Abstract

Fiji has had a turbulent political history of successive coups that have caused the nation to oscillate between the pursuit of ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism. Since the final coup in 2006, Fiji has suppressed ethnic nationalism that attributes national rights based on the ethnicity of indigenous peoples and has adopted a political trajectory of civic nationalism that promotes multi-culturalism and equal rights within the nation regardless of ethnicity. This article explores how indigenous Fijian (iTaukei) urban village residents continue to imbue urban space and infrastructure with ethnic value. The ethnic values they imbue in the city provide them a sense of belonging to the city, and the city belonging to them, forming an inalienable notion of ethnic citizenship in the urban context. I ethnographically detail how iTaukei urban residents imbued two spaces, an abandoned house, and a bulk clothing distribution centre, with ethnic value embodied by slogans “Magic City” and “Value City”. In this article, I argue that this ethnic project occurs within a broader moral geography whereby contested notions of how the city should operate between the civic nationalist Fijian state and ethnically nationalist iTaukei residents plays out. The Fijian state regulates this moral geography through the policing of urban space, the suppression of free speech, and the implementation of urban formalisation policies.

1. Introduction

Since the independence movement in Oceania from the 1970s onwards, Oceanic states have pursued nationalism based on ethnic ties to the nation. This approach has been used to bind the disparate indigenous peoples together into a collective national entity. Currently, many Oceanic states are still encouraged to promote ethnic forms of nationalism as part of the nation-building project in the region. Fiji is the exception. Fiji has had a chaotic political history punctuated by four political coups in 1987 (twice), 2000, and 2006. Each of these coups emerged in the context of the perceived erosion of indigenous Fijian (iTaukei) prominence in the nation’s political, economic, and cultural life by Indo-Fijian politicians and interests. In the aftermath of these coups, Fiji’s political trajectory has landed on a form of nationalism based on multi-culturalism and equal rights regardless of ethnic background (Lawson, Citation2004; Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). For many iTaukei Fijians, an ethnic basis for belonging to and governing the nation is preferred but suppressed by regulations restricting free speech and media (Singh, Citation2015; Singh & Prasad,). However, there are alternative ways in which ideas of ethnic citizenship can be explored.

In this article, I argue that urban iTaukei residents, specifically those that come from urban villages, actively create, and connect places of ethnic values to public places within the city. By binding the places in the city to places of ethnic value, they conceive of the city as inherently iTaukei in ways that cannot be alienated from them. The claiming of the city under indigenous value was seen across the Pacific, including Fiji, after many nations achieved political independence from European colonial rule (Foukona, Citation2015; Jones, Citation2016; Lindstrom, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). The contemporary post-coup Fiji context since 2006 provides a different environment in which claiming ownership of the city is strived for. iTaukei urban residents are attempting to orient urban space in ways that aligns with iTaukei ethos in opposition to conceptions of space tied to the civic nationalist and multicultural agenda. This state agenda is being enforced through state policing and urban regulation in ways that actively undermine the exploration of ethnic value and disjoints the flow of ethnic value across space. The struggle to imbue and interlink space with certain value in ways that push back against state sanctioned ethical conceptions of what the city should embody can be conceived within the concept of moral geography (McAuliffe, Citation2012; Pow, Citation2007; Van Liempt & Chimienti, Citation2017). iTaukei urban residents and the state are involved in a contest revolved around the interlinking and orienting urban space. This contest is underpinned by postcolonial moralisations of their respective ethnic and civic nationalist perspectives.

In this article, I focus on detailing the ethnic project of iTaukei Fijians that contests state urban regulation and policing that enforce civic orientations of space. I identify two nodal points from which iTaukei ethnic urban morality disseminates out to other parts of Suva City. The first of these nodal points is an abandoned house in central Suva which male teenage youth from urban villages occasionally sleep in. This abandoned house provides a place from which an imagined “Magic City” defined by the free appropriation and exchange of currency and possessions is disseminated across Suva. The second nodal point is a bulk second-hand clothing store called “Value City” where urban village women buy clothing to on-sell in Suva Central Market. Value City provides a locale where these women can recreate relationships of care, reciprocity, and mentorship with each other that can extend out to public marketplaces. Both examples demonstrate an active interrelating space with ethnic value in a broader moral geography. Both urban village male youth and urban village women imbue and connect urban space in ways that avoid temporal state regulation of space.

In this article, I firstly discuss how reading emotions in space, as a part of my overarching methodology, allows for a recording of how urban village residents imbue space with ethnic value within a contested moral geography. I secondly summarise Fiji’s history of political coups, which has seen the nation oscillates between ethnic and civic nationalism before landing on the current iteration of civic nationalism. I thirdly detail the process in which rural–urban migrants in the post-colonial Pacific lay moral claim to the city, and how this claim is contested in a broader moral geography, especially in contemporary Fijian context. I fourthly, introduce two urban spaces, an abandoned house, and a bulk clothing distributor, with their respective slogans “Magic City” and “Value City”. Through these examples, I detail how urban residents interrelate urban space in ways that disseminate ethnic value across Suva City. I fifthly document how this ethnic project is regulated by the Fijian state and how these urban village residents navigate regulation in the broader moral geography. I lastly, detail the state of these moral geographies from the data I gathered from return trips to Suva Fiji across 2021–2022. This return trip reveals the continual adaption of urban residents in laying claim to the Pacific City, as well as the effect of a formalising cityscape on their practices since my initial 2016–2017 fieldwork.

2. Methodology

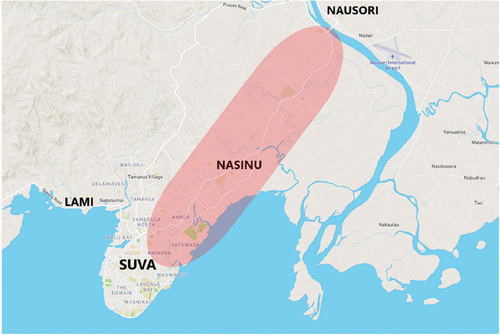

I did not initially go to Fiji in 2016 to investigate indigenous Fijian ethnic nationalism. My original brief was to investigate “The Moral and Cultural Economy of the Mobile Phone in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Fiji” as part of that project’s broader team (Foster R & Horst H, Citation2018). My background in Development Studies led me to investigate how the domestication of the mobile according to traditional principles affected local financial inclusion among those from the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. I was particularly interested in how financial applications such as “mobile money”, which allow the person-to-person-transfer of currency across mobile devices, were domesticated into everyday life. During my first couple of weeks in Suva Fiji, I frequently met Jone, an iTaukei in his mid-teens, selling bananas near the Central Suva Market. I have replaced all personal names in this article with pseudonyms to protect research participants. After many encounters with Jone in the city, he invited me to go fishing with him and his friends in his urban village in the Suva-Nausori corridor (Figure indicated in red). There are approximately 90,000–100,000 people living in urban villages across Fiji, with 60% of this population living in the Suva-Nausori corridor (Thornton, Citation2009). Historically, urban villages have been a nodal point of mobility and exchange between rural and urban places. Urban villages have been the location where rural–urban migrants first land in the city (Lasaqa, Citation1983; Walsh, Citation1978). The iTaukei residents of urban villages also often maintain strong connections to kin on home islands and therefore it is a place of continual material and cultural exchange that permeates further into the city (Jones, Citation2016). Jone’s urban village was no exception, being composed of cohesive kinship units that connect back to the eastern rural islands of Fiji in the Lau and Lomaiviti island groups.

