Abstract

The public sphere has been inaccessible to women in Ethiopia for a long time. The truancy of women, in particular, from politics has affected their life enormously. Politicians’ involvement is crucial because it fosters women’s direct participation in public decision-making, which advances gender equality and empowers them. Recent developments in the scholarship of women’s political participation and representation have sparked a debate on how descriptive (or numerical) representations can positively affect substantive representations. In this article, we explore the level of women’s political representation and examine how it affects their substantive contribution in two local governments in the Amhara regional state of Ethiopia. We have employed the critical mass and critical act theories to build the theoretical framework. We utilized a qualitative approach to address our objectives. The findings of this article demonstrate that women are adequately represented in the councils of the two local governments. More importantly, the influence of elected women increased in the decision-making processes, in particular, in group deliberations. Their impacts on the councils and the local governments, in general, have become very significant. Though there are still issues to be addressed, women in local government are becoming more visible in the political arena. We conclude that the number of female representatives in the councils is directly related to their political participation. As their number increases, their decision-making power and influence increase.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study, entitled “Women’s Political Participation at the Local Level in Ethiopia: Does Number Really Matter?” is a research endeavor primarily to address the level of women’s political representation and participation at two local governments in Amhara regional state, in Ethiopia. Ethiopia has undergone changes since 1991 that have expanded the country’s populace’s political participation. The government has also paid significant attention to women as members of society. It has been working to increase women’s political representation and participation at the national level. At the local level, however, women have not received much attention. Therefore, the goal of this study was to investigate women’s involvement in local politics. The findings demonstrated that women are fairly represented at the local level and that their actual political engagement has increased as a result of the higher level of representation.

1. Introduction

This research sought to examine the level of women’s political engagement and decision-making in the Amhara regional state’s Fogera Woreda and Woreta Town administrations. Since 1991, Ethiopia has decentralized into eleven (11) regional states, according to a federal-state structure. Regional governments further decentralize into woreda (district) and city administration. A woreda is established in rural areas, while a city administration is an urbanlocal government (Ayele, Citation2022). It was a move to institutionalize the decision-making process at the grassroots level to enhance local participation, promote good governance, and enhance decentralized service provision. It was also a move to extend self-governance to the lowest level of government structures and empower local people (Ayenew, Citation2007). As the lowest tiers of government, with local councils whose members are directly elected by the local populace, woreda, and town administration structures are convenient for locals to exercise self-governance (Ayele, Citation2014). Since there haven’t been any local government elections since 2015, this research is based on information from previous elections.

Women have been systematically excluded from social, economic, and political life for a very long time due to the patriarchal system that is ingrained in every society. Women thus occupy a lower social status in society. Women’s full and equal participation in all facets of society is a fundamental human right yet they are disproportionately underrepresented in all spheres of life, including politics (UN Women, Citation2020). Despite making up over half of every community, their political involvement, is still minimal (Bari, Citation2005; Rooke, Citation1972). In Ethiopia, women have been excluded from almost all aspects of society and have had limited access to politics. The culture as a whole strongly discourages women from participating in politics as it is an obstacle in many in Africa countries. The political system is structured on male beliefs and norms, making it challenging for women to get along there (Aubyn, Citation2022). The government of Ethiopia has developed many policies and programs that are supported by the Beijing Platform of Action and Millennium Development Goals to overcome historical exclusion and enhance the condition of women. It seeks to address gender equality and the gender gap through institutions and policies that advance the objectives. One of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) is gender equality and women’s empowerment, and in recent years, it has gained widespread recognition as a crucial instrument for achieving all of the other SDGs. The road map for achieving other SDGs and ensuring sustainable human development worldwide is improving gender equality and empowering women (Crawford, Citation2020).

The Ethiopian government has introduced a variety of policies to foster an atmosphere that supports women’s advancement. Through the revision of various laws, including family law, labor law, pension law, and criminal law, major advances have been made toward ensuring the formal equality of women. Women’s empowerment and gender equality have also been a focus of the country’s development and poverty-reduction programs and measures. To operationalize the commitments that have been made at the national and international levels, several institutional arrangements and beneficial measures have been established (FDRE, Citation2019). Through national joint planning meetings involving sectoral line ministries and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the government further established gender as a cross-cutting issue (MoFED, Citation2010). The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Front (EPRDF), today known as the Prosperity Party, introduced a voluntary party quota in 2004 that reserves 30% of the candidacies on the party list for women in an effort to improve women’s representation and political participation. According to Shaffo (Citation2010), Okock and Asfaw (Citation2014), and Okock and Asfaw (Citation2014), the percentage of women legislators in the national legislature has increased since the implementation of the quota system, rising from 7.6 percent in the election held in 2000 to 38.8 percent in the election of 2015.

