Abstract

Artisanal Small-Scale Mining (ASM) in rural northern Ghana provides significant income earning opportunities for young men and women. However, little is known about the role of ASM in the imagined futures of these young people. This paper draws ghhon a qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions held with 35 rural youth to fill this information gap. Data were analysed using the thematic analysis approach. The findings show that rural young miners imagine a future in which ASM would not be their mainstay of employment. Instead, ASM is viewed as a means to accumulate money to either restart or further their education, secure professional employment, or to establish their own business. Finance together with unforeseen life events and hazards such as accidents, death, illness, and injuries are cited by all respondents as key challenges that might make it impossible for them to realise their imagined futures. These findings have important implications for policies seeking to promote youth employment in rural Africa

1. Introduction

Artisanal and small-scale mining has been noted to be a key sector that provides employment opportunities for diverse groups of young people including secondary school dropouts, students, low-skilled youth, migrants, and even university graduates (Arthur-Holmes et al., Citation2022). Recent research highlights the exponential growth of young people engaged in ASM owing to a lack of employment opportunities in formal employment, and poor school-to-work transitions (Arthur-Holmes et al., Citation2022; Osei et al., Citation2021). This paper explores the futures that rural youth engaged in ASM imagine for themselves, and whether ASM would play any role in these future imaginaries.

Research interest in the African youth and policies for their development has been on its ascendency over the past decade (Sumberg & Hunt, Citation2019). This has been necessitated by Africa’s “youth bulge” which is often described both as a potential threat to governments (especially) and other stakeholders if not managed well (Honwana & De Boeck, Citation2005;; Mueller & Thurlow, Citation2019), and as a potential for development when this resource is well harnessed (Fox, Citation2019). The youth represent a high proportion of populations of the developing world, this is especially the case for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where the youth make up nearly a third of the population (Mueller & Thurlow, Citation2019).

Nevertheless, both governments and the private sector are finding it difficult to harness the tremendous resources and energies of the youth through the provision of secure, remunerative, and productive employment that meet the expectations, qualifications, and ambitions of young people themselves. Thus, unemployment and under-employment, which affect millions of young people in SSA, appear to be key developmental challenges. Youth unemployment remains a daunting task for governments and with nearly 10–12 million young people joining the workforce every year, the youth employment challenge remains (African Development Bank, Citation2016

The situation is especially difficult in rural Africa where most of the poor people live along with young people with limited job (creating) opportunities (Mueller & Thurlow, Citation2019). As opined by Filmer and Fox (Citation2014), research on young people living in rural areas is necessary because they will continue to rely on the agricultural sector as their main source of income for several decades to come (Mueller et al., Citation2018). Indeed, as of 2018, the chief employment booster was the agricultural sector, which generates nearly 68% of rural household income (Fox, Citation2019).

Despite the significant contribution of the agricultural sector to rural household income, there is a growing body of research that highlights the fact that young people are detaching themselves from agricultural production although recent studies have presented more mixed results (Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). Two common proposals are put forward to help explain the disinterest of rural youth in agriculture. The first relates to the drudgery of agriculture and the second to the rising expectations of rural youth for professional jobs (Leavy & Hossain, Citation2014; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). The second relates to the difficulties young people encounter in accessing the productive resources (land, capital, and inputs) necessary to engage in agriculture (Andersson Djurfeldt et al., Citation2019; Bezu & Holden, Citation2014). It is also important to underscore that many rural youth in Africa are building livelihoods beyond agriculture as rural areas are undergoing transformations, albeit slow (Christiaensen & Demery Citation2018; Fox, Citation2019). Clearly, in present discussions on rural development in Africa, young people, agriculture, and rural transformation are entwined (Sumberg & Hunt, Citation2019).

One of the non-farm avenues “pulling” rural youth is artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) which is offering several thousands of young people with direct employment and other indirect benefits (Osei et al., Citation2021). On the one hand, the literature on youth engagement in ASM focuses on the socio-economic relevance of ASM operations to its participants (Hilson, Citation2016; Hilson & Osei, Citation2014; Kamlongera, Citation2011; Maconachie, Citation2011; Osumanu, Citation2020) and on the other, the environmental implications of ASM activities in general (Armah et al., Citation2013; Ofosu et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, Hilson and Osei (Citation2014) note that in cases where there are limited alternative income earning activities such as grasscutter rearing, beadmaking, and basket weaving, low incomes from these sources make ASM very attractive and could form part of a strategy that provides employment for the teeming unemployed youth.

There, however, remains a dearth of knowledge on how rural youth are navigating the opportunities ASM presents them and their long-term plans. Some studies report that rural youth in general have high aspirations for future employment (OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), Citation2018), although little is known about how rural young people engaged in ASM activities imagine their own futures in general. Some studies have examined how the ASM sector could be re-imagined for poor young women and men, and the available alternative livelihood strategies for Ghana’s young artisanal miners (Arthur-Holmes et al., Citation2022; Tschakert, Citation2009). The work of Tschakert (Citation2009) highlights that young artisanal miners are unlikely to commit their futures to alternative livelihood strategies (such as batik making, mushroom and snail farming, fish farming, grasscutter rearing, palm production) proposed by external development agencies as long as they can expect to legitimately acquire a small parcel of land for gold mining. Arthur-Holmes et al. (Citation2022) draw attention to how ASM offers opportunities for young migrant women from poorer northern regions of Ghana to earn income (money) to learn a trade or vocation (including bead making, hair dressing, and sewing). However, these studies were all conducted in the southern part of Ghana. Our research builds on these earlier studies by concentrating attention on an ASM community in the Northern part of Ghana away from the research fatigued ASM communities in the mining belt of the Southern part of the country. Specifically, the current study seeks to address the following three research questions: Do young miners envisage continuing their engagement in ASM in the future? What is the role of ASM in the imagined futures of young miners? and What constraints do young miners envisage might hinder the realisation of their imagined futures?

