?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Problem of a low marriage rate is aggravating nowadays in China. It reached a lowest marriage rate of 5.8‰ in 2021. From previous studies, it has been found that the low marriage rate is caused by the factors including economic level, social liberalization, education level, and so on. However, family, as an important factor on this issue especially in a society like China that abides by Confucius’ filial piety very much, was seldom mentioned. In this paper, a study on how parents’ external conditions affect their children’s attitude toward a marriage relationship and how parents’ own attitudes toward a marriage relationship affect their children’s marriage choices indirectly is carried out based on the dataset of China Family Panel Survey (CFPS) in 2018 and the multiple linear regression and logistic regression models are employed for the purpose. The influences of parents’ marital status, parents’ education level and parent’s financial support on children’s expected marriage age and actual marriage status are investigated. It is hoped that the findings in this study could provide valuable reference for a better understanding of young generation’s attitude toward marriage from a different aspect.

1. Introduction

China was a country with high marriage rate and high fertility rate in the early days of the People’s Republic of China. The natural population growth rate reached 22‰ by the mid-1950s (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021). However, the marriage rate in China has decreased rapidly in recent years. According to the China Family and Marriage Report in 2022, the marriage rate in China reached to 5.8‰ in 2020 the lowest in the past 20 years (Liang et al., Citation2022), where the average age of first marriage has postponed by nearly 4 years (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021) and the lifelong never-married proportion increased from 5% in 2010 to 10% in 2020 (Jiang et al., Citation2014). The marriage rate continued to fall and hit a new low 5.4‰ by the end of 2021, which was only 56.6% of 9.9‰ the peak in 2013 (Ministry of Civil Affairs of the China, Citation2021). The continuous decline of marriage rate in recent years has attracted widespread attention in China. The reason of the declined is mainly due to the changes that happened to the young generation at marriageable age.

The young people at marriageable age now are the generation who were born after the implementation of the one child family planning policy. The one child policy was first proposed in 1956 by Chinese government to curb the trend of steep rise in population in the early days of the People’s Republic of China and the specific implementation to the public was started at the end of 1970s. It was first focusing on promoting and educating the public with the late marriage and the late childbearing: “The marriage age for women is 23 years old and 25 years old in rural area; For urban area, the marriage age for both men and women could be a little higher than rural area; The number of children for each family are one to two and the birth interval of two children should over three years.” After 1979, one child policy was implemented which aimed to limit the great majority of families in China to have only one child (Liang, Citation2014). As a result, the fertility rate was persistently maintained at a low level which was 2% after 1975 compared with 3% or even a higher rate before 1965 (J. Zhang, Citation2017). The low fertility rate in 1980s and after has led to a low marriageable population in twenty-first century and then resulted in a low marriage rate.

The other reasons are the social and economic changes due to the reform and opening-up policy in China. Most of marriageable population were born after the reform and opening-up policy. First, they were affected by the western culture so that they may hold a more open mind toward marriage and get married later than their parent generations. Second, a rapid development of economy under the reform and opening-up policy had stimulated the process of urbanization and more and more marriageable young people chose to get married later as the young people from rural areas migrating to urban areas increased. Compared with rural areas, the first marriage age in urban areas is usually later as the people from urban areas often pursuit more education, higher income and better life rather than get married at an early age. Third, the rapid development of economy has also increased the social competitive for young generation. They need to equip themselves with better education level and higher income to face the challenges of the increasing in housing price, cost of childbearing, high bride price, and so on. They need more time to be prepared for the challenges, which also makes them to get married later.

In addition to these influencing factors, there are some indirect factors which may have big impacts on young generations’ attitude toward marriage, and consequently influence the marriage rate. One of them is parents’ influence. As most of young generation at marriageable age were born after 40-year implementation of one child policy and reform and opening-up policy and are the only child in their family, they bear more expectations from their parents to be more outstanding or to become the person their parents want to be. Some parents may even impose their own personal wishes on their children. Parents’ own attitudes toward marriage and the status of their marriage relationship also influence young generation marriage attitude and thus affecting their choice of marriage.

