Abstract

This paper presents a political ecology analysis of intergenerational land dynamics in cashew-producing areas of Ghana’s Brong Ahafo Region. In particular, the paper explores how the growing commercialisation of cashew production for export is driving generational “land grabbing” by older generations and local elites. To do this, we gathered data through interviews, focus groups and observations. Data were analysed through the thematic approach, a process of integrating similar themes from interviews and focus groups. We demonstrate two things: (1) how expanding cashew production is driving generational “land grabbing” by older generations and local elites; (2) how the customary land value is in deep tension with an emerging neoliberal land value. These emerging trends are causing the ‘disenfranchment’ of young people from access to land for cashew production. To this end, the benefits of cashew production for export are likely to elude young people in the region. Based on our findings, we call for a conscious attempt on the part of government to privilege young people’s access to land as part of land reform strategies and also to invest in cashew processing infrastructure to create opportunities for young people to participate in the downstream stages of commercial cashew expansion.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

In Africa, unemployment among young people remains a problem and has become a topical issue for discussion among national governments and development partners (FAO et al., Citation2014; Filmer & Fox, Citation2014; Losch, Citation2016; Sumberg et al., Citation2020; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). Increasing youth unemployment in Africa is a result of increasing youth population with limited employment opportunities in the formal sector (Sumberg et al., Citation2020). It is estimated that the population of young people between the ages of 15–24 years is expected to reach 60% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population by 2050 (United Nations, Citation2015). This is projected to result in a demographic youth bulge, and likely to aggravate the already dire unemployment situation on the continent (Aker, Citation2019; Stecklov & Menashe-Oren, Citation2019).

African governments have responded to youth unemployment particularly through provision of incentives (e.g. access to credit, market and skill-based training programmes) to engage young people in the agricultural sector. In much of government policy and programming, the agricultural sector is regarded as having the potential to create job opportunities for young people in Africa (Brooks et al., Citation2012; MasterCard; Foundation, Citation2015; Sumberg et al., Citation2017). Development professionals, such as Brooks et al. (Citation2012, p. 1) have also argued that “African agriculture can absorb large numbers of new job-seekers and offer meaningful work with public and private benefits.” Central to this orthodoxy is the recognition that agriculture is a sector of both change and opportunity for young people on the continent (Filmer & Fox, Citation2014).

Reflecting this, agricultural commercialisationFootnote1 is considered to drive employment and income generation for young people in Africa. Agricultural commercialisation is considered in policy discourse as key to enhancing access to technology, increasing the importance of processing and value addition, greater engagement with regional, national and global value chains (Yeboah et al., Citation2020). In particular, the production of market-oriented crops and participation in both local and international markets as part of the processes of commercialisation is fundamental to driving income generation among young farmers (Poulton, Citation2017). Thus, in theory, agricultural commercialisation should provide more and more diverse employment and income opportunities in both the farm and off-farm segment of the economy for young people (Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). In Ghana, agricultural commercialisation involving tree crop production has been a major policy priority dating back to the colonial period, facilitated largely by policy incentives, persuasion and coercion (Yaro et al., Citation2018). Colonial and post-colonial agricultural commercialisation policies in Ghana have contributed to changes in land and labour relations within the agrarian sector and have supported the expansion of production of tree crops for the export market (Yaro et al., Citation2018). In addition to policy and public investment, the commercialisation of agriculture is driven by increases in total land area cultivated, marketing incentives, and the changing demand preferences for specific agricultural products. For instance, increase in prices and demand for cocoa and cashew account for a significant expansion of land allocated for production of these crops and growth in commercialisation of agriculture in Ghana (Boafo et al., Citation2019; Chapoto et al., Citation2013).

However, the processes of commercialisation are uneven and the ability of different individuals to participate in and benefit from agricultural commercialisation is likely to differ across regions and among different social groups. For instance, proximity and access to markets, land tenure arrangements, transportation costs, as well as the nature of crops all play a major role in determining who participates in commercialisation processes (Yaro et al., Citation2018; Poulton, Citation2017). Young people, who form one of the vulnerable spectrums of the social classes in Africa may lack access to land as a result of tenure arrangements or increased value of land, and therefore may be constrained to participate in the production stage of the commercialisation process (Bezu & Holden, Citation2014; Chamberlin et al., Citation2021). Amanor (Citation2010) argues that young people generally want to participate in crop production but that a lack of access to land which result from commodification process serves as a major hurdle. Thus, consolidating ownership of land, growing interest in land from international investors and land enclosure by local elites in commercialisation hotspots affect the ability of young people to access land for farming (Jayne et al., Citation2019).

Nevertheless, some studies highlight rental land arrangements as pathway for young people to access land, particularly in the early stages of livelihood building (Chamberlin et al., Citation2021; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). But even with this it is difficult for young people to engage in tree crops production as rental arrangements only permits production of perennial and short term crops. Also, in situations where land access is guaranteed via rental and purchase arrangements, young people may be severely constrained owing to their limited capital and social assets (Chamberlin et al., Citation2021).

Ghana’s Brong Ahafo Region—the focus and case study of our research—has a long history of agricultural commercialisation through cocoa production (Berry, Citation1993). Increasing demand for land for cocoa production in the Brong Ahafo during the colonial and postcolonial eras drove significant socio-political transformation by changing the social and traditional institutions governing customary land (Austin, Citation1987; Berry, Citation1993; Hill, Citation1961; Pogucki, Citation1955). In particular, agricultural commercialisation through cocoa production commodified land and social relations by changing the intergenerational land tenure arrangements (Austin, Citation1987; Berry, Citation1993; Hill, Citation1961; Pogucki, Citation1955).

The Brong Ahafo Region is again experiencing agricultural commercialisation through increasing production of cashew nut—the focus of our research—for the export market (Amanor, Citation2009; Boafo et al., Citation2019; Boafo & Lyons, Citation2019; Evans et al., Citation2015; Peprah et al., Citation2017). Although cashew production has expanded to the northern part of Ghana, the Brong Ahafo Region is the largest producer of cashew (Boafo et al., Citation2019). Increasing production of cashew in Ghana is driven by the high global demand for cashew as well as government commercialisation policies (Boafo & Lyons, Citation2019). For instance, government of Ghana has since 2018 implemented a 10-year Cashew Development Plan with the aim to expand the production of raw cashew nuts from 70,000 metric tons to 300,000 metric tons annually and to increase the country’s current processing capacity from 65,000 metric tons to 300,000 metric tons annually.

The expansion of cashew production for export is driving competition for land and reinforcing significant socio-political transformation at the local level (also see Cotula, Citation2007). For instance, cashew production is driving and reinforcing changes in the intergenerational land tenure arrangements and land concentration by members of older generations and local elites. One important outcome of this is that, the younger generations are increasingly denied usufruct rights to family or communal land, thus unable to participate in the commercialisation process through cashew production. Although young people can participate in other stages of commercialisation such as processing, marketing and distribution chains, such opportunities are currently very limited, as over 90% of raw cashew nut produced in Ghana is exported to India and Viet Nam for processing (Boafo et al., Citation2019). Moreover, while commercialisation may also drive employment opportunities in the off-farm economy and the entire downstream stages of the agri-food systems (Haggblade et al., Citation2007, Citation2010; Yeboah et al., Citation2020), such opportunities are currently not well developed in the rural economy of the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana. Thus, the immediate opportunities for employment and income generation that exist in the highly commercialised cashew economy of the region are at the production stage. However, opportunities to get involved in cashew production are eluding young people because of challenges with accessing land. Despite the emerging changes to the customary land tenure system—with implications for young people—due to expansion of cashew production, there are notably a handful of studies that examine intergenerational equity—with the exception of Boafo and Lyons (Citation2019), Evans et al. (Citation2015), and Amanor (Citation2009), who have analysed the gender and power relations, and intergenerational land issues associated with cashew production in the Brong Ahafo Region.

