Abstract

Literature often describes the archetypical ecotourists as well-educated, and financially secure, coming from the “Western” Baby Boomer with strong convictions on the need for the conservation of nature and indigenous cultures. Today, traveling is made affordable for the mass coming from diverse nationalities, particularly of the younger generation, who are eager to experience disappearing cultures and nature. Although they appear to share traits of the ecotourists, are they truly the younger generations of ecotourists or do they seek out similar destination sites but for different reasons? Our research is the first attempt to answer this question. The paper aims to redefine the archetypical ecotourists in a market dominated by generations X, Y, and Z. The study involved survey questionnaires administered to 237 respondents living in Brunei coming from multiple generations comparing their attitudes, travel motivations, interests, and behaviour. A stratified-convenience sampling method was used to distribute the questionnaire to capture equal numbers of respondents in the three different generation groups. The data reveals some degree of incongruency between the younger generations of ecotourists and of the old archetypes. We found that the new ecotourists deviate in ideology and value. The new ecotourists are more inclined towards hedonism, social approval and popular culture. The differences in archetype have implications for tourism planning in general, and ecotourism in particular.

1. Introduction

Ecotourism often represents a Western paradigm shift from a traditional mass tourism that is destructive to a more environmental conscious “green” paradigm (Fennell & Weaver, Citation2005). Ecotourism is a form of alternative tourism that would fulfil the goals of both conservation and sustainable development (Jamaliah & Powell, Citation2018). The study of ecotourism has been trendy and popular (Buckley, Citation2016; Donohoe & Needham, Citation2006) since its emergence in 1992 (World Tourism Organisation WTO, Citation2003). In addition, scholars categorize ecotourists as a distinct market segment that have strong belief in sustainability principles; concerns for environmental conservation and are more environmentally friendly than mass tourists (Beaumont, Citation2011; D. B. Weaver & Lawton, Citation2002; Fennel & Eagles, Citation1990; Kwan et al., Citation2010). The demand for such tourism is evident as more travelers are aware about sustainability practices and issues. The Allied Market Research reported that the ecotourism market size was valued at $181.1 billion in 2019 and projected to reach $33.8 billion by 2027 with Generation Z segment to be forecasted to exhibit the biggest growth ecotourism (Vig & Deshmukh, Citation2021). With the growing interests in sustainable, greener holiday experiences, destinations are trying to react to the changing tourist segment to stay competitive (Chin & Hampton, Citation2020; Chin & Noorashid, Citation2022; Chin et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Pehin Dato Musa & Chin, Citation2021). Paying attention to the next wave of ecotourists who may not necessarily share the typical characteristics and wants of the traditional ecotourists is needed. The paper aims to redefine the archetypical ecotourists in a market dominated by generations X, Y and Z. The specific objectives are: (a) differentiate the salient characteristics of generation X, Y and Z tourists; (b) understand their views of ecotourism; and (c) identify the distinctive features of the generation X, Y and Z ecotourists.

2. Literature review

2.1. Ecotourism and typologies

2.1.1. Ecotourism

Ecotourism is an alternative tourism sector that emerged from the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 as part of responsible travel and sustainable development for developing countries (Nistoreanu et al., Citation2011; WTO, Citation2003; Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008). The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) (Citation2018) defines ecotourism as responsible travel to natural areas with the purpose of conserving the environment, sustaining the well-being of the local people, and educating tourists. Ecotourism has gained popularity and has been promoted as an integral tool for natural resource conservation and the development of indigenous communities providing financial benefits and empowerment of local people (Stronza, Citation2007). It is perceived as a win-win tourism development strategy; supporting livelihood diversification, promoting cultural respect, and simultaneously offering low entry barriers, contributing to eradicating poverty and conservation (Surendran & Sekar, Citation2011). Yong and Noor Hasharina (Citation2008, p. 39) argue that ecotourism principles can appear to be a highly idealistic brand of tourism that priorities sustainable environmental, social and cultural values, but puts less or no emphasis on economic growth or profits that would help ensure the survival of the destination ecotourism businesses in a very competitive market. This, they argue, is particularly so for most developing countries ecotourism industry.

There is a spectrum of ecotourism that would distinguish activities (see Laarman and Durst (Citation1993) on soft and hard ecotourism; Orams (Citation1995, Citation2001) on behavioral and environmental indicators; Duffus and Dearden (Citation1990) on the relationship between changing visitation patterns and site evolution; Mehmetoglu (Citation2005) on motivational scales which contributed to the soft-to-hard ecotourism continuum). D. B. Weaver and Lawton (Citation2002) use the ecotourism spectrum to discuss types of ecotourism where “hard” ecotourism involves stronger environmental commitment with an emphasis on personal experience with little or no requirement of infrastructure. Those interested in this kind of ecotourism are motivated primarily by a scientific interest in nature. In contrary, they state that “soft” ecotourism includes moderate environmental commitment requiring infrastructure and services to cater for their physical comfort. Soft ecotourism is the fastest growing segment which is less intense.

2.1.2. Ecotourists

Ecotourism consumer encompasses all types of visitors that are interested in “green” or “eco” products ranging from different typologies which typically distinguish between hard and soft, deep or shallow, expert or novice ecotourists (D. Weaver, Citation2002; Fennell, Citation2004). They are concerned about safeguarding the natural resources, have strong pro-environmental attitudes and are more ecologically friendly in comparison to mass tourists. They prefer nature-based product that are supported by sustainability principles while concurrently provide learning opportunities (Beaumont, Citation2011; Deng & Li, Citation2015; Kwan et al., Citation2010; Nowaczek & Smale, Citation2010; Perkins & Brown, Citation2012).

However, the understanding of ecotourist and their characteristics remains stagnant (since the 1990s) despite TIES having links to industries that understands the changing archetypes and demands of ecotourists. Industries or businesses research and reports on ecotourists often consider changing demography of ecotourists and their demands. Academic literature suggests that ecotourists are: (a) Western or Developed countries baby boomers; (b) high income Nistoreanu et al., Citation2011); (c) experienced travelers, (d) highly educated, (e) opinion leaders, (f) enjoy sharing their experiences with friends and colleagues about their trip (The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) Citation2006, p. 3); share similar educational background which undoubtedly shape their worldview (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008). These people do not mind spending more for an ecotourism package as long as it fits with their worldview and value system. While they tend to travel on cheap fares, they are willing to spend considerably more money on environmentally friendly and socially responsible hotels, travel packages or operators (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008, pp. 39–40). Nowadays, ecotourists come from non-western countries, both developed and developing, such as Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008, p. 39).

