Abstract

Indoor environment quality is considered a vital factor in the success of occupants and in achieving high productivity. In this context, there has been a substantial growth over the past two decades in the studies conducted worldwide examining the relationship between Indoor Environment Quality (IEQ) and occupant’s productivity. This study focuses on the impact of IEQ on Occupant Productivity (OP), as well as its role in facing and overcoming the threats posed by COVID−19. Furthermore, the study paves the way for research on IEQ and OP after returning to work during COVID−19. The researcher conducted a closed-ended questionnaire with telecommunication companies in the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) from May to December 2019. The total number of completed and collected questionnaires was 385. The data collected were analysed using structural equation modelling technique with the AMOS 23 V software. The findings demonstrate that IEQ has a positive and significant influence on OP. Specifically, the office layout, location and amenities, indoor air quality and ventilation, noise and acoustics, and lighting and day lighting were found to have positive and significant effects on OP. However, biophilia and views were found to have no significant effect on OP. These findings could be used by designers, architectures, facilities managers, and office occupiers to formulate their IEQ strategy to overcome COVID−19 and to increase productivity. The strength of this paper lies in its focus on analyzing and developing a comprehensive and integrated perspective of IEQ elements that contribute to increasing occupants’ productivity upon their return to work during COVID−19. This is accomplished by providing knowledge and training for occupants, in addition to implementing precautionary measures related to the IEQ elements that influence productivity.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID−19) raises many issues within organizations, but the issue of productivity remains the most important issue and it influences the output of occupants, work teams, and the whole organization (World Health Organization, Citation2020a; Zhang & Rehman Khan, Citation2022). Hence, achieving high productivity presents a challenge for organizations’ abilities in facing the pandemic of COVID−19. Indoor Environment Quality (IEQ) plays a vital role in increasing the occupant’s productivity (B. P. Haynes, Citation2008a).

As a result of the spread of the COVID−19 pandemic, the occupants’ productivity is facing many challenges. Occupants happened to experience psychological symptoms such as depression, stress, worries, and anxiety due to the outbreak of COVID−19 (Golberstein et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, such psychological symptoms affect their daily behavior (Torales et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the measures of quarantine and social distance led to the increase in mood lability, and the decrease in social and physical communication (Brooks et al., Citation2020), and even suicidal ideation (Gunnell et al., Citation2020) for extended periods. Furthermore, in the era of COVID−19 pandemic, it is necessary to have productive resources and adapt the production process to such scenarios and be prepared to implement flexible plans (Khan, Ponce, Thomas, et al., Citation2021; Zhang & Rehman Khan, Citation2022).

Hence, the study and development of IEQ will represent a substantial barrier in overcoming COVID−19 symptoms, especially the psychological issues in the workplace. IEQ is highly associated with improving and enhancing occupant’s productivity (B. P. Haynes, Citation2008b). This study addresses the challenging issue of Occupant Productivity (OP) in the workplace considering the precautionary measures during the spread of Coronavirus (COVID−19). This study aims to provide an answer to the following question:

What are the components of Indoor Environment Quality (IEQ), under the control of managers and designers, have a significant influence on occupants’ productivity when considering the challenges of facing the COVID−19 pandemic?

This is because occupants are the most valuable resource for any progression of an organization’s prosperity since each organization invests a lot of money to create and maintain the work environment (Khan et al., Citation2022; Rasheed & Byrd, Citation2017). Moreover, IEQ plays a crucial role in providing companies with a competitive advantage. It influences productivity (Cabrera, Citation2018) and occupants’ creativity (Alayis et al., Citation2020). In recent years, there has been a growing interest in IEQ’s impact on occupant’s productivity (Al Horr et al., Citation2016; Candido et al., Citation2019; Kaushik et al., Citation2020; Khoshbakht et al., Citation2020). Occupant’s productivity is one of the top priorities for any organization’s management (Wiik, Citation2011). The findings of Gensler’s (Citation2005) study demonstrate that IEQ improves occupants’ productivity by nearly 20%. In 2019, Scandura, et al. added to their findings the results of the 2012 Gallup Survey of 1.4 million employees, which indicates that a healthy work environment is reflected in high occupant productivity.

KSA companies should balance the possible positive benefits and negative consequences of the COVID−19 pandemic. One of the significant negative consequences of COVID−19 is the widespread lay off and substantial reduction of economic activities. Consequently, there is a need to increase the workload to achieve higher productivity. Moreover, organizations should enhance their internal work environment through the implementation of information technology practices to mitigate the side effect of COVID−19 (Khan, Ponce, Tanveer, et al., Citation2021). Overcoming the negative consequences of COVID−19 imposes a major challenge in the workplace. Therefore, IEQ needs to get aligned with the new measures declared by the World Health Organization (WHO). One of the great challenges organizations face is the green practices and sustainability (Khan et al., Citation2022). Hence, this study’s findings will contribute to creating IEQ to support green practices and sustainability. The main theme and contribution of this study is to fill two gaps, the first one is theoretical gaps between studies that have focused on the impact of only one component of IEQ and occupant’s productivity as (B. P. Haynes, Citation2008b; Seddigh et al., Citation2014; Wargocki et al., Citation2000; Wheeler & Almeida, Citation2006), in addition to the gap of the studies investigating the role of IEQ in overcoming COVID−19 challenges in the workplace (Afful et al., Citation2022; Amerio et al., Citation2020; Golberstein et al., Citation2020; Hoisington et al., Citation2019; Serafini et al., Citation2020). This research aims to establish IEQ through full framework that effectively supports the occupants’ productivity in a changing environment with an integrated and comprehensive view of developing IEQ and support occupant’s productivity. The second is contextual gaps because this study is one of the first studies that focused on formulating IEQ of telecommunications industry in KSA and the occupant’s productivity. To investigate the impacts of the components of IEQ on the occupants’ productivity and to formulate the framework of the ideal work environment that could overcome the negative consequences of COVID−19 pandemic, this research was as follows: The second section provides a literature review, the third section covers the methodology, analysis parts