After subsequent visits and dinner with Jone and his family, I was invited to stay with them for the duration of my one year of ethnographic fieldwork. Through my relationship with Jone, his family, and their network of kin and neighbours in the urban village, I gathered data that I would later come to appreciate intersects with iTaukei Fijian’s everyday pursuit of ethnic citizenship. Due to a fear of political surveillance by the Fijian government, I was seldom given any direct commentary by my Fijian interlocutors beyond a few unrecorded guarded phrases on the topic of ethnic citizenship and nationalism. A typical response in mobile media surveys I conducted was that mobile users did not express political views on social media sites such as Facebook. Various respondents specifically mentioned that they did not engage in political discussions on social media out of fear of being surveilled by the Fijian government. Many of these respondents believed that if they expressed political opinions, the Fijian government would find out and they would lose their jobs. This belief was stated by many employees in bureaucratic positions or those whose jobs relied upon governmental funding. Fear of political surveillance limited political discourse in public and similarly effected how my interlocutors felt about being voice recorded. Similar concerns of media surveillance and repercussions have been stated in the current literature (see, Brimacombe et al., Citation2018; Kant et al., Citation2018).

The lack of verbal articulation subsequently affected how I collected data on how urban village residents pursued ethnic citizenship within a broader moral geography. By reading emotion or “affect” and how it impacted urban space and infrastructure, I understood the pursuit of ethnic citizenship in space. Emotion is a bodily or behavioural response to an event or context borne out of rational thought, influenced by world view and ideology, and not detached spontaneity. Furthermore, a joint meeting of emotion can create certain identifiable atmospheres of articulation (Davidson & Milligan, Citation2004; Thien, Citation2005; Thrift, Citation2004). Other geographical studies have increasingly considered how emotion pervades space and infrastructure (Faier, Citation2013; Street, Citation2012; Szadziewski, Citation2020; Thomas, Citation2002). These studies are attentive to the general atmospheres of emotion that accompanied words and actions that pervaded space and infrastructure. In the Fijian context, there were instances where frustration, resignation, defiance, or lament, were expressed that pervaded urban space and infrastructure. Such consideration of emotion has been carried out with Indo-Fijians in space in relation to the political context of Fiji (Trnka, Citation2010, Citation2011), but less so with iTaukei Fijians. Through reading atmospheres of iTaukei emotion in certain spaces and flashpoint moments, I understand the project of urban village residents. I also read how such atmospheres of emotion change in different contexts of political suppression to assess how the Fijian state regulates urban behaviour in a broader moral geography. I read this affect in two spaces: an abandoned suburban house and at a bulk clothing distributor. These observations provided nascent data, in a methodologically difficult to access context.

3. A history of ethnic nationalism in Fiji since 2000

The development of the ideas of exclusive iTaukei Fijian ethnic nationalism and the more inclusive civic nationalism since Fiji became an independent nation in 1970 has been a topic of extensive inquiry as it has been the driving force behind Fiji’s history of political coups. In moments of political dissatisfaction with the Fijian government’s efforts to protect and advocate for the political rights of either iTaukei Fijians or Indo-Fijians, four political coups have been initiated, two in 1987, 2000, and 2006. Lawson (Citation2004) has explored the two countervailing forces of iTaukei Fijian ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism that Fijian elections and political coups have been historically driven by. She explains that civic nationalism is premised on “uniformity of law,” whereby each citizen is attributed equal political legitimacy regardless of ethnicity, language, religious affiliation, or gender. In the case of Fiji, when the Fijian government and its constitution uphold civic nationalism, Indo-Fijians and other non-indigenous ethnic groups have been afforded equal rights and status with iTaukei Fijians. Ethnic nationalism, on the other hand, does not conform to “uniformity of law” and rather attributes political rights and legitimacy to citizens based on their ethnic affiliation. Ethnic nationalism is premised on the “normative nationalist principle” that “homogenous cultural units form the natural foundations for political life and the cultural unity between rulers and ruled carries a self-evident legitimacy” (Lawson, Citation2004, p. 522). In the case of Fiji, when ethnic nationalism has been upheld in Fijian politics, iTaukei Fijians are provided paramount rights and status over their Indo-Fijian counterparts. Fijian politics has oscillated between instituting national constitutions based on civic nationalism or ethnic nationalism. These oscillations between these two forms occur in political elections, redrafting the national constitution, and in instances of political coups (Lawson, Citation2004).

The 2000 coup seemingly entrenched the doctrine of ethnic nationalism that aligned with a protectionist orthodoxy. This position was supported by the formulation of three bills proposed by the government led by Laisenia Qarase. The first was the Promotion of Reconciliation, Tolerance, and Unity (RTU) Bill, which advocated amnesty for those involved in the 2000 coup. The second was the Qoliqoli Bill which aimed to designate all foreshore areas as “native reserves”. The third was the Indigenous Claims Tribunal which aimed to allow mataqali (the primary land-holding group in Fiji comprised several core iTaukei family units) to make historical claims to the ancestral land currently under occupation by the state. Riding the wave of ethnic nationalist sentiment in the aftermath of the 2000 coup and re-election of the Qarase government, these three bills that proposed to aggressively pursue indigenous rights were broadly supported by indigenous iTaukei Fijians (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). However, Vorque “Frank” Bainimarama, leader of the Fijian military, was concerned about the possible ramifications of instituting these bills on Indo-Fijian relations and the economy. Bainimarama’s dissatisfaction with the method of rule by the Qarase government led him to take over the government under a “legal doctrine of necessity” in 2006 (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). The 2006 coup scaled back ethnically protectionist measures that, for the most part, motivated previous coups. For the first time in Fijian politics, the orthodoxy that set the norms of the protection of Fijian tradition defined in opposition to foreign influence and individualism was forcefully removed (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016).

