Abstract

South Africa has been battling with getting land reform right since the advent of democratic rule in 1994 The need to expedite land reform in the country has given rise to a number of radical approaches, including the topic and controversial expropriation of land without compensation discourse. The simulation results presented in this paper provide nuanced policy options for land redistribution in South Africa in the face of the looming expropriation of land without compensation. The analysis in this paper is specific to agricultural land as opposed to land in general. We carried out scenario simulation through Computable General Equilibrium approach using the modified University of Pretoria General Equilibrium Model (UPGEM), which is solved using GEMPACK solution software. Our simulation revealed that there would be adjustment costs regardless of the option(s) chosen. The Inclusive Scenario came up as the most suitable policy option in terms of minimal adjustment costs and allowing the sector to continue to grow, albeit at a lower rate compared to the status quo. Given that agricultural land reform is imperative in South Africa, policy makers should opt for the policy option that is least disruptive to the economy while achieving the desired outcome of more equitable agricultural land ownership and broader participation in the agricultural sector by the majority in the country. Thus, the Inclusive Scenario was found to be the most suitable policy option for agriculture land reform in South Africa.

1. Introduction

There is no doubt that land reform is once again high on the development agenda. Post socialist countries in Asia and Europe have seen a substantive shift in control over land from state and collective units to smallholder (Sikor & Müller, Citation2009). Governments across Africa, Asia and Latin America recognize customary land rights by issuing formal titles to local people. Policy makers in parts of Latin America and Africa implement programmes that redistribute land from large landowners to landless people and tenants (farm dwellers). All the programmes have one commonality, which is, they seek to establish and/or enhance land rights of and access to land by disadvantaged groups by way of legal and administrative acts (Sikor & Müller, Citation2009). In this way, the programmes constitute land reforms, although their fundamental objectives and modalities vary greatly (El-Ghonemy, Citation2003; Lipton, Citation1993). The South African government is amongst those countries in Africa that are vigorously pursuing fundamental land reform (Davis et al., Citation2020; Wiig & Øien, Citation2013).

South Africa has a notorious history of alienating the majority of its people from access, use and ownership of land (Karaan & Vink, Citation2014; Lipton, Citation1977; Sihobo & Kirsten, Citation2021). Dispossession and forced removals of African people under colonialism and apartheid resulted in extreme land shortages and insecurity of tenure for much of the black population (Lahiff, Citation2001). Thus land reform is a development imperative in South Africa. The intended objective of land reform in South Africa can be summarised as bringing about fundamental transformation of property rights in order to (re)address the history of land dispossession and lay the foundations for the social and economic emancipation of the rural and urban poor. Thereby, the land reform process in South Africa has both social and economic underpinnings making it a complex and difficult endeavour. Furthermore, in the 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) the African National Congress (ANC), which is the ruling party, undertook to redistribute 30 percent of agriculture land within five years and to make land reform the nucleus of a programme of rural development (ANC, Citation1994:8). According to Ngam (Citation2021), the apartheid government allocated 80 percent of agricultural land to the white minority, accounting for only 10 percent of the South African population and leaving the 90 percent black population to live of the remaining 20 percent.

Land Reform in South Africa has been implemented through three government programmes, namely: restitution, redistribution and tenure reform. The plethora of literature that can be read for detailed discussions on the three approaches to land reform in South Africa are Lahiff (Citation2001), Cousins (Citation2000), and Department of Land Affairs (DLA; Citation1997), and Rugege (Citation2004) amongst others. Agriculture is a vital sector in African economies as an economic development catalyst. The agricultural sector in Africa has been receiving increased attention and scrutiny by policy makers and business because of its economic importance, especially in employment creation, poverty alleviation and empowerment of the masses and food security (Mkhabela, Citation2018).

The need to accelerate land redistribution and promote transformation in the sector cannot be overemphasized. However, the need to sustain a viable and affordable food system is equally important and this has been acknowledged by the ANC, which is the ruling party. Therefore, the key challenge is to find a balance between maintaining a viable agricultural economy and improving the pace on land reallocation and transformation in the sector to achieve the inclusivity of the previously disadvantaged individuals (PDIs). Ding (Citation2003) asserts that any evaluation or assessment of land reform policy should cover both the intended effects and the unintended consequences. While expropriation of land without compensation may appear to be a tailor-made solution the poor majority there are a number of possible unintended consequences that it could bring (Akinola et al., Citation2021; Zantsi et al., Citation2021), for example, food insecurity, job loss, communal conflicts and violence, and an economic meltdown (Matseke, Citation2021). In this paper, we create a database comprising two agricultural sectors, namely, commercial and emerging sub-sectors. We then apply a dynamic general equilibrium model to determine the new equilibrium with higher share of production by emerging farmers while retaining a prosperous agricultural sector and economy at large.

