?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

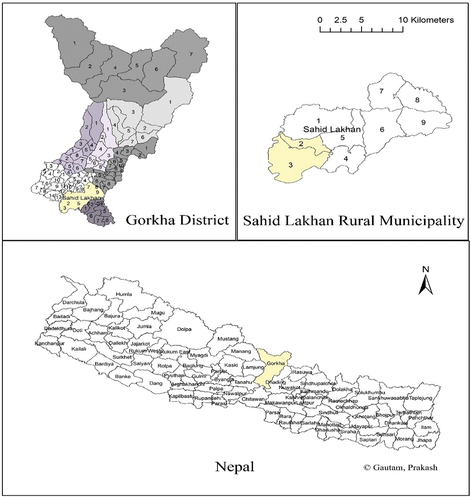

Religious tourism and entrepreneurship are closely interconnected with Nepal’s unique religious history, customs, culture, and tradition. Holy places such as Manakamana temple are central to the success of local entrepreneurs. This study explores the relationship between religious tourism and entrepreneurship in Nepal and investigates the livelihood of local business owners, business sustainability, and the challenges facing tourism-dependent businesses by their business sizes. The study was conducted in the area surrounding Manakamana temple, located in the Shahid Lakhan Rural Municipality ward nos. 2 and 3, Gorkha district, Nepal. A mixed method featuring qualitative and quantitative analyses of primary data was used to produce relevant findings. Among the key findings were that Nepal’s religious places provide an excellent opportunity to develop entrepreneurship that contributes directly to improvements in the health, education, and nutrition of business owners and their families. Using survey and interview results, the author identifies policies and support measures that could/should be adopted by local governments to benefit and encourage local entrepreneurs.

1. Introduction

Prior to the COVID−19 pandemic, travel and tourism were major economic industries, accounting for 10% of worldwide GDP and 6% of total global exports (Behsudi, Citation2020; Rasool et al., Citation2021; UNWTO, Citation2015). According to statistics compiled by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) for 2016 and 2019, approximately 27% of travelers traveled either for religious reasons, to visit friends and family, or for medical treatment (UNWTO, Citation2016, Citation2021).

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), cultural and heritage tourism, which is closely connected to religious tourism, is economically beneficial and a significant accomplishment for the host nation (OECD, Citation2008). Both developed and developing countries benefit from religious tourism. Not surprisingly, it is an essential tool for economic development in Asian countries (OECD, Citation2008). Tourism is a highly fragmented and diverse industry comprising different sectors and dominated by micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, which account for approximately 85% of businesses in OECD countries (OECD, Citation2022).

Religious tourism is the oldest form of tourism and a global trend in the history of religion (Abad Galzacorta et al., Citation2016; Hassan et al., Citation2022; Rinschede, Citation1992). It contributes to preserving the culture and sustainability of people’s livelihoods (Abereijo & Afolabi, Citation2017; Levi & Kocher, Citation2013). Local residents commonly operate their tourist-related businesses in religious or sacred places as entrepreneurs (Gautam, Citation2020; Kaelber, Citation2006). Most of the businesses are small- and medium-sized, and employ a significant number of family members who take advantage of the job opportunities they offer. Thus, religious tourism positively impacts small business income and contributes to poverty reduction (Akinwale & Ogundiran, Citation2014; Kusi et al., Citation2015). However, there are a number of issues affecting religious tourism and entrepreneurship, including risk and uncertainty, marketing, lack of business knowledge, capital, employee management, competitor risk, and livelihood problems.

This study focuses on the case of the Manakamana Temple in Nepal, which is a holy place of Hindu religious groups and a major pilgrimage destination. Manakamana Temple and its surrounding area attract many domestic tourists as well as tourists from India and elsewhere. Non-religious tourists also visit this religious site because of its landscape and beauty (Adhikari, Citation2020; Bleie & Bhattarai, Citation2002). The large number of tourist attractions have both a direct and indirect relationship to the livelihood of local entrepreneurs. Many local entrepreneurs operate small and large businesses in the temple area. For instance, worship (pooja) material shops, photoshops, hotels, restaurants, and souvenir shops can be found. According to the chairperson of ward no. 2, roughly 2000–2500 local people are directly employed in these businesses (Sahid Lakhan Rural Municipality include ward no 2 and 3). In peak season, more than 12,000 pilgrims visit Manakamana daily via cable cars, buses, and jeeps, and on foot.

The yellow-shaded region in Figure shows the research area surrounding the Manakamana temple, which is in wards 2 and 3 of the Shahid Lakhan Rural Municipality, Gorkha district, Nepal. The area is situated in the center of the country, approximately 100 km from the capital city of Kathmandu. The temple area can be reached using the Prithvi highway to Kurintar station, followed by a 10-minute cable car ride from Kurintar to Manakamana. Due to its convenient transportation accessibility, the temple attracts pilgrims from both inside and outside the country (especially Indian pilgrims).

Most of the businesses operating in the Manakamana temple area are run by local residents and serve as a valuable source of income. Such businesses can be started with a relatively small initial investment and have the potential to significantly reduce poverty among local residents (Goodwin, Citation2011). During several festivals and specific periods throughout the year, small businesses around the temple site have the enhanced opportunity to sell their products and services. These businesses include vendors of curios and cultural gifts, guest houses, tea shops, jewelry stores, religious materials stores, handicraft shops, and so on. In addition, the livelihoods of many families depend on the Manakamana market, which produces and delivers vegetables, fruits, and meat products.

Religious tourism is gaining attention worldwide not only as a potentially significant driver of economic development but for achieving a variety of objectives related to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Tomalin et al., Citation2019). Even in developed countries, there is a close relationship between religion and local entrepreneurs, providing insights into social capital and the economic growth of communities (Deller et al., Citation2018). Indeed, religion is widely acknowledged as an important contributor to the sustainability of society (Abereijo & Afolabi, Citation2017; Smidt, Citation2003).

