Abstract

COVID-19 has had a negative effect on tourism activity, highlighting the dependence that many places have on it. Planners and managers have denounced the situation and have addressed it according to their interests: for or against regrowth as a means to overcome this crisis. The academic debate is focused on this polarisation and the possibility that this crisis constitutes an opportunity for change towards a degrowth approach in tourism. However, this approach is not adopted by politicians, entrepreneurs or the media. To confirm this hypothesis, we conducted a study focused on Spain, as it is an important international destination. We have used qualitative analysis tools in order to measure frequencies and construct semantic networks. We have analysed 2,440 written press articles on tourism in Spain, published in newspapers between 1st March and August 31st, 2020. The results confirm that the news items provide an x-ray of the events and constitute a means for transmitting the economic and reactivation discourse pro-re-growth defended by the interest groups.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 health crisis has given rise to an economic crisis similar to the Great Recession of 2008, essentially derived from the reduction in the supplies necessary for production and the lockdown which prevented the development of activities that workers could not perform remotely from their homes (Torres & Fernández, Citation2020). COVID-19 has affected all sectors of the economy, hitting the tourism industry particularly hard. This sector has been acknowledged as being one of the most vulnerable to disasters (Biggs et al., Citation2012; Gössling et al., Citation2020; Hall, Citation2010) and, on this occasion, the effect has been severe due to the reduction in the mobility of the population. The pandemic led to almost total restriction of leisure activities during 2020 and a good part of 2021 (Huertas et al., Citation2020). The global impact has been particularly dramatic in Spain which has recorded high death rates.

This unexpected global situation has altered the dynamics of tourism in recent years in many countries, especially in Spain, within which there have been two models: Overtourism, which particularly affected consolidated destinations (large cities and sun and beach destination), generating an obsolete model, excessively dependent and saturated; and undertourism in emerging destinations, usually in the interior of the country (Pons et al., Citation2020), which had been seeking strategies of adaptation and promotion to attract tourists and diversify their sources of income and, as a result, secure the population (Blanco-Romero & Blázquez-Salom, Citation2021). Proximity tourism has shown its potential in those destinations characterised by undertourism (Cañada & Izcaga, Citation2021).

Tourism, in general, is a topic that the media address regularly, both in news pieces that report the situation of different territories and opinion pieces in accordance with the editorial line of the media. However, no analysis has been made in the media of the overtourism and undertourism processes, even though the news provides an x-ray of what is happening. These news pieces constitute a means to transmit the discourse of the institutions and interest groups, which select the information that they wish to convey to society, generating a climate of favourable opinion towards the strategies that they wish to promote.

Analysing the content of the news items can help to establish the diversity of the positioning of the interest groups and study their media influence and their generation of political discourses (Van Dijk, Citation1998). This research focuses on the case of Spain, which has been one of the most relevant international tourist destinations for decades, where the overtourism/undertourism duality is especially notorious. This study has several objectives: The first is to determine the quantitative evolution of the media coverage of the phenomenon, in order to measure the importance given and to qualitatively identify the topics and generate the taxonomies on which the discourse is focused at a given moment. The second is to identify the discourses generated by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. And the third objective is to determine the political implications, relating them to the interest groups involved in the tourism phenomenon in different geographical areas.

This leads to the following hypotheses:

1. In relation to COVID-19, the media reflect an uneven territorial and thematic distribution.

2. The mass media has become the means through which certain interest groups transmit values, giving a voice to some and rendering others invisible.

3. A discourse is given that reflects the interests and ideas of the establishment, focusing on the reactivation or regrowth of the tourism activity.

This article seeks to fill a gap in the knowledge as it provides a socio-territorial perspective of the key topics of tourism communication in the Spanish mass media, taking the pandemic as a turning point.

This introduction is followed by a bibliographic review with regard to two aspects: the role that tourism has had in the media and the diversity of the responses of the tourism activity in the different territories in Spain. Next, the sources used and the methodology employed for their exploitation are described, as are the main results. Finally, the discussion and conclusions obtained from this exploratory study are presented.

2. Literature review

The study of the mass media is a popular line of academic research in the social sciences, but in an unequal way, being principally addressed in political science and sociology (Jaung & Carrasco, Citation2022; McCombs & Shaw, Citation1972; Velasco González & Ruano, Citation2021). In 2004, the WTO considered the mass media “as that which covers all the activities and processes to bring buyers and sellers together. Mass media is the mode of communication which provides information about products, services and places; people move to different destinations for the purpose of leisure, rest, sightseeing and recreation” (as cited in Enemuo & Amaechi, Citation2015, p. 44). This definition is consistent with the volume of studies addressing television, radio, newspapers, journals, the internet, etc. as fundamental elements for the promotion and creation of the image of destinations (Cristea et al., Citation2015; Yazdani et al., Citation2018). There are many studies on tourism induced directly by the advertising of destinations or through other high impact media, such as the cinema (Enemuo & Amaechi, Citation2015; Beeton, Citation2006).

From a political economy point of view, mass media contribute to creating a common sense of cultural consent that serves the interests of the ruling class without coercion, where “capitalist classes control disproportionately -albeit incompletely- the media” and where “the demand for growth is wide-spread in a society whose stability depends on growth, and where survival and prestige are tied to money income” (Kallis, Citation2018, p. 141).

Since the very first pleasure trips and leisure tourism came into being, the media has influenced the decision of tourists, who associate certain trips with quality experiences (Beeton et al., Citation2006). They choose the destination depending on the information they receive from the mass media, selecting a place based on what they have heard, read or seen. The media aimed at the general public influence it by assigning certain meanings to the destinations. During the twentieth century, the newspapers and radio constituted the principal source of information, they were the most immediate and sometimes authorised (Nielsen, Citation2001; Santos, Citation2004), as opposed to the role acquired by the social networks in the twenty-first century.

