Abstract

The lack of a framework for agritourism development is contributing to underutilization of agricultural attractions for tourism purposes especially in developing countries. This study therefore sought to develop a framework for sustainable agritourism in Zimbabwe. The development of the framework was guided by the critical success factor (CSF) framework, the stakeholder theory and the triple bottom line approach. To develop the framework, a multiple case study design was adopted. Two case studies, Manicaland and Mashonaland West, were chosen. In-depth interviews were conducted with 59 stakeholders who were purposively selected from the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water, Fisheries and Rural Resettlement, Zimbabwe Tourism Authority, tour operators and from farmers. The interviews were conducted from October 2021 to June 2022. Thematic content analysis and NVivo 12 were used for data analysis. The study proposed a framework that illuminates three critical stages for sustainable agritourism development in Zimbabwe which are planning, development and implementation. The main guiding principles that were identified were environmental scanning for enablers, multi-stakeholder engagement, identification of potential farms that meet the requirements for agritourism and identification of CSFs at farm level. The relationships amongst these guiding principles were established. Providing guidelines for the development of this tourism concept can encourage farmers, policymakers and all other relevant stakeholders to develop necessary planning, development and implementation strategies that may result in successful and sustainable agritourism development.

1. Introduction

Agritourism is a holiday concept that involves visiting a farm operation for purposes of recreation, leisure, education or involvement in the activities of the operation (Chatterjee & Prasad, Citation2019b; Prasanshakumari, Citation2016; Yamagishi et al., Citation2021). Chase et al. (Citation2018) identified five categories of agritourism which are hospitality, entertainment, outdoor recreation, education and direct sales. On the other hand, Phillip et al. (Citation2010) developed a typology for defining agritourism in which they emphasised the issue of a working farm and an increased contact of tourist with farm experiences as important in authentic agritourism. For agricultural operators, agritourism represents a means of diversifying operations and is a potential source of additional revenue (Lucha et al., Citation2016). In contemporary tourism, there are growing interests among tourists for farm-based activities (Barbieri, Citation2019) such as buying produce direct from a farm stand, picking fruit and vegetables, feeding animals, or staying at a farm (Prasanshakumari, Citation2016).

A growing segment of the tourist market consists of people who are tired of the same old sun, sea and sand vacations, seeking instead meaningful journeys designed to foster people-to-people connections with local people who work and live in the destinations (Comen, Citation2017; Stokovic & Grzinic, 2016; Chikuta & Makacha, Citation2016). This change in consumer behavior with regard to food, culture and nature (Brandano et al., Citation2018) has prompted entrepreneurs to develop meaningful engagement with farms and the farming community (Arroyo et al., Citation2019). The concept of agritourism has gained prominence in the developed world as evidenced by the extensive research being done in the regions. Previous agritourism research (Chaiphan, Citation2016; Comen, Citation2017; Cristina et al., Citation2017));Chase and Ramaswamy (Citation2007); Ciolac et al. (Citation2019) indicate that most important investigations around this area have been done in the developed world. There is a literature gap in agritourism development in developing countries with only few research in Southern Africa done by Rogerson and Rogerson (Citation2014) and Chikuta and Makacha (Citation2016).

When looking at factors that influence the propensity to develop entrepreneurship activities in agritourism, several researches (Broccardo et al., Citation2017; Chase et al., Citation2018; Chatterjee & Prasad, Citation2019a) focus more on a microeconomic perspective, by emphasizing characteristics of the farmer and characteristics of the farm/surrounding land, for example. There are fewer studies that consider the macroeconomic approach in order to investigate the political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental (PESTLE) factors that lead to successful agritourism development in a region. Few researches (Cristina et al., Citation2017; Forbord et al., Citation2012; Genovese et al., Citation2017), which have adopted the macroeconomic approach, have looked at the economic and social factors that influence the success of agritourism businesses without specifically referring to all of the factors to the concept of agritourism entrepreneurship. Moreover, these studies were done in a European context and might not be applicable in the African context given the differences in these regions’ macroeconomic environments.

The tourism industry in Zimbabwe has not fully embraced agritourism despite being agro-based and having a number of farms that can be developed and promoted as agritourism destinations. Prior 2000, most land in Zimbabwe was in the hands of the minority white farmers (Chitsike, Citation2003; Guvamombe, Citation2019). Across the country, the formal land re-allocation since 2000 has resulted in the transfer of land from the white farmers to nearly 170,000 black farmers by 2011 (Scoones et al., Citation2011). The Land Reform Programme, allocated to new farmers over 4,500 farms making up 7.6 m hectares, 20% of the total land area of the country by 2001. In 2008–09 this represented over 145,000 farm households in A1 schemes and around 16,500 farm households occupying A2 plots (Chitsike, Citation2003; Scoones et al., Citation2011). Despite all these developments agritourism has not gained popularity among Zimbabwean farmers. This has been attributed to many factors. There has been no deliberate effort to promote Zimbabwean farmers to venture into agritourism (Guvamombe, Citation2019), despite confirmation by researchers (Chikuta & Makacha, Citation2016; Chiromo, Citation2016; Tanyanyiwa, Citation2017) that agritourism is a possible alternative tourism product for Zimbabwe. The few farmers who have tried to get into it have been incapacitated by lack of capacity-building programmes (Chikuta & Makacha, Citation2016; Guvamombe, Citation2019). The absence of framework to guide successful agritourism development in the country has been identified by Chikuta and Makacha (Citation2016) as the major drawback to agritourism development in Zimbabwe. In view of this, the researchers aimed at developing a framework for sustainable agritourism that provides guidelines for the development of agritourism in the country. This was achieved through conducting a literature study to identify main themes in agritourism development and an analysis of stakeholder perceptions regarding the development of the concept in the country. The next session discusses the theoretical underpinnings upon which this study was built followed by a discussion of the methods used. The findings section provides the framework for sustainable agritourism in Zimbabwe and an explanation of the various components that make the framework. Contributions and the limitations of the paper are highlighted. The paper ends with conclusion and recommendations.

