Abstract

This study aims to analyze the growth trajectory of global scientific output on the “inclusive governance” concept, and governance principles that have received the most attention. The bibliometric review was used in this study on the Scopus database. The data were analyzed using VOSviewer 1.6.16 version and Microsoft Excel. This review found that the term “inclusive governance” was first used in 2000 and has continued to increase significantly since 2013. This review found that the authors of inclusive governance emphasized more on principles: participation, power, accessibility, structure, accountability, empowerment, fairness, collaboration, capacity, and decision-making. This review provides a new and beneficial way to reveal the history of the inception of inclusive governance thinking as a derivative of the grand paradigm of governance, along with the principles that were emphasized by previous authors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

After a long history of ideas development, governance has now become a popular concept in the discourse of public management and public policy due to its ability to connect various ideas, arguments, and other theoretical concepts. This review presents an overview of past, present, and future global scientific output trends on one of the governance variants, namely, inclusive governance. This concept was first used in 2000, and continues to be discussed and developed until now.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of inclusive governance, this review also identifies its principles based on global scientific output on inclusive governance concepts. Based on these principles, this review recommends what public organizations should strive to reach favorable conditions and incentives for equitable distribution of wealth and wider public service delivery.

This review is an initial stage to building up cohesion and a solid theoretical framework of the inclusive governance concept that necessarily can be developed further in future research.

1. Introduction

Governance is as old as human civilization, and this term has been used by Plato to refer to “art of navigation” (or proper steering) of a community (Malapi-Nelson, Citation2017). However, the use of term “governance” in a broader context, as known these days, began in the 1990s, when the idea was introduced by economists and political scientists which was later disseminated by third-sector organizations, such as the United Nations, the IMF, and the World Bank.

As political influence and bureaucratic control over the central and local governments were too strong, they were considered to be the causes of widespread public management issues, such as poverty, corruption, economic stagnation, political instability, and human rights violations (Jreisat, Citation2004). These issues drove global changes in public management trends and resulted in the emergence of new service from the third sector including the encouragement of the spread of governance ideas throughout the world (Asaduzzaman & Virtanen, Citation2016).

After the long history of ideas development, governance has now become a “broad umbrella” that covers various ideas. Asaduzzaman and Virtanen (Citation2016) argued that governance is increasingly popular in the discourse of public management and public policy due to its ability to connect various arguments and other theoretical concepts. Despite its increasing popularity among researchers and public policy practitioners for the last three decades, governance remains to be considered as a dynamic concept, controversial, and far from being a “finished product” (Farazmand, Citation2012).

In line with global managerial trends, alternative decentralized and inclusive forms of governance in which citizens are encouraged to take on greater management responsibilities have recently been suggested (Vernon et al., Citation2005). In the study of participation, Goodwin (Citation1998) highlighted the notion of inclusion and empowerment as the antithesis of practice and tradition of simplification of participation which , generally, only involves key parties. With the emergence of the 2030 Agenda, the efforts to promote a more inclusive governance process are increasingly being understood as a top priority in international development (OECD, Citation2020).

This review intends to enrich the concept of governance by showing the theoretical complexities on inclusive governance and its relationship with other well-established concepts and ideas. Up to now, discussions on inclusive governance are limited to specific analyzes that discuss single topics and cases. Therefore, the interpretation of inclusive governance concept often differs. As a result, it is difficult to identify the consistency of the use of governance principles in the discussion of inclusive governance. The inclusive governance literature also lacks cohesion, depth, and a strong theoretical framework.

The depiction of interrelationship between concepts can help scientists understand the history of the development of inclusive governance since its inception and can provide guidance in further research. This review will address three specific goals:

to find out the general information and growth trajectory of global scientific output on inclusive governance concept;

to discover the topic variations and evolution of inclusive governance studies; and

to identify the consistency of the use of governance principles in the studies of inclusive governance.

2. Method

In this bibliometric review, we searched for documents related to inclusive governance indexed in Scopus database. Scopus is the largest database and has better journal coverage than PubMed or Web of Science, and is recognized as a trusted source for academic and bibliometric studies (Falagas et al., Citation2008). Scopus has been used and validated in bibliometric review on governance concepts that have previously been published (Naomi et al., Citation2020; Widianingsih et al., Citation2021). The search strategy for documents was limited to: English language publications, and publications with subject areas: Social Sciences, Economics, Econometrics and Finance, and Arts and Humanities. The results of searching data on each restriction can be seen in .

Table 1. Retrieval process of Scopus database

Data downloading was carried out on 31 July 2021. The following search string was used to identify publications by searching for the keyword “inclusive governance” based on title, abstract, and keywords. We did not limit the year of document issuance in order to find out when inclusive governance was used for the first time, and to examine the growth of inclusive governance discussions since it first appeared.

This study used a bibliometric review method that was conducted on 162 documents. The data was analyzed using VOSviewer 1.6.16 version to identify the most influential documents in the discussion on inclusive governance, and concepts in social science discussed related with inclusive governance. Frequency calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel to analyze the growth and geographic distribution of documents discussing inclusive governance from its inception to the present.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of inclusive governance and principles that have received the most attention from 162 articles, we conducted a manual review by reading all documents and calculating the frequency using a meta-analysis. Of all documents that have been read, there are only 117 documents that contain governance principles. In 117 analyzed documents, inclusive governance was interpreted with various principles, therefore each document was coded to mark the various principles contained therein. If a principle was discussed in one document, then this principle had a frequency of 1. The principles are then listed in the order of occurrence/frequency starting from the highest (see Table ).

Table 2. Top 10 most affiliated countries publishing “inclusive governance” documents

Table 3. Top 10 most cited “inclusive governance” documents

Table 4. Governance principles that have received the most attention

3. Result and discussion

3.1. General information and growth trajectory of global scientific output on inclusive governance

Inclusiveness questions if “potential stakeholders” participate in influencing policy systems through active citizenship that develops literacy and processes, which will deepen democracy (Ison & Wallis, Citation2017). In other words, inclusiveness creates a way to activate the rights and responsibilities of various parties in the governance process.

Creating inclusiveness in a complex governance process certainly requires a careful study of the dynamics formed due to the interrelationships between parties with varying interests and values held. Governance shapes and has a profound impact on the country and it works along three core dimensions, which are capacity, authority, and legitimacy (Call, Citation2011). Governance practices also influence the nature and quality of their relationships with society. Thus, a complex network and interaction of interested parties will emerge.

Based on the explanation above, a common thread can be drawn that governance makes the government no longer the only party. The innovation and managerial style of the government should involve more non-government parties (Frederickson, Citation2004; Hill, Citation2004; Ison & Wallis, Citation2017); therefore, the interaction between the government bureaucracy and citizens will be better. These basic things confirm that inclusiveness has, as a matter of fact, become an intrinsic value of the concept of governance.

Inclusive governance as a concept assessed by the OECD (Citation2020) has a theoretical complexity that is connected with ideas, including but not limited to good governance, democratic governance, and human-right-based approach, legitimacy, and social cohesion. Then, Hickey (Citation2015) connects inclusive governance with normative sensitivity that supports inclusion as a measure by which institutions can be judged as good or bad.