Although there exists historical literature on the various temples, shrines, and heritage sites associated with religious tourism in Nepal, the contributing studies are mainly qualitative in nature. Furthermore, there are few academic articles on religious tourism’s impact and social contributions. Given this research gap, the current study focuses on family health, children’s education, and food costs as livelihood factors that can be linked to religious tourism. The primary hypothesis is that businesses at religious sites positively impact the education of children, affordability of food, and the health of the business owners and their families. This hypothesis is specifically used to assess the impact of businesses operating in the Manakamana temple area.

2. Literature review

2.1. Religious tourism

The concept of religious tourism is used extensively in theory and practice to describe tourism in which the motivation of participants is either partially or totally religious (Rinschede, Citation1992). The destination of religious tourists is typically a holy site, pilgrimage site, or religious heritage site (Nolan & Nolan, Citation1992; Shinde, Citation2010; Smith, Citation1992). Such sites symbolize the distinct cultures and traditions of the cities or regions in which they are located (Singh & Rana, Citation2016). These sites have been described as awe-inspiring, peaceful spaces that stimulate thought and meditation and develop respect for religious principles (Levi & Kocher, Citation2013). Religious sites associated with nature, cultures and architecture may also help visitors realize the interconnection of humans and the environment (Verschuuren, Citation2007).

The preservation and development of religious culture have far-reaching significance for both religious and non-religious people. Moreover, religious places have a strong tendency in archaeology to focus on ritual practice rather than holistic understanding (Gilchrist, Citation2020; Thouki, Citation2019).

From the perspective of religious site conservation, religious tourism can serve as a source of funding for the preservation of natural landscapes and ancient cities. It can increase local and visitor understanding of conservation concerns while discouraging residents from unsustainable livelihoods (Borges et al., Citation2011). Religious visitors contribute directly to economic development, generating new job possibilities and boosting local economies (H. L. Ghimire, Citation2019; Levi & Kocher, Citation2009). Preserved religious places allow communities to deepen their knowledge of their culture and traditions, and the expansion of religious tourism can help ensure the care and protection of these places and their attractions (Simone-Charteris & Boyd, Citation2010).

Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation categorize tourists by their primary motivation for visiting: holiday or pleasure, pilgrimage, trekking and mountaineering, and other. According to tourist statistics, the holiday or pleasure category attracted the greatest number of visitors to Nepal in 2019, while the pilgrimage category comprised the second largest group (MoCTCA, Citation2020). Pilgrimage tourism is a combination of traditional shrine tours and cultural travels arranged, organized, and coordinated by religious groups or for religious objectives (Gautam, Citation2021). Digance (Citation2003) and Tsironis (Citation2022) suggested that pilgrimage and religious tourism are sometimes assumed to have the same meaning (Digance, Citation2003; Tsironis, Citation2022). However, not all religious tourism involves a pilgrimage.

The goal of sustainable tourism at religious sites is to maintain the sanctity of the site while enabling community use and tourism to continue. This requires knowledge of how individuals interpret the sacredness of a site (Levi & Kocher, Citation2013). Holy places are used for more than simply religious purposes; for instance, Buddhist temple complexes are used for the Sangha (community of monks) and communal objectives such as educational and social services (Levi & Kocher, Citation2013).

According to Fleischer (Citation2000), pilgrims and other religious visitors are passionate consumers of religious goods, and the economic benefits of religious tourism outweigh those associated with other market sectors. Furthermore, religious tourism may help to maintain and preserve religious and cultural heritage places and attractions (Fleischer, Citation2000). It has been said that people’s perceptions of religious sites are influenced by their personal and cultural origins (Shackley, Citation2002). Religious visitors experience a “feeling of God’s presence” and a respect for the site’s spiritual values. At the same time, non-religious tourists find sacred sites to be spiritually vibrant places of peace, tranquility, and inspiration (Sharpley & Sundaram, Citation2005).

2.2. Tourism and entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is one aspect of human behavior, with an input and an output side. On the one hand, entrepreneurial behavior requires entrepreneurial skills and attributes; on the other hand, it requires involvement in the competitive process (Wennekers & Thurik, Citation1999). Furthermore, it has been argued that entrepreneurship is not an occupation and that entrepreneurs do not belong to a well-defined occupational class. In some cases, entrepreneurs may demonstrate their entrepreneurship only during a specific stage of their career or only in a particular aspect of their activities.

Production-induced entrepreneurship is business-oriented, whereas consumption-induced entrepreneurship is concerned mainly with lifestyle factors (Getz & Peterson, Citation2005). Economically focused entrepreneurs may have lifestyle objectives and preferences, but they also see profit as a survival baseline (Getz & Carlsen, Citation2000). Noneconomic motivations may provide unexpected effects that do not stifle or hinder progress but create new economic chances to interact with specialized customers (Ateljevic & Doorne, Citation2000). In terms of tourism in a traditional and agricultural economy, small-scale and family-centered rural tourist enterprise tends to belong to the growth and prove to be beneficial (McGehee & Kim, Citation2004).

Tourism entrepreneurs are the persona cause of tourism development, and the quantity and quality of a community’s supply of tourism entrepreneurs will largely determine the size and shape of its tourism destination (Koh & Hatten, Citation2002). Tourism development is a reflection of both urbanization and counter-urbanization trends. The urbanization of rural and peri-urban areas increases employment and business prospects (Zhou & Chan, Citation2019). Zhou and Chan (Citation2019) suggest that the involvement of entrepreneurs and employees identifies them as pioneers in tourism development (Zhou & Chan, Citation2019). The social components of religion are another motivating factor in entrepreneurship; social networks, both professional and personal, are influential in creating new business ventures (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003).

