Abstract

Health literacy is a major determinant of health across space. At different scales, optimal interplay between individual and organizational efforts is required to ensure a health literate population. This is essential because social and environmental determinants of health influence both the individual and populations across the life course. Despite this knowledge, little is known about faith-based organizations’ health literacy assets and gaps. Drawing on the community health literacy assessment framework, health literacy assets and gaps are assessed among 50 faith-based organizations in Accra, Ghana. Specifically, the study assessed (1) how the organizations defined health literacy, (2) the strategies used in identifying health literacy concerns in their organizations, (3) health literacy assets, and (4) health literacy gaps. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants from the organizations. Thematic and summative content analyses were used to appraise, interpret, and quantify the data from the interviews. Results show that while the organizations have varying definitions of health literacy, the most cited meaning of health literacy was right health information. Of the strategies used in identifying health literacy concerns, the most cited strategy was members’ medical status. While the most declared health literacy asset was the health experts of the organizations, the health literacy gap most spoken of was lack or inadequate health information, education, and communication (IEC) materials. An assessment of health literacy of faith-based organizations through a modified framework has illuminated our understanding of health literacy status of organizations and how these organizations may respond to members’ health needs.

1. Introduction

Health literacy is a major social determinant of health across space (Amoah, Citation2018; Sørensen et al., Citation2021). At different scales, optimal interplay between individual and organizational efforts is required to ensure a health literate population. This is essential because social and environmental determinants of health influence both the individual and populations across the life course (Sørensen et al., Citation2012). Therefore, health literacy as a broad concept is concerned with political, social, and environmental factors that influence health as well as a variety of skills and competencies needed in the acquisition, understanding, critical analyses, and application of health information (Gele et al., Citation2016). Such skills and competencies, which are required to make informed decisions about different health domains—health promotion, health-care setting, and disease prevention (Santos et al., Citation2017) – and ultimately enhance quality of life (Squiers et al., Citation2012), are influenced by environmental factors (including cultural beliefs) (Baumeister et al., Citation2021). Given this recognition, it is essential to study domains of environmental and social factors that impact health literacy.

Pursuant to the need for assessing community health literacy, a number of tools and guides were developed. These guides are used by organizations to examine their health literacy practices and organization’s attempt to change their care delivery and service provisions to ease people’s navigation, comprehension, as well as information and services use regarding their health (Farmanova et al., Citation2018). These tools measure several dimensions of a health literate organization including access, navigation, communication, workforce, meeting needs of a population, leadership, and management, and consumer involvement (Farmanova et al., Citation2018). Whereas communication refers to the inclusion of verbal and written communication in activities of the organization through the adoption of communication methods, such as plain language usage and teach-back strategies, access, and navigation denote the services being provided as well as the nature of the organization’s physical environment (Brega et al., Citation2015; Jacobson et al., Citation2007; Thomacos & Zazryn, Citation2013). This dimension is concerned with the conscious effort to integrate health literacy into an organization’s mission and consumer involvement refers to assessment of health literacy policy through feedback from clients and follow-up methods (Thomacos & Zazryn, Citation2013). Elements like help with translation and improvement in self-care management constitute meeting the needs of the population, whereas the provision of health literacy professional development and training for staff constitutes the workforce dimension.

Irrespective of the availability of these tools and their amenability for use in planning and health literacy action, as well as focusing on the goals of clear quality improvement strategies, several of them have not been tested for applicability within the practice of organizations; therefore, their effectiveness is called into question (Farmanova et al., Citation2018). Meanwhile, at the community scale, there are inadequate health literacy intervention tools for community health assessment (Platter et al., Citation2019). More so, after a systematic literature search by both the principal and co-principal investigators of this project that included health education and health literacy handbooks, literature, or manuals, we did not find any health literacy guides for religious organizations in Accra, Ghana. The searches were conducted across both “non-scientific” (e.g., Google/Microsoft Edge) and “scientific” databases like Web of Science, Medline, EMBASE (via Ovid), Scopus, Google Scholar, ProQuest Central, and International Bibliography of the Social Sciences.

Faith-based organizations play a critical role in health promotion in Ghana (de Graft Aikins et al., Citation2010). In this deeply religious society where most Ghanaians are affiliated with a religious institution, their trust and accessibility to religious leaders and institutions shape the information to which they have access. This is coupled with the fact that faith-based organizations play a central role in Ghanaian civil society (Kuperus, Citation2018), often filling the position of government agencies and NGOs in communities where public health programs are ineffective or have yet to reach. Unlike Western contexts wherein non-governmental health organizations are the primary vehicles for mobilizing and engaging health information, in Ghana, the most active and prevalent organizations in civil society are faith-based organizations. The multifaith and multidenominational organizations present across Ghana are central to providing community, sense of identity, and belonging, and are often the main source of social and political capital (Mammana-Lupo et al., Citation2014) and are perceived as the medium from which most citizens may receive health information.

In many cases, faith leaders and healers are recognized and “serve as the first port of call for disease curing and prevention” (Peprah et al., Citation2018, p. 1), which best positions their organizations to frame the messaging from public health institutions so congregants can engage, understand, and internalize health information. Consequently, the religious health assets provided by faith-based organizations and their spiritual leaders are often the only sources of trusted information for Ghanaians (Cochrane et al., Citation2014). Thus, the way these local faith-based organizations and their leadership understand, engage, and spread health information is central to understanding health literacy in the Ghanaian context. However, it is important to note that many faith-based organizations are not trained to disseminate accurate public health information. They often rely on alternative medicines, treatments, and spiritual healing practices that may not accurately address the health problems in their community. This was compounded during the COVID-19 crisis, which revealed the strengths and uncertainties associated with faith-based organizations in promoting health information. Many religious institutions canceled in-person services while providing their congregants with correct health information, relief items, a bottom-up approach to tackling the outbreak, and offering communal services that impact the indirect effects of COVID-19 (Barmania & Reiss, Citation2020). However, the uncertainty surrounding the length of the outbreak and differing religious orientations towards the efficacy and source of the virus also impacted its spread through illegal religious assemblies, misinformation, and the promotion of alternative non-scientific treatments. Thus, the way these local faith-based organizations and their leadership understand, engage, and spread health information is central to understanding health literacy in the Ghanaian context.

Therefore, this study draws on and applies the relatively new community health literacy assessment framework (CHLA) to the Ghanaian context to examine (1) how the faith-based organization’s defined health literacy, (2) the strategies used in identifying health literacy concerns in their organizations, (3) health literacy assets, and (4) health literacy gaps.

