Abstract

Urban fringe food production plays a critical role in bridging the urban demand-supply gap by reducing the distance between the markets and farms, making food affordable in cities. Studies show that urbanisation is hampering agriculture activities at the fringes of African cities due to the intense competition for land between developers and farmers. However, the interface between staple food crop production at the urban fringes and urbanisation has not been given sufficient scholarly attention in Ghana. This study draws evidence from Wa, Ghana to examine how urbanisation pressures affect staple food crop production using the mixed research method approach. Data were collected from 408 farmers supported by key informant interviews involving chiefs, family heads, lead farmers, leaders of women groups, and relevant officials of relevant state institutions, while pictures were taken to validate participants’ claims. The quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, cross tabulation, and the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, whereas key informant interviews were subjected to thematic analyses. The findings show that urbanisation pressures have adversely affected staple crop production through declining land availability, low crop harvest, and the dropping of some crops. Therefore, the farmers resorted to cultivating on isolated patchy plots, intercropping, sub-division of small plots, and fertiliser applications to sustain production. However, high inputs cost, climate change, and land tenure insecurity limited food production. Planning schemes should make provision for food crop production, while the Municipal Assembly liaises with NGOs and the Department Agriculture Department to assist farmers to prepare organic fertiliser using local materials to boost production.

1. Introduction

Food production on the fringes of cities, especially in the sub-Saharan Africa, is gaining attention from policy makers, planners, academics, and advocates because of its critical role in bridging the food demand-supply gap in cities (Diekmann et al., Citation2020; Opitz et al., Citation2016). In urban fringes, food production takes the form of home gardens and conventional farms to produce for both home consumption and the urban market (Diekmann et al., Citation2020). Through this, farmers can meet their household food needs, supply to the urban market, and permit city residents to reconnect with the farms where the food is produced (Olsson et al., Citation2016). The works of both Olsson et al. (Citation2016) and Chihambakwe et al. (Citation2018) underscored the importance of urban fringe food production as one that helps to reduce residents’ dependence on the global food systems and at the same time lessen their vulnerability regarding disruption in the supply chain. It also encourages the demand for local food to increase, creating a market for local producers to earn income, reduce their expenditure on food, as well as meet households’ nutritional needs (Chihambakwe et al., Citation2018; Crush et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, it makes local foods available in the local urban markets, and supports the local food economy through consumption, employment, and income generation. Therefore, the critical role of urban fringe food production in feeding the urban population cannot be overemphasised, especially in sub-Saharan Africa where much of the future urbanisation is expected to happen. Suffice it to say, 55% of the global population already reside in cities and consume up to 80% of all food produced in the world; however, the number of people who will be involved in production in and around cities is expected to reduce (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Citation2019). This may, perhaps, hinder the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2, which promises to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture (Diekmann et al., Citation2020) that can translate into food security and contributing to the resilience of cities. Following Chang, DeFries, Liu, and Davis (Citation2018), this study conceives a staple food as one that is regularly eaten in a population in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a standard diet, supplying a large fraction of calories and serving as important sources of macronutrients, key vitamins, and minerals that are necessary for human sustenance.

In sub-Saharan Africa, urban fringe food production is a critical activity that provides food to meet the needs of both urban and urban fringe residents. However, recent studies (Abdulai, Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Chihambakwe et al., Citation2018; Olsson et al., Citation2016) show that urbanisation has led to fierce competition between private developers, businesses, and local farmers for urban fringe lands for different uses that ultimately reduce food production and amplifies the visibility of food insecurity in cities. In the literature that discusses urban fringe production (Bonye et al., Citation2021; Kuusaana et al., Citation2022; Osumanu & Ayamdoo, Citation2022), fierce competition between private developers and local farmers has evolved into informal land markets that does not make room for food production. The fierce competition is largely fuelled by urbanisation, which has become a common phenomenon, especially in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Citation2019; Zhang, Citation2016). In general terms, urbanisation measures the percentage of a country’s people living in cities vis-à-vis those in rural areas (Myers, Citation2021), but others view it as both increasing urban population and the expansion of the surface area of cities (Benis & Ferrão, Citation2017; Hong et al., Citation2021; Zhang, Citation2016) encroaching on farmlands and resources in the surrounding communities. Therefore, the proportion of people living in cities coupled with the rate of physical growth defines the level of urbanisation in a country. It is worth noting that urbanisation is largely driven by the relocation of people from the rural areas to cities in search of social and economic opportunities to improve their living conditions; this way, it transforms the social, economic, and political features of the surrounding areas in profound and distinctive ways (Chen et al., Citation2021). Consequently, urbanisation drives the global economy via knowledge creation, innovation, increased production, and better services provision (Chen et al., Citation2021; Zhang, Citation2016), incentivising rural people to move to cities to pursue their aspirations.

However, the high concentration of people in these areas has its attendant challenges that confront city managers and policymakers, particularly in emerging cities and small towns in sub-Saharan Africa, but ironically, these areas have received less attention in the southern urbanisation discourse and theories (Myers, Citation2021). This is happening amid urban fringe food production challenges occasioned by increasing urban population and the associated large demand for land for various purposes. This, for example, leads to the replacement of agricultural activities with non-farming activities as reported in previous studies (Bonye et al., Citation2021). The work of Paul et al. (Citation2021) revealed that the physical expansion of Delhi in India led to the decline in urban fringe agricultural land by more than 38% between 1973 and 2017. On their part, Willkomm et al. (Citation2021) reported a reduction in farmlands in the urban fringes of Nakuru in Kenya and this manifested in the increase in the number of small farmlands (less than 0.6 ha) and a reduction in large ones (1.06 ha and above) between 2010 and 2019. Similar results have been reported in Bolgatanga by Osumanu and Ayamdoo (Citation2022) and in Wa by Bonye et al. (Citation2021) in Ghana. This development could adversely affect food production, and this is buttressed by Bonye et al. (Citation2021) when they quoted an urban fringe farmer in Wa in Ghana as saying that “‘We are now in difficult times. We struggle for food today, which we never thought of 30 years ago. Urbanisation has claimed all our lands for residential and infrastructural development”. This illustrates how urbanisation pressures have adversely affected food production in emerging cities. In urban studies, the fringe area denotes the area that lies between the boundaries of the city and the adjoining hinterland and exhibits both rural and urban characteristics as well as performs new socio-economic functions (Surya, Citation2016).

Although studies on urban and urban fringe agriculture in emerging cities in sub-Saharan Africa and Ghana in particular are not scarce (Afriyie et al., Citation2020; Bonye et al., Citation2021; Chihambakwe et al., Citation2018; Willkomm et al., Citation2021), the specific issues relating to the effects of urbanisation pressures on staple crops production, its impact on urban food supply, and the farmers’ adaptation mechanisms and constraints, have not been adequately addressed in the extant literature, creating a knowledge gap regarding the nuances of staple food production under urbanisation pressures. For instance, Afriyie et al. (Citation2020) investigated how urban sprawl affects agricultural livelihoods and reported that the phenomenon led to the decline in land for farming at the fringes of Kumasi in Ghana where farmers adapted crop diversification in response but did not explain how staple crop production and supply to the urban market were affected. In Bolgatanga in Ghana, Osumanu and Ayamdoo (Citation2022) reported similar findings but did not consider how that was impacting food supplies to the urban market. The only study in Wa that centred on food crop production is that of Bonye et al. (Citation2021) who focused on agricultural land use and food security and reported that the crop yields had reduced between 2009 and 2018 due to the rapid conversion of lands to non-agricultural uses but did not discuss how it impacted urban food supply, the adaptation measures, and constraints thereof. The works of other researchers in sub-Saharan Africa (Coulibaly & Li, Citation2020; Lasisi et al., Citation2017) likewise revealed that urbanisation created urban fringe farmland loss, creating food production challenges. But these studies fall short of explaining the effects on staple food crops, the urban food supply, adaptation mechanisms, and challenges thereof. To address these knowledge gaps, this study draws evidence from Wa in Ghana to examine: (1) how urbanisation pressures affect selected staple food production and its impacts on urban food supplies; (2) the adaptation mechanisms; and (3) constraints encountered. Providing information for policymakers and planners for designing efficient and coherent policy responses and strategies regarding urban fringe farmland preservation and local food production as part of multifunctional land use would be the utility of this work. The paper is divided into five sections. The next section discusses the extant literature and focuses on urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa and food production in the context while section three presents the methodology, study area, and methods of data collection and analysis. In section four, the results and discussion are presented while the conclusions and policy recommendations constitute the final section.

