2020). The policies implemented were similar to those in other countries: Public gatherings were banned, and schools were closed and switched to remote teaching. Businesses were encouraged to work remotely. Later, international and domestic flights were cancelled between mid-March and early April. On 21 March, a curfew was imposed on everyone over the age of 65.Footnote4 On 3 April 1931 major cities were sealed off and a curfew for people under the age of 20 was imposed. Starting from 18 April and running until 1 June,Footnote5 a full lockdown was imposed on weekends and holidays.

In addition, a Coronavirus Scientific Advisory Board (In Turkish: Koronavirüs Bilim Kurulu) was formed on 10 January 2020Footnote6 by a group of medical scientists set up by the Ministry of Health to develop measures to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The board drew up guidelines for the medical treatment and measures to be followed by the public and updated them according to the disease’s course in the country. The Coronavirus Scientific Advisory Board reported to the Minister of Health and the measures were implemented by the government. While experts were consulted, critical non-state organizations, local governments and opposition parties were not incorporated into this process.Footnote7

While the population experienced strict COVID-19 measures, the AKP government allowed for some flexibility for cases that served their populist agenda. In July, for instance, hundreds of thousands of people joined in the first prayers after the historic Hagia Sophia was converted from a museum into a mosque. Over the years, this conversion of Hagia Sophia had been a highly debated topic and its opening for mass prayers for Muslims was portrayed as an accomplishment of the AKP regime. While the government allowed the gathering at Hagia Sophia, all outdoor activities such as concerts and weddings were banned. That decision was postponed for two days, however, reportedly because AKP was holding an indoor meeting to celebrate its new party members.Footnote8 Hence, though attendance of weddings and funerals was limited to 30 people, government officials attended crowded funerals, and their own party rallies. In the meantime, the pandemic was used as an excuse to ban protests. Economic limitations and the populist nature of policymaking clearly dictated the lockdown’s features, as in the earlier stages of the pandemic. A gradual normalisation began on 17 May 2021, with the relevant circular laying out the restrictions issued.Footnote9

Some scholars indicated that Turkey made a quick response and implemented several strategic policy tools (Bakir, Citation2020; Kemahlıoğlu & Yeğen, Citation2021), and that Turkey weathered the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis relatively successfully. Death rates were relatively low, and the healthcare system was not overwhelmed by the growing number of cases. Different factors seemed to have contributed to this outcome. Compared to the European average, Turkey has a much younger population, and almost all the population had access to healthcare. Turkey’s healthcare system is oriented towards hospital-based services. City hospitals have been constructed in major cities and the financing of these projects with foreign currency loans has been the target of much criticism (Pala et al., Citation2018). Operational since 2017, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Turkey had ten such hospitals with an average capacity of 1,417 bedsFootnote10 (Transparency International Turkey, Citation2020).

Although the COVID-19 infection rates appear lower than for the rest of Europe, there was a belief among the population that the government was not disclosing the actual numbers. This raised concerns in the public and international institutions about the true scale of the outbreak in the country, and eventually led to questioning of the reliability of the official number of COVID-19 virus-related deaths (Kisa and Kisa Citation2020; Yilmaz, Citation2021).

Regarding vaccination policy, the Ministry of Health in Turkey used the Sinovac vaccine, manufactured in China, for the first few months. People aged over 65 wishing to be vaccinated received two doses of Sinovac up to the spring of 2021. After the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine become widely available to Turkish citizens in April 2021, large-scale vaccination began. By October 2021, more than 88% of the population had received a single dose, while 76% had received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.Footnote11

From anti-vaccine protests, to opposers to the vaccine for potential ludicrous side effects, to large-scale WhatsApp messages focusing on the vaccines, the public was bombarded with misinformation and conspiracy theories. At the beginning of the outbreak, conspiracy theories about the source and potential effects of the pandemic were widespread (e.g., coronavirus is a bioweapon; the global elite has designed the virus to take control of the world; Seker et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, Turkey had reached the last stage of its COVID-19 vaccine production. This was an inactive vaccine, like Sinovac, and drew criticism for being not proven safe and effective by TTB. Later, when Erdoğan called members of the TBB “fraudsters” and “liars” for questioning the Turkish COVID-19 vaccine, TTB doubled down, saying that it only issued warnings based on scientific evidence.Footnote12