2. Organizational health literacy theories and the community health literacy assessment framework

The multifaceted nature of health literacy in practice rears its head in its conceptualization as well. Organizational health literacy theoretical dimensions span ecological perspectives, theory of justice, and participatory health care health-care responsiveness. The ecological perspective recognizes that environmental and socio-cultural factors interact to determine organizations’, and by extension individuals, susceptibility to health stressors in different health domains that require interventions. It recognizes inadequate health literacy as a major susceptibility with adverse interactive effects on other socio-ecological vulnerabilities (Farmanova et al., Citation2018). The theory of justice on health literacy perspectives, on the other hand, emphasis equity and equal rights applications in the delivery of health care and provision of health services through a deliberate reorientation of health-care standards to meet the needs of customers with limited literacy (Coughlan et al., Citation2013). This requires, among other things, an integration of health literacy and cultural competence. This integration has been argued to be necessary since focusing only on health literacy or cultural competence alone is inadequate and insufficient to improve health-care service delivery and communication (Andrulis & Brach, Citation2007). A participatory healthcare perspective place patients at the center of healthcare provision through patient engagement (Hood & Auffray, Citation2013). Proponents of this perspective assert that irrespective of the complexities inherent in conceptualizing participation in terms of who is included, patients must be included since they are the focus of care. Health literacy is placed in the broader context of this perspective and argued to increase through an optimal interplay of health-care infrastructure schemes and social strategies to effectively engage patients throughout the patient care journey (Hood & Auffray, Citation2013). This kind of engagement, which includes a proposed health care wellness coach—an example of social strategies—will ensure that correct information is handed to patients, thereby increasing health literacy engagement and by extension improving health literacy.

While the aforementioned theories are primarily health-care setting specific, health literacy has been argued to have broader applications beyond the healthcare environment. To this end, the Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness (OHLR) framework was developed to provide a structure for which health professionals and organizations can be used to be responsive to the needs of the diverse populations they serve as they attempt to provide equitable service access (Dietscher & Pelikan, Citation2017). The central idea is responsiveness of the organization to the needs and preferences of clients. Therefore, although elements of participation, equity, and health-care infrastructure are included in this framework, the central goal of this framework allows organizations to be responsive and proactive in specific socio-cultural and health-care contexts (Trezona et al., Citation2017). Apart from the specific socio-cultural contexts, pandemic periods are characterized by, and present, grave uncertainty, complexity, and call for action. These characteristics determine the situational circumstances under which individual decision-making occurs (Abel & McQueen, Citation2021). This underscores the argument for individual and collective responsibility in critical health literacy theory and discourse; especially, since individuals’ willingness to assert control over health decision-making has the potential of impacting collective health outcomes (Chinn & McCarthy, Citation2013). When consideration is given to individual and collective agencies, irrespective of political regulations, individuals are not passive actors, but they are active players whose behaviors can alter structural conditions and impact the collective (Abel & McQueen, Citation2021).

These theories, therefore, calls for the proposal of operational frameworks to elicit relevant information that will support action on health literacy. One of such contemporary framework is CHLA. The framework grants organizations across scale (community level to state level) a structure to acquire information and evidence of health literacy assets, gaps, and opportunities (Platter et al., Citation2019). The purposes of the information gathered using the CHLA include (1) revealing to organization areas where they have their focus and where they can improve their health literacy practices, (2) inspire future research, and (3) apprise strategic planning across scales.

The CHLA acknowledges that there are several questions with the potential of eliciting community health assessment information, but the basic goal of an assessment should involve collection and analyses of data on community health indicators with the aim of establishing baselines, recognizing health main concerns, and taking informed future actions (Platter et al., Citation2019). Established baselines include what health literacy means to organizations given the varying definitions of health literacy (Sørensen et al., Citation2012) and low levels of health literacy across space with adverse effects on health outcomes (Berkman et al., Citation2011). How organizations define and interpret health literacy has ramifications for policy-oriented health initiatives and healthcare delivery (Malloy-Weir et al., Citation2016). Given the assertion that health literacy means different things to different people (Baker, Citation2006), and the lack of a singular accepted definition of health literacy (Sørensen et al., Citation2012), the meanings associated with the concept are gleaned in domains, such as racial health disparities (Hebert et al., Citation2008), decision-making processes (Charles et al., Citation1997), and health promotions (Bakker et al., Citation2019). Malloy-Weir et al. (Citation2016) found remarkable similarities in the most cited definitions to include individual’s competencies and actions. While competencies such as ability to obtain and comprehend were mostly applied to health information, health services, and health concepts, actions were linked to making appropriate health decisions, promoting good health, functioning in a health-care setting, reducing health risks, and making informed choices (Malloy-Weir et al., Citation2016).

Inherent in most definitions is the ability of health information to enable health promotion, reduction in health risks, and making sound health decisions for the life course of people. Critical health literacy and its components illustrate this assertion across scale, as indicated by Abel et al. (Citation2022), while critical health literacy is beneficial to the individual, cognizant of the socio-political elements of the concept, it also involves empowering communities, as well as reducing population health inequality. To allow for individual and collective agency consideration given a socio-political context, Abel et al. (Citation2022) assert two key constituents—reflection and action—in the context of health promotion and public health. Therefore, they define critical health literacy as “the ability to reflect upon health determining factors and processes and to apply the results of the reflection into individual or collective actions for health in any given context” (Abel et al., Citation2022, p. 2); a further push in the frontier of critical health literacy definition to include elements like individual and collective empowerment, political action, and participation (Abel & McQueen, Citation2021).

When the process of assessment adopts the tenets of inclusivity by engaging a wide array of stakeholders with varying perspectives, the output can enhance organizational and community cooperation, strengthen partnerships across scales and provide concrete benchmarks for improvements in health practices (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2015). The tenet of inclusivity would ensure that community members are involved as full participants at every step in the process of assessments such as planning, implementation, and reporting (Platter et al., Citation2019).

Platter et al. (Citation2019) argue that from a health literacy perspective, an assessment of a community’s health should focus on health information, communication, and education gaps, assets, and opportunities in order to integrate health literacy strategies and approaches to improve the health literacy of said community and by extension the individuals and population. Consequently, to examine and characterize community health literacy, the authors adapted the community health needs assessment framework and its processes and tools (Association for Community Health Improvement, Citation2017) to create the CHLA model with a focus on ascertaining health literacy assets, activities, gaps, and opportunities.

In the scholarly literature over the last couple of decades, health literacy has been conceptualized from a public health perspective as an asset to be built through health education and communication with the purpose of enhancing health decision-making (Nutbeam, Citation2008). That is, health education programs have the potential of enabling people to develop skills needed to take action across varying sectors—including social and environment, thereby making health literacy an outcome of health communication programs. Platter et al. (Citation2019, Citation2022), on the other hand, conceptualized health literacy assets as resources and services needed to address health literacy as well as activities undertaken to tackle health literacy. Similarly, and conversely, the idea of health literacy gaps transcends the known informational gap at the individual level (Ladin et al., Citation2018) to include the absence of elements obstructing health literacy work (Platter et al., Citation2022). The gap explained in the latter has implications for practice and interventions. As Barry et al. (Citation2013, p. 1509) put it: “how best to address the needs of population groups with low health literacy”.

