Abstract

In this study, we explore the process of handling challenges and support in a professional Norwegian football team to develop team resilience during daily practice. We followed players and coaches during a season in the top league. The aim was to study how group structures influence coordinated activities and perceived support to players in different roles handling challenging situations, while developing team resilience in professional football. The design of the study is qualitative. Data were constructed through semi-structural interviews with coaches, players, and a leadership group within the team during and after the season. Additional information was provided by an observational log and report from coaching staff meetings. The main finding is that small team units organised as dyadic relations are beneficial to facilitate the balance of challenge and support actions to handle adverse events. However, the use of small dyadic groups also provided the coaching team with challenges on how to orchestrate individual variation with respect to developing team resilience. To facilitate support for all players in various challenging situations became a work in progress during the whole season. There is a need to further explore the use of small groups and coordinative support to develop team resilience, both in professional football and other elite sport contexts.

1. Introduction

Professional football teams face challenges, on and off the pitch, both individually and as a unit. Facilitating the development of player’s skills in team sports, is a subtle and complex issue (Collins, McNamara & McCarthy, Citation2016). Team members pathway into professional sports, is described by Collins et al. (Citation2016) as the rocky road to excellence. The development process is recommended to prepare athletes for handling challenges by building environments, which stimulate for positive evaluation and reflections in a supportive way (Collins & MacNamara, Citation2018).

In such a facilitative environment there is a need to structure the support for athletes handling natural challenges and planned disruptions (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016), functioning as speedbumps in daily practice (Collins et al., Citation2016). It is suggested that a balance of challenge and support (Sanford, Citation1967) in a facilitative environment helps individual and teams to thrive under pressure (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016).

The healthy balance between high challenge and the experience of perceived high support is emphasised (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016; Gucciardi et al., Citation2018) in developing resilience, and coaches has a significant role in the process (Kegelaers, Citation2019). To establish communities of practice (Wenger, Citation1998) where team members thrive and grows on challenges, it is recommended to have a supportive approach, and engage coaches in periodising challenges. Planned structures of challenge and support, allows athletes to learn and grow from interacting in the process (Collins et al., Citation2016). Building on this, Morgan et al. (Citation2017) has presented group structures, described as working communication channels and other conventions that shape norms and values, as essential resilient characteristics of elite sport teams.

In Morgan et al.’s (Citation2017) review, the team’s working communication channels are emphasised to be important for the coordinated actions responding to challenging situations. Their work (Morgan et al., Citation2017) suggests coaches to observe both the communication and coordinated actions during pressured situations in their team, emphasising team members to be ´on the same wavelength` during stressors. To develop deeper understanding of how group structures could enhance the team resilience it is recommended by Morgan et al. (Citation2017) to explore the dynamics of everyday practice of teams.

A season-long study in a semi-professional rugby team, identified key psychosocial strategies that promote the development of team resilience (Morgan et al., Citation2019). In their study Morgan et al. (Citation2019) emphasize members` responsibility for team functioning and (non-verbal and verbal) communication while experiencing challenging situations, as part of the team-regulatory system. The quality of feedback and collective problem-solving, together with the need for team members to be “on the same page” during stressors is highlighted as important elements of the team resilience development (Morgan et al., Citation2019). The need for quality communication is also present in Collins and MacNamara (Citation2018) presentation of talent development, which suggests debriefing to be a key element for mentors handling the bumpy road, while supporting players. Still there is a need to investigate how such support might be organised in a facilitative way for team members to claim ownership and include individual characters and role differences in the development process.

The need to integrate members’ collective qualities and capabilities through interpersonal relations is emphasised in the team resilience development process from several different contexts (Grinde, Citation2021; Gucciardi et al., Citation2018; Kegelaers, Citation2019; Morgan et al., Citation2019). Studies in team sports suggest coaches to set up formal moments for the athletes to reflect after experiencing adversity (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016; Grinde, Citation2021; Kegelaers, Citation2019). It is suggested that athletes should be encouraged to self-reflect on their own strengths, weaknesses, and future working points after both natural and planned disruptions in their work (Collins & MacNamara, Citation2018; Grinde, Citation2021; Kegelaers, Citation2019; Morgan et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). In the context of professional football, the need for role clarity with players and coaches is emphasised (Grinde, Citation2021). Knowing each other as team members by building interaction competence is recognised as an essential part of the team resilience development process (Grinde, Citation2021). Still, there is a need for deeper knowledge of designing group structure, by organise planning, monitoring and debrief of daily practice (Morgan et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

The aim of this study was to explore how group structures influence coordinated activities and perceived support to players in different roles handling challenging situations, while developing team resilience in professional football. There is a need to explore team resilience development processes through longitudinal research (Morgan et al., Citation2019) with different research strategies (Kegelaers, Citation2019), and monitoring cycles of a team`s existence (Morgan et al., Citation2019. There is a need to establish a deeper understanding of how to facilitate the support of team members in handling challenging situations in different contexts (Grinde, Citation2021).

In the context of football, resourceful resilient actions are exemplified by Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018) with a winger skilled in delivering crosses into the box, to be capitalised by the heading capabilities of a striker during situations when the team is one player down. This example of interaction requires individual qualities such as knowledge, skills, and physical capacities which also is emphasised through the need for team members to be connected ´on the same wavelength`, through synchronised actions in specific situations (Grinde, Citation2021; Kegelaers, Citation2019; Morgan et al., Citation2019).