6. Methods

6.1. Tweet body

To study the Anti-COVID vaccine activist groups in Turkey and their online and offline activism , the tweets under the hashtags #asımağdurlarıFootnote13 #AsıVePcrDurdurulsunFootnote14 #HerYerMaltepeHerYerDirenişFootnote15 were collected along with the news articles discussing COVID-19 protests or hesitancy. The plugin, belonging to the NVivo software allowed us to capture and export conversations on Anti-COVID vaccine activist groups on Twitter using the above-mentioned hashtags. Once the tweets were captured NCapture created a file and imported it to NVivo. After eliminating the duplicate tweets we analysed the remaining tweets discursively. For the twitter data analyses we took Kim et al.’s (Citation2018) methodological approach of simple random sampling. Their research showed that simple week sampling was informative and representative enough. Though we are aware of the limitations of the claims of “truth” made via the analyses of the captured data from Twitter (Mahrt et al., Citation2014 and Caliandro, Citation2018) we believe this data provides a sense of user’s practices, and their construction of reality, and their attitudes towards vaccination.

6.2. Online News

The news sites were constantly active and detailed about COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic. This enabled us to compare the content of the collected tweets with online news about vaccine hesitancy. Thus, we relied on two news sites; T24 and teyit.org which provides a compilation of different news sources differ in opinion the reason behind preferring these news sites is that they are companies that operates only on the Internet and is not part of large institutions.

We evaluated news about COVID vaccine hesitancy starting from 12 December authorities stated that the vaccine will arrive in Turkey on 11 December 2021 to 30 December 2021 (the period that the pandemic is relatively eased; obligations were loosened). We used news about vaccine hesitancy to cross check anti-COVID-19 vaccine mobilization movements to better understand and evaluate their attitudes towards vaccine developments. When the contents of the shared news are evaluated by the authors, certain keywords and themes came out as a guidance for content analysis of the Tweet body.

6.3. Content analysis

Once the authors agreed on the common key words in Table and themes listed in Table , the selected excerpts were translated into English. During the translation process, our ethical approach for working with Twitter data was borrowed from Williams, Burnap and Sloan (Citation2017: 1162): “composing of new original not traceable back to an identifiable individual or interaction” and only paraphrases of these quotes were used. Furthermore, to protect the anonymity of the creators of each tweet, potentially identifying information such as usernames, locations, their bios were removed.Footnote16 This way we made sure that no direct quote will take the readers/onlookers to the original post shared on Twitter (Eslen-Ziya, Citation2022). Coding was done using Clark’s (Citation2016, p. 235) “expressions of a movement’s goal” perspective where tweets act as a political expression. For us the analyses of the anti-COVID online mobilisation helped us group the dominant discourses appearing.

Table 1. Vaccine hesitancy

Table 2. The strategies used by the COVID-19 vaccine deniers in Turkey

The thematic analysis of the tweets revealed three main categories: i) “My body, my choice”; ii) Denying/Devaluing/Shifting science’; and iii) Dismissing/Attacking alternative views (see, Table for all categories emerging from the captured tweets). The themes that arose from the analysis allowed us to formulate the anti-COVID vaccination discourses emerging (also presented in Table ). Some of these concerned how they viewed the situation, and how they defined themselves, while others defined what they were fighting against. These categories formed the basis for the organisation of the results section. Such an approach is defined as a “pragmatic, ‘tailor made’ qualitative analysis, informed by several sources, including variations of thematic and grounded approaches (see, Charmaz, Citation2006), as well as Carol Bacchi’s, (Citation2009; Citation2015; Bacchi & Goodwin, Citation2016) problematization approach” (Eslen-Ziya & Bjørnholt, Citation2022, p. 5).

7. Results

Even though vaccination hesitancy is not a new phenomenon in Turkey, the mistrust of scientific expertise and AKP’s strategy to create alternative scientific knowledge to support the party’s ideologies is relatively recent (for more information on the creation of distorted scientific arguments to create narratives of the concept of gender equality, see Eslen-Ziya Citation2021). The anti-COVID vaccination movement, we argue, influenced by President Erdoğan’s disdain for doctors and medical experts, denigrated scientific information and expert opinion, while simultaneously lending scientific validity to their theories that the COVID-vaccine is harmful, or masks are useless. To understand the fundamental arguments of anti-vaccine groups first we examined online news about vaccine hesitancy. 115 news were detected from T24 and teyit.org and major themes and keywords were selected to discover the demands (narratives) of the anti-COVID vaccine groups and their strategies of mobilization and lobbying. Also, to uncover how Twitter is used to communicate about anti-COVID vaccination in Turkey we closely examined their online (and offline strategies). As presented in Table , our analyses revealed three main strategies: the construction of themselves (us), and what they are against (them); followed with their reasons for rejection or devaluing of scientific evidence while promoting counter scientific arguments to support their views; and lastly, their reaction towards the “other”—those who chose to be vaccinated.

