Abstract

Disasters and crises have been part of the human experience since time immemorial. They may be unpredictable, but important steps can be taken before a disaster occurs to minimize the threat of damage. This study seeks to explore the level of disaster (un)preparedness through women activities in the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) programme during Cyclone Idai at Tongogara Refugee Camp (TRC) in Chipinge, Zimbabwe. The study argues that refugee women, more than men, were more vulnerable to the effects of Cyclone Idai due to unequal distribution of the scarce WASH facilities at the camp. Drawing on the findings from qualitative research where data were collected through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and participant observations, women were found to be more susceptible to the impacts of Cyclone Idai than men, due to inequity in resource distribution. Using a feminist political ecology framework to analyze the role of women during disasters, the study identified five themes; gender equality, access to WASH, health, decision making and participation that helped to show the state of preparedness and response by women. The results reveal a high level of unpreparedness on the part of the government in implementing disaster mitigation measures as very little was done in the pre-Cyclone Idai disaster period in terms of training and information dissemination at TRC. The study concludes that in emergency situations, women are more exposed than men, hence the need for a gender sensitive response strategy.

1. Introduction

Disaster preparedness is key to development and involves reducing the vulnerability of households and communities in disaster-prone areas and improving their ability to cope with the effects of disasters (Stikova, Citation2016). It strengthens the capacities of national governments in disaster response defining their role and mandate in national disaster plans (Mukanganise, Citation2011). Disaster preparedness gives room to operative, accurate and synchronized planning that complements the efforts of national societies, household and community members while increasing their overall effectiveness. However, women’s views on disaster risk reduction are barely recognized although they bear major workload and family burden (Alam & Rahman, Citation2014). This absence of women’s substantive representation in decision-making bodies causes crises to them (Bradshaw & Fordham, Citation2013), forcing them to take a confrontational stance over challenges in a bid to overcome such (UNEP, Citation2016). Thus, women`s adaptive capacity to undo the challenges and constraints that impinge their lives act as a steppingstone to recovery (Mulyasari & Shaw, Citation2013). The scarcity of safe drinking water and damage to sanitation facilities remain a challenge, leaving women with the burden of looking for alternative water sources. Hence, this study endeavors to explore the state of preparedness to the Cyclone Idai induced floods by the government in response to the Cyclone Idai induced floods that hit Chipinge on the 15th of March 2019, with a special focus on the role of refugee women in WASH activities in TRC.

1.1. An overview of cyclone Idai induced floods

Chipinge is located in the eastern part of the Manicaland Province of Zimbabwe, where heavy rains “caused massive destruction” (United Nations Environment Annual Report, Citation2019). Cyclone Idai made landfall as a Category 3 storm, posing a serious threat to both life and property (Shroeder, Citation2019). The storm was made catastrophic by the extremely high atmospheric moisture content leading to heavy rains, on top of an immediately prior storm which had already caused flooding in Mozambique (Chatiza, Citation2019). The issue with Cyclone Idai was less the presence of high winds than the sheer amount of water pushed into the area through overlapping storm systems and coastal surge over an area of low-lying topography (United Nations Environment Annual Report, Citation2019). In Zimbabwe, Chipinge and Chimanimani Districts were the worst-hit, due to the extensive damage to major roads and bridges which made some areas impassable. Power networks were severed while thousands have lost their homes and property damaged. The refugee community in TRC were not spared.

Mushanyuri and Ngcamu (Citation2020) opines those cyclones are not a strange phenomenon to Zimbabwe, since the country has been affected by several cyclones before. For instance, in February 2000 Zimbabwe experienced Cyclone Eline induced floods and winds which left a trail of destruction in the country. The worst affected parts of the country include Manicaland and some parts of Masvingo. This was followed by Cyclones Japhet (2003), Dineo (2008) and Idai (2019). There is need to explore the mitigation, preparedness and response measures that stakeholders, including women, put in place, in preparation to the occurrence of cyclone related disasters. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to assess the role played by refugee women in the TRC in preparation for the landfall of Cyclone Idai.

2. Literature review

2.1. Understanding disaster preparedness

Disaster preparedness involves the mobilization of resources to alleviate the risk of future catastrophes. It is the responsibility of the entire society and requires active participation of the local community (West et al.,). A disaster preparedness plan contains the responsibilities people and organizations have before, during and after a disaster. Disaster preparedness plays a critical role in mitigating the adverse health effects of natural disaster. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Citation2009) defines disaster preparedness as knowledge, capabilities, and actions of governments, organizations, community groups, and individuals to effectively anticipate, respond to, and recover from, the likely impacts or hazard events. Preparedness efforts at government level include early warning systems, contingency plans, evacuation routes, and public information dissemination. An individual’s emergency preparedness and related behaviour is likely to be affected by perceived risk, disaster preparedness knowledge, prior disaster experiences, and certain sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, age education and family income (Ngarava et al., Citation2021).

For a disaster preparedness campaign to be effective, it must respond to all the phases to help emergency managers prepare for, and respond to a disaster for a comprehensive disaster management. This study looked at the first three phases as they relate to the research. Mitigation phase that involves steps to reduce vulnerability to disaster impacts such as injuries and loss of life and property (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Citation2009), were analyzed. Mitigation that involves steps to reduce vulnerability to disaster impacts such as injuries and loss of life and property, is essential in making the community resilient to catastrophic events, is essential in the pre-emergency phase. Preparedness focuses on understanding how a disaster might impact the community and how preparedness campaigns and training can build the community’s response to recover from a disaster (Nhamo & Chikodzi, Citation2021aa). According to H et al. (Citation2019) the response phase addresses immediate threats presented by the disaster, including saving lives, meeting humanitarian needs (food, shelter, clothing, public health and safety), clean-up, damage assessment, and resource distribution.

A disaster may be caused by a natural hazard such as a flood. Thus, being organized, aware of procedures and having a plan in place before a disaster occurs, will lessen the extent of the damage and is the best insurance against losing life (Chatiza, Citation2019). Disaster preparedness requires comprehensive development plans and priorities, and has proved to be a mammoth task for most developing countries whose budgets are insufficient for such phenomena as strong public health systems, universal access to clean water and effective sanitation (World Health Organization, Citation2015). The golden rule for successful disaster management is to increase awareness, develop action plans and practice them. Waiting for a disaster to strike before taking action is not the right way to plan. Communicating and relationship building between disaster management stakeholders will have positive effect in determining the resiliency of communities throughout an event (Mukanganise, Citation2011). Hence training and practicing disaster response is a vital part of disaster preparation.

When people experience a disaster, they may react differently compared to how they would usually respond to normal situations (Nhamo & Chikodzi, Citation2021b). It is also common for people to show signs of stress after exposure to a disaster, making it important to monitor the physical and emotional health of those affected as well as those responding to the needs of others (Chatiza, Citation2019). Although people react differently to disasters, some may suffer from serious mental or emotional distress (Jannatul & Dwijen, Citation2019), thereby calling for psychosocial support to minimize negative outcomes. This requires evidence-based reduction of risks and building the capacity of potential victims of disaster and their institutions (Miletto et al., Citation2019). Institutional and infrastructural changes to better manage and respond to disaster risks are key to disaster management strategies.

