Abstract

Youth engagement in agribusiness is increasingly recognized as an important strategy to create employment opportunities, particularly for young people themselves and for the development of agri-/food systems in Africa. The non-participation among youth in the agri-/food business sector may be because of their various perceptions. The objective of this study is to review studies on the perception, interest and participation of youth in agribusiness in the various countries in Africa. The youth in Africa mostly have a negative perception with regard to agriculture. This influences their intention and participation in Agriculture. There is a lack of access to land; finance; technology; and education and skills in agribusiness. There are however mixed findings on access to finance and its influence on the engagement of the youth in agriculture. More studies should look at the influence of access to finance and other resources on youth engagement in agriculture. Further studies should look at the perception, intention and participation of the youth in agribusiness.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is the backbone of Africa’s economy. Various African countries have specialized in the production of different varieties of agricultural produce in Africa. For example, about half of the world’s cassava is grown in Africa, with Nigeria, the Congo, and Tanzania producing the majority (IFAD, Citation2005). Ghana is the second world producer of cocoa in the world; the agriculture sector employs more than 50% of the people in Ghana (Breisinger et al., Citation2008). Liberia is a country with the highest ranked agriculture percentage to GDP at 76.9%. It is projected that the demand for food in Africa will increase by 2.5 to 3 times that of 2015 by 2050 as a result of population growth (Elferink & Florian, Citation2016). The need to improve agriculture with the strengthening of other sectors like the input, process and service sector comes into play.

Youth engagement in agribusiness is encouraged as the youth are the future of the African continent (Swarts & Aliber, Citation2013). The youth have the potential to strength the agriculture sector by strengthening the input, processing and service sector. The youth are encouraged to participate in agriculture when their perception and intention toward agriculture are positive (Henning et al., Citation2022). Perception informs intention and participation in the agribusiness industry. Negative perception would lead to less participation in agriculture sector; the opposite holds. There are various perceptions and intentions among youth with regard to agriculture in various African countries. Some studies mention the positive perception of the youth (Magagula & Tsvakirai, Citation2020; Maritim, Citation2020) while others mention the negative perception of the youth (Heifer International, Citation2021; Sumberg et al., Citation2017) in various countries in Africa. For example, students are likely to be agripreneurs when parents have access to land and are farmers themselves (Bednaříková et al., Citation2016). Mengistu (Citation2017) and USAID Feed the Future Programme (Citation2017) however mention that even families that are into agriculture do not encourage their children to venture into farming.

Aside from the perception of the youth with regard to agriculture, there are some influences that lead to the participation of the youth with regard to agriculture or otherwise. For instance, Haggblade et al. (Citation2015) mentioned that most youth venture into agriculture because their families have experience in agriculture. Lack of participation of youth is however linked with lack of access to resources like technology and finance (Borgen Project, Citation2014), skill development (Blattman and Annan, Citation2011; McMullin, Citation2022), (USAID Feed the Future Programme, Citation2017) and weak linkages in the value chain (Janzen, Citation2014). Literature on the interest and participation of youth in agribusiness is however mixed. Wuni et al. (Citation2017) mentioned that the youth are not interested and do not want to participate in agriculture. Yami et al. (Citation2018) however mention that the youth are interested in agriculture but do not want to participate in agriculture.

Youth engagement in agribusiness is increasingly recognized as an important strategy to create employment opportunities, particularly for young people themselves and for the development of agri-/food systems in Africa (Yami et al., Citation2018). There is thus the need to engage the youth in agribusiness as unemployment of the youth in Africa continues to surge and the agribusiness sector promises careers for the youth. There is a need to find out the perception, interest and participation of youth in agriculture and the challenges resulting in the non-participation of the youth in agribusiness.

The objectives of this study are:

To review the perception, interest and participation of youth in agribusiness in the various countries in Africa.