Ecotourists want: quality service and a decent level of comfort; professional local guides; small groups (maximum 15 people); educational programs; quality and tasty food, based on traditional local products that are region specific; quiet areas, quality accommodation, but not luxurious, clean; conditions typical of rural housing; conservation of nature (a part of their money to go directly or indirectly to the conservation of nature) (Nistoreanu et al., Citation2011, p. 35). However, the complexity of tourist behavior, the archetype and typology of ecotourists in this multigenerational era especially with the younger generational cohorts have evolved with time. Recent studies have turned its attention to a tourist segment—the young who currently represent the larger tourism market share current as well as the future (Chen & Chou, Citation2019; Fyall et al., Citation2017; Pendergast, Citation2010). Therefore, knowing the multigenerational mindset is crucial in pushing the growth and sustainability of tourism in particular ecotourism.

Moreover, Nowaczek and Smale (Citation2010), Perkins and Brown (Citation2012), Ramchurjee and Suresha (Citation2015), and Ruhanen (Citation2019) questioned the extent of ecotourists being responsible travelers while on holiday as tourists may struggle with curtailing their enjoyment during their ecotourism activities. In addition, Millar et al. (Citation2012) argue that price and convenience plays a huge factor in visitor’s decision or motivation to travel rather than environmental responsible habits. Lemenin and Smale (Citation2007) argue that previous definitions of ecotourists are based on geographic location (destination visited) and their behavior (activities and engagements within the destination), but these fail to consider the visitors’ fundamental beliefs and values and if their beliefs and values conform to the ideal ecotourism and ecotourist values and norms.

It should also be understood that ecotourism and ecotourists may vary according to regions and to understand ecotourism demand better, and one has to understand that consumption is beyond just material (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008). They argue that ecotourism consumption is at the highest levels in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs because while tourism satisfies the human need to discover and experience new environments, “ecotourism satisfies mental and spiritual needs, in the form of symbols, knowledge, gesture and experience that convinces the person that he or she has conformed to sustainable development principles and acted for the good of humanity” (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008, p. 41).

2.2. Generational theory

According to the Generational Theory, important historical events and social changes in society affect the values, attitudes, beliefs and inclinations of individuals, therefore people who were born in the same period share similar core values (Moss, Citation2016). Strauss and Howe (Citation1991) created the Generational theory, which categorizes people based on their belonging to a specific generation determined by their birth year. Each of these generational designations corresponds roughly to a period of 20 years as illustrated in the age ranges of each of the following generational groups: Baby boomers, Generation X, Generation Y and Generation Z (see Table ).

Table 1. Generation cohorts information

To understand the new ecotourist archetypes, we need to understand factors that would influence them as consumers, in this case, ecotourists and their demands:

2.2.1. ICT and Knowledge

Generation X grew up during the emergence of ICT. ICT has been heavily immersed into their daily lives in comparison to the previous baby boomer generation who are digital immigrants (Leask et al., Citation2013). The younger the generation, the better their access to formal education and knowledge through the internet as well as ownership to digital education tools such as the smartphones (Fry et al., Citation2018). Gen Y and Generation Z have learned to multi-task and engage in the active learning experience by using technology while simultaneously being involved with other activities (Shatto et al., Citation2016).

Generation Z is the newest generation who is growing up in an Internet world and their worldview is molded and formed by the internet in a manner unlike previous generations (Adamson et al., Citation2017). This generation is used to fast dissemination of information presented in a graphically and technologically sophisticated style. Similar to the previous generations, learning is engaged and active, including participatory activities with a preference of listening less and doing more (Shatto & Erwin, Citation2017). Adamson et al. (Citation2017, p. 29) described generation Z as “growing up in a virtual cloud of technology with infinite sources of information and digital interactions” which have changed the way they think, communicate and learn. This substantial dependence on and immersion with technology is associated with shorter spans of attention (Chicca & Shellenbarger, Citation2018).

2.2.2. Culture and consumption

Baby boomers are spendthrift consumers compared to the other generation and are mostly retired from the workforce (Cleaver & Muller, Citation2002). This generation has achieved a better-quality lifestyle, and do not see price as an issue, and earn and consume more goods than any of the previous generation as well as the generational cohorts after them (Cleaver & Muller, Citation2002; Hassan, Citation2017). The majority of them would have met their basic needs and would have other non-materialistic demands, such as social acceptance, security, new experiences, and ultimately to “self-actualization (the need to discover the “self”, “destiny”, “purpose in life”, and other spiritual quests) (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008, p. 41). Ecotourism is consumption at the highest levels in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (ibid). On the other hand, the majority of Generation Y still live with their parents, are spendthrifts and tend to seek to consume based on social value and social biographies attached to the product thus are pulled into brand names and often willing to pay additional for certain brands with “cool” products (Chen & Chou, Citation2019). They also seek experiential consumption involving guest interaction, doing more in a co-creative manner and is enticed to cool branded products (Leask et al., Citation2013; Valentine & Powers, Citation2013). Stein (Citation2013) reported that Gen Y is the beginning of the “Me Me Me” generation where they enter an era of the quantified self, recording their daily lives and sharing their life and whereabouts with their social peers to seek constant approval from their social network.

The younger generation often consume mainly for hedonistic experiences and their consumption is dependent and influenced by their social groups especially their parents (Hassan, Citation2017). Generation Y and Z are informed consumers often conducting research prior to consumption. Like Gen Y, they are also attracted to ethical or sustainable brands, often looking for the best deals and often try to influence others including their (social media followers or peers) consumption patterns (World Economic Forum, Citation2022). Gen Y and Z put their self and hedonistic experiences above others but Gen Z is deemed the hyper-connected generation that puts importance on social networks through their gadget and internet use where the smart phone is the or primary device to keep memories and post their everyday activities online, e.g.,, selfies on social media (Gӧrpe & Ӧksüz, Citation2022).