In the emergence of team resilience (Bowers et al., Citation2017), the coordination of individual resources through cognitive, affective, and behavioural activities is emphasised by Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018), both during and in response to adverse events. The foundation of such explicit and implicit coordination needs to be designed, organised, and executed for individuals to be align and create complimentary combinations of human capital resources within a certain team identity (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018). What separates developing collaborative competence in team sport, from a single athlete’s approach, is the need for problem-solving based on relational competence and synchronised coordinated actions.

A player’s solution for handling a challenge is part of the team’s solution that is appropriate in the situation. To adapt and cope through resisting, bouncing back and recovering from adverse events (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018), there is not just one real movement of solution at a certain point of action. It is suggested that the need for resources to minimise, manage and mend challenges (Alliger et al., Citation2015) comes from knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics depending on the situation, type of challenge and perceived support from the environment it occurs (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018). In the context of professional football, Malone (Citation2018) has suggested that small-sized groups with roles interconnected through sub-teams are beneficial to develop shared understanding between players in a team. He confirmed earlier statements of links between experiences, shared understanding, and player predictions, suggesting that dyad experiences are fundamental in developing shared understanding for coordinated decision-making, if the established partnership experiences events together (Malone, Citation2018).

To develop such shared understanding, implies that players should be socially interdependent within different roles. In the process of developing team resilience, Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018) emphasise common expectations, group norms and social support through a shared team identification which contributes to sort out players self-concepts based on distinctions between “we” and “us” vs. “I” and “me” as part of the group structures. The planning for expected adverse events and systematic reflections based on such collective social identity is highlighted (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018), without suggesting how different group structures could facilitate such development processes.

To explore player dynamics with the environment in developing team resilience, insights could be found in the work of Rothwell et al. (Citation2020) who discussed implications for sport practitioners. Investigating the athlete–environment relationship, Rothwell et al. (Citation2020) claim that the strength of the functional relationships between individuals and the environment is influenced by everyday behaviours, values, and customs (sociocultural practises) within a sport’s specific environment. They emphasise affordances in designing high-quality learning and development experiences, suggesting that practitioners and applied scientists design learning environments consisting of value (affordance) and meaning (information) for the learners (Rothwell et al., Citation2020).

Group structures which facilitate important coordinated activities for handling context-specific challenges through relational affective and cognitive protection processes involving interdependent individuals, have yet to be explored within a Norwegian professional football team. These processes might be underpinned by established knowledge of team collaboration dynamics across contexts and different development domains. Conducting such practitioner research on coordinated activities is beneficial across educational and sport contexts (Casey et al., Citation2018). This study investigates how coaches organise practice to solve difficult and challenging situations by facilitate player support through different group structures within a Norwegian professional football team (Eliteserien). The research follows a shared leadership group, players, and coaches in their attempt to strengthen the team as a unit during a season. The work is guided by the research question:

How can group structures facilitate interaction between individuals to support the handling of challenging on-pitch situations to develop team resilience?

2. Method

The study explored different individual experiences of handling challenges through organised activities in a Norwegian football team. Data were gathered by following developmental and performance processes in the team during a season in the top league (Eliteserien). The research was following an action-research approach to reflect and improve own practice within the team, as part of a shared initiative to facilitate the development of team resilience (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, Citation2013). The first author was a member of the coaching staff.

This work is aligned with McNiff’s (Citation2010) suggestions on self-reflective practice. A qualitative study was designed to improve practice by changing it from within. Small deliberate changes in the organised coaching were utilised to improve daily practice through self-reflection (Casey et al., Citation2018). Data were collected from different sources (Flick, Citation2009) and systematically compared (Charmaz, Citation2014)

2.1. Design

The development process started off by coaches structuring activities aimed at challenging individuals in roles to operationalise recovery actions in transition phases of the play and counter play. Shared leadership in the team helped develop baseline constructs of values and collective norms of behaviour within the team.

To gradually involve players, support was facilitated through coaching on positioning play, role development and choices made by different team units, and the whole team as a collective. Training activities were developed for the players’ and team unit’s ability to handle challenging situations, utilising debriefing set-ups by small-sized group meetings before and after training sessions during the season. The activities were diversified in pre-, during- and post-training actions for the ability to handle challenges individually and as a team.

First, cognitive and emotional walk-throughs were conducted individually with players to be prepared and “Match ready” able to restructure thoughts, emotions and behaviours in and after difficult situations. Both individual and collective baseline readiness was central in operationalising problem-solving actions and behavioural responses to challenging situations. Developed through cognitive, affective and behavioural patterns to prepare players’ different roles, it enabled them to handle forthcoming challenges through recovery actions.

Collective readiness was worked on through two main organisational approaches. First, to initiate and claim ownership, a shared leadership group developed core values and shared expectations within the team. It was done by involving small units of strikers, midfielders and defenders in establishing accepted interactional behavioural standards.

Second, during pre-season, different aspects of emergency preparedness work were discussed and rehearsed to become part of the team’s automatic response integrated as the values, norms and activities through the team’s internal expectations and behaviours. The operationalised outcome of team resiliency was to activate positive behaviours with each player faced with both individual and collective challenges in his role. To establish automatic runs and responses together with the coordination of shared understanding, acting on situational cues, were prioritised activities.

