Abstract

Using an experiential risk perception approach, this study examines public’s perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccination in Indonesia and proposes a model of risk communication that enables public’s participation and empowerment in risk management. This study involved those who have experienced COVID-19 vaccination in Indonesia. Based on an online survey, this study found that risk perception was not only about calculation based on scientific information but also about public experiences and beliefs. This study also found that health personnel was associated with scientific explanations about vaccine, while the government was associated with risk management governance. Following these findings, this study proposes a risk communication model that treats the public as a partner of the risk managing institutions. Incorporating the four functions of risk communication: [1] the enlightenment; [2] the trust-building; [3] the participative, and [4] the behavioural change, the model suggests interactive and participatory process involving an equal measure of listening and telling as well as a change from informing to partnering. Risk communication here is an empowering process through which the public can share what they think, how they feel, what they want and how they can achieve it to reduce the risks.

Given the multifaceted effects of COVID-19 and its alarming consequences, risk communication is a key component of public health intervention to assist public in making a risk-based decision (Heydari et al., Citation2021; Renn, Citation2009; Varghese et al., Citation2021). This is a dynamic and interactive process involving exchanges of multiple messages about the nature of risk and other messages that express concerns, opinions, or reaction to risk messages or to legal or institutional arrangements for risk management (Sellnow et al., Citation2009). Achieving an effective risk communication, however, is quite challenging. First, the word “risk” has so many different meanings. Two dominant views are at play in defining “risk” (Dryhurst et al., Citation2020; European Food Safety et al., Citation2021; Heath & O’Hair, Citation2010; Slovic & Weber, Citation2002; Turner et al., Citation2011). One relies heavily on scientific methodologies and probabilistic calculations. The other one is determined by multiple factors other than statistical calculations of risk. This is more subjective, based on effects that risky outcome distributions have on the people who experience them. Second, there is a strong technocratic tradition of risk regulation in which expert’s advice has a strong role in public policy and the role of citizen deliberation and participation is limited (Boholm, Citation2019). The role of science continues to be dominant and experts hold a privileged position, while public opinion tends to be perceived as irrational and emotional. An excessive reliance on science makes it difficult to communicate comprehensible messages to the public. Third, industries and governments historically ignored the public in matters of risk, as their aim is to protect the public, rather than involve them in the process (Boholm, Citation2019; Infanti et al., Citation2013). Meanwhile, to be effective, risk communication should involve the public as the actor, who makes risk-based decision.

1. Research questions and aims

With these challenges, finding a common language in risk communication, accordingly, requires a good understanding of how publics perceive risks and how to incorporate their perceptions into risk management initiative. This study examines public’s perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccination in Indonesia and proposes a model of risk communication that enables public’s participation and empowerment in risk management. This study is conducted to address the following research questions:

RQ1:

How do publics perceive COVID-19 vaccination?

RQ2:

What kind of risk communication model that facilitates an interactive and participatory process in public health communication?

Using an experiential risk perception approach, this study offers an empirical evidence on publics’ perceptions and their implication to the risk communication design. Experiential risk perception is adopted to understand their rapid judgments made by integrating deliberative and affective information resulted from their experiential processing (Ferrer et al., Citation2016, Citation2018). This study views risks as socially negotiated based on people’s experiences, values, and trust in institutions (Rickard, Citation2019). This study involved those who have experienced COVID-19 vaccination in Indonesia. Their experiences help them to interpret the situation as more concrete and closer to themselves, and accordingly reinforce their construction of risk perceptions. By understanding publics’ perceptions, this study proposes a risk communication model that facilitates an interactive and participatory process in which sources and receivers negotiate meanings they derive from the exchange of information.

This study is crucial to help risk managing institutions to identify points of conflict and doubt, as well as to diagnose lack of trust and credibility. This study argues that it is the aftermath of experience that significantly shapes, transforms, and influences how people perceive risk and the risk management institution. Even though COVID-19 threats are decreasing, public’s risk perception will keep continuing. Without knowing the concerns of the public, risk communication will not succeed. This study, accordingly, can assist risk managing institutions in designing a more effective risk communication.

2. Literature review

2.1. Debates in risk communication

In line with the two perspectives in defining risks, this study identifies four evolutionary stages of risk communication process (Covello & Sandman, Citation2001). The first and second stage of risk communication follow the perspective that views risks as the calculation of the perceived probability of negative consequences of a hazard occurring and the perceived magnitude of those consequences (Slovic & Weber, Citation2002). Within this perspective, people assess the positive and negative impacts of the vaccine, so that they can have healthier lives. Risk communication, accordingly, is about providing people with information aimed at facilitating them to make informed decisions and is designed based on conversations among risk analysts, risk managers, and decision makers. This approach is no longer running when people start to be active and ask more explanation. The second stage, then, focuses on how to explain risk data better, assigning spokesperson, and learn to deal with media people. This approach works better when the hazard is large and the controversy is minimal. Nevertheless, when the hazard is minimum but people are extremely outraged, this approach will not be a good solution. There is a significant paradigm shift in the third stage, which is built around dialogue with the public. Risk policy-makers consider public’s perceptions into their decisions. The fourth stage comes about when the risk institutions fully believe in the third stage and are willing to adopt it as part of their fundamental values and culture. The public is treated as a full partner. The fundamental element of the third and fourth stage is public empowerment to participate in the risk management. This fourth stage, however, is hardly achieved due to power issues. Not all authorities are willing to share their power to maintain their statuesque.