While intergenerational rights to communal land have been a subject of study over decades, specifically, our paper contributes to emerging research literature in relation to cashew production in Ghana by examining the intergenerational land dynamics in cashew producing areas of the Brong Ahafo Region. Through a political ecology approach, we demonstrate two things: (1) how expanding cashew production is driving generational “land grabbing” by older generations and local elites; (2) how the customary land value is in deep tension with an emerging neoliberal land value. These emerging trends are causing the ‘disenfranchment’of young people from access to land for cashew production. On the basis of the findings presented, we argue that the benefits of agricultural commercialisation through production of cashew nut for export are not uniform across members of older and younger generations in the cashew growing communities in the region. We further argue that the outcome of expanding cashew production is reinforcing social differentiation, inequalities and class struggle in the cashew growing communities in the region.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section outlines the political ecology approach as the framework that has informed our analysis, followed by a brief review of the literature on young people and access to land in Africa. We then describe our case study, the Brong Ahafo Region and methods adopted for the fieldwork. Next, we present the findings of our research followed by a discussion of the key findings. The last section concludes with some key policy implications.

2. Political ecology approach

Geographers have had a long-standing engagement with trying to understand the multi-scalar, political-economic, and ecological processes that shape vulnerability to access to resources such as land, water and other environmental resources (Watts, 2013). A key approach in this regard is political ecology—broadly understood as a field analyzing the simultaneous political, economic, and ecological processes underpinning human access to and use of natural resources, with implications for sustainable livelihoods (Perreault et al., 2015). Political ecology provides a historical, political, power, scalar, economic and ecological approach to understand human-environment interactions (Perreault et al., 2015; Schubert, Citation2005).

Since its inception in the 1980s, the approach has offered explanations to how colonial and postcolonial development processes have integrated smallholder farmers in former colonised states into global markets, and the associated commodification of land, production and labour relations. Political ecology further provides a framework to understand social differentiation and class structure, as well as the dissolution of precolonial production systems and social relations in former colonised states (Robbins, Citation2012; Watts, Citation2016). The goal of this approach is to underscore the application of political ecology to explain resource conflicts, especially in terms of struggles over common resources (Robbins, Citation2012). Political ecologists basically argue that, to explain land grabbing, for instance, one has to consider broader historical, economic and political factors that shape land use and access. Thus, it is only within the broader political economy of competition for land that “land grabbing” could properly be understood.

Political ecology has several analytical tools that enables its applicability in different fields of the studies. Some of its key analytical frames include historical, scalar and power analyses. In particular, our research is informed by power analysis to bring new insights into the power relations between older and younger generations in accessing customary land for cashew production in Ghana. We adopt power analysis because, it is at the core of political ecology given that this approach seeks to understand questions around resource access, control, use and management (Peet and Watts, 2004). Power analysis focuses on understanding how the power to control resources manifests across different scales (Robbins, Citation2012). Some of the key questions often addressed by power analysis are: who has the power to control productive resources such as land, labour and capital? How is power contested around resources? Guided by these questions, Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner Kerr (2015) adopted power analysis to show how access to, and control of land is shaped by the broader historical context in the Upper West of Ghana. Similarly, Campbell (Citation2013) argue that power to control resources in former colonised states is largely shaped by capitalist relations of production instituted during the colonial period.

Building on these studies, we deploy power analysis to understand: (1) How access to land for cashew production in Brong Ahafo is negotiated between the different generations, (2) How intergenerational customary practices govern the use of, and access to, customary land and (3) How customary practices are changing in response to expanding cashew production for export market. Specifically, our analysis of expanding cashew production in the Brong Ahafo Region illuminates the struggles of young people to access customary land for cashew nut production for export. While these struggles play out at the local scale, they are shaped by the global capitalist political economy, including growing global demand for cashew nuts, alongside national and international neoliberal policies which are driving agricultural and land commercialisation in Ghana (see, for instance, Boafo et al., Citation2019). Figure is a conceptual illustration of the power to access land for cashew production amongst the various social groupings in the study area. We now turn to provide the context for our political ecology analysis of the intergenerational land tenure system, and land control and access, including how young people struggle to access land for farming in the Brong Ahafo Region in Ghana (our case study).

2.1 Young people and access to land in Africa: a brief literature review

The literature on the synergistic relationship between agriculture, land access and young people in SSA is relatively well developed. On the one hand, some studies suggest that the rental market and social relations are key in enabling young people to access productive resources (e.g. land) for agricultural purposes (Fylnn and Sumberg, Citation2017; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). On the other hand, an avalanche of research literature from a variety of contexts in SSA have highlighted the difficulties young people face in accessing land to pursue farming livelihoods (Anyidoho et al., Citation2012; Asciutti et al., Citation2016; Bezu & Holden, Citation2014; Chamberlin et al., Citation2021). Three common factors have been identified in the literature to explain the barriers young people face in accessing land. The first relates to the role of poorly functioning rural institutions, particularly of those associated with traditional land tenure systems. Filmer and Fox (Citation2014, p. 13) for instance, note that “insecure and unclear land rights, as well as constraints on renting or otherwise using land” limits young people’s ability to access land for farming. In a related way, Cotula (Citation2007) argues that the traditional land tenure systems in Africa may foster tensions between older generations who control land access and younger generations left with more limited land access opportunities. The second set of explanations relate to ongoing processes of land commodification within traditional land access regimes and of agrarian relations more generally (Amanor, Citation2010; Asciutti et al., Citation2016). Finally, poorly functioning land markets limit the availability of land for vulnerable demographic groups who may have little or no social and economic assets. Depending on the context, these factors may combine in a variety of ways to limit the availability of land for young people to pursue farming livelihoods.

Research findings from Uganda have underscored the importance of sub-division of land through inheritance as one important factor which is leading to a decline in farm size (Kristensen and Birch-Thomsen, 2013). The important role of land fragmentation equally emerged strong in the work of Anyidoho et al. (Citation2012) who found that land fragmentation was fundamental in pushing many young people out of the cocoa sector, even though there was perceived hierarchy across diverse categorisation—with on-farm agricultural production considered to be of low status in contrast to formal work. A recent study which draws on nationally representative and multi-year data from several African countries found that a progressively small sample of youth expect to inherit land owing to scarcity of land, to the extent that increased in adult life span had meant that those who expect to inherit land would have to wait a little longer (Yeboah et al., Citation2019). The increasingly complex modes of land inheritance in many West African societies are compelling young people to borrow or rent land from outside or inside the family group (Asciutti et al., Citation2016). Bezu and Holden’s (Citation2014) study in four SSA countries (Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Zambia and Kenya) found land fragmentation arising mainly from population pressure as the key constraint to young people’s engagement in agriculture. Only a small proportion of the youth (9 percent) aspired to engage in agriculture but had expectation to inherit land from a family member. In rural Burundi, it is often the case that young people inherit land from their familiar relations (parents), but it is unsurprising that young people face barriers with land access with each generation (see Berckmoes and White, 2014). This was clearly articulated in the narrative of one young man who participated in the study when he stated: “… we have only a small plot of land on which the house is built, and you, as a boy, you will let your mother stay there and you go find your own land” (Berckmoes and White 2014: 194). In this context, land inheritance serves as a constraint and shapes young people’s engagement in agriculture in Africa.