8. This is my body, and we are against!

“My body, my choice” as the slogan that so far has been used by feminist activists concerning issues of bodily autonomy and abortion was now being recycled by the COVID-19 vaccine opponents). They believed that the COVID-19 vaccine mandate and the restrictions imposed by the government were all violations of individual rights and freedoms.

Naming themselves as the victims of the vaccine, they protested:

I’m a free individual, I’m not the dog of the American or foreign powers! If they want to be a lot, they can have vaccine followers! Not me! #asımağdurları #AsıVePcrDurdurulsun #HerYerMaltepeHerYerDireniş

For the protestors, the mandatory vaccine created a subserviency whereby their freedom of movement was dependent on the vaccination. They emphasised that if they were not vaccinated, they would not be able to travel or, in some cases, go to work. This in turn made them anxious about losing their jobs and they shared example cases from abroad as a warning: “Vaccine mandates: I lost my job for being unvaccinated”:

“Those who were not vaccinated were fired. He couldn’t go to school. Cinema theater stadium etc. could not enter. Couldn’t get on public transport etc.” (8 March 2022).

After mobilisation via the #HerYerMaltepeHerYerDireniş (everywhere is Maltepe,Footnote17 everywhere is resistance) hashtag on 26 September 2021, thousands gathered at the rally called the “Great Awakening”. The “Fixed Earth Human Development Movement” was among the groups protesting COVID vaccines, as well as the global conspiracy. Some were against the coronavirus-related mandates and restrictions, as well as vaccinations, PCR tests and masks, while others were there to protest Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, who became the top target for various conspiracy theories.

They shouted:

“We are here to stand against global conspiracies. We are here to stand against Bill Gates”; “No chips, no masks”; “Let everyone know we won’t become slaves!” (Al-Monitor 13 September 2021Footnote18).

For the protestors, the COVID-19 vaccine is solely designed to increase the revenue of the major pharmacological companies.

Their demand was for the World Health Organization’s Ankara office to be closed, and for PCR testing and mandatory masks to be lifted. They were against the long queues and PCR testing:

Date:13.09.2021 Place: Göztepe State Hospital … Healthy people are in the PCR queue at this hour of the night to prove themselves … Persecution … #HerYerMaltepeHerYerDirenis

9. Denying/devaluing/ shifting science

When the contents of the shared news are evaluated, major theme were claims that there are many people who lost their lives related to the vaccine referring to international news sources, such as “Brazilian doctor died due to vaccine”,Footnote19 “Vaccination-related deaths are experienced in Germany, also referring to national fake information; “people will be microchip implanted”, “vaccines cause infertility”.Footnote20 There is a variety of conspiracy theories and false news that the vaccine causes many diseases, “vaccines fallacies” that it will degrade human DNA” are since vaccines are found very quickly.Footnote21 As for the Tweet analysis, one of the dominant discourses was of men being left infertile due to the “dangers”, or side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine. The misinformation that the vaccine could lead to infertility was widely believed among the anti-COVID vaccine protestors. Under the “big game” hashtag, when talking about the possible side effects, they twitted:

# There is a big game in COVID anyway, I know this like everyone else, maybe even the Chinese vaccine can make a man sterile, even insufficient only makes it vicious.

Others used troll-scientific evidence to prove their points:

#MRNA injections in women are disrupting the mechanism of menstrual cycle … It was already shown in the Japanese report that the lipid nanoparticles that surround the outside of the mRNA are mostly collected in the ovaries after the injection.

# There is a big game in COVID. And this can lead to infertility.

Another claim that was frequently tweeted was the misinformation that the COVID vaccine caused impotence and that once vaccinated, their testicles would become swollen.

# What do you think is the truth of the COVID vaccine causing impotency? I would not get a vaccine if I don’t know the content, anyway.

Such plots may in turn have led them to be even more reluctant to take the vaccine, and particularly when these conspiracy theories were coupled with a negative reaction towards the doctors—what they referred as the white coup—this intensified the mistrust towards the vaccine:

But you can’t get away by saying the ministry told us to go get vaccinated. If it is with the law, if not with the law, we will hold you accountable at the cost of our lives. We will pass your white coup to your head. #HerYerMaltepeHerYerDireniş

They also shared counter-scientific information from Steve Kirsch. who promoted himself as an entrepreneur and technology export and argued that vaccines caused more deaths than cures. His false claims stated during the public comment period of a U.S. Food and Drug Administration Committee meeting on 17 September were used as evidence by the anti-vaccine supporters in Turkey. The () below a screenshot of a news article—stating that the COVID vaccine was killing people was widely shared among the anti-vaccine protestors.

