Abstract

The food price crisis of 2007–2008 and the recent resurgence of food prices have focused increasing attention on the causes and consequences of food price volatility in international food markets and the developing world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Agricultural Price Index was 34% higher as of 30 June 2022, compared to January 2021. This paper reviews increasing food crisis in Africa in the wake of climate change, COVID-19, and the Russia–Ukraine war and the implications on Africa’s food security stability. Climate change is affecting the fundamental basis of agriculture through changes in temperature, rainfall, and weather, and by intensifying the occurrences of floods, droughts, and heat stress. COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the production and supply chains, while the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war continues to disrupt the global food market and food prices. SSA is susceptible to the effects of this war, and this has already resulted in high demand for food commodities and increased food prices. The study calls for the need for the international community to establish a strategic food reserve to face food crises triggered by armed conflicts or climate-induced disasters and pandemics. This mechanism may facilitate reactive interventions that help to contain the human security implications of food crises, thus fostering peace. Solutions also lie in implementing programs and policies informing the monitoring of weather shocks and advancing supporting to those impacted. Additionally, the governments of SSAs should embrace domestic production of farm inputs such as fertilizer to avoid overdependence on imports which are susceptible to wars and conflict.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The tripartite connection between climate change, Covid-19, and Russia–Ukraine war is pushing a food crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. The global Covid-19 pandemic that upended lives has superimposed on existing challenges to Africa’s food systems. Further, climate change’s deleterious effects as evidenced by dwindling crop production, social unrests, and a confluence of other factors such as high poverty levels continue to cripple Africa’s food system, ushering a precarious food situation in the proportion of a crisis. Given the urgency and the high stakes of food crisis in crippling human and economic development in the region, the review provides insights intended to resolve the disconnect in food systems propelling food crisis. These study findings are key in laying the groundwork for long-term responses, cognizant of the inevitability of livelihood disruption, it emphasizes the coping mechanism from such protracted crises. While the study outlines some short-term interventions during crises, it further offers policy insights to address the structural causes of the protracted food crisis in the region.

1. Introduction

A serious crisis has gripped the world food system. The world’s existing food supply cannot sustain the needs of the populace without sacrificing the welfare of future generations. Therefore, a catastrophe for humanity is imminent. Governments, scientists, and agriculturalists are debating how to accomplish the enormous job of feeding 2 billion extra people by 2050. Vaughan (Citation2020) notes that unlike the 2007/2008 food crisis, when the root problem was a scarcity of food, the big issue this time is economic downturns hitting the ability of millions of people to be able to afford food. Massive food shortages in several African nations have been brought on by the confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and conflicts like the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war. Food prices have increased, according to the FAO’s index of widely traded food commodities, which includes cereals and dairy products. For instance, the Agricultural Price Index was 34% higher as of 30 June 2022, compared to January 2021. In comparison to January 2021, the price of maize was 47% higher, the price of wheat was 42% higher, and the price of rice was around 8% lower.

An alarming figure of 193 million people experiencing severe food insecurity across 53 countries has once again been highlighted by the 2022 Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC; FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, Citation2022). The fact that the number represents an increase of 80% from the 108 million people who were acutely food insecure in the GRFC 2021 study, which shows an exponential rate of hunger, is more worrying. In particular, 40 million people in 36 countries reported emergency or worse (IPC/CH Phase 4 or above) conditions, while more than 500,000 individuals, primarily from Ethiopia, Sudan, Madagascar, and Yemen, faced a catastrophe (IPC/CH Phase 5)—starvation and death in 2021 (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, Citation2022). In West Africa, food prices have increased by 20–30% over the past 5 years (Iacobucci, Citation2022).

Despite Africa’s immense agricultural potential, the continent remains to be a net importer of food. The region’s rich land, fisheries, natural resources, and biocultural environment have not succeeded in advancing the food system there. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), smallholder farmers who raise livestock and grow crops for their own consumption account for the majority of agricultural production (Hamann, Citation2020). Arguably, the status of food security in the region is faced with setbacks that make Africa’s smallholding inadequate to meet the food demands of the growing population. The food production systems in the region have over time failed to meet the food demand of the region. In West Africa, there are currently 27 million hungry people and 11 million more are at risk of going hungry over the next few months (Iacobucci, Citation2022). In advanced economies, expenditure on food accounts for 17% of total spending, whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, that percentage rises to 40%, according to a recent Financial Times article citing IMF estimates. In an emergency meeting of African Ministers of Finance and Ministers of Agriculture on the looming food security crisis in Africa, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Managing Director noted that growth in SSA was expected to slow to 3.8% in 2022 from 4.5 in 2021. Notably, the current economic crisis and the rise in food prices may also have a considerable influence on people’s nutrition and health, particularly in developing countries.

