Abstract

This original research article investigates the impacts of gender roles on women’s urban poverty in Assosa city, Benishangul Gumuz National Regional State, Ethiopia. It emphasizes how gender roles impacted women’s educational attainment and social mobility, healthy or unhealthy behavior and lifestyles, unemployment, and benefits from the infrastructural services available. A qualitative research design was employed to conduct the study with semi-structured interviews among women who engaged in Micro and Small Enterprises (n = 30), key informant interviews with experts working in government sectors (n = 15), and 4 focus group discussions (n = 32) among women who were selected based on their experiences in the micro and small enterprises in the study area. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data generated aiming at understanding the different views of the study participants related to the revelation and expression of gender roles in women’s urban poverty. In the context of this study, revelation implies the state of being exposed to gendered roles while expression indicates the reactions of victims to exposure. This study has policy implications informing interventions at all levels toward mitigating the impacts of gender roles on women’s urban poverty.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Gender role is the product of interactions between individuals and their environments. These environments affected women to encounter several challenges of urban poverty. The Ethiopian government has encouraged women to work in micro and small businesses to overcome these obstacles. Although the government promotes women’s participation in various businesses, little is known about the state of knowledge for the impact of gender roles on urban poverty in Ethiopia, and the small body of literature available has numerous gaps that warrant further investigations. First, most research has been directed toward exploring the impact of gender roles on education but did not examine the gender disparities in asset ownership that restricted the economic opportunities of women who participated in micro and small enterprises (MSEs). Second, while some research emphasized the impact of gender roles on healthy lifestyles in Sub-Saharan countries, there is a scarcity of research conducted on the attitudes and behaviors of government and people in the public arena that curtailed the health opportunities of women who actively participated in the MSEs. Therefore, to fill the above gaps, the current study aims to explore how gender role impacts women’s educational attainment, to what extent the role of gender determines women’s healthy or unhealthy behaviors and lifestyles, how gender differences affect women’s unemployment, and how gender role matters in women’s infrastructure who actively engage in MSEs in Assosa city, Ethiopia

1. Introduction

The concept of gender roles refers to the activities ascribed to women and men based on their perceived differences (Chant & McIlwaine, Citation2013, Citation2016), and the manner and methods through which this is achieved vary significantly in different contexts around the world. Much of the Western literature on gender role centers on the gender models in which gender role has been shaped by change over time and space but throughout the Global South, gender role is a learned behavior acquired from the social environment and is influenced by social, cultural and environmental factors characterizing a certain society, community or historical period (Khalid, Citation2011; Naz et al., Citation2022). This is the case in Ethiopia where gender role is the product of interactions between individuals and their environments (see Drucza et al., Citation2019), producing a wide array of problems that affect the well-being of women in a given community (Blackstone, Citation2003).

The empirical studies available and a growing body of research, which emphasize the relationships between gender roles and problems, detail the links between women and poverty (Hameed, 2014; May 2014). This is because women are disproportionately represented in less desirable professions and encounter several challenges in the formal economy to produce, distribute, consume, and exchange goods and services (Chant & McIlwaine, Citation2013). Alternately, the Ethiopian government has encouraged women to work in micro and small businesses to overcome these obstacles, and yet their involvement has drastically increased over the years (Alene Citation2020; Tadesse et al., Citation2021).

According to Haile (Citation2022), a micro-enterprise is defined as an enterprise that operates with 5 people as members including the owner and/or their total asset is not exceeding $5000 US for the industrial sector, and the values of the total asset are not exceeding $2,500 for the service sector. In addition, this agency is defined as a small enterprise that hires 6–30 employees with a total asset $5001 − $75, 000 US for the industry sector, and $2,500–20, 000 US for service sectors. At this point, the evidence shows that women are actively engaged in micro-enterprises as they are active in retail and distribution services, while men take part in small enterprises (Tadesse, Citation2021). The restrictions of job opportunities that occurred between men and women in a wide range of economic activities have expedited urban poverty in the country, (Birhanu, 2011) which is characterized by inadequacy or lack of productive means to fulfill basic needs such as food, water, shelter, education, health, and nutrition (Chant & McIlwaine, Citation2016; Tacoli, Citation2012).

This study draws on the theory of marginality and the theory of dependency. The theory of marginality, according to Aceska et al. (Citation2019), postulates that urban settings and women’s destitution or poverty, are socialized through generations. This theoretical approach underpins that women have more traditional cultures such as patriarchal attitudes than men do, and are entangled in vicious cycles of unhealthy lifestyles, unemployment, illiteracy, and poverty. The fact that women are viewed as “parasitic” by government officials in developing countries due to the misunderstanding that they are less hard workers, live less market-oriented lifestyles and lack entrepreneurial spirit also makes them the most unfortunate social group who live in poverty (Surbaki, 1984). The theory further posits that administrators and officials view women as lacking the ability to end all forms of poverty on their own. This relates to the argument that women who engage in micro and small enterprises often lack participation in the development or political life of the cities they dwell in and at the national level of engagement (Bradley & Boles, Citation2003). In many cases, women tend to radically behave in the sense of being easily influenced by gender stereotypes (Bruni et al., Citation2004). Maintaining this concept, Eshetu and Zeleke (Citation2008) argue that women engaging in micro and small enterprises lack social cohesion and experience external isolation, which can be manifested in the inability to integrate into city life that might reinforce systematic discrimination in the city. In line with this argument, Jagero and Kushoka (Citation2011) contend that women’s lack of cohesion and integration failure in cities can be associated with their inability to make use of existing city bodies such as institutions, offices, and other urban service institutions. In this context, the theory of marginality is relevant to explain the vulnerability of women and the need for protecting them from the negative impacts of gender roles.