Furthermore, these needs necessitate a localized lens to understand how Ghanaians engage and employ health information. Conducting research on health literacy in Ghana allows us to understand how the variability of the milieu can shape how communities comprehend and engage health issues while also producing context-based interventions that can decrease critical gaps and improve their lived experiences. This is coupled with the fact that empirical research on African and in specific Ghanaian health literacy is in its infancy as there is no national or regional assessment of health literacy in the country. The minimal research that has been conducted has only assessed health literacy in relation to antenatal health literacy (Lori et al., Citation2014), health outcomes and social capital (Tutu et al., Citation2019), universal health coverage (Amoah, Citation2018), street children (Amoah et al., Citation2017), behavioral risk factors and gender (Amoah & David, Citation2020), and undergraduate students (Evans et al., Citation2019). There has been no large-scale study that has assessed health literacy from an organizational level or through the application of existing health literacy theoretical and applied frameworks.

The paucity of studies in Ghana that apply these theories justifies enquiry into the role of religious organizations in health information dissemination. Religious organizations are a major form of embodied cultural capital, and cultural capital enables individuals to thrive in the face of power and privilege thereby, theoretically, addressing health inequalities (Abel, Citation2008). Cognizant of the importance of cultural capital for health literacy embodied cultural capital—through religious organizations—may act as conduits for the transmission of skills and acquisition of behaviors (Abel et al., Citation2022) that are essential for health promotion. Knowing that religious organizations are made up of individuals who are also embedded in social structures, their interconnectedness and relations across space is essential for understanding mechanisms by which high health literacy goals may be achieved. Abel et al. (Citation2022) identifies two interrelated functions of critical health literacy, theoretically, in the context of cultural capital. Firstly, as an integral part of cultural capital, critical health literacy may act as a conduit in terms of resources for individuals in their quest for better life. Second, given hierarchical relationships that exist across the space in which social inequalities are embedded, the probability of critical health literacy acquisition and use may function as a medium of collective inequality.

Thus, the present study adapts the CHLA to examine how religious organizations in Accra, Ghana, define health literacy, the strategies used in identifying health literacy concerns in their organizations, the health literacy assets, as well as health literacy gaps. Health literacy assets refer to factors that do or could support health literacy work or progress, while health literacy gaps were defined as missing factors inhibiting work or progress (Platter et al., Citation2019).

3. Methods

3.1. Process and instrument

The steps for the CHLA (see Figure ) were adapted and modified for the context of this study. First, the team of researchers includes the authors of this paper, CITADEL Research Network for Development in Accra, Ghana, and 10 undergraduate research assistants who worked on this aspect of the project from August 2021 to February 2022. The community whose literacy is being assessed was defined based on geographic location and the populations being served. Specifically, the community is a faith-based organization in Accra, Ghana. The team formed a partnership with the umbrella organizations of these faith-based groups. Specifically, the partnership included the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council, the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, the Seventh-Day Adventist Church Conference, and Islamic groups. The research team leadership met with the partners to determine churches and mosques within the research area. The faith-based organizations were purposely selected across the length and breadth of Accra.

Figure 1. Steps of the Community Health Literacy Assessment Framework (Platter et al., Citation2019).

A semi-structured interview questionnaire (adapted and modified Platter et al., Citation2019) was adapted and piloted both informally (among researchers) and formally—among a selected number of participants from churches and mosques in Accra. The initial questions during the pilot were scrutinized for context, clarity, meaningfulness, comprehension, and understandability, as well as flow. Feedback from the pilot was assessed, and the required adjustments were made for the final instrument. The final interview questionnaire had two main parts. The first part elicited information on the organizations’ and participants’ background information such as length of existence or operation, length of time in leadership, the level of operation of the organization (e.g., congregation, district, regional, and national), and the number of members. The second part gathered information on health literacy. Participants were asked, among other things, what health literacy meant to their organizations, the approaches or methods they use to identify health literacy concerns in their organizations, the factors that do or could support health literacy work or progress, and missing factors inhibiting health literacy work or progress in the organizations. Based on the suggestion of Platter et al. (Citation2019) not to provide respondents with a definition of health literacy due to the uncertainty of the concept, no formal definition of the concept was provided prior to asking them how their organizations define health literacy.

3.2. Participants and interviews conducted

The participants were recruited through the leadership of Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council, the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, the Seventh-Day Adventist Church Conference, and Islamic organizations. Since most of these organizations are at the national level, the research team was guided and introduced to their regional and district leadership for participant recruitment. The participants were leaders or designees of the participating faith-based organizations who have in-depth knowledge of the operation of the organization. Potential research participants were contacted through telephone calls and in-person visits to the offices and premises of the organizations selected.

In accordance with research protocol and ethics requirements, IRB approval was obtained, and informed consent was sought with each participant. The interviews were completed in-person, and they ranged from 46 min to 1:15 min. Each interview was recorded and transcribed and that was analyzed together with field notes.

3.3. Data analyses

Qualitative thematic and content analyses were employed using NVIVO version 12. The study adapted Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005, p. 1278) definition of qualitative content analysis: “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns.” The data analyses constituted identifying themes as well as summative content enquiry techniques. Transcribed data texts were read for emerging themes within the context of the study research questions. Reading and re-reading of transcripts uncovered categories and associated concepts on health literacy aspects being assessed.

Regarding summative content analysis, the study began with electronic searches for word frequency of identified words or phrases in the semi-structured interview text with the purpose of comprehending the circumstantial use of those words or phrases. This approach transcends the simple word frequency to involve the process of interpreting the content of the data, an approach known as latent content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Therefore, in addition to counting identified words and phrases in the textual data to identify patterns (Morgan, Citation1993), the analyses focused on uncovering fundamental meanings and interpretations associated with the use of those words and phrases.

The authors individually employed the techniques discussed to analyze the data and reassembled them as a team to compare notes to create codes for health literacy definitions, strategies to identify health literacy concerns, health literacy assets, and gaps. Codes were subsequently quantified by the number of participants who mentioned a word or phrase in an interview that corresponded with the code (Platter et al., Citation2022). Although analyses began after all the interviews were completed, the codes were revised and modified for fitting. The strategy used by the authors to independently code and reassemble ensured consistency due to their ability to compare codes. Subsequently, member checking was undertaken to enhance reliability. Member checking examined research participants’ agreement with the researcher’s finding and interpretation of the data. Specifically, regarding the process to review the interpreted data with participants to assess accuracy of findings, one-on-one visit with respondents on the individual participant’s data and associated findings approach was used. This approach enabled verification, confirmation, as well as modification of interview transcripts.