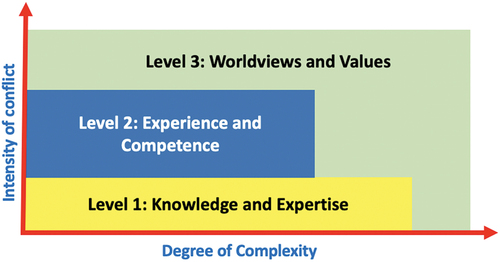

Policy-makers often conceptualize risk as the probability of entangling a disease multiplied by the magnitude of the consequences. Meanwhile, the public constructs their own perception based on how much they know about and understand the risk, and how they feel about them. They develop sensitivity to health risk distinctively. This often leads to risk debates and disagreement. This study addresses three levels of risk debates, which relate to the communication needs for each level (Renn, Citation2009). These levels are as illustrated in Figure

At the first level, risk debates are around information related to knowledge and expertise concerning the issue. In the context of COVID-19 pandemic, this includes debates about the vaccine’s safety, effectiveness, and necessity in order to build vaccine confidence and reduce vaccine hesitancy (Betsch et al., Citation2018; MacDonald, Citation2015).

At the second level, risk debates go around the trustworthiness of the risk managing institutions, whether they have met their official mandates and their performances match public expectations (Freimuth et al., Citation2017; Murtin et al., Citation2018; Renn, Citation2009; Woko et al., Citation2020). This relates to public confidence towards the system that delivers vaccine, including the reliability and competence of the health services and health personnel, as well as the motivations of policy-makers who decide on the need of vaccines (Betsch et al., Citation2018; MacDonald, Citation2015). The government institutions play central elements in representations of disease threat (Wagner-Egger et al., Citation2011; Yeung & Yau, Citation2021). This relates to public trust, which is derived from an assessment of the government institutions’ competence and values (OECD, Citation2017). Competence refers to the ability of the government institutions to deliver to public the services they need at the quality level they expect and involves responsiveness and reliability aspects (OECD, Citation2017). Values refer to the principles that inform and guide the government’s action. This includes integrity, openness, and fairness (OECD, Citation2017). At this second level, the professional image of medical staff has also been considered. Medical personnel still remains as an influential figure to public’s acceptance of vaccines (Mihelj et al., Citation2022; Yaqub et al., Citation2014; Yeung & Yau, Citation2021).

Finally, at the third level of debate, conflict in risk communication is defined along different cultural values (Renn, Citation2009). This study conceptualizes culture as worldview (Hsieh, Citation2011), which is “the fundamental cognitive, affective, and evaluative presuppositions a group of people make about the nature of things, and which they use to order their lives” (Hiebert, Citation2008, p. 15). This provides compass for people to make sense of their experiences and create boundaries of what is right, true, real, ethical, and moral. In the context of health communication, vaccine is also perceived as culture, which involves “the voice of medicine” and “the voice of the lifeworld” (Hsieh, Citation2011; Lo, Citation2010). The voice of medicine is commonly used by health workers to frame and reframe the disease narratives and subjective experiences through the voice of medicine. This is more scientific and technology-centered. Meanwhile, the voice of the lifeworld recognizes how patient’s experiences of health and illness are always situated in their everyday life, encompassing their unique perspectives and understandings. Underprivileged living conditions, lack of access to healthy food, safe drinking water and sanitation, social support networks inadequacy, as well as experience of ethnic and racial discrimination are some of social determinants that influence how different population groups experience the quality of health, health care, and health outcomes within and across nations (R. Ahmed & Mao, Citation2022). This has a sense of grounded-ness in everyday life and might play a role in the assessment of vaccine effectiveness (Yeung & Yau, Citation2021). This relates to the complacency, convenience, collective responsibility, and calculations factors which shape the vaccine hesitancy (Betsch et al., Citation2018; MacDonald, Citation2015). Complacency indicates lack of the perception that the diseases are high risk and that vaccination is necessary. Convenience factor relates to the alignment of vaccination with religious beliefs, geographical accessibility to get vaccine, and economic benefits. Collective responsibility factor reflects individual’s willingness to protect others by getting vaccinated by means of herd immunity, and calculation factor indicates the individual’s engagement in extensive information searching to evaluate the cost and benefit of the risks. Different orientations between the voice of medicine and the voice of the lifeworld are potentials for conflicts (Collins, Citation2019). The suppression of the voice of the lifeworld by the voice of medicine is considered highly problematic, as it often leads to distorted communication or inappropriate treatment plans.

2.2. Incorporating culture into risk communication

This study argues that public perceptions on the risks of COVID-19 do not exist independent of their minds and culture. Risks are subjective construct that are influenced by cognitive, emotional, social, cultural, and individual variation. The question is thus how to incorporate culture into risk communication model and practices?