Inclusive governance will ask: who is involved in the decision-making process, how they are involved, and why they are involved?; which groups have more and less influence and why?; and how do these dynamics and interactions shape the nature of decisions, the quality of decisions, and how they are implemented? (OECD, Citation2020). In other words, inclusive governance is intended to promote a political system in which all citizens are equal and their voices are accounted for equally, which will create favorable conditions and incentives for equitable distribution of wealth and wider public service delivery.

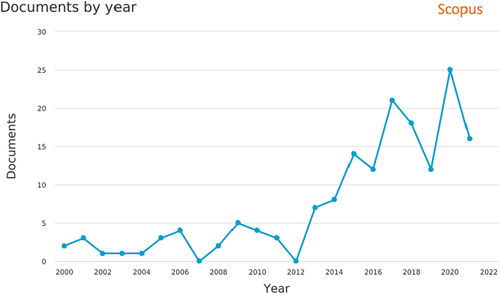

This bibliometric review began with focusing on the total and growth of documents issued per year from its inception (see ). The Scopus database found 162 English-language documents with the keyword “inclusive governance” from 2000 to 2021. These data showed that inclusive governance was first written in 2000 (Douglass, Citation2000; Geddes, Citation2000). After that, the number of publications grew slowly every year, with slight fluctuations, and significantly increased since 2013. There were 116 articles, 27 book chapters, 9 reviews, 3 books, 3 conference papers, 3 notes, and 1 editorial.

The top 10 countries published 133 documents (82.1%) of all publications. The United Kingdom was in first place (23.5%); followed by the United States (14.8%); Australia, India, and the Netherlands (8.0% each); Italy and South Africa (4.3% each); Canada, Denmark, and Germany (3.7% each) (the details about number of citation and link stregth can be seen on ). This indicates that the United Kingdom is at the forefront of scientific research on inclusive governance.

Analysis of the most cited publications yielded the top 10 publications (Table ) The number of citations in this document can indicate the significance of the publication’s influence. The top 10 most cited titles and their keywords can guide social scientists to identify what topics are currently trending, the landscape that is constantly changing, and significant future research directions.

3.2. Topic variations and evolution of inclusive governance studies

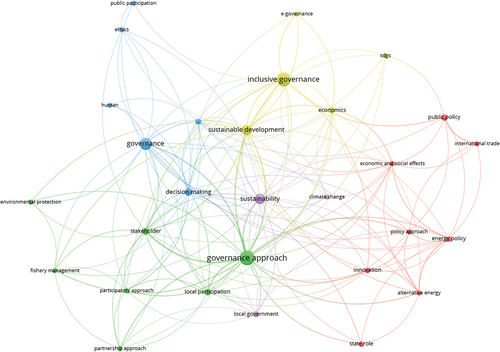

Network visualization is shown in Figure , there were 1446 different terms found from the published publications; however, only 29 of them appeared more than 5 times. Five clusters or thematic research areas can be considered, consisting of terms that appear together which is categorized by five different colors, as follows:

Cluster 1 (in red): mainly includes terms related to the topic of energy policies such as alternative energy, economic and social effects, energy policy, innovation, international trade, policy approach, public policy, and state role.

Cluster 2 (in green): mainly includes terms related to the topic of partnership and participation, such as environmental protection, fishery management, governance approach, local participation, participatory approach, partnership approach, and stakeholder.

Cluster 3 (in blue): mainly includes terms related to the topic of decision-making such as decision-making, empowerment, ethics, governance, humanism, and public participation.

Cluster 4 (in yellow): mainly includes terms related to the topic of sustainable developments such as e-governance, economics, SDGs, and sustainable development.

Cluster 5 (in purple): discusses about climate change, local government, and sustainability.

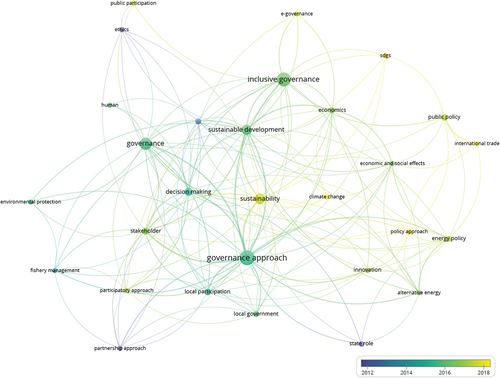

In the overlay visualization (Figure ), four color groups can be observed to determine the trend of research topics, as follows:

Purple are topics widely discussed before 2012, such as: ethics, partnership approach, and state role.

Blue are topics widely discussed between 2012 and 2014, such as: empowerment and fishery management.

Green are topics widely discussed between 2014 and 2018, such as: humanism, economics, sustainable development, governance, environmental protection, decision-making, economic and social effect, governance approach, local participation, local government, alternative energy, innovation, participatory approach, public policy, energy policy, and stakeholder.

Yellow are topics widely discussed since 2018 until now, such as: public participation, e-governance, SGDs, international trade, policy approach, climate change, and sustainability.

3.3. The use of governance principles in the studies of inclusive governance

Ruhanen et al. (Citation2010) have discussed the principles of governance in a broad scope, topics, and cases. Therefore, 40 governance principles found by Ruhanen et al. (Citation2010), were used as a basic reference in conducting a review of 162 documents that have been reduced to 117 documents containing governance principles.

Findings of this review were that of the 40 governance principles established, the 13 principles that were most often discussed in the discussion of inclusive governance were: participation, power, structure, accountability, fairness, capacity, decision-making, transparency, effectiveness, legitimacy, civil peace, conflict resolution, and training. Each of these principles was identified in at least five documents.

There were 20 identified principles discussed in less than five documents, including decentralization, knowledge management, leadership, rule of law, flexibility, performance, trust, ownership, communication, responsiveness, auditing, commitment, compliance, risk management, efficiency, consensus, culture, design, informal connections, and innovation. In addition, there were seven principles that were not discussed at all, including shareholder rights, authority, interdependence, strategic vision, direction, exchange, and market.

We also found four principles that were different from the principles discussed by Ruhanen et al. (Citation2010). These principles were considered to be quite strong as they were discussed in 5 to 14 documents. The four principles were accessibility, empowerment, collaboration, and voice.

After combining all of the principles found in this review, the 10 principles most reviewed by authors on inclusive governance, in order from the highest, were participation, power, accessibility, structure, accountability, empowerment, fairness, collaboration, capacity, and decision-making.

This differs from the findings of Ruhanen et al. (Citation2010) which ranked 10 principles of governance from the highest were accountability, transparency, involvement/participation, structure, effectiveness, power, efficiency, decentralization, shareholder rights, and knowledge management. The difference is understandable because Ruhanen et al. (Citation2010) highlighted the concept of governance as a major paradigm from the perspectives of political sciences and corporate management fields. Meanwhile, this study highlighted inclusive governance as a concept derived from the governance paradigm, and was limited to the subject area of social science.

Each of the 10 strongest principles in the discussion of inclusive governance will be discussed in the following explanation in order to identify the researchers’ intentions in reviewing each principle and examine the relationship between those principles and the concept of inclusiveness.

3.4. Participation

Public engagement is often understood as an important element in implementing deliberative democracy and a tool to form good and friendly policies, and fostering innovation in the government (Andanda, Citation2019). Community participation is also a major factor in creating inclusive development (Armstrong, Citation2006; Hendriks (Citation2010a); Kumar, Citation2010).