2.2.3. Nature and environment

Baby Boomers donate more to charities that help the environment compared to the younger generations. According to Bochert et al. (Citation2017, p. 6), “ … the concept of sustainability was the creation of the Baby Boomers, the members of Generation X developed the concept, put it to test, and discovered its strengths and weaknesses and the members of Generation Y started to actively put into practice this concept and has gone further by innovatively reshaping the content”. Generation Y and in particular generation Z consumer movements are influenced by knowledge linked to Climate change and Crisis. Gen Y has strong egocentric environmental values and a disconnect between stated environmental values and travel behaviours (Vermeersch et al., Citation2016). They would have entered the workforce in the last decade and studied the importance of sustainable development (Buffa, Citation2015).O. A. Williams (Citation2020) states that the younger generation movements are influenced by concepts such as greenwashing. She argued that younger consumer movement such low cost flying and some vegan lifestyles can be as, if not more, environmentally destructive. Green living and climate conscious behaviours are often seen as the domain of the young, but the older generation are often taking action and charge to ensure sustainability (Zelda Bentham, group of Sustainability for Aviva in O. A. Williams, Citation2020).

2.2.4. Travel and tourism

Globalization and the improvements in ICT have resulted in the shrinking of space and time to travel and accelerated the flow of culture and knowledge related to tourism and conservation of nature and culture (Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008). A person’s ability, mobility and motivation to travel are important for tourism (Adli & Chin, Citation2021; Najib & Chin, Citation2021; S. Williams, Citation1998). Ability includes a person’s financial means and time to travel, while mobility is a person’s ability to access transport to travel and motivation is the driver for the travel. Development in financial structures has enabled consumption and spending. The growth of more affluent societies with growth of middle class and economic development, as well as, the deregulation of finances such as introduction of credit cards and borrowing facilities as well as availability of online payments and transfers of money has made it easier for the people including the lower income groups to spend including travel (Hassan, Citation2017; Langley, Citation2008). In addition, tourism infrastructure online to book for destination accommodation, attractions, and information on tourism products online has made travelling convenient e.g., Booking.com, Agoda and Airbnb. In addition, the development of other tourism infrastructure such as airports and introduction of budget airlines or low-cost carriers have revolutionized tourist movements and increased connectivity (Plumed Lasarte et al., Citation2016). Moreover, these are preferred platforms of the younger generations and industries have adapted to changes in travellers needs based on changing generations.

There is a dearth in academic literature that examines newer archetype of ecotourists with the emergence of new generations of ecotourists i.e., Gen X, Y and Z. This paper will address the new ecotourist archetype. The generational theory offers valuable profiling traits, values and behaviors of each social generation that would help explain different generational tourists including that in Brunei. It should be noted that the generational divisions are not clear-cut and that there is considerable overlap.

3. The research context

Brunei was the bastion of Islam and its propagation in most of the region since the 15th century with the installation of the first Muslim Sultan. As a strong kingdom with Kampong Ayer as an international trading port, it was also a center from which Islam was propagated in the region resulting in the Castilla War which saw Spain declaring war on Brunei during the reign of Sultan Saiful Rijal (Hasharina Hassan & Yong, Citation2019). In addition, after regaining independence from the United Kingdom in 1984, Brunei adopted a national philosophy known as Malay Islamic Monarchy (or MIB, abbreviation of the Malay translation), which has been incorporated in all aspects of its development policy, governance, and national institutions. This is important to consider in the study of new/young ecotourists, which had their formative education after 1984. All Gen-Y and Gen-Z in Brunei may be regarded as fully indoctrinated in the national philosophy as it was taught at all levels of the education system and embedded in social institutions. Gen-X, who formed the main part of the workforce post-independence, would have become increasingly ingrained in MIB concepts and values. The key tenets of MIB encompasses religious observation of Malay Islamic practices, such as prayers, halal or Islamic consumption, promoting modesty, etc. MIB is expected to have an influence on ecotourist demands in Brunei.

Brunei Darussalam is known as a “high income, oil-rich state with a population of about 440,000 (78% urban), per capital GDP of US$27,000, and a share GDP from agriculture, forestry and fishing that is barely more than 1% of the total” (Hassan et al., Citation2022, p. 133). Located on the Borneo Island, Brunei is renowned for its vast pristine rainforest. As part of its economic diversification and sustainable development programmes, Brunei Darussalam is actively promoting tourism as one of its priority sectors, which includes sustainable or ecotourism (Government of Brunei, 2020; Pehin Dato Musa & Chin, Citation2022). Brunei’s Green Jewel that consists of its pristine rainforests and rich biodiversity are unique compared to other Southeast Asian rainforests filled with species that are new to science (Noor, Citation2021). Brunei is quickly developing a reputation as an ecotourism centre with a 20% increase in international eco travellers or ecotourists numbers in 2017 mainly due to attractive ecotourism and nature tourism especially in the Temburong district (Lonely Planet, Citation2022). During the pandemic, the national borders were closed and Brunei saw an increase in domestic tourism including those interested in visiting ecotourism destinations. They consist of visitors from Gen X, Y and Z (locals and foreigners) in Brunei.

4. Methodology

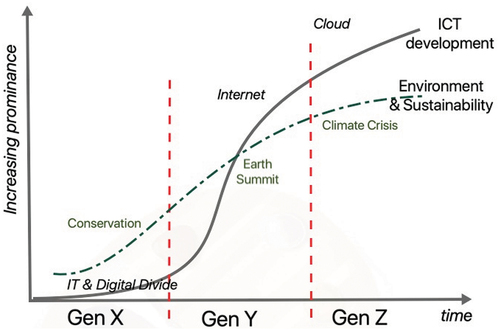

Archetypical ecotourists are motivated by their interest in protecting diminishing pristine nature areas, including the human natives and wildlife that are threatened by loss of their homes, culture and habitat, and their ability to contribute to their conservation and even, remediation. Invariably, they are willing to pay more for the privilege to be part of something important. As the study aims to compare the young eco travellers with the older ecotourists, who are mostly from the baby Boomer generation, surveys are design to gather information on the motivation, interests and views on ecotourism for comparison. The questionnaire used is designed by taking into consideration of the changing realities of each of the younger generation. One of the main drivers of change are (a) emergence of information technology (IT), which evolved into information-communication technologies (ICT), networks, wirelesses systems, the “cloud”, and the changes they created in business, economics, consumption pattern, social-cultural norms, and advances in the gamut of industry, institutions, interaction, knowledge creation and dissemination, and travel and tourism. The other is the rise of concern over the environment, sustainability of human-environment interaction, and in recent decades, a climate crisis on Earth.

