?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The gendered distribution of house work is one of the most significant concerns leading to the perpetuation of gender inequality. The objective of the present study was to identify attitudes towards gender division of labor and convictions regarding the nature of spousal relationships among never married youth in Wolaita Sodo town. A cross-sectional study design with a survey research method was used to collect quantitative data from randomly selected unmarried youth. A total of 403 young people participated in the study, of which 377 (254 males & 123 females) fully completed and returned the questionnaire. Data were analyzed and presented using both descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. The result of the study shows 64.1% of them believe that both husband and wife should share household tasks. Respondents have also a relatively favorable attitude towards gender-based division of housework (M=2.5, SD=.37582) and negative attitude towards gender-based violence against women (M=2, SD=.51754). Results of coefficients of regression found that age, sex, and residential background of respondents are the independent variables significantly affecting respondents’ attitude towards gender division of domestic labor, gender equality, and gender-based violence. While there is a widely held belief that men should do housework, attitudes towards the classification between public and domestic tasks is found to be less gendered in the study area. Moreover, despite a widely held belief that public tasks and housework should not be gender segregated, the belief in the capability of women to do public tasks equally with men has been found to be low.

Public Interest Statement

The study, “Attitude Towards Gender Division of Labor and Convictions Regarding the Nature of Spousal Relationships among Never Married Youth in Ethiopia,” is of critical public interest in this era of social equity, gender parity, and minimal understanding of gender roles. The study provides a comprehensive understanding of how gender division of labor impacts individual’s convictions regarding spousal relationships. The study’s findings have significant implications for policymakers and stakeholders who seek to promote gender equality by emphasizing viewpoints that can bridge the divide in gender roles. The results of this study offer insights that could lead to interventions that aim to shift attitudes towards gender division, promote gender diversity, and ensure a more equitable society in Ethiopia. Therefore, this research is of critical importance and should be widely disseminated to increase awareness, enhance understanding, and educate society on issues related to gender equality.

Background

Gender is a socially constructed codification of differences between males and females that define the nature of social relationships between them (Jelaludin et al., Citation2001). The American Psychological Association (Citation2015) attributes gender to “a person’s deeply felt, inherent sense of being a boy, a man, or a male; a girl, a woman, or a female; or an alternative gender that may or may not correspond to a person’s sex assigned at birth or to a person’s primary or secondary sex characteristics.” Furthermore, gender differences between men and women are mainly characterized by the different types of roles assigned to both sexes by society, including the perceptions held among members of society regarding appropriate gendered roles. In fact, these roles are culturally defined by a particular social group and hence, are not determined by biological factors (Shale et al., Citation2009; Singh, Citation2016). Moreover, gender roles and relationships, in addition to acting as markers of social identities, have an influence on the division of work, the use of resources, and the distribution of production benefits between men and women (Lemlem et al., Citation2010).

Acquiring gender-specific behavior is an important part of our identity, how others react to us, and how we respond to them (Singh, Citation2016). Unlike sex roles, which are biologically determined characterizations of males and females designed to ensure successful reproduction of offspring based on the sexual division of labor (The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Citation2005), gender roles are expectations that tell individuals what sort of behavior is appropriate for which sex and are the result of interactions between individuals and their environments (Blackstone, Citation2003). It refers to people’s opinions on what roles men and women should play in their society (Van, Citation2014). Men and women are affected differently by gender roles and responsibilities in terms of the risks they take, the types of risks they face, their efforts to improve their health, and how the health system responds to their needs (Matud, Citation2017; WHO, Citation2014). Furthermore, rigid gender norms also influence men’s and women’s access to power, prestige, and other socially valued resources, including social services.

The gendered division of domestic labor is one of the major factors contributing to the persistence of gender inequality. Notwithstanding their admission into paid jobs, women continue to do more domestic work than males, limiting their ability to act on an equal ground in the workplace (Lyonette & Crompton, Citation2015). According Bartley et al. (Citation2005) division of household labor along gendered lines, appeared to continue, for couples that worked at least 30+ hours of week in paid employment and wives spent more time in household labor and were much more likely to be involved in low-control household tasks (those traditionally perceived as women’s work). Cohen (Citation2004) argues that there is a clear link between the work that women do at home and the occupations that are dominated by women in the labor market. Gender role attitudes spans from egalitarian—a predisposition to believe that men and women should play the same roles—to traditional—a tendency to feel that men and women should play separate roles (Fischer & Arnold, Citation1994).

There appears to be a relationship between domestic labor and the wage disparity between men and women. Women perform more housework than men, yet the number of chores men and women have varies. Women perform more housework when they work fewer hours, but men’s housework does not vary in relation to their work hours. Even when contrasted to the small percentage of males who also do a lot of housework, there is a pay gap for women who do the most housework (Brynin, Citation2017). According to the devaluation hypothesis, a notion that society assigns men and women differing capabilities, women are considered to excel at household and family obligations, whereas men are said to be more productive at gainful jobs. As a result, women and the professions in which they are mostly engaged have lower social prestige and are underpaid (Anne & Elke, Citation2013). In addition, pay disparities between men’s and women’s occupations might occur as a result of variances in human resource requirements. The compensating differentials theory, for example, suggests that, in female-dominated industries, lower pay compensates for greater possibilities to combine work and home duties (Katharina, Citation2019).