The increasing commodification of land defined as “when land takes on a monetary value and is exchangeable through market mechanisms—which accompanies rising demand for land by outsiders” (Cotula, Citation2007; Chamberlin et al., Citation2021, p. 59), often serves as a major constraint that young people face in accessing land (Amanor, Citation2010; Kidido et al., Citation2017; Kumeh and Omulo, 2019). In the Western and Eastern regions of Ghana young people have been reported to face severe difficulties in accessing land owing to the sale of family land to migrant cocoa farmers (Amanor, Citation2008; Berry, Citation1993). Corroborating this observation, evidence from many agrarian societies highlight how older generations (community elders, parents or chiefs) retain enormous control over land for a prolonged period, and many desire to allocate land to investors from outside their local communities mainly via rental arrangements, instead of allowing cultivation rights to local youth (Cotula, Citation2007; Chauveau et al., Citation2006). In some cases, this resulted in social conflict and significantly constrained youth engagement in agriculture (Chamberlin et al., Citation2021; White, Citation2012).

In response to their socio-economic marginalisation by elders, young people forcibly enter and take possession of properties of outsiders or migrants who have been granted access to customary land (Amanor, Citation2008; Kidido et al., Citation2017). For instance, in Rwanda, compared to young headed households, land is mostly owned by adult headed households (André and Platteau, 1998). But to resolve the problem of land fragmentation the government of Rwanda has banned the sub-division of agricultural lands into units smaller than 1 ha (Aciutti et al., 2016). Evidence from Western Burkina Faso demonstrates that access to land by young people is rooted in adult-imposed restrictions by family heads (Cotula, Citation2007; Chauveau et al., Citation2006). Kidido et al. (Citation2017) note that high land cost and scarcity of land are two fundamental challenges confronting young peoples’ desires to enter into commercial farming in Techiman, Ghana. Indeed, “the virtual non-existence of access to agricultural land through purchase by the youth in the Techiman area, suggest that the focus is on gift, inheritance and sharecropping (cash crops option) which are other plausible mechanisms for the youth to access land on long-term basis for agricultural purpose” (Kidido et al., Citation2017, p. 12). However, out of 455 sample youth, only 12 percent could access land as gifts from older generations. A smaller proportion (4 percent) among the sample accessed land through inheritance (Kidido et al., Citation2017). A recent review of the academic and policy literature on youth and employment in rural Africa highlights the centrality of land as one of the major difficulties young people face in pursuing agricultural-based livelihoods (Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021).

The issue of intergenerational power dynamics vis-à-vis the involvement of local elite in land grabbing across Africa is also a contributing factor to the inability of young people to access land. Over the years, governments across Africa have worked to lease large tracts of land to corporations, foreign investors, and local powerful elites (Hall et al., 2015). This, together with increasing demand for biofuels, and other plantations, has led to land grabbing on the part of powerful local elites and other corporations. Indeed, local elites and other foreign firms are perceived to have more financial muscle and technology to undertake large-scale investment in contrast to local people (e.g. young people) who have limited financial capital (Hall et al., 2015). The dispossession of local folks of land in favour of plantation agriculture and large-scale farming through land grabbing by powerful elites often makes no provision for the “next generation, forcing the dispossessed and most particularly the younger generation into wage labour, either locally or through mass out-migration” (White, Citation2020, p. 43). Moreover, land grabbing has been reported to have displaced local smallholders from their farms and homes, contributing to potential destruction to livelihoods and ability to meet daily subsistence (Alhassan et al., Citation2018).

Taken together what appears fundamentally clear from these studies is the important role that access to land shapes young people’s ability to participate in and benefit from expansion of crop production for sale or demand for agricultural produce. Mirroring the work of Yaro et al. (2016) in Ghana who found that households with no access to land holdings is highest in highly commercialised farming zones, in contrast to out-grower and plantation areas, Yeboah et al. (Citation2020) note there is the likelihood for young people who want get into crop production to face significant barriers in context where commercialisation increases the value of land.

3. Case study of Brong Ahafo Region: Ghana’s Cashew production “hub”

Fieldwork for this study was conducted in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana in 2016. Since then, in December 2018 after a referendum on the creation of new administrative regions, the single region was divided into three namely: Bono East, Bono and Ahafo regions. Throughout this paper, we use Brong Ahafo as a collection of the three regions. The Brong Ahafo region comprises a vast tract of land (39,5558 km2), and favourable agro-ecological characteristics for the development of both food and cash cropping. For instance, the region experiences two rainfall seasons annually, allowing for two farming seasons each year (Logah et al., Citation2013; Noora et al., Citation2017). The major farming season runs from March to July, while the minor season is from August to December (Amanor, Citation2013). The dry season, or harmattan (between December and March), is often described as the off-farming season. The different agro-ecological zones that characterise the region enable the cultivation of a variety of crops, including cereals, tubers and vegetables, as well as tree crops including cashew, mango, citrus and cocoa (Boafo et al., Citation2019; Boafo & Lyons, Citation2019).

In particular, cashew production expanded gradually into the Brong Ahafo region through farmer networks in the late 1970s from communities along the Ghanaian–Ivorian border, such as Banda, Seikwa, and Kejetia (Amanor, Citation2009; Evans et al., Citation2015). Since then, policy narratives and liberalisation of the commodity market in the 1980s incentivised the production of cashew nut for export (Moseley et al., Citation2015; Yaro et al., 2016). For instance, cashew nuts became one of the non-traditional commodities developed as part of the government’s export diversification strategy in the 1980s (GoG, 2000). Reflecting this, government, development partners and donorsFootnote2 have implemented several projects in the Brong Ahafo and other regions aimed at promoting cashew production as part of agricultural commercialisation and commodity diversification, leading to increased income and reduced poverty, structural transformation in Ghana. The support from state and non-state actors has made the Brong Ahafo Region the current largest producer of cashew in Ghana.

According to the 2021 Population and Housing Census every one in four (19.7 percent) young person is unemployed in the country. For young people within the ages of 15–35 years, the situation is even more severe given that the unemployment rate for this group is estimated at 32.8% (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). The Brong Ahafo region is among the regions in Ghana the with largest percentages of young people in the country who are not involved in the labour market 36.08% (Ghana Labour Force Report, 2015; Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). However, reliable data on unemployed youth at the district and communities where the research was undertaken are difficult to come by.

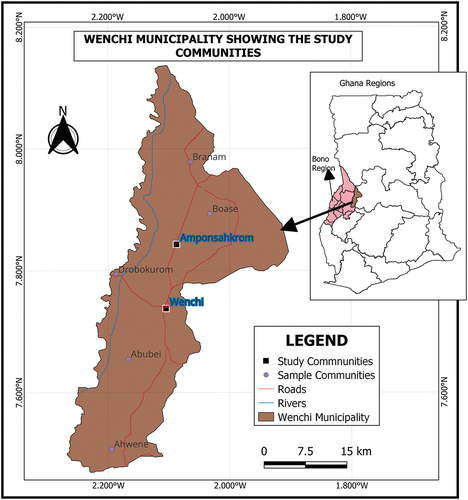

Data were gathered from two communities, namely Wenchi and Amponsahkrom. Both communities are located in the western part of the region and are 5 km apart. According to the recent Ghana Population and Housing Census, Wenchi Municipality where both Wenchi and Amponsahkrom are situated, had a population of 124,758 in 2021 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). Females (611,9673) slightly outnumber the male (596, 676) population in the Municipality (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). Wenchi is inhabited largely by Bonos—who are the indigenes and traditional owners of the land—and migrant ethnic groups including Dagaabas, Badu, Banda, Mos and Sisalas. Meanwhile, Amponsahkrom is inhabited mainly by Dagaabas, who are migrant farmers from Lawra in the Upper West Region of Ghana. Farmlands in Amponsahkrom is owned and administered by the indigenes of Wenchi. Wenchi and its nearby site Amponsahkrom were chosen for this study because, Wenchi is one of the most conservative and traditional towns in the region and the entirety of Ghana. The indigenes and migrants pay allegiance to the Wenchi Paramount Chief or traditional authority. As per tradition, the Paramount Chief is the custodian of the customary land which is made up of stool and family land. Stool land in Wenchi and other societies in Ghana is type of land that directly owned and administered by the traditional authority, while family land is type of land that is directly owned by a family and administered by the family head (also see, Amanor, Citation2009; Boafo et al., Citation2019). All indigenes of Wenchi have usufruct rights of customary land as a practice laid down by their forebearer. However, these customary systems are responding to social, economic and political changes due to integration of local production systems into the global production system Cotula, Citation2007).