Since the 2006 coup, the Bainimarama-led government has taken unprecedented measures to progress his vision of multi-culturalism and civic nationalism to the detriment of ethnic nationalism embodied by the previous Qarase-led government. The most prominent of these moves was introducing Public Emergency Regulations (PERs) in 2009 that prohibited public and private gatherings with more than three people without a permit (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). Along with various arrests, detention, and harassment, the Bainimarama government suppressed any critical opinion. In addition to this, he abolished the Great Council of Chiefs, which was the stalwart of Fijian ethnic nationalism and particularly the Qarase government. The position of the Methodist Church, which advocated for the creation of the Fijian Christian state with strong ethnic nationalist values, was also severely restricted in its ability to mobilise political action due to the PERs (Newland, Citation2013; Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). The military that historically aligned with ethnic nationalist goals is also aligned with the Bainimarama government due to personal loyalty to Bainimarama (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016).

These measures made the Bainimarama government unpopular among the iTaukei population at the time; however, they allowed for elections to be delayed until 2014 when dissent had simmered. In 2014, Fiji First (FF) led by Bainimarama continued to run on its multi-cultural and civic nationalist doctrine. In contrast, its primary opposition, the Social Democrat Liberal Party (SODELPA), ran on the ethnic nationalist Christian platform. FF had control over the national media and was running on a platform that appealed to a wide demographic, whereas SODELPA relied upon more localised campaigns based on kinship and socio-cultural factors that only appealed to the iTaukei Fijian demographic. By appealing to iTaukei reformists primarily in urban areas and an overwhelming majority of Indo-Fijians, FF won in a landslide victory (Ratuva, Citation2015; Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). Since the 2014 election, free speech and media restrictions have defined the FF government. They have further gone on to win the election in 2018 (Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016). At this moment, it seems that ethnic nationalism has increasingly become marginalised in Fijian politics with minimal prospects of reasserting dominance in its current form. Restrictions of speech and media also suppress ethnic nationalist political opinions that diverge away from FF’s multi-cultural civic-nationalist platform (Kant et al., Citation2018; Singh, Citation2015; Singh & Prasad,).

Since the rise of civic nationalism in Fijian political life, there has been more of a focus on how inclusive forms of citizenship have been fostered in Fiji. There has been a focus in research on governmental and media efforts to pursue banal forms of nationalism that stretch beyond ethnic distinction since the political coups (Connell, Citation2007, Citation2018). Meanwhile, just how ethnic nationalism and citizenship are explored by iTaukei Fijians that was previously prominent in literature has dissipated from research barring notable exceptions (Kant, Citation2019). This reduction in coverage of this topic can in part be due to its decrease in importance in everyday political life for some Fijians. The shifting political perspectives of some Fijian demographics to a more consolatory position towards the citizenship debate, as well as the fatigue of iTaukei Fijians regarding the issue in general after decades of political coup (Ratuva, Citation2015; Ratuva & Lawson, Citation2016), has put the topic of ethnic citizenship on hold in Fijian society and therefore academic scholarship. However, the decrease in academic coverage of ethnic citizenship in Fijian society is also due to the Fijian’s governments relative success in pushing the movement out of public discourse, display, and media. The topic of media restriction in Fiji dominates the conversation without discussion of the status of ethnic citizenship and how it is alternatively pursued in this context other than notable works covering online activism (Brimacombe et al., Citation2018; Kant et al., Citation2018). Here, I add to the literature by exploring how ethnic citizenship is explored in marginal space when such public and media avenues are closed.

4. Pacific urban moral geography

The project of crafting space that instils a sense of belonging to Pacific peoples is by no means new. Prior to political independence, the Pacific City was a place for colonial administration that had restrictions that excluded Pacific peoples from residing, working, and moving within the city (Connell & Lea, Citation1994). In the years immediately preceding political independence and after political independence, rural–urban migration accelerated. A project of instilling ethnic values and norms in the previously colonial Pacific City was pursued. This ethnic project was inspired by a sentiment of expressing sovereignty and autonomy over how everyday society was organised within newly forged independent nations. This ethnic project was reflected in the residential communities that rural–urban migrants set up in Pacific cities. These residential communities have historically been defined by Pacific governments as “informal settlements” because residents of these communities do not have formal land tenure on the lands they have settled. Jones (Citation2016) however defines these “informal settlements” as “urban villages” or “village-like settlements” as they are a place where traditional kinship ties are maintained, traditional subsistence livelihood activities are pursued, ceremonies involving crops produced in these subsistence livelihood activities are shared with close social contacts, and more traditional land tenure agreements are also upheld. The forms of relationality and socio-spatial organisation of these urban residential communities mirrored those that were prevalent in rural locations. The Pacific rural–urban migrants imbued the Pacific City with ethnic qualities imported from their home islands and villages of origin. This process has been explored in independent nations across the Pacific (Foukona, Citation2015; Jones, Citation2016; Lindstrom, Citation2011a, Citation2011b).

This production of locality instilled with ethnic value (Appadurai, Citation1995), has been the basis for claiming ownership over the city in the postcolonial Pacific context (Connell & Lea, Citation1994). Foukona (Citation2015) utilising Lefebvre’s (Citation1968) “right to the city” argues that the intertwining of migratory paths and histories with the city reifies the right of rural–urban migrants in the Solomon Islands to the city. Just as multiple peoples, mobilities and places make up Melanesian personhood that cannot be alienated from the “dividual” (LiPuma, Citation1998; Mosko, Citation2010; Strathern, Citation1988), the Pacific City as a bodily entity composed of a web of interconnecting peoples and migratory paths leading back to rural sources of ethnic value equally cannot be untied. Processes of urbanisation, such as land formalisation, the emergence of commoditised relationships, and global cultural diffusion all threaten to unravel the interconnection cities have with ethnic and social relations of significance (Dornan, Citation2020). However, collective converging of histories, ways of life, and ethics of interaction, of the cities inhabitants establishes the city as rightfully and inalienably belonging to them.