4. Findings

4.1. Participants background characteristics

In total, there were 50 faith-based organizations interviewed, constituting 43 church-based and seven Islamic-based organizations in a four-month period in Accra (Table ). Thirty-four interviews were conducted with congregational/branch-level organizations, 14 at the district/headquarters level, and one each at the regional and national level, respectively. On average, these faith-based organizations have been in existence for 22 years with an average organizational membership of 495. Of the 50 interviews, 39 of the participants were the organization’s leaders, whereas 11 were representatives.

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants

4.2. Organizations’ definition of health literacy

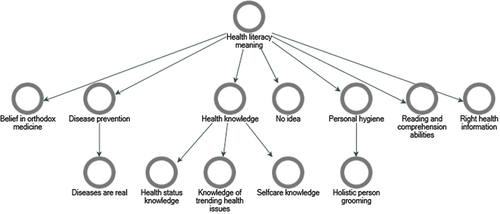

The definitions provided by the organizations’ leaders were varied and wide-ranging in themes. There were six themes that emerged. These were beliefs in orthodox medicine, disease prevention, health knowledge, personal hygiene, right health information, and reading and comprehension abilities, although a couple of the respondents reported that they did not know what health literacy meant (Figure ).

Regarding belief in orthodox medicine, participants indicated that to their organization, seeking help at orthodox medical facilities, consulting trained medical personnel at those facilities and using prescribed orthodox medication is what health literacy means to them. The following quotes illustrate two church leaders’ explanation of the importance of orthodox medicine, while not over focusing on the spiritual lives of congregation:

As a church, we make our congregants to understand that, though there is a spiritual angle to everything, one cannot rule out the physical aspect of it. So, in case of any issue, solve it from the physical angle first. After consistent treatment from the physical perspective and that issue is not getting better, here is also a prayer camp [Organization 042].

… we advise you to see a good doctor to administer good medication to you so that you can be healed. We are much more concern about their health so if prayer doesn’t help then we direct them to qualified physician to be treated [Organization 005].

As discussed in the above quotes, in the Ghanaian context, spiritual counseling and treatment may be the first or last resort for addressing health issues. This may be for a variety of ailments and further illustrate the intertwining of the physical and metaphysical localized approaches towards congregants’ wellbeing.

On the emergent theme of disease prevention, church leaders defined health literacy as preventive measures that ought to be taught to church members so that they will not fall ill and have the capacity to exhibit disease prevention competencies. A sub-theme that was coded as “diseases are real” spoke to the emphasis by the organizations that diseases exist within the physical domain of humanity rather than disease solely having a spiritual dimension according to their beliefs. On disease prevention, a couple of participants said

We have a saying prevention is better than cure. Why don’t you educate the people on what they are supposed to do before you get sick, so health literacy I think is better that visiting the hospital because if you educate the people to know what they are supposed to know, what they are supposed to do so they don’t get sick, they won’t go to the hospital [Organization 026].

[we] give [everyone] tips on health and how to prevent [diseases]. So, we teach them how to protect their body [Organization 005].

The following quote illustrates the sub-code “diseases are real”:

It is my responsibility as the head pastor to make that person understand that this sickness or disease is real [Organization 003].

Concerning health knowledge, organizations’ defined health literacy as the provision of basic health information to congregants in terms of trending health issues, for knowledge of health concerns, and being abreast with health issues among others. Health knowledge had three subthemes: health status knowledge, knowledge of trending health issues, and self care knowledge. The three quotes below illustrate each of the three subthemes, respectively.

So basically it is just about how to manage your health, how to be a constant visitor of the hospital, to always go for a check up to see how your health status is, so basically this is what I can say [Organization 036]

The health literacy, for example, I have got a file and l used these paper articles and the rest, whenever there is something relevant to health, I bring it to the church and we read it to the whole congregation [Organization 020]

is to be aware of how one can take care of themselves and by extension their families [Organization 036]

A few participants defined health literacy as personal hygiene. Participants expressed informing congregants about the essence of personal hygiene practices and its connections to the service of God, a healthy family, a good physical environment, and the development of a holistic individual (a subtheme). The next quote illustrates the personal hygiene theme and the succeeding one shows the subtheme:

Health literacy to my own understanding and how to benefit nature is like letting members know how they should be able to handle themselves very well in terms of personal hygiene [Organization 002].

It means that as we are serving the people to grow in the things of God we must also grow in our body as l told you it so holistic: soul, body and spirit, we are meeting all the three they have to be health so that they can worship God [Organization 033].

Reading and comprehension abilities as definition of health literacy was explained as the ability of the congregation to read health issues and understand health matters. A participant remarked:

What it means is that we want a membership to read more on their health and then also we want them to know more about their health [Organization 031]

The provision of the correct or right health information to congregants was a major theme. While educating members about health was mentioned, as has been discussed, several participants emphasized right information dissemination as to what health literacy meant to them. A couple of responses from church leader below illustrate this theme:

Health literacy in the opinion of the church is an empowerment, very strong empowerment for church members to know opportunities and threats and challenges confronting them so that they will know what choices are health compromising and what choices will be health empowering so that at any time they will know what is helpful and what is not helpful so we consider health education to be an empowerment to the congregation [Organization 037].

… so, when we talk about health literacy is something like you have to know what to do. If you illiterate on your health it means you are not going to take good care of your health, what to eat and those kind of things and you will not even consider those things but if you have those staffs like you help people to know what to eat, what to do like exercising the body, taking this amount of water daily and those kind of things and you let them be conscious about their own health and what to do and that one they will become literacy on their health [Organization 019].

4.3. Strategies used in identifying health literacy concerns

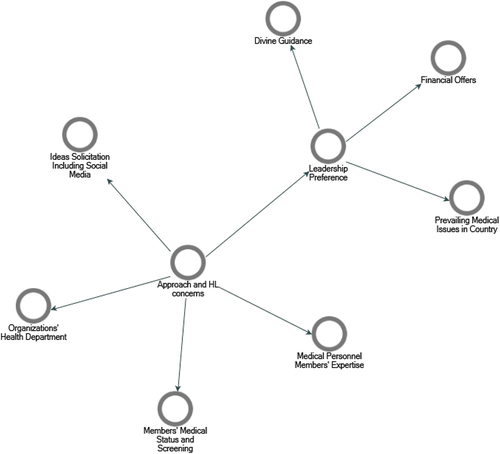

Participants were asked about how and what approaches they employ in ascertaining health literacy concerns as per their own definition of health literacy. Five main themes emerged (Figure ): ideas solicitation, leadership preference (subthemes—divine guidance, financial offers, prevailing medical issues in the country), medical personnel members’ expertise, members’ medical status, and organizations’ health department.