The mass media has become consolidated as a basic tool in the construction of meanings among readers, as the news that it provides to the public is always related to the ideology and interests of the media (Sulistyorini et al., Citation2017). Through a specific narrative and genealogies, a discourse has been constructed in favour of certain interests, showing the priorities and concerns of the agents involved (Schmidt et al., Citation2013) in order to generate trust and security (Oliveira & Huertas, Citation2019) and reinforce their image and reputation (Xifra, Citation2020). Sometimes, the analysis of news articles can reveal future trends and research directions that will further our understanding of the tourism phenomenon (Cheng, Citation2016b). This reaffirms the relevance of including the Narrative Policy Framework for analysing sustainable tourism policies or for studying overtourism in different countries from a comparative perspective (Velasco González & Carrillo Barroso, Citation2021).

These dynamics are reinforced at certain times, such as the recent COVID-19 crisis, when the traditional media recovered their leading role (Casero-Ripollés, Citation2020), constituting a mediator between tourism and society. The media (mass media and social networks) are fundamental in the management of uncertainty in any type of crisis (Chew et al., Citation2010; Veil et al., Citation2011), as we can observe in the analysis of phenomena of a topical nature, for example, climate change or tourismphobia.

With respect to the field of tourism and climate change there is a high level of coverage in quantitative terms but the importance given in the scientific field to the topic is marginal. Nevertheless, the media can influence public opinion and contribute to the necessary social mobilisation in the most vulnerable tourist destinations (Gómez-Martín et al., Citation2016; Ma & Kirilenko, Citation2020).

Over the last few years, some academic studies have emerged in Spain that analyse the journalistic treatment of overtourism, and more specifically its association with tourismphobia (Egio Rubio & Fernández Toledo, Citation2020; Fuster Márquez & Gregori Signes, Citation2019; Pérez-García & García-Abad, Citation2018; Vázquez & De la Cruz Davila, Citation2020; Velasco González & Carrillo Barroso, Citation2021; Velasco González & Ruano, Citation2021). These studies examine the concept of tourismphobia related to urban areas and its evolution, based on a critical discourse analysis (Van Dijk, Citation2016) approach incorporating the news in its social context and conducting a discourse analysis (Bhatia, Citation2004, Citation2015) of visibility and impact values. Media gives more attention to problems derived from tourism that appear after active protest actions, and which are related to certain figures and political responses (Velasco González & Ruano, Citation2021).

This analysis is fundamental, as the social and political issues are constructed and reflected in and through the discourse (Pérez-García & García-Abad, Citation2018). This helps to determine a series of parameters to identify the treatment by the press of related concepts, such as touristification (Egio Rubio & Fernández Toledo, Citation2020). From a territorial perspective, these parameters facilitate the contextualisation of the incidence of the tourism industry on a consolidated destination, such as Spain, which is presented below.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Spain, a state dependent on tourism

In recent years, studies on the consequences of the crisis in tourism have proliferated, focusing on financial, health or geopolitical aspects (Hall, Citation2010; Murray & Cañada, Citation2021; Murray et al., Citation2017) and their repercussions on the highly specialised and dependent tourism and property model such as that of Spain (Blázquez et al., Citation2015; Fernández-Tabales & Cruz, Citation2013). Spain’s attractiveness as a tourist destination has given rise to historical affluence figures, which have given cause for reflection, complaint and action among the social agents. However, at the same time there are territories that do not receive tourist flows. This shows an unbalanced, polarised model which is increasingly dependent upon the sector in certain areas, such as the Balearic Islands, where, in 2019, it represented 44.8% of GDP and 32% of employment; the Canary Islands, where it accounted for 35% of GDP and 40.4% of employment; or Cantabria, where the tourism industry made up 12% of GDP and 14% of employment (Exceltur, Citation2018; Generalitat de Catalunya, Citation2020).

This context includes a wide range of realities ranging from consolidated and saturated territories, with agents calling for de-growth as a future strategy (Fletcher et al., Citation2019), to interior destinations, where tourism is seen as a possible opportunity for development (Blanco-Romero & Blázquez-Salom, Citation2021).

Despite the differences, the strategies adopted by each of the territories have incorporated the concept of resilience, due to the need to understand the capacity to respond to the crises, alterations and changes (Biggs et al., Citation2012). This socio-ecological perspective of territorial resilience, addressed by different authors for many years (Cork, Citation2009; Hopkins, Citation2010; Hudson, Citation2010; Wilding, Citation2011), is being reinvented and updated, giving rise to new scenarios of social, economic and environmental stability (Walker et al., Citation2004). Thus, socio-territorial resilience has become a specific response with two possible forms: The first as a reaction to overtourism, with a call for de-growth in saturated destinations; and the second consists of stimulating the tourism activity in emerging spaces that see tourism as an opportunity.

Despite the importance and interest of both territorial realities, the media have focused mainly on the debate generated by overtourism and degrowth proposals in urban destinations, often due to their sensationalist appeal. These proposals, which were initially defended by the affected social movements, explicitly addressed the idea of tourism de-growth, connecting it with the global discussion on de-growth (Kallis, Citation2011; Kallis & March, Citation2015; Kallis et al., Citation2020) and have been accepted and regulated by the public administrations of certain destinations, on the whole urban (Blázquez-Salom et al., Citation2019; Fletcher et al., Citation2021).