Like many communities in Ghana, more than half of the population (an estimated 740, 593) in the Wenchi Municipality fall within 15–64 years which includes the youth population (15–35 years; Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). Despite government and donor support, and commercial production of cashew, unemployment among the youth remains a challenge in the area. Moreover, poverty is endemic, particularly among landless migrant farmers, who frequently resort to borrowing, begging, labouring and engaging in low-paying menial jobs as coping strategies. Figure is a map of Ghana and Wenchi Municipality showing the study communities.

4. Research methods

Our research was designed to analyse how expanding cashew production for export is shaping the intergenerational land tenure system in Wenchi and its nearby community, Amponsahkrom. To do this, we adopted a qualitative case study approach (Strijker et al., Citation2020). This approach enables the exploration of a social phenomenon within its context, using multiple data sources (Strijker et al., Citation2020). This approach ensures that varieties of methods are practically employed to understand a social phenomenon in its context. The research adopted the case study approach based on its effectiveness in empirically investigating a unique social phenomenon which requires in-depth understanding within its actual context (Yin, 2003). The case study approach was also adopted on the basis that it can allow an in-depth understanding of emerging land use changes and their impacts on young people in Wenchi and its environs. Thus, this work is exploratory, with a focus on depth of understanding rather than breadth.

4.1. Data collection

Maximum variation sampling, also known as heterogeneous sampling, was used to select participants for this study. Maximum variation sampling is a purposive sampling technique used to capture a wide range of perspectives relating to the things of interest to the researcher (Benoot et al., Citation2016). We adopted maximum variation sampling to gather different perspectives about land access for cashew production from old and young generations in the research communities. The main fieldwork was conducted over six months, from June to November 2016. We returned to the research communities in July 2021 for a follow-up study to ascertain new and emerging trends since our first study in 2016. Table summarises the number of participants that were selected using the maximum variation sampling technique.

Table 1. Social groupings of study participants

Participants represent all the different social groups and categories of farmers as well as those with diverse levels of farming experience. Also, farmers included in this research represented diverse ethnic groups, as well as different age groups and gender. For instance, the ages of the older generation ranges from 50 to 75 years. For young people, we recruited those between the ages of 15–35 years. We define young people here as the young generation of the matrilineal family of the older generation. Through the assistance of an agriculture extension officer, eligible participants were approached face-to-face and asked whether they would participate in the study. Although several eligible participants were willing to participate, it was made clear that participation was voluntary, with a reassurance of the confidential and anonymous nature of the study. Participants were interviewed in their homes or near their farms. Although an interview guide was used to ensure consistency in the interview process, participants were encouraged to share their experiences regarding cashew production and access to land as much as possible. In all, we interviewed 34 participants. This sample is deemed adequate for qualitative research. In fact, previous studies recommend that qualitative research require a minimum sample size of at least 12 to reach data saturation (Clarke & Braun, 2013; Fugard & Potts, 2014). In this regard, a sample of 34 participants was deemed sufficient for qualitative analysis and scale of the study. However, we make no claims of generalisability of the findings owing to the small sample size. Nevertheless, the evidence presented is highly relevant to Ghana and may reflect the situation in another context.

In-depth interviews with farmers covered broad themes, including drivers and benefits of cashew production, land access and the changing nature of intergeneration customary practices, as well as some of the impacts associated with cashew production. In-depth interviews with traditional leaders covered themes including traditional practices governing customary land, how customary land is administered by traditional authorities and family heads, how emerging commercial pressures are driving changes in intergenerational customary practices and the future of traditional land institutions in Wenchi and its environs. In addition to in-depth interviews, a focus group was conducted to provide a platform for collective discussions and perspectives on cashew production and land access. On average, interviews lasted one hour and were tape-recorded with permission from participants. Detailed hand-written notes were also taken to enhance data analysis.

In addition to in-depth interviews, a focus group was conducted to provide a platform for collective discussions and perspectives on cashew production and land access. The focus group was conducted with 10 participants, making up of 5 young people and 5 older people. The focus group was iterative; emergent themes from the in-depth-interviews were explored further, enabling rigorous validation of information (Miles et al., 2014). The focus group discussion was conducted in an open and relaxed manner, providing space for discussants to share their views and experiences on emerging cashew production and its implications on land access. The discussion lasted for about 1 hour, 30 minutes and was tape-recorded with permission from discussants. Interviews and focus group were conducted in Akan, a dominant language spoken by 48% of Ghanaians (Kutsoati & Morck, Citation2012).

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the School of Social Science Ethical Review Panel (SSERP), University of QueenslandFootnote3 [RHD3-2016]. Key ethical principles informed the conduct of this research. Thus, principles including voluntary participation, harmlessness, informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality were appropriately applied during the data collection process.

4.2. Data analysis

Recorded interviews and focus group were transcribed and translated into English. Transcribed texts were then compared several times against recorded audio files to enhance accuracy in the data for analysis. Transcripts were coded manually to organise, distil, and sort for analysis. In analysing the data, themes were inductively derived “bottom–up” from the transcripts and not “top–down’from pre-existing theoretical concepts (Miles et al., Citation2019). To ensure rigor and trustworthiness in the findings, we have maintained participants” own words in the results with the use of low inference descriptors (Baxter and Eyles, 1997; Miles et al., Citation2019). While the individuals interviewed are not representative of the entire population, the sample size is sufficient for qualitative research, as saturation was reached with no new categories of information emerging from the data (Miles et al., Citation2019). In order to keep the identity of participants confidential, we did not mention their names in our analysis.

We also conducted farm-based observation at three cashew farm sites to understand the emerging trend of conversion of existing farmland into cashew, as well as cultural practices and social relations.

5. Findings

5.1. The drive for cashew production in Ghana’s Brong Ahafo

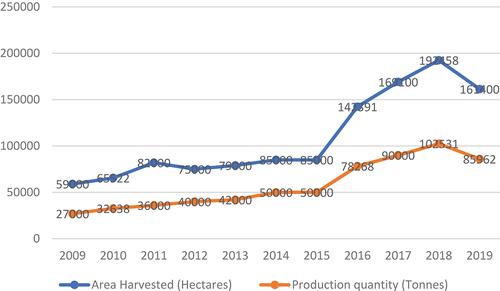

Ghana, the focus of this research, has experienced a surge in the production of cashew nuts for export in the past decade (see Figure ). The growing production of cashew nut in Ghana is driven largely by the high global demand for cashew nuts (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD), Citation2021). India and Viet Nam are, by a wide margin, the largest importers of raw cashew nuts from Ghana. The nuts are processed in India and Viet Nam and further exported to the global North for onward processing and consumption. As stated earlier, in Ghana cashew is largely produced in the Brong Ahafo Region due to ecological and political reasons.