In this paper, our point of departure is that despite the negative environmental and populist sentiments associated with ASM activities, there remain significant opportunities in the sector for young people to attain markers of responsible adulthood. Therefore, it might be expected that rural young people engaged in the sector would imagine a future in which ASM will play a crucial role. The research presented in this paper focuses on the futures that young people engaged in ASM imagined for themselves, how they make sense of their current engagement with ASM and whether ASM would have any role to play in their transition to adult futures. We draw on qualitative interviews and focus group discussions conducted with 35 young people engaged in ASM activities in three rural communities located in the Talensi district in the Upper East Region of Ghana. What emerges from a variety of backgrounds is that rural youth imagine a future in which ASM would not be the mainstay of employment. Instead, ASM is viewed as a temporary livelihood strategy with which rural young people engage to accumulate the means to either restart or further education and secure professional employment. Young miners also imagine a future in which they will establish their own businesses, and use their resources, influence, and capacity to support the welfare and wellbeing of community members by creating employment opportunities for others and supporting family members. Finance together with unforeseen life events and hazards such as accidents, death, illness, and injuries were cited as key challenges that could hinder young miners (both male and females) from realising their imagined futures. The findings of this research contribute substantially to the literature on youth transitions, and the future making of Africa. The findings suggest the need for formalisation reforms and policies of ASM to consider the futures imagined by rural young people engaged in ASM.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the notion of imagined futures as a framework for understanding the futures that young miners imagine for themselves. Section 3 introduces the research methodology and includes details of the research site, context, the sample of young miners and other workers at the sites. Section 4 presents the research findings followed by a discussion of the key findings in section 5. Section 6 provides the conclusions and policy implications.

2. Framing the imagined futures of young people

The literature on rural young people’s aspirations in SSA is relatively well developed (Anyidoho et al., Citation2012; Leavy & Hossain, Citation2014; Leavy & Smith, Citation2010; Locke & te Lintelo, Citation2012; Verkaart et al., Citation2018; Yeboah, Citation2021; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). Nonetheless there are notably only a handful of research focusing specifically on the imagined futures of young people engaged in ASM in rural Africa (Osei et al., Citation2021). While the concept of aspirations may encompass the hopes, dreams, and reflections of young people, it has been criticised for being vague, often lacking conceptual clarity, and failing “to draw a compelling link between future goals or outcomes and young people’s agentive efforts to work towards them” (Hardgrove et al., Citation2015, p. 163). Therefore, imagined futures have been proposed as an alternative framework to aspirations (Hardgrove et al., Citation2015; Markus & Nurius, Citation1986). The idea of the future considers imagined futures as something that young people do and not only something young people have or will have in the future (Patel, Citation2020). Fundamentally imagined futures are framed along lines of relational perspectives that attend to youth agency, intentionality and are located within a socially constructed experiences both by past and present circumstances (Evans, Citation2016; Yeboah et al., Citation2021). This is in line with the understanding of the future “not as a distinct and disconnected temporality but a horizon that is the assemblage of past and present temporalities” (Coleman 2008 as cited in Carabelli & Lyon, Citation2016, p. 1112).

The work of Hardgrove et al. (Citation2015) highlights two key aspects of the imagined futures literature. The first strand identifies the relationships that exist between young peoples imagined future selves and how these are shaped by their structural position within a given context (Vigh, Citation2009; Yeboah, Citation2021). In a sense, this highlights imagined futures as a product of young people’s own “perceived structured positions in society” (Hardgrove et al., Citation2015, p. 164). Focusing on how Bissau youth survive and move into their imagined futures, Vigh (Citation2009) describes a “global awareness from below” (p. 93) and draws our attention to how young people imagine themselves in relation to social options and spaces often shaped by differential level of access. Vigh also signals how young people’s individual motivations, agency, hopes, and trajectories are shaped by the social context within which they find themselves.

The second strand of literature highlight the “internalised socio-cultural values” that young people uphold as they move from the present to the future in line with their lived experiences and values of family and socio-cultural context (see, Cole, Citation2011; Hardgrove et al., Citation2015; Patel, Citation2020). Cole (Citation2011) reports how desires of young women entering the sexual economy as a pathway to attain respectable adulthood and social mobility is shaped by traditional norms and values that frown on such practices. This highlights a kind of mental picture that young people hold as they plot and sketch their future lives (Hardgrove et al., Citation2015). From a Bourdieusian perspective, this reflects that the imagined futures of young people are anchored on the value systems that illuminates a particular field and provides important insight into the socialisation processes of young people (Bourdieu, Citation1984). It also reflects the significance placed on differential capitals (cultural, social, economic, and symbolic) in influencing young people’s expectations, life choices, and imagined futures (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992). Taken together, this body of scholarly work highlights how young people and older generations are constantly imagining and making plans ahead of their futures in social spheres such as education, employment, and health (Ansell et al., Citation2014; Crivello, Citation2011). In this connection young people’s transition to their imagined futures are “experienced in the immediate, but they are also about movement toward the futures” (Hardgrove et al., Citation2015, p. 164).