The theory of dependency also supports the basic premises of the theory of marginality stating that the exposure of women to poverty is structural in explaining the symptoms of the growth of women’s poor settlements or slums in urban areas and the life experiences of being illiterate, unhealthy, and unemployed (Kim & England, Citation1993; Wekerle, Citation1980). Kim, England and Wekerle maintain that the phenomenon of women’s poor urban settlements is a form of capitalist penetration in need of investment in lands women engage in micro and small enterprises possess, which are structurally lame when compared to the lands that men, private sectors, and residence areas occupy (see also Dowuona-Hammond, Citation2007). Several studies further indicate that the practice of capitalist penetration in the name of investment in lands women have possessed running their enterprises resulted over the years in the emergence of minority capitalist elites while exacerbating women’s poverty, unemployment, and vulnerability to various other social complexities and health problems in urban areas (DeMartino & Barbato, Citation2003; Fielden et al., Citation2003). Arguably, the theory of marginality and the theory of dependency are complementary and conceptually linked because these approaches support that gender role adversely impacts women’s educational achievements, health behavior and lifestyles, employment situations, and use of infrastructure.

Understanding that women encounter several challenges of urban poverty, too little is known about the state of knowledge for the impact of gender roles on urban poverty in Ethiopia, and the small body of literature available has numerous gaps that warrant further investigations. First, most research has been directed toward exploring the impact of gender roles on education (Du et al., Citation2021; Mostert & Gulseven, Citation2019), but did not examine the gender disparities in asset ownership that restricted the economic opportunities of women who participated in MSEs. Second, while some research emphasized the impact of gender roles on healthy lifestyles in Sub-Saharan countries (Adjiwanou & LeGrand, Citation2014; Beia et al., Citation2021), there is a scarcity of research conducted on the attitudes and behaviors of government and people in the public arena that curtailed the health opportunities of women who actively participated in the MSEs.

Third, a significant number of researchers paid due attention to the impact of gender roles on education and healthcare jobs (Uneke & Uneck, Citation2021) while undermining women’s productive role that is often stifled due to socially ascribed gender roles against hiring women. This not only triggers the increasing women’s unemployment rate but also hampers economic growth. Lastly, a shred of literature has focused on the extent to which gender role has a significant impact on women’s labor force (Tzvetkova & Ortiz-Ospina, Citation2017; Qing, Citation2017; Moscarelli, Citation2021). These studies, however, emphasized less on how gender roles impacted infrastructure in urban areas. In addition, women’s lack of collateral, seclusion from the public arena and government, and lack of utilities limited their access to market and financial institutions, education, and utilization of healthcare services. Furthermore, variables that have been identified in previous research as important factors for predicting the relationship of gender roles to education, health, unemployment, and infrastructure facilities, were rarely evaluated simultaneously for women who engaged in the MSEs, as the integration of gender issues into micro and small enterprise development is essential for pro-poor growth and sustainable development in urban areas. Against this backdrop, the current study aims to explore how gender role impacts women’s educational attainment, to what extent the role of gender determines women’s healthy or unhealthy behaviors and lifestyles, how gender differences affect women’s unemployment, and how gender role matters in women’s infrastructure who actively engage in MSEs in Assosa city, Ethiopia.

2. Method

2.1. Study design and method

The present study was conducted from September 2020 to September 2021 using a cross-sectional study design (Sedgwick, Citation2014) to explore the extent to which the impact of gender roles in urban areas was evident concerning women’s urban poverty. In undertaking this study, a qualitative research method was employed as it allows researchers to investigate problems that cannot be quantified in understanding gendered roles and experiences, and a variety of definitions of poverty in urban areas. Moreover, this approach is appropriate to provide an in-depth understanding of the ways men and women understand, act and manage their day-to-day situations in urban poverty since the probability of being a poor woman is not distributed randomly among the population, but rather a gender-made problem. Further, a qualitative research method allows researchers to obtain specific information about the values, opinions, behaviors, and social settings of the population being studied (Creswell, Citation2014).

The specific qualitative research design employed in this study is phenomenological given that the focus of the research is on the lived experiences of the target groups of the study (Kvale, Citation1996; Maypole & Davies, Citation2001; Mertens, Citation2005), women involved in Micro and Small Enterprises in Assosa city, the study area. Phenomenological research helps to understand the social phenomena from the perspectives of informants involved because it maintains the proposition that realities emerge from “intangible mental constructions, socially and experientially based, local and specific in nature” (Cohen & Lawrence, Citation1994, p. 36). The sampling technique this study employed is purposive, which allows researchers for determining the purpose that the informants can serve (Creswell, Citation2014) in the study.

3. Study location

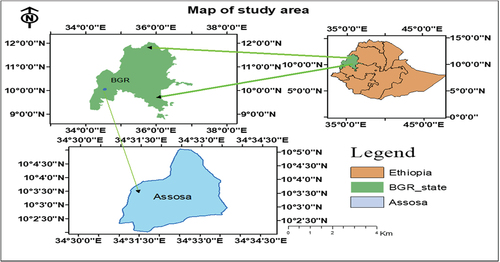

This study was conducted in Assosa city, the administrative seat of Benishangul Gumuz National Regional State, which was established in 1991. As shown in Figure (see page 30), the city has 4 urban Kebeles (local administrations) with a total area of approximately 14.58 square km and is located 687 km west of Addis Ababa (Assosa City Bureau of Finance and Development, 2020). According to CSA (2013) projection, Assosa city has a total population of about 37,365 residents of whom 19,232 are males and 18,133 are females. Based on the reports of the Micro and Small Scale Entrepreneurs (MSSE) agency (2020), there were a total of 491 enterprises operating in the Assosa zone. Therefore, the current research focused on women who joined a wide range of MSEs in the study area aiming at exploring the knowledge for, attitude towards, and practices of the community pertaining to the impacts of gender roles in women’s participation in MSEs to reduce urban poverty.

