?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Protest behaviour has been conceptualized as a high-risk form of political engagement, and it tends to elicit a relatively lower engagement rate than other forms of political participation. In Africa, the risky nature of protests is often complicated by the predominant socio-cultural bias and masculine political norms that hinder women’s political agency. Many of these political systems in Africa are emerging democracies, where women are likely to be marginalized in the civic and political sphere. Using the Afrobarometer data of 2014/2015, this study seeks to examine the impact of the political context on the gender gap in protest behaviour. The study finds that the gender gap in protest behaviour is lower in countries that are politically free and higher in countries with more years of military regimes. These findings offer valuable insights into the political and institutional contexts in which women’s protest behaviour is accentuated and diminished.

1. Introduction

Protests are regarded as an effective form of mass mobilization in many nations (Dalton et al., Citation2009), and women have played integral roles in various protest movements in different parts of the world, especially in countries in the global South (Allam, Citation2018; Baldez, Citation2002; Borland & Sutton, Citation2007; Corcoran-Nantes, Citation1997; Hsiung, Citation2001; McCarthy, Citation2015; Puglise, Citation2017; Viterna, Citation2006). Through protests and activism, women use their socio-cultural status to make claims from the political realm as a means of expressing themselves and advancing the emancipation of their agency (Allam, Citation2018; Baldez, Citation2002; Hsiung, Citation2001). Women’s engagement in protest movements also reveals their capacity to reframe and harness cultural norms about their humanity to make claims on the state and society (Baldez, Citation2002; Hsiung, Citation2001).

Protest behaviour has been conceptualized as a high-risk form of political engagement, and it tends to elicit a relatively lower engagement rate than other forms of political participation (Harris & Hern, Citation2019; McAdam, Citation1986; Schussman & Soule, Citation2005). Several studies have shown the impact of political beliefs, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, income, political interest, organizational ties, age, and gender on protest behaviour (Caren et al., Citation2011; DiGrazia, Citation2014; McAdam, Citation1986; Schussman & Soule, Citation2005). A multilevel analytical study of 78 nations by Dalton et al. (Citation2009) revealed that the level of political development in a country significantly influences the level of protest. However, the study did not determine if the impact of the political context on protest behaviour is the same or different for men and women.

In Africa, the relatively risky nature of protest is further complicated by the gender-bias against women protesting, as women’s political agency is often perceived as a deviation from masculine political norms (Gottlieb, Citation2016). To date, few studies have been conducted on African women’s political participation that (1) look beyond the individualistic factors of women’s political behaviour (see Andrew, Citation2018; Bawa & Sanyare, Citation2013; Bratton, Citation1999; Gordon, Struwig, Roberts, et al., Citation2019), and (2) account for the political context of women’s political agency (see Barnes & Burchard, Citation2012; Coffe & Bolzendahl, Citation2011; Isaksson, Kotasadam & Nerman, Citation2014; Hern, Citation2018). Thus, given the relatively high-risk nature of protest behaviour and the male-dominated nature of contentious politics in Africa, it is important to know the political context in which women engage in protest actions. For Schussman and Soule (Citation2005), it is essential to connect individual factors to the social and political contexts when seeking to gain further insights into the process of taking part in protest movements. This study employs a multilevel analytical approach to examine how contracting or expanding political structure impacts women’s protest behaviour in Africa. This study will address the following question: How do open or closed political systems differentially affect women’s protest behaviour relative to men in Africa? This study contributes to the literature by inquiring into the political context in which women’s political agency is diminished or attenuated. Women’s political agency is also consequential for the democratization of the kinds of (emerging) democracies in most African countries. Democratization implies that everyone, including marginalized groups, needs to be involved in their governance, and protesting represents an important avenue of engaging with the state.

The paper structure is as follows: the next section of this paper examines the theoretical framework of the study. I also discuss the literature on women’s realities in African democratic countries. Next, I lay out the methodological perspective of the paper; this includes the nature of the dataset, the different measures for the outcome, focal and control variables, and the method of analysis for the study. I provide the findings of the study, which includes the descriptive and multilevel analysis of the study. I discuss the nature of the results, limitations of the data, and implications of the study to conclude the paper.

1.1. Gender, political context and political behaviour

When collective action and politics are integrated, the state and different power interests often come into play (Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015). Political opportunity structures (POS) refer to the political context in which the political agency of a citizenry is either actualized or hindered (McAdam, Citation1996; McAdam & Tarrow, Citation2019; Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015). For McAdam and Tarrow (Citation2019), the internal features of a social movement can be channelled through an enabling political context that informs not only the directions they take but also the disposition of actors to determine the path(s) of collective action and mobilization. POS offers claim-makers either openings to advance their claims or threats and constraints that discourage them from making these claims (McAdam, Citation1996; Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015). A conducive political environment can enable individuals to transform their socio-economic resources, such as educational attainment, income, political skills, among others, into political action (Dalton et al., Citation2009). Two of the dimensions of the POS that are vital for understanding social movements in emerging democracies are the openness of the polity to claim-makers and the state’s capacity and propensity for repression (McAdam, Citation1996). These two dimensions are likely to be more visible in growing democracies in which political ideologies on socio-political and economic issues have yet to crystallize and in which political structures are relatively unstable.

The openness of the polity to new actors and the state’s propensity for repression generally captures how open or closed the system is to claim-makers. Countries with higher levels of political openness have higher levels of political participation (Dalton et al., Citation2009; McCammon et al., Citation2001; Pilati, Citation2011; Vráblíková, Citation2014). Conversely, studies in Africa and Central America have found that repressive contexts represent a high deterrent for protest behaviour (Booth & Bayer, Citation1996; Pilati, Citation2011). Repressive states with strong military infrastructures typically reduce the effect of collective action (Ortiz, Citation2007). These two variables tend to be inversely correlated as more open political contexts have less repressive regimes, especially with political participation (Pilati, Citation2011). A study by Banaszak et al. (Citation2021) found that countries with higher levels of gender equality have lower gender gaps in protesting. In this sense, both variables capture the extent to which a political system is open and its impact on women’s political agency.

