Abstract

In recent decades there has been an increasing concern among stakeholders surrounding sport organisations regarding the implementation of governance principles and processes. It is believed that these can help them to overcome sustainability problems and to promote organisational success. This research aims to analyse the governance of Catalan sports federations (CSFs), an area that has not been analysed to date. The study, based on previous approaches in the sport management literature, proposes a model to measure three dimensions considered key to good governance in sport organisations: democracy and participation, ethics and integrity, and accountability and transparency, which are measured by quantitative performance indicators. 38 CSFs were assessed, and the results showed considerable room for improvement with respect to metrics in divergent areas of organisational governance. Six clusters were determined using the Hierarchical Ascending Classification, and statistical correlations were also found between the dimensions analysed and the size of the organisations. In addition to the interest for stakeholders in the context of Catalonia, the authors believe that this research supports recent calls for good governance in sport and can serve as a foothold for scholars to investigate other contexts.

1. Introduction

Interest in governance in sport has not only increased substantially in recent years in academia (Dowling et al., Citation2018), but there has also been growing concern from the political spheres of international and national bodies (e.g., Scheerder et al., Citation2017). Recent trends pushing towards a broader domain of sport management: increasing commercialisation, professionalism, growing government involvement, and funding, among others (Shilbury & Ferkins, Citation2011), call for more formalised governance structures, processes, and principles (McLeod, Shilbury, et al., Citation2020). For, the consequences of their omission could affect the sustainability of the current sport system (Ferkins et al., Citation2005), and of sport organisations themselves, by directly affecting their resilience, capacity building or ability to continue to provide the services demanded by a changing society.

In an increasingly complex sporting world, national (and territorial at different levels) responsibility for the key functions of promotion, management and coordination of sport remains with sport federations (Cabello et al., Citation2011). Nonetheless, despite the outstanding contribution over the years to the development of sport at all levels (Winand et al., Citation2014), recent corruption scandals (Chappelet, Citation2018; Phat et al., Citation2016), and/or failures in their management to comply with viability plans (Puga et al., Citation2020), have made the governance problems of these entities a major focus of concern. According to Dowling et al. (Citation2018), the implementation of the structures and processes of governance in the sport context should raise awareness of how sport organisations and systems are run and controlled. Indeed, as pointed out by authors such as Geeraert et al. (Citation2014), the implementation of good governance principles can help organisations to overcome corruption problems and, in general, promote organisational success.

While there is a general consensus on what constitutes good governance in sport governing bodies (Chappelet, Citation2018; Geeraert et al., Citation2014), in recent decades, a wealth of analysis and research has emerged on assessing the implementation of “good governance” in sport organisations (e.g., Australian Sport Commission, Citation2012; Chappelet, Citation2018; Council of Europe, Citation2013; Geeraert, Citation2018; Muñoz & Solanellas, Citation2023; Parent, Hoye, et al., Citation2018; Pielke et al., Citation2020). All these checklists have the dual purpose of identifying good governance criteria that can be applied to the evaluation of sport organisations, and of helping entities to identify and understand the key factors and principles involved in good governance. In particular, various scholars such as (Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2019; Henry & Lee, Citation2004; McLeod, Shilbury, et al., Citation2020) have stressed that transparency, democracy, accountability and social responsibility are considered important principles of sport governance that should be upheld.

To date, research has predominantly focused on sport organisations such as international and national federations, clubs, leagues, or organisations operating at multiple levels, however, territorial contexts have been analysed to a lesser extent (Dowling et al., Citation2018; Muñoz & Solanellas, Citation2023). The aim of this research is to expand the literature on sport governance by assessing Catalan sport federations (CSFs) on the implementation of good governance practices. A topical issue due to the society’s growing concern for better governed organisations. Specifically, the analysis focuses on aspects such as democracy and participation in sport governing bodies (SGBs), ethical and integrity aspects, as well as accountability and transparency. The importance of this paper is to generate new knowledge on the subject by examining the previously unexplored context of Catalonia. In doing so, it seeks to expand knowledge on governance in sport, as well as to provide a new approach to the analysis and discussion of aspects that deserve special attention for the improvement of the governance and structuring of Catalan sports federations, such as democratisation and participation in decision-making processes. We firmly believe that the exploration of the Catalan federative context, due to the great contribution it has on national sport at all levels, can be of great interest and act as a catalyst for future research in territorial contexts.

2. Literature review

Over the past decades, revelations of questionable governance practices in sport organisations have raised serious questions about the way in which they are governed (Stenling et al., Citation2022). Cases of corruption scandals in governing bodies (McLeod, Adams, et al., Citation2020), the need to fully understand the surrounding landscape of sport organisations (Dowling et al., Citation2018), as well as a greater strategic and organisational performance orientation (Hoye & Cuskelly, Citation2007), have brought sport governance to the forefront of public debate. As a result of this critical and reflexive process, sport organisations, and in particular federations, are under great pressure to adopt good governance practices that mitigate dishonest practices and promote sporting success (Chappelet, Citation2018). Principles that have been widely discussed in the literature, such as accountability, efficiency, effectiveness, sound financial management, anti-corruption, and transparency, among others (Geeraert et al., Citation2013).