The overarching motivation of this study is to quantify the expected socio-economic impacts of fast-tracking the land redistribution programme in South Africa, either under the current or amendment legislation. There is a paucity of empirical evidence of the socio-economic impacts of fast-tracking the land reform programme in South Africa and we are not aware of any studies that have attempted to quantify the socio-economic impacts of radically accelerating the land reform process in South Africa. A number of studies to assess the socio-economic impacts of fast tracking land reform have been done in Zimbabwe. For example, Ngarava (Citation2020) assessed the impact of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) on agricultural production using the tobacco production sub-sector as a case study. It must be emphasized that our focus is limited to land redistribution pillar of the land reform that seeks to redistribute land for productive agricultural use. The renewed attention that the land reform process in South Africa is currently enjoying warrants a thorough analysis of the cost and benefits of various scenarios that could be pursued. Furthermore, it would be foolhardy for policy makers to implement radical land reform without the empirical evidence to support the option chosen.

2. Progress in structural changes in the agricultural sector

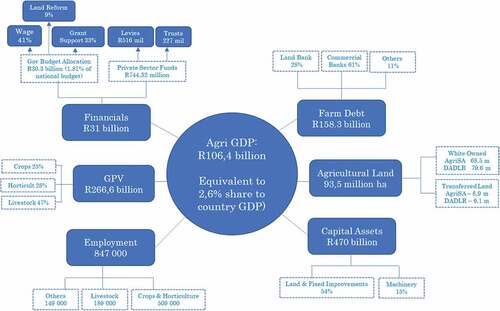

The South African agricultural sector remains relatively dualistic in structure encompassing just over 30 thousand large commercial farmers that produce nearly 95 percent of agricultural output and millions of small-scale farmers that are typically characterised by poor on-farm infrastructure and uncoordinated production systems (Bernstein, Citation2013; Greyling et al., Citation2015; Gwebu & Matthews, Citation2018; Kirsten, Citation2006; Sihobo & Kirsten, Citation2021). The overall agricultural sector plays an integral role in the South African economy contributing 2.6 percent to Gross Domestic Product (GDP); providing 847 thousand jobs, largely to low-skilled labour force, and generating over R146 billion from foreign markets (Stats, Citation2021; Van Zyl et al., Citation1988; see, Figure ). In terms of land in South Africa, 93.5 million is used for agriculture. Farm debt was approximately R158.3 billion, with agricultural capital assets at R470 billion in 2017 (Mthombeni, Bove & Thibane, 219; Conradie, Citation2019; Wegerif, Citation2022). Government allocated approximately R30.3 billion to agriculture, while the private sector funds allocated to agriculture were approximately R744 million (National Treasury, Citation2021). Despite this undisputable role in the economy, the country through the Nation Development Plan (NDP) committed to an inclusive economy, which benefits all its citizens. The importance of an inclusive economy gained momentum at the 54th conference of the ruling party in December 2017 where radical policy decisions were adopted to speed the inclusion of previously disadvantaged individuals (PDIs) in the formal economy. One of these decisions was the expropriation of land without compensation in order to accelerate land reform and participation of PDIs in the food system (Mubecua et al., Citation2020).

President Ramaphosa in his State of the Nation Address reaffirmed the need for inclusivity and fast-tracking land reform in February 2018 (SONA 2018). The land debate is sensitive and the lack of reliable and unbiased land ownership numbers adds to the distortion of the debate. The existing numbers by Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR), Citation2017, AgriSA (Citation2017), and Sihlobo and Kapuya (Citation2017), on agricultural land ownership and redistribution, are highly contested primarily because of methods used to collect the data. Despite the lack of consensus, the offer some good insight into the land redistribution patterns, which indicate that about 72 percent of agricultural land, is still owned by large commercial farmers (see, Figure ). This implies that 24 percent of previously white owned land has been redistributed taking into account both government and private land transactions.

Interestingly, the quantum of redistributed land has not been translated into production growth implying that other factors are required to unlock the meaningful participation of the PDIs in the formal food system. For example, statutory data from the National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC) show that on average 94 percent of agricultural output is produced by commercial farmers (NAMC, 2017) suggesting that emerging farmers have not gain any significant share in food value chains despite redistributed agricultural land. Scholars such as Kirsten et al. (Citation2016), Lyne (Citation2014), Dlamini et al. (Citation2013), and Kirsten et al. (Citation1996), have identified lack of post-settlement support; group characteristics and conflicts; and limited access to markets as chief factors causing limited success of PDIs. It is clear that there are sunk costs that government must incur in order to realise meaningful participation of PDIs in the food system. Such costs include investing in human capital; markets; rural infrastructure and on efficient and effective post settlement support mechanisms.