In Ethiopia, traditionally, men are expected to be courageous, competent, domineering, and to show qualities of leadership, while women are supposed to be submissive, conservative, self-speaking, and shy (Gelana, Citation2013). Different traits are typically emphasized for girls and boys; girls are encouraged to play with dolls as this prepares them for their future role as the nurturer and care giver of the household, whereas boys are oriented toward more aggressive and also more action-packed games and toys as this prepares them for future masculine behavior (Singh, Citation2016). According to Campa and Serafinelli (Citation2019), gender differences in work-related attitudes and gender-role attitudes are major predictors of labor market gender inequality. In most societies, men and women had important roles in the economic structure before the industrial revolution segregated women from the world of men and placed them in a subordinate position (Larsen & Long, Citation1988). The gender-based division of labor that resulted from the socially ascribed gender roles has made women primarily responsible for tedious, repetitive, tiresome, time-consuming, and economically unrewarding activities that have in turn constrained their interaction with the external environment. Conversely, men benefited from this gender division of labor that has made them responsible for only some seasonal activities, allowing them to predominate in the public spheres, to perform activities that are economically rewarding and to maintain their dominance in gender relations (Honey Hassen, Citation2007). According to Colton (Citation2008), women’s involvement in the workforce has grown, while their roles in the home have remained relatively unchanged.

Gendered cultural norms, values, attitudes, and practices shape how girls and boys are raised and learn to view themselves as adults in rural Ethiopia. According to Kinati and Mulema (Citation2018), gender relations in Ethiopia are highly unequal and women’s lack of independent status and their exclusion from leadership are embedded in the socio-culture of the society. Men are seen as household leaders, public personalities, predominant earners, and final authority in the family and community. Women’s low status and powerlessness in all spheres of life are exacerbated by patriarchal, hierarchical, and polygynous household structures, women’s young age at marriage, patrilocal residence after marriage, large age gaps between spouses, unequal work burdens between sexes, high bride price, and women’s low educational level (Paulina, Citation2001). Women continue to work longer hours on domestic tasks than men, and the sex segregation of housework means that husbands and wives typically define their domestic chores along sex-typical lines (Blair & Lichter, Citation1991).

Changes in gender roles have accompanied changes in family structure in Western countries, most notably an extension of the women’s position to that of an economic provider for a family and, more recently, a modification of men’s role with more comprehensive engagement in family duties (Oláh et al., Citation2018). Despite the fact that the gender gap in labor market participation has shrunk, gender differences in everyday experiences in the workplace and pay levels persist. Most men and a considerable majority of women in developing countries embrace the conventional division of labor, feel salary differences are acceptable, and believe that family and childcare are mostly the responsibility of women (Karu & Roosaar, Citation2006). In developing nations, women’s labor force participation varies substantially more than men’s. Economic and social variables such as economic growth, education, and social norms all play a role in this variance (Verick, Citation2014). According to Ali and Hussnain (Citation2005), for instance, a working woman in Pakistani culture is not only disapproved of, but also highly discouraged. The widely held belief is that it feels undignified for a father to live on the wages of his daughters or a husband on his wife’s salary.

Housework, according to the gender display approach, also known as “doing gender,” is a way for husbands and wives to show off their gender identities to others. This method looks at how people utilize self-presentation, such as housework, to build gendered identities (Civettini, Citation2015). Feminists claim that a society’s long-held and socially constructed gendered norms and values lead to the gendered distribution of domestic labor between men and women (Fraser, Citation2000). According to Becker (Citation1991), traditional sex role attitudes and beliefs are crucial and continue to encourage traditional notions of “woman’s work”. Owing to such established assumptions, actors may be consistently categorized as men or women in all circumstances and perceived as more or less fit candidates for various tasks and places in society (Ridgeway, Citation2001).

Economic theories suggest that the spouse who brings more resources to the partnership will be able to persuade the other spouse to undertake more housework (Becker, Citation1991). From the other side, the “relative resource” or “economic dependence” argument asserts that fulfilling domestic responsibilities is a function of the time available to both couples (Lyonette & Crompton, Citation2015). Women will have more time to handle household chores since men work longer hours in the market. This suggests that as women become “more like men” and work in paid employment, men will become “more like women” and undertake more housework. According to Civettini (Citation2015), the smaller the income gap among couples, the fairer the distribution of housework is. This means that women’s earnings are proportional to their share of housework and network hours, and that women’s share of housework reduces as their economic reliance on their husbands/partners diminishes.

Despite the popular support for the notion that dual-earner couples should share homework equally, the fact is that only a small proportion of couples split family obligations for themselves in an equivalent manner (Blair & Lichter, Citation1991). Even when both couples work outside the home, women do considerably more housework than men. According to data from the University of Wisconsin’s National Survey of Families and Households, housekeeping takes 38 hours a week for women who do not work outside the home, compared to 12 hours for their husbands. Working women outside the house continue to handle the majority of the cooking and cleaning, putting in roughly 28 hours per week, while working women’s husbands put in about 16 hours per week (O’grad, Citation2015). While many females stated a desire for a more equitable distribution of labor at home in a survey done in Ethiopia by Jones et al. (Citation2014), it was evident that guys and parents did not see such aspirations in an “ideal wife.” The authors pointed out that attitudes toward rigid gender norms change with time, and that education, religious leaders, role models, and the backing of male relatives all played important roles in this case.

