?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study looked at how government policies and financial security affect the use of mobile money services. A mixed method was used, with a focus group and survey questionnaires administered. Data was collected from 2041 mobile money users were collected and analyzed using SmartPLS based on the TAM model. Government policy and financial security have impacted users’ decisions to adopt mobile money services in Ghana. Perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness, have influenced users’ attitudes to adopt mobile money. Again, behavioural intention to use mobile money is directly influenced by user’s attitude. Also, TAM theory has shown to be robust in analyzing affective, cognitive and behavioural issues. The findings will encourage the Ghanaian government, through its agencies, to continue with policies to improve mobile money services. This also demonstrates that citizens will support government policy related to mobile money as long as it is intended to improve the industry. Finally, mobile money services allow the development of the Ghanaian economy’s formal and informal sectors.

1. Introduction

The government policy on financial inclusion has been received with many misconceptions (Patwardhan, Citation2018; Qureshi et al., Citation2021). The policy by the government included mobile interoperable and interconnectivity among all financial institutions in Ghana, the financial inclusion act and the money laundering act. These policies may generally positively or negatively impact users’ decision to the mobile money ecology growth (Qureshi et al., Citation2021; Younas & Kalimuthu, Citation2021). However, there are not many avenues to access the impact of such policies on the very industry it is set to regulate. The policy transfer study focuses on the relationship between transfer and policy outcomes. In general, policy transfer is thought to improve the efficiency of government processes (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Radaelli, Citation2005). According to Patnam et al., Citation2020) government policy influenced the growth and acceptance of mobile payment, as was the case in India. In addition, Scherer, Citation1980) posited that government policy greatly affected several other aspects of market dynamics in mobile payment. In light of that, governments continue to see the benefits of fostering mobile commerce that may need the implementation of legislative action unique to digital payments in the country of implementation (Kemal, Citation2019).

The level of government support to the telecoms in terms of policy and infrastructure support has an impact on the level of acceptance of mobile money (Katusiime, Citation2021; Bowers et al., Citation2017). The government’s role in monetizing financial flow is essential, resulting in the regulations, which were considered in the study to understand its impact on the users’ decision to adopt financial transactions (Qureshi et al., Citation2021; Bowers et al., Bowers et al., Citation2017). This included enhancing the security settings in the mobile money banking ecology, and how many security measures are to be implemented in the mobile money system.

The study’s structure restrained the following, the purpose of the study, and the literature considered the technology acceptance model (TAM) for the study. The study’s conceptual framework deconstructs the TAM construct, which includes government policy, financial security control, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, user attitude, and behavioural intentions. To understand the study approach, the methodology is discussed, as well as the sample size to determine for selection of the study population. The study outcome analysis is used to determine the dependability and validity of data analysis for the study outcome. The study’s final step discusses the study’s results, findings, and conclusions for the study.

1.1. Purpose of the study

The study’s purpose is to determine the impact of government policy and financial security control on the mobile money industry.

1.2. Research question

The following study questions were set to unveil the outcome of the study question.

What impact does government policy have mobile money industry using TAM?

What role does financial security policy impact mobile money services?

2. Literature review

Mobile wallets are among the most recent developments, having the ability to significantly alter how customers place orders and improve overall shopping experiences (Mew & Millan, Citation2021). The use of mobile telephones as a proximity technology for the initiation of payments via connected payment accounts is an established method between an operator and a user. Mobile money is user-friendly, safe, accessible, and reliable, users prefer to use them for all of their financial transactions such as fund transfers and bill payments (Singh et al., Citation2020) Payments are permitted following confirmation of the user’s personal identification number(PIN) and the amount requested is deducted straight from the user’s mobile money account (Acker & Murthy, Citation2018).

Mobile money services are integrated into the banking tools of the user, this is linked to a traditional bank or a third-party provider to customers (Hillman & Neustaedter, Citation2017). This service is simple and does not require an Internet connection between end-users since it is hosted through the USSD application. It also depends on the code incorporated in the shortcode, with the set of menus to be selected from, which is hosted with the asterisks (*) and ends with a hashtag (#). The USSD services application is considered more security inclined than the SMS services (Lakshmi et al., Citation2017). Some companies use mobile wallets that only enable their consumers to pay at their shops and now churches, schools, restaurants, coffee shops and parking facilities employ these services.

Similarly, financial and non-financial payment operators, including merchants and mobile network operators, adapt this system service practice under the guideline “Know your consumer”, which is the procedure whereby banks or other financial firms get details about their clients’ identities and addresses (Reyes-Mercado, Karthik & Mishra, Citation2020). Different scholars have looked at and analysed related elements that impact mobile money adaptation in general (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Khan et al., Citation2017; Malaquias et al., Citation2018; Merhi et al., Citation2019). It shows that among adoption of mobile money services by consumers is influenced by several factors, which include improving human development (Khan et al., Citation2017) and changing and transforming society (Merhi et al., Citation2019).

The literature shows the knowledge gaps in mobile money banking in either developed or developing countries. From the research work of Doris & Caroline, Citation2017) on “mobile money use in Ghana”, focusing on rural areas’ financial inclusion, the study considered only one rural bank (Access bank) in one region out of ten regions then in Ghana. The research concluded that, after a cursory look at the performance and activity of the mobile banking system in general, there have several factors suggested to be pushing and thriving this emerging banking and money business (Kingiri & Fu, Citation2019; Priya et al., Citation2018). Therefore, there is the need to carefully look at and re-examine some of these factors and, most importantly, investigate their sustainability and growth, specifically in developing countries.

The mobile money transfer expansion systems, powered through technological developments, bolstered by different consumer behaviour and financial enclosure, help customers while providing new challenges for regulatory institutions (Merhi et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2020). The swift expansion of the mobile technology revolution and the rise of online transactions are clear indicators that mobile devices seem to have grown in importance as a component of the internet landscape (Chigada & Hirschfelder, Citation2017; Payne et al., Citation2018; Priya et al., Citation2018). The widespread reliance on mobile gadgets already had a favourable acceptance of digital payment apps (Luna et al., Citation2019; Cao et al., 2018). The wide range of cellphones signifies a positive outlook for electronic marketing (Luna et al., Citation2019).

The use of mobile money has become very important in bridging the most critical services in times of crises, disasters, or pandemics like Covid-19 (Beaunoyer et al., Citation2020; Bryant et al., Citation2020). There was a surge in cyberspace and fraudulent attacks (Renaud et al., Citation2020), where individuals or groups of people took advantage of volumes of financial transactions online during the pandemic to attack and defraud users. That also disrupted users’ trust in the use of mobile money services (Mingis, Citation2020). The government was then edged on to put measures to strengthen the industries and its operation which are vulnerable to such attacks. This then calls for other perspectives on the control of measures leading to the adoption of mobile money and how such a perspective could be strengthened to help the healthy growth of the industry. From that, the study looks at the role of government as a stakeholder in the mobile money industry and the financial security control impact on mobile money services.

Government policy also influences the cost of charges to be adopted by the operators in the mobile money industries. Government policies including security services, interoperability and connectivity system, reduction of tariffs and fair competition have aided the course of mobile money operations. These policies by the government do not automatically translate into cost reduction for service providers; however, it enhances the operational cost determined by the service providers to their clients (Abooleet et al., Citation2018; Kanobe et al., Citation2017; Lin et al., Citation2020; Priya et al., Citation2018; Qureshi et al., Citation2021; Younas & Kalimuthu, Citation2021).