Questions about how to maintain sustainable food systems loom large as food demand in Africa soars and the continent experiences rapid transformation. Determinants of food crisis should be considered when developing and implementing policies to reducing food insecurity. Against this backdrop, this literature review article sought to close the gap in the body of knowledge by reviewing published knowledge on the food crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, this review synthesizes the causes of looming food crisis in sub-Saharan Africa by situating the impact of covid-19 pandemic, climate change, and Russia–Ukraine war on the African food system in order to draw lessons for appropriate policy response. Further, the effects of food crisis in SSA suggest that this review is timely, urgent, and highly needed. This study intends to provide important information to policymakers, practitioners, academics, and other concerned bodies to intervene and improve food security status of households in the region. This article has the potential to contribute to this sparsely research subject (food crisis) in policy and practice regarding best practices, resilience, and strategies in order to reduce the vulnerability of agricultural systems to climate change, conflicts, and future pandemics, thus alleviating food insecurity in Africa

2. Methodology

This study was synthesized as a review article based on a thorough analysis of both published and unpublished journals, articles, and published books produced in English language. A single primary systematic literature search was performed in the following databases: Google Scholar, Web of Science, Science Direct, RefSeek, and Scopus. Peer-reviewed scientific publications were searched using keywords, probable titles, and logical operators and filtering techniques. The researcher used search terms selected from the six main keywords, which are Food crisis, Food Crisis, Covid-19, Climate Change, Russia-Ukraine War and Sub-Saharan Africa. These six keywords were identified with synonyms derived from the literature. These keywords were then combined into a complete search term string, connected with the Boolean operators “OR” for synonyms of the same keyword and “AND” for different keywords. This string was then entered into selected databases to retrieve data.

To reduce positive-result publication bias, and provide complete information, the so-called “grey literature” was also searched to identify evaluation reports available from the websites of identified organizations and institutions, including the portals of donor governments. The grey literature search included web portals and general internet searches using different search engines and strategies. Figures were employed as a reviewing technique to condense the work in addition to narrations.

3. Review of related Literature

3.1. Definition and concepts of food crisis

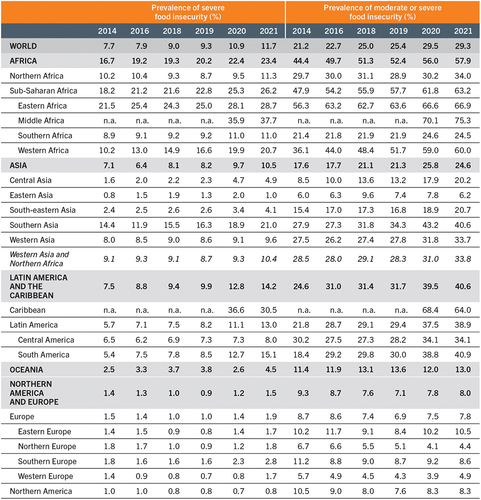

A food crisis is regarded as a situation when food security is abruptly threatened (Lee et al., Citation2012). The Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) provides a framework to understand a food situation among households and areas using a five-phase scale. Based on this framework, a food crisis situation falls under phase 3, where households experience food consumption gaps characterized by high and above-usual acute malnutrition (IPC Global Partners, Citation2008). More broadly, a food crisis exists when a household exhausts their livelihood assets to access and afford food. In applying a livelihood approach, the IPC incorporates other sectoral crises notably from health, water, sanitation, protection, and shelter among others. An acute malnutrition and food crisis situation further depicted by 2,100 kcal ppp is an important phase for intervention to redress underlying causes with the goal to reduce further stripping of livelihood assets to access and afford food. According to FAO report “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022”, the number of food-insecure people has increased each year since 2014: from 500 to 800 million in Africa, and worldwide by 50% to 2.3 billion, this translates to a prevalence of 26.2% in SSA, 23.4% in Africa, and 11.7% in the world as in Figure (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, Citation2022). Helping households cope with the food situation is important in stopping any possible deterioration into a humanitarian emergency or chronic poverty that may take years to end.

Figure 1. Prevalence of food insecurity at severe level only, and at moderate or severe level, based on the food insecurity experience scale, 2014–2021 (source: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, Citation2022).

Rising food prices is one of the contributing factors to our food situation predicament. The underlying causes of rising food prices relate to a complex set of interrelated factors. Firstly, food price volatility has been recently believed to stem from the growing demand for bioenergy crops. Secondly, from a global perspective, the food crisis has roots in globalization where national agricultural policies are oriented toward external markets instead of domestic food self-sufficiency goals required to cushion citizens from food crisis situations. The dependence on the international market for domestic food needs exposes countries to price transmissions that affect food prices for consumers. Lastly, agriculture has been integrated into the global financial markets implying that the transmission of fluctuations in market conditions dictates the prices of agricultural commodities (Margulis, Citation2009).

As reported by the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE): Every human being has the right to adequate food. However, the progressive realization of this right will not be achieved without more sustainable food systems that facilitate healthy and sustainable food choices (HLPE, Citation2017). In 2007–2008 and in 2010–2011 food prices suddenly increased following a three-decade hiatus when food prices were stable and low. In January 2004 to May 2008, rice prices increased 224%, wheat prices increased 108%, and corn was up 89%. This price spike contributed to food insecurity worldwide, civil unrest in several nations, and generated appeals for food aid from 36 countries. Under global and African human rights law everyone has the right to sufficient and adequate food. To protect this right, governments are obligated to enact policies and initiate programs to ensure that everyone can afford safe and nutritious food.

