?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

One of the outlining challenges of the twenty-first century is managing rapidly urbanizing cities. If managed well and guided by sound urban governance principles, cities can act as instruments of growth, and the goal of urban sustainability can be realized. On the other hand, poorly governed cities can become hubs of poverty, disparity, and conflict. Thus, this study is aimed to explore the implementation of urban governance principles in Gondar city. UN-Habitat’s Urban Governance Index (UGI) is employed as an analytical framework. UGI is a straightforward, easy, and flexible framework suited to measure the quality of urban governance practices in the local context. This study’s data included quantitative and qualitative data related to customer satisfaction in service delivery, citizen charter, access to electricity, waste management, water supply connections, pro-poor water policy, citizen involvement in decision-making, and incentives for the informal market. The result indicated that the highest values had been achieved in the effectiveness and accountability sub-indexes, with scores ranging between 0.65 and 0.56, respectively. Similarly, the lowest values have been recorded in equity and participation sub-indexes with scores between 0.44 and 0.37, respectively. The results revealed that the city still needs to implement sound governance principles. Therefore, attention should be given to implementing good urban governance principles to achieve the city we need that fits the smart city paradigm. Innovative structures with systems to implement UGI should be needed for sustainable urban development and to make our cities livable and competitive in the paradigm of sustainable cities.

Public Interest Statement

Managing rapidly urbanizing cities becomes one of the outlining challenges in the developing world. If managed well using sound urban governance practices, cities can act as instruments of growth, and the goal of urban sustainability can be realized. Even though good city governance is crucial to realize urban development’s sustainability and achieving a better quality of life, attention is not given to study urban governance in cities of developing countries. Particularly, quantifying governance qualities is not evident. Hence, this research is initiated to examine urban governance practices in Gondar city, Ethiopia. The study attempted to provoke policymakers, practitioners, and municipal administrators to look for appropriate mechanisms to satisfy the maximum needs of the urban society. The study attempted to identify institutional weaknesses, highlight experiences of good urban governance, lay the foundations for further policy analysis, and suggest the way forward to make our cities livable and competitive in the paradigm of sustainable cities.

1. Introduction

Urban growth is a worldwide miracle that represents growth in the percentage of the urban population and the physical expansion of existing urban areas (Leulsegged et al., Citation2012; Mezgebo, Citation2021). Urban residents were only 28.8% of the world population in 1950 and increase to 56% in 2030 (Beringer & Kaewsuk, Citation2018). According to (Fitawok et al., Citation2020), this rapid change in urban population mainly resulted from rural-urban migration, the developing of small regional towns into cities, and population growth. By 2050, it has also been estimated that around 70% of the world’s population is likely to live in urban cores, mainly in developing countries (Avis, Citation2016). Africa and Asia have been experiencing a rapid upturn in the percentage of urban inhabitants and are expected to rise faster in the coming years (Gashu, Citation2019; Tassie Wegedie & Duan, Citation2018).

This faster urban population growth rate for developing countries (2.3%) as compared to developed countries (0.4%) demands proper urban governance practices. Consequently, in the past few years, urban sprawl has occurred in developing countries, and it is estimated that 1 billion and above will live in urban Africa. This will triple the current number of urban residents in Africa, representing the fastest rate of urbanization (Gashu & Gebre-Egziabher, Citation2018; Habitat, Citation2017). During this time, it is common to observe uncontrolled and unplanned land-use changes, governance complications, and other socio-economic problems in urban Africa (Fitawok et al., Citation2020; World Bank Group, Citation2019). Furthermore, rapid urbanization has advantages and challenges in urban areas of the world (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). For instance: illegal land use changes, social inequalities, insufficient access to utility and infrastructure services, increased cost of living, pollution, unemployment, traffic congestion, homelessness, expanded slum, and squatter settlements, and poor health and educational services are some of the challenges resulted from rapid urban expansion in developing countries including Africa (UNDP, Citation2016; UN‐Habitat, Citation2016). With rapid urbanization, urban poverty is also accelerating in developing countries (Jones, Cummings, et al., Citation2014). The challenge is severe, in the poorest states, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia. In this region, population increase is more rapid than the capacity of planners to deliver the required infrastructure for urban dwellers, consequently challenging urban planners, infrastructure managers, and policymakers (Falah et al., Citation2020).

Ethiopia has a faster urbanization rate in the Sub-Saharan African countries, with a 4.03% growth rate per annum (WORLD BANK GROUP, Citation2018). Although the degree of urbanization is fast, Ethiopia is among the least urbanized nations in the world, with 21% of its residents inhabited in urban centers (Mezgebo, Citation2021). By 2050 it is estimated that the rate of urbanization is projected to reach 4.4%, which is above the expected 2% growth rate of urban Africa (Mezgebo, Citation2014). This speed of growth has led to an ever-increasing demand for infrastructure utility services (Adam, Citation2014b). The existing infrastructure and utility services will need to be improved to meet the urban society’s demand in many towns due to rapid urbanization (Adam, Citation2014a; Ermias et al., Citation2019).

In Africa, including Ethiopia, a severe mismatch between rapid urbanization and infrastructure planning and availabilities is highly observed. The problems, including infrastructure planning, inappropriate land use, waste, and environmental management, must be matched with rapid urbanization (Gashu, Citation2019; Habitat, Citation2017). Similarly, with appropriate governance and effective policies to deliver services, the problems are manageable (Tegegne, Citation2015). Consequently, urban governance needs to work based on a plan to realize urban development’s sustainability and achieve a better quality of life (Avis, Citation2016; Jones, Clench, et al., Citation2014). It is also crucial to ensure access to urban services for the wider urban population and the urban poor.

Similarly, Kevin et al. (Citation2016) suggested that good city governance plays a vital role in determining urban areas’ physical and societal character. It also determines local service delivery and engages the urban poor in decision-making. Moreover, Government or municipal interventions in green infrastructure expansion in cities and towns have a vital role in maintaining the aesthetic value and sustainability of the urban environment (Lopes et al., Citation2022), by which cities become climate resilience and tourist attraction sites (Mehryar et al., Citation2022). But, the study of urban governance has gained attention more recently, and Ethiopia has accepted the significance of good governance in trying to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Tassie Wegedie & Duan, Citation2018).