In 2009, the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR) did an evaluation of the implementation of land reform programmes since their inception. The evaluation identified that most projects were not successful and therefore in distress; there was a lack of adequate and proper post-settlement support; and some projects which were acquired through the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development programme (LRAD) were on the verge of being auctioned or had been sold due to collapse of the projects. Due to the above scenario, the Recapitalization and Development Programme (RADP) was introduced in 2010 in order to address the above challenges. The RADP targets projects that were acquired through restitution and redistribution programmes. The programme intends to provide black farmers with social and economic infrastructure and basic resources; combat poverty, unemployment and improve income; reduce current rural-urban migration; and complement agricultural programmes of the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) such as the Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme (CASP) (DRDLR, 2014).

While land redistribution is an important means of production, however, it is not sufficient. The lack of other essential supports to PDIs results in high level of food waste. For example, Oelofse and Nahman (Citation2013) found that 30 percent of South African food is wasted which is equivalent to about 9 million tonnes per annum. Approximately 26 percent of this total food wastage is at production level partly driven by high level of waste from emerging farmers. Hendrick (Citation2014) notes that the lack of food policy framework that tackles food waste and inadequate support to the sector is contributing to high poverty levels in South Africa. The country is food-insecure at household level with more than 13 million people living under poverty line.

According to Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR; Citation2017),93956125ha or 82% of the total114223273ha land is owned by private landowners. DRDLR also highlights that 89523044 ha or 95% of the land is owned by individuals (41%), companies (26%) and trusts (33%)—followed by CBOs at3549489ha or 4%, and co-landowners at883589ha or 1%. Furthermore, the report highlights that37078289ha farms and agricultural holdings are owned by individuals:26663144ha or 72% of which are Whites; followed by Coloured (mixed descent) at5371383ha or 15%; Indians at2031790ha or 5%; Africans at1314873ha or 4%. The report also highlights that co-owners own425537ha or 1%, while others own1271562ha or 3%. However, AgriSA in their land audit (AgriSA, Citation2017) highlighted that farmland has decreased from approximately 79.3% in 1994 to 76.3% in 2016. The report further highlighted that Previous Disadvantaged Individuals and Government ha have bought a total of 8.9 million at a total value of R90.3 billion. AgriSA further highlights that the 8.9 million ha equates to 12.9% of the total hectares that were traded, with the R90.3 billion equating to 22.5% of the total value of land traded over the 1994–2016 period. In conclusion, AgriSA indicated that in terms land value and the potential of land, PDIs and Government ownership increased significantly. Sihlobo and Kapuya (Citation2017) reported that of 17.5 million hectares that have been transferred from white ownership since 1994, which equates to 21.2% of the 82.8 million of farm land in free hold. Sihlobo and Kapuya, further argued that through government and private acquisitions, the land reform target of 30% target is contrary to common belief.

Staatz (1998) defined agricultural transformation in a commercial farming context as the process by which individual farms shift from highly diversified, subsistence-oriented production to more specialized production units that are focused on the market and/or other systems of exchange (e.g., long-term contracts). In addition, this process involves a greater reliance on input and output delivery systems and increased integration of agriculture with other sectors of the domestic and international economies (Staatz, 1998). Delgado (Citation1995) defined agricultural transformation even narrower as a change from one structural stage to another. He stated that this change was naturally demonstrated by increasing specialisation in production, efficient use of purchased production inputs, greater resource inflows to farming and sizeable cuts in unit of production costs from technological change. In addressing the issue of transformation in the agricultural sector, the National Agricultural Marketing Council has developed a generic transformation guideline which outlines the main focus areas (NAMC, Citation2014). The NAMC outlines how industries collecting statutory levies, can fund and implement transformation activities. The NAMC further addresses issues of transformation in the agricultural sector through agricultural trust as outlined in the brief discussion that follows.

2.1. Agricultural trusts

The government liberalized the marketing environment through the Marketing of Agricultural Products Act of 1996. This policy shift abolished the marketing boards and vested the authority of regulating the marketing environment on those participating on the market. The assets of these marketing boards were given to the different agricultural industry trust to invest and fund function beneficial to the agriculture sector. The value of agricultural Trusts was sitting at approximately 2.4 billion in 2017. From the interest generated from the Trusts investments the Trusts spent approximately 10.4 million on transformation (see Appendix A for further details).

Majority of the South African industries collect statutory levies (see Annexure B), as provided for by the Marketing of Agricultural Products Act, No. 47 of 1996 (MAP Act), this follows the deregulation of the South African agricultural sector. A statutory levy is a charge per unit of an agricultural commodity at any point in the marketing chain between the producer and the consumer, which is collected to finance a number of functions, namely administration of the levies, information and liaison, transformation, research, consumer assurance and consumer education. According to the NAMC (2017), approximately 20% of the total levy income was spent on transformation as shown in Table 2. The different industries have over the years implemented on-going projects to support transformation of the agricultural sector. Smallholder farmers are assisted through training, mentorship, and enterprise development. The expenditure on transformation by industries of over the years is highlighted in Appendix C.