The need for financial security control features in the current mobile money banking system is not out of place. Security had emerged as a major concern in the mobile money banking industry, and Ghana is no exception to that narrative (BACE Group, Citation2019; Kanobe et al., Citation2019; Kelly & Palaniappan, Citation2019). Although, consumers usually respond by indicating that they'd be willing to use the mobile banking system. However, they acknowledge that they are extremely concerned about the adverse financial security reports attributed to mobile money services. (KPMG, Citation2018). The most relevant security recommendation that comes with mobile money banking is mostly related to users taking extra precautions on their devices. Moreover, there are other security measures when introduced that will strengthen mobile money this include, including two-factor authentication (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2019; Kanobe et al., Citation2019). In the area of mobile money security, the study organised a focus group discussion, that revealed the following security challenges related to the mobile money system in Ghana;

there is much room for agents to trade-off the customers’ data to a third party (Pooja et al., Citation2021) without the knowledge of operators even though there are strict regulations set by the government on that (BOG, Citation2015).

The exploitation of users registering without any form of personal identification.

There is little security separation of control in the mobile money among telecoms administrators who are also users of mobile money services (Kanobe et al., Citation2019).

Regulations on mobile money are not enough since most of the guidelines have been violated (BOG, Citation2015) giving room to some security challenges.

Also, there are other dimensions in terms of technology that have been made in the area of mobile money banking. According to (Hampshire, Citation2016), the fundamental outcome and principle that edge people to use technology from the perspective of the Technology Acceptable Model, such as “age, gender, and educational qualification with characterised perceived ease of use”, under the TAM are not necessarily important, as the consumer sees such as evident and not crucial influence in the use of technology as in the case of a developed economy. This is expressed differently, as may be the case in Nigeria as a developing economy (Abayomi et al., Citation2019). Mobile banking is a valuable supplement for users in developed economies as a means of managing their financial services and transaction, apart from Internet banking and ATM services (Markoska & Ivanochko, Citation2018). As a result, when individuals contemplate embracing mobile money, characteristics like convenience and simplicity of use become essential criteria. However, according to (Kingiri & Fu, Citation2019) and (Priya et al., Citation2018) in an emerging economy, the attractiveness of mobile money services has more to do with availability and affordability owing to internet connectivity, quality connections, and pricing rather than convenience.

According to (Gautam et al., Citation2020) research perspective, to investigate the factors of mobile money banking adoption, they used the theoretical perspective, the TAM theory. Their study assessed and experimentally analysed the crucial characteristics that influence consumers’ behavioural intention to use mobile wallet services. According to the study, it was evidently clear that all the constructs used in TAM are useful for users’ perception of adoption. Even in the use of an integration of models such as TPB, TAM and Diffusion of innovation (DOI), to determine users’ adoption of mobile banking, the study of (Alam et al., Citation2018) and (David-West et al., Citation2021) indicate that most of the construct in the model support user’s acceptance of mobile banking service.

2.1. Technology acceptance model (TAM)

The study adopted a theoretical framework of the technology acceptance model (TAM). There is sufficient studies on the need for technology to determine users’ adoption of technology-oriented products or services (Alam et al., Citation2018; Gautam et al., Citation2020; Suhartanto et al., Citation2019). Other technology innovation theory models were also used to elaborate technology adoption. For instance, the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is mostly used by an organisation when introducing new technology products. TPB gives an explicit outcome on the service the organisation is projecting (Alam et al., Citation2018).

The theory of reasoned action (TRA) is mostly used to view that the individual has extraordinary control in the final decision in the choice of technology adoption. TAM is constructed to influence the technology used or adoption through other indirectly mediating factors. Also, TAM is more convenient to use than other modelling techniques, such as the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), and it delivers a fast and affordable means of obtaining general information about a person’s perception of technology. The goal of the UTAUT is to demonstrate user intentions to use an information system as well as succeeding usage behaviour. Each of these models has received some level of criticism, so the choice of application is determined by the study’s goals. The question of why technology is accepted in association with a product and service has long been discussed, and it is very critical for the organisation and business growth (Tidd & Bessant, Citation2020). The question most studies sought to do, which is not different from this study, is to determine the veracity, reliability, and consistency of the technology adopted within the scope of that study. The theoretical model used mostly depends on the philosophical axiom proposed from the motivation and the study’s objectives. Given that, the philosophical axiom for this study is to determine the contribution of government policy and financial security to Ghana’s mobile money services.

Davis, (Citation1989) postulated that TAM is an altered version of the TRA, which was also presented by (Fishbein et al., Citation1980). (Davis, Citation1989) concept aimed to shed further light on the issue of human behaviour, such as people’s choices of technology. “Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use,” “attitude toward using,” and “behavioural intention to use” as it’s in more recent studies related to adoption (Alam et al., Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Gautam et al., Citation2020; Malaquias et al., Citation2018; Singh et al., Citation2020). Human behavioural motives to use a specific technology, according to TAM theory, in other instances, behavioural intentions dictate the actual use of technology (Davis, Citation1989). The TAM is widely used in the fields of Information Science and Information Technology. However, in addition to the “perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness” attributed to TAM with several other structures, it’s been extended with such endogenous variables, namely, social influence and cognitive. Featherman & Pavlou, (Citation2003), using TAM theory extended theory with trust and risk variables. The concept of extending TAM theory has greatly assisted many studies in moving forward with this model by utilizing trust and risk mostly in the study of technology adoption in a variety of disciplines of study (Hampshire, Citation2016; Lin et al., Citation2020; Singh et al., Citation2020).

It is in line with this that, the study introduced government policy and financial security control to determine its impact on behavioural intention to use and actual use of mobile money services. More so to the point where Ghanaians are resisting government policy to implement the electronic transfer levy Act, 2022 (E-levy) in the country. Little or none of such studies have been undertaken in that perspective (Berry & Berry, Citation2018; Katusiime, Citation2021).

3. Conceptual frameworks

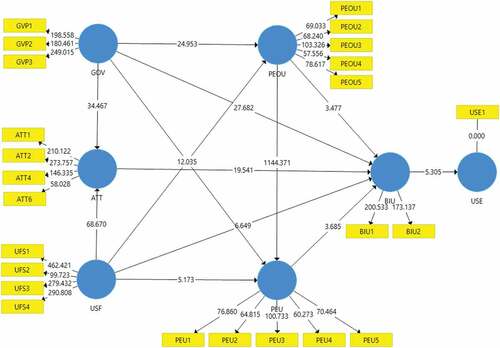

The study conceptual framework used is based on TAM, with government policy and financial security construct introduced. Government policy such as laws and regulations (the Payment Systems Act 2003; Bank of Ghana Agent Guidelines, 2014; Financial Institutions regulated under Banking Act, 2004; Bank of Ghana Act 612; Bank of Ghana Act 918; Banks and Specialised Deposit-Taking Institutions Act 930; Non-Bank Financial Institutions Act 774; Companies Act 179; Electronic transfer levy Act, 2022 (E-levy) discussed its impact on mobile money banking and services. Furthermore, the financial security construct discussed the security measures to include in the current mobile money application (two-factor authentication; use of alphanumeric PIN and increasing the PIN length to six characters) to curb the threat of theft in the mobile money ecosystem. Figure shows the study constructs and mapped links associated with both exogenous and endogenous factors, each construct and its related association to the study is discussed in detail.

