Abstract

In 2020, the freedom of religions in Indonesia reached lowest point which accounts for the score of 1 out of 4. This decreasing trend is in line with some intolerance cases as happened recently. Intolerant groups are often linked with fundamentalism or scriptural Islamic groups taking their movements in the form of persecution, oppression, violence provoked by religion and tribe. The issue is inextricable from how this violence is triggered by anti-tolerant ideology living amidst the society within the state and the politics of Indonesia. This research was conducted in 38 regencies/municipalities in East Java Province, Indonesia. The methods employed in the research involve survey based on descriptive-quantitative approach. The survey adopted religious tolerance measurements developed by Broer et al. The research reveals that Religious Tolerance Index in East Java is considered good. However, religious conviction scored low, with the average score of 62.1. It becomes one of the contributing factors on the intolerance towards minority groups. Furthermore, religious conviction is deemed to be quite strong to determine the level of conservatism in the society to treat their social life.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Religion is considered to have a central role in Indonesian society. This is influenced by the specific cultural, social, and political background in each region. Although religion is considered to determine the morality of society, social conflicts are also often caused by religion. Social conflicts with religious backgrounds can be quelled with tolerance in society. The more tolerant society, the freedom of others to practice their religious beliefs can also be maintained. This study states, Religious Tolerance Index in East Java is considered good. It becomes one of the contributing factors on the freedom towards minority groups. However, high level of belief in one’s own religion (religious conviction) encourages intolerance to the beliefs of others. This also could be internal factor that detains tolerant society in East Java, Indonesia.

1. Introduction

Religion has broad relevance in the context of the social dimension. It cannot be separated from the fact that religion has become something in tandem with human daily activities. Religion certainly has functions that useful in human life that can be used to solve daily problems and integrate the society (Burg van der & Been, Citation2020; Hakim, Citation2021). However, E.K. Nottingham (Nottingham, Citation1985) argues religion could possibly disintegrate society.

Intolerance actions, either in persecution or any form of violation sparked by religion-related issues in Indonesia, have been in the spotlight (Harsono, Citation2020). This issue is inextricable from how this violence brings along the anti-tolerance ideology across peoples within the scope of politics and the state (Abdulla, Citation2018). Setara Institute (Citation2020) reports that there has been a rising trend in intolerance and discrimination against religious minority groups since 2019.

According to Freedom House (Citation2020) Report concerning Plummeting Democracy Index in Indonesia, the freedom of religion aspect only gains 1 out of 4. This decreasing trend is in line with intolerance issues growing in the society (Aspinall & Warburton, Citation2017; Hadiz, Citation2017; Liddle & Mujani, Citation2013; Mietzner & Muhtadi, Citation2018; Zaduqisti, E., Mashuri, A., Zuhri, A., Haryati, T. A., & Ula, M., Citation2020).

The government’s role in keeping an eye on tolerance (Bagir et al., Citation2020). It is governed in Law Number 1/PNPS of 1965 concerning Prevention of Abuse of Religion and/or Blasphemy and Law Number 40 of 2008 concerning Abolishment of Race and Ethnic Discrimination. Surabaya, one of the cities in East Java, was at the score of 9 as a tolerant city according to Setara Institute in 2018 (Setara Institute, Citation2018). The Province of East Java declared the Regional Regulation Number 8 of 2018 concerning Tolerance as the response to criminal terrorism taking place in Surabaya, Indonesia, back in 2018.

Intolerance groups are often associated with fundamentalism or scriptural Islamic groups (Bruinessen van, Citation2013; Zulkifli, Citation2013), while traditionalists, which are often linked with the organization of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), are positioned in an organization that frequently promotes tolerance. East Java is known for its huge followers of NU in Indonesia although rarely is the NU itself the focus of analysis by clerics regarding sectarianism (Mietzner & Muhtadi, Citation2020). This is partly because cumulative measures have been taken to promote the idea implying that NU embraces religious pluralism and tolerance to other religions.