To review what influences youth participation in agribusiness in Africa

Findings from this study will be used to facilitate discussions on critical areas of intervention toward effectively engaging the youth in the county’s agribusiness sector. Ultimately, they will inform the maximisation of the potential of strengths and opportunities while minimising the impact of weaknesses and threats towards youth engagement to enhance the competitiveness of Africa’s agribusiness sector. This study would lead to strengthen the agribusiness value chain and promote youth lead enterprises. This is because the strengths and weaknesses of youth lead enterprises would be identified. After weaknesses are identified, opportunities available would be used to minimize weaknesses. Also, various African government would be shown the benefit of building infrastructure to encourage agribusiness among youth in the country.

This study would help to implement World Bank’s (Citation2016) recommendation that the youth should be encouraged into agripreneurship and that agriculture should be integral in various programs to attract the youth. Academic institutions would be enlightened on the ways to create an avenue for students and graduate to be agripreneurs and be employed in the agribusiness value chain. This research would help to identify the aspiration and expectations of the youth in Liberia. Programmes and projects would be targeted to help the youth achieve this aspiration.

2. Methodology

The systematic literature review focused on peer-reviewed literature supplemented with available “grey” literature for areas of interest not covered by the academic literature. The keywords used were youth in agriculture, interest in agribusiness, perception in agribusiness and participation in agribusiness. Relevant databases like African Journals Online (AJOL), Google, Google scholar and SCOPUS were used for the literature search. The reference period for the literature study is 2005 and 2022. This enhanced the collection of data for at most two decades. The following combination of search strings was used:

Search strings:

String 1: Youth AND Africa

String 2: Youth AND Agriculture AND African

String 3: Youth in Africa OR perception OR agriculture OR agribusiness

String 4: Youth in Africa OR participation OR agriculture OR agribusiness

String 5: Youth in Africa OR interest OR agriculture OR agribusiness

String 6: Factor that hinders OR Youth in Africa OR participation OR agriculture OR agribusiness

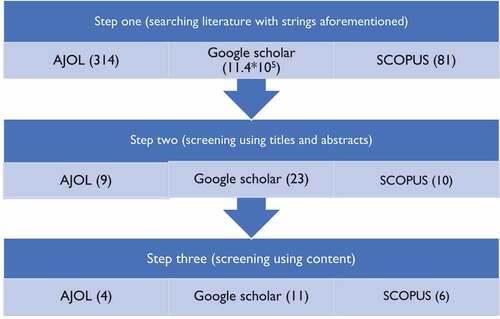

Selection of literature were in three parts. The first step was the searching of literature with the string aforementioned. Various search engines generated different results; 314 for AJOL, 11.4 × 105 for google scholar and 81 for SCOPUS. After the first screening of literature with the aforementioned strings, titles and abstracts were screened as the second step (Figure ). About 9, 23 and 10 literatures were selected for AJOL, Google scholar and SCOPUS respectively. After reading the content form screening 21 literature were chosen from the various search engines. These 21 literature articles came from AJOL (4), google scholar (11) and SCOPUS (6) (Figure ).

3. Theoretical and conceptual framework

The push-pull theory, the theory of reasoned action and the utility maximisation theory all affect youth’s participation in agribusinesses (Maritim, Citation2020). Under the push-pull theory, incidence like unemployment pushes the youth to go into agripreneurship and issues like high profitability and enabling environment to push the youth into the agribusiness sector (Figure ). The theory of reasoned action relates perception, interest and attitude to the information available to an individual. Utility maximization looks at the available choices a youth has and the choice that best satisfies his ambitions.

4. Conceptual definition of attitude, perception and intention

When there is a stimulus, a person’s receptiveness to the stimuli largely depends on his beliefs, attitudes, motivation and personality (Pickens, Citation2005). When a person selects a certain stimulus, there is registration of the stimuli in the mind. The person then organizes the stimuli based on prior experience. Interpretation of the stimuli then results in either a positive or negative perception.

Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information or stimuli to represent and understand the presented information, or the environment. A person can interpret the stimuli based on prior experience. Interpretation can however be different from reality. Research on perception consistently demonstrates that individuals may look at the same thing yet their understanding may differ. Perception deals with the general understanding of people. One’s perception can be biased or ambiguous due to misunderstanding.