2. Literature review

2.1. Contextualising urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa

Urbanisation is now a global phenomenon since there are more people in urban areas than in any other period of history. The works of both Cohen (Citation2006) and Angel (Citation2012) consider urbanisation as a widespread and domineering phenomenon in the 21st century. In discussing the literature on urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa, the dependency, modernisation, and neo-liberal theories provide the lenses for understanding its nuances and effects on urban fringe food production. From the dependency theory perspective, urbanisation is viewed as the spatial outcome of global capitalism and the spatial organization thereof that leads to uneven development between cities and rural areas, while the modernisation theory considers it as the foundation through which technology and culture diffuse to shape a society’s outlook (Peng et al., Citation2011). On the other hand, the neo-liberal theory views African urbanisations as one driven by private sector investment in housing, infrastructure, and services provision enabled by the implementation of neoliberal urban growth legislations, policies, and strategies (Van Noorloos & Kloosterboer, Citation2018). Generally, the urbanisation in the emerging cities is fuelled by several factors: natural population increase, rural-urban migration, and the demand for land for housing purposes, which together contribute to the expansion of the city’s boundaries through the annexation and the transformation of surrounding rural areas into urbanised or semi-urbanised areas (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Citation2019). The phenomenon has thrived in recent times because cities are centres of production, and consumption, with greater and better employment opportunities, larger service provision and better access to modern technology (OECD/European Commission, Citation2020). Currently, there are more people (55%) living in cities than in rural areas across the world and this trend is expected to continue as more countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, become more urbanised (OECD/European Commission, Citation2020; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Citation2019). According to OECD/European Commission (Citation2020), up to 90% of future global urbanisation will happen in emerging and developing countries, especially in Asia and Africa, where small and medium-sized cities grow faster than any other region. This will not only make these regions the centres of urbanisation, but also areas of high food demand to feed the increasing number of people in and around cities in sub-Saharan Africa.

It is worth noting that urbanisation in the sub-Saharan Africa region in particular displays certain unique characteristics that are distinct from those reported in the developed countries. The genesis of modern urbanisation in developed countries is largely influenced by the industrial revolution of the 1800s in Europe and the United States, which triggered efficiency in the factors of production (land, labour, capital, and technology), helping these regions to achieve economic development and attracting people from the rural to urban areas in search of jobs (Kundu & Pandey, Citation2020). Today, North America is the most urbanised region in the world with 82% of its people living in urban areas, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (80%), and Europe (73%) (Leeson, Citation2018). Urbanisation in these regions is well structured, making provision for various land uses; industrial, commercial, infrastructure, administration, and recreational (Muzenda, Citation2022). However, recent studies are showing that the biggest cities in these countries are losing their population through counter urbanisation, which entails the movement of people away from the city to rural environments in search of larger, more comfortable, and close-to-nature dwellings (Bosworth & Bat Finke, Citation2020; Seifollahi-Aghmiuni et al., Citation2022).

Urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa is driven by informality and population growth fuelled by rural-urban migration (Amoako & Inkoom, Citation2018; Finn & Cobbinah, Citation2022; Muzenda, Citation2022). Following Finn and Cobbinah (Citation2022), informality is conceived as the different urban structures and relations consisting of informal land tenure arrangements and housing systems, informal settlements and economic activities, and informal “paralegal” governance structures that characterise urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa. Informal urbanisation often manifests either through the occupation and utilisation of lands and their resources without statutory rights or building in ways that undermine relevant laws and customary practices. This is, in part, driven by the inability of the statutory institutions to enforce property rights laws, creating alternative interests in land (Stacey, Citation2018). Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive urban planning experience and weak enforcement of building and property laws in many African cities, and customary land ownership arrangement accompanied by structural adjustment induced privatisation and market-oriented policies fuel Informal urbanisations in sub-Saharan Africa (Stacey, Citation2018; Abdulai et al., Citation2022; Muzenda, Citation2022). It is also a known fact that urban sprawling, which is a common feature of African urbanisation, often leads to land fragmentation and uncoordinated developments in cities, creating a challenge for people to access land for various purposes (Finn & Cobbinah, Citation2022; Stacey, Citation2018). These together translate into informal urbanisation with private developers as the key drivers in sub-Saharan African cities.

It is worth noting that urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa is not accompanied by or preceded by economic growth (Cheru, Citation2005), creating, for example, a deficit in meeting the infrastructural, economic, and social needs of cities. This means that understanding urbanisation in the sub-Saharan African context requires a differentiated analysis of its effects. Characteristically, sub-Saharan African urbanisation is marked and driven by rural urban migration of young people seeking opportunities in the cities to improve their living conditions. However, the rural urban migration experienced in sub-Saharan Africa, precedes industrial revolutions and economic growth (Awumbila, Citation2017; Cheru, Citation2005). These observations should be a source of concern because as more people move into the cities without adequate job opportunities coupled with declining food production, we can expect urban poverty, social vices, and food insecurity to surge, creating more problems for city authorities and national governments.

2.2. Urbanisation and food crop production on the fringes of sub-Saharan African cities

Urban fringe residents can participate in the local food production as gardeners or farmers for household consumption and or urban markets (Diekmann et al., Citation2020); and through this, fresh local products including staple food could be supplied to urban residents, and improve food access (Siegner et al., Citation2018; Diekmann et al., Citation2020). Suffice it to say, food supplies and distributions should be enhanced as more people move into the cities, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa, which are expected to be home to more future urban population centres by 2030. This is because the global objective of creating a world in which everyone is adequately nourished is more urgent in sub-Saharan African cities than anywhere else. Yet, evidence shows that staple food production is severely affected by rapid urbanisation and unsustainable land consumption, particularly on the fringes of African cities. The situation could result in non-availability or limited land for food production and thus threaten food security not only on the fringes of cities but also for those living around them. This is because rural farmers may not be able to bridge the urban demand-supply gap in African cities, against the backdrop that the increasing number of people in these areas will continue to trigger relentless demand for food. However, analysis of the nexus between urbanisation and agriculture on the fringes of cities is not a novelty. The work of Nicodemus et al. (Citation2010) in Kenya revealed the ways through which urbanisation exerts pressure on urban fringe food production as the loss of agricultural lands to urban uses and the reduction in the number of residents evolved. In Nigeria, Lasisi et al. (Citation2017) revealed that farmer households lost their lands to urbanisation pressures, compelling most of them to turn to non-farm activities for survival. Although these studies are critical to enhancing our understanding of the nexus between urbanisation pressures and food production, they did not discuss how food production and supply to urban markets were affected. Pauleit et al. (Citation2019) likewise reported a loss of highly fertile agricultural lands through ubanisation in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia but acknowledged that vegetable production at the fringes of the city is valuable to the residents due to proximity advantages.