3. Methodology

We applied a modified version of the University of Pretoria General Equilibrium Model (UPGEM), which is solved using GEMPACK solution software described in Harrison and Pearson. UPGEM is a dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) model and it has the same theoretical structure as the Monash CGE model discussed in detailed by Dixon, Koopman, and Rimmer. A CGE model is an effective method of simulating the impact of policy implementation on an economic system (Decaluwe et al., Citation2000; Decaluwe & Martens, Citation1988). A dynamic CGE model can account for the accumulation and distribution effects and can enable welfare analysis over time. This dynamic model is crucial and appropriate as land reform and redistribution are long-term inventions. The general equilibrium core of the UPGEM is made up of a linearized system of equations describing the theory underlying the behaviour of different agents in the economy. Bohlmann et al. (2015) and Dixon et al. (2013) explain that the demand and supply equations in the UPGEM are derived from the solutions to the optimization problems that are assumed to underlie the behaviour of private sector agents in conventional neo-classical microeconomics.

Each industry minimizes cost subject to given input prices and a constant return to scale production function. Zero pure profits are assumed for all industries. Households maximize a Klein-Rubin utility function subject to their budget constraint (Correa & Kim, Citation1974; Pollak & Wales, Citation1969). Units of new industry-specific capital are constructed as cost-minimizing combinations of domestic and imported commodities. The export demand for any locally produced commodity is inversely related to its foreign currency price. Government consumption typically set exogenously in the baseline or linked to changes in household consumption in policy simulations.

CGE models are well suited to analyse policy questions such as the land redistribution policy in South Africa. The strength of the CGE methodology lies in its ability to capture the various inter-linkages in the real economy in great detail. The large amount of detailed data to be specified for the agricultural sector in this study, capturing its cost and sales structures along with a number of behavioural parameters, makes CGE the method of choice. We make two modifications from a standard UPGEM model. Firstly, we modify the standard database to contain a detailed treatment of the agriculture and food sectors while keeping other economic sector unchanged. The agricultural industry is disaggregated from a single into two industries representing the white commercial and black commercial operations. The food sector is also disaggregated into five industries namely the sugar, meat, cereals, dairy and beverages. Figure indicates the mapping process applied to obtain a modified UPGEM database.

As mentioned earlier the specifications in UPGEM recognize each industry as producing one or more commodities, using inputs combinations of domestic and imported commodities, different types of labour, capital and land. The multi-input, multi-output production specification is kept manageable by a series of elasticities in the nested production structure, illustrated in Figure . The elasticities reduce the number of estimated parameters required by the model. For an example, the optimizing equations determining the commodity composition of industry output are derived subject to a constant elasticity of transformation (CET) function, while functions determining industry demand for inputs are determined by a series of constant elasticities of substitutions (CES) nests (Figure ).

Figure 3. Nested production structure of a representative industry in UPGEM.

Given the importance of elasticities in improving the functionality and predictive power of the CGE model, we estimated new elasticities for individual agricultural products for use in the modified version of UPGEM model. The CES input demand elasticity also known as Armington (Armington, Citation1969) governs the substation between import and domestic goods while the CET export supply elasticity measures the producers’ decision to separate between goods destined for export and domestic market relative to price changes. Table presents the estimated elasticities used in the modified version of the UPGEM model.

Table 1. Estimated elasticities of the modified UPGEM model

3.1. Simulation design

The overarching motivation of this study is to quantify the expected socio-economic impacts of fast-tracking a land redistribution program in South Africa, either under the current or amendment legislation. It must be emphasized that our focus is limited to land redistribution pillar of the land reform that seeks to redistribute land for agricultural productive use. To achieve this, we applied a modified version of the UPGEM model that contains a detailed treatment of the primary agriculture and food industries. We also applied newly estimated trade elasticities to improve the functionality and predictive power of the model. In order to enable land redistribution simulations, we reconfigured the database to distinguish between white commercial and black commercial farming in the primary agriculture sector, thus creating two agricultural industries that reflects the dualistic structure of the South African agriculture sector. We achieved this by aggregating the individual primary agricultural industries into one sector and then distinguish between the agricultural outputs from white and black commercial operations, guided by industry production shares reported in the Statutory Measures and Industry Trust data collected and analysed by the NAMC in 2017.