Although the long-held notion of domestic duties in Ethiopia as exclusively “women’s tasks” is predicted to shift over time as women’s participation in formal employment rises (Colton, Citation2008; WHO, Citation2001), this assumption has to be confirmed empirically. Moreover, young people especially men’s attitudes towards gender-based violence against women and gender equality at large has remained a neglected area of study in Ethiopia. The present research, therefore, is aimed at identifying attitudes towards gender division of labor and convictions regarding the nature of spousal relationships among never married youth in Wolaita Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Design of the Study

Both descriptive and explanatory study designs were used in the research. The researchers used a quantitative research approach and a cross-sectional study design. Because quantitative findings are far more likely to be extrapolated to an entire community or a sub-population since they involve a bigger, randomly selected sample, the researchers adopted a quantitative research approach (Carr, Citation1994). Aside from sampling, quantitative data analysis saves time because it makes use of statistical tools like SPSS (Connolly, Citation2007).

Sources of data and collection methods

First-hand information was acquired from research subjects through the survey research method. This method was chosen due to its advantages of allowing research participants to analyze relationships between variables as well as its generalizability. The survey research design was also chosen for its adaptability in terms of the types and quantity of variables that may be researched, as well as its ease of development and administration. A self-administered questionnaire was developed, transcribed into Amharic (to ensure that the items were understood), duplicated, and distributed to survey participants. A pilot study, prior to the main data collecting process, was done on a similar population that was distinct from the real samples to assess any challenges related to data collection and the compatibility of the data collection instrument.

Sampling method

A multi-stage stratified sampling method that involved splitting the population into several categories was used to determine the sample size of survey participants. In doing so, three kebeles (the smallest governmental administrative units in Ethiopia) were chosen using a simple random sampling mechanism from a total of seven administrative kebeles located in Wolaita Sodo town. Because the information related to the population size of each kebele was outdated and no new data was available, the total population number in the study areas was unknown. As a result, the researchers used Cochran’s (Citation1977) sample size determination technique on an unknown population to estimate the appropriate sample size:

Where n is the sample size, z is the desired confidence level’s selected critical value, p is the population’s estimated proportion of an attribute, q = 1 p, and e is the desired precision level. In addition to the ones that corresponded to the projected sample size, 5% extra questionnaires were duplicated to support the expected non-response rate. As a result, 403 questionnaires (384 + 19) were given at random to unmarried young adults in each kebele. Age, marital status, residency, ability to read and write the questionnaire’s language, and full agreement to participate in the study were all prerequisites for survey participation. As a result, all young people between the ages of 15 and 35 who had never married at the time of data collection, could read and write, had given their full consent to participate in the study, and were inhabitants of Wolaita Sodo town were included.

Instrument design

The questionnaire was developed in part from Blair and Lichter’s (Citation1991) and Zewude et al. (Citation2021) and then contextualized to the study’s specific objectives. The questionnaire was handed to two language specialists from Wolaita Sodo University before the pilot test. While one expert assessed and commented on the English version, the other looked at the version that had been translated into the local language. Age, sex, educational background, religion, and grownup area were among the socio-demographic data included in the initial section of the questionnaire. Moreover, respondents were asked to fill in a blank space with their correct age, which is calculated by the total number of years a person has lived since birth. Sex was also defined as a biological variation denoted by the terms “female” and “male.” Additionally, educational backgrounds were classified as “never attended school,” “1–8,” “9–12,” “college diploma,” “BA or BSc,” and “MA or MSc & above”. The religion categories were “Orthodox Christian,” “Muslim,” “Protestant,” “Catholic,” “Jehovah,” “Adventist,” “Atheist,” and “Other”. Furthermore, the respondent’s grownup area was determined by whether he or she was raised in a “rural” or “urban” setting.

The gender role orientations of respondents were divided into two categories: sex role attitudes and family role attitudes. The respondents’ attitudes toward sex-based task segregation and how each spouse should act in marriage were assessed using a four-point Likert scale. Respondents’ opinions toward sex roles were assessed as follows: “Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with each of the following statements”: 1) “It is better if the man earns the main living and the woman takes care of the home and the family”; 2) “Preschool children are likely to suffer if their mother is employed,” and the response categories for these questions were (4=strongly agree, 3=agree, 2=disagree, 1=strongly disagree). Respondents were classified as having traditional, mixed, or egalitarian attitudes toward sex roles based on the results of the Likert scale. Beliefs and convictions regarding the nature of spousal relationships were measured by questions such as: “Whom do you believe should work domestic tasks (cooking, cleaning house, etc.)?” and “Whom do you believe should earn the main living?” with response categories of 1) husband, 2) wife, 3) both. In addition, attitudes towards gender-based violence against women were assessed using questions such as: “It is normal or acceptable if a husband rarely beats his wife,” “A wife facing any abuse from her husband should accuse him in a court of justice,” and “A wife should tolerate the verbal abuse of her husband”.