Numerous studies conducted to date show that the creation and application of laws, legal frameworks, and quota systems boosted the number of women who participate in politics on a national level. According to the author’s knowledge, no local studies of this nature have ever been carried out. Hence, it is still uncertain if a comparable experience has been reported at the level of local governments. However, given that local politics has historically been dominated by men, one could anticipate that the number of women participating in politics at the local level would be low. The study addresses the following objectives: to investigate the extent of women’s political representation and how they participate in the political deliberation and decision-making processes in the local governments of Fogera Woreda and Woreta City.

2. Research methodology

This study uses two districts as a case study to examine the extent of women’s political engagement, discussion, and decision-making processes at local governments in Ethiopia. Given that exploratory research tends to uncover new information, a qualitative research approach works best in these situations (Khan, Citation2010). Furthermore, as Creswell (Citation2003) suggests, a qualitative approach is followed when the researcher seeks to set up the meaning of a phenomenon from the views of participants. The scholarship of women’s political participation and representation has been getting the attention of researchers. However, the issue of political participation at the local government level has not been addressed. Because of this, we believe little is known about women’s political participation at the local level in Ethiopia. Effective use is made of both primary and secondary data to attain the objectives. Particularly, the statistical data on the representation of women in the two local administrative governments was derived from an in-depth review of documents and annual reports acquired directly from the local governments. At several points in the sampling procedure for interviews, the purposive sampling approach was applied to select information-rich informants. According to Patton (Citation1990), information-rich informants are those from whom one learns plenty of issues of vital importance to the purpose of the research. Therefore, interviews were conducted with elected female members from both local administration councils, the Woreda and town administrations’ women’s affairs offices, male council members, and administrative heads of both local governments. The data saturation method was used to calculate the sampling size. The data were presented and discussed using themes developed through thematic data analysis.

3. Conceptual and theoretical framework

3.1. Political participation

According to Uhlaner (Citation2015), there is no universally accepted definition of political participation. For Huntington and Nelson (Citation1976), for instance, “political participation” is an activity by private citizens designed to influence government decision-making. Similarly, Verba and Nie (Citation1991) defined political participation as legal actions taken by individuals with the express purpose of influencing the selection of public officials and the decisions they make. These two definitions centered on the objectives of political engagement, which has an impact on the choice of public officials and their decision-making. Whereas Diemer (Citation2012) and Riley et al. (Citation2010), on the other hand, emphasized political participation as political engagement and outlined its means of participation. Diemer (Citation2012) referred to political participation as participation in traditional political systems, such as participating in elections and forming political organizations. Similarly, Riley et al. (Citation2010) approached political participation as an engagement and asserted that it has traditionally been thought of as a set of rights and duties that involve formally organized civic and political activities (e.g., voting or joining a political party). Both approaches are necessary to conceptualize political participation in this research. For this study, political participation is conceptualized as an engagement through which individuals could participate in traditional forms of political participation to influence the choices of government officials and their decision-making.

3.2. Critical act and critical mass approaches

Critical Act and mass approaches are associated with the concepts of descriptive representations and substantive representations. According to Pitkin (Citation1972), “descriptive representation,” alternatively termed “standing for,” refers to the notion that the connection between the representation and the represented is based on shared characteristics or experiences, such as gender. The justification for descriptive representation is that, by virtue of their identity, the representations have certain traits that have been assigned to the group they represent. Women representing women can therefore be viewed as a form of direct involvement in decision-making bodies. However, other scholars contend that women’s descriptive representation merely counts the number of women holding political positions without considering what women representatives are actually accomplishing for women (EGM/EPDM Report, Citation2005), whereas substantive representation, which is termed “acting for,” favors an emphasis on whether the representative is able and willing to act on behalf of the interests and concerns of those represented (Pitkin, Citation1972). It is about the impact of women in decision-making positions on policy formulations and implementations. It focuses on how women’s presence is necessary for the development and implementation of policies on development, sustainable peace, good governance, and gender equality (EGM/EPDM Report, Citation2005). It is believed that women in decision-making positions play a crucial role in developing meaningful gender mainstreaming strategies that effectively and authoritatively ensure a focus on gender equality in all policy areas (ibid.). The underlying assumption of the critical mass theory is that an increase in women’s involvement in politics affects the content, style, and mechanism of politics as compared to the male-dominated context (Holli, Citation2012). Mansbridge (Citation1999) also argues that “for women and historically disadvantaged social groups; the entry of representatives into public office improves the quality of group deliberations, increases a sense of democratic legitimacy, and develops leadership capacity”. It is argued that when women’s numbers increase in the political arena, women will be able to work more efficiently together to promote women-friendly policy change (Sarah & Krook, Citation2008). However, women affect the content and quality of decision-making only after their proportion reaches a certain “critical mass.” According to Kanter (Citation1977), the threshold varies from 15%–40%, whereas Dahlerup (Citation1988) set the threshold at 30% (Dahlerup, Citation1988; Kanter, Citation1977). Therefore, the focus of the critical mass is whether women have reached a critical mass and if that affects the political deliberations in the local governments. Whereas, the underlying assumption of the Critical Acts approach focuses not on the number of women or the dedicated quota filled by them but rather on how far elected women stood for their interest and were substantive enough in protecting women’s issues (Holli, Citation2012). In this study, for the analysis of women’s participation beyond numbers, both theories merged to create a symbiosis. Hence, the theories are necessary to address the question of whether women’s representation in the local governments has reached a critical mass, and if so, does it affect the contents and qualities of political deliberations and decision-making in the local governments? Moreover, it also investigates whether women’s representatives stood up for the interests of their fellow women. The critical mass approach is used to study the representation of women in local governments and its impact on political deliberations, whereas the critical act approach examines the substantive contribution of women in local governments.