Despite this postcolonial claiming of the Pacific City through the amalgamation of migratory histories to the city and the production of locality, key studies detail how there is an increasing alienation of urban citizens from rural places of ancestral origins (Kraemer, Citation2020; McDougall, Citation2017; Sykes, Citation1999). Such disconnection presents obstacles to connecting to and utilising ethnic value in the Pacific City. Those who are considered alienated from rural places of origin are second and third generation rural–urban migrants, who have not visited their islands of ancestral origin. These disconnected urban residents are considered as having no discernible history and place. This is most aptly described by Kraemer (Citation2013) who details how alienation from rural communities Vanuatu is akin to “losing your passport”. Without a “passport” one cannot return to or connect with rural villages of origin. However, equally without a “passport” one is excluded from being a part of the converging histories and mobilities that intertwine into the unravelable ethnic fabric that has historically defined the Pacific City. Losing one’s “passport” entails losing access to “the ni-Vanuatu person’s inalienable right to ground and to absolute autochthony” (as cited in McDougal, Citation2017: 5). This lost “right” relates not only to a connection to rural ground and society but also how urban ground is occupied and defined. One cannot weave the urban fabric in line with the previous post-independence process of imbuing of space without ethnic identity intact.

Kraemer (Citation2020) does however provide a counter point. She documents how sources of ethnic value are starting to be “planted” in the urban landscape, even with the most tenuous rural “roots”. She details how new or changing spaces within the Pacific City can emerge as sources of ethnic value which can be further disseminated to other spaces in the city. Second-generation youth are weaving new interconnecting relationships and urban spaces together within the cityscape based on emergent urban identities and practices. There is a movement to claim the “right to the city” via ethnic grounds in the context where post-colonial connection to rural islands is absent. I continue Kraemer’s (Citation2020) argument by exploring how even the most unlikely urban spaces such as an abandoned house or a bulk clothing distributor can be elevated to be sources of ethnic value, from which ethnic value can be further disseminated. Yet I argue that this inter-urban ethnic project is positioned within a broader contested moral geography in Fiji.

As argued in urban studies literature, the city, and the right to occupy and define it, is governed by localised ideas of morality space and power. A bulk of moral geography literature, drawing inspiration from Williams (Citation1973) seminal work The Country and the City, analyses the development of oppositional moral codes between rural and urban locations, and how those rural\urban moral divides are maintained or mediated in the context of modernisation and globalisation (Jansson, Citation2013; Thomas, Citation2002). Other studies analyse how access and use of urban spaces is negotiated by urban residents. This includes building walls for graffiti artists (McAuliffe, Citation2012), red light districts for sex workers (Van Liempt & Chimienti, Citation2017), or gentrified areas for the poor (Pow, Citation2007). Such studies highlight how access to these areas is defined by shifting moral codes that intersect with state power to implement regulation and shift moral discourse. I argue that the urban moral geography in Suva Fiji embodies a citizenry determination to resist the rural\urban moral opposition outlined in Williams (Citation1973) inspired work. Urban citizens in Suva alienated from rural islands of ancestral origin attempt to rebind the city to adapted ethnic values in an inter-city moral geography. However, this citizenry determination is contested by a coup paranoid Fijian state resisting the imbuing of specific urban space with a perceived dangerous ethnic value. The Fijian state actively regulates the city through the policing of public space and urban formalisation. In the remainder of this article, I explore how urban residents in Suva Fiji continue to imbue city space with ethnic value in ways that contest state-based civic nationalist urban regulation in what can be defined as a contested moral geography.

5. Moral geographies of Fijian urban village residents

5.1. Magic City

Jone, despite introducing me to his family in 2016, rarely stayed at the urban village where his family lived. He was often sleeping elsewhere across Suva. The places where he slept were in other urban villages across the peri-urban fringe of Suva where he had relatives or friends. Jone often spent most of his time in the centre of Suva, selling produce that he had acquired from these urban villages. The produce he sold was often bananas or plantains, but when these items were out of season or he could not acquire them from urban villages, he bought other produce from Suva Central Market. He would then on-sell this produce to tourists at a considerable markup. From the income that he earned during the day he would buy a meal from one of the many food courts in Suva. Jone would forego the bus fare to travel to one of these urban villages when he did not have enough money left over. Rather, he stayed at an abandoned suburban house close to the heart of Suva City. The abandoned house was a place where a large collection of male youth stayed and had certain norms of access. There was an age hierarchy where older male youth slept upstairs in the bedrooms, which offered some privacy. Teenage youths were required to sleep downstairs, which could only be accessed from the outside and resembled a storage cellar. The house was exposed to the elements as all the windows had been smashed, and wall segments were also missing. The downstairs area was also covered with litter and smelt of urine.

Relaxing with the younger male youth on an early Sunday morning, we sat on mattresses on the floor. As I was not familiar with all the youth present, I asked where they were from. Like Jone, they were born and raised in urban villages surrounding Suva and had met in town in pool halls and game arcades. Their stories were similar in that they did not fully identify with the urban villages they were brought up in, referencing arguments with their parents or relatives. While sitting with them, I observed how they interacted with each other, unfettered by the social norms that dictated everyday life in urban villages. The most visible practice I observed was the constant circulation of currency and consumables such as cigarettes. In the two hours, I was sitting with them, they were pickpocketing off one another as if it was a kind of game. If coins or cigarettes were made visible, they were open to being taken by one another, and it was a type of challenge to take them without being seen or caught. Regardless of whether the attempts went unnoticed, the taker kept the coins or cigarettes without any ill will by the others. The activity was accompanied by joking and laughter. When I asked about this game, one of the youths stated that they “lived in each other’s pockets” and that what they each owned was also the property of each other, “like brothers”. Such circulation and appropriation of resources closely resembled the practice of kerekere whereby there is an unquestioned obligation to give whatever is asked by kin in times of hardship (Farrelly & Vudiniabola, Citation2013). The observation of this circulation and appropriation of resources in the abandoned house, however, had been extended to urban acquaintances outside of kinship. The abandoned house was a space of sharing and resource appropriation denied to them within kinship and in the domestic spheres of the urban village.

This type of ethos, however, spreads much further out spatially than the abandoned house. These male youths had drawn their view of how Suva City should operate upon the walls of the abandoned house (Figure ). It represented their conception of interconnected spaces extending from the abandoned house outward to other city spaces and vice versa. Talking with the youth at the abandoned house, they told me that the picture titled “Magic City” represented a place of unfettered opportunity. Any iTaukei Fijian could come to the city and take what was rightfully theirs. It was an extension of the ethos explored in the abandoned house itself but extended out on a city-wide level. In this moral geographic imaginary, the city is imbued with the principles of sharing and communality specific to their circumstances which connects them to a form of ethnic citizenship currently denied to them. The emblem of “Magic City” gave them confidence to go to other urban spaces and act according to what they believed was morally just. This included the same kerekere from each other at the pool hall, and at the candy stalls behind Suva Central Market. “Magic City” bound a growing collection of urban spaces together with a shared ethos that male youth had created that was pushing back against both older conceptions of ethnic citizenship and the current barring of emergent forms of ethnic citizenship.