This study involved surveys conducted in 38 regencies/municipalities in the East Java Province, Indonesia, in 2020. Religion-based tolerance referred to Religious Tolerance Index—RTI introduced by Broer (Broer et al., Citation2014). Tolerance index is based on seven indicators: (a) minimization of religious differences, (b) inclusivity, (c) exclusivity and self-centeredness, (d) openness for change, (e) faith and respect for others, (f) religious conviction, and (g) recognizing the freedom of others. The analysis of this study is focused on the indicator of religious conviction and the freedom of religions of others.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Survey instrument development

The research used Religious Tolerance Measurements introduced by Broer et al. (Citation2014) consisting of (a) minimization of religious differences, (b) inclusivity, (c) exclusivity and self-centeredness, (d) openness for change, (e) faith and respect for others, (f) religious conviction, and (g) recognizing the freedom of others. Each indicator contains some validation phase of the questionnaire for measuring religious tolerance (see Table ).

Table 1. Instrument and its validating questionnaire on religious tolerance by Broer et al. (Citation2014)

Index scores are obtained based on the above instrument. To quantify the attitude tendency, Likert scale (1–5) was employed to score each answer to each question. In terms of statement of attitude, scoring was given to favorable question that leaned towards tolerant behavior with the score relevant to the statement offered to respondents. Each answer to every question was converted by means of scoring: the total score was divided by maximum score in each item of indicator. The final score of index was calculated based on the accumulation of scores of each indicator. The following is how the score of tolerance index is calculated:

The gained score led further to the division of four categories: bad, fair, good, and excellent. Nineteen questions gained the lowest score of 1 and the highest score of 5. The categories of tolerance index from bad to excellent accounted for the range of 19 to 95, and the length of class represented 19. Specifically, the range of scores are shown in Table .

Table 2. The range of scores on categories of tolerance index

The test involves measurement, validity, and reliability. The validity test consists of content, construct, and criterion-related validity. This study employed content validity test. This test was performed based on expert’s judgment concerning congruence between questions and indicators measured.

Cronbach Alpha test was employed to find out the reliability level. Calculation was performed in this study to find out the correlation coefficient by means of biserial or point-biserial test, in which the latter is an alternative to correlative coefficient test of total items. The criteria involved in this study are given as follows:

scale is reliable if Cronbach Alpha coefficient score ≥0.60

an item is good if the score of biserial correlation of total items shows r ≥ 0.30.

Research data were conducted in East Java, Indonesia, that involved respondents who were 15 years old and over. Research sample was calculated based on Slovin formula with tolerance level of 5%:

n = number of samples

N = number of population

e = tolerable error (%)

2.2. Limitations

There are some limitations that contributed to this research, namely:

The research conducted in East Java Province covering 29 regencies and 9 cities.

There are seven instruments of Religious Tolerance Measurements introduced by Broer et al. (Citation2014). However, this research only used two instruments, namely religious conviction and recognizing the freedom of others.

The respondents only be categorized by age, location, gender, and belief.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Indonesia tolerance post-soeharto

Some attitudes, however, are shaped or explained in terms of people’s religious beliefs (Skitka et al., Citation2018). Indonesia placed as the most religious in the world and believed that religious will guide to good morality (Tamir, C, et al, Citation2020). In fact, tolerance in Indonesia is only considered a myth even though it is supported by the “most tolerant” organizations such as Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah (Mietzner & Muhtadi, Citation2020).

The term “religious tolerance” is a controversial, subjective, normatively loaded term (Kadt, Citation2017; Hoon, Citation2017) and can be arranged in different ways (Walzer, Citation1997). It can be applied to many different sorts of things such as religious, cultural, and different patterns of behavior. Cohen (Citation2004) put tolerance in the term of toleration. An act of toleration is an agent’s intentional and principled refraining from interfering with an opposed other in situations of diversity, where the agent believes she has the power to interfere, whereas tolerance always negates intolerance. Mietzner and Muhtadi (Citation2020) defined intolerance as an attitude that rejects, bans or limits, the expression of beliefs and/or the practices of citizens endorsing a faith different from one’s own, and that views the constitutional rights of followers of one’s own faith as superior to those held by followers of a different faith.