3.2. Drivers of the food crises in sub-Saharan Africa

3.2.1. Climate change and food crisis in Africa

Climate variability and change are a significant threat to food security in Africa and many regions of the developing world, which are largely dependent on rain-fed agriculture. Climate change affects all dimensions of food security (food availability, food accessibility, food utilization, and food system stability), thus, impacting human health, livelihood assets, food production and distribution, and markets (FAO, Citation2008). The food crisis in the sub-Saharan continent has its underlying cause in the prolonged periods of drought, floods, other natural hazards, and man-made climate change stemming from the overexploitation of nature (WFP, Citation2022). Environmental disruptions have contributed to the region’s inability to feed itself as demonstrated by the rising levels of undernourishment, with one out of three of the 155 million under-five-year-old children affected by stunting being found in sub-Saharan Africa (Global Nutrition Report, Citation2020). Climate change threatens to wreak havoc on food production by increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events and depressing agricultural yields. Floods are inundating agricultural land, drought is making crop cultivation impossible, and pests and insects are wiping out entire crop fields. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in its Status of the Climate in Africa Report points out that 2019 alone was one of the worst years for Africa having been hit by extreme weather and climate events. For example, Tropical Cyclones Idai and Kenneth made huge destruction with a resultant humanitarian crisis. For some regions, especially Southern Africa, the situation was direr given a previous protracted drought in 2014–2016. In other parts of the region within Eastern Africa, erratic rains and heavy rains in 2019 triggered widespread floods in Somalia, Kenya, and Sudan, displacing people and damaging crops and killing livestock (WMO, 2021). In Kenya, climate change in West Pokot has changed and is already having implications for food security (Obwocha et al., Citation2022).

The nexus between global environmental change and food crises in SSA have been widely discussed (Kakpo et al., Citation2022; Reed et al., Citation2022). Dagar et al. (Citation2021) assessed the technical efficiency of individual farmers from different agro-climatic zones and the means for obtaining sustainable agricultural production. From their findings, it is important to evaluate technical efficiency of various agro-climatic zones to determine suitable crops for various agro-climatic zones as such evaluation will stem the excess use of natural resources and intensive crop production harmful to the environment. Lottering et al. (Citation2020) make a case that with agriculture being the largest economic activity in the region, the increasing climate variability, and extreme weather events such as droughts have been the reason for crop failure, high food prices, and poor health. With the region’s growing arid and semi-arid conditions, vulnerability to droughts will remain high pending government policies promoting climate change adaptation and mitigation.

From the foregoing, it is obvious that the direct impact of climate change on food crop production will worsen with on-going weather shocks. Africa’s food system is caught in this fix. Thus, strengthening Africa’s food system is inextricably linked to environmental sustainability. The systemic vulnerabilities in the food systems call into question appropriate strategies that can be implemented for environmental sustainability given the widespread impact of climate change in the region. Environmental sustainability as a concept implies a condition of balance, resilience, and interconnectedness enabling human society to benefit from the supporting ecosystems without compromising their regenerative capacity of biological diversity (Morelli, Citation2011). Environmental degradation associated with climate change affects human life in its all facets. Human activities, including agriculture and extractive services such as mining, contribute significantly to environmental pollution through the emission of greenhouse gases, consequently initiating climate change. In areas, mostly developing countries, reliance on low-farming technologies, and carbon-intensive industrial technologies, and poor energy production have put the countries on a rough path in reversing the associated pollution impacts. As Khan et al. (2021) note, energy consumption is the main source of environmental degradation, thus countries should shift from carbon-laden to carbon-free technologies both at the industrial and domestic levels. Food systems encompass production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption, and disposal, all accounting for high energy consumption with tremendous impacts when not aligned with environmental protection goals. The long-term solution to resolving the climate-related food crisis lies in implementing CO2 emission-inhibiting policies in sectors supporting food systems (Rahman et al. Citation2021; Murshed et al. Citation2021), and the transition to a low-carbon economy is instrumental for the economic growth of countries still dependent on fossil fuels for energy production (Murshed et al. Citation2021). Further, achieving carbon neutrality can be instrumental in pushing human development index in the developing world through positive impacts of sectors such as health.

3.2.2. Food insecurity in sub-Saharan Africa under Covid-19

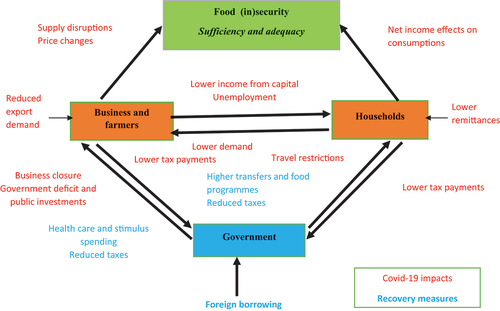

The COVID-19 pandemic created one of the worst production shocks to the food economy in the region. The highly contagious COVID-19 virus compelled the World Health Organization to mobilize nations to get ready for historically unprecedented pandemic events that could endanger lives (WHO, Citation2020). Soon after, countries effected measures to suppress and mitigate the spread of the contagious virus where travel restrictions and border closures were implemented. It can be noted that measures to contain the spread of the virus have had profound effects on household food and nutrition security in low-income regions. The mitigation and suppression efforts of the infection have created both direct and indirect effects on Africa’s food systems. Figure summarizes the impacts of covid-19 and the attendant effects on food security outcomes in SSA.

Figure 2. Interactions between COVID-19 impacts and government recovery measures leading to food security outcomes. Adapted from Nechifor et al. (Citation2021).