The reality has shown that these saturated tourist destination, as complex systems (Heidsieck & Pelletret, Citation2012), can be enormously affected by different types of crises (health, economic, geopolitical, etc.) to which they will respond in accordance with their level of resilience (Amat, Citation2013). An example is the economic collapse caused in Spain by the COVID-19 pandemic, whose share of GDP is estimated to have fallen from 12.4% in 2019 to 4.3% in 2020 (European Commission, Citation2020; INE, Citation2021). The recession produced in dependent destinations such as Spain, was not desired, but imposed and unplanned (Hickel, Citation2021). Therefore, it cannot be regarded as a social theory and social movement of resilience. Fair de-growth proposes “contraction and convergence, that is, economic de-growth in societies that experience an excessive use of resources and a (limited) growth on others” (Fletcher et al., Citation2019, p. 1.752). From this point of view, de-growth is related to the notion of “right sizing” (Hall, Citation2009) and from this perspective, interest groups participating in an economy with a strong tourism industry such as Spain, would see an opportunity in this crisis to restructure the tourism model, primarily by addressing labour conditions, the well-being of residents and ecological resilience (Blázquez-Salom et al., Citation2021).

3.2. Data analysis

According to the General Media Study (EGM), approximately 18.5% of the Spanish population read daily newspapers during 2020. This represented a reduction with respect to the previous year, confirming the decreasing trend initiated in 2009. However, the written media continue to have significant penetrating power (between 1.1% and 2.3% in national media and more than 0.3% in the majority of regional publications). Furthermore, their headlines are referred to on the radio and social networks, reinforcing their influence.

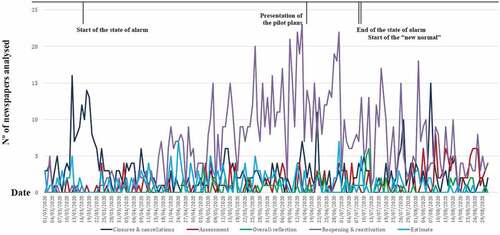

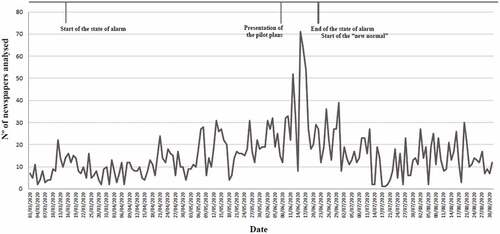

Given that the media have a direct effect on society and the determination of topics in the public agenda (Wolf, Citation1994), they are considered to constitute a good unit of analysis for this study. With this objective, we have conducted a systematic analysis of the newspaper coverage of COVID-19 and its impact on tourism. The study was carried out by using the online archives of the Spanish national, regional and local newspapers, with a total of more than 100 different publications (digital and print). The consultation was made through the digital newspaper archives MyNews, a company specialised in media monitoring, knowledge management and data analysis. A total of 2,440 pieces of written news were traced that included the words “tourism”, “tourist” and “COVID” in the title during the period of half a year, between 1st March and 31 August 2020, with an uneven daily frequency (Figure ).

Figure 1. The frequency of Spanish newspaper articles on COVID-19 and tourism.Source: Own elaboration.

In order to explore the principal topics and approaches taken by the Spanish written press, a double analysis has been conducted: 1) a quantitative analysis, which enables a general knowledge to be obtained and 2) a qualitative analysis, more specifically on the topics and dynamics of interest.

First, Atlas.ti 9.0 was used to identify the key conceptual structure and the relationships between the concepts of tourism communication (Cheng, Citation2016a). This tool enables us to make a preliminary analysis of the text based on word frequency statistics, facilitating the identification of the key concepts, their combinations and enables codification (Friese, Citation2021).

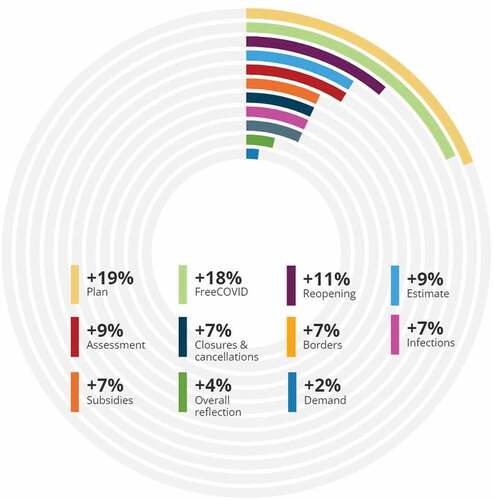

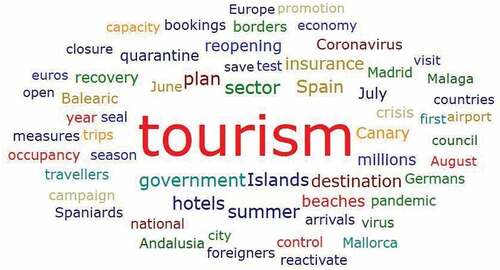

The analysis carried out focuses on territorial aspects relating to the tourism activity as a spatial rather than economic phenomenon. Based on the headlines, a word cloud was generated, only considering those words that are repeated at least 24 times, that is, 1% of the news. These words allow us to identify the main underlying ideas and establish a useful categorisation in the classification of the news (Figure ) as presented in the results section.

Figure 2. Word cloud by frequency in headlines. Source: Own elaboration.Note: The word tourism includes two related terms touristic and tourist.

The taxonomy shown in Table is quantitatively established to summarise the results of the previous quantitative analysis and interpret the phenomena that they evoke (Table ).

Table 1. Thematic content of the labels

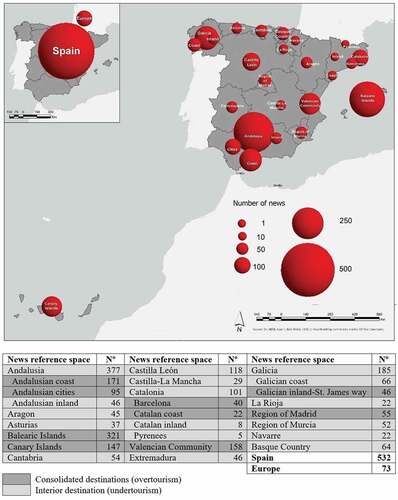

For the territorial analysis, we have taken the autonomous regions as a reference. We have considered independently by type of destination those that have a greater diversification, such as Galicia, Catalonia and Andalusia, in which we have distinguished between the news that affects the whole autonomous region, the cities, the coast and the interior areas. Furthermore, due to the volume of news (21.85%), all those items that refer to Spain or several regions together have been contemplated independently.