Muchadenyika (Citation2015) provided an example of the success of the Harare city due to the proactive role played by the poor through a strong alliance and cooperation. Thompson et al. (Citation2014) and Balassiano and Maldonado (Citation2014) suggested that civil society to form an effective and massive movement through an organization. The organization also serves as an intermediary for governance between civil society and the government.

Armstrong (Citation2006), Kumar (Citation2010) and Hendriks (Citation2010) emphasize participation in an international space in which the global community is valued as an ecosystem of equal social participation. Global civil society has emerged as a space for supranational social and political participation to respond to contemporary issues, as well as a space for the majority of people who in the past did not have the opportunity to be heard (Hendriks, Citation2010a; Citation2010).

3.5. Accessibility

Jones (Citation2005) reviewed access in a perspective also discussed by the OECD (Citation2020), called as “human right-based approach”. Jones (Citation2005) intended to explore how human rights principles applied in the context of social mobilization and community-driven access to institutional channels, which in turn have the potential to impact policy making. A right-based approach expands the inclusive political space not only in policy-making, but can also have an impact on providing services (Jones, Citation2005; Singh et al., Citation2009)

Huffman (Citation2017) and Guimarães et al. (Citation2016) complemented the access approach by prioritizing capacity in order that the access obtained by the community will become more valuable. In addition, community agencies in the form of mobilization and grassroots organizations that act as governance intermediaries between civil society and the government are necessary in order that the community can access and influence both of self-created (invented) and more formal (invited) spaces of governance and government (L. Thompson et al., Citation2014).

3.6. Power

The main point of achieving inclusiveness in this principle is the sharing of power in various contexts. Mbah et al. (Citation2017) and Roessler and Ohls (Citation2018) discussed power sharing at the central government level. The struggle between political elites over control of state power has intensified national conflicts and escalating rebellions. Conflict over “who gets what” leads to the formation of a sect and fuels unrelenting attacks and insecurity (Mbah et al., Citation2017). Power sharing, in which elites from competing societal groups agree to share control of government, is the primary source of peace, enabling countries to escape the cycle of exclusion and civil war (Roessler & Ohls, Citation2018). This might happen when rival groups also have strong mobilization capabilities. Therefore, the distribution of power will occur even if it is forced.

Many researchers emphasized the principle of power in the context of the relationship between central and local government (V. L. S. Brisbois & de Loë, Citation2016; Kefale, Citation2014; Mustalahti & Agrawal, Citation2020; Thompson & Hood, Citation2016). The development of relations between government and society can be hampered by imbalances in power (V. L. S. Thompson & Hood, Citation2016). Governments have the potential to leverage power and reproduce existing power structures to support or challenge potential collaboration (Brisbois & de Loë, Citation2016).

In the context of government level relations, decentralization is one of the main strategies. Decentralization must be accompanied by a policy that will ensure the sharing of power at lower levels, the delegation of sufficient resources, and decision-making authority at the local level to support the mandates they have received (Kefale, Citation2014; Mustalahti & Agrawal, Citation2020).

Steenbergen (Citation2016) discussed power relations in the context of the lowest local government in Indonesia, that is the village government. His findings stated that legitimacy of the leadership of indigenous social groups has a dominant strength. Indigenous leaders have strong power in managing village government. Therefore, there was an injustice in the distribution of program utilization. Villagers outside the traditional group are part of the minority and marginalized in the village administration, in spite of the fact that they are important stakeholders (Steenbergen, Citation2016).

3.7. Structure

The importance of developing inclusive governance structures is a major concern of researchers (Lever, Citation2005; Muchadenyika, Citation2015; Söderbaum & Taylor, Citation2001). Barriers to achieving inclusive governance structures include imbalances in power and knowledge of the elites and the experts that often exist among practitioners, researchers, and community members (B. Hendriks, Citation2010; V. L. S. Thompson & Hood, Citation2016). In order to overcome the dominance of knowledge by elites, it is necessary to link governance structures with direct forms of citizen engagement (Hendriks, Citation2010), with institutional commitment from universities to flexible and inclusive governance structures and strategies to educate the public, and with adequate regulation and great law enforcement (Eriksson et al., Citation2015).

Hayward (Citation2011) warned that the formation of the state structure is strongly influenced by conflicts of interest between groups. Religion as a community group, according to Hayward (Citation2011), has significance in the evolution of the state structure. This group has the power to define “national issues” as part of a religious struggle. This is also supported by Flinders and Wood (Citation2019) and Eriksson et al. (Citation2015) who emphasized the underlying politics of “who defines” policies. Therefore, culture, religion, and its parties, along with their interests, subjective views, and dynamics among them are considered to be the “politics that underlie” the formation and evolution of the state structure.

3.8. Empowerment

Empowerment is a systematic process to make individuals and communities independent in voicing their concerns, recognizing their needs, and optimizing the use of internal potential to fulfill their needs and solve their problems (Balassiano & Maldonado, Citation2014; Van der Grijp et al., Citation2019). Empowerment also means making citizens to become agents of change for themselves and their communities (Gilman, Citation2016).

Discussions on empowerment cannot be separated from strengthening community participation and capacity in identifying needs, working with elected officials to prepare budget proposals, choosing how to spend public funds, and capacity to manage sustainable development (Gilman, Citation2016; Katre et al., Citation2019). Speaking of capacity, Katre et al. (Citation2019) argued that the empowerment strategy can be carried out through increasing institutional, financial, and technical capacity, which is resulted from community involvement from the early stages of development program, therefore a strong sense of ownership emerges.

3.9. Accountability

According to Ahmed (Citation2017), accountability can be seen from two opposing sides, moral accountability, and political accountability. Adherents of moral accountability stated that accountable behaviors in organization employees can be improved with good work rules and effective morals (Ahmed, Citation2017; Othman & Rahman, Citation2011). Therefore, inclusive governance must accommodate metrics and indicators that reflect processes such as how officials are accountable to the public, the extent to which public information is available and accurate, and the creation of a timely accountability channel (Gilman, Citation2016).

Adherents of political accountability revealed that political control is required to demand responsibility from those in power. The absence of political control will create a self-interested bureaucracy. In turn, the bureaucracy will become a medium for gathering power and knowledge that is only held by technocrats (Ahmed, Citation2017). The new order of government must be based on socially embedded forms of accountability and reliability, not technocratic (Delgado & Strand, Citation2010). Thus, social accountability requires strengthening the community’s capacity in the process of participation and policy advocacy.

3.10. Fairness

Access to resources, public goods, and public services are part of human rights (Singh et al., Citation2009; Misra, Citation2017; N Ahmed, Citation2017). Therefore, justice is the basic foundation in every development process (Siakwah et al., Citation2020). Access to public services in a fair manner can be obtained through social accountability mechanisms in which civil society and their organizations are enabled to participate in demanding accountability (Rahman, Citation2017). Inclusion in the social accountability implies that marginalized groups can overcome injustice in their “voice relationship” with the government and public institutions responsible for providing services.