Two general arguments have been made regarding the association between political context and political participation. On the one hand, an open political system creates the platform for individuals to make claims from the state and criticize state actions and policies without the fear of reprisal or oppression (Dalton et al., Citation2009; McAdam & Tarrow, Citation2019; Mlambo & Kapingura, Citation2019; Pilati, Citation2011). Open countries reduce the formal and informal barriers that restrict women’s access to political power, and they also allow different channels of information that encourage women to make claims on the state (Molyneux, Citation2002). Political parties in democratic states are more likely to be inclusive of gender issues, as they are aware of possible consequences of non-inclusion (Patterson, Citation2000). Different studies have shown that increased democratization is positively associated with women’s access to political power in Tanzanian, Uganda, and South Africa (Brown, Citation2001; Hassim, Citation2003; Ottemoeller, Citation1999; Tripp, Citation2006). Institutionally gendered contexts stimulate women’s political agency as their political engagement improves in egalitarian societies (Mlambo & Kapingura, Citation2019). Another study found that the longer women have had formal suffrage, the smaller the gap between women’s and men’s participation in collective action and political contact (Coffe & Bolzendahl, Citation2011). Also, the duration of high-quality democracy improves women’s political participation (Hern, Citation2018). A study by S. S. Liu and Banaszak (Citation2017) noted that the presence of women in the presidential cabinet has a positive impact on women’s protest behaviour. Even the presence of female leaders can stimulate women’s desire to engage with their political leaders (Iyer & Mani, Citation2019; Robinson & Gottlieb, Citation2019). Thus, one can assume that African countries that are more democratic, free, and have allowed more women into political offices and their legislature would be more tolerant of women engaging in protests.

On the other hand, it has also been argued that closed political systems tend to push individual actors outside the traditional channels of claim-making, which, in turn, can lead to increasing levels of collective action (Brockett, Citation1991; Cuzan, Citation1991; Kitschelt, Citation1986; Lu & Yang, Citation2019). In terms of gender and political participation, Yoon (Citation2001) found that overall democratization depressed women’s political representation in Africa. A study of women’s parliamentary representation in Africa by Stockemer (Citation2011) found that transitions to democracy were negatively associated with women’s political representation. Furthermore, gender gaps in unconventional forms of political activity are lower in repressive regimes than in open political systems (Desposato & Norrander, Citation2009). One can therefore assume that African countries that are less democratic and free and that restrict women’s access to political offices and their legislature can inadvertently stimulate women’s protest behaviour. These debates show the dynamic nature of political context and collective action, and it would be interesting to examine how the political context informs protest behaviour among African women.

1.2. Women, democracy, and political agency in Africa

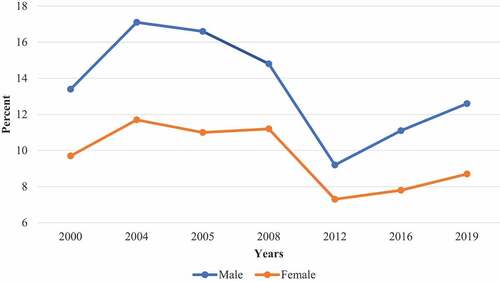

Most of the countries in Africa are emerging democracies. Apart from Liberia, Egypt, and Ethiopia, many African countries gained political independence between 1956 and 1968. This period coincided with the decolonization wave of the mid-1950s (Gifford & Louis, Citation1988; Hargreaves, Citation1996; Hatch, Citation1967) and the global recognition of “the third world.” After this wave, different African countries had to grapple with the complexities of political independence, democratization, and inclusive governance. Although women had played a vital role in the decolonization process in most African nations, they were left out of the political process after political independence (Asiedu, Citation2019; Azikiwe, Citation2010; Tripp, Citation2019). Their exclusion is evident in the relatively low rates of female representation in the government in many post-independence African countries, a phenomenon that persists today. The lack of female representation in the polity is also reflected in the gender gaps in political participation in Africa (Barnes & Burchard, Citation2012; Hern, Citation2018). For instance, the Afrobarometer website indicates shows that there has been a significant gender gap in protest behaviour since the late 1990s (see Figure ). This analysis reflects the masculine-oriented socio-political culture in most African societies (Bawa & Sanyare, Citation2013; Evans, Citation2016; Gottlieb, Citation2016), where women are often left behind in the political process.

Some of the crucial social movements that have affected significant socio-political changes in African society have involved women organizing themselves and expressing their political agency through mass protests. These include those who participated in the Aba women’s riot of 1929 in Nigeria, the Abeokuta women’s revolt in 1946 (both against the imposition of unfair taxes by the colonial government), the women’s march on Pretoria in 1956 (in opposition to the pass laws for women), Mass Action for Peace by Liberian women in 2003 (seeking to end the Second Liberian civil war), the Bring Back Our Girls Campaign in Nigeria in 2015 (which protested the kidnapping of about 250 girls from Chibok, Borno State by Boko Haram), and the naked protest (which called for a change to the university’s rape policy) at Rhodes University in South Africa in 2016. Most of these social movements in Africa have centered their political demands on challenging the legitimacy of the state and reacting to the consequences of state policies and patriarchal structures on women’s humanity and wellbeing. Some of these movements have also shown women’s capacity to bridge political division and mend relations across different communities (Berger, Citation2014).

In most African nations, however, women’s engagement is seen as a deviation from the prevailing socio-cultural norms of politics (Bawa & Sanyare, Citation2013; Gottlieb, Citation2016). The predominant masculine norm suggests that the political realm is not a place for women (Bawa & Sanyare, Citation2013). Due to the influence of these socio-cultural norms, women who engage in politics are at the risk of social sanctions. Women’s lack of engagement in protests has also been found in the Middle East, North Africa, and Asian (Fakih & Sleiman, Citation2022; S. Liu, Citation2022). As Gottlieb (Citation2016) suggests, women tend to restrict themselves from future political participation because men create hindrances to their participation in forms of backlash. The majority of studies on African women’s political participation have examined the role of socio-cultural factors on women’s political participation, including gender roles, the presence of women’s social movements, recognition of gender equality, the extent of political interest, and cognitive awareness of politics (Andrew, Citation2018; Adeniyi-Ogunyankin, Citation2014; Bawa & Sanyare, Citation2013; Bratton, Citation1999; Gordon, Struwig, Roberts, et al., 2019; Iwara et al., Citation2018; Lindberg, Citation2004). However, it is important to understand how political and institutional contexts shape these individual-level factors.