The study involved survey questionnaires administered to 237 respondents living in Brunei coming from multiple generations comparing their attitudes, travel motivations, interests and behaviour. A survey was designed by the authors and conducted using a questionnaire, which asked the respondents questions on their interests, beginning with nature, outdoors activities, favourite pastime, likely purchases while on holiday, and how much they typically spend. It then asked questions to compare their views with that of the archetypical ecotourists, such as love of nature, passion for conservation, contributing to wellbeing of local communities, environmental responsibilities, and importance of conservation in ecotourism packages. Answer options were provided, ranging from “hard” to “soft” ecotourism views to non-ecotourist ones. Respondent details collected are age, gender, ethnicity and nationality. A stratified-convenience sampling method was used to distribute the questionnaire to capture equal numbers of respondents in the three different generation groups. Contact details were acquired for a follow-up survey (Survey 2) later in the month.

A second survey was designed by the authors to gather more details on the demands of the same group of respondents. They include: what they are most likely to buy on an eco-cultural trip; desired services; preferences and dislikes in cultural performances, amenities at destination; and biggest turnoffs. They were also presented with six made-up packages to gauge their level of interest and willingness to pay. They range from free and easy nature immersion package (N001); an outdoor activity (N002); “native experience” (N003); week-long stay with a tribe whose land and lifestyle are threatened by loggers (C001); volunteerism package at a rainforest site (C002) and Ngajat (Dayak dance) workshop (C003). Respondents were asked to provide a score using a 5-level scale to indicate degree of interest, importance or agreement.

5. Results and analysis

The total sample size (N) in the first survey was 237. Thirty-six did not answer the second survey. The majority of the respondents were local Bruneian of Malay ethnicity, the main group in the Brunei population. Foreign nationals (Malaysian, Singaporean and Thai) numbered only 17 (7.1%). Other ethnicity comprised Chinese, Thai, Dusun, Murut, Kedayan, Kadazan and Iban, totaling 34 (14.4%). Those who considers themselves as ecotourists (ET) accounts for a third or less of the survey sample. The majority did not know (DK) whether they consider themselves as ET. Data analysis will focus on the ET group; the DK group is used for comparison. The three groups could be regarded as equally represented in the first survey, but there were slightly fewer Gen-X in the second survey. Table shows the respondents’ details.

Table 2. Respondent details

Tables compare the generational differences on common interest in ecotourism by theme. The former relates to nature, while the latter, people and culture. The data represents a selection of the data set, due to space limitations of this paper. They show the percentage of only the responses by larger proportions of the group.

Table 3. Generational comparison on selected ecotourism interests: nature & conservation

Table 4. Generational comparison on selected ecotourism interests: people & culture

With respect to nature conservation, less than 20% indicated strong interest. The majority are “quite interested” with a rising trend from Gen-X to Gen-Z. The same trend and level of interest are observed in response to conservation in packaging ecotourism products. This is a similar pattern to the importance of green labelling or branding to younger generations argued by O. A. Williams (Citation2020). A smaller group is somewhat interested in nature conservation, but not so keen to get involved directly. The trend is inverse. This is similarly observed with the use of “green” wording in ecotourism packaging. Regarding interests in outdoors activities (OA), the majority often engage in them but prefer options that are “safe” and “not too rough”. The trend is also inverse, with Gen-X highest and Gen-Z lowest. About a third occasionally engages in OA, while a fifth to a quarter loves OA. While in nature, the majority takes time to appreciate nature and the environment, with Gen-X leading the inverse trend. The opposite is true for the next largest group, where Gen-Z leads (enjoying nature holistically, i.e., experientially, without knowledge of the details). This can be compared to the Ecotourism Spectrum where the younger generations in Brunei prefer soft ecotourism activities (D. B. Weaver & Lawton, Citation2002).

Concerning the local community in ecotourism destinations, the majority, particularly Gen-Z and Gen-X, are interested to see and learn about new cultures, but do not want to spend too much time with them. Gen-Y breaks the trend, revealing that a slight majority are interested to learn more about people and their culture. However, regarding contributing to the local community (a key tenet of the original ecotourism definition (Ceballos Lascurain, Citation1996; TIES, Citation2006), the majority (over two-thirds) said they would only spend to buy local products if they needed the items and that they are sold at a fair price. This is in stark contrast to the literature, which is shared only by a minority (less than a quarter), with an inverse trend. Most of the respondents, however, believe that it is very important to respect local communities, while about a third thought that it is fine as long as they do not deliberately offend them.

With respect to their top three favourite pastimes, all three groups identified the same, with only the order changed for Gen-Z, which has “nature and wildlife” as the top choice, and “people, culture and history” third; in contrast to the other groups, where “people, culture and history” is first, “nature and wildlife” second and “music and movies” third. Regarding how much they typically spend on a holiday, 53.2% of Gen-X indicated B$500–1,000, while another 20% said over $1,000 but below $5,000.Footnote1 The majority (65%) of Gen-Y would spend between B$300–1,000, with 25% less. Almost half (44%) of Gen-Z would also spend B$ 300–500, with about a quarter less and another quarter between B$ 500–1,000. This could be due to the fact that Gen-X are older and are likely to have amassed more savings than the others (see also Chen & Chou, Citation2019; Hassan, Citation2017). While Gen-Z has not had much time to work and save, this could be from more affluent families, based on the 25% in higher spending, and the other quarter from worst-off background.