Interviews conducted among cashew farmers in Wenchi reveal that, during cashew harvesting season, Asian processors through their local agents buy cashew nuts at a negotiated farmgate price between farmers and buyers. There are also some young people who act as intermediaries by buying and aggregating cashew nuts from farmers for onward selling to exporters. During this research in 2016, a kilo of cashew nuts was sold at about Gh¢5, a price which has been described by farmers as higher than what they often receive for their food crops. During our follow-up study in 2021, a kilo of cashew nuts was still sold around the same price. Farmers complained that the price of cashew has not been uniform across communities, and among buyers. Despite this, they still described the farmgate price of cashew as higher than what they often receive for their food crops. Thus, high farmgate prices alongside the availability of a ready market largely incentivised farmers to engage in cashew production in the Brong Ahafo Region for the export market. A farmer who had seven and half acres of cashew farm in Wenchi reiterated in an interview;

for cashew, there is ready market, before you bring your nuts from the farms the buyers are waiting by the side to buy. The buyers are from Asia, but they have agents here in the community who buy for them. After buying, they dry the cashew on the pavement at the Wenchi market. They then pack the nuts into sacks and load them into about six to seven long tracks and transport to Accra for export (Farmer, 56 years, Wenchi).

Many of the farmers during interviews compared income earned from food crops such as maize, yam, and cassava to that of cashew nuts and concluded that they would prefer producing cashew nuts to food crops:

what I have realized is that whether we are strong or not, we don’t earn income when we farm food crops. Cashew gives us more money than food crops. Some of us have started harvesting our cashew and the price is higher than for food crops. Cashew takes only 3 years to start fruiting (Focus group, Amponsahkrom).

This suggests that the integration of farmers into the global market shapes their decision to choose production of cashew nuts over food crops, thereby driving increasing conversion of existing farmlands into production of cashew nuts for the export market. Thus, the decisions of local farmers in Wenchi to produce cashew nuts are largely formed in a predetermined market, a process that leaves them vulnerable to the forces of the global market.

Data presented in Figure shows that between 2009 and 2019 cashew output increased with a corresponding increase in land area used for cashew production in the Brong Ahafo Region. The region produces over 90% of Ghana’s annual cashew output. Indeed, interviews conducted with farmers in July 2021 reveal that cashew production has expanded steadily since 2016. The increasing expansion of land for cashew production, however, is driving competition for land, leading to land enclosure, consolidation and displacement in Wenchi. In particular, the drive for cashew production has brought about intense competition for customary land between younger and older generations, and between local elites and poor farmers. In subsequent sections, we explore how intergenerational customary practices governing the use of customary land have been implicated by the growing demand for land for cashew production.

5.2. Struggles between younger and older generations over family land

Land, in the research communities of the Brong Ahafo Region is divided into stool and family lands. Both stool and family lands are customary lands, considered as an intergenerational asset, upon which the livelihoods of both younger and older generations are predicated. The belief that governs the administration of customary land is that it belongs to the past, present and future generations, irrespective of social status, class, age and gender. The stool land, as the name suggests, is under the direct administration of the Chieftaincy institution. The family land is under the care of the matrilineal family, of which the most senior man, acts as the family head and is responsible for its administration. This suggests that all family lands in the research communities are under the custodianship of members of older generations as customs and traditions require. The primary purpose of the family land, and for that matter customary land, is to ensure that each member of the family has a parcel of land for subsistence agriculture to meet their basic needs such as food. To maintain intergenerational equity and fairness, no member of the family is required to acquire exclusive possession either by planting tree crops or engaging in long-term or fixed investments on the family land. Long-term investments such as tree crops or plantations on family land cannot be passed on to one’s children and wife as an inheritance or gift under any circumstances. In an interview with a family head in Wenchi, he said;

any family member can grow both food and tree crops on the family land but when they pass on, the farm belongs to the family. The person who succeeds the demised will take custody of the farm on behalf of the family (Family head, 72 years, Wenchi).

This is to say that, intergenerational customary beliefs and practices prohibit consolidating user rights on family land as it belongs to all generations of that family descent. However, interview responses from both younger and older generations demonstrate that these intergenerational customary land beliefs and practices are changing, driven in large part by the increasing competition for land for cashew production for export. The older generation, who by their seniority are custodians of customary practices, are consolidating their user rights over the land by planting cashew and other export crops. This was evidenced during an interview in Wenchi with a farmer who is a custodian of his family land. He emphasises that members of the younger generation are not able to access family lands for farming because members of the older generation are planting cashew on the family lands, thereby consolidating use of lands for a long period of time. He further admitted that he is a culprit because he has a cashew farm on his family land. He said;

because, we the older generation are planting cashew and mango on the family land, the younger ones in the family are having problems accessing the land’ (Farmer, 64 years, Wenchi).

Further discussions with him reveal that planting cashew and mango on the family land is intentional, although tradition prohibits planting of tree crops on the family land. He describes his intention as “smart” because if he does not have any long-term investments on the family land, it will go back to the family at his demise. He said;

if I don’t plant cashew or mango on the family land, the land goes to the family when I die. So, I have to be ‘smart’ to develop some property on the family land and share it among the family, my wife and children (Farmer, 64 years, Wenchi).

It could be deduced from the illustration that the decision to consolidate family land by members of the older generation is driven by the cultural obligation that require parents, particularly fathers to secure property for their children before they pass on. With diminishing of arable land in the research communities, older generations expressed concerns their children might not be able to access land from their families. For instance, a farmer in Amponsahkrom said in an interview “the rate at which we are farming cashew in this area, our children will find it difficult to access land for farming in the future.” Reflecting this, parents feel compelled to acquire land and property for their children, so the latter do not face any difficulties in accessing land in future. Parents therefore consider cashew farms as a long-term investment to be passed on to their children. By doing this, members of older generation are consolidating their power and control over family lands, thereby denying younger generation access to land.

Similarly, a young farmer recounted how changing intergenerational land tenure system is limiting access to land by younger generation for farming. He reiterates that increasing land concentration by members of older generation and their unwillingness to observe intergenerational land tenure practices is driving land scarcity in the research communities. He said in an interview;

the major challenge facing us young people is that we are unable to access family lands for farming. Our elders [Older people] who control and administer family lands are no longer transferring them to us but rather to their wives and children, because they have cashew on the lands (Farmer, 32years, Wenchi).

These responses point to one thing, that is long-term individual ownership of family lands by members of the older generation so as to guarantee long-term access to their cashew farm. To guarantee long-term access to family land, older generation after planting cashew negotiate with the family head to pay compensation in which ownership of that portion of family land will be released to him. Some of members of the older generation even resort to the court system to secure tenure on family lands (also see, Boafo & Lyons, Citation2019). This does not suggest that all members of the older generation or that it is only the older generation who engage in such uncustomary practices. Some members of the younger generation who are able to access family lands for food production are also converting into cashew production and engaging in uncustomary practices in way that affect intragenerational land tenure access.

The increasing consolidation of land by members of the older generation is also driven by the perception that young people are not interested in farming. Interview responses show that the belief that young people are not interested in farming is commonly held by a large proportion of members of the older generation in the research communities. In two separate interviews, two aged farmers recounted;

the truth is that there is no support for young people here, so they are not interested in farming, they cannot do drudgery and do not even have money to purchase agricultural inputs for farming (Farmer, 60 years, Wenchi).

the only problem here is that young people are not interested in farming, it is only we the aged doing farming, and so if there can be any policy that will help make agriculture attractive to young people, it will be good. Because, when we all face out, it will be a big problem for Ghana (Farmer, 58years, Wenchi).