According to the World Bank Group (Citation2019), Ethiopian urbanization still needs to meet the demands of urban residents in unemployment, housing, utility, and infrastructure services. Similarly, the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development reported that about 70% of the urban population in Ethiopia is considered slum dwellers. The quality of housing, living spaces, access to and quality of infrastructure, and security of tenure are deprived of them (Yimam, Citation2017). If the present trend continues, realizing sustainability and better quality of life in cities will be challenging without changing the urban governance system (Kevin et al., Citation2016). Hence, this research is initiated to examine urban governance practices in Gondar City. Different models are employed to assess urban governance practices, including UNDP’s urban governance approach. However, this study has selected the UN-Habitat’s UGI, which is a clear, easy, and flexible framework suited to quantify governance qualities in the local context.

Gondar city is characterized by insufficient infrastructure, unemployment, debilitated houses, extremely limited water sewerages, and insufficient and unplanned roads (Fikadie et al., Citation2018). This is different from the idea that urban settings have to be planned to provide safe, organized, and enjoyable spaces with recreational settings for residents. Therefore, it is advisable to review the available knowledge and policy advice on service delivery governance to design the right plan and policies. Thus, this study aims to examine the practice of good governance principles in delivering urban services in Gondar city. This has been explored depending on the principles of the UGI developed by UN-Habitat. Since this study was not conducted in Ethiopia in general and in Gondar city in particular, it may act as a first spoon in quantifying city governance qualities in urban service delivery. It will provoke policymakers, practitioners, and municipal administrators to look for appropriate mechanisms to satisfy the maximum needs of the urban society. Furthermore, it will be an input for implementing the “Smart city” paradigm, a new and crucial urban agenda today. The study attempted to identify institutional weaknesses, highlight experiences of good urban governance, lay the foundations for further policy analysis, and suggest the way forward for Ethiopian urban centers regarding sustainable urban service delivery.

1.1. The objective of the study

This study has aimed to explore the implementation of urban governance principles using UN-Habitat’s urban governance index in Gondar city, North West Ethiopia

1.1.1. Research gap

Even though good city governance is crucial to realize urban development’s sustainability and achieving a better quality of life by reducing the mismatch between rapid urbanization and an ever-increasing demand for infrastructure and utility services, attention is not given to study urban governance in a measurable way in cities of developing countries. Particularly, quantifying governance qualities is not evident. So, since this type of study has not been conducted in Ethiopia in general and in Gondar city in particular, this study has been undertaken to fill such gaps in the literature.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area description

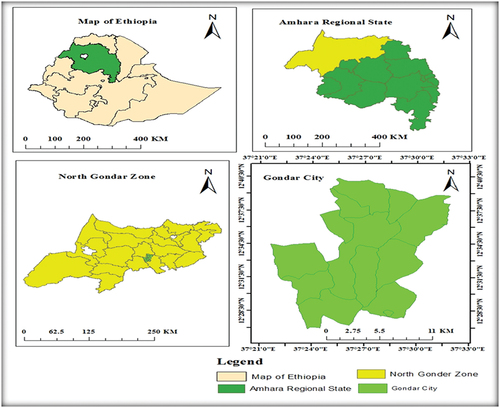

Gondar is among the fast-growing cities in Ethiopia and has a long history of urbanization (Gashu & Gebre-Egziabher, Citation2018). It was established in 1636 and served as the administrative capital for North Gondar Zone in the Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. It is found between 12°36′N latitude and 37°28′E longitude (Figure ) with a total area of 192.27 km2. It is a historical city where the remains of royal castles, including Fasil Ghebbi, for which Gondar has been known, are found. It is also one of the most tourist destinations for its original cultural facts, including the church of Kuskuam, Debre Birhan Selassie, Fasiledas Castle, and the swimming pool (Fikadie et al., Citation2018). According to Alemineh (Citation2018). Gondar’s total population is about 306 246. The city is characterized by congestion, debilitated houses, extremely limited water sewerages, insufficient and ill-planned roads, etc. (Fikadie et al., Citation2018). The city is expanded to peripheral areas mainly due to an increase in its population. So, it was restructured into six sub-city administrations.

2.2. Data sources

Both quantitative and qualitative data were used in this study. The qualitative data is comprised of customer satisfaction in service delivery, citizen charter, access to electricity, waste management, water supply connections, citizen involvement in decision-making, and incentives for the informal market. This data has been extracted using a questionnaire, interview, and observation. The quantitative data was extracted from secondary sources, including profiles and documents at Gondar city administration that include government laws, rules, and regulations of Ethiopia at the federal and local levels. Accordingly, the percentage of women councilors from the house of Afe-Gubae (Speakers) and the share of women in key positions from the Women’s affairs department of Gondar city have been extracted to calculate the share of women councilors & women in critical positions, respectively. Population data for the years 2018, 2019, and 2020 from the plan commission and the annual income of the city for the same years from the department of Revenue of Gondar City were collected to calculate the value of indicators like the ratio of actual recurrent to the capital budget, the ratio of mandated to actual tax and Predictability of transfers. The data relating to the disclosure of personal income & assets, corruption control mechanisms, regular independent audits, and citizen complaints facilities were extracted from profiles and documents of Gondar City. In addition, some data were collected from civic associations to calculate the value of the number of civic associations.

2.3. Sample size determination

Probability and non-probability sample selection procedures were employed to gain samples. A multi-stage sampling technique was preferred to select samples from the sample frame. First, from the existing six sub-cities of Gondar city, three sub-cities: Azezo Tseda, Maraki, and Arada were selected purposively, where the majority of people evicted by urban problems have been living. Second, one kebele (the smallest unit in the administrative structure) from each sub-city was selected purposively (Shiro Meda from Maraki, Ayra from Azezo Tseda, and Kidamie Gebeya from Arada). Finally, sample households from each kebele have been selected systematically.

Accordingly, 548 household heads (200, 150, and 198 in Shiro media, kidamie gebeya, and Ayra kebeles, respectively) were selected as a sample. A scientific formula adopted from Israel (Citation1992) was employed to decide the study’s sample size. It was calculated as n = where n = the required sample size, N =Total population, and e = level of precision. Thus, the required sample size becomes n =

= 231 samples.