The Top three spending identified by the Gen-X group are: (i) on reminders of the trips, (ii) for things to give friends and family, and (iii) paying because it contributes to a positive development. The last point aligns somewhat with the older generation ecotourists. Gen-Y’s top three are: (i) fun, relaxation and a good time, (ii) reminders of the trip, and (iii) things to give friends and family. Gen-Z prefers (i) fun, relaxation and good time, (ii) things to give friends and family, and (iii) personal enriching experience. It can be seen that souvenirs are important for all groups. The differences are in the preference for fun and a good time for the younger generations, but also different for goals for Gen-X (doing good) and Gen-Z (personal enrichment).

The final section of the analysis is to compare the views of the young ecotourists (ET), i.e., those who identified themselves as ET, with those who “don’t know” (DK). Table shows the percentage of ET and DK group that chose the answer options, sorted in descending order: (1) The data shows increasing percentage from Gen-X to Gen-Z of ET who would take time to appreciate nature and place. The trend is inverse for the DK group; (2) As for unwillingness to contribute to the local community, the proportions are high for both ET and DK groups, i.e., only buy if they need the products and the price is fair, rather than buy as a means to contribute to the local community’s livelihood; (3) As for clear conservation messages in ecotourism products, there is an increasing trend with younger generations, from 59% (Gen-X) to 82% (Gen-Z). In the DK group, the trend is similar but more subdued; (4) With regards to respecting locals, over two-thirds of ET thought it was important to do so, with Gen-Z highest (73%). The proportion is similar in the DK group, but lower percentage (47%) found in the Gen-X cohort, and; (5) Among the ET, interests in other peoples and cultures show increasing trend from Gen-X (41%) to Gen-Z (64%). However, in the DK group, interests are muted for all groups.

Table 5. comparison of responses to selected ecotourism views, survey 1

The lower half of Table shows the next larger groups for the same themes: (6) There is no trend for ET on avoiding offending local community. There is a clearer trend in the DK group, with Gen-X highest and Gen-Z (44%) lowest (29%); (7) The pattern is reverse for the next view on not wanting to spend too much time with the local community, where there is an inverse trend in the ET but no linear trend in the DK group; (8) In contrast to the older ecotourists, the proportion of those who think it is important to help local community is low and declining with younger generations in both ET and DK groups; (9) A similar inverse trend can be seen for ecotourism packages focusing only on nature conservation in the ET group. The percentage is higher in the DK group for Gen-Y and Gen-Z, and; (10) A larger proportion in the DK group indicated that they enjoy nature as a whole, with Gen-Y and Gen-Z at 50% and 54%, respectively. This is a smaller group among ET, who have a strong appreciation for nature.

There is limited space in this paper for a detailed analysis of the data from Survey 2. The salient features are that the younger generation demands a wider range of quality services than the archetypical ecotourists, who are more comfortable to immerse themselves in nature and in the lives of the people. Gen-Z are the most demanding, requiring the full range of provisions from knowledgeable guide, to detailed guidebook, cultural and culinary experiences, experiences of village life, trekking animals, and good photo op. This is also true of amenities, where Gen-X and Gen-Y are comfortable with more basic facilities. However, all lists comfort, safety, sanitary and private toilets, adequate signage, trash bins and concierge services as highly important. Gen-Z listed accreditation and certification of the ecotourism service or destination, and for safe consumption of food and water as well as Wi-Fi connection as high importance. These are all characteristics of ecotourists described by Millar et al. (Citation2012) where aside from price, convenience is an important factor when travelling.

An interesting finding are responses to opened ended part of questions on cultural performance, general dislikes and turn-offs. A significant number highlighted “offensive to Muslims”, which includes nakedness, rituals involving animals, etc. This is due to the fact that the majority of respondents are local Malay-Muslims. Although this may apply to the Brunei context, it should be of interest to industry, tourism planners and academia, because the Muslim market is large and growing; 140 million in 2018 (Islamic Tourism Centre, Citation2019). Additionally, there are also travellers from other nations that share similar conservative religious values, even though the religion is different.

In response to question on packages (N001-N003 and C001-C003), outing in natural areas are popular with all groups: 3.4 (Gen X), 3.9 (Gen Y) and 4.0 (Gen Z). Gen X has less enthusiastic responses to all other packages (2.5 to 3.0). In contrast, Gen Z is interested in all the packages (3.0 to 4.0). Gen Y is similarly interested in all packages except for the C001, threatened indigenous community, (2.8) and C003, Iban Dance (Ngajat), (2.5). Interestingly, both Gen Y and Z are interested in volunteerism.

6. Discussion

The findings show some similarity in the choices of younger ecotourists to the older Boomer generation ET, such as love of nature, interest in new cultures and respect for local community (Beaumont, Citation2011; Fennel & Weaver, Citation2005; Fennel & Eagles, Citation1990; Stronza, Citation2007; TIES, Citation2018; Yong & Noor Hasharina, Citation2008). However, the main difference is in the conviction and belief that characterize the older generation. This supports Zelda Bentham, Group of Sustainability for Aviva’s statement that the older generation are take action, make donations and take charge to ensure sustainability (see O. A. Williams, Citation2020). The younger generations treat ecotourism more as another type of product on offer, which concurs with the views that younger generation are attracted to cool branding or green products and concepts but their travel behaviours may not reflect the sustainable ideologies (Chen & Chou, Citation2019; Leask et al., Citation2013; O. A. Williams, Citation2020; Valentine & Powers, Citation2013). Their views and preferences could be elaborated with reference to Figure . It shows the two key drivers of changing culture from Gen-X to Gen-Z: (a) development of information-communication technologies and systems and (b) increasing concerns over environment and sustainability. Information technology (IT) was developed by Gen-X. It made industry, institutions and research more organized and data-driven (see also Bochert et al. (Citation2017) on Gen X as having similar characteristics when it comes to sustainable development concept). People were still very much connected to the physical-natural world, and were awakening to the negative impacts of modern development. It raises concerns over the finiteness of natural resources and the planet’s capacity to support an ever-rising human population and expanding economy. ET of this generation shares much of the same concerns and convictions of the previous generation, which is to appreciate and save what is left. However, more would be caught up with innovations that came about with IT in research and development.