Previous studies in Ghana have shown similar results. For instance, although farmers’ proximity to local markets provided an opportunity for them to sell their produce, and improve incomes, Afriyie et al. (Citation2020) discovered that urbanisation pressures led to the reduction of arable lands on the fringes of Kumasi. However, food crop farming persisted through crop diversification, agricultural intensification, and agricultural extensification. Bonye et al. (Citation2021) revealed that urbanisation in Wa led to a reduction in crop yields in the urban fringes due to the declining size of their farmlands, which suggests that the activity remains an important livelihood strategy of the indigenes. However, the study did not account for the impact on urban food supply and the measures taken to remain in farming as well as the adaptation constraints. In Bolgatanga, Ghana, Kuusaana et al. (Citation2022) revealed that urbanisation led to the loss or reduction in the availability of fertile agricultural lands in the urban fringes, but food crop farming survived through the relocation to distant communities and the subdivision of plots for the cultivation of different crops. Similarly, Osumanu and Ayamdoo (Citation2022) reported the expansion of Bolgatanga and the loss of arable agricultural lands on the fringes, and subsequent decline in food production among local households. Like the other studies reviewed, the effects on urban food supply, the adaptation strategies, and the constraints did not find space in their study. These knowledge gaps inspired this current study to grasp the interface between urbanisation pressures and urban staple food production so that appropriate policy responses and urban planning pathways could be proposed to support staple food production and sustainable urbanisation in Ghana and in sub-Saharan Africa in general.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of study area

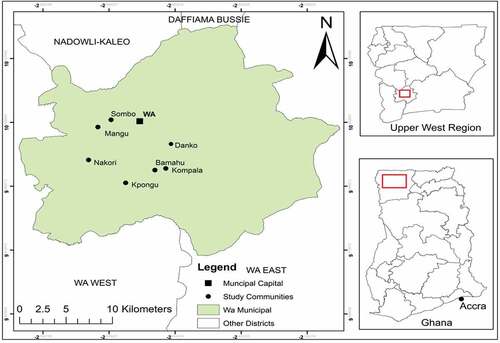

The study was carried out in seven urban fringe communities in Wa. The city, which serves as the capital of the Wa Municipality and the Upper West Region, is considered one of the fastest growing cities in Ghana. The city is located (Figure ) in the Guinea savannah ecological zone and lies on latitudes 1°40ʹN to 2°45ʹN and longitudes 9°32ʹW to 10°20ʹW (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2012). Although the Municipality is largely urban, the dominant livelihood activity is crop farming as 30.9% of households engage in it for their sustenance. However, the proportion of the population engaged in agriculture (crop farming) is higher (58%) in rural localities including urban fringe communities. It is, however, critical to mention that most (82.9%) of the households were engaged in food crop farming (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2012). The agricultural activities (crop farming) of the residents are perhaps enabled by the climate and Guinea savannah vegetation that dominate the area. The climate is relatively two distinct seasons: dry and wet seasons. The wet season is characterised by a short, single rainfall regime (from May to October) but much of the heavy rains are recorded in a few days (in July and August) with an annual rainfall amount that varies from 750 mm to 1050 mm. The dry season, on the other hand, occurs from November to March and is characterised by high temperatures ranging from 14°C at night to 40°C during the day. The accompanying vegetation is characterised by vast areas of grassland, interspersed with the Guinea Savannah woodland comprising drought-resistant trees such as the dawadawa, shea, acacia, baobab, and mango. The area also has shorter shrubs and short grass that provide fodder for livestock. The climate alongside the Guinea Savannah vegetation cover supports the cultivation of maize, sorghum, millet, rice, groundnut, cowpea, soybean, yam, cassava, beans, and Bambara beans.

Figure 1. Study area within the regional and national context.

The study was carried out in Wa because recent studies show the city has been growing in surface and population since the 1980s. For instance, Korah et al. (Citation2018) reported that the city grew by 5.73 times between 1986 and 2016 but much of the growth occurring from 1986 to 2000 (9.82%). Likewise, Osumanu et al. (Citation2019) reported that the built-up area of Wa increased by 35.5% from 2001 to 2014 before rising to 49.8% by 2016 and occupying more than 40 km2. Suffice it to say, the growth of the surface area of the city is driven by urban population increases recorded over the years. The population of the city was 37,954 in 1986, which grew to 67,922 in 2001 before rising to 71,051 in 2010. It further grew to 76,973 in 2014 and 79,954 in 2016 before reaching 143,358 in 2021 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2012, Citation2022; Osumanu et al., Citation2019). As this study will demonstrate, the increase in urban population and the consequent expansion of the surface area of the city have led to the absorption of the urban fringe communities leading to perhaps the loss of farmlands for food production, reduction in crop harvest and food supplies to the urban market.

3.2. Study design

The study used the mixed method research approach to collect data, analyse, and make inferences. The mixed method research design permits researchers to use multiple approaches to answer research questions to gain a broader and more in-depth understanding of the issue of interest. Therefore, the approach entails the purposeful use of both quantitative and qualitative approaches to collect and analysis data and interprets the evidence for the purpose of broadening an understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Ivankova et al., Citation2006; Shorten & Smith, Citation2017). The use of a mixed methods research design improves the utility of the findings of a study because it offers the opportunity to gain a complete understanding of a research problem by examining the issue from different perspectives (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). In this case, the researcher can use the strengths of one method to overcome the weaknesses in another method and by so doing generate corroborative, stronger, useful findings (Dawadi et al., Citation2021; Ivankova et al., Citation2006; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). Specifically, the concurrent mixed research design was the strategy of inquiry. The design involves the collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously but analysed separately; and the findings were mixed during the interpretation stage to complement each for a broader and more in-depth understanding of the nuances of urbanisation pressures on staple food production at the urban fringes (Dawadi et al., Citation2021; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). The advantage of using the concurrent mixed research design is that it helps to confirm, corroborate, or cross-validate the results of quantitative and qualitative data within a single study (Terrell, Citation2012). This informed the decision to gather quantitative and qualitative data in this study. This helped the researcher to gain a deeper and broader understanding of the issue under investigation. In this case, data obtained from the quantitative and the qualitative approaches were linked at appropriate stages of the process; and in so doing, helped to provide a more panoramic view of the issue being investigated (Shorten & Smith, Citation2017). The approach was used in this study because issues relating to, for example, crop yields obtained required the collection of quantitative data, while the nuances of the adaptation mechanisms and challenges urbanisation pressures could be understood with the aid of qualitative data. This helped the researcher to compare the results of the two sets of data to establish convergence or divergence and to strengthen the findings of the study.

3.3. Sample size determination and sampling procedures

Both probability and non-probability sampling procedures were employed in the selection of the research communities and participants. Purposive sampling procedure was used to select the communities. The communities were purposively selected because recent studies (Abdulai, Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Bonye et al., Citation2021) show that they are the most affected by the urbanisation pressures in the city. The sampled communities are Danko, Bamahu, Kompala, Nakori, Kpongu, Mangu, and Sombo. Thereafter, the total indigenous householdFootnote1 population data for each of the seven communities were obtained from the Community-Based Health Planning Services (CHPS) facilities. The CHPS provided total indigenous households’ data that were used to calculate the sample size for the study. The data from these facilities were used to calculate the sample size because the Ghana Statistical Service did not have current community-level data at the time of the study. The data were obtained from the CHPS facilities after the Municipal Health Directorate granted the researcher permission to do so. The total indigenous households in all the seven communities summed up to yield 3,375 households, which were then inputted into the relation: = N/[(1 + N (e)2]. Where, n = the sample size, N = the size of the population, and e = the margin of error of 5% (Yamane, Citation1967). This yielded a sample size of 358. However, 54 households were added to account for attrition, which summed up to 412 as recommended by Fernandez et al. (Citation2009). The sample size of 412 was then proportionally allocated to the study communities using the relation; CP = (HP/N) * n; where CP is community proportion, HP is households in the community, N is the sample frame, and n is the sample size (see, Table ). Proportional allocation of the sample size was done because there were no sharp differences in terms of social and economic characteristics between the communities from which the sample was drawn and the purpose was to describe some shared characteristics of the population (Ahmed et al., Citation2006).