The perception that young people are not interested in farming drives control of family land by the members of older generations. Although there is evidence that some young people are not interested in farming, their aversion can be partly attributed to their inability to access land and other productive assets due to control by the older generation and local elites. This is because young people will have to wait so long, perhaps until the demise of older people to access land. Indeed, some young people are interested in farming, especially when they can easily access land, other inputs and market. For instance, interactions with young people suggest that some of them who have migrated to the cities as a means of escaping poverty in their communities, upon hearing the profitability of cashew production, have returned to invest in its production. A young farmer said in an interview; “I migrated to a different community but I have returned to request for part of my family land to engage in cashew production” (Farmer, 34 years, Wenchi). Although this is the story of some young returnees, however, the reality is that they cannot access family land to engage in cashew production.

5.3. Increasing land acquisition by non-indigenes

In addition to the struggles between members of the younger and older generations over access to customary land—including patterns in our findings that demonstrate the concentration of land ownership by member of the older generation—data from cashew growing communities show that the expansion of cashew production is driving increasing acquisition of land by non-indigenes of the communities. We defined non-indigenes as Ghanaians from other parts of Ghana outside the research communities who do not pay allegiance to the Wenchi traditional authority. Non-indigenes by customary practices cannot access customary land as a customary right but rather as a gift or token. In the research communities, we have identified two sets of non-indigenes, namely migrant farmers and non-migrant farmers. Migrant farmers are farmers who have migrated from the northern part of Ghana in search of farming opportunities in Wenchi and its environs. Migrant farmers in Wenchi and Amponsahkrom have relied on informal arrangements including sharecropping, land rental and gift to access customary land for subsistence farming (also see, Boafo & Lyons, Citation2019). However, on the basis of growing recognition of cashew nuts as an income earning opportunity, migrant farmers with the financial capacity are acquiring customary land for cashew production. Thus, wealthy migrant farmers are shifting away from insecure land tenure arrangements such as rentals, sharecropping and token to a secure tenure through paying for land lease. This is driven by the fact that cashew trees last for 20–30 years (Catarino et al., Citation2014) and thus one requires secure land tenure to be able to grow cashew. A migrant farmer in a focus group discussion reiterates that;

for us migrant farmers, we don’t have secure tenure over land here, we can only plant cashew when you have bought the land (Focus group, Amponsahkrom).

Migrant farmers often acquire stool and family lands from family heads and the traditional council, respectively, a development that has been described by young indigenes as uncustomary and in disregard of their usufruct rights. Younger indigenes described not acquiring land because of the feeling that the land belongs to them as family members and indigenes; therefore, they have usufruct rights, unlike non-indigenes. It must be noted that some young people may want to acquire land for cashew production, however members of the older generation prefer leasing land to non-indigenes, because they get competitive price from non-indigenes. A young farmer reveals in an interview; “members of the older generation prefer leasing land to non-indigenes because they get better prices for the land from non-indigenes than indigenes” (Farmer, 34 years, Wenchi).

The second category of non-indigenes in Wenchi and Amponsahkrom are non-migrants. The non-migrants are from other communities, cities and towns in Ghana and are not staying in the research communities but have acquired land for cashew production. They are able to acquire customary land through existing social relations and networks. In particular, they acquire land for cashew production through the assistance of their friends, who are indigenes, and most of the time, young people. The latter give them all the necessary information and lead them through the customary procedures to access land from chiefs and family heads. Interviews with cashew farmers show that Ghanaians from cities and other communities have acquired land for cashew production. For instance, in an interview with a 60-year-old cashew farmer in Wenchi, he said “people from cities and towns have come here to acquire family lands for cashew production.” Although non-migrants do not live in the cashew growing communities, they are able to produce cashew under the care of indigenes and landless migrant farmers. When land is acquired for cashew production by a non-migrant, the labour of migrant farmers or indigenes is acquired to provide all the agronomic practices such land preparation, planting of cashew, and weed control until fruiting. The indigenes or migrant caretakers may be paid for their labour or benefit through sharecropping or intercropping arrangements. This involves intercropping cashew with food crops, where the caretaker only benefits from the food crops, although they have contributed their labour to maintaining the cashew farm until fruiting.

6. Discussion; different outcomes for different social groups

Overall, the picture that emerges is that farmers in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana have been integrated into the global commodity market both through past and contemporary agricultural commercialisation process. In particular, the increasing demand for cashew nuts at the global level is driving increasing demand for land for cashew production in the Brong Ahafo Region. Increasing production of cashew nuts in Ghana for the export market suggests a gradual but rapid conversion of existing land or expansion of agricultural land into cashew production. Reflecting the work of previous studies, our research demonstrates that existing cropland as well as new agricultural frontiers are being converted into cashew production (see, for instance, Amanor, Citation2009; Boafo et al., Citation2019; Boafo & Lyons, Citation2019; Evans et al., Citation2015; Peprah et al., Citation2018).

The increasing expansion of cashew production is leading to rising incomes for cashew farmers including those with whom we worked with who reported earning significantly higher income from cashew than food crop production. This is particularly so because cashew nuts are largely bought by Asian processors who have entered into the local economy and work largely through local agents, who aggregate the nuts from farmers in the communities. In addition, there are local processors, who compete with the foreign processors for the cashew nuts in the communities. The competition for cashew nuts gives farmers a ready market as well as drives the farmgate price high, a price farmers described higher than what they often receive from sale of food produce. Similarly, Peprah and others (2018) who conducted a study in the Jaman South District of the Brong Ahafo Region found that capital at household’s disposal has increased for cashew-producing households. They further state that both financial and social capital has increased directly through cashew production due to the revenue earned from cashew as well as their participation and membership in non-governmental organisations. In an earlier publication reporting on data from Jaman North District, Evans and others (2015) found that income from cashew production was being used to improve housing, food quality and supply, education and healthcare.

Nevertheless, the startling revelation of our research is that the benefits associated with expanding cashew production are not equally shared. What appears fundamentally clear is that not all age and social groups are deriving these benefits. An important factor shaping this as demonstrated in the political ecology analysis framework is who has access to power and control over resources. Among the social groups, older generations, who by seniority has control and power as custodians of customary land, largely engage in the production of cashew. Realising the immediate benefits and prospects of cashew, the older generation consolidates their powerful position and control over customary land by establishing cashew farms on it. This is affecting the ability of young people to access land for cashew production, and further reinforces common narrative within the policy literature that young people are disadvantaged in terms of accessing land (AGRA, Citation2015). The paper further highlights how past and present attempts to commercialise agriculture in Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana and presumably other regions of Africa drive social differentiation, elite capture and dispossession of vulnerable groups (Amanor, Citation2009; Austin, Citation1987; Campbell, Citation2013). In effect, the benefits associated with expanding cashew production in the region are being accrued by the older generation who tend to have power and control over productive assets (e.g. land) to engage in production. This finding mirrors the work Evans et al. (Citation2015), who report that older generations in the Jaman North District of the Brong Ahafo Region were individualising family lands through production of cashew to the neglect of young people. In this regard, what our findings tell is that young people in Brong Ahafo who aspire to make long-term investment in cash crop production are likely not to be able to do so owing to constrained access to land (see also, Kidido et al., Citation2017)