Many studies put tolerance in the term of radicalism (Lovita, Citation2017; Wahid, A., Rakhmawati, F., & Destrity, N., Citation2020), freedom (Setara Institute, Citation2020), and equated with social piety (Hakim et al., Citation2021). Some scholars also stated that tolerance sometimes in accordance with religious conflicts (Saiful Mujani, Citation2019). Setara Institute (2011, 2012) uses the term intolerance in two forms: passive and active intolerance. Passive intolerance is closer to the term puritan, which focuses more on the view that claims that the own beliefs are the most true while others are not. In passive intolerance, the expression of disapproval is not indicated by acts of violence. Meanwhile, active intolerance is a step more expressive than passive intolerance.

Religious tenets, convictions, attitudes, and behaviours of people that contradict one’s own deepest religious convictions are not easily tolerated, and are often seen as a threat (Walt, Citation2014). This statement revealed by Mietzner and Muhtadi (Citation2020) as a myth. This is based on a number of conflicts that occurred in Indonesia, especially in post-Soeharto regime after 1998.

Although known as a country that promotes tolerance, several cases of intolerance such as terrorism and persecution often occur in Indonesia (Hakim et al., Citation2021; International Crisis Group, Citation2012; Setara Institute, Citation2020). In the context of Indonesia, the diversity of ethnics, languages and religions has made any effort to develop a national unity a difficult task (Rachman, Citation2017). The Ambon and Poso conflicts (1998–1999), the Bali-JW Marriot bombings by Jemaah Islamiyah (2002–2003), to the suicide bombings at a number of churches in Sulawesi and East Java that happened in 2018,) are a number of records of intolerance in Indonesia. This seems rise to a paradoxical condition between Indonesia as a tolerant country. This study specifically draws on an approach of the religious conviction and recognizing the freedom of others by Broer et al. (Citation2014).

3.2. Demography of respondents

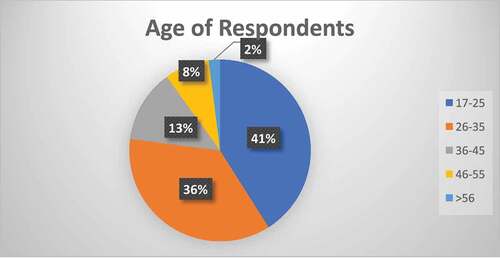

Respondents were sampled based on age, location, gender, and belief. The average age of the respondents was 30 years old. Based on Figure below, the majority of the respondents (41%) were between 17 and 25 of the total respondents. The age group of 26–35 represented the second biggest number of respondents (36%), followed by 36–45, 46–55, and over 56 accounting for 13%, 8%, and 2%, respectively.

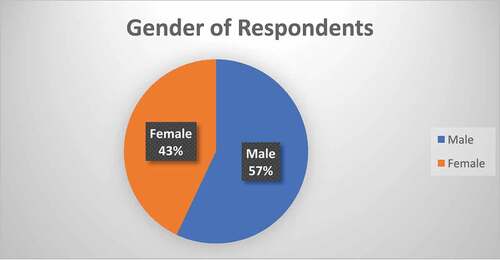

Figure shows most respondents were males, accounting for 57% or 231 respondents, while the females accounted for 36% or 171 respondents. The distribution of the respondents according to gender was uncontrollable since sampling relied on whoever was available to respond to the questionnaire.

All the respondents represent all the regencies/municipalities in East Java Province, Indonesia, with varied numbers. These different figures are based on the proportion of the population of The Regional Coordinator Agency (Bakorwil) in each region in East Java, Indonesia. In reference to the survey data, the majority of respondents were from Surabaya city, the Regency of Malang, the Regency of Sidoarjo, and the Regency of Jember. There were 20 respondents representing these four regions with the highest population in the province. Other regions, however, only contributed 2–17 respondents.

