Abstract

In research literature, the terms “small-scale-agriculture” and “smallholder-agriculture” (farming) cannot be clearly distinguished and are frequently used synonymously. Taking terminology of both versions, we examine relationships between textual and bibliographic elements, identify clusters of studies and research accents, as well as developments in time. Using information science methods (big data, bibliometrics/scientometrics, visualization program Vosviewer) in the citation database Scopus, we design Boolean search statement/query (emphasis on proximity operators), analyse terms in titles and abstracts of articles, evaluate author networks (countries, co-authorship), keywords, and links between journals. Authors from developed and developing countries collaborate widely, with the US having the most co-authored articles, Germany having the most diverse current network, and Kenya being the strongest contributor among developing countries. Most articles are published by authors from Africa. There are also two smaller clusters representing Asia and the Americas. Three clusters of research priorities are evident: 1) crop production (current focus: crop yield), 2) livestock production (current focus: diseases), and 3) environmental issues, vulnerability to climate change, sustainability, and socio-economic themes. Future trends (hot topics and research fronts) will increasingly focus on adaptation strategies, food security, gender (women), or human health (at the time of submission, there were already dozens of papers on Covid 19 and smallholder farmers). Many topics that used to be most covered by Agricultural and Biological Sciences (Scopus Subject Area) are now increasingly covered in Social Sciences journals, becoming a complex research field on its own, which should translate into support and funding for such studies.

1. Introduction

Although many authors differentiate between these terms in their works, it is not possible to make a clear distinction between small-scale agriculture and smallholders. Authors may use two different concepts in the same title (smallholder … small family farms; smallholder … small-scale). Such simultaneous usages are even more common in the abstracts. There are many inconsistencies here. Some authors refer to farmers in terms of smallholders and to an agricultural practice in terms of small-scale farming (smallholder farmers … small-scale irrigation) while some others use the opposite denotation (small-scale farmers … smallholder irrigation). It is also possible to find both concepts interchangeably in the same abstract (… small-scale farmers … smallholder farmers; … smallholder production … small-scale agricultural production …). It is even possible to find tautological uses such as “small-scale smallholders”. Therefore, the motivation for this study was to examine the existing prevalence and practical use of these terms and consider both forms of expressions in order to highlight the main accents of studies.

Many authoritative authors have addressed the distinction between small-scale and smallholder agriculture and farming practices so it is not necessary to review the many possible definitions and meanings. A summary of such questions is beyond the scope of even such works that specifically aim to provide an overview of the size and distribution of farms (Lowder et al., Citation2016). Although some conceptual dilemmas have been explored by Cousins (Citation2013) the author acknowledges that there is no clear differentiation of the terms. Inconsistent terminology therefore affects the evaluation of empirical data. Frequently, the focus is on the transition of smallholder to machinery-based agriculture (Mottaleb et al., Citation2017) or the transition from small-scale to large-scale production (Aliber & Hall, Citation2012) with scaling tied to specific geographies, for example, South Africa (Kirsten and Zyl, Citation1998; Thamaga-Chitja & Morojele, Citation2014). When addressing concepts such as large-scale, small-scale, modern, traditional, etc. agricultural practices, authors often emphasize the meaning of these typologies only in specific countries (Pienaar, Citation2013). Detailed methodological analysis can reveal high farm diversity and several different types of smallholder farming systems even within a single country (Alvarez et al., Citation2018; Musafiri et al., Citation2020). For example, farm-level types of smallholdings have been studied to assess sustainability of different cropping patterns in India (Toorop et al., Citation2020), including in terms of adaptations to climate change (Shukla et al., Citation2019) while in Indonesia small-scale dairy farms have been assessed typologically for economic sustainability (Sembada et al., Citation2019).

In the Americas (North, Central and South America), such typologies have been used, for example, to assess nutritional self-sufficiency in Mexico (Novotny et al., Citation2021), to assess smallholder farms in the highlands of Guatemala (Reyna-Ramírez et al., Citation2020) or to categorize the types of smallholding migrant farms in Brazil (Browder et al., Citation2004). The many relevant studies addressing small-scale production and smallholders invariably demonstrate great diversity and complexity of such farming systems. Although these concepts usually refer to developing countries at lower latitudes, they are also used elsewhere. For example, in Ukraine certain former subsistence smallholders have developed small-scale production into a more commercially viable production (Kuns, Citation2017). The different typologies of small-scale farms in the context of the developed world were addressed by Schulman and Garrett (Citation1990).

When it comes to family agriculture, the terms are much fuzzier still. Family farms are sometimes associated with either smallholder or small-scale terms but the scale and classification depend on the specific circumstances in a given country, therefore this study does not address family farms. A particular type of development is characteristic of countries where state or collective (socialist) agriculture used to prevail. In central and eastern Europe, private small-scale agricultural production was in many countries only a part-time occupation and was limited to household plots (Enyedi, Citation1982). Many formerly large socialist collective farms were replaced by small-scale private farms, where smallholding is now organized as family business (Möllers et al., Citation2018). In some former socialist states, the process of original collectivization was not successful. In (former) Yugoslavia (in the case of Slovenia), the main share of agricultural production was provided by small-scale (family) farms (Bojnec & Swinnen, Citation2018).

Let us now review some lexical terminological resources that have specified these terms:

There is no comprehensive definition of smallholders or small-scale agriculture in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. These terms are mentioned only in the cases of some countries. An entry in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (a part of Britannica Academic) provides a synonym for a smallholding: a small farm. We also consulted other peer-reviewed reference works (monolingual dictionaries and thesauri) available in a complete unabridged version by subscription in our department. Collins English Dictionary defines smallholding as “a holding of agricultural land smaller than a small farm”. Similarly, The Macquarie Dictionary defines it as “a holding of agricultural land smaller than an ordinary farm”. The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopaedia mentions smallholdings and small-scale farming in the context of the entry peasant and in the types of farming with reference to subsistence farming.

Some definitions thus refer to a smallholding as a small farm, and some others as “smaller than a small farm”. But how big is then a holding which is called a farm? To get around the conundrum authors sometimes refer to smallholdings invariably as “small farms”.

We look up the associative contexts of these terms (descriptors) in international agricultural thesauri which have played an important role in the compilation of Agris, Agricola, and CAB Abstracts bibliographic databases and have been used by information specialists for the designation of indexing keywords.

Agrovoc (Agris)

Descriptor: smallholders (included in small farms)

Used for: peasants, small farmers, small holder farmers, smallholder farmers

Descriptor: small scale farming

NAL Agricultural Thesaurus and Glossary (Agricola)

Descriptor: small-scale farming (Narrower Term: peasant farming)

Used for: small-holder farming, small-scale agriculture, small holder farming, smallscale farming, smallholder agriculture, smallholder farming

Narrower Term: peasant farming

Descriptor: small farms

CAB Thesaurus (CAB Abstracts)

Descriptor: smallholders

Descriptor: small farms. Used for: smallholder farms

The labels denoted as descriptors are the recommended terms. The labels denoted as “Used for” are non-preferred terms (non-descriptors). There is evidently not much agreement with regard to smallholder and small-scale. In Agrovoc, there is a distinction between different types of systems with the scope note that the definition of smallholders differs between countries and between agroecological zones according to FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, (Higgins & Kassam, Citation1981). In the USDA’s NAL Thesaurus, the term small-scale farming stands for smallholders and small-scale alike. In NAL Thesaurus, there is also a narrower descriptor peasant farming. In CAB Thesaurus, there are smallholders which stand for all small-scale types of agricultural production.