2.4. Data analysis methods

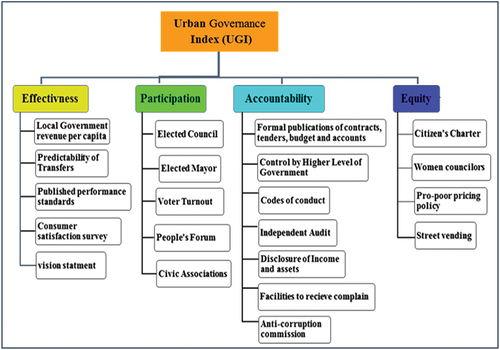

The data collected about the urban governance practices of Gondar City were analyzed by using the UN-Habitat’s UGI as an analytical tool. The UN-Habitat UGI has employed four major urban principles, such as Effectiveness, equity, accountability, and participation, to analyze urban governance practices (WORLD BANK GROUP, Citation2018). Unlike other models, such as UNDP’s urban governance approach, UGI has a flexible, easy, and clear framework that can be applied to measure the quality of governance in the local context (Biswas et al., Citation2019; Poorahmad, Citation2018). The model unique characteristics models unique characteristics have made it best fitted for this study. The UN-Habitat has been designed by employing 26 indicators for good urban governance under four principles (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). Indicators representing each of the sound urban governance principles were utilized in this study by employing both qualitative and quantitative data and analysis techniques. The data were analyzed concurrently, and the qualitative findings were used to give meaning to the quantitative findings.

The data collected through questionnaires, interviews, observation, and secondary sources were coded, tabulated, and organized according to their nature. The qualitative data were analyzed using the MAXQDA technique, while the quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 and Microsoft excel for simple averages, percentages, frequencies, tables, and graphs. Twenty-six indicators identified by UGI have been grouped under four principles: Effectiveness, participation, accountability, and equity (Figure ).

The study to analyze UGI principles has employed a standard procedure of normalization, providing weight for each indicator and aggregating their results into indices to simplify the data from various sources into standard units (See Table ) below:

Transformation of “yes”/”No” responses for the binary (qualitative) data into a score of “1” or “0”.

Transforming and normalizing the value for the variables gained in the survey using the highest and lowest known values.

Calculate each indicator’s share in which the score ranges between “0” and “1”. The score of quantitative indicators ranges from “0” to “1”. “1” and “0” represents excellent and poor performance, respectively. Similarly, since the qualitative indicators were binary, the score was assigned as “0” and “1”, where “0” and “1” indicates poor and excellent performance, respectively (Administration et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Analysis of the UGI

The ratios, shares, and proportions have been considered to indicate the gap existing in the city. Finally, the results for all indicators under each sub-index were multiplied by their respective weight and aggregated to calculate the value for respective sub-indexes. The value for each sub-indexes ranges from “0” to “1”. Here, “1” and “0” indicates excellent and poor performances, respectively (Prak, Citation2018). Finally, the UGI was calculated as follows (Taylor & Halfani, Citation2004a).

The value from this result ranges between zero and one. One and zero represent excellent and poor performance, respectively (Ur Rehman, Citation2017).

3. Results

3.1. Background information of the respondents

About (67%) of the respondents were male, while the remaining (33%) were female (Table ). Similarly, about 24% were 20–30 years old, 35% constituted 31–40 years, 25% were within the age of 41–50, and 11% were 51–60. This implies that most participants were mature enough to have relevant information for the study. Furthermore, about 15% were illiterate, 8% could read and write, 15% were in elementary, 24% had enrolled in high school, and about 38% were in college and above. This indicates that the majorities of participants were literate and were able to give valuable information and constructive suggestions for the study. About 61% of respondents were identified as married, while the remaining 28% and 11% comprise not married and divorced respondents, respectively (Table ). In this regard, most were married and could carry out their responsibility of giving valuable information. It could be a representative sample of many other populations as they may have a large family under them with a similar opinion. Regarding occupation, 48% of respondents were self-employed, followed by 29% unemployed, while the remaining 20% and 3% constituted government and NGO employed, respectively. This indicates that the majority were employing themselves using different activities.

Table 2. Background of the respondents

3.2. Implementation of urban governance index in service delivery

3.2.1. Effectiveness sub-index

In local government, Effectiveness depicts the city’s functioning concerning the quality and cost of provided services (McCann, Citation2017; Prak, Citation2018). It reflects the methods to ensure the effective delivery of public services to urban society (Administration et al., Citation2019; Hendriks, Citation2014). The most powerful indicators identified by the U.N. habitat to measure the effectiveness sub-index include Local government revenue per capita, the Ratio of mandated to actual tax, the Predictability of transfers in the local government budget, published performance delivery standards, and so on (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). Accordingly, the effectiveness sub-index in the city of Gondar has been assessed based on these measurement indicators as follows:

The average per capita income of Gondar city between 2018 and 2020 was 50$ per person per year. The city’s highest and lowest revenue/per capita values have also been recorded as 66$ and 34$, respectively. The total population for 2018, 2019, and 2020 were 390,644, 411561, and 432,191, respectively. As a result, the actual local government revenue per capita of Gondar city becomes 0.167 out of 0.25 (Table ). This indicates that the city has the potential financial capacity to ensure the efficient delivery of urban facilities to its residents. The ratio of the actual recurrent and capital budget for the city was recorded as 0.079 from 0.10 (Table ). This value implies that the city is relatively good in financial sustainability and Effectiveness (Prak, Citation2018).

Table 3. Effectiveness sub-index

Similarly, the ratio of mandated to the actual city tax becomes 0.075 out of 0.10, respectively. This reflects the efficiency of tax collection in the city, and citizens willing to pay taxes are found in a good situation (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). Moreover, its revenue contains a transfer of 90%, by which it has scored 0.025 out of 0.10 (Table ). This indicates that the city administration is more financially dependent on higher government structures. The city government budget Transfers’ Predictability has also been recorded as 0.10 from 0.10 (Table ). This value displays the financial autonomy of the city to meet the service demands of urban society. Financial autonomy in urban governance is highly correlated with a good financial situation to meet service demands (Biswas et al., Citation2019). Publication of performance delivery standards for essential services was also available in the city. As it was evaluated for five critical services, such as solid waste management, electricity, water supply, sanitation, health, and education, the city scored 0.15 out of 0.15 (Table ). All these services have delivery standards developed by respective bodies in the federal government. These standards make the local government efficient in delivering essential services to urban society (Administration et al., Citation2019). However, urban residents in the city needed to be made aware of such information.