Hoque (Citation2017) examines the issue of inclusiveness in a judiciary context that is more complex than legislative and executive. Fairness in this case requires a justice system that is not only internally diverse or representative but also functionally inclusive, protecting minorities, the poor, the marginalized, and the excluded in society (Hoque, Citation2017; Koepke & Robinson, Citation2018). It means wider public access to the justice system. Inclusive justice also refers to the idea that the judiciary must be able and willing to enforce the rules to ensure inclusiveness in the legislative and executive.

3.11. Collaborative

In addition to collaborations with non-profit organizations, Francis et al. (Citation2020) emphasized the importance of collaboration with universities. Practical intervention through the collaboration of governments, international parties, universities, local community organizations, communities, and private sector will enable the resolution of complex issues, such as poverty, environmental degradation, and economic and social exclusion (Francis et al., Citation2020; Siakwah et al., Citation2020). In order to make this collaboration happen, the government will play an important role in the initiation. Government power instruments ranging from agenda setting to implementation are strong factors both in supporting and challenging the potential for collaboration (Brisbois & de Loë, Citation2016).

Inclusive governance also requires the involvement of various groups in the internal institutional environment (Ahmed, Citation2017; A M; Shahan & Khair, Citation2017). The problems about specialist employees versus generalist employees raise competition between them (Shahan & Khair, Citation2017). By focusing on multi-sectoral collaboration in formulating policies and implementing program, opportunities to combine perspectives between specialists and generalists will be opened.

3.12. Capacity

Sustainable development can only be implemented practically if there is serious attention to institutional capacity building (George et al., Citation2015; Mc Lennan & Ngoma, Citation2004). Therefore, the government is required to facilitate various public institutions (both government and civil society) to strengthen their institutional capacity. With the strong institutional capacity of these various public organizations, inclusiveness in sustainable development will be promoted and pursued by many stakeholders.

Ziervogel (Citation2019) found that in order to create more inclusive governance, transformative capacity is needed. This capacity can be obtained when there is interaction between local government and the poor to: acknowledge the everyday realities and work with them to identify priorities for transformative change, support sustainable intermediaries, create an enabling environment for innovation, and involve a variety of parties to experiment with planning and development practices.

Grindle and Hilderbrand (Citation1995) argue that increasing the capacity of government institutions depends on five dimensions, namely, the action environment, the institutional context of the public sector, task networks, organization, and human resources. The action environment refers to the social stability, political condition, and economic soundness facilitating the ability of the government to perform its functions. The public sector institutional context refers to the formal influences (e.g., rules and procedures that govern the public organization), and informal influences (e.g., power relationship) that affect public institution function. The task network related to the ability of organization to bring together other organizations to deliver particular functions or specific public services. The organizational dimension refers to the structures, processes and resources of the organization, and management styles adopted by members of the organization. Human resources dimension relates to the ability of organization to recruit, utilize, train, and retain capable employees.

3.13. Decision making

Inclusive governance includes a strong passion for bottom-up decision-making, involving all stakeholders at every governance level (Liyanage, Citation2017). Equal rights are needed for all, including women, the poor, and ethnic minorities in influencing decision-making that affects them (Liyanage, Citation2017). The argument for equal rights in decision-making is to ensure that decision makers can protect, share interests, represent and enrich the experiences of marginalized communities.

Decision-making that seeks to increase the intensity of communication between citizens and decision makers is considered to increase participation, and hence the democratic deficit will also be avoided (Antal & Mikecz, Citation2013; Balassiano & Maldonado, Citation2014; Misra, Citation2017). In order to make reliable decisions, it is necessary to analyze the context of the community’s choice of media for discussion. Balassiano and Maldonado (Citation2014) advised decision makers to know the places used for community discussion, by whom they are used, and why they can inform and help develop participatory practices. He stated that the more effective and inclusive choice of place, the more effective community integration will be.

After discussing the 10 principles of inclusive governance, the question arose, how can all of these principles be achieved and where should reform be started from? To answer the question, policymakers need to think strategically. Strategic thinking generally starts with defining clear goals, followed by assessing the obstacles, and looking for alternative paths or prioritization of actions that enable the achievement of goals and overcoming obstacles. Levy and Fukuyama (Citation2010) suggest a comprehensive framework for thinking strategically about integrating more inclusive governance and development. They elaborate on four sequences and provide specific illustrations based on different country contexts. The four sequence models are briefly described as follows:

First sequence, state capacity building. For a low-income country that is not showing growth over the long term, it will be easy for experts and ordinary people to identify the causes related to the government does not work, and political leaders being incompetent and/or corrupt. Hence, private investors face risks of failure, burdensome bureaucracy, political pressure to share profits, violence, and instability. In this condition, reform can be started with state capacity building. Improving the performance of the public sector will become the basis for accelerating growth and increasing the government’s credibility in front of investors. Furthermore, strengthening political institutions and civil society is a long-term agenda;

Second sequence, transformational governance: political institutions transformation as entry point. Levy and Fukuyama (Citation2010) stated a positive correlation between the quality of state institutions and income per capita. A country with a high per capita income is accompanied by a well-functioning rule of law, democratic institutions, and a public bureaucracy. These institutions reinforce each other through checks and balances provided by democracy and the rule of law. Democracy and the rule of law provide corrective mechanisms that keep governments from straying too far, even in the face of possibly dysfunctional political leadership. Transformational governance as an entry point will shape a country’s political institutions towards accountable conditions and reduce arbitrary discretionary actions, thereby shifting expectations in a positive direction. Eventually accelerated growth will follow.

Third sequence, just enough governance: growth as an entry point. Recent empirical research has shown that long-term reforms—neither institutional nor economic—are not required to initiate growth. Policy reforms and institutional arrangements, often interact with the external environment, and thereby produce discontinuous changes in economic performance. Once growth is set in motion, it will be easier to sustain a virtuous cycle. High growth and institutional transformation are mutually reinforcing (Hausmann et al., Citation2004). Thus, the first step in this approach is the initiation of growth itself.

Fourth sequence, bottom-up development: civil society as the entry point. In the case of a country where almost all channels – except civil society – are blocked; no economic growth; weak state capacity and corrupt government; democracy and the rule of law do not exist because political power is in the hands of actors who have no desire to change the status quo, the main driving factor of development will be the mobilization of civil society, which will increase demands for greater democracy and the rule of law, and a state that can provide public services.

4. Conclusion

Based on the analysis, it is concluded that: First, the inclusive governance concept was first used in 2000, and the number of its publications significantly increase since 2013. The United Kingdom is at the forefront contributor of scientific research on inclusive governance followed by the United States, the Netherlands, Australia, India, Italy, South Africa, Denmark, Germany, and Canada. Miraftab, Larner & Craig, Douglass, Geddes, Gleeson & Kearns, Andres & Chapain, Bracking, Simonsen, Njock & Westlund, and Wright et al. are regarded as the authors who published the most influential documents. Second, network visualization shows the inclusive governance topic variations categorized by five clusters, namely, energy policy, partnership and participation, decision-making, sustainable development, and climate change. Overlay visualization shows the evolution of inclusive governance studies. Ethics, partnership, and state role are the topics discussed before 2012. Empowerment and fishery management were widely discussed between 2012 and 2014. Between 2014 and 2018 the topic grew and expanded covering: humanism, economics, sustainable development, governance, environmental protection, decision-making, economic and social effect, governance approach, local participation, local government, alternative energy, innovation, participatory approach, public policy, energy policy, and stakeholder. The trend from 2018 to today leads to topics regarding public participation, e-governance, SGDs, international trade, policy approach, climate change, and sustainability. Third, the top 10 governance principles consistently most used by the scholars who wrote on inclusive governance were participation, power, accessibility, structure, accountability, empowerment, fairness, collaboration, capacity, and decision-making.

