Abstract

This study was planned to investigate the effect of distance education students’ attitudinal, social, and control beliefs on their mobile learning usage at the University of Ghana and the University of Education, Winneba. The Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour (DTPB) was modified to explain how students’ attitude, subjective norms, and behavioural control of mobile learning influenced their current mobile learning usage. The study used an explanatory sequential mixed-method approach. Congruent to that, structured questionnaires were administered to 400 distance learners selected by multi-stage sampling technique, and 20 distance learners selected by random sampling technique were interviewed via phone to collect data. Using correlation and multiple linear regression analysis, as well as hypothesis testing, the findings showed that, the university students’ attitudes towards mobile learning, subjective norms, and behavioral control insignificantly influenced their ongoing mobile usage thus providing meek support for the research model. However, it was found that university students’ mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy significantly affect their attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control respectively of their mobile learning usage. This supports the research model and can be inferred that university students’ mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy indirectly influence their mobile learning usage. The results of this study will enable educational institutions to engage in better strategic planning and implementation of mobile learning on a wider scale focusing on students’ behavioral, social, and control factors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study investigated, impact of mobile learning usage among distance learners in public universities. Students’ mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy were found to have significant effects on their attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control, respectively. These findings have important implications for educators and policymakers seeking to promote effective distance learning practices. By recognizing the importance of mobile learning and factors that influence students’ attitudes and behaviors, instructors can design more engaging and effective distance learning experiences that promote student success. As we continue to navigate challenges of remote education, it is essential that emerging technologies is leveraged to improve access to education for all. By prioritizing mobile learning and supporting students’ innovativeness, peer networks, and self-efficacy, learners can be empowered to take control of their education and achieve their goals. The research team would continue working towards this important goal through future research and advocacy.

Introduction

The advancement of technology has fueled the growth of distance education throughout the years since the 20th century (Schultze, Citation2011). The development and increased mobile cellular subscription have caused the transition of distance education from electronic learning, which is learning reinforced by digital devices and media, to mobile learning. Mobile learning is a type of electronic learning that uses mobile devices or technologies and wireless transmission for teaching and learning (Crompton, Citation2013). According to Wong et al. (Citation2015), distance education has been influenced by the rapid growth of mobile-cellular subscriptions and youth use of mobile technologies. The high rate of mobile-cellular penetration by young people has extensive consequences for the global development of distance education because young people now occupy distance educational institutions (Tagoe & Abakah, Citation2014).

This is the reason the University of Ghana (UG) and the University of Education, Winneba (UEW) launched integrated Mobile Learning Platforms and programmes to enhance the effective utilization of mobile learning technologies for teaching and learning. The UG and UEW distance learners’ mobile activities include the use of mobile devices, such as mobile phones, tablets, and phablets to obtain course materials, conduct examinations, assignments, quizzes, and chat among students and tutors via the Sakai and the Moodle Learning Management System platforms, respectively.

The successful execution of mobile learning in the context of distance education is not dependent on the effectiveness of the Learning Management Systems and mobile technologies only but to a considerable extent, the factors that influence students’ mobile learning adoption or usage (Gatotoh et al., Citation2018). The factors that influence distance students’ current mobile learning usage are therefore crucial considerations for effective mobile learning implementation. Students’ attitudes, technological readiness, peer influence, self-efficacy, and personal innovativeness have been identified as determinants of their mobile learning intentions and adoption (Ayub et al., Citation2017). Social scientists such as Azizi and Khatony (Citation2018) and Buabeng-Andoh (Citation2018) identified the three main antecedents of mobile learning intentions as attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control.

Attitude refers to the habits of mind and feelings that affect how an individual thinks and behaves and it is influenced by the ease of use, perceived usefulness, and compatibility (Dashti & Aldashti, Citation2015). Jaradat (Citation2014), and Ajzen (Citation2019) referred to the subjective norm as social influence and described it as a person’s opinion about what other important people in his or her society may consider him/her to be if he/she should execute a particular behaviour. Cheon, Crooks, Chen & Song (Citation2012) measured subjective norms by two precursors: instructors’ influence and students’ influence. Perceived behavioural control is referred to as people’s perception of the degree to which they believe they could perform specific conduct (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010) and is theorized as a construct of three parts: self-efficacy, resource facilitating condition, and technical facilitating condition (Ajzen, Citation2019).

Students’ technological readiness is their ability to adapt to the technology, the ease of use, and the perceived usefulness of that technology (Ajzen, Citation2019). Mobile learning peer readiness is referred to as the tendency of the colleagues or mates of students to embrace and use mobile technologies to undertake learning tasks or the extent to which they are willing to use mobile technologies as a medium for learning (Parasuraman & Colby, Citation2015). Peer influence can be described as the extent to which a peer’s readiness or usage of mobile learning affects students’ actual mobile learning utilization. Mahat et al. (Citation2012) defined self-efficacy as a person’s valuation of his or her own ability to plan, organize, and regulate their actions to achieve a particular task.

In general, theoretical, and empirical studies in other countries support the determination of factors that influence students’ mobile learning intentions and usage; however, this cannot be said for Ghana, as few studies on the topic have really been undertaken in Ghanaian universities. Tagoe and Abakah (Citation2014), Buabeng-Andoh (Citation2018), and Kankam (Citation2020) did research in this area with distance education students at the University of Cape Coast and the University of Ghana respectively. These studies focused on one institution and were futuristic, in that they were designed to ascertain students’ intentions regarding the adoption of mobile learning. Furthermore, apart from the dearth of literature, little or none of the research in Ghana and elsewhere used the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour (DTPB).

The concepts of attitude, subjective norm, behavioural control, self-efficacy, and innovativeness were utilized in studies in Ghana and internationally to determine students’ mobile learning intentions (Buabeng-Andoh, Citation2018; Mahat et al., Citation2012). However, few, if any, researchers have combined all these constructs in a single study to gain a more comprehensive picture. In addition, most studies concentrated on the application of various quantitative research methods (Cheon et al., Citation2012; Eltaveb & Hegazi, Citation2014; Iqbal & Qureshi, Citation2012). Out of forty-five empirical studies reviewed and documented, four adopted a mixed method and none used a qualitative approach.

The purpose of this study was to use explanatory sequential mixed method and the DTPB to examine the extent of the relationship that exists between students’ attitudinal factors (attitude, subjective norms, behavioural control) and their mobile learning usage, and the relationship between students’ external beliefs (innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy) and their attitudinal factors. The goal was to investigate distance education students’ present or actual mobile learning usage instead of their intentions as students’ opinions might change over time when they start using mobile learning.

Determine factors that influence university students’ current mobile learning behaviour in terms of their attitudes, what other important people in their society may consider being the right thing to do, and their ability and control to use mobile technology for learning.

Assess if university students’ ability to adapt to mobile learning technology, tendency to embrace and use mobile technologies to undertake learning tasks, and capability to plan, organize, and control their actions to achieve a particular task using mobile devices significantly influence their current mobile learning usage.

Theoretical framework

This study is primarily embedded in the DTPB which is an improvement to the TPB and TRA. The DTPB provides a multidimensional belief framework for determining predecessors of individual behavioural and social antecedents or constructs of intention, to ensure that the constructs have a resilient effect on the use of a specific behaviour. In other words, the DTPB stresses the identification of various belief components that govern the three immediate precursors of behavioural intentions namely attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, which TRA and TPB disregard. Sundar and Kanimozhi (Citation2018) noted that the DTPB provides an improved method for explaining people’s intentions to adopt mobile technology. The DTPB classified the antecedents of attitude into three external beliefs factors namely perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and compatibility. The DTPB deconstructed subjective norms into two normative belief factors: peer influence and superior influence and decomposed perceived behavioural control into three control belief factors namely self-efficacy, resource facilitation, and technology facilitation. Ajzen (Citation2019) explained that an individual’s behavioural intentions determine his or her actual behaviour.

The DTPB has been adapted in predicting customers’ intentions toward the adoption or use of goods and services. Gangwal and Bansal (Citation2016) adapted the decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour model for exploring customers’ adoption of mobile commerce. The authors decomposed normative belief into family, friends, and mates’ influence, decomposed control belief into self-efficacy, and used personal innovativeness as an antecedent of attitude toward the adoption of mobile commerce. Hsu et al. (Citation2006) modified the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour to assess customers’ usage of mobile coupons. The author decomposed attitude into four constructs: perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, compatibility, and personal innovativeness. Perceived behavioural control was determined by self-efficacy, and the subjective norm was determined by the primary group of classmates. Apart from the dearth of research in Ghana, none of the three studies among the forty-five studies reviewed adopted or adapted the DTPB in explaining students’ mobile learning intentions or usage in universities in Ghana. Contrary to Hsu et al. (Citation2006), Kanimozhi and Sundar (Citation2017), and Keskin and Metcalf (Citation2011), the research model of this study sought to measure the prior mobile learning intentions because the students’ mobile learning was ongoing. Another adaptation to the DTPB is that students’ actual attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control were investigated. Moreover, students’ mobile learning attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural were determined by single variables; innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy respectively contrary to Gangwal and Bansal (Citation2016) and Tao and Fan (Citation2017).

Mobile Learning

Mobile learning is any form of educational delivery in which the primary technologies are handheld devices and wireless transmission (Kankam, Citation2020). Crompton (Citation2013) explained that mobile learning can occur in multiple contexts. In the context of distance education, Kukulska-Hulme et al. (Citation2011) referred to mobile learning as the use of mobile applications for distance education. Smartphones, PDAs, PCs, iPods, MP4 and MP3 players, Notebook computers, Laptops, digital cameras, and gaming consoles are examples of mobile learning devices (Hockly, Citation2013).

Using mobile learning technologies, diverse types of mobile learning have developed, including self-directed, behavioural, cognitive, informal, collaborative, and situated learning. The flexible features of mobile technologies, which allow students to learn at their own pace and on their own schedule, facilitate self-directed learning. Behavioural learning arises when students use mobile devices to provide a solution (response) to a problem (stimulus) when they collaborate with their tutors (Donham, Citation2010; Serhat, Citation2022). Cognitive learning occurs when mobile technology’s multimedia features offer animations, images, video, audio, MMS, SMS, podcasting, and e-mails to aid in the acquisition, processing, and delivery of information for learning (Keskin & Metcalf, Citation2011). Informal learning happens when students acquire knowledge independently from informal sources and incorporate it into formal education knowledge using mobile learning technologies. Collaborative learning occurs when distance education students use mobile technologies to effectively create and share information and Situated learning transpires when authentic digital Learning Management Systems and other ubiquitous computing environments provide appropriate context and opportunities for students to interact with their tutors in a convenient manner using mobile learning tools to access the right information wherever and whenever they need it (Wong et al., Citation2015).

Mobile learning in university education

Mobile learning has been widely integrated into distance education in recent times because of the high mobile-cellular subscription rate and the positive affordances provided by the features of mobile learning technologies. According to (International Telecommunication Union (2021), the Global mobile-cellular subscription rate in 2021 was 110% per 100 people. In Ghana, the mobile voice, and data rates in 2020 were 131% and 86% respectively with forty million subscribers (National Communications Authority (Citation2021). Moreover, the mobility, portability, interactivity, and flexibility feature of mobile learning devices enhance accessibility, quality, equality, and flexibility in distance education (Al Hassan, Citation2015). Díez-Echavarría et al. (Citation2018) therefore emphasized that mobile learning should be made compulsory in all universities due to the significant role mobile learning provides for the improvement of distance education.

Experts and researchers from tertiary educational institutions around the world have indicated extensive deployment of mobile learning for the development of education. For instance, forty-six experts indicated that mobile learning could facilitate the transfer of educational content, collaborative learning, immediate feedback, and interaction among students and lecturers (Al Hassan, Citation2015). University students in Thailand showed highly positive mobile learning intentions (Jairak et al., Citation2014). In the Arab Gulf region, 99% of 437 students in Oman and UAE used smartphones for learning (Al-Emran et al., Citation2016). About 98.7% of 400 distance learners at the University of Ghana owned a smartphone and 73.1% of the students had the intention to use mobile learning (Tagoe & Abakah, Citation2014). There was a high intention of distance learners in the sandwich programme at the university of Ghana toward the adoption of mobile learning (Kankam, Citation2020). The distance education students in the University of Ghana and the University of Education, Winneba access learning materials from the predetermined programme via the SAKAI and Moodle LMS respectively using mobile devices. The features of the LMS allow the students to talk, chat, negotiate and collaborate to achieve the goals of their learning activities.

Determinants of students’ mobile learning

Studies have identified attitudinal, social, and behavioural factors that influence students’ mobile learning intentions, adoption, or usage. Scholars such as Cheon et al. (Citation2012), Istiyowati and Prati (Citation2019), and Buabeng-Andoh (Citation2018) found students’ attitudes, behavioural control, and subjective norms as strong and direct determinants of their mobile learning intentions and usage. Jaradat (Citation2014), and Korucu and Bicer (Citation2018) confirmed the attitude of DE students as a direct and strong predictor of their mobile learning intentions and usage. Similarly, Dashti and Aldashti (Citation2015), Caldwell (Citation2014), and Al-Emran et al. (Citation2016) established that university students’ mobile learning behaviour is influenced positively by their attitude.

The connection between students’ subjective norm and their intentions towards actual usage of mobile learning had been established by researchers such as Azizi and Khatony (Citation2018) and Al-Hujran et al. (Citation2014). Studies by Altawallbeh et al. (Citation2015) had proven a positive and strong relationship between subjective norms and mobile learning intentions and usage by university undergraduates, instructors, and administrators. Perceived behavioural control might moderately influence behavioural intentions (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010). In assessing students’ mobile learning intentions in Ghana, the studies by Tagoe and Abakah (Citation2014) and Buabeng-Andoh (Citation2018) revealed that the subjective norm of distance learners of public universities has a significant influence on their mobile learning intentions. Cheng and Huang (Citation2013) established perceived behavioural control as a strong and direct influence on students’ mobile learning intentions.

The hypothesis development and research model

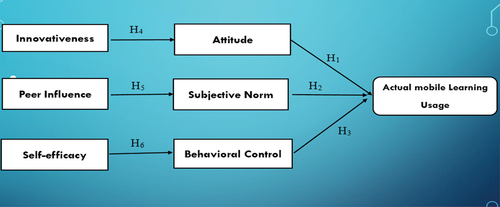

The Research Model assumes that students’ mobile learning attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control tend to significantly influence their mobile learning actual usage as shown in Figure . This corroborates the findings of studies conducted by Kanimozhi and Sundar (Citation2017) which established a positive relationship between customers’ intentions toward the adoption of 4 G mobile services in India using the DTPB. The results indicated that customers’ attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control influenced their decision to adopt the new 4 G mobile services. In this study since students have started using mobile learning technologies, their actual attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control of mobile learning were determined. Using single variables, peer influence, self-efficacy, and innovativeness measured subjective norm, behavioural control, and attitude, respectively.

The use of innovativeness as an antecedent of attitude in this study is consistent with the DTPB and the results of the review of empirical studies. The DTPB argues that the ease of use and usefulness of behaviour determines one’s attitude toward it. A survey conducted by Iqbal and Qureshi (Citation2012) and Ngafeeson and Sun (Citation2015) established that students’ innovativeness influenced their perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of mobile learning.

In another study, Hong et al. (Citation2013) established a positive relationship between personal innovativeness and perceived usefulness, and the perceived ease of use of mobile learning intentions by administrators in Japan. It can be inferred that as ease of use and perceived usefulness influence attitudes and personal innovativeness influences ease of use and perceived usefulness, it follows that personal innovativeness can influence attitude. Consequently, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness as well as compatibility as precursors of attitude in DTPB are replaced by personal innovativeness as a single-item antecedent in the conceptual framework. This adaptation is also supported by findings of a study conducted by Gangwal and Bansal (Citation2016) which affirmed that personal innovativeness has a direct and positive influence on an individual’s attitudes toward a behaviour. Therefore, the following hypotheses were drawn:

H1:

University students’ attitudes toward mobile learning significantly influence their current mobile learning usage.

H2:

University students’ subjective norms of mobile learning significantly influence their current mobile learning usage.

H3:

University students’ behavioural control of mobile learning significantly influences their current mobile learning usage.

H4:

University students’ mobile learning innovativeness positively influences their attitude toward their current mobile learning usage.

H5:

Peer influence positively influences university students’ subjective norms of their current mobile learning usage.

H6:

University students’ mobile learning self-efficacy positively influences their behavioural control of current mobile learning usage.

Research model

Methodology

Method

The philosophical premise of this study was contextualized within the pragmatic paradigm. Congruent with the pragmatic paradigm, the mixed-method approach was espoused. The adoption of a mixed method

was underpinned by two major justifications. The first rationale was for the expansion of the study to widen the scope of inquiry by gathering both closed-ended quantitative data and open-ended qualitative data. Second, both quantitative and qualitative data set was used to produce wider implications in the study conclusions.

Study population

The Study population consisted of 11,550 distance learners from the ten Learning Centres of the University of Ghana and 26,814 Distance Education Learners from the thirty-five Learning Centres of the University of Education, Winneba across twelve Regions of Ghana. The target population comprised students who had previously used mobile learning for at least one semester and those who were currently using mobile learning. The accessible population was made up of students who were available and willing to participate at the time of the research. A total sample of 400 students was selected using the method of determination of sample size by Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) and 12 students were selected by random sampling for qualitative data collection.

The survey instrument constituted six constructs comprising 27 items: subjective norm (5 items), Attitude (5 items), Behavioural Control (4 items), Peer Influence (5 items), Personal Innovativeness (4 items), and self-efficacy (4 items). The questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree = 5, Agree = 4, Neutral = 3, Disagree = 2, and Strongly Disagree = 1). The interview guide was designed to find out the explanations or reasons that accounted for the insignificant relationship between students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control on the use of mobile learning technologies.

Design

The study employed the explanatory sequential mixed-method design, which incorporates qualitative information to clarify quantitative figures. According to Creswell (Citation2014), explanatory sequential mixed methods design in which the researcher first performs a broad quantitative investigation analyzes the findings and then expands on the findings to explain them in more depth with qualitative interviews. This study’s primary interest was in the determination of students’ attitudes, behavioural control, subjective norms, personal innovativeness, self-efficacy, and peer influence toward their present mobile learning usage at the UG and UEW. The study began with quantitative data collection. The second stage was a descriptive and inferential analysis of quantitative data using SPSS version 27. The third stage was the determination of sample size, and the designing of the interview protocol. The fourth stage was qualitative data collection which involved contacting participants and conducting one-on-one phone interviews, and transferring, or storing responses on a computer. Following was the analysis of qualitative data involving thematic analysis to generate major themes and the final qualitative database. The final stage of data collection was triangulation and interpretation of quantitative and qualitative data sources. This encompassed summarizing, comparing, and integrating the two data sources. The final research data was generated by combining the integrated quantitative and qualitative data and the key concepts recognized through reviewing of literature.

Quantitative results

The quantitative data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software version 19 in presenting the study results. Mean, and standard deviation was computed for attitude, subjective norm, behavioural control, innovativeness, peer influence, self-efficacy, and mobile learning usage. Cronbach alpha (CA) coefficients were used to assess the consistency of measurement variables. Considering that the item reliability is shown to be good and acceptable, the study further assessed the composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted. A CR value between 0.7 and 0.90 was satisfactory. The values for the reliability statistics for variables in Tables indicate that the CA and CR coefficients have adequate internal consistency.

Table 1. Reliability Statistics of the dependent variable

Table 2. Reliability Statistics of Independent variables

The coefficients are good and acceptable. The CA and CR of the dependent variable (mobile learning usage) were 0.889 and 0.853, respectively. For the independent variables, the CA range between 0.468 to 0.889, and the CR range from 0.666 to 0.880. Exploratory factor analysis was used to extract the factors for the models specified in this study. Evaluating these items, a factor loading of 0.50 was considered. Hair et al. (Citation2010) stated that an item is acceptable if it loads above 0.50, this was the acceptable factor loading for items.

As show by the discriminant validity values, the values were higher than the cross-correlation with other variables indicating that the items presented are distinct for each construct. As shown by the correlation statistics, it is indicated that there is a positive and significant association between the constructs. Additionally, the AVE for each variable was greater than 0.5, suggesting that the data was sufficient and met the criteria for further analysis as in Table . In assessing the normality of the dependent variable, a normal P-P regression plot that compares the observed cumulative distribution function of the standardized residual to the expected cumulative density function (CDF) of the normal distribution was constructed as shown in Figure below. It is shown that residuals are normally distributed.

Table 3. Correlation Matrix and Discriminant Validity

The square root of AVE is represented by the bold digits across the diagonal.

Mean and standard deviation

In the descriptive results in Table , the mean and standard deviation of responses is presented. A mean value of 2.5 and above indicated agreement with the assertions raised whereas below 2.5 indicated otherwise. Shown by the mean results, it is indicated that Personal Innovativeness (3.96) received the highest mean followed by actual Mobile learning usage (3.88), Peer Influence, Self-Efficacy, Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Behavioural Control followed subsequently by respective means of 3.74, 3.74, 3.67, 3.63, and 3.52. This indicates constructs the respondents agreed with. All the means presented fell within the acceptable agreement region. The standard deviation indicates the dispersion of the responses around the mean response. Three constructs with the highest standard deviations are Self-efficacy (1.06), subjective norm (0.93), and mobile learning usage (0.93). Juxtaposing standard deviations with mean scores, the lowest-scored items relating to these three constructs are 2.68, 2.7, and 2.95, respectively. The lowest-scored items of the other constructs are peer Influence (2.87), behavioural control (2.67), attitude (2.89), and personal innovativeness (3.2). All the least scored items also fell within the acceptable region. It indicates that all the items measuring each construct were accepted by the participants. The participants accept that people who are important to them such as tutors, peers, and family members have an influence on their mobile learning usage. They also agreed that their positive outlook, ability, skills, and confidence to use mobile learning technologies to accomplish coursework quickly have an impact on their present mobile learning usage.

Table 4. Mean and Standard results of students’ mobile learning determinants

Regression model

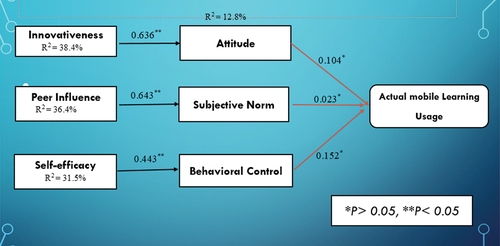

The relationship between the variables discovered in this study was estimated using a regression model (Table ). The multilinear regression model is estimated between Mobile learning Usage and the three independent variables (Attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control). The study determines the overall significance of the model using the F Statistics. There is a significant relationship that exists between Mobile learning Usage and attitude (Table ) and behavioural control, subjective norm (Table ) constructs (F = 12.22, P < 0.05). This means attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control jointly determine actual mobile learning usage. An R-squared of 0.128 indicates that the independent variables explained 12.8% of the actual mobile learning usage of study respondents. The most noteworthy influence on mobile learning utilization is determined to be behavioural control.

Table 5. Regression coefficient (Mobile learning Usage)

Table 6. Regression coefficient (Attitude)

Table 7. Regression coefficient (Subjective norm)

The univariate regression analysis is used to look at a statistical relationship between a dependent (attitude) and an independent variable (personal innovativeness). Personal inventiveness has been discovered to have a significant impact on attitude. With this model, 38.4% of the variations in attitude are explained by personal innovativeness as indicated by (Iqbal et al., 2012; Ngafeeson & Sun, Citation2015).

The next model is a univariate regression analysis investigating a statistical relationship between an independent Peer Influence and a dependent variable Subjective Norm. Peer influence has been established to have a noteworthy influence on the subjective norm. With this model, 36.4% of the variations in subjective norms are explained by peer influence.

The final model is also a univariate regression analysis investigating a statistical relationship between a dependent Behavioural Control and an independent variable Self-Efficacy. Self-efficacy has been found to have a significant impact on behavioural control. With this model, 31.5% of the variations in behavioural control are explained by self-efficacy (Table ). According to Yorganci (Citation2017), students’ self-efficacy is a key factor in determining whether they will adopt a certain mobile learning device.

Table 8. Regression coefficient (Behavioural Control)

Test of hypotheses

Six hypotheses were tested in this study. It is shown that three out of the six hypotheses were supported. H1 proposes that attitude positively affects actual mobile learning usage. As shown in Table , it is indicated that the hypothesis can be rejected, and therefore, it is concluded that the attitude toward mobile learning does not significantly influence the students’ actual mobile learning usage. The subjective norm of students, according to H2, does have a positive effect on their present mobile learning usage. There is little data to suggest that their present mobile learning usage is strongly affected by their subjective norm. The hypothesis cannot be retained. Thirdly, H3 states that behavioural control of mobile learning significantly influences current mobile learning usage. This hypothesis was not supported in this research; hence we infer that students’ behavioural control has an insignificant bearing on their use of mobile learning.

Table 9. Summary of Test Hypothesis

It is indicated that H4 postulates that personal innovativeness influences their attitude toward actual mobile learning. There is sufficient evidence not to discard the hypothesis and claim that personal inventiveness has a significant positive impact on attitudes toward their actual mobile learning. H5 proposed that peers influence university students’ subjective norm of mobile learning, results indicated that peer influence has a noteworthy influence on students “mobile learning subjective norm. Finally, H6 asserted that self-efficacy influences their behavioural control of students” actual mobile learning, thus, the hypothesis cannot be rejected, and we conclude that self-efficacy influences their behavioural control.

The results of the research model

The results show that Hypotheses 1 to 3 were not supported. H1, coefficient of 0.104, t-value of 0.918, p > 0.05; H2, coefficient of 0.023, t-value of 0.212, p > 0.05; H3, coefficient of 0.152, t-value of 1.615, p > 0.01). In other words, actual mobile learning usage was insignificantly influenced by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control. However, the effect of behavioural control was the most followed by attitude. All the hypotheses regarding the relationships between the three attitudinal constructs and their respective antecedents were supported. First, mobile learning innovativeness (H4, coefficient of 0.636, t-value of 15.159, p < 0.05) made a significant effect on attitude. The assumption of the significant relationship between peer influence and the subjective norm was supported (H5, coefficient of 0.643, t-value of 14.419, p < 0.05) and made a positive effect on the subjective norm. Finally, self-efficacy influenced perceived behavioural control (H6, coefficient of 0.443, t-value of 13.023, p < 0.05). Therefore, the results of the Research Model are shown in Figure and Figure below.

Qualitative results

For the hypothesis that was not supported or the constructs that do not have a substantial impact on mobile learning usage, the qualitative results also provided further explanation for these results. The quantitative analysis has indicated that university students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control individually did not significantly influence their actual mobile learning usage. Students were asked to give their take on this finding. Respondents indicated other factors that might influence their present mobile learning usage. The usage of mobile learning platforms, according to respondents, is a result of the COVID-19 epidemic.

That is the current increasing technological advancement due to COVID-19 influencing mobile learning usage. The following are some of the noticeable responses from the participants: For instance, a student specified: I am not motivated or influenced to use mobile learning because of the nature of my mathematical course. You cannot type mathematical symbols. Rather, COVID-19 influenced me to use mobile learning. [UEW: Male, Level 300]. Another said, “My motivation to use mobile learning is a result of COVID-19”. [UG: Male, Level 100]. Similarly, a student confirmed, that COVID-19 influenced her and said, “I am not influenced by my attitude toward using mobile devices to learn but COVID-19 influenced me” [UEW: Female, Level 400].

Other students, however, had different views. They believed their mobile learning attitude, control, peer influence, and age have an impact on their present mobile learning. For instance, some respondents said: “I think my attitude influences my usage of mobile learning” [UG: Male, Level 300], “My control over the use of my mobile device influences me to use mobile learning” [UEW: Female, Level 100], “I am influenced by my colleagues because we share information with the use of mobile devices” [UEW: Male, Level 400], and “I am also motivated to use mobile learning because of my age” [UEW: Male, Level 200].

Some students believed that mobile learning is simple, flexible, and inexpensive is the deciding factor in their decision to do so. Narrating the factors that influenced their mobile learning usage, two students said: “I use my mobile phone for learning because is easy. I can get my information everywhere even in a vehicle [UG: Female, Level 100]. “I use my mobile phone to learn because it is less expensive” [UEW: Male, Level 200].

In summary, confirming the effect of students’ attitudes (their habits of mind and feelings that affected how students think and behaved), subjective norms (students’ opinion about what other important people in their society may consider being the right thing to do), and behavioural control (perceptions about students’ ability to exhibit a specific inclination towards use of mobile learning technologies), students stated that the conduct of their peers, age, attitude, and their control over the use of mobile devices all influenced their present mobile learning usage. However, respondents believed that their attitudes do not influence their mobile learning, but the COVID-19 outbreak and the benefits (such as convenience and flexibility and savings on transportation costs) they derived from using mobile learning influenced them. Students have turned to the internet for more instructional objectives since the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic. Students meet on Zoom for one-on-one conversations occasionally, in addition to the main lecture. Others feel that the ease of use and low transportation cost of using mobile learning affected their mobile learning utilization and these are reasons they stay with mobile learning.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that the dimensions of attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control have a strong, significant linear connection between them as the correlation among them is positive ranging from 0.470 to 0.784. It has also been established that DE students’ attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural, control jointly influence their mobile learning usage as a p-value of F-statistics is 0.005 < 0.05. The respondents confirmed that the behaviour of their peers, their attitude, and their control over the use of mobile devices all influenced their actual mobile learning. Nevertheless, the effect of these constructs together is low because they only explain about 13% of the actual mobile learning usage of study respondents. This means that the students do not have much positive outlook and control over use of mobile learning and were not under much external pressure to use it. A plausible justification for the low effect of the constructs on actual mobile learning usage is that, in isolation, all three constructs were found to insignificantly influence students’ actual mobile learning usage. Their respective p-values are all greater than the 0.05 significance level.

Hypothesis results showed that claims about the three constructs were not supported. Also, as shown by the regression analysis, as DE students’ attitude in isolation increases by unit degree, students’ actual mobile learning usage will increase by 10.4% as students’ subjective norm increases by unit degree, students’ actual mobile learning usage will increase by only 2.3%, and when behavioural control increase by unit degree, will cause students’ actual mobile learning to increase by 15.2%. The respondents might think that they are not prepared for mobile learning usage as some students have said that they are not influenced by their attitudes toward using mobile learning. Consistent with this finding is the results of the study by Al-Hujran et al. (Citation2014) in Saudi Arabia which established that students’ behavioural control insignificantly influenced their mobile learning usage. Contrary, Cheon et al. (Citation2012), Istiyowati and Prati (Citation2019), and Buabeng-Andoh (Citation2018) found students’ attitudes, behavioural control, and subjective norm as direct determinants of their mobile learning intentions and usage.

A plausible suggestion of this finding is the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ability to carry mobile learning anywhere and at any time, its ease of use, and its low cost, and students’ demographic factors as indicated by the respondents might account for 87% of the unexplained determinants of students’ actual mobile learning usage. Confirming this finding, study participants explained that they are not influenced by their attitudes to utilize mobile learning but the outbreak of COVID-19 and the benefits they enjoy of using mobile learning influence them to continue to use it. It is implied that these factors are important and crucial determinants of DE students’ present mobile learning usage. The COVID-19 pandemic is found to be an important determinant to the extent that even mathematics students who normally cannot type mathematical symbols with their mobile phones, declared that they were obliged to use mobile learning because of the effect of COVID-19.

Based on the findings, the DE students’ mobile learning personal innovativeness significantly influenced their attitude towards their actual mobile learning. The F-statistics of personal innovativeness produces a p-value<0.05. The hypothesis test supported the claim about the relationship between students’ innovativeness and attitude toward mobile learning. These indicate that most students who are engaged and willing to learn more about mobile learning and find it simple and beneficial have a favorable attitude toward its use. The students were assumed to be conversant with the use of mobile learning as they are currently using it or had used it for at least one semester. The finding is a confirmation of the results of a study by Gangwal and Bansal (Citation2016) which established that personal inventiveness influences an individual’s attitude toward behaviour in a positive way. The result indicates that personal innovativeness alone explains 38.4% of students’ attitudes towards their actual mobile learning which means that DE students’ innovativeness is a great determinant of their mobile learning attitude. Another significant finding is that the positive coefficient of regression implies that as DE students’ personal innovativeness in isolation increases, their average attitude toward the use of mobile learning will also increase. That is, as DE students’ innovativeness increases by a unit degree, students’ average attitude toward actual mobile learning usage will increase by 63.6%. It can be deduced therefore that DE students’ innovativeness can significantly and directly influence students’ mobile learning usage.

The findings of this study showed that DE students’ subjective norms concerning actual mobile learning were strongly influenced by the influence of their peers. The F-statistics of peer influence generated a p-value<0.05. This suggests that most colleagues of the participants either possess good phones or have adequate skills to use mobile learning. This is corroborated by Cheon et al. (Citation2012) who established that 87.2 percent of 234 participants in American higher education institutions were ready to deploy mobile learning. Peer influence alone accounts for 36.4 percent of students’ subjective norms of their actual mobile learning in this study. This means that the influence of peer influence on DE students’ actual mobile learning usage is enormous. Also, a positive coefficient of regression means that as DE peer influence in isolation increases, their average subjective norm of actual mobile learning usage will also increase. That is, as peer influence increases by unit degree, students’ average subjective norm of actual mobile learning usage will increase by 64.3%. It can be presumed that DE peer influence can significantly and directly affect their actual mobile learning usage consistent with findings by Hussein (Citation2018) which revealed the direct impact of students’ peer influence on their mobile learning usage. Respondents of this study confirmed that their mates had an impact on how they use mobile learning.

Students’ self-efficacy has a significant influence on their behavioural control toward actual mobile learning usage. The F-statistics of self-efficacy result in a p-value<0.05. It suggests that most of the participants have confidence and the ability to organize, control, and take necessary actions to use mobile learning successfully. Another significant finding is that DE students’ mobile learning self-efficacy alone explains 31.5% of students’ behavioural control toward mobile learning. Having a positive regression coefficient, it is shown that as DE students’ self-efficacy in isolation increases, their average behavioural control toward the use of mobile learning will also increase. As self-efficacy increases by a unit degree, students’ average behavioural control of actual mobile learning usage will increase by 44.3%. It is acknowledged that DE students’ self-efficacy can significantly influence behavioural control toward actual mobile learning usage. According to Yorganci (Citation2017), students’ self-efficacy is a significant determinant of mobile learning device usage. In Kenya, Gatotoh et al. (Citation2018) discovered a significant link between health trainees’ self-efficacy and mobile learning usage.

The insignificant effect of participants’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control on their mobile learning usage results provide modest support for the DTPB model. On the other hand, the results offer strong support for the research model regarding the effect of students’ innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy of their attitude, subjective norms, and behavioural control of mobile learning usage respectively.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore university students’ actual mobile learning usage based on the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour. The study examined the effect of students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control on their mobile learning usage at the University of Ghana and the University of Education, Winneba. The participants were students who had used mobile learning for at least one semester and continued using it. Since the students have started using mobile learning, the actual impact of their attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control on their actual mobile learning usage were determined. Inconsistent with Tagoe and Abakah (Citation2014) and Cheon et al. (Citation2012), single antecedents measured the study constructs. Subjective norm is measured by peer influence, behavioural control by self-efficacy, and attitude is measured by students’ innovativeness. Tagoe and Abakah (Citation2014) measured perceived behavioural control using two constructs; self-efficacy and learner autonomy and Cheon et al. (Citation2012) measured subjective norms by Instructors’ readiness and peer readiness and behavioural control by perceived self-efficacy and learning autonomy.

Most university students’ mobile learning attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control in separation and collectively do not significantly influence their present mobile learning usage although there is a strong association among these constructs. From this, it can be concluded that respondents do not exercise control over the use of mobile learning and are not under pressure from their colleagues to use mobile learning. It is established that the enthusiasm of the students to stay with mobile learning is influenced by the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic as disclosed by most respondents including mathematics students. In another dimension, the results show that students’ ability to carry mobile learning anywhere and anytime, the ease of use, and the low transport costs for using mobile learning motivate them to keep staying with the use of mobile learning technologies. From this, it can be inferred that the effect of COVID-19 and the benefits or experiences students gain once they start using mobile learning have a significant impact on their present mobile learning contributing to 78.2% of their total mobile learning utilization.

The students’ mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy are found to have a considerable influence on their attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control, respectively. It can be concluded that students’ mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy have considerable influence on their current mobile learning suppose they are the sole antecedents of their attitude, subjective norm, and behavioural control. Significant innovativeness infers that students have interest and the ability to organize and take necessary actions to use mobile learning thus having a positive effect on their outlook toward actual mobile learning usage. A significant peer influence implies that colleagues of the students either possess good phones or have adequate skills and are eager to use mobile learning, which directly exerts considerable influence on the subjective norms of their mobile learning. Also, with significant self-efficacy, it can be concluded that as students are currently using mobile learning or had used it for at least one semester, they have become confident and conversant with the use of mobile learning thus contributing directly toward the behavioural control of their actual usage of mobile learning.

It is inferred that the findings of this study can be explained by certain aspects of the modified DTPB model of this research. Regarding the effect of students’ external belief factors on their attitudinal constructs, the results of hypothesis tests reveal that students’ mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and mobile learning self-efficacy significantly affect their mobile learning attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control, respectively. These results strongly support the research or modified DTPB model. On the other hand, the results of hypothesis tests show that students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control have a minimal effect on how they are using mobile learning. Although, the students’ mobile learning behavioural control has the greatest impact on their current mobile learning, followed by their attitude, and finally their subjective norm. These findings provide meek support for the modified DTPB model.

In conclusion, it can therefore be concluded that students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control do not influence their ongoing mobile usage. However, their mobile learning innovativeness, peer influence, and self-efficacy are positive and strong determinants of their current mobile usage. Also, the impact of COVID-19 and the benefits of using mobile learning are significant determinants of university students’ current mobile learning usage.

Recommendation

It calls for better strategic planning and implementation of mobile learning on a wider scale in universities focusing on students’ behavioral, social, and control factors. Support by educational institutions, tutors, and parents in the form of training and motivation can help develop a positive outlook and increase the degree of control and autonomy of students toward the use of mobile learning. The effect of university students’ mobile learning on their academic performance is an issue this study seeks to recommend for future research. This recommendation is particularly important because the current study and many other studies focused on assessing the factors that influence students’ mobile learning intentions or actual usage without delving into establishing how the use of mobile learning affects students’ performance.

Contribution

The employment of the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour enriches the existing literature as there is a dearth of its applicability in studies about mobile learning conducted in Ghana. The conceptual framework developed by this study, which is a modification of the DTPB can serve as a suitable structure for studies involving students’ ongoing or present mobile learning usage. It can help universities to design and implement mobile learning more effectively. Previous studies in Ghana about mobile learning used the variables, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in the determination of students’ mobile learning intentions. This study further assessed the determinants of these variables thus providing a broad understanding of students’ mobile learning usage. This study investigated students’ present or ongoing mobile learning usage instead of students’ intentions to use mobile learning. Studying the learners’ actual mobile learning usage has practical implications in terms of developing and implementing mobile learning usage programmes. The statistical analysis tools used in this study can be useful for tutors and students in the determination of significant activities, benefits, and challenges of their mobile learning programmes.

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors do not have any issues of potential conflict. This research involved the use of human participants. However, all issues of ethics and human research subjects were duly complied with, and the research was approved to proceed by the Ethical Committee of the Humanities, University of Ghana with ethical clearance number ECH 161/20–21. Informed consent was duly sorted and obtained from all research subjects.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our research participants for their time to participate in the study. We would especially like to express our gratitude to Professor Yaw Oheneba-Sakyi, Professor Samuel Amponsah, and Dr. Clara O. Benneh, of the Department of Adult Education and Human Resource Studies of the University of Ghana for their constructive criticism, valuable time to read through this work. We are also grateful to Professor Lucy Attom, Dean, Faculty of Social Science Education, University of Education, Winneba (UEW), and the Director of Institute of Distance Learning, UEW, Professor Francis Owusu Mensah, for their enormous support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dominic Afful

Dominic Afful holds a PhD from the Department of Adult Education and Human Resource Studies of the University of Ghana. His research interests covers remote education and mobile learning. He studied educational technology and public transportation. His focus has been on the integration of mobile learning into pedagogy and the challenges, benefits, and impacts of emerging technologies on mass education of African Youth.

John Kwame Boateng holds a PhD from Pennsylvania State University (PSU), USA. He is Associate Professor at the Department of Adult Education and Human Resource Studies. His research interests covers, remote education, learning management systems, ICT, emerging and mobile technologies integration into curriculum and pedagogical development and the role of such technologies on mass education of the African Youth. He is excited to continue to work towards supporting students’ innovativeness, peer networks, and self-efficacy, through future research and advocacy.

References

- Ajzen, I. 2019. The theory of planned behaviour: Frequently asked questions. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Al-Emran, M., Elsherif, H. M., & Shaalan, K. (2016). Investigating attitudes towards the use of mobile learning in higher education. Computers in Human Behaviour, 56, 93–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.033

- Al Hassan, K. E. I. (2015, March). Mobile learning new technique to contribute the development of distance learning courses, as views from specialists of information and instructional technology in Sudanese universities. Journal of Education and Human Development, 4(1), 269–276. URL. https://doi.org/10.15640/jehd.v4n1a24

- Al-Hujran, O., Al-Lozi, E., & Al Debei, M. M. (2014). Get ready to mobile learning”: examining factors affecting college students’ behavioural intentions to use mobile learning Saudi Arabia. Jordan Journal of Business Administration, 10(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.12816/0026186

- Altawallbeh, M., Soon, F. T., & Alshourah, S. (2015). Mediating role of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control in the relationships between their respective salient beliefs and behavioural intention to adopt e-learning among instructors in Jordanian universities. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(11). http://www.iiste.org

- Ayub, A. F. M., Zaini, S. H., Luan, W. S., Marzuki, W., & Jaafar, W. (2017). The influence of mobile self-efficacy, personal innovativeness and readiness towards studentsâ?? Attitudes towards the use of mobile apps in learning and teaching. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 7, 7. Special Issue. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i14/3673

- Azizi, S. M., & Khatony, A. (2018). BMC medical education: Investigating factors affecting on medical sciences students’ intention to adopt mobile learning. 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1831

- Buabeng-Andoh, C. (2018). Predicting students’ intention to adopt mobile learning: A combination of the theory of reasoned action and technology acceptance model. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 11(2), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-03-2017-0004

- Caldwell, M. (2014). Japanese university students’ perceptions on the use of ICT and Mobile-learning in an EFL Setting. International Journal of Computer Applications, 103(11), 188–216.

- Cheng, H. H., & Huang, S. W. (2013). Exploring antecedents and consequence of online group-buying. intention: An extended perspective on the theory of planned behaviour. International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.09.003

- Cheon, J., Sangno, L., Crooks, A., Stephen, M., & Song, J. (2012). An investigation of mobile learning Readiness in higher education based on the theory of planned behaviour. Computers & Education, 59(3), 1054–1064.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Crompton, H. (2013). A historical overview of mobile learning: Toward learner-centered Education. In Z. L. Berge & L. Y. Muilenburg (Eds.), Handbook of mobile learning (pp. 3–14). Routledge.

- Dashti, F. A., & Aldashti, A. A. (2015). EFL college students’ attitudes towards mobile learning. International Education Studies, 8(8), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n8p13

- Díez-Echavarría, L. F., Valencia, A., & Cadavid, L. (2018, March). Mobile learning on higher educational Institutions: How to encourage it? Simulation Approach, 85(204), 325–33. https://doi.org/10.15446/dyna.v85n204.63221

- Donham, J. (2010). Creating personal learning through self-assessment. Teacher Liberation, 37(3), 14–21.

- Eltaveb, H. M., & Hegazi, M. O. A. (2014). Mobile learning aspects and readiness. Retrieved September 24, from: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2019.pdf

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice Hall.

- Gangwal, N., & Bansal, V. (2016). Application of Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour for M-Commerce Adoption in India. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Rome, Italy (2), 357–367

- Gatotoh, A., Mwangi, M., Gakuu, C., & Keiyoro, P. N. (2018, November). Learner self-efficacy and mobile learning adoption among community health care trainees, Kenya. International Journal of Current Research, 9(11), 60834–60838.

- Hair, J. F., Black, B., Babin, B. J., Rolph, & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (Global Edition, 7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hockly, N. (2013). Assessment of online language education programmes’ View project. ELT Journal, 2(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs064 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280780367 Research and Applications

- Hong, J., Hwang, M., Ting, T., Tai, K., & Lee, C. (2013). The innovativeness and self-Efficacy predicts the acceptance of using ipad2 as a green behaviour by the Government’s top administrators. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(2), 313–320.

- Hsu, T., Wang, Y., & Wen, S. (2006). Using the decomposed theory of planned behaviour to analyse customer behavioural intentions towards mobile text message coupons. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 14(4), 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740191

- Hussein, Z. (2018). Subjective norm and perceived enjoyment among students in influencing the intention to use E-Learning. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET), 9(13), 852–858. Retrieved June 2 from. http://www.iaeme.com/ijciet/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=9&IType=13

- Iqbal, S., & Qureshi, I. A. (2012). Mobile learning adoption: A perspective from a developing country. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(3), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i3.1152

- Istiyowati, L. S., & Prati. (2019). Mobile Learning readiness in higher education based on the theory of behaviour. The International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE), 8(3), 8728–8735. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.C6074.098319

- Jairak, K., Praneetpolgrang, P., & Mekhabunchakij, K. (2014). An Acceptance of mobile learning for higher education students in Thailand. Retrieved January 13, 2021: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267369030_An_Acceptance_of_Mobile_Learning_for_Higher_Education_Students_in_Thailand.

- Jaradat, R. M. (2014). Students’ attitudes and perceptions towards using mobile learning for French. language learning: A case study on Princess Nora University. International journal Learning Management Systems, 2(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.12785/ijlms/020103

- Kanimozhi, S., & Sundar, S. (2017). Adoption of 4G mobile services in India: An explanation through decomposed theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 4(11), 23–27.22.

- Kankam, P. K. (2020). Mobile information behaviour of sandwich students towards mobile learning integration at the University of Ghana. Cogent Education, 7(1), 12–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1796202

- Keskin, N. O., & Metcalf, D. (2011). The current perspectives, theories, and practices of mobile learning. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10(2), 202–208.

- Korucu, A. T., & Bicer, H. (2018, June). Investigation of post-graduate students’ attitudes towards mobile learning and opinions on mobile learning. International Technology and Education Journal, 2(1), 21–34.

- Krejcie, R. B., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Kukulska-Hulme, A., Sharples, M., Milrad, M., Arnedillo-Sanchez, I., & Vavoula, G. (2011). Innovation in mobile learning: A European perspective. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 1(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.4018/jmbl.2009010102

- Mahat, J., Fauzi, A., Ayub, M., & Wonga, S. L. (2012). An assessment of students’ mobile self-efficacy, readiness and personal innovativeness towards mobile learning in higher education in Malaysia. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 64, 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.033

- National Communications Authority. (2021). Communications for Development. Quarterly Statistical Bulletin on Communications in Ghana, 5(4). Retrieved April 12, 2022 https://nca.org.gh/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2020-Q4-Statistical-Bulletin.pdf

- Ngafeeson, M. N., & Sun, J. (2015). The effects of technology innovativeness and system exposure on student acceptance of e-textbooks. Journal of Information Technology Education Research, 14. https://doi.org/10.28945/2101

- Parasuraman, A., & Colby, C. L. (2015). An updated and streamlined technology readiness index: TRI 2.0. Journal of Service Research, 18(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670514539730

- Schultze, M. (2011). The foundations of technology distance education: A review of the literature to 2001. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 59(34–44), 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2011.544981

- Serhat, K. (2022). Behaviourism, key terms, history, theorists, criticisms, and implications for teaching. Retrieved October 13, 2020:https://educationaltechnology.net/behaviourism-key-terms-history-theorists-criticisms-and-implications-for-teaching/

- Sundar, S., & Kanimozhi, S. (2018). Understanding the Intention to adopt 4G Mobile Services in\India using DTPB: A PLS-SEM approach. International Journal of Research in Advent Technology, 6(7), 1689–1695.

- Tagoe, M., & Abakah, E. (2014). Determining distance education students’ readiness for mobile learning at university of Ghana using the theory of planned behaviour. The International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 10(1), 91–106.

- Tao, C., & Fan, C. (2017). A modified decomposed theory of planned behaviour model to analyze user intention towards distance-based electronic toll collection services. Promet – Traffic &transportation, 29(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.7307/ptt.v29i1.2076

- Wong, K., Wang, F. L., Kwan, K. N., & Kwan, R. (2015). Investigating acceptance towards mobile learning in higher education students. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 494, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-46158-72

- Yorganci, S. (2017). Investigating students’ self-efficacy and attitudes towards the use of mobile learning. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(6), 181–185.