Table 1. Proportional distribution of sample size

The list of households for each community obtained from CHPS zones was assigned numbers after which the research participating households were randomly selected using the fishbowl method without replacement until the apportioned sample was reached. In addition, chiefs, family heads, lead farmers, and leaders of women groups were purposively selected to participate in the study. This is because it was assumed that they possessed in-depth knowledge of urbanisation and its effects on staple food production in the community. Although the study posed no physical or psychological harm to the research participants, verbal informed consent was obtained from the household heads or their representatives, chiefs, and opinion leaders through the Assembly persons for each area. Officials from the Land Use and Spatial Planning Authority (LUSPA) and the Department of Agriculture in the Wa Municipality were also purposively sampled to elicit their perspectives on the issues.

Adhering to ethical protocols in social science research is critical because it helps the research to yield maximum benefits for the society, have clinical and scientific value, be subject to independent review, respect human dignity, and follow the principles of informed consent (Artal & Rubenfeld, Citation2017). Adherence also ensures complete autonomy of the research participants (Stalker et al., Citation2004). In this regard, several steps were taken in compliance with ethical protocols in social science research. Firstly, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cape Coast in Ghana. This was after the data collection instruments were submitted to the Board for consideration and approval. The approval letter was issued to the researcher after some corrections on the instruments were affected. The approval letter was finally issue three months after submission of the instruments to the Institutional Review Board. In addition, the researcher wrote a letter to the Wa Municipal Health Directorate explaining the purpose and objectives of the study to seek permission to collect and use the data on the indigenous households in the sample communities. Furthermore, verbal consent was obtained from each of the research participants to participate in the study, before pictures were taken and interviews conducted. The verbal consent was obtained after the purpose and objectives of the study were explained to them. Finally, the research participants were assured that the data obtained from them would be treated as confidential and anonymous.

3.4. Data collection and analytical procedures

Data were collected using questionnaires and interview guides through interviewing. The questionnaire was used to elicit data from individual research participants. The questionnaire covered issues relating to socio-demographic and economic characteristics, crops cultivated and yields, adaptation strategies, and constraints. Specifically, some of the questions were (1) what staple food crop were you cultivating 10 years ago? (2) What staple food crops do you cultivate now? (3) Why have you stopped cultivating the following crops? (4) Indicate the crop yields of the following crops you cultivated 10 years ago? (5) Indicate the crop yields of the following crop you cultivate now among others. The questionnaires were administrated to the research participants by four hired research assistants after they were educated on the interpretation of the items on the questionnaire and the ethical issues, they needed to adhere to during the data collection. The questionnaires were administered to the research participants in their dialect in either their homes or farms. In addition, 14 interviews were conducted with chiefs (two), family heads (four), lead farmers (4), and leaders of women groups (four) to elicit their perspectives on urbanisation pressures and effects on staple food crop production. The interview participants were recruited based on their status as community influencers, knowledge of the communities, and farming practices. It is important to mention that no new data emerged after the fourteenth participants, accordingly, the interviews were halted. Furthermore, two officials (one from each) from the Land Use and Spatial Planning Authority (LUSPA) and the Department of Agriculture in the Wa Municipality were also interviewed. The interviews covered issues relating to perceptions of urbanisation pressures on land availability and staple food crop farming practices, staple food crops cultivated and the reasons for dropping some crops, and challenges of adapting staple food crop farming to urbanisation pressures. The interviews were tape-recorded with the permission of the participants and each interview lasted between 30 to 45 minutes. Pictures were taken with the aid of a camera to validate participants’ claims.

Prior to the analysis, the data obtained from the household survey were inputted into SPSS version 28 and cleaned. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is used to determine group differences when there are two matched pairs and when data violates the normality assumption required in using parametric procedures in data analysis (Schmidt & Finan, Citation2018). In the case of this study, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used because the data on the quantity of crop harvest violated the normality assumption that is often required for the use of parametric procedures to analyse continuous data. Here, the researcher intended to see if there were significant variations in crop harvests for the years 2011 and 2021. It is worth noting that out of the 412 questionnaires sent out 408 returned relevant data, representing a 99% response rate and as such all the quantitative analysis is based on it. The results were presented in tables and figures. The responses from the interviews were first transcribed and organised into groups based on the major recurring themes after the transcripts were repeatedly read and notes were made in the margins. The results are presented in narratives and direct quotations.

4. Results and discussion

The results and discussion section are presented in four subsections: the socioeconomic profile of the respondents; evidence of urbanisation pressures and staple food crop production nuances; adaptation mechanisms; and constraints encountered by farmers in their quest to adapt food crop production.

4.1. Socioeconomic profiles of respondents

The study revealed that more of the respondents were within the 45 to 54 age range (38.7%) with a large proportion of them (49.8%) having no formal education (). As most of the respondents are mature and aging, their experiences could be deployed to adapt the staple food crop production to urbanisation pressures and to navigate the constraints that may arise in their quest to sustain their livelihood activities. This is because older farmers are likely to possess sufficient experience, techniques, and practices that could be deployed to maximise food crop production under urban change. Moreover, they would be able to fashion out local strategies and actions to surmount the production constraints to sustain their smallholder farming activities under urbanisation pressures. The study showed that a significant majority of the household survey participants were married, which imposes the responsibility to feed their families. With a good number of them attaining basic education, it is expected they could adapt staple food production to urbanisation pressures by employing new technologies and appropriate agronomic practices for sustainable production (Seok, Moon, Kim & Reed, Citation2018).

Table 2. Profile of respondents

4.2. Evidence of urbanisation pressures and effects on staple food crop production

The urbanisation pressures, as observed by the research participants, were declining availability of land for farming and other purposes, decreased natural reserves and an increase in the number of houses and social and economic infrastructure, which together represent the spillover of population and surface area of Wa into the communities. Although all the evidence was considered important, more of the responses cited declining land availability (98%) followed by decreased natural reserves (94.6%) and increased houses as evidence of urbanisation pressures (see, Table ). Interview responses from an official from LUSPA corroborated the findings of the household survey. The official indicated that the physical frontiers of Wa have been expanding over the years, leading to urban encroachment on farmlands in adjoining communities including Nakori, Aahiyuo, Sombo, Bamahu, Danko, Loho, Piisi, Kpongu, and some communities in the Wa-West and Kaleo Nadoli Districts.