3.1. The attitude of users’ impact on their behavioural intention

Attitude is a positive or negative assessment of situations, people or objects which influences what they believe or how they behave (Ajzen, Citation1989). According to McLeod (Citation2009) attitudes consist of psychological components which are linked together to form individuals’ attitudes, and which control their behaviour towards a subject. According to (Ajzen, Citation1989) attitude could be described in three folds: affective, behavioural and cognitive. Affective components consider people’s feelings or emotions towards a subject, while behavioural components consider the way that attitudes impact how people act towards a subject. As for the cognitive component, this involves people’s beliefs. Attitude determines one predictive intention use a particular technology cannot be left out in most studies in the areas of information science, e-commerce and many other studies relating to one intended to use technology, user attitude has become a pivotal variable in most such studies (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Kelly & Palaniappan, Citation2019; Sigurdsson et al., Citation2018). Once a user has a positive attitude toward technology or its related services, there is a greater chance to use that particular technology in question (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Huei et al., Citation2018; Sigurdsson et al., Citation2018). From that, the study proposition is posed.

Proposition 01: Users’ attitudes toward mobile money banking affect their behavioural intention.

3.2. The behavioural intentions of users influence their actual use

Adoption of technology can be referred to as acceptance and one’s willingness and desire to incorporate that technology into their present task either in the long or short-term depending on the challenges the user may want to mitigate. In Davis’s theory of TAM (Davis, Citation1989), one’s attitude has shown to take a greater influence on their behavioural intention to use a particular service or technology (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Huei et al., Citation2018).

Luna et al., (Citation2019) described technology, and thus its qualities, as a detailed concept of technology acceptance in a setting that means activities related to technology might inspire intents and interest in using the technology, which could also impact actual behaviour to adoption. Lin et al., (Citation2020) posited that a person’s attitude impacts one’s behaviour, which is asserted by an individual’s desire to engage in a certain manner. Other factors influence one’s behaviour in making a decision based on choice; critical of such factors is attitude. Invariably, attitude is influenced by other factors such as perceived cost and perceived usefulness. It is not out of place that these factors also influence behavioural intentions. Attitude is objective in determining users’ predictive intention to use a particular technology and service cannot be left out in most studies, which include information technology, information science, e-commerce, and many other studies relating to one’s positive intention to use technology. User attitude has become a fundamental factor in the adoption of services and technology (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Huei et al., Citation2018; Islami et al., Citation2021; Sigurdsson et al., Citation2018).

Tiong, (Citation2020) indicated that an individual’s behaviour is influenced by an intention to act on that perceived behaviour, this is also supported by other studies (Abooleet et al., Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Huei et al., Citation2018) where users perception about a subject have influenced their decision making. The performance of the behaviour is heralded by a person’s behavioural intention to participate, subject to one’s behaviour (Abooleet et al., Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Huei et al., Citation2018). It is much the case that one’s behavioural intentions will positively influence their attitude to the actual usage of technology or service. Behavioural intention is the resultant effect of all the determinants for the TAM. The effect of the studied variable determined how users were influencedi to use mobile money banking.

Proposition 02: The behavioural intentions influence users’ actual use of mobile money services.

3.3. Government policies have an impact on individual behavioural intentions

Most governments introduce policies and laws to govern every facet of their citizens’ social life, which include the operation of mobile money banking industries (Katusiime, Citation2021). The outcomes of such policies and laws in the mobile money service tend to have an overarching influence on the user’s adoption of mobile money (David-West et al., Citation2021; Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Katusiime, Citation2021; Radaelli, Citation2005). Government policy is to bring sanity and protect customers, and industry players. Such policies must be fine-tuned to ensure a good balance and not disrupt the mobile money banking ecology (Katusiime, Citation2021; Radaelli, Citation2005).

Determining how government policy and financial security control influence users’ adoption of mobile money banking systems in Ghana has become vital in the face of citizen resistance to e-levy. The issues with government policy and the adoption of technology are mostly not a straight line. However, it is the overflow effect of such laws that is mostly noticed. The laws on mobile money by the Government of Ghana are several folds. The law and regulations set for both banks and non-banking financial institutions operating include mobile money and mobile banking services.

The Central Bank of Ghana, which regulates the establishment and implementation of all banking activities, is also tasked with ensuring the safety of customers’ deposits, compliance with legal and regulatory standards, and the operation of an efficient mobile payment system. Previous studies show that such policies and laws have influenced the acceptance of mobile money and banking services in other jurisdictions (Kingiri & Fu, Citation2019; Martin, Citation2019). Other studies have revealed the challenges related to government policy with mobile money and mobile banking services, where government policy has impacted the SIM registration irregularities affecting the adoption of such technology related to mobile banking services (Kemal, Citation2019; Malinga & Maiga, Citation2020). Government policy has influenced users’ acceptance of mobile banking, this is much related to this current study as shown in other studies (Kanobe et al., Citation2017; Katusiime, Citation2021; Kingiri & Fu, Citation2019; Priya et al., Citation2018). The understanding of the government policy implementation and its impact has led to formulating the following study proposition.

Proposition 03: Government policy has an influence on users’ Attitudes toward mobile money service

Proposition 04: There is a significant impact of Government policy on users’ Behavioural Intention

Proposition 05: There is a significant impact of Government policy on perceived ease of use

Proposition 06: There is a significant impact of government policy on the Perceived usefulness

3.3.1. The perceived ease of use impact attitude of use

Perceived ease of use is one most determinant factors in defining the acceptance or the rejection of a technology, according to Davis, (Citation1989). There have been other studies that concluded with the same outcome (Islami et al., Citation2021; Raza et al., Citation2017; Sugandini et al., Citation2018). Technology or new system are developed with the concept of it being accepted. Every technology is set to achieve this target but it is certainly not automatic in most cases.

This then becomes a subject that has to be studied in the course of every technology or system to ascertain whether this perception is targeted. Given that, perceived ease of use has enabled technology concepts and development to be purposeful and relevant. This factor is not different from the case of Ghana, even with a little over 40 percent educated population, having 32 million mobile money banking users. It is clear from the study of Hampshire, Citation2016) on smartphone mobile banking use in the UK that education and age do not influence the use of the mobile phone in the case of his study area and subject. From that, the following proposition was made for the study.

Proposition 07: There is a significant impact of Perceived ease of use on behavioural intention.

Proposition 08: Perceived ease of use has influence on user Perceived usefulness.

3.4. The perceived usefulness impact on a user’s attitude

In TAM, perceived usefulness shows how the technology or system used could aid a user’s performance in achieving a positive job outcome as much as necessary (Moslehpour et al., Citation2018; Raza et al., Citation2017; Sugandini et al., Citation2018). There is a strong determination that, the perceived usefulness of technology on the part of the user will influence their interest to use the service and technology provided (Moslehpour et al., Citation2018; Singh et al., Citation2020). It is equally true that perceived usefulness has an impact on the user’s attitude in the kind of decision they arrived at in the adoption of technology (Islami et al., Citation2021; Malaquias et al., Citation2018; Raza et al., Citation2017; Sugandini et al., Citation2018). Countless matters interest a user in the choice of technology; and one of such is the timely service rendered in response to service needed, which mobile money banking service is given to their users. It is also as a matter of fact that it is not in all instances that perceived usefulness has had a positive impact on user attitude when the factor of risk of the technology is in doubt; it could dissuade the user to accept or reject that technology (Davis, Citation1989; Islami et al., Citation2021; Malaquias et al., Citation2018; Rehman et al., Citation2019).