5.2. Value City

During the time I spent in the household in the urban village throughout my fieldwork, I also got to know the family members well and their life histories. Josivini, the mother to Jone was the primary economic provider for the household. Josivini came from a native village called Lotuyarabale (pseudonym) near Lami on the peri-urban fringe of Suva. The history of Lotuyarabale was recounted to me by Josivini’s older brother John talking over tea in the afternoon, while a local ceremony was being conducted. Their village was created in the late 1800s when one of their ancestors came from Lami and settled Lotuyarabale. The village overlooks Suva harbour towards the city. Lotuyarabale maintains strong kinship ties to Lami village as many kin born in Lotuyarabale decide in adulthood to live in Lami village. Many also decide to continue living in Lotuyarabale because they come to consider it their native village, and because the city is also very accessible, being only 40 minutes away by bus. Today, many are forced to move away from the village due to a lack of land and space. Those who stay in Lami or Lotuyarabale are usually the eldest children. It is also customary for women to live in their husband’s village regardless of if their husband lives in a native village or urban village.

Josivini, her twin sister Elenoa, and the next eldest sister Selina all moved to urban villages in the Suva Nausori Corridor with their husbands after they were married. Even though Josivini and her sisters were able to visit Lotuyarabale, this required substantial time and financial cost, which often could not be afforded. Participation in communal and fundraising events such as soli were therefore not frequent. As a result, Josivini and her sisters were partially disconnected from embedded social relationships on land of origin. Some form of alienation of women from ancestral villages is not uncommon due to the practice of wives moving to their husband’s villages, however this is somewhat offset by the husband’s village welcoming their wives to their village with appropriate exchanges and ceremony. Urban villages play a role in recreating village life and its embedded social relationships; however, it is an imperfect approximation. Just like male youth, Josivini and other urban village women are compelled to engage in the process of forming and establishing new socio-spatial contexts that would re-connect them to a form of ethnic citizenship. I observed that this moral geography was explored in Value City, a second-hand bulk clothing store, and Suva Central Market. These women actively imbued these spaces with communal norms of exchange and reciprocity, re-connecting them to ethnic citizenship.

Every day Josivini and other urban village women would buy second-hand Australian clothing from Value City, which they would then on-sell at Suva Central Market. This activity was a popular livelihood activity that provided daily monetary income for their family. At Value City, urban village women would have an opportunity to select which clothing they wanted to buy and put the clothing in plastic bags ready for purchase (Figure ). Women bought clothing at Value City according to weight as opposed to set prices for each item. The women’s conduct at Value City demonstrated that the process of selecting clothes to sell in Suva Central Market allowed them to participate in communal and reciprocal relationships. Josivini who had bought and sold second-hand clothing for a long period of time had taken under her wing a younger woman from a neighbouring settlement to teach her the “tricks of the trade”. These included advising her not to be lured in by bulky or winter clothing that weighed a lot. She also advised her which clothing was most fashionable or in demand at the market. She relished this task, of being able to teach this younger woman something she had mastered so that she could, in turn, support her family’s precarious livelihood. Value City within Josivini’s moral geography was a place where she could participate in consistent embedded social relationships that is akin to “relations of care” (Trnka & Trundle, Citation2014), or in local vernacular “loving each other” (Brison, Citation2007). Opportunities for Josivini to participate in relations of care were otherwise limited, as she was separated from away from her native village and recreating these village-like relationships was not fully realised within the urban village. Finding spaces in which these forms of care and reciprocity could be practiced were integral for urban village women like Josivini to connect with Fijian culture and identity within the city.

6. The regulation of urban moral geographies

“Magic City” and “Value City” are two specific examples of how urban village residents try to connect and interrelate space in ways that imbue urban space with ethnic value in contexts of rural disconnection. Such activity is relatively banal until the regulation of urban space by the Fijian government is considered. Historically, the regulation of urban space by the Fijian government is not new. Most notably, urban villages, which are a key location where migratory paths and histories meet, were not legally recognised by the Fijian government for most of the post-colonial period (Connell, Citation2003). The lack of legal recognition entailed that garbage collection and formal connection to basic utilities such as water and power were denied to urban village residents (Phillips & Keen, Citation2016). In addition to this, urban village residents have consistently been portrayed by various politicians as criminals, prostitutes, and beggars (Connell, Citation2003). Urban village residents do not belong in the city in contrast to “good” middle-class residents. This notion of the “good citizen” in Fiji reflects Eurocentric forms of being that were adopted by the Fijian chiefly class during the colonial era (Connell, Citation2003). Such contrast between the urban “good citizen” and the rural migrant that disrupts urban order is present across the Pacific in different iterations (Widmer, Citation2013) but is particularly evident in Fiji (Bossen, Citation2000; Connell, Citation2003, Citation2007).

The Fijian government has since progressively taken steps to formalise land tenure in urban villages and connect residents to infrastructural services. However, this has in part been motivated by a desire to improve its human rights records following a history of political coup and not necessarily to foster ethnically inclusive cities (Phillips & Keen, Citation2016). Furthermore, the formalisation of urban villages has not had an entirely inclusive effect. Formalisation efforts have tended to gentrify urban villages in ways that push residents out of their communities by including fees on obtaining formal land titles (Mausio, Citation2021; Weber et al., Citation2019). For the residents that can and are willing to stay, their urban villages are reformatted whereby houses are positioned in grid like formats, agricultural land is destroyed and reallocated as residential plots, and various previously defined urban village communities are displaced and aggregated together. As such, the formalisation of urban villages has tended to degrade rather than incorporate ethnic forms of social organisation upon which these communities thrive (Watt & Donaldson, Citation2020). The social disruption this formalisation process creates weakens the unique position of urban villages within the social imaginary of urban village residents that connects them to ethnic values. Packaged as a New Urban Agenda, the formalisation of urban villages is a continuation of a regulation of the moral geographies of urban residents in Fiji in favour of more Western urban ideals.