H. L. Ghimire (Citation2019) examined the economic implications of religious tourism on small businesses in Shikoku, Japan. A total of 73.3% of participants in the study stated that small businesses had an economic impact on their lives (H. L. Ghimire, Citation2019). Kusi et al. (Citation2015) explored how micro-businesses and small businesses contribute to job creation, income production, and poverty reduction in emerging economies (Kusi et al., Citation2015), and it has been shown that small businesses functioning in historical religious heritage places help to reduce poverty (H. L. Ghimire, Citation2019)as measured by an individual’s education, health, and living standard (D. Ghimire, Citation2014; H. L. Ghimire, Citation2019).

It can be argued that entrepreneurship is essential to uplifting and engaging local communities, particularly in rural areas. Local engagement is important since the success or failure of any rural tourist development is dependent to some extent on the contributions of local communities (Lekaota, Citation2018). Tourism may improve the livelihoods of the poor, but it will require concerted efforts and tactics to establish strong ties with the tourism industry (Banskota & Sharma, Citation1995).

Religious organizations have successfully provided official and informal networking opportunities for would-be entrepreneurs and current small business owners in many countries (Deller et al., Citation2018). Riaz et al. (Citation2016) investigated the direct link between religiosity and entrepreneurial intentions and found that religion is one factor that often determines an individual’s social behavior. Religion also influences an individual’s economic activities, suggesting a direct link between religion and entrepreneurial intentions (Riaz et al., Citation2016). Yasuda (Citation2018) recognized the impact of the religious tourism business in the Islamic community. Mumbai appears to have produced a new sort of “Islamic leisure” culture in Mumbai and India, to which customers willingly offer their money, time, and social networks in the Islamic way (Yasuda, Citation2018).

According to the literature, small enterprises in religious places generate income and economic growth while also providing job opportunities for the local community. Furthermore, small businesses have a significant impact on the lives of low-income households. These businesses encourage the equal allocation and productive use of local resources, which are directly related to local livelihood development. This study’s main purpose is to evaluate the socioeconomic impact of entrepreneurs associated with religious sites and businesses. To do so, the author focus on childhood education, family health, and food expenditures as indicators of livelihood.

3. Research method

3.1. Data collection

The author prepared semi-structured interviews (Anderson, Citation2010; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015) and conducted purposive key informant interviews (KII) using the in-person method. A total of seven KII were conducted from 25 July 2022 to 4 August . A questionnaire survey of local entrepreneurs (Terzidou et al., Citation2008) was also conducted during the same period. The questions focused on the duration of business ownership, economic conditions, household characteristics, and the business owner’s level of satisfaction.

The author distributed the questionnaire in person and asked those receiving the questionnaire to participate in the survey. A total of 323 completed responses were collected. Basic respondent attributes are presented in Table . Using the statistical package Stata 14.2, the author analyzed the collected data and employed a logit regression model to investigate the interrelated variables. The author compiled the information collected from the KII and a stratified sampling approach to process the questionnaires. The sample size was decided by the amount of information required for descriptive and categorical analysis. Before opting to include businesses in the research, the author observed business operations and made sure that the required interviews and surveys with business owners were undertaken. These businesses have a number of employees that help with the day-to-day operations of the business. Such employees of the businesses were not interviewed or surveyed since they lack sufficient knowledge of the business’s operations and economic status. During the survey period, entrepreneurs in the various stratified groups were sampled. Participation was entirely voluntary and the privacy of those who chose to participate was fully protected. Personal information about the respondents such as manager name, firm address, company name, place of residence, etc., was not collected.

Table 1. Survey responses (Frequencies) (N = 323)

3.2. Measurement

The survey questionnaire was separated into business data and owner characteristics. To assess the role of the owner’s business in the economic well-being of the owner’s family, questions were asked in a “Yes/No” format. Respondents were asked about their level of satisfaction with their business, the length of time they had been in business, the size of the business, business management training, the number of employees, business issues, discrimination, business type, and customer origins. The survey also asked about the respondent’s age, education, family size, children’s school type, status of health, household food expenditure, help/training from temple management or from an NGO/INGO or local government, and home ownership in the area. Finally, the author asked the participating entrepreneurs what type of help they would want from the local government or other agencies.

Different types of questions were prepared for the KII. For example, questions for temple management sought information on visitor characteristics by home country, whether local entrepreneurs contribute to the Manakamana trust, and whether temple management has worked to advance local development or to directly aid local entrepreneurs.

Questions for the local senior intellectual/teacher/physician group targeted the contributions of religious tourism to the lives of local residents and business owners, both in the past and in the present, their impact on local livelihoods, job opportunities, and the various benefits received by local residents from their proximity to the temple.

Representatives of the local government and the Nepal Chamber of Commerce (NCC) were asked whether they had studied the Manakamana temple area businesses, whether they supported or were developing plans for local entrepreneurs, and whether local entrepreneurs contributed the Manakamana trust.

Questions for representatives of the cable car company included: Does the business contribute to the livelihood of locals? Does the cable car company provide incentives for local people and entrepreneurs. What is the company’s relationship with local government and other stakeholders?

3.3. Data analysis

Given the nature of the data, descriptive statistics and a binary logistic regression model (Allison et al., Citation2012) were used to analyze the association between entrepreneur characteristics and business scale. The author separated the entrepreneurs into four categories based on business size: (1) operators of very small (street/cart) businesses with no special stalls, (2) small business owners with a one-shutter business stall, (3) owners of medium-sized businesses having a two-shutter business stall, and (4) big business owners, including those having stalls with more than two shutters, hotels, restaurants, cow firms, buffalo firms, and gold shops. The variables were measured as binary (Yes/No), selection group, and selection option. The regression model to test the business scale of the owner’s livelihood is shown below (Kim et al., Citation2021):

Where,

Y = business scale (Yes = 1, No = 0)

x = the explanatory variables, represented as a vector. The explanatory variables include the entrepreneur’s family health (normal) (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), health costs up to 5 thousand Nepalese rupee (Rs.) (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), children’s education (boarding or private) (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), working hours (12–14 hours) (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), business profitability(1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), no help from the local government(1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), not attending any training (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), want business training (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), gender (1 = male; 0 = female), education level (secondary) (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), and age group (41–50) (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise), of business owners.