To reach favorable conditions and incentives for equitable distribution of wealth and wider public service delivery, public organizations should mainstream: (1) participation of the minorities, the poor, and the marginalized; (2) broadening access to policy-making and public service delivery; (3) distribution of power and knowledge in various contexts and levels of government; (4) enhancing the interrelationships between governance structures, knowledge, and direct forms of citizen engagement; (5) enhancing the ability of citizens to voicing their concerns, recognize their needs, solve their problems, and optimize potential to fulfill their needs; (6) strive for accountability through adherence to good work rules and effective morals of public officials, at the same time there are effective participation, political control, and policy advocacy from citizens; (7) ensure the executive, legislative and judicial functions run fairly to protect the minorities, the poor, and the marginalized; (8) building up collaboration between public organizations to various parties outside and solving collaboration problems between parties inside; (9) facilitate various public institutions (both government and civil society) to strengthen their institutional capacity; and (10) bottom-up decision-making and involve all stakeholders at every governance level.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nasrun Annahar

Nasrun Annahar is a doctoral student in the Administrative Sciences Programme, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia; Special Staff to the Minister of Villages, Development of Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration of Republic of Indonesia; & an awardee of doctoral scholarship from The Indonesia Endowment Funds for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance of Republic of Indonesia.

Ida Widianingsih

Ida Widianingsih is a Professor at Public Administration Department and Vice Dean for Learning, Student, and Research Affairs of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. Her research interests relate to public administration and development issues, inclusive development policy, and participatory governance.

Caroline Paskarina

Caroline Paskarina is an Associate Professor in the Political Sciences Department, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran. Her area of research is citizenship, digital activism, political discourse, and populism

Entang Adhy Muhtar

Entang Adhy Muhtar is an associate professor at the Public Administration Department, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia. His current researches in the area of rural development issues.

References

- Ahmed, N. (2017). Introduction. In Ahmed, N (Ed.), Inclusive governance in south Asia: Parliament, judiciary and civil service (pp. 1–23). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60904-1

- Andanda, P. (2019). Public engagement as a potential responsible research and innovation tool for ensuring inclusive governance of biotechnology innovation in low- and middle-income countries. In Schomberg, R. V.,& Hankins, J. (Eds.), International handbook on responsible innovation: A global resource (pp. 503–520). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784718862.00044

- Andreasson, S. (2006). The african national congress and its critics: “Predatory liberalism”, black empowerment and intra-alliance tensions in post-apartheid South Africa. Democratization, 13(2), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340500524018

- Andres, L., & Chapain, C. (2013). The integration of cultural and creative industries into local and regional development strategies in birmingham and marseille: Towards an inclusive and collaborative governance? Regional Studies, 47(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.644531

- Antal, M., & Mikecz, D. (2013). Answer or publish - An online tool to bring down the barriers to participation in modern democracies. International Journal of Public Policy, 9(1/2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPP.2013.053442

- Armstrong, K. A. (2006). Inclusive governance? Civil society and the open method of co-ordination. In Smismans, S. (Ed.), Civil society and legitimate european governance (pp. 42–67). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-51249122330&partnerID=40&md5=2c5c90fa7015c6a2b6da618e543ad189

- Asaduzzaman, M., & Virtanen, P. (2016). Governance theories and models. In Farazmand, A. (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance (pp. 1–13). New York, USA: Springer.

- Asatryan, Z., & De Witte, K. (2015). Direct democracy and local government efficiency. European Journal of Political Economy, 39, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.04.005

- Balassiano, K., & Maldonado, M. M. (2014). Civic spaces in rural new gateway communities. Community Development Journal, 49(2), 262–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bst029

- Belussi, F., & Trippl, M. (2018). Industrial districts/clusters and smart specialisation policies. In Belussi, F., & Hervas-Oliver, J. (Eds.) Advances in spatial science (pp. 283–308). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90575-4_16

- Beyleveld, D., & Jianjun, L. (2017). Inclusive governance over agricultural biotechnology: Risk assessment and public participation. Law, Innovation and Technology, 9(2), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/17579961.2017.1377908

- Bracking, S. (2003). Sending money home: Are remittances always beneficial to those who stay behind? Journal of International Development, 15(5), 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1021

- Brain, M. J., Nahuelhual, L., Gelcich, S., & Bozzeda, F. (2020). Marine conservation may not deliver ecosystem services and benefits to all: Insights from chilean Patagonia. Ecosystem Services, 45. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2212041620301121

- Brisbois, M. C., & de Loë, R. C. (2016). State roles and motivations in collaborative approaches to water governance: A power theory-based analysis. Geoforum, 74, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.06.012

- Buendia, R. G. (2021). Examining Philippine political development over three decades after ‘democratic’ rule: Is change yet to come? Asian Journal of Political Science, 29(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2021.1916970

- Bünte, M. (2018). Building governance from scratch: myanmar and the extractive industry transparency initiative. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48(2), 230–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1416153

- Call, C. T. (2011). Beyond the ‘failed state’: Toward conceptual alternatives. European Journal of International Relations, 17(2), 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066109353137

- Carpenter, J. (2013). Sustainable urban regeneration within the European Union: a case of ‘Europeanization’? In Leary, M. E., & McCarthy, J. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration (pp. 138–147). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108581-24

- Chaney, P. (2002). Social capital and the participation of marginalized groups in government: A study of the statutory partnership between the third sector and devolved government in wales. Public Policy and Administration, 17(4), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/095207670201700403

- Chaney, P., & Fevre, R. (2001). Inclusive governance and “minority” groups: The role of the third sector in wales. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 12(2), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011286602556

- Ciplet, D., & Harrison, J. L. (2020). Transition tensions: Mapping conflicts in movements for a just and sustainable transition. Environmental Politics, 29(3), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1595883

- Colenbrander, A., Argyrou, A., Lambooy, T., & Blomme, R. J. (2017). Inclusive governance in social enterprises in the netherlands - a case study. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 88(4), 543–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12176

- Crosweller, M., & Tschakert, P. (2021). Disaster management and the need for a reinstated social contract of shared responsibility. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 63, 102440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102440

- Delgado, A., & Strand, R. (2010). Looking North and South: Ideals and realities of inclusive environmental governance. Geoforum, 41(1), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.09.008

- Deželan, T. (2018). Derailing modern democracies: The case of youth absence from an intergenerational perspective. Annales-Anali Za Istrske in Mediteranske Studije - Series Historia Et Sociologia, 28(4), 811–826. https://doi.org/10.19233/ASHS.2018.49

- Douglass, M. (2000). Mega-urban regions and world city formation: Globalisation, the economic crisis and urban policy issues in Pacific Asia. Urban Studies, 37(12), 2315–2335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020002823

- Eriksson, H., Conand, C., Lovatelli, A., Muthiga, N. A., & Purcell, S. W. (2015). Governance structures and sustainability in Indian Ocean sea cucumber fisheries. Marine Policy, 56, 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.02.005

- Falagas, M. E., Pitsouni, E. I., Malietzis, G. A., & Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, scopus, web of science, and google scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. The FASEB Journal, 22(2), 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF

- Farazmand, A. (2012). Sound governance: Engaging citizens through collaborative organizations. Public Organization Review, 12(3), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-012-0186-7

- Flinders, M., & Wood, M. (2019). Ethnographic insights into competing forms of co-production: A case study of the politics of street trees in a northern english city. Social Policy and Administration, 53(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12484

- Francis, J., Henriksson, K., & Stewart Alonso, J. (2020). Collaborating for transformation: Applying the Co-Laboratorio approach to bridge research, pedagogy and practice. Canadian Journal of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2020.1797650

- Frederickson, H. G. (2004). Whatever happened to public administration? Governance, governance everywhere. In Working Paper QU/GOV/3/2004. Citeseer.