It was exemplified with specific runs to close spaces defensively with recovery actions to be achieved and celebrated during training and in pre-season matches. Offensively, coordinated actions were rehearsed to resist, bounce back and recover from situations with the potential to be outnumbered or defeated at stages in the matches or during the season.

To capitalise on the established baseline standards, team unit group meetings were held to clarify and discuss behavioural actions based on shared experiences and analyse video clips from matches and training against a referential opponent at the initial start-up of the season. This way of working was refined throughout the season. In addition to regular debriefing meetings with the whole group, various group meetings were utilised during the season to work on problem-solving challenges before and after matches.

During the season, this was exemplified with small-sized groups down to dyads collaborating with coaches planning and debriefing handling difficult interactional situations for the team. Experienced and future on-pitch behaviours were discussed and visualised being able to adjust runs, movements and interactional elements that restructured and reorganised recovery of the team in the transition phases of the team’s play. Discussions were framed by leadership guidelines.

During the season, both coaches and players picked challenging situations for problem solving. Meetings with different group sizes were run by coaching staff or by players with support from the coaching staff. The frequency and format (e.g., who, when and what) of the meetings followed the performance needs of the team during the season.

2.2. Data collection

Information from individuals experiencing different systemised activities was gathered through interviews and observation (Flick, Citation2009). Semi-structured interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009) with two coaches (C1 and C2), eight players (pp. 1–8) and a shared leadership group of two players (SLG P1 and P2) were conducted. The shared leadership group was interviewed three times during the season at the start-up of pre-season to design activities within the group. Two evaluation meetings, one in the middle of the season and one in the end of the season were also held.

Players were selected according to different backgrounds, role within the team and differences of age (20 > 35 years). Some players were members of the Norwegian under-21 national team, and for this reason were also observed and interviewed in this context outside their daily environment to address experiences across development contexts. The two coaches were selected as informants because they were responsible for planning and carrying out practice, both on and off the pitch.

The individual experiences represented a diversity of challenges within different roles in the team during the season, which revealed reflections from different viewpoints. Players’ and coaches’ interviews were conducted one time with each team member during the second half of the season. One of the coaches, (C2), was interviewed a second time after the season, asked to reflect and evaluate how he experienced the season as a member of the coaching staff, and as a critical friend to the first author who was managing the process.

The informants were asked to reflect on challenging experiences as individuals on the team. The eleven individual and three group interviews were based on the same interview guidelines, piloted and designed to explore informants’ individual perception as participants in team activities. Pilot questions were explored through interviewing one coach and one player within the club. Reflections on these interviews created an awareness of the power balance and need for mutual trust. Elite athletes are used to being interviewed and might pre-phrase prepared answers with personal meaning while talking publicly. The interviewer needed the ability to go beyond these pre-constructed phrases (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). Trusting the interviewer is crucial for the informants’ connection with experiences and core reflections as participants in the real-time activities. To achieve this, protecting the anonymity of the informants, who are nationally and to a certain degree internationally known players and coaches, was important.

Questions were tailored to address everyone within their role to reveal elements of experiences from different relational processes. Asking open-ended questions in the beginning of the interviews made the informants take the lead by talking about concrete cases. Follow-up questions were explored when needed. It made the informants reflect on actions, behaviours and perceived support in handling challenges connected to the different roles within the team. All 14 interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

2.3. Researcher’s role

Complementary information for the interviews was gathered through the researcher’s role as an observing participant (Cohen et al., Citation2011). A research log, written as a daily diary of observational notes including reflections, and reports of 10 coaching staff meetings supplemented the interviews.

The researcher was hired as part of the coaching staff more than a year before starting the fieldwork. In this participant role, relationships were established with players and other coaches. The main responsibility during the season was to help players establish a cognitive, emotional, and behavioural baseline so they could handle challenges. He was also responsible for helping coaching staff interact with players through planning, acting, and debriefing activities to strengthen the team as a unit for handling challenging situations. As part of the shared leadership group, the researcher helped facilitate internal interaction processes within the team.

The combined role made continuous in-depth study possible, but as an engaged participant of the development process, observational limitations occurred as well. The risk of selective attention, memory or data entry was present (Cohen et al., Citation2011). However, the role of nurturing the individual development of both coaches and players within the team made it possible to approach cases from different perspectives.

The written log, team meeting reports, and interviews of coaches, players and the shared leadership group gave access to information from different viewpoints and processing stages. This made it possible to explore different individual experiences of the organised activities.

2.4. Data analysis

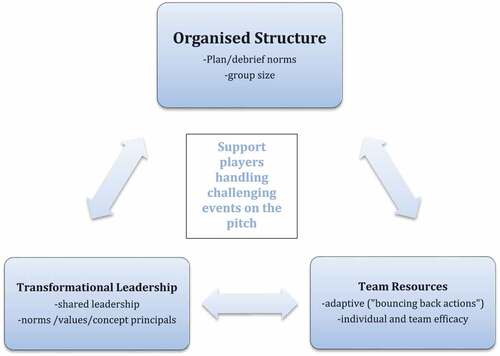

Interviews with the shared leadership group, coaches and players were coded line by line, before information was structured in categories as recommended by Charmaz (Citation2014). The three tentative categories, organised structure, team leadership and team resources suggested to underpin team resilience development (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018; Morgan et al., Citation2017) were explored by information from interviews and observations through research and coach meeting logs.