Image 1. A widely tweeted screenshot of a news article stating that it is now proven that COVID vaccine kills more than it is saves lives.

His presence at the Food and Drug Administration Committee meeting portrayed him an FDA expert. They tweeted, “it is not us, the FDA experts saying it” and this was widely tweeted. They described their protest as a big achievement where by disobeying the COVID-19 rules they become one powerful unit:

Tens of thousands at once, we will not accept! We will get together again with all our enthusiasm!! #HeryerMaltepeHerYerDireniş

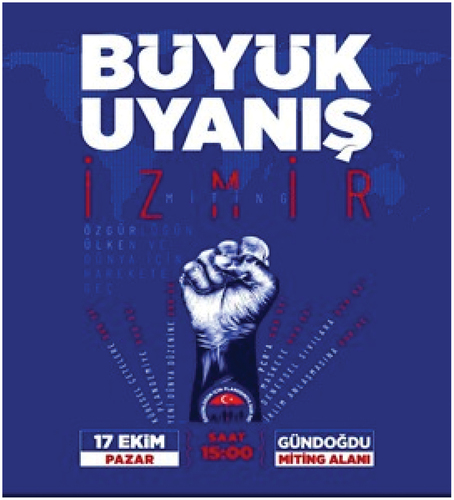

They called rallies such as Big Awakening, Büyük uyanış, and organised them in three major cities: Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir. The poster below, that called for participation in the Izmir rally and was widely shared, read: “Take action for your freedom, your country and the world”. The poster further read:

“Say no to global gangs, pandemic, new world order, PCR tests, masks, experimental fluids, climate agreement.”

In this slogan, they defined the vaccine as the “experimental fluid”. The term not only constructed the vaccine as an ordinary fluid, but also as experimental, which made it risky and untrustworthy. Hence, in their tweets they linked the anti-COVID-19 vaccine protests to wider unrest:

Do not think that our problem is the vaccine, this is humanity’s war of freedom #HeryerMaltepeHerYerDireniş

They demanded that the scientific board be shut down:

# Scientific board should be shut down immediately #HeryerMaltepeHerYerDireniş

10. Dismissing/attacking alternative views

When starting this study, we expected a relationship between some conspiracy theories and right-wing populism, which typically involves a belief that amoral elites are exploiting ordinary people for their own self-interest (Forgas & Crano, Citation2021). For instance, during the pandemic, France had highest levels of vaccine hesitancy in the world, 44% of those who voted for Marine Le Pen in the 2017 presidential election expressed concerns about vaccines compared with 25% who did not vote and 12% of those who voted for Emmanuel Macron.Footnote22 In Italy, supporters of the anti-establishment populist Five Star Movement, which has in the past promoted anti-vaccine propaganda,Footnote23 were more likely than voters of other major parties to doubt the scientific consensus. Thus, this examination confirmed our argument about the possible relatedness of conspiracy theories and populist politics. As for Turkey, while using troll-scientific evidence to prove their points, the anti-vaccination online community was attacking, censoring or dismissing scientific evidence with which they disagreed. For instance, a highly conservative journalist shared a tweet misinterpreting a scientific news article stating that COVID-19 caused infertility:

Both the COVID vaccine and the cause of infertility. Well, what have we been saying for years? You were expecting at least 3 children, right? The eugenics and their collaborators are getting the job done. You run towards what you thought you were running from.

When people accused him of spreading fake information and misinforming the public, he did not delete his tweet or reply, but just dismissed them.