Intention is one’s readiness to undertake a certain activity or event. Intention for the youth to venture into agribusiness is the readiness of the youth to venture into the agripreneurship or work in the agriculture sector (Umar, Citation2019). Also, attitude is the behaviour of interest. When there is a change in an environmental condition the interest of the youth is the attitude.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Interest, perception and participation of youth in agribusiness in the various countries in Africa

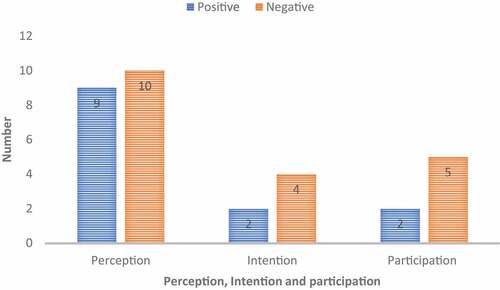

Out of the 21 documents reviewed, 19 studies presented findings on perception, 6 studies presented findings on intention and 7 studies presented findings on participation (Figure ). Details is found in Table A1.

10 documents showed a negative perception of the youth with regard to agribusiness and 9 documents showed a negative perception of the youth with regard to agriculture (Figure ). The studies reviewed show the youth generally have a negative perception with regards to agribusiness. Negative perception influences intention and participation in agribusiness (Henning et al., Citation2022).

5.2. Perception of youth in terms of profitability of the business venture

About 6 (Henning et al., Citation2022; Kaki et al., Citation2022; Magagula & Tsvakirai, Citation2020; Maritim, Citation2020; Obisesan, Citation2019; Zidana et al., Citation2020) out of 9 studies mention that youth perceive agribusiness to be profitable. A venture’s profitability drives a rational investor’s interest and participation. The youth in Malawi and Kenya perceive agriculture to be profitable (August, Citation2020; Kaki et al., Citation2022). This explains the reason for the choice of agriculture as a career in the future (Henning et al., Citation2022; Magagula & Tsvakirai, Citation2020). The youth can be encouraged to go into agribusiness when programmes target the profitability of the agribusiness industry (FAO and AUC, Citation2022).

About 5 (August, Citation2020; Brooks et al., Citation2013; Losch, Citation2016; Njeru, Citation2017; Sumberg et al., Citation2017) out of the 10 studies mention that the youth do not perceive agriculture to be profitable. Unprofitability in the agriculture sector prevents the youth from venturing into agriculture (Heifer International, Citation2021). In Ghana, the unemployed youth do not want to go into agriculture because they found it unprofitable and risky when they first ventured into the industry; they were mostly unpaid hands help on the farm (Wuni et al., Citation2017). Profitability is a key determinant that influences the perception of the youth in agribusiness.

5.3. Perception of agriculture as a career job

Agriculture is not perceived as a full-time job as it is seen as a low-status profession by the youth in different countries in Africa (Maritim, Citation2020; Njeru, Citation2017). In Ghana, the unemployed youth look for other jobs instead of agriculture (Heifer International, Citation2021). Even among undergraduate students, less than half of the respondents mentioned their interest in engaging in agripreneurship in Benin (FAO and AUC, Citation2022). The formal sector where the youth mostly look for jobs have fewer vacancies. This pushes the youth to go into agriculture; there is no alternative job to look at as they are mostly unemployed (Brooks et al., Citation2013; Maritim, Citation2020). This explains why the unemployed youth in Ghana sees the agriculture industry as a future industry to venture into (Brooks et al., Citation2013). The youth see a promising future career in agriculture (August, Citation2020).

6. Influence of youth perception, intention and participation in agribusiness in various countries

6.1. Access to land

About 3 (Bezu & Holden, Citation2014; Heifer International, Citation2021; Obisesan, Citation2019) out of 5 studies in the literature found out the non-participation of the youth in agribusiness was due to the inaccessibility of land. Youth in Ghana do not have the intention to go into agriculture due to a lack of land (Martinson et al., Citation2019). 2 out of 5 studies on the negative perception of youth with regards to agribusiness relate it to the inaccessibility of land.