We then formulate four scenarios that assess the impacts of fast-tracking the land redistribution through policy changes. The first is a Baseline scenario which is a business as usual scenario that reflects a naturally growing South African economy based on macroeconomic forecast data released by the South African Reserve Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The Baseline scenario illustrates the growth rate if the land reform program is maintained at a current pace without applying changes proposed in the 54th ANC conference and in the SONA 2018. The second scenario follows the principles and goals outlined in chapter 6 of the NDP that calls for an inclusive and transformed agricultural sector. We call this an Inclusive Policy Scenario. In the Inclusive Scenario, the land redistribution program is within the existing policy framework, however, an inclusive approach is adopted where both public and private sectors increase their efforts to redistribute agricultural land, at least meeting the 30 percent land transfer target by 2030.

The third scenario assumes a situation where the expropriation of agricultural land without compensation is implemented to fast-track land redistribution pillar of the land reform. The fourth scenario assume the same policy amendments as the third scenario- however, not only agricultural land is expropriated without compensation but all South Africa’s land is expropriated without compensation, implying a complete change in property rights structure in the country.

Key to the aforementioned scenarios are the imbedded assumptions that both white-owned and black-owned farming operation are operating on commercial bases, though the former is more capital intense relative to the latter. Secondly, it is assumed that there is a clear beneficiary selection criterion that avoids a situation of elite capture. Lastly, all policy scenarios assume that both white and black owned farming operations have access to markets required technical skills and funding coupled with effective and efficient post-settlement support packages. To illustrate the sensitivity of result to these assumptions, we simulate policies changes with assumption in places and policy changes where all assumptions do not hold. In other words, we illustrate through sensitivity analysis, what would be the impacts if no transfer of skills, market access and post-settlement support is provided.

4. Results and discussions

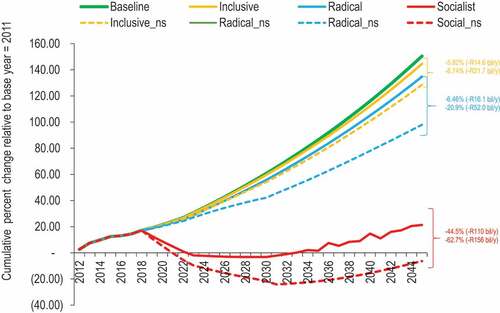

The results presented in Figure show the expected impacts of different policy scenarios on the country’s socio-economic welfare. Firstly, the baseline scenario clearly indicates that the economy will continue to grow but at a relatively slow pace which is way below the required pace prescribed in the NDP, thus implying the status quo is not sustainable. Our findings are congruent with the findings of Mukarati et al. (Citation2020) who conducted a similar study using CGE modelling although analysing the impact of the current land redistribution approach of “willing buyer—willing seller”. Though the economy will grow by accumulative of 47 percent relative to 2017 level, it is far low to generate the employment and boost the exports required to alleviate poverty in the country. This baseline results suggest that over the medium term there would be increasing incidence of labour unrest because of increasing unemployment rate, widening inequality, which could heighten the social unrest in the country. Furthermore, the lacklustre performance of agriculture sector and the economy-wide contagion effects due to agricultural land redistribution can be explained by he fact that most beneficiaries of he land reform programme do not have means and capacity to fully and productively utilise the land. The contraction of the agriculture sector is transmitted into other sectors of the economy through the multiple backward and forward linkages that the sector has with the rest of the economy.

Under the Inclusive policy scenario, the welfare declines by 5.92 percent below the baseline scenario indicating that fast-tracking the land redistribution through change of ownership from the white to black commercial farmers will incur adjustment costs in the next 25 years. It is important to emphasize that the low adjustment costs under the Inclusive policy scenario is due to the fact that the fast-track land redistribution is market oriented and happening within the current legislations that does not include expropriation without compensation. Moreover, the Inclusive scenario assumes that they will be appropriate post-settlement support mechanisms and unlimited access to finance and markets by new black commercial farmers. It has been observed that comprehensive support to emerging farmers, including access to finance, is indispensable if the land reform programme is to success in South Africa (for example, Mtombeni et al., Citation2019). In addition, the Inclusive scenario only affects agricultural land, which limits the direct impact on other sectors of the economy. The welfare loss reflects the indirect effects of redistributing agricultural land from previous landowners to black emerging farmers. The reduction of wealth from white farmers through taking away agricultural land does not immediately lead to the transference of wealth to black farmers.

When the post settlement support, transfer of skills, access to markets and funding are not provided to new black commercial farmers, the adjustment costs is relative high under the Inclusive policy scenario, increasing to 8.74 percent below the baseline scenario. This clearly indicates the sensitivity of the results to support mechanisms that will be provided to new black farmers under the fast-tracked land redistribution programme. This finding also suggests the importance of aligning the land redistribution debate with support packages in the agricultural sector to ensure that the economy and food supply system are minimally adversely disturbed when the land is transferred.