The concept of governance has been described as vague and ambiguous. In their scoping review of governance in sport, Dowling et al. (Citation2018) identified as many as seven different definitions of governance in sport used by researchers and which differ from each other in some respects. This could lead one to think that the term has too many meanings to be useful (Rhodes, Citation1996). According to Geeraert et al. (Citation2014), definitions of governance depend on the research of the scholars or the phenomenon under study. For the categorisation of the different studies that were analysed in their work, Dowling et al. (Citation2018) adopted the three general approaches or types of governance that Henry and Lee (Citation2004) anticipated: organisational, systemic, and political. According to the authors, “organisational governance” refers to ethically based norms of managerial behaviour, or accepted norms, values, and processes in relation to the management and governance practices of sport organisations. “Systematic governance” focuses on competition, cooperation, and mutual adjustment between organisations within a given organisational system, in this case, sport. Finally, “political governance” is concerned with how governments, or any governing body in sport, “direct” or “indirect” influence the behaviour of organisations. Thus, the study of governance can be seen to consider both the structuring and manner in which organisations operate, as well as the role they play in a wider network of interconnected stakeholders subject to influence by the sport systems in which they are housed (McKeag et al., Citation2022; Renfree & Kohe, Citation2019). The present study is positioned within the domain of organisational governance. Aligning with Hoye and Cuskelly (Citation2007), understanding how sport organisations (in this case the Catalan federations) adopt the known standards of good sport governance is crucial for their continuous development, improvement, and sustainability.

As mentioned earlier, although there are some guidance documents at international and national level that serve to provide some form of training and knowledge base structures, to date, there is no universal code of good governance used by most of the actors that make up the sport sector (McLeod, Shilbury, et al., Citation2020). However, across all the codes and assessment checklists developed by researchers and practitioners, a certain consistency can be identified in terms of the general principles that are promoted. It should be noted, however, that while these principles are widely used, the details of what they imply for each of the different codes developed may vary (Parent, Hoye, et al., Citation2018). For example, as McLeod, Shilbury, et al. (Citation2020) points out, a code may consider transparency in a limited way, such as the publication of annual reports, or it may entail a broader range of requirements, including the publication of minutes of board meetings. Similarly, Parent, Hoye, et al. (Citation2018), Parent, Naraine, et al. (Citation2018) reported differences in the implementation requirements of governance codes. Depending on the demarcation of sport organisations, adherence to a governance code may be a legislative requirement, a voluntary option, or a prerequisite for receiving public funding. The authors pointed to these inconsistencies as an obstacle for researchers in the field to gain a deeper understanding of which guidelines improve governance performance. Despite these difficulties, authors such as McLeod, Shilbury, et al. (Citation2020) noted that, in practice, there is a sufficient degree of congruence between governance codes to claim that there is a general understanding of what good governance looks like in sport federations. In particular, according to Chappelet and Mrkonjic (Citation2019) the principles of transparency, accountability and democracy feature prominently in virtually all guides. Principles and guidelines that aim to ensure efficient and ethically sound governance of sports organisations (Stenling et al., Citation2022).

Geeraert (Citation2018), on the other hand, in his work on indicators and instructions for assessing good governance in national federations, indicated that, in general, there are four basic principles of good governance, which, in addition, according to authors such as Brown and Caylor (Citation2009) lead to positive organisational results and economic growth. Evidence suggests that transparency, democratic processes, internal accountability and control, and social responsibility are pervasive principles of good governance (Geeraert, Citation2018). Specifically, one could point to transparency as an effective mechanism for mitigating corruption (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2009), as well as for democratisation, as it can support stakeholders in challenging management (Mulgan, Citation2003). There is also a body of research that highlights the benefits of sport organisations having a broad orientation towards democratic and participatory processes leading to the development of policies that address stakeholder interests (Kohe & Purdy, Citation2016; McKeag et al., Citation2022; Renfree & Kohe, Citation2019). For example, by considering the representation of different constituencies in general assemblies (Geeraert et al., Citation2014), or in leadership positions, such as women (Nielsen & Huse, Citation2010; Post & Byron, Citation2015) or independent board members (Sport England, Citation2016). In terms of accountability and internal controls, a high implementation of measures related to this principle would lead to the promotion of democratic measures to monitor and control the conduct of governance, to avoid the development of concentrations of power, as well as to enhance the learning capacity and effectiveness of management (Aucoin & Heintzman, Citation2000; Bovens, Citation2007). Indeed, the authors themselves identified accountability as a cornerstone of governance, as it is the principle that informs the processes by which those who have, and exercise authority are held accountable (Aucoin & Heintzman, Citation2000). Finally, there is broad consensus that sport organisations should promote social accountability (Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2019; Renfree & Kohe, Citation2016).

The evidence presented highlights the potential value of implementing the principles of good governance, which further strengthens the justification for this study. The aim of this study is to shed light on the situation of Catalan sports federations in terms of the implementation of good governance principles such as democracy and participation, ethical and integrity aspects, as well as accountability and transparency. The following section presents the measurement model implemented for the evaluation of these governance principles and practices.

3. Methods

When investigating good governance in sport one is confronted with the lack of a set of core and homogeneous principles (Geeraert et al., Citation2014). The research addresses the assessment of three dimensions considered key to good governance of sport organisations: democracy and participation, ethics and integrity, and accountability and transparency (Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Pielke et al., 2019). To this end, the research proposes a specific measurement model that is methodologically inspired by Boateng et al. (Citation2018), Nardo and Saisana (Citation2009), and Richard et al. (Citation2009) who developed best practices for developing and validating scales and composite indicators. As a result of their contributions, we followed the next phases and steps:

(a) Items development:

Defining the measurement model that combines several conceptual dimensions and objectives. The model applied to measure the governance of sport federations includes quantitative indicators that are considered to have the potential to measure the achievement of good governance practices in each of the conceptual dimensions. An exploratory set of parameters was compiled based on a review of the available literature on good governance (e.g., Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2019; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Geeraert, Citation2018; Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2009; McLeod, Shilbury, et al., Citation2020; McKeag et al., 2023, Post & Byron, Citation2015; Sport England, Citation2016; among others).

Construction and validation of indicators. Validity of these indicators was reviewed by 15 experts in the field (practitioners and academics).