According to FAO et al. (Citation2019), 80 million people were facing food insecurity before the pandemic, where the pandemic has worsened their situation. The pandemic’s immediate consequences on the price of basic food items have been more profound. Even though there had been a decreasing trend in agricultural prices in real terms due to the productivity improvements in agriculture, the COVID-19 global pandemic has made the price of agricultural prices to shoot from 2020 to present (OECD/FAO, Citation2022). Food shortages resulting from disrupted global supply chain networks were the initial setbacks to SSA food system that is not resilient to external shocks. Further, the situation was adversely compounded by loss of jobs, making it hard for households to earn income for purchasing food. Again, SSA food system since the outbreak of the pandemic has been hit by high input prices and labour shortages that have consequently reduced agricultural production in the region (Mthembu et al., Citation2022; World Bank: Africa’s Pulse, Citation2020). With labour being a central input in agricultural production, measures enacted early in height of COVID-19 breakout greatly reduced the amount of workforce for agricultural production considering only essential services were exempted from operating (Morsy) Further, the economic update indicated that the region’s growth forecast could fall sharply from 2.4% in 2019 to between −2.1 and −5.1 in 2020. Still, the World Bank forecasted that COVID-19 pandemic could lead to a contraction of the agricultural production by 2.6% to 7%, while at the same time food imports declining by 13–25% due to high transaction costs and reduced demand.

Beyond the immediate effects, the COVID-19 pandemic has had long-term effect that may continue past the recovery period. Thurlow (Citation2020) opined that the pandemic would see poverty rates increase by 15 and 27% in Rwanda and Nigeria, respectively. Again, the economic shocks would exacerbate food and nutrition security in countries affected by environmental disasters prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. Owing to the severe drought and disastrous impact of desert locust that invaded farmers in Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya, the state of food security in the bigger part of East Africa has greatly suffered (FAO, Citation2020).

The majority of countries that reported worse food insecurity phase in 2021 had conflicts as a major contributing factor in addition to economic shock from COVID-19. More notably, the Central and Southern regions of Africa were devastated by the pandemic through job losses that consequently hampered food access as many households lost means of livelihood (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, Citation2022). Insecurity in the Central Africa has always disrupted trade in the region, with the outbreak of pandemic, the situation completely deteriorated. Comparably, the food crisis in East Africa, though aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, had been initiated by other factors such as currency depreciation, loss of job opportunities due to Covid-19 movement restrictions, and food price volatility as witnessed in Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan (ILO, Citation2021).

Subsequently, the economic shocks brought by COVID-19 are an impetus to reimagine and reinvent activities and sectors central to food production. In particular, the agricultural sector in the region still has potential for ensuring food stability. The disruption in supply chain and travel restrictions during conflicts and pandemic require modernisation of food supply chain to predict and respond to disruptions when they occur. According to Zhu et al. (Citation2022), reliance on technology such as the 3-D printed food technology offers a new future for developing personalized diets out of which individual’s nutritional requirements can be easily determined. Fighting malnutrition for certain vulnerable populations such as lactating mothers and children should be a priority in developing nations post-pandemic for creating healthy systems that enables children to attain their potentials in life without the attenuating circumstances brought about by hunger and malnutrition.

3.2.3. Russia–Ukraine war and food crisis in Africa

Globally, the debate on the impact of war/conflict on food security and food crisis remains a policy issue. Therefore, understanding the relationship between food security and war through monitoring food security status in countries affected by peace instability is very important in informing policy making (Martin-Shields & Stojetz, Citation2019). Global food prices have increased nearly 52% since 2019, driven by the global Covid-19 pandemic and shortages caused by the war in Ukraine (Okou et al., Citation2022). Russia’s invasion in Ukraine has led to historically sharp increases in staple food items (McGuirk & Burke, Citation2022). Ben Hassen and El Bilali (Citation2022) noted that the war is likely to jeopardize the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 1 (No poverty), SDG 2 (Zero hunger), and SDG 12 (Responsible consumption and production).