In the research literature, we assessed the concomitant occurrence of small-scale-related terms as well as smallholders (including variants such as smallholder, small holders, smallholdings) in the same abstract. Here, bellow we present a few selected contexts without providing a citation as these are only examples of terminological usage:

AB: … help small-scale farmers improve … can improve smallholder farmers’ …

AB: … small-scale farmers in developing countries … among smallholder aquafarmers …

AB: … strategies that smallholder farmers employ … support small-scale farmers …

AB: … at the expense of smallholder agriculture … products of small-scale agriculture …

There were also many documents where authors employed small-scale in abstracts while they used the term smallholder in keywords (KW), or vice versa. It is obvious that many authors in practice do not put much attention on the differentiation:

AB: … is dramatically affecting small-scale farming productivity …

KW: Smallholder agriculture

AB: … cash crops that support the livelihoods of small-scale farmers …

KW: Smallholders

AB: … developing countries, with profound implications for smallholder farmers … .

KW: Small-scale farmers

AB: … fifty smallholder farmers in northern Tanzania

KW: Small-scale farmer

The above examination of lexical usage in glossaries (academic dictionaries, thesauri) serves as an additional terminological motivation and background for our study, which explores the contexts in which the authors employ such terms.

Given the fact that authors use several different terms for similar concepts, we would like to find out how often these combined terms occur in practice in the citation database Scopus. By selecting terms in a carefully constructed search syntax (search statement or query), we thus aim to find out how articles address the topics of small-scale agriculture and smallholders.

How and where can these patterns be explored? These configurations are reflected in the co-authorship by country of authors, and in the keywords used by authors. The text in the titles and abstracts of articles reveals subject content and research directions of such studies even more precisely. Complementing this, journals of authors’ preference can also provide information on publication trends. Research patterns and time-scaled trends can be revealed using complex visualizations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection, methodological introduction

The focus of this study was thus to find out in which contexts do the authors use the concepts smallholder and small-scale in relation agriculture (farming). There are thousands of such papers, even if only titles are browsed, and many more papers in which such terms occur in the abstracts. We have used Scopus database (Elsevier), which has indexed a wide range of international, regional and national journals over a long period of time. This is particularly relevant to the social sciences, which have been covered by Scopus consistently. We evaluated research articles in journals up to the end of 2020. Retrieval is based on the titles of the articles which represent a primary focus of an article and provide the information for the general content scope of an article. Using similar methods and databases, authors also point out limitations, such as the selection of the time period, Boolean search strategy, choice of document types, the software for an analysis, and the source database (Fomina et al., Citation2022; Putera et al., Citation2022). Although we did not find studies that address the topic of our study with such methods at such a scale, we can point to a few studies that use similar methods in different areas of agriculture. We noticed small farms, small-scale agriculture and smallholders in bibliometric studies dealing with development studies (Madrueño & Tezanos, Citation2018) or small (family) farms and agricultural entrepreneurship (Dias et al., Citation2019). Other agricultural topics in connection with our methods will be reviewed in the Results section.

2.2. Selection of search terms and search statements

The first phase in the methodology consisted of an evaluation of the terminology and the selection of the optimal search terms. Our search statements needed to include terms that best apply to smallholder and small-scale-related farming and agriculture. Given the different position of these terms in a sentence, the compound forms were also considered. The careful construction of the search statement (search query) is very important as it has a strong influence on the precision of retrieval and recall of the records and affects subsequent visualizations. In order to capture the real primary contexts, we only considered the occurrence of these terms in article titles.

The characteristics of the terms were first investigated. The term smallholder is written as a compound noun, but there are other possible forms: small holder, small-holders, smallholdings, small holdings etc. Small-scale was written with a hyphen, in most cases. A compound form smallscale occurred very rarely, mostly in old documents, so it was not relevant for further evaluation.

Smallholder is consistently associated with agriculture/farming, so no further descriptive noun was required. Small-scale can be more freely associated with agriculture/farming (not necessarily as a phrase), so we allowed some distance between words using proximity operator PRE/2, where proximity /2 denotes up to two other words between two studied terms. On the other hand, if the two terms were too far apart, the meaning would too often not match the search criteria. In our preliminary test-searches, we found that a distance of up to two words (PRE/2) was optimal.

At small-scale we therefore linked our search statements also with farm* and agricultur*. The term small-scale alone would return far too many unrelated results (e.g., small-scale turbojet, small-scale mining, small-scale wind turbines). We may have lost a few relevant documents but otherwise the results would be clogged by thousands of unrelated articles. The trade-offs of a search query (search precision vs. retrieval recall) exists as a limitation in any bibliometric study.

Based on the terminological pilot searches we arranged the search statements into subdivisions (Table ). Wildcard (asterisk) represents right-hand truncation. For example: smallhold* retrieves smallholder, smallholders, smallholding, smallholdings.

Table 1. Search statements used for the retrieval of articles in Scopus (up to and including 2020)

The Boolean union (≈5,100 articles) is based on search operator OR. It is effectively a sum of the above two statements as authors almost never use both terms in the same article title. There were, however, a few exceptions (e.g., … “management by small-scale dairy farmers … smallholder adoption … ”; “small scale farmers … small holder oil palm … ”).

Examples of PRE/2 proximity (two words between the two principal terms)

Small scale commercial broiler farms … Bangladesh

Small-scale crop livestock farmers … Limpopo province

Czech small-scale beef cattle farming …

Small-scale mining and agriculture … Jukumani Indians

Small scale farmers’ indigenous agricultural … Cameroon

The terms smallhold* OR “small hold*” do not require an additional operator as these concepts are invariably related to agriculture or farming and therefore stand on their own; some examples:

Smallholder dairy cattle management … southern Mozambique

Cocoa and oil palm smallholders in Ghana

Small holders’ cassava … South-west Nigeria

Broilers kept on small holdings … Cameroon

Smallholding land uses … southern Ethiopia

2.3. Analysis, processing, and visualizations

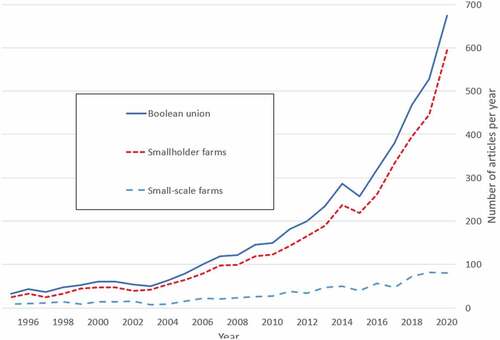

The first (introductory) analysis (Growth of literature) was performed by downloading the records into experimental batches. This preliminary analysis addresses the annual growth of articles based on the totality of records (Boolean union), as well as the annual growth of records retrieved by two separate search statements in Table (smallholder-based terms, and small-scale-based terms). In Figure , these groups are designated as Smallholder farms and Small-scale farms.

Description of variables, parameters, and data threshold for visualizations

Subsequent analyses involve complex visualizations using the VOSviewer program. The techniques and procedures are explained in the latest package of the program (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020). Some similar procedures based on this program were used by Hocevar and Bartol (Citation2021). Further, relevant works using this program are presented throughout the Results section.