(b) Scale development:

Definition of specific procedures for normalisation. Due to indicators’ values have different measurement units, these values were normalized. Their rank was expressed as a percentage for all CSFs and then values obtained were reduced to a scale of 0 to 10.

Determination of the weighting of the indicators. It was assumed that the performance of each dimension could be calculated through the average of the performance scores of its indicators. However, it is worth noting that the proposed indicators may have a different weight for the dimension it belongs, so the relative weight of them was assessed through a questionnaire sent to 15 experts (general secretaries of the CSFs and experts who are used to work with performance indicators in the sport management field). Experts assessed the relative weight of each indicator within its dimension, using a scale from 0 (not important at all) to 5 (highest importance). The average score derived from the experts’ evaluations for each of the indicators was the reference for calculating the relative weight percentage within its dimension.

(c) Scale evaluation:

General validation of the consistency of the measurement system. Consistency of the measurement model was tested through the Cronbach alpha test.

Table shows the rationale for the inclusion of the indicators in the model implemented for the measurement of governance, as well as the details of the measurement scale and the relative weight of each indicator and dimension. Furthermore, to deepen the analysis of the relationships between the variables under study and the size of the sports federations analysed, variables that account for the size of the organisations (such as number of members, income, and total employees) were also included.

Table 1. Model implemented for measuring the governance of sport governing bodies

4. Research context

The Spanish sports system is structured as follows. The Ministry of Culture and Sport is responsible for proposing and implementing government policy on sport. The Consejo Superior de Deportes de España (CSD), an autonomous body attached to the Ministry of Culture and Sport, as the operational arm of the latter, directly exercises the powers of the General State Administration in the field of sport. Law 10/1990 of 15 October Citation1990 on Sport regulates the Spanish Sports Federations as associations of a legal-private nature, to which the exercise of public administrative functions is expressly attributed, dedicated to the promotion, management and coordination of certain sports recognised in Spanish territory (Royal Decree 1835/Citation1991). Essentially, entities which, under the tutelage of the CSD, contribute to the development of sport at all levels (Guevara et al., Citation2021). This pretext also extends to the entire national territory, adapting the organisation of the federations to that of the State in Autonomous Communities. In other words, the Spanish sports federations are made up of sports federations at the autonomous community level, which represent them and exercise public functions delegated by the respective autonomous community (see, for example, Legislative Decree 1/Citation2000, of 31 July, on the Law on Sport in Catalonia, which establishes the General Secretariat of Sport of the Generalitat de Catalunya as the body responsible for the management, planning and execution of the sports administration in Catalonia). In Spain there are 66 national federations, each with its corresponding sport modalities; however, in terms of regional organisation, not all of them have territorial representation in the 17 autonomous communities of the Spanish territory (CSD licences and clubs, 2021). In this study, we have focused on the 66 national sports federations that have territorial representation in Catalonia; an autonomous community that, with 7,763,362 inhabitants, is the second most populated region in Spain (National Institute of Statistics, Citation2021), and the first autonomous community in the Spanish ranking by number of licences and clubs (CSD licences and clubs, Citation2021).

Finally, it should be noted that both the Spanish national and regional federations take the form of voluntary associations, with a board of directors elected by the general assembly. The board of directors is the highest decision-making body and must act in the interest of its members (Hoye & Cuskelly, Citation2007). For although the general assembly, as the supreme governing body, elects the board of directors, and since it is very rare that the board’s proposals are rejected, the assembly is limited to an essential control function in terms of who gets access to formal positions of power in the sport (Stenling et al., Citation2022).

5. Data collection

Two sources of information to collect data were used:

- Secondary data: reports that the CSFs had submitted to the General Secretary of Sport of Catalonia in 2019 were analysed, as well as information that CSFs had publicly available on their websites.

- Primary data: a questionnaire was carried out. The preliminary questionnaire was evaluated and validated by 15 experts in the field, and based on their feedback, it was then modified for the pilot test. The resulting questionnaire was piloted among 10 sport organisations that did not participate in the study to ascertain length of completion and comprehensibility. Both stages helped to refine the final questionnaire to be administrated.

6. Sample

Thanks to the support of the General Secretary of Sport of Catalonia, the questionnaire was sent to the 66 CSFs. The response rate was 57.5%, which means that the final sample of the study is composed of 38 CSFs. It is also important to mention that all the CSFs participating in the study accounted for 85.76% of the total number of federation licences in Catalonia.

Through the invitation emails, organisations’ president and general secretary were informed about the research project aim. In addition, online meetings were scheduled to discuss the project in more detail, as well as to resolve possible doubts about the questionnaire. The emails contained a personalised link to the online questionnaire that allowed respondents to log in and log out while completing the data. Respondents were required to complete the questionnaire based on the practices of their organisations and were asked to provide data in reference to the year 2019, the year before the questionnaire was administered because it was the latest household year completed.

7. Data analysis

The first step was to clean the database to standardise the data collected (i.e., check for completeness, duplications, anomalies, etc.) and to correct any errors detected. The consistency of the measurement model was checked using Cronbach’s alpha test (see second column of Table ; “α”).

The good governance practices were analysed using correlational relationship and the Hierarchical Ascendant Classification (HAC) with the Ward method (Ferguson et al., Citation2000; Marlin et al., Citation2007). The HAC is a clustering method which highlight homogeneous groups of cases according to the variables by which they are assessed. The first step is to group, in the same cluster, several cases that are close to each other, then the HAC groups close cases, in accordance with the distance were chosen. To determine this distance, the Ward distance, which minimizes the intra-group variance was used to obtain contrasted groups. When every case is grouped in one cluster, the process stops. Then, the analysis of the dendrogram enables the determination of the groups of interest (the clusters that make sense).