- García, M., Eizaguirre, S., & Pradel, M. (2015). Social innovation and creativity in cities: A socially inclusive governance approach in two peripheral spaces of Barcelona. City, Culture and Society, 6(4), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2015.07.001

- Geddes, M. (2000). Tackling social exclusion in the European Union? The limits to the new orthodoxy of local partnership. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(4), 782–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00278

- George, J., Ottignon, E., & Goldstein, W. (2015). Managing expectations for sustainability in a changing context – In Sydney’s –inner west – A GreenWay governance case study. Australian Planner, 52(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2015.1034736

- Gilman, H. R. (2016). Democracy reinvented: Participatory budgeting and civic innovation in America. In Gilman, H. R. (Ed.), Democracy reinvented: Participatory budgeting and civic innovation in America (pp. 16–427). Brookings Institution Press. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84994188643&partnerID=40&md5=434e643099aef54e607ced0b06758d64

- Gleeson, B., & Kearns, R. (2001). Remoralising landscapes of care. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 19(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1068/d38j

- Gooden, J., & T Sas-Rolfes, M. (2020). A Review of Critical Perspectives on Private Land Conservation in Academic Literature. Ambio, 49(5), 1019–1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01258-y

- Goodwin, M. (1998). The governance of rural areas: Some emerging research issues and agendas. Journal of Rural Studies, 14(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(97)

- Grindle, M. S., & Hilderbrand, M. E. (1995). Building sustainable capacity in the public sector: What can be done? Public Administration and Development, 15(5), 441–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230150502

- Grosser, K. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and multi-stakeholder governance: Pluralism, feminist perspectives and women’s NGOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2526-8

- Guimarães, E. F., Malheiros, T. F., & Marques, R. C. (2016). Inclusive governance: New concept of water supply and sanitation services in social vulnerability areas. Utilities Policy, 43, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2016.06.003

- Gutberlet, J. (2009). Solidarity economy and recycling co-ops in São Paulo: Micro-credit to alleviate poverty. Development in Practice, 19(6), 737–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520903026892

- Gutberlet, J. (2021). Grassroots waste picker organizations addressing the UN sustainable development goals. World Development, 138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105195

- Hambleton, R. (2015). Practice papers place-based leadership: A new perspective on urban regeneration. Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, 9(1), 10–24. https://www.henrystewartpublications.com/jurr/v9

- Hasan, Z. (2006). Bridging a growing divide? The Indian national congress and Indian democracy. Contemporary South Asia, 15(4), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584930701330063

- Hausmann, R., Pritchett, L., & Rodrik, D. (2004). Growth Accelerations. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 10566. https://doi.org/10.3386/w10566

- Hayward, S. (2011). The spoiler and the reconciler: Buddhism and the peace process in Sri Lanka. In Sisk, T. D. (Ed.), Between terror and tolerance: Religious leaders, conflict, and peacemaking (pp. 183–199). Georgetown University Press. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84903045372&partnerID=40&md5=be8d85e49d4b7bf74f9170867f6a37f5

- Heap, S. P. H., Tsutsui, K., & Zizzo, D. J. (2020). Vote and voice: An experiment on the effects of inclusive governance rules. Social Choice and Welfare, 54(1), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-019-01214-5

- Hendriks, B. (2010). Urban livelihoods, institutions and inclusive governance in Nairobi:’spaces’ and their impacts on quality of life, influence and political rights. Amsterdam University Press.

- Hendriks, C. M. (2010). Inclusive governance for sustainability. In Brown, V. A, Harris, J. A., & Russell, J. (Eds.), Tackling wicked problems: Through the transdisciplinary imagination (pp. 150–160). Earthscan. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849776530

- Hickey, S. (2015). Inclusive Institutions. University of Birmingham.

- Hill, C. J. (2004). Governance, governance everywhere. In J. D. Donahue, J. S. Nye. (Eds.), Market-Based Governance: Supply Side, Demand Side, Upside, and Downside. Brookings Institution Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muh007

- Hinrichs, M. M., & Johnston, E. W. (2020). The creation of inclusive governance infrastructures through participatory agenda-setting. European Journal of Futures Research, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309-020-00169-6

- Hoque, R. (2017). The inclusivity role of the judiciary in Bangladesh. In Ahmed, N. (Ed.), Inclusive governance in south Asia: Parliament, judiciary and civil service (pp. 99–122). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60904-1_6

- Houston, D., Varna, G., & Docherty, I. (2021). The political economy of and practical policies for inclusive growth—a case study of Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(1), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa039

- Huffman, B. D. (2017). E-participation in the Philippines: A capabilities approach to socially inclusive governance. JeDEM - eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government, 9(2), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.29379/jedem.v9i2.461

- Ison, R., & Wallis, P. (2017). Mechanisms for inclusive governance. E. Karar(Ed.), Freshwater governance for the 21st century. (Vol. Vol. 6, pp. 159–185). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43350-9_9

- Ituarte-Lima, C., Dupraz-Ardiot, A., & McDermott, C. L. (2019). Incorporating international biodiversity law principles and rights perspective into the European Union timber regulation. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19(3), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09439-6

- Jones, P. S. (2005). “A Test of Governance”: Rights-based struggles and the politics of HIV/AIDS policy in South Africa. Political Geography, 24(4), 419–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.10.012

- Jreisat, J. (2004). Governance in a Globalizing World. International Journal of Public Administration, 27, 1003–1029. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-200039883

- Kapai, P. (2011). A principled approach towards judicial review: Lessons from W v registrar of marriages. Hong Kong Law Journal, 41(PART 1), 49–74. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84858394468&partnerID=40&md5=4b055143ba7c5c7bb0d99a19ab6aecd8

- Kariuki, P. (2020). The Changing Notion of Democracy and Public Participation in Cities in Africa: A Time for an Alternative? In Reddy, P. S., & Wissink, H (Eds.), Reflections on African Cities in Transition (pp. 17–38).(Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46115-7_2

- Kashyap, S. C. (2017). Democracy, inclusive governance and social accountability in south Asia. In Ahmed, N. (Ed.), Inclusive governance in south Asia: Parliament, judiciary and civil service (pp. 235–249). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60904-1_13

- Katre, A., Tozzi, A., & Bhattacharyya, S. (2019). Sustainability of community-owned mini-grids: Evidence from India. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-018-0185-9

- Kefale, A. (2014). Ethnic decentralization and the challenges of inclusive governance in multiethnic cities: The case of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. Regional and Federal Studies, 24(5), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2014.971772