Family is the somatic cell of a society, and the issue of marriage is not only a domestic matter, but also a national event. It is closely related to promoting the long-term balanced development of a country’s population and economy. The marriage rate continuing to decline needs to be paid attention to by all parties in social development in China. It is of great significance to explore the parents’ influence on children’s marriage attitude.

2. Literature review

From previous studies on marriage and divorce rate of the young generation, it has been found that the marriage and divorce rate could be influenced by many factors such as economic development, social influence, and education level.

Su and her colleagues used 12 explanatory variables including GDP, consumption level, education level, birth rate, and so on, to analyse the economic development and social influence with several spatial statistic models. It was found that marriage and divorce rate was related to the development of economic level. Under the rapid development of urbanization, people were more economic independent and occupation mobility was more frequent. Hence, social constraints on individual would be reduced which strengthened the unwillingness of establishing a marriage relationship and resulted in a decrease in marriage rate (Su et al., Citation2018).

Social factor may also affect marriage and divorce rate. Lu and Wang used linear regression to illustrate that marriage rate had decreased while divorce rate increased since the economic reform in 1978 due to three reasons. The first was the social liberalization. After the economic reform, the young generation generally tended to have a higher education level which resulted in an increase in average length of schooling, and as the society became more competitive, the young generation tended to be more self-centred and gave more priorities to personal achievement or individual well-being. Therefore, they were more likely to delay their marriage or even decide to not get married. The second was that the overall cost of marriage had increased. The economic ability of a man owning a house and a car had become a main factor for a woman to judge whether to get married with the man. Young men needed to wait for a longer time before they could save enough money to pay for their marriage. As a result, the big cost for a marriage brought a heavy burden on the young generation and led to a decrease in marriage rate. The third was that the attitude toward marriage and divorce had changed. Chinese society nowadays became more individualist and tolerant, and there was a greater acceptance toward the delay of marriage and divorce, in both laws and public attitude. Due to these three reasons, the author concluded that it was more common for young generation to get married at an older age which resulted in a decrease in marriage rate (Lu & Wang, Citation2014).

Education level is also an important factor and worth discussing. Cui (Citation2011) analysed that why women with a high education level were difficult to find a partner and became “shengnu” which is the leftover women. It could be explained in two aspects. The first is that the external conditions of a man and a woman should be the same in a marriage relationship. For both man and woman who have a high education level and high income, they are more willing to get married with a person who has the same circumstance. The other explanation is that the time cost of getting married for a high educated woman is high. In most families, getting married implies childbearing. Women need to balance their time between working and taking care of children or even giving up their jobs. When the time cost is high, the opportunity cost for a woman to get married and look after children is high and hence, women receiving high education are less willing to get married. Bullough and Ruan (Citation1994) also discussed the effect of education level in an article, and they focused more on how the difference in education level between men and women could affect the marriage rate. They illustrated that women who were unmarried usually received a higher education than unmarried men. The data showed that 74% of unmarried men had only attended primary school or even illiterate and only 7% of them had completed upper secondary school or had a college degree. While for unmarried women, less than 1% of them were illiterate or had only attended a primary school and more than 90% had graduated from secondary school or college or even held advanced degrees. This might be because men had a bias against women who had a better education than themselves. With the increasing in literacy rate, women could have a higher opportunity to receive education, and this might result in a decrease in marriage rate (Bullough & Ruan, Citation1994).

The change in the division of labour in a family could also be a factor for low marriage rate. In a traditional family in the past, men needed to work outside to support their families, while women focus on doing housework and taking care of children. With this family labour division, when a man and a woman got married, they could focus on their own work so the benefit of forming a marriage relationship could be maximized. However, more women take part in the labour market nowadays. At the same time, doing housework and taking care of children are still seen as their responsibilities, which means that women are required to take the responsibility in both working outside and taking care of their families at home (Goldscheider & Waite, Citation1986). In Song and Li’s article, it also mentioned that women could not escape from their domestic responsibility which was taking care of family although they could have more opportunity in participating labour force and have an increasing power in earning money (Song & Ji, Citation2020). Therefore, women could not see any benefit from a marriage relationship and hence, they are less willing to get married.