In DRC Congo, the intention to be an agripreneur starts when one has access to land (Martinson et al., Citation2019). This is because the land is the basic resource for farming and setting up a business. Challenges in securing land pose a great barrier to the engagement of the youth in agribusiness. Sources of securing land include purchases and inheritance. The youth perceive that prices of land are high in Malawi (Kaki et al., Citation2022) preventing the youth from participating in agriculture and agribusiness. Even when land is inherited, there are challenges. People perceive that family lands, which are the most dominant means of acquiring land by the youth (Brooks et al., Citation2013) are subdivided making it difficult for the youth in Malawi and Kenya to engage in viable agribusiness ventures (Kaki et al., Citation2022; Maritim, Citation2020). Most youths in Africa do not have access to land (USAID, Citation2017). Even the few who have access to land have to do so by inheritance. Land, however, did not affect the participation of the youth in agriculture in 2 (Henning et al., Citation2022; Sumberg et al., Citation2017) studies.

6.2. Access to finance

2 (Heifer International, Citation2021; Wole-Alo & Olaseinde, Citation2016) out of 10 studies found that the youth perceived that finance is inaccessible with regard to agriculture. Lack of access to finance prevents the youth in Ghana from going into agribusiness. 3 (Heifer International, Citation2021; Henning et al., Citation2022; Wole-Alo & Olaseinde, Citation2016) out of 6 studies mention the non participation of youth in agriculture is due to access to finance. Access to finance was the highest challenge for the participation of youth in many parts of Africa (Heifer International, Citation2021). This was due to high-interest rates, short payment duration and collateral required to access loans. In Ghana, the majority of the unemployed youth who were previously in agriculture stop the venture as a result of a lack of access to finance (Brooks et al., Citation2013). Access to finance from the presentation of business plans helps the student to aspire to be an entrepreneur (Isaacs et al., Citation2017).

There are however contrary studies that show that access to finance reduces the intention of the youth to engage in agribusiness in DRC Congo (Kaki et al., Citation2022). This was because the youth have other non-agriculture ventures, they can invest in.

6.3. Education, skills and capacity building

3 (Bello et al., Citation2021; Chipfupa & Tagwi, Citation2021; Heifer International, Citation2021; Njeru, Citation2017) out of 10 studies mentioned that education leads to a negative perception of agriculture. Education that is not related to agriculture reduces the participation of youth in various countries (Njeru, Citation2017). People in higher learning have a negative perception of agriculture and agribusiness in Malawi (Kaki et al., Citation2022). People who are in school do not get the time to participate in agriculture (Brooks et al., Citation2013). The formally educated reduce participation in agriculture as compared to the illiterate (Kalule et al., Citation2017; Martinson et al., Citation2019). This might be because agriculture is not part of the curriculum of the students at the basic and secondary levels (World Bank, Citation2016). Even in institutions where agriculture is a programme at the undergraduate level, students are not equipped with the skills to set up their businesses (Kalule et al., Citation2017) as education is mainly theoretical (Haggblade et al., Citation2015). The rural youth who are educated are however interested in agriculture and agripreneurship (Martinson et al., Citation2019; Mmbengwa et al., Citation2021).

In Malawi, people perceive that the youth do not have adequate skills to engage in agriculture (Kaki et al., Citation2022). In order to change the mindset of the youth to the agriculture sector, training is crucial (Bello et al., Citation2021). Skills are the most important factor youth consider when engaging in the agriculture sector (Maritim, Citation2020). The youth however do not have adequate skills, knowledge and information to engage in agriculture (Kaki et al., Citation2022). ATVET institutions look more at the education aspect than the agriculture aspect (Hawkins, Citation2021). The youth are not exposed to practical skills during school (Itangishatse & Ndihokubwayo, Citation2019). Meanwhile, exposure to practicals and internship help the youth to be innovative entrepreneurs (Turolla, Citation2019). Theories may be complemented with practicals in motivating the youth to be agripreneurs (Njeru, Citation2017). Aside from practicals, there should be an internship with the industry to inspire the innovation of students.