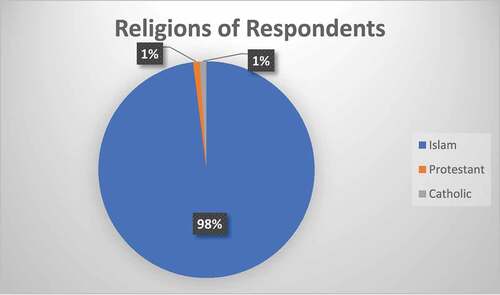

This survey recorded that the majority of the respondents were Muslim as seen in Figure , accounting for 98%, while other religions like Catholic and Christian represented lower than 1%. The survey, however, did not recorded beliefs other than the common religions in Indonesia. This number is not much different from the data compiled by the Government through the Ministry of Home Affairs in 2021.

3.3. The instrument of religious conviction

This indicator consists of four items (Q7, Q15, Q16, Q20), each representing religious values, moral belief, religious attitude, and internalization of belief. According to the total score gained in this indicator, religious conviction scored 63.4 in the survey in East Java Indonesia in 2020 (Broer et al., Citation2014) argues that religious doctrines, beliefs, and the attitudes of individuals that contravene the deepest religious conviction are not easily tolerated and mostly seen as a threat.

As seen, the median of the four items in the indicator is 3. Religious value (Q7) scored 62.1 points, moral belief (Q15) scored 52.9 points, religious attitude (Q16) scored 66 points, and internalization of belief (Q20) scored 72.3 points, each of which is explained in the following:

In Q7 displaying personal value indicates that people hold on to as their way of life, in which the majority of the respondents showed 50–50 agreement. There were 29.4% of respondents claiming that the position displayed in Q7 represented what they did, but they saw it as an ordinary matter. Furthermore, there were 22.6% of respondents who agreed and 15.9% who strongly agreed, while 20.6% and 11.4% of the respondents disagreed and strongly disagreed respectively. Based on these figures, the majority of the respondents represent the group firmly holding on to their religious belief as their way of life. The data also indicate that most respondents firmly held on to their own belief, and they preferred to act based on the religion they followed. The respondents disagreeing with the statement (31%) welcomed universal values to hold on to. This condition allows more open dialogue that gives access to the adoption of values outside personal perspectives and religion as references people could use to live their social life.

In Q15, four statements were available for the respondents, where they were required to pick two of the four statements: (1) I am aware I have low moral belief; (2) I think people have rights to follow their belief no matter how wrong it might be; (3) I firmly hold on to my own belief; (4) I believe in those who are united by a set of shared values. The combination of responses of the four statements are presented in the following table:

On the contrary, those strongly believing that they have relatively strong morality fundamental in religion also believe that this strong fundamental serves as the core on to which the religious values-based unity of the people holds. At this point, there is potential that people may rely on their own perspective to see people of other religions. That is, the intolerance to others may result from different moral values adhering to other groups of people. The category representing this group is quite high, accounting for 40% according to the statements 1 and 2 coming from the respondents.

In another group picking statement 3, there were 39.6 respondents believing that people have their rights to follow their own belief no matter how wrong it might be. Moreover, they also believe in people united by a set of shared values. This group of respondents is categorized as moderate group trying to see others in the basis of different beliefs.

Furthermore, Q16 consists of four statements picked by respondents:

I believe that my religion is the most righteous and others are wrong.

I believe that all religions teach some righteousness but changes should also be taken into account in other religions to allow them to see righteousness in the same way as my religion.

I believe all religions head to the only God; and those religions are seen different only due to different conditions.

I have no problem with genuine dialogue involving other religions since I believe my own religion, and others can understand each other, and this understanding grows along with experience.

Based on the survey, the majority of the respondents (39.1%) responded to statement number 3, and statement number 4 was picked by 23.9% of respondents. Statement number 1 was picked by 22.6%, and number 2 was picked by 14.4% of respondents. From these figures, it is obvious that respondents that went with statement numbers 1 and 2 were categorized as an exclusive group that is likely to be intolerant since this group believes the only faith it follows (statement one) and it is also deemed to be inclusive since the people in it force others of different religions to believe what they believe (statement number two), and this group represents 35%. In the second category, it can be seen that this category represents more tolerant group (statement number three and four). This tolerance departs from religious and dialogical pluralist (Broer et al., Citation2014). Despite different beliefs, this group believes that different religious views are a matter of different places. Moreover, this group also employs dialogical approach that involves followers of other religions.