A few studies have examined the importance of institutional context for women’s political participation in Africa (Barnes & Burchard, Citation2012; Coffe & Bolzendahl, Citation2011; Isaksson, Kotasadam & Nerman, 2013; Hern, Citation2018; Hughes & Tripp, Citation2015; Stockemer, Citation2011). However, equally critical is the political context where African women reside and how it shapes their political agency, especially for high-risk forms of political engagement. Few studies have investigated protests as a form of political action (McAdam, Citation1986; Schussman & Soule, Citation2005) and how protesting intersects with cultural gender-bias against women (Gottlieb, Citation2016). Thus, this study seeks to add to the literature by exploring the specific political-institutional contexts that activate or deactivate women’s protest behaviour in Africa. The choice of Africa enables one to understand how the dynamics of the political context inform women’s engagement with the state. This study contributes nuanced insights into the literature, which is dominated by the studies of Western democracies and other regions. Given the variegated nature of political freedoms in the African continents, it is important to understand how such varying levels of political context inform political behaviour of the average African woman.

1.3. Data and analytical sample

This study analyzes the 6th round of the Afrobarometer multi-country dataset based on national probability samples representing cross-sections of adult citizens (18 years and above). The multi-country dataset contains 36 countriesFootnote1 in Africa, and the data were gathered from March 2014 to November 2015. The response rate of the surveys varied between 60% to 80% for most of the countries. The lowest response rates came from Morocco and Tunisia at 38% and 30%, respectively. The total sample size from the 36 countries is 51,687. The study employed clustered, stratified, and multi-stage area probability sampling to select individuals in each country. The survey is ideal for this study because the data contain information on several socio-political topics.

1.4. Measures

1.4.1. Outcome variable

The dependent variable for this study is the engagement in protests. Respondents were asked if they have ever participated in a demonstration or protest in the past year, and the responses were recoded as “Yes = 1” and “No = 0.” It is important to note that there are other forms of protest behaviours, such as joining a boycott, signing petitions, occupying buildings, or public institutions, and strike actions (Dalton, Citation2008). However, the analysis of this study was limited to the available information on general protest within the past year in the Afrobarometer survey.

1.4.2. Country-level variables

The concept of the political context in this study would be captured by the extent to which the state is open or closed. Country-level data were gathered and merged with the individual-level information from the Afrobarometer dataset, with the countries used as a linkage. The country-specific variables captured the indicators of open or closed political structures and the capacity for state repression for this study. Also, several country-level variables were collected to capture the proportion of female legislators and ministers, and the presence of gender quotas in the constitution. The indicators of the openness of the polity include the length of years a country has been a democracy (measured as a count); the proportion of females in legislative seats (measured as a percentage); the presence or absence of gender quotas in the constitution (No = 0, Yes = 1); and the proportion of female ministers (measured as a count). I also captured the openness and closeness of the polity by the extent to which a country is free (Not Free = 0, Partly Free = 1, and Free = 2). For the state’s capacity for repression, I captured the number of years a country has been under military administration (measured as a count).

The years 2013–2014 chosen for the gathering of the country-level variables for this study. This choice was made because data collection for the countries in the Afrobarometer dataset started in March 2014. The length of time a country has been democratic was gathered from the Database of Political Institutions (DPI) (Beck et al., Citation2001). The extent to which a country has been free was captured from the freedom index compiled by the Freedom House (Puddington, Citation2013). This index is based on the political rights and civil liberties individuals experience in their country. The freedom index categorizes countries into “not free,” “partly free,” and “free,” which was the categorization used for this study. Data on the proportion of females in legislative seats were collected from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU, Citation2019, Citation2019). Data on the proportion of female ministers were gathered from the 2014 Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum WEF, Citation2014). Data on the presence or absence of gender quotas in the constitution were compiled from the World Bank online database and the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA, Citation2019).

In terms of mapping the countries by their political context, open polities were defined as countries with higher levels of democratic rule, female legislators, female ministers, fewer years or never being under military administration, the presence of gender quotas in its constitution, and being categorized as “partly free” or “free” (i.e., freedom index).

1.4.3. Focal and control variables

The focal variable for this study is gender (recoded as Male = 0, Female = 1). The analysis examined gender as the focal variable, rather than analyzing only female respondents. Male respondents were used as a point of comparison to women and to examine if the effect of political context is unique to women. Thus, using gender as a separate variable enabled this research to examine the context within which the gap between women’s and men’s protest behaviour narrows or widens. The control variables for this analysis were employment status, place of residence, age, membership in voluntary organizations, educational status, the frequency of political discussion, deprivation index, religion, and political interest. These controls have been found to predict protest behaviour in previous studies (Barakat & Fakih, Citation2021; Corcoran et al., Citation2011; Dalton et al., Citation2009; Dim & Asomah, Citation2019; Schussman & Soule, Citation2005). The log of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita of the countries, obtained from the World Bank Online database, was used as a country-level control variable.