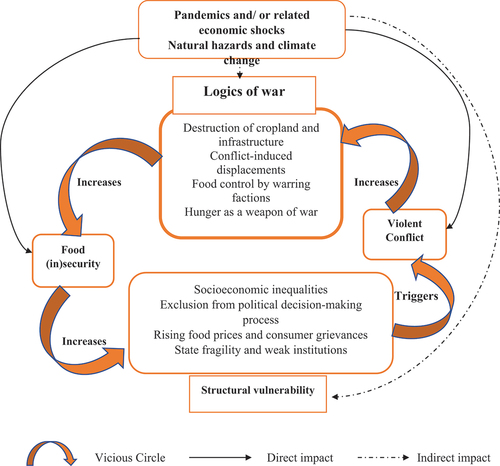

Previous studies have indicated adverse effects of wars/conflicts on food security and food crisis. In West Africa, Ujunwa et al. (Citation2018) found that due to armed conflict, future food insecurity and food prices are projected to worsen in the near future. Mercier et al. (Citation2017) found that war between countries affects the ability of household members to pursue work due to interruption in household member composition. According to Olonisakin (Citation2011) and Afolabi (Citation2009), conflicts such as the Niger Delta/Boko Haram conflict in Nigeria and Dagbon chieftaincy crisis in Ghana have resulted in an interruption in food production thus influencing agricultural food supply (Afolabi, Citation2009). Moreover, FAO (Citation2015) report indicated that armed conflicts in Northern Mali, North Eastern Nigeria, and Central African Republic have resulted in disruption and low supply of labour for agricultural activities due to displacement of the rural population. Further analysis had indicated that the increase in global food prices has been fueled by the active and intensity of war in different regions (Hendrix & Brinkman, Citation2013). Similarly, the findings of Sambe et al. (Citation2013) on the impact of communal violence on food security in Africa reinstated that as a result of the destruction of arable land, forest and livestock reserves, food availability and access became difficult for many households. Ujunwa et al. (w) further confirmed that, due to the significant negative effect of conflict on food security in West Africa, global initiatives fighting food insecurity should identify the drivers of armed conflicts between countries and come up with strategies for reducing war in the region. A previous study (Sneyers, Citation2017) reported that some conflict-affected countries also suffer from natural disasters, e.g., prolonged drought in Somalia has undermined food production, markets, and consumption resulting in food insecurity. Furthermore, Azechum (Citation2017), argued that one of the major causes of food insecurity in Northern Ghana is related to wars among the population which has significantly affected agricultural productivity (Nkegbe et al., 2017). These findings were not at odds with those of and FAO (Citation2017) that conflicts/war disrupts agricultural food production. Mugizi and Matsumoto (Citation2021) also affirm that war-induced land conflicts negatively affect agricultural productivity thereby reducing farmers’ incentives to invest in the farms due to insecure land rights. Furthermore, Adelaja and George (Citation2019) report that security risks occasioned by frequent episodes of violent conflict could prevent farmers from leaving their villages and work in remote farm fields thus having a direct impact on timely planting and harvesting activities thereby leading to disrupted agricultural planting calendar hence low productivity. Further findings showed that the number of households that were food insecure in Djibouti increased from 5.6 Million in 2015 to 9.7 million households in 2016 as a result of conflict violence (FSIN, Citation2017; Sabogu et al., Citation2020). Moreover, Opoku (Citation2015) found that the war between smallholder farmers and Fulani herdsmen in the Agogo area in the Ashanti region resulted in the destruction of crops and a reduction in agricultural production. Similarly, Uyang et al. (Citation2013) found that communal land conflicts in Obudu local government area in Nigeria has increased food insecurity in the region. Consistently, Massoi (Citation2015) reported that in Morogoro region, Tanzania land conflicts were found to disrupt access to agricultural resources like land, water, and food stores forcing households to change their dietary preferences. Figure summarizes the vicious cycle of violent conflicts and food security.

Figure 3. The vicious cycle of violent conflict and food insecurity (Adapted fromKemmerling et al. (Citation2022)).

Russia and Ukraine are major global food producers and exporters (Dongyu, Citation2022). Even though these two protagonists in the war are not extensively the determinant powers in the global economy, they play crucial roles in specific commodities. Both Russia and Ukraine account for 14% of the global wheat production and provide nearly 30% of global wheat export (Paulson et al., Citation2022). Russia is the leading global exporter of wheat while Ukraine is the fifth largest (Gabelli, 2019). Russia–Ukraine war has led to high prices of food all over the globe and exacerbated hunger in many countries in Africa (Nchasi et al., Citation2022). The economic fallout is imminent in SSA with the continued Ukraine–Russia war. Ukraine and Russia are key strategic trade partners to most countries in SSA through their grain and fertilizer exports. Of the 30% global wheat exported to the world’s wheat market, Africa is the major destination. In regard to Africa, wheat is a hugely important food import, accounting for half of Africa’s $ 4.5 billion trade with Ukraine and 90% of Africa’s $ 4 billion with Russia (Paulson et al., Citation2022). Russia and Ukraine also account for 12.5% of global maize supply and other items such as rapeseed, sunflower seed and oil (FAO, 2022). The inability of Ukrainian and Russian agricultural commodities to reach global markets has led to unnecessarily higher prices disrupting the global market and worsening the situation in sub-Saharan Africa, which is most vulnerable (Paulson et al., Citation2022).

The war in Ukraine—much like the COVID-19 pandemic—highlights the fragility of our current food system with its over-reliance on fossil fuel-derived chemical inputs and global commodities trade, and points to the need for a more resilient, local, and diverse food system. Out of the Russian war against Ukraine, a looming food crisis is already visible. In what has been termed “hunger and grain to wield power”, Russia’s continued bombing of grain warehouses, blockading of Ukrainian ships at the Black Sea, portend a global crisis that will take years to overturn. The crisis once again invites the discussion surrounding boosting domestic agricultural production versus the reliance on global trade to provide stable source of food (OECD/FAO, Citation2022). The road to regional food sustainance is far from achieved bearing that about 80% of African farmers are smallholders whose sole motivation is growing mostly cereals for self use (Suri & Udry, Citation2022). The transformation from smallholder to large-scale farming reliant on modern farming technology is happening at a slow pace considering Africa’s agriculture is characterized by technology and productivity lag largely associated with small sizes of smallholder farms (Suri & Udry, Citation2022). Apart from food, the protracted war, in the words of the Secretary to the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, “supercharging a three-dimensional crisis—food, energy and finance—with devastating impacts on the world’s most vulnerable people, countries and economies”—balancing the three core needs is an uphill task that requires joint efforts of the international community (FAO, IFPRI, WFP, Citation2022).

3.2.4. Other economic causes of food crisis in sub-Saharan Africa

Food systems interconnect with other sectors such as the environment. The encompassing elements of the system such as production, distribution, consumption, waste disposal, and the marketing system as aforementioned closely interact with the environment leading to environmental problems that call for governance regimes to address the environmental problems (Clapp & Scott, Citation2018). Issues pertaining to food safety and quality during a crisis are critical in meeting people’s health outcomes thus necessitating food governance. Formal and informal rules and regulations continue to shape the food system, and they can be limiting in the quality of food, access to market and food supplies in the market. With the food markets have several actors, the interrelationship among these actors and their competing interests, if not well managed, can turn chaotic and counterintuitive to promoting food systems. With the interdependencies of some of the actors, when there is lack of coherence, and unity in purpose, the roles executed by the actors within the food systems can lead to a disjointed system that further deteriorates food security situation (Drimie & Pereira, Citation2016). Equally, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO; Citation2011) outlines seven principles that should amount to good governance, and more primarily, the rule of law is instrumental in ensuring good governance. However, incidences of corruption within governmental and non-governmental institutions can influence the policies that regulate the food market (Bensassi & Jarreau, Citation2019).