Research show that disaster can be devastating in the developing world that are unable to respond effectively to them, inflicting on humanitarian efforts to meet the needs of affected populations (UN, 2017; Chitongo et al., Citation2019). Khurshed and Habibur (Citation2019) opines that a major challenge in the disaster situation is the scarcity of safe drinking water and damage of sanitation facilities which poses a threat to the surviving people. This might result in the outbreak of waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea, dysentery, cholera, skin disease and allergy (Haque et al., Citation2016).

2.2. Disaster and preparedness and gender

To improve on preparedness, governments need to understand the occurrence and frequency of natural hazards, risks, vulnerabilities and their potential impact on people and assets (Hemachandra et al., Citation2021). This shows that due to higher levels of vulnerability, women are usually affected more following flooding. Despite being more vulnerable to flooding compared to men, most disaster relief efforts are in most cases not responsive and sensitive to the basic needs of women, which further jeopardizes their lives and safety (Flynn & Sherman, Citation2017). Chitongo, et al (Citation2019) views disaster as a gendered-constructed process, hence to respond to those in need during a disaster, gender needs to be considered as an integral factor. Gender inequality make women disproportionately vulnerable and decrease their coping and adaptive capacity in disaster situations (Khurshed & Habibur, Citation2019). Women are the most vulnerable as a result of their gender roles and responsibilities, and the discriminatory social norms and practices, and acceptance of domestic violence, which further create barriers to their mobility and economic empowerment.

2.3. Background to the study area

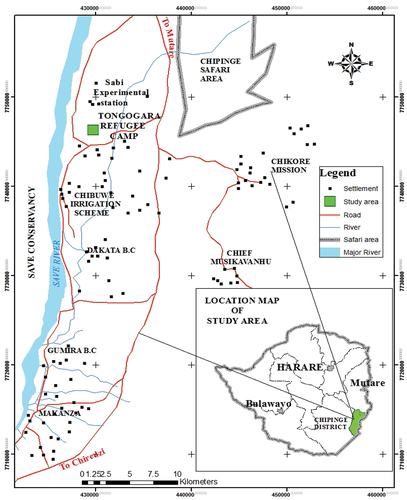

The study area is the Tongogara Refugee Camp (TRC), which is situated in the South western part of Chipinge District in Zimbabwe (). The TRC is located in Natural Region V which receives very low rainfall (300–600 mm/annum) and is very dry (UNHCR & WFP, Citation2014) making access to water very difficult. Water scarcity negatively impacts on women, who bear the brunt of sourcing water for their households (Calderón‑Villarreal et al., Citation2022). Today the camp hosts over twenty-one thousand refugees from Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo and lately Mozambique (UNHCR, Citation2021). People of different social, cultural and religious backgrounds are living together. The camp is run by UNHCR, an arm of the United Nations, together with Zimbabwe’s Department of Social Welfare (DSW), who represent the host Government (UNHCR & WFP, Citation2014). The camp is divided into nine residential sections. Initially, refugees were settled according to their countries of origin, but with the continued influx, they are now settled as they come. There is a critical shortage of water and sanitation facilities in the camp. While the camp is dotted with pit latrines, the continued influx of refugees has resulted in an insufficient number to serve the growing population (Calderón‑Villarreal et al., Citation2022), leading to the practice of open defecation (OD). A wildlife conservancy and the Save River border the camp to the west, where predators like lion, hyena, leopard and crocodiles` parade. This makes OD very risky at night. To the north, are Settler Farmers whose church is used to accommodate refugees whenever there is a flood (Spiegel & Mhlanga, Citation2022). The main source of water is groundwater, extracted using 12 manually operated bush pumps, and two solar-powered and two electric-powered boreholes (Spiegel & Mhlanga, Citation2022), which have since been damaged by floods. The solar panels were stolen in February 2019 and were yet to be replaced by the time this research study was conducted (March 2020), forcing women to look for alternative water sources. At the time when this research study was conducted, the water allocated per person per day in the camp did not meet the stipulated Sphere minimum standards of 20 litres per person per day (Association, Citation2018). However, even though a number of researchers have carried out studies in refugee settings on WASH, elsewhere, (Inter Sector Coordination Group, Citation2020; Sang, Citation2018; OSCE, 2020; Calderón‑Villarreal et al., Citation2022; Spiegel & Mhlanga, Citation2022; Nhamo & Chikodzi, Citation2021a; Chatiza, Citation2019; Mucherera et al., Citation2021), but little has been done to analyze the role of women in WASH disaster management in a refugee camp, which justifies our focus on TRC. In the current study, we are using a Feminist Political Ecology theoretical lens.

In the TRC, refugees are required to build their own toilets. However, most households do not have toilets (Calderón‑Villarreal et al., Citation2022). Recently, NGOs and the Zimbabwean government provided refugees with materials for make-shift latrines after their toilets had been swept away by floods. During the time when Cyclone Idai swept through the camp, the nearest water point that was accessible to refugees was in Maronga Village, which is three kilometres away. In the TRC, WASH projects are run by two NGOs, namely GOAL Zimbabwe (GOAL) and Terres de homes (TDH), which monitor the implementation of the projects. TDH is responsible for hygiene and disease surveillance in the camp, while GOAL addresses the availability of water and sanitation facilities. These NGOs ensure that all refugees participate in project implementation and their views considered without discrimination. The WASH projects that are being implemented in the camp include construction of latrines, borehole drilling and maintenance, Participatory Health and Hygiene Education (PHHE), formation and revival of Community and School Health Clubs (CHC), training and capacity building of Health Promoters (HP). The two NGOs also carry out disease surveillance and control, water testing and the supply of water treatment tablets in the camp.

In Zimbabwe, the flood management process is multi-functional, involving several sectors. It is the Central Government that initiates disaster preparedness programmes through the Civil Protection Unit (CPU), while local administration takes the responsibility for implementing and maintaining its effectiveness (Gwimbi, Citation2007; Mukanganise, Citation2011; Mucherera, et al., 2021). At national government level, the CPU is the coordinating body and is empowered by the Civil Protection Act which spells out the legal instruments for disaster management and the powers vested in individuals as well as organizations in the case of disasters (Chatiza, Citation2019). The CPU can call on any government or private sectors to assist wherever such assistance may be required (Nhamo & Chikodzi, Citation2021b). In the past, there has been a tendency to assess the disenfranchised refugees as an ethnically homogeneous community whose cohesiveness was fostered by their background, making it difficult to manage. In its quest to establish the impact of Cyclone Idai and the state of preparedness on the part of government, the study had to include the host community of Maronga Village as they were equally affected by the floods.

2.4. Theoretical framework

Taking a political ecology stance, this chapter uses a gendered political ecology (Feminist Political Ecology) framework to explore the intersectional inequalities relating to women`s participation in water and sanitation and related emotional responses. There is a growing body of literature on water and sanitation in refugee camps (UNHCR, Citation2017; WHO/UNICEF, Citation2020; WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, Citation2010), which has been reviewed elsewhere. However, despite the intensification of global concerns over water and sanitation access by refugees and availability and the increasing importance of women participation, there has been remarkably little academic research into the role of women in WASH activities and water scarcity (Cole, Citation2017), especially in refugee camps. The purpose of Feminist Political Ecology (FPE) is to understand the complex relations between nature and society through an analysis of access and control over resources and their implications for the environment (Resurrección & Sajor, Citation2015). FPE, a growing field of political ecology (Elmhirst, Citation2015), treats gender as “a critical variable in shaping resource access and control, interacting with class, caste, race, culture, and ethnicity to shape processes of ecological change,” (Rocheleau, Thomas-Slayter, and Wangari, Citation1996: 4). It considers a range of environmental rights and responsibilities, including access to water resources and how those who are most vulnerable in society are impacted by environmental change (Hanson & Buechler, Citation2015). Furthermore, FPE scholarship privileges the knowledge of those most affected or marginalised by neoliberal, colonial or patriarchal systems in which water and sanitation policy and practice are carried out (Cole et al., Citation2016, p. 33). FPE explores how multiple forms of social inequality intersect with nature. Hence, proximity to a water source is added to competition from a patriarchal culture, ethnicity and life stage as factors that reinforce gender inequality.