From the literature review above, most research articles studied the influences of the factors on marriage rate including development of economic level, social liberalization, cost of marriage, social constraint, education level and division of labour. It is seen that these factors directly influence the marriage behaviour of young generation. However, these factors may not show all the impacts on marriage behaviour potentially and there are still some existing potential factors that have not been included and discussed yet. One of the potential factors is the attitude toward marriage relationship among the young generation nowadays due to their parents’ influences. Xiong et al., (Citation2022) found that parental conflict has a negative effect on children’s attitude towards marriage, which is partly due to the poor parent-child relationship. The impact of parental divorce on children’s marital attitude depends on the severity degree of parental conflict (Xiong et al., Citation2022). The reason why parents could have large impact on their children’s marital decision is that Chinese parents have always been playing an important role in their children’s life. It is well-known that filial piety is one of the most important traditional thoughts in Confucianism. Children were taught to respect their parents and had to obey to what their parents said (L. Liang & Zhou, Citation2010). Filial piety is still widely accepted among adult children nowadays.

Although China shares some features with western countries such as modern and individualized family model, a strong family ties is still a main traditional characteristic in modern China and hence, the suggestions on family and marriage from the last generation is very important (Song & Ji, Citation2020). A study showed that in Mainland China, the perception and acceptance of filial piety among adult children range a score from 3.18–4.86, which based on 5-point scale with a total range of 1–5 (Dong & Xu, Citation2016). Under the idea of filial duty, parents had a high status in children’s mind. Suggestions given by parents may become the guide to children. Comparing urban areas with rural areas, the average marriage age in urban areas is 25-year-old in 2010 while 23-year-old in rural areas (Lu & Wang, Citation2014). This may be due to the difference in parents’ attitude toward marriage as the parents in rural areas may have a traditional and conservative attitude while the parents in urban areas are more open toward marriage. Parents’ behaviours or suggestions may affect children’s decision of marriage especially on the young generation born after the one child policy. Compare with the last generation, most of families nowadays only have one child due to the family planning policy and hence, parents may pay more attention to the growing process of the young generation. Considering the last generation who have many brothers and sisters in their families, their parents might only provide basic living guarantee for their requirements, and did not pay special attention to their studies or career development. While for the young generation, their parents expect them to have achievements in their studies and careers, and have higher requirements and expectations for their partners. Parents may talk about the value of marriage with their children and even instil their own attitudes and ideas about marriage in their children. Therefore, family factors have a great influence on the young generation’s marital decision. In this paper, a study on the influence of parents on children’s marital decision using the multiple linear regression and the logistic regression models is carried out where the influences of parents’ education level, financial support and their own attitude towards marriage relationship are discussed in detail. It is aimed to explore how parents’ external conditions affect their children’s attitude toward marriage and how parents’ own attitude toward marriage affects their children’s choices indirectly.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data

The data of China Family Panel Survey (CFPS) in 2018 is used in this paper. China Family Panel Survey is a national biannual longitudinal dataset that aims to reflect the changes of China’s society, economy, population, education, family relations, family dynamics and health by tracking and collecting data at the three levels of individual, family and community, so as to provide a data basis for academic research and public policy analysis. The CFPS data sample covers 25 regions in provinces, cities and autonomous levels. The target sample size is 16,000 households, and the respondents include all family members in the sample households (CFPS, Citationn.d.).

The CFPS questionnaire in 2018 was separated into four parts: personal information survey, family relation survey, family economic status survey and cross year core variable dataset respectively. The dataset for questions “how much financial support received from parents per month in the past three months” and “what is the expected marriage age” in the personal information survey, “what is the highest degree you obtained”, “what is the highest education your parents completed”, “what is your marriage status” and “what is your parents” marriage status’ in the family relation survey and “how many years of education you received” in the cross year core variable dataset are used in this study (CFPS Questionnaire, Citation2018). We first merged the three surveys mentioned above into one dataset and obtained an initial data containing 172,421 objectives and 46 variables. After cleaning NA data and the data with no meaning, and reclassifying all the variables, there were totally 3453 objectives with 8 variables remained.