Research that attends to young people’s imagined futures has been well documented in the field of education, and studies that focus on transitions from school to work (Hardgrove et al., Citation2015; Stahl et al., Citation2020). As Stahl et al. (Citation2020) note, the notion of imagined futures lends itself to gendered constructions of possible selves, and the forms of masculinity and femininity that are privileged in the social context of youth livelihoods. Nonetheless, an imagined future is not confined only to livelihood trajectories. It can encompass any aspect of a wide range of intentioned future experience and identity. Based on such understandings, the central aim of our research was to seek out how rural youth engaged in ASM imagined their future lives.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Research site

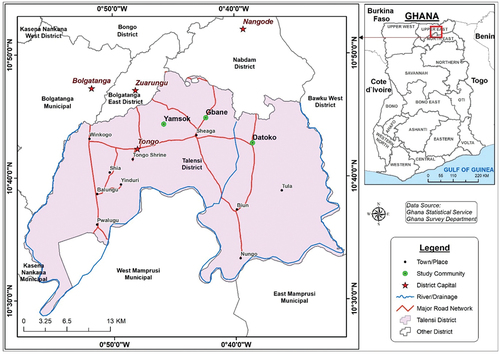

The scope of the study was confined to three mining communities, namely YamSok, Datoko, and Gbane within the Talensi District in the Upper East Region of Ghana (Figure ). These communities were selected because of the presence of young people engaged in ASM activities. Taken together, the three communities serve as a hub for ASM activities within the district (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). According to the latest round of Population and Housing reports by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), the population of Talensi is estimated to be 87,201 and Talensi is one of the few districts where the population of males and females is almost the same. Additionally, Talensi District remains very rural with an estimated 88% of the population living in rural settings Citation2021 and engaging in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries (78%) (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021). Agriculture is therefore the main source of income for households in the district (Ministry of Finance, Citation2020). Some of the crops grown include tubers, vegetables, and legumes, as well as non-traditional export and irrigated crops. Specifically farmers in Talensi produce maize, millet, sorghum, rice, soybean, shea nuts, onion, tomatoes, and pepper. These crops are produced during the long dry season, which stretches from October to April. A considerable number of farmers also engage in livestock production. In fact, livestock rearing comes second after crop farming in the district and the types of livestock reared include chicken, Guinea fowl, sheep, cattle, and goats (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Map showing Dakoto, Yamsok and Gbane communities and upper east region of Ghana.

The mining and quarrying industry is the second highest employer providing employment for about 5.2% of the population (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). The presence of mining companies such as Shaanxi, Cardinal Resources, and Cassiuning, coupled with the substantial gold deposits in the area and the numbers already involved in mining gives an indication that the industry will thrive for decades to come (Tangonyire & Akuriba, Citation2020).

3.2. Methods and data

Two main methods were used in gathering data including semi-structured interviews with individuals and focus group discussions (FGD). First the research involved semi-structured interviews with 35 young people who were purposively selected from across the three mining sites in Talensi district. The young miners were purposively selected based on the following criteria: at least one year of engaging in ASM and native (rural) of the selected communities. The young miners interviewed comprised of 20 males and 15 females.

Without taking any specific strand on imagined futures of the sample, the interviews and focus group discussions were used to elicit information on how the sampled individuals imagined their futures in general. In addition, the interviews gathered detailed information on the background of participants, their motivations for entering ASM, their specific work at the mine, general challenges they were facing in their lives along with available livelihood opportunities for young people in the study areas, and constraints to realising future ambitions.

Three separate FDGs followed the individual interviews to learn more about key issues and themes that emerged from the individual interviews. The FGDs afforded participants the opportunity to comfortably articulate their motivations for entering ASM, how they made sense of ASM, the futures they imagined themselves and the constraints to realising their aspirations along with their peers and work mates. ‘This research strategy also presented the research team the opportunity to delve deeper into the subject matter and acquire better insight into youth participation in ASM in general. We also carefully took context into consideration during interviews and group discussions because as admonished by White (Citation2019, p. 11), “the context in which young people are asked about their aspirations may influence the imagined engagements with the future that they articulate in their answers”. By this, we ensured that our discussions were conducted devoid of the presence of parents or guardians and older miners. The interviews were conducted in an open and informal manner which allowed us gain deeper insight into the imagined future selves of the young miners. Capturing the voices of young people in this way allowed us to carefully consider their imagined futures in their transition to adulthood. All the interviews and focus group discussions took place at the mining sites, and this made the interviewees more comfortable with the interview process. It further accorded the research team the opportunity to observe the day-to-day activities and business at the mining sites, which enhanced the field notetaking experience.

3.3. Data analysis

With the permission of the research participants, the individual interviews and focus group discussions were audio recorded. This allowed us to capture the narratives of the young miners in detail. The audio recordings were transcribed, and the transcribed text was compared several times with the audio recordings to ensure accuracy. A coding frame which contained codes and sub-codes was developed inductively from the interview transcripts and this enabled us to code the interview transcripts. The coding process was iterative. It involved careful and repeated reading of the transcribed texts, reorganisation of codes where necessary and linking the data to questions that was asked during the data collection. The thematic analysis technique was then employed to analyse the data. This involved providing detailed interpretation of closely related statements, expressions, and patterns as they emerged from the participant responses.

4. Findings

4.1. Background of research participants

The ages of the 35 young miners interviewed as part of this research ranged from 15 to 24 years. Twenty-two (22) said that they were single, whereas the remaining 13 were married. In terms of their educational attainment, 18 were Junior High School graduates, 11 had Senior High School education, 5 were primary school graduates while only 1 had completed tertiary education. The majority (29) reported that their parents were farmers while (6) said their parents engaged in petty trading. All the participants had been engaged in ASM for at least one year.

The next part presents the findings on the activities engaged in by young miners including how they make sense of their activities, before returning to findings on the futures that young miners imagine for themselves.