In accordance with the clustering, thresholds were defined to highlight scores from which it was possible to assume that a CSFs has achieved a standard level of an indicator. Table and Figure , respectively, present the scores obtained for each indicator and dimensions of the 38 CSFs and the clusters obtained.

Table 2. Performance score of the 38 CSFs across the three governance dimensions analysed

The collected data was analysed with Microsoft Excel 2019 (17.0) and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 23, ©IBM. The following section presents the results of the study, which are presented in line with the research objective.

8. Findings

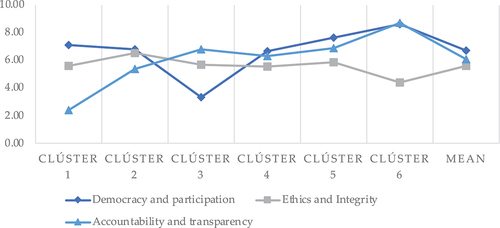

Table presents the scores obtained by the 38 CSFs on each indicator assessed, and the results of the grouping are also presented. In addition, for the reader’s ease of interpretation, Figure shows the mean scores separately for the different groups in each of the dimensions (or principles of good governance) analysed, and for the 38 CSFs (mean).

The mean score for the 38 CSFs was 6.19 (median = 6.38; SD = 0.94) out of 10, with a maximum of 8.35 (Collective 13) and a minimum of 4.10 (Individual 14).

While the scores could be discussed individually, it was possible to identify some areas where the CSFs could focus their attention if they intend to improve management practices towards good governance. Among the three dimensions of analysis, in general, the CSFs performed better on aspects of democracy and participation in decision-making processes. On the other hand, the indicators that fall under the dimension of ethics and integrity showed very low scores (where it could be highlighted that only 2 of the 38 CSFs have independent board members). Furthermore, although the average score for the accountability and transparency dimension was around 6.10, overall, the CSFs showed great room for improvement in terms of transparency (with an average score of 3.52 for the corresponding indicator).

Six groups of CSFs were determined using HAC clustering, according to their performance in good governance practices.

Cluster 1 includes those CSFs that showed score levels close to the average on the first two dimensions. It could be argued that, although they could improve on the number of committees they have (e.g., the CSFs individual 1 scored low), they seem to demonstrate a high awareness of democracy and participation in decision-making processes by having several groups represented in the general assembly. On the other hand, regarding the dimension of ethics and integrity, it should be noted that they need to demonstrate a greater concern for the representation of women in the governing bodies, as well as that they do not have independent board members. However, the scores obtained in other indicators suggest that they have control systems in place to avoid the concentration of power, as the rotation of chairpersons seems to be adequate. Finally, regarding aspects related to accountability and transparency, this seems to be the group of federations with the greatest room for improvement.

Cluster 2, although some key areas for improvement can be identified, it could be argued that, in general, they show high levels of the governance variables analysed (when compared to the average of the CSFs). However, this is the group of federations that scored the lowest on the transparency indicator (publicly available documents).

Cluster 3 includes CSFs that indicated major shortcomings in aspects of democracy and participation in their governing bodies. In particular, it is important to note that these are CSFs, many of which did not organise a general assembly for the 2018–2019 financial year. They also generally showed below-average scores on ethical and integrity aspects such as having low levels of gender equity on boards or the provision of independent members. On the contrary, they seem to be quite open to sharing the information they have, as they showed an above-average level of performance on transparency.

As can be seen from Figure , Cluster 4 is a group of CSFs that, although they show room for improvement in the different indicators analysed, they generally scored around average in the three dimensions studied. Finally, Clusters 5 and 6 are the two groups of federations that showed the best levels of performance in the good governance practices analysed (despite cluster 6 showing low levels of scores in the practices related to the ethics and integrity dimension).

8.1. Correlations analysis

With the aim of obtaining a broad perspective, the correlation analysis was carried out considering all the indicators that make up the measurement model implemented and some variables that account for the size of the organisations (Table ). Correlation coefficients were interpreted according to the criteria of Safrit and Wood (Citation1995): no correlation (score of 0–0.19), low correlation (0.20–0.39), moderate correlation (0.40–0.59), moderately high correlation (0.60–0.79), and high correlation (≥0.80). This section is presented highlighting some interesting findings.

Table 3. Correlational relationship between the variables analysed in the Catalan sports federations

In general, no correlations were found between the indicators analysed. This could indicate that, despite some trends (both positive and negative), overall, the CSFs show room for improvement in divergent areas. In other words, the results show that having good scores in, for example, the dimension of democracy and participation, is not correlated with showing the same in the dimension of, for example, ethics and integrity. Perhaps most strikingly, low, and moderate positive correlations (Pearson correlation: r) were found between the size of the organisations (members, total income, total grants, and total employees) and participation in their executive bodies (committees they have). While this might seem an expected finding, it appears that larger CSFs (more members), which also have more committees, tend to show better scores on accountability orientation and transparency (r = 0.402, p < 0.05; r = 0.426, p < 0.01). This could be related to the need for large sport organisations to address problems that are embedded in their own structural idiosyncrasies, such as the need to report to key stakeholders because of the legitimacy, impact, or pressures they may exert. This will be discussed in more depth in the next section.

9. Discussion

Following the lines proposed by authors such as Geeraert et al. (Citation2014) or Pielke et al. (Citation2020), based on the selection of indicators, this research shows the picture of Catalan sports federations in terms of key aspects of organisational governance such as democracy and participation, ethics, and integrity, as well as accountability and transparency. As can be seen from the results section, the metrics show some areas of improvement on which the governing bodies of the CSFs could focus their efforts to improve the governance of their organisations.