Table 3. Evidence of urbanization pressures (N = 408)

As a result of urbanisation pressures, the farm size of all the farmers contacted declined over the study period. In 2011, findings showed that most of the indigenous farmer households (73.9%) had up to 6.07 ha of farmland, while only 17.3% of them had 12 ha of farmland. In 2021, on the other hand, 78% of the indigenous farmer households had up to 6.07 ha, while only 7% of the farmers had up to 12 ha, signalling that more farmers have had their farmlands reduced due to urbanisation pressures. The farmers explained that some parcels of their lands were sold out to private individuals for residential development, which led to a reduction in the amount of land available for food crop production. The findings corroborate the results of a recent study (Abdulai, Ahmed et al., Citation2022) that shows that the built-up area of the city grew from 471.92 ha in 1986 to 4,509.94 ha in 2019. Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2022) similarly report that the city’s population increased from 79,954 in 2010 to 143,358 in 2021. Since the urban core cannot accommodate the growing urban population, residents may perhaps turn to the fringe to acquire more lands to meet their housing and commercial needs. The findings are in line with the works of other research in sub-Saharan Africa cities and in other developing countries that show that urbanisation pressures have led to the reduction of farmlands in peri-urban areas (Coulibaly & Li, Citation2020; Lasisi et al., Citation2017; Paul et al., Citation2021; Willkomm et al., Citation2021), which perhaps affected staple food crop production.

Considering the forgone findings, the researcher sought to find out whether urban pressures had affected staple food crop production in urban Wa. An overwhelming majority (98%) of the respondents mentioned that urban expansion adversely affected food crop production through the dropping of some crops they used to cultivate when they had access to vast arable lands. They furthermore indicated that the phenomena had affected the quantity of harvest of the staple food crops under cultivation. As shown in Table , the higher proportion of the responses cited cultivated all the crops in 2011 even though there were variations. For instance, more of the respondents (89.7%) cultivated cowpea in 2021 but a small fraction of them (6.8%) cultivated it in 2021 and similar results can be observed for sorghum. However, the farmers have stopped cultivating Bambara beans in 2021.

Table 4. Staple food crops cultivated in 2011 and 2021 (N = 408)

Based on the responses, the researcher needed to see whether these developments affected staple food crop production. The study revealed several staple food crops that were cultivated. Generally, all the farmers cultivated cowpea, maize, millet, sorghum, beans, yam, Bambara beans, and rice in the past, while only maize, beans millet, rice, and yam were currently farmed. As shown in Table , the higher proportion of the responses cited cultivated all the crops in 2011, even though there were variations. .

Interviews with chiefs, family heads, lead farmers, and women leaders revealed that the reduction in farmlands contributed to the dropping of some of the crops. According to the farmers, the increase in the number of people in the urban centre coupled with limited space compelled some of the people to turn to the urban fringes areas to acquire farmlands to meet their housing and other needs. In so doing, lands that were used for farming all the staple crops had been used for non-farming purposes, leaving small proportions available for farming. As a result, the farmers could no longer cultivate the entire staple food crop portfolio. A lead farmer from Kompala intimated that:

There was vast land available to everyone in the community and farmers could farm all kinds of food crops for both household consumption and the market. However, urbanisation and the consequent encroachment on former farmlands led to the reduction of land availability and as a result, the farmers had to cultivate few crops on the small portions left (A lead farmer from Kompala, 10 June 2022).

This illustrates that urbanisation does not only affect land available for farming (Afriyie et al., Citation2020; Bonye et al., Citation2021), but it compels the farmers to stop the cultivation of some food crops. This implies that they have to depend on the urban food market and global food supply chain to meet household food requirements (Chihambakwe et al., Citation2018; Olsson et al., Citation2016). In addition, the reduction in farmland sizes because of demand for them (lands) for other purposes implies that the farmers could not benefit from the hitherto large farmlands to produce more food to sell to the growing markets in urban centres, generate more money and improve their well-being and that of their families.

Urbanisation pressures tend to transform surrounding rural areas and food production systems, presenting challenges for staple food production and poverty reduction. This study revealed that urbanisation pressures engendered rapid conversion of fertile agricultural lands in urban fringe areas, affecting farmers’ ability to produce enough food for household consumption and the urban market. Considering the results reported in Table , maize, millet, beans, rice, and yam remained the dominant cultivated crops. The harvest the farmers obtained for the 2011 and 2021 cropping seasons were used to quantify the extent to which urbanisation pressures affected their production (see, Table ). The years 2011 and 2021 were used because previous studies show that 10 years is long enough to measure the effects of urbanisation pressures on urban fringe food production (Afriyie et al., Citation2020; Kuusaana et al., Citation2022; Pauleit et al., Citation2019). In so doing, the crop harvest obtained by the farmers in 2011 and 2021 were compared and the results showed that the median maize harvest obtained by the farmers in 2011 was eight bags (one bag weighed 50 kg) with a related quartile deviation of 4.5, while that of 2021 was three bags with an associated quartile deviation of two. In the case of millet, the median yield obtained was six bags in 2011 with a related quartile deviation of four. The median yield obtained for beans was eight bags in 2011 with a quartile deviation of four. In 2011, the median harvest of rice obtained was four bags with an associated quartile deviation of four bags while a half bag was reported in 2021 as the median with one bag as the quartile deviation. The reduction in crop yields over the period suggests that urbanisation pressures made it difficult for the farmers to cultivate as much as they used to do; and this may affect household food security, the supply to the urban market, and exacerbate the poverty of farmer households (Bonye et al., Citation2021; Weldearegay et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, 2021 recorded more yam harvest than 2011. The plausible explanation for the rise in yam harvest in 2021 could be because the use of chemical fertiliser as a booster to the growth and maturity of the crop and that the decline in farmland size may not necessarily lead to a reduction in farm output.

Table 5. Staple crop yields for 2011 and 2021

Responses from the interviews with the farmers corroborated the finding. It emerged that the farmers had not been able to obtain higher yields as was the case in the past due to the shrinking of their farms and poor soils. The farmers explained that the quantities of yields obtained for the five crops were higher in the 2010s than in the 2020s and they attributed this, in part, to the decline in land available for farming and the deterioration of soil fertility due to continuous farming on the smaller plot of land. A lead farmer lamented that:

Our farms are now smaller in size because parts of them have been given out to private people to construct houses and other structures. This means that we can’t have access to large parcels as we used to in the 2010s and as a result, the yields we get from the crops too have gone down as compared to the quantities we had in the past. In addition, our continuous farming on the same plot of land without fallow period makes the soil lose its fertility and as such affects the quantity of yields of the staple food crops, we obtain these days (Interview with a lead farmer from Danko, 11 June 2022).

An official from the Department of Agriculture likewise stated that:

I can confirm that food crop production has been adversely affected by the rapid conversion of peri-urbans into houses. This is because I have worked with these communities for more than 20 years. Some of the farmers could plant more than 10 ha and harvest more than 100 bags of maize but now the land is not there for them to do that kind of farming (interview with an official from the Department of Agriculture, 20 June 2022).

The narrations indicate that the decline in staple food crop yield could be attributed to the shrinking of farmlands occasioned by the rapid conversion to meet the rising housing demands in the city, which is like the findings of recent studies conducted in Wa and Bolgatanga in Ghana (Bonye et al., Citation2021; Osumanu & Ayamdoo, Citation2022).

Understanding and documenting the extent of the decline of staple food crop production under urbanisation pressures is central to appropriate policy formulation and implementation to boost urban fringe food production and to support rural livelihoods in general. To this end, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to determine the differences in food crop harvest in 2011 and 2021. The results showed that the mean ranks for maize, millet, beans, and rice were higher in 2011 than in 2021. However, that of yam was higher in 2021 than in 2011, signalling an increase in yam harvest. The results revealed significant differences in crop yields obtained by the farmers (with large effect sizes at a 5% alpha level) in 2011 and 2021 for all crops except rice and yam (Table ).