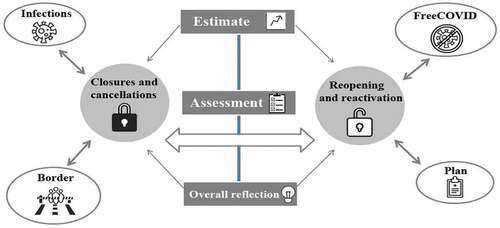

An analysis focused only on the high frequency words in an isolated way does not provide a clear image of the discourses. Alternatively, a conceptual map has been constructed reflecting the semantic network of the categories established to show the interrelations existing between all of the terms (Figure ). In this map, the size of the elements is proportional to the number of news pieces on this topic and the shape and colours indicate whether general aspects (estimate, assessment and reflection) or those associated to them are addressed. In this way, we can observe how the majority of the news items can be classified with several labels due to the relationship existing between the topics addressed.

4. Results

4.1. Content analysis of headlines

Analysing the news items enables us to corroborate that during the period studied news on the pandemic and tourism was published every day, even during the first two weeks of March, before the “state of alert” (start of lockdown) was declared by the Spanish government. The news items were not distributed homogeneously in terms of time or space, or with respect to the topics addressed. Similarly, we can identify a double trend (Figure ). On the one hand, there was a retrospective stance, assessing the problem and on the other hand, a prospective outlook focused on estimates and prospects for recovery.

In terms of time, we can observe an increase in frequency during the month of June, prior to the beginning of the summer holiday campaign—key to a seasonal destination of sun and sea—and marked by the development of initiatives such as the Pilot Plans and the guarantee of safety measures. Moreover, in this period, the situation returned to what was dubbed as the “new normal” after the first “state of alert” (15th March—21st June; Figures ). During the summer months, we can observe a highly uneven frequency of the news in the written press and an increase in the news on the radio and television, the discourses of which are not the object of this study. During this time, the most frequent topics were FreeCOVID and plans. The analysis of the contents of news headlines reveals several aspects or features of reopening, assessments (retrospective) and promotion, with different frequencies depending on the territories and agents.

4.2. Consolidated vs. emerging destinations

From a spatial point of view, we can highlight the significant volume of news items referring to a state level of analysis, which reflects the high level of interest in the sector in Spain and how it is addressed as a national issue, both in the general press and in the specialised economic publications (Expansión and Cinco Días daily newspapers). Even in the local media there was a remarkable number of news pieces referring to the national level. On the other hand, we can observe a disparity between the consolidated tourist destinations (archipelagos, Mediterranean coast and large cities) and the destinations in the interior (Figure ).

Figure 6. Map of the spatial distribution of the number of news items published in the period analysed.Source: Own elaboration.

The number of news pieces is greater in the areas characterised by their tourism specialisation. However, in the case of the cities of Barcelona and Madrid, despite the fact that the complete standstill of the activity altered the economic model of the cities, few news items or reflections can be found on what happened in these territories. In the case of Barcelona (40 news items), the discourse centred mainly on the reopening of its tourism resources and businesses. In Madrid (54 news items), the majority refer to the autonomous region and are related to Barajas airport as a source of the entry of new infections and the need to reinforce controls, the presence of medicalised hotels, the estimate and assessment of the losses and, from May 2020, the need for a reactivation plan.

With respect to the differentiation between the consolidated (urban and sun and beach) and emerging (interior) tourist destinations, we can observe considerable difference regards the volume of news items and the topics addressed. In both cases, there are many pieces contemplating the measures to follow to obtain the FreeCOVID stamp, the reopening and it’s planning (Table ). As for the consolidated destinations, there are many news items that address the concern and measures to apply to prevent infection, the effects derived from the closures in March-April and the cancellations in June-July. On the other hand, with regards the interior destinations, particularly in Extremadura, Castilla-León and the Basque Country, we can find many promotional campaigns (included in the “plans” category; Table ), and news related to the demand, calculations of the estimates and planning. The desire of these destinations to promote themselves is related to the opportunity offered by the restrictions to mobility and the increase in domestic and proximity tourism.

Table 2. Comparison between the amount of news about overtourism areas (consolidated coastal and urban destinations) and undertourism areas (interior)

4.3. The actors and their discourses

In addition to the principal elements of the discourses, it is important to understand the map of actors involved in the process. The actors involved are many and highly diverse, as both public and private agents intervene on a national and international level, reflecting the situation that was experienced and how the institutions have influenced tourism in their public agenda.

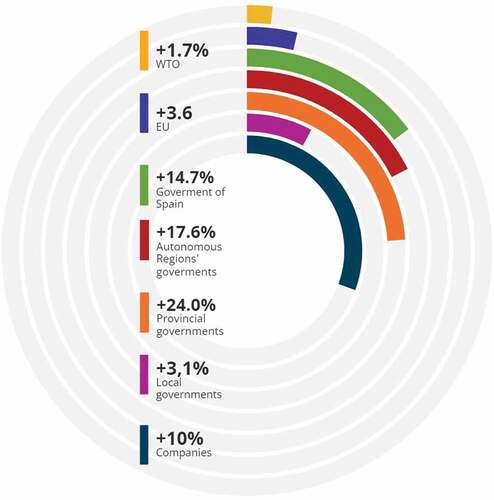

The international institutions (WTO) (60 news items) address the analysis of the situation and matters related to tourism as a reinvigorating element of the economy that requires reactivation through programmes and the European Union (129 news items) focuses on the organisation between European countries. In this respect, we should highlight the directive by which the EU countries had to permit common actions and measures for the transit of passengers (borders and air corridor) and controlling their health (Figure ).