4. Procedure and participants

Participants of the study included women who engaged in the MSEs, especially in the small-scale industry, construction, urban agriculture, and service sectors such as hotel, guardianship, and hygiene; and key informant experts from relevant government offices in Assosa city. The target population was approached for the study for the reason that all sections of the community have had equal chances to be exposed to the impact of gender roles on education (Mostert & Gulseven, Citation2019), health (Beia et al., Citation2021), infrastructure, and employment (Tacoli, Citation2012). Purposive sampling, which allows for conveying appropriate information on the issues under consideration (Ahuja, Citation2010), was used to select participants for the study. This sampling technique is considered a planned choice of samples, and it applies to small samples from a population that is well understood (Bernard, Citation2006). Women employees who engaged in the MSEs, but faced challenges in getting access to workspaces were considered as groups exposed to urban poverty as defined by international organizations such as the World Bank. According to Baker (Citation2008) , urban poverty refers to a set of economic and social difficulties in cities resulting from a combination of processes such as lack of educational access, healthcare service utilization, and infrastructure, processes of social fragmentation, increase in unemployment, poor living conditions, and a growing sense of individualism.

In exploring the impact of gender roles on urban poverty and dealing with it, this study indicates that the following core elements are highly important. These include education, which is the process of facilitating learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, morals, beliefs, and habits through educational sectors; access to healthcare services, which measures the degree to which the use of services has been described by the target population of the study for preventing and curing health problems, promoting maintenance of health and well-being, or obtaining information about one’s health status and prognosis (); and infrastructure, which refers to capital goods in the form of transportation, road accessibility, electricity, telecom services, energy and water provision, sewerage facilities, garbage disposal, air purification, building and housing stock, facilities for administrative purposes and the conservation of natural resourcces. In addition, employment, which is an opportunity to find work or have a paid job is critical in urban settings.

The methods of data collection employed to conduct the study subsume semi-structured interviews with women who engaged in MSEs; key informant interviews with experts working in government entities; and Focus Group Discussions with selected participant women focusing on the research objectives. Before the data collection, the informants who were believed to have good knowledge of the subject under discussion were identified owing to their lived experience related to gender roles and urban poverty. Ethical consideration was maintained in that informed consent was obtained from the informants upon explaining the purpose of the study. Participants were assured that they would be protected from physical and psychological harm while involved as participants in the study. In addition, the informants were told that their participation in the study would be voluntary with their rights respected to ask questions, not to answer particular questions, that they consider unworthy, or withdraw from participation in the study. The participants were also assured that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential only serving the purpose of the study.

The study involved 30 informant women for the semi-structured interviews who were selected purposely. The sample characteristics of the study population indicate that the informant women generally fall within the age category; of 24–39 while the education status of the women implies that 6 completed high school, 11 were dropouts from elementary school, and 13 were uneducated. The interviews focused on examining the impacts of gender roles on urban poverty. Each semi-structured interview lasted nearly forty minutes and was recorded in a voice recorder. The key informant interviews were conducted among 15 informant experts who were purposely recruited from government offices including Women and Children Affairs, Education, Health, Micro and Small Enterprises, Trade and Transport, Civil Service, Communications department, Complaint Office, Water and Sanitation, Telecommunications, Electric Power, Administration office, Women’s Association, and women’s focal persons in the city. The key informants were selected based on their knowledge of the subject under discussion aiming as Bryman (2004, 2009) notes, at providing a diverse set of perspectives. Similarly, the key informant interviews explored how gender roles impacted women’s urban poverty and lasted for 35–40 minutes each.

In employing the Focus Group Discussions to generate the data, a total of four (4) FGDs were organized among 32 participant women who were selected and categorized into groups based on their experiences in the micro and small enterprises. Each focus group consisted of 8 members, a popular size for discussion (Ahuja, Citation2010) with a homogenous structure, and lasted for an hour. The FGDs were organized along the types of occupations the participants engaged in such as street vendors, hotel and hygiene services, commerce and construction, and shopping. The FGDs, which according to Bernard (Citation2000) and Creswell (Citation2009) help researchers capture the participants’ perspectives, inquired into individual opinions and practices on gender roles and urban poverty. Amharic (the working language of Ethiopia) was used to prepare the interview and FGD guides and conduct the interviews and discussions with the study participants. The researchers had a facilitation role during the FGDs with little intervention to change the participants’ views or opinions.

5. Data analysis

The qualitative data were analyzed using inductive subject analysis. This is the process of coding data without trying to adapt it to existing coding frameworks (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) to identify key themes. In four major phases, we analyzed and interpreted participants’ perspectives, feelings, and experiences regarding the impact of gender roles on urban poverty. The first step was the familiarization phase. This phase helped the researchers become familiar with the data collected. At this stage, the audio recordings are often necessary to perform some form of transcription, which will allow the researchers to work with the data by going through all data from the entire interview and start taking notes, and this is when the researchers mark preliminary ideas for codes that can describe the content. As a result, the audio recording was first transcribed verbatim (converted to text data) and translated from Amharic into English. The entire English translation of the Amharic response (excerpt) has been carefully edited and used in this study. In this first step of data analysis, all authors read the interview transcript to rule out inconsistent statements by the informants. The authors also identified the redundancy of information obtained from each informant. And finally, the raw data was compressed to a manageable size to explain the participants’ perspectives and experience with the impact of gender roles on urban poverty.

The second stage was the generation of the initial code. At this stage, the analysis included detailed reading and rereading of the transcript and generation of description categories. The study reflects the process of organizing codes and comparing them in terms of similarities and differences. In this phase, topics were categorized so that groups of codes follow patterns and repeat in the data in some situations. After that, tightly categorized subtopics were determined that arose from the coding and classification process. The third phase was searching for themes. After the data was collected and coded according to similar and different ideas, only themes approved by the researchers were involved. These issues were further analyzed and broken down into several major results or themes: revelation and expression.