The constrain to access to land that young people in the communities and elsewhere within Brong Ahafo face is also an outcome of the increasing intrusion of non-indigenes into Wenchi and Amponsahkrom which is also reinforced by the power dynamics at play in the study communities. Indeed, commercialisation hotspots have long been described as centres of attraction of migrants (Jayne et al., Citation2019). The increasing expansion of cashew production for export and the social and financial rewards associated with it in the studied communities and other parts of Brong Ahafo have made cashew production attractive, and this is leading to the influx of migrants and local elites into the cashew growing communities to acquire land for cashew production. Similar to what Yeboah et al. (Citation2020) have reported, our research findings demonstrate that being in a commercialised rural economy and having the right financial and social capital allows non-indigenes (migrants and non-farmers) to acquire land for cashew production. The non-migrant who are mostly local elites with huge financial capital outlay are able to acquire large tracts of land and hire labourers (mostly young people) to engage in cashew production for them. Although such non-migrants do not live in the cashew producing communities, they rely on the labour of landless migrant farmers and local youth to engage in cashew production in the research communities. These non-migrants are mirroring what has been described in the literature as “telephone farmers” (see Leenstra, 2014; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). The influx of non-indigenes who are yearning to invest and take advantage of the opportunities associated with the growing commercial production of cashew creates intense competition for land, and this is contributing in part to alienation of local youth from accessing land for farming. Members of the older generation who have access to and control over family lands are leasing them, and this has allowed “outsiders” with the financial and social capital to access land at the expense of young people in the communities (see, also Peprah et al., Citation2018). Overall, while non-indigenes may have the financial outlay and networks to facilitate their access to land, it does not automatically guarantee that they would have access to land for farming. Historically, the power dynamics that is at play in the local community where older generations control the decision-making process as to whether to lease family land or not is fundamental and reinforce the potential of non-indigenes to acquire land for cashew production (also see, Chauveau, Citation2007).

7. Conclusion

This paper has presented evidence from a case study in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana, where increasing expansion of cashew production is reinforcing intergenerational land inequity. Our findings highlight that the intergenerational land dynamics in cashew producing areas of the Brong Ahafo reveals; first, a form of generational “land grabbing” strategy deployed by the older generation to privatize land, and second, a deeply conflictual land ownership values where the customary land value is in deep tension with an emerging neoliberal land value (also see, Berry, Citation1993; Chauveau, Citation2007).

These findings contribute substantially to the discourse on political ecology scholarship in a number of ways. First, what we see is that government and donor policies together with neoliberal market forces are driving agricultural commercialisation through expanding production of cashew with uneven benefits between older and younger generations. Second, drawing on power analysis, the crux of the findings is how power differentials mediate who has access, control and use of land for cashew farming. This is central to the political ecology analysis framework which allow us show how unequal power relations between older and younger generations shape access and control over customary land for cashew production in which younger generation have limited access to land for commercial production of cashew. Thus, the unequal power relations between older and younger generations in the control of land shapes who is able to take advantage of the opportunities brought about by commercial production of cashew.

These findings have important implications for policies seeking to promote youth employment in Africa. First, the findings suggest the need for land tenure systems to undergo reformation. One way to do this is for the state to engage in broad-based reforms of state land to give young people preferential access to land. Second, and even more important, we are of the view that the unequal power relations and struggle between the youth and older generation, which limits young people’s access to family-owned land, is likely to continue into the foreseeable future. Again, while there is active commercial production of cashew in the study sites, the process of rural transformation has not yet changed the landscape of opportunity (see, also Yeboah et al., Citation2020). This has meant little space for young people to engage with the active value chain activities or quality differentiation. Our findings therefore reinforce on-going calls for a conscious attempt on the part of government to invest in cashew processing infrastructure alongside with technology to expand cashew processing in Ghana. This will likely create demand for more labour and opportunities for young people to participate in the downstream stages of commercial cashew expansion in the Brong Ahafo Region. Future research could explore how the state and large-scale land acquisition by local elites is changing customary land practices in cashew growing areas of Ghana’s Brong Ahafo Region.

Acknowledgement

Data for this paper was part of a PhD fieldwork sponsored by University of Queensland, Australia. James Boafo thanks the University of Queensland for funding the PhD study through the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and both authors thank the anonymous reviewers who provided critical feedback on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We define agricultural commercialisation as “when agricultural enterprises and/or the agricultural sector as a whole rely increasingly on the market for the sale of produce and for the acquisition of production inputs, including labour. It is an integral and critical part of the process of structural transformation through which a growing economy transitions, over a period of several decades or more” |(Poulton, Citation2017, p. 4)

2. Examples include Adventists Development and Relief Services (ADRA), Technoserve, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the German Development Agency (GIZ)

3. This research was part of a PhD research at the University of Queensland, Australia.

References

- Aker, J. C. (2019). Information and communication technologies and rural youth. SSRN Electronic. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3523207

- Alhassan, S. I., Shaibu, M. T., & Kuwornu, J. K. (2018). Is land grabbing an opportunity or a menace to development in developing countries? Evidence from Ghana. Local Environment, 23(12), 1121–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2018.1531839

- Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). (2015). A new era for agriculture in Africa. Annual Report 2015. In Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (Agra).

- Amanor, K. S. (2008). The changing face of customary land tenure. In J. Ubink & K. S. Amanor (Eds.), Contesting Land, Custom in Ghana, State, Chief And, the Citizen. Leiden University Press (pp. 55–80).

- Amanor, K. S. (2009). Tree plantations, agricultural commodification, and land tenure security in Ghana. In J. Ubink, A. Hoekema, & W. Assies (Eds.), legalising land rights: local practices, state responses and tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America (pp. 133–162). Leiden University Press.

- Amanor, K. S. (2010). ‘Family values, land sales and agricultural commodification in south-eastern Ghana. Africa, 80(No.1), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.3366/E0001972009001284

- Amanor, K. S. (2013). Dynamics of maize seed production systems in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana: Agricultural modernisation, farmer adaptive experimentation and domestic food markets. Future Agricultures Working Paper 061. Brighton: Future Agricultures Consortium at the University of Sussex.

- Analytical report, Wenchi Municipality. Ghana Statistical Service

- Anyidoho, N. A., Leavy, J., & Asenso‐Okyere, K. (2012). Perceptions and aspirations: A case study of young people in Ghana’s cocoa sector. IDS Bulletin, 43(6), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00376.x

- Asciutti, E., Pont, A., & Sumberg, J. (2016). Young people and agriculture in Africa: A review of research evidence and EU documentation. Institute of Development Studies Research Report, 82. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/12175/RR82.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Austin, G. (1987). The emergence of capitalist relations in south Asante cocoa farming, 1916–1933. Journal of African History, 28(2), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700029777

- Benoot, C., Hannes, K., & Bilsen, J. (2016). The use of purposeful sampling in qualitative evidence synthesis: A worked example on sexual adjustment to a cancer trajectory. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0114-6

- Berckmoes, L. H., & White, B. (2016). Youth, farming, and precarity in rural Burundi. In Generationing Development (pp. 291–312). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berry, S. S. (1993). No Condition Is Permanent: The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Bezu, S., & Holden, S. (2014). Are rural youth in Ethiopia abandoning agriculture? World Development, 64, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013

- Boafo, J., Appiah, O. D., & Tindan, D. P. (2019). Drivers of export-led agriculture in Ghana: The case of emerging cashew production in Ghana’s Brong Ahafo region. Australasian Review of African Studies, 40(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.22160/22035184/ARAS-2019-40-1/31-52

- Boafo, J., & Lyons, K. (2019). Expanding cashew nut exporting from Ghana’s breadbasket: A political ecology of changing land access and use, and impacts for local food systems. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 25(2), 152–172. https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v25i2.37

- Brooks, K., Zorya, S., & Gautam, A. (2012). Employment in agriculture: Jobs for Africa’s youth. In 2012 global food policy report. IFPRI

- Budds, J. (2004). Power, nature and neoliberalism: The political ecology of water in Chile. Singapore Journal of Tropical Agriculture, 25(3), 322–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0129-7619.2004.00189.x

- Campbell, M. O. (2013). Political ecology of agricultural history in Ghana. Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2013. ProQuest ebrary.