1.4.4. Method of Analysis

Mixed logistic regression analysis was used in the multivariate analysis (Raudenbush & Bryk, Citation2002). The choice of this method is to enable one to examine the cross-national variation in protest behaviour while capturing the within-country variation among individuals in the countries. To conduct this analysis, I conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine if there is a significant variation of protest behaviour across all African countries. Second, I examined the effects of gender on protest behaviour across countries. I also added the individual-level control variables to the cross-over effects model and examined if gender remained a significant predictor of protest behaviour. After using these cross-over effects models, for the parsimonious multivariate models, I examined the interaction effects between gender and the country-level variables to identify if open or closed political structures could help in explaining the cross-national variation in the gender gaps on protest behaviour. The interaction models were used in creating predicted probabilities for the marginal effects. Adjusted marginal effects and plots were based on their corresponding mixed logistic models. Thus, Equation 1 (i.e., the individual-level model) is:

Equation 2 (i.e., the country-level model) is:

And the combined equation for the cross-level effects is:

In this sense, is the mean protest probability between the different countries,

is the average protest probability for each gender, and

is the difference in the probability for protest for each gender by the countries.

Given the inability to compare logit models, which are built into their interaction analyses (Mize, Citation2019; Mood, Citation2010), I ran an average marginal effect (AME) for gender at different levels of the contextual variables. The AME is “the average (mean) marginal effects calculated for each observation in the sample” (Mize, Citation2019, p. 86). AME has been suggested as a method to address the non-comparability problem of logistic regression across groups and models (Mood, Citation2009). AME is not affected by unobserved heterogeneity that is unrelated to the predictor variables, and this makes it capable of comparing logistic regression models (Mood, Citation2010, p. 78). AME involves estimating the first and second differences for testing the equality of the marginal effects for the contextual variables and gender on protest behaviour (Long & Freese, Citation2014; Mize, Citation2019). The analysis for the AME analysis has been documented in Table in the APPENDIX page. Furthermore, the test of multicollinearity for the multilevel is shown in Table .

Table 1. Summary statistics of variables

Table 2. Models showing the ANOVA and cross-over effects of gender and protesting

Table 3. Cross-level effects of political context, gender, and protest behaviour

Table 4. First and second differences of AME of gender, contextual variables, and protest

Table 5. Test of multicollinearityl

2. Results

As shown in , most of the respondents had attained a secondary school educational certification (42%), while relatively few respondents had received a university degree (10%). Most of the respondents were urban dwellers (58%). The average age of the respondents was 37 years. About 51% of the respondents were unemployed, and about 57% had some or a substantial interest in political issues. In terms of voluntary association membership, about 36% of the respondents were either inactive or active members of a voluntary association. About 9.7% of the respondents had engaged in protest behaviour. About 5.7% of the respondents were male protesters, and 4% were female protesters.

For the country-level variables, military administrations have ruled the African countries in this survey for an average of seven years since the countries obtained political independence. These countries have also witnessed an average of 14 years of democratic governance, demonstrating the emerging nature of the continent’s democracies. About 22% of the legislators in the surveyed African countries were women, while the proportion of female ministers was 22%. Ten of the 36 countries were categorized as politically free, and six countries were categorized as partly free, while 20 of the 36 countries were categorized as not being politically free. Furthermore, only 19 of the 36 African countries surveyed had gender quotas in their constitution.

2.1. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and cross-over effects models

In , Model 1 is the one-way ANOVA logistic model, and it shows that there is a significant random variation in the log-odds of protesting across the countries. This implies that the probability of engaging in protests for all respondents in the past year is 0.11 and that this effect varies significantly depending on the respondent’s country. The intra-class correlation of the model is 0.13, which suggests that about 13% of the total variance in protest behaviour occurs due to overall country differences. Model 3 introduces control variables to the random-effects (RE) model, demonstrating that women were 24% (i.e., log odds of −0.28) less likely to engage in protests than men. The random effects for the slopes for gender and the intercept on protest behaviour vary significantly across African countries, with consideration of control variables.

2.2. Cross-over effects models for gender, political context, and protest behaviour

Table reveals the impact of gender on protest behaviour within the context of open and closed political systems while controlling for other socio-demographic variables. The contextual variables show the situations in which the gender gap in protest behaviour narrows and widens. These results are also reflected in the first and second difference AME results in Table . Table shows significant cross-level effects between gender, years of being under military administration, years of democratic administration, and the level of freedom in the country (p < 0.05).Footnote2 This level of significant association was not present with the proportion of female legislators, the proportion of female ministers, and the inclusion of a gender quota for elective seats in the constitution.

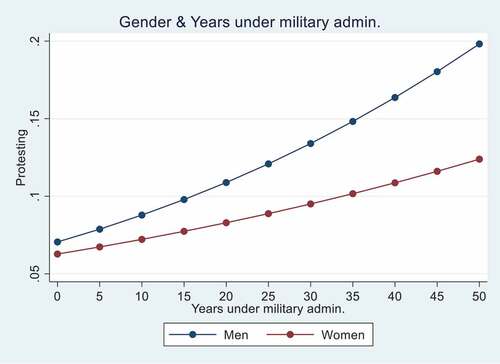

Results from the cross-level effects in Table show that more though higher years of military administrations increase the tendency of protest behaviour, the gender gap in protest behaviour widens in countries that have been under military regimes longer. This wider gap is also evident in the positive coefficient years living under a military regime (0.011, p < 0.05) and the negative coefficient for the interaction between gender and years under a military regime (−0.011, p < 0.05). This result implies a widening of the gap between the slopes for females and males, as shown in Figure . Table reveals that women engage less in protest than their male counterparts and that these effects increase with more years of military administration in the country. This result is evident from the increasing negative values that range from 0 to 6 years to 0 to 50 years. For instance, when one compares countries that have never experienced a military administration to countries that have experienced 12 years of military regimes, the gender gap in protests differs by a predicted probability of 1.4%. As shown in Figure , men were more likely to be engaged in protests in countries with more years of military administration.