According to Mulgan (Citation2003) the democratic perspective is very important as “citizens”, in the case of SGBs the members and stakeholders, must be able to control those in public (or power) positions. It will therefore be paramount that governance mechanisms are put in place to ensure that those who govern act in a way that is consistent with the interests of their stakeholders (Geeraert et al., Citation2014). According to Geeraert et al. (Citation2014), the main way in which member organisations can hold their SGB accountable is through their statutory powers, i.e., members should be able to elect their chairperson and board of directors on the basis of voting rights. In this sense, it is well known that in SGBs, it is the general assembly that should be able to control the activity of the board (Hoye & Cuskelly, Citation2007) and, through at least one annual meeting, be able to criticise the government. Thus, having a general assembly that considers the different stakeholders will be an essential aspect of improving the democratic and participatory processes of SGBs’ governing bodies (Geeraert et al., Citation2013). These aspects are noteworthy in our findings, as in general, the representativeness of the collectives in the general assemblies of the CSFs is questionable. In line with other findings (i.e., Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Houlihan, Citation2005), it seems that the main stakeholders of the CSFs, athletes, coaches, referees, public administration, and sometimes clubs, are kept out of the political processes that are decisive for the rules governing their activities. Something which, according to Geeraert et al. (Citation2014) could be considered undemocratic as those at the bottom of the pyramid, i.e., clubs and athletes, are automatically subject to the rules and regulations of the governing bodies. For example, it was found that the ten CSFs in cluster 3 (26.3% of the sample) showed a low orientation towards democracy and participation in their governing bodies. Many of them did not even organise a general assembly in the 2018–2019 financial year and reported a low level of representation of the different groups. Thus, it is not unreasonable to say that there is still much room for improvement in terms of stakeholder representation in the CSFs. Generally, federations would be expected to maintain a balance of stakeholder representation (Geeraert et al., Citation2013), to ensure that programmes and initiatives are internally consistent, ensure equal opportunities and include the interest of all groups. In this regard, it should be noted that, although the Catalan Law on Sport establishes that sports federations must be made up of associations or clubs and, where appropriate, athletes, coaches, referees, or other representatives of natural persons, at no point does it establish the minimum representativeness of these key actors in the general assemblies of the federations. Thus, in line with what authors such as Parent, Hoye, et al. (Citation2018) anticipated, and in the specific case of the Catalan context, it could be corroborated that adherence to a code of governance (in terms of democracy and participation in the governing bodies of sports federations) tends to be more a voluntary option (implementation of good practice) than a legislative requirement or prerequisite for public funding (as there are no guidelines or consequences for a low representation of the different groups). However, it is important to note that this is an aspect that deserves further exploration, as while improving the representativeness of different collectives could be the first step towards a greater orientation towards democracy and participation, it could sometimes be argued that representation may not necessarily mean participation (Kihl & Schull, Citation2020).

According to authors such as McLeod et al. (Citation2021), one of the key aspects of board composition is board diversity. In fact, Adriaanse and Schofield (Citation2014), pointed out that it is an important driver of organisational and board performance. Moreover, not only for reasons of effectiveness and efficiency this diversity is notably important, but there is also a growing appreciation of the ethical need for greater diversity for reasons of social justice (Elling et al., Citation2018). The literature contains a few studies that have raised issues of equity in terms of leadership positions within SGBs, particularly with respect to gender (Henry & Lee, Citation2004). Furthermore, various public bodies have called for greater diversity within governing bodies (e.g., Council of Europe, 2012; Citation2019; Consell d’Associacions de Barcelona, Citation2019), as it has been found that the inclusion of women on boards leads to better governance as they bring a different voice to discussions and decision-making (Zelechowski & Bilimoria, Citation2004). The results of the present research indicate that, in general, there is an over-representation of male members within the governing bodies of CSFs. It is therefore important that they place female representatives in decision-making positions so that they can contribute their experiences and views. Furthermore, this gender myriad could contribute to women establishing themselves as role models for other women who would like to participate in the management of Catalan sports organisations (Geeraert et al., Citation2013). Also, in terms of board diversity, and in line with these findings, it would be advisable for CSFs to consider the possibility of incorporating independent board members. As authors such as Chappelet (Citation2018) point out, these can be useful to connect with multiple stakeholders, and as a management control mechanism for governance bodies, to avoid concentration of power and ensure that decision-making is sound, independent, and free from undue influence (Arnaut, Citation2006). However, it is noteworthy that it appears that concentration of power by chairpersons is not a major problem in the vast majority of the CSFs analysed. In general, the CSFs scored acceptably on the indicators of chairperson rotation and the provision of rules regulating a maximum number of years and terms of office as a preventive measure (Schenk, Citation2011). While overall acceptable levels of chair rotation were found, which stands out as a symptom of good governance (Geeraert et al., Citation2014), the outliers are the federations that make up cluster 5, which scored below average on this particular indicator. It is important to consider that, while it was decided in the indicator what are acceptable levels of turnover (based on previous literature, e.g., McLeod et al., Citation2021; Schenk, Citation2011), one might think that term limits could work against talent retention and expertise. However, there is a contrasting argument in the literature that term limits allow voters to selectively elect higher quality agents for a second term (Smart & Sturm, Citation2004). Thus, while CSFs show some weaknesses in terms of democracy and participation, as well as in their ethical and integrity aspects of organisational governance, it could be argued that, in general, the renewal of the core of the organisations occurs on a continuous basis.