Revelation-related issues arose primarily from responses from women who engaged in MSEs and identified the impact of gender roles on education, access to healthcare services, unemployment, and infrastructure. On the other hand, the issue of expressiveness was mainly raised by major informants who were aware of the positive efforts of communities and organizations. During the data analysis, several themes and sub-themes were recognized. Themes and categories were highlighted by selected “units of meaning” (participant citations) and reflected concerning research objectives to clarify the meaning of participants’ responses. In phase Four, the themes were reviewed. The study began with a review and confirmation process to ensure relative certainty about the main and subthemes developed. In the final phase, the researchers developed the story with word frequency and recorded all the data to quantify the number of informants or participants who supported each theme.

6. Results

The results of this study indicate that women were vulnerable and in need of protection from the adverse impacts of gender roles and risks associated with engagement in the MSEs in Ethiopia in general and Assosa city in particular. The study also reveals that gender role is one of the major obstacles hindering women’s educational access, healthcare affordability, equal participation in the economic system, and infrastructural development in the study area.

7. The impact of gender roles on education

Revelation: Fence off. It is indicated in the findings of this study that family members wanted women/girls to stay at home for reproductive roles. According to the informant women, if women/girls spend much of their time in the domestic sphere carrying out household chores, they tend to perform very well at school. This relates to the fact that females’ excellence in the world of education or work in the public sphere starts well in the household where they carry out various routine household tasks including the socialization of children. Supporting this argument, one of the informant women said, “A woman’s worth cannot be measured by her academic ability, but rather by her special skills in performing household tasks. Considering this as a reality, a woman often chooses to excel in the domestic sphere than equally doing well at school.” Supporting this argument, a woman FGD participant narrated:

I assumed that most women’s success in education can be determined by the degree of their engagement in social activities. If women establish strong ties with the community through engagement in productive roles, they will enjoy the opportunities for educational success at schools. This is attributed to their interactions with community members, which allow for knowledge acquisition. Despite this, many women would decide to withdraw from secondary education for various reasons including marriage at an early age.

Further strengthening the idea that girls’ engagement in reproductive roles would form the basis for performing better at school, an interviewed woman argued, “most members of the local community perceive that the low academic performance of girls results from their poor engagement in the household activities. This is because a girl’s success in performing household chores indicates that she would become an excellent achiever at school.” Contrary to these assumptions, however, it should be emphasized that gender roles negatively impact girls’ academic success because girls spend much of their time carrying out household activities than equally paying attention to their schooling. In particular, many girls tend not to complete their secondary education for reasons related to increasing engagement in reproductive labor.

Revelation and expression: Gender stereotype. Nearly all participants of this study maintained that gender roles affect women in acquiring knowledge and skills that can be obtained while performing productive roles in the public sphere. In other words, girls’ increasing engagement in reproductive labor would confine them to the domestic sphere. This in turn would adversely impact their access to education. It can, therefore, be argued that the standards of femininity have negative consequences for girls’ education and personality development. In line with this, one of the informant women recounted:

My parents often insisted that I should get married as the worth of a female is best measured in feminine values such as raising children and managing the household. Unable to cope with my parents’ pressure, I just withdrew from grade 6, got married, and bore children. But, I had few opportunities for continuing my education after marriage, and my husband either had no interest in helping me realize my educational ends.

Debating the lack of opportunities for educational access in Assosa city, some of the informant women described that girls are not privileged as boys to go to school. Several girls living in the town who came from the surrounding rural areas are illiterate. The prevailing tradition also forces girls to get married at an early age than going to school. This portrays that the local people’s attitude towards girls’ education is generally unfavorable. Despite this, the informants stressed that the local culture provides women and girls the privileges of protection from physical attacks or any other forms of abuse. This can be understood in the sense that moral values for girls’ protection are given due consideration by the local populace.

Revelation and expression: Traditional gender role orientation. Many of the interviewed women believed that men and women have contrasting differences including attitudes toward the meaning of life. The informants contended that each sex has a natural affinity to particular behaviors. In particular, men’s perceptions of females had long been a roadblock to women’s and girls’ education in the town. Emphasizing how many women perceive themselves, one of the informants women noted that females are born for males since they were created from men’s left ribs in a religious sense. Strengthening this demeaning concept, a discussant woman stated:

God created women intending to make them serve men. Whether women are educated or not, their contribution to development is insignificant. To be honest, several educated women would enjoy few opportunities for high-paying jobs beyond employment in the service sector where payment is not commensurate with the work done.

In due course of time, however, there has been a transformation in women’s attitudes and perceptions as they have begun to question their inequality in educational access and household decision-making. Put differently, husbands are no longer able to exercise their unlimited power on deciding the fate of their wives. The informant women’s reflections on the traditional gender role orientation depict that revelation and expression were evident. In the case of revelation, women who engaged in MSEs experienced low-level educational attainment in Assosa town as a result of societal norms prescribing what types of behaviors are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for women based on their sex. The consequent expression involved gender stereotypes, men’s domination, women’s subordination, traditional gender role orientation, and socio-cultural influences. It can, therefore, be argued that the revelation of gender roles enormously affected women’s school retention thereby depicting less performance in education.

8. Gender role and healthcare service utilization

Expression and revelation: unhealthy lifestyle. All participants of the study argued that women who engaged in MSEs were systematically discriminated against in obtaining equal healthcare services. The FGD participant women maintained that husbands would visit government hospitals or healthcare centers for treatment when they get sick while they deny the rights of their wives to get medical treatment forcing them instead to visit herbalists. The accounts provided below further complemented the idea that husbands often violated the rights of their wives in accessing modern therapy. An informant woman thus contended:

It has now been four years since I came to Assosa city. When I get sick, I don’t visit hospitals or health centers for healthcare, but prefer to treat myself through traditional means. This is because my husband is not willing to pay for my treatment in hospitals or healthcare centers.