Furthermore, Gondar city has put a vision statement to see the urban population of Gondar city being prosperous in economic, social, and political aspects in 2022. The value for the indicator was recorded as 0.05 out of 0.10. This was because the vision statement needed to be drafted in a participatory manner. In addition, contrary to good governance, the city needed to conduct a customer satisfaction survey for necessary feedback. This implies that the local authority is unwilling to receive a public opinion from local residents (Prak, Citation2018). Finally, the city has scored a value 0.65 out of 1 for the effectiveness sub-index of urban good governance (Table ). This indicates that the city has scored relatively good on the sub-index as most of the standards for the respective indicators have been met. However, as reflected in the survey data, its implementation in an actual situation needs to be revised.

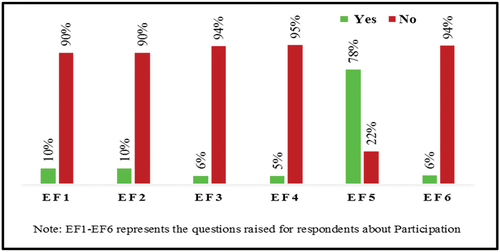

The study assessed urban respondents’ satisfaction levels. Accordingly, most (90%) of respondents were not satisfied with urban service provision (EF1 in Figure ). Similarly, majorities were not clearly informed and easily accessible about urban services (EF2 in Figure ). About 94% replied that they could not afford it, implying that the cost of service provision could be more affordable by most of the urban society. Accordingly, about 95% were not satisfied with the performance of urban officers, but about 78% confirmed that a bureaucratic procedure delayed service provision. Regarding the level of urban good governance practices, the majority (94%) of respondents claimed that the urban governance practices are not in good condition; instead, it is easy to say that urban governance in the city is not good. In general, the data from the participants highly deviates from the information from secondary sources.

3.2.2. Participation sub-index

Participation indicates the methods of building local solid representative democracies through inclusive and fair municipal elections (Badach & Dymnicka, Citation2017; Hendriks, Citation2014). All sections of urban society should have a voice in decisions that impacts their quality of life (Biswas et al., Citation2019; Poorahmad, Citation2018). Therefore, the participation sub-index for the city of Gondar has been analyzed considering its most essential indicators identified by UN-Habitat as follows:

The participation sub-index was recognized as poor, with an average score of 0.37 out of 1 (Table ). This was due to a need for a locally elected council and mayor from the local people. Instead, they were appointed by the political party. Similarly, participatory activities for public participation were not created due to the absence of directly elected councils. Gondar city scored 0 from 0.15 as its elected council is an appointed one instead elected one (Table ). This indicates that the city administration needs to achieve good governance concerning the elected council to be responsive to the necessities of the urban society (Biswas et al., Citation2019). The value of the Mayor Election was 0.11 out of 0.15 as the elected mayor in the city was elected amongst the councilor members than elected directly. This implies a low level of citizen participation in Mayor Elections, which fails to achieve sound governance principles to be exercised. In addition, the value for the indicator of voter turnout has been observed as 0.009 out of 0.30 (Table ). Moreover, the city has scored 0 from 0.15 for the indicator of People’s forum as it does not perform in the expected way (Table ). This reveals, the local population needs a chance to participate in the administrative process of local policies and budgets (Meyer & Auriacombe, Citation2019). Several civic associations have been registered in the city, for which it has scored 0.25 out of 0.25 (Table ). This could increase the possibility of the poor or minority groups being well-denoted in city governance (Prak, Citation2018). Generally, the participation sub-index was recognized as poor, with an average score of 0.37 out of 1 (Table ).

Table 4. Participation sub-index

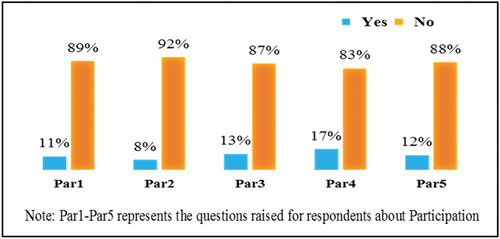

The citizens’ participation was assessed against the criteria related to urban service provision locality, and about (89%) believed that citizen participation in the urban service delivery process needed to be improved (Par1 in Figure ). Similarly, the majority (92%) of respondents replied that local authorities needed to better consider urban service provision in the city and were not willing to consider public opinion while performing urban services. Thus, about 87% strongly disagreed with the question about the availability of suitable comment-receiving mechanisms of institutions in their locality. This shows urban institutions in the city needs proper comment-receiving mechanisms to ensure the needs of urban residents. Furthermore, about 83% of the respondents said that officers assigned to urban governance institutions were not interested in solving existing urban problems. They also confirmed (88%) that disadvantaged groups were not considered when implementing good urban governance practices. In general, the municipality discards community involvement, which fails to ensure the needs of the general public. Participants in the interview provided similar ideas to this survey. They have reported as administrators are not willing to create a favorable and relaxed environment for us to participate in our concerns, especially since land provision is mistreated. Rental houses and food prices are not also affordable and the thefts become severe problem in the city.

3.2.3. Accountability sub-index

Accountability is one of the five principles constituting the UGI (Taylor & Halfani, Citation2004a, Citation2004b). The local government should be obligated to be responsible or transparent to its service users. Recognizing the urban poor is also crucial in urban transparency (McCann, Citation2017). Therefore, the accountability sub-index for the city of Gondar has been analyzed considering its most essential indicators identified by UN-Habitat as follows:

The accountability sub-index of Gondar city has been recorded as 0.56 out of 1, which meets around half of the standard of it (Table ). The city has been performing 0.10 out of 0.20 for the formal Publication of contracts/tenders, budgets & accounts (Table ). This indicates that the city administrators cannot make information available to the public and are not willing to be transparent in conducting activities. The values for Independence and responsiveness have been also recorded as 0.035 from 0.08 and 0.02 out of 0.07, respectively. The scores present that the higher government can remove any locally elected councilor, whereas the value for the latter tells us local administrators have no power to impose the local tax, customer surcharges, and borrow funds for specific projects. This situation makes local authorities accountable upward to their bosses rather than downward to the community (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). The value for the code of conduct was recorded as 0.10 out of 0.10. This is due to a signed published standard of conduct for each activity being available (Table ).