The present study aims to find the relation between children marital decision and parents’ influences. Hence, the dependent variables are children’s marriage status and children’s expected marriage age, and the independent variables are years of education parents received, financial support from parents, parents’ marriage status, children’s age, children’s sex, and years of education children received. To define the independent variable parents’ financial support, the mean value of financial supports from father and mother is used. To define the independent variable years of education parents received and years of education children received, the original data is separated in to 8 levels that represent illiteracy to doctoral education separately. The details of reclassification are shown in Table .

Table 1. Reclassification of number of years of education received, China, 2018

For dependent variable parents’ marriage status, the data is also reclassified into 5 levels that represent unmarried, married, cohabitation, divorce and widowed separately. The variables used in this paper are described in Table .

Table 2. Explanation and statistics of selected variables, China, 2018

From Table , it shows that the sample data has an average sex ratio, and the range of the age is in 16–48 where the mean value is 19.4 which indicates that most of objectives are among the generation who were born after the one child policy and the reform and opening-up policy. The mean value of children’s marriage status is 0.37 which means that most of the objectives are unmarried while the mean value of the parents’ marriage status is 0.99 which indicates that most of their parents are married or cohabitation. The mean value of years of education parents received and years of education children received are both around 9 years which shows that most of both parents and children receive middle school education.

3.2. Methodology

Two methods used in this paper are the multiple linear regression model and the logistic regression model. The multiple linear regression is used to test how the independent variables, including children’s age, children’s sex, years of education children received, years of education parents received, parents’ financial support and parents’ marriage status, affect the dependent variable children’s expected marriage age. The equation to explain the relation of variables is established as follow:

where Y is the predicted value of children’s expected marriage age, β0 is y-intercept, X1 is children’s age, X2 is children’s sex, X3 is years of education children received, X4 is years of education parents received, X5 is parents’ financial support, X6 is parents’ marriage status, β1—β6 are the regression coefficients and ε is the model error (Sheather, Citation2009).

For the dependent variable children’s marriage status as a dummy variable, the method of logistic regression is used. Let y be the dependent variable and p(y = 1|X) = pi be the probability of children who have got married and (1-pi) be the probability of children who have not got married. Then the logistic regression model can be established as follow:

where α is a constant, k (1 ≤ k ≤ 6) is the number of independent variables and β is the coefficient of independent variables (Yu, Citation2017).

After analysing the overall situation of children’s expected marriage age and children’s marriage status using the linear regression and logistic regression respectively, analysis for male and female groups is then carried out separately using logistic regression to see whether there is any difference for different genders.

4. Result

4.1. Distribution of children’s expected marriage age

To have an overview on children’s expected marriage age, we first illustrate the distribution of the age in Figure where we can see that most of the young generation were willing to get married at age between 24 to 28 in 2018 and the mean value of expected marriage age was 26.37 which showed that young people nowadays were still willing to get married at a suitable or prime marriage age. However, from data of actual marriage age in 2005–2012, the largest proportion who got married was the young generation of age 20–24. The proportion continued to decrease from 47% in 2005 to 35.5% in 2012, and further down to 18.6% in 2020. At the same time, the percentage of people married at age above 30 increased significantly in 2020 (Premier Business, Citation2021). It is seen that more and more young generation choose to get married at a later age.

4.2. Influence of family factors on children’s expected marriage age

To investigate the influence of family factors on children’s expected marriage age, we have put the analytical results of using multiple linear regression into Table where we can see from the significant level p that the results for variables children’s sex and parents’ marriage status have no significance by using the linear regression with the dependent variable. Therefore, we will focus on analysing the results of other four independent variables in the following.