The research question on how to organise the practice of solving challenging situations, with players in different roles, founded the analyses to look for group structures and resource elements in the experiences of team members participating in this study. Organisational structure was therefore chosen as a core category and facilitative elements of problem-solving activities were analysed through the two other categories, in line with the suggestions of Fejes and Thornberg (Citation2015). Following Flick (Citation2009), participant observation is adopted to include interviewing, document analysis, and introspection along visual and direct observation.

Information from players’ experiences were supplemented with written leadership statements, decisions noted in the logs and observations of the developmental process. This gave access to the experiences of several individuals and a broad picture of the explored journey. In line with Cohen et al.’s (Citation2011) claims of strengthened validity, the data processing, thick descriptions, theorising codes, and peer debriefings with fellow researchers made it possible to connect and investigate the three categories in the analysis. Studying the organised process from the experiences of both players and coaches made it possible to nuance the different responses to challenges, support and problem-solving activities found in the diverse sources of information.

2.5. Ethics

Prior to the study, members were informed of the project and the researcher’s mixed role, and informed consent was given. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD).

Gaining and earning trust before, during, and after the interviews was a crucial part of the data collection process. As a member of the team, coaching both players and members of the coaching staff, the researcher had to find a balance of informational flow to operate in a credible way. To achieve this, it was expected of him not to engage in picking the team for a match, or in other comparing of judgmental decision-making, which he complied with while executing his role within the environment. It was made ethical considerations throughout the whole process, in the utilisation of individuals information sharing, with the intention to protect team members participating in the study (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009).

3. Results

The aim of this study was to explore how group structures influence coordinated activities and perceived support experienced by players in different roles handling challenging situations, while developing team resilience in professional football. The question asked was how group structures can facilitate interaction between individuals to support the handling of on-pitch challenges to develop team resilience. Three categories—organised structure, leadership, and resources—are explored through information from the participants’ experiences because they capture facilitative elements which underpin the coordinated development activities within the team during the season. Examples from the three categories are presented, discussed, and reflected upon, aiming to provide a better understanding of the processes and conditions that underpin and strengthen the development of team resilience.

3.1. Organised structure

To facilitate development processes, team meetings were held to both plan and debrief collective performance in challenging situations during training and matches. To problem solve difficult situations, video-analysed situations from training and matches were reflected upon and discussed. Players in different small-sized groups were expected to problem-solve challenging situations within a supportive atmosphere to find solutions as part of the responsibilities of their role on the pitch.

It was conducted by having both players and coaching staff select cases of challenging situations from different phases of play that needed to be problem-solved. The deliberate use of differently sized groups during a week’s practice contributed to the process by building interpersonal connections and influencing potential coordinated relationships between roles in the team. The shared leadership group reflected upon the use of different organised structures and the various engagement of players in relation to group size:

In my experience, we are perhaps more daring in small-sized groups. With video analysis, players give more of themselves. In bigger group settings, few contribute their opinions and dare to give something of themselves. This is where we need to improve the most, I feel (STLGP1).

As we see, bigger groups might result in less engagement from the players than in smaller groups. Thus, the use of small unit team meetings increased. A coach who worked together with players in planning, monitoring, and reflecting on team performance in training and during matches, elaborates:

I believe in challenge within the concept of play. To bring players in and talk with them is good. I asked a player if it’s too much to sit down before every match in divided groups one day, with the whole team another day and then again in groups on match day. He disagreed with this and replied that this was the key. Claiming the match analysis and having meetings in the video lab might be the reason we lifted ourselves (C1).

The coach emphasised the need to challenge players in group meetings of various compositions. But he stressed that there is a balance. It might be too much of it. The player mentioned above confirmed in a later interview that both common understanding between players and coaches and performing as a unit did increase due to the different group meetings. This suggests that utilising small-sized team meetings might be a key in building a stronger team.

Working on challenges in small groups, both on and off the pitch, seems to blend individual perspectives into the team’s bigger picture of “we”- narratives helping players to connect “on the same wavelength”. Reflecting on this, both coaches and some players gave a description of individual skills as part of the identified team skills necessary for facing the team’s challenges. A player focused on his role in the team reflecting on the challenges he experienced in the team’s development:

I was definitely challenged, since with the team set-up and organisation, I was supposed to run a lot, and extremely fast. The challenge was to be good when receiving the ball and to act calmly when finishing on opponents’ goal. I suppose that being on the alert the whole time and making the right decisions without burning too much energy, being able to score goals and use offensive skills was probably the hardest. I felt you challenged me, and everything was a bit new for me and when I sat down reflecting on the season, I was rather proud of the fact that I felt able to switch and restart in front of every match (P7).

The player highlights challenges coming from both the concept of play and coaching staff that he needed to handle contributing to the team’s performance. Another player expressed his role on the team from a development perspective:

I have developed my role individually and with the others on the pitch. I feel I know more about what x, y and z like to do, how they want to relate to situations. I know them better when it comes to what I want to do and when we get to a certain level, it’s going to happen automatically (P5).