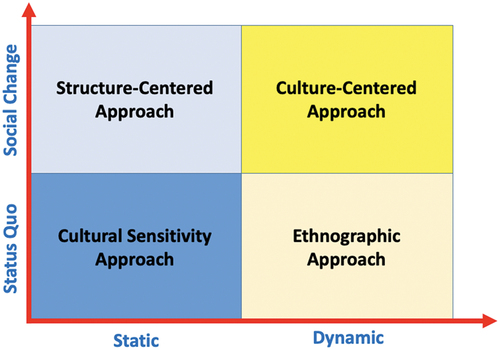

Two dialectical tensions are drawn to understand the dynamic of risk communication for public health and culture, i.e. [1] the role of communication, whether towards social change versus statuesque and [2] the conceptualization of culture as static versus dynamic, as shown in Figure (Dutta & Basu, Citation2011).

The cultural sensitivity approach incorporates public’s cultural characteristics into the design, delivery, and evaluation of the communication messages. This approach is a widely used approach in public health communication but has been criticized for maintaining status quo of risk institutions who set the agenda of risk communication and evaluate it based on criteria they developed. The structure-centered approach examines communication infrastructures, community characteristics, participatory resources, and community capacities in order to understand the role of structure in shaping risk communication processes, and to develop processes of social change. This focuses on ensuring targeted public gains access to the information needed. In these approaches, culture is treated as an aggregate of characteristics, and the emphasis is on working with the characteristics to develop risk communication. Meanwhile, the ethnographic and culture-centered approaches treat culture as transformative and contextually situated. The ethnographic approach focuses on understanding the ways in which risk meanings are constituted and negotiated. The culture-centered approach emphasizes the development of participatory processes and platforms for listening to the voices of the local cultural communities.

3. Methods

3.1. Research design

Based on the literature review, the dimensions and indicators of the risk perception are developed by combining the concept of risk debates (Renn, Citation2009) and the 5Cs factors of vaccine hesitancy vaccines (Betsch et al., Citation2018), as shown in Table .

Table 1. Research design

3.2. Research method

To understand public perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccination (RQ1), this study adopts a quantitative descriptive approach to explain the phenomenon by using numbers that describe risk perceptions. This study conducted online survey towards the targeted population, i.e. the six priority target groups of vaccine recipients (Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republic Indonesia, Citation2020). The respondents were asked to rate from score 1 for the lowest to score 5 for the highest for each indicator. The questionnaire was reliable (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.878) with a significant validity test result (r ≥ 0.325, 5% significance). Using a frequency distribution table, the data were presented to describe the rate of risk perception for each dimension.

There were 437 respondents participated in this study as shown in Table , from four provinces with the highest numbers of COVID-19 patients in 2021 and three strategic business provinces in Indonesia. Since this study focuses on experiential risk perception approach, all respondents must at least receive the first vaccine.

Table 2. List of respondents based on six priority target groups

4. Findings

The findings are described based on each level of risk debate. The first level of risk debate focuses on risk perception towards the vaccine effectivity, necessity, and safety, as shown in Table .

Table 3. Level 1: Knowledge and expertise

From level 1 (low) until 5 (high), the result shows that the level of confidence in the vaccine is high (average means = 4.15). Public’s confidence in effectiveness, necessity, and safety shows a very good result.

The second level of risk debate relates to the trust to risk institutions. In the case of COVID-19, where everything was unpredictable, the government institution played an important role to manage the virus threat. The level of government’s competency was also measured. This includes public confidence towards the system that delivers the vaccination (Table ) and the health personnel (Table ).

Table 4. Level 2: Confidence towards the system that delivers the vaccination

Table 5. Level 2: Confidence towards health personnel

The results show that the level of confidence in the system that delivers the vaccination is high (average mean = 4.04), meanwhile the confidence in the health professional is even higher (average means = 4.12). The lowest level of confidence was shown on the aspect of scheduling of the vaccine (means = 3.86) and also selection of the vaccines (means = 3.89).

The third level of debate examines the public’s worldview and values, which affect their sense of the COVID-19 vaccination based on their own experiences. The convenience, collective responsibility, calculation, and complacency factors reflect the participants’ worldviews about the vaccine, as shown in Table .

Table 6. Level 3: Public worldviews

The respondents’ rate towards worldviews and values has the lowest mean (average mean = 3.82) compared to the other levels’ risk perception. The perceived risk of the disease was rated as the smallest (mean = 2.80). Meanwhile, the geographical accessibility got the highest rate (mean = 4.29).

Finally, the findings can be summarized as shown in Table .

Table 7. Summary of the findings

5. Discussion

5.1. ‘The voice of medicine’ and ‘the voice of the lifeworld’

The findings show that at the first level of risk debate, the participants have a high rate (M = 4,16) of confidence in the effectiveness, necessity, and safety of vaccines. With these results, it is unlikely that this condition will lead to a debate about factual knowledge of the vaccine between public and risk managing institutions. The rationality is that the more that can be understood about the risk in a scientific and management sense, the more likely that something constructive can be done, including communicating about the risk. Nevertheless, this study argues that the findings might not directly lead to vaccine acceptance as thinking through the benefits or risks of a vaccine requires a lot of effort, especially if individuals have little experience or knowledge of the issue. To fully accept the vaccination, individuals tend to rely on societal consensus about the value, utility, and safety of science, as well as observe others’ attitudes and behaviors to determine what is normal and accepted (Sturgis et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, it is important to look beyond individual-level of vaccine confidence but also to incorporate a consideration of how trust or mistrust of science are constructed and maintained in different social contexts.