Table 6. Test for differences in food crop harvest in 2011 and 2021

As demonstrated by this study, urban fringe transformation occasioned by urbanisation pressures affect the urban food supply chain through the reduction in the quantity of food crop yields obtained by the farmers (Chen et al., Citation2021). Generally, the farmers reported a decline in the quantity of food supplied to the urban market for all the crops in 2021 although there were variations. As shown in Table , the number of farmers who supplied 1 to 5 bags of maize decreased from 248 in 2011 to 165 in 2021 even though the proportion of farmers was higher in 2021. However, none of the farmers was able to supply more than 10 bags of millet and rice to the market. It was also observed that only a tiny fraction of the farmers (3.1%) was able to supply up to 15 bags of beans to the urban market in 2021. Although the proportion of farmers who supplied up to 100 tubers of yam to the market was higher in 2021 (36.5%), the absolute figures showed that there was a reduction in the quantity supplied to the market.

Table 7. Quantity of staple food supplied to the urban market in 2011 and 2021

The responses from the interviews also showed that the farmers were not able to supply enough quantity of staple food to the market. Why? A family head from Nakori answered the question by saying “we are unable to supply food to meet the high demand in the urban areas due to the drop in harvest obtained in recent times”. A lead farmer from Danko also stated that, “we don’t produce much these days so only a few of us (farmers) are able to send some of the products to the market as much of what we get is consumed at home”. The quotations illustrate that food obtained from farming is no longer sufficient for both farmer households’ consumption and for the urban market, which could provide them with the opportunity to enhance their income and reduce poverty (Pitesky et al., Citation2014). Thus, although demand for local food may exist, local food producers were unable to supply enough to enable them to earn an income and reduce their expenditure on household food consumption (Chihambakwe et al., Citation2018; Crush et al., Citation2011).

4.3. Adapting staple food crop production to urbanisation pressures

The study revealed that urbanisation exerted enormous pressures on food crop production by reducing farmlands and crop yields, but the farmers remain in farming as a critical livelihood activity for their sustenance. Therefore, the researcher needed to know how the urban fringe farmers were adapting their food crop production to urbanisation pressures. Four adaptation mechanisms were identified: intercropping, fertiliser application, multiple farm creation, and sub-division of plots. The dominant adaptation mechanism was intercropping followed by the application of chemical fertiliser to crops as shown in Table . It was also noticed from the results that farmers who fall within the 45 to 54 age bracket used intercropping as an adaptation mechanism followed by those within the 34 to 44 age group. The significance of intercropping as an adaptation strategy to urbanisation pressures lies in its potential to promote sustainable food production (Glaze-Corcoran et al., Citation2020).

Table 8. Cross tabulation of age category and food crop adaptation strategies

Intercropping as an adaptation strategy was adopted because it helps increase food crop productivity, reduces the risk of total crop failure, and helps to control weeds on the fields. In addition, it is eco-friendly and a sustainable way of producing food without the stress on the environment that is associated with chemical fertiliser usage (Glaze-Corcoran et al., Citation2020). Although intercropping is not a novel approach, interviews with chiefs, family heads, lead farmers, and leaders of women groups revealed its adoption has intensified in recent years. The farmers explained that the adoption of the strategy has become necessary because intercropping encourages the farmers to grow multiple crops on the same piece of land and, gives them the opportunity to still grow the crops even though their farm sizes have been consumed by urbanisation. A leader of a women group from Mangu revealed that:

Because of the small size of land available to me to undertake farming, I plant more than one crop on one ha of land. Last year I planted yam, millet and maize on one ha. This year I planted maize and rice on the same piece of land. Part of the land is suitable for rice while the other half was used for maize and groundnuts. This is how we manage with the small plots left for us to do farming (Interview with a women group leader from Mangu, 18 June 2022)

The quotation illustrates that intercropping had become an important adaptation strategy for the farmers as they struggle to adapt food crop farming under urbanisation pressures. The sustainability of food crop production in the urban fringes is critical because it makes healthy local food available in the urban markets at reduced prices and helps urbanites to reconnect with the farms (Chihambakwe et al., Citation2018; Crush et al., Citation2011; Olsson et al., Citation2016). The findings of this study are different from those of Afriyie et al. (Citation2020), who reported that urban fringe farmers resorted to crop diversification, agricultural intensification, and agricultural extensification as adaptation mechanisms to cope with urbanisation pressures in Kumasi.

The continuous cropping of the same piece of land makes it fragile and barren, and unable to support food crop production. Therefore, the farmers resorted to chemical fertiliser to help improve the fertility of the soils to support plant growth and improve crop yields. The study revealed that a significant proportion of the farmers relied on chemical fertiliser to boost crop yield. According to the farmers, the use of chemical fertilisers improves the soil nutrients, namely potassium, nitrogen, sulphur, calcium macronutrients, phosphorus and magnesium, which are critical in supporting crop growth and enhancing yields. A chief revealed that healthy soils are enablers of increased crop yields and healthy food production, and the application of chemical fertilisers helps in this direction. The farmers also depend on isolated patches of undeveloped lands in their communities to continue to be engaged in food production. Although some of the lands have been sold to private developers, other portions were lying idle. The farmers used these isolated patches for food production until such a time that the new owners come to develop them. Furthermore, the farmers subdivided their portions into smaller plots to cultivate different food crops (Figure ). With smaller plots, the farmers were able to cultivate different crops, helping them to judiciously use and manage their lands for enhanced food production.

4.4. Adaptation constraints

It is important to recognize that adaptation of food crop production to urbanisation pressures is not without challenges. This is because when adaptation decisions are made, there may be negative trade-offs (Wiréhn et al., Citation2020). In this respect, the farmers encountered three challenges in their quest to adapt food crop production to urbanisation pressures: the high cost of fertilizers and other inputs; climate variability; and land tenure insecurity. Although the use of chemical fertiliser and other inputs helped the farmers to sustain food crop production, it comes at a cost that most of the farmers struggled to afford. According to the farmers, the prices of fertiliser and other farm inputs have gone up to the extent that most of the farmers could not afford them, further worsening their plight regarding food production. How? A family head from Kpongu answered it,

The use of fertiliser is helping us to continue to engage in food production under urbanisation pressures. However, the prices of fertiliser and other farm inputs are making it difficult to obtain and apply it to our farms. Last year, I bought 25 kg of fertiliser at GH₵ 200.00 but this year it is going for GH₵ 400.00 and I need about four bags to apply to my maize farm. I don’t have that much money and I can say that most of the farmers here would be unable to afford it (Interview with a family head from Kpongu, 12 July 2022).

Apart from the high cost of fertiliser, its continual use contributes to the depletion of soil nutrients. According to the farmers, when chemical fertiliser is applied to the land, it boosts crop yield in the short term, but its continual usage depletes nutrients of the soil. As such, it must be applied to the farm each crop season to maintain soil fertility and that is not a sustainable land management practice.

Food crop production and agriculture practice in the area is rain-fed and as such farmers are vulnerable to variability in climatic elements such as rainfall and temperatures. In this respect, the farmers were confronted with the adverse effects of irregular rainfall and increased drought frequency occasioned by climate change. The unpredictability and irregularity of the rainfall pattern coupled with the increased frequency of drought made it difficult for the farmers to adapt to the shrinking of farmlands observed due to urbanisation pressures. The difficulties arise from the delays in rainfall and the reduction in the amount received in recent times. According to the farmers, when the rainfall season delays, they plant in anticipation of it falling; but in most instances, the crops wither before it rains (see, Figure ), compelling them to remove them to pave way for replanting. The finding agrees with those of previous studies (Finn & Cobbinah, Citation2022; Masipa, Citation2017) in sub-Saharan Africa that the effects of urbanisation and climate change together limit urban fringe food production through the reduction in farm sizes and increased frequency of droughts. The findings suggest that urbanisation pressures and climate variability together adversely affected food crop production in peri-urban areas.