Apart from governance, the tax regime of different countries can limit cross-border trade, exposing some regions to food crises. The existence of trading blocs in the regions implies that free flow of goods is limited by the tax regimes. However, a tax levied on imports may help strengthen domestic production when there is stiff competition.

4. Conclusion and policy implications

This article reviewed the literature on the contributing factors to the looming food crisis in Africa and which espoused four fascinating themes: 1) Climate change adaptation strategies and food insecurity, 2) Impacts of covid-19 on Food security, 3) Impacts of Russia–Ukraine War on food security, and 4) Other economic causes of food crisis. Results revealed that the current looming “food crisis” is a result of several interacting factors simultaneously affecting the supply and demand functions of food systems. The current crisis requires immediate action, but it should also spur a more comprehensive response to the needs of a considerable proportion of the global population, especially in SSA, which is experiencing chronic food insecurity. The impetus for these policy and practice changes is clear.

In light of climate change, major issues point to how the agricultural policies interface with efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change, and how agricultural policies respond to the impact of climate change on food production. Besides, it also takes the contribution of researchers and policymakers to employ coping strategies consequently reducing vulnerability to climate change effects considering people’s low capacity to adapt and cope with extreme weather events. Solutions lie in implementing programs and policies informing the monitoring of weather shocks and advancing supporting to those impacted. Such interventions cushion small-holder farmers and the poor in the rural areas of SSA from the biting effects of drought on food prices and food availability as demonstrated by the region’s low trend in cereals' yield production compared with other regions

Given the interdependence of the world’s food markets, shocks in Russia and Ukraine—both significant exporters and producers of food—have an effect on food supplies and food systems. Increased oil prices have an impact on food production and transportation costs, while restrictions or disruptions in the grain trade directly expose agricultural markets in SSA. Many African nations may need to rely on other significant suppliers given their dependence on food imports to cover the gap left by the disruptions in supply activities from the Black Sea region. Additionally, this is a chance for African nations to expand intra-African food commerce in order to address domestic food consumption needs.

Improving living standards through gainful employment and poverty reduction initiatives has been advocated by the UN agencies. The global initiative, SDGs, is a hallmark of commitment by the global community to eradicate hunger and poverty while supporting sustainable production and consumption across all sectors. A functioning food system is instrumental in attaining improved living standard, avoiding implications on health and developmental issues harmful to the countries’ full labor employment. To achieve this developmental milestone, Africa should embark on structural transformation. The small-scale farmers forming the majority farmers are critical for food sovereignty although their engagement in semi-subsistence farming slows economic growth. Central to the structural transformation in Africa is the movement of labour from low-productivity semi-subsistence agriculture to more productive manufacturing and service sectors.

For African nations to stabilize their food supply and prices and ensure domestic food availability and affordability, it is essential that they maintain viable strategic food reserves in response to future pandemic like the COVID-19 global pandemic. Lastly, African governments should also support continuous climate change monitoring, intensified early warning systems, and the dissemination of relevant information to farmers. Building resilient, climate-smart, and competitive food systems are essential for an African nation’s long-term success. By acting now, nations may create more productive and resilient food systems in sub-Saharan Africa, ensuring food security both during and after the pandemic and wars while combating climate change. The successful implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area is projected to help food security in Africa (AFCFTA). The African Continental Free Trade Area promises that via greater economic diversity, jobs and revenue will be created to combat poverty and food insecurity.

5. Limitations of the study

Like all studies, this study is not without limitations. This study contributes to the scant literature on causes of the looming food crisis in SSA in the context of climate change, COVID-19, and Russia–Ukraine war and informs policymakers on various interventions and decision-making to improve food security in the region. The study did not delve deeper into other economic causes of food crisis in SSA. Secondly, our review was limited to published materials indexed in the databases and grey literature we chose to search. Additionally, we were only able to work with studies written or translated into English language which makes it likely that we missed important articles published in other languages. Nevertheless, we argue that the bibliographic databases’ search strategy was comprehensive and was designed in a way that generated articles based on multiple keywords and their synonyms. These limitations should be kept in mind when evaluating the conclusion of our study. While there are limitations to the scope of this study, the results provide lines of enquiry worthy of further investigations. Additional research is needed to examine other micro- and macro-economic causes of food crisis in SSA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kevin Okoth Ouko

Kevin Okoth Ouko is a Research and Policy Analyst for Rethinking Africa Development at Jesuit Justice and Ecology Network Africa (JENA) under Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar (JCAM). He was previously a Part-Time Lecturer of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Management at Maseno, Kibabii, Laikipia and Rongo Universities, Kenya where he taught for over 4 years. Kevin is also a Doctoral Fellow in Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya. He holds Master of Science in Agricultural and Applied Economics (CMAAE) of Egerton University, Kenya/University of Pretoria, South Africa. His areas of policy analysis, research and publications are majorly on food security, food systems, food governance/sovereignty, climate change, green transition, agricultural value chain analysis and development, technology adoption, poverty dynamics, livelihoods and employment, public debt, finance, gender and youth dynamics, and impact evaluation.

Modock Oketch Odiwuor

Modock Oketch Odiwuor is Master of Science Student in Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Kenya. Modock holds a Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Economics of Egerton University, Kenya. He is currently a private consultant in food systems research and policy.