The way to structure practice on the pitch and debriefing meetings off the pitch in small-sized groups down to dyads of players in different roles contributed to problem-solving difficult situations for the team. As one player described it:

I remember sitting down with [coach x] for an hour going through thoroughly how to approach the next game. We did well and from there we did the same and the team responded so well at getting better and better. I feel we did improve every step of the way and the analyses with meetings we had was absolutely crucial for the collaboration and coordination of the team (P7).

Individual and collective resources were nurtured in small groups during the development of interaction in handling collective challenges. As one player emphasised: the process showed the small team unit develop step by step, we didn’t skip stages and were very thorough through discussions and constructive dialogues(P5). The origins of the resources came from context-specific characteristics, knowledge and capabilities which seem to be facilitated and structured through the mechanisms of challenge and support in small-sized groups. Experiences of both players and coaches regarding organised structures suggest the use of small-sized groups to strengthen both the subunits and overall team as a group.

To benefit from resources, complementary individual actions are needed, and multiple successful combinations are determined by how suited or adapted available resources are with the challenging situation. For this it seems beneficial for the organised structure in a team also to have a progressive build-up of potential challenges, and progression of group sizes in the development process. Starting off by structuring small-sized groups in dyads, building strong relational links between collaborative roles, and then moving the coordinative activities forward, was found to be useful in the teams´ development process.

3.2. Team resources

To nurture and enhance needed resources when teams are faced with challenges, it is important to problem-solve through individual experiences and collaborative coordinated actions. Developing adaptive changes of behaviours through reflections, discussions and automatic responses between different sub-units seems essential. The path to these resources is diverse.

The individual and collective resources utilised in the challenging situations described in this study come from the experiences of coaches, players and logged observations during the season. Players’ reflections show how responses to challenging situations are developed through the process:

In the beginning, when I came, there were some games where I felt I was struggling a little bit. When I lost the ball, I bowed my head, but I think, like you told me at the meetings, I changed my body language. Then I see every time I changed my attitude after a bad situation, I had a good situation after that. And I think every time I changed, I saw results, and I saw good results (P1).

The player described a typical situation of play and counter play, for him exemplified by avoiding losing the ball in critical stages of his play. This became a point of reference for his actions (goal setting/achievement process) that was about how to bounce back and recover through cognitive, affective and behavioural change. Through these situations, by changing his attitude in his role of play, he gradually became a leader both on and off the pitch. Thus, it exemplifies how, by changing attitudes, individuals contribute available personal resources to the team.

Working as a group, it is important to identify and anticipate triggers of challenging situations. As a response to these challenges, activities were related to the player’s role and the need to coordinate resources and synchronise actions to optimise the team’s performance. One player described his learning experience on how to handle challenging situations as part of the team unit:

At the beginning you must think a little, yes maybe z likes to push a little more than y outside the line, then I have to be a bit more observant behind z. In the beginning you’re thinking about it but eventually it just happens automatically depending on who you play with. So, I feel we’ve had a good development of just that bit (P4).

To synchronise common experiences through debriefing reflections, stimulating and adjusting coordinated activities within the team unit seemed to have an impact on how the player performed his role within the team in different challenging situations. The availability of resources was facilitated through the organised practice of systemised reflections in small-sized groups.

Dialogues and discussions among the players together with coaches developed shared expectations through team norms and guiding principles. This collaboration was recognised as a resource described by one player reflecting on the importance of team unit meetings:

I think it is really important to have this kind of meeting because then we know when we shout. For example, when I shout to [player x] or [y] they know I am shouting because we have talked about something before, so just make them alert, then they know I’m not mad, just want to be the one who wakes them up, if you understand? (P6).

Small-sized group meetings facilitated cognitive, affective and behavioural coordination, and adjustments of the individuals within their role in small team units and the group as a whole unit. Group meetings found different resources rooted within experiences of developing individual and collective efficacy in handling challenging situations:

I feel we took steps all the way and the analyses we had and the meetings we had were absolutely crucial. I feel like getting the interaction we had and the enormous running capacity and the punch we had in almost every match (P7).

The resources also seemed to develop in stages during the season as one player described an emergent feeling of being part of a subunit of the team:

I feel we were a strong unit within the team. If you look at pre-season training, I felt we often had good control when being challenged during practice. We succeeded in the exercises and developed well. I think it showed during first half of the season; the effort and the work paid off (P4).

This shows possibilities to develop collective resources within small subunits in the team. Structured planning and organised practice, followed by debriefing meetings with small-sized subunits, seems to be beneficial in building a shared belief in the team. But it also presupposes organised structures to be able to build the collective and coordinated resources necessary to strengthen the unit. In order for this to be a process of transformational leadership, principles and guidelines seem to be needed from the coaches.

3.3. Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership was intentionally planned for applying activities which framed coaches and players to challenge each other within the team. One organisational approach was the use of a shared team leadership group (STLG) to map the players’ view on what they believed should characterise the team and narrow down a set of core values. The group expected players to challenge and support each other, expressed in an early interview with the STLG:

Everybody needs to be responsible and professional on and off the pitch. It is best when many players challenge each other. If it’s just STLGP1 and I shouting all the time, it never will have the same influence (STLGP2).