The youth claim that motivation from teachers encourages them to venture into entrepreneurship (Obibuba & Udujih, Citation2020). Lecturers in ATVET institutions are mostly graduates with less experience (Kalule et al., Citation2017) and are poorly trained (Isaacs et al., Citation2007). This explains why even in ATVET institutions where the mandate is to equip students with skills to be able to be entrepreneurs, these skills gained are not put into use by a majority of people as they seek for others to employ them (Mengistu, Citation2017). Exposure to skills like business plans (USAID, Citation2017) motivates people to be entrepreneurs. Also, the provision of enabling materials by the educational institution enhances skills in entrepreneurship (Obibuba & Udujih, Citation2020).

6.4. Access to technology

4 (Bello et al., Citation2021; Heifer International, Citation2021; Henning et al., Citation2022; Sumberg et al., Citation2017) out of 10 studies mentioned that the youth have a negative perception of agribusiness due to the lack of technology being used. The lack of technology in the agribusiness sector might be the reason why the youth mentioned agriculture is for the poor and old (Henning et al., Citation2022; USAID, Citation2017). Those who are in the agriculture industry thus have a low status in society (Henning et al., Citation2022; Njeru, Citation2017; Sumberg et al., Citation2017). 1 (Bello et al., Citation2021)26 out of 4 studies on intention mentioned the youth did not have the intention to venture into agriculture production due to the tedious nature of agriculture associated with lack of use of technology.

In Malawi, one critical factor to engage the youth in development is technology (Anyidoho et al., Citation2012). In Ghana, most unemployed youths do not want to participate in agriculture as a result of rudimentary tools like hoe and cutlass used in farming which makes agriculture work tiring (Sumberg et al., Citation2017). The illiteracy nature of farmers prevents their use of technology (Heifer International, Citation2021). Technology is looked at in terms of ICT and the modernization of agriculture.

Technology motivates the youth to go into agriculture (Kwakye et al., Citation2021). This is because technology improves access to the youth and the available information on access to funds and knowledge to venture into the industry (Okunola, Citation2014). The youth can easily access information on programmes and access to funds and resources through technology. Also, the youth do not want to use rudimentary tools in farming (Heifer International, Citation2021)6 as they find their use as labourious (Itangishatse & Ndihokubwayo, Citation2019). They would want to use tractors, harrowers and ploughs to increase productivity. The youth is thus perceived as someone who uses technology in his agricultural activities (Turolla, Citation2019). This is evident as 90% of farmers ages 18 to 35 in Kenya have high levels of engagement with information and communication technology (Itangishatse & Ndihokubwayo, Citation2019).

6.5. Influence of parents, relatives and peers on youth engagement in agriculture in Africa

About 3 (Itangishatse & Ndihokubwayo, Citation2019; Maritim, Citation2020; Martinson et al., Citation2019) out of 9 studies mentioned that parents supported agriculture; this has motivated them to have a positive perception of agriculture. In South Africa, some youth have the intention to go into the agribusiness industry because their parents would support them financially (Magagula & Tsvakirai, Citation2020). About 1 (Henning et al., Citation2022) out of 2 studies on the participation of youth mentioned that in South Africa, the youth are participating in agriculture because of their parent’s support of the sector. About 98% of the youth who were into agriculture were exposed to agriculture by their parents in Kenya (Maritim, Citation2020). Most youth venture into agriculture because their families have experience in agriculture (Obibuba & Udujih, Citation2020). Young agripreneurs can become role models for their mates to follow through to venture into agribusiness (USAID, Citation2017).

About 1 (Brooks et al., Citation2013) out of 10 studies on the negative perception of the youth in agriculture mentioned that working on a family farm has generated a negative perception of agriculture. In Ghana, the youth who are unemployed show disinterest in agriculture (Brooks et al., Citation2013). This is because they mostly work as unpaid workers accompanying their parents to the farm. This might explain why families that are into agriculture do not encourage their children to venture into farming (Njeru, Citation2017; Obibuba & Udujih, Citation2020).