References

- Adelaja, A., & George, J. (2019). Effects of conflict on agriculture: Evidence from the Boko haram insurgency. World Development, 117, 184–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.01.010

- Afolabi, B. T. (2009). Peacemaking in the ECOWAS region: Challenges and prospects. Conflict Trends, 2, 24–30. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC16047

- Azechum, A. E. (2017). Agricultural policies and food security: Impact on smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana. Saint Mary University.

- Ben Hassen, T., & El Bilali, H. (2022). Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war on global food security: Towards more sustainable and resilient food systems? Foods, 11(15), 2301. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11152301

- Bensassi, S., & Jarreau, J. (2019). Price discrimination in bribe payments: Evidence from informal cross-border trade in West Africa. World Development, 122, 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.023

- Clapp, J., & Scott, C. (2018). The global environmental politics of food. Global Environmental Politics, 18(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00464

- Dagar, V., Khan, M. K., Alvarado, R., Usman, M., Zakari, A., Rehman, A., & Tillaguango, B. (2021). Variations in technical efficiency of farmers with distinct land size across agro-climatic zones: Evidence from India. Journal of Cleaner Production, 315, 128109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128109

- Dongyu, Q. (2022). New Scenarios on Global Food Security based on Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Brief. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/new-scenarios-global-food-security-based-russia-ukraine-conflict

- Drimie, S., & Pereira, L. (2016). Advances in food security and sustainability in South Africa. In Advances in food security and sustainability (Vol. 1, pp. 1–31). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.af2s.2016.09.002

- FAO. (2008). Climate change and food security: A framework document. Food and Agricultural Organization of United Nation.

- FAO. (2015). The state of food insecurity in the world, meeting the 2015 international hunger

- FAO. (2017). The state of food security and nutrition in the World 2017: Building resilience for peace and food security. Food and Agricultural Organization.

- FAO. (2020). COVID-19: Our hungriest, most vulnerable communities face “a crisis within a crisis”. Fao.org. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1269721/icode/

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2019). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Rome, FAO. https://www.wfp.org/publications/2019-state-food-security-and-nutrition-world-sofi-safeguarding-against-economic

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2022). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make healthy diets more affordable. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0639

- FAO, IFPRI, WFP. (2022). 2022 Global report on food crises. https://www.fao.org/3/cb9997en/cb9997en.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2011). Good food security governance: The crucial premise to the twin-track approach. Background paper ESA Workshop.

- FSIN. (2017). Global report on food security crisis. Food Security Information Network.

- Global Nutrition Report (2020). Action on equity to end malnutrition. Development Initiatives. https://globalnutritionreport.org/documents/566/2020_Global_Nutrition_Report_2hrssKo.pdf

- Hamann, S. (2020). The global food system, agro-industrialization and governance: Alternative conceptions for sub-Saharan Africa. Globalizations, 17(8), 1405–1420. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1730050

- Hendrix, C., & Brinkman, H. (2013). Food insecurity and conflict dynamics: Causal linkages and complex feedbacks. Stability, International Journal of Security & Development, 2(2), 1–18. http://doi.org/10.5334/sta.bm

- HLPE.; 2017. Nutrition and food systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security. Rome Report No.: 12. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7846e.pdf

- Iacobucci, G. (2022). West Africa is facing its worst food crisis in a decade, aid agencies warn. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online), 377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o913

- ILO. (2021). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Seventh edition. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf

- IPC Global Partners. (2008). Integrated food security phase classification technical manual. Version 1.1. FAO.

- Kakpo, A., Mills, B. F., & Brunelin, S. (2022). Weather shocks and food price seasonality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Niger. Food Policy, 112, 102347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102347

- Kemmerling, B., Schetter, C., & Wirkus, L. (2022). The logics of war and food (in) security. Global Food Security, 33, 100634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100634

- Lee, C. L., Lee, M. H., & Lee, J. H. (2012). Food crisis: How to define it statistically? WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 162, 303–312. https://books.google.co.ke/books?hl=en&lr=&id=egvhTDR4SeQC&oi=fnd&pg=PA303&dq=Lee,+C.+L.,+Lee,+M.+H.,+%26+Lee,+J.+H.+(2012).+Food+crisis:+How+to+define+it+statistically%3F+WIT+Transactions+on+Ecology+and+the+Environment,+162,+303%E2%80%93312.&ots=GF4RjaB4iT&sig=1e7PwwZ-EfhG5JYDNq5ryjwMFzI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Lottering, S., Mafongoya, P., & Lottering, R. (2020). Drought and its impacts on small-scale farmers in sub-Saharan Africa: A review. South African Geographical Journal, 103(3), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2020.1795914

- Margulis, M. E. (2009). Multilateral responses to the global food crisis. CABI Reviews, 2009, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1079/pavsnnr20094012

- Martin-Shields, C. P., & Stojetz, W. (2019). Food security and conflict: Empirical challenges and future opportunities for research and policy making on food security and conflict. World Development, 119, 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.011

- Massoi, L. W. (2015). Land conflicts and the livelihood of Pastoral Maasai Women in Kilosadistrict of Morogoro, Tanzania. Afrika focus, 28(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.21825/af.v28i2.4869

- McGuirk, E., & Burke, M. (2022). War in Ukraine, world food prices, and conflict in Africa. VoxEU. org, 26. The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

- Mercier, M., Ngenzebuke, R. L., & Verwimp, H. P., (2017). Violence exposure and deprivation: Evidence from the Burundi civil war. Working Papers DT/2017/14, DIAL (Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation).