= intercept parameter

= vector of slope parameters.

4. Results

The demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in Table . Fifty-two percent of the respondents were male. A majority (33.13%) of the business owners were between the ages of 41 and 50. More than 66% of the respondents had less than a secondary education and none had a master’s degree. More than 44% of business owners own small (one shutter) businesses, and more than 54% had owned the business for more than ten years. Most of the business owners and their employees (82%) had received no formal business training.

Cross-tabulation was used to compare pre-existing health issues of business owners and their families with the types of businesses owned. As shown in Figure , a total of 63.48% of the business owners and their families reported normal health conditions; 26.32% reported no health issues, while 10.22% had chronic health problems. These generally favorable health conditions are likely the result of the area’s ready access to medical checkups in large hospitals and health posts, the accessibility of medical services, and the young age of the surveyed population (66.65% of the entrepreneurs were under the age of 50). Even entrepreneurs operating very small businesses reported a normal health situation.

More than 67% of business owners reported that they had their own houses, and business size determined the owners’ livelihood status. Fixed asset ownership is a key indicator of people’s socioeconomic level. Because of the high cost of land and housing, such ownership is gradually more important in defining the social and economic status of families and individuals. Home ownership is thus considered an excellent indicator of socioeconomic position (Coffee et al., Citation2013; D. K. Ghimire et al., Citation2022). Dietz and Haurin (Citation2003) found that property ownership had a positive impact on wealth, investment risk, children’s education, and physical and mental health in both direct and indirect ways (Dietz & Haurin, Citation2003; Haurin et al., Citation2002). Rasmussen et al. (Citation1997) found that homeowners are more likely to have finances available to pay for health care in retirement (Rasmussen et al., Citation1997).

The education of business owners’ children was also considered. As elsewhere, most private schools in Nepal are expensive, and the quality of education tends to be higher than in government schools. On the other hand, most public schools are free (Koirala, Citation2015). In this study, the participating entrepreneurs—even the very small-scale entrepreneurs—indicated their ability to afford their children’s fees and other educational expenses. Table shows that very few children were not attending school. Entrepreneurs with sufficient income tend to send their children to private schools, while those with limited income send their children to public schools.

Table 2. Business type and children’s school

Figure shows that owners of very small (street/cart) businesses in the temple area spend more than 10,000 Rs. per month on food, with none spending less than 10,000 Rs. Overall, less than 6% of entrepreneurs spend less than 10,000 Rs. per month on food. Thus, nearly all are able to maintain a sufficient diet for their family. In addition, more than 70 % of entrepreneurs spend 11,000 to 20,000 per month on food, and more than 23% spend in excess of 21,000 Rs. In Nepal, the minimum wage of workers is less than 15,000 Rs. per month (WageIndicator, Citation2022). The study found that business scale affects food expenses.

Figure shows business scale and years of business operation. As indicated, more than 54% of owners had operated their business for at least 10 years, and more than 22% had operated their business for 6 to 10 years. Only 3.7% had been operating their business for 1 year or less. The majority of businesses that had been operating for more than 10 years were small (one shutter) businesses, representing more than 26 % of the total business. However, even very small (street/cart) businesses had operated their business for over 10 years. Investment size clearly affects business sustainability: big (more than two shutters, hotels, gold shops) tend to operate for over 10 years. At the same time, operating for one year or less is more common in the very small, small, and medium category.

The binary logistic regression model used in the study was designed to evaluate the relationship between Manakamana temple area businesses and owner attributes. The same variables were used for the different scales of business. They included family health, children’s education (where they are studying), working hours, and owner education level.

The results of the regression analysis are shown in Table . Here, the scale of the business serves as the dependent variable (Yes = 1, No = 0) for each business scale. The same independent variables were selected for each business scale and compared to the others. The significant findings include: Very small (street/cart) business and small (one-shutter) business owners in the Manakamana temple area with normal health status (Odds = 11.976, p = 0.000) and (Odds=.171, p = 0.000), respectively. Very small (street/cart) business with health costs up to 5 thousand Rs (Odds=.501, p = 0.053). Children’s’ education, boarding or private, is more likely for small (one-shutter) and medium businesses, with (Odds=.516, p = 0.017) and (Odds = 3.889, p = 0.000), respectively. “Working hours (12–14 hrs.)” is more likely for small, medium, and big businesses, with (Odds=.347, p = 0.000), (Odds = 1.895, p = 0.039) and (Odds = 3.889, p = 0.072) respectively. “Business making profit” is more likely in very small and big businesses, with (Odds=.368, p = 0.005) and (Odds = 8.712, p = 0.013), respectively. Another variable, “no help from the local government,” is likely for big businesses, with (Odds = 1.209, p = 0.041). Next, the variable “not attended any training” is more likely for very small, small, and big businesses, with (Odds=.262, p = 0.003), (Odds = 2.829, p = 0.011) and (Odds=.205, p = 0.028), respectively. Another variable, “want business training,” is likely for very small and small businesses, with (Odds=.345, p = 0.004) and (Odds = 2.233, p = 0.008), respectively. Further, the gender variables for very small, medium, and big businesses are likely, with Odds = .242, p = 0.000), (Odds = 2.15, p = 0.009) and (Odds = 3.856, p = 0.057), respectively. The education level “secondary” of the owners is more likely for very small and medium businesses, with (Odds = 4.471, p = 0.000) and (Odds=.594, p = 0.075), respectively. Finally, “age group” is more likely for small, medium, and big businesses, with (Odds=.344, p = 0.000), (Odds = 2.441, p = 0.002), and (Odds = 3.038, p = 0.055), respectively. This econometrics result shows the influence factor of each business scale in the Manakamana temple area. The owners’ years of business operation, home ownership, number of employees, family members, rent expenses, and food expenses were found not to significantly influence business scale in the Manakamana temple area.