This study also shows a high rate of the convenience factor (M = 4,14), which relates to the alignment of vaccination with religious beliefs, geographical accessibility to get vaccine, and economic benefits. Physical access and affordability to get vaccine have become significant concern for public, especially for those who live in rural area. In Muslim-majority countries, including Indonesia, Islamic jurisprudence may influence vaccine acceptance (A. Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Mardian et al., Citation2021; Wong et al., Citation2022). There is a major public concern among Muslims with regard to the halal status of vaccine. Previous studies (Costa et al., Citation2020; Tlale et al., Citation2022) have shown that the religion affects health outcomes through direct influences on beliefs and values

A high rate of collective responsibility factor (M = 4,06) reflects individual’s willingness to protect others by getting vaccinated by means of herd immunity. This is very common in collectivist society, like Indonesia, to embrace communal orientation and empathy. In addition, there is also a high rate of calculation factor (M = 4,19), which indicates the individual’s engagement in extensive information searching to evaluate the cost and benefit of the risks. The vaccine attitudes resulting from their calculation depend on the information sources they used.

Unlike the other previous factors, this study shows a medium rate of complacency factor (M = 3,00). Complacency indicates lack of perception that diseases are highly risk and that vaccination is necessary. Individual with high complacency does not perceiving COVID-19 as high risk. They perceive COVID-19 as another type of influenza and believe in their own immune system to cure it.

The convenience, collective responsibility, calculation, and complacency factors reflect the participants’ worldviews about the vaccine. Unlike confidence to the vaccine, which is mostly derived from scientific information about the vaccine, the worldviews here represent their “voices of the lifeworld” (Hsieh, Citation2011), which are resulted from their experiences in accessing the vaccine, building social relationships, economic motive, beliefs and general knowledge about health and vaccine. These voices recognize how public’s experiences of health are always situated in their everyday life, embracing their unique perspectives and understandings.

Risk managers, on the other hand, commonly speak using the voice of medicine as well as frame and reframe the patient’s health experiences based on technical evidences rather than information from the patients. There is a strong tendency for them to re-frame higher level risk debate into lower level one to focus the discussion on technical evidence in which they are eloquent (Boholm, Citation2019). The public is forced to use first level (factual) arguments to justify their value concerns. This is mostly done to define and control their scope of work as well as to maintain the health system. In the case of pandemic like COVID-19, which can significantly increase morbidity and mortality over a wide geographic area and cause significant economic, social, and political disruptions, it is crucial to understand the public’s lifeworld. The hesitancy for COVID-19 vaccines is unlikely to be due merely to a lack of evidence regarding the vaccines’ safety. This goes beyond evidence-based factors (McClaran et al., Citation2022). When risk managers perceive public worldviews as irrational, this can lead to the disappointment and public distrust in the risk managing institutions.

5.2. Risk managing institutions and public trust

Compared to the other risk levels, the study shows the lowest rate on the second-level debate, which relates to the confidence in risk institutions’ competence to deal with risks and their trustworthiness. On the one hand, the respondents consider health personnel involved in the vaccination process as competent, professional, and reliable. The respondents are also confident about the vaccine’s availability and government’s motivation in conducting COVID-19 vaccination program. On the other hand, this study shows lower confidence rates in the process of selecting COVID-19 vaccine brands (M = 3,89) and scheduling the periodization of COVID-19 vaccine administration (M = 3,86) by the government. Meanwhile, the government’s capacity to manage the challenges of the procurement and vaccination process is an important element of public trust.

Public trust here is inseparable from the aspect of confidence. Trust is defined as a person’s belief that another person or institution will act in accordance with one’s expectations about the positive behavior of others (OECD, Citation2017). In this study, it is the openness and reliability aspects of the government that still raise public doubts. The existence of various brands of vaccines used by the government, on the one hand, provides various choices for the public, but on the other hand, raises many questions. The public expects the government’s openness regarding the vaccine selection process. The reliability aspect here is related to scheduling the periodization of the COVID-19 vaccine administration.

Public trust in risk management is commonly shaped by perceived shared values, which are learned via stories or narratives that institutions tell (McComas, Citation2006). In Indonesia, public often experiences the uncertainty of the vaccination schedule and its availability, which leads to low level of trust in the government performance. Building trust here requires far more than applying guidelines during a crisis situation. Instead, the risk institutions, i.e. the government, must commit to policies of openness and transparency in their general operations.

5.3. Implications towards risk communication

This study suggests two significant findings that contribute to a risk communication model. First, participants show confidence in vaccine’s effectiveness, safety, and necessity, while at the same time, equally embraces their worldviews associated with COVID-19 vaccination decision. This suggests that risk perception is not only about calculation based on scientific information but also about their experiences and beliefs. Second, with regards to their perceptions towards risk institutions, this study shows high confidence towards the professionalism, competence, and reliability of health personnel. Nevertheless, participants indicate doubt towards government openness and reliability regarding the vaccination system. This suggests that these two factors of risk managing institutions are perceived and associated with different public expectations. Health personnel are associated with scientific explanations about vaccine. Meanwhile, the government is associated with risk management governance.