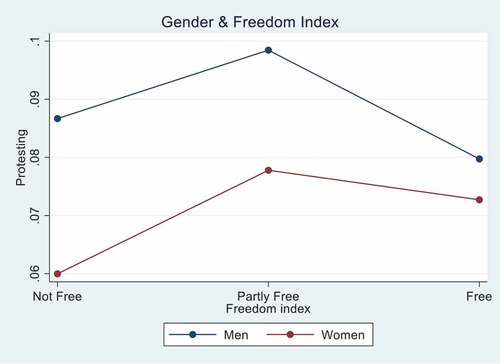

Conversely, the cross-level results show that the gender gap in protest behaviour narrows in politically free countries (i.e., in terms of civil and political rights) and with increasing years of a country being a democracy. In other words, the tendency of women to engage in protests at a lower rate than men diminish with increasing years of democratic administrations. Figure shows that the gender gap in protest behaviour is narrowest when a country is politically free. In other words, the gender gap for protest behaviour significantly narrows between non-free countries and free countries. Table reveals that when one compares countries that are not politically free to politically free countries, the gender gap in protest closes by a predicted probability of 2.6%.

Figure 3. The association between gender and protest behaviour and years under military administration(s) in the context of the freedom index categories.

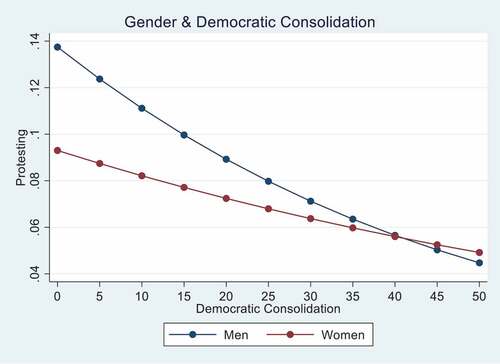

For years of a country’s democratization, protesting declines for both genders with increased years of democracy. As evident in Figure , this trend impacts males more than their females. Using the log-odds results in Model 2, it would take about 41 years of democratization in country for men’s and women’s protest behaviour to be at the same level. The AME results in Table show that the gender gap in protest behaviour begins to narrow for both genders, especially from the point a country approaches its 31st year of being a democracy. When countries that have been a democracy for a year are compared to those that have been a democracy for 31 years, the gender gap in protest closes by a predicted probability of 4%.

Figure 4. The association between gender and protest behaviour in the context of the number of years a country has been a democracy.

Table also shows that female political representation variables, such as gender quotas for political seats in the constitution and the proportion of female legislators, do not have any contextual impact on the association between gender and engagement in protests.

3. Discussion

This study examined the political context in which the gender gap in protest behaviour narrows or widens. I tested the impact of the openness of a political system and the tendency of state repression to influence the gender gaps in protesting. The study shows that the gender gap in protest behaviour widens in countries that have more years of being under military regimes but that it narrows with increasing years of democratization and politically free countries.

This study contributes to the literature in several important ways. This study demonstrates the impact of political context on individual protest behaviour, revealing nuance in the links between the political context and the gender gap in protest behaviour. First, the study found that women who live in countries with long histories of military regimes protested more than women who reside in countries without a history of military rule. This positive impact of a repressive environment on women’s protest behaviour has been noted in previous studies (Baldez, Citation2002; Brockett, Citation1991; Cuzan, Citation1991; Friedman, Citation1998; Kitschelt, Citation1986; Lu & Yang Citation2019). Closed political systems can encourage high-risk forms of political participation by emboldening individuals to seek unconventional means of becoming politically active.

Second, this study found that indicators of closed political systems, such as not being politically free and living in a country with longer histories of military rule, widens the gender gaps in protest behaviour. Conversely, politically free countries with more years of democratic administrations tend to have the narrowest gender gaps in protest behaviour. As shown in the margin plots, men’s rates of protest behaviour increased in countries that are not politically free and with longer histories of military regimes, and such behaviour declines in countries that have more years of democratic administration. Consequently, the gender gaps in protest behaviour narrow in open political systems and widen in closed political systems. The findings of this study differ from those of Desposato and Norrander’s (Citation2009) research, which concluded that the gender gaps in unconventional political participation decline in authoritarian regimes. Even though Desposato and Norrander’s (Citation2009) study was undertaken in the global South, the differences in findings may reflect possible variations in how gender norms and expectations operate in Latin American and African countries. The unique socio-cultural environment in Latin America may embolden women to be politically vocal in oppressive regimes (Baldez, Citation2002; Friedman, Citation1998), and these dynamics may work differently for women in African societies. These conflicting findings show the need for further comparative research on the variations in the socio-cultural and political environment of unconventional and high-risk political behaviours in the global South.

Third, the current study expands knowledge of the political context in gender gaps in political behaviour in African countries. Although none of the examined countries in Africa are currently under military administrations, the findings of this study point to the negative impact of the histories of military regimes on the gender gap in protest behaviour. These findings suggest that a predominance of military regimes in the political life of a nation can have a gendered effect on African women’s political behaviour. In Africa, women’s political participation is generally perceived as a deviation from traditional social norms, reducing their tendency to engage in politics in the future (Gottlieb, Citation2016). The impact of these social norms is complicated by the negative political environment military regimes leave as a country transition to a democracy. This negative political atmosphere could engender fear and increase political apathy among African women, especially in emerging democracies. However, interestingly, in this same political environment, men’s protest behaviour is significantly higher, possibly reflecting traditional masculine-oriented political values and norms, as African men may be emboldened to be more politically vocal in countries that have recently transitioned from military administrations to democracies. It is also possible that men are less invested in protesting in open systems, perhaps reflecting relatively less need to in open systems.

Although sustained democratization narrows the gender gap in protest behaviour, it is important to note that some democratic regimes have authoritarian leaders. Former military leaders have headed several “democratic” administrations in Africa, as seen in the Gambia, Uganda, and Nigeria. Providing another avenue to examine how open systems inform the gender gap in protest behaviour, the freedom index indicates that the protest gender gap was the narrowest in politically free countries. Countries that have enshrined civil and political rights can provide citizens with an environment that enables them to be politically vocal (McAdam & Tarrow, Citation2019), especially for women. Over time, open political systems become more inclusive as political institutions grow more stable and receptive to women’s political agency (Hern, Citation2018). Women’s political participation tends to improve with more electoral cycles (Lindberg, Citation2004). It is also possible that open political systems reduce the likelihood of engaging in a protest in a manner that is more positive for African women (Dalton et al., Citation2009; DiGrazia, Citation2014).