In Q20, religious conviction indicator sees how internalization of religious belief followed by respondents is related with others. The following four statements were picked by respondents:

I am firmly attached to a religion I believe has strong fundamentals. All that are performed in places of worship such as churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, or religious organizations are deemed to be dogma or doctrine, and, thus, it is not easy for me to interact any further with those not following the same belief or religion as mine. I have to think within the scope of my religion since there is no way I could understand others’ religions. I am sure they could not understand my religion either.

I belong to no religion or no religious organizations or institutions. I see myself as an unreligious person. I respect what people think without my judging their thoughts.

I am not involved in an organized religion, but I still see myself as a religious person since I try to build a spiritual connection with divine world above me that leads me onto its path. I believe every human being is searching for his/her spiritual belief which his/her life clings on to; some search for spirituality through some other religions, but some others see institutionalized religions as a hindrance hampering their quest.

I belong to one of religious groups as in churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, or religious organizations, and although we worship according to particular dogma and confession documents, we feel that we can freely interact with others discussing religion-related matters and differences existing between us. Although I am aware that I am following a religion that others do not, I treat others with respect.

Based on the survey data, the most respondents went with the fourth statement, accounting for 48.3%. The second statement was picked by 21.9%, first statement 18.4%, and third statement 11.4% of respondents. Response to the first statement indicates that religion-based intolerance arises because of the idea that two different religious beliefs or more cannot unite. Responses to statements 2 and 3 indicate that there is tolerance to others following different religious beliefs. Statement four highlights respondents with moderate perspective, where they expect to live a peaceful life and believe that differences can be negotiated. Within this group, the majority of respondents represent tolerant category with moderate perspective towards others following other religions.

The results of the normality and homogeneity tests (assumption tests which are a requirement to perform parametric tests) do not indicate that the data are normally distributed. Thus, different tests in this study used a non-parametric test. The non-parametric difference test is the Mann–Whitney test. The Mann–Whitney test can be performed if it is homogeneous. The test that is suitable for use in data that is not normally distributed is the Levene Test. Homogeneous test conditions are met is the significance value > 0.05.

Based on the results of the Mann–Whitney test above, the statistical test results showed a score of 0.352 (Asymp. Sig (2-tailed)). This also shows that there is no significant difference between men and women in obtaining religious conviction scores. The test results can be said to have a significant difference if the significance value is below 0.05.

3.4. Recognizing the freedom of others

Data collected from five regions in East Jawa, Indonesia as summarized in table . The indicator consists of four statements (Q8, Q9, Q17, and Q19), and each of which comprises social relation of daily values, universal values, freedom of religions and thoughts, and freedom of peaceful life. The recognition of the freedom of others to follow a religion serves as one of the measures how tolerance is working in a certain group of people. Without such recognition, coercion and repression will surely snatch people’s rights.

Table 3. Regions of respondents in religious tolerance survey in East Java Province, Indonesia, 2020

In reference to Table , indicator of recognizing the freedom of others scored 79.4 points in total. This score was derived from Q8 accounting for 79.5 points, Q9 for 75.4 points, Q17 for 74.2 points, and Q19 for 88.7 points. Each of the items in the indicator is respondents’ perspective towards religious values in table , moral values in table , religious attitudes in table , and internalization of religious belief in table .

Table 4. Respondents’ perspective towards religious values

Table 5. Respondents’ perspective towards moral values

Table 6. Combinations of responses concerning four statements

Table 7. Statement regarding religious attitudes of respondents

Table 8. Respondents’ attitude towards internalization of religious belief

Table 9. Indicator of recognizing the freedom of others

Item Q8 as summarized in table consists of a statement concerning the agreement over general values not related to religions in day-to-day life. In reference to these data, the majority of the respondents strongly agreed (41.8%) and 30.8% agreed. There were 15.9% of the respondents seemingly agreeing with universal values and preferred to go with religious values for their day-to-day practices.