Our visualizations use default parameters in order to facilitate repeatability of the experiment for the purposes of follow-up studies. The labels (countries, keywords, text data, and journals) are presented by lines and circles (default). Maps are based on network visualization (number of clusters by default) as well as overlay visualization (time component) for those same clusters. In the overlay visualization, we use the Coolwarm spectrum which is one of the predefined overlay colour values by the program. All visualizations use Full counting method. It means that each item has the same weight and is not fractionalized.

In the first visualization analysis (Authorship by country) the Type of analysis was co-authorship, while countries were used as the Unit of analysis. The analysis focuses on authors’ countries based on an author’s institution address (which contains the information for the country). We have considered the default number of countries, in this case five.

The second visualization deals with the keywords assigned by the authors. The type of analysis Co-occurrence is thus based on the unit Author keywords. This analysis was carried out according to the overlay principle (time component). Again, the default threshold of five was chosen. In order to examine the comprehensive occurrence of terms referring to either small-scale or smallholder-related terms, we prepared a thesaurus to merge the near-synonyms into related groups. A thesaurus to merge different variants of names is also proposed by the authors of the program (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2020). The items thus grouped together are presented in detail in section.

The third group of visualizations is based on text data. It examines the network expressed as clusters of terms in the titles and abstracts of the articles. Again, the standard default threshold for occurrence (in this case 10) is used, based on default clusters. The only divergence from the default parameters is a thesaurus for terms that occur frequently in structured abstracts and have no subject-specific meaning. The authors of the program advise that one might want to ignore the terms with such general meanings. We have therefore used the thesaurus to exclude “generic” phrases in abstracts, for example, “design methodology approach”, “main objective”, “originality value”, article, paper, research study, work.

The fourth visualization (Network of journals) looks at the journals in which the authors published their research. The analysis is based on Bibliographic coupling where Sources (in our case journals) are used as a Unit of analysis. We again employed the default threshold, which was in this case is five documents per source. The visualization is based on Network presentation (default number of clusters) and complemented by Overlay parameters (Coolwarm as predefined colours)

The procedures and numbers of items under each analysis are explained and discussed in the four subsections of the results in the direct context of each subsection.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Growth of literature

The introduction to the results presents annual increase in articles using the search statements presented in Table . The usage of the term smallhold* is much more frequent (Figure ). Articles using this concept have over the past decade increased much more quickly than small-scale-related which have grown more modestly. The Boolean union presents the union of both terms (using search operator OR—either of both terms).

3.2. Visualizations

3.2.1. Authorship by countries

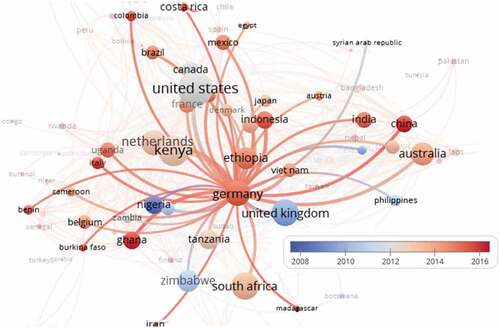

These calculations are based on country data in an author’s address field which is linked to an author’s institution (affiliation). Table lists countries by the preference for the term used, either smallholder or small-scale (first 20 countries in each group). For example, in South Africa, the term small-scale has more weight than in other countries, relatively. Among the “developed” countries, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, and France are the top contributors (in terms of co-authorship). Similar top rankings were also found for irrigation in agriculture (Jusoh et al., Citation2021) and coffee (Cabrera et al., Citation2020). These countries were also ranked highly in a scientometric study on urban agriculture (Pinheiro & Govind, Citation2020).

Table 2. Countries (authors’ address) by the type of agricultural/farming system

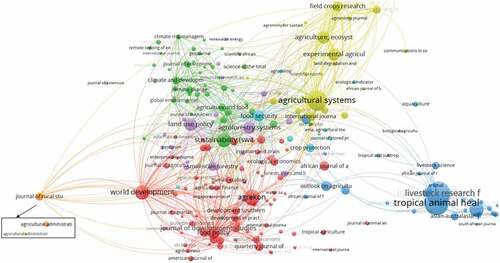

The links in Figure are built on the Boolean union of 5,100 articles (explained at Table ). The countries are assigned into clusters according to the similarities of the average links. The size of the circles indicates the number of documents. Only the countries with at least five documents are shown (default threshold). Of the more than 190 countries, 90 met this threshold. Countries are drawn towards clusters (shown with different colours) in which they have the strongest links. Links to countries in other clusters also exist and are represented by lines. The names of some countries are blurred or cannot be displayed due to overlap in the very data-rich visualization maps (such limitations exist in all similar studies). Figure shows some characteristic patterns: the United Kingdom has strong links, for example, with eastern and southern Africa. Germany’s connections are very diverse (position in the centre of the map), branching out in all directions. Ethiopia’s links are very diverse so Ethiopia is drawn to several different clusters. Kenya is also located quite centrally due to strong links with countries in different clusters (although closer to African countries). Most African countries are located in the lower-left part of Figure indicating high similarity of authorship and research topics in these countries. There are separate clusters of countries (mostly) in the Americas and Asia. Such authorship clustering based on proximity is somewhat self-explaining and has also been found in other studies, which address collaboration based on geography or geopolitics, the case of ASEAN countries, for example, (Quoc Bui et al., Citation2021).

Figure 2. Connections between countries (by co-authorship) relating to smallholders and small-scale farms.

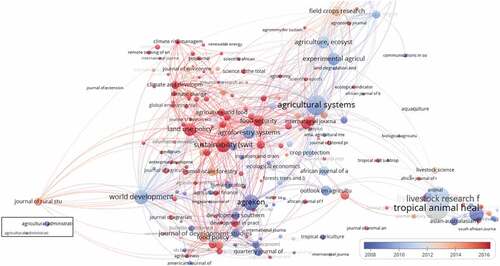

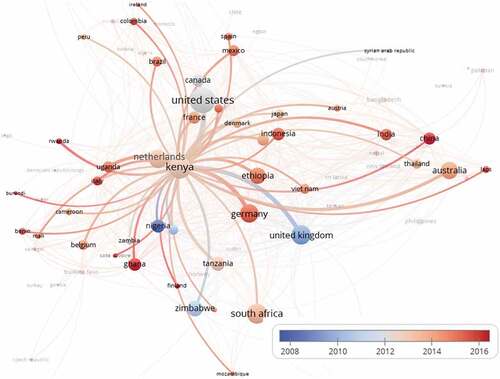

In continuation, we assess time scale (time gradation) of average publication by these countries (Figure ). While the circle size again denotes the number of documents, the colours now represent average time. We can observe that although the US co-authored the highest number of articles (grey circle which is the largest), the articles by Germany are on average much more recent (red shaded colours).

Figure 3. Connections between countries (by co-authorship) relating to smallholders and small-scale farms shown in time gradation.