Likewise, another informant woman narrated:

I spend more than 18 hours a day for work in the household. I cook food, wash clothes, provide care for my children, clean the house, and sometimes grind grains when there is no power supply. Due to the routine household tasks I always carry out, I have now developed back pain. However, I did not yet visit healthcare facilities for fear my husband should know about my health problems.

Most of the study participants women also shared the narrations provided and added that husbands often restricted the rights of their wives to eat properly three times a day. Some even considered their wives who ate like them properly as irresponsible women. As part of the solution to escape hunger at home, many wives thus preferred their husbands to stay outside the home so that they would eat their fill. Moreover, many low-income women in Assosa city are exposed to rape, abortions, extreme anxiety, trauma, and asthma. The problems are complex because the legal entities do not provide women with protection and economic security. Arguably, the women’s lower living conditions coupled with the adverse impacts of gender roles and unequal household relations interact with the unfavorable social environment hindering the women’s access to healthcare services.

In line with this argument, it can also be noted that gender inequalities in power and well-being result from asymmetrical intra-family resource allocation and distribution. This is attributed to the prevailing gender ideology combined with institutional and cultural factors, which tend to legitimize patriarchal relations in households reinforcing female stereotypes. The case in point is husbands’ violation of their wives’ rights to get adequate food and access modern healthcare services when the women get sick. The authors believe that mitigating these inequalities in urban Ethiopia demands both policy-related interventions and opening up opportunities for women to achieve economic empowerment towards strengthening their bargaining abilities in household relations although challenging patriarchy is difficult given the prevailing constraining factors.

Expression and revelation: Double burden of women and having a disease. Some of the target groups of this study and the key informants emphasized that women were exposed to a wide range of health problems including communicable and non-communicable diseases, which resulted from the men’s insensitivity to the rights of women at the individual, household, and community levels. The key informants contended that women are more susceptible to diseases than men given their low standard of living and several other factors that worsen their healthcare. Complementing this statement, an interviewed woman recounted:

I had asthmatic and kidney problems and desperately needed the local administration’s support letter indicating that I could not afford my healthcare and needed treatment in government healthcare facilities for free. Nevertheless, I was not able to get the support letter I needed and could not access the government healthcare facilities. Imagine, this is how people in lower-living conditions are suffering from health problems.

Participants of the FGDs corroborated these statements saying:

We know that women who lived with HIV/AIDS in Assosa city were discriminated against in receiving equal treatment for social services, benefits as government employees, and the like. In many cases, the absence of appropriate care and support for victims of the pandemic would make them rather hopeless thereby weakening sustained efforts to curb the spread of HIV/AIDS.

It can, therefore, be inferred that gender differences between men and women serve as the causes for the mistreatment and discrimination of the female sex. This would probably lead to an increasing rate of HIV/AIDS and the occurrence and re-occurrence of other diseases in the study area.

Expression and revelation: Traditional healing practices. Focusing on traditional healing practices, the informants argued that members of the community particularly women called on herbalists, religious healers, and witch doctors to get treated and recover from infectious and communicable diseases. The informants noted that women chose the traditional healing system mainly because they did not have adequate resources to pay for modern medical treatment. The experience of one of the interviewed women implies that she used the Holy Water (Tsebel) to relieve her pain. This, she argued, was an effective way of getting cured through the traditional practice of healing. The informant maintained that if she had to pay money for using the Holy Water, healing would have been impossible for her.

Similarly, a Muslim informant woman underpinned that traditional healing practices constitute an important component of the healthcare system of low-income Muslim women in Assosa city. She emphasized that prayer to Allah is critical for healing through mercy offered by the creator. It was also reported in the interviews conducted among the women that several low-income women were obliged to seek traditional healing for COVID-19 while local officials denied their rights to access vaccines for free. Understanding the women’s decisions to seek alternate traditional healing practices for COVID-19 because of gender discrimination, one can consider the adverse impacts of gender roles on women’s healthcare system.

9. The Impact of gender role on unemployment

The following section presents the major themes of revelation and expression in compliance with other sub-themes emphasizing that gender role determines the employment of the women in the study area.

Revelation and Expression: Illiteracy affected unemployed women. Some of the informant women and key informants noted that gender roles had impacts on women’s employment. This pertains to the fact that women in Assosa town had little access to education for the reason that they were relegated to reproductive labor in the household. In situations where the women were allowed to go to school, many withdrew for various reasons including familial and social pressure to get married. It was also evident that several women in the town had no access to education, and this indicates that women’s illiteracy is more noticeable compared to that of men. Viewing the impacts of being illiterate on women’s employment, we can articulate that men had the probability to take up gainful employment in the study area than women. The key informants underscored that nearly 75% of the city’s women are housewives with no employment of their own. In this sense, we can assume that illiterate women would often become housewives, or take up menial jobs that are neither sustainable nor yielding in terms of bringing self-worth and respect for the women.

Revelation and Expression: Anticipate socialization. Debating the influence of socialization on the personal development and prospects of girls, all the informants stated that the unemployment of girls and the consequent poverty they experience result from their interactions in the family and the tendency to abide by the prevailing gender norms and practices. Arguably, women’s relegation to household chores does not only reflect the gender-based division of labor, but also the fact that activities girls/women perform in the domestic sphere are not considered real work worth paying. Such practices thus would restrict women’s gainful employment in the public sphere thereby making them dependent on their spouses for survival. The absence of employment for women would trigger poverty in households. Concerning the influence of social norms on women’s socialization and prospects, an informant woman stressed:

Girls/women cannot take up jobs like shoe shining here in Assosa city for reasons of social norms that relegate females to carry on reproductive roles in households. I understand that females like males can engage in activities performed outside the household. This would certainly increase the opportunities for sustaining themselves and their families economically. However, I do not think that the existing gender norms would easily transform as they are strongly embedded in traditions through generations.