Table 10. Social relation and day-to-day practices

The data also imply that most of the respondents tended to be minimalist, where they tended to abide by general values that are formulated in a simple way and widely accepted. This group is more open to interaction with others based on the shared values accepted generally. The minority in this group (11.5%) indicates that people tend to prefer maximum values as formulated in religion and belief regarding their own perspectives. The disagreement of the respondents with this statement indicates that people are more aware of their own religion. Their life and perspective follow the system of religious values others rely on, in which the value system may be derived from different religions.

In reference to Table , high level of agreement is obvious, where there were 34.8% of the respondents agreeing and 30.6% strongly agreeing the universal values as the basis of interaction with others. The rest goes to 20.6% of respondents accepting this attitude and 13.9% stating their disagreement with universal values implying that people leave their religions they have believed in.

Table 11. Universality of values believed by respondents

In Q17, respondents were given three statements representing their attitude to the freedom of religions and thoughts in social life. Based on table The statements involve:

I believe that what people determine is everyone’s freedom, and they are allowed to believe in whatever they think is relevant to them.

I believe that it is not always possible for people to follow their freedom, but they have to abide by the principles elaborated in a scripture like Quran. Perspectives of others are to be respected.

I believe that some people have to live their life and act in accordance with the values that are not entirely religious but appropriate, like behaving in a civilized manner, politely, wisely, pleasantly, or behave in a way that does not rebel.

Table 12. Freedom of religions and thoughts of the respondents

Of the three statements above, most respondents fell to the third statement, where 46.3% of the respondents agreed that people did not have to be entirely religious. This group highlights secular group with tolerance to others (Audi, Citation2000). Other respondents believed that the ideas of each individual are inseparable from scripture of every religion. However, they agreed that others’ beliefs have to be respected. This second group is categorized as a tolerant group firmly holding on to their religious belief, while the rest (23.4%) said that individual’s freedom forms a basis of social behavior. People of this last category tend to be more liberal and do not refer to consideration of specific religions or cultural values but more to the absolute freedom to believe in something.

In Q19 as mention in table above, respondents were given statements aimed to reveal their views about other’s freedom to live peacefully. The three statements involve:

I do not think people can live a peaceful life together since conflict often happens, and I think it is not easy for them to trust one another.

I think people have to find their way to live a peaceful life together; they have to trust others.

I believe that it is not impossible to live a peaceful life together among others of different religious beliefs as long as they respect one another and treat others with respect and dignity.

Table 13. Statement of freedom to live peacefully

The table above implies that the majority of the respondents, accounting for 74.4%, agreed that peace could grow amidst different religious beliefs. Peace can be established as long as people treat others with respect no matter what their beliefs are (Skitka et al., Citation2018). These respondents are categorized as a tolerant group that tends to refer to peace. These data also imply that there were 17.4% of respondents agreeing that belief is the foundation of peaceful life. This group of people can also be considered as tolerant, while 8.2% believed that they could not trust each other, and peace was hampered. The tendency like this can be said as intolerance since such people see others as suspicious individuals without any further efforts to settle conflict amidst the society (Mujani, Citation2019). From recognizing the freedom of others score based on gender, it can be seen that there are 231 males and 171 females with a mean of 3.12 (male) and 3.2 (female). To test for gender difference significance, the results of the Mann–Whitney U-test revealed that there is no significant difference in the scores for this item based on gender. This can be seen from the score of 0.513 (Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed)).

3.4 Discussion: Religious conviction based on regency

Religion takes a central role in society. Indonesian that often associated as tolerant cannot be separated from religion. The religiosity is considered to have a central role in determining life. This shows how important religion is in Indonesian society as mentioned in recent studies.