This study did not find evidence of the impact of female political representation on women’s protest behaviour. A study by Barnes and Burchard (Citation2012) on African countries came to a similar conclusion. They found that, although there was a marginally significant association between female representation in parliament and women’s engagement in protests, this relationship was not as robust as female representation and other measures of civic engagement, like contacting government or party officials and talking about politics. It is possible that a gendered political context does not impact the same forms of political engagement as the non-gendered political context examined in this study, especially for protest behaviour. This observation may be due to the sequence of the importance of these variables for the gender gap in protest behaviour, especially in emerging democracies. Variables like the absence of a military administration and being a politically free country seem to be vital factors that influence high-risk political behaviour among African women. This study highlights the need for political freedom to be established in a growing democracy before female political representation can have a significant impact on women’s protest behaviour. The political culture that emerges from a politically free society can create an inclusive environment that welcomes African into the socio-political sphere. Thus, newly developing democracies might need to develop some level of political maturity and stability before women develop enough confidence to become politically active. This study does not suggest in any way that female political representation is not important for the gender gap in protesting. However, it is possible that in newly emergent democracies, several democratic prerequisites, like the correction of the negative political environment created by previous military regimes and the protection of political and civil rights, need to be established before gender-specific contextual variables can become consequential for women’s protest behaviour.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study does not imply any causative explanations of the gender gap in protest behaviour, given the cross-sectional nature of the dataset. Future research can be undertaken with panel data, which could provide causative explanations for some of the gender gaps in protest behaviour. The contextual variables in this study do not explain all the variations in protest behaviour among the African countries. There are other dimensions of political context that could have unique consequences for the gender gaps in protest behaviour, such as party politics, elite alignment, and political instability or decentralization. However, it is difficult to ascertain or measure the stability or instability of elite alignments in these emerging democracies, given that the political systems and party platforms in most African countries tend to lack ideological foundations (Elischer, Citation2012). Similarly, it is also difficult to examine the influence of crucial allies in emerging democracies since most of these countries are relatively closed from global ideological influences. Given the emergent nature of African democracies, local groups and networks typically lack the requisite structures and resources to sustain impactful mass movements in Africa. Thus, future qualitative and quantitative studies could be undertaken to conceptualize these other dimensions of the political context in Africa and to explore how these other dimensions shape the gender gap in protest behaviour.

4. Conclusion

Even with its high risk of participation, protests play a critical role in the democratization and legitimation processes of emerging democracies, especially among African nations. Citizens tend to employ protests to communicate their political preferences to the state (Harris & Hern, Citation2019). The legitimacy of the political system is strengthened when a polity fosters an inclusive environment for marginalized groups to participate, especially women. An inclusive environment also enables women to be politically vocal and their political agency to be appreciated as the norm rather than seen as a deviation. This study contributes to the literature on protesting in Africa by examining the role of the political context. The findings of this study suggest that open or closed political systems can create two seemingly contradictory implications for protesting for both genders. On the one hand, an open system, which reduces the likelihood that men will engage in protest, reduces the gender gap in protest behaviour. Arguably, the traditional masculine political values that inform political behaviour among men, especially in oppressive societies, often become less emphasized in a politically free society. On the other hand, the negative atmosphere created by the history and legacy of military regimes can be exacerbated by the predominance of masculine political values, which ascribe the public sphere as a male-only arena. It is within this sphere that male political voices become more amplified than those of their female counterparts. Thus, these findings point to the possible interplay of gender norms and values, the political context, and political behaviour.

Overall, women’s protest behaviour represents one of the means through which they can engage with the state, given their marginalized status in many African societies. The emerging nature of African democracies tends to close different avenues of political engagement and women’s ability to protest can revive the political culture in many African communities. Further studies are needed to unpack these socio-political dynamics of gender and protest behaviour. These studies can examine how gender norms and expectations interact with the political context to influence protest behaviour. It would also be interesting to know the extent to which gendered norms, the political context, and protest behaviour assume similar roles in other third world countries and, possibly, the global North.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with regards to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this study and article.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully appreciates Afrobarometer for making the dataset of this study available for use.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eugene Emeka Dim

My names are Eugene Emeka Dim, and I am a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Toronto. My core research focuses on the dynamic linkages between political behaviour, criminality, and gender in Africa. Some of the topics I conduct research on include social movements, gender issues, intimate partner violence, and corruption in Africa. My research draws on data from the Canadian General Social Survey on Victimization, Afrobarometer survey, and the Nigerian Demographic Health Survey (NDHS).

Notes

1. These countries include Algeria, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroun, Cote d’voire, Cape Verde, Egypt, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritius, Malawi, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, South Africa, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Swaziland, Sao Tome and Principe, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

2. It is important to note that the size of the main, especially the interaction coefficients, are relatively low given that protest behaviour in Africa is rare. As shown in the descriptives, the prevalence of protest behaviour is about 9.6%.

References

- Adeniyi-Ogunyankin, G. (2014). “Spare Tires,” “Second Fiddle,” and “Prostitutes”? Interrogating Discourses about Women and Politics in Nigeria. Nokoko, 4, 11–19.

- Allam, N. (2018). Women and the Egyptian Revolution: Engagement and Activism during the 2011 Arab Uprisings. Cambridge University Press.

- Andrew, E. O. (2018). Women’s struggle for representation in African political structure. Gender and Behaviour, 16(2), 11219–11234.

- Asiedu, K. G. (2019). Africa has forgotten the women leaders of its independence struggle. Posted on Quartz Africa: https://qz.com/africa/1574284/africas-women-have-been-forgotten-from-its-independence-history/. Retrieved November 1st, 2019.

- Azikiwe, A. (2010). Women at forefront of African liberation struggles. Posted on Workers World: https://www.workers.org/2010/world/women_africa_0819/. Retrieved November 1st, 2019.

- Baldez, L. (2002). Why Women Protest: Women’s Movements in Chile. Cambridge University Press.