The unequal gendered power relations embedded in WASH programmes have been well studied (Cole, Citation2017), but there has been a failure to consider differential impacts or consequences of resource shortages on men and women. Scholarly work on the environmental impacts of WASH have been largely gender blind, failing to acknowledge the differences between men and women and frequently reinforcing gender stereotypes. FPEs have a tendency of considering communities as largely homogeneous (Elmhirst, Citation2018). However, the intersectionality of institutions shows that women are not homogeneous. Women encounter stress, worry, suffering and embarrassment, as well as physical and financial difficulties of water access (Collins, Citation2015), in different proportions. It is argued that emotions are an important key to knowledge and a rich source of understanding especially among oppressed women (Olivius, Citation2014). The emotions expressed by refugee women in this study add to our understanding of the consequence of gender inequality in WASH activities. Thus, equitable participation creates opportunities for women in water management that may have negative impacts on other vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and persons with disability who often rely on women’s domestic and caretaker roles.

Just like in many societies, women are responsible for domestic water provision and management. These roles are often “naturalised”, unpaid, and unrecognised meaning that women have to live with issues of water scarcity and contamination on a daily basis (Mollett & Kepe, Citation2018). Although their water work is part of productive labour, lacks visibility, yet integral to water supply, women are frequently excluded from water distribution policy and decision making (Elmhirst, Citation2011). This paper considers not only how women bear a disproportionate share of the hidden costs of WASH resource shortages in emergency situations, but also unpacks the differential impact on different groups of women and explores how they managed to overcome such challenges. Thus, the FPE framework will assist in assessing the gender-water nexus and examine how gender norms are negotiated in the course of environmental struggles, as Elmhirst (Citation2015) suggests. In the context of TRC, we investigate the gap between gender-based policy rhetoric and actual outcomes, identify the uneven power relations between men and women in WASH, and offer recommendations for more equitable gender participation in WASH activities in the camp.

3. Methodology

2019 and March 2020. A pilot study to test the interview questions was conducted in September 2018, as the researcher was still gathering information on the topic, with the final guide being approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Free State in July 2019. Permission to conduct research in the TRC was granted by the Ministry of Public Service Labour and Social Welfare, while informed written consent was obtained from the participants, who were informed that participation was voluntary. The study is based on a qualitative research design. Qualitative data were collected from eight Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with an average of 8 participants each. Sixty-eight interviews, five key informant interviews, and observations and informal conservations with the purposefully sampled households were also conducted. This allowed for the triangulation of information from a diversity of sources while addressing the gender inequality in this water scarce environment. Prior to the FGDs, informed consent was obtained from the participants by the principal researcher. The research focused on the lived experiences of women. Firstly, this was done because women are primarily responsible for the collection, treatment, and household management of water in their communities. Secondly, men were often reluctant to talk about issues related to domestic water use, stating that their wives or women in general were responsible for fetching water and were therefore more knowledgeable about household water subtleties s shown in .

Table 1. Demographic information for FGD participants

Dealing with war displaced women refugees from diverse backgrounds and ethnic origins is no easy feat. For instance, issues of culture and language barriers are among the major challenges we faced during data collection. However, we circumvented this difficulty by engaging research assistants chosen on the basis of their knowledge of the camp and proficiency in KiSwahili, which is a lingua franca in the camp. Interview and focus group participants were purposefully sampled using inclusion/exclusion criteria, an approach known to be effective when a researcher seeks to uncover knowledge and processes known only by a certain group of subjects rather than the entire population (Adams et al., Citation2018; Tongco, Citation2007). Purposive sampling was used to select participants according to country of origin and to get equal representation from all sections. Snowball sampling was also used as it saved on time. All interviews and FGDs were conducted in confidentiality, and the names of the respondents were withheld by mutual consent. The interviews generally lasted forty-five to ninety minutes, with the proceedings being recorded, noted and transcribed for analysis.

3.1. Data collection and analysis

Along with secondary data, information was collected through 68 household interviews conducted in the nine residential sections found in the TRC, and five in-depth interviews with key informants from local NGOs (GOAL Programme Manager and Project Officer; and TDH Project Officer), and government representatives (camp administrator and engineer). Of the eight FGDs conducted, seven had eight women participants each, representing seven major countries present in the camp (Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Mozambique), whilst the eighth group was unique in that it had nine participants across the gender and selected national divides of TRC refugees. This brought the total number of FGD participants to sixty-five. The grouping was purposive in order to have women of the same language and culture together. The sample size was determined by the need to have a manageable groups where all participants had an opportunity to contribute to discussion. A FPE approach to documentation was employed to critically analyze the role played by women in WASH activities during the disaster. This helped to capture the ideas, concerns, feelings and experiences of the affected refugee community who bear the brunt of WASH shortages. The approach ensured how information on issues of preparedness and awareness were disseminated as it seeks to account for the part played by the CPU in this intervention.

Data from interviews (i.e., household interviewees, key informants, focus group participants), were transcribed and analyzed based on interlocuters and themes that were identified through a grounded theory approach that allowed dominant themes to emerge from the transcripts (Patton 2005, Charmaz and Belgrave Citation2012; Adams et al., Citation2018). The constant comparison analysis method, based on grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) was used in the data analysis. This requires researchers to examine and compare one piece of qualitative data (sentences and themes, etc.) to another piece of data. Major themes were identified from the empirical data (i.e., within the transcripts) and summarized in matrix form, in order to identity themes across transcripts, as well as common subthemes. The theoretical framework determined the themes deducted from the data. Themes and subthemes were them applied consistently to quotations across transcripts (i.e., coding). Coding helped to condense the amount of text, improve data organization, and further refine the most salient themes. The FPE theoretical framework was used to analyze data that accrued in these thematic areas, screening it through the themes of gender, access, health and decision-making lenses. For accountability and to ensure the reliability of the results, verification of the findings was done by triangulation between different types of sources that includes the key informants, participant interviewees and FGD participants. The reading of transcripts was done several times (on average 10 times).

4. Results

The study findings were arranged under two major sub-headings: Disaster Preparedness, mitigation and response to WASH.

4.1. Disaster preparedness and response

The demographic data of the participants in FGDs show that only a few men participated. The age of participants also had a bearing on the participation of respondents in disaster preparedness as those physically fit, who are still active, got the information early while the aged and disabled got the message late. The demographic data shows that there were more female participants than male 89.2% who attended the FGDs in the camp. This is because the research was targeting female participants who were purposefully sampled, hence the 10.8% recorded on the male participants was from the country leaders who formed the eighth group with nine participants. Of the 65 female participants who attended the FGDs, the majority were within the 26–35 age group, which is the most active in the camp. The findings also show that the single mothers were among the greatest percentage in the camp who were involved in the evacuation of people from the camp to Stage II, a displacement centre in time of floods in the Settlers. The 4.6% who represented the other group might be composed of the widowed and the divorced who were among the least on the list who were purposefully selected to attend the FGDs. The cosmopolitan nature of the camp where several languages are being spoken in the camp, shows the barriers experienced during evacuation as people of the same ethnic group moved together.