Prior studies show that perceived usefulness has a significant effect on usage intention, either directly or indirectly through its effect on users’ attitudes (Davis, Citation1989; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). A system perceived to be easier to use will facilitate more system use and is more likely to be accepted by users (Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). In the context of mobile money, users may find mobile money services uneasy when the system is not easy to learn and easy to use. Information such as details of products or services, their benefits, and usage guidelines needs to be provided as it will make it easier for consumers to adopt mobile money. Furthermore, the perceived usefulness helps in building trust with banks as it may send a signal that banks have really thought about their end users (Lin et al., Citation2020). In light of this, the proposition that emerges is whether the perceived usefulness of mobile money banking services impacts a user’s willingness on using mobile payment services and which also turns to influence the actual use of mobile money services.

Proposition 09: Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on users’ behavioural intention.

3.5. Financial security control have influence on users’ behavioural intention

The need for additional security features in the current mobile money banking system is not out of place. Security has become a major issue in the mobile money banking system, of which Ghana is no exception (BACE Group, Citation2019; Kelly & Palaniappan, Citation2019; Paul & Aithal, Citation2019). The general response of most users is their willingness to use the mobile money banking system. However, they admitted that they are much worried about the negative security reportage heard concerning mobile money banking technology. This is supported by reports from organisations working within this mobile ecology (KPMG, Citation2018). The most relevant security recommendation that comes with mobile money banking is mostly related to users taking extra precautions on their devices. Other literature also proposed, among other security precautions, to include two-factor-authentication, the use of a unique password and ensuring secured transaction operation and security settings on the type of mobile technology used (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2019; BACE Group, Citation2019; Kanobe et al., Citation2019) It is upon these that the study seeks to understand how many of these security recommendations should be subjected to the case of Ghana, and the outcome made to both the users and service providers.

The subject of security on the mobile money banking system is very tricky in respect of what needs more than technical controls. This conclusion made is justifiable as a result of information given by experts and technocrats in focus group discussions prior to this study. The discussion revealed the following security challenges related to the mobile banking system in Ghana; there is much room for agents to trade-off the customers’ data to a third party (Pooja et al., Citation2021) without the knowledge of operators even though there are strict regulations set by the government on that (BOG, Citation2015). The exploitation of users registering without any form of personal identification, and finally, the bigger security challenge of all is that most of the administrators of the telcos are equal users of the mobile money banking system, this has resulted in two huge challenges; one, how can a user who serves as an administrator tighten security measures on themselves? Secondly, between an administrator and user, who do they report to when there is a claim of abuse in the mobile money service? There is little security separation of control in the mobile money banking sector on that score, which has been supported by other studies in that regard (Kanobe et al., Citation2019). Regulations on mobile banking are not enough since most of the guidelines have been violated (GSMA, 2015) giving room to some security challenges. It requires a general, deliberate, and conscious effort of collaboration between government, operators, developers and users to overcome the security hurdles neck-deep in the mobile money banking sector. The following propositions were set for the study to understand the role of financial security on mobile money services.

Proposition 010: Financial Security control has an impact on users’ attitudes toward mobile money services.

Proposition 011: There is a significant impact of Financial Security Control on Behavioural Intention

Proposition 012: Financial Security Control have a positive impact on Perceived Ease of Use

Proposition 013: Financial Security Control have a positive impact on the Perceived Usefulness

Table 1. Summary of study hypothesis

4. Research methodology

The primary data procedure was used to collect the study data (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). Quantitative methods is used, with questionnaires to interview mobile money users (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). Any mobile money user in Ghana who is 18 years and above and, thus uses; Vodafone cash, AirtelTigo wallet, and MTN momo were eligible for the study. As of 2021, there were 17.9 million active mobile money banking users in Ghana’s sixteen (16) regions (BOG, 2021). The study engaged seventeen (17) personnel with an academic background ranging from Certificate and Higher national diploma (HND) in Ghana. The study organised a training session with them and piloted the test of the data collection before collecting the main data for the study. The survey questionnaire was administered at the various mobile money banking agents’ venues (where users who came to patronize the services of the agent). The structural equation model with SmartPLS is used to analyze the questionnaire responses (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

4.1. Research approach

The study first had a panel discussion with experts in the mobile money banking industry, these included professionals who had once worked with the banking industry and the Telcos. The study team was unable to meet the mobile money operators, however, the study team had discussions with mobile money agents in their capacity and not representing the institution. They shared insight into the operations of the company they are working for (Vodafone, MTN, and AirtelTigo). Again, a structured survey questionnaire was administered to users of mobile money banking services across the country.

4.2. Sample and sample size

The number of people from whom the data was collected is based on scientific consideration following with diligence in arriving at the sample size. According to Fowler, Citation2013), the sample size calculation requires three elements. First is the margin of error to which the study could work with (from 1 percent to 10 percent), the study used 2 percent to be able include more participant to improve the study outcome. Secondly, the confidence level, is out of 100 percent, confidence interval selected for the study is 95 percent. Finally, the estimate percentage sample respond rate, it mostly within the rate of 50 percent, which the study maintains the same. The sample size used the formula by Uttley (Citation2019) sample size method and Taherdoost (Citation2017), formula. Where n (sample size), p (percentage of population), E(maximum percentage error to tolerate), Z (confidence level). Using the population of 17.9 million mobile money users. The sample size determined from the formula is 2,298. The data collected were sorted out to meet the required standard. Some data were excluded as a result of their deficiency, thus; questionnaire responses which were altered more than once; 57 of such were detected and rejected. There were 46 missing data in the questionnaire. As a result, the final questionnaire used for the analysis is 2,041 after all the incorrect copies were removed, representing a 95.7 percent valid response rate of data collected.

4.3. Data analysis

The survey responses were coded into IBM SPSS statistics application for the data analysis, using the structural equation model (SEM), which was one primary tool to enable exporting it files into other analytical software’s which is supported by SmartPLS. It uses the SEM technique referred to as the partial least square (PLS) which is a second-generation statistical tool (Gefen et al., Citation2003). The study demonstrated that PLS is a better methodological assessment tool and provides robust information with regards to how the data supports the study model. The capability of PLS to simultaneously analyse the relationship model among multiple dependent and independent constructs has been demonstrated in its application to the TAM model (Gefen et al., Citation2003).

4.4. Reliability and validity measures

There were two main constructs of variables for the subject test element considered, endogenous and exogenous construct (Garson, Citation2016; Ringle et al., Citation2020). The endogenous constructs are behavioural intention, attitude, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and actual use. The exogenous on the other hand is government policy and financial security control. The analysis was based on reliability and validity, the construct reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha, AVE, composite reliability, and rho_ A) and construct validity (R-square and Q-square, Heterotrait-Monotrait correlation ratio (HTMT), and Fornell-Larcker Criterion).

5. Result analysis

The study analysis considered the demography of respondents which is summarised in Table . The study also analysed the data for both reliability and validity.

Table 2. Respondent demographic details

Table indicate the demographic representation of the respondent for the study. The percentage of users shows that 47% and 53% represent both males and females respectively. Most age group respondent was aged 29–38 year group representing 34.9% and 18–28 year also represented 22.1%. The level of the educated respondent was Bachelor’s degree representing 32.8% next to that were those with no formal education respondent representing 22.6%s. The occupation of respondents showed that employed users were the most respondent representing 43.2% followed by household workers representing 21.6%.