10. Gender role and infrastructure

Revelation and expression: Forced to live in a periphery. All the informants agreed that low-income women engaged in MSEs in Assosa city were forced to live in the periphery outside the city. The main reason, according to the informants, was that the administration gave little attention to non-indigenous women who engaged in low-paying jobs while favoring the indigenous community, investors from other regional states in Ethiopia, and other social groups. Moreover, it can be underscored that the women were compelled to sustain their living in the suburbs of Assosa city more than the non-indigenous men partly because of discrimination against their gender identity. Supporting this argument, an informant woman said:

We left the city [Assosa] and resettled in the outskirts under pressure from investors and the local administration. Even worse, the local people (indigenous men) threatened to exterminate us if we resisted the order to move to the periphery. We felt that we were discriminated against compared to the non-indigenous men who were allowed to live and work in the city. The problems with our new settlements in the periphery included but were not limited to the lack of access to potable water, road infrastructure, and power supply.

Sharing the informants’ views on how a combination of factors including gender discrimination made the women living in the outskirts of Assosa city vulnerable to infrastructural problems, a participant woman added that low-income women with children suffered most from among several others who were pushed to the periphery to sustain their living on small-scale retail shopping. Living and working under such difficult conditions, therefore, one would assume that the vulnerability of the women to poverty could be evident.

Revelation and expression: No listener to solve the problems. The informant women further disclosed that the city administration of Assosa was neither sensitive to addressing the impacts of gender roles on their living, nor provided them protection from insecure life situations in the suburbs of the city where almost all forms of infrastructure were not available for modest living and working. Losing all hopes that the government would make available the infrastructure needed by the people in the outskirts of the town, many of the informants planned to purchase some materials, for instance, water pipes, but the price was unaffordable and their attempts were futile.

Despite the city mayor’s office and the city council’s insistence to promote local infrastructural development in Assosa city and the surrounding areas over a decade, little was achieved particularly in the peripheries. Even worse, the local government did not listen to the plights of the women who engaged in the micro and small enterprises for development, nor engaged them in promoting the development scheme. Presumably, one would consider that the continued negligence of the local administration to respond to women’s development needs would largely jeopardize local development initiatives.

11. Discussion

Although a wide range of literature discusses the impact of gender roles on poverty (Hameed, 2014), gender status, and leadership, and identifies the gender gaps in educational attainment (Hek et al., 2016), little attention has been paid to the impact of gender role on urban poverty. This study reveals the experience of women engaged in MSEs pertaining to gender roles and their impacts on women’s access to education, health, employment, and infrastructure. Although the local population in Assosa city and the surroundings customarily view that girls/women’s academic achievements are strongly associated with their best performance in household chores (reproductive labor), it has been evident from the experience of informant women that local traditions appeared to put a halt on women’s educational attainments. This can be justified by the fact that girls/women devote much of their time to carrying on duties in the household than paying attention to their schooling both at the primary and secondary levels of education. This is the outcome of the gender-based division of labor that is embedded in the sociocultural ways of the community.

Understanding the impacts of gender roles on girls’/women’s education from the perspective of feminine values, we can argue that the local people prioritize female engagement in household activities as a measure of a woman’s worth more than achievements in education do. Further, the impacts of gender roles on girls’/women’s education can be understood with the practice of early marriage, which many people in the local community value for various reasons. Several women’s demeaning concepts about themselves that women are created to serve men can also be considered a challenge that women should overcome to ensure that they enjoy equal access to education and the opportunities resulting from schooling. This corresponds with the literature (Kapur, Citation2018; Frawley et al., Citation2020) that culture plays a significant role in peoples’ lives in adjusting to the social and natural environment, and developing personality in the communication process. This is congruent with the Jagero and Kushoka (Citation2001)’s ideas, which conceptualizes that women who engage in Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) are constrained to own properties by systemic institutional barriers and the prevailing gender ideology that legitimizes male dominance over women.

Gender roles had also adverse impacts on the healthcare services that the target groups of this study had to obtain. The women’s problems with accessing healthcare services were evident in the family where husbands denied the rights of their wives to medical treatment by forbidding them to access resources. On the contrary, husbands allocated household resources for their healthcare in hospitals or health centers while allowing their wives to visit traditional medical practitioners. The women’s desire for seeking solutions for their health problems through traditional approaches thus supports Cooroon et al. (Citation2014) arguments that healthcare-seeking behavior can be influenced by the cultural backgrounds, beliefs, norms, and values of a community. The husbands’ tendency to restrict their wives’ rights to appropriate feeding might also have negative consequences for the women’s health.

Conceptualizing the women’s healthcare problems stemming from the impacts of gender roles, the theory of dependency (Antunes de Oliveira, Citation2021) propounds that the intersection of various social variables including women’s lower living conditions, unequal household relations, gender biases, and unfavorable administrative and social environments complicate the healthcare services that women need to access. In addition, the impacts of gender roles can be explained by deterring women from understanding and using information for maintaining maternal health. In line with this, studies conducted by Lucas et al. (Citation2000), and Heizomi et al. (Citation2020) support that men are better at accessing and using health information than women.

The impact of gender roles on women’s employment has also been discussed in this study. The fact that the informant women had little access to education, or were dropouts before reaching a secondary level of education meant that gender role enormously affected their schooling. This can be understood in the sense that the women’s inability to pursue their education hindered them from seeking gainful employment in the local labor market. Consistent with this, we can see that gender socialization as John et al. (Citation2017) argue, reinforces the gender-based division of labor relegating girls/women to the domestic sphere where females’ reproductive role is not considered as real work. The outcome is that the patriarchal structure perpetuates unchallenged in the sociocultural, economic, and political life of women. This study further indicates that gender roles impacted informant women’s access to the infrastructure available in Assosa city. The underlying fact is that low-income non-indigenous women who were sustaining their living on small-scale retail shopping in the city were forced to relocate to the outskirts for reasons related to gender discrimination and social injustices. The problems with the women’s relocation outside the city included a lack of access to social services including potable water, electricity, transportation, and so forth, which exacerbated the women’s vulnerability to diseases, poverty, and security threats, particularly from the indigenous community.