The dissemination of the early warning information did not reach the camp on time as the time the information reached the camp and the reaction time for evacuation was so minimum. It can be reported that warnings coming from country leadership were more effective and accepted as authentic in reducing negative effects among the respondents. This, however, depended on the time the warning was received vis-a-viz the occurrence of the flood. Warnings obtained from neighbours were not taken seriously thereby leading to a relaxed approach by the refugee community, as the District Civil Protection Unit chairperson has this to say:

As a nation, we were a complete let down to the refugee community. It is not true that the Department of Civil Protection lacks dedicated human resources. What may lack is adequate financial material resources. [interview Participant]

4.2. State of preparedness by the refugee community

There are conflicting statements on the state of preparedness of refugees as most refugee women who participated in FGDs professed ignorance regarding dissemination of early warning information prior to disaster. Those who got the information early did not take the warning seriously; hence, there was lack urgency in preparing for evacuation to safer locations. Most women complained of the lead time between the availability of the warning information and the occurrence of the flood. Thus, early warning information was poorly disseminated to the refugee communities thereby giving them limited time to respond. Although the CPU lacked resources to disseminate information on time, it blamed the Government for ill funding the department. This resulted in the poor dissemination of information to the refugee community who had limited capacity to respond. The situation was exacerbated by the absence of a national preparedness plan for evacuation. It was gathered that disaster management campaigns were not done to build refugee women’s capacity for disaster risk management. Informed decision-making is the key to ensuring disaster preparedness in the whole camp community. The research shows that women were actively involved in the evacuation exercise, including the collection of their belongings, helping the sick and the disabled to safer locations. Research findings show that some households received the warning late or ignored the warnings, hence were the most affected. As narrated by this woman from Rwanda:

We were not informed that it (the cyclone) would not affect Zimbabwe, so nobody took it seriously. It only came to reality in the night when the waters began to rise. That is when we were evacuated and gathered at Stage II, in the Settlers Community, a place where we normally gather whenever there is likelihood of floods. We were ordered to carry our belongings and go into safety. Nevertheless, the message came a bit late as the rains were already pouring. It was not long before a huge wave of water came rushing down the Save Valley that we had to run for dear life and lead our families up the high ground to safety. There was no time to collect our belongings, except a few clothes that one could carry.

Research findings show that the state of preparedness on the landfall of Cyclone Idai was extremely arduous, leaving refugee women not prepared for the disaster. The relocation of families to higher ground, to Stage II in the Small-Scale Farmers area, took long to be implemented as the message came a bit late as some children and elderly women were already soaked in the heavy floods. The host community of Maronga Village, were not spared by the floods, hence the competition for a space at Stage II.

4.3. Access to water and sanitation

The results from this research show that clean, safe water remains the most important needs for those affected by the floods. With most water sources damaged or contaminated due to Cyclone Idai, clean, safe water remained one of the most important needs for those affected, the outbreak of waterborne diseases became a major threat. Stage II, a safer location to which refugees were evacuated, had only two water points which were accessible to all refugee families. Long queues were the order of the day with men controlling the queueing process. It was not an easy task for one to get a bucket of water under such circumstances. The corrupt tendencies displayed by men controlling the queues led complaints among women, forcing UNHCR and GOAL officials to intervene. It was then decided that women should manage the queues and organize themselves in rationing the water. It was also decided that each household would get twenty litres of water per day. With women controlling the queues, there was a reduction in conflicts as they all agreed that they were facing the same crisis.

The research findings also show that there was a critical shortage of latrines at Stage II. The place had only two composite pit latrines with ten squat holes, five for men and another five for women. Women, being the majority, had to join longer queues, thus forcing them to relieve themselves in the bush. With the rains pounding and the thickets around Stage II teeming with wildlife, night escapades into the bush were risky.

4.4. The water and sanitation situation in the camp after the floods

The research findings also show that the rains fell for the whole week, during which the refugees had to stay at that place. During that time, women were cramped in temporary shelters with no access to basic WASH services, which exposed them to sexual exploitation and abuse. When they came down from Stage II, they were faced with changed circumstances, as most water points were either damaged or swept away, forcing them to rely on the stagnant water ponds dotted around the camp for drinking. They were encouraged to boil the water, but only a few who had access to firewood were able to follow such advice. Some used ash from special tree barks like Mubvee tree (Sausage tree, Kigelia Africana) to kill germs and make the water potable. Those who wanted clean water, especially from patriarchal families, had to brave the thickets of “Mayeba” into the village of Maronga, where they had to fight for the precious commodity with the host community. It was gathered that men never accompanied their spouses through those long distances but wanted to see water delivered to their homes. Lack of water in the home can contribute to tensions and sometimes violence between spouses. It was also noted that the situation tasked the older women to take care of the sick, elderly and young, even when they were ill themselves. As one Congoleese woman narrated her ordeal:

A week after the landfall of Cyclone Idai, when the rains had stopped and the floods had subsided, we went down from Stage II to be greeted by a trail of destruction left by the floods. The cyclone had destroyed our houses, schools, churches, gardens, toilets and water sources. I tried to imagine the pile of bricks and iron sheets in front of me, of what a few days before, was a beautiful house. [Interview Participant]

5. Mitigation and response

5.1. Gender equality and decision making in disaster situations

The findings from this study also revealed that women were not consulted in the design, planning and construction of the make-shift toilets in the camp. Where they were involved, it was to rubber stamp the decisions made by their male counterparts to please donor requirements. The plastic make-shift toilets that were provided were not women friendly due to lack of privacy. The toilets had no doors and did not respect the cultural diversity inherent in the camp. Thus, women felt powerless in decision-making process, increasing their frustration as well as their social and psychological vulnerabilities, which deprived them of opportunities to voice their concerns.

It was gathered that programmes that involve women at all stages of planning, implementing, and monitoring are more efficient, effective, and sustainable than those that do not prioritize equitable participation and decision-making. Most refugee women who participated in FGDs reported that they were not included in the relief aid distribution teams, leaving men with the responsibility of distributing sanitary ware, a taboo not acceptable in their culture. The participants blamed the composition of the distribution teams that mostly consisted of men only. Women were conspicuous by their absence in the distribution and security teams as they were taken to be weak and unable to carry the heavy loads involved. This did not go down well with most women who wanted to see gender equality in the teams. As this woman from Sudan had this to say:

I don’t know who came up with the decision to allow only men to distribute aid to victims of Cyclone Idai. That’s a very bad decision. We cannot have men alone to guard or in distributing aid. We want all victims to receive what they deserve without discrimination. This must be stopped. All those involved must be named and shamed.