We therefore show a detailed example of Germany (Figure ) which is noteworthy considered that Germany possessed fewer historical geo-political links with developing countries. It nevertheless exhibits very diverse connections. Germany co-authored 19 articles with Ghana while UK co-authored 16. Ghana exhibits very recent average publications (dark red colour). Very strong connections between German institutions and African countries were already identified in a study dedicated precisely to collaboration in Africa (Pouris & Ho, Citation2014), and also in a study on food security (Xie et al., Citation2021) and research on sleeping sickness, while the German cooperation in the research on Leishmaniasis was very strong with all continents (Bender et al., Citation2015). The contribution of UK (as of 2020) is still higher (larger circle) but is on average also older (blue shade), while the participation of Germany is increasing. In 2020, Germany contributed more articles than UK.

Figure 4. Time gradation of Germany’s connections (by co-authorship) relating to smallholders and small-scale farms.

A similar distribution of African and European countries was also found by Barasa et al. (Citation2021) in the study on climate-smart agriculture research in Africa who also detected Kenya as the strongest contributor, followed by South Africa and Zimbabwe. Kenya and South Africa were also identified as such in a study on food security (Xie et al., Citation2021). South Africa is a case apart. It places strong accent on small-scale farms, on account of specific agricultural structure. We also highlight the connections of researchers based in Kenya (Figure ) which is the strongest contributor from Africa in our study. Cooperation is very diverse. Researchers co-operate not only in Africa and Europe but also with Australia, Asia and the Americas. Here, we can mention that Nairobi hosts some important agriculture-related international organisations.

Figure 5. Time gradation of Kenya’s connections (by co-authorship) relating to smallholders and small-scale farms.

While no effective disambiguation is possible between the smallholder and small-scale concepts in the context of developing countries, we need to indicate that these two concepts are sometimes also used in the context of the developed countries, although rarely. We present a few such examples:

-Between smallholder traditions and “ecological modernisation” … Austria

-A system dynamics approach … smallholder farming in the UK

-Looking under the canopy: Rural smallholders … Appalachian Ohio

-Seasonal variations in raw milk … small-holder dairy farms in Croatia

-The gender division of labour: The case of Tuscan smallholders

-Comparison … Austrian small-scale dairy farms and a Slovakian large-scale farm

-Seasonal variations … eggs from a Polish small-scale farm

-Landscape configurational heterogeneity by small-scale agriculture … in western Europe

-Natural believers … small-scale farming in France

-Mobile poultry processing … small-scale farmer in the United States

3.2.2. Keywords assigned by authors

In this analysis, our experimental database was processed for the assessment of authors’ preference for keywords. Authors can use different keywords to represent essentially the same concepts, such as smallholders, smallholdings or smallholder farming. Thus, the concepts can be written in plural, singular, as a compound with or without a hyphen etc.

We provide selected examples of authors’ preferred keywords:

Smallholder-based:

smallholder farmers (268), smallholders (250), smallholder (213), smallholder agriculture (53), smallholder farmer (45), smallholder farming (41), smallholder farms (34), smallholdings (15), smallholder farm (7), smallholder production (5), small holder (7), small holders (7), etc.

Small-scale-based:

small-scale farmers (65), small-scale farming (34), small scale farmers (15), small farms (10), small-scale agriculture (9), small-scale farms (9), small-scale farmer (8), etc.

Above, we have enumerated the keywords in the original set up, exactly as they come about in bibliographic records. Namely, very precise programs will treat the hyphenated “small-scale” independently of “small scale” and will perceive the two as two different entities (also smallholders and small holders, for that matter). All these forms impact visualization computations as each is attributed a distinct value. The visualization map soon gets cluttered with too many (synonymous) items and is no longer coherent.

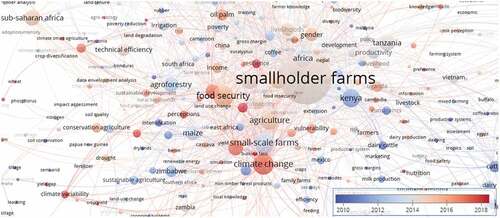

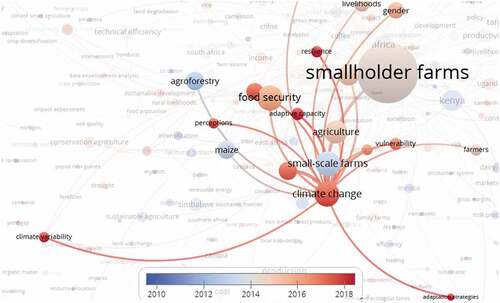

To compensate for this limitation, we set up a thesaurus to merge the synonymous forms of the above-mentioned concepts smallholder and small-scale. To further reduce the synonyms and clutter in the map, we have also conflated the terms related to family farms (family farm, family farmer) and small farms (small farm, small farmer), which we have mapped to common denominators family farms and small farms. However, these terms are rare. The map shows the network of connections (Figure ). Smallholder-related are much more frequent than small-scale. Small-scale-uses are also older, on average (blue shades). The network contains almost 10,000 keywords. Only about 600 of them are displayed that occur at least five times (default). Authors also use “random” keywords which can occur only once in in one single article. These are usually specific terms of geographic or taxonomic nature.

The map in Figure is presented by way of time gradation (on a time scale of average occurrence of keywords) where it is possible to discern certain characteristics, most notably the occurrence and frequency of more recent terms (“hot topics” or “trending topics”). As almost expected, the topic or keyword climate change stands out quite conspicuously.

To this end, we now present the network of connections more specifically only for climate change (Figure : a zoomed-in excerpt of the applicable part of Figure ). Given the size and colour of the circle (red) it is both recurrent and recent. It comes about 170 times. Figure shows only the strongest connections, for example, with adaptive capacity, food security, resilience, vulnerability. All these are issues of recent importance (red-palette shades).

Figure 7. Time gradation of connections between author keywords: principal connections for climate change (Excerpt from Figure ).

Analysis of keywords arranged according to Vosviewer and based on Scopus data were also used in mapping blockchain technology in food and agriculture industry (Niknejad et al., Citation2021), watershed governance (Widianingsih et al., Citation2021) and in assessing urban agriculture (Pinheiro & Govind, Citation2020) although the datasets of those studies were smaller. Keyword connections between climate change and smallholder agriculture were noticed in study on the current trends in climate change (Nalau & Verrall, Citation2021). Recent links between food security and climate change were also noticed by Sweileh (Citation2020) and Xie et al. (Citation2021). We can here mention that we detected few keywords to the end of environmental protection, in the sense of mitigating risks which the farming itself presents to environment although such accents were noticed, for example, in a study related to sustainability and rural communities (Zárate-Rueda et al., Citation2021). Ota et al. (Citation2018) also tackled issues of mitigation, on the case of a study on reforestation. It seems that in small-scale agriculture studies the risks of climate change to vulnerable small holdings presents an immediate matter of concern and has therefore priority over environmental protection. There are also growing recent links between smallholder agriculture, climate change and gender, a recent keyword which is also notable in the Figure. Such links are being more comprehensively addressed only recently (Phiri et al., Citation2022).