Given the socio-economic challenges the women faced in the suburbs of the city and the increasing inattention by the local administration to address the problems, we can assume that the women in focus would be impoverished while the local development initiatives would fail to thrive. This finding emphasizes as several scholars (Chant & McIlwaine, Citation2016; John et al., Citation2017; Masika et al., Citation1997; Tacoli & Satterthwaite, Citation2013; Tacoli, Citation2012) contend, that gender inequality and social injustices would cause the forced evictions of low-income people by local governments making the evicted persons live in areas where social services and infrastructural developments are not accessible.

12. Conclusion

The impacts of gender roles on urban poverty can be explained in multiple ways. In patriarchal societies, a woman’s worth is measured in terms of feminine values that relegate the female sex to the domestic sphere. A girl’s success in performing household chores is considered an indicator that she will do better at school. However, in practice, reproductive roles take up much of the girl’s time affecting her success as a student. Early marriage also appears to deter girls’ education. This adversely impacts females’ literacy thereby restricting the opportunities for women to qualify for gainful employment in the labor market. Uneducated women’s perceptions about themselves that they are created to serve men also impede girls’ schooling. Presumably, women’s demeaning self-image reinforces the traditional view that educating girls helps little for their empowerment than allowing them to engage in a stable marriage.

Gender role also impacts healthcare services. Husbands often feel that their wives need not receive modern healthcare beyond seeking traditional medicine. This emanates from their misconception that women would not face health risks as they perform in the household while men are vulnerable to health problems owing to the nature of their work in the public sphere. Women’s lower living conditions combined with unequal power relations further complicate their healthcare services. Understanding the impacts of gender roles on women’s employment, we can also see that several women do not enjoy the right to education or withdraw from schooling implying an increase in the number of uneducated women. As one important triggering factor for girls/women’s withdrawal from schooling, early marriage, which results from familial and social pressure, is worth noting. Along with several other factors, the propensity to become uneducated or illiterate is central to the loss of gainful employment by the women in focus.

A combination of factors including gender-based discrimination, administrative bias, and indigenous community pressure placed women who engaged in MSEs in a marginalized position in Assosa city. The women’s marginalization can be explained in situations where they were pushed to the periphery with no access to electricity, potable water, and other social services. This jeopardized the women’s small businesses, complicated their efforts to escape from poverty, and made their life troubled. It is assumed that this study will allow policymakers to develop effective intervention strategies for dealing with the impacts of gender roles on urban poverty at the local, regional, and national levels.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to our respondents for their invaluable contribution and encouragement throughout writing this original article. It would have been difficult to realize our ends had it not been for their commitment, punctuality, and unreserved support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nahom Eyasu Alemu

Nahom Eyasu (MA) has been a lecturer of Sociology at the University of Gondar, Ethiopia. He is currently a Ph.D. student at Deakin University, Australia. His research focuses on governmental as well as societal responses to violence against women with disabilities with an emphasis on advancing societal systems through collaborative roles and multidisciplinary endeavors. Besides, his research interests focus on violence against women and girls, social determinants of health, gender equality, and mixed research methods.

Elisabeth Temesgen

Elisabeth Temesgen, MA, is a lecturer of Sociology at Assosa University, Ethiopia. She is recently a research coordinator at Social Science and Humanities College, Assosa University. Her research interest includes gender and society, urban poverty, and mixed research methods. Besides, she has a wide range of knowledge in reviewing classical and contemporary sociological theories.

Mesfin Dessiye

Mesfin Dessiye (Ph.D.) is an Assistant Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Gondar, Ethiopia. His research interests include transnational migration, return, and reintegration of returnees, gender and development, gender and sexuality, internal displacement, and governance of displacement. In addition, he has a research interest in conflict management, peace-building studies, indigenous knowledge systems, and care and support for vulnerable groups or communities.

References

- Aceska, A., Heer, B., & Kaiser-Grolimund, A. (2019). Doing the City from the Margins: Critical Perspectives on Urban Marginality. Anthropological Forum, 29(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2019.1588100

- Adjiwanou, V., & LeGrand, T. (2014). Gender inequality and the use of maternal healthcare services in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Health & Place, 29, 67–78.

- Ahuja, R. (2010). Methods of social research. Rawat Publication.

- Alene, E. T. (2020). Determinants that influence the performance of women entrepreneurs in micro and small enterprises in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovative Entrepreneurships, 9, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-00132-6

- Antunes de Oliveira, F. (2021). Who Are the Super-Exploited? Gender, Race, and the Intersectional Potentialities of Dependency Theory. In A. Madariaga & S. Palestini (Eds.), Dependent Capitalisms in Contemporary Latin America and Europe. International Political Economy Series. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71315-7_5

- Baker, J. (2008). Urban poverty: A global view. The World Bank and urban Sector Boards. World Bank Document.

- Beia, T., Kielmann, K., & Diaconu, K. (2021). Changing men or changing health systems? A scoping review of interventions, services and programmes targeting men’s health in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Equity Health, 20, 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01428-z

- Bernard, R. (2000). Social research method. Sage.

- Bernard, R. (2006). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (4th ed.). Altamira Press.