The FGD participants also alluded to incidences of looting of aid by male distributors of NFIs meant for the victims of Cyclone Idai which they sold to the host community, which was also affected by the floods. They were also against corrupt tendencies displayed by the male refugee staff who were responsible for the distribution of the relief aid. The women viewed the massive looting for personal gain by some male refugees as contributing to the donors’ demoralization and called the camp authorities to investigate the matter so as to bring the culprits to book. As this woman from Burundi narrates:

Sometimes on run out of words to explain how evil some individuals can be. You cannot imagine one stealing food and non-food items meant for the refugees who are on the verge of starvation. This paints a very bad picture once the donors come to hear that their support did not reach the intended beneficiaries. We implore the camp authorities to urgently investigate this matter to its logical conclusion and bring the culprits to book. [Interview Participant]

It was also gathered that most refugee women did not receive their allocations of sanitary ware, towels and undergarments. This was blamed on corruption and lack of monitoring by the NGOs in the distribution of WASH assistance to the affected women that forced most donors to devise alternative ways of reaching out to the victims on their own. The decision by the donors to reach out to the needy on their own was a disgrace on the part of the NGOs. The discrepancies in the way food were handled and the delays in in reaching out to the needy, forced the donors to come up with this participatory approach which was a great relief to women because it ensured their involvement in the designing and implementation of solutions that meet their needs.

5.2. Gender based violence

Research findings from household interviews show that gender-based violence (GBV) was rampant in the camp. It was reported that the involvement of civic organizations like Msasa Project in coordinating, mapping out and strengthening the capacities of existing GBV services, was a great relief to women. The Musasa Project organization ensured that all staff and community-based structures were familiar with the referral systems and were able to refer victims of violence or rale to appropriate support service providers. For timely reporting, a register and contact details including toll free numbers were availed to the communities. The civic organizations also initiated the formation of women only clubs where women meet in women-friendly spaces. The clubs act as discussion forums where crucial issues that affect women, such as MHM are discussed. The findings also show that apart from instilling hope and a future in the lives of women, the establishment of women-led committees and the building of women-friendly spaces, have empowered women to play leading roles in the distribution of NFIs and ensure equality in accessing the materials. The platform also gave women the opportunity to assist in the promotion of good health practices to prevent diseases and conduct awareness campaigns on disaster preparedness. Although they were able to coordinate women only meetings, they were left out of WASH decision-making processes that affect their lives. The empowerment of women has caused serious divisions at family level that has led most married women being barred from attending. As one woman from Rwanda has this to say:

When gender equality is not considered in relief distribution, it is the women and children who are disadvantaged the most because they will have no one to represent them without being exposed to violence and sexual abuse. More often than not, the relief distribution exercise degenerates into physical force and violence which then disadvantages women and children. [Interview Participant]

Our research findings also reveal that arriving home late from the meetings or going back with nothing exposed women to violence by their husbands. It was gathered that risks for women increased during crises. The risks faced include infections by HIV, teenage pregnancies and child marriages. Participants in FGDs reported an increase in incidences of GBV. It was also reported that women and adolescent girls were being asked to transact sex in exchange for access to aid. Merely standing in a queue for NFIs and other support left women more vulnerable to sexual exploitation and HIV infections. Men took advantage of this vulnerability. Interviews with key informants in the camp revealed that in crisis situations one in five women of childbearing age were likely to fall pregnant. This calls for an urgent need to improve women’s access to reproductive health services. The suspension of services that provide prevention and treatment for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections during the landfall of Cyclone Idai also had a huge impact on women, as this woman from Somalia had this to say:

Women are starving and in a deplorable state. They have no food or clothes after they have been swept away by the floods. They are exposed and vulnerable to any enticement by men who had money or are in control of food distribution, they are tempted to offer themselves for sex and men can take advantage of them. [Interview Participant]

5.3. Menstrual health management

The findings of this study reveal that there was a critical shortage of menstrual hygiene management kits that could assist menstruating women after their supplies have been swept away by the floods. Most women were now resorting to the use of torn cloth, or resort to traditional ways of preserving the menstrual cycle with cow dung, baobab and banana fibre, with the shunning of bathing being the most common method adopted. This indicates the resourcefulness of women as a repository of indigenous technical knowledge. The study results also show that women and adolescent girls, traditionally tasked with care and domestic work, are often forced to take on additional responsibilities during crises. They had to queue for NFIs when humanitarian aid started to trickle in as the floods were subsiding. As one Mozambican woman gave an account of her experience:

As women we had to sleep in the queue waiting to receive “dignity kits”, which contain essential hygiene supplies, including soap, toothpaste, underwear, laundry soap, sanitary napkins and a safety whistle. However, this was marred by the corruption that is rampant in the NGOs and the refugee distribution teams. We did not receive a complete set. If one asked why, they were threatened and even the little they had received was taken back from them. [Interview Participant]

Such developments made GOAL to shift its focus in the camp to include interventions to do with the protection of women from violence, sexual exploitation, and the loss of critically needed health services, common in disaster situations. The District Civil Protection Unit (DCPU) Chairperson for Chipinge District also implored stakeholders to dedicate resources to helping women retain access to reproductive health services. Women need access to contraceptives to avoid unwanted pregnancies that leads to unsafe abortions. There is need to put the plight of women first as they are the most vulnerable during disasters. It was gathered from the FGDs that the issue of contraceptives was a non-event with some husbands as this has negative implications on food rations and cash transfers from the World Food Programme. This is a game of numbers. The more children one has, the more handouts she gets. This has resulted in unreported cases of violence and abuse due to fear of being thrown out of their matrimonial homes.

6. Discussion

The devastation caused by Cyclone Idai left an indelible mark on the lives of women who were the majority in the camp and were also the most vulnerable. Women were the most affected by the floods to the extent that they lost everything as they were slow to react than men. To this end, this discussion will give an analysis of the effects of patriarchy, corruption and gender inequality being perpetrated by men in the implementation of WASH activities on the landfall of Cyclone Idai. The study will also take a critical remark at the role of government and other stakeholders regarding their preparedness to deal with disasters, including the dissemination of early warning information.

6.1. Disaster preparedness campaigns

Disaster was imminent but the injuries and the loss of property that occurred could have been averted had the lead time between the availability of the warning information to the refugee community and the occurrence of the flood been increased. This was the case with the Tokwe-Mukosi Area, in the Masvingo Province of Zimbabwe, where successive disasters exposed the country’s lack of disaster preparedness (Mucherera, et al., 2021). Disaster Risk Reduction Campaigns would have capacitated the refugee community on what to do in a disaster situation. The CPU must have activated its lower-level operations through civil protection plans as a mechanism for disaster risk reduction. Once implemented, the disaster management programmes could increase people’s knowledge of natural hazards their characteristics. A standard training manual could be developed to serve this purpose. However, for the emergency preparedness response to be effective and sustainable, it must be driven from the local level to ensure community participation. Failure by the refugee community to get early warning information was due to the absence of a communication station in the camp that is responsible for disseminating early warnings to the community, hence the lead time between flood warning information and the flood event could not allow the victims to evacuate the and minimize property loss.

Even though they were aware that they should evacuate to safer locations, which is a higher ground, there was no feasibility study undertaken to ensure enough WASH facilities were in place before the floods. Such an analysis contradicts theories of the FPEs which recognize the complex relations between nature and society as having complex implications for the environment (Elmhirst, Citation2015). Hence, the need to put in place temporary latrines enough to meet the requirements of the displaced population, would have lessened their plight. The primary health system in the camp must be organized to respond to disaster situations to ensure safe delivery and reduce childhood diarrhoea illnesses. Thus, both the Government and humanitarian players should think beyond the relief assistance given the magnitude of destruction and loss of property experienced by the refugee community (Mhlanga et, al, 2019).