Table 3. Determinant factors of business scale of Manakamana temple area

Religious heritage is seen as a boon by religious heritage managers, tourism officials, tourism organizations, and entrepreneurs. They believe that developing this form of tourism may greatly enhance economic growth (Olsen, Citation2003; UNWTO, Citation2013). In this study, the results indicated that an entrepreneur’s income from religious sites has a positive influence on household wealth, children’s education, overall family health, and nutrition. More than 67% of the entrepreneurs reported owning their own homes. In developing nations, the affordability of housing plays an important role in health and well-being, as well as in the fulfillment of personal preferences (Fairburn & Braubach, Citation2010).

5. Discussion

In general, businesses in the Manakamana temple area had a positive impact on the livelihood of their owners and their families. The owners appear to successfully manage home ownership, education, health, and food expenses. More than 63% of business owners work 12 to 14 hours per day, and more than 24% work 9 to 12 hours. The number of Working hours depends on the nature of the business; e.g., working hours in the hotel and souvenir shops exceed those of other businesses.

Similarly, the health situation of the owners and their families seems normal, with a relatively small percentage facing chronic health issues. Business size does not appear to matter in this regard. Area residents have ready access to medical checkups at a large regional hospital. Health posts and medical services are available in the village for primary checkups. Moreover, the relatively young age of the population (66.65% of entrepreneurs were under age 50) generally means fewer health issues. As a result, even the owners of very small (street/cart) businesses are able to maintain their health and the health of their families.

In Nepal, public school education is free. However, such institutions do not necessarily provide a high-quality education. Private schools offer a relatively high-quality education (Koirala, Citation2015) but are expensive. The author found that a fair number of street/cart entrepreneurs have access to private schools, giving their children the option of a public or private school education.

Regarding expenditures for food, very few entrepreneurs in the study reported spending less than 10,000 Rs. per month while more than 70 % spent between 11,000 and 20,000 Rs. At the same time, the minimum monthly wage in Nepal was only 15,000 Rs. in 2022 (WageIndicator, Citation2022). Even the owners of very small (street/cart) businesses are able to cover basic food expenses.

The study’s econometric results indicate that the scale of the business in the Manakamana temple area have positive and significant impacts on health status, health expenses, children’s school status, working hours, business profit, lack of business training, lack of help from the government, education, and gender. On the other hand, attributes such as home ownership, number of employees, family members, rent expenses, and food expenses, do not appear to influence business operation in the Manakamana temple area.

The author developed seven purposive KII for a series of in-person interviews. First, the temple management were asked about characteristics of the temple’s visitors, whether local entrepreneurs contribute to the Manakamana trust, and whether the temple management directly benefits local development and business entrepreneurs.

Those asked replied that “about 60% of the visitors are Nepalese, 35% are Indian, and 5% are ‘others.’ And temple management neither directly helped local entrepreneurs nor did they receive any financial support from the entrepreneurs.”

The questions posed in the KII with a local senior intellectual, a teacher, and a physician focused on the past and present contributions of religious tourism to the area, its impact on the livelihood of local residents, job opportunities, and the kinds of benefits realized by the local people and their families from this tourist site.

The response from a 79-year-old senior local intellectual was that “in the past period, the locals benefited more than they do now. Because of the cable car, villagers lost job opportunities, such as porters and day laborers. Guesthouse stays were also reduced, and most raw materials were imported from the village or outside the country. Most locals (especially the younger generation) want to get out of the village. Twenty to thirty years ago, most locals ran their own businesses, but now the situation has changed, and locals rent the property and move from the countryside to the city. This situation makes future sustainable tourism very difficult. These situations make the elder really disappointed.” According to the local teacher, who was approximately fifty years of age, “the educational situation in the area is not bad. There are private schools, but there are also government schools as well. Therefore, most students are able to attend school. Most families are also concerned about their kids’ education.” The local physician described the health conditions in the area: “I have been working here for about 20 years. People’s thought has changed to modern medical treatment from traditional. Simple treatment is available locally, but recommendations are made for major illnesses in Kathmandu and Chitwan. In an emergency, people can go to a big hospital in about an hour using a cable car. Approximately 75% of people are conscious about their healthcare, including low incomes households.”

Representatives of the two local governments (wards 2 and 3) were asked whether they had previously studied the Manakamana temple area’s businesses, and about their support/development of future plans for local entrepreneurs.

Both local government representatives answered that “we did not have a special study about local businesses. About 70–80% of the locals are directly involved in the business. The local government is starting to record businesses in ward no 2. And ward no 3 has already registered 157 of these entrepreneurs in ward 3. Waste management is the most serious problem in this area, and business training will be planned in the future. Both wards are focusing on training, especially in food management and hygiene for hotels and restaurants. Support is being provided to farmers to produce flowers locally that are used in these places. Security cameras have been installed for the security of pilgrims and entrepreneurs. Strict rules will be implemented to prevent negotiations and other problems between pilgrims and entrepreneurs. A cooling house is planned nearby to reduce vegetable and fruit imports from outside. It would be more beneficial for entrepreneurs if transportation could be improved.”

NCC and industry representatives were also asked whether they had studied the area’s businesses. They were encouraged to discuss their support/development of plans for local entrepreneurs.

The response from the NCC representatives was as follows: “Our main aim is to create good relationships with entrepreneurs. In addition, NCC always tries to help them in their business. Currently, NCC has installed streetlights in this area for security purposes. For emergencies, NCC runs an ambulance service for residents and pilgrims, including entrepreneurs. They are, furthermore, working with local governments for waste disposal and implementing strict rules for managing food safety and hygiene in hotels and restaurants. Moreover, NCC plans to implement future plans to help entrepreneurs and society by interacting with the local government, and no amount is charged for Manakamana trust by entrepreneurs.”