Gen-Y has their formative years and early careers during the emergence of the Internet, where IT transitioned to ICT. This was similarly argued by Fry et al. (Citation2018). It ushered in the Knowledge Age, and e-commerce. Greater connectivity fosters and consolidated globalization of economy, politics and dissemination of knowledge and values. Environmental concerns lead to international collaborations and programmes to shift development and industry towards a sustainable path. Ecotourism and conservation were regarded as a means to achieve sustainable development. The Internet revolutionized commerce and consumption cultures. Langley (Citation2008) and Hassan (Citation2017) discussed the importance of the internet; travel and consumption culture and infrastructure improvements enabling spending and travelling. The internet produced a generation of 20-somethings millionaires and made society and economy more mobile and catalyzed innovation, making travel and consumption more accessible to wider section of society. Ecotourism promotes their products and services through websites and online services. Ecotourism demands information and adherence to international practices and standards, in particular, sustainability goals.

Gen-Z was born into a world mediated by ICT, where information and knowledge are accessible form the “cloud”, a complex network of networks created and operated by multiple human and artificial entities (see also Chicca & Shellenbarger, Citation2018). Knowledge is very much social constructed by social networks, which shapes society, cultures, values, as well as industry and economy. Concerns over the environmental sustainability has heightened to humanity confronting a global climate crisis. In this highly complex world, individuals occupy niches and many embraces diversity, while others hung on to traditional norms. Ecotourism is an important thing and something to explore, experienced and probably get involved. It exists more in the realm of mind and is highly regulated by systems and standards.

Perhaps, this explains why less than a third of the younger generation travellers considers themselves as ecotourists and about half said they do not know. In the increasingly complex world, there could be a trend of not defining oneself or being defined among the younger generations. There is also increasing detachment from physical-natural reality from Gen-X to Gen-Z, the latter more comfortable in simulate environments, where things are in their control. This could explain the trend and proportion that sees conservation objectives as important, but do not view contributing to the local communities with the same degree, because they do not think that they play an important role in conservation. Stein (Citation2013) and Gӧrpe and Ӧksüz (Citation2022) argue that Gen Y and Z prefer sustainable products but are often about quantified self and hedonistic experiences, memorializing their experiences for social approval among their peers and social networks. Cultures could be captured/learned and preproduced in different ways and format. Therefore, the new ecotourists are similar but also very different from the older archetype. They should be differentiated, and for want of a better term, perhaps could be tentatively referred to as E21-X, E21-Y and E21-Z for now.

7. Conclusion

There is a stagnation in definition of the ecotourist. The tourism industry has been catering to the new generation of ecotourists for more than a decade and are aware of the changing archetypes and demands of the new travellers. While ecotourism study has been popular, however, there is a lack of study of the new ecotourists archetypes post Baby Boomer generation in academia. Industry have done well to react to the generational changes and demands and utilizing ICT to capture and attract the newer generations of Eco travellers. In addition, the development of cheaper travelling, online tourism platforms as well as quicker dissemination of information on tourist destination coupled by growing trend of younger generation to support sustainable green products or brands and preference for more soft ecotourism activities influenced ecotourism development.

This paper redefines the archetype of ecotourists academically. The main conclusions are:

The new ecotourists share the same high appreciation of nature, and outdoors activities;

conservation is important, but Gen-X are less keen to be directly involved, while Gen-Y and Gen-Z are interested to learn more and even participate as volunteers;

There is generally some interest in indigenous people and culture, but Gen-X and Gen-Y are not interested to spend too much time with them.

In general, most are not interested to contribute monetarily to local community development and would only buy things that they need and at fair price.

Religion is a major factor, which should not be trivialized.

Ecotourism must not be rough and dirty, must be offered with full amenities and services for comfort, safe and meaningful experiences which can be digitally memorialized and shared.

The global and regional contribution of our study is that it addresses the merging sector of tourism market: Ecotourism and Islamic Tourism. Both are growing markets in tourism. The authors also recognise some limitations of the study. This study is carried out using Brunei as a case study, where respondents and findings might only reflect this part of the world. In addition, Brunei an Islamic country has increasingly ingrained MIB concepts and values which incorporates religious observation of Malay Islamic practices into the generational cohort that might generate findings more relevant to the Islamic world. However, the findings could be applied to the Malay world in Southeast Asia, which shares similar history, demography, climate and environment, impact of globalization and colonialism, and income disparity. Future research could perhaps look into a comparative study on the behavior of ecotourism from different generational cohort of different Muslim countries.

Declaration of interest

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Universiti Brunei Darussalam and TOTAL E&P [Grant number UBD/RSCH/1.21.3[a]/2018/007].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shirley Wei Lee Chin

Wei Lee Chin (Shirley) is an Assistant Professor in the Geography, Environment & Development Programme at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, specialising in destination competitiveness specifically in developing countries in Asia. Her research interest also includes small-scale island tourism, tourism community development, smart tourism, ecotourism, socio-economic sustainability as well as tourism impacts in Asia. She has field experience in Southeast Asia and is also a recipient of several University grants. She was also the Programme Leader of Geography and Environment Development programme She has also published in international journals like Current Issues in Tourism, Tourism and Hospitality Management.

Noor Hasharina Hassan

Noor Hasharina Hassan is a Senior Assistant Professor in the Geography, Environment & Development Programme at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam (UBD). She is also the Director of the Institute of Asian Studies, UBD. Her areas of research include sustainable urban development and consumption. Her current research examines urban sustainability, vulnerabilities and welfare. She recently published a paper entitled ‘Making do and staying poor: The poverty context of Urban Brunei’ with Geoforum. She is a member of the Asia in Transition Springer Book Series. She was Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of Geography at King’s College London and a Visiting Scholar at the East West Centre, Hawaii.

Gabriel Yv Yong

Gabriel Yong has an MSc in Environmental Analysis and Dynamics from Hull (1998) and has been studying human-environment systems for the past 25 years. His interest in ecotourism stems from his involvement in sustainable development and integrated management projects. He is currently involved in a project to develop the ecotourism capacity of an Iban community in the interior. Gabriel is a lecturer in the Geography, Environment and Development Program at Universiti Brunei Darussalam. He takes a complex systems approach to understanding geographical and sustainability phenomena and issues.

Notes

1. 1 Brunei dollars or B$1.00 is equivalent to 1 Singapore Dollars or SGD$1.00.