4. Discussion and analysis

For anonymity, the key informants are coded as RP with their respective numbers.

4.1. Woreda council

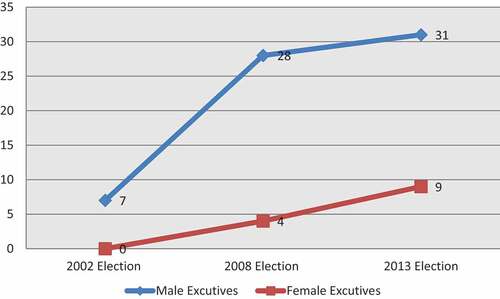

The Fogera Woreda Council (hereafter the woreda council) is the branch of the Fogera Woreda administration whereby the will of the electorates is executed through their elected representatives. The current Woreda Council has one hundred, and thirty-six (136) elected representatives. The representatives come from 31 kebeles that serve as electoral areas in the woreda. Out of the 31 kebeles of the woreda, nineteen (19) have four (4) representatives each, and twelve (12) have five (5) representatives each. As a result, currently, half of the 136 members of the local council are female representatives. The number of elected female representatives in the woreda council is sixty-eight (68), which is, 50% of the local council. The number of women in the woreda council shows that women have already reached a critical mass. According to Kanter (Citation1977), women’s representatives can reach a critical mass if their representation falls in the range of 15%–40%. For Dahlerup (Citation1988), the critical mass can be secured as long as the 30% representation is secured. Women’s representation in the woreda council has already secured more than the percentages set by both scholars. The critical mass nature of women’s representation in the woreda council is necessary for the political deliberations and engagement of women in the woreda council and beyond. The woreda council is headed by two speakers, who are appointed by the general council. The positions of speakers on the council are shared between male and female members. Accordingly, the speaker is a male while the deputy speaker is a female. The data shows that there has been a remarkable growth in the representation of women in the woreda council. It also indicates that there has been continuous growth since the 2002 local election. The increase of female representatives in the woreda council is in line with the growth of women’s representation in the national assembly. The representation of women in the national parliament has increased from 7.6 percent in 2000 to 38.8 percent in the 2015 national election. Studies associated the growth with the introduction of the voluntary party quota by the ruling party (Alemu, Citation2010; Shaffo, Citation2010). The increase in the woreda councils follows a similar trend. The chart below shows the number of female representatives in the woreda council in the last three consecutive local council elections.

The chart above illustrates that the number of elected female representatives in Woreda Council increased significantly in 2013 compared to 2002. It increased from twenty-one (21)—which is 25 % of the 84 local council members in 2002 – to forty-four (44)—which is 36.7% of the 120 council members in 2008 – and to sixty-eight (68), which is 50% of the total 136 council members in 2013. Such developments show that much has been done to increase women’s representation in the woreda council. Considering the condition of women in the country and their experience, it is an enormous success for women in the woreda. Therefore, the current representation of women is capable of representing their interests.

Meanwhile, the representation of women in the woreda executive council and the standing committees is found to be very relevant to this discussion. The structure of the woreda administration shows that both the executive council and standing committee are directly related to the woreda council. Two justifications are presented here to justify the need to investigate women’s representation in the executive council and the standing committees. Firstly, both the members of the executive council and the standing committees are derived from the local council through appointments. That makes some of the members of the woreda council legal members of the executive council. There is a fusion of membership between the woreda council and the executive. Secondly, the powers and authorities of these organs are critical in local government politics. The discussion on the representation of women cannot be complete without the inclusion of these organs. The standing committees are organized by the executive to oversee the implementation of policies, programs, and directives. They are supervisors of the executive council. Also, the members of the executive organ are the direct implementers of the policies and programs. They have more power to decide how policies are implemented in the woreda. Then it is logical to investigate if women are getting opportunities to be appointed to these organs. There are five main standing committees with three members each in the Woreda Council. They are established to follow up on the activities of the executive council on five broadly divided issues, and there is also one combined committee made up of five members. These are the main standing committees: the economic affairs committee, the social affairs committee, the women’s and children’s affairs committee, the good governance committee, and the budget committee. Of these, the economic affairs and budget standing committees do not have female members, whereas the social affairs and good governance standing committees have one (1) female member each. The women and children’s affairs committee has all-female members. Therefore, out of the 15 members of the standing committee, there are only five female members, who make up 33% of the total. Also, out of the five (5) members of the combined committee, two (2) are female. When the leadership positions are assessed, out of the five standing committees and the combined committee, only the Women and Children’s Affairs Committee is led by a female head (See Figure ).