However, when looking at the survey results of the item religious conviction and recognition of the freedom of others, there are differences in each region. The region that received the lowest score in the category of religious belief was Pamekasan while the highest is Bojonegoro. In the section on recognizing the freedom of others, the Jember Region got the lowest score and Bojonegoro got the highest score. Following are the scores for each survey area:

The difference in the scores above cannot be separated from the regional context and culture in each region. Among the factors that drive the high and low scores are culture, politics, past conflicts, and the unique Islamic identity of each region. Although the Pamekasan region is considered to be very thick with Madurese Islamic culture, the strong Islamic values in Pamekasan Regency do not guarantee religious conviction. The cultural base of the Madurese community in the Pamekasan region is very high. Otherwise, religion-based conflicts are easier to trigger. As a result, the marginalization of other Muslim minorities can occur. This happened to the Shia Muslim community in Sampang who were expelled from their villages. In recognizing the freedom of others, the Bojonegoro area got the highest score with 0.843. Community life in the Bojonegoro region does have a strong coastal community tradition. Cultural differences in society have been going on for quite a long time. This is marked by the culture of coastal communities that have been built from long-standing trade. The open nature of society makes recognition of the freedom of belief of others easier to obtain. Conflicts with religious backgrounds in the Bojonegoro regional area have also never occurred.

4. Conclusion

Based on the results of the survey conducted in the Province of East Java Indonesia in 2020, Religious Tolerance Index is considered good. However, religious conviction scored low, with the average score of 62.1. This religion is believed to be one of the contributing factors of intolerance in minority group. At this point, religious conviction is deemed to be quite strong to determine the level of conservatism in the society to treat their social life. The survey also indicates that the indicator of minimization of religious differences scored the highest among the other indicators with the average score of 82.9. The low score as in the indicator of religious conviction leads to the recommendation implying that religious reflection not only works based on personal perspective but it should be brought further to the religiosity and piety at social level.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the manuscript. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muhammad Lukman Hakim

Muhammad Lukman Hakim is a lecturer in the department of government science, Universitas Brawijaya Malang. The study of innovation and regional development has become a major interest in studies in recent years. Currently, he is the Head of the Sociology Doctoral Study Program at Universitas Brawijaya. Therefore, studies related to local government have often been carried out in recent years.

Indah Dwi Qurbani

Indah Dwi Qurbani is a lecturer at the Department of Constitutional Law, Faculty of Law Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia. She has studied extensively on Regional Regulations in East Java and has also conducted research on radicalism in East Java in the last 3 years.

Abdul Wahid

Abdul Wahid is a lecturer at the Department of Communication Science, FISIP, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia. Some of the studies of interest are the history of the press, the Islamic movement and Media & Culture. Currently, he studies the issue of the Islamic movement in Indonesia. A number of works on media and social movements have been published in University journals and publishers. Currently, Abdul Wahid is active as Head of the Center for Media, Literacy and Culture Studies (Puska Melek) which is engaged in media literacy in Malang City.

References

- Abdulla, M. R. (2018). Culture, religion, and freedom of religion or belief. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 16(4), 102–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2018.1535033

- Aspinall, E., & Warburton, E. (2017). Indonesia: The dangers of democratic regression. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Social and Political Sciences (ICSPS). https://doi.org/10.2991/icsps-17.2018.1

- Audi, R. (2000). Religious commitment and secular reason. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164528

- Bagir, Z. A., Asfinawati, S., Arianingtyas, R., & Arianingtyas, R. (2020). Limitations to freedom of religion or belief in Indonesia: Norms and practices. Religion & Human Rights, 15(1–2), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1163/18710328-bja10003

- Broer, N. A., Muynck de, B., Potgieter, F. J., Wolhuter, C. C., & Walt van der, J. L. (2014). Measuring religious tolerance among final year education students: The birth of a questionnaire. International Journal for Religious Freedom, 7(1/2), 77–96.

- Bruinessen van, M. (2013). Contemporary developments in Indonesian Islam: Explaining the “Conservative Turn.”. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Burg van der, W., & Been, W. D. (2020). Social change and the accommodation of religious minorities in the Netherlands: New diversity and its implications for constitutional rights and principles. Journal of Law, Religion and State, 8(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1163/22124810-00801002

- Cohen, A. J. (2004). What Toleration is. Ethics, 115(1), 68–95. https://doi.org/10.1086/421982

- Freedom House. (2020). Freedom in The World 2020 Indonesia. https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia/freedom-world/2020

- Hadiz, V. R. (2017). Indonesia’s year of democratic setbacks: Towards a new phase of deepening illiberalism? Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 55(3), 261–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2017.1410311

- Hakim, M. L. (2021). Agama dan Perubahan Sosial. Media Nusa Creative.