11. Discussion

Scientific facts tend towards the collective. Science is categorical and pluralistic as it situates authority not with any one person or type of person, but in the content-oriented evidence. However, when the scientific facts are shown it also creates a certain power/authority restored by the soundness of the evidence. If the evidence-based results change frequently, the authoritative image of the science is also devalued. In this study, we argued that anti vaccine movement is also a manifestation of an anti-science stance scorn for any epidemiological data a generalized repudiation of expertise. As it is in other parts of the world, Anti-COVID vaccine mobilization in Turkey enabled us to test our argument as the counter-movement emerged in Turkey to challenge scientific discourse and research results. The quest for alternative knowledge served to echo practical personal experience with emotions for some people. A change in knowledge becomes inevitable within the COVID-19 pandemic, and hence the shifting scientific discourse encourages people to “absorb processes which render them vulnerable” (Blokker & Vieten, Citation2022, p. 5) and causes difficulties with emotionally managing and leading them. For instance, as they protested the vaccine, they talked about their fears of losing their jobs, or becoming infertile due to the vaccine’s side effects. Applying Eslen-Ziya et al.’s (Citation2019) emotional-echo-chamber theory, we showed that when troll-scientific knowledge becomes loaded with emotions, they begin uniting and connecting people with similar views. As they organised and protested in three major Turkish cities, they used the anti-science misinformation and conspiracy theories to discursively frame and interpret their demands: No to vaccines, PCR tests and masks. Furthermore, the backlash regarding the mandates reflected a medical populism (Lasco & Curato, Citation2019) that was shaped way back during the Gezi Park protests. AKP’s creation of the “the people” as a group that is neglected, let down or ripped off by the medical expertise, and the construction of such expertise as the looters and irresponsible citizens during and after the Gezi Park protests, may not only facilitated violence towards medical personnel at the hospitals, but also fuelled mistrust towards them and their advice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, based on this assumption, the failure of medical expertise in turn resulted in the crisis (Moffitt & Tormey, Citation2014, p. 391).

Such distrust of established medicine (Trujillo & Motta, Citation2020) in turn promoted the value of choice and taking responsibility into one’s own hands and led to anti-COVID vaccination protests and vaccine hesitancy. As Giorgi and Eslen-Ziya (in press) also argued, opposing vaccinations indicated a fight for the inconvenient truth that science had so far been ignoring.

12. Conclusion

Our paper seeked to highlight the discourses concerning COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, as well as their mobilization on one of the most widely used social media platforms in Turkey—Twitter along with the news regarding anti-vaccine arguments from two selected online news sites. Our qualitative content analysis revealed three major themes, which were referred to as strategies by the COVID-19 vaccine deniers in Turkey to disseminate their views. As presented in Table , these were: first the emphasis on bodily freedom and personal choice and the use of “my body my choice” rhetoric; secondly the denying, devaluing, and shifting of scientific evidence; and lastly, the dismissal and/or attacking of alternative views and deepening of the polarization between the followers of the COVID-19 restrictions, vaccine supporters and deniers. We found a link between the distrust of doctors and the anti-vaccination ideas, and the quest for alternative knowledge and expert authority confirming the examples in FranceFootnote24 and Italy.Footnote25

Our results furthermore showed that the tweets were not only used to spread conspiracy theories about what the vaccine was made of, but also suspicion of the major pharmaceutical companies and their financial, rather than health-related, motives for developing vaccines. This was most evident from the mistrust towards Bill Gates and the microchip conspiracy. The mistrust of science, fuelled with counter-scientific knowledge, was evident from the belief regarding possible causes of male infertility. We therefore conclude our paper by emphasizing the urgent need for a vaccine communication plan to reduce misinformation and help rebuild the trust in medical expertise.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of all healthcare professionals who died in the course of their duties.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hande Eslen-Ziya

Hande Eslen-Ziya, Professor of Sociology at the University of Stavanger and director of the Populism, Anti-Gender and Democracy Research Group at the same institution. She has an established interest in gender and social inequalities, transnational organizations and social activism. She recently co-edited Populism and Science in Europe (2022, Palgrave Macmillan) which provides a systematic and comparative analysis of the intersections of populism and science in Europe, from the perspective of political sociology.

Ezgi Pehlivanli

Ezgi Pehlivanli holds a PhD from Middle East Technical University (METU), Department of Sociology. She taught Gender and Social Theory at the Research Center for Science and Technology Policy Studies, METU between 2016-2022. She was a postdoc fellow at Lund University, Department of Gender Studies in 2018. Pehlivanli Kadayifci is currently a postdoc fellow at the University of Stavanger, Department of Media, Culture and Social Sciences. Her research interests are feminist science and technology studies, gender, body, science discourse, political sociology discursive politics, and populism.

Notes

1. World Health Organization. Immunization coverage. 6 December 2019. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage. Accessed on 18.09.2022

2. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/health-regulation-planned-before-gezi-protests-turkeys-health-minister-says-59389 Accessed on: 06.05.2022.

3. Ministry of Health, Republic of Turkey (MoH-TR) COVID-19 website of the Republic of Turkey. Ministry of Health; https://COVID19.saglik.gov.tr Accessed on 10.05.2022.