On a national level, in the media we can identify the presence of four actors corresponding to the executive branches of all levels of government: The Government of Spain (525); the regional governments, which are responsible for tourism affairs (629); and the provincial (859) and local governments (281; Figure ). This shows the intergovernmental nature of the phenomenon. It also demonstrates the public interest related to decision-making, at a time marked by constraints and insecurity, within a general discourse of precaution, in which health criteria take precedence over economic ones.

During the whole period analysed, the focus of many of the news items was the Government of Spain. This allows a longitudinal analysis to be conducted beginning with the closure of borders and repatriations, the standstill of activities, the subsidies, the reopening of borders and the reactivation. The majority of the items reveal that the Government of Spain was the interlocutor between the rest of the international and national actors and responsible for the dialogue among them. Most of all, they show that the central government was the guarantor of the safe development of the tourism activity, as the other administrations and entrepreneurs looked to it for actions and planning strategies. The volume of news items shows that tourism is understood as a fundamental activity on a national level (Alvarez-Diaz et al., Citation2020), on which there is a strong dependence, which is why it is addressed as a state issue.

On the other hand, the regional governments sought authorisation, guidelines and economic subsidies from the Government of Spain in order to design and execute promotional programmes and specific plans, such as the pilot plan developed by the regional government of the Balearic Islands. And often they offered hard opposition to the decision of the central government. The news items reflect that the regional governments were responsible for ensuring the safety of tourists and residents through specific actions such as the closure of public spaces, health controls, and the establishment of limitations to capacities or isolation in medicalised accommodation. Furthermore, it is the administration that is responsible for granting the FreeCOVID stamps.

Not all of the regional governments have had the same presence in the media. We can observe that those occupying the most headlines were: The regional governments of Andalusia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, Galicia and the Basque Country. The first four are responsible for some of the most important tourist destinations on an international level, particularly sun and beach destinations.

On an intermediate level are the provincial governments, which, like the other administrations, undertake assessments and estimations. Specifically, their work focuses on promotion-related tasks (tourism campaigns and the design of apps) and the training of the agents. The news items related to the provincial governments refer to provinces associated with interior tourism, with the majority being represented.

Local governments had an unequal, although stable territorial presence in the media throughout the period analysed. The municipalities occupying the highest number of headlines are located on the coast and have a tourism tradition, such as Roquetas de Mar, Torreblanca, Ferrol or Santander, among many others. Their councillors designed safety protocols, established restriction measures, closed establishments and services, certified safe territories, controlled capacities (particularly beaches, sometimes with technology such as drones, sensors or mobile apps), and even limited the arrival of tourists and second-home owners. The local governments were also responsible for promotional campaigns, as in the case of Seville or Mérida, and for developing activities and designing recovery plans.The analysis of the contents of the news items confirms that the regional and local governments have constituted “executing arms”.

The presence of private agents in the media was greater (1,095 news items) and constant throughout the whole period. This enables us to carry out a longitudinal analysis. During this time, news pieces were published indicating the economic losses and the fear of having to close before the end of the year 2020, followed by news related to the application to the administration for economic subsidies and the granting of the FreeCOVID stamp. Finally, news items appeared related to the reactivation and the initiatives that have been developed, such as the formation of business groups, the implementation of tourist vouchers, promotional tasks and the work undertaken by technological companies.

However, we can observe that there are certain interest groups without a voice in the media, as there were no headlines that include references to platforms, neighbourhood groups or social movements. The discourse of these groups is focused on a criticism of the existing type of tourism and the possibility of using the pandemic as an opportunity to change the model. This discourse has a very marginal presence in the written press.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The results corroborate the importance of the media for supporting the tourism industry because of its economic importance. This is not exclusive to Spain, although it is particularly relevant in this country as it is highly dependent on the sector in socio-economic terms (Chen et al., Citation2020; Fuster Márquez & Gregori Signes, Citation2019).

Thus, media with opposing political stances share the argument that tourism is a source of employment and economic development. This breaks the trend that began before the pandemic, in which some media criticised tourism and its effects as a consequence of overtourism. There has been a shift away from the discourse that had been dominant until then and recovered in 2020, faithful to the interests led by businessmen in the sector (Velasco González & Carrillo Barroso, Citation2021). In addition, the companies, especially those engaged in accommodation and transportation, have a very prominent and constant presence throughout this time. They generate an image not only of employers but also of responsible companies with the capacity to collaborate with one another and with the administration to develop common strategies to ensure safety, even helping society with medicalised hotels (Chen et al., Citation2020).

The situation of these tourism scenarios and alternatives in contrasting territories is reflected in the media, also in a highly diverse way, which reveals the unequal geographical development and the conditions of overtourism or undertourism of each of them. This uneven development within a booming sector such as tourism has also given rise to diverse reactions on a social and institutional level, principally to tourist saturation, far removed from the promotion and development strategies of the possible emerging destinations.

In relation to COVID-19, the media reflect an uneven territorial and thematic distribution, focused mainly on mature tourist spaces. Aspects such as the frequency of news items on reopening, assessments (retrospective) and promotion, principally in the territories of undertourism clearly differ from those of overtourism, focused on the need for plans.

Interior destinations have shown their interest in developing promotional strategies and using the opportunity to attract proximity tourists. Nevertheless, the success experienced, with the absence of planning, has revealed the danger of temporary saturation and the lack of a consolidated management model to ensure the survival of these territories (Medina-Chavarría et al., Citation2022). In order to ensure an opportunity of territorial resilience, it would be necessary to involve the existing economic, cultural and social actors in the process (Chien-yu & Chin-cheng, Citation2016), and the development of other corporate strategies unrelated to COVID. These should take advantage of the recognition received by certain places from domestic travellers, the change of model towards proximity, the strong technification of tourists and the digitization of services (understood as an opportunity) and the increase in economic subsidies to favour the creation of future products (Chen et al., Citation2020). These opportunities can be generalised to other similar territories, regardless of the country in which they are located.