As for ideas solicitation, some organizations make conscious efforts to seek the input of members. These efforts include the organizations’ departments meetings, use of social media platforms, such as WhatsApp (which is a popular social media application in Ghana), during house visitations, open forums, and organization’s notebooks for suggestions. The following quotes illustrate the themes:

What we normally do is that we ask the groups to identify issues of concern to the group. We don’t impose things [on] them. We allow them to find out the issues that are of concern to them and when they bring them up, we see what we are able to do about it [Organization 016].

… most of them … because the church has a platform a social media platform and was all the information, we put up put them on a platform okay and those who are using the mobile phones which have WhatsApp and all that gets information on the platform [Organization 002]

The leaders’ or leadership preference influenced or determined how health literacy concerns were identified. Some participants mentioned that leadership preferences and decisions occur through divine inspiration and guidance, financial offers and commitment to members in need of health services, as well as the prevailing topical medical issues in the country. Regarding divine guidance, a participant remarked:

Apart from using the home knowledge or education that we had from our parents, at least the Holy Spirit guides me in some of these things. I am not a medical doctor but I can look at somebody’s health condition and diagnose [Organization 004].

Financial offers and in-kind offers during periods of health stressors being experienced by members influences leaders’ decisions and preferences for health literacy concerns. Such occurrences are sometimes the opportunity leaders have in knowing about a particular health problem. To this effect, a leader indicated:

Financially, we help them so that they can go to the hospital for treatment. In one of my assemblies or let’s say just Sunday we had to organize blood donation for somebody who needed surgery and they needed blood. we did it for that person. And we are still going to do it. This year when it comes to blood donation it’s part of our projection that we are going to organize blood donation to the hospitals around us [Organization 011].

Some leaders opined that the prevailing health stressors in the country at any given time are an indication of health literacy concerns for their members. For example, a respondent said:

There is also internal discussion, whenever we are discussing some issues, certain issues will come out and then some like what is happening at the regional level [and] that is the Ghanaian [national] level at large. So whatever happens at the Ghanaians level also affect us since we are also part of Ghana so we have to do something about it [Organization 020].

Medical personnel members’ expertise was tapped to aid in identifying health literacy concerns. Some respondents acknowledged their limited knowledge of certain medical conditions; therefore, the reliance on the medical professional among their congregants to identify health literacy concerns. This subtheme is illustrated by the statement below:

The doctor among us, he educates. Because he is part of the health system, he knows what is for the system so he will suggest whatever we are supposed to do. So we go by his counsel [Organization 041].

Knowledge of members’ medical status by leaders seem to be a health literacy concern wake-up call for organizational leadership. This was the most cited way by which the organizations determine health literacy concerns. Information about the medical status of members were either volunteered by members or ascertained during medical screening exercises arranged by the organizations. Medical statuses of members are volunteered during organizational meetings, and visits to ill members. Others identified health literacy concerns through the disease incidence in the communities in which the organizations are located. The remark below illustrates this theme:

First we use observations, that is community observation and household observations. When a church member becomes irregular in church and we visit them in their home and you will hear that this disease has put him or her down so when we get a case we this that it’s becoming a case. So for the community observations, when we see that a number of these diseases is rampant in the community, we do run health programs on it [Organization 020].

Concerning organizations’ health departments, some of the organizations have health departments (auxiliaries) whose members advise leadership about health concerns among the congregation. Some of the respondents indicated that their health departments are invaluable both in the area of health literacy concern identification and health programming determination. A leader remarked:

Our health team, they are on the ground. So, when they identify any challenge, or anything that they think we must bring to the notice of the whole church, they do that. And because of my constant interactions with parishners, I get to hear a lot. I get a lot more information on the health status of parishners and so I also consult them to see how best we can address some of these concerns [Organization 040].

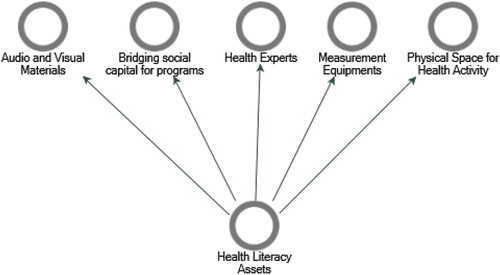

4.4. Health literacy assets

With respect to factors that do or could support health literacy work or progress in the organization, there were five emergent themes. These were availability of audio-visual materials, the presence of bridging social capital, health experts’ accessibility, availability to measurement medical devices, and obtainability of physical space (Figure ). Some respondents noted that the availability of audio-visual materials for members supported their health literacy work. Such materials included televisions, projectors, and flip charts for drawing. A respondent remarked that:

Yes, we have a TV station. We have series of health programs on it. We have consulting, we have the healthy living program. They run every Wednesday and Thursday every week they run that benefits church members. It is aired on Go TV [Organization 025].

Regarding bridging social capital for health programs, some respondents acknowledged reliance on sister organization for the health expertise of their members, organization of health programs, and subsidizing health programs. The statement below illustrates this theme:

… in our area where we have our big branch at Lebanon, they have more of the experts over there. The nurses or the medical practitioners over there and these are already church members, so we invited them, and they don’t take anything, it’s for free, we only give them something for transport [Organization 021].

Congregations with varying forms of health experts as members deem them vital assets and human resources in the promotion of health literacy work in the organizations. Their expertise ranges from pharmacies, dieticians, physiotherapists, community health personnel to nurses, counsellors, and medical doctors. The health experts are given the opportunity by the leaders to share health information with congregants, share health knowledge with community members for outreach purposes, establish health programming for the organization, run counselling sessions, and organize health programs. One leader said:

We have what we call the team of health personnel and they are not supposed to only minister to the church. But even to their colleagues outside the church. For example, we have a team of doctors, and their aim is not only to help or assist educate members of the church but to educate their own colleagues and win them to Christ [Organization 011].

Concerning measurement equipment, some leaders deemed having at their disposal medical devices as enabling their health literacy efforts. The availability of first aid box items, blood sugar machine kits and monitors, and blood pressure monitors and cuffs were deemed as factors that do support their health literacy efforts.

Physical space for health activities was identified as a health literacy asset. These included designated rooms in the church compound and a donated community information center. These places are used periodically for both the organization’s primary mandates and health programs. An organization leader indicated that:

As I clearly mentioned, this very building that’s the children ministry, we have dedicated that place to the community where once in every week they come there and serve the community and it’s used as a weighing center where children below 5 years are weighed, and parents are also educated as well [Organization 006].