Urban village residents are not just a simple threat to a Western colonial derived urban order. Currently, urban village residents are a threat to establish ethnic forms of urban structure and organisation that would contravene the Fijian government’s drive for inclusive forms of urban citizenship. Currently, restrictive urban state-based policing and private security have emerged under the guise of protecting public urban order across the Pacific (Carnegie & King, Citation2020). Urban state policing and private security simultaneously stifle any alternative ethnic forms of urban structure and organisation. The regulation of urban space in ways that prohibits forms of gathering or interaction that are perceived to be disruptive of urban order make it more difficult for urban residents to diffuse ethnic values into urban space. As such public space is progressively formatted in ways that alienate such space from urban village residents, thus weakening their ethnic citizenship. Despite the emergence of prohibitive urban spatial regulation, these restrictions have not entirely prevented residents of urban villages connecting urban space according to ethnic relations within a broader moral geography. This is seen in the cases of “Magic City” and “Value City”. Urban village male youth and women connect public space in ways that avoid or sidestep the gaze of urban policing. The urban spaces that they connect are marginal spaces that do not garner political attention or reach. These urban spaces may also only be available for short moments of time as they shift between spaces of political visibility and blindness.

The abandoned house, for instance, was subject to regulation by the state. During my time sitting with male youth was cut short when they looked at the time on one of their phones: 10 AM. At the announcement of this time, they all immediately got up and started to prepare to leave. They stated that the police would soon be coming to see if anyone was sleeping in the house. They told me that the police often came, while they were sleeping and gave them fines of $80 each or a day and night in a cell. Knowing the specific times that the police preferred to check the house, they were able to avoid this encounter, and therefore continued to use the abandoned house as their central accommodation in a way that was relatively risk-free. Even though they were able to consistently evade the police, the emotion as soon as they knew they needed to leave the abandoned house told of how the forms of ethnic citizenship they were creating were being restricted. The “magic” of contribution and sharing dissipated as soon as the potential of regulation entered the abandoned house. It was fragile and temporal. The tone of frustration that marred the situation exhibited that they believed they should stay at the house without restriction. Such regulation of how spaces should be used and occupied directly betrayed the ethnic tenets of the “Magic City” they had developed. Through emotion, these male youth articulated that the city had been overcome by a regime that embodied an alien set of principles that prohibited any form of alternative ethnic citizenship to develop. Despite this, they moved on to a local pool hall where they could continue exploring ideas of exchange and free appropriation.

A similar atmosphere of articulation could be felt among urban village women. The exploration of emergent ethnic values in Value City was not permitted in Suva Central Market where they sold the clothes that they had acquired. Suva Central Market is regulated by a system of licenses that these women did not hold. Their activity was considered disruptive to the order and norms of the market by authorities to the extent that they would fine these women on a frequent basis. This, however, did not stop urban village women from selling their clothes. They did so under the tables of produce sellers who were willingly complicit in this activity (Figure ). There was also no shortage of knowing customers within the market who wanted to buy clothing from them. These customers were not depersonalised entities, but other women considered friends in their network of care and reciprocity. The tone urban village women selling their clothes did not resemble fear, especially as their attempts to veil their activity were weak. Anyone could understand what was happening if they looked hard enough as women constantly went in and out under tables during the day. There was even a sense of pride of riding the line of resistance and getting caught. This resembled the expression of insurgency that was binding women across Suva City together in a way that reframed the city according to unfettered socialised exchange. The sharp distinction felt between Value City and Suva Central Market embodied how alternate ethnic values that can be explored in unregulated spaces, are felt much differently in public market spaces. The jubilant atmosphere of Value City was replaced by weakly veiled but defiant subterfuge in Suva Central Market designed to demonstrate their right to connect, occupy, and imbue public urban space with a concept of how they believed the city should operate against urban policing.

These two examples show that urban village residents are still able to connect urban space together to lay claim to the Pacific City in a broader moral geography of ethnic/civic nationalist tension. However, this ethnic project requires the temporal use of urban space, mobility between urban spaces, and tactics that either evade or test the gaze of urban regulation. This temporality, mobility, and speculative testing of policing indicates a potential fragility of the ethnic position within this moral geography. However, the ability of iTaukei urban residents to weave between urban political and regulatory context as they search out and fill marginal and unregulated spaces also indicates flexibility and adaptability within the urban moral geography. What was uncertain was their capacity to continuously iterate and change in an increasingly formalising context at the conclusion of my 2016–2017 fieldwork. In 2021–2022, I had an opportunity to return to Fiji.

7. A formalising cityscape

When I returned to Fiji in December 2021, I was curious what had happened to urban spaces that I had observed in 2016. I was already aware that the abandoned house had burnt to the ground in late 2016 leaving an empty grass lot behind (Deo & Turaga, Citation2016). However, the bulk second-hand clothing distribution centre of “Value City” had more recently closed its doors in the Suva-Nausori corridor. Meanwhile, multiple Value City retail stores had opened across Suva. These stores did not have the bins of unsorted second-hand clothing of the bulk distribution centre. Clothes had been pre-sorted by Value City staff and put onto clothing racks ready for the general consumer to buy.

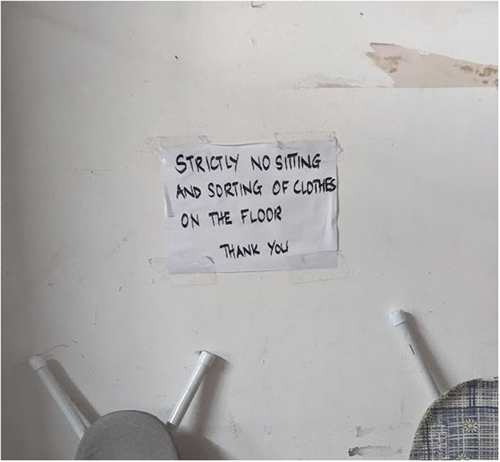

Despite the disappearance of the material infrastructure, I observed in 2016, I saw remnants of these spaces in new adapted form. Jone had acquired some construction work which had allowed him to stay more frequently in the family household in the urban village due to an increased contribution to the family budget. On his days off, I often saw him within the urban village with others who had also acquired stable work. The urban village, like others in Suva, had gone through a process of formalisation which subsequently caused many families to rebuild or upgrade their houses (Kiddle & Hay, Citation2017). These reconstructions were often larger, providing more spaces to meet. Greater opportunity to contribute also increased the level of tolerance of youth “hanging out” in domestic spaces by other older family members. I observed many of the same forms of sharing and appropriation I had seen previously in the abandoned house; however, this acquisition of work and access to space in the urban village fostered a more domestic “Magic City” atmosphere. A temporary police-post had been placed within the settlement in response to an apparent increase in domestic disturbances. The increased police presence in the settlement largely kept such gatherings within homes. Meanwhile, the livelihood activity of buying second-hand clothing at Value City and on-selling it in Suva Central Market remained popular despite the company’s transition to retail stores as opposed to bulk distribution centres. There were attempts by Value City staff to prohibit the ways in which clothes were previously sorted by urban village women at the bulk distributor (Figure ), however this activity was informally restricted to certain areas of the store near the security guard and cash register (Figure ).