The results in Figure also indicate the impacts when agricultural land (i.e. Radical Scenario) and all land (i.e. Social Scenario) are expropriated without compensation in the country. Under these scenarios the welfare loss is significantly high indicating the economy will be significantly negatively impacted in the short to medium term. When the support mechanisms for new black farmers are not provided the impacts are even more severe on the economy under both the Radical and Social scenarios. The results indicate that the Social scenario provides a worse case situation while the Inclusive scenario provides somehow a moderate situation that still reduces the welfare but can significantly assist in addressing the slow pace of land redistribution in the agricultural sector. The adjustment costs found under the Inclusive Scenario, particularly if the support packages to new black farmers are provided can be argued to be relative moderate but necessary to achieve a developmental goal of addressing the unjust of historic laws.

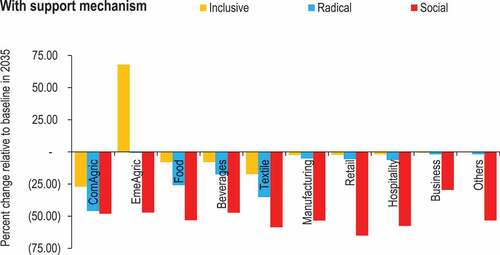

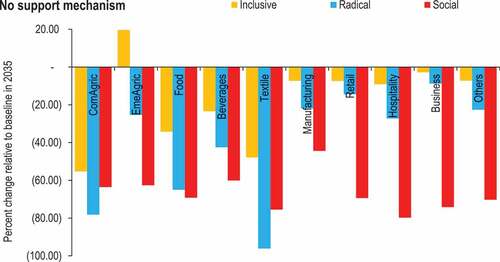

The sectorial results on individual industry outputs indicate that all three-policy scenarios lead to negative impact on majority of industries. Looking at Figure , the impact on food under the Inclusive Scenario is relatively moderate reducing the food output by nearly 8 percent relative to the baseline over the next decades if land is redistributed from white to new black farmers. The decline in food output can be attributed to infrastructure, finance and market networks that are currently limited for black farmers. In addition, product quality issues could be a problem in the short to medium term for new black farmers as they acquire the necessary skills and network needed to prosper in the food sector. The impact on food and other industries becomes significantly higher as food output declines by over 25 percent under the Radical Scenario and close to 50 percent under Social Scenario. This implies that over a quarter of current food production in the country could be replaced by imports if Radical land redistribution scenarios is implemented, and this could increase to 50 percent under Social Scenario, with all he attendant food security ramifications of relying on imports to supply the bulk of the country’s food needs.

Figure illustrates the sensitivity of sectorial results on the assumptions of skills transfer, market access, and post-settlement support mechanisms. If these support packages are not provided, the food and other industry output will be significantly affected on average reducing by over 34 percent under the Inclusive Scenario; 60 percent under Radical scenario and over 80 percent under Social scenario.

5. Conclusion and policy advisory

It should be accepted that there would be losers and winners in the process of land reform in South Africa just like in any welfare economics endeavour. Moreover, the land reform process cannot be abated, as it is a developmental imperative in South Africa enshrined in the constitution several other derivative policy documents. Thus, regardless of policy option chosen or modalities thereof, there will be adjustment costs.Footnote1 Policy makers and the South African society would be advised to choose the path with minimum costs, including economic and social costs. The results of this analysis show that the Inclusive Scenario is the most appealing option. Furthermore, it can be concluded from the evidence provided by the modelling that the whole South African and the agriculture sector would continue to grow in the future regardless of the policy option chosen, except for the most radical Socialist Scenario. Another unintended consequence of land expropriation would be weakening of South Africa’s agricultural products competitiveness in the export markets, at least in the short to medium term. Exports have been key drivers of growth in the South African agricultural sector over time.

The analysis also revealed that capacity building and maintenance of existing human capital and skills are critical for the success of the land reform programme, especially in the light of expropriation which could lead to an exodus of agricultural and farming skills. The need for proper transfer of skills and training of new agricultural landowners are critical for the continued success of the sector and minimising disruptions in production. Policy makers should be mindful of the need for appropriate post-settlement support for the land reform process to be sustainable and for the agricultural sector to continue playing the role it is playing in job creation, poverty alleviation and ensuring food security.

Another critical factor for success of the land reform process is the creation of a conducive environment for the new entrant farmers to access markets for both inputs and produce. Such an enabling environment includes, but not limited to, provision infrastructure, input markets and information. These prerequisites to a successful take-off of the entrant farmers could be achieved with existing public resources through a reprioritization budget allocation and dismantling the anti-competitive network of established players.

A caveat to policy makers is to avoid populist policy options that have been shown that they could have detrimental economic ramifications in the long run such as the Socialist Scenario.