On the other hand, respondents’ views regarding family roles (attitudes toward domestic division of work) were examined by asking them the following questions: 1) “couples that share domestic tasks would have successful marriage”, 2) “if both couples work outside, they should also equally share housework”, 3) “women disrespect men that do housework”, 4) “even if unemployed, a husband should never do housework” 5) “It is taboo for men to do domestic tasks” with response categories of 4 = strongly agree, 3 = agree, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree.

Data analysis

The completeness of the questionnaires that were returned by the respondents was reviewed first. The ones that were correctly completed were then entered into SPSS Version 20 software. The internal consistency of the Likert scale items were evaluated using a factor of (8.6), and content and face validity assessments were used to ensure the instrument’s validity. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were also used to present the software’s output. The gender role orientation of respondents was assessed by the mean of attitudes measured on a likert scale derived from twenty statements prepared for this purpose. A 4 point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree) was used to examine the attitude of respondents towards gender division of labor. In this case, respondents’ attitudes, put on a continuum, ranges from (1.0) holding a strongly negative attitude to (4.0) strongly positive attitude. For the sake of convenience, we took 2.0 point as a reference (threshold) value, where the mean of attitude below this threshold is labeled as negative and above it as positive. In addition, a line graph was also utilized to depict the distribution and trends of the mean of attitudes in relation to the threshold. Participants are said to have traditional gender role attitudes when they agreed or score a relatively higher mean that a traditional division of labor in which men are assigned to play the role of breadwinner while women play the role of homemaker is recommended. On the other hand, when respondents do not agree or score a relatively lower mean (usually below 2.0) with this type of division of labor and want a more equitable or at least flexible division of labor, they are said to have an egalitarian or modernized division of work (Van, Citation2014). Moreover, regression coefficients were also used to analyze aspects linked to respondents’ gender role attitudes. Independent variables with significance levels less than 0.05 were deemed meaningfully related with the dependent variables using a 95 % confidence interval.

Results

Table presents data pertaining to the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. Accordingly, most (67.4%) of the respondents are males while females constitute 32.6%. Moreover, 250 of the 377 research participants (66.3%) reported their educational status to be 9–12 grade, followed by BA/Sc Degree holders (18.3%), and college diploma (6.6%). Furthermore, majority (70.6%) of respondents disclosed to have grown up in urban area while the remaining (29.4%) have grown up in rural areas. Above all, 59.4% of respondents’ mothers are employed during the period of data collection for the present study. Data have also shown that the mean for the age of respondents is 20.7 (SD = 4.9). Data regarding the religious affiliation of respondents reveals that majority (59.9%) of them are followers of Protestant religion, followed by Orthodox Christianity (23.6%), and Islam (4.8%).

Table 1. Socio demographic characteristics of respondents

Convictions regarding the nature of spousal relationships among never married youth

The data presented in Table reveals that most respondents have an egalitarian type of both sex-role and family role attitudes. Of 377 respondents, 242 (64.1%) believed that both husband and wife should share household tasks. Moreover, 324 (85.9%) of respondents believe that the duty of earning a living should be shared between both men and women. When both couples share the breadwinner role, the homemaker position is much more likely to be shared as well. (25). The sex distribution of gender-role orientations of respondents reveals that males resemble more towards the traditional gender role classifications than their female counterparts. For instance, more male (99) than female (34) respondents believe that the duty of doing housework should be reserved for wives. In addition, 35 males, compared to 16 females, believe that the responsibility of earning the main living should belong to the husband. Furthermore, most respondents (207 or 54.9%) believe that both men and women can propose for marriage or romantic relationships.

Table 2. Beliefs about gender-based division of labor between husband and wife

Data presented in Table also confirms that respondents have egalitarian gender-role attitudes. It is found that the majority (79.3%) of respondents believe that married couples should have an egalitarian division of both the household and the public tasks, followed by 10.9% of respondents with the traditional gender-role attitude in which the husband works outside while the wife takes care of the domestic chores.

Table 3. Acceptable patterns of marital life styles perceived by respondents

Data presented in Table shows the frequency distribution of respondents in terms of their perceptions regarding how appropriate or acceptable are different behaviors for a husband and a wife. It is found that respondents attribute the same behavior differently to men and women. For instance, many respondents (36.9%) perceive that aggressiveness is more appropriate for a husband compared to 15.6% who believe that the same behavior is acceptable for a wife. Moreover, being courageous has been believed to be appropriate for a husband (70.3%) compared to the 48.3% of respondents who believe that a wife should be courageous. Furthermore, while the majority (79.3%) of respondents replied that husbands should be hard workers, mercifulness has been the most frequently mentioned (61.3%) behavior of wives. Above all, 46.4% of respondents believe that both men (husbands) and women (wives) should have humor as a common behavior.

Table 4. Respondents’ convictions about how appropriate are various behaviors for husbands and wives

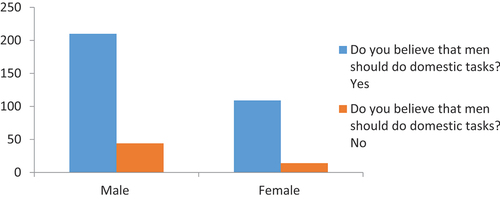

The data presented in Figure show that 319 of the 377 respondents believe that men should do housework. In addition, of the 319 respondents who replied that men should do housework, 254 (67.3%) of them are males. On the other hand, female respondents constitute a smaller (28.9%) proportion of respondents who believe that men should do housework.