4.5. Health literacy gaps

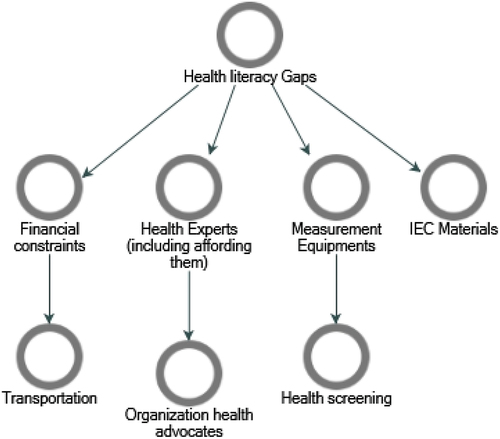

Concerning missing factors inhibiting health literacy work or progress in the organizations, four main themes emerged. These were lack of or inadequate health Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) materials (most cited); inadequate measurement equipment (medical devices); insufficient or lack of health experts (subtheme: lack of health advocates); and financial constraints (Figure ).

Concerning the inadequacy of IEC materials available to the organizations, respondents explained that items such as health videos, picture illustrations of illnesses, projectors for screening videos, reading documents translated into local languages, and interpreter services during health programs are responsible for retrogressing their health literacy work. Participants mentioned the impact of lack of IEC materials in diverse areas of health education/promotion including disease prevention. The statement below from a respondent encapsulates a perception of the importance of IEC materials:

Having a calendar that shows or displays those information would be helpful. For instance, a calendar depicting a child who has been fed on one food and has become stunted or ill is also educative. Again, a calendar showing someone who ate in an unclean environment and ended up vomiting all the he ate is also good. These teaching and learning materials will help members to understand and grasp the concepts easily [Organization 045].

With regard to inadequate measurement equipment (medical devices), participants expressed that they impact the desired health program that borders on health literacy. The devices mentioned include blood pressure monitors, blood sugar monitors, test kits, first aid boxes, kidney test kits, and malaria test kits. This equipment, according to the respondents, will help their health literacy efforts through limiting the number of members’ visits to the hospital and pharmacy, have in-house equipment that is readily available, minimize the tendency to borrow, as well as aiding in health screening exercises by some of the organizations. The quote below illustrates health literacy gap according to a respondent:

There should be a provision for at least this BP [blood pressure] apparatus and then blood sugar testing machine and then add the antigens and then test kits and that is what you’re trying to get into the church so that we can do a rapid test in case someone comes to the church and we realize the person is ill we can do some rapid test and then those people are there to get some medication if necessary because we have doctors and pharmacists around [Organization 031].

Insufficient or lack of health experts in some of the congregations is perceived as stumbling blocks for health literacy efforts. These congregations indicated that having health experts allows for authenticity and good reception of messages, use them as a means of outreach to nearby communities, and ensure constant availability of experts. Additionally, a few respondents mentioned that apart from health experts, they will need trained health volunteers to augment the work of the health experts in the organizations. The quotes below illustrate the lack of health experts and lack of health advocate subtheme, respectively.

If someone may give us health education, it would not be like the health experts who have received formal training in that. For us, we will look at health from the angle of our work as pastors. Adding that of the health professionals brings positive changes to the lives of our members [Organization 042].

Although we have Health personnel, we need voluntary people that can be trained so that they would support and add up to what the health personnel are doing [Organization 028]

Finally, financial constraints were discussed as inhibiting health literacy work or progress on some of the organizations. Financial constraints, exemplified by inadequate money, limited their health literacy efforts through constraining: the acquisition of space for health programming, paying honoraria for invited health personnel, and means of transport to visit sick members. A respondent discusses financial constraints by stating that:

[The] Bible said money answereth all things. When we have enough money, next year you will come and see surprising things. I have a lot of vision and things I have by my calling brought to the church it’s not easy. So, if I have money, I will do a lot [Organization 004]

5. Discussion

The study sought to examine (1) how organization’s defined health literacy, (2) the strategies used in identifying health literacy concerns in their organizations, (3) health literacy assets, and (4) health literacy gaps. In this section, the paper will discuss the major findings.

The results show that there were varying definitions of health literacy among the religious organizations in Accra, Ghana. Following Platter et al. (Citation2019) findings of uncertainty about the boundaries of health literacy and pursuant to their recommendations not to provide a definition for participants, the design of the study removed potential limitations from respondents. This finding is expected since definitions vary even among researchers and community of practice (Sørensen et al., Citation2012 and it confirms Baker’s (Citation2006) assertion that health literacy means dissimilar things to different audiences. While the definitions provided by the respondents are narrow and limited in scope, essential elements of health literacy are read from most of the findings. The most cited response to the question of definition, which was the provision of right health information to congregants, was linked to members’ ability to make good decisions and develop requisite competences. Like what Malloy-Weir et al. (Citation2016) found in the scientific literature, the ability to access health information and understand it was associated with actions such as good health decision-making and health risk reductions in everyday life. These findings further buttress Santos et al. (Citation2017) assertion on the link between health literacy and preventive medicine—that possession of adequate information supports uninhibited and clear-cut decision-making. The right health information can promote health knowledge relevant for different health domains including disease prevention (Sørensen et al., Citation2012). While the acquisition of right health information is important for health promotion, it is equally critical to consider the context in which religious organizations operate as well as the temporal dynamics. Clearly, from the findings, the essence of cultural capital for health literacy, which is exhibited in embodied cultural capital—through religious organizations—seem to be acting as channels for the transmission of health skills and acquisition of behaviors (Abel et al., Citation2022) that are vital for health promotion. It is worth mentioning that organizations that had no previous knowledge about health literacy had no definition. Therefore, apart from the multiple meanings, it is essential to develop health literacy capacity without assuming that all organizations have at least a basic understanding of the concept.

Most of the organizations have devised ways to identify health literacy concerns. These ways include direct idea solicitation from congregants, leadership preference, drawing on the expertise of members working in the medical field, members’ medical status and relying on the counsel of organizations’ health department. The strategies and approaches being used by the organizations are signs of responsiveness to the needs of the different populations they serve, which is quintessential of the Organization Health Literacy Responsiveness framework elements (Trezona et al., Citation2017). With the fundamental idea of the framework being responsiveness to the needs and preferences of clients, the religious organizations that respond to the needs of the members based on their medical status and soliciting ideas demonstrate responsiveness to the health preferences and needs of members (Trezona et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, the organizations that consult members in the medical profession as well as establish health departments in the church illustrate the proactive elements in their social context to which Trezona et al. (Citation2017) refers in the OHLR framework. While it may be argued that leaving health literacy concern identification to the preference of leadership may be sticky due to the metaphysical findings associated, the study also found that prevailing health concerns were used by the leaders to address health concerns. These findings shed light on the interconnections between leadership and culture as well as community processes, which are fundamental responsiveness tenets in OHLR (Farmanova et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, it illustrates the context-specific tenets of critical health literacy as articulated by Abel et al. (Citation2022) that, when consideration is given to individual and collective agencies within a socio-political context, “reflection” and “action” are key for improved health literacy. The leaders are reflecting—examining the daily realities of the congregation—and taking action—clearly engaging collective effort—to address health concerns with ramifications for health literacy. These findings further buttress the assertion that the willingness of individuals to exercise control about health decisions has potential impacts on community wellbeing (Chinn & McCarthy, Citation2013) and that given individual and collective agency in critical health literacy discourse, individuals are active players whose decisions and behaviors can alter structural conditions and affect the collective (Abel & McQueen, Citation2021).