Table 3. Influence of family factors on children’s expected marriage age, China, 2018

From Table , we can see that the independent variables including children’s age, years of education children received, years of education parents received are positively related to the dependent variable children’s expected marriage age, which means that children with older age, with more years of education or with parents having more years of education intend to have a late marriage, while the variable parents’ financial support has a negative regression coefficient, which shows that children received less financial support from their parents tend to get married late but its influence could be ignored as the absolute value of the coefficient is very small. There have been some studies also addressed on the impact of education level on marriage decision. One of the studies found that one more year of education would reduce the likelihood of marriage before the age of 18 by 1.7% and raise the age at first marriage by 0.734 year after the implementation of Compulsory Schooling Laws in 1986, which indicates that with more years of education received, a person would get first marriage at a later age (Y. H. Liang & Yu, Citation2022). The reason that people with higher education level tend to get married late is because most young generation nowadays prefer to get married after they finish their education in universities (Liu & Liu, Citation2018). Among these variables related to family factors, years of education parents received has the strongest influence on children’s expected marriage age.

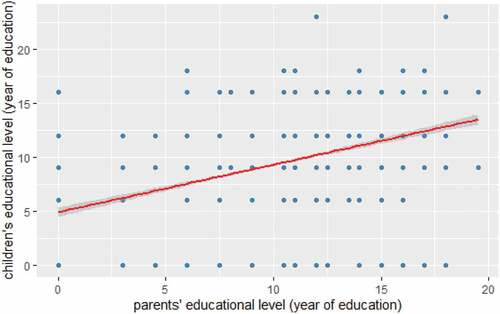

Why the parents who have more years of education have strong influence on children’s expected marriage age may be because that they hope their children also to have more education potentially. It was mentioned in an article that parents with higher education level would pay more attention to children’s academic achievement and hence to nurture an outstanding child Liu, Citation2010. To see the relation between children’s education level and parents’ education level, we made a further analysis using the linear regression based on the same data and the results are shown in Figure and Table . It is clearly seen that there is an obvious positive relation between parents’ and children’s education levels. Parents having a higher education level lead their children to have a higher education at the same time and consequently a late expected marriage age.

Table 4. Influence of years of education parents received on years of education children received, China, 2018

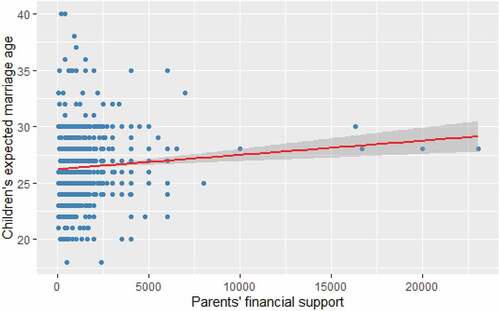

With respect to parents’ financial support, the value of its regression coefficient is only −0.0001 although it has a high significant level. This indicates that the influence of financial support from parents on children’s expected marriage age could be ignored. We further looked at its distribution plotted in Figure and the result of linear regression of the relation between two variables shown in Figure and found that most of the financial support received from parents were under 5000. It was thought that the small regression coefficient might be caused by some extreme values in the data. Therefore, a further investigation was carried out by separating the data into two groups: one group (group 1) with the financial support less than or equal to 5000 while the other group (group 2) more than 5000. The results of linear regression for the two groups are illustrated in Table where we can see that the first group has a positive coefficient still with a value that almost equals to 0 while the p level for the second group shows that the result for the second group has no significance. The results further prove that the influence of the financial support received from parents on their children’s expected marriage age can be ignored. However, parents’ socioeconomic status could be a factor that affect children’s marital decision indirectly, as it was found by Kong (Citation2019) that parents’ economic status and social resources including family social relations, family education mode, and the information and the assistance provided by parents and their social relations have important impacts on the opportunity for children to get a high-quality and decent education, and consequently affect children’s marriage decisions.

Table 5. Influence of parent’s financial support on children’s expected marriage age, China, 2018

4.3. Influence of family factors on children’s actual marriage status

Logistic regression is used to study how the children’s actual marriage status is influenced by children’s age, children’s sex, years of education parents received, years of education children received, parents’ financial support and parents’ marriage status. The results are shown in Table .