A weakness of the study is that simulations did not take into account technology improvements, which could soften the expected adjustment costs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the organizers of the ARC-Land Bank-NAMC Research Symposium 2018 held 13 June 2018 at the Maslow Hotel in Menlyn, Pretoria, South Africa for their invitation to present the findings of the work reported in this paper. The symposium is an annual platform to present selected research outputs on topical issues convened jointly by the Agricultural Research Council (ARC), the Land Bank and the National Agricultural Marketing Council (NAMC). The authors would like to single-out Dr Simphiwe Ngqangweni of the NAMC, amongst the organizers for his invaluable inputs on an earlier draft of the paper. His inputs are hereby acknowledged and recognized for improving the paper.

Furthermore, the authors would like to acknowledge the inputs of participants at the Agricultural Economics Association of South Africa (AEASA) 2018 annual conference held in Somerset West in Cape Town, South Africa where the paper was presented as an oral presentation. The questions and comments received at the conference helped refine the paper. We would also like to thank Professor Johann Kirsten for his thorough questions and inputs during the conference, especially in testing the validity of the methodological approach used.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This is the cost to the country of altering its level of agricultural output as a result of the shocks brought about by the land reform process. See, Hamermesh and Pfann (Citation1996) for a detailed discussion on adjustment costs.

References

- AgriSA, 2017. Land audit: A transactions approach. Agriculture, South Africa (AgriSA). www.agrisa.co.za. (Accessed on 22 February 2018)

- Akinola, A. O., Kaseeram, I., & Jill, N. N. (Eds.). (2021). The new political economy of land reform in South Africa. Palgrave Macmillam.

- ANC. (1994). The reconstruction and development programme (RDP): A policy framework. In African national congress. South Africa.

- Armington, P. S. (1969). A theory of demand for products distinguished by the place of production. IMF Staff Papers, 16(1), 159–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/3866403

- Bernstein, H. (2013). Commercial agriculture in South Africa since 1994: Natural, simply capitalism. Journal of Agrarian Change, 13(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12011

- Conradie, B. (2019). Designing successful land reform for the extensive grazing sector. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 47(2), 1–12.

- Correa, H., & Kim, S. B. (1974). Statistical estimation of utility functions. De Economist, 122(5), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01680064

- Cousins, B. (2000). Introduction. In B. Cousins (Ed.), At crossroads: land and agrarian reform in South Africa into the 21st century. National Land Committee/PLAAS, University of the Western Cape. pp. 3.

- Davis, R., Kosec, K., Nkonya, E., & Song, J., 2020. Global land reform experience: A review for South Africa. SA-TIED Working Paper 98.

- Decaluwe, B., Dumont, J.-C., & Savard, L., 2000. Measuring poverty and inequality in CGE MODEL. Working Paper 99–20. Quebec, Centre de recherché eneconomie et finance appliqués, Universe Laval.

- Decaluwe, B., & Martens, A. (1988). CGE modelling and developing countries. A concise empirical survey of 73 applications to 26 countries. Journal of Policy Modeling, 10(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/0161-8938(88)90019-1

- Delgado, C. (1995). The role of smallholder income generation from agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. Achieving food security in Southern Africa: New challenges, new opportunities, 1, 145–173.

- Department of Land Affairs (DLA), 1997. White paper on South African land policy. Pretoria: DLA.

- Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR), 2017. Land audit report. www.ruraldevelopment.gov.za. (Accessed on 22 February 2018)

- Ding, C. (2003). Land policy reform in China: Assessment and prospects. Land Use Policy, 20(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(02)00073-X

- Dlamini, T. S., Verschoor, A., & Fraser, G. C. (2013). Exploring options in reforming South African land ownership: Opportunities for sharing land, labour and expertise. Agrekon, 52(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2013.770951

- El-Ghonemy, M. R. (2003). Land reform development challenges of 1963 – 2003 continue into the 21st century. Land Reform, 2, 33–42.

- Greyling, J. C., Vink, N., & Mabaya, E. (2015). South Africa’s agricultural sector twenty years after democracy (1994 to 2013). Professional Agricultural WorkersJournal (PAWJ), 3(1), 1–14.

- Gwebu, J. Z., & Matthews, N. (2018). Metafrontier analysis of commercial and smallholder tomato production: A South African case. South African Journal of Science, 114(7/8), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/20170258

- Hamermesh, D. S., & Pfann, G. A. (1996). Adjustment costs in factor demand. Journal of Economic Literature, 34(3), 1264–1292.

- Hendrick, S. (2014). Food security in South Africa: Status quo and policy imperatives. Agrekon, 53(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2014.915468

- Karaan, M., & Vink, N. (2014). Agricultural rural development in the post apartheid era. In H. Bhorat, A. Hirsch, R. Kanbur, & M. Ncube (Eds.), The oxford companion to the economics of South Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 3.