Figure 1. Number of Male and Female Representatives Elected for Fogera Woreda Council in Three Elections.

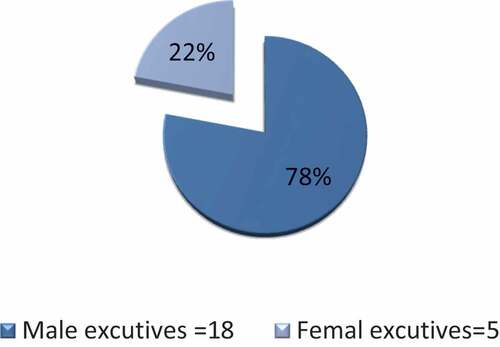

The members of the executive council are appointed by the chief administrator with the approval of the local council. Often, the members are recruited from the local council itself. The same trend is practiced at the national level as well. The experience shows that the winning party prefers and has a legal right to nominate executive members from among the legislative members. The woreda executive council members are appointed to lead sector offices as heads and deputies. There are forty (40) executive members in the woreda council, leading twenty sector offices. Out of the forty (40) executive members, only nine (9) are female, which is 22.5%. However, out of the twenty sector offices, women head only two (2): the women and children’s affairs office and the commercial and finance office (See Figure ).

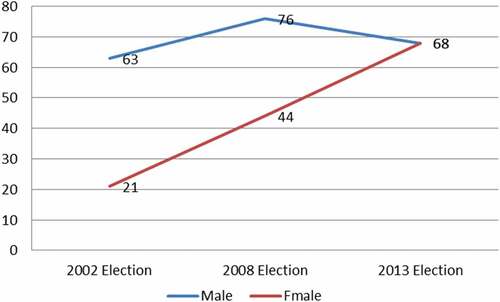

The chart below illustrates the number of males and females appointed to the executive council in the last three consecutive elections.

The chart above demonstrates that the number of women executive members grew from none in the 2002 election to nine (9) in the 2013 election. The growth is quite slow compared to the male, which grew from seven (7) in 2002 to thirty-one (31) in 2013. The data also show that none of the women members has had the opportunity to be elected as chief administrator or deputy in the woreda administration. The discussion demonstrated that women are represented equally in the woreda council. The data also shows that there has been continuous growth since 2002. The analysis also showed that women are less represented in the woreda council’s standing committees and the executive councils. However, in the executive council, a slight change has been registered since 2002, as it grew from none to nine members. Therefore, considering the significance of the executive council at the current level is unsatisfactory

5. Town Council

The Woreta Town Council (hereafter the Town Council) is made up of representatives elected from the four kebeles of the town administration. The town council members are elected by the people to act as the highest organ of the town government, and they serve for five years. The Kebeles are the lowest local government structures that act as a base for the local government and serve as electoral areas. According to the Amhara Regional State Proclamation No. 91/2003, the number of each kebele representative in any town council cannot be less than eleven (11). Taking this proclamation into consideration, the Town Council provides twenty-three (23) seats for each kebeles found in the town administration. Currently, the Town Council has ninety-two (92) members representing the four kebeles. Out of the 92 members, women accounted for half. The town council is led by a speaker and deputy speaker. The position of the speaker is occupied by a man, and the deputy is a female. It is also important to see the development of women’s representation in the town council. To do so, it is necessary to discuss women’s representation on the previous town council. As previously mentioned, the Woreta Town local administration was formed in 2007 and had its first local council election in 2008. Therefore, there were only two local elections for the town government. That makes only the 2008 local election a point of reference to study developments in the number of women representatives in the town council. As a result, the town council had 90 representatives in 2008, with half of them being female. The number of male and female representatives was 45 each, which is 50%. There was no difference in the number of representatives between the 2008 and 2013 elections. Since the formation of the town administration, women have been equally represented in the local council as men. Like the Fogera Woreda council, in the town council, the positions of speaker and deputy speaker were held by men and women, respectively. The discussion of women’s representation in the town executive council and the standing committees follows a similar rationale given above in the discussion of the Fogera Woreda administration. Meanwhile, the members of the Woreta town executive council are made up of the town mayor, his deputy, and the chief of executive offices of the town administration. Often, members of the executive council are appointed by the members of the town council. It is also legally possible to appoint members outside of the local council. The appointment takes place when the town council approves the mayor’s nomination of members. The town executive council is an administrative wing of the town council. The way the executive council is established and the power bestowed on it make an analysis of women’s representation in the executive council imperative. Thus, the town executive council consists of individuals leading 19 sector offices as chief and deputy executive officers. Among these offices, only four (4) have deputy chiefs. Currently, there are twenty-three (23) executive members in the town administration (See Figure ).