Table 3. Convergent reliability

5.1. Internal consistency

The reliability of each item was assessed by verifying the cross-loadings, and it was discovered that the values of factor loading on their latent factors were high, thus greater than 0.70. This demonstrates that the reliability of each construct positively contributes to the allocation of each designated latent construct. The CR across all constructs is greater than 0.80, and the AVE values are between 0.603 and 0.835. Table summarizes the CR, AVE, Cronbach Alpha and rho-A, to demonstrate the convergent reliability of the SmartPLS analysis.

5.2. Fornell-Larcker criterion discriminant validity analysis

The Fornell-Larcker criterion is evaluated by comparing the correlation between constructs with the square root of the AVE of a particular construct. The values in bold in Table were greater than the values in the respective row and column, indicating that the measures used in this study were discriminant. The cross-loading criterion was evaluated, and the results revealed that for all constructs, the outer loading exceeded cross-loading and remained valid.

Table 4. Fornell-larcker criterion

5.3. The HTMT discriminant validity analysis

The HTMT ratio test was used to ensure that the model had been thoroughly examined. The HTMT criterion was at least 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2015). As a result, discriminant validity had also been successfully accomplished in the study, with the HTMT inference showing a confidence interval of less than 1.0 for all variables (Henseler et al., Citation2015), even further confirming the discriminant validity. Table shows the cross-reference value with each construct to determine the HTMT validity for the model.

Table 5. Heterotrait-monotrait correlation ratio

5.4. The R2 and Q2 analysis

The R-squared evaluation criterion is to assess the distribution of datasets around the fitted model. It identifies the completely reliant variable’s percentage of variation. The predictive relevance ascertained the strongest interrelations among the structural model’s constructs. To determine the Q2 value for ATT, BIU, PEOU, PEU, and USE, the predictive relevance test was used. A value greater than zero indicates that the model is relevant. The closer the Q2 value was to one (1), the more relevant the model. The inferential relevance values of ATT, BIU, PEOU, PEU, and USE are shown in Table . According to these Q2 values, when ATT was more relevant, the influence on BIU, PEOU and PEU was greater, thus affecting USE further. As clarified by the structural model, the correlation seen between five critical variables (ATT, BIU, PEOU, PEU, and USE) addressed the relevant issues related to Mobile money adoption in Ghana.

Table 6. Endogenous construct validity using and

5.5. The structural model

The conceptual approach takes into account the relationship between the dependent variables within the model.

The study excluded (ATT3) from the analysis as part of the measurement model evaluation due to low factor loadings (<0.600; Hair et al., Citation2017)

After a thorough assessment of the measurement model, the following part evaluates the structural path by considering the path coefficient among constructs used and its related statistical significance. The T-statistic and P-values are used to evaluate the model’s quality.

H01 evaluate whether user Attitude significantly impacts Behavioral Intention. The outcome shows that, users’ attitude significantly impacts on Behavioural Intention (ß = 0.485, t = 17.500, p < 0.001). Hence, H01 was supported.

H02 evaluate whether Behavioural intention negatively impacts Actual use. The outcome shows that, Behavioural Intention significantly negative impacts on Actual use (ß = 0.112, t =5.001, p < 0.001). However, H02 was supported.

H03 evaluate whether Government policies have a significant impact on user Attitude. The outcome shows that, Government policies significantly impacts on user Attitude (ß = 0.397, t = 42.143, p < 0.001). Hence, H03 was supported.

H04 evaluate whether Government policies have a significant impact on Behavioural intentions. The outcome shows that, Government policies significantly impacts on user Behavioural intentions, (ß = 0.841, t = 29.328, p < 0.001). Hence, H04 was supported.

H05 evaluate whether Government policies have a significant impact on Perceived ease of use. The outcome shows that Government policies have significant and positive impacts on user Attitude (ß = 0.397, t = 42.143, p < 0.001). Hence, H05 was supported.

H06 evaluate whether Government policy negatively impacts Perceived usefulness. The outcome shows that Government policies have significantly negative impacts on Behavioural intention (ß = 0.022, t = 11.469, p < 0.001). Consequently, H06 was supported.

H07 evaluate whether Perceived ease of use negatively impacts Behavioural intention. The outcome shows that Perceived ease of use has a significantly negative impact on Behavioural intention (ß = 3.973, t = 3.494, p < 0.001). Consequently, H07 was supported.

H08 evaluate whether there is a significant positive impact of Perceived ease of use on perceived usefulness. The outcome shows that there is a significant positive impact of Perceived ease of use on perceived usefulness (ß = 1.008, t = 1108.423, p < 0.001). Hence, H08 was supported.

H09 was to evaluate whether Perceived usefulness influences behavioural intention to use mobile money services. The result shows that there is a significant positive impact of Perceived usefulness on Behavioural intention (ß = 4.163, t = 3.683, p < 0.001). Hence, H09 was supported.

H010 evaluate whether there is a significantly positive impact of financial security control on users’ attitudes. The outcome shows that there is significantly positive impact of financial security control on user attitude (ß = 0.622, t = 55.641, p < 0.001). Hence, H010 was supported.

H011 evaluate whether there is a significant impact of financial security control (USF) on behavioural intention. The results show that there is significant impact of financial security control on behavioural intention (ß = 0.164, t = 7.336, p < 0.001). Hence, H011 was supported.

H012 evaluate whether financial security controls have a positive impact on Perceived ease of use. The results show that there is a significant impact of financial security control on Perceived ease of use (ß = 0.239, t = 18.970, p < 0.001). Hence, H012 was supported.

H013 evaluate whether financial security control has a positive impact on perceived usefulness. The results reveal that, there is significantly positive impact of financial security control on Perceived usefulness (ß = 0.007, t = 5.346, p < 0.001). Hence, H013 was supported

The hypothesis results are summarized in Table using the structural model. This demonstrates the study outcome through the hypothesis analysis and results.

Table 7. Direct relationship results

Figure depicts a pictorial analysis of the structural model and the links within the construct.

The hypothesis outcome is summarised with the model, the model shows that all the hypothesis sets were achieved using Table and Figure . Figure shows the result of the hypothesis in relation to the conceptual framework outcome.

6. Research discussion

According to the study findings, the growth and usage of mobile money in Ghana clearly show that users’ level of education is not a barrier to adoption. The data showed that 22% of users had no formal education, which is quite interesting to note regarding the level of education in the adoption of mobile money services in Ghana as is the case in the UK (Hampshire, Citation2016). In terms of gender, the data shows that 53 % are females. Furthermore, mobile money services have no restrictions on the type of occupation of a user, as result; mobile money helps to grow both the formal and informal sectors of the Ghanaian economy. There are a couple of studies, related to what factors had influenced mobile users to adopt mobile money banking. This study concept differs from what other authors had carried out related to this subject. The current study is unique in that the constructs considered are completely different from those considered by other studies (Islami et al., Citation2021; Moslehpour et al., Citation2018; Patwardhan, Citation2018; Qureshi et al., Citation2021; Raza et al., Citation2017; Sugandini et al., Citation2018)

This was the case of Gautam et al., (Citation2020) they stated that mobile payment service users should be tested and verified using TAM. The constructs used in Suhartanto et al., (Citation2019) study was remarkably similar to those used in this current study. However, the uniqueness of the current study was based on the use of government and financial security constructs in the determination of model usage in assessing the impact of TAM on user adoption of mobile money services. This distinction is also grounded in the number of participants incorporated into the study, which was definitive and unanimous, resulting in a far-reaching outcome on the subject.