The territorial disparity is also visible within the consolidated spaces, which have not received the same treatment in the media. Barcelona and Madrid, two of the principal tourist destinations in the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, have received little attention in the press. However, the Balearic and Canary Islands and certain coastal areas, such as the Costa del Sol or the Region of Valencia have received a high level of interest. As well as clearly being spaces of overtourism, they all have an economic and social dependence on tourism. Therefore, the discourse prevailing in these places is related to the COVID FREE concept and, ultimately, to the generation of security, something basic in the reduction of uncertainty and, ultimately, for the recovery of activity (Uzuner & Ghosh, Citation2020; Neuburger & Egger, Citation2021).

According to the study of news cycle in the summer of 2020, it is possible to measure the reactions of the agents involved in the face of a novel phenomenon. It was found that the dominant discourse was one that promoted reopening (WTO and private agents), the establishment of safe corridors (EU), the adoption of health guarantees (FreeCOVID) and the promotion of the destination (regional public administrations). This discourse has also prevailed in many other countries, where the lack of consensus and international commitment to tourism and the lack of a reflection in the model, advocating for reactivation pro-re-growth, developing local initiatives whose path is shown to be short-sighted, prevent the sector and society from preparing for future crises (Gössling et al., Citation2020; Hale et al., Citation2020; Kreiner & Ram, Citation2020).

The economic discourse that favoured reactivation or “re-growth” was dominant in every region. In this sense, the alternative proposals to use the opportunity that the crisis offered in order to change the model were marginalised (Blázquez-Salom et al., Citation2021). These proposals were made by social movements through other media such as social networks or the minority press which transmitted discourses favouring de-growth, in contrast to the printed press which are more traditional and yielding to the hegemonic actors.

It is evident that the media play a key role in forming a state of opinion in circumstances of crisis and uncertainty (Chew et al., Citation2010; Veil et al., Citation2011). The analysis of the discourses reflected in the news items forms the basis for the construction of social and political relations. Power relations are negotiated and are put into practice through discourse, through which ideologies are constructed and these relations are reinforced (Van Dijk, Citation2016). The abundance of news and its contents regarding the COVID-19 pandemic show the formation of dominant discourses that favor the promotion of tourism activity. The hegemonic and economicist approach already existing in the treatment of topics such as the denunciation of touristification (Murray & Cañada, Citation2021), tourismphobia (Pérez-García & García-Abad, Citation2018; Velasco González & Ruano, Citation2021) or climate emergency (Boykoff & Boykoff, Citation2007; Gómez-Martín et al., Citation2016) is maintained.

In conclusion, studying the news items in the written press has enabled us first, to identify territorial differences arising from the spatial disparity of tourism development. Second, to highlight the social hegemony of a consolidated and widespread opinion that reflects and legitimises the discourses favouring strategies of economic reactivation and regrowth, as opposed to the proposals to change to models favouring tourism de-growth. And third, to show that the use of the media shapes a state of opinion that reproduces social relations marked by the power of the business sector.

This study enriches the current research on the epidemic-induced tourism crisis and opens up new research opportunities. On the one hand, allowing the possibility to analyse the media reaction to the different stages of COVID, and on the other, to explore the effectiveness of crisis response strategies and the marketing of post-crisis tourism products. Finally, it should be noted that future lines of research should incorporate the analysis of the political debate in other communication channels, such as the minority print media or social networks, and their contribution to the creation of an antagonistic social discourse.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carmen Mínguez

Carmen Mínguez is an Associate Professor in Geography at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Her research examines the relationships and the interdependencies between tourism and historic cities, specifically focusing on how to improve cultural heritage and functionally revitalize historic centers and monumental areas of cities. She is a member of the “Tourism, heritage and development” research group.

Asunción Blanco-Romero

Asunción Blanco-Romero is a Tenured Professor of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain). She is a member of the TUDISTAR research group (Tourism and socio-territorial dynamics) in which she has participated in several research projects. Her research interests include resilience tourism and local development, globalization and sustainability degrowth strategies, territorial planning, geographic and gender issues in cooperative development.

Macià Blázquez-Salom

Macià Blázquez-Salom is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of the Balearic Islands. His research interests include tourism, sustainability, development, spatial planning and nature conservation. He has been a visiting scholar in several European, American and Asian universities.

References

- Alvarez-Diaz, M., D’Hombres, B., Ghisetti, C., & Pontarollo, N. (2020). Analysing domestic tourism flows at the provincial level in Spain by using spatial gravity models. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 403–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2344

- Amat, X. (2013), La resiliencia del territorio alicantino. PhD. University of Alicante.

- Beeton, S. (2006). Understanding film-induced tourism. Tourism Analysis, 11(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354206778689808

- Beeton, S., Bowen, H. E., & Santos, C. A. (2006). State of knowledge: Mass media and its relationship to perceptions of quality. In G. Jennings & N. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality tourism experiences (pp. 43–55). Routledge.

- Bhatia, V. J. K. (2004). Worlds of written discourse. A genre-based view. Continuum.

- Bhatia, V. J. K. (2015). Critical genre analysis. Theoretical preliminaries. Hermes – Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 54(54), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v27i54.22944

- Biggs, D., Hall, C. M., & Stoeckl, N. (2012). The resilience of formal and informal tourism enterprises to disasters: Reef tourism in Phuket, Thailand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(5), 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.630080

- Blanco-Romero, A., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (2021). Inland territorial and tourism resilience in a polarized world. In C. Bevilacqua, F. Calabrò, & L. Della Spina (Eds.), New metropolitan perspectives. NMP 2020. Smart innovation, systems and technologies (Vol. 178, pp. 1886–1896). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48279-4_178.