My return to Fiji revealed to me that the unregulated marginal spaces of the abandoned house and Value City that I observed in 2016 had disappeared, but new spaces were indeed found. These spaces, however, were emplaced in a slowly formalising cityscape. The burning down of the abandoned house and the closure of the bulk clothing distributor cannot be directly attributable to Fijian state urban policy, however the spaces available to replace these previous spaces reflect a narrowing of space in which ethnic value can be pursued. Urban village residents seemingly were able to explore forms of ethnic citizenship according to shifting personal circumstances within these new spaces; however, the formalising landscape also rendered these explorations more constrained, observable, and controllable. Such a drive for formalisation is a part of Fiji’s adoption of the New Urban Agenda to create more “inclusive cities” that organises space according to preordained civic ideals (Kiddle et al., Citation2017; Phillips & Keen, Citation2016). At the same time however it limits the agency of urban village residents to craft and interconnect space in alternative fashions. Less direct urban policing and regulation is also needed as a formalised landscape indirectly provides a narrowing structure on which to imbue and connect space together in broader moral geography. My interactions with iTaukei urban village residents in space during my return visit had a pall of constraint that differed from the defiant agency of my previous visit. This constraint, however, was overlaid with the same atmosphere of discontent concerning the pursuit of civic nationalism by the Fijian government but with less avenues to direct it.

8. Conclusion

The outright pursuit of the paramountcy of ethnic nationalism and citizenship has been successfully suppressed in post-coup Fiji by the Bainimarama-led government and their civic nationalist platform. This, however, does not mean that many iTaukei Fijians no longer pursued ethnic nationalism and citizenship. Large portions of iTaukei urban village residents pursue these ideals in less explicit ways that do not garner the attention of the Fijian state. I have presented in this article that iTaukei urban village residents actively create and connect places of ethnic value to other places in the city. For urban village residents who are disconnected from rural home islands or native villages, many of these sources include less traditional locations within the city that are imbued with adapted ethnic values. These less traditional locations include the abandoned house in the case of urban youth and Value City second-hand clothing bulk distributor for urban village women. iTaukei urban village residents attempted to connect the values explored in these places to other places in the city. The way these iTaukei urban village residents conceived of and interrelate space to claim ethnic ownership over the city can be conceived of within moral geography. This is because they are not only attempting to diffuse ethnic values from space into the city. They are also trying, in part, to contest current inclusive orientations of urban space pursued by the Fijian government since the final coup in 2006. On my return to Fiji in 2021–2022 I observed that the previous material infrastructures which iTaukei urban residents utilised had disappeared. The spaces they subsequently used in the formalising cityscape of Suva made their activities more observable and controllable as well as provided a narrowing structure to imbue and connect space together. While the formalisation of urban environments often brings benefits such as increased living standards, in these specific examples of “Magic City” and “Value City”, I argue that it came at the expense of exploring ethnic citizenship by iTaukei urban village residents.

Acknowledgements

The research of this article was part of a larger Australian Research Council (ARC) funded project “The Moral and Cultural Economy of the Mobile Phone in PNG and Fiji”, Australian Research Council Discovery Project (DP140103773), led by CI Heather A. Horst and PI Robert J. Foster. The writing of this article was supported with funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant agreement No. 802223). I would like to thank Robert A. Forster and John Cox for reading drafts of this paper and giving their academic advice. Lastly, I would like to thank the reviewers of this paper for their helpful recommendations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appadurai, A. (1995). The production of locality. In R. Fardon (Ed.), Counterworks: managing the diversity of knowledge (pp. 204–17). Routledge.

- Bossen, C. (2000). Festival mania, tourism and nation building in Fiji: The case of the hibiscus festival, 1956—1970. The Contemporary Pacific, 12(1), 123–154. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2000.0006

- Brimacombe, T., Kant, R., Finau, G., Tarai, J., & Titifanue, J. (2018). A new frontier in digital activism: An exploration of digital feminism in Fiji. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 5(3), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.253

- Brison, K. J. (2007). Our wealth is loving each other: Self and society in Fiji. Lexington Books.

- Carnegie, P. J., & King, V. T. (2020). Mapping circumstances in Oceania: Reconsidering human security in an age of globalisation. In Amin, S., Watson, D., Girard, C. (Eds.) Mapping security in the Pacific (pp. 15–29). Routledge.

- Connell, J. (2003). Regulation of space in the contemporary postcolonial Pacific City: Port moresby and Suva. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 44(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2003.00213.x

- Connell, J. (2007). The Fiji Times and the good citizen: Constructing modernity and nationhood in Fiji. The Contemporary Pacific, 19(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2007.0006

- Connell, J. (2018). Fiji, rugby and the geopolitics of soft power. Shaping national and international identity. New Zealand Geographer, 74(2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/nzg.12184

- Connell, J., & Lea, J. (1994). Cities of parts, cities apart? Changing places in modern Melanesia. The Contemporary Pacific, 267–309. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/12987

- Davidson, J., & Milligan, C. (2004). Embodying emotion sensing space: Introducing emotional geographies. Taylor & Francis.

- Deo, & Turaga, (2016, September 10). Abandoned house in Waimanu road destroyed in fire, Fiji Village, https://fijivillage.com/news/-Abandoned-house-in-Waimanu-road-destroyed-in-a-fire-52rks9/

- Dornan, M. (2020). Economic (in) security in the pacific. In Amin, S, Watson, D, Girard, C (Eds.) Mapping security in the Pacific (pp. 30–40). Routledge.

- Faier, L. (2013). Affective investments in the manila region: Filipina migrants in rural Japan and transnational urban development in the Philippines. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(3), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00533.x

- Farrelly, T. A., & Vudiniabola, A. T. (2013). Kerekere and indigenous social entrepreneurship. Sites: a Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies, 10(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.11157/sites-vol10iss2id243

- Foster R, J., & Horst H, A. (2018). The moral economy of mobile phones: Pacific Islands perspectives. ANU Press.

- Foukona, J. (2015). Urban land in Honiara: Strategies and rights to the city. The Journal of Pacific History, 50(4), 504–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2015.1110328

- Jansson, A. (2013). The hegemony of the urban/rural divide: Cultural transformations and mediatized moral geographies in Sweden. Space and Culture, 16(1), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331212452816

- Jones, P. (2016). The emergence of Pacific urban villages: Urbanization trends in the Pacific islands. Asia Development Bank (ADB).

- Kant, R. (2019). Ethnic blindness in ethnically divided society: Implications for ethnic relations in Fiji. Palgrave MacMillian.