The chart above shows that out of the 23 executive officials, male members comprise fifteen (15) positions as chief and three (3) positions as deputy chief. In total, eighteen (18) or 78% of the executive council members are male, whereas women hold only three (3) offices as chief and two (2) positions as deputy. Among these, women in the executive council make up only 22%. The number of female executive members is highly inadequate compared to the number of women local council members. That affects the number of public offices run by women. The development of the number of female executive council members in the town administration is also very slow. The difference in the number of female members of the 2008 and 2013 executive councils is very small. The number of executive council members in the 2008 elections was also twenty-three (23); out of which, the males were twenty (20) and the women were only three (3). It is also found out in the two consecutive executive councils that the town mayor and the deputy mayor are both male too. Coming to the discussion on the standing committees, the Town Council has five (5) standing committees with three members each and one combined committee with five members. Members of the standing committees and the combined committee are appointed from among the town council members. Each standing committee has a leader. These committees follow up on the activities of the executive committee and the town mayor. They are supervisors of the activities of the executive council and are pertinent in giving feedback on the implementation of the policies and programs of the town administration. The five standing committees are the economic and development affairs committee, the human resource and tourism development affairs committee, the women and children affairs committee, the law, justice, and good governance affairs committee, and the budget and finance committee. There are 15 members of the standing committees. Of these, nine are female members, whereas six are male members, i.e. 60% and 40%, respectively. Women members of the standing committee are higher than the men. However, the data show that men control more leadership positions in the standing committees. Women are heading only two of the standing committees, while men are leading three. From the five members of the combined committee, two are women, while the rest are men, including the leader. It shows that even though the number of women in the standing committees is higher than that of men, they lead fewer standing committees than men. Also, their membership in the combined committee is less than men’s. The discussion shows that the status of women’s representation in the town council is equal to that of men. The number of female council members has been constant since the formation of the town council. The town council has maintained gender equity since its formation. There are more female members in the standing committees than male members. However, they are heading fewer committees than men. On the other hand, there are few female members of the town executive council, and the development is very slow too.

6. Participation Beyond Numbers: Substantive Representation

The above discussion demonstrated that women are well represented in both local councils. Representation is assumed to be the first step for women’s political participation. For this reason, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action exhorted all governments to adopt affirmative‐action measures to ensure a quota for women to increase their representation (Falch, Citation2010). It is asserted in the critical mass theory that if women reach a certain level of mass representation in the legislature, their political impact and visibility increase. Kurebwa and Ndlovu (Citation2017) also asserted that women’s mass representation could affect the content, style, and mechanism of politics as compared to male-dominated ones. Hence, the mass representation of women can diversify the substance of the issues discussed in the local councils. Moreover, the critical mass nature of women’s representation can improve the quality of group deliberations (Mansbridge, Citation1999). Critical mass is a small segment of the population, that chooses to make big contributions to collective actions. In the case of the local councils, women representatives are regarded as having critical mass as they are assumed to represent local women whose interests have been ignored by the majority. Power (Citation1987) argued that collective actions usually depend on a “critical mass” that behaves differently from other group members. The level of the critical mass, and their viewpoints are keys to predicting the probability, extent, and effectiveness of collective action (Oliver et al., Citation1985). Hence, the level of women’s representation as a critical mass influences group deliberations in the local councils. The data from the Woreda and the Town Councils confirmed that women had reached critical mass. Women hold much higher seats in the councils than the thresholds set by Kanter (Citation1977), 15%–40%, and Dahlerup (Citation1988), 30%. On the other hand, critical act theory focuses on the substantive contributions of women representatives to their constituencies, most specifically women. In the next section, we discuss the participation of women in local governments and whether their participation is making a difference. In other words, do they have a voice in the decision-making process in the local councils?