The values and norms were injected in the group through shared leadership processes to build a supportive atmosphere in the group and challenge each other within the team. These elements were shown in one player’s comparison with the previous season:

I would always compare from last year to this year and it’s about pushing, you know. This year it was more intensive. For myself, there were more people around me talking to me. It makes me feel good when people talk to me like this. They give me more confidence and I grow (P6).

This player compared actions before and after the season’s organised activities. One coach, when asked to reflect on the development process, made similar suggestions:

We emphasised practice on the pitch, and I firmly believe the players experienced being challenged and pushed more compared with last season. This was our aim both physically speaking and through the complexity of practice, which also challenged us as coaches when it came to the implementation. Regarding complexity, I think this challenged both players and coaches. Even though things might have been a bit bumpy with bad feelings during the week, it made us think, which we felt paid off during the match at the weekend (C2).

It shows that the organised structures to nurture coordinated resources was pushing both the players and the coaching staff in the process, which asked for leadership guidelines and a need to establish team norms for daily practice and relational cooperation. This aligns with reflections on the challenges, where experiences in quality and density of support varied from different individuals, both players and coaches.

I think we managed to create good habits on the pitch and have a good coaching template. This said, there is room for improvement when following players more closely, for instance, in the gym or after practice. I feel we started off well during pre-season, pinpointing players to be followed, but when the matches started this faded away a little bit and the matches became the focus of feedback. It seemed difficult, but one thought was to follow, once a week during practice, those players with less playing time during a match (C2).

Transformational leadership intentions influenced the team’s path of development through expectations of ownership within roles, increased challenges and support. Both on and off the pitch, different types of challenges and support involved players and coaches in coordinating activities throughout the season. Nevertheless, there were players who experienced the activities as unresourceful:

I know [T] is there all the time for me if I need something. What annoys me is the follow-up players get of matches several times a week at analysis sessions. Then I struggle to know how to motivate myself because I feel that it doesn’t matter what I do, and it has nothing to say (P2).

Players also experienced a lack of motivation connected to the perception of mistrust and less regular playing time in matches as revealed in player’s interviews, with some players also working their way out of it:

It was rough the first matches when I didn’t play. When I get challenged and see something specific I could do better, which is important, as I see in some way that there may be an entry to get into the team, maybe I will work on that then (P3).

Different needs, social support and the experience of perceived support may fluctuate over time, and follow-up procedures for support is beneficial as long as they meet the needs of both the player and the team values and norms, shown in a player’s reflections:

I like to be challenged and get feedback on things I can do even better. I feel that I put so much effort in it so it’s okay to get, yes really everything I do, so I like to get feedback, I really like it. The two main focus areas where I have received feedback have actually been in accordance with what we have been working on. And I really did work and feel that it shows in my game (P3).

These different and contradictive experiences regarding group structures and organisational elements make discussions important to reflect on facilitating developmental processes. Evaluations at the end of the season emphasised difficulties to coordinate and differentiate player support. Leadership was recognised to be improved, developing the whole group as a unit and structuring players’ challenges and support through shared experiences.

4. Discussion

To utilise organised structure in the team-improving practice of how players are supported handling on-pitch challenges, this study presents experiences of organisational structures, connected to team resources and transformational leadership elements. Small-size group activities handling adverse events coordinated within the team’s actions are explored in line with suggestions of building a facilitative environment (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016) and developing task-specific resources needed for certain challenging situations in different player roles (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018).

In the study, challenging situations were shared and handled by players and coaches through briefings, on-pitch coordinated actions and debriefing settings, which is in line with earlier findings, found to support the development process of team resilience (Collins & MacNamara, Citation2018; Grinde, Citation2021; Kegelaers, Citation2019; Morgan et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Especially did the small-sized group activities facilitate important role clarity (Grinde, Citation2021) and between players and coaches and players contributing to develop coordinated automatic respond in challenging situations. The experiences in this study are in line with suggestions coming from Kegelaers (Citation2019), indicating debriefs are crucial to engage metacognitive processes for learning and self-awerness in concrete situations. This study shows that adjustments coming from debriefs in small groups helped small units to improve their coordinated interaction handling future challenging situations for the team.

Small-sized group activities pushed the team’s performance limits in taking new steps and developed reintegration and recovery possibilities in challenging situations to be able to minimise, manage and mend challenges in line with Alliger et al.’s (Citation2015) suggestions. It was based on cognitive, affective and behavioural modifications as suggested by Bowers et al. (Citation2017). Both unanticipated and anticipated adverse events represent opportunities to learn and develop positive adaptations as members of a team (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018). The results, in this study, show there is a positive connection between a small-sized group of organised structures, transformational leadership and team resources handling challenging situations for the whole group while developing team resilience.

Experiences of team members in this study seem to be in line with Malone’s (Citation2018) findings of utilising player dyads to develop coordinated decisions, suggesting that players experiencing situations together, are more likely to predict each other’s actions, and act on certain scenarios based on this knowledge. Organised activities in dyads increased a common engagement, ownership and responsibility (Morgan et al., Citation2019) and contributed to problem-solve challenging situations by constructing resources in briefing, action and debriefing settings (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018). A player’s reflection exemplifies this by signalling that he started to anticipate and adjust his own behaviour based on how he learned to know his teammates’ responses in different critical situations, when working on the limits within the team unit. This experience is in line with Morgan et al.’s (Citation2017) suggestions of improving performance through developing team resilience by utilising group structure elements in the team.