7. Conclusion and recommendation

The youth in Africa mostly have a negative perception with regard to agriculture. This influences their intention and participation in Agriculture. There is a lack of access to land; finance; technology; and education and skills in agribusiness. There are however mixed findings on access to finance and its influence on the engagement of the youth in agriculture. More studies should look at the influence of access to finance and other resources on youth engagement in agriculture.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the EU Talking Agribusiness in Liberia project for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jacqueline Ninson

Jacqueline Ninson is an agricultural research expert with 7 years of working experience in active and practical research. She has served as a research and graduate assistant at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology- Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness, and Extension where she assisted agribusiness and agricultural economics students to research relevant areas in the agricultural value chain in Ghana. She has conducted various research in the agriculture value chain and has 8 papers published in reputable journals. She has also been a reviewer of 5 papers from different continents of the world. In the input sector, she has researched the use of land. Additionally, she has conducted various profitability research. Jacqueline additionally has experience in Research Methodology, Agricultural Statistics, Agricultural Marketing, and International Trade as she has taught these courses for about 5 years at the Kumasi Institute of Tropical Agriculture. She has prior experience in using demand-driven approaches to engage various actors in the aforementioned value chains for research and capital mobilization. Her expertise was instrumental in coordinating donor-funded projects such as Cassava Transformation Project and Talking Agri-business all funded by the European Union. Jacqueline holds both BSc and M.Phil. in Agribusiness.

Maame Kyerewaa Brobbey

Maame Kyerewaa Ms. Brobbey is a social science researcher and community engagement expert with 13+ years of experience in socio-economic research, gender and social inclusion (GESI) programming and implementation, and project management. Ms. Brobbey is a trained gender and development anthropologist with an MPhil degree in African Studies with verifiable research analysis, writing, and presentation skills. She has expertise in women and young people’s rights issues, agri-/food value chains (including cowpea, groundnut, cassava, mango, and vegetables), and informal economies. She provides technical support to the King Baudouin Foundation-funded Mango Project and has coordinated the design and conduct of a mango value chain baseline study across 5 districts in Southern Ghana. Ms. Brobbey also leads research in agri-/food value chains in Liberia. As the Gender, Research & Policy Advisor for CDO, she led research teams to conduct respective studies on the gendered financial inclusion and adoption of social protection among fisherfolks in coastal communities in Ghana in the context of the EU-funded Power to the Fishers project and presented the key findings from these studies at a learning workshop organized by CDO. She also supported the conduct of research on groundnut and cowpea value chains in Northern Ghana, and the impact of COVID-19 on urban vegetable farming in Accra. In the past, she has conducted research and analysis of gender-based violence for women’s rights organizations including the Women’s Human Rights and Gender Section of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Geneva, and the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, Johannesburg. She also coordinated ten-country project teams and led the Ghana case for the African Presidential Papers and Libraries research project funded by the Open Society Initiative for West Africa. Additionally, she has worked with the Pathways of Women's Empowerment Consortium in the analysis of women’s empowerment across different economic sectors in Ghana. With her expertise, she will also be responsible for mainstreaming gender and social inclusion issues in the study as well as conducting analysis to unearth critical variables for the behavior of different market actors in the target environment.

References

- Anyidoho, N. A., Kayuni, H., Ndungu, J., Leavy, J., Sall, M., Tadele, G., & Sumberg, J. (2012). Young people and policy narratives in sub-Saharan Africa.

- August, M. M. (2020). Youths’ aspirations and perceptions towards agricultural participation: a case of two Free State regions (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State).

- Bednaříková, Z., Bavorová, M., & Ponkina, E. V. (2016). Migration motivation of agriculturally educated rural youth: The case of Russian Siberia. Journal of Rural Studies, 45, 99–14.

- Bello, L. O., Baiyegunhi, L. J. S., Mignouna, D., Adeoti, R., Dontsop-Nguezet, P. M., Abdoulaye, T., & Awotide, B. A. (2021). Impact of youth-in-agribusiness program on employment creation in Nigeria. Sustainability, 13(14), 7801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147801

- Bezu, S., & Holden, S. (2014). Are rural youth in Ethiopia abandoning agriculture? World Development, 64, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013

- Blattman, C., & Annan, J. (2011). Reintegrating and employing high risk youth in Liberia: Lessons from a randomized evaluation of a landmine action an agricultural training program for ex-combatants.