- Banaszak, L. A., Liu, S. S., & Tamer, N. B. (2021). Learning gender equality: How women’s protest influences youth gender attitudes. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2021.1926296

- Barakat, Z., & Fakih, A. (2021). Determinants of the Arab Spring Protests in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya: What Have We Learned? Social Sciences, 10(8), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080282

- Barnes, D. T., & Burchard, S. M. (2012). “Engendering” Politics: The Impact of Descriptive Representation on Women’s Political Engagement in Sub- Saharan Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 46(7), 767–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012463884

- Bawa, S., & Sanyare, F. (2013). Women’s Participation and Representation in Politics: Perspectives from Ghana. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(4), 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.757620

- Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: The database of political institutions. The World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/15.1.165

- Berger, I. (2014). African Women’s Movements in the Twentieth Century: A Hidden History. African Studies Review, 57(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2014.89

- Booth, J. A., & Bayer, P. (1996). Repression, Participation and Democratic Norms in Urban Central America. American Journal of Political Science, 40(4), 1205–1232. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111748

- Borland, E., & Sutton, B. (2007). Quotidian Disruption and Women’s Activism in Times of Crisis, Argentina 2002–2003. Gender & Society, 21(5), 700–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243207306383

- Bratton, M. (1999). Political Participation in a new Democracy: Institutional Considerations from Zambia. Comparative Political Studies, 32(5), 549–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032005002

- Brockett, C. (1991). The Structure of Political Opportunities and Peasant Mobilization in Central America. Comparative Politics, 23, 253–274. https://doi.org/10.2307/422086

- Brown, A. M. (2001). Democratization and the Tanzanian State: Emerging Opportunities for Achieving Women’s Empowerment. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 35(1), 67–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2001.10751217

- Caren, N., Ghoshal, R. A., & Ribas, V. (2011). A Social Movement Generation: Cohort and Period Trends in Protest Attendance and Petition Signing. American Sociological Review, 76(1), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122410395369

- Coffe, H., & Bolzendahl, C. (2011). Gender Gaps in Political Participation Across Sub-Saharan African Nations. Social Indicator Research, 102(2), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9676-6

- Corcoran-Nantes, Y. (1997). Female consciousness or feminist consciousness? Women’s Consciousness raising in community-based struggles in Brazil. In S. A. Radcliffe & S. Westwood (Eds.), Viva: Women and popular protest in Latin America (pp. 136–155). Routledge.

- Corcoran, K. E., Pettinicchio, D., & Young, J. T. N. (2011). The context of control: A cross-national investigation of the link between political institutions, efficacy, and collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 575–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02076.x

- Cuzan, A. (1991). Resource Mobilization and Political Opportunity in the Nicaraguan Revolution: The Praxis. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 50, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.1991.tb02490.x

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies (5th ed.). CQ Press.

- Dalton, R., Van Sickle, A., & Weldon, S. (2009). The Individual–Institutional Nexus of Protest Behaviour. British Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340999038X

- Desposato, S., & Norrander, B. (2009). The gender gap in Latin America: Contextual and individual influences on gender and political participation. British Journal of Political Science, 39, 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000458

- DiGrazia, J. (2014). Individual Protest Participation in the United States: Conventional and Unconventional Activism. Social Science Quarterly, 95(1), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12048

- Dim, E. E., & Asomah, J. Y. (2019). Socio-demographic Predictors of Political participation among women in Nigeria: Insights from Afrobarometer 2015 Data. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 20(2), 91–105.

- Elischer, S. (2012). Measuring and comparing party ideology in Non-industrialized societies: Taking party manifesto research to Africa. Democratization, 19(4), 642–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2011.605997

- Evans, A. (2016). ‘For the Elections, We Want Women!’: Closing the Gender Gap in Zambian Politics. Development and Change, 47(2), 388–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12224

- Fakih, A., & Sleiman, Y. (2022). The Gender Gap in Political Participation: Evidence from the MENA Region. Review of Political Economy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2022.2030586

- Friedman, E. J. (1998). Paradoxes of Gendered Political Opportunity in the Venezuelan Transition to Democracy. Latin American Research Review, 33(3), 87–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0023879100038437

- Gifford, P., & Louis, W. R. (1988). The Transfer of Power in Africa: Decolonization 1940-1960. Yale University Press.

- Gordon, S., Struwig, J., Roberts, B., Mchunu, N., Mtyingizane, S., & Radebe, T. (2019). What Drives Citizen Participation in Political Gatherings in Modern South Africa? A Quantitative Analysis of Self‑Reported Behaviour. Social Indicator Research, 141(2), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1851-1

- Gottlieb, J. (2016). Why Might Information Exacerbate the Gender Gap in Civic Participation? Evidence from Mali. World Development, 85, 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.05.010

- Hargreaves, J. D. (1996). Decolonization in Africa (The Postwar World). Routledge.

- Harris, A., & Hern, E. (2019). Taking to the Streets: Protest as an Expression of Political Preference in Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 52)8(8), 1169–1199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018806540

- Hassim, S. (2003). The Gender Pact and Democratic Consolidation: Institutionalizing Gender Equality in the South African State. Feminist Studies, 29(3), 504–528.

- Hatch, J. (1967). Africa - the rebirth of self-rule (The Changing world). Oxford University Press.

- Hern, E. (2018). Gender and participation in Africa’s electoral regimes: An analysis of variation in the gender gap. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 8(2), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1458323

- Hsiung, P. (2001). The Outsider Within and the Insider Without: A Case Study of Chinese Women’s Political Participation. Asian Perspective, 25(4), 213–237. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2001.0008

- Hughes, M. M., & Tripp, A. M. (2015). Civil War and Trajectories of Change in Women’s Political Representation in Africa, 1985–2010. Social Forces, 93(4), 1513–1540. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov003

- International IDEA. (2019). Gender Quotas Database. Posted on IDEA: https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/gender-quotas/database. Retrieved December 12th , 2019.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). (2019). Sexism, harassment, and violence against women parliamentarians, 2016. Available at IPU: https://www.ipu.org/news/press-releases/2016-10/ipu-study-reveals-widespread-sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-mps. Retrieved June 24th, 2019.