- Catarino, L., Menezes, Y., & Sardinha, R. (2014). Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – Risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop. Sci. Agric, 72(5), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0369

- Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries (CBI)., (2021). The European market potential for cashew nuts, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/processed-fruit-vegetables-edible-nuts/cashew-nuts/market-potential (accessed on 27th June, 2021)

- Chamberlin, J., Yeboah, F. K., & Sumberg, J. (2021). Young people and land. In J. Sumberg (Ed.), Youth and the Rural Economy in Africa: Hard Work and Hazard (pp. 58–75). CAB International.

- Chapoto, A., Mabiso, A., & Bonsu, A. (2013). Agricultural commercialization, land expansion, and homegrown large-scale farmers: Insights from Ghana (Vol. 1286). International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Chauveau, J. P., Colin, J. P., Jacob, J. P., Lavigne, D. P., & Le Meur, P. Y. (2006). Changes in land access and governance in West Africa: Markets, social. In Mediations and Public Policies: Results of the CLAIMS Research Project. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

- Cotula, L. (2007). Changing ”Customary” land tenure system in Africa . Internatinal Institute of Environment and Development (pp. 1–126).

- Evans, R., Mariwah, S., & Antwi, K. B. (2015). Struggles over family land? Tree crops, land and labour in Ghana’s Brong-Ahafo region. Geoforum, 67, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.10.006

- Filmer, D., & Fox, L. (2014). Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Development Forum;. Washington, DC: World Bank and Agence Française de Développement. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16608

- Flynn, J., & Sumberg, J. (2017). Youth savings groups in Africa: They’re a family affair. Enterprise Development and Microfinance, 28(3), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.3362/1755-1986.16-00005

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation, & International Fund for Agricultural Development. (2014). Youth and agriculture: Key challenges and concrete solutions. http://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/en/c/463121/

- Foundation, M. C. (2015). Youth at work: Building economic opportunities for young people in Africa.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census. Preliminary Report. GSS.

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2012). 2010 Population and housing census summary report of results.

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2014). 2010 Population and Housing Census. District Analytical report, Wenchi Municipality.

- Government of Ghana. (2000). Cashew Development Project, Appraisal Report; Accessed at; https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/Ghana_-_Cashew_Development_Project_-_Appraisal_Report.pdf

- Haggblade, S., Hazell, P. B. R., & Dorosh, P. A. (2007). Sectoral growth linkages between agriculture and the rural nonfarm economy. In S. Haggblade, P. Hazell, & T. Reardon (Eds.), Transforming the rural nonfarm economy: Opportunities and threats in the developing world. John Hopkins University Press (pp. 141–182).

- Haggblade, S., Hazell, P., & Reardon, T. (2010). The rural non-farm economy: Prospects for growth and poverty reduction. World Development, 38(10), 1429–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.008

- Hill, P. (1961). The migrant cocoa farmers of southern Ghana, Africa. Journal of the International African Institute, 31(3), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/1157262

- International Nuts and Dried Fruits., (20192020). Nuts &Dried Fruits Statistical Yearbook 2019/2020, Tecnoparc, Spain. https://www.nutfruit.org/files/tech/1587539172_INC_Statistical_Yearbook_2019-2020.pdf

- Kidido, J. K., Bugri, J. T., & Kasanga, R. K. (2017). Dynamics of youth access to agricultural land under the customary tenure regime in the Techiman traditional area of Ghana. Land Use Policy, 60, 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.10.040

- Kutsoati, E., & Morck, R. (2012). Family Ties, Inheritance Rights and Successful Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from Ghana. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper 18080, Cambridge, MA

- Kwapong, O. (2009). The poor and land: A situational analysis of access to land by poor land users in Ghana. J. Rural Commun. Dev, 4, 51–66. https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/134/48

- Logah, F. Y., Obuobie, E., Ofori, D. et al. (2013). Analysis of rainfall variability in Ghana. International Journal of Latest Research in Engineering and Computing, 1(1), 1–8. http://csirspace.csirgh.com/bitstream/handle/123456789/2087/Analysis%20of%20Rainfall%20Variability%20in%20Ghana.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Losch, B. (2016). Structural transformation to boost youth labour demand in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of agriculture, rural areas and territorial development Working Paper No. 204. International Labour Organisation. https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/working-papers/WCMS_533993/lang–en/index.htm

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th) ed.). Sage Publishing.

- Moseley, W. G. (2017). The new Green Revolution for Africa: A political ecology critique. Brown Journal of World Affair, 23, 177. https://bjwa.brown.edu/23-2/the-new-green-revolution-for-africa-a-political-ecology-critique/

- Moseley, W. G., Schnurr, M., & Bezner Kerr, R. (2015). Interrogating the technocratic (neoliberal) agenda for agricultural development and hunger alleviation in Africa. African Geographical Review, 34(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2014.1003308

- Noora, C. L., Issah, K., Kenu, E. et al. (2017). Large cholera outbreak in Brong Ahafo region, Ghana. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2728-0

- Peprah, P., Amoako, J., Adjei, O. P., & Abalo, M. E. (2018). The syncline and anticline nature of poverty among farmers: Case of cashew farmers in the Jaman South District of Ghana. Journal of Poverty, 22(4), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2017.1419534

- Pogucki, R. J. H. (1955). Report on land tenure in Adangme customary law. Gold Coast Lands Department.

- Poulton, C. (2017). What is agricultural commercialisation, why is it important, and how do we measure it? APRA Working Paper 06. IDS, Brightong

- Robbins, P. (2012). Political ecology: A critical introduction (2nd edn) ed.). Wiley.

- Schubert, J. (2005). Political ecology in development research. An introductory overview and annotated bibliography. NCCR North-South.

- Stecklov, G., & Menashe-Oren, A. (2019). The demography of rural youth in developing countries, IFAD - 2019 Rural Development Report, Available SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3519953

- Strijker, D., Bosworth, G., & Bouter, G. (2020). Research methods in rural studies: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. Journal of Rural Studies, 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.007

- Sumberg, J., Fox, L., Flynn, J., Mader, P., & Oosterom, M. (2020). Africa’s ‘youth employment’ crisis is actually a ‘missing jobs’ crisis. Development Policy Review, 38(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12475

- Sumberg, J., Yeboah, T., Flynn, J., & Anyidoho, N. A. (2017). Young people’s perspectives on farming in Ghana: A Q study. Food Security, 9(1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-016-0646-y

- Swyngedouw, E., & Heynen, H. (2003). Urban political ecology, justice and the politics of Scale. Antipode, 35(5), 898–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2003.00364.x

- Tessmann, J., & Fuchs, M. (2016). Loose coordination and relocation in a South-South value chain: Cashew processing and trade in southern India and Ivory Coast. Die Erde. Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin, 147(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-147-17

- Tirkaso, W. T. (2013). The role of agricultural commercialization for smallholder’s productivity and food security; an empirical study in rural Ethiopia. Second cycle, A2E. SLU, Dept. of Economics.