Since SGBs are charged with caring for a public good (sport), and since they also rely heavily on the support of this sector (mainly at the financial level) (Guevara et al., Citation2021), it is to be expected that SGBs demonstrate a high degree of accountability to the community (Henry & Lee, Citation2004). However, Forster and Pope (Citation2004) and Pielke (Citation2013) pointed out that the governance of international federations is characterised by accountability deficits. Findings that can be collated in the present research on CSFs. As can be seen in Table , Catalan sports federations could strive to improve mechanisms that lead to better accountability, as few CSFs have documents such as a strategic plan, code of good governance, conflict of interest, ethics manuals or a document detailing regulations and democratic processes. It is remarkable how important the creation of these documents, together with the reflective process that accompanies them, can be for organisations. For, in addition to helping them become more accountable to their stakeholders and society at large, they could also serve as a mechanism for requiring managers to reflect on governance failures resulting from past behaviour (Bovens, Citation2007). In other words, it would allow working from the perspective of internal governance learning. Furthermore, in general, the CSFs scored even lower on transparency, something that according to authors such as Aucoin and Heintzman (Citation2000), Mulgan (Citation2003), and Bovens (Citation2007) could provide a breeding ground for issues related to corruption, concentration of power and lack of democracy and effectiveness. Therefore, and although this is something that needs to be further explored, one could reflect again on the possibility that the existence of governmental regulations, or coercive pressures (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), for CSFs to develop these documents and make them proactively available to their stakeholders, could contribute to the improvement of the governance of Catalan regional sport federations.

Finally, a note that could be highlighted from the correlation results is that, while one might expect larger organisations, with greater capacity to respond to challenges and address good governance (Pielke et al., 2019), to show higher scores on the implemented model, this was only the case for the dimension of accountability and transparency. This indicates that not only “small”, but also larger CSFs should be concerned about some aspects surrounding their governance.

10. Limitations and future lines of research

As anticipated by Dowling et al. (Citation2018), organisational governance can be a useful perspective for examining traditional sport organisations (in this case, regional sport federations). However, since this research applies a specific model for the measurement of good governance practices, and while basing it on previous literature and the opinion of experts in the field, this methodology does not escape limitations of previous implemented approaches. Nardo and Saisana (Citation2009) pointed out that these methodologies can summarise complex problems in order to support decision-making. However, they can lead to simplistic conclusions. Therefore, some limitations are outlined below to allow readers to make a fairer interpretation of the data presented.

First, it is worth noting that this is a model that comes from a purely quantitative measurement approach that attempts to quantify some aspects that it would be advisable to examine in greater depth. For example, the scoring of each indicator is not a completely objective exercise, as it depends on the evaluation criteria pre-established for each indicator. Moreover, it should be noted that the balance between indicators and dimensions could not be ensured, as the weighting decided by the experts would also have been an exercise in subjectivity. Also, note that the model applies indicators of different calibre. On the one hand, we would find dichotomous indicators that lead to scores of 0 or 10, and on the other hand, indicators that are more complex and in which it is difficult for organisations to achieve excellence (as in the case of the transparency indicator). It can therefore be argued that quantitative measurement of governance should encourage researchers in the field to contribute significant improvements.

Secondly, while these externally applied tools can help raise awareness of good governance in relation to certain measures (Pielke et al., 2019), they may have little bearing on governance practice or how these relate to each other (e.g., providing details on organisational behaviours). That is, a good score on the indicators does not mean that the organisation is necessarily well governed. It simply means that it is doing a good job in relation to the metrics. Thus, from the approach of the present research, it is assumed that each factor could not be analysed in depth and there is scope for further studies to focus on different elements of these findings. In line with authors such as Dowling et al. (Citation2018), we believe that there remains an explicit need to examine several additional specific areas, particularly within the field of organisational governance. We encourage researchers in the field to track information and other governance data, perhaps through qualitative approaches, to understand how factors relate to governance practices. To give some examples, it would be interesting if research could delve deeper into the decision-making power of different constituencies represented in assemblies, the range of meanings of board representation (possible implications of different viewpoints as in (Stenling et al., Citation2022)), or the depth of development of documents that account for greater accountability and how organisations make use of this knowledge. In fact, given that the present research is the first to shed light on a hitherto unexplored context (the governance of Catalan regional sports federations), we believe that it would be of interest to continue with this line of research, and even, for example, to open the range to comparisons between different regional federations that would allow researchers to identify differences according to the territories or the roles of the different regional federations in a broader context.

Finally, given the size of the research sample, it provides a snapshot at a given point in time and could be the first step for a longitudinal comparison in the future that would surely lead to a better understanding of the evolution of the governance of Catalan sports federations.

11. Conclusions

This research presents new insights into some aspects that have emerged as important about the governance of SGBs.

By addressing governance measurement through a specific model, this research can contribute to the body of knowledge on organisational governance in the continuous improvement of measurement systems that focus on the normative ethical principles and practices in which sport organisations should operate. Furthermore, to date, no other study has explored the context of Catalan sports federations. In doing so, this research can contribute to creating a basis on which to have a more informed debate on how the CSFs are governed. A regional context, with an important relevance in terms of the development of sport at all levels in the national territory of Spain as a whole.

While not intended to paint a complete picture of the governance problems of CSFs, our application of the proposed framework reveals a wide range of scores across organisations and considerable room for improvement with respect to the metrics. As the results indicated, the sports federations analysed should pay special attention to aspects related to the representativeness and participation of different groups in decision-making processes, gender equity in their governing bodies, as well as transparency and accountability towards their stakeholders. Of course, for some observers it is not necessary to quantify governance to understand that there are opportunities for improvement, however, this research can contribute practically by providing an external perspective to stakeholders in the Catalonia context. To know how CSFs adopt the known standards of good sport governance is crucial for their continuous development, improvement, and sustainability. Indeed, we hope that the mere exercise of having carried out the data collection with the presidents and general secretaries of the CSFs has contributed to raising awareness of how their sports organisations are managed and controlled, as well as helping them to identify the key factors and principles involved in good governance. In particular, the results will be relevant for stakeholders seeking to challenge management and decide on policies related to the governance of regional sport federations. The authors, however, are aware that even from the measurement of good governance principles, the governance of the CSFs will only improve with the engagement of stakeholders to develop a consensus on what constitutes good governance of sport governing bodies in the territory. Therefore, as noted in the previous section on future lines of research, we encourage the research community to carry out further research on sport governance in specific territories, so that knowledge can be extended elsewhere and contribute to the exchange of best practice within the sport sector.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia for providing the necessary support for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joshua Muñoz

Joshua is an assistant professor and researcher at INEFC. He holds a master’s degree in Sport Management and is currently a PhD student at INEFC, University of Barcelona. His lines of research have focused on the sports policies and sport events ticketing.