The questions for representatives of the big business representatives (Manakamana cable car) included: Does the business contribute to the local’s livelihood? Does the cable car company provide incentives for the local people and entrepreneurs? What is the company’s relationship with the local governments and other stakeholders, etc.?

In their answers, the participating cable car administration representatives stated that “we offer a variety of incentives for local residents. For example, the company offers an 80% discount on general ticket prices for local residents. 24-hour emergency service is available in case of accidents and emergencies. Emergency services are available at midnight or outside cable car operating time. The cable car company is located in two municipalities, so the company donates 2% of cable car ticket sales to Sahid Lakhan Rural Municipality (1%) and Ichchhakamana Rural Municipality (1%) as a CSR activity. The company also does other CSR activities for local schools. The company has kept a 24-hour security guard to protect the local forest and actively contribute to tree plantation. Furthermore, the company also offers discounts for local residents on commercial transport too. Although the company did not directly relate to the Manakamana Trust, there are indirect contributions to all those stakeholders. Moreover, the company is involved in various volunteer activities with the local government.”

According to the survey data, 66.3% of the entrepreneurs have less than a secondary education, 31% have a secondary education but less than a bachelor’s degree, and only 2.8% graduated university. One possible implication is that that those with a university degree are not especially interested in entrepreneurship. Many are migrating to the capital city, Kathmandu, and others are moving to cities such as Pokhara and Chitwan. Especially the younger generation is less likely to become involved in a local business. However, this case study provides an illustration of the positive impact on the livelihood of entrepreneurs in religious places.

The study also identified business issues and areas where help is wanted or needed. These include improved road infrastructure, business training, subsidies, security, food safety, hygiene training, cleaning, financial support, health support, etc. Operators of hotels/lodges, gift shops, and agriculture-related entrepreneurs are in need greatest need of business training, food safety instruction, and hygiene guidance. Improvements in road infrastructure are needed since there is no other option in the rainy season except the cable car, which is a costly means of transport for both the entrepreneurs and visitors to the temple.

One final note: As argued by Brewer (Citation1994), qualitative-based inquiry does not have to be quantifiable and rigid to be precise, as anecdotal, avid, and unique research can also be principled, disciplined, and significant (Brewer, Citation1994). Regarding the nature of the data, the author followed Hillman and Radel (Citation2022), Kunwar et al. (Citation2022) and presents the KII raw answers in the same way (Hillman & Radel, Citation2022; Kunwar et al., Citation2022).

6. Conclusions

This study sought to identify the impact of religious tourism on the livelihoods of local entrepreneurs in the Manakamana temple area. This region is well-known in Nepal as a prominent pilgrimage site that serves as a vital source of income for many people (D. K. Ghimire et al., Citation2022), including extremely small business entrepreneurs and their families, who must maintain their lives through businesses requiring only a small initial investment.

Descriptive and econometric approaches were used to analyze the primary data collected during a field survey conducted by the author. As per the study’s descriptive analysis, local businesses contribute positively to the health of the owners and their families, to their children’s education, and to food purchases. A binary logistic regression model was also used to examine the impact of business activity on family health and education, as well as the business owners’ working hours, education level, gender, and age group in order to determine whether there were differences related to business scale. Furthermore, the econometrics result shows the influence factor of each business scale in the Manakamana temple area.

The study also explored some of the issues of concern to local entrepreneurs, including improved road infrastructure, business training, subsidies, security, training in food safety and hygiene, cleaning, financial support, and health support.

For local residents, the areas around religious sites such as Manakamana Temple are a good starting point for creating small businesses. Such businesses increase access to food, education, and healthcare for the owners and their families. Shinde (Citation2010) argues that religious tourism is a natural outgrowth of the ritualized pilgrimage economy, influenced by the changing social economy, religious, and cultural activities associated with modern pilgrimage practices. Entrepreneurship arises from incorporating this economy, especially in religious and cultural contexts (Adhikari, Citation2020; Shinde, Citation2010). This study shows that the businesses operating in the vicinity of the Manakamana Temple have a positive impact on the livelihood of the entrepreneurs operating these businesses and their families.

Sustainable tourism planning necessitates balancing the need to protect cultural and historical assets with the need to offer a positive visitor experience and the need to preserve and promote the well-being of the local community (Levi & Kocher, Citation2013). Tourism is undoubtedly a driver of cultural and natural heritage preservation and conservation and a vehicle for sustainable development (UNWTO, Citation2013). Commercializing these heritage places has a favorable economic impact, including job creation and expansion (Gould & Burtenshaw, Citation2019). Retail sales of publications, souvenirs, refreshments, entry fees, and site maintenance and operation are examples of commercialized activity at cultural, historical, and religious heritage sites (Gould & Burtenshaw, Citation2019). According to the findings of this study, religious places play a vital role in the local economy through entrepreneurship. The contributions of small businesses to the upkeep and functioning of these religious places will be one of the targets of future research.

Even though the small businesses operating in religious areas are independent, their operations are strongly influenced by other activities within the Manakamana region. Their performance and continuity are closely interrelated with the various festivals and ceremonies in the area and the activities of nearby businesses and communities. The income generated by enterprises at such religious places is influenced by the lodging, cafes, and festivals that surround them. A diverse business conglomerate creates profitable opportunities for all businesses. Left to future research is the interconnection of very small, small, medium, and large businesses, and their roles in revenue generation. Future research will also consider the effect of seasonal festivals on revenue generation in religious places.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines and approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research of Soka University (Date of IRB approval: 20 May 2022; Approval No.2022009).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Prakash Gautam

Dr. Prakash Gautam is an assistant professor of business administration at Soka University, Hachioji, Tokyo. He actively researches and writes materials about India and Nepal's medical and religious tourism. His research interests include revenue management, tourism industry issues, and corporate social responsibility in the Indian context. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Soka University. His dissertation is written in Japanese; his research papers are also in English.