References

- Adamson, G., Wang, L., Holm, M., & Moore, P. (2017). Cloud manufacturing – A critical review of recent development and future trends. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 30, 347–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951192X.2015.1031704

- Adli, A., & Chin, W. L. (2021). Homestay accommodations in Brunei Darussalam. South East Asia Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(1), 15–29. https://fass.ubd.edu.bn/SEA/vol21-1/Homestay%20Accommodations%20in%20Brunei%20Darussalam.pdf

- Beaumont, N. (2011). The third criterion of ecotourism: Are ecotourists more concerned about sustainability than other tourists? Journal of Ecotourism, 10(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2011.555554

- Bochert, R., Cismaru, L., & Foris, D. (2017). Connecting the members of generation Y to destination brands: A case study of the CUBIS project. Sustainability, 9(1197), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071197

- Buckley, R. (2016). What does tourism tell us about cultural differences in perceptions of time? Tourism Recreation Research, 41(3), 363–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2016.1197540

- Buffa, F. (2015). Young tourists and sustainability. profiles, attitudes, and implications for destination strategies. Sustainability, 7(10), 14042–14062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71014042

- Ceballos Lascurain, H. (1996). Tourism, ecotourism, and protected areas: The state of nature-based tourism around the world and guidelines for its development. IUCN & The World Conservation Union.

- Chen, C. F., & Chou, S. H. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of perceived coolness for generation Y in the context of creative tourism - A case study of the pier 2 art center in Taiwan. Tourism Management, 72, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.016

- Chicca, J., & Shellenbarger, T. (2018). Connecting with generation Z: Approaches in nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 13(3), 180–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2018.03.008

- Chin, W. L., Fatimahwati, P. D. M., & Coetzee, W. (2021). Agritourism resilience against COVID-19: Impacts and management strategies. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1950290

- Chin, W. L., Haddock-Fraser, J., & Hampton, M. P. (2017). Destination Competitiveness: Evidence from Bali. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(12), 1265–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1111315

- Chin, W. L., & Hampton, M. P. (2020). The relationship between destination competitiveness and residents’ quality of life: Lessons from Bali. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 26(2), 311–336. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.26.2.3

- Chin, W. L., & Noorashid, N. (2022). Communication, leadership, and community-based tourism empowerment in Brunei Darussalam. Advances in Southeast Asian Studies, 15(2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-0075

- Cleaver, M., & Muller, T. E. (2002). The socially aware baby boomer: Gaining a lifestyle-based understanding of the new wave of ecotourists. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(3), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667161

- Deng, J., & Li, J. (2015). Self-identification of ecotourists. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(2), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.934374

- Donohoe, H. M., & Needham, R. D. (2006). Ecotourism: The evolving contemporary definition. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(3), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe152.0

- Duffus, D. A., & Dearden, P. (1990). Non-consumptive wildlife oriented recreation. A conceptual framework. Biological Conservation, 53(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(90)90087-6

- Fennel, D. A., & Eagles, P. F. J. (1990). Ecotourism in Costa Rica: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 1(8), 23–34.

- Fennell, D. (2004). Ecotourism: An Introduction. Routledge.

- Fennell, D., & Weaver, D. (2005). The ecotourism concept and tourism-conservation symbiosis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(4), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580508668563

- Fry, R., Igielnik, R., & Patten, E. (2018). How millennials today compare with their grandparents 50 years ago. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/16/how-millennials-compare-with-their-grandparents/

- Fyall, A., Leask, A., Barron, P., & Ladkin, A. (2017). Managing Asian attractions, Generation Y and face. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 32, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.04.006

- Gӧrpe, T. S., & Ӧksüz, B. (2022). Sustainability and Sustainable Tourism for Generation Z: Perspectives of Communication Students. In J. A. Wahab, H. Mustafa, & N. Ismail (Eds.), Rethinking Communication and Media Studies in the Disruptive Era (Vol. 123, pp. 97–111). European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2022.01.02.8

- Hasharina Hassan, N., & Yong, G. V. Y. (2019). A Vision in Which Every Family Has Basic Shelter. In R. Holzhacker & D. Agussalim (Eds.), Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN (pp. 190–209). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004391949_010

- Hassan, N. H. (2017). Everyday finance and consumption in Brunei Darussalam. In V. King, Z. Ibrahim, & N. H. Hassan (Eds.), Borneo Studies in History, Society and Culture. Asia in Transition (Vol. 4, pp. 477–492). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0672-2_23

- Hassan, N. H., Rigg, J., Azalie, I. A., Yong, G. Y. V., Zainuddin, N. H. H., & Shamsul, M. A. S. M. (2022). Making do and staying poor: The poverty context of Urban Brunei. Geoforum, 136, 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.09.012

- The International Ecotourism Society. (2018). What is ecotourism? The International Ecotourism Society. https://ecotourism.org/

- The International Ecotourism Society (TIES). (2006). “TIES global ecotourism fact sheet”. The International Ecotourism Society. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Chaminda-Kumara-5/post/Where-can-I-find-accurate-statistics-about-the-best-ecotourism-destinations-in-which-some-details-about-the-number-of-arrivals-are-mentioned/attachment/59d645e979197b80779a0f94/AS%3A455170728435714%401485532566915/download/1.PDF

- Islamic Tourism Centre. (2019) . “Development of Muslim friendly tourism: Malaysia’s perspective”. Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture.

- Jamaliah, M. M., & Powell, R. B. (2018). “Ecotourism resilience to climate change in Dana Biosphere Reserve”, Jordan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1360893

- Kwan, P., Eagles, P. F., & Gebhardt, A. (2010). ‘Ecolodge Patrons’ Characteristics and Motivations: A study of Belize’. Journal of Ecotourism, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040802140576

- Laarman, J. G., & Durst, P. B. (1993). Nature tourism as a tool for economic development and conservation of natural resources. In J. Nenon & P. B. Durst (Eds.), Nature tourism in Asia: Opportunities and constraints for conservation and economic development (pp. 1–19). United States Department of Agriculture.

- Langley, P. (2008). The everyday life of global finance: Saving and borrowing in Anglo-America. Oxford University Press.