2. Theoretical framework

The development of the framework for sustainable agritourism in Zimbabwe was guided by the critical success factor (CSF) framework (Rockart, Citation1979), the stakeholder theory (1984) and the triple bottom line approach to sustainability (Elkington, Citation1994). Xavier et al. (Citation2019) confirms the relationship between the stakeholder participation and the sustainable development. On the other hand, Sterling et al. (Citation2017) noted that stakeholder engagement contributes to conservation of biodiversity. This assertion brings out the relationship between stakeholder theory and sustainability framework. There has not been any attempt by researchers to link CSF framework, stakeholder theory and the sustainability framework. This research attempted to bring out the linkage between the three as highlighted in the framework shown in Figure .

3. Critical success factor (CSF) framework

The concept of CSFs was first invented by Daniel (1961) and later modified by Rockart (Citation1979). Rockart and Bruno (Citation1981) further modified the concept through their various research in the area. The concept was first coined for use in Management Information Systems but because of its popularity and effectiveness the concept is now being applied in many fields (Amberg et al., Citation2005) including tourism. Marais et al. (Citation2016) defined, critical success factors (CSFs) as the limited number of areas in which results, if they are satisfactory, will ensure successful competitive performance of the organization.

Therefore, managers must invest in these, define them and ensure that they are maintained and sustained well (Bruno & Leidecker, Citation1984). CSFs can therefore be identified as a business characteristic, planning tool or as a market description. The terms CSFs and Key Success Factors are often used interchangeably in literature (Amberg et al., Citation2005). Rockart (Citation1979) discovered five sources of CSFs in his early studies and has been acknowledged in a later study made by Rockart and Bullen (1981). These are environmental factors, the industry, competitive advantage, managerial factors and temporal factors (Amberg et al., Citation2005; Marias et al., Citation2017; Fuentes-Medina et al., Citation2018)

4. The stakeholder theory

The stakeholder theory was first coined by Freeman (1984). In his theory, Freemen emphasises the need to involve everyone that affects and is affected by the operations of an organisation by engaging them in any matters concerned with the wellbeing of the organisation (Nguyen, Citation2016). These are groups or individuals that determine the extent to which a business achieves its objectives (Agüera, Citation2013). An organisation where there is strong interconnection among all people that affect and are affected by its operation is in a better position to deal with many challenges that may arise (Freeman, Citation2010). According to Freeman (1984), the term stakeholder refers to key players that can affect or be affected by a company’s activities. The stakeholder theory stresses the interconnected relationships between a business, its customers, employees, investors, communities and others who have a stake in the organisation. The theory asserts that stakeholders possibly and necessarily have the direct impacts on making any decision relating to management (Jones 1995).

In agritourism research, stakeholder engagement has not been well emphasised. Few studies that have been done focused on the farmer and the surrounding communities only. Little attention has been given to investigating on the perceptions of other stakeholders, such as the government and the supporting institutions in agritourism development. This research attempted to fill this gap by conducting an intensive analysis on the perceptions of all these stakeholders involved in agritourism development as each of them represents a piece of a puzzle. For agritourism development to take place, all the pieces must fit well into the puzzle (Saftic et al., Citation2011). If one piece is missing, then the puzzle cannot be solved. Consequently, if a group of stakeholders is left out in the planning and development of agritourism the results might be unfavourable.

5. The triple bottom line (TBL)

Sustainability is often referred to as triple bottom line (TBL) because it adopts a triple bottom-line approach as it integrates economic, environmental and social factors (Harrington, 2013). The framework was coined by John Elkington in Elkington (Citation1994) after the realisation that the extent of business sustainability was difficult to measure. Moreover, Elkington argued that the success of a business must not be based on a measure of profit or loss only but also on the wellbeing of people and the health of the planet (Alhaddi, Citation2016). Thus, Elkington coined the TBL framework to enable effective measurement of sustainability by complimenting the traditional three pillars with the new bottom lines for social and environmental dimensions (Purvis, Citation2018; Slaper, Citation2011). The TBL framework has become an important tool for supporting sustainability through the integration of the 3Ps (profit, people and planet) dimensions (Alhaddi, Citation2016). Companies should adopt this framework in their decision-making processes so as to ensure that decisions made have a focus on making profits which contribute to overall wellbeing of the economy, the people and the planet (Azevedo & Barros, Citation2017).

The economic aspect of TBL framework focuses on to the impact that the operations of an organization have on the economic system of a country within which it is operating (Elkington, Citation1994). It relates to the ability of the economy as a subsystem of sustainability to evolve and survive into the future and support the future generations. The social dimension of TBL represents the degree to which an organisation conducts business in a manner that is beneficial and fair to the employees and to the community at large (Elkington, Citation1994). The idea is that the organisation’s practices should provide benefits to the society and “give back” to the community. Examples of such organisational practices include fair wages, education, skills assessment, quality of life, access to social resources, equity, social capital and healthcare package provisions (Azevedo & Barros, Citation2017; Slaper, Citation2011; Woodcraft, Citation2015). The environmental measure of TBL encourages organisations to engage in practices that lead to conservation of the environmental resources for use by future generations (Elkington, Citation1994). It relates to the cost-effective use of energy resources, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, air and water quality, solid waste management and minimization of the ecological footprint. Incorporating sustainability considerations into any development in general and agritourism in particular will allow the enhancement of local communities’ livelihoods while also strengthening biodiversity conservation and the reduction of land degradation as well as building and developing economies without straining resources (Addinsall, 2016, FPAM, 2014).

6. Other frameworks that were identified in the literature

A literature analysis was conducted and other frameworks that were developed in other regions were identified and a brief description of each is given in table . The main aim of the literature search was to identify the gaps that needed attention as far as development of frameworks is concerned.

Table 1. Other frameworks that were identified in the literature

This study identified several limitations of these frameworks and attempted to address them. For example, the conceptual framework for agri-food tourism (Liu et al., Citation2017) was developed through the analysis of one family run small farm located in Dawu mountains in Taiwan which may make generalizability of results difficult. On the other hand, Chase et al. (Citation2018)’s conceptual framework for industry analysis provides an understanding of what constitutes agritourism only and does not provide the guidelines to developing sustainable agritourism. Brune et al. (Citation2018)’s framework’s main limitation is that it is demand focused which may also affect the generalizability of results. Brandano et al. (Citation2018) focused on both demand and supply sides; however, their framework does not provide guidelines for developing sustainable agritourism.