- Kant, R., Titifanue, J., Tarai, J., & Finau, G. (2018). Internet under threat?: The politics of online censorship in the Pacific Islands. Pacific Journalism Review: Te Koakoa, 24(2), 64–83. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v24i2.444

- Kiddle, L., & Hay, I. (2017). Informal settlement upgrading: Lessons from Suva and Honiara. In Thomas, P, Keen, M (Eds.) Development Bulletin (Vol. 78, pp.25–29). Australia National University (ANU). https://crawford.anu.edu.au/rmap/devnet/devnet/db-78.pdf

- Kiddle, G. L., McEvoy, D., Mitchell, D., Jones, P., & Mecartney, S. (2017). Unpacking the Pacific urban agenda: Resilience challenges and opportunities. Sustainability, 9(10), 1878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101878

- Kraemer, D. (2013). Planting roots, making place: An ethnography of young men in Port Vila, Vanuatu. The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

- Kraemer, D. (2020). Planting roots, making place: Urban autochthony in Port Vila Vanuatu. Oceania, 90(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/ocea.5239

- Lasaqa, I. Q. (1983). The Fijian people before and after Independence. Australian National University Press.

- Lawson, S. (2004). Nationalism versus constitutionalism in Fiji. Nations and Nationalism, 10(4), 519–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.2004.00180.x

- Lefebvre, H. (1968 [1968]). Writings on Cities . In Kofman, E. & Lebas, E. (Eds.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Lindstrom, L. (2011a). Urbane Tannese: Local perspectives on settlement life in Port Vila. Journal de la Société des Océanistes, (133), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.6461

- Lindstrom, L. (2011b). Vanuatu migrant lives in village and town. Ethnology: An International Journal of Cultural and Social Anthropology, 50(1), 1–15. https://ethnology.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/Ethnology/article/viewFile/6089/6298

- LiPuma, E. (1998). Modernity and forms of personhood in Melanesia. In Lambek, M, Strathern, A (Eds.), Bodies and Persons: Comparative Perspectives from Africa and Melanesia (pp.53–79). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511802782.003

- Mausio, A. (2021). Spectre of neoliberal gentrification in Fiji: The price Suva’s poor must pay. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 62(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12272

- McAuliffe, C. (2012). Graffiti or street art? Negotiating the moral geographies of the creative city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00610.x

- McDougall, D. (2017). Lost passports? Disconnection and immobility in the rural and urban Solomon Islands. Journal de la Societe des oceanistes, 144-145, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.7764

- McDougall, D. (2017). Lost passports? Disconnection and immobility in the rural and urban Solomon Islands. Journal de la Société Des Océanistes, (144–145), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.7764

- Mosko, M. (2010). Partible penitents: Dividual personhood and Christian practice in Melanesia and the West. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 16(2), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2010.01618.x

- Newland, L. (2013). Imagining nationhood: Narratives of belonging and the question of a Christian state in Fiji. Global Change, Peace & Security, 25(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2013.784247

- Phillips, T., & Keen, M. (2016). Sharing the city: Urban growth and governance in Suva, Fiji. Australia National University (ANU).

- Pow, C. P. (2007). Securing the’civilised’enclaves: Gated communities and the moral geographies of exclusion in (post-) socialist shanghai. Urban Studies, 44(8), 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701373503

- Ratuva, S. (2015). Protectionism versus reformism: The battle for Taukei ascendancy in Fiji’s 2014 general election. The Round Table, 104(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2015.1017259

- Ratuva, S., & Lawson, S. (2016). The people have spoken: The 2014 elections in Fiji. anu Press.

- Singh, S. (2015). The evolution of media laws in Fiji and impacts on journalism and society. Pacific Journalism Review, 21(1), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v21i1.152

- Strathern, M. (1988). The gender of the gift. In The gender of the gift. University of California Press.

- Street, A. (2012). Affective infrastructure: Hospital landscapes of hope and failure. Space and Culture, 15(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331211426061

- Sykes, K. (1999). After the ‘raskol’feast: Youths’ alienation in New Ireland, Papua New Guinea. Critique of Anthropology, 19(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X9901900205

- Szadziewski, H. (2020). Converging anticipatory geographies in Oceania: The belt and road initiative and look north in Fiji. Political Geography, 77, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102119

- Thien, D. (2005). After or beyond feeling? A consideration of affect and emotion in geography. Area, 37(4), 450–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00643a.x

- Thomas, P. (2002). The river, the road, and the rural–urban divide: A postcolonial moral geography from southeast Madagascar. American Ethnologist, 29(2), 366–391. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2002.29.2.366

- Thornton, A. (2009). Garden of Eden? The impact of resettlement on squatters'‘agri-hoods’ in Fiji. Development in Practice, 19(7), 884–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520903122311

- Thrift, N. (2004). Intensities of feeling: Towards a spatial politics of affect. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x

- Trnka, S. (2010). The Jungle and the city: Perceptions of the urban among Indo-Fijians in Suva, Fiji. Urban Pollution: Cultural Meanings, Social Practices, 15, 86. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781845458485-006

- Trnka, S. (2011). Specters of uncertainty: Violence, Humor, and the Uncanny in Indo‐Fijian communities following the may 2000 Fiji Coup. Ethos, 39(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1352.2011.01196.x

- Trnka, S., & Trundle, C. (2014). Competing responsibilities: Moving beyond neoliberal responsibilisation. In Anthropological Forum (Vol. 24. 2) (pp. 136–153). https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2013.879051

- Van Liempt, I., & Chimienti, M. (2017). The gentrification of progressive red-light districts and new moral geographies: The case of Amsterdam and Zurich. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(11), 1569–1586. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1382452

- Walsh, A. C. (1978). The urban squatter question: squatting, housing and urbanization in Suva, Fiji: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography at Massey University (Doctoral dissertation, Massey University).

- Watt, L. . (2020). Fijian infrastructural citizenship: Spaces of electricity sharing and informal power grids in an informal settlement. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1719568. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1719568

- Weber, E., Kissoon, P., & Koto, C. (2019). Moving to dangerous places. In Klöck, C., Fink, M. (Eds.), Dealing with climate change on small islands: Towards effective and sustainable adaptation? (pp. 267-291). Göttingen University Press. https://doi.org/10.17875/gup2019-1220

- Widmer, A. (2013). Diversity as valued and troubled: Social identities and demographic categories in understandings of rapid urban growth in Vanuatu. Anthropology & Medicine, 20(2), 142–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2013.805299

- Williams, R. (1973). The Country and the City. Oxford University Press.