- Breisinger, C., Diao, X., Thurlow, J., & Al-Hassan, R. M. (2008). Agriculture for development in Ghana: New opportunities and challenges.

- Brooks, K., Zorya, S., Gautam, A., & Goyal, A. (2013). Agriculture as a sector of opportunity for young people in Africa (pp. 64–73). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

- Bruno, L. 2016. Structural transformation to boost youth labour demand in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of agriculture, rural areas and territorial development. International Labour Organization, 65 p. (Employment Working Paper, 204)

- Chipfupa, U., & Tagwi, A. (2021). Youth’s participation in agriculture: A fallacy or achievable possibility? Evidence from rural South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v24i1.4004

- Elferink, M., & Florian, S. (2016). Global demand for food is rising. Can we meet it? Harvard business review. Date accessed 21/4/2019

- FAO and AUC. (2022). Investment guidelines for youth in agri-food systems in Africa. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9001en

- Haggblade, S., Chapoto, A., Drame-Yayé, A., Hendriks, S. L., Kabwe, S., Minde, I., Terblanche, S. … Terblanche, S. (2015). Motivating and preparing African youth for successful careers in agribusiness: Insights from agricultural role models. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 5(2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-01-2015-0001

- Hawkins, R. (2021). Agricultural Technical and Vocational Education and Training (ATVET) in Sub-Saharan Africa: Overview and integration within broader agricultural knowledge and innovation systems. https://www.nlfoodpartnership.com/documents/112/ATVET_review_complete_26Feb21.pdf

- Heifer International. (2021). The future of Africa’s agriculture - an assessment of the role of youth and technology. https://media.heifer.org/About_Us/Africa-Agriculture-Tech-2021.pdf

- Henning, J. I., Matthews, N., August, M., & Madende, P. (2022). Youths’ perceptions and aspiration towards participating in the agricultural sector: A South African case study. Social Sciences, 11(5), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050215

- IFAD. (2005). A review of cassava in Africa with country case studies on Nigeria, Ghana, the United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda and Benin. Proceedings of the Validation Forum on the Global Cassava Development Strategy (Vol. 2). Rome.

- Isaacs, E., Visser, K., Friedrich, C., & Brijlal, P. (2007). Entrepreneurship education and training at the Further Education and Training (FET) level in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 27(4), 613–629.

- Isaacs, E., Visser, K., Friedrich, C., & Brijlal, P. (2017). Entrepreneurship education and training at the Further Education and Training (FET) level in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 27(4), 613–629.

- Itangishatse, J., & Ndihokubwayo, K. (2019). Developing achievement and interest in learning entrepreneurship in Rwanda: An action research field trip. LWATI: A Journal of Contemporary Research, 16(1), 1–13.

- Janzen, T. (2014). Environmental. Legal news rooms. https://www.lexisnexis.com/legalnewsroom/environmental/b/environmentalregulation/posts/the-challenges-facing-liberian-agriculture

- Kaki, R. S., Mignouna, D. B., Aoudji, A. K., & Adéoti, R. (2022). Entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate agricultural students in the Republic of Benin. Journal of African Business, 24(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2022.2031584

- Kalule, S. W., Mugonola, B., & Ongeng, D. (2017). The student enterprise scheme for agribusiness innovation: A University-based training model for nurturing entrepreneurial mind-sets amongst African youths. African Journal of Rural Development, 2(1978–2017–1973), 55–66.

- Kwakye, B., Brenya, R., Cudjoe, D., Sampene, A., & Agyeman, F. (2021). Agriculture Technology as a tool to influence youth farming in Ghana. Open Journal of Applied Sciences, 11, 885–898. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojapps.2021.118065

- Magagula, B., & Tsvakirai, C. Z. (2020). Youth perceptions of agriculture: Influence of cognitive processes on participation in agripreneurship. Development in Practice, 30(2), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1670138

- Maritim, K. D. (2020). Assessment of Factors Influencing Youth Participation in Agri-Business in Kericho County, Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, KeMU).