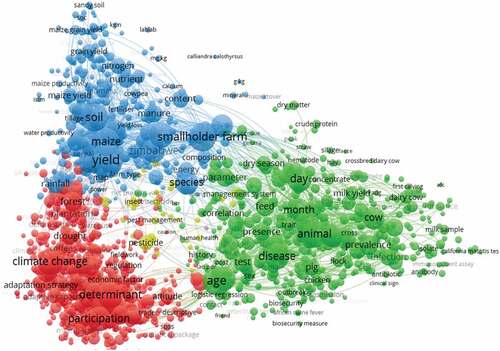

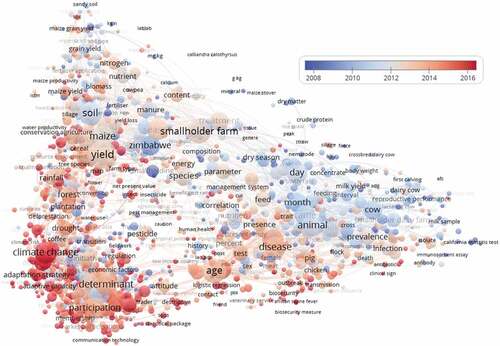

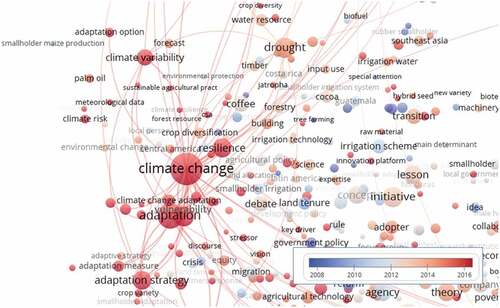

3.2.3. Links of text data: terms in titles and abstracts

We now examine the studies in terms of specific research directions which are represented by words and noun phrases identified by the program in the text data (sequenced from the titles and abstracts of the articles). Default values and default thresholds (10 occurrences) were used, resulting in more than 88,000 different terms extracted from the 5,100 research articles. Figure shows the terms that were designated as relevant by the program according to the algorithms. Using the thesaurus, we excluded some common (general) terms in structured abstracts (e.g., “design methodology approach”, “main objective”, article). This is explained in the methodology section. The terms are arranged in clusters based on the relatedness of concepts (themes or subject matter) in the articles. It should be noted again that there is a strong overlap due to the very high number of terms. Only selected terms can be shown.

Each cluster in the map has some specific characteristics. The upper blue cluster shows facets of crop production. One important theme here is yield, which is easily understood. Yield was also identified as the most important in a mapping study on food security (Sweileh, Citation2020). Maize is the most important crop in this cluster. Wheat is a globally important crop and has also been investigated in bibliometric studies (Yuan & Sun, Citation2020). In our analysis, maize is followed by grain, bean, legume, cereal, sorghum, cowpea, etc. In this cluster, there are also references to yield losses. Losses have also been bibliometrically investigated by way of visualizations (Priyadarshi et al., Citation2020).

The green cluster is associated with animal husbandry. Here, cattle, cow and milk are by far the most important terms, followed by pig, goat, sheep, chicken, etc. Important issues relevant in animal production are health-related, for example, disease, infection and mortality. The network of links between cattle and diseases was visualized by Bigras-Poulin et al. (Citation2006) who used software Pajek (Batagelj & Mrvar, Citation2004). Employing Vosviewer, Hossain et al. (Citation2015) evaluated zoonotic research while Freire and Nicol (Citation2019) evaluated animal welfare. At this point we can mention that some fields of an increasing agricultural importance are very much interdisciplinary, for example, biotechnology, which was bibliometrically investigated by De la Vega et al. (Citation2015).

The bottom red cluster in our study is heterogeneous and does not relate to a particular agricultural production. Climate change issues are here particularly notable. The position of the items and lines indicates that some issues are more related to crop production and others to animal production. The upper red items such as forest, plantation and drought are clearly drawn towards the upper blue cluster (crops), while the lower terms are more associated with animal production. It is evident that climate change is a more pressing issue in the cultivation of crops. Indeed, researchers have already identified climatic references to crops using the visualization software CiteSpace (Yang et al., Citation2018).

The next map (Figure ) complements the map in Figure by providing insight into the trends on time-scale. For example, the time scale shows recent major issues in animal health (disease, biosecurity, outbreak). As with the keyword assessment in Figure , climate change issues are very recent.

Among these novel (red shades) topics are also very recent terms such as market information, communication technology, mobile phone, ICT, which are all located at the very bottom of the map. Most are still small and overlapping and cannot be seen unless zoomed in. Recent importance of ICT literacy in relation to smallholder farmers was noted by Alant and Bakare (Citation2021) as well as Onyancha and Onyango (Citation2020) in a bibliometric study on sub-Saharan Africa. In general, such technologies have been shown to substantially improve security of smallholder farmers (Ankrah Twumasi et al., Citation2021).

In Figure we now present a more detailed zoomed-in lower left part of Figure . Most cash crops and related produce (cocoa, cotton, coffee, oil palm, rubber) are all located in this part of the map, although not all are visible. Cash crops have been shown to have an important role in in food security. This is especially crucial bearing the climate change-related issues in this kind of agricultural production (Kuma et al., Citation2019). Some of these crops have also been studied in bibliometric and visualization studies based on Vosviewer, e.g., cocoa (Hernandez & Granados, Citation2021), coffee (Cabrera et al., Citation2020) and cotton (Stopar et al., Citation2021). Outside of this map-excerpt but still in the same cluster there are several forestry-related concepts. Bichel and Zanin (Citation2021) also addressed recent links between forests and climate-related issues (e.g., carbon sequestration) in a science mapping study.

Figure 10. Time gradation of connections between terms in abstracts and titles: part of the map in connection with climate change.

Just as is the case of author keywords, recent accents of climate change are also expressed in titles and abstracts in the terms such as adaptation, adaptation strategy, drought, resilience or vulnerability. Many of these terms appear in more than 100 articles each. Such connections between crops, adaptation, vulnerability were also noticed in a visualization by Di Matteo et al. (Citation2018). Jusoh et al. (Citation2021) used Vosviewer visualization in assessing the field of irrigation and pointed out the importance of efficient management of water resources. The importance of sustainable water management was also stressed in a bibliometric study by Olusanmi et al. (Citation2021). We can underline the recent concepts related to sustainability which are mostly located in the lower left part of Figure (red cluster). Given the strong overlap, we itemize a few of the more frequent items: agricultural sustainability, environmental sustainability, sustainability standard, sustainable agricultural practice, sustainable development, sustainable intensification, sustainable land management, sustainable livelihood, sustainable palm oil.

The recent emergence of climate change and sustainability was noted, for example, in bibliometric research on urban agriculture (Pinheiro & Govind, Citation2020). Recent accents in sustainable rural development were also noticed in a visualization study by Bartol et al. (Citation2022). Sustainability was also assessed in a specific narrower focus, for example, in a study that used mapping to identify different research approaches (Weltin et al., Citation2018). Most of these circles are small as the many related concepts are still evolving and not visible in the map unless zoomed-in.

One such recent example are gender issues, especially the terms referring to women. The growth of such terms has been sharper than the total yearly growth of records. While in 2010 there were 11 articles specifically addressing women and/or gender in the scope of smallholders, in 2020 there were more than 60. Age as a demographic factor shows even more occurrences, and the accents are also very recent (red shaded colours in Figure ).