Factors that do or could support health literacy work that were identified were availability of audio-visual materials, the presence of bridging social capital, health experts’ accessibility, availability to measurement medical devices, and obtainability of physical space. Audio-visual materials (i.e., information, communication, and education materials) are perceived as assets to be built through health education and communication with the resolution of boosting health decision-making (Nutbeam, Citation2008). This finding is consistent with what Platter et al. (Citation2022) found in their Maryland study, where participants identified community outreach and education materials (print pamphlets, hotlines, community services in language understood by the community) as assets. With health literacy meaning different things for different people (Baker, Citation2006), so are factors that do or could support health literacy for diverse organizations. Platter et al. (Citation2022) studied a wide array of organizations—e.g., health departments, hospitals, community health centers, faith-based organizations, and public schools. Therefore, with a wide range of organization with varying focus yielded assets including navigation services and health literacy material evaluation; the most cited health literacy asset was data collection to inform health literacy practices. While Platter et al. (Citation2022) deemed assets to be inclusive of health literacy activities, in the context of the faith-based organizations in Ghana, we found that although assets and health literacy activities are connected, they are substantially different.

Regarding health literacy gaps, inadequate IEC materials for health education programs were the most cited factor inhibiting health literacy work. The study found that participants perceived IEC materials enable health decision-making of members. These findings epitomize Nutbeam (Citation2008) summary of the public health perspective of health literacy as an outcome of a health communication program with the potential of helping people develop competences for actions to promote good health decision-making. Inadequate funding for health literacy work, which was identified as an inhibiting factor, was also identified as a gap in the Maryland study by Platter et al. (Citation2022). While Platter and colleagues found that there were not enough staff to enable collection of health literacy data (deemed as assets), this study found that insufficient health experts in their congregations to ensure authenticity of health messages from the pulpit was a prohibiting factor in health literacy work.

6. Conclusion

This study has sought to undertake a health literacy assessment of faith-based organizations in a developing country context. It sought to understand the complexities in the way religious organizations define health literacy, as well as nuances in health literacy assets and gaps. While there are multiple meanings associated with health literacy, the study found that the provision of right or correct health information to members was the most cited meaning. The organizations make a conscious effort to identify health literacy concerns among their members through direct idea solicitation, medical personnel members’ expertise, members’ medical status, and organizations’ health department. The most cited factor that do enhance health literacy work was the availability of health professionals in the organization, while the critical health literacy gap most mentioned was insufficient information, education, and communication materials.

The results of this study suggest implications for future health literacy research in a faith-based context. The finding that although assets and health literacy activities are connected but differ substantially, calls for examination of the dynamics of health literacy activities, including programs, resources, or interventions being implemented to address health literacy among faith-based organizations. Additionally, the inherent hierarchical nature of diverse religious organizations, given the prevailing socio-political context, is grounds for assessing the processes and patterns by which organizations engage, reflect, and act to promote high health literacy goals and, by extension, health equity over time.

Availability of data and materials

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Delaware State University Institutional Review Board. Also, the Ethics Review Committee of the Ghana Health Service approved this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express our appreciation to the National Science Foundation for funding this research from which this paper was developed (Award #2100825). We are grateful to the organization leaders and research participants in the study area for their involvement. We appreciate the research assistants for their contribution and dedication to this project. The authors would like to acknowledge the CITADEL Research Network for Development for their collaboration. We also owe colleagues a depth of gratitude for providing constructive comments, which have contributed to reshaping this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Raymond A. Tutu

Raymond Tutu is a Professor and the Chair of the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Delaware State University. His research interests lie in the areas of population health, human migration, human-environment interactions, water access, and health ecology.

Anwar Ouassini

Anwar Ouassini is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Delaware State University. His research interests include political sociology, sociology of health, sociology of religion, and comparative criminal justice systems. He is currently working on projects that explore the intersection of race and religious identities in the Arab World, the relationship between civil society, social movements, and democratic development in West Africa, and Criminal Justice Reform in the Maghreb.

Doris Ottie-Boakye

Doris Ottie-Boakye is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in the School of Public Health at the University of Ghana. She holds a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Population Studies from the Regional Institute for Population Studies, University of Ghana. Her research interests include population health, social protection strategies, and aging.

References

- Abel, T. (2008). Measuring health literacy: Moving towards a health-promotion perspective. International Journal of Public Health, 53, 169–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-008-0242-9

- Abel, T., Benkert, R., & van den Broucke, S. (2022). Critical health literacy: Reflection and action for health. Health Promotion International, 37(4), daac114. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac114

- Abel, T., & McQueen, D. (2021). Critical health literacy in pandemics: The special case of COVID-19. Health Promotion International, 36(5), 1473–1481. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa141

- Amoah, P. A. (2018). Social participation, health literacy, and health and well-being: A cross-sectional study in Ghana. SSM-Population Health, 4, 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.02.005

- Amoah, P. A., & David, R. P. (2020). Socio-demographic and behavioral correlates of health literacy: A gender perspective in Ghana. Women & Health, 60(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1613471

- Amoah, P. A., Phillips, D. P., Gyasi, R., Koduah, A., Edusei, J., & Lee, A. (2017). Health literacy and self-perceived health status among street youth in Kumasi, Ghana. Cogent Medicine, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2016.1275091

- Andrulis, D. P., & Brach, C. (2007). Integrating literacy, culture, and language to improve health care quality for diverse populations. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(1), S122–133. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.16

- Association for Community Health Improvement. (2017). Community health assessment toolkit. Retrieved from http://www.healthycommunities.org/Resources/toolkit.shtml#.XDE1Xs9KhsN

- Baker, D. W. (2006). The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(8), 878–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x

- Bakker, M. M., Putrik, P., Aaby, A., Debussche, X., Morrissey, J., & Råheim Borge, C., & . (World Health Organization, & . (). . , (), .2019). Acting together–WHO National health literacy demonstration projects (NHLDPs) address health literacy needs in the European region. Public Health Panorama, 5(2–3), 123–329.