The study discussion was based on the summary of the hypothesis; the attitude of user’s impact on behavioural intention, the behavioural intentions influence actual use, government policies and financial security control impact on behavioural intentions, and perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness impact on attitude.

7. The attitude of users’ impact on their behavioural intention

The concept of adopting and acquiring technology varies; the latter depends on the user’s beliefs and the former depends on the user’s attitude towards technology. Consequently, these two perceptions may change with time and purpose with respect to the user’s interest. The attitude of users toward technology acceptance has proven to be one of the most important variables in the exogenous construct in TAM. Positive user attitudes to technology are critical to determining the actual usage of service or technology. The study finding is supported by other recent authors which determined that attitude influences behavioural intention (Huei et al., Citation2018; Islami et al., Citation2021; Sigurdsson et al., Citation2018).

These studies (Alam et al., Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Gautam et al., Citation2020; Malaquias et al., Citation2018; Singh et al., Citation2020) have all supported users’ attitudes toward technology and mobile money banking in their respective countries. It must also be stated that the study supports the research work of Ajzen, (Citation1989) who indicate that user’s attitude is linked to their affective, cognitive and behaviour, where these described the user’s feeling toward technology or service, the beliefs they have about that service and the impact it brings to their lives respectively. This conclusion is made to support the fact that user attitude has become one of the pivotal and predictive constructs in the acceptance of service and technology (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019; Kelly & Palaniappan, Citation2019; Sigurdsson et al., Citation2018). When a user has a positive attitude toward service, it makes it easier for them to accept that service, as has been demonstrated in other studies (Huei et al., Citation2018; Chawla & Joshi, Citation2019).

Mobile commerce users are more willing to employ mobile money if they believe they are more valuable than costs. In addition, the service charges associated with transactions could appeal to users toward the use of mobile payment applications, the more likely it will gain acceptance quickly (Abooleet et al., Citation2018; Lin et al., Citation2020) Even though for now MTN momo has taken the largest share in terms of users, per this outcome Vodafone cash gradually increasing their market share over MTN momo with their zero cost of charges to users in the mobile money transactions. There are other inherent external variables subject to the user’s attitude to technology adoption. User-perceived usefulness of technology in connection with their business and perceived ease of use of technology have positively impacted users’ attitudes to accepting technology and its related services (Islami et al., Citation2021; Moslehpour et al., Citation2018; Raza et al., Citation2017; Sugandini et al., Citation2018).

8. The behavioural intentions of users influence their actual use

According to the study’s findings, users’ behavioural intentions to use mobile money services were influenced by perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, government policy, and financial security. The study shows that most of the variables in TAM influence one’s attitude leading to their behavioural intentions and ultimately the actual use of technology or services. The study found that when a user has a relative need for a service or technology related to their current work, that user is more likely to adopt that technology or service (Lin et al., Citation2020).

9. Government policies and financial security control have an impact on individual behavioural intentions

There have been few studies on how government policies influence user decisions to adopt mobile banking, and this study is one of the few that has made use of the subject. In the case of (Bowers et al., Citation2017), they focused on the regulation governing the use of mobile money services, which is different from the perspective taken in this study. However, in the study of Bowers et al., (Citation2017), most regulations set to enforce the activities of mobile money services were not adhered to. According to our findings, customers want the government to take more steps to control the affairs and operations of the mobile money ecosystem. This included increased security enforcement for both stakeholders in order to clean up the fraudulent activities associated with mobile money services (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2019). Again, reviewing the various government policy and acts have shown that mobile users have a strong fate in government to strengthen the growth of the mobile money industry (Patnam et al., Citation2020). Also, these policies have strengthened the effort in establishing the process and function to foster users’ trust in adopting mobile money services (Qureshi et al., Citation2021; Younas & Kalimuthu, Citation2021). Government policy (e.g., interoperability and connectivity system) was shown to influence users’ attitudes when the R2 and Q2, HTMT, and Fornell-Larcker criterion were all well within the best acceptable levels to warrant consideration of those constructs. Each of these measures had a favourable outlook on government policy in terms of its impact on users’ adaptation decisions toward mobile money banking services.

The need for additional financial security features increases user trust in mobile money banking. The main point of contention between consumers and telcos over mobile money is the security risks involved with digital financial transactions. The study aim was to determine whether additional security arrangements are required from both ends; whether users and telecoms need to reinforce the current security arrangements in place. According to the findings of the study, participants agreed that the present system’s security should be improved. This is consistent with prior study’s, which revealed that there is a need to strengthen security flaws in the mobile money application system (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2019).

10. The perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness impact on a user’s attitude

According to the findings of the study, the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness constructs dictate that when a user has a relative need for a service or technology related to their current work, that user is more likely to adopt that technology or service (Islami et al., Citation2021; Moslehpour et al., Citation2018; Sugandini et al., Citation2018). These factors also contribute to users’ attitudes and behaviour (Islami et al., Citation2021; Raza et al., Citation2017).

11. Conclusion

Mobile money systems designed in the payment system have played an important role in boosting underrepresented individuals to banking services. Also, it accounts for the financially excluded population, which is especially pertinent in emerging economies, where the proportion of people with mobile money payment accounts is larger than those of adults with regular bank accounts. It further assures that mobile wallet is more effective than traditional ways to purchase goods or services. Mobile money is critical to achieving equitable access to banking services. Switching transfers and earnings to accounts electronically is a huge potential for emerging economies to make payments easier and increase account use (Kingiri & Fu, Citation2019; Priya et al., Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2012).

In the event of a mobile money payment system, the industry players’ most especially the government, have to put in measures that include the legal and regulatory systems’ capacity to cope with these additional technologies. This includes adequately support operating outside of the administrative framework, and additional payment-related concerns (Bowers et al., Citation2017) The pace of innovation is quick, and the legal environment must keep up to control the emerging issues of threats and fraud to undermine the growth and adoption of the industry (Akomea-Frimpong et al., Citation2019).

The study outcome has been on edge for government to understand the trust users had in shaping the mobile money ecology. The reasons why the government could still impose the e-levy tax are clearly linked to this study, where the government knows that citizens strongly believe in government support and control in mobile money banking. The study could not determine at what rate or level of control from the government that would be regression. Thus, to deter citizens’ adoption of mobile money banking. Again, government policy, even though, is generally acknowledged to have an impact on the way citizens involve themselves in governance (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000; Kemal, Citation2019) not much has been scientifically proven. The study has contributed to that gap in the literature. Furthermore, the flexibility and robustness of TAM were tested with a positive outlook. The TAM model showed that government policy and financial security had influenced users’ decisions in adopting mobile money services in Ghana.

Government policy has an impact on the user’s behavioural intention to use mobile money services. The leverage of government policy to enforce how financial transactions are supposed to be done has typically been shown to influence the banking ecology, which includes mobile money and banking services regulation and laws to protect users. This has been shown to have a favourable impact on the user’s willingness to adopt technology and the services enabled by that technology. In this case, it is the Ghanaian mobile money banking service. The study’s analysis showed that government policy had an effect on consumers’ behavioural intention to utilize mobile money services. Thus, the distinguishing factors influencing mobile money banking are perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, financial security, and government policy. These factors had not previously been studied in their current form making them unique and filling the gap in the role of government policies in mobile money services.

Finally, the study’s findings show that government policies and financial security have a strong influence on behavioural intentions to use mobile money. Furthermore, both government policy and financial security have a positive impact on perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness.