Finally, we also need to mention the recent surge of articles which address the impact of Covid-19 pandemic (coronavirus) on smallholder farmers (for example, Rukasha et al., Citation2021). We can here provide only some exploratory indication. As of September 2022, there were a few dozen articles on Covid-19 pandemic with a major reference to smallholder or small-scale agriculture. Such papers articles are, however, not analysed in this study as the number of articles is still increasing with every new batch added to the database. Using visualization methods, this will only be able to be more comprehensively analysed after some time lapse. It is likely that there will be substantial parallels with climate change as the disruptions caused by major epidemics share many similarities with natural disasters (Spitalar & Hocevar, Citation2021). We intend to pursue the developments of social issues and human health in our future research.

3.2.4. Network of journals

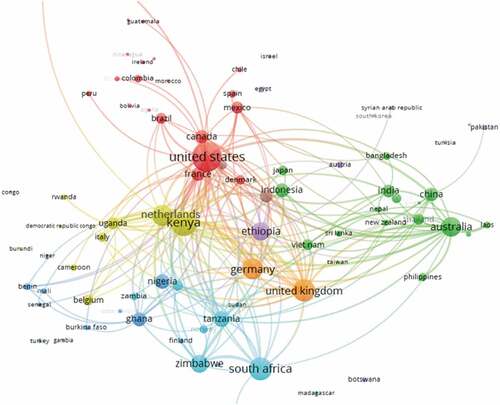

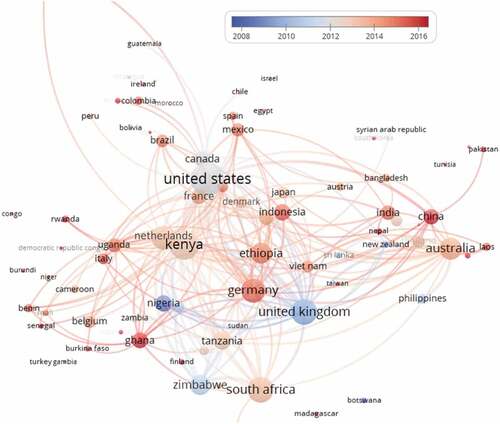

At the end, we evaluate the network of more than 1,200 journals in which the articles were published. The network is ordered by the links between journals based on shared references in an article. Figure and the corresponding Figure (scaled in time) show about 220 journals that published at least five articles each. This was the default threshold of the visualization program in this case of bibliographic coupling. The lines again show the strength of links between journals (journal names are truncated by the program). Four relatively compact clusters were found (green, yellow, dark blue, red). These cluster represent well-defined networks of shared citations. There are also purple and light-blue clusters whose journal are located in the centre of the map, and intermingle, indicating higher interdisciplinarity of such journals. The Journal of Rural Studies is in a league of its own, most closely linked with the journals Agricultural Administration and Agricultural Administration and Extension. As a reference, Widianingsih et al. (Citation2021) identified eight clusters of related publications in a study on watershed governance (on a smaller data set).

The maps in Figures are fairly informative and need no lengthy recapitulation. Perhaps, we can highlight a few principal observations (referring to Figure ).

Green cluster is associated with environmental studies more in general (leading journals: Sustainability (Switzerland) Climate and Development, Agriculture and Food Security, Acta Horticulturae, Climatic Change)

Yellow cluster shows accents of crop science and ecosystems (Agricultural Systems, Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, Experimental Agriculture, Field Crops Research, International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems)

Blue cluster is strongly associated with animal production and veterinary medicine (Tropical Animal Health and Production, Livestock Research for Rural Development, Preventive Veterinary Medicine, Outlook on Agriculture, Plos One)

Red cluster (the second) has a strong relationship with agricultural economics and development studies (Agrekon, World Development, Food Policy, African Journal of Agricultural Research, Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, Journal of Agricultural Economics)

The name of a journal does not automatically lead it to be assigned to a particular cluster. It only suggests that a journal shares similar references more often with certain journals. While the ubiquitous “meta” journal Sustainability was detected as a chief journal in many general scientometric studies, some other major journals from our map were more specifically detected in specific studies, for example, World Development in a bibliometric mapping study on coffee (Cabrera et al., Citation2020), the Journal of Rural Studies in a study on rural development (Lu & de Vries, Citation2021). Agroforestry studies have also received attention in science mapping. Journal Agroforestry systems was identified as the most important journal by Ota et al. (Citation2018), who also looked at smallholder issues, and by (Bichel & Zanin, Citation2021).

Finally, we would like to discuss the average timing of article publication (Figure ). The journals dealing with environmental studies and social issues (green cluster in Figure ) all have a very recent publication history, as indicated by the shading of the red colour palette. Similar findings were also reported by Kremmydas et al. (Citation2018) in a study of agricultural policy. These patterns show an increasing linkage between social topics, environment, climate change and adaptation strategies, all in the context of smallholder (small-scale) agriculture. In terms of journal classification (Scopus Subject Areas) we noted a conspicuous feature. While in 2010 there were still three times as many articles published in the category Agricultural and Biological Sciences as in the Social Sciences journals, the latter has recently accounted for more than two-thirds in relation to the former. Very similar patterns can be observed in the most recent articles which address Covid-19 and smallholder farmers. Social Sciences are again the second strongest subject area, just after Agricultural and Biological Sciences and before Environmental Science. Perhaps even more notably, articles addressing both smallholders and Covid are very rarely covered in the Scopus subject area of Medicine. We intend to investigate this in our future research.

4. Conclusion

Developments in smallholder and small-scale agriculture have been studied many times. Authors have repeatedly pointed out that concepts and definitions are very much influenced by types of production, agro-ecosystems, regions, countries, and even continents. To explore the practical context of these concepts in the articles, we have taken the approach of bibliometric clustering and mapping of a large corpus of data to identify and compare research fronts in the field.

In the scholarly literature, there is no effective distinction between the concept smallholder and small-scale farming. Many authors use these concepts interchangeably in the same abstracts, or use one concept in the abstract and another in the title or keywords. Usage may also depend on the preferred terminology in a country. However, terms referring to smallholders are used more commonly and also more recently. They are most associated with countries in Africa, although they can also be found in other geographic areas. The articles are characterised by very active international cooperation between developing and developed countries, with some particular recent developments. For example, the contributions and variety of collaborations by German authors have increased greatly in the recent past.

In general, research on smallholder agriculture is conducted in three main domains, which can be clearly distinguished (referred to in the visualization program as three clusters of research directions). Crop production and animal husbandry are two “traditional” areas. Here, current research priorities can be identified the areas of crop yield and animal health. The third area is more diverse and is strongly influenced by environmental topics. It is also the most recent and reflects the current shift in research priorities to problems exacerbated by global warming. This is evident from concepts in the titles and abstract, as well as from the keywords used by the authors. Recently, terms such as adaptation, adaptive capacity, climate change, food security, gender, sustainability, vulnerability, etc. have taken centre stage.

This shift of attention is also evident when looking at the subject areas of the journals (according to the classification of the Scopus database). While agricultural and biological sciences are still the most important subject areas of the journals, the social sciences have increased very strongly recently.

In summary, research on smallholder and small-scale agriculture is increasingly dominated by social issues and has been taken up by the social sciences, even in the area of human health. Environmental concerns in this context are now emerging as a complex matter in their own right. We intend to explore this ever-expanding network of studies in our future research.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Nevena Alexandrova-Stefanova, and Sophie Treinen of the

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, as well as Laszlo Papocsi and Marcel Kováč for inspiration and support of e-agriculture strategies. And special thanks to Michal Demes, my long time inspiration in agricultural information networking.