Finally, land tenure insecurity emerged as a constraint to staple food production in the urban fringes. This situation arises because of increased land values, and resultant land grabbing that often accompanies urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa (Van Noorloos & Kloosterboer, Citation2018), making it difficult for smallholder farmers to secure portions for food production. Tenure insecurity arises from the fact that the farmers now rely on isolated patches of undeveloped lands to do farming. However, such lands could be taken away from them at any time the individual or organisation intends to develop it, denying the farmer long-term and exclusive use rights. By so doing, the farmers are disincentivised to exert efforts to till the land and maintain its fertility to produce safe and healthy foods. A family head from Bamahu stated that, “I am not encouraged to invest in the farmland to improve its fertility and to enhance production because the owner can come anytime to develop it” (Interview with a family head from Bamahu, 18 July 2022). The findings suggest that urbanisation pressures undermine farmers’ willingness and ability to adopt sustainable farming and land management practices affecting productivity, which could cascade into food insecurity at household and city levels (Bonye et al., Citation2021; Tittonell et al., Citation2020). However, sustainable food production and sustainable urbanisation are expected to play critical roles in the achievement of SDG 2 promising to alleviate hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture; while SDG 11 seeks to ensure that inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities are built by 2030.

5. Conclusions and policy recommendations

The study set out to examine how urbanisation pressures affected staple food crop production in Wa, Ghana. Specifically, the effects of urbanisation pressures on food crop production, urban food supply, adaptation mechanisms, and adaptation constraints were investigated. Fundamentally, urban fringe communities were experiencing urbanisation pressures that manifested in the reduction of farmlands, disappearance of natural reserves, increased houses, and increased social and economic infrastructure. These developments together contributed to a reduction in farmlands, the cessation of the cultivation of some food crops, and a decline in crop harvest, adversely affecting the quantities supplied to the urban market. To cope with the situation, the farmers resorted to the intensification of intercropping, fertilizer application, cultivating on isolated patchy plots, and sub-division of plots as adaptation mechanisms that helped to sustain food crop farming. However, the implementation of these mechanisms was not without constraints as the farmers had to deal with the high cost of fertiliser, land tenure insecurity, and the adverse effects of climate variability in their quest to sustain food crop production at the fringes of the city. This study has implications not only for Wa, but also for other rapidly urbanising cities in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond. Based on this, the study advocates for the formulation and implementation of a deliberate national-level policy relating to peri-urban agriculture through the promotion of green open spaces, urban organic waste recycling in soils, and staple food crop production. This can be achieved through efforts at the municipal level to make provisions for farmlands and backyard gardens in planning schemes. In so doing, food production can be sustained to create socio-economic benefits including increasing food security and creating employment opportunities, while making sure that the city does not lose valuable food-producing lands. The Municipal Assembly should also liaise with the Food Crop Division of the Department of Agriculture and Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working in the field of agriculture and food security to train farmers on the preparation of organic fertiliser using local materials to boost the production of staple food crops. These together, will, for example, reduce the cost of improving the soil fertility for crop yields while promoting sustainable land management practices that advances the steps towards the attainment of SDG 2 and SDG 11. The limitation of the study is that it relied on recall data to analyse some of the issues because there were no other sources of the required information, and alternative procedures for obtaining household-specific information, such as the quantity of crop harvest. Although efforts were made at guiding respondents to recall accurate figures, there could still be an exaggeration or underestimation. Future studies should focus on how land commercialisation influences climate change adaptation practices of smallholder farmers at the fringes of sub-Saharan African cities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ibrahim Abu Abdulai

Ibrahim Abu Abdulai holds a Ph.D. in Development Studies from the University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast in Ghana. His research interest centers on urban studies with a special focus on urban agriculture. The current study contributes to the wider research interest of the author in urban and peri-urban agriculture. This is because the pursuit of sustainable urbanisation in southern cities have attracted global attention, making this study relevant to our understanding of how urbanization (dis) enables food production at the fringes. The author also researches the areas of climate change and poverty. He teaches development theories at the SD Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Wa in Ghana.

Notes

1. Indigenous household (natives) are those that have always lived in the communities.

References

- Abdulai, I. A., Ahmed, A., & Kuusaana, E. D. (2022). Secondary cities under siege: Examining peri- urbanisation and farmer households’ livelihood diversification practices in Ghana. Heliyon, 8(9), e10540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10540

- Abdulai, I. A., Enu-Kwesi, F., & Agyenim Boateng, J. (2022). Landowners’ willingness to supply agricultural land for conversion into urban uses in peri-urban Ghana. Local Environment, 27(2), 145–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2021.2002288

- Afriyie, K., Abass, K., & Adjei, P. O. W. (2020). Urban sprawl and agricultural livelihood response in peri-urban Ghana. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 12(2), 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1691560

- Ahmed, S., Koenig, M. A., & Stephenson, R. (2006). Effects of domestic violence on perinatal and early-childhood mortality: Evidence from north India. American Journal of Public Health, 96(8), 1423{1428. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066316

- Amoako, C., & Inkoom, D. K. B. (2018). The production of flood vulnerability in Accra, Ghana: Re-thinking flooding and informal urbanisation. Urban Studies, 55(13), 2903–2922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016686526

- Angel, S. (2012). Planet of cities. Puritan Press, Inc.

- Artal, R., & Rubenfeld, S. (2017). Ethical issues in research. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 43, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.12.006

- Awumbila, M. (2017). Drivers of migration and urbanization in Africa: Key trends and issues. International Migration, 7(8). https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_egm_201709_s3_paper-awunbila-final.pdf

- Benis, K., & Ferrão, P. (2017). Potential mitigation of the environmental impacts of food systems through urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA)–a life cycle assessment approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 784–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.176

- Bonye, S. Z., Yenglier Yiridomoh, G., & Derbile, E. K. (2021). Urban expansion and agricultural land use change in Ghana: Implications for peri-urban farmer household food security in Wa Municipality. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 13(2), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2021.1915790

- Bosworth, G., & Bat Finke, H. (2020). Commercial counterurbanisation: A driving force in rural economic development. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(3), 654–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19881173

- Chang, X., DeFries, R. S., Liu, L., & Davis, K. (2018). Understanding dietary and staple food transitions in China from multiple scales. PLoS One, 13(4), e0195775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195775

- Chen, W., Zeng, J., & Li, N. (2021). Change in land-use structure due to urbanisation in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 321, 128986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128986

- Cheru, F. (2005). Globalization and uneven urbanization in Africa: The limits to effective Urban governance in the provision of basic services. Africa Studies Center.