- Hakim, M. L., Qurbani, I. D., & Wahid, A. (2021). Social religious changes of east java people in the index of tolerance analysis. Jurnal Sosiologi Agama, 15(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.14421/jsa.2021.152-06

- Harsono, A. (2020). ‘Religious harmony’ regulation brings anything but. Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2020/04/11/religious-harmony-regulation-brings-anything-but.html

- Hoon, C.Y. (2017, July). Putting religion into multiculturalism: Conceptualising religious multiculturalism in Indonesia. Asian Studies Review, 41(3), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2017.1334761

- International Crisis Group. (2012). Indonesia: From vigilantism to terrorism in Cirebon. In International crisis group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/indonesia-vigilantism-terrorism-cirebon

- Kadt, D. E. (2017). Assertive religion: Religious intolerance in a multicultural world. Routledge.

- Liddle, R. W., & Mujani, S. 2013. From transition to consolidation. In M. Künkler & A. Stepan. Eds., Democracy and Islam in Indonesia (pp. 24–50). Columbia University Press. 978-231-53505-2.

- Lovita, L. (2017). Radikalisme Agama di Indonesia: Urgensi Negara Hadir dan Kebijakan Publik yang Efektif. INFID.

- Mietzner, M., & Muhtadi, B. (2018). Explaining the 2016 Islamist Mobilisation in Indonesia: Religious intolerance, militant groups and the politics of accommodation. Asian Studies Review, 42(3), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1473335

- Mietzner, M., & Muhtadi, B. (2020). The Myth of Pluralism: Nahdlatul ulama and the politics of religious tolerance in Indonesia. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 42(1), 58–84. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs42-1c

- Mujani, S. (2019). ExplainIng Religio-Political Tolerance Among Muslims: Evidence from Indonesia. Studia Islamika, 26(2), 319–351. https://doi.org/10.15408/sdi.v26i2.11237

- Nottingham, E. K. (1985). Religion and Society. CV. Rajawali.

- Rachman, T. 2017. Contextualizing jihad and mainstream Muslim identity in Indonesia: The case of ‘Republika Online’. Asian Journal of Communication, https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2016.1278251.

- Setara Institute. (2018) . Indeks Kota Toleran 2018. SETARA Institute for Democracy and Peace Jakarta.

- Setara Institute. (2020). Terjadi Penjalaran Intoleransi di Daerah. Pemerintah Pusat Harus Hadir. https://setara-institute.org/terjadi-penjalaran-intoleransi-di-daerah-pemerintah-pusat-harus-hadir/

- Skitka, L. J., Hanson, B. E., Washburn, A. N., Mueller, A. B., & van Elk, M. (2018). Moral and religious convictions: Are they the same or different things? PLoS One, 13(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199311

- Tamir, C., Connaughton, A., & Salazar, A. M. (2020). The global god divide. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/07/PG_2020.07.20_Global-Religion_FINAL.pdf

- Wahid, A., Rakhmawati, F., & Destrity, N. (2020). Memahami Konsepsi “Kafir” pada Organisasi Keagamaan Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) dan Muhammadiyah di Media Sosial. KOMUNIKATIF : Jurnal Ilmiah Komunikasi, 9(2), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.33508/jk.v9i2.2371

- Walt, J. L. 2014. Measuring religious tolerance in education. Towards an instrument for measuring religious tolerance among educators and their students worldwide. https://www.driestar-educatief.nl/medialibrary/Driestar/Engelse-website/Documenten/2014-VanderWalt-Measuring-religious-tolerance-in-education.pdf

- Walzer, M. (1997). On Toleration. Yale University Press, 1997.

- Zaduqisti, E., Mashuri, A., Zuhri, A., Haryati, T. A., & Ula, M. (2020). On being moderate and peaceful: Why Islamic political moderateness promotes outgroup tolerance and reconciliation. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 42(3), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0084672420931204

- Zulkifli, Z. (2013). The struggle of the Shi‘is in Indonesia. ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_462194