Disclosure statement

There are no financial or non-financial competing interests to report in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alant, B. P., & Bakare, O. O. (2021). A case study of the relationship between smallholder farmers‘ ICT literacy levels and demographic data w.r.t. their use and adoption of ICT for weather forecasting. Heliyon, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06403

- Aliber, M., & Hall, R. (2012). Support for smallholder farmers in South Africa: Challenges of scale and strategy. Development Southern Africa, 29(4), 548–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.715441

- Alvarez, S., Timler, C. J., Michalscheck, M., Paas, W., Descheemaeker, K., Tittonell, P., Andersson, J. A., Groot, J. C. J., & Puebla, I. (2018). Capturing farm diversity with hypothesis-based typologies: An innovative methodological framework for farming system typology development. PLOS ONE, 13(5), e0194757. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194757

- Ankrah Twumasi, M., Jiang, Y., Asante, D., Addai, B., Akuamoah-Boateng, S., & Fosu, P. (2021). Internet use and farm households food and nutrition security nexus: The case of rural Ghana. Technology in Society, 65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101592

- Barasa, P. M., Botai, C. M., Botai, J. O., & Mabhaudhi, T. (2021). A review of climate-smart agriculture research and applications in Africa. Agronomy, 11(6), 1255. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11061255

- Bartol, T., Cernic-Istenic, M., Stopar, K., & Hocevar, M. (2022). Rural areas, rural population, and rural space in central Europe (JCEA countries): Research visualization in scopus and web of science. Journal of Central European Agriculture, 23(1), 246–260. https://doi.org/10.5513/JCEA01/23.1.3428

- Batagelj, V., & Mrvar, A. (2004). Pajek—Analysis and visualization of large networks. In M. Jünger & P. Mutzel (Eds.), Graph Drawing Software (pp. 77–103). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-18638-7_4

- Bender, M. E., Edwards, S., von Philipsborn, P., Steinbeis, F., Keil, T., Tinnemann, P., & Yamey, G. (2015). Using co-authorship networks to map and analyse global neglected tropical disease research with an affiliation to Germany. Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(12), 0004182. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004182

- Bichel, A., & Zanin, E. (2021). Perspectiva de ‘bem-estar único’ em sistemas agroflorestais - Uma análise bibliométrica. Uniciências, 25(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.17921/1415-5141.2021v25n1p26-32

- Bigras-Poulin, M., Thompson, R. A., Chriel, M., Mortensen, S., & Greiner, M. (2006). Network analysis of Danish cattle industry trade patterns as an evaluation of risk potential for disease spread. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 76(1), 11–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2006.04.004

- Bojnec, Š., & Swinnen, J. F. M. (2018). Agricultural privatisation and farm restructuring in Slovenia. Agricultural Privatization, Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in Central and Eastern Europe, 281–310. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429450228-8

- Browder, J. O., Pedlowski, M. A., & Summers, P. M. (2004). Land Use Patterns in the Brazilian Amazon: Comparative Farm-Level Evidence from Rondônia. Human Ecology, 32(2), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HUEC.0000019763.73998.c9

- Cabrera, L. C., Caldarelli, C. E., & Gabardo da Camara, M. R. (2020). Mapping collaboration in international coffee certification research. Scientometrics, 124(3), 2597–2618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03549-8

- Cousins, B. (2013). Smallholder Irrigation Schemes, Agrarian Reform and “Accumulation from Above and from Below” in South Africa. Journal of Agrarian Change, 13(1), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12000

- De la Vega, I., Requena, J., & Fernández-Gómez, R. (2015). The colors of biotechnology in Venezuela: A bibliometric analysis. Technology in Society, 42, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2015.03.007

- Dias, C. S. L., Rodrigues, R. G., & Ferreira, J. J. (2019). Agricultural entrepreneurship: Going back to the basics. Journal of Rural Studies, 70, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.06.001

- Di Matteo, G., Nardi, P., Grego, S., & Guidi, C. (2018). Bibliometric analysis of Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment research. Environment Systems and Decisions, 38(4), 508–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-018-9687-4

- Enyedi, G. (1982). Part-time Farmig in Hungary. GeoJournal, 6(4), 323–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00240533

- Fomina, Y., Glińska-Neweś, A., & Ignasiak-Szulc, A. (2022). Community supported agriculture: Setting the research agenda through a bibliometric analysis. Journal of Rural Studies, 92, 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.04.007

- Freire, R., & Nicol, C. J. (2019). A bibliometric analysis of past and emergent trends in animal welfare science. Animal Welfare, 28(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.7120/09627286.28.4.465

- Hernandez, C. E., & Granados, L. (2021). Quality differentiation of cocoa beans: Implications for geographical indications. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 101(10), 3993–4002. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.11077

- Higgins, G. M., & Kassam, A. H. (1981). The FAO agro-ecological zone approach to determination of land potential. Pedologie, 31(2), 147–168.

- Hocevar, M., & Bartol, T. (2021). Mapping urban tourism issues: Analysis of research perspectives through the lens of network visualization. International Journal of Tourism Cities, [Early Access], 7(3), 818–844. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-05-2020-0110

- Hossain, L., Karimi, F., Wigand, R. T., & Crawford, J. W. (2015). Evolutionary longitudinal network dynamics of global zoonotic research. Scientometrics, 103(2), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1557-y

- Jusoh, M. F., Muttalib, M. F. A., Krishnan, K. T., & Katimon, A. (2021). An overview of the internet of things (IoT) and irrigation approach through bibliometric analysis. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 756(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/756/1/012041

- Kirsten, J. F., & van, Z. (1998). Defining small-scale farmers in the South African Context. Agrekon, 37(4), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.1998.9523530

- Kremmydas, D., Athanasiadis, I. N., & Rozakis, S. (2018). A review of Agent Based Modeling for agricultural policy evaluation. Agricultural Systems, 164, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.03.010

- Kuma, T., Dereje, M., Hirvonen, K., & Minten, B. (2019). Cash Crops and Food Security: Evidence from Ethiopian Smallholder Coffee Producers. Journal of Development Studies, 55(6), 1267–1284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1425396

- Kuns, B. (2017). Beyond Coping: Smallholder Intensification in Southern Ukraine. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(4), 481–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12123

- Lowder, S. K., Skoet, J., & Raney, T. (2016). The Number, Size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Development, 87, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.041

- Lu, Y., & de Vries, W. T. (2021). A bibliometric and visual analysis of rural development research. Sustainability, 13(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116136

- Madrueño, R., & Tezanos, S. (2018). The contemporary development discourse: Analysing the influence of development studies’ journals. World Development, 109, 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.005

- Möllers, J., Traikova, D., Bîrhală, B. A.-M., & Wolz, A. (2018). Why (not) cooperate? A cognitive model of farmers’ intention to join producer groups in Romania. Post-Communist Economies, 30(1), 56–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2017.1361697

- Mottaleb, K. A., Rahut, D. B., Ali, A., Gérard, B., & Erenstein, O. (2017). Enhancing Smallholder Access to agricultural machinery Services: Lessons from Bangladesh. Journal of Development Studies, 53(9), 1502–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1257116