6.2. Access to WASH facilities in the camp

Water collection during emergency can be dangerous, especially for women. The distances involved to the nearest water source and the thickets they pass through expose them to sexual assault and harassment. This resonates with the findings by Amnesty International Annual Report (Citation2010) where women and girls risked harassment, sexual assault and rape when they walk to remote locations to collect water or to use WASH facilities particularly after dark. The fact that only one borehole in Maronga village survived the floods, has forced them to share with the refugees leading to conflicts. It is regrettable that the conflicts experienced are common whenever people of different socio-cultural backgrounds meet. This assertion echoes House et al. (Citation2014) who noted that queuing for water with the host community sometimes leads to disputes among water users, especially when newcomers encroach water sources that were previously accessed by the host community only. The lack of clean water sources in TRC and the host community of Maronga Village, is a cause for concern due to the fear of the outbreak of water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid. This resounds with the findings of Nyoni et al. (Citation2021) when they reported the plight of women during the Mbire Floods in 2016, where ways of preventing the outbreak of water-borne diseases were paramount in disaster mitigation.

Whenever sanitary facilities are not enough, it affects women the most. The lack of access to basic sanitary services, also exposes women to assault and rape as they look for a place to defecate. Women are often vulnerable to harassment or violence when they use shared toilets, or practice OD. They often wait until nightfall to defecate, which increases the risk of assault. This forces many to “hold it” or limit the consumption of food and drink to delay to relieve themselves, thereby increasing chances of urinary tract infection (Sommer et al., Citation2014). There is need to consult the users of the facility in choosing the design and location to ensure their safety and security, so as to enhance a sustainable WASH future in the camp. Merely availing MHM materials to women without consulting their preferred brand has led to most beneficiaries resorting to traditional methods as the diapers were causing rush. The issue of registering men as household heads, does not auger well with women who prefer individual ration cards as a way of promoting their independence.

The distribution of WASH aid must be done without discrimination on gender, ethnic or racial background as postulated by the FPE proponents like Elmhirst (Citation2011), who observed that women are sometimes excluded from decision-making processes on issues that concern their lives. However, the gender disparity inherent in the camp was the most formidable threat to sustainability. The inequity being perpetrated by the NGOs is probably due to the need for physical strength in the implementation of disaster response devices such as the construction of make-shift latrines. Such purposeful targeting is common in emergencies as there will be no time for training.

6.3. Gender equality and decision making

Women’s decision-making and choices are strongly limited by the patriarchal social norms. Thus, these gender discriminatory norms and practices must be addressed to achieve gender transformative change, which is an essential requirement for gender equity and inclusive social development. As referred to by House et al. (Citation2014), women often suffer abuse or rape while pursuing ordinary daily activities such as searching for firewood or thatch, working in their fields, fetching water from riverbeds or travelling to a market. Including women in the preparedness campaigns helps reduce stereotypes and discrimination about women’s roles. Such a scenario was experienced during the earthquake in Ecuador, in 2016, when the UN Volunteers coordinated programmes increased the involvement of women in the evacuation exercise, a traditional domain for men (www.ifrc.org). During emergency situations women tend to do more work to restore and secure household livelihoods, leaving them with less time to access training and education, develop skills or participate in the economic mainstay, which negatively impacts gender equality. Women’s continued exclusion from key decision-making positions makes it impossible to address challenges that befall them and find solutions. Thus, women bear the highest proportion of the poor that are dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods, hence linking them to the environment as purported by the FPE advocates (Sundberg, Citation2015). Although women’s involvement in decision-making about water resources and in WASH programmes is critical to their empowerment, it is important that they are not overburdened with additional unpaid work on top of their existing responsibilities.

6.4. Gender based violence

The support rendered by civic organizations like Musasa Project, who advocate disaster preparedness that integrates a gender lens, including protection of women and girls in the camp, was a welcome move. The victims need psycho-social support which is critical, but the Government took ages to provide this support. Although it is common in emergency situations for women to be assaulted or harassed, the government must take responsibility and protect its citizens. This was the case with the 2008 Cyclone in Myanmar where women were left vulnerable with little access to quality sexual and reproductive health care or psychosocial support services (West et al.,). On top of the physical and emotional trauma, the harassment and rape they are subjected to often results in social exclusion and abandonment by husbands and families. The need for water and food had taken precedence over all other issues for women forcing them to sleep in long queues, and continued to expose themselves to sexual abuse. Such scenario anchors the view held by FPEs advocates who argue that these roles are often “naturalised”, unpaid, and unrecognised (Resurrección & Sajor, Citation2015). For instance, Cyclone Aila was responsible for the suffering of women in Bangladesh due to the shortages of safe drinking water resulting from damaged or submergence of tube wells and contamination of ponds and other water bodies by saline intrusion (Khurshed & Habibur, Citation2019). Much as the NGOs are to blame for the WASH shortages in the camp leading to long queues and long distances travelled, the host government also has its fair share on this. In other words, cases of gender-based violence increased during the Cyclone period, hence the need for urgent attention on protection and prevention management. According to FPE theorists like Cole (Citation2017), many governments ignore the unequal gendered power relations brought about by the disaster, which have dire consequences on resource access for both men and women. Men often perpetrate GBV against women as a way to reinforce gender imbalances and maintain control of limited resources in these situations. Under such circumstances, women and girls face higher rates of child marriage, domestic violence, sexual violence, and human trafficking due to climate change. Such a scenario echoes the 2010 earthquake in Haiti where women and girls were trafficked due to the disaster (Kapucu & Liou, Citation2014).

6.5. Gaps and challenges in women participation

It is essential to put theory into practice when disaster strikes. For the success of the WASH project in the camp, there is need for buy-in from the women and men involved. Nevertheless, the tendency of considering communities as largely being homogeneous has resulted in most projects failing as argued by FPE advocates (Elmhirst, Citation2018). Thus, the intersectionality between gender identity that connects with other social factors such as ethnicity, caste, geo-location, education and other categorization, has a bearing on the refugee population, hence the need to respect their culture. However, there is need to monitor the “respect” as it sometimes degenerates into patriarchy that oppresses women’s voice in decision-making. The patriarchal predisposition expressed by men, where women are traditionally responsible for domestic chores, while men make decision in the home, is oppressive to women. Despite the suffering they face in the home, women show resilience and courage during the disaster, giving credit to the formation of women only clubs that instilled in them the spirit of bravery. Nevertheless, their efforts lacked support from the male leadership who viewed such acts as having potential to catapult them to power. Thus, patriarchy and anarchy, on the part of men, has delt a blow on gender equality in the implementation of WASH projects. This was the case with the Tokwe-Mukosi disaster of 2016 where power sharing and the inclusion of women in leadership to ensure accountability and transparency in the distribution of resources, remained an unsolved issue as men dominated the power structures in the camp (Mucherera et al., 2021). There is also the assumption that having women in the leadership structures will lead to the success of all projects, a phenomenon perpetrating division in the home. Men also resent the sharing of responsibilities within the household, including caring responsibilities, as they take it to be traditionally a women’s task in the home. The rise in social challenges being experienced in the camp, resulting in child marriages, is common in a crisis of this magnitude, as way of bailing them out of poverty. The need to construct lockable toilets that are women friendly to ensure privacy, with MHM facilities, promoting women protection while reducing potential incidences of GBV, is a splendid idea. The make-shift plastic toilets failed to meet this purpose, since make-shift toilets exposed women to various forms of violence. The devastation caused by Cyclone Idai disaster affected women more than men, resulting in psychological trauma, calls for the introduction of psychosocial support programmes to restore hope and build their self-esteem in them. This calls for the creation of safe havens for women to get advice on where to report and obtain legal support, a phenomenon resonates with the FPE advocates who propound that suffering and embarrassment in addition to difficulties in accessing water (Collins, Citation2015), were the major causes of stress, hence the need for such a platform.