The organised structure in dyads seems beneficial as a starting point to develop and achieve progress in significant task-specific and relational knowledge necessary to problem-solve challenging situations—although negative elements regarding this structure might also be taken into consideration. One player reflected on, did present a lack of motivation and a feeling of mistrust by missing out on participating in some of the coach constructed dyads, established during the season. The experience of the player confirms the need for quality in communication as presented by Collins and MacNamara (Citation2018). It also shows the need for coaches to establish differentiated support (Kegelaers, Citation2019) for players to perceive support in a way that makes value (affordance) and meaning (information) for the learning process, as suggested by Rothwell et al. (Citation2020).

While reflecting on activities, the leadership group and player interviews also revealed some risk elements contradicting the cultivating of a strong team identity and selfless culture recommended by Morgan et al. (Citation2019) to be vital in the team resilience development process. In the debrief of the leadership group there was suggested to adjust some of the small-sized group meetings into different stratifications, which is in line with the suggestions coming from Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018), of utilising diverse strengths in the team. To be able to embed these group constructs as part of the environmental context with value (affordance) and meaning (information; Rothwell et al., Citation2020), there are several voices to be heard within the players’ context. All this needs to be taken into consideration in the leadership processes.

Following these suggestions, interactional player links within a team’s divided unit need to be supplemented with strong links between different team units, through task-specific knowledge-handling challenging situations. For this, we suggest there is a need for several links to become a stronger team overall. Not just a winger’s complementary relationship to a striker scoring a goal with one man down as exemplified by Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018).

According to the leadership group in this study, coaches need to facilitate different aspects of the play nurturing complementary player links, both to strengthen the team when facing challenges in matches, and challenging situations on and off the pitch as a group for the whole season. This is in line with similar suggestions from

Rothwell et al. (Citation2020) that functional relationships depend on the sociocultural practice within the environment. As Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018) recommend, the diversity within a group needs to be recognised and utilised as a resource and contribution to team dynamic processes. One player in the shared leadership group reflected on the group structures regarding the organised constellations, suggesting that the coaches need to be held accountable to set up different group structures. Which is in line with the responsibilities for the coach to enhance the interactional qualities between player and coach (Kegelaers, Citation2019) in the resilience development process.

This study also reveals some weaknesses regarding structures in the support of players. To organise player dyads in planning and debriefing settings by constructing small links and coordinated actions seems beneficial. But it also excludes players from contribution and diverse experiences of perceived support. To achieve this balancing act in the future, the organisation of developing team-regulatory systems based on ownership and responsibility as suggested by Morgan et al. (Citation2019) might be beneficial. To explore this further the organisation of a shared leadership group, as suggested in this study, could be utilised in future studies.

This aligns with suggestions from Gucciardi et al. (Citation2018) to arrange coordination of resources in complex dynamic systems to foster timing and interdependent task execution of common goals through behavioural, cognitive, and affective mechanisms. They claim different resources are not complementary without goal-directed activities interacted between individuals and their environment, suggesting multiple successful combinations of individual resources influence the development of team resilience. It also shows the need to emphasise communication quality (Morgan et al., Citation2019) in coordinating player links and the player-coach relationships to strengthen the team as “a unit” for handling challenging situations. This recognises the coordination of members as beneficial, and there is a need for interactional competence in the team resilience development process (Grinde, Citation2021). As one player reflected: It’s demanding, and you have to know each other to get it right.

To help facilitate such task-specific and relational knowledge between team members, this study suggests utilising plan and debriefing meetings through the organised structure of small-sized groups building support for players handling on-pitch challenges while developing team resilience in practice. It is presented by the three interconnecting categories of organised structure influencing transformational leadership and team resources in practice (Figure ).

5. Implications and future research

The results presented are connected to individual reflections of challenges, support, and progress of the team, coming from team members participating in the development process. It is a context-specific study, investigated through selected players and coaches. Because of this, results might not automatically be transferable to other teams in professional football. Still, context-specific investigations which study process mechanisms are utilised across different domains to share knowledge and are beneficial to generate deeper understanding of team resilience development process. This study shows insights into organising how to develop practice in handling challenging situations and developing team resilience in elite football environments.

For this kind of interpersonal investigations, the first author’s mixed role in the activities, his experience as a practitioner and member of the coaching staff should be taken into consideration. There is a risk involved in the process of research to favour certain perspectives in the material even though the purpose of the project was to facilitate the development of both players and coaches within the team. The research might as well be enriched by first-hand information from perceptions while exploring the process with years of experience working with interactions within the context-specific environment.

Reflections and suggestions coming from participants on how to utilise player dyads in the development processes should be addressed and implemented in future work. To further explore consequences of organising players in developing team resilience might be beneficial for progression and process knowledge. The construct and development of team resilience is temporal (Gucciardi et al., Citation2018), and the emergent process seems essential in every team.