Disclosure statement

The team members for this study have no interest, in terms of financial gains to be made or made as a result of this study. This study is purely for academic purposes only.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Afful Ekow Kelly

Afful Ekow Kelly received the Higher National Diploma in Statistics from then Tamale Polytechnic, now Tamale Technical University, Master’s degree in Information Technology from Open University Malaysia. He is currently pursuing his PhD from Malaysia University of Science and Technology, his area of interest includes, Data Science, Social engineering, Statistics, Education, Law, Data forensics, Information security, Public accountability, National politics, Mobile banking and technology.

Sellappan Palaniappan

Sellappan Palaniappan Malaysia University of Science & Technology School of Science and Engineering Petaling Jaya, Malaysia Professor and Head of Department of Information Technology, Malaysia University of Science and Technology Sellappan Palaniappan received a bachelor’s degree in statistics from the University of Malaya, an M.Sc. degree in computer science from the University of London, U.K., and a PhD degree in interdisciplinary information science from the University of Pittsburgh (USA). He is currently a Professor of IT, the Dean of the School of Science and Engineering, and the Provost of the Malaysia University of Science and Technology. His research interests include data science, social media analytics, health informatics, blockchain, cloud computing, web services, cybersecurity, the IoT, and education 4.0.

References

- Abayomi, O. J., Olabode, A. C., Reyad, M. A. H., Teye, E. T., Haq, M. N., & Mensah, E. T. (2019). Effects of demographic factors on customers’ mobile banking services adoption in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 10(1), 63–22. https://doi.org/10.30845/ijbss.v10n1p9

- Abooleet, S., Fang, X., Acker, A., & Murthy, D. (2018, July). Venmo: Understanding mobile payments as social media. In Proceedings of the 9th international conference on social media and society (pp. 5–12).

- Acker, A., & Murthy, D. (2018). Venmo: Understanding mobile payments as social media. In Proceedings of the 9th international conference on social media and society (pp. 5–12).

- Ajzen, I. (1989). Attitude structure and behavior. Attitude Structure and Function, 241, 274. https://books.google.com.gh/books?hl=en&lr=&id=av8hAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT248&ots=fGvru4u69j&sig=KH4B4yXPKFEEDeY9Lvx0yK-fft8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Akomea-Frimpong, I., Andoh, C., Akomea-Frimpong, A., & Dwomoh-Okudzeto, Y. (2019). Control of fraud on mobile money services in Ghana: An exploratory study. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 22(2), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMLC-03-2018-0023

- Alam, S. S., Omar, N. A., Ariffin, M., Azmi, A., & HashimandHazrul, N. N. M. (2018). Integrating TPB, TAM and DOI theories: Empirical evidence for the adoption of mobile banking among customers in Klang Valley, Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management Science, 8(2), 385–403.

- BACE Group. (2019). Challenges faced by mobile financial services in Ghana, https://medium.com/@bacehq/challenges-faced-by-mobile-financial-services-in-ghana-c97b8ef6eb5a ( Date of use 15 March 2020)

- Bank of Ghana. (2015). Guidelines for E-Money Issuers in Ghana, https://www.bog.gov.gh/privatecontent/Banking/E-MONEY%20GUIDELINES-29-06-2015-UPDATED5.pdf ( Date of use 22 March 2017)

- Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

- Berry, F. S., & Berry, W. D. (2018). Innovation and diffusion models in policy research. Theories of the Policy Process, 253–297. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0747563220301771?token=795574BE34AF36F6C55B7D1CECA6D44449A4A9E3386C91684F59BC1C30BAD0D7173751B595F383AD779BA3A1825583E6&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20221020124213

- Bowers, J., Reaves, B., Sherman, I. N., Traynor, P., & Butler, K. (2017). Regulators, mount up! analysis of privacy policies for mobile money services. In Thirteenth symposium on usable privacy and security (SOUPS 2017) (pp. 97–114).

- Bryant, J., Holloway, K., Lough, O., & Willitts-King, B. (2020). Bridging humanitarian digital divides during Covid-19. HPG (ODI). https://www.odi.org/publications/17580-bridging-humanitarian-digital-divides-during-covid-19

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2019). Consumer attitude and intention to adopt mobile wallet in India–An empirical study. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(7), 1590–1618. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-09-2018-0256

- Chigada, J., & Hirschfelder, B. (2017). Mobile banking in South Africa: A review and directions for future research. South African Journal of Information Management, 19(1), 1–9. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.4102/sajim.v19i1.789

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- David-West, O., Oni, O., & Ashiru, F. (2021). Diffusion of innovations: Mobile money utility and financial inclusion in Nigeria. Insights from Agents and Unbanked Poor End Users. Information Systems Frontiers, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-021-10196-8

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology‟. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (2000, January). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

- Doris, F. A., & Caroline, T. (2017). Mobile money use in Ghana: An assessment of its relevance in the financial inclusion of rural communities. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 4(7), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.47.2950

- Featherman, M. S., & Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. International Journal of human-computer Studies, 59(4), 451–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-5819(03)00111-3

- Fishbein, M., Jaccard, J., Davidson, A. R., Ajzen, I., & Loken, B. (1980). Predicting and understanding family planning behaviors. In Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall. https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/predicting-and-understanding-family-planning-behaviors

- Fowler, F. J., Jr. (2013). Survey research methods. Sage publications.

- Garson, G. D. (2016). Partial least squares regression & structural model. Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishers Publications. 978-1-62638-039-4.

- Gautam, S., Kumar, U., & Agarwal, S. (2020, June). study of consumer intentions on using mobile wallets using tam model. In 2020 8th international conference on reliability, infocom technologies and optimization (trends and future directions)(ICRITO) (pp. 203–207). IEEE.

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036519

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2 ed.). Sage.

- Hampshire, C. (2016). Exploring UK consumer perceptions of mobile payments using smart phones and contactless consumer devices through an extended technology adoption model. ( Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2015(43), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hillman, S., & Neustaedter, C. (2017). Trust and mobile commerce in North America. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.061

- Huei, C. T., Cheng, L. S., Seong, L. C., Khin, A. A., & Bin, R. L. L. (2018). Preliminary study on consumer attitude towards finTech products and services in Malaysia. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(2.29), 166–169. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i2.29.13310

- Islami, M. M., Asdar, M., & Baumassepe, A. N. (2021). analysis of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use to the actual system usage through attitude using online guidance application. Hasanuddin Journal of Business Strategy, 3(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.26487/hjbs.v3i1.410

- Kanobe, F., Alexander, P. M., & Bwalya, K. J. (2017). Policies, regulations and procedures and their effects on mobile money systems in Uganda. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 83(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2017.tb00615.x

- Kanobe, F., Alexander, M. P., & Bwalya, K. J. (2019, July). information security management scaffold for mobile money systems in Uganda. In Proceedings of the 18th European conference on cyber warfare & security, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal (pp. 4–5).

- Katusiime, L. (2021). Mobile money use: The impact of macroeconomic policy and regulation. Economies, 9(2), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9020051

- Kelly, A. E., & Palaniappan, S. (2019). Survey on customer satisfaction, adoption, perception, behaviour, and security on mobile banking. Journal of Information Technology & Software Engineering, 9(2), 1–15 https://soi.org/10.35248/2165-7866.19.9.259.