Francesc Solanellas

Francesc is professor of Sport Management at INEFC. He holds a PhD in Education Sciences from the University of Barcelona. His lines of research have focused on the sustainability and legacy of sport events, sport policies, and citizens' sport habits.

Miguel Crespo

Miguel is responsible for participation and training in the Integrity and Development Department of the ITF. He holds a PhD in Law and a PhD in Psychology from the University of Valencia.

Geoffery Z. Kohe

Geoffery is professor at University of Kent. He holds a PhD from the University of Otago. His research strengths cover socio-cultural, historical, and political aspects of sport, the Olympic movement and sport legacies.

References

- Adriaanse, J., & Schofield, T. (2014). The impact of gender quotas on gender equality in sport governance. Journal of Sport Management, 28(5), 485–20. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0108

- Arnaut, J. (2006). Independent European sport review. UEFA. Available online: http://eose.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/independant_european_sports_review1.pdf. (accessed on 12 January 2023)

- Aucoin, P., & Heintzman, R. (2000). The dialectics of accountability for performance in public management reform. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 66(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852300661005

- Australian Sports Commission. (2012). Sports Governance Principles. Sports Governance Principles, March. Available online: https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/857204/ASC_Governance_Principles.pdf. (accessed on 10 January 2023)

- Boateng, G., Neilands, T., Frongillo, E., Melgar-Quiñonez, H., & Young, S. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(June), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x

- Brown, L., & Caylor, M. (2009). Corporate governance and firm operating performance. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 32(2), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-007-0082-3

- Cabello, D., Rivera, E., Trigueros, C., & Pérez, I. (2011). Análisis del modelo del deporte federado español del siglo XXI. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte, 11(44), 690–707. Available online, http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=54222204003. (accessed on 10 January 2023.

- Chappelet, J. L. (2018). Beyond governance: The need to improve the regulation of interna- tional sport. Sport in Society, 21(5), 724–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1401355

- Chappelet, J. L., & Mrkonjic, M. (2019). Assessing sport governance principles and indicators. In Research handbook on sport governance (pp. 10–28). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786434821.00008

- Consell de Barcelona. (2019). Equitat de Gènere a Les Entitats i Associacions de Barcelona Gener 2019, 1–11. Available online: https://plataformavoluntariado.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2018-12_generebcn_cab_v3.pdf. (accessed on 10 January 2023)

- Council of Europe. (2013). 2012 highlights. Available online: https://book.coe.int/en/activities-annual-report/5679-pdf-council-of-europe-2012-highlights.html. (accessed on 10 January 2023)

- Council of Europe. (2019). All in: Towards gender balance in sport. Available online: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/gender-equality-in-sport/home. (accessed on 15 January 2023)

- CSD. (2021). Licences and clubs 2021. Available online: http://www.csd.gob.es/en/federations-and-associations/spanish-sports-federations/licences. (accessed on 10 January 2023)

- Decret Lesgislatiu 1/2000, de 31 de juliol, pel qual s’aprova el Text únic de la Llei de l’esport. Availbale online: https://portaljuridic.gencat.cat/eli/es-ct/dlg/2000/07/31/1. (accessed on 10 January. 2023b)

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dowling, M., Leopkey, B., & Smith, L. (2018). Governance in sport: A scoping review. Journal of Sport Management, 32(5), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0032

- Elling, A., Hovden, J., & Knoppers, A. (Eds.), (2018). Gender diversity in European sport governance. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315115061

- Ferguson, T., Deephouse, D., & Ferguson, W. (2000). Do strategic groups differ in reputation? Strategic Management Journal, 21(12), 1195–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200012)21:12<1195:AID-SMJ138>3.0.CO;2-R

- Ferkins, L., Shilbury, D., & McDonald, G. (2005). The role of the Board in building strategic capability: Towards an integrated model of sport governance research. Sport Management Review, 8(3), 195–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(05)70039-5

- Forster, J., & Pope, N. (2004). The political economy of global sports organisations. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203505915

- Geeraert, A. (2018). National Sports Governance Observer. Indicators and instructions for assessing good governance in national sports federations. Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies. Available online: https://www.dshs-koeln.de/fileadmin/redaktion/user_upload/nsgo-indicators-and-instructions.pdf. (accessed on 15 January 2023)

- Geeraert, A., Alm, J., & Groll, M. (2014). Good governance in international sport organiza tions: An analysis of the 35 Olympic sport governing bodies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2013.825874

- Geeraert, A., Groll, M., & Alm, J. (2013). Good governance in International Non-Governmental Sports Organisations: An empirical study on accountability, participation and executive body members in Sport Governing Bodies. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1406742/FULLTEXT01.pdf. (accessed on 15 January 2023)

- Guevara, J. C., Martín, E., & Arcas, M. (2021). Financial Sustainability and earnings Management in the Spanish sports federations: A multi-Theoretical approach. Sustainability, 13(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042099

- Henry, I., & Lee, P. C. (2004). Governance and ethics in sport. In S. Chadwick & J. Beech (Eds.), Harlow, england (pp. 25–42). Pearson Education.