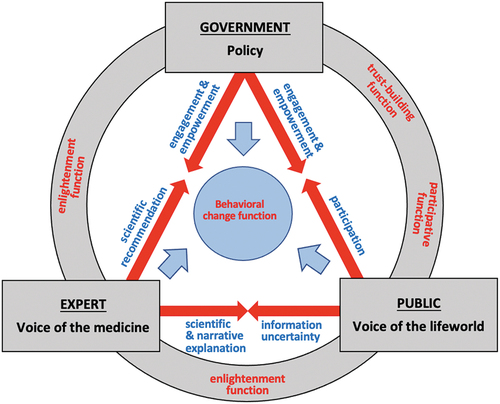

Based on the findings, this study proposes risk communication model that treats the public as a partner of the risk managing institutions, as shown in Figure

This proposed model highlights the importance of interactive communication among all parties, i.e. the government, the experts, and the public, and acknowledges the three level of risk debates, i.e. [1] knowledge and expertise, [2] experience and competence, and [3] worldviews and values (Renn, Citation2009). The model also elaborates four essential functions of risk communication in public health: [1] enlightenment function to advance risk awareness and understanding about the vaccine, [2] participative function to provide procedures for dialogue and other alternative methods for a more participative risk management and regulation, [3] trust-building function to promote trust and credibility towards risk managing institutions, and [4] behavioral change function to promote health-protective behaviors among individuals, communities, and institutions (Renn, Citation2009).

5.3.1. The enlightenment function

The enlightenment function aims to ensure all receivers of risk communication messages understand the content and thus improve their knowledge about the risks communicated. The experts hold a significant role for providing valid information about risks to reduce information uncertainty. On the one hand, the experts are responsible for providing scientific data and evidence-based recommendations to the government, who are in charge for communicating assessments of potential hazards and their management to affected groups, stakeholders, and general public. The experts here focus their efforts on furthering scientific understanding of the disease and offering means for evaluating and judging the distribution of risk occurrence and magnitude throughout society. On the other hand, the government needs to empower the experts to work on comprehensive and extensive studies on the disease and its risks (Zhang et al., Citation2020), as they mostly rely on science and expert knowledge as the foundation of risk communication (Boholm, Citation2019). Nevertheless, the experts need to be independence from political elites and interests, as this is likely to play a key role in shaping people’s assessment of expert trustworthiness (Mihelj et al., Citation2022).

This study suggests the need to combine scientific and narrative approaches in designing messages to the public. The narrative approach is not just telling stories about the disease and vaccine, but stories with purposes and consequences that are aligned with public’s experiences (Lundgren & McMakin, Citation2018; Mansnerus, Citation2012; Sharf et al., Citation2011). This approach enables the experts and other risk managing institutions to connect scientific data with public worldviews and build trusting relationship that can create support for future health information processing (Ledford et al., Citation2022).

5.3.2. The trust-building function

Trust in risk managing institutions is significant to minimize unnecessary fear and to enhance public adherence to the public health recommendations (Ahn et al., Citation2021; Holroyd et al., Citation2021; Ledford et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2022; Quinn et al., Citation2013). Openness, transparency, responsiveness, and reliability are key words in the efforts to gain public trust (OECD, Citation2017). Delayed and non-transparent information disclosure can cause breakdown in trust in government as the information source (Zhang et al., Citation2020). When the risk managing institutions openly discuss risks and possible preventive strategies, they are likely perceived as more trustworthy (Conchie & Burns, Citation2008). Openness or transparency in risk communication is recognized by most risk practitioners as crucial at least in principle (Boholm, Citation2019) and leads to public empowerment to directly or indirectly make more informed decisions (Way et al., Citation2016). In spite of this, in practice this key norm does not provide an easy solution for restoring trust and legitimacy as this may also lead to an increase in risky behavior on the part of the public (Bouder, Citation2015), such as rejecting the vaccine. A well thought through risk communication approach will be the key to achieve successful transparency initiatives. Trust grows with the experience of trustworthiness and involves a long-term and continuous process. Thus, risk communication process is suggested to integrate the accessibility and openness of risk information, the timing and frequency of communication, and the strategies dealing with uncertainties, which can be facilitated through public engagement.

5.3.3. The participative function

The government, who is responsible for enacting the public health policy, needs to actively engage with the public to understand and respond to public’s expectations. Understanding the perspectives of the people for whom vaccination services are intended, and their engagement with the issue, is as important as the information that experts want to communicate. This model suggests risk communication as an interactive process involving an equal measure of listening and telling as well as the change from informing to partnering. This is in line with the more recent participatory orientation of government communication (Canel & Luoma‐Aho, Citation2019; Yudarwati & Gregory, Citation2022) and the culture-centered approach that emphasizes the development of participatory processes and platforms for listening to the voices of the local cultural communities (Dutta & Basu, Citation2011; Dutta et al., Citation2022) as well as for developing culturally tailored prevention messages (Zhou et al., Citation2022; Bates et al., Citation2022).

5.3.4. The behavioral change function

Finally, risk communication should be able to assist the public to make informed decisions and behave in ways that will best help them avoid risks and uncertainty. As shown in the model, this function is resulted from the combined efforts of three other functions. Risk communication and public engagement are integral to the success because it is not the risk managing institutions only, but also the public, who determine which hazards the public care about and how they deal with them. There is a transformation here, as risk communication moves from being based on informing, with risk managing institutions enacting the “top down” approach, through to consulting and involving in which public considerations are heard, and eventually partnering in which risk managing institutions and the public generate ideas and solutions together (Yudarwati & Gregory, Citation2022). Risk communication towards vaccine acceptance should be framed as a social movement, initiated at the grassroots involving public and multisectoral engagement (Larson et al., Citation2020). The feeling of being empowered and co-ownerships towards risk management process are likely to contribute to the public informed decisions.