- Kemal, A. A. (2019). Mobile banking in the government-to-person payment sector for financial inclusion in Pakistan. Information Technology for Development, 25(3), 475–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2017.1422105

- Khan, B. U. I., Olanrewaju, R. F., Baba, A. M., Langoo, A. A., & Assad, S. (2017). A compendious study of online payment systems: Past developments, present impact, and future considerations. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 8(5), 256–271. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3e60/35d2232d5f3db969a88d48695b6c58361609.pdf

- Kingiri, A. N., & Fu, X. (2019). Understanding the diffusion and adoption of digital finance innovation in emerging economies: M-Pesa money mobile transfer service in Kenya. Innovation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2019.1570695

- KPMG. (2018). Digital paymentsAnalysing the cyber landscape, https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/ca/pdf/2017/04/digital-payments-analysing-the-cyber-landscape-kpmg-canada.pdf (Date of use 21 March 2017)

- Lakshmi, K. K., Gupta, H., & Ranjan, J. (2017, December). USSD—Architecture analysis, security threats, issues and enhancements. In 2017 international conference on infocom technologies and unmanned systems (trends and future directions)(ICTUS) (pp. 798–802). IEEE.

- Lin, K. Y., Wang, Y. T., & Huang, T. K. (2020). Exploring the antecedents of mobile payment service usage: Perspectives based on cost–benefit theory, perceived value, and social influences. Online Information Review, 44(1), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-05-2018-0175

- Luna, I. R., Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Munoz-Leiva, F. (2019). Mobile payment is not all the same: The adoption of mobile payment systems depending on the technology applied. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 146, 931–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.09.018

- Malaquias, F., Malaquias, R., & Hwang, Y. (2018). Understanding the determinants of mobile banking adoption: A longitudinal study in Brazil. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 30, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2018.05.002

- Malinga, R. B., & Maiga, G. (2020). A model for mobile money services adoption by traders in Uganda. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 86(2), e12117. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12117

- Markoska, K., & Ivanochko, I. (2018). Mobile banking services—business information management with mobile payments. In Agile information business (pp. 125–175). Springer.

- Martin, A. (2019). Mobile money platform surveillance. Surveillance & Society, 17(1/2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12924

- McLeod, B. D. (2009). Understanding why therapy allegiance is linked to clinical outcomes. 16(1), 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01145.x

- Merhi, M., Hone, K., & Tarhini, A. (2019). A cross-cultural study of the intention to use mobile banking between Lebanese and British consumers: Extending UTAUT2 with security, privacy and trust. Technology in Society, 59, 101151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101151

- Mew, J., & Millan, E. (2021). Mobile wallets: Key drivers and deterrents of consumers’ intention to adopt. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 31(2), 182–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2021.1879208

- Mingis, K. (2020). Tech pitches in to fight COVID-19 pandemic. Computerworld. https://www.computerworld.com/article/3534478/tech-pitches-in-to-fight-covid-19-pandemic.html

- Moslehpour, M., Pham, V. K., Wong, W. K., & Bilgiçli, İ. (2018). E-purchase intention of Taiwanese consumers: Sustainable mediation of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Sustainability, 10(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010234

- Patnam, M., Yao, W., & Haksar, V. (2020). the real effects of mobile money: Evidence from a large-scale fintech expansion. IMF Working Papers, 2020(138). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/07/24/The-Real-Effectsof-Mobile-Money-Evidence-from-a-Large-Scale-FintechExpansion-49549

- Patwardhan, A. (2018). Financial inclusion in the digital age. In Handbook of blockchain, digital finance, and inclusion (Vol. 1, pp. 57–89). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-810441-5.00004-X

- Paul, P., & Aithal, P. S. (2019, October). Mobile applications security: An overview and current trend. In Proceedings of national conference

- Payne, E. M., Peltier, J. W., & Barger, V. A. (2018). Mobile banking and AI-enabled mobile banking: The differential effects of technological and non-technological factors on digital natives’ perceptions and behavior. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing,12(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-07-2018-0087

- Pooja, K., Shilpa, G., & Shruti, P. (2021). mobile agent communication, security concerns, and approaches: an insight into different kinds of vulnerabilities a mobile agent could be subjected to and measures to control them. In Research anthology on securing mobile technologies and applications (pp. 23–34). IGI Global.

- Priya, R., Gandhi, A. V., & Shaikh, A. (2018). Mobile banking adoption in an emerging economy. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(2), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-01-2016-0009

- Qureshi, F., Rea, S. C., & Johnson, K. N. (2021). (Dis) creating claims of financial inclusion: The integration of artificial intelligence in consumer credit markets in the United States and Kenya. Journal of International and Comparative Law, 8, 405. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/jintcl8&div=20&id=&page=

- Radaelli, C. M. (2005, October). Diffusion without convergence: How political context shapes the adoption of regulatory impact assessment. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(5), 924_943. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500161621

- Raza, S. A., Umer, A., & Shah, N. (2017). New determinants of ease of use and perceived usefulness for mobile banking adoption. International Journal of Electronic Customer Relationship Management, 11(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJECRM.2017.086751

- Rehman, S. U., Bhatti, A., Mohamed, R., & Ayoup, H. (2019). The moderating role of trust and commitment between consumer purchase intention and online shopping behavior in the context of Pakistan. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0166-2

- Renaud, K., Orgeron, C., Warkentin, M., & French, P. E. (2020). Cyber security responsibilization: an evaluation of the intervention approaches adopted by the Five Eyes countries and China. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13210

- Reyes-Mercado, P., Karthik, M., & Mishra, R. K. (2020). What's in a brand name? Preferences of mobile wallets in India under a shifting regulation. International Journal of Business Forecasting and Marketing Intelligence, 6(2), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBFMI.2020.109880

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

- Scherer, F. M. (1980). Industrial market structure and economic performance. Houghton-Mifflin.

- Sigurdsson, V., Menon, R. V., Hallgrímsson, A. G., Larsen, N. M., & Fagerstrøm, A. (2018). Factors affecting attitudes and behavioral intentions toward in-app mobile advertisements. Journal of Promotion Management, 24(5), 694–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2018.1405523

- Singh, N., Sinha, N., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. J. (2020). Determining factors in the adoption and recommendation of mobile wallet services in India: Analysis of the effect of innovativeness, stress to use and social influence. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.05.022

- Sugandini, D., Purwoko, P., Pambudi, A., Resmi, S., Reniati, R., Muafi, M., & Adhyka Kusumawati, R. (2018). The role of uncertainty, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness towards the technology adoption. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET), 9(4), 660–669.

- Suhartanto, D., Dean, D., Ismail, T. A. T., & Sundari, R. (2019). Mobile banking adoption in Islamic banks: Integrating TAM model and religiosity-intention model. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(6), 1405–1418. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-05-2019-0096

- Taherdoost, H. (2017). Determining sample size; how to calculate survey sample size. International Journal of Economics and Management Systems, 2.

- Tidd, J., & Bessant, J. R. (2020). Managing innovation: Integrating technological, market and organizational change. John Wiley & Sons.

- Tiong, W. N. (2020). Factors Influencing Behavioural Intention towards Adoption of Digital Banking Services in Malaysia. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 10(8), 450–457.

- Uttley, J. (2019). Power analysis, sample size, and assessment of statistical assumptions—Improving the evidential value of lighting research. Leukos.

- Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. G. (2000). Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 115–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250981

- World Bank. (2012), Innovation in retail payments worldwide: A snapshot. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/financialsector/resources/282044-1323805522895/innovations_in_retail_payments_worldwide_consultative_report(10-17).pdf