7. Group Deliberations

According to Mansbridge (Citation1999), mass representation helps to improve the quality of group deliberations. And Fearon (Citation1998) defined group deliberation as a process allowing a group of actors to receive and exchange information, critically examine an issue and come to an agreement that will inform decision-making. It is a communication process in which groups engage in a rigorous analysis of the issues at hand and engage in a social process that emphasizes equality and mutual respect (Black, Citation2013). In this regard, informants’ views from both local councils reinforced the assertion that mass representation improved group deliberations in the local councils. They claim that female council members’ engagement in political discussions and decision-making processes improved in councils following their increase in number. Women are presenting their perspectives as much as they can, and they are also contributing to the political deliberations. Many informants declared that women are actively involved in discussions and debates, making the local councils’ environment more attractive. Female council members are becoming more outspoken and committed, as stated by an informant from the town council (RP09). When the number of women increased in the councils, their contributions also increased. They bring more diverse ideas and issues to the local councils. Furthermore, being in the councils can help them develop their critical thinking skills. Some informants stated that women started to make crucial and constructive comments in the councils (RP 04 and RP 09). Some of the informants believed this was because of their exposure and the training provided to them. Meanwhile, group deliberations may be affected by the kinds and substances of ideas entertained in the councils. In this regard, female council members contribute to the council by bringing in different perspectives and issues. An informant from the town council argued in the following manner regarding female council members’ contributions: “Issues discussed in the council used to be more routine like budget, regulations, and appointments. Women used to only raise their hands for the supporting vote. Current developments show that female council members are using the council to advance the social, economic, and political interests of their society. They bring problems that are ignored or undervalued by others. “Women prefer to debate issues rather than simply vote, especially on women’s issues” (RP8). The process of group deliberation can also be affected by the confidence of women council members to discuss and deliberate their views without fear openly. In this regard, informants believe that the mass representation of women in the councils increased their confidence to speak openly and freely. A respondent from the Woreda Council who is elected to the council for the second term said the following: “In the previous local council, it was not easy for women council members to stand up and express their views in the male-dominated council. The traditional views upheld that women are not supposed to speak in front of a crowd, and the dominant nature of the male council members made women restrained from expressing their views. Often, when a female council member stands to speak, some men feel uncomfortable. As many of the Fogera Woreda representatives came from rural areas, their attitudes toward women were not positive. However, now things are different because of the increasing number of women in the local council” (RP03). Another informant also expressed that “previously, not only women were apprehensive to speak in the council, but also some male council members often used to make fun of women and sometimes laugh at them.” “Fortunately, because of the mass representation of women, they are confident to stand and speak without any fear or shyness” (RP02). Bari (Citation2005) also asserts that female mass representations help women develop confidence by creating solidarity among them. The way local council meetings are conducted can influence the political deliberations of women in the councils, too. It is critical to consider how convenient the meeting place and time are and whether meeting agendas are communicated clearly before the meetings. Informants from both local councils responded to these questions affirmatively. They claimed that local councils’ meeting halls are constructed to fulfill basic needs and are convenient. The researchers also observed that both local governments’ council meetings are conducted in fully equipped rooms that are suitable for conducting meetings. The meeting hours are also strictly observed, and they are always from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Informants believe the meeting hours are convenient for them. They also stated that they are often informed about the agendas, some days before the meetings, except for extraordinary meetings. The rules of the local government councils stated that the local councils should inform the council’s members about the agenda, time, and meeting place before the meetings (Fogera Woreda Council Guideline, Citation2013). However, the rule does not state a specific date. We can conclude that when the number of women has increased in the councils, they will have much influence in setting up the rules and regulations of the councils and how council meetings are conducted.

8. Substantive Contributions

According to the critical Act approach, women’s participation is measured substantively through their contribution to protecting the interests of women and the people in their constituencies (Holli, Citation2012). It is related to their commitment to addressing problems inside and outside the local councils. Elected women can contribute by bringing the issues into the local councils’ agenda-setting process. They also can participate by following up on their implementations in the local administrations. The responsibility of the standing committees is to follow up on the execution of the councils’ decisions by the executive councils. However, elected women can contribute more to the implementation process. In this regard, informants from both local councils stated that elected women are becoming increasingly active in bringing social, economic, and political issues to the local councils that are pertinent to their constituencies in general and women in particular. Informants noted that women council members are more valuable in addressing women’s issues as they are more familiar with and informed than men. An informant argued that women are more open to expressing their problems to female council members than males (RP04). The substantive contribution of women council members is necessary because representation without real participation does not add up to anything in value for women’s empowerment and society. The data reveals that women in both councils are aggressively contributing to society. The improvement of women’s political participation has been impressive considering their recent entry into local politics. An informant from the woreda council expressed the rise of women’s participation as follows: “It is my second term in the woreda council. I observe significant changes in the involvement of women in the council. They are now contributing a lot to the woreda, especially for women. The government has formulated some policies and programs to empower women in the country. However, their implementation at the local level was poor because of a lack of follow-up. However, female council members are working hard to ensure the implementation of those policies and programs to help women in the woreda. “Positive results are being seen, for example, on the issues of maternity rights, the equal share of properties in marriage and inheritance, the provision of affirmative action, and the fight against traditional harmful practices” (RP02). An informant from the Woreta Town Council stated that women on the town council had addressed many problems women were facing in the town. She indicated that they influence the town administration to provide health access to women engaged in sex work, arrange financial support and loan access for widowed and unemployed women, and organize them in micro-enterprises, hence they can work together (RP07). Another informant from the woreda council also stated that as a rural woreda, women’s problems in Fogera Woreda are more complicated than those in the town administration. She asserts that women in rural areas are not open to talking about their problems because of cultural issues. Hence, female council members are usually expected to spend more time and energy investigating those problems. She claims that the matter of property rights, especially access to land, the equal share of wealth and household responsibilities and decision-making power, sexual violence, and gender discrimination are given more focus because of their widespread nature, and many of these issues are getting addressed (PR04). The female council members’ substantive contribution can be measured by the project they developed to help women and society at large. In this regard, informants stated that they had proposed different projects to improve the lives of women. A respondent from the woreda council said that projects to address the issues of early marriage, sexual violence, and female education have been proposed and accepted in the woreda (RP03). Similar projects are also implemented by the town administration. Moreover, plans to ensure women’s economic opportunities have been proposed (RP08).