- Blázquez, M., Artigues, A. A., & Yrigoy, I. (2015). Crisis y planificación territorial turística neoliberal en las Islas Baleares. Investigaciones Turísticas, 9, 24–49. https://doi.org/10.14198/INTURI2015.9.02s

- Blázquez-Salom, M., Blanco-Romero, A., Vera-Rebollo, F., & Ivars-Baidal, J. (2019). Territorial tourism planning in Spain: From boosterism to tourism degrowth? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1764–1785. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1675073

- Blázquez-Salom, M., Cladera, M., & Sard, M. (2021). Identifying the sustainability indicators of overtourism and undertourism in Majorca. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(5), 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.630080

- Boykoff, M. T., & Boykoff, J. M. (2007). Climate change and journalistic norms: A case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum, 38(6), 1190–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008

- Cañada, E., & Izcaga, C. (2021). Turismos de proximidad. Un plural en disputa. Icaria.

- Cañada, E., & Murray, I. (2021). #tourismpostcovid19. Turistificación confinada. Barcelona: Alba Sud Editorial. Colección Turismos, 7. https://www.albasud.org/publicacion/es/103/tourismpostcovid19-turistificacion-confinada

- Casero-Ripollés, A. (2020). Impacto del Covid-19 en el sistema de medios. Consecuencias comunicativas y democráticas del consumo de noticias durante el brote. Profesional de la Información, 29(2), 1–12. https://revista.profesionaldelainformacion.com/index.php/EPI/article/view/79790

- Cheng, M. (2016a). Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003

- Cheng, M. (2016b). Current sharing economy media discourse in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 111–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.07.001

- Chen, H., Huang, X., & Li, Z. (2020). A content analysis of Chinese news coverage on COVID-19 and tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1763269

- Chew, C., Eysenbach, G., & Sampson, M. (2010). Pandemics in the age of Twitter: Content analysis of Tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PloS one, 5(11), e14118. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014118

- Chien-yu, T., & Chin-cheng, N. (2016). Vulnerability, resilience, and the adaptive cycle in a crisis-prone tourism community. Tourism Geographies, 18(1), 80–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2015.1116600

- Cork, S. (2009). Brighter prospects: Enhancing the resilience of Australia.

- Cristea, A. A., Apostol, M. S., & Dosescu, T. (2015). The role of media in promoting religious tourism in Romania. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.398

- Egio Rubio, C. J., & Fernández Toledo, P. (2020). Tratamiento en la prensa digital de un fenómeno geográfico: La turistificación. Cuadernos de Turismo, 46(46), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.6018/turismo.451831

- Enemuo, O. B., & Amaechi, B. (2015). The role of mass media in tourism development in Abia State. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Sports, 11, 44–50. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234696817.pdf

- European Commission. (2020), European economic forecast, Autumn 2020.

- Exceltur. (2018), PIB y empleo turístico por CCAA. Avaible: http://www.exceltur.org/pib-y-empleo-turistico-por-c-c-a-a/

- Fernández-Tabales, A., & Cruz, E. (2013). Análisis territorial del crecimiento y la crisis del sector de la construcción en España y la Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía. EURE (Santiago), 39(116), 5–37. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612013000100001

- Fletcher, R., Blanco-Romero, A., Blázquez-Salom, M., Cañada, E., Murray, I., & Sekulova, F. (2021). Pathways to post-capitalist. Tourism Geographies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1965202

- Fletcher, R., Murray, I., Blanco-Romero, A., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (2019). Tourism and degrowth: An emerging agenda for research and praxis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1745–1763. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1679822

- Friese, S. (2021). Atlas-ti user manual. By ATLAS.ti scientific software development GmbH. Document version: 1.0.0.208 (23.07.2021 17:55:52) https://doc.atlasti.com/ManualWin.v9/ATLAS.ti_ManualWin.v9.pdf

- Fuster Márquez, M., & Gregori Signes, C. (2019). La construcción discursiva del turismo en la prensa española (verano de 2017. Discurso y sociedad, 13(2), 195–224. http://www.dissoc.org/ediciones/v13n02/D&S13(2)Fuster&Gregori.html

- Generalitat de Catalunya. (2020), Turisme. Departament d’Economia i Empresa. Web: http://economia.gencat.cat/ca/ambits-actuacio/economia-catalana/trets/estructura-productiva/turisme/

- Gómez-Martín, M. B., Armesto-López, X., & Amelung, B. (2016). Tourism, climate change and the mass media: the representation of the Issue in Spain. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(2), 174–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1048196

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism, and global change: A rapid assessment of Covid-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Hale, T., Webster, S., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., & Kira, B. Blavatnik School of Government; 2020. Oxford covid-19 government response tracker. University of Oxford. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/BSG-WP-2020-032-v6.0.pdf

- Hall, C. M. (2009). Degrowing tourism: Décroissance, sustainable consumption and steady-state tourism. Anatolia: and International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 20(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2009.10518894

- Hall, C. M. (2010). Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.491900

- Heidsieck, C. B., & Pelletret, C. (2012). Répondre aux défis des territoires par l’union des associations et des entreprises. Cahier Espaces, 113, 129–137.

- Hickel, J. (2021). What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations, 18(7), 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1812222

- Hopkins, R. (2010), Localisation and resilience at the local level. The case of Transition Town Totnes (Devon, UK). PhD. University of Plymouth.