4.2. What are young people doing and how do they make sense of what they are doing?

4.2.1. Available occupational niches in study communities

The interviewees detailed a range of formal and informal sector employment opportunities available to young people across the three sites, from artisanal small-scale mining, government work, food vending, marketing and trading of agricultural produce, masonry, bakery, dressmaking, carpentry, hairdressing and to a greater degree farming as the main avenues for employment. Despite the existence of these livelihood options, interviewees noted that only a few of the available employment opportunities are deemed to be financially rewarding. This is exemplified in the words of a 22-year-old young man who asserted that government work, ASM (galamsey) and farming are the three main livelihood options that provide viable incomes:

what I’m saying is that, in this community it’s either you farm, or you work at the galamsey or you are a government worker. Apart from that I don’t think you can get money in anything.

4.2.2. Activities engaged in by young miners

Despite this view, none of the young men and women interviewed across the three sites were engaged in government work or agriculture (farming) as an economic activity at the time of the field research and all reported being engaged in artisanal small-scale mining activities with no secondary occupation. Nevertheless, a significant gender division in the type of work actually undertaken was reported. Young men were found to be engaged in activities that require enormous physical strength including using various tools to crack, process, and extract small pieces of gold ore. One 19-year-old interviewee described the work of the young men at the mining site as follows:

We have those [young men] who do the blasting, followed by the chiselers; those who drill the holes are also there. You only have to start the machine for them to drill the holes then the blastmen get into the holes to blast; this is followed by the locum boys before the chiselers. The chiselers try to dismantle the cracks from the blast because during the blast not everything explodes so the chisel work is done.

On the other hand, in addition to running errands and fetching water, stones or sand, young women engaged in selling food, water, and snacks at the mining site. They regarded the sale of food, water, and snacks as a profitable venture since there is always good patronage from the miners. A 21-year-old young woman noted:

For me I sell this pito and water. My main customers are the men who are doing the work here. I want to make some money so that when my school results come, I will go to school.

One young man indicated that he was not directly engaged in the ASM activities but only sell snacks and alcohol at the mining site.

As for me I’m a businessman. I don’t go down into the pit, I only sell these things … snacks and alcohol.

There is little if any indication to suggest that the young peoples’ motivation for entering ASM differed by gender, location, age, or even educational attainment. Across the three sites, young men and women linked their motivations for entering their current economic activities to the disappointment with their schooling careers and the need to make money to pursue/further their education or start business ventures. One 18-year-old female interviewee narrated her motivation for entering ASM as follows:

I was an apprentice in Kumasi but couldn’t complete my training. I needed money so I came to make some money and complete it.

Another interviewee, a 24-year-old young man who had completed Junior High School and was looking at the possibility of establishing a barbering saloon indicated that his main motivation for entering ASM was to accumulate the needed funds to put up a structure and purchase the needed tools to begin his barbering business.

I needed money to set up my barbering business that’s why I came here. I don’t have money to buy the necessary items needed for the business. If you don’t have money how can you set it up? These are some of the problems. Someone can barber but is not having money to put up his store and buy tools. I for instance, if I get a barbering shop I will like it but where is the money to start it?

A 22-year-old Senior High-School graduate interviewed indicated that he needed to raise enough money to be able to cater for his tertiary education, and therefore saw his engagement in ASM as a strategy to raise the needed funds to support his education:

You know now when you get to the training colleges, you are paying fees almost every semester … you get that? The universities too you are paying so before you go you have to make sure that you get the money that can pay your admission and maybe for 6 semesters. If your parents are paying the school fees then you have to buy the other things yourself. So if you don’t make that much money and just go in there, you are likely to come home to do the mining but if you are able to make the money at least you will be there, the money can sustain you. By the time the money will be finishing, at least you will also be completing the school.

The views of the interviewees quoted above exemplify the stories foretold by nearly all the young men and women interviewed in the three communities who indicated that their motivations for entering ASM was mainly to accumulate the needed money to either establish business ventures or restart or further their educational pursuit to realise their dream employment. One interviewee noted that he was hoping to enter the military service having submitted his application when this research started. However, he decided to engage in ASM to raise the needed cash while waiting for the outcome of his application. During the focus group discussion, he stressed:

I picked some forms and registered but for now I haven’t heard anything from them. So, for now I’m at the mining area managing to get some money. Yeah I applied to the army … military; but I haven’t heard anything from them so now I found myself at the mining area doing something small here.

One 24-year-old young man who had primary education suggested that ASM (galamsey) is the only work he knows and does and therefore had no plans to quit anytime soon. He was of the view that he could not look elsewhere for any job other than galamsey given that he has no school certificate. He saw galamsey as the work he will do in the foreseeable future.

4.3. The imagined futures of young artisanal miners

The imagined futures of the young men and women engaged in ASM revolved around three themes. These include i) to further or restart education to gain professional employment mostly based in urban areas; ii) to establish small-scale businesses; and iii) to become a responsible and respected person in the community.

4.3.1. Furthering education to secure professional employment

A consistent theme from the interviews is that many young people had to halt their formal education due to as financial constraints. Therefore, across the study sites, a central feature of the futures that young miners imagined for themselves was to further their education, at least up to the tertiary level to enhance their prospects of securing formal sector employment. Overall, additional education was more likely to be central in the imagined futures of the young men, individuals who were relatively younger (less than 20 years) as well as those who had completed Senior High School. Young miners including those who had passed their West African Senior High School Certificate Examinations (WASSCE) , and those who had dropped out because of financial constraints, considered education as key to gaining professional employment. The specific jobs mentioned included being a lawyer, teacher, nurse, soldier, agricultural extension officer, banker among others. The desires of wanting to secure formal sector employment was rooted in the perceptions of respondents that formal sector jobs offer attractive incomes, job security and societal respect. For example, a 22-year-old young man who had completed Senior High School suggested he would want to further his education to university level to pursue a Bachelor of Law degree and become a lawyer. He saw the law profession as one that would offer societal respect, prestige, and good financial reward:

I want to go to university. I am targeting a law degree so I can become a lawyer. You know that when you come out …; you know, mostly though you have to have a reason for going to the university or err everybody wants a place where he can get money and respect.