Table 6. Influence of family factors on children’s actual marriage status, China, 2018

The results show that children’s sex, years of education parents received, and years of education children received have a high significant level and are negatively related to children’s marriage status, which means that male objectives and the objectives who have received or whose parents have received longer education tend to not get married. The regression result for parents’ marriage status has no significance. Again, parents’ financial support does not show a significant effect on children’s marital decision.

It is interesting to note that on contrary to the linear regression children’s age has no significance in this logistic regression, while children’s sex becomes an independent variable with a high significant level. Hence a further investigation to see the difference influence between the two genders was conducted based on the same data and the result is shown in Table .

Table 7. Difference influence between male and female on children’s actual marriage status, China, 2018

It is seen from Table that three independent variables including children’s age, years of education children received and parents’ marriage status have obvious different influences for different genders. Female with older age is more likely to get married while male is the opposite. This may be because female is more afraid of being considered as an “old leftover woman” (female aged around 30 and still unmarried) and feels anxiety with this situation (Qian & Qian, Citation2014). While for male, 30-year-old is the “golden age” and they have less pressure on getting married from their parents and also society.

Regarding to education level, female with higher education level is less popular in marriage relationship. It is common in China that female usually marries a male with better income or higher education level than herself. According to a statistic, the marital satisfaction in a marriage is higher if husband has a higher education level than wife’s and vice versa Wang & Li, (Citation2021). Female with a high education level is more difficult to find a satisfied husband compared with male with a high education level.

Parents’ marriage status also has different effect on different gender. Children growing up in a single parent family usually lack a sense of security, where female of these children is less confident in a marriage or has a negative attitude toward a marriage and hence, is more unwilling to get married. On the contrary, an unhappy family will stimulate males’ rebel psychology to leave from their original families and built their own families with their partners (H. Q. Zhang, Citation2012).

5. Conclusion

Low marriage rate in China has become an aggravating problem nowadays and it has been attracted widespread attention in China. From the existing studies, is has been found that the reasons behind the low marriage rate is related to the factors including economic development, social liberalization, education level, and so on. However, family factors especially parents’ influence has not been discussed thoroughly. This paper addresses how parents’ external conditions affect their children’s attitude toward a marriage relationship and how parents’ own attitudes toward a marriage relationship affect their children’s marriage choices indirectly. Methods of multiple linear regression and logistic regression are used for the purpose based on the data of China Family Panel Survey (CFPS) 2018. The influences of parents’ education level, parents’ marriage status, parents’ financial support and some other related factors on children’s expected marriage age and children’s marriage status are studied. The following conclusions are drawn.

Parents with a high education level are more likely to encourage their children to obtain a high education degree which weakens their children’s willingness to get married and results in a late expected marriage age and the influence on their son’s marital decision is more than their daughter’s. Parents’ marriage status has different influences on their sons and daughters. An unhappy marriage relationship of parents has an effect of stimulating their sons to get married, but it has no significance on daughters’ marriage willingness. Parents’ financial support does not show a significant influence on children’s marriage decision. Among the three family factors, parents’ education level is the factor that affects their children’s marital decision the most.

This study might be limited by the methods used or the data referred. Nevertheless, it is hoped that the findings in this study may provide valuable information to have better understanding of young generation for their marriage attitude.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bullough, V. L., & Ruan, F. (1994). Marriage, divorce, and sexual relations in contemporary China. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 25(3), 383–13. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.25.3.383

- CFPS. (n.d.). China Family Panel Survey. www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/

- CFPS Questionnaire. (2018). China Family Panel Survey 2018 summary questionnaire [Data set]. Institute of Social Science Survey, Peking University.

- Cui, X. L. (2011). A brief analysis of the love and marriage problems about the older higher unmarried intellectual women. Northwest Population Journal, 5(32), 58–62—. https://doi.org/10.15884/j.cnki.1007-0672.2011.05.012

- Dong, X., & Xu, Y. (2016). Filial piety among global chinese adult children: A systematic review. Journal of Social Science, 2(1), 46–55.