Table presents the frequency distribution of respondents in terms of their reasons for believing that men should not do housework. Accordingly, most (36.7%) of the respondents argued that it is against their traditional norm, followed by 35% who believe that housework is a woman’s duty. Furthermore, while 18.3% of respondents believe that doing housework reduces men’s dignity, 10% of them hold that love diminishes between couples when men are allowed to do housework. It is also found that baking enjera is the type of housework that most of the respondents (64.9%) believe men should never do unless there is a compelling reason. It is followed by making doro wot (61.4%), making coffee (58.7%), and baking bread (55.5%). On the other hand, feeding children (38.3%), playing with children (39.4%), and buying consumables (42.4%) are types of domestic tasks over which respondents show less concern about being done by men.

Table 5. Reasons for believing that men should not do housework and distribution of household tasks that respondents believe men should never do

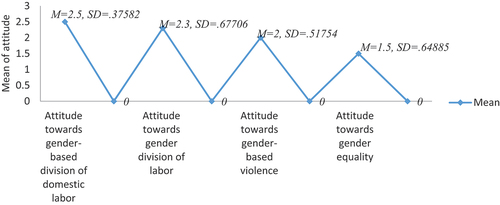

Data presented both in Figure and Table reveal that respondents have a positive attitude towards gender-based division of household labor (M = 2.5, SD=.37582) and a negative attitude towards the equality of men and women (M = 1.5, SD=.64885). By most measures of attitude towards gender division of housework, unmarried youth in the study area have been demonstrated to hold an egalitarian type of family role orientation. Furthermore, respondents have also shown a positive attitude towards gender-division of the public tasks. It implies that most respondents have maintained a lenient and mid-way position as far as the traditional gendered segregation of public and domestic activities between men and women is concerned. For instance, most respondents have negatively reacted to the statements that “Preschool children are likely to suffer if their mother is employed” (M = 2.8, SD=.89432) and “It is better if the man earns the main living and the woman takes care of the home and the family” (M = 2.23, SD=.98190). Nevertheless, respondents were found to be less sensitive about gender-based violence. According to the data, it is understood that most respondents held the belief that women should tolerate the verbal and physical abuses of men. Figure shows the aggregated mean distribution of attitudes towards the four dimensions of gender: gender-based division of domestic labor, gender division of labor in general, gender-based violence, and gender equality. It shows changing patterns in attitude as we move across the line where respondents hold (expressed in a relatively higher mean score) a positive attitude pertaining to gender-based division of domestic labor (M = 2.5, SD=.37582) and their attitude gets negative when it comes to the belief in gender equality (M = 1.5, SD=.64885).

Table 6. Descriptive statistics regarding respondents’ attitude towards gender division labor, gender-based violence, and gender equality

Factors associated to attitude towards gender division of labor, gender-based violence, and gender equality

Table presents coefficients of linear regression regarding the association between attitudes towards gender division of domestic labor, gender equality, and gender-based violence. It is found that age, sex, and residential background of respondents are the independent variables significantly affecting respondents’ attitudes in all the three dimensions of gender discussed above. The sex of respondents has been found to significantly affect both attitudes towards gender-based violence (−.170, P < 0.001) and attitudes towards gender equality (−.278, P < 0.01). Findings of cross tabulations revealed that males have a relatively more favorable attitude towards both gender-based violence and gender equality than their female counter parts. In addition, attitudes towards gender-based division of domestic labor have been found to be significantly associated with the age (0.015, P < 0.01) of respondents. Accordingly, respondents’ attitude towards gender-based division of housework gets increasingly egalitarian with increasing age. Moreover, attitudes towards gender-based violence are also found to be significantly associated with the residential background of respondents (−.178, P < 0.01). In other words, resistance to gender-based violence increases with a rural residential background.

Table 7. Coefficients of linear regression

Discussion

Acquiring gender-specific behaviors is an essential component of who we are, how others respond to us and how we respond to them. It is through one’s own culture that gender relations within a society and the activities of men and women are determined. Different traits are usually promoted for girls and boys; girls are encouraged to play with dolls as this prepares them for their future position as caregivers and guardians of the family, while boys are guided towards more aggressive and action-packed games and toys (Singh, Citation2016). Gender disparities in work attitudes and gender role attitudes are important predictors of gender inequality in the labor market (Campa & Serafinelli, Citation2015). The aim of the study was to identify attitudes towards gender division of labor and convictions regarding the nature of marital relationships among never married youth in Wolaita Sodo town. The results showed that most of the respondents have an egalitarian type of both sex-role and family-role attitudes. Of 377 respondents, 242 (64.1%) of them believe that both husband and wife should share household tasks. The sex distribution of gender-role orientations of respondents reveals that males resemble more the traditional gender role classifications than their female counterparts. For instance, more male (99) than female (34) respondents believe that the duty of doing housework should be reserved for wives. Chesters (Citation2012) found that gender attitudes towards housework have changed over time in Australia. According to the author, women spent a lower proportion of their domestic work time on basic household chores in 2005 than they did in 1986, implying that household activities have grown less gendered over time.