A 23-year-old young man who operates the grinding machine at the mining site at Gbane community and had completed Senior High School indicated that he entered ASM mainly to accumulate resources to go back to school. He indicated having passed his examination but had poor grades in mathematics and social studies, and therefore would like to go back to school to better his grades and secure formal sector employment:

As for passing I passed very well. Only maths and social studies is not very good but as for school I’m willing to go back to school. For now, I am working here so I can get some money so that I can go back to school and get a good job.

A 19-year-old female also narrated that she would want to further her education to become a nurse in the future. She sees the nursing profession as rewarding and fulfilling in the sense that she knows some members of her community who are professional nurses and are making it in life.

I wanted to go to the nursing training but if I cannot afford the nursing training I can look at teacher training. The nurses I know in this community are respected and they are doing well so I want to become one.

4.3.2. Establish businesses

The young miners also imagined a future in which they would establish their own businesses. Many young miners suggested that they were working hard to accumulate much needed capital to establish their own economic ventures that could sustain both themselves and their families in the foreseeable future. Overall, desires to establish a business were more likely to be central in the imagined futures of the young women than young men, but also included individuals who had dropped out of school or had never attended school. The specific self-owned businesses mentioned by our respondents included barbering and hairdressing, dressmaking, tailoring, running a bakery and other informal sector employment opportunities such as the sale of electrical appliances. Some interviewees narrated their aspirations of wanting to establish their own ventures as follows:

I am doing this galamsey so that when I get money I will use it to learn tailoring. As for my community in Datoko, there are not many tailors, so I think it is good. Anywhere I can get, I will just start, but I would like to start at Datoko. I will need GHC700 to learn it and I will need 3 years. That amount includes the sewing machine, which is about GH300, then I will need the chair and scissors, and the lessons I will take. All that adds up the GH700 I need to pay.

As actors who are in tune with their social worlds, young people, and particularly the females who aspired to establish themselves as hairdressers and dressmakers recognised that they would need to undergo training to learn the skill needed to get them started, and therefore finance to pay for apprenticeship training and buy the necessary items (e.g. sewing machine) was fundamental. One 24-year-old woman who never attended school and was engaged in selling food items at the mining site aspired to establish herself as a dressmaker. During the interview, she mentioned that for her to establish herself as dressmaker would require of her to learn the trade of dress making through apprenticeship training:

I want to establish myself either as a dressmaker or hairdresser but I need money to learn it so I am doing this work to gather money for apprenticeship.

4.3.3. Becoming responsible members of their community

The young miners also imagined a future in which they would become responsible members of their communities. Many highlighted that they would want to grow up and serve members of their communities well. This would entail using their resources (money and time), influence, and power to support community development through, for example, undertaking volunteerism and setting up businesses to employ other youth in the community. This view was commonly central in the imagined futures of the young men, as well as those with relatively higher educational attainment. One 20-year-old young man who had completed Senior High School and was looking for the opportunity to move into tertiary education in the near future mentioned:

I want to grow and have enough resources (money) so that I can open businesses and employ some of the young people in this community who are unemployed. Here you can see that the youth struggle a lot because there are no jobs, so I want to help in the future.

Others dreamed of being responsible by taking care of their family members and other people outside of their family domain:

One problem in this community is poverty. There are no jobs. People do farm work but there is no money in it. What to eat and wear is a problem for many individuals and families. So I hope that when I grow I can support my family members who want to attend school or learn a trade

4.4. Constraints to moving towards imagined futures

4.4.1. Lack of financial capital or credit

The young miners recognised that for them to move towards realising the futures they imagine for themselves would require navigating a variety of constraints of which the most commonly cited was a lack of financial capital or credit. This is quite unsurprising giving that poverty is a common challenge within mining communities, and is the reason why young people enter ASM. Financial constraints were regarded by both young men and women as one key factor that led to their inability to further their education. In all cases, financial resources would be needed whether to further or restart schooling to enhance prospects of securing formal sector or professional wage employment, or even to undergo apprenticeship training to become a seamstress, hairdresser or establish small-scale businesses. A 24-year-old young man who operates a grinding machine at the mining site narrated how poverty in the community is likely to impact on the futures that young people at the mining sites imagine for themselves as follows:

hmm there is poverty here … many are poor. For some of them, the parents can’t get money to help them. They have to go and work and get money for themselves to go to university. If they are not going to work, nothing [opens palm to mean they won’t make anything] … they won’t do anything. They cannot teach, they cannot become a nurse, they can’t do anything. They have to go to university before. Am I lying?

A 19-year-old male who was keen to establish a business in the future, also recognised finance as a constraint:

If you don’t have money you cannot do anything … you can always think of a business but you need money to start tha,t so it is good you get the money, and it is the galamsey that will give you the money.

An 18-year-old female who wanted to establish herself as a dressmaker bemoaned the lack of financial support which compelled her to enter ASM to accumulate resources before she could set herself up. She recognised having to temporally abandon the apprenticeship training to work in the mine site as a distraction. For her, if she had someone to support her financially, she would not have entered ASM in the first place:

Yes, I would like to establish myself as a dressmaker, but like I previously said, you need someone to take care of you. When you have such help, you can learn the trade without any distractions. But without a helper, you will always want to come back and make some money before you go to complete. And that is how you are distracted from learning the trade and never get to complete the course.