- Martinson, A. T., Yuansheng, J., & Monica, O. A. (2019). Determinants of agriculture participation among tertiary institution youths in Ghana. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 11(3), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.5897/JAERD2018.1011

- McMullin, J. R. (2022). Hustling, cycling, peacebuilding: Narrating postwar reintegration through livelihood in Liberia. Review of International Studies, 48(1), 67–90.

- Mengistu, M. (2017). Graduate employability as a function of career decision in the Amhara State TVET system. Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, 13(1), 1–21.

- Mmbengwa, V. M., Qin, X., & Nkobi, V. (2021). Determinants of youth entrepreneurial success in agribusiness sector: The case of Vhembe district municipality of South Africa. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1982235. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1982235

- Muthomi, E. (2017). Challenges and opportunities for youth engaged in agribusiness in Kenya. Journal of Culture, Society and Development, 17(1), 4–19.

- Njeru, L. K. (2017). Youth in agriculture; perceptions and challenges for enhanced participation in Kajiado North Sub-County, Kenya. Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 7(8), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJAS.2017.8.100117141

- Obibuba, I. M., & Udujih, N. V. (2020). Teaching and learning of entrepreneurial studies in junior secondary schools in Onitsha North Education Zone. International Journal of Educational Research, 7(1), 108–119.

- Obisesan, A. A. (2019). What drives youth participation and labour demand in agriculture? Evidence from rural Nigeria.

- Okunola, A. (2014). Towards Sustainable Youth Engagement with African Agriculture: Challenges and Strategies. African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific - AFSAAP 36th Annual Conference – Perth – Australia – 26-28 November 2013 Conference Proceedings. Perth – Australia.

- Pickens, J. (2005). Attitudes and Perceptions Learning Outcomes. Manangement of employess of the health service organisation (1 ed., pp. 43–76). Virginia.

- Project, B. (2014). Furthering the development of sustainable agriculture in Liberia. Agriculture, Global Poverty.

- Sumberg, J., Yeboah, T., Flynn, J., & Anyidoho, N. A. (2017). Young people’s perspectives on farming in Ghana: A Q study. Food Security, 9(1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-016-0646-y

- Swarts, M. B., & Aliber, M. (2013). The ‘youth and agriculture’ problem: Implications for rangeland development. African Journal of Range & Forage Science, 30(1–2), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.2989/10220119.2013.778902

- Turolla, M. (2019). Youth in Agribusiness in Uganda. An Ethnography of a Development Trend (Doctoral dissertation.

- Umar, S. (2019). Developing a research framework for youth engagement in agripreneurship: Application of the theory of planned behaviour. Nigerian Journal of Rural Sociology, 19(1).

- USAID Feed the Future Programme. (2017) Engaging African Youth In Agriculture. https://www.feedthefuture.gov/article/making-agriculture-cool-again-for-youth-in-africa/#:~:text=Agriculture%20is%20currently%20perceived%20by%20many%20young%20Africans,into%20this%20nearly%20trillion%20dollar%20industry%20in%20Africa

- Wole-Alo, F. O., & Olaseinde, A. T. (2016). Assessing the future of agriculture in the hands of rural youth in oriade local government area of osun state, Nigeria. International Journal of Agricultural Extension, 4(2). 105–110.

- World Bank. (2016) . Liberia skills development constraints for youth in the informal sector.

- Wuni, I. Y., Boafo, H. K., & Dinye, R. D. (2017). Examining the non-participation of some youth in agriculture in the midst of acute unemployment in Ghana. International Journal Modern Societies Science, 6(1), 128–153.

- Yami, et al (2018). African Rural Youth Engagement in Agribusiness: Achievements, Limitations, and Lessons; Mercy Corps. Liberian Youth Reflect on Agriculture Livelihoods.

- Zidana, R., Kaliati, F., & Shani, C. (2020). Assessment of Youth engagement in agriculture and agribusiness in Malawi: Perceptions and hindrances. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Management, 9(1), 19.

Appendix

Table A1. Table on the perception of the youth

Table A2. Table on the intention of the youth in engaging in agribusiness

Table A3. Table on the participation of the youth in engaging in agribusiness