6. Conclusion

This study shows a high-rate vaccine confidence as well as worldviews associated with vaccination decision. Even though public confidence towards health personnel is high, this study indicates public’s doubts towards government’s performance in managing vaccination. This suggests that individuals’ knowledge about vaccine’s effectiveness and safety is not the only factor that leads to vaccine acceptance, but also the extent of trust or mistrust towards risk managing institutions and vaccination at their societal level. Individuals develop vaccine literacy when they understand the content and the processes needed to access and get vaccinated using their own language and relevant to their context. Risk communication, accordingly, should be public-oriented and in the form of communicative and interactive actions that are context sensitive and meaning-oriented, with the aim to consensus-building that incorporate public’s voice of the lifeworld.

The proposed model in this study incorporates the four functions of risk communication: [1] the enlightenment function to ensure all receivers of the message can understand the content and so improve their knowledge about the risks communicated; [2] the trust-building function in the relationship among all three main actors; (3) the participative function to ensure all affected parties are included in the risk management process, and [4] the behavioural change function by persuading the receivers to change their behaviour towards a specific risk. To do so, the model implies the importance of switching from the mechanical top-down perspective, which focuses on the problem-solving approach towards vaccine acceptance, to the living human system perspective, which emphasizes interactive and participative relationships among three main actors, i.e. the government, the experts, and the public. This emphasizes the importance of the process of communication as well as outcomes and treats the public as having agency rather than as object of risk communication. Risk communication here is an empowering process through which the public can share what they think, how they feel, what they want and how they can achieve it to reduce the risks. Narrative approach is suggested to connect the language of medicine with the language of the lifeworld as well as to empower the public to understand and construct the risks towards their well-informed decisions.

This study acknowledges the limitation that the proposed model has not been tested and derived from a study in collectivist society, which may not be generalizable to more individualistic society. A further study exploring the process of risk communication involving public engagement in public health context is recommended to examine the proposed model that allows joint decision-making and co-ownership in the risk management process between risk managing institutions and publics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to fully acknowledge the support of Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta and Tempo Data Science, Indonesia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gregoria A. Yudarwati

Gregoria A. Yudarwati is an Associate Professor at Communications Department, Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta. Her research areas are in public relations, risk communication, community engagement and sustainability communication.

Ignatius A. Putranto

Ignatius A. Putranto is a senior lecturer at the Communications School, Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta. His research areas are in advertising, creative industry and entrepreneurship.

Ina N. Ratriyana

Ina Nur Ratriyana is a lecturer at the Communications School, Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta. Her research interests are related to the intersection of local branding, youth culture, community engagement, and digital media.

Philipus Parera

Philipus Parera is a senior journalist at Tempo Magazine and the Director of Tempo Data Science, Indonesia.

References

- Ahmed, A., Lee, K. S., Bukhsh, A., Al-Worafi, Y. M., Sarker, M. M. R., Ming, L. C., & Khan, T. M. (2018). Outbreak of vaccine-preventable diseases in Muslim majority countries. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 11(2), 153–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.007

- Ahmed, R., & Mao, Y. (2022). Communication Research on Health Disparities and Coping Strategies in COVID-19 Related Crises. Health Communication, 37(12), 1455–1456. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2111633

- Ahn, J., Kim, H. K., Kahlor, L. A., Atkinson, L., & Noh, G.-Y. (2021). The Impact of Emotion and Government Trust on Individuals’ Risk Information Seeking and Avoidance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-country Comparison. Journal of Health Communication, 26(10), 728–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1999348

- Bates, B. R., Villegas-Botero, A., Costales, J. A., Moncayo, A. L., Tami, A., Carvajal, A., & Grijalva, M. J. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Three Latin American Countries: Reasons Given for Not Becoming Vaccinated in Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. Health Communication, 37(12), 1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2035943

- Betsch, C., Schmid, P., Heinemeier, D., Korn, L., Holtmann, C., Bohm, R., & Angelillo, I. F. (2018). Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLos One, 13(12), e0208601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208601

- Boholm, Å. (2019). Risk Communication as Government Agency Organizational Practice. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 39(8), 1695–1707. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13302

- Bouder, F. (2015). Risk communication of vaccines: Challenges in the post-trust environment. Current Drug Safety, 10(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.2174/157488631001150407103916

- Canel, M. J., & Luoma‐Aho, V. (2019). Public sector communication : Closing gaps between citizens and public organizations (1st edition. ed.). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119135630

- Collins, V. (2019). Conflicts of Patient-Caregiver Communication and Some Workable Solutions. Harvard Public Health Review, 23(23), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.54111/0001/W5

- Conchie, S. M., & Burns, C. (2008). Trust and risk communication in high-risk organizations: A test of principles from social risk research. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 28(1), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01006.x

- Costa, J. C., Weber, A. M., Darmstadt, G. L., Abdalla, S., & Victora, C. G. (2020). Religious affiliation and immunization coverage in 15 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccine, 38(5), 1160–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.024

- Covello, V., & Sandman, P. M. (2001). Risk communication: Evolution and Revolution. In A. Wolbarst (Ed.), Solutions to an Environment in Peril (pp. 164–178). John Hopkins University Press.