4.4.2. Hazards and unforeseen life events

For some young men and women, moving toward the future would mean navigating unforeseen circumstances or events including injury at the mine site, illness, death of a parent or family member, accidents, and other unexpected events. For example, some of the young men interviewed recognised that ASM work is extremely demanding, and many had sustained various physical injuries in the past. Others, including both males and females acknowledged that it is not possible to move to their imagined futures in the event of prolonged illness. Nevertheless, they also recognised that with determination, hard work and God on their side, they can achieve their imagined future selves.

5. Discussion

The central role that ASM has played and continues to play in offering income earning possibilities for rural young people cannot be overly emphasised (Osei et al., Citation2021; Arthur-Holmes et al, Citation2022). Therefore, we started this research on the basis of the premise that the sector might be central in the imagined futures of rural young miners (Hilson, Citation2016; Hilson & Osei, Citation2014; Osumanu, Citation2020). While we did not take any specific strand on imagined futures, narratives of our participants focused more on education, workforce opportunities and employment prospects in the future than anything else. However, the startling revelation of our findings is that young people engaged in ASM activities imagined a future in which ASM may not be their mainstay for employment or livelihood building. Instead, young men and women mentioned using ASM as a temporary livelihood strategy to accumulate the needed resources to pursue their imagined futures. Having been buffeted by poverty and financial constraints, the young men and women engaged in our survey were compelled to drop out or were unable to further their education beyond Senior High School. Despite these disappointments relating to formal education, the quest to restart or continue their education, obtain a degree certificate, and join or succeed in formal employment that is mostly based in urban areas, and relish the associated social and finance rewards, figure prominently in their imagined futures (see also, Leavy & Smith, Citation2010; Sumberg et al., Citation2017; Yeboah & Flynn, Citation2021). The ways in which young people expressed desires for government and formal sector employment reflect a prevailing norm and the socialisation of the African child where much respect, public recognition and prestige is accorded to different kinds of professional employment mostly based in urban environments, and a general displeasure or lack of recognition for informal sector work, such as ASM or the rural economy more broadly (see also, Yeboah et al., Citation2021). Perhaps, this dissatisfaction with rural informal sector work or the negative public perceptions of ASM in Ghana may help explain the absence of ASM in the imagined employment futures of young miners and must be reversed if young miners are to flourish in the sector (see Tschakert, Citation2009).

The reality, however, is that having a school certificate does not always guarantee securing formal or professional wage employment. As Carreri (Citation2021) writes, today’s younger generation, including even university graduates, are transitioning into adulthood with little or no expectation of employment or secure working conditions and as (Yeboah et al. Citation2021; Baker et al., Citation2021; Damoah et al., Citation2021) argue, it is more useful to learn other skills or consider a wide range of employment avenues including those found in the informal sector as a fall-back position. If success at school in fact only provides a tiny minority of rural youth with livelihoods that meet their imagined futures, then it becomes apparent that young people’s engagement in ASM may be one important option for decades to come.

Moreover, young men and women interviewed also imagined a future in which they will establish themselves as owners of businesses. The businesses reported in their imagined futures included establishing a grocery shop, the sale of electrical appliances and hairdressing among others. In most cases, the scale of these businesses is often small and, in this sense, young miners are envisaging what has been prescribed in the dominant policy narratives as key to addressing youth unemployment in Africa. In most policy circles, the turn to entrepreneurship or the individualisation of responsibility that calls on young people to consider establishing their own ventures to address unemployment appear to be more common in youth employment policies and programmes. In fact, many young people in several African countries, including Ghana, “consider entrepreneurship to be a good career choice” (Kew, Citation2015, p. 31). Before setting down this path however it is important to underscore the many structural barriers that inhibit small-scale businesses to thrive in Ghana such as the lack of marketing opportunities, limited financial capital, energy and power crises that have led to the collapse of several businesses (Mensah et al., Citation2019). Moreover, while the establishment of small-scale enterprises in the future may allow young people to be economically productive, it is too often associated with limited financial reward and job insecurity (Langevang et al., Citation2015; Yeboah et al., Citation2017).

Finally, some of the young miners and particularly the young men with some level of education expressed the view that they would want to become responsible members of their communities, setting up businesses to employ other members of their communities and support family members. While this looks like a highly ambitious project, concerns around poverty, financial constraints and the lack of a social support system that can offer employment and other opportunities for self-advancement for young people in the research sites appear to have fuelled their imagined futures along this path. The potential of young miners to realise this dream may allow them to construct new social identities as respectable individuals and gain high social status and recognition within their communities. But would the young miners be able to mobilise their resources and energy to realise this imagined future project?

6. Conclusion and policy implications

6.1. Conclusion

This paper examined the imagined futures of rural young people engaged in ASM activities. Overall, the picture that emerges is that young people are motivated to engage in ASM mainly as a short-term livelihood strategy to mobilise the needed resources, and especially financial capital, to move towards their imagined futures. In most cases, the desire to restart or further their education or join the formal world of work figure prominently in the imagined futures of both young men and women currently engaged in ASM activities. Young miners also imagined a future in which they would establish their own businesses but, in most cases, the imagined businesses are largely informal and small-scale enterprises. Becoming responsible members of their communities by using their influence, resources and capacity to support the development and welfare of other young people figure also in their imagined futures. How well their current livelihood strategy would serve them, and who amongst the young miners will be able to realise their imagined futures in decades to come are important areas for future research. Moreover, financial constraints together with unforeseen life events and hazards such as accidents and illness were cited as key challenges.