- Kempf, A., Mumford, J., Levontin, P., Leach, A., Hoff, A., Hamon, K. G., Bartelings, H., Vinther, M., Stäbler, M., Poos, J. J., Smout, S., Frost, H., van den Burg, S., Ulrich, C., & Rindorf, A. (2016). The MSY concept in a multi-objective fisheries environment - Lessons from the North Sea. Marine Policy, 69, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.012

- Koepke, J. L., & Robinson, D. G. (2018). Danger ahead: Risk assessment and the future of bail reform. Washington Law Review, 93(4), 1725–1807. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85063056750&partnerID=40&md5=c4ddaee4778cb7c256dc28ec443beb46

- Kozina, J., Bole, D., & Tiran, J. (2021). Forgotten values of industrial city still alive: What can the creative city learn from its industrial counterpart? City, Culture and Society, 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2021.100395

- Kumar, A. (2010). Global civil society: Emergent forms of cosmopolitan democracy and justice. In Kumar, A., & Messner, D. (Eds.), Power shifts and global governance: Challenges from South and North (pp. 45–64). Anthem Press. https://doi.org/10.7135/UPO9781843318842.005

- Larner, W., & Craig, D. (2005). After neoliberalism? Community activism and local partnerships in Aotearoa New Zealand. Antipode, 37(3), 402–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00504.x

- Le Meur, P.-Y., Arndt, N., Christmann, P., & Geronimi, V. (2018). Deep-sea mining prospects in French Polynesia: Governance and the politics of time. Marine Policy, 95, 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.07.020

- Lever, J. (2005). Governmentalisation and local strategic partnerships: Whose priorities? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 23(6), 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0535

- Levy, B., & Fukuyama, F. (2010). Development strategies: Integrating governance and growth. The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 5196. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/19915

- Lima, R. Y. M., & Azevedo-Ramos, C. (2020). Compliance of Brazilian forest concession system with international guidelines for tropical forests. Forest Policy and Economics, 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102285

- Liyanage, K. (2017). Gender inclusive governance: Representation of women in national and provincial political bodies in Sri Lanka. In Ahmed, N. (Ed.) Women in governing institutions in South Asia: Parliament, civil service and local government (pp. 117–137). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57475-2_7

- Mackinson, S., & Middleton, D. A. J. (2018). Evolving the ecosystem approach in European fisheries: Transferable lessons from New Zealand’s experience in strengthening stakeholder involvement. Marine Policy, 90, 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.12.001

- Mader, C. (2014). The role of assessment and quality management in transformations towards sustainable development: The nexus between higher education, society and policy. In King, R., Lee, J. J., Marginson, S., & Naidoo, R. (Eds.), Palgrave studies in global higher education (pp. 66–83). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137459145_4

- Malapi-Nelson, A. (2017). The Nature of the Machine and the Collapse of Cybernetics: A Transhumanist Lesson for Emerging Technologies (pp. 1-299). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54517-2

- Manning, C., & Dendere, C. (2018). Mozambique: A credible commitment to peace. In Joshi, M., & Wallensteen, P. (Eds.), Understanding quality peace: Peacebuilding after civil war (pp. 257–274). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315142470

- Markantoni, M. (2016). Low carbon governance: Mobilizing community energy through top-down support? Environmental Policy and Governance, 26(3), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1722

- Mbah, P., Nwangwu, C., & Edeh, H. C. (2017). Elite politics and the emergence of Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. Trames, 21(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2017.2.06

- McAllister, R. R. J., & Taylor, B. M. (2015). Partnerships for sustainability governance: A synthesis of key themes. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 12, 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.01.001

- McCauley, D. (2015). Sustainable development in energy policy: A governance assessment of environmental stakeholder inclusion in waste-to-energy. Sustainable Development, 23(5), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1584

- Mc Lennan, A., & Ngoma, W. Y. (2004). Quality governance for sustainable development? Progress in Development Studies, 4(4), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1191/1464993404ps091oa

- Meagher, K. (2013). Informality, religious conflict, and governance in northern Nigeria: Economic inclusion in divided societies. African Studies Review, 56(3), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2013.86

- Miraftab, F. (2009). Insurgent planning: Situating radical planning in the global south. Planning Theory, 8(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099297

- Misra, H. (2017). Facilitating financial inclusion through E-governance: Case based study in Indian scenario. In T. L. T. L & M. A (Eds.), 4th International Conference on eDemocracy and eGovernment, ICEDEG 2017 (pp. 226–231). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEDEG.2017.7962539

- Muchadenyika, D. (2015). Slum upgrading and inclusive municipal governance in Harare, Zimbabwe: New perspectives for the urban poor. Habitat International, 48, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.003

- Mushtaq, M., & Mahmood, M. R. (2020). Governing diversity: Reflections on the doctrine and traditions of religious accommodation in islam. Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization, 10(2), 190–205. https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.102.11

- Mushtaq, M., & Mirza, Z. S. (2021). Understanding the nexus between horizontal inequalities, ethno-political conflict and political participation: A case study of balochistan. Ethnopolitics. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2021.1920734

- Mustalahti, I., & Agrawal, A. (2020). Research trends: Responsibilization in natural resource governance. Forest Policy and Economics, 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102308

- Naomi, P., Akbar, I., & Firmanzah, F. (2020). A Bird’s eye view of researches on good governance: Navigating through the changing environment. Webology, 17(2), 150–171. https://doi.org/10.14704/WEB/V17I2/WEB17022

- Njock, J.-C., & Westlund, L. (2010). Migration, resource management and global change: Experiences from fishing communities in West and Central Africa. Marine Policy, 34(4), 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.01.020

- Njogu, K., & Wekesa, P. W. (2015). Kenya’s 2013 general election: Stakes, practices and outcome. In Njogu, K., Wekesa, P.W. (Eds.), Kenya’s 2013 general election: Stakes, practices and outcome (pp. 1-388). African Books Collective. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85058913229&partnerID=40&md5=760e8fa050cc11fb16d53e807a4a2d2

- Nunan, F., Menton, M., McDermott, C. L., Huxham, M., & Schreckenberg, K. (2021). How does governance mediate links between ecosystem services and poverty alleviation? Results from a systematic mapping and thematic synthesis of literature. World Development, 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105595

- OECD. (2020). What does “inclusive governance” mean? Clarifying theory and practice (No. 27; OECD Development Policy Papers)

- O’Leary, H. (2018). Pluralizing science for inclusive water governance: An engaged ethnographic approach to wASH data collection in Delhi, India. Case Studies in the Environment, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.1525/cse.2017.000810

- Oni, S., Oni, A. A., Ibietan, J., & Deinde-Adedeji, G. O. (2020). E-consultation and the quest for inclusive governance in Nigeria. Cogent Social Sciences, 6, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1823601

- Othman, Z., & Rahman, R. A. (2011). Exploration of ethics as moral substance in the context of corporate governance. Asian Social Science, 7(8), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n8p173

- Otsuki, K. (2016). Infrastructure in informal settlements: Co-production of public services for inclusive governance. Local Environment, 21(12), 1557–1572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2016.1149456

- Patel, S., Sliuzas, R., & Mathur, N. (2015). The risk of impoverishment in urban development-induced displacement and resettlement in Ahmedabad. Environment and Urbanization, 27(1), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247815569128

- Petriwskyj, A. M., Serrat, R., Warburton, J., Everingham, J., & Cuthill, M. (2017). Barriers to older people’s participation in local governance: The impact of diversity. Educational Gerontology, 43(5), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2017.1293391

- Prasad, K. (2020). Capacity building and people’s participation in e-governance: Challenges and prospects for digital India. In Servaes, J. (Eds.) Handbook of communication for development and social change (pp. 1177–1194). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2014-3_12

- Rahman, N. (2017). Social accountability for inclusive governance: The south asian experience. In Ahmed, N. (Ed.), Inclusive governance in south Asia: Parliament, judiciary and civil service (pp. 179–192). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60904-1_10

- Rindorf, A., Mumford, J., Baranowski, P., Clausen, L. W., García, D., Hintzen, N. T., Kempf, A., Leach, A., Levontin, P., Mace, P., Mackinson, S., Maravelias, C., Prellezo, R., Quetglas, A., Tserpes, G., Voss, R., & Reid, D. (2017). Moving beyond the MSY concept to reflect multidimensional fisheries management objectives. Marine Policy, 85, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.08.012

- Rivera, J. D., & Uttaro, A. (2021). The manifestation of new public service principles in small-town government: A case study of grand Island, New York. State and Local Government Review, 53(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X211003139

- Rodwell, L. D., Lowther, J., Hunter, C., & Mangi, S. C. (2014). Fisheries co-management in a new era of marine policy in the UK: A preliminary assessment of stakeholder perceptions. Marine Policy, 45, 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.09.008

- Roessler, P., & Ohls, D. (2018). Self-enforcing power sharing in weak states. International Organization, 72(2), 423–454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818318000073

- Ros-Tonen, M., Pouw, N., & Bavinck, M. 2015 Governing beyond cities: The urban-rural interface. Geographies of Urban Governance: Advanced Theories, Methods and Practices 85–105. Springer International Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21272-2_5

- Ruhanen, L., Scott, N., Ritchie, B., Tkaczynski, A., & Pechlaner, H. (2010). Governance: A review and synthesis of the literature. Tourism Review, 65(4), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371011093836

- Schweizer, P.-J., & Renn, O. (2019). Governance of systemic risks for disaster prevention and mitigation. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 28(6), 854–866. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-09-2019-0282

- Shahan, A. M., & Khair, R. (2017). Inclusive governance for enhancing professionalism in civil service: The case of Bangladesh. In Ahmed, N. (Ed.), Inclusive governance in south Asia: Parliament, judiciary and civil service (pp. 123–143). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60904-1_7

- Siakwah, P., Musavengane, R., & Leonard, L. (2020). Tourism governance and attainment of the sustainable development goals in Africa. Tourism Planning and Development, 17(4), 355–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1600160

- Simonsen, S. G. (2006). The authoritarian temptation in East Timor: Nationbuilding and the need for inclusive governance. Asian Survey, 46(4), 575–596. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2006.46.4.575

- Singh, A., Singai, C. B., Srivastava, S., & Sivam, S. (2009). Inclusive water governance: A global necessity. lessons from India. Transition Studies Review, 16(2), 598–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11300-009-0091-0

- Smith, J D. (2013). Sudan: Survival depends on getting to inclusive government. American Foreign Policy Interests, 35(6), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803920.2013.855567

- Söderbaum, F., & Taylor, I. (2001). Transmission belt for transnational capital or facilitaton for development? Problematising the role of the state in the Maputo development corridor. Journal of Modern African Studies, 39(4), 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022278x01003767

- Steenbergen, D. J. (2016). Strategic customary village leadership in the context of marine conservation and development in southeast maluku, Indonesia. Human Ecology, 44(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-016-9829-6

- Subramanian, M., & Saxena, A. (2008). E-governance in India: From policy to reality. A case study of Chhattisgarh Online Information System for Citizen Empowerment (CHOICE) project of chhattisgarh state of India. International Journal of Electronic Government Research, 4(2), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.4018/jegr.2008040102

- Techera, E. (2020). Indian Ocean fisheries regulation: Exploring participatory approaches to support small-scale fisheries in six States. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 16(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2020.1704979

- Thompson, L., Conradie, I., & Tsolekile, D. W. (2014). Participatory politics: Understanding civil society organisations in governance networks in Khayelitsha. Politikon, 41(3), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2014.975937

- Thompson, V. L. S., & Hood, S. M. (2016). Academic and community partnerships and social change. In Tate, W. F., Staudt, N., Macrander, A. (Eds.), Diversity in higher education (pp. 127–149. Vol. 19). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-364420160000019007

- Tremblay, D.-G. (2010). Paid parental leave: An employee right or still an ideal? An analysis of the situation in Québec in comparison with North America. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 22(2), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-009-9108-4

- Ullah, I., & Kim, D.-Y. (2021). Inclusive governance and biodiversity conservation: Evidence from sub-saharan Africa. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073847

- Ulnicane, I., Eke, D. O., Knight, W., Ogoh, G., & Stahl, B. C. (2021). Good governance as a response to discontents? Déjà vu, or lessons for AI from other emerging technologies. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 46(1–2), 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/03080188.2020.1840220

- Uster, A., Beeri, I., & Vashdi, D. (2019). Don’t push too hard. Examining the managerial behaviours of local authorities in collaborative networks with nonprofit organisations. Local Government Studies, 45(1), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1533820

- Vagliasindi, G. M. (2018). Targeting transnational environmental crime through a multifaceted approach: Towards an inclusive governance of serious threats to sustainable development. Transnational Crime: European and Chinese Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351026826-13

- van der Grijp, N., van der Woerd, F., Gaiddon, B., Hummelshøj, R., Larsson, M., Osunmuyiwa, O., & Rooth, R. (2019). Demonstration projects of nearly zero energy buildings: Lessons from end-user experiences in Amsterdam, Helsingborg, and Lyon. Energy Research and Social Science, 49, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.006

- van Voorst, R. (2016). Formal and informal flood governance in Jakarta, Indonesia. Habitat International, 52, 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.023

- Vernon, J., Essex, S., Pinder, D., & Curry, K. (2005). Collaborative policymaking: Local Sustainable Projects. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.06.005

- Whitchurch, C., & Gordon, G. (2013). Reconciling flexible staffing models with inclusive governance and management. Higher Education Quarterly, 67(3), 234–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12013

- Widianingsih, I., Paskarina, C., Riswanda, R., & Putera, P. B. (2021). Evolutionary study of watershed governance research: A bibliometric analysis. Science and Technology Libraries. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2021.1926401

- Wise, G., Dickinson, C., Katan, T., & Gallegos, M. C. (2020). Inclusive higher education governance: Managing stakeholders, strategy, structure and function. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1525698

- Wright, H., Vermeulen, S., Laganda, G., Olupot, M., Ampaire, E., & Jat, M. L. (2014). Farmers, food and climate change: Ensuring community-based adaptation is mainstreamed into agricultural programmes. Climate and Development, 6(4), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.965654

- Ziervogel, G. (2019). Building transformative capacity for adaptation planning and implementation that works for the urban poor: Insights from South Africa. Ambio, 48(5), 494–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1141-9