6.6. Lessons learnt

The Cyclone Idai disaster taught us that unity of purpose can transform the lives of many. The TRC community was traumatized by the impact of the cyclone. Building the resilience of women is not a choice but an obligation. The Zimbabwe government took very little action to prepare for the oncoming tropical cyclone and its likely impact. This was also the case with the 2016 Muzarabani and the 2014 Tokwe-Mukosi disasters, where the incapacity of the government to respond to disasters was exposed (Mucherera, et al., Citation2021). Despite being affiliates and members of the International frameworks, such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2020 (SFDRR) that address relocations of communities in disaster-prone areas (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Citation2015), the country’s disaster mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery system was financially crippled hence the need for massive budgetary support (Nhamo & Chikodzi, Citation2021b). Given that the department has to run early warning systems, conduct vulnerability updates, civic education, keep active provincial and district teams and purchase key equipment including vehicles to effectively conduct its work, it is no wonder that

While various players came on board to assist the refugees during the disaster, it is important to point out that there is need for comprehensive and sustainable social protection interventions to be put in place. The fragmented approach to flood management, with a highly centralized decision-making approach to flood management, and the lack of local community involvement in the decision-making processes must be improved upon. For accountability purposes and effective monitoring, it is proposed that the CPU must have gone to TRC after the warning by the meteorological department to ensure compliance by the refugee community to the early warning information, in compliance with the Sendai framework of Action (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Citation2015). There are doubts that awareness programmes in response to disasters were not conducted in the camp, hence the impact of the disaster. However, lack of guidelines in setting the early warning training was noted as the major compounding factor.

7. Conclusion and recommendations

Cyclone Idai was one of the worst natural disasters experienced in Zimbabwe in recent years. While events of this nature cannot be prevented from occurring, there is need to ensure the prevention of the traumatic experiences that affect women and girls as a result of these events. The study therefore concludes that gender inequality in disaster situations, impacts on women and girls the most, as men tend to have more decision-making powers and control over resources than women, hence the need for a gender sensitive disaster risk management plan.

The study therefore recommends the following interventions as a way of improving the lives of women in the camp in the event of future disasters:

That the CPU in Zimbabwe as the country`s emergency management agency be capacitated to take core operational capabilities and innovations, like drone mapping essential in flood response by enabling rapid assessment and targeting of affected areas.

That the capacity of women to respond to floods or disasters be enhanced through the development of community management plans to promote the dissemination of early warning information as this is essential in alleviating disaster.

That clear procedures for reporting cases of GBV and measures to protect victims from retaliation be set-up in the camp to ensure a gender responsive approach to disasters.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wisdom Sibanda

Wisdom Sibanda is a PhD student in the Department of Geography at the University of the Free State and a humanitarian worker with a number of national and international organizations. His research interests include Political Theory, Development Studies, Environmental Politics, Sustainability, Society and Environment, Human Geography and Migration, Environmental Policy and Planning, Environmental Governance, Gender and the Environment, Water Sanitation and Hygiene, Water Resources Management, Social Theory, Environmental Management, Climate Change and Adaptation, Disaster Risk Reduction, Environmental Impact Assessment, Public Policy and Management, Monitoring and Evaluation and Results Based Management. He has experience in community development that includes conducting participatory research, baseline surveys, participatory monitoring and evaluation and participatory reporting through the use of participatory approaches.

References

- Adams, E. A., Sambu, D., & Smiley, S. L. (2018). Urban water supply in Sub-Saharan Africa: Historical and emerging policies and institutional arrangements. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.8007/900627.2017.1423282

- Alam, K., & Rahman, H. (2014). Women in natural disasters: A case study from Southern Coastal Region of Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 8, 68–82. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.01.003

- Amnesty International Annual Report. (2010). https://www.voanews.com/a/amnesty-international.

- Association, S. (2018). The sphere handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum standards in Humanitarian Response, fourth edition, Geneva, Switzerland (p.86). https://www.spherestandards.org/handbook

- Bradshaw, S., & Fordham, M. (2013). Women, girls and disasters- A review for DFID.GSDRC, Applied Knowledge Services. DFID. www.dfid.gov.uk/

- Calderón‑Villarreal, A., Schweitzer, R., & Kayser, G. (2022). Social and geographic inequalities in water, sanitation and hygiene access in 21 refugee camps and settlements in Bangladesh, Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and Zimbabwe. International journal for equity in health, Vol. 21, 27. Spinger Nature. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939‑022‑01626‑3

- Charmaz K, Belgrave L. (2012). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Qualitative

- Chatiza, K. (2019). Cyclone Idai in Zimbabwe: An analysis of policy implications for post-disaster institutional development to strengthen disaster risk management. Oxfam.

- Chitongo, L., Tagarirofa, J., Chazovachii, B., & Marango, T. (2019). Gendered impacts of climate change in Africa: The case of cyclone idai, chimanimani, Zimbabwe; the fountain. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 3(1). https://semanticscholar.org/paper/Gendered-impacts-of-climate-change-in-Africa

- Cole, S. (2017). Water worries: An intersectional feminist political ecology of tourism and water in Labuan Bajo, Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research, 67, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.07.018

- Cole, J. R., Holl, K. D., Zahawi, R. A., Wickey, P., & Townsend, R. A. (2016). Leaf litter arthropod responses to tropical forest restoration Ecology and Evolution, John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305489700

- Collins, H. P. (2015). Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

- Elmhirst, R. Introducing new feminist political ecologies. (2011). Geoforum, 42(2), 129–132. special issue. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.006

- Elmhirst, R. (2015). Feminist political ecology; the routledge handbook of political ecology_London UK: Routledge. 519–530. Chapter in Book/Conference proceeding with https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315759289.ch40.

- Elmhirst, R. (2018). Feminist Political Ecologies – Situated Perspectives. Emerging Engagements, No. 54. special issue on ecofeminism. http://www.ecologiapolitica.info/?cat=263.

- Flynn, B. W, & Sherman, R. (2017). Integrating emergency management and disaster behavioral health, one picture through two lenses, butterworth-heinemann, elsevier. Elsevier.

- Gwimbi, P. (2007). The effectiveness of early warning systems for the reduction of flood disasters: some experiences from cyclone induced floods in Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa. 9. 4. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/

- Hanson, A., & Buechler, S. (2015). Towards a Feminist Political Ecology of women, global change and vulnerable waterspaces. In Book: A Political Ecology of Women, Water and Global Environmental Change. Routledge.