- Dryhurst, S., Schneider, C. R., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L. J., Recchia, G., van der Bles, A. M., van der Linden, S. (2020). Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7–8), 994–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193

- Dutta, M. J., & Basu, A. (2011). Culture, Communication, and Health: A Guiding Framework. In T. L. T. ompson, R. Parrott, & J. F. Nussbaum (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication (pp. 320–334). Routledge.

- Dutta, M. J., Jayan, P., Elers, P., Elers, C., Rahman, M. M., & Pokaia, V. (2022). Receiving Healthcare Amidst Poverty During the COVID-19 Lockdowns: A Culture-Centered Interrogation. Health Communication, 37(12), 1503–1509. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2111634

- European Food Safety, A., Maxim, L., Mazzocchi, M., Van den Broucke, S., Zollo, F., Robinson, T., Smith, A. (2021). Technical assistance in the field of risk communication. EFSA Journal European Food Safety Authority, 19(4), e06574–e06574. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6574

- Ferrer, R. A., Klein, W. M. P., Avishai, A., Jones, K., Villegas, M., Sheeran, P., & Ozakinci, G. (2018). When does risk perception predict protection motivation for health threats? A person-by-situation analysis. PLoS One, 13(3), e0191994. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191994

- Ferrer, R. A., Klein, W. M., Persoskie, A., Avishai-Yitshak, A., & Sheeran, P. (2016). The Tripartite Model of Risk Perception (TRIRISK): Distinguishing Deliberative, Affective, and Experiential Components of Perceived Risk. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 50(5), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9790-z

- Freimuth, V. S., Jamison, A. M., An, J., Hancock, G. R., & Quinn, S. C. (2017). Determinants of trust in the flu vaccine for African Americans and Whites. Social Science & Medicine, 193, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.001

- Heath, R. L., & O’Hair, D. H. (2010). The significance of crisis and risk communication. In R. L. Heath & D. H. O’Hair (Eds.), Handbook of Risk and Crisis Communication (pp. 5–30). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003070726-2

- Heydari, S. T., Zarei, L., Sadati, A. K., Moradi, N., Akbari, M., Mehralian, G., & Lankarani, K. B. (2021). The effect of risk communication on preventive and protective Behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Mediating role of risk perception. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10125-5

- Hiebert, P. G. (2008). Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change. Baker Academic.

- Holroyd, T. A., Limaye, R. J., Gerber, J. E., Rimal, R. N., Musci, R. J., Brewer, J., Salmon, D. A. (2021). Development of a Scale to Measure Trust in Public Health Authorities: Prevalence of Trust and Association with Vaccination. Journal of Health Communication, 26(4), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1927259

- Hsieh, E. (2011). Intercultural Health Communication: Rethinking Culture in Health Communication. In T. L. Thompson & N. G. Harrington (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication (pp. 441–455). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003043379-37

- Infanti, J., Sixsmith, J., Barry, M., Núñez-Córdoba, J., Oroviogoicoechea-Ortega, C., & Guillén-Grima, F. (2013). A literature review on effective risk communication for the prevention and control of communicable diseases in Europe. the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

- Larson, H. J., Lee, N., Rabin, K. H., Rauh, L., & Ratzan, S. C. (2020). Building Confidence to CONVINCE. Journal of Health Communication, 25(10), 838–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1884149

- Ledford, C. J. W., Cafferty, L. A., Moore, J. X., Roberts, C., Whisenant, E. B., Garcia Rychtarikova, A., & Seehusen, D. A. (2022). The dynamics of trust and communication in COVID-19 vaccine decision making: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Health Communication, 27(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2022.2028943

- Li, H., Chen, B., Chen, Z., Shi, L., & Su, D. (2022). Americans’ Trust in COVID-19 Information from Governmental Sources in the Trump Era: Individuals’ Adoption of Preventive Measures, and Health Implications. Health Communication, 37(12), 1552–1561. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2074776

- Lo, M. C. (2010). Cultural brokerage: Creating linkages between voices of lifeworld and medicine in cross-cultural clinical settings. Health (London), 14(5), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459309360795

- Lundgren, R. E., & McMakin, A. H. (2018). Risk Communication: A Handbook for Communicating Environmental, Safety, and Health Risks. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- MacDonald, N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

- Mansnerus, E. (2012). Understanding and Governing Public Health Risks by Modeling. In S. Roeser, R. Hillerbrand, P. Sandin, & M. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of Risk Theory: Epistemology, Decision Theory, Ethics and Social Implications of Risk (pp. 213–238). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1433-5_9

- Mardian, Y., Shaw-Shaliba, K., Karyana, M., & Lau, C.-Y. (2021). Sharia (Islamic Law) Perspectives of COVID-19 Vaccines. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fitd.2021.788188

- McClaran, N., Rhodes, N., & Yao, S. X. (2022). Trust and Coping Beliefs Contribute to Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Intention. Health Communication, 37(12), 1457–1464. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2035944

- McComas, K. A. (2006). Defining moments in risk communication research: 1996–2005. Journal of Health Communication, 11(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730500461091

- Mihelj, S., Kondor, K., & Štětka, V. (2022). Establishing Trust in Experts During a Crisis: Expert Trustworthiness and Media Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Science Communication, 44(3), 292–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221100558

- Murtin, F., Fleischer, L., Siegerink, V., Aassve, A., Algan, Y., Boarini, R., Smith, C. (2018). Trust and Its Determinants: Evidence from the Trustlab experiment. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2017). Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust. OECD Public Governance Reviews. OECD Publishing.

- Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republic Indonesia, Public Law. (2020). https://covid19.go.id/storage/app/media/Regulasi/2020/Desember/PMK%20No.%2084%20Th%202020%20ttg%20Pelaksanaan%20Vaksinasi%20Dalam%20Rangka%20Penanggulangan%20COVID-19.pdf

- Quinn, S. C., Parmer, J., Freimuth, V. S., Hilyard, K. M., Musa, D., & Kim, K. H. (2013). Exploring communication, trust in government, and vaccination intention later in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic: Results of a national survey. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science, 11(2), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2012.0048

- Renn, O. (2009). Risk Communication: Insights and Requirements for Designing Successful Communication Programs on Health and Environmental Hazards. In R. L. Heath & D. O’Hair (Eds.), Handbook of risk and crisis communication (pp. 80–98). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003070726-5

- Rickard, L. (2019). Pragmatic and (or) Constitutive? On the Foundations of Contemporary Risk Communication Research. Risk Analysis, 41(3), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13415

- Sellnow, T. L., Ulmer, R. L., Seeger, M. W., & Littlefield, R. S. (2009). Effective Risk Communication a Message-Centered Approach. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79727-4

- Sharf, B. F., Harter, L. M., Yamasaki, J., & Haidet, P. (2011). Narative Turns Epic: Continuing Developments in Health Narrative Scholarship. In T. L. T. ompson, R. Parrott, & J. F. Nussbaum (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication (pp. 36–51). Routledge.

- Slovic, P., & Weber, E. U. (2002). Perception of Risk Posed by Extreme Events. Paper presented at the Risk Management strategies in an Uncertain World,

- Sturgis, P., Brunton-Smith, I., & Jackson, J. (2021). Trust in science, social consensus and vaccine confidence. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(11), 1528–1534. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01115-7

- Tlale, L. B., Gabaitiri, L., Totolo, L. K., Smith, G., Puswane-Katse, O., Ramonna, E., Kolane, S. (2022). Acceptance rate and risk perception towards the COVID-19 vaccine in Botswana. PLoS One, 17(2), e0263375. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263375

- Turner, M., Skubisz, C., & Rimal, R. N. (2011). Theory and Practice in Risk Communication: A Review of the Literature and Visions for the Future. In T. L. Thompson, R. Parrott, & J. F. Nussbaum (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication (2nd ed., pp. 146–164). Routledge.

- Varghese, N. E., Sabat, I., Neumann-Böhme, S., Schreyögg, J., Stargardt, T., Torbica, A., Brouwer, W. (2021). Risk communication during COVID-19: A descriptive study on familiarity with, adherence to and trust in the WHO preventive measures. PLoS One, 16(4), e0250872. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250872

- Wagner-Egger, P., Bangerter, A., Gilles, I., Green, E., Rigaud, D., Krings, F., Clémence, A. (2011). Lay perceptions of collectives at the outbreak of the H1N1 epidemic: Heroes, villains and victims. Public Understanding of Science, 20(4), 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662510393605

- Way, D., Bouder, F., Löfstedt, R., & Evensen, D. (2016). Medicines transparency at the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the new information age: The perspectives of patients. Journal of Risk Research, 19(9), 1185–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1200652

- Woko, C., Siegel, L., & Hornik, R. (2020). An Investigation of Low COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions among Black Americans: The Role of Behavioral Beliefs and Trust in COVID-19 Information Sources. Journal of Health Communication, 25(10), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1864521

- Wong, L. P., Alias, H., Megat Hashim, M. M. A. A., Lee, H. Y., AbuBakar, S., Chung, I., Lin, Y. (2022). Acceptability for COVID-19 vaccination: Perspectives from Muslims. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(5), 2045855. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2045855

- Yaqub, O., Castle-Clarke, S., Sevdalis, N., & Chataway, J. (2014). Attitudes to vaccination: A critical review. Social Science & Medicine, 112, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018

- Yeung, M. W. L., & Yau, A. H. Y. (2021). ‘This year’s vaccine is only 10% effective’: A study of public discourse on vaccine effectiveness in Hong Kong. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 14(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2020.1809316

- Yudarwati, G. A., & Gregory, A. (2022). Improving government communication and empowering rural communities: Combining public relations and development communication approaches. Public Relations Review, 48(3), 102200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102200

- Zhang, L., Li, H., & Chen, K. (2020). Effective Risk Communication for Public Health Emergency: Reflection on the COVID-19 (2019-nCov) Outbreak in Wuhan, China. Healthcare (Basel), 8(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010064

- Zhou, S., Villalobos, J. P., Munoz, A., & Bull, S. (2022). Ethnic Minorities’ Perceptions of COVID-19 Vaccines and Challenges in the Pandemic: A Qualitative Study to Inform COVID-19 Prevention Interventions. Health Communication, 37(12), 1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2093557