- IPU. (2019). Women in National Parliaments. Posted on IPU: http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/world-arc.htm. Retrieved December 12th , 2019.

- Isaksson, A., Kotsadam, A., & Nerman, M. (2014). The Gender Gap in African Political Participation: Testing Theories of Individual and Contextual Determinants. The Journal of Development Studies, 50(2), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.833321

- Iwara, I. O., Amaechi, K. E., Itsweni, P., & Tshifhumulo, R. (2018). Political Process Explanations of the Rise of Women Representation in Leadership Positions in National Politics: The Case of South Africa. Affrika: Journal of Politics, Economics, and Society, 8(2), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.31920/2075-6534/2018/V8n2a2

- Iyer, L., & Mani, A. (2019). The road not taken: Gender gaps along paths to political power. World Development, 119, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.004

- Kitschelt, H. (1986). Political Opportunity Structures and Political Protests: Anti-nuclear Movements in Four Democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 16(1), 57–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712340000380X

- Lindberg, S. I. (2004). Women’s Empowerment and Democratization: The Effects of Electoral Systems, Participation, and Experience in Africa. Studies in Comparative International Development, 39(1), 28–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686314

- Liu, S. (2022). Gender gaps in political participation in Asia. International Political Science Review, 43(2), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120935517

- Liu, S. S., & Banaszak, L. A. (2017). Do Government Positions Held by Women Matter? A Cross-National Examination of Female Ministers’ Impacts on Women’s Political Participation. Politics & Gender, 13(01), 132–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X16000490

- Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. Stata Press.

- Lu, Y., & Yang, F. (2019). Does State Repression Suppress the Protest Participation of Religious People? Sociology of Religion. A Quarterly Review, 80(2), 194–221.

- McAdam, D. (1986). Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer. The American Journal of Sociology, 92(1), 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/228463

- McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Introduction: Opportunities, mobilizing structures, and framing processes – toward a synthetic, comparative perspective on social movements. In D. McAdam, J. D. McCarthy, & M. N. Zald (Eds.), Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements (pp. 1–22). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- McAdam, D., & Tarrow, S. (2019, Pp 1942). 1942). The Political Context of Social Movements. In D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, H. Kriesi, & H. J. McCammon (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (Second Edition) (pp. 19–42). John Wiley & Sons.

- McCammon, H. J., Campbell, K. E., Granberg, E. M., & Mowery, C. (2001). How Movements Win: Gendered Opportunity Structures and U.S. Women’s Suffrage Movements, 1866 to 1919. American Sociological Review, 66(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657393

- McCarthy, J. (2015). 5 Latin American protest you may not have heard about. Posted on Global Citizen: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/5-latin-american-protests-you-may-not-have-heard-a/. Retrieved December 16th , 2019.

- Mize, T. (2019). Best Practices for Estimating, Interpreting, and Presenting Nonlinear Interaction Effects. Sociological Science, 6, 81–117. https://doi.org/10.15195/v6.a4

- Mlambo, C., & Kapingura, P. (2019). Factors influencing women political participation: The case of the SADC region. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1681048. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1681048

- Molyneux, M. (2002). Gender and the Silence of Social Capital: Lessons from Latin America. Development and Change, 33(2), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00246

- Mood, C. (2009). Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It. European sociological review, 26(1), 67–82.

- Mood, C. (2010). Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

- Ortiz, D. G. (2007). Confronting Oppression with Violence: Inequality, Military Infrastructure and Dissident Repression. Mobilization: An International Journal, 12(3), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.12.3.u18h874r87m32655

- Ottemoeller, D. (1999). The Politics of Gender in Uganda: Symbolism in the Service of Pragmatism. African Studies Review, 42(2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/525366

- Patterson, D. (2000). Political Commitment, Governance and Aids. Discussion paper,

- Pilati, K. (2011). Political context, organizational engagement, and protest in African countries. Mobilization: An International Journal, 16(3), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.16.3.t5578801065mx5w0

- Puddington, A. (2013). Freedom in the World 2013: Democratic Breakthroughs in the Balance: Posted on FreedomHouse: https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FIW%202013%20Booklet.pdf. Retrieved December 10th , 2019.

- Puglise, N. (2017). How these six women’s protests changed history. Posted on The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/21/womens-march-protests-history-suffragettes-iceland-poland. Retrieved November 7th , 2019.

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis. Sage Publications Inc.

- Robinson, A. L., & Gottlieb, J. (2019). How to Close the Gender Gap in Political Participation: Lessons from Matrilineal Societies in Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000650

- Schussman, A., & Soule, S. A. (2005). Process and Protest: Accounting for Individual Protest Participation. Social Forces, 84(2), 1083–1108. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0034

- Stockemer, D. (2011). Women’s Parliamentary Representation in Africa: The Impact of Democracy and Corruption on the Number of Female Deputies in National Parliaments. Political Studies, 59(3), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00897.x

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2015). Contentious Politics (Second Edition) ed.). Oxford University Prss.

- Tripp, A. M. (2006). Uganda: Agents of change for women’s advancement. In G. Bauer & H. E. Britton (Eds.), Women in African parliaments (pp. 158–189). Lynne Rienner.

- Tripp, A. M. (2019). Women and Politics in Africa. In T. Spear, (Ed.) Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. Date: November 1st, 2019 Retrieved from

- Viterna, J. (2006). Pulled, Pushed, and Persuaded: Explaining Women’s Mobilization into the Salvadoran Guerrilla Army. The American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1086/502690

- Vráblíková, K. (2014). How Context Matters? Mobilization, Political Opportunity Structures, and Nonelectoral Political Participation in Old and New Democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 47(2), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013488538

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2014). The Global Gender Gap Report. WEF:

- Yoon, M. Y. (2001). Democratization and Women’s Legislative Representation in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization, 8(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000199