Women’s increased involvement in the employment sector, their enhanced engagement in scientific studies, improvements in women’s education, mass media, and women`s movements are the most effective factors to change traditional gender role attitudes (Kirca, Citation2012; Larsen & Long, Citation1988). Pimkina and De La Flor (Citation2020) also noted that economic growth, technological advancement, increased availability of childcare options, economic shocks that affect households where men are traditionally wage earners, rising education and declining fertility among women as the main drivers for women’s labour force participation in developing countries. According to O’neil and Domingo (Citation2015), urbanization, economic diversification, and changes in the gendered division of labor are slowly shifting social beliefs and expectations in developing countries. Women are now more visible in public life than they have ever been throughout modern history. However, in their classic work “The second shift: working parents and the revolution at home,” Hochschild and Machung (Citation1989) refers women’s engagement in both paid employment and homework as a “stalled revolution,” one that got wives out of the house and into the first shift of paid employment but produced surprisingly little change during the domestic second shift. According to the study, women are often the primary parent and are ultimately responsible for housekeeping. In most marriages, the woman’s paid labor is still regarded as a mere job, in contrast to the man’s career. As a result, the woman’s first shift—her employment—is likely to be undervalued, explaining her continued responsibility for the second shift. Recent studies such as, Cerrato and Cifre (Citation2018) also asserted the continued influence of conventional gender norms on how men and women handle work and family interaction. On the other hand, Gershuny et al. (Citation2005) argued that the longer wives have been working outside the home, the more likely husbands are to take on household duties.

Findings of the present study also revealed that respondents have positive attitude towards gender-based division of household labor (M = 2.5, SD=.37582) and negative attitude towards the equality of men and women (M = 1.5, SD=.64885). This conclusion is congruent with the findings of Shteiwi (Citation2015), who discovered a significant shift in attitudes regarding gender equality, domestic division of work, and women’s economic and political engagement as a result of Jordan’s recent modernization initiatives. According to Jones et al. (Citation2014), supportive attitudes originate from a combination of sympathy and fear of the law; males realized that girls’ homework had a detrimental influence on their academic achievement. Nevertheless, respondents have found to be less sensitive about gender-based violence. According to the data, it is understood that most respondents held the belief that women should tolerate the verbal and physical abuses of men. According to Flood and Pease (Citation2006), attitudes play a role in how people respond to violence against women, other than the perpetrator or victim. Men who have negative opinions about women and who take into account traditional masculinity and masculine preferences are more likely to engage in violence against women. Gender-based violence results from women’s powerlessness and relationships with men, and the main risk factors include: being abused as a child, exposure to violence as a kid, male control of home decision-making and money, cultural norms that favor violence as a way of resolving issues or male domination over women, low educational levels of men and women, and policies and regulations that discriminate against women (Marrison et al., Citation2004). Despite widespread support for the idea that dual-earner couples should handle household chores equally, the reality is that only a few couples have real gender similarities in the way family responsibilities are shared.

Results of coefficients of regression found that age, sex, and residential background of respondents are the independent variables significantly affecting respondents’ attitude towards gender division of domestic labor, gender equality, and gender-based violence against women. Paulina (Citation2001) also found sex as an independent variable significantly affecting attitudes towards sex roles and that woman tends to prefer the egalitarian gender role attitude while negative attitude towards divorce, authoritarian predispositions, and conservative attitude towards sexuality are significantly associated to traditional sex role attitude. Moreover, Chesters (Citation2012) found sex, educational status, and belongingness to co-breadwinner families as factors determining attitude towards housework and argued that the more balanced a man’s attitude towards gender roles, the more time he spends cooking, cleaning, and doing laundry. In addition, men from co-breadwinner families spent a greater proportion of their total domestic work time on essential tasks than did men from new traditional male breadwinner families, even after the effects of gender attitudes were kept constant. Furthermore, males with greater levels of education committed a bigger proportion of their overall housework hours to core housekeeping chores, whereas women with higher levels of education devoted a lesser proportion of their time. According to Shteiwi (Citation2015), educational status, residential background, and attitudes towards democratic values determine attitude towards gender equality in which respondents with better educational status, having an urban residential background, and possessing supportive views of democracy were found to hold a more positive attitude towards gender equality.

Conclusion

Unmarried youth in Southern Ethiopia have an egalitarian sex-role and family-role orientation. While there is a widely held belief that men should do housework, the distinction between public and domestic tasks is found to be less gendered in the study area. The present study has also found remarkable changes in the traditional gender-role attitude in which men earn the main living and women do the domestic tasks, such as cooking and laundering. While many young people believe that men should do housework, the main reasons for those who do not believe in men’s engagement in domestic tasks have been that it is against their traditional norm and believing it is solely a woman’s responsibility. Furthermore, baking enjera and making doro wot, household tasks that are commonly perceived as women’s, are those that most unmarried men believe men should never do. The overall pattern in the findings of the present study reveals young people’s decreasing attitude from gendered division of housework to gender-based violence and the belief in gender equality. Generally, while respondents hold positive sex-role and family-role attitudes, they maintain negative attitudes towards both gender equality and gender-based violence against women. In other words, though there is a widely held belief among the unmarried youth that public tasks and housework should not be gender segregated, the belief in the capability of women to do public tasks equally with men has been found to be low. Above all, being male, older, and having a rural residential background significantly determine attitudes towards gender-based division of housework, gender equality, and gender-based violence against women.