The discussion shows that female council members from both local councils are substantively contributing to defending the interests of women in the local governments. This is in line with the assertions of the critical mass and act theories. Women must be adequately represented in local councils. In addition, the environment of the local councils should be more convenient so women can fully participate and contribute substantively. However, from a substantive point of view, the representation of women in the local councils is not enough to realize women’s political participation in local governments. Informants stressed that women need to be appointed to key positions to bring about significant changes. They asserted that female council members are not appointed to prominent positions due to the wrong perception of the local officials about the capacity of women. Informants also revealed the existence of many women with less education in the councils. However, they stated that even educated and capable women are unable to secure key positions (RP06 and RP09). Some informants even believe that the very reason women’s representation increased in local councils was due to the quota system. Mass representation of women in local councils does not necessarily mean women are politically empowered unless they have equal access to higher positions. It is necessary to notice that the political system in the country could make local councils weaker, even though, in principle, councils are the highest organs of the local governments. The one-party nature of the local councils makes the decision-making process much easier than usual. The executive councils can bring (or introduce) any policy or program for a decision to the councils, which will be automatically approved. The only reason they bring programs and policies to the local councils is for the sake of legitimacy, not for viable political deliberation. In such cases, women have no power to influence such policy decisions in the councils. Hence, if their number is insignificant, especially in the executive councils, it is hard to think that they would make any impact at all. Some critics of the government also argue that the ruling party is using women only to show off—a typical case of window dressing. They argue that without providing real power to women, the government organizes women without genuine civil society activities and pretends they are empowered. This symbolic gesture enables the government to hijack the legitimate question of women (Midekssa, Citation2012).

9. Conclusion

This article’s main objective was to examine the representation of women in politics and their level of substantive involvement. Men and women have distinct wants, interests, and goals due to historical, social, cultural, and economic circumstances, among other things. Therefore, they are unable to adequately represent one another. Democracy must indeed be able to accommodate the variety of requirements and interests of society as a whole. In order to defend their interests, women must therefore be represented in political institutions. This prompts us to critically evaluate their query about representation at various levels of government. According to the critical mass and act theories, the number of women representatives in local government councils is directly related to their political participation. As the number of female representatives increases, their decision-making power and influence also increase. For women to substantively contribute to the local government councils and defend their interests, they need to arrive at a critical mass of representation where they can be capable of influencing the decisions of the local councils. Therefore, the number of women’s representatives in politics matters in terms of their political participation and representation. The results of this study showed that, despite the widespread belief that women may have been underrepresented at the local level, women are currently sufficiently represented in the two local administrations. The results also revealed how the rising percentage of women in the two local governments significantly influenced their political participation and deliberation.

The descriptive representation of women in the study areas contributed greatly to their substantial representation. Following the increase in the number of representatives in local government councils, women’s political deliberations and decision-making capacity have made progress. The various institutional arrangements, legal and policy frameworks the Ethiopian government has been putting in place to advance women’s status and guarantee their equality have shown real progress, particularly in terms of women’s political participation. The implementation of the quota system has increased the proportion of women in the national parliament and, as a result, fostered local-level political representation of women. Many women are now looking to women in national parliament as role models to openly engage in grassroots politics. The more involved women are in local politics, the more their representation increases, and as a result, their interests are also taken into consideration. This clearly indicates that the level of descriptive representation and substantive participation are positively correlated.

In countries like Ethiopia, where patriarchal cultures are deeply ingrained, democratic representation is the best way to guarantee meaningful representation for women. As more women enter politics, they will be better able to unite their constituencies and contribute to advancing both their own and those constituencies’ interests. This study’s findings serve as a good example of it. Ethiopia has made significant strides in this area, and other nations should adopt its strategy of first ensuring the numerical representation of women in politics before substantively defending their rights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Muhammed Hamid Muhammed

Muhammed Hamid Muhammad holds the position of Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Social Science at the Department of Political Science and International Studies at Bahir Dar University. Muhammad has taken part in a variety of research projects with a human right, gender equality, and women’s rights theme. The current study is a component of a larger initiative to examine how Ethiopian women participate in local politics.

References

- Alemu, A. (2010). Women Representation in Parliament: A Comparative Analysis: Special Emphasis Given to South African and Ethiopia. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the master of legal studies. Central European University,

- Aubyn, C. (2022). Obstacles to women’s participation in parliament and African politics. http://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.32419.53289.

- Ayele, A. Z. (2014). The politics of sub-national constitutions and local government in Ethiopia, perspectives on federalism. iss. Vol. 6, issue 2.

- Ayele, A. Z., 2022. Local government in Ethiopia: Design problems and their implications, Good Governance Africa (GGA) South Africa. 15 May. 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/zdmq8x Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2446499/local-government-in-ethiopia/3468310/on.