Table 5. Accountability sub-index

In addition, the city has scored 0 out of 0.10 for the facility of citizen complaints (Table ). This happened because of the failure of the city to achieve the expected issues and the need for proper responses to complaints in the city. Moreover, the city administration has scored a value of 0.15 out of 0.15 for an anti-corruption commission in the city. This can be evidence of the need for more commitment from urban administrators to accountability and transparency (Habitat, Citation2017). In the same way, respondents during the survey stated that an anti-corruption commission is there but not providing a proper function to address its intended objectives (Figure ).

Furthermore, the value for disclosure of income & assets was obtained as 0 out of 0.15, as the city scores 0 for all variables under this indicator (Table ). This implies that more needs to be done about regularly monitoring income and assets for officers in the city. In this regard, locally voted administrators should be obliged to openly disclose their income and properties before taking office (Poorahmad, Citation2018). Against a law that obligates officers to disclose their income/assets, they have tried to disclose after having an office instead of before taking office. The value for independent audit was also recorded as 0.15 out of 0.15 since a regular audit report is available at every financial institution within the city (Table ). This reflects local administrators are accountable and transparent in resource allocation and use (Ur Rehman, Citation2017).

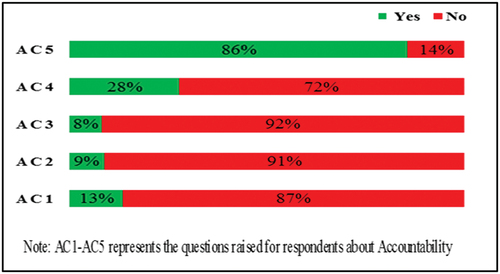

Similarly, accountability was considered, and the majority (87%) replied as there was no mechanism to make officials accountable for their actions (Figure ). The finding was similar to those (Administration et al., Citation2019; Biswas et al., Citation2019) in that they argued for good urban governance to be practically implemented, and different mechanisms which make officials responsible for their action should be available. This was also reflected in the perception of the existence of transparency in the urban service provision processes. Accordingly, the majority (91%) replied as service providers in their locality need to be more transparent. Officials in Gondar city need to be more transparent with the urban community while performing their activities. Moreover, about 92% of respondents disagree with the application of rules and regulations of service provision in their locality (Figure ). In addition, about 72% replied as no appeal mechanism was available for misconduct (Ac4 of Figure ). This indicates that the appeal mechanism available in the city of Gondar is either limited or unavailable. Moreover, about 86% of the respondents claimed as they had been asked for unreasonable payments by officials for the services delivered to them. The interview participants have also argued that local administrators are not accountable since they are appointed for a political purpose rather than serving the local community. They have replied as there was no periodic monitoring and evaluation system for urban officers. They have said that urban services were provided for specific individuals without an official schedule. This results in various problems/illegal actions in urban governance/service provision within the city, such as corruption, rent-seeking, and bureaucratic delay in getting services. From this, we can understand that urban officers need to be fixed in the accountability sub-index.

3.2.4. Equity sub-index

Equity in urban governance implies providing equal access to essential services for all sections of the urban society as well as involving them in the decision-making process to maintain sustainability in urban areas (Meyer & Auriacombe, Citation2019; Ur Rehman, Citation2017). These should be exercised with a priority focus on pro-poor policies in the provision of urban services such as education, job opportunities, housing, clean water, electricity, sanitation, and others. The equity sub-index was assessed using the individual results of its important indicators identified by UN-Habitat as follows:

The issue of equity was also assessed, and its average sub-index score was 0.44 out of 1, which is below the average standard of UGI (Table ). This was due to needing to be more responsible for providing water and another critical service for all, and no check and control mechanism was put in place. The value for Pro-poor pricing policies for water becomes 0 out of 0.10 as it fails to make water prices cheaper for the urban poor (Table ). This implies there needs to be a mechanism to provide water, particularly on behalf of the urban poor in the municipality (Prak, Citation2018). Water price is similar for all sections of urban society regardless of their economic status. Only 18% of city households have water supply access in the city under study. Similarly, the city has scored 0 out of 0.15, which is unable to meet the standards of UGI in giving opportunities for informal business in the main retail area (Table ). On the other hand, the value for the Citizens’ charter was recorded as 0.20 out of 0.20. This was because of a signed, published statement about citizens’ rights of access to essential services such as waste management, water supply, electricity, health, sanitation, and education which shall be drafted by the people’s representatives (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). The ratio of women councilors and women in critical positions becomes 0.144 from 0.20 and 0.07 from 0.10, respectively. This indicates that the level of women’s representation in the city’s administrative process was relatively good compared with other indicators.

Table 6. Equity sub-index

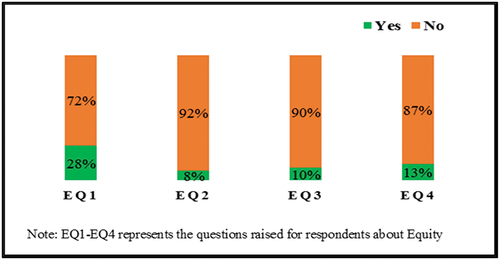

The results from items 1–3 below reveal that the urban communities in Gondar city were not equally treated in gaining access to essential urban services. As reflected in item 1 (EQ of Figure ), the majority (72%) replied as they were not gaining equal access to housing land. In item 2 (EQ2 of Figure ), the majority (92%) answered as they do not get access to urban services without discrimination. Regarding the impartiality of urban service providers, about 90% of participants were dissatisfied. In addition, item 4 (EQ4) shows that 87% of respondents answered as there were no fair compensations rewarded to all people who are losing their assets. This indicates that equity concerning access to urban services could be much higher in Gondar. The study also indicated that service provision to housing land, water, electricity, Job opportunities, and participation in small businesses differed. The data generated from open-ended questions and the key informants’ interviews also indicated that the urban poor and females are underestimated and considered incapable of holding public services.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have explored the practice of urban good governance principles using the UN-Habitat’s UGI as an analytical tool in the city of Gondar, Ethiopia. The index comprises four major principles, such as Effectiveness, equity, accountability, and participation (WORLD BANK GROUP, Citation2018).