Limitations of the study and suggestions

The current study on attitude towards gender division of labor and convictions regarding the nature of spousal relationships in southern Ethiopia is a valuable contribution to the existing literature on this topic. However, it has some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, the study relied solely on quantitative data, which may have overlooked important nuances that could have only been understood through qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews or focus group discussions. Furthermore, the study may not capture hidden aspects of division of labour, such as emotional labour, which is often relegated to women.

To address these limitations, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods can be used in future studies to gain a better understanding of the various facets of the gender division of labour. Moreover, triangulation, the use of multiple sources of data, can help resolve potential limitations arising from using a single source. Finally, using more sophisticated statistical methods can help improve the accuracy of the results of future studies.

Ethical approval

The study was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Approval Committee of the University where the corresponding author serves during the study period (DU-HSC/1529/14). In addition, a formal letter was obtained from the same University, College of Social Sciences and Humanities.

Informed consent

Research participants were first informed about the purpose of the research, including what role was expected from their side. Both verbal and written consent were gained from all research participants. All interviews were conducted individually in a private location, enabling respondents to feel that they were being contacted in safe environment. Above all, during the process of data collection, research participants were communicated that they can skip any questions that they would prefer not to answer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to the study participants for their time and willingness to share their perspectives. We would also like to express our profound gratitude to the editorial team and reviewers for their time spent assisting us in improving our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Getahun Siraw

Getahun Siraw is a senior lecturer of sociology at Dilla University. He is dedicated to teaching and mentoring students while also conducting cutting-edge sociological researches. His research interests are in important societal issues, with public health, gender, marginalization and IDPs attracting his attention and has published several research findings.

Bewunetu Zewude

Bewunetu Zewude is an assistant professor of sociology at Wolaita Sodo University. He has rich experiences in undertaking researches, providing trainings and participating in national and international research conferences. He has been conducting social science and public health related researches and published dozens of articles on peer reviewed journals.

Tewodros Habtegiorgis

Tewodros Habtegiorgis is an assistant professor of sociology at Wolaita Sodo University. With vast experience in teaching and conducting research, Tewodros has authored multiple publications in top journals and contributed for the advancement of sociological knowledge. His work revolves around public health, social inequality and gender.

References

- Ali, H., & Hussnain, S. (2005). Males attitude towards females education and employment. Journal of Agricultural and Social Science, 1(3), 288–17.

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. The American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039906

- Anne, B., & Elke, H. (2013). Geschlechtsspezifische Verdienstunterschiede bei Führungskräften und sonstigen Angestellten in Deutschland: Welche Relevanz hat der Frauenanteil im Beruf? Zeitschrift Für Soziologie, 42(4), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2013-0404

- Bartley, S. J., Blanton, P. W., & Gilliard, J. L. (2005). Husbands and wives in dual-earner marriages: decision-making, gender role attitudes, division of household labor, and equity. Marriage & Family Review, 37(4), 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v37n04_05

- Becker, G. (1991). A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press.

- Blackstone, A. (2003). Gender Roles and Society in Human Ecology: An Encyclopedia of Children, Families, Communities, and Environments, Eds. J. R. Miller, R. M. Lerner, & L. B. Schiamberg. ABC-CLIO. PP 335–338 ISBN I ISBN I576078523.576078523.

- Blair, S., & Lichter, D. (1991). Measuring the division of household labor: Gender segregation of housework among American couples. Journal of Family Issues, 12(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251391012001007

- Brynin, M. (2017). The gender pay gap: Research report 109. equality and human rights commission, Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex.

- Campa, P., & Serafinelli, M. (2015). Politico-economic Regimes and Attitudes: Female Workers under State-socialism. Working Papers. https://ideas.repec.org/p/tor/tecipa/tecipa-553.html

- Campa, P., & Serafinelli, M. (2019). How are gender-role attitudes and attitudes toward work formed? Lesson from the rise and fall of the iron curtain. Free Network.

- Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research: What method for nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20(4), 716–721. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20040716.x

- Cerrato, J., & Cifre, E. (2018). Gender Inequality in household chores and work-family Conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01330

- Chesters, J. (2012). Gender attitudes and housework: Trends over time in Australia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 43(4), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.43.4.511

- Civettini, N. (2015). Gender display, time availability, and relative resources: Applicability to housework contributions of members of same-sex couples. International Social Science Review, 91(1), 1–34.

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling Techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen, P. (2004). The gender division of labor “keeping house” and occupational segregation in the United States. GENDER & SOCIETY, 18(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243203262037

- Colton, T. (2008). Women’s perceptions of quality of household work: Department of edu. Psy and Spe.Edu College of Edu.Uni. Saskatchewan.

- Connolly, P. (2007). Quantitative data analysis in education: A critical introduction using SPSS. Routledge.