While there is recognition in both policy and public discourse that education can provide young people with skills to facilitate their entry into the labour market and enhance employment prospects, the reality is that success at school does not necessarily guarantee successful entry into the formal labour market. It is not in any way being suggested that the young miners involved in this research, and presumably several others who see education as the path to realise their dream of securing professional employment will not be able to attain their imagined future jobs. However, given the limited capacity of the formal sector to absorb all new labour market entrants, the mining sector could be supported as a good starting point.

6.2. Policy implications

The findings of this research have two important implications for policies seeking to promote the interest of young people engaged in ASM activities. First, the fact that many young miners imagined futures in which they will pursue higher education and secure formal sector wage employment highlight again the need to address access to, and quality of education both in the short and long term. Importantly, there is a need to address the cash cost that put higher education out of the reach of rural young people and align school curriculum to the changing demands and expectations of the labour market. This will require investment in technology and teaching of new and different set of competency-based skills that are in demand in the formal labour market.

Second and even more crucially the findings highlight young miners’ desire to establish small-scale businesses and entrepreneurship as way out of the temporalities of ASM. Nonetheless, this entrepreneurial drive cannot be sustained on individual responsibility alone, and requires a supportive climate furnished by the state to sustain them. In this regard, government policy reform in the ASM sector would need to consider providing the necessary enabling environment for young miners willing to establish themselves as entrepreneurs to thrive. This would require addressing the structural barriers through enhancing youth access to financial capital, productivity and viability of micro-enterprises, market linkages, macro-economic instability (inflation) and power crisis. Efforts must also be geared toward equipping rural young miners with knowledge and skills in business plans preparation and processes of registering a business, financial literacy and management skills to enable young people sustain their businesses. Until and unless these issues are addressed, young miners may have to continue to engage in ASM for decades to come.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adaawen, S. A., & Owusu, B. (2013). North-south migration and remittances in Ghana. African Review of Economics and Finance, 5(1), 29–15. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aref/article/view/104954

- African Development Bank (2016). Jobs for Youth in Africa. Catalysing youth opportunity across Africa. Accessed online at https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Images/high_5s/Job_youth_Africa_Job_youth_Africa.pdf.

- Andersson Djurfeldt, A., Kalindi, A., Lindsjö, K., & Wamulume, M. (2019). Yearning to farm – Youth, agricultural intensification and land in Mkushi, Zambia. Journal of Rural Studies, 71, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.08.010

- Ansell, N., Hajdu, F., van Blerk, L., & Robson, E. (2014). Reconceptualising temporality in young lives: Exploring young people’s current and future livelihoods in AIDS‐affected Southern Africa. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(3), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12041

- Anyidoho, N. A., Leavy, J., & Asenso-Okyere, K. (2012). Perceptions and aspirations: A case study of young people in Ghana’s cocoa sector. IDS Bulletin, 43(6), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00376.x

- Armah, F. A., Luginaah, I. N., Taabazuing, J., & Odoi, J. O. (2013). Artisanal gold mining and surface water pollution in Ghana: Have the foreign invaders come to stay? Environmental Justice, 6(3), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2013.0006

- Arthur-Holmes, F., Busia, K. A., Vazquez-Brust, D. A., & Yakovleva, N. (2022). Graduate unemployment, artisanal and small-scale mining, and rural transformation in Ghana: What does the ‘educated ’youth involvement offer? Journal of Rural Studies, 95, 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.08.002

- Baker, S., Due, C., & Rose, M. (2021). Transitions from education to employment for culturally and linguistically diverse migrants and refugees in settlement contexts: What do we know? Studies in Continuing Education, 43(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2019.1683533

- Bezu, S., & Holden, S. (2014). Are rural youth in Ethiopia abandoning agriculture? World Development, 64, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity Press.

- Carabelli, G., & Lyon, D. (2016). Young people’s orientations to the future: Navigating the present and imagining the future. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(8), 1110–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1145641

- Carreri, A. (2022). Imagined futures in precarious working conditions: A gender matter?. Current Sociology, 70(5), 742–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921211001

- Christiaensen, L., & Demery, L. (2018). Agriculture in Africa: Telling myths from facts. The World Bank.

- Cole, J. (2011). A cultural dialectics of generational change: The view from contemporary Africa. Review of Research in Education, 35(1), 60–88. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X10391371

- Crivello, G. (2011). ‘Becoming somebody’: Youth transitions through education and migration in Peru. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(4), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.538043

- Damoah, O. B. O., Peprah, A. A., & Brefo, K. O. (2021). Does higher education equip graduate students with the employability skills employers require? The perceptions of employers in Ghana. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(10), 1311–1324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1860204

- Duplantier, A., Ksoll, C., Lehrer, K., & Seitz, W. (May 12, 20222017). The internal migration choices of Ghanaian youths. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/DUPLANTIER%2C%20Anne_paper.pdf

- Evans, C. (2016). Moving away or staying local: The role of locality in young people’s ‘spatial horizons’ and career aspirations. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(4), 501–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1083955

- Filmer, D., & Fox, L. (2014). Youth employment in sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Publications.

- Fox, L. (2019). Economic participation of rural youth: What matters? IFAD Research Series, 46. Papers of the 2019 Rural Development Report.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 population and housing census. District Analytical Report. Talensi District.Online at https://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010_District_Report/Upper%20East/TALENSI.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2022

- Ghana Statistical Service. (Accessed May 12, 2022 2021). Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census. General report volume 3A. Population of regions and districts. On Line at. https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/2021%20PHC%20General%20Report%20Vol%203A_Population%20of%20Regions%20and%20Districts_181121.pdf

- Hardgrove, A., Rootham, E., & Mcdowell, L. (2015). Possible selves in a precarious labour market: Youth, imagined futures, and transitions to work in the UK. Geoforum, 60, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.01.014

- Hilson, G. (2016). Farming, small-scale mining and rural livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa: A critical overview. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(2), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.02.003

- Hilson, G., & Osei, L. (2014). Tackling youth unemployment in sub-Saharan Africa: Is there a role for artisanal and small-scale mining? Futures, 62, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2014.05.004

- Honwana, A., & De Boeck, F. (2005). Makers & breakers: Children and youth in postcolonial Africa. James Currey.