- Kirsten, J. (2006). Socio-economic dynamics of the South African agricultural sector. South African Institute of International Affairs. Trade Policy riefing No. 10.

- Kirsten, J., Machethe, C., Ndlovu, T., & Lubambo, P. (2016). Performance of land reform projects in the north west province of South Africa: Changes over time and possible causes. Development Southern Africa, 33(4), 442–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2016.1179104

- Kirsten, J., Van Rooyen, J., & Ngqangweni, S. (1996). Progress with different land reform options in South Africa. Agrekon, 35(4), 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.1996.9524838

- Lahiff, E. (2001). Land reform: Is it meeting the challenge. In Policy brief no (Vol. 2). PLAAS, University of the Western Cape.

- Lipton, M. (1977). South Africa: Two Agricultures? In F. Wilson, A. Kooy, & D. Henrie (Eds.), Farm labour in South Africa. David Phillip. pp. 1.

- Lipton, M. (1993). Land reform as commenced business: The evidence against stopping. World Development, 21(4), 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(93)90116-Q

- Lyne, M. (2014). The F.R. tomlinson memorial lecture: Two decades of land reform in South Africa: insight from an agricultural economist. Agrekon, 53(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2014.975413

- Matseke, C. (2021). Land reform in South Africa. He Thinker, 88(3), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.36615/thethinker.v88i3.601

- Mkhabela, T. (2018). Dual moral hazard and adverse selection in South African agribusiness: It takes two to tango. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 21(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2016.0177x

- Mtombeni, S., Bove, D., & Thibne, T., 2019. An analysis of finance as a barrier to entry and expansion for emerging farmers. Working Paper cc2019/01. Competition Commission. The Department of Trade and Industry. Pretoria: South Africa.

- Mubecua, M. A., Wiseman Mbatha, Mbathat Mw, Mpanza, S. E., Khulekani Tembe, Wiseman Mbatha, M., & Tembe Sk, S. (2020). Conflict and corruption: Land expropriation without compensation in South Africa. African Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, 9(2), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.31920/2634-3665/2020/S9n2a3

- Mukarati, J., Mongale, J. P., & Makhomba, G. (2020). Land redistribution and the economy. Agricultural Economics – Czech, 66(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.17221/120/2019-AGRICECON

- NAMC, 2014. Generic transformation guidelines, July. Accessible at www.namc.co.za. (Accessed 3 February 2016)

- National Treasury. 2021. Budget review. national treasury. 24 February 2021. Pretoria: Republic of South Africa

- Ngam, R. N. (2021). Government-driven land and agrarian reform programmes in post apartheid South Africa – A brief history (1994-2021). African Sociological Review/ Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 25(1), 131–152.

- Ngarava, S. (2020). Impact of the fast track land reform programme (FTLRP) on agricultural production: A tobacco success story in Zimbabwe? Land Use Policy, 99(c), 105000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105000

- Oelofse, S. H., & Nahman, A. (2013). Estimating the magnitude of food waste generated in South Africa. Waste Management and Research, 31(1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X12457117

- Pollak, R. B., & Wales, T. J. (1969). Estimation of the linear expenditure system. Econometrica, 37(4), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.2307/1910438

- Rugege, S. (2004). Land reform in South Africa: An overview. 32 International Journal of Legal Information, 283, 1–28.

- Sihlobo, W., & Kapuya, T. (2017). Land policy try to solve imaginary issues at expense of real problems. In Newspaper article. Business Day Live. pp. 6.

- Sihobo, W., & Kirsten, J. (2021). How to narrow the big divide between black and white farmers in South Africa. He Conversation, 3. 30 November, 2021.

- Sikor, T., & Müller, D. (2009). The limits of state-led land reform: An introduction. World Development, 37(8), 1307–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.010

- Stats, S. A. (2021). Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 1: 2021. Statistical release P0211> Statistics South Africa. Republic of South Africa.

- Van Zyl, J., Nel, H. J. G., & Groenewald, J. A. (1988). Agriculture’s contribution to the South African economy. Agrekon, 27(2), 1–9.

- Wegerif, M. (2022). The impact of Covid-19 on black farmers in South Africa. Agrekon, 61(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2021.1971097

- Wiig, H., & Øien, H. (2013). Would smallbe more beautiful in the South African land reform? In N Land Tenure reform in Asia and Africa (pp. 80–104). palgrave Macmillan.

- Zantsi, S., Mulanda, S., & Hlakanyane, L. (2021). Small-scale agriculture, land reform, and government support in South Africa: Identifying moral hazard, opportunistic behaviour, and averse selection. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies –Multi-Inter-and Transdisciplinarity, 1, 1–26.