7. Methodology

CSF framework, stakeholder theory and TBL approach to sustainable development form the building blocks for this research. This conceptual framework was developed through merging themes from the literature and empirical evidence that was obtained from the fieldwork. Empirical evidence was collected through in-depth interviews with 59 stakeholders that were purposively selected from Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water, Fisheries and Rural Development (10), Ministry of Climate, Environment, Tourism and Hospitality Industry (5), tour operators (10) and from farmers (34). The researcher selected respondents who are most relevant to agritourism development from the two ministries. Moreover, the researcher selected farms with potential for agritourism development.

The respondents were asked about their perceptions on CSFs, benefits and challenges of agritourism development. A multiple case study approach was used. Manicaland and Mashonaland West provinces were selected as the study areas because they consist of vast areas of fertile land which increase their potential for agritourism development. The interviews were conducted between October 2020 and June 2021. The development of interview questions was guided by literature from Chase et al. (Citation2018); Chase et al. (Citation2019); Eshun and Mensah (Citation2020); Sawe et al. (Citation2018) and van Zyl (Citation2019). The names of the respondents were coded in order to hide their real identity. Table shows the stakeholder groups, codes that were used, composition and demographic characteristics of all the respondents that were interviewed.

Table 2. Codes, composition and demographic characteristics of respondents

Thematic content analysis aided by NVivo 12 was used to analyse the data. Through the use of NVivo 12, word frequency queries were run and the frequently mentioned themes were identified and these were used as building blocks for the framework. Thematic analysis is a method for qualitative data analysis that involves searching a data set for the purpose of identifying, analyzing and reporting repeated patterns (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This data analysis method was chosen because it is not only a technique for describing data but can also be used for interpretation during the process of code selection and theme development (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). A unique feature of the technique is its flexibility to be applied to a wide range of epistemological and theoretical framework, designs, study questions and sample sizes (Kiger & Varpio, Citation2020). Moreover, this technique was adopted for this research because it is a powerful and appropriate technique to use for analysing a data set when the aim is to understand a set of thoughts, experiences or actions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012).

This study applied thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) mainly because it has turn out to be the most extensively adopted technique of thematic analysis in qualitative literature (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) thematic analysis consists of six steps. Table illustrates how the six steps of thematic analysis were applied to this research.

Table 3. Application of thematic analysis

Various ethical issues were taken into considerations before conducting the interviews. The researchers got approval to conduct the interviews from Chinhoyi University of Technology, Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water, Fisheries and Rural Development and the Ministry of Climate, Environment, Tourism and Hospitality Industry. Informed consent was sought through a consent form from all the respondents. The limitation of the methodology was the selection of a sample from two provinces out of the ten provinces in the country. Further, the study focuses on the supply side only leaving the demand perceptions unexplored.

8. Findings

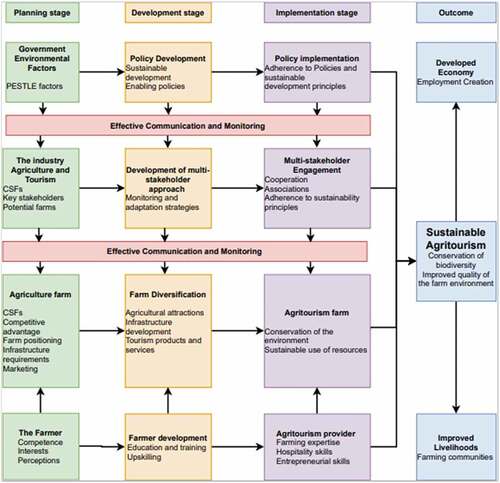

An analysis of stakeholder perceptions revealed that environmental scanning for enablers, multi-stakeholder engagement, identification of potential farms that meet the requirements for agritourism and identification of CSFs at farm level are the main guiding principles for sustainable agritourism development in the country. The relationships amongst these guiding principles were established, and these are depicted on the framework by arrows.

A framework for sustainable agritourism development

*

9. Planning stage

9.1. Step 1 scanning the macroeconomic environment

The stakeholders acknowledge the important role that the macroeconomic environment plays in successful agritourism development. An agritourism farm does not operate in a vacuum but in an environment with political, economic (inflation rates, interest rates and energy prices), social, technological, environmental and legal factors, which may hinder or promote its development. KMT4 explained that,

before independence there were quite a number of agritourism farms, now the number is catching up because of the disturbances in the political and economic environment that were caused by the land reform but there is great potential every corner of Zimbabwe has these unique offerings, each region has some icons.

The importance of the socio-cultural environment was emphasised by KMT6 who was of the view that the social and cultural mindset that “farm holidays are for white people only” must be removed if agritourism is to thrive in the country. KMA7 pointed out that agritourism is not thriving in our country because of “our culture, we don’t value entertainment”. On the other hand, KMT2 commented on technology issues that, “the farmers do not have access to knowledge or new technology available for agritourism”. All the 10 key informants from the Ministry responsible for agriculture commented on environmental factors being fundamental in sustainable agritourism development. KMA2 cited “harmony with nature” as being critical. “Keeping the natural environment good (not destroying trees and dams)”. Respondents also commented on legal issues relevant to agritourism. Zoning and licensing issues were raised during the interviews, an indication that legal requirements are critical. KMT3 highlighted his concern about the acquisition of licences. He pointed out acquiring such should be easy and affordable to those who want to venture into agritourism. He complained that, “at the moment there are so many licences required for you to start operating an agritourism venture. This put off farmers”. MF13 explained that he cannot put up tourism facilities at the farm because “the 99 year lease leaves one with no confidence to commit to such a huge investment”. KMT1 agrees that zoning and licensing issues must be addressed by government through setting aside farms and providing leases to those who want to develop agritourism.

In view of the respondents’ perceptions, the researchers, therefore, propose that policymakers at government level should take the lead in creating an enabling environment for agritourism development. The starting point involves scanning for environmental factors that are critical for agritourism development. At this stage, it is important for the policymakers to assess how these factors are affecting agritourism development and come up with policy measures that encourage and promote agritourism development. Effective communication with the relevant industries is important.

9.2. Step 2 the industry (agriculture and tourism)

The two ministries should cooperate in order to identifying CSFs at industry level, which Rockart & Bullen referred to as perceived factors. These may not only affect agritourism development but also other sectors in the industry such as the hotel and catering sectors. There is need for the two ministries to cooperate and form a central leading structure (Khartishvili et al., Citation2019) for agritourism which will work on strategic issues concerning its development. KMA8 noted that currently there is no cooperation between the two ministries, he explained that; “there is conflict between the need to increase agricultural production and the need to channel resources to tourism”. (See Table ).

Identification of other key stakeholders in agritourism development appeared as very important both in the literature and during the interviews. KMA4 ascertained that Agritex and ZTA can assist through identifying stakeholders relevant to agritourism and link them with farmers. Some of the stakeholders that are relevant to agritourism development that were identified during the interviews and how they can assist are shown in .

The two ministries should cooperate in identifying other stakeholders that may affect or be affected as postulated by the stakeholder theory (Sterling et al., Citation2017). This is important because sustainable development requires the adoption of a participatory approach whereby all the parties affecting or are affected by the development are involved in the planning and decision-making process (Khazaei et al., Citation2015). Engaging local stakeholders is a central feature of many biodiversity conservation and natural resource management projects including tourism (Sterling et al., Citation2017). Stakeholder identification encourages identification of conflicting interests (Lester et al., Citation2017) and promotes working together in order to reach a common ground (Barbieri & Streifeneder, Citation2019). Moreover, Karampela et al. (Citation2019) and Dias et al. (Citation2019), acknowledged that perceptions from all the stakeholders are vital for the promotion and development of all kinds of products and increasing cooperation promotes innovations in agritourism development (Roman et al., Citation2020).

An analysis of the responses that were given by the participants reveals that the two ministries have an important role of identifying the farmers with the potential for agritourism development. KMA7 highlighted that it is only after they have identified the farms with potential that they can start mobilising farmers to start projects like fish farming, beekeeping which will attract tourists. In this regard, KMT1 indicated that they are in the process of identifying farms with potential for agritourism. He indicated that, “under Manicaland Tourism development zone we have identified certain plantations and estates as potential areas for tourism development”.

Identification of potential requires a concerted effort of all stakeholders, and it enables maximum exploitation of all the available opportunities (Bwana et al., Citation2015). Willingness of the farmer to participate in agritourism should complement the potential for successful agritourism development. The results obtained in this study revealed that some farms have great potential for agritourism development, but the farm owner is not willing to diversify into tourism. Bhatta et al. (Citation2019) propose that the first step towards successful agritourism development is understanding the level of willingness of the farmer to diversify into agritourism. According to Bhatta et al. (Citation2019), the level of willingness forms the basis on which policymakers and other concerned stakeholders explore the next step. This framework, however, considered the exploration of willingness to participate in agritourism as a second step after scanning the environment for negative factors that might affect the farmers’ level of willingness.

9.3. Step 3 Competitive advantages and positioning of agricultural farm

This involves exploring competitive advantage of farm over other farms in terms of suitability for agritourism. Such competitive advantage should be capitalized on when planning on what farm attractions to develop at the farm to enhance visitors’ experiences. For example, MF1 explained that, I wish to resuscitate the game park that was there during the time when the farm was occupied by the whites. MF2, MFW2 and MF3 have mountain features in their farms. Availability of natural features (mountain, rivers or forests) and any other resources already available give the farm a competitive advantage (Kazmina et al., Citation2020). Other factors that may give farms competitive advantage that need to be explored are farm positioning in terms of location and climate as well as the availability of farmers' own financial resources (Dias et al., Citation2019). Most farmers are not able to identify their sources of competitive advantage and require the assistance of government and other industry players (Comen, Citation2017). Industry players also assist in identifying new ways to improve competitive advantage of potential agritourism farms given the competitive environment in which they operate in (Palmi & Lezzi, Citation2020). Exploring infrastructural and marketing requirements of farm is also crucial as these also contribute to the competitive advantage of the farms (Khairabadi et al., Citation2020).

9.4. Step 4 Managerial competencies of farmer

Exploring farmer’s competencies, interests and perceptions towards agritourism development is an important step in the planning stage that has been identified in the framework. Exploring the farmers’ competencies involves identifying the skills that the farmer already has and comparing these to skills requirements for agritourism development, identify the skill gaps and develop appropriate training programs. This assertion is in agreement with Dias et al. (Citation2019) who noted that the competencies required for diversified farming differ from those required for conventional farming. Dias et al. (Citation2019) emphasized that training programs designed to equip farmers with competencies necessary for agritourism development should be introduced not only to farmers but also to agricultural students in universities and agricultural colleges.

Tugade (Citation2020) affirmed that farmers need to acquire new skills and competencies for them to sustainably develop and manage agritourism. He added that agritourism development requires a more innovative mindset. Comen (Citation2017) identified some of the key competencies necessary that farmers should possess. These include but not limited to record keeping, budgeting, allocation of financial resources, financial planning and being able to monitor the external environment. Yamagishi et al. (Citation2021) added customer relations and marketing as other important skills necessary for agritourism development. On the other hand, Yildirim and Kilinc (Citation2018) emphasized the need for farmers to acquire foreign language proficiency so that they are able to communicate effectively with foreign visitors.

10. Development stage

10.1. Step 1 Policy formulation

Proper recognition of agritourism by the government is the first step towards the formulation of a supportive policy structure as highlighted by KMA6, KMT4 and KMT1 that policy issues are at the apex. The government should provide a full fledge policy framework that creates an enabling environment for sustainable agritourism development in the country (Priyanka & Kumah, Citation2016). Intergovernmental cooperation and coordination should be mandated in the policies. This is important for the development and promotion of agritourism (Yamagishi et al., Citation2021). Zasada et al. (Citation2017) emphasized the link between policies, agricultural landscapes and socio-economic benefits. Thus, policies should align with sustainable development as outlined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Ammirato et al., Citation2020). Sustainable development policies take account of economic wellbeing of the country and ensure that local environmental sustainability, physical-geographical and climate characteristics are entrenched in national strategies (Attila & Petres, Citation2017).

10.2. Step 2 Development of multi-stakeholder approach

Ministry responsible for Agriculture, Ministry responsible for tourism and other stakeholders identified during the planning stage should develop a platform for consultations. Monitoring of policies, development of adaptation strategies, identification of common goals and building of shared vision is imperative during the multistakeholder consultations. Moreover, effective communication amongst the stakeholders and monitoring to ensure adherence to sustainability principles is of paramount importance. It is during these consultations that the stakeholders can agree on adopting and developing agritourism as a farm diversification strategy. Development of a multi-stakeholder approach is imperative in all tourism development if sustainability is to be maintained. In most developing countries, there is minimal evidence of multi-sectoral collaboration among government sectors (Biddulph et al., Citation2018).

10.3. Step 3 Farm diversification strategy

There is a need for key stakeholders to agree, during consultations, on adopting agritourism as a diversification strategy. A consensus can only be reached if all the stakeholders are equipped with adequate information on the benefits of agritourism. Researchers, being part of the stakeholders, have the mandate to provide such information. Once consensus is reached on a strategy to pursue, it is important to develop the necessary infrastructure to support the diversification strategy. Development of tourism services such as farm restaurant and accommodation is part of the strategy and parties involved should come up with ways to develop these.

10.4. Step 4 Farmer development

Development of training programs for farmers in order to equip them with entrepreneurial and hospitality skills is critical as highlighted by 77.5% (n = 26) of the farmers who were interviewed. MF3 highlighted that, “I don’t really know how I can generate income from agritourism”. MWF10 explained that, “We don’t have enough information on the profitability of the concept”. The researcher also observed that the farmers lacked hospitality and presentation skills. The signage at the farms, for example, at MWF1, MWF10, MWF4 and MF3 were poorly done. The reception of visitors was not hospitable as observed at MWF12, MWF5 and at MF5. Yamagishi et al. (Citation2021) acknowledge that development of the farmer in terms of the soft skills (entrepreneurial, hospitality and marketing skills) will augment agritourism performance.

11. Implementation stage

11.1. Step 1 Policy implementation

This step involves the creation of an enabling environment through the implementation of policies as highlighted by KMT1, KMT4 and KMA5. Adherence to sustainability principles, effective communication of policies and monitoring the implementation process are key during this phase. Countries that uphold internationally the sustainable development principles and are more concerned about implementation of the 2030 Agenda, which is the most important global development agreement, need to realize that there is a need for concrete action that goes beyond general debates and support actions (Attila & Petres, Citation2017). This assertion by Attila and Petres (Citation2017) speaks to walking the talk and this requires a multi-sectoral approach that encourages the involvement of academic and other civil society expertise, Khairabadi et al. (Citation2020) affirms that challenges during the implementation stage are inevitable. Some of the challenges include stakeholder oppositions and conflicts (Lester et al., Citation2017). However, these challenges can be countered through providing the implementers training programs which can be facilitated by government agencies and other agriculture and tourism development experts.

11.2. Step 2 Multi-stakeholder engagement

Implementation of the multi-stakeholder approach leads to engagements in the form of cooperation, collaborations and associations meant to facilitate the development of sustainable agritourism in the country and the implementation of the policies (Mcgehee & Mcgehee, Citation2009). Government must assume the role of ensuring the consistency of governmental action and must have consistent access to information so that they effectively monitor the implementation of policies aimed at achieving sustainable development goals. Dissemination of information on policies and implementation processes should be done in a transparent and intersectoral way according to the information provided by the implementers (Attila & Petres, Citation2017). The local level has the most important role to play by providing information about the possible positive effects of sustainable development to the local people. Bwana et al. (Citation2015) confirm that sustainability requires the involvement of all key stakeholders throughout the development process. They affirmed that, during these engagements there are critical sustainability principles such as involvement of local communities and gender balance issues that should be adhered to. Regular communication with all stakeholders and monitoring is imperative. Kazmina et al. (Citation2020) affirm that cooperation and coordination of all tiers of authority form the basis of agritourism development.

11.3. Step 3 Agritourism farm

This step involves the implementation of the farm diversification strategy, which is the development of agritourism farms after consultations and agreements amongst the stakeholders. The development of agritourism farms should be done in accordance with the three pillars of sustainable development. Parties involved should ensure adherence of sustainability principles in terms of conservation of the environment and sustainable use of resources throughout the development process.

12. Outcomes

Sustainable agritourism is the main outcome in the framework. The definition of sustainable agritourism has been arrived at by integrating agritourism and the TBL sustainability concept. For the purpose of this paper sustainable agritourism development is defined as development of tourism products and services within a farm setting in a manner that leads to conservation of agrobiodiversity resources, equitable social development and an all-encompassing economic growth for the betterment of local livelihoods.

Implementation of enabling policies, multi-stakeholder engagement, sustainable use of farm resources and a skilled agritourism farmer result in sustainable agritourism. Other outcomes that come together with sustainable agritourism development include a developed economy as a result of employment creation at agritourism farms, creation of multistakeholder partnerships and networks, conservation of agrobiodiversity, ownership of resources and improved livelihoods of farming communities.

The outcome is in line with the TBL approach to sustainability by Elkington (Citation1994) which postulates that the success of a business must not be based on a measure of profit or loss only but also on the wellbeing of people and the health of the planet (Alhaddi, Citation2016). Employment creation through agritourism fulfils both the economic (profit) and the social (people) dimension of TBL. The economic dimension of TBL links the growth of a particular organization to the overall growth of the economy, and it relates to how well the organisation contributes to economic growth (Slaper, Citation2011). Job creation through agritourism will contribute to job growth in the economy. International tourists who visit the country for agritourism will bring in foreign currency which will contribute to national foreign currency earnings and to Gross Domestic Product.

The participants who were interviewed had a positive vision towards the benefits of agritourism and mentioned income and employment creation as major benefits. Once the local people have jobs that can give them income it means that their livelihoods will improve, thus fulfilling the social (people) dimension. The multi-stakeholder approach ensures that the voice of the local people is heard and issues of equality are addressed (Ammirato et al., Citation2020). Imparting skills to local communities on how they can develop and run agritourism ventures, development of infrastructure and health facilities for use by tourists also contribute to the social dimension of sustainability (Azevedo & Barros, Citation2017; Slaper, Citation2011; Woodcraft, Citation2015). The framework emphasises on multi-stakeholder engagements as a way of ensuring sustainability of the positive contributions of agritourism.

The environmental measure of TBL encourages organisations to engage in practices that lead to conservation of the environmental resources for use by future generations (Elkington, Citation1994). It relates to the cost-effective use of energy resources, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, air and water quality, solid waste management and minimization of the ecological footprint (Kearney, Citation2009). Agritourism has been cited in the literature as a sustainability strategy (Arroyo et al., Citation2019; Chatterjee and Prasad, Citation2019a; Lupi et al., Citation2017) and as a smart chance to sustainability (Ciolac et al., Citation2019) as it promotes conservation of the farm resources. The researcher also observed that agritourism has motivated farmers to conserve farm buildings by converting them into lodges. MacKay et al. (Citation2019) referred to this as “repurposing of farm buildings” for tourism.

13. Comparison with other frameworks

The framework presented in this study is similar to Brandano et al. (Citation2018) in that it emphasizes that preserving and maintaining the quality of the environment is imperative for the success of agritourism ventures. This is also in line with the environmental pillar of sustainability as postulated by the TBL approach by Elkington (Citation1994). Moreover, Brandano et al. (Citation2018) also emphasized on the issue of professional service staff in delivering agritourism services as a factor that influences the selection of one agritourism venture over another. The framework that was presented in this study also identified assessing skill requirements of farmers as a CSF for agritourism success. Further, Brandano et al. (Citation2018) also brought out the issue of competitive advantage in the form of farm attractiveness which is enhanced by landscape. The framework presented in this study incorporated assessment of the farm competitiveness as critical during the planning stage.

The framework that was developed in this study differs from the frameworks that were identified in the literature (Table ) in several ways. Firstly, the framework in this study was developed in a developing world context, while the identified frameworks are biased towards developed agritourism destinations. Further, the framework integrates CSF concept, sustainability and stakeholder theory in agritourism development, whereas the identified frameworks lack a theoretical foundation. Moreover, the framework puts emphasis on sustainability principles which have been overlooked in most agritourism studies. The framework integrates literature and more specific findings obtained from the fieldwork. This made the framework more relevant and applicable to the study areas. The relevance of the framework to the study areas is an indication that it can also be useful to other provinces in the country and to other developing countries. The limitation of the framework was that its valuation was limited to its applicability in the study areas in Zimbabwe. Critiquing the value of the framework beyond the study area is recommended for future research.

14. Conclusion

The framework that was developed in this study is a first attempt to provide guidelines for agritourism development with a developing world perspective. It is the first of its kind in Zimbabwe. This study will contribute to the strengthening of multi-stakeholder engagements and formation of associations responsible for steering the development of sustainable agritourism in Zimbabwe. This study reveals that agritourism is a sustainable diversification strategy that requires collaborative efforts by both the government and the farmers and emphasizes capacity building as one of the main building block for agritourism growth. By integrating agritourism and sustainable development, this study emphasizes on sustainability principles for the betterment of the environment and the local people. Furthermore, the inclusion of the CSF concept is new in agritourism research and it brings in a new perspective that emphasizes on identifying the key factors that stakeholders need to concentrate on for agritourism to thrive in the country.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the farmers in Mashonaland West and Manicaland provinces for their cooperation during the field visits and to the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries and Water and Rural Resettlement for giving the researchers permission to conduct the field visits. This study is part of a PhD research for the first author titled—‘the development of a framework for sustainable agritourism in Zimbabwe’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rudorwashe Baipai

Dr. Rudorwashe Baipai is a lecturer in the Tourism and Hospitality Department at Manicaland State University of Applied Sciences, Mutare, Zimbabwe. Her research interests are in sustainable tourism development, focusing on agritourism, sustainability, and community livelihoods in developing countries.

Oliver Chikuta

Prof Oliver Chikuta is the Dean of the Faculty of Hospitality and Sustainable Tourism at Botho University, Gaborone, Botswana. His research interests are in nature-based tourism, sustainable and heritage tourism, customer service, and tourism marketing with a particular focus on universal accessibility in tourism.

Edson Gandiwa

Prof. Edson Gandiwa is the Director of Scientific Services at the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Authority. His research interests are in community-based natural resource management with a particular focus on wildlife conservation.

Chiedza N. Mutanga

Dr. Chiedza Ngonidzashe Mutanga is a senior research fellow in sustainable tourism at the Okavango Research Institute, University of Botswana. Her research interests are in sustainable tourism development, with a particular focus on nature-based tourism, protected area tourism, and community livelihoods

References

- Agüera, F. O. (2013). Stakeholder theory as a model for sustainable development in ecotourism. Turydes, 6(15), 1–18.

- Alhaddi, H. (2016). Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review. ResearchGate, 1(2), 6. March 2015. https://doi.org/10.11114/bms.v1i2.752

- Amberg, M., Fischl, F., & Wiener, M. (2005). Background of critical success factor research: Working Paper No. 2/2005. Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, 2. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0001116

- Ammirato, S., Felicetti, A. M., Raso, C., Pansera, B. A., & Violi, A. (2020). Agritourism and sustainability: What we can learn from a systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(22), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229575

- Arroyo, C. G., Barbieri, C., Sotomayor, S., & Knollenberg, W. (2019). Cultivating women’s empowerment through agritourism: Evidence from Andean communities. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(11), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113058

- Attila, K., & Petres, S. (2017). Sustainable development. theory or practice? ResearchGate. August. https://doi.org/10.5593/sgem2017/54/S23.049.

- Azevedo, S., & Barros, M. (2017). The application of the triple bottom line approach to sustainability assessment: The case study of the UK automotive supply chain. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 10(2Special Issue), 286–322. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.1996

- Barbieri, C. (2019). Agritourism research: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-05-2019-0152

- Barbieri, C., & Streifeneder, T. (2019). Agritourism advances around the globe: A commentary from the editors. Open Agriculture, 4(1), 712–714. https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2019-0068

- Bhatta, K., Itagaki, K., & Ohe, Y. (2019). Determinant factors of farmers ’ willingness to start agritourism in Rural Nepal. Open Agriculture, 4(1), 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2019-0043

- Biddulph, R., Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. (2018). Introducing inclusive tourism. An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1486880

- Brandano, M. G., Osti, L., & Pulina, M. (2018). An integrated demand and supply conceptual framework: Investigating agritourism services. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(6), 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2218

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology; in qualitative research in psychology. Uwe Bristol, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis thematic analysis. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, 2, 57–71.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Broccardo, L., Culasso, F., & Truant, E. Unlocking value creation using an agritourism business model. (2017). Sustainability, 9(9), 1618. Switzerland), 9(9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091618

- Brune, S., Knollenberg, W., Stevenson, K., Grether, E., & Barbieri, C. (2018). Introducing a framework to assess agritourism ’ s impact on agricultural literacy and consumer behavior towards local foods. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/ttra/2018/Academic_Papers_Visual/28

- Bruno, A., & Leidecker, J. (1984). Identifying and using critical success factors in long-range planning. 17(1), 23–32.

- Bruno, C. V., & Rockart, J. F. (1981, June). A Primer on Critical Success Factors. Sloan School of Management.

- Bwana, M. A., Olima, W. H. A., Andika, D., Agong, S. G., & Hayombe, P. (2015). Agritourism: Potential socio-economic impacts in Kisumu County. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 20(3), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-20377888

- Chaiphan, N. (2016). Study of Agritourism in Northern Thailand : Key Success Factors and the future of the Industry. Thammasat University.

- Chase, L., Conner, D., Quella, L., Wang, W., Leff, P., Feenstra, G., Singh-Knights, D., & Stewart, M. (2019). Multi-State Survey on Critical Success Factors for Agritourism. Sustainable Tourism and Outdoor Recreation.

- Chase, L., & Ramaswamy, V. (2007). Resources for Agritourism Development: Successes and Challenges in Agritourism. Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. http://www.agmrc.org

- Chase, L., Stewart, M., Schilling, B., Smith, B., & Walk, M. (2018). Agritourism: Toward a conceptual framework for industry analysis. Journal of Agriculture, Food, Systems, and Community Development, 8(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2018.081.016

- Chatterjee, S., & Prasad, M. V. D. (2019a). The evolution of agri-tourism practices in India: some success stories. Madridge Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, 1(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.18689/mjaes-10001041

- Chatterjee, S., & Prasad, M. V. D. (2019b). The evolution of agri-tourism practices in India: some success stories. Madridge Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, 1(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.18689/mjaes-1000104

- Chikuta, O., & Makacha, C. (2016). Agritourism: A Possible Alternative to Zimbabwe’s Tourism Product? Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 4(3), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2169/2016.06.001

- Chiromo, P. (2016). Social Innovation and Agrotourism Growth in Rural Communities of Zimbabwe. Chinhoyi University of Technology.

- Chitsike, F. (2003). A critical analysis of the land reform programme in Zimbabwe a critical analysis of the land reform programme in Zimbabwe. 2nd FIG Regional Conference, Marrakech, Morocco, 1–12.

- Ciolac, R., Adamov, T., Iancu, T., Popescu, G., Lile, R., Rujescu, C., & Marin, D. (2019). Agritourism-A sustainable development factor for improving the ‘health’ of rural settlements. case study Apuseni mountains area. Sustainibility, 11(5), 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051467

- Comen, T. (2017). Critical success factors for agritourism entrepreneurs. The 2nd International Congress on Marketing, Rural Development, and Sustainable Tourism, 91(June 13– June 15), 399–404.

- Cristina, M., Iamandi, I., Munteanu, S. M., Ciobanu, R., Țarțavulea (Dieaconescu), R., & Lădaru, R. (2017). Incentives for developing resilient agritourism entrepreneurship in rural communities in Romania in a European Context. Sustainability Science, 9(12), 2205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122205

- Dias, C. S. L., Rodrigues, R. G., & Ferreira, J. J. (2019). Agricultural entrepreneurship: Going back to the basics. Journal of Rural Studies, 70(December 2018), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.06.001

- Elkington, J. (1994). Enter the triple bottom line. The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up, 1(1986), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849773348

- Eshun, G., & Mensah, K. (2020). Agrotourism Niche-Market in Ghana: A multi-stakeholder approach. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(3), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-21

- Forbord, M., Schermer, M., & Grießmair, K. (2012). Stability and variety e Products, organization and institutionalization in farm tourism. Tourism Management, 33(4), 895–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.015

- Freeman, R. E. 2010. Stakeholder Theory : The State of the Art. November 2014. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2010.495581

- Fuentes-Medina, S., Hernandez-Estarico, M., & Morino-Morrero, E. (2018). Study of critical success factors of the emblematic hotels through the analysis of content of online opinions: The case of the Spanish Tourist Parodors. 27(1), 42–45.

- Genovese, D., Culasso, F., & Giacosa, E. (2017). Can livestock farming and tourism coexist in mountain regions? A new business model for sustainability. Sustainability, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112021

- Guvamombe, I. (2019, August 3). Farm tourism trendy, refreshing. Herald.

- Karampela, S., Papapanos, G., & Kizos, T. (2019). Perceptions of agritourism and cooperation: Comparisons between an Island and a mountain region in Greece. Sustainability, 11 (3), 680. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030680

- Kazmina, L., Makarenko, V., Provotorina, V., & Shevchenko, E. (2020). Rural tourism (agritourism) of the Rostov region: Condition, problems and development trends. E3S Web of Conferences 175, Russia, 10001.

- Kearney, A. T. (2009). Green winners: The performance of sustainability-focused companies during the financial crisis as https://doi.org/10.1021/cen-v077n027.p030.

- Khairabadi, O., Sajadzadeh, H., & Mohammadianmansoor, S. (2020). Assessment and evaluation of tourism activities with emphasis on agritourism: The case of Simin Region in Hamedan City. Land Use Policy, 99(September), 105045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105045

- Khartishvili, L., Muhar, A., Dax, T., & Khelashvili, I. (2019). Rural tourism in Georgia in transition: Challenges for regional sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020410

- Khazaei, A., Elliot, S., & Joppe, M. (2015). An application of stakeholder theory to advance community participation in tourism planning: The case for engaging immigrants as fringe stakeholders. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(7), 1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1042481

- Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data : AMEE Guide. In AMEE Guide No. 131 (pp. 1–9). Medical Teacher. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

- Lester, S. E., Ru, E. O., Mayall, K., & Mchenry, J. (2017). Exploring stakeholder perceptions of marine management in Bermuda. Marine Policy, 84(August), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.08.004

- Liu, S., Yen, C., Tsai, K., & Lo, W. (2017). A conceptual framework for agri-food tourism as an eco-innovation strategy in small farms. Sustainability, 9(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101683

- Lucha, C., Ferreira, G., Walker, M., & Groover, G. (2016). Pro fi tability of Virginia ’ s Agritourism Industry : A Regression Analysis. https://www.cambridge.org/core

- Lupi, C., Giaccio, V., Mastronardi, L., Giannelli, & Scardera, A. (2017). Exploring the future of agritourism and its contribution to rural development in Italy. 64(2017), 383–390.

- MacKay, M., Nelson, T., & Perkins, H. C. (2019). Agritourism and the adaptive re-use of farm buildings in New Zealand. Open Agriculture, 4(1), 465–474. https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2019-0047

- Marais, M., Du Plessis, E., & Saayman, M. (2017). A review on critical success factors in tourism. 31(2017), 1–12.

- Mcgehee, N. G., & Mcgehee, N. G. (2009). An agritourism systems model: A Weberian perspective an agritourism systems model: A Weberian perspective. Journal of Sustainable. Tourism, 9582. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost634.0.

- Mylonopoulos, D., Moira, P., & Papagrigoriou, D. A. (2017). The Institutional Framework of the Development of Agritourism in Greece. Journal of Tourism and Leisure Studies, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.18848/2470-9336/cgp/v02i01/1-15

- Nguyen, T. (2016). Stakeholder model application in tourism development in Cat Tien, Lam Dong. Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 1(1), 73–95.

- Palmi, P., & Lezzi, G. E. (2020). How authenticity and tradition shift into sustainability and innovation: Evidence from Italian agritourism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155389

- Phillip, S., Hunter, C., & Blackstock, K. (2010). A typology for defining agritourism. Tourism Management, 31(6), 754–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.001

- Prasanshakumari, J. A. (2016). Possibility of agritourism development for sustainable rural development in Sri Lanka. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 21(8), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2108041216

- Priyanka, S., & Kumah, M. (2016). Identifying the potential of agri-tourism in India: Overriding challenges and recommend strategies. International Journal of Core Engineering & Management, 3(3), 7–14.

- Purvis, B. (2018). Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

- Rockart, J. F. (1979). Chief executives define their own data needs. Havard Business Review, 57(2), 81–93.

- Rogerson, C. M., & Rogerson, J. M. (2014). Agritourism and local economic development in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography Socio–Economic Series, 26(26), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.2478/bog-2014-0047

- Roman, M., Roman, M., & Prus, P. (2020). Innovations in Agritourism: Evidence from a Region in Poland. Sustainability, 12(12), 4858. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124858

- Saftic, D., Tezak, A., & Luk, N. (2011). Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Organisational Science Development, Portoroz, Slovenia.

- Sawe, B. J., Kieti, D., & Wishitemi, B. (2018). A conceptual model of heritage dimensions and agrotourism: Perspective of Nandi County in Kenya. Research in Hospitality Management, 8(2), 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2018.1553373

- Scoones, I., Marongwe, N., Mavedzenge, B., Murimbarimba, F., Mahenehene, J., & Sukume, C. (2011). Zimbabwe ’ s Land Reform: A summary of findings.

- Slaper, T. F. (2011). The triple bottom line: what is it and how does it work? the triple bottom line defined. Indiana Business Review, 86(1), 4–8. http://www.ibrc.indiana.edu/ibr/2011/spring/article2.html

- Sterling, E. J., Betley, E., Sigouin, A., Gomez, A., Toomey, A., Cullman, G., Malone, C., Pekor, A., Arengo, F., Blair, M., Filardi, C., Landrigan, K., & Luz, A. (2017). Assessing the evidence for stakeholder engagement in biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 209, 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.02.008

- Tanyanyiwa, I. V. (2017). Exploring the potential of agritourism to innovative farmers in Zimbabwe. 11th Zimbabwe International Research Symposium.

- Tugade, L. O. (2020). Re-creating farms into Agritourism: Cases of selected micro-entrepreneurs in the Philippines. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9(1), 1–13.

- van Zyl, C. (2019). The size and scope of agri-tourism in South Africa (Issue July). North-West University.

- Woodcraft, S. (2015). Understanding and measuring social sustainability. Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, 8(2), 133–144.

- Xavier, F., Tuokuu, D., Debar, S., & Ebo, R. (2019). Sustainable development in Ghana ’ s gold mines: Clarifying the stakeholder ’ s perspective. Journal of Sustainable Mining, 18(2), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsm.2019.02.007

- Yamagishi, K., Gantalao, C., & Ocampo, L. (2021). The future of farm tourism in the Philippines: Challenges, strategies and insights. Journal of Tourism Futures. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-06-2020-0101

- Yildirim, G., & Kilinc, C. C. (2018). A study on the farm tourism experience of farmers and visitors in Turkey. Journal of Economic & Management Perspectives, 12(3), 5–12.

- Zasada, I., Häfner, K., Schaller, L., Zanten, B. T., Van Lefebvre, M., Malak-Rawlikowska, A., Nikolov, D., Rodríguez-Entrena, M., Manrique, R., Ungaro, F., Zavalloni, M., Delattre, L., Piorr, A., Kantelhardt, J., Verburg, P. H., & Viaggi, D. (2017). Geoforum a conceptual model to integrate the regional context in landscape policy, management and contribution to rural development: Literature review and European case study evidence. Geoforum, 82(July 2016), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.012