- Goldscheider, F. K., & Waite, L. J. (1986). Sex differences in the entry into marriage. American Journal of Sociology, 92(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1086/228464

- Jiang, Q. B., Feldman, M. W., & Li, S. Z. (2014). Marriage squeeze, never-married proportion, and mean age at first marriage in China. Population Research and Policy Review, 33(2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9283-8

- Kong, Y. Y. (2019) A study on the influence of social capital on access to higher education [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Xi’an International Studies University.

- Liang, Z. T. (2014, March). “A difficult journey: From “one-child policy” to “daughter-headed household. KAIFANGSHIDAI. http://www.opentimes.cn/abstract/1951.html

- Liang, J. Z., Ren, Z. P., Huang, W. Z., He, Y. F., Yu, J., & Bao, D. (2022). China marriage and family report 2022 edition. Yuwa population research. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1728509638649788550&wfr=spider&for=pc

- Liang, Y. H., & Yu, S. (2022). Does education help combat early marriage? The effect of compulsory schooling laws in China. Applied Economics, 54(55), 6361–6379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2022.2061906

- Liang, L., & Zhou, Z. (2010). Filial piety in traditional chinese relationship of father and son. Journal of Longyan University, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.16813/j.cnki.cn35-1286/g4.2010.03.018

- Liu, Y. (2010). The influence of parents’ education level on their children: An empirical analysis of primary school students’ families in five western provinces. Proceedings of China Educational Economics Academic Annual Meeting.

- Liu, B. F., & Liu, Y. (2018). Does higher education enrolment expansion really reduce the marriage rate in China? New evidence from synthetic control method. Journal of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.16538/j.cnki.jsufe.2018.03.007

- Lu, J., & Wang, X. (2014). Analysing China’s population: Social change in new demographic era. In I. Attane & B. C. Gu (Eds.), Changing patterns of marriage and divorce in today’s China (pp. 37–50). Springer.

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the China. (2021). Civil affairs statistic in the fourth quarter of 2021. https://www.mca.gov.cn/article/sj/tjjb/2021/202104qgsj.html

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). China population census year book - 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/zk/indexch.htm

- Premier Business. (2021, December 23). The marriage age of Chinese youth has been postponed: The proportion of 30-34 years old has increased significantly. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1719911770833734339&wfr=spider&for=pc

- Qian, Y., & Qian, Z. C. (2014). The gender divide in urban China: Singlehood and assortative mating by age and education. Demographic Research, 31(45), 1337–1364. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.45

- Sheather, S. J. (2009). A modern approach to regression with R. Springer.

- Song, J., & Ji, Y. C. (2020). Complexity of Chinese family life: Individualism, familism, and gender. The China Review, 20(2), 1–17.

- Statista. (2022). Marriage rate in China from 2001 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1055659/china-marriage-rate/

- Su, L., Liang, C., Yang, X., & Liu, Y. (2018). Influence factors analysis of provincial divorce rate spatial distribution in China. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Science, 2018, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6903845

- Wang, J., & Li, Y. J. (2021). Educational marriage matching and marriage satisfaction. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2021(2), 52–63.

- Xiong, M. R., Liu, Q., & Fu, Y. (2022). The influence of interparental conflict on emerging adults’ marital attitude: Parent-child relationship as a mediator and the additional impact of family structure. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 030(4), 830–836.

- Yu, Z. L. (2017). Influence of intergenerational support on the life satisfaction of the elderly and differences between urban and rural areas: Based on analysis of 7669 samples from CHARLS. Journal of Hunan Agricultural University, 18(1), 062–069. https://doi.org/10.13331/j.cnki.jhauss.2017.01.010

- Zhang, H. Q. (2012). Negative influence of single parent family on children’s psychology and related countermeasures. Technology Information, 24, 69–70. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.1001-9960.2012.24.053

- Zhang, J. (2017). The evolution of China’s one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.141