- Kamlongera, P. J. (2011). Making the poor ‘poorer’ or alleviating poverty? Artisanal mining livelihoods in rural Malawi. Journal of International Development, 23(8), 1128–1139. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1836

- Kew, J. (2015). Africa’s young entrepreneurs: Unlocking the potential for a brighter future. IDRC, International Development Research Centre CRDI, Centre de recherches pour le développement international.

- Langevang, T., Gough, K. V., Yankson, P. W. K., Owusu, G., & Osei, R. (2015). Bounded entrepreneurial vitality: The mixed embeddedness of female entrepreneurship. Economic Geography, 91(4), 449–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12092

- Leavy, J., & Hossain, N. (2014) IDS Working Paper 439. Who wants to farm? Youth aspirations, opportunities and rising food prices. Institute of Development Studies (IDS).

- Leavy, J., & Smith, S. (2010) FAC Discussion Paper 013. Future farmers: Youth aspirations, expectations and life choices. Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Locke, C., & te Lintelo, D. (2012). Young Zambians ‘waiting’ for opportunities and ‘working towards’ living well: Lifecourse and aspiration in youth transitions. Journal of International Development, 24(6), 777–794. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2867

- Maconachie, R. (2011). Re‐agrarianising livelihoods in post‐conflict sierra leone? Mineral wealth and rural change in artisanal and small‐scale mining communities. Journal of International Development, 23(8), 1054–1067. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1831

- Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

- Mensah, A. O., Fobih, N., & Adom, Y. A. (2019). Entrepreneurship development and new business start-ups: Challenges and prospects for Ghanaian entrepreneurs. African Research Review, 13(3), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v13i3.3

- Ministry of Finance. (2020). Composite budget for 2020-2023. Programme Based Budget Estimates for 2020. Talensi District. Online at https://mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/composite-budget/2020/UE/Talensi.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2022

- Mueller, V., & Thurlow, J. (2019). Youth and jobs in rural Africa: Beyond stylized facts. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198848059.003.0001

- Mueller, V., Thurlow, J., Rosenbach, G., & Masias, I. (2019).Africa’s rural youth in the global context. In Ed. Youth and jobs in rural africa: beyond stylized facts (pp. 1–22). Valerie Mueller and James Thurlow, Oxford University Press (2019).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2018). OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298521-en.

- Ofosu, G., Dittmann, A., Sarpong, D., & Botchie, D. (2020). Socio-economic and environmental implications of Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) on agriculture and livelihoods. Environmental Science & Policy, 106, 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.02.005

- Osei, L., Yeboah, T., Kumi, E., & Antoh, E. F. (2021). Government’s ban on Artisanal and small-scale mining, youth livelihoods and imagined futures in Ghana. Resources Policy, 71, 102008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102008

- Osumanu, I. K. (2020). Small-scale mining and livelihood dynamics in North-Eastern Ghana: Sustaining rural livelihoods in a changing environment. Progress in Development Studies, 20(3), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993420934223

- Patel, V. (2017). Parents, permission, and possibility: Young women, college, and imagined futures in Gujarat, India. Geoforum, 80, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.01.008

- Stahl, G., Mcdonald, S., & Young, J. (2020). Possible selves in a transforming economy: upwardly mobile working-class masculinities, service work and negotiated aspirations in Australia. Work, employment and society, 351, 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020922336

- Sumberg, J., & Hunt, S. (2019). Are African rural youth innovative? Claims, evidence and implications. Journal of Rural Studies, 69, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.05.004

- Sumberg, J., Yeboah, T., Flynn, J., & Anyidoho, N. A. (2017). Young people’s perspectives on farming in Ghana: A Q study. Food Security, 9(1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-016-0646-y

- Tangonyire, D. F., & Akuriba, G. A. (2020). Socioeconomic factors influencing farmers’ specific adaptive strategies to climate change in Talensi district of the Upper East Region of Ghana. Ecofeminism and Climate Change, 2(2), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1108/EFCC-04-2020-0009

- Tschakert, P. (2009). Recognizing and nurturing artisanal mining as a viable livelihood. Resources Policy, 34(1–2), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2008.05.007

- Verkaart, S., Mausch, K., & Harris, D. (2018). Who are those people we call farmers? Rural Kenyan aspirations and realities. Development in Practice, 28(4), 468–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1446909

- Vigh, H. (2009). Wayward migration: On imagined futures and technological voids. Ethnos, 74(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840902751220

- White, B. (2019). Rural youth, today and tomorrow. IFAD Research Series, 48. Papers of the 2019 Rural Development Report.

- Yeboah, T. (2021). Future aspirations of rural-urban young migrants in Accra, Ghana. Children’s Geographies, 19(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1737643

- Yeboah, T., Crossouard, B., & Flynn, J. 2021. Young people’s imagined futures. In J. Sumberg, Ed. Youth and the rural economy in Africa: Hard work and hazard. CAB International, Oxfordshire. 155–169.

- Yeboah, T., & Flynn, J. (2021). Rural Youth Employment in Africa: An Evidence Review. Evidence Synthesis Paper 10/2021. INCLUDE Knowledge Platform. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/16588

- Yeboah, T., Sumberg, J., Flynn, J., & Anyidoho, N. A. (2017). Perspectives on desirable work: Findings from a Q study with students and parents in rural Ghana. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(2), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-016-0006-y