- Haque, M. A., Rahman, D., & Rahman, M. H. (2016). The importance of community-based approach to reduce sea level rise vulnerability and enhance resilience capacity in the coastal areas of Bangladesh: A review. J Sustain Sci Manage, 11(2), 81–100.

- H, H. A., B, N. P., Pilaseng, K., Paw, M. K., Darakamon, M. C., Min, A. M., Charunwatthana, P., Nosten, F., McGready, R., & Carrara, V. I. (2019). Feeding practices and risk factors for chronic infant undernutrition among refugees and migrants along the Thailand-Myanmar border: A mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1586. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7825-7

- Hemachandra, K., Haigh, R., & Amaratunga, D. (2021). Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk science direct, elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818750-0.00004-0

- House, S., Ferron, S., Sommer, M., & Cavill, S. (2014). Violence, Gender and WASH: practitioner toolkit - making water, sanitation and hygiene safer through improved programming and services WaterAid/SHAREInterInterAgency Standing Committee, 2015. Emergency Preparedness Response, Risk Analysis and Monitoring Minimum Preparedness Advanced Preparedness and Contingency Planning

- Inter Sector Coordination Group. (2020). Situation report rohingya refugee crisis cox’s bazar https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/www.humanitarianresponse.sites/files/documents/final_iscg_sitrep_april_2020.pdf.

- Jannatul, F., & Dwijen, M. (2019). Norms, practices, and gendered vulnerabilities in the lower Teesta basin, Bangladesh. In Environmental Development (Vol. 31), pp. 88–96. ScienceDirect; Elsevier.

- Kapucu, N., & Liou, T. K. (2014). Disaster and development: examining global issues and cases. In Springer International Publishing. Springer LondonLtd (pp.469). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04468-21

- Khurshed, A., & Habibur, R. (2019). Post‑disaster recovery in the cyclone Aila affected coastline of Bangladesh: Women’s role, challenges and opportunities Natural Hazard. Springer Nature BV. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03591-7

- Miletto, M., Pangare, V., & Thuy, L. (2019). Tool 1 – Gender-responsive indicators for water assessment, monitoring and reporting. UNESCO WWAP Toolkit on Sex-disaggregated Water Data. UNESCO.

- Mollett, S., & Kepe, T. (2018). Land rights, biodiversity conservation and justice. rethinking parks and people. In Routledge studies in sustainable development (pp. 220). Routledge.

- Mucherera, B & Spiegel, S. (2021). ‘Forced displacement: Critical lessons in the protracted aftermath of a flood disaster’, GeoJournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/510708-021-10471-w

- Mukanganise, R. (2011). Disaster Preparedness at Community Level in Zimbabwe: The case of Chirumhanzu and Mbire; Dissertation thesis for masters degree in development studies, Women University in Africa. Scientific Research.

- Mulyasari, F., & Shaw, R. (2013). Role of women as risk communicators to enhance disaster resilience of Bandung, Indonesia. Nat Hazards, 69(3), 2137–2160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0798-4

- Mushanyuri, B. E., & Ngcamu, B. S. (2020). The effectiveness of humanitarian supply chain management in Zimbabwe. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 14. a505. https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v14i0.50

- Ngarava, S., Zhou, L., Mushunje, A., & Chaminuka, P. (2021). Vulnerability of settlements to floods in South Africa: A focus on port St Johns. In G. Nhamo & L. Chapungu (Eds.), The increasing risk of floods and tornadoes in Southern Africa. sustainable development goals series (pp. 203-219). Springer: London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74192-1_12

- Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2021a). The catastrophic impact of tropical cyclone Idai in Southern Africa. Cyclones in Southern Africa. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72393-4_1

- Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2021b). Floods in the midst of drought: impact of tropical cyclone idai on water security in south-Eastern Zimbabwe. In Cyclones in Southern Africa. sustainable development goals series (pp. 119-132). Springer. Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72393-4_7

- Nyoni, J., Gwatirisa, C., Nyanzira, Y. N., Dandira, M., & Kandjinga, E. (2021, April). The plight of women during and after floods. A case study of the mbire district, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation (IJRSI), VIII(4).

- Olivius, E. (2014). Governing Refugees through Gender Equality Care, Control, Emancipation, PhD Thesis, Department of Political Science & Umeå Centre for Gender Studies, Graduate School for Gender Studies, Umea University.

- Rajib Shaw, R., Shiwaku, K., & Izumi, T. (2018). Science and technology in disaster risk reduction in asia, potentials and challenges, science direct, elsevier. Academic Press: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2016-0-01555-3

- Responding to COVID-19: UNICEF Annual Report 2020. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), (2020).

- Resurrección, B. P., & Sajor, E. E. (2015). Gender, floods and mobile subjects: a post disaster view. In R. Lund, P. Doneys, & B. P. Resurrección (Eds.), Gendered entanglements: revisiting gender in rapidly changing Asia (pp. 207–234). Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

- Rocheleau, D., Slyster, T. B. & Wangari, E. (1996). Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experiences. London and New York: Routledge

- Sang, D. (2018). One year on: time to put women and girls at the heart of Rohingya response. In Oxfam briefing paper. Oxfam International. Oxfam GB, Oxfam House.

- Shroeder, A. (2019). Rethinking disaster preparedness in southern Africa after cyclone Idai, direct relief. Reliefweb international.

- Sommer, M., Ferron, S., Cavill, S., & House, S. (2014). Violence, gender and WASH: Spurring action on a complex, under documented and sensitive topic. Environment and Urbanization, 27(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247814564528 www.sagepublications.com

- Spiegel, S., & Mhlanga, J. Refugee policy amidst global shocks: encampment, resettlement barriers and the search for ‘durable solutions. (2022). Global Policy, 13(4), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13084

- Stikova, E. (2016). Disaster Preparedness. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health, 2016, 5–106. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/SEEJPH-2015-106

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd) ed.). Sage Publications.

- Sundberg, J. (2015). Feminist Political Ecology: The International Encyclopedia of Geography. Wiley-Blackwell & Association of American Geographers.

- Tongco, M. D. C. (2007). Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobotany Research & Applications, 5, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.17348/era.5.0.147-158

- UNEP. (2016). Global gender and environment outlook. In UN Environment, Nairobi, Kenya.

- UNHCR. (2017). Hygiene promotion guidelines. UNHCR. https://wash.unhcr.org/download/hygiene-promotion-guidelines-unhcr-2017

- UNHCR. (2021). UNHCR Zimbabwe fact sheet, september 2021.

- UNHCR & WFP., (2014). Joint assessment mission report: tongogara refugee camp

- United Nations Environment Annual Report. (2019). https://news.unep.org/annual report 2019/index.hph

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. (2009). International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction, (7817). https://www.preventionweb.net/files/7817-UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf?.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2015). Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030, UNDRR. https://www.preventionweb.net/sendai-framework/sendai-framewrk-for-disaster-risk-reduction

- WHO/UNICEF. (2020). State of the world’s sanitation: an urgent call to transform sanitation for better health, environments, economies and societies. new york: united nations children’s fund (UNICEF) and the world health organization, published by UNICEF and WHO Programme Division/WASH 3 United Nations Plaza New York, NY 10017 USA www.unicef.org/wash

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. (2010). Progress on sanitation and drinking-water: 2010 update. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44272

- World Health Organization. (2015). World health statistics 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/170250

- Zambuko, CA. (2011). “Climate Issues and Facts”. Zimbabwe Meteorological Services Department