- Houlihan, B. (2005). Public sector sport policy: Developing a framework for analysis. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 40(2), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690205057193

- Hoye, R., & Cuskelly, G. (2007). Sport governance. Routledge.

- Kihl, L., & Schull, V. (2020). Understanding the meaning of representation in a deliberative democratic governance system. Journal of Sport Management, 34(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0056

- Kohe, G. Z., & Purdy, L. G. (2016). In protection of whose “wellbeing?” considerations of “clauses and a/effects” in athlete contracts. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 40(3), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516633269

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2009). Is transparency the key to reducing corruption in resource-rich countries?. World Development, 37(3), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.07.002

- Ley 10/1990, de 15 de octubre, del Deporte. «BOE» núm. 249, de 17/10/1990. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1990/10/15/10/con. (accessed on 10 January. 2023a)

- Marlin, D., Ketchen, D., & Lamont, B. (2007). Equifinality and the strategic groups performance relationship. Journal of Managerial Issues, 19(2), 208–233. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604564

- McKeag, J., McLeod, J., Star, S., Altukhov, S., Yuan, G., & Shilbury, D. (2022). Board composition in national sport federations: An examination of BRICS countries. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2022.2155982

- McLeod, J., Adams, A., & Sang, K. (2020). Ethical strategists in Scottish football: The role of social capital in stakeholder engagement. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 14(3), 298–316. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBGE.2020.108085

- McLeod, J., Shilbury, D., & Zeimers, G. (2020). An institutional framework for governance convergence in sport: The case of India. Journal of Sport Management, 35(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2020-0035

- McLeod, J., Star, S., & Shilbury, D. (2021). Board composition in national sport federations: A cross-country comparative analysis of diversity and board size. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2021.1970614

- Mulgan, R. (2003). Holding power to account: Accountability in modern democracies. Springer.

- Muñoz, J., & Solanellas, F. (2023). Measurement of organizational performance in national sport governing bodies domains: A scoping review. Management Review Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00325-9

- Nardo, M., & Saisana, M. (2009). Handbook on constructing composite indicators: Putting theory into practice (pp. 1–16). Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen.

- National Institute of Statistics. (2021). Resident population by date, sex and age. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=31304. (accessed on 12 December 2022)

- Nielsen, S., & Huse, M. (2010). The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corporate Governance an International Review, 18(2), 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2010.00784.x

- Parent, M., Hoye, R., & Girginov, V. (2018). The impact of governance principles on sport organisations’ governance practices and performance: A systematic review. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1503578

- Parent, M., Naraine, M., & Hoye, R. (2018). A new era for governance structures and processes in Canadian national sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0037

- Phat, T. H., Birt, J., Turner, M. J., & Fenech, J. P. (2016). Sporting clubs and scandals–Lessons in governance. Sport Management Review, 19(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.08.003

- Phat, T., Birt, J., Turner, M., & Fenech, J. (2016). Sporting clubs and scandals–Lessons in governance. Sport Management Review, 19(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.08.003

- Pielke, R. (2013). How can FIFA be held accountable? Sport Management Review, 16(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.12.007

- Pielke, R., Jr., Harris, S., Adler, J., Sutherland, S., Houser, R., & McCabe, J. (2020). An evaluation of good governance in US Olympic sport National Governing Bodies. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(4), 480–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1632913

- Post, C., & Byron, K. (2015). Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1546–1571. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0319

- Puga-González, E., España-Estévez, E., Torres-Luque, G., & Cabello-Manrique, D. (2020). The effect of the crisis on the economic federative situation and evolution of sports results in Spain. Journal of Human Sport & Exercise, 17(2), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.14198/JHSE.2022.172.13

- Real Decreto 1835/1991, de 20 de diciembre, sobre Federaciones deportivas españolas. «BOE» núm, 312, de Available online, 3010. 12January. 1991. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1991/12/20/1835/con. (accessed on. 2023

- Renfree, G., & Kohe, G. Z. (2019). Running the club for love: Challenges for identity, accountability and governance relationships. European Journal for Sport and Society, 16(3), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2019.1623987

- Rhodes, R. (1996). The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44(4), 652–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb01747.x

- Richard, P., Devinney, T., Yip, G., & Johnson, G. (2009). Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practice. Journal of Management, 35(3), 718–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308330560

- Safrit, M., & Wood, T. (1995). Introduction to measurement in physical education and exercise science (3rd Edn ed.). Times Mirrow/Mosby.

- Scheerder, A., & Claes, E. (2017). Sport policy systems and sport federations. A cross-national perspective (pp. 263–282). PalgraveMacmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60222-0_1

- Schenk, S. (2011). Safe hands: Building integrity and transparency at FIFA. Transparency International.

- Shilbury, D., & Ferkins, L. (2011). Professionalisation, sport governance and strategic capa- bility. Managing Leisure, 16(2), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2011.559090

- Smart, M., & Sturm, D. (2004). Term limits and electoral accountability. Available at SSRN 519122. Discussion paper No 770.

- Sport England. (2016). A code for sport governance. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/funds-and-campaigns/code-sports-governance. (accessed on 15 January 2023)

- Stenling, C., Fahlén, J., Strittmatter, A., & Skille, E. (2022). The meaning of democracy in an era of good governance: Views of representation and their implications for board composition. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 58(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902221088127

- Winand, M., Vos, S., Claessens, M., Thibaut, E., & Scheerder, J. (2014). A unified model of non-profit sport organizations performance: Perspectives from the literature. Managing Leisure, 19(2), 121–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2013.859460

- Zelechowski, D., & Bilimoria, D. (2004). Characteristics of women and men corporate inside directors in the US. Corporate Governance an International Review, 12(3), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2004.00374.x