- Musafiri, C. M., Macharia, J. M., Ng’etich, O. K., Kiboi, M. N., Okeyo, J., Shisanya, C. A., Okwuosa, E. A., Mugendi, D. N., & Ngetich, F. K. (2020). Farming systems’ typologies analysis to inform agricultural greenhouse gas emissions potential from smallholder rain-fed farms in Kenya. Scientific African, 8, e00458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00458

- Nalau, J., & Verrall, B. (2021). Mapping the evolution and current trends in climate change adaptation science. Climate Risk Management, 32, 100290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100290

- Niknejad, N., Ismail, W., Bahari, M., Hendradi, R., & Salleh, A. Z. (2021). Mapping the research trends on blockchain technology in food and agriculture industry: A bibliometric analysis. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 21, 101272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.101272

- Novotny, I. P., Tittonell, P., Fuentes-Ponce, M. H., López-Ridaura, S., Rossing, W. A. H., & Hussain, A. (2021). The importance of the traditional milpa in food security and nutritional self-sufficiency in the highlands of Oaxaca, Mexico. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0246281. 16(2 February 2021) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246281

- Olusanmi, O. A., Emeni, F. K., Uwuigbe, U., Oyedayo, O. S., & Amoo, E. O. (2021). A bibliometric study on water management accounting research from 2000 to 2018 in Scopus database. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1886645

- Onyancha, O. B., & Onyango, E. A. (2020). Information and Communication Technologies for Agriculture (ICT4Ag) in sub-Saharan Africa: A bibliometrics perspective based on web of science data, 1991–2018. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 20(5), 16343–16370. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.93.19060

- Ota, L., Herbohn, J., Harrison, S., Gregorio, N., & Engel, V. L. (2018). Smallholder reforestation and livelihoods in the humid tropics: A systematic mapping study. Agroforestry Systems, 92(6), 1597–1609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-017-0107-4

- Phiri, A. T., Toure, H. M. A. C., Kipkogei, O., Traore, R., Afokpe, P. M. K., & Lamore, A. A. (2022). A review of gender inclusivity in agriculture and natural resources management under the changing climate in sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2024674

- Pienaar, P. L. (2013). Typology of smallholder farming in South Africa’s former homelands: Towards an appropriate classification system [ Thesis Stellenbosch University]. https://scholar.sun.ac.za:443/handle/10019.1/85627

- Pinheiro, A., & Govind, M. (2020). Emerging global trends in urban agriculture research: A scientometric analysis of peer-reviewed journals. Journal of Scientometric Research, 9(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.5530/JSCIRES.9.2.20

- Pouris, A., & Ho, Y.-S. (2014). Research emphasis and collaboration in Africa. Scientometrics, 98(3), 2169–2184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1156-8

- Priyadarshi, R., Routroy, S., & Garg, G. K. (2020). Postharvest supply chain losses: A state-of-the-art literature review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 18(3), 443–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-03-2020-0040

- Putera, P. B., Suryanto, S., Ningrum, S., Widianingsih, I., & Rianto, Y. (2022). three decades of discourse on science, technology and innovation in national innovation system: A Bibliometric Analysis (1990 – 2020). Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2109854

- Quoc Bui, D., Tien Bui, S., Kim Thi Le, N., Mai Nguyen, L., The Dau, T., Tran, T., & Feng, G. C. (2021). Two decades of corruption research in ASEAN: A bibliometrics analysis in Scopus database. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.2006520

- Reyna-Ramírez, C. A., Fuentes-Ponce, M. H., Rossing, W. A. H., & López-Ridaura, S. (2020). Characterization of mesoamerican smallholder farming systems. Agrociencia, 54(2), 259–277. https://www.agrociencia-colpos.org/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/1905

- Rukasha, T., Nyagadza, B., Pashapa, R., Muposhi, A., & Gikunoo, E. (2021). Covid-19 impact on Zimbabwean agricultural supply chains and markets: A sustainable livelihoods perspective. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1928980

- Schulman, M. D., & Garrett, P. (1990). Cluster analysis and typology construction; the case of small-scale tobacco farmers: A research note. Sociological Spectrum, 10(3), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.1990.9981935

- Sembada, P., Duteurtre, G., & Messad, S. (2019). A typological characterization of dairy farming system towards economic sustainable farm in West Java (Indonesia). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 387 https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/387/1/012021

- Shukla, R., Agarwal, A., Gornott, C., Sachdeva, K., & Joshi, P. K. (2019). Farmer typology to understand differentiated climate change adaptation in Himalaya. Scientific Reports, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56931-9

- Spitalar, M., & Hocevar, M. (2021). Sociology of Disasters and COVID-19. Druzboslovne Razprave, 37(96/97), 121–142. https://www.sociolosko-drustvo.si/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/DR96-97-WEB.pdf

- Stopar, K., Mackiewicz-Talarczyk, M., & Bartol, T. (2021). Cotton Fiber in Web of Science and Scopus: Mapping and Visualization of Research Topics and Publishing Patterns. Journal of Natural Fibers, 18(4), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2019.1636742

- Sweileh, W. M. (2020). Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature on food security in the context of climate change from 1980 to 2019. Agriculture & Food Security, 9(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00576-1

- Thamaga-Chitja, J. M., & Morojele, P. (2014). The context of smallholder farming in South Africa: Towards a Livelihood Asset Building Framework. Journal of Human Ecology, 45(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2014.11906688

- Toorop, R. A., Lopez-Ridaura, S., Bijarniya, D., Kalawantawanit, E., Jat, R. K., Prusty, A. K., Jat, M. L., & Groot, J. C. J. (2020). Farm-level exploration of economic and environmental impacts of sustainable intensification of rice-wheat cropping systems in the Eastern Indo-Gangetic plains. European Journal of Agronomy, 121, 126157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2020.126157

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2020). VOSviewer Manual: Manual for VOSviewer version 1.6. 15. Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) of Leiden University.

- Weltin, M., Zasada, I., Piorr, A., Debolini, M., Geniaux, G., Moreno Perez, O., Scherer, L., Tudela Marco, L., & Schulp, C. J. E. (2018). Conceptualising fields of action for sustainable intensification – A systematic literature review and application to regional case studies. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 257, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.01.023

- Widianingsih, I., Paskarina, C., Riswanda, R., & Putera, P. B. (2021). Evolutionary Study of Watershed Governance Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Science & Technology Libraries, 41, 416–434. Science and Technology Libraries. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2021.1926401

- Xie, H., Wen, Y., Choi, Y., & Zhang, X. (2021). Global trends on food security research: A bibliometric analysis. Land, 10(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020119

- Yang, S., Cheng, C., Shen, S., & Yang, J. (2018). Visual analysis of the evolution and focus of agricultural drought research on crops. International Agricultural Engineering Journal, 27(2), 348–352. https://gda.bnu.edu.cn/docs/20190216114844080129.pdf

- Yuan, B.-Z., & Sun, J. (2020). Bibliometric analysis of research on the maize based on top papers during 2009-2019. COLLNET Journal of Scientometrics and Information Management, 14(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09737766.2020.1787110

- Zárate-Rueda, R., Beltrán-Villamizar, Y. I., & Murallas-Sánchez, D. (2021). Social representations of socioenvironmental dynamics in extractive ecosystems and conservation practices with sustainable development: Abibliometric analysis. Environment Development and Sustainability, 23, 16428–16453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01358-4