- Fischer, E., & Arnold, S. (1994). Sex, gender identity, gender role attitudes, and consumer behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 11(2), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220110206

- Flood, M., & Pease, B. (2006). The Factors Influencing Community Attitudes in Relation to Violence Against Women: A Critical Review of the Literature, 3. VicHealth. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/103401/

- Fraser, N. (2000). Rethinking recognition. New Left Review. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii3/articles/nancy-fraser-rethinking-recognition

- Gelana, G. (2013). Impact of gender roles on women involvement in functional adult literacy in Ethiopia: A review. International Journal of Social Sciences, 9(1), 37–54.

- Gershuny, J., Bittman, M., & Brice, J. (2005). Exit, voice, and suffering: Do couples adapt to changing employment patterns? Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 656–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00160.x

- Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Viking.

- Honey Hassen, T. A. U. (2007). Gender Manual, prepared to facilitate gender mainstreaming for projects financed by CSF. European Commission Civil Society Fund in Ethiopia.

- Jelaludin, A., Angeli, A., Alemtsehay, B., & Salvini, S. (2001). Gender issues, population and development in Ethiopia, In-depth studies from the 1994 population and housing census in Ethiopia, Central Statistical Authority (CSA) Addis Ababa. Ethiopia & Institute for Population Research – National Research Council (Irp-Cnr) Roma.

- Jones, N., Bekele, T., Stephenson, J., Gupta, T., & Pereznieto, P. (2014). Early marriage in Ethiopia: The role of gendered social norms in shaping adolescent girls’ futures. Overseas Development Institute.

- Karu, M., & Roosaar, L. (2006). Attitudes towards gender equality in the work place. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

- Katharina, W. (2019). Gender pay gap varies greatly by occupation, DIW Economic Bulletin, ISSN 2192-7219, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW). Berlin, 7(43), 429–435.

- Kinati, W., & Mulema, A. A. (2018). Gender issues in livestock production in Ethiopia. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/107953

- Kirca, B. (2012). Gender-Role Attitude. International University of Sarajevo, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

- Larsen, K., & Long, E. (1988). Attitudes toward sex-roles: Traditional or egalitarian? Sex Roles, 19(1/2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292459

- Lemlem, A., Sambrook, B., Puskur, R., & Ephrem, T. (2010). Opportunities for promoting gender equality in rural Ethiopia through the commercialization of agriculture, Improving Productivity and Market Success of Ethiopian Farmers Project (IPMS)–. International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa.

- Lyonette, C., & Crompton, R. (2015). Sharing the load? Partners’ relative earnings and the division of domestic labor. Work, Employment and Society, 29(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017014523661

- Marrison, A., Ellsberg, M., & Bott, S. (2004). . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS3438. The World Bank.

- Matud, M. P. (2017). Gender and Health. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313263152_Gender_and_Health

- The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. (2005). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, Retrieved from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/sex-roles-gender-roles.

- O’grad, S. (2015). Division of labor in relationships: How to make it work. O'GRADY PSYCHOLOGY ASSOCIATES. https://ogradywellbeing.com/division-labor-relationships-what/

- Oláh, L. S., Kotowska, I. E., & Richter, R. (2018). The new roles of men and women and implications for families and societies. In G. Doblhammer & J. Gumà (Eds.), A demographic perspective on gender, family and health in Europe. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72356-3_4

- O’neil, T., & Domingo, P. (2015). The Power to decide: Women, decision making and gender equality. Overseas Development Institute.

- Paulina, M. (2001). SOCIOCULTURAL FACTORS AFFECTING FERTILITY IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA. Workshop on prospects of fertility decline in high fertility countires, June 9-11, New York. UN/POP/PFD/2001/2. Department of Economic and Social affairs, United Nation Secretariat. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undp_egm_200107_paper_sociocultural_factors_affecting_fertility_makinwa-adebusoye.pdf

- Pimkina, S., & De La Flor, L. (2020). Promoting Female Labor Force Participation. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/fb460cc2-191f-5953-8cc5-57ab26481e75/content

- Ridgeway, C. L. (2001). Small-group Interaction and Gender. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 14185–14189. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03999-1

- Shale, G., Boo, E., & Subramani, J. (2009). Gender roles in crop production and management practices: A case study of three rural communities in Ambo District, Ethiopian. Journal of Human Ecology, 27(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2009.11906186

- Shteiwi, M. (2015). Attitudes towards gender roles in Jordan. British Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 12(2), 15–27.

- Singh, V. (2016). The influence of patriarchy on gender roles. International Journal of English Language, Literature and Translation Studies, 3(1), 27–29.

- Van, M. (2014). Gender Role Attitudes. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1135

- Verick, S. (2014). Female labor force participation in developing Countries: Improving employment outcomes for women takes more than raising labor market participation- good jobs are important too. International Labor Organization. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.87

- WHO. (2001) . Occupational Health: A manual for primary health care workers. World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

- WHO. (2014). Gender and health in the Western Pacific Region. World Health Organization, Western Pacific Region. https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/10819/Gender_health_fact_sheet_2014_eng.pdf

- Zewude, B., Habtegiorgis, T., & Melese, B. (2021). The attitude of married men towards gender division of labor and their experiences in sharing household tasks with their marital spouses in Southern Ethiopia. East African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 6(2), 101–114.