With regard to Effectiveness sub index, we have explored both the success and failure of Gondar city using the respective values of indicators of the sub-index. Accordingly, the city was found successful in achieving indicators of Effectiveness sub-index such as local government revenue per capita, the ratio of the actual recurrent and capital budget, budget Transfers’ Predictability and performance delivery standards for essential services. The results gained on the ratio of the actual recurrent and capital budget for the city shows that the city is relatively good in financial sustainability and Effectiveness (Prak, Citation2018). The Good situation found in the value of ratio of mandated to the actual tax also reflects the efficiency of tax collection and citizens willing to pay taxes (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). The city government budget Transfers’ Predictability has also strengthen this reality as it displays the financial autonomy of the city to meet the service demands of urban society. Financial autonomy in urban governance is highly correlated with a good financial situation to meet service demands (Biswas et al., Citation2019). As it was evaluated for five critical services, such as solid waste management, electricity, water supply, sanitation, health, and education, all these services in the city have delivery standards developed by respective bodies in the federal government. These standards make the local government efficient in delivering essential services to urban society (Administration et al., Citation2019).

On the other hand we found Gondar city with the revenue transfer value reflecting that the city administration is more financially dependent on higher government structures. Furthermore, we found Gondar city with a vision statement which was not drafted in a participatory manner. This implies that the local authority is unwilling to receive a public opinion from local residents (Prak, Citation2018). Generally, the city has scored relatively good on the effectiveness sub-index as most of the standards for the respective indicators have been met (Table ). This indicates that Gondar city has the potential financial capacity to ensure efficient delivery of urban facilities to its residents (McCann, Citation2017). However, as reflected in the survey data, its implementation in an actual situation needs to be revised. Because, as reported by respondents, they were not satisfied with urban service provision and are not clearly informed and easily accessible. Scholars (CitationBadach & Dymnicka,Citation2017; Poorahmad, Citation2018) argue that information regarding urban service provision should be accessed freely and directly by all sections of urban society. But, contrary to this, information was not handy to the urban society living in the city.

The city’s performance related to the participation sub-index was recognized as poor, with an average score of 0.37 out of 1. This was due to the absence of a locally elected council and mayor from the local people. Instead, they were appointed by the political party. Similarly, due to the absence of directly elected councils, participatory activities for public participation were not created. This implies the city fails to achieve sound governance principles to be exercised. In addition, the value for the indicator of voter turnout reveals involvement of the urban society in a decision-making process is highly limited (Taylor & Halfani, Citation2004a). Moreover, the city has scored nothing for the indicator of People’s forum. From this, the local population needs a chance to participate in the administrative process of local policies and budgets (Meyer & Auriacombe, Citation2019). We found the city successful only in that civic associations have been registered in the city which could increase the possibility of the poor or minority groups being well-denoted in city governance (Prak, Citation2018). The data reported in the questionnaire and interview also confirmed that, citizens’ participation in decision making is limited as local authorities were not willing to consider public opinion while performing urban services. Disadvantaged groups were not considered when implementing good urban governance practices. In general, the municipality discards community involvement, by which it fails to ensure good governance practices.

As far as accountability sub-index of Gondar city is considered, the city administration achieves almost half of the standard for it. One of the weakness in this regard was that the city administrators cannot make information available to the public and are not willing to be transparent in conducting activities. Authors like (Administration et al., Citation2019; Biswas et al., Citation2019), argued that for good urban governance to be practically implemented, different mechanisms which make officials responsible for their action should be available. The other failure has been found in Independence and responsiveness of city administrators. The respective scores reveal that the higher government can remove any locally elected councilor and the local administrators have no power to impose the local tax, customer surcharges, and borrow funds for specific projects. This situation makes local authorities accountable upward to their bosses rather than downward to the community (Ur Rehman, Citation2017). In addition, the city has failed to achieve indicators like facility of citizen complaints and disclosure of income & assets. In this regard, locally voted administrators should be obliged to openly disclose their income and properties before taking office (Poorahmad, Citation2018). Against a law that obligates officers to disclose their income/assets, they have tried to disclose after having an office instead of before taking office. The city was successful only in an independent audit since a regular audit report is available at every financial institution within the city.

The data reported from respondents and interviewees also confirmed most of these realities mentioned above. Accordingly, mechanisms were not available to make officials accountable for their actions (Figure ). Poorahmad (Citation2018), have stated that transparency in providing services is the best solution to enhance some incidences of unlawful actions like corruption and rent-seeking behaviors. Scholars (Administration et al., Citation2019; Biswas et al., Citation2019) argued that information regarding urban service provision should be accessed freely by all sections of urban society. Contrary to this, public service users in Gondar city were not accessing timely information. In addition, we found that urban societies were asked unreasonable payments by officials for the services delivered to them and no appeal mechanism was available for the misconduct (Ac4 of Figure ). This results in various problems/illegal actions in urban governance/service provision within the city, such as corruption, rent-seeking, and bureaucratic delay in getting services.

With regard to equity sub-index, we have found the city with poor performance as it scores below the average standard of UGI. The main problems were identified as: failure to provide water and other service for all, to make water prices cheaper for the urban poor, to create opportunities for informal business, to provide equal access to essential urban services such as water, housing land, electricity, job opportunities etc., to consider disadvantaged groups and to give fair compensations to all who are losing their assets. The value for Pro-poor pricing policies for water shows as the city fails to make water prices cheaper for the urban poor (Table ). This implies there needs to be a mechanism to provide water, particularly on behalf of the urban poor in the municipality (Prak, Citation2018). A variety of authors also argued that local government intervention is vital to create opportunities for informal business in the principal retail zones of the city where informal street marketing is not permitted (Poorahmad, Citation2018).