References

- Abad Galzacorta, M., de Deusto, U., & Deustoes, A. M. (2016). Pilgrimage as tourism experience: The case of the Ignatian way. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 4(4), 48–18. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7KT5N

- Abereijo, I. O., & Afolabi, J. F. (2017). Religiosity and entrepreneurship intentions among Pentecostal christians. Diasporas and Transnational Entrepreneurship in Global Contexts, 236–251. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1991-1.ch014

- Adhikari, S. (2020). Manakamana temple tourism. Research Nepal Journal of Development Studies, 3(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.3126/rnjds.v3i1.29648

- Akinwale, O., & Ogundiran, O. (2014). The impacts of small business on poverty reduction in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(15), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n15p156

- Allison, P. D., Allison, P. D., & SAS Institute. (2012). Logistic regression using SAS : Theory and application.

- Anderson, C. (2010). Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(8), 141. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7408141

- Ateljevic, I., & Doorne, S. (2000). ‘Staying within the fence’: Lifestyle entrepreneurship in tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(5), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580008667374

- Banskota, K., & Sharma, B. (1995). Tourism for mountain community development: Case study report on the Annapurna and Gorkha regions of Nepal. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development.

- Behsudi, A. (2020, December). Tourism-dependent economies are among those harmed the most by the pandemic. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2020/12/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi#

- Bleie, T., & Bhattarai, L. (2002). Sovereignty and honours as a redistributive process: An ethnohistory of the temple trust of Manakamana in Nepal. The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, 23, 26–55. https://www.cmi.no/publications/1687-sovereignty-and-honours-as-a-redistributive

- Borges, M. A., Carbone, G., Bushell, R., & Jaeger, T. (2011). Sustainable tourism and natural World Heritage. In Priorities for action. IUCN, Gland. Issue January. http://www.iucn.org/knowledge/publications_doc/publications/

- Brewer, J. D. (1994). The ethnographic critique of ethnography: Sectarianism in the ruc. Sociology, 28(1), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038594028001014

- Coffee, N. T., Lockwood, T., Hugo, G., Paquet, C., Howard, N. J., & Daniel, M. (2013). Relative residential property value as a socio-economic status indicator for health research. International Journal of Health Geographics, 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-12-22

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

- Deller, S. C., Conroy, T., & Markeson, B. (2018). Social capital, religion and small business activity. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 155, 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.09.006

- Dietz, R. D., & Haurin, D. R. (2003). The social and private micro-level consequences of homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics, 54(3), 401–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-11900300080-9

- Digance, J. (2003). Pilgrimage at contested sites. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-73830200028-2

- Fairburn, J., & Braubach, M. (2010). Social inequalities in environmental risks associated with housing and residential location. In W. (Ed.), Environment and health risks: a review of the influence and effects of social inequalities (pp. 33–75). WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Fleischer, A. (2000). The tourist behind the pilgrim in the Holy Land. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(3), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-43190000026-8

- Gautam, P. (2020). A study of revenue management of Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam: Management control of religious trust in India. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 11(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.3126/gaze.v11i1.26634

- Gautam, P. (2021). The effects and challenges of COVID-19 in the hospitality and tourism sector in India. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Education, 11, 43–63. https://doi.org/10.3126/jthe.v11i0.38242

- Getz, D., & Carlsen, J. (2000). Characteristics and goals of family and owner-operated businesses in the rural tourism and hospitality sectors. Tourism Management, 21(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-51770000004-2

- Getz, D., & Peterson, T. (2005). Growth and profit-oriented entrepreneurship among family business owners in the tourism and hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 24(2), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.06.007

- Ghimire, D. (2014). Poverty identity card distribution: A theoretical analysis. A Journal of Development, 35(1), 65–74. https://npc.gov.np/images/category/VIKAS_Vol_351.pdf

- Ghimire, H. L. (2019). Heritage tourism in Japan and Nepal: A study of Shikoku and Lumbini. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 10(1), 8–36. https://doi.org/10.3126/gaze.v10i1.22775

- Ghimire, D. K., Gautam, P., Karki, S. K., Ghimire, J., & Takagi, I. (2022). Small business and livelihood: A study of Pashupatinath UNESCO heritage site of Nepal. Sustainability, 15(1), 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010612

- Gilchrist, R. (2020). Sacred heritage. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108678087

- Goodwin, H. (2011). Tourism and poverty reduction: Pathways to prosperity. Tourism Management, 32(5), 1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.018

- Gould, P. G., & Burtenshaw, P. (2019). Heritage sites: Economic incentives, impacts, and commercialization. In Encyclopedia of global archaeology (pp. 1–7). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_508-2

- Hassan, T., Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, W., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2022). Segmentation of religious tourism by motivations: A study of the pilgrimage to the city of Mecca. Sustainability, 14(13), 7861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137861

- Haurin, D. R., Parcel, T. L., & Haurin, R. J. (2002). Does homeownership affect child outcomes? Real Estate Economics, 30(4), 635–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.t01-2-00053

- Hillman, W., & Radel, K. (2022). Transformations of women in tourism work: A case study of Emancipation in Rural Nepal. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 13(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.3126/gaze.v13i1.42040

- Kaelber, L. (2006). Paradigms of travel from medieval pilgrimage to the postmodern virtual tour. In D. J. Timothy & D. H. Olsen (Eds.), Tourism, religion and spiritual journeys (pp. 49–63). Routledge.