4. COVID-19 pandemic—Turkey (global-monitoring.com) Accessed on 10.05.2022.

5. How has Turkey done in its fight against COVID-19? The jury is still out | LSE COVID-19 Accessed on 10.05.2022.

6. Turkey’s science boards lead struggle against COVID-19| Daily Sabah Accessed on 10.05.2022.

7. Turkey’s science boards lead struggle against COVID-19| Daily Sabah Accessed on 10.05.2022.

8. Turkey: Istanbul authorities introduce COVID-19 social gathering restrictions September 12 /update 33 | Crisis24 (garda.com) Accessed on 10.05.2022.

9. Announcements—UNHCR Turkey Accessed on 10.05.2022.

10. Turkey—Transparency.org Accessed on 10.05.2022

11. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health (saglik.gov.tr). Accessed on 10.05.2022

12. Turkish Medical Association slams President Erdoğan following insults: “Our only reference is science” (duvarenglish.com) Accessed on 10.05.2022.

13. Vaccine victims.

14. Stop the vaccine and PCR.

15. Everywhere is Maltepe everywhere is resistance.

16. NSD https://www.nsd.no/en was consulted during this process.

17. Maltepe is a district on the Asian side of Istanbul.

18. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2021/09/anti-vaxxer-turks-protest-bill-gates-istanbul-rally Accessed on: 2.03.2022.

19. AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine trial Brazil volunteer dies, trial to continue | Reuters Accessed on 19.09.2022

20. Uzmanlardan, Yeni Akit yazarı Dilipak’a yanıt: Aşı karşıtlığının bilimsel bir temeli yok; her tür komplo teorisi, “şizofrenik yaklaşım” olur (t24.com.tr) Accessed on 19.09.2022

21. Araştırma: Aşı karşıtı hareket Instagram etiketleriyle yayılmaya devam ediyor—Teyit Accessed on 19.09.2022

22. Revealed: populists far more likely to believe in conspiracy theories | Vaccines and immunisation | The Guardian Accessed on 19.09.2022.

23. How Italy’s “digital populists” used the anti-vaccine agenda to propel themselves into power—Political Critique Accessed on 19.09.2022.

24. Revealed: populists far more likely to believe in conspiracy theories | Vaccines and immunisation | The Guardian Accessed on 19.09.2022.

25. How Italy’s “digital populists” used the anti-vaccine agenda to propel themselves into power—Political Critique Accessed on 19.09.2022.

References

- Agartan, T. I., & Kuhlmann, E. (2019). New public management, physicians and populism: Turkey’s experience with health reforms. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(7), 1410–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12956

- Amnesty International. (2013). Turkey: Gezi park protests.

- Annandale, E. (1998, April 22). The sociology of health and medicine: A critical introduction. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press.

- Arendt, H., & Kohn, J. (2006). Between past and future. Penguin.

- Aslan Akman, C. (2020). Gender politics under authoritarian populism in Turkey: From the equal rights agenda to an anti-gender strategy. Populism,Gender and Feminist Politics: Between Backlash and Resistance, Florence, İtalya. https://www.sns.it/sites/default/files/20201210-11locandina.pdf

- Babich, B. (2021). Pseudo-science and ‘fake’news:‘Inventing’ epidemics and the police state. In I. Strasser (Ed.), The psychology of global crises and crisis politics-intervention, resistance (pp. 241–272). Singapore: Springer.

- Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy. Pearson Higher Education AU.

- Bacchi, C. (2015). The turn to problematization: Political implications of contrasting interpretive and poststructural adaptations.

- Bacchi, C., & Goodwin, S. (2016). Poststructural policy analysis: A guide to practice. Springer.

- Bakir, C. (2020). The Turkish state’s responses to existential COVID-19 crisis. Policy and Society, 39(3), 424–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783786

- Bashirov, G., & Lancaster, C. (2018). End of moderation: The radicalization of AKP in Turkey. Democratization, 25(7), 1210–1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1461208

- Blokker, P., & Vieten, M. (2022). Fear and uncertainty in late modern society. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 9(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2022.2033461

- Boler, M., & Davis, E. (2018). The affective politics of the “post-truth” era: Feeling rules and networked subjectivity. Emotion, Space and Society, 27(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.03.002

- Caliandro, A. (2018). Digital methods for ethnography: Analytical concepts for ethnographers exploring social media environments. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 47(5), 551–578.

- Castells, M. (Ed.). (2004). The network society: A cross-cultural perspective. Northampton, MA: Edward Edgar.