- Blackstone, A. (2003). Gender Roles and SocietyIn R. Julia, R. M. Miller, Lerner, & B. S. Lawrence (Eds.,)Human Ecology: An Encyclopedia of Children, Families, Communities, and Environments (pp. 335–338). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO

- Bradley, F., & Boles, K. (2003). Female entrepreneurs from ethnic backgrounds: An exploration of motivations and barriers. Manchester Business School.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

- Bruni, A., Gherardi, S., & Poggio, B. (2004). Doing gender, doing entrepreneurship: An ethnographic account of intertwined practices. Gender, Work, & Organization, 11(4), 406–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00240.x

- Chant, S., & McIlwaine, C. (2013) Gender, Urban Development and the Politics of Space. E-International Relations – open-access website. Retrieved from: http://www.e-ir.info/2013/06/04/gender-urbandevelopment-and-the-politics-of-space/

- Chant, S., & McIlwaine, C. (2016). Cities, Slums and Gender in the Global South. Routledge.

- Cohen, L., & Lawrence, M. (1994). Research Methods in Education (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Cooroon, M., Speizer, I., Fotso, J., Akiode, A., Saad, A., Calhoun, L., & Irani, L. (2014). The Role of Gender Empowerment on Reproductive Health Outcomes in Urban Nigeria. Maternal Child Health Journal, 18(1), 307–315. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23576403

- Creswell, J. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design. Sage.

- DeMartino, R., & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: Exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(6), 815–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00003-X

- Dowuona-Hammond, C. (2007). Improved Land and Property Rights of Women in Ghana. Accra, Ghana: Donor Committee for Enterprise Development Family and Market. Journal of Agrarian Change, 3(1–2), 184–224.

- Drucza, K., Tsegaye, M., & Azage, L. (2019). Doing research and ‘doing gender’ in Ethiopia’s agricultural research system, Gender. Technology and Development, 23(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2019.1616361

- Du, H., Xiao, Y., & Zhao, L. (2021). Education and gender role attitudes. Journal of Population Economics, 34, 475–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00793-3

- Eshetu, B., & Zeleke, W. (2008). Women entrepreneurship in micro, small and medium enterprises: The case of Ethiopia. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 10(2), 3–19.

- Fielden, S., Davidson, M., Dawe, A., & Makin, P. (2003). Factors inhibiting the economic growth of female-owned small businesses in North West 77 England. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 10(2), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000310473184

- Frawley, J., Russell, J., & Sherwood, J. (2020). Cultural competence and the Higher Education Sector.

- Haile, M. (2022). Micro and Small Enterprises in Ethiopia: Access to Credit – Challenges and Solutions, Gbnews.ch

- Heizomi, H., Iraji, Z., Vaezi, R., Bhalla, D., Morisky, D. E., & Nadrian, H. (2020). Gender Differences in the Associations Between Health Literacy and Medication Adherence in Hypertension: A Population-Based Survey in Heris County, Iran. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 16, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S245052

- Jagero, N., & Kushoka, I. (2011). Challenges Facing Women Micro Entrepreneurs in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 1(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v1i2.1023

- John, N., Stoebenau, K., Ritter, S., Edmeades, J., & Balvin, N. (2017). Gender Socialization during Adolescence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Conceptualization, influences and outcomes. Innocenti Discussion Paper 2017-01. Available at https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IDP_2017_01.pdf

- Kapur, R. (2018). Determinants of culture aspects up on education. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323794724_Impact_of_Culture_on_Education

- Khalid, R. (2011). Changes in perception of gender roles: Returned migrants. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 16–20. https://gcu.edu.pk/pjscp-archives/#1587019355833-46d0f639-b98f

- Kim, V. L. E. (1993). Changing Suburbs, Changing Women: Geographic Perspectives on Suburban Women and Suburbanization. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 14(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346556

- Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Sage Publications.

- Lucas, J. A., Orshan, S. A., & Cook, F. (2000). Determinants of health-promoting behavior among women ages 65 and above living in the community. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 14(1), 77–100. Spring discussion 101-9. PMID: 10885344.

- Masika, R., Haan, A., & Baden, S. (1997). Urbanization and Urban Poverty: A Gender Analysis. Report prepared for the Gender Equality Unit, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).

- Maypole, J., & Davies, T. G. (2001). Students’ Perceptions of Constructivist Learning in a Community College American History II. Community College Review, 29(2), 54–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/009155210102900205

- Mertens, D. (2005). Research Methods in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Moscarelli, R. (2021). Marginality: From Theory to Practices. In P. Pileri & R. Moscarelli (Eds.), Cycling & Walking for Regional Development. Research for Development. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44003-9_3

- Mostert, J., & Gulseven, O. (2019). The role of gender and education on decision making. Studies in Business and Economics, 14(3), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.2478/sbe-2019-0048

- Naz, F., de Visser, R., & Mushtaq, M. (2022). Gender social roles: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 32(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2021.1878971

- Qing, S. (2017). Gender role attitudes, family responsibilities and female-male labor force participation patterns. Journal of Social Science, 11, 91–100.

- Sedgwick, P. (2014). Cross-sectional studies: Advantage and disadvantage. Centre for Medical and Healthcare Education, St George’s, University of London.

- Tacoli, C. (2012). Urbanization, gender and urban poverty: Paid work and unpaid carework in the city. Urbanization and emerging population issues working paper 7.

- Tacoli, C., & Satterthwaite, D. (2013). Editorial: Gender and Urban Change. Environment and Urbanisation, 25(1), 3–8. Retrieved from http://eau.sagepub.com/content/25/1/3.full.pdf+html

- Tadesse, H., Gecho, Y., & Leza, T. (2021). The impact of the participation of women's micro and small enterprises on poverty in Hadiya zone, Ethiopia. Social science, 1, 243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00245

- Tzvetkova, S., & Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2017). Working women: What determines female labor force participation. Our World in Data.

- Uneke, C., & Uneke, B. (2021). Intersectionality of gender in recruitment and retention of the health workforce in Africa: A rapid review. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 27(7), 698–706.

- Wekerle, G. R. (1980). Women in the Urban Environment. Signs, 5(3), S188–214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173815