In general, with regard to the challenges of managing rapidly urbanizing cities of the developing world, urban good governance is recognized as the key solution (Habitat, Citation2017). As can be described by various authors, government as an input is extremely significant in the case of infrastructure provision (Prak, Citation2018). But, attention is not given to study urban governance in cities of developing countries. Especially, quantifying governance qualities is not evident. Urban governance systems in most countries are currently not fit to enable sustainable urban development (Meyer & Auriacombe, Citation2019). So, this study has been undertaken to fill such gaps in the literature. The results of application of UGI on the local government of Gondar city have revealed, the city administration office lacks most of the required good governance dimensions in effectiveness, participation, accountability and equity. We can concluded that urban governance in the city is weak which leads to an ill-functioning service delivery system and needs to build a system that will promote all these principles of good urban governance. Here, the study highlights the available literature relating to the governance of service delivery in urban areas; hence, it will be of use to any future attempts to contribute to add knowledge and policy advice in this field. It is found to be used as a guide for municipal leaders and decision makers particularly in developing countries as it makes data to be available on the state of governance quality measures.

5. Conclusions

The practice of sound urban governance principles in the city of Gondar has been explored using the UN-Habitat’s UGI. The index focuses explicitly on improvements in the quality of local urban governments. The study has identified that the average UGI for the city of Gondar was 0.505 out of 1. The score indicates only half of its performance as compared to standards of good urban governance. From the four principles, the highest values have been recorded in the effectiveness and accountability sub-indexes, with scores of 0.65 and 0.56, respectively.

In contrast, the lowest values were recorded in equity and participation sub-indexes with scores of 0.44 and 0.37, respectively. The result reveals that Gondar city needs to focus on equity and participation sub-indexes while implementing urban good governance principles as it scores below the average standard of the UGI in such sub-indexes. The main reasons contributing to the poor status of urban governance in Gondar city were identified as: failure to make water prices cheaper for the urban poor, unable to create opportunities for informal business, absence of locally elected council/mayor rather appointed, absence of a pro-poor policy, failure to disclose income and assets of officers, absence of facilities to receive complaints, no participatory arrangements for community involvement, corruption, rent-seeking, lack of mechanisms to make officials answerable on behalf of their mistakes, absence of performance delivery standards and People’s forum, voter turnout and discrimination. In addition, administrators give primate recognition for their political faithfulness to their boss other than settling their duties. Therefore, for a good urban governance to be better implemented, due attention should be given for those problems mentioned above. Innovative structures with systems in implementing the UGI should be needed for sustainable urban development and to make our cities livable and competitive in the intelligent paradigm of Cites.

5.1. Implications for policy makers

The results from the study reveals that:

Administrators and municipalities in Gondar city needs to improve the participation of the urban community and other stakeholders on the decision making process of urban services.

They should give opportunities for the urban residents to be actively participate in the decision making process of the governance aspects.

In addition, it is advisable to create a conducive work environment to the community integrating with governmental and non-governmental institutions.

Administrators of the city should facilitate citizen’s participations in mayor election, create opportunities for informal business, initiate pro-poor pricing policies,

It is also recommended to design suitable comment receiving mechanisms, putting ethical and professional standards and evaluate its progress timely,

Taking corrective measures on ill functioning officers at respective sectors should be the major assignment for municipalities/administrators of Gondar city to be effective in implementing good urban governance principles.

In General, policymakers, practitioners, and municipal administrators should follow appropriate mechanisms to satisfy the maximum needs of the urban society.

5.2. Limitations and future research

Even though urban governance problems were observed throughout Ethiopian cities and towns, this study was limited to Gondar city administrative zone of Ethiopia due to time and cost limitations. Therefore, additional empirical and comparative studies are needed hardly. Because, future research in this field is extremely important to evaluate governance qualities with measurable service delivery outcomes. This could be done by either comparing the overtime changes of outputs in a single city or by making comparison between cities of similar status. So, this study attempts to provide a clue for the studies in the future in the field.

Author Contributions

Ergo Beyene wrote the main manuscript text including Conceptualization, Methodology, Data preparation and analysis. Amare Sewnet Minale and Achamyeleh Gashu Adam has contributing in supervision and editing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated/analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author easily. So, the corresponding author is responsible to the requests about the available data in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study would like to thank Bahir Dar University, Debre Tabor University, the local experts and administrators of Gondar city, and data collector participants for their commitment to supporting this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ergo Beyene

Ergo Beyene- I am a PhD student in the Faculty of Social Science and Humanities at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. Currently, I am working my dissertation on Modeling urban land use dynamics, governance and livelihoods in cities. This manuscript constitutes one of the objectives of my dissertation.

Acamyeleh Gashu Adam

Achamyeleh Gashu Adam (PhD) is an Associate Professor in Land Governance Administration at Bahir Dar University, Institute of Land Administration and a President for Ethiopian Land Administration Professionals Association. His research interests mainly in Land tenure, Informal Settlements, Land governance and Readjustment in the Changing Peri-Urban Areas and has published them in reputable international journals.

Amare Sewnet Minale

Amare Sewnet Minale (Professor) is a professor in the Faculty of Social Science and Humanities at Bahir Dar University. He is an Associate Editor of Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences. His research works covers urban land use expansion, impacts of land use/cover changes on ecosystem, modeling the impact of urbanization on land use change and related ones.

References

- Adam, A. G. (2014a). Peri-Urban Land Tenure in Ethiopia Doctoral Thesis in Real Estate Planning and Land Law.

- Adam, A. G. (2014b). Urbanization and the struggle for land in the peri-urban areas of Ethiopia. Bahir Dar University, 1–29. http://cega.berkeley.edu/assets/miscellaneous_files/22_-ABCA_Urbanization-research_paper-ABCA.pdf

- Administration, Z. T., Region, T., & Hadush, A. T. (2019). An assessment of the challenges and prospects of good urban governance practice in land administration: The Case of. Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 24(11), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2411066679

- Alemineh, Y. A. I. T. (2018). Livelihood changes, and related effects of urban expansion on urban peripheral communities: The case of Gondar city: ANRS. 45, 50–56.

- Avis, W. R. (2016). Urban governance (Topic Guide). Gsdrc, (November), 1–57.