- Chafetz, J. S., & Dworkin, G. (1987). In the face of threat: Organized antifeminism in comparative perspective. Gender & Society, 1(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124387001001003

- Charmaz, K. (2006). The power of names. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 396–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241606286983

- Clark, R. (2016). “Hope in a hashtag”: The discursive activism of# WhyIstayed. Feminist Media Studies, 16(5), 788–804.

- Dahir, A. L. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy runs high in some African countries, in some cases leaving unused doses to expire. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/16/world/vaccinehesitancy-africa.html

- Dawes, G. W. (2018). Identifying pseudoscience: A social process criterion. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 49(3), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-017-9388-6

- Dorlach, T. (2015). The prospects of egalitarian capitalism in the global South: Turkish social neoliberalism in comparative perspective. Economy and Society, 44(4), 519–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2015.1090736

- Edis, T. (2020). A revolt against expertise: Pseudoscience, right-wing populism, and post-truth politics. Disputatio, 9(13). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3567166

- Elçi, E. (2019). The rise of populism in Turkey: A content analysis. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 19(3), 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2019.1656875

- Enroth, H. (2021). Crisis of Authority: The Truth of Post-Truth. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 1–17.

- Eslen-Ziya, H. (2020). Right-wing populism in New Turkey: Leading to all new grounds for troll science in gender theory. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 76(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i3.6005

- Eslen-Ziya, H. (2021). Discursive Construction of Population Politics: Parliamentary Debates on Declining Fertility Rates in Turkey. Tidsskrift for Kjønnsforskning, 45(2–03), 127–140.

- Eslen-Ziya, H. (2022). Humour and sarcasm: Expressions of global warming on Twitter. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01236-y

- Eslen-Ziya, H., & Bjørnholt, M. (2022). Men’s rights activism and anti-feminist resistance in Turkey and Norway. In Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society. State and Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxac011

- Eslen-Ziya, H., McGarry, A., Jenzen, O., Erhart, I., & Korkut, U. (2019). From anger to solidarity: The emotional echo-chamber of Gezi park protests. Emotion, Space and Society, 33(2019), 100632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2019.100632

- Forgas, J. P., & Crano, W. D. (2021). The psychology of populism: The tribal challenge to liberal democracy. In The psychology of populism (pp. 1–19). Routledge.

- Giorgi, A., & Eslen-Ziya, H. (2022). Populism and science in Europe. In Populism and Science in Europe (pp. 1–24). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hekman, S. (1997). Truth and method: Feminist standpoint theory revisited. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 22(2), 341–365.

- Hobson-West, P. (2004). The construction of lay resistance to vaccination. In I. Shaw & K. Kauppinen (Eds.), Constructions of health and illness: European perspec-tives (pp. 89–106). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Hornsey, M. J., Finlayson, M., Chatwood, G., & Begeny, C. T. (2020). Donald Trump and vaccination: The effect of political identity, conspiracist ideation and presidential tweets on vaccine hesitancy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 88, 103947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103947

- Jamison, A. M., Broniatowski, D. A., Dredze, M., Wood-Doughty, Z., Khan, D., & Quinn, S. C. (2020). Vaccine-related advertising in the Facebook ad archive. Vaccine, 38(3), 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.06631732327

- Kata, A. (2012). Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm–An overview of strategies and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine, 30(25), 3778–3789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112

- Kemahlıoğlu, Ö., & Yeğen, O. (2021). Surviving the COVID-19 pandemic under right-wing populist rule: Turkey in the first phase. South European Society & Politics, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2021.1985497

- Keyman, E. (2014). The AK party: Dominant party, new Turkey and polarization. Insight Turkey, 16(2).

- Kim, H., Jang, S. M., Kim, S. H., & Wan, A. (2018). Evaluating sampling methods for content analysis of Twitter data. Social Media+ Society, 4(2), 2056305118772836.

- Kisa, S., & Kisa, A. (2020). Under‐reporting of COVID‐19 cases in Turkey. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 35(5), 1009–1013.

- Korkut, U., & Eslen-Ziya, H. (2018). Politics and gender identity in Turkey: Centralised Islam for socio-economic control. Routledge.

- Küçükali, H., Ataç, Ö., Palteki, A. S., Tokaç, A. Z., & Hayran, O. (2022). Vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination attitudes during the start of COVID-19 vaccination program: A content analysis on twitter data. Vaccines, 10(2), 161.