This study shows how group structures in the team could facilitate the need for balancing challenge and support in the team resilience development which is in line with former suggestions of Fletcher and Sarkar (Citation2016) and Morgan et al. (Citation2019). The process of building resistance, bouncing back mechanisms and recovery patterns in a team depends on players experiencing the right amount, and quality of perceived support. To stabilise such processes in a team, entails continuous work utilising qualities in group structure in daily practice. Coaches’ reflections aligned during the season with Casey et al.’s (Citation2018) suggestions of the need to coordinate both players’ and coaches’ resources to face the demands in different challenging situations. To develop team resilience, it is necessary to plan and execute coordinated player support differentiated to handle challenges across roles and situations based on the knowledge of the individuals (Grinde, Citation2021). The implementation of resources to handle these complex individual and collective processes is a leadership challenge which needs to be supported and nurtured through ownership and reflexive learning, facilitated by group structure elements shown in this study.

The mixture of small-sized group meetings and different interdependent individual roles of the team resilience development process should be further studied to understand strengths and weaknesses in the development process. There is a need to explore how group structures facilitate interaction between individuals to support the handling of challenges which occur in the daily environment outside the pitch in professional football. Further understanding of these complex and sometimes contradicting processes requires first-hand information provided in high-performance environments. To explore such process mechanisms future long-term context-specific investigations are needed.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore how group structures influence coordinated activities and perceived support to players in different roles handling challenging situations, while developing team resilience in professional football.

The organisational constructs of small-sized and shared leadership groups contribute to the challenge and support processes of developing team resources to problem-solve difficult situations. It underpins coordinated behavioural actions between interdependent players, which are needed in the development processes. The suggestion from this study is to start small in the development process by utilising dyads constructing small unit links, and progress by incorporating various diverse constellations. Small-interconnected links provide strong chains over time. Reflections coming from players and coaches suggest that these organisational group structures have positive influence on team resilience development and team performance.

The need for coordinative support between players and coaches is recognised, while room for improvement is shown in the evaluation of the activities of the team at the end of the season with suggestions of a more coordinated, organised group structure to facilitate the diverse needs of player support to handle challenging situations. Further understanding of team development processes requires first-hand information provided in high-performance environments. There is a need to explore the benefits of utilising small-group structure in differentiated support of handling challenging situations in different elite sport contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ole Erik Grinde

Ole Erik Grinde is a research fellow at PhD. program in Educational Science, NTNU. He works as a mental coach in Norwegian top football. Grinde has a background as a teacher and teacher educator and has for several years worked with individual and team for the development of performance mentality.

Vegard Fusche Moe

Vegard Fusche Moe, associate professor in sports at the Department of Sport, Diet and Natural Sciences, Høgskulen in Western Norway (HVL). He is a research program leader at the faculty for teacher education, culture and sports. Moe do research on man in motion in contexts such as sports and school. Working for the most time with sports philosophy, practice-related knowledge development in football and understanding of bodily learning in the school.

References

- Alliger, G. M., Cerasoli, C. P., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Vessey, W. B. (2015). Team resilience: How teams flourish under pressure. Organizational Dynamics, 44(3), 176–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2015.05.003

- Bowers, C., Kreutzer, C., Cannon-Bowers, J., & Lamb, J. (2017). Team resilience as a second-order emergent state: A theoretical model and research directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01360

- Casey, A., Fletcher, T., Schaefer, L., & Gleddie, D. (2018). Conducting practitioner research in education and youth sport. Reflecting on practice. Routledge.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd) ed.). SAGE.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th) ed.). Routledge.

- Collins, D., & MacNamara. (2018). Talent Development. A practitioner Guide. Routledge.

- Collins, D., MacNamara, A., & McCarthy, N. (2016). Putting the bumps in the rocky road: Optimizing the pathway to excellence. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1482. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01482

- Fejes, A., & Thornberg, R. (Ed.). (2015). Handbok i kvalitativ analys. Liber.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(3), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

- Flick, U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research (4th) ed.). Sage.

- Grinde, O. E. (2021). Bridge over troubled water: Shared understanding bridges individual and collective resources in developing team resilience in professional football. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.705945

- Gucciardi, D. F., Crane, M., Ntoumanis, N., Parker, S. K., Thøgersen‐Ntoumani, C., Ducker, K. J., Peeling, P., Chapman, M. T., Quested, E., & Temby, P. (2018). The emergence of team resilience: A multilevel conceptual model of facilitating factors. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(4), 729768. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12237

- Kegelaers, J. (2019). A coach-centered exploration of resilience development in talented and elite athletes. Brussels University Press.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. 2009. Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd) Los Angeles: Sage Anderssen & J. Rygge translated Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Malone, M. K. (2018). An Exploration of the existence and development of shared understanding between football dyads. [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Abertay University. Available: https://rke.abertay.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/15405345/Malone_AnExplorationoftheExistence_PhD_2018_PhD.pdf

- McNiff, J. (2010). Action research for professional development: Concise advice for new action researchers (3rd) ed.). September Books.

- Morgan, P. B. C., Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2017). Recent developments in team resilience research in elite sport. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1(6), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.01.004

- Morgan, P. B. C., Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2019). Developing team resilience: A season-long study of psychosocial enablers and strategies in high-level sports team. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 101543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101543

- Rothwell, M., Stone, J., & Davids, K. (2020) Investigating the athlete-environment relationship in a form of life: An ethnographic study. Sport, Education and Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1815690

- Sanford, N. (1967). Where colleges fail: A study of the student as a person. Jossey-Bass.

- Savin-Baden, M., & Howell-Major, C. (2013). Qualitative Research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Oxford: Routledge.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice. Laerning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cam-bridge University Press.