- Leask, A., Fyall, A., & Barron, P. (2013). Generation Y: Opportunity or challenge – strategies to engage generation Y in the UK attractions’ sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.642856

- Lemenin, R. H., & Smale, B. (2007). Wildlife tourist archetypes: Are all polar bear viewers in Churchill, Manitoba Ecotourists? Tourism in Marine Environments, 4(2–3), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427307784771986

- Lonely Planet. (2022). “Why Brunei Darussalam is getting a reputation as an ecotourism destination”. https://www.lonelyplanet.com/news/brunei-ecotourism-destination.

- Mehmetoglu, M. (2005). A case study of nature-based tourists: Specialists versus generalists. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766705056634

- Millar, M., Mayer, K. J., & Baloglu, S. (2012). Importance of green hotel attributes to business and leisure travellers. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 21(4), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2012.624294

- Moss, S. (2016). Generational cohort theory. Sicotests. http://www.sicotests.com/psyarticle.asp?id=374

- Najib, N., & Chin, W. L. (2021). Coping with COVID-19: The resilience and transformation of community-based tourism in Brunei Darussalam. Sustainability, 13(15), 8618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158618

- National Academies of Sciences. (2020). Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25796

- Nistoreanu, P., Dorobantu, M. R., & Tuclea, C. (2011). The trilateral relationship ecotourism – sustainable tourism – slow travel among nature in the line with authentic tourism lovers. Revista De Turism, 11(11), 34–37.

- Noor, A. 2021. “Discovering Brunei’s green jewel”, Borneo Bulletin. https://borneobulletin.com.bn/discovering-bruneis-green-jewel/

- Nowaczek, A., & Smale, B. (2010). Exploring the Predisposition of Travellers to Qualify as Ecotourists: The Ecotourist Predisposition Scale. Journal of Ecotourism, 9(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040902883521

- Orams, M. B. (1995). Towards a more desirable form of ecotourism. Tourism Management, 16(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(94)00001-Q

- Orams, M. B. (2001). Types of ecotourism. In D. Weaver (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism (pp. 23–36). CABI.

- Pehin Dato Musa, S. F., & Chin, W. L. (2021). The role of farm-to-table activities in agritourism towards sustainable development. Tourism Review, 77(2), 659–671. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2021-0101

- Pehin Dato Musa, S. F., & Chin, S. W. L. (2022). The contributions of agritourism to the local food system. Consumer Behavior in Tourism and Hospitality, 17(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/CBTH-10-2021-0251

- Pendergast, D. (2010). Getting to know the Y generation. In P. Benckendorff, G. Moscardo, & D. Pendergast (Eds.), Tourism and Generation Y” (pp. 1–15). CAB International.

- Perkins, H. E., & Brown, P. R. (2012). Environmental values and the so-called true ecotourist. Journal of Travel Research, 51(6), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512451133

- Pew Research Center. (2018). Early benchmarks show ‘post-millennials’ on track to be most diverse, best-educated generation yet. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/11/15/early-benchmarks-show-post-millennials-on-track-to-be-most-diverse-best-educated-generation-yet/

- Plumed Lasarte, M., Latorre, P., Íñiguez-Berrozpe, T., & Martínez, J. (2016). Low-cost airlines and tourism: Analysis of the case of Easyjet from the perspective of complex networks and its management implications. In F.-J. Sáez-Martínez, J. L. Sánchez-Ollero, A. García-Pozo, & E. Pérez-Calderón (Eds.), Managing the environment: Sustainability and economic development of tourism (pp. 5–19). Oxford.

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816

- Ramchurjee, N., & Suresha, S. (2015). Are tourists’ environmental behavior affected by their environmental perceptions and beliefs? Journal of Environmental and Tourism Analyses, 3(1), 26–44.

- Ruhanen, L. (2019). The prominence of eco in ecotourism experiences: An analysis of post-purchase online reviews. Journal of Hospitality and Management, 39, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHTM.2019.03.006

- Shatto, B., & Erwin, K. (2017). Teaching millennials and generation Z: Bridging the generational divide. Creative Nursing, 23(1), 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1891/1078-4535.23.1.24

- Shatto, B., Erwin, K., Billings, D. M., & Kowalski, K. (2016). Moving on from Millennials: Preparing for Generation Z. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 47(6), 253–254. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20160518-05

- Stein, J. (2013). “Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation”, Time Magazine. https://time.com/247/millennials-the-me-me-me-genreration/.

- Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (1991). Generations: The history of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. Morrow, William and Co.

- Stronza, A. (2007). The economic promise of ecotourism for conservation. Journal of Ecotourism, 6(3), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe177.0

- Surendran, A., & Sekar, C. (2011). A comparative analysis on the socio-economic welfare of dependents of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve (ATR) in India. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 5(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/097380101100500304

- Valentine, D. B., & Powers, T. L. (2013). Generation Y Values and lifestyle segments. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(7), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-07-2013-0650

- Vermeersch, L., Sanders, D., & Willson, G. (2016). Generation Y: Indigenous tourism interests and environment values. Journal of Ecotourism, 15(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1165233

- Vig, H., & Deshmukh, R. (2021). “Ecotourism market”. Allied Market Research. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/eco-tourism-market-A06364

- Weaver, D. (2002). Ecotourism. Wiley.

- Weaver, D. B., & Lawton, L. J. (2002). Overnight ecotourist market segmentation in the gold coast Hinterland of Australia. Journal of Travel Research, 40(3), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750204000305

- Williams, S. (1998). Tourism geography. London Routledge.

- Williams, O. A. (2020). Boomers versus Millennials: Which Generation is more Environmental? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/oliverwilliams1/2020/02/17/boomers-versus-millennials-which-generation-is-more-environmental/?sh=1006e72e5718

- World Economic Forum. (2022). “Gen Z cares about sustainability more than anyone else – and is starting to make others feel the same”. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/generation-z-sustainability-lifestyle-buying-decisions/

- World Tourism Organisation (WTO). (2003). “Assessment of the results achieved in realizing aims and objectives of the international year of ecotourism”. Report to the UN General Assembly, 58th Session, Item 12.

- Yong, G. Y. V., & Noor Hasharina, H. H. (2008). Strategies for Ecotourism: Working with globalization. Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8, 35–52.