- Lasco, G., & Curato, N. (2019). Medical populism. Social Science & Medicine, 221(January), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.006

- Latour, B. (2017). Facing gaia: Eight lectures on the new climatic regime. John Wiley & Sons.

- Latour, B. (2018). Down to earth: Politics in the new climatic regime. John Wiley & Sons.

- Mahrt, M., Weller, K., & Peters, I. (2014). Twitter in scholarly communication. Twitter and Society, 89, 399–410.

- McGarry, A., Jenzen, O., Eslen-Ziya, H., Erhart, I., & Korkut, U. (2019). Beyond the iconic protest images: The performance of ‘everyday life’on social media during Gezi Park. Social Movement Studies, 18(3), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1561259

- McIntyre, L. (2018). Post–truth. Mit Press.

- Ministry of Health, Republic of Turkey (MoH-TR). (2020). COVID-19 web page of the Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr

- Moffitt, B., & Tormey, S. (2014). Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies, 62(2), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12032

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Müller, J. W. (2017). What is populism? Penguin UK.

- No name. (2013). During Turkish protests, medical personnel targeted. Lancet, 381(9883), 2067. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61223-4

- Özbudun, E. (2014). AKP at the crossroads: Erdoğan’s majoritarian rift. South European South European Society and Politics, 19(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2014.920571

- Pala, K., Erbaş, Ö., Bilaloğlu, E., Ilhan, B., Tükel, M. R., & Adıyaman, S. (2018). Public Private Partnership in Health Care Case of Turkey. World Medical Journal 64(4).

- Papacharissi, Z. (2016). Affective publics and structures of storytelling: Sentiment, events and mediality. Information, Communication & Society, 19(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1109697

- Papacharissi, Z., & de Fatima Oliveira, M. (2012). Affective news and networked publics: The rhythms of news storytelling on #Egypt. Journal on Communications, 62(2), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01630.x

- Popper, K. (2005). The logic of scientific discovery. Routledge.

- Porpora, D. V. (2020). Populism, citizenship, and post-truth politics. Journal of Critical Realism, 19(4), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2020.1800967

- Razai, M. S., Osama, T., & Majeed, A. (2021). Covid-19 vaccine adverse events: Balancing monitoring with confidence in vaccines. BMJ Opinion, 373(May), n1138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1138

- Robertson, E., Reeve, K. S., Niedzwiedz, C. L., Moore, J., Blake, M., Green, M., Katikireddi, S. V., & Benzeval, M. J. (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 94, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008pmid:33713824

- Saglik Calisanlari Siddet Arastirmasi, 2011. Saglik-Sen: Ankara. fbda8576fd0d6d6de70f52f76b914672.pdf (sagliksen.org.tr)

- Seker, M., Ozer, A., & Korkut, C. (2020). Reflections on the pandemic in the future of the world. Turkish Academy of Sciences Publications.

- Shearmur, J. (2002). The political thought of Karl Popper. Routledge.

- Smith, M. (2015). Rise in violence against doctors in Turkey, elsewhere. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 187(9), 643. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5062

- Transparency International Turkey (2020) ‘Şehir Hastaneleri [City Hospitals]’, available online at: http://www.seffaflik.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/percentC5percent9EehirHastaneleri.pdf

- Trujillo, K. L., & Motta, M. (2020). Why are wealthier countries more vaccine skeptical?: How internet access drives global vaccine skepticism. Preprint - APSANet. Available at: https://preprints.apsanet.org/engage/api-gateway/apsa/assets/orp/resource/item/5f46a5fd15d7ef00123a4011/original/why-are-wealthier-countries-more-vaccine-skeptical-how-internet-access-drives--global-vaccine-skepticism.pdf

- Uluengin, H. (2013, June 17). Gezi’nin Ortak Paydası [Gezi’s common denominator]. Taraf.

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., & Sloan, L. (2017). Towards an ethical framework for publishing Twitter data in social research: Taking into account users’ views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology, 51(6), 1149–1168.

- World Health Organization. Immunization coverage. 6 December 2019. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage

- World Health Organization. (2020, February 15). Munich security conference. WHO. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/munich-security-conference

- Yilmaz, V. (2017). The politics of healthcare reform in Turkey. Springer International Publishing.

- Yilmaz, I. (2021). erdogan’s political journey: From victimised muslim democrat to authoritarian, islamist populist. European Center for Populism Studies.

- Ylä-Anttila, T. (2018). Populist knowledge:‘Post-truth’ repertoires of contesting epistemic authorities. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 5(4), 356–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2017.1414620