- Badach, J., & Dymnicka, M. (2017). Concept of “Good Urban Governance” and Its Application in Sustainable Urban Planning. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 245( 8). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/245/8/082017

- Beringer, A. L., & Kaewsuk, J. (2018). Emerging livelihood vulnerabilities in an urbanizing and climate uncertain environment for the case of a secondary city in Thailand. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(5), 1452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051452

- Biswas, R., Jana, A., Arya, K., & Ramamritham, K. (2019). A good-governance framework for urban management. Journal of Urban Management, 8(2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2018.12.009

- Ermias, A., Bogaert, J., & Wogayehu, F. (2019). Analysis of city size distribution in Ethiopia: Empirical evidence from 1984 to 2012. Journal of Urban Management, 8(2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jum.2018.12.007

- Falah, N., Karimi, A., & Harandi, A. T. (2020). Urban growth modeling using cellular automata model and AHP (case study: Qazvin city). Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 6(1), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-019-00674-z

- Fikadie, M., Sahile, S., & Taa, B. (2018). Historicizing Urbanism: The socio-economic and cultural pattern of the city of Gondar, Ethiopia. Erjssh, 5(1), 103–121.

- Fitawok, M. B., Derudder, B., Minale, A. S., Van Passel, S., Adgo, E., & Nyssen, J. (2020). Modeling the impact of urbanization on land-use change in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia: An integrated cellular automata-Markov chain approach. Land, 9(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9040115

- Gashu, K. (2019). Peri-urban informal land market and its implication on land use planning in Gondar city of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Renaissance Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 6(2), 1–21.

- Gashu, K., & Gebre-Egziabher, T. (2018). Spatiotemporal trends of urban land use/land cover and green infrastructure change in two Ethiopian cities: Bahir Dar and Hawassa. Environmental Systems Research, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-018-0111-3

- Hendriks, F. (2014). Understanding good urban governance: Essentials, shifts, and values. Urban Affairs Review, 50(4), 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413511782

- Israel, G. D. (1992). Determining Sample Size. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service. Florida: Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, EDIS.

- Jones, H., Clench, B., & Harris, D. (2014) The governance of urban service delivery in developing countries. March, 1–34.

- Jones, H., Cummings, C., & Nixon, H. (2014). Services in the city: Governance and political economy in urban service delivery. Overseas Development Institute, London, (December), 1–58. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9382.pdf

- Kevin, N. H., Li, P., & Feng, J. (2016). Urban governance indicators and quality of life in Congo: Case study of Brazzaville urban governance indicators and quality of life in Congo: Case study of Brazzaville. November.

- Leulsegged, K., Gete, Z., Dawit, A., Fitsum, H., & Andreas, H. (2012). Impact of urbanization of Addis Ababa city on peri-urban environment and livelihoods. Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Ethiopian Economy, January 2015, Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA) Conference Center, Addis Ababa, 1–30.

- Lopes, H. S., Remoaldo, P. C., Ribeiro, V., & Martín-Vide, J. (2022). Pathways for adapting tourism to climate change in an urban destination – Evidences based on thermal conditions for the porto metropolitan area (Portugal). Journal of Environmental Management, 315, 115161. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2022.115161

- McCann, E. (2017). Governing urbanism: Urban governance studies 1.0, 2.0 and beyond. Urban Studies, 54(2), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016670046

- Mehryar, S., Sasson, I., & Surminski, S. (2022). Supporting urban adaptation to climate change: What role can resilience measurement tools play? Urban Climate, 41, 101047. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.UCLIM.2021.101047

- Meyer, N., & Auriacombe, C. (2019). Good urban governance and city resilience: An afrocentric approach to sustainable development. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(19), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195514

- Mezgebo, T. G. (2014). Urbanization Effects on Welfare and Income Diversification Strategies of Peri-urban Farm Households in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: An Empirical Analysis. Dissertation submitted to the National University of Ireland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, P.

- Mezgebo, T. G. (2021). Urbanization and Development: Policy Issues, Trends andProspects. In K. Mengistu & D. Getachew (Eds.), State of the Ethiopian Economy 2020/2021: Economic Development, Population Dynamics and Welfare (pp. 1–50). Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Economic Association.

- Poorahmad, A. (2018). Good urban governance in urban neighborhoods (case: Marivan city). Urban Economics and Management, 6, 497–514. http://zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/11159/2776/1/1047101017.pdf

- Prak, M. (2018). Urban Governance. Citizens Without Nations, 6, 50–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316219027.004

- Tassie Wegedie, K., & Duan, X. (2018). Determinants of peri-urban households’ livelihood strategy choices: An empirical study of Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1562508

- Taylor, P., & Halfani, M. (2004a). Urban Governance Index. UN-Habitat, (August), 1–65. papers3://publication/uuid/4B833808-137D-4037-A51F-BBE1F82E9C7F

- Taylor, P., & Halfani, M. (2004b). Urban governance index: Conceptual foundation and field test report. UN-Habitat, (August), 1–65. papers3://publication/uuid/4B833808-137D-4037-A51F-BBE1F82E9C7F

- Tegegne, E. (2015). Livelihoods and food security in the small centers of Ethiopia:The case of Durame,Wolenchiti, and Debre Sina towns. November.

- UN‐Habitat. (2016). Towards a New Urban Paradigm. 2.0, 1(1), 60. www.worldurbancampaign.org

- UNDP. (2016). Sustainable Urbanisation Strategy. UNDP’s Support to Sustainable, Inclusive and Resilient Cities in the Developing World, 1–54. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/poverty-reduction/sustainable-urbanization-strategy.html

- UN-Habitat. (2017). Urban governance, capacity and institutional development. In HABITAT policy paper 4. http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/HabitatIIIPolicyPaper4.pdf

- Ur Rehman, R. (2017). Assessment of urban governance using UN-Habitat urban governance index: A case study of tehsil municipal administrations of Punjab, Pakistan. Urban and Regional Planning, 2(4), 17. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.urp.20170204.11

- WORLD BANK GROUP. (2018). Urban Local Government Development Project. 132824.

- World Bank Group. (2019). Approach paper managing urban spatial growth: An evaluation of world bank support to land administration, planning and development. 1–40.

- Yimam, A. (2017). Urban expansion and its impact on the livelihood of peripheral farming communities: The case of kutaber town, Amhara region, ethiopia. 85.