- Chihambakwe, M., Mafongoya, P., & Jiri, O. (2018). Urban and peri-urban agriculture as a pathway to food security: A review mapping the use of food sovereignty. Challenges, 10(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010006

- Cohen, B. (2006). Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technology in Society, 28(1–2), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.10.005

- Coulibaly, B., & Li, S. (2020). Impact of agricultural land loss on rural livelihoods in peri-urban areas: Empirical evidence from Sebougou, Mali. Land, 9(12), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120470

- Crush, J., Hovorka, A., & Tevera, D. (2011). Food security in Southern African cities: The place of urban agriculture. Progress in Development Studies, 11(4), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100402

- Dawadi, S., Shrestha, S., & Giri, R. A. (2021). Mixed-methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. Online Submission, 2(2), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.46809/jpse.v2i2.20

- Diekmann, L. O., Gray, L. C., & Thai, C. L. (2020). More than food: The social benefits of localized urban food systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 534219. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.534219

- Fernandez, R. S., Davidson, P., Griffiths, R., Juergens, C., Stafford, B., & Salamonson, Y. (2009). A pilot randomised controlled trial comparing a health-related lifestyle self-management intervention with standard cardiac rehabilitation following an acute cardiac event: Implications for a larger clinical trial. Australian Critical Care, 22(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2008.10.003

- Finn, B. M., & Cobbinah, P. B. (2022). African urbanisation at the confluence of informality and climate change. Urban Studies, 00420980221098946. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221098946

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2012). 2010 population and housing census - analysis of district data and implications for planning.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2022). 2021 population and housing census: General report volume 3.

- Glaze-Corcoran, S., Hashemi, M., Sadeghpour, A., Jahanzad, E., Afshar, R. K., Liu, X., & Herbert, S. J. (2020). Understanding intercropping to improve agricultural resiliency and environmental sustainability. Advances in Agronomy, 162, 199–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2020.02.004

- Hong, T., Yu, N., Mao, Z., & Zhang, S. (2021). Government-driven urbanisation and its impact on regional economic growth in China. Cities, 117, 103299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103299

- Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., & Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05282260

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Korah, P. I., Nunbogu, A. M., & Akanbang, B. A. A. (2018). Spatio-temporal dynamics and livelihoods transformation in Wa, Ghana. Land Use Policy, 77, 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.05.039

- Kundu, D., & Pandey, A. K. (2020). World urbanisation: Trends and patterns. In Kundu, D., Sietchiping, R., Kinyanjui, M. (eds) Developing national urban policies (pp. 13–49). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3738-7_2

- Kuusaana, E. D., Ayurienga, I., Abdulai, I. A., Eledi Kuusaana, J. A., & Kidido, J. K. (2022). Challenges and sustainability dynamics of urban agriculture in the Savannah ecological zone of Ghana: A study of Bolgatanga municipality. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.797383

- Lasisi, M., Popoola, A., Adediji, A., Adedeji, O., & Babalola, K. (2017). City expansion and agricultural land loss within the peri-urban area of Osun State, Nigeria. Ghana Journal of Geography, 9(3), 132–163. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/gjg/article/view/162544

- Leeson, G. W. (2018). The growth, ageing and urbanisation of our world. Journal of Population Ageing, 11(2), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-018-9225-7

- Masipa, T. (2017). The impact of climate change on food security in South Africa: Current realities and challenges ahead. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v9i1.411

- Muzenda, A. (2022). Southern urbanism: The (non) exceptionality of urbanism in Africa. African Urban Review, 1(2), 1–14. http://africaurban.org/papers/index.php/urbanreview/article/view/1

- Myers, G. (2021). Urbanisation in the global south. In Shackleton, C.M., Cilliers, S.S., Davoren, E., du Toit, M.J. (eds.) Urban ecology in the global south (pp. 27–49). Cities and Nature. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67650-6_2

- Nicodemus, M., Ness, M., & Anderberg, N. (2010). Peri-urban development, livelihood change and household income: A case study of peri-urban Nyahururu, Kenya. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 2(5), 73–83. https://academicjournals.org/JAERD

- OECD/European Commission. (2020). Cities in the world: A new perspective on urbanisation. OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en

- Olsson, E. G. A., Kerselaers, E., Søderkvist Kristensen, L., Primdahl, J., Rogge, E., & Wästfelt, A. (2016). Peri-urban food production and its relation to urban resilience. Sustainability, 8(12), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121340

- Opitz, I., Berges, R., Piorr, A., & Krikser, T. (2016). Contributing to food security in urban areas: Differences between urban agriculture and peri-urban agriculture in the Global North. Agriculture and Human Values, 33(2), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9610-2

- Osumanu, I. K., Akongbangre, J. N., Tuu, G. N., & Owusu-Sekyere, E. (2019, March). From patches of villages to a municipality: Time, space, and expansion of Wa, Ghana. Urban Forum, 30(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-018-9341-8

- Osumanu, I. K., & Ayamdoo, E. A. (2022). Has the growth of cities in Ghana anything to do with reduction in farm size and food production in peri-urban areas? A study of Bolgatanga Municipality. Land Use Policy, 112, 105843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105843

- Pauleit, S., Pribadi, D. O., & Abo El Wafa, H. (2019). Peri-urban agriculture: Lessons learnt from Jakarta and Addis Ababa. Field Actions Science Reports. The Journal of Field Actions, (20), 18–25. https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5624

- Paul, S., Saxena, K. G., Nagendra, H., & Lele, N. (2021). Tracing land use and land cover change in peri-urban Delhi, India, over 1973–2017 period. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 193(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-08841-x

- Peng, X., Chen, X., & Cheng, Y. (2011). Urbanization and its consequences (Vol. 2, pp. 1–16). Eolss Publishers.

- Pitesky, M., Gunasekara, A., Cook, C., & Mitloehner, F. (2014). Adaptation of agricultural and food systems to a changing climate and increasing urbanization. Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports, 1(2), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40518-014-0006-5

- Schmidt, A. F., & Finan, C. (2018). Linear regression and the normality assumption. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 98, 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.006

- Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S., Kalantari, Z., Egidi, G., Gaburova, L., & Salvati, L. (2022). Urbanisation-driven land degradation and socioeconomic challenges in peri-urban areas: Insights from Southern Europe. Ambio, 51(6), 1446–1458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01701-7

- Seok, J. H., Moon, H., Kim, G., & Reed, M. R. (2018). Is aging the important factor for sustainable agricultural development in Korea? Evidence from the relationship between aging and farm technical efficiency. Sustainability, 10(7), 2137. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2018.02.12

- Shorten, A., & Smith, J. (2017). Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evidence-based Nursing, 20(3), 74–75. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102699

- Siegner, A., Sowerwine, J., & Acey, C. (2018). Does ubrna agriculture improve food security? Examing the nexuse between food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: A systematic review. Sustainability, 10(9), 2988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10092988

- Stacey, P. (2018). Urban development and emerging relations of informal property and land-based authority in Accra. Africa, 88(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972017000572

- Stalker, K., Carpenter, J., Connors, C., & Phillips, R. (2004). Ethical issues in social research: Difficulties encountered gaining access to children in hospital for research. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30(4), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00426.x

- Surya, B. Change phenomena of spatial physical in the dynamics of development in urban fringe area. (2016). The Indonesian Journal of Geography, 48(2), 118. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.17631

- Terrell, S. R. (2012). Mixed-methods research methodologies. Qualitative Report, 17(1), 254–280. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1819

- Tittonell, P., Piñeiro, G., Garibaldi, L. A., Dogliotti, S., Olff, H., & Jobbagy, E. G. (2020). Agroecology in large scale farming—A research agenda. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 584605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.584605

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420).

- Van Noorloos, F., & Kloosterboer, M. (2018). Africa’s new cities: The contested future of urbanisation. Urban Studies, 55(6), 1223–1241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017700574

- Weldearegay, S. K., Tefera, M. M., & Feleke, S. T. (2021). Impact of urban expansion to peri-urban smallholder farmers’ poverty in Tigray, North Ethiopia. Heliyon, 7(6), e07303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07303

- Willkomm, M., Follmann, A., & Dannenberg, P. (2021). Between replacement and intensification: Spatiotemporal dynamics of different land use types of urban and peri-urban agriculture under rapid urban growth in Nakuru, Kenya. The Professional Geographer, 73(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2020.1835500