- Ayenew, M. (2007). A rapid assessment of woreda decentralization in Ethiopia. In T. Gebre-Egziabher & A. Taye (Eds.), Decentralization in Ethiopia, a forum for social studies.

- Bari, F. (2005) Women’s political participation: Issues and challenges, EGM/WPD-EE/2005/EP.12.

- Black, W. L. (2013). Methods for analyzing and measuring group deliberation in sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures, and analytical techniques L. Holbert and P.Bucy, (Ed). Routledge.

- Crawford, E. (2020). Achieving sustainable development goals 5 and 6: The case for gender-transformative water programmes.

- Creswell, W. J. (2003). Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (second ed.). Sage publications.

- Dahlerup, D. (1988). From a small to a large minority: Women in Scandinavian politics. Scandinavian Political Studies, 11(4), 275–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.1988.tb00372.x

- Diemer, M. A. (2012). Fostering marginalized youths’ political participation: Longitudinal roles of parental political socialization and youth sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 246–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9495-9

- EGM/EPDM. (2005). Equal participation of women and men in decision-making processes, with particular emphasis on political participation and leadership. United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW), Report of the Expert Group Meeting Addis-Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Falch, Å. (2010). Women’s political participation and influence in post‐conflict Burundi and Nepal. Peace Research Institute.

- Fearon, J. D. (1998). Deliberation as discussion. In J. Elster, (Ed.), Deliberative Democracy. (pp. 44–68). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175005.004

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). (2019). (Rep.). Fifth national report on progress made in the implementation of the Beijing declaration and platform for action (Beijing +25). https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/CSW/64/National-reviews/Ethiopia.pdf

- Fogera Woreda Council Guideline, Prepared by the woreda, 2013.

- Holli, A. M. (2012). Does gender have an effect on the selection of experts by parliamentary standing committees? A critical test of “Critical” concepts. Politics & Gender, 8(3), 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X12000347

- Huntington, S. P., & Nelson, M. J. (1976). No easy choice: Political participation in developing countries. Harvard University Center for International Affairs, Harvard University Press.

- Kanter, R. M. (1977). The impact of hierarchical structures on the work behavior of women and men. Social Problems, 23(4), 425–430. https://doi.org/10.2307/799852

- Khan, R. M. (2010). Nature and Extent of Women Participation in Union Perished in Bangladesh: Prospects and Challenges, qualitative study of three Union parishads. Master thesis for in partial fulfillment of master of philosophy in public administration, University of Bergen.

- Kurebwa, J., & Ndlovu, S. (2017). The critical mass theory and quota systems debate. International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications, 1(1), 48–55.

- Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes. The Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647821

- Midekssa, B. (2012). Women’s political empowerment in Ethiopia. International Conference of Ethiopian Women in the Diaspora. https://www.ned.org/wpcontent/uploads/Womens%20Political%20Empowerment%20in%20Ethiopia.pdf

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development of Ethiopia (MoFED). (2010). Ethiopia: 2010 MDGs report-trends and prospects for meeting MDGs by 2015.

- Okock, O., & Asfaw, M. (2014). Assessment of gender equality in Ethiopia: The position of Ethiopian women’s political representation from the world, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Africa. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization, 28, Online. www.iiste.org

- Oliver, P., Marwell, G., & Teixeira, R. (1985). A Theory of the critical mass. Interdependence, group heterogeneity, and the production of collective action. The American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 522–56. (November 1985) The University of Chicago. https://doi.org/10.1086/228313

- Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage.

- Pitkin, H. F. (1972). The concept of representation. University of California.

- Power, J. T. (1987). The masses and the critical mass: A strategic choice model of the transition to democracy in Brazil. A paper prepared for the panel on“Demands for Change and Government Response in Brazil,” VII Student Conference on Latin America, Institute for Latin American Studies, theUniversity of Texas at Austin

- Riley, C. E., Griffin, C., & Morey, Y. (2010). The case for ‘everyday politics’: Evaluating neo-tribal theory as a way to understand alternative forms of political participation, using electronic dance music culture as an example. Sociology, 44(2), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038509357206

- Rooke, P. J. (1972). Women’s Rights: The way land documental history service. Lynne Rienne Publishers.

- Sarah, C., & Krook, L. M. (2008). Critical mass theory and women’s political representation. Political Studies, 56(3), 725–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00712.x

- Shaffo, A. C. (2010). Gender and Ethiopian Politics: The Case of Birtukan Midekesa. A master’s thesis was submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of master’s in gender studies. Central European University,

- Uhlaner, C. J. (2015). Politics and participation. In J. D. Wright, International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 504–508). University of Central FloridaElsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.93086-1

- UN Women. (2020). Visualizing the data: Women’s representation in society. UN Women – Headquarters. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/multimedia/2020/2/infographic-visualizing-the-data-womens-representation

- Verba, S., & Nie, N. H. (1991). Participation in America: Political democracy and social equality. The University of Chicago Press.