- Hudson, R. (2010). Resilient regions in an uncertain world: Wishful thinking or a practical reality? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp026

- Huertas, A., Oliveira, A., & Girotto, M. (2020). Gestión comunicativa de crisis de las oficinas nacionales de turismo de España e Italia ante la Covid-19. Profesional de la información, 29(4). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.jul.10

- INE. (2021), Aportación del turismo al PIB de la economía española por valor absoluto/porcentaje/índice, tipo de indicador y periodo. Avaible in: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t35/p011/rev19/serie/l0/&file=03001.px#!tabs-tabla ( 5 de marzo de 2021)

- Jaung, W., & Carrasco, L. R. (2022). A big-data analysis of human-nature relations in newspaper coverage. Geoforum, 128, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.11.017

- Kallis, G. (2011). In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics, 70(5), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.12.007

- Kallis, G. (2018). Degrowth, agenda publishing limited, newcastle upon tyne.

- Kallis, G., & March, H. (2015). Imaginaries of hope: The utopianism of degrowth. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(2), 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.973803

- Kallis, G., Paulson, S., D’Alisa, G., & Demaria, F. (2020). The case for degrowth (pp. 151). Polity Press Cambridge.

- Kreiner, N. C., & Ram, Y. (2020). National tourism strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic, Annals of tourism research.

- Ma, S., & Kirilenko, A. P. (2020). Climate change and tourism in English-language newspaper publications. Journal of Travel Research, 59(2), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519839157

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1086/267990

- Medina-Chavarría, M. E., Gutiérrez, A., & Saladié, Ò. (2022). Respuesta al aumento de visitantes en los Espacios Naturales Protegidos de Cataluña en tiempos de COVID-19: Una revisión a partir de publicaciones en medios de comunicación digitales. Boletín De La Asociación De Geógrafos Españoles, 93. https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.3183

- Murray, I., Yrigoy, I., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (2017). The role of crises in the production, destruction and restructuring of tourist spaces. The case of the Balearic Islands. Investigaciones Turísticas, 13, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.14198/INTURI2017.13.01

- Neuburger, L., & Egger, R. (2021). Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1003–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1803807

- Nielsen, C. (2001). Tourism and the media: Tourist decision-making, information and communication. Hospitality Press.

- Oliveira, A., & Huertas, A. (2019). How do destinations use twitter to recover their images after a terrorist attack? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 12, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.03.002

- Pérez-García, A., & García-Abad, L. (2018). Turismofobia: Presencia, impacto y percepción del concepto a través de los medios de comunicación impresos. adComunica, 16(16), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2018.16.11

- Pons, G. X., Blanco-Romero, A., Navalón-García, R., Troitiño-Torralba, L., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (2020). Sostenibilidad Turística: Overtourism vs undertourism. Mon. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears, 31, 610. https://www.age-geografia-turismo.com/app/download/7752826511/Sostenibilidad+Tur%C3%ADstica%2C+Mon.+Soc.+Hist.+Nat+Balears%2C+31.pdf?t=1603352996clippedurlhttps://acortar.link/KCWnr2

- Santos, C. A. (2004). Perception and interpretation of leisure travel articles. Leisure Sciences, 26(4), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400490502462

- Schmidt, A., Ivanova, A., & Schäfer, M. S. (2013). Media attention for climate change around the world: A comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1233–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.020

- Sulistyorini, D., Sudardi, B., Warto, W., & Wijaya, M. (2017). Cultural commodification: Representation of pesarean1 of mount Kawi as cultural tourism in Indonesian mass media. ISLLAC: Journal of Intensive Studies on Language, Literature, Art and Culture, 1(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.17977/um006v1i12017p019

- Torres, R., & Fernández, M. J. (2020). La economía española en 2019 y previsiones para 2020-2022. Cuadernos de Información Económica, 274, enero/febrero. Avaible in https://www.funcas.es/publicaciones_new/Sumario.aspx?IdRef=3-06274

- Uzuner, G., & Ghosh, S. (2020). Do pandemics have an asymmetric effect on tourism in Italy? Quality & Quantity, 55(5), 1561–1579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01074-7

- Van Dijk, T. A. (1998). What is political discourse analysis. In J. Blommaer & C. Bulcaen (Eds.), Political linguistics (pp. 11–52). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Van Dijk, T. A. (2016). Estudios Críticos del Discurso: Un enfoque sociocognitivo. Discurso & Sociedad, 10(1), 137–162.

- Vázquez, E. R., & De la Cruz Davila, J. (2020). Turismofobia: Un análisis social desde los medios de comunicación. Boletín Científico INVESTIGIUM de la Escuela Superior de Tizayuca, 5(10), 33–37. https://doi.org/10.29057/est.v5i10.4985

- Veil, S. R., Buehner, T., & Palenchar, M. J. (2011). A work‐in‐process literature review: Incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 19(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2011.00639.x

- Velasco González, M., & Carrillo Barroso, E. (2021). La corta vida de un concepto: Turismofobia en los medios españoles. Narrativas, actores y agendas. Investigaciones Turísticas, 22(22), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.14198/INTURI2021.22.1

- Velasco González, M., & Ruano, J. M. (2021). The crossfire rhetoric. success in danger vs. unsustainable growth. analysis of tourism stakeholders’ narratives in the Spanish press (2008–2019. Sustainability, 13(16), 9127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169127

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., & Carpenter, S. R. (2004), Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-ecological Systems. Ecology and society, 9(2). www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5/ 04/08/2021

- Wilding, N. (2011). Exploring community resilience in times of rapid change.Carnegie. UK Trust.

- Wolf, M. (1994). Los efectos sociales de los media. Paidós.

- Xifra, J. (2020). Comunicación corporativa, relaciones públicas y gestión del riesgo reputacional en tiempos del Covid-19. El profesional de la información (EPI), 29(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.20

- Yazdani, M., Alipour, E., Dashti, A. H., & Arzhengi, B. (2018). Analysis and evaluation of the role of mass media on urban branding in tourism. Civil Engineering Journal, 4(5), 1087–1094. https://doi.org/10.28991/cej-0309158