- Kim, K., Yamashita, E., & Ghimire, J. (2021). Pausing the pandemic: Understanding and managing traveler and community spread of COVID-19 in Hawaii. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2677(4), 324–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981211058428

- Koh, K. Y., & Hatten, T. S. (2002). The tourism entrepreneur. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 3(1), 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1300/J149v03n01_02

- Koirala, A. (2015). Debate on public and private schools in Nepal. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management, 2(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijssm.v2i1.11882

- Kunwar, R. R., Adhikari, K. R., & Kunwar, B. B. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism in Sauraha, Chitwan, Nepal. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 13(1), 111–141. https://doi.org/10.3126/gaze.v13i1.42083

- Kusi, A., Narh Opata, C., & John Narh, T.-W. (2015). Exploring the factors that hinder the growth and survival of small businesses in Ghana (A case study of small businesses within Kumasi Metropolitan area). American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 05(11), 705–723. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2015.511070

- Lekaota, L. (2018). Impacts of World heritage sites on local communities in the Indian Ocean Region. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism & Leisure, 7(3), 1–10. https://www.ajhtl.com/2018.html

- Levi, D., & Kocher, S. (2009). Understanding tourism at heritage religious sites. Focus, 6(1), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.15368/focus.2009v6n1.2

- Levi, D., & Kocher, S. (2013). Perception of sacredness at heritage religious sites. Environment and Behavior, 45(7), 912–930. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512445803

- McGehee, N. G., & Kim, K. (2004). Motivation for agri-tourism entrepreneurship. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268245

- MoCTCA. (2020). Ministry of culture, Tourism & Civil Aviation. https://www.tourismdepartment.gov.np/files/publication_files/394.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3EQbuAcJDxsTKK4ekyzPbNCiSgE2WxpmwWBvYWrsO-tJBvswMN4_vdWqE

- Nolan, M. L., & Nolan, S. (1992). Religious sites as tourism attractions in Europe. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-73839290107-Z

- OECD. (2008). The impact of culture on tourism. In The Impact of Culture on Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264040731-en

- OECD. (2022). OECD tourism trends and policies 2022. https://doi.org/10.1787/a8dd3019-en

- Olsen, D. H. (2003). Heritage, tourism, and the commodification of religion. Tourism Recreation Research, 28(3), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2003.11081422

- Rasmussen, D. W., Megbolugbe, I. F., & Morgan, B. A. (1997). The reverse mortgage as an asset management tool. Housing Policy Debate, 8(1), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1997.9521251

- Rasool, H., Maqbool, S., & Tarique, M. (2021). The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Business Journal, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

- Riaz, Q., Farrukh, M., Rehman, S., & Ishaque, A. (2016). Religion and entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 3(9), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2016.09.006

- Rinschede, G. (1992). Forms of religious tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-73839290106-Y

- Shackley, M. (2002). Space, sanctity and service; the English Cathedral as heterotopia. International Journal of Tourism Research, 4(5), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.388

- Sharpley, R., & Sundaram, P. (2005). Tourism: A sacred journey? The case of ashram tourism, India. International Journal of Tourism Research, 7(3), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.522

- Shinde, K. A. (2010). Entrepreneurship and indigenous enterpreneurs in religious tourism in India. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(5), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.771

- Simone-Charteris, M. T., & Boyd, S. W. (2010). The development of religious heritage tourism in Northern Ireland: Opportunities, benefits and obstacles. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 58(3), 229–257. https://hrcak.srce.hr/62778

- Singh, R. P. B., & Rana, P. S. (2016). Indian sacred natural sites: Ancient traditions of reverence and conservation explained from a Hindu perspective. In B. Verschuuren & N. Furuta (Eds.), Asian sacred natural sites: Philosophy and practice in protected areas and conservation (1st ed., pp. 81–92). Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Smidt, C. (2003). Introduction. In S. Corwin (Ed.), Religion as Social Capital: Producing the Common Good (pp. 1–18). Baylor University Press.

- Smith, V. L. (1992). Introduction the quest in guest. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-73839290103-V

- Terzidou, M., Stylidis, D., & Szivas, E. M. (2008). Residents’ perceptions of religious tourism and its socio-economic impacts on the Island of Tinos. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 5(2), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530802252784

- Thouki, A. (2019). The role of ontology in religious tourism education—exploring the application of the postmodern cultural paradigm in European religious sites. Religions, 10(12), 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10120649

- Tomalin, E., Haustein, J., & Kidy, S. (2019). Religion and the sustainable development goals. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 17(2), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2019.1608664

- Tsironis, C. N. (2022). Pilgrimage and religious tourism in society, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: A paradigmatic focus on ‘St. Paul’s Route’ in the Central Macedonia Region, Greece. Religions, 13(10), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100887

- UNWTO. (2013). Tourism at world heritage sites challenges and opportunities tourism at world heritage sites challenges and opportunities international tourism seminar. UNWTO.

- UNWTO. (2015). UNWTO annual report 2014. In UNWTO Annual Report 2014. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284416905

- UNWTO. (2016). UNWTO tourism highlights, 2016 Edition. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284418145

- UNWTO. (2021). International tourism highlights, 2020 Edition. In International Tourism Highlights, 2020 Edition. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284422456

- Verschuuren, B. (2007). An overview of cultural and spiritual values in ecosystem management and conservation strategies. In B. Haverkort & S. Rist (Eds.), Endogenous Development and Biocultural diversity: The interplay of worldviews, globalisation and locality (Series on Worldviews and Sciences; No. 6) (pp. 299–325). COMPAS. http://www.bioculturaldiversity.net/downloads/papersparticipants/verschuuren.pdf

- WageIndicator. (2022). Minimum Wage - Nepal. https://wageindicator.org/salary/minimum-wage/nepal

- Wennekers, S., & Thurik, R. (1999). Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Business Economics, 13(1), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008063200484

- Yasuda, S. (2018). Entrepreneurship for religious tourism in Mumbai, India. In S. Yasuda, R. Raj, & K. Griffin (Eds.), Religious tourism in Asia tradition and change through case studies and Narratives (pp. 21–29). CAB International. https://lccn.loc.gov/2018034784

- Zhou, L., & Chan, E. S. W. (2019). Motivations of tourism‐induced mobility: Tourism development and the pursuit of the Chinese dream. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 824–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2308