- Morelli, J. (2011). Environmental sustainability: A definition for environmental professionals. Journal of Environmental Sustainability, 1(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.14448/jes.01.0002

- Mthembu, B., Mkhize, X., & Arthur, G. (2022). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural food production among smallholder farmers in northern Drakensberg areas of Bergville, South Africa. Agronomy, 12(2), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12020531

- Mugizi, F. M., & Matsumoto, T. (2021). From conflict to conflicts: War-induced displacement, land conflicts, and agricultural productivity in post-war Northern Uganda. Land Use Policy, 101, 105149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105149

- Murshed, S., Paull, D. J., Griffin, A. L., & Islam, M. A. (2021). A parsimonious approach to mapping climate-change-related composite disaster risk at the local scale in coastal Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 55, 102049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102049

- Nchasi, G., Mwasha, C., Shaban, M. M., Rwegasira, R., Mallilah, B., Chesco, J., Volkova, A., & Mahmoud, A. (2022). Ukraine’s triple emergency: Food crisis amid conflicts and COVID‐19 pandemic. Health Science Reports, 5(6), e862. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.862

- Nechifor, V., Ramos, M. P., Ferrari, E., Laichena, J., Kihiu, E., Omanyo, D., Musamali, R., & Kiriga, B. (2021). Food security and welfare changes under COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: Impacts and responses in Kenya. Global Food Security, 28, 100514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100514

- Obwocha, E. B., Ramisch, J. J., Duguma, L., & Orero, L. (2022). The relationship between climate change, variability, and food security: understanding the impacts and building resilient food systems in west pokot county, Kenya. Sustainability, 14(2), 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020765

- OECD/FAO. (2022). OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2022-2031. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/f1b0b29c-en

- Okou, C., Spray, J., & Unsal, D. F. (2022). Staple food prices in Sub-Saharan Africa: An empirical assessment. International Monetary Fund. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?Abstract_id=4171840

- Olonisakin, F. (2011). ECOWAS: From economic integration to peace-building. In T. Jaye & S. Amadi (Eds.), ECOWAS and the Dynamics of Conflict and Peacebuilding (pp. 11–26). Consortium for Development Partnership (CDP).

- Opoku, P. (2015). Economic impacts of land-use conflicts on livelihoods. A case study of pastoralists-farmer conflicts in the Agogo Traditional Area of Ghana. Journal of Energy and Natural Resource Management, 2(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.26796/jenrm.v2i0.38

- Paulson, N., Janzen, J., Zulauf, C., Swanson, K., & Schnitkey, G. (2022). Revisiting Ukraine, Russia, and agricultural commodity markets. farmdoc daily, 12(27). https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2022/02/revisiting-ukraine-russia-and-agricultural-commodity-markets.html

- Rahman, M. M., Bodrud-Doza, M., Shammi, M., Islam, A. R. M. T., & Khan, A. S. M. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic, dengue epidemic, and climate change vulnerability in Bangladesh: Scenario assessment for strategic management and policy implications. Environmental Research, 192, 110303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110303

- Reed, C., Anderson, W., Kruczkiewicz, A., Nakamura, J., Gallo, D., Seager, R., & McDermid, S. S. (2022). The impact of flooding on food security across Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(43), e2119399119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119399119

- Sabogu, A., Nassè, T. B., & Osumanu, I. K. (2020). Land conflicts and food security in Africa: An evidence from Dorimon in Ghana. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 2(2), 74–96. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijmer.v2i2.126

- Sambe, N., Avanger, M., & Alakali, T. (2013). Communal violence and food security in Africa. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 9(3), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-0934347

- Sneyers, A. (2017). Food, drought and conflict: Evidence from a case study onSomalia. HiCN Working Paper. The Household in Conflict Network (HiCN).

- Suri, T., & Udry, C. (2022). Agricultural Technology in Africa. Journal Of Economic Perspectives, 36(1), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.36.1.33

- Thurlow, J. (2020). COVID-19 lockdowns are imposing substantial economic costs on countries in Africa [Blog]. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://www.ifpri.org/blog/covid-19-lockdowns-are-imposing-substantial-economic-costs-countries-africa

- Ujunwa, A., Okoyeuzu, C., & Kalu, E. U. (2019). Armed conflict and food security in West Africa: Socioeconomic perspective. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijse-11-2017-0538

- Uyang, F. A., Nwagbara, E. N., Undelikwo, V. A., & Eneji, R. I. (2013). Communal land conflict and food security in obudu local government area of Cross River State, Nigeria. Advances in Anthropology, 3(4), 193–197. https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2013.34027

- Valero, J., Bratanic, J., & Albanese, C. (2022). Europe considers aid plan to help tackle Africa food crisis. Bloomberg. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-31/europe-considers-aid-plan-to-help-tackle-africa-food-crisis

- Vaughan, A. (2020). Global food crisis looms. New Scientist, 246(3283), 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30946-5

- WFP (2022). Food Security Implications of the Ukraine Conflict. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000137463/download/?_ga=2.48605670.1346592276.1652513347-41481742.1648302216

- WHO. (2020). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. Who.int. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

- World Bank: Africa’s Pulse. (2020). WORLD BANK: Africa’s Pulse. Africa Research Bulletin: Economic, Financial And Technical Series, 57, 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6346.2020.09418.x

- Zhu, X., Yuan, X., Zhang, Y., Liu, H., Wang, J., & Sun, B. (2022). The global concern of food security during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts and perspectives on food security. Food Chemistry, 370, 130830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130830