- Barmania, S., & Reiss, M. (2020). Health promotion perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of religion. Global Health Promotion, 28(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975920972992

- Barry, M. M., D’Eath, M., & Sixsmith, J. (2013). Interventions for improving population health literacy: Insights from a rapid review of the evidence. Journal of Health Communication, 18(12), 1507–1522. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.840699

- Baumeister, A., Chakraverty, D., Aldin, A., Seven, Ü. S., Skoetz, N., Kalbe, E., & Woopen, C. (2021). “The system has to be health literate, too”-perspectives among healthcare professionals on health literacy in transcultural treatment settings. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06614-x

- Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., & Crotty, K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

- Brega, A. G., Freedman, M. A., LeBlanc, W. G., Barnard, J., Mabachi, N. M., Cifuentes, M., Albright, K., Weiss, B. D., Brach, C., & West, D. R. (2015). Using the health literacy universal precautions toolkit to improve the quality of patient materials. Journal of Health Communication, 20(sup2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1081997

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Community health assessments and health improvement plans. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/stltpublichealth/cha/plan.html

- Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean?(or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44(5), 681–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3

- Chinn, D., & McCarthy, C. (2013). All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS): Developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 90(2), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.019

- Cochrane, J. R., McFarland, D. A., & Gunderson, G. R. (2014). Mapping religious resources for health: The African religious health assets programme. In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp. 344–364). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199362202.003.0023

- Coughlan, D., Turner, B., & Trujillo, A. (2013). Motivation for a health-literate health care system—does socioeconomic status play a substantial role? Implications for an Irish health policymaker. Journal of Health Communication, 18(sup1), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.825674

- de Graft Aikins, A., Boynton, P., & Atanga, L. L. (2010). Developing effective chronic disease interventions in Africa: Insights from Ghana and Cameroon. Globalization and Health, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-6-6

- Dietscher, C., & Pelikan, J. M. (2017). Health-literate hospitals and healthcare organizations—results from an Austrian Feasibility Study on the self-assessment of organizational health literacy in hospitals. In 1st Ed. Health Literacy, Forschungsstand und Perspektiven. Hogrefepp. 303–314.

- Evans, A. Y., Anthony, E., & Gabriel, G. (2019). Comprehensive health literacy among undergraduates: A Ghanaian University-based cross-sectional study. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 3(4), e227–237. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20190903-01

- Farmanova, E., Bonneville, L., & Bouchard, L. (2018). Organizational health literacy: Review of theories, frameworks, guides, and implementation issues. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 55, 0046958018757848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958018757848

- Gele, A. A., Pettersen, K. S., Torheim, L. E., & Kumar, B. (2016). Health literacy: The missing link in improving the health of Somali immigrant women in Oslo. BioMed Central Public Health, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3790-6

- Hebert, P. L., Sisk, J. E., & Howell, E. A. (2008). When does a difference become a disparity? Conceptualizing racial and ethnic disparities in health. Health Affairs, 27(2), 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.374

- Hood, L., & Auffray, C. (2013). Participatory medicine: A driving force for revolutionizing healthcare. Genome Medicine, 5(12), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/gm514

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jacobson, K. L., Gazmararian, J. A., Kripalani, S., McMorris, K. J., Blake, S. C., & Brach, C. (2007). Is our pharmacy meeting patients’ needs? A pharmacy health literacy assessment tool user’s guide. Agency for Healthcare Research.

- Kuperus, T. (2018). Democratization, religious actors, and political influence: A comparison of Christian councils in Ghana and South Africa. Africa Today, 64(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.64.3.02

- Ladin, K., Buttafarro, K., Hahn, E., Koch-Weser, S., & Weiner, D. E. (2018). End-of-life care? I’m not going to worry about that yet.” Health literacy gaps and end-of-life planning among elderly dialysis patients. The Gerontologist, 58(2), 290–299.

- Lori, J. R., Dahlem, C. H. Y., Ackah, J. V., & Adanu, R. M. K. (2014). Examining antenatal health literacy in Ghana. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 46(6), 432–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12094

- Malloy-Weir, L. J., Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Entwistle, V. (2016). A review of health literacy: Definitions, interpretations, and implications for policy initiatives. Journal of Public Health Policy, 37(3), 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2016.18

- Mammana-Lupo, V., Todd, N. R., & Houston, J. D. (2014). The role of sense of community and conflict in predicting congregational belonging. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21596

- Morgan, D. L. (1993). Qualitative content analysis: A guide to paths not taken. Qualitative Health Research, 3(1), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239300300107

- Nutbeam, D. (2008). The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2072–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050

- Peprah, P., Gyasi, R. M., Adjei, P. O., Agyemang Duah, W., Abalo, E. M., & Kotei, J. N. A. (2018). Religion and Health: Exploration of attitudes and health perceptions of faith healing users in urban Ghana. BioMed Central Public Health, 18(1), 1358. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6277-9

- Platter, H., Kaplow, K., & Baur, C. (2019). Community health literacy assessment: A systematic framework to assess activities, gaps, assets, and opportunities for health literacy improvement. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice, 3(4), e216–226. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20190821-01

- Platter, H., Kaplow, K., & Baur, C. (2019). Community health literacy assessment: A systematic framework to assess activities, gaps, assets, and opportunities for health literacy improvement. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice, 3(4), e216–226.

- Platter, H., Kaplow, K., & Baur, C. (2022). The value of community health literacy assessments: Health literacy in Maryland. Public Health Reports, 137(3), 471–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549211002767

- Santos, P., Sá, L., Couto, L., Hespanhol, A., & Hale, R. (2017). Health literacy as a key for effective preventive medicine. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1407522. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1407522

- Sørensen, K., Levin-Zamir, D., Duong, T. V., Okan, O., Brasil, V. V., & Nutbeam, D. (2021). Building health literacy system capacity: A framework for health literate systems. Health Promotion International, 36(Supplement_1), i13–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab153

- Sørensen, K., Van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., Slonska, Z., & Brand, H. (2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BioMed Central Public Health, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

- Squiers, L., Peinado, S., Berkman, N., Boudewyns, V., & McCormack, L. (2012). The health literacy skills framework. Journal of Health Communication, 17(sup3), 30–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.713442

- Thomacos, N., & Zazryn, T. (2013). Enliven organisational health literacy self-assessment resource. Melbourne: Enliven & School of Primary Health Care, Monash University.

- Trezona, A., Dodson, S., & Osborne, R. H. (2017). Development of the organisational health literacy responsiveness (Org-HLR) framework in collaboration with health and social services professionals. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2465-z

- Tutu, R. A., Gupta, S., & Busingye, J. D. (2019). Examining health literacy on cholera in an endemic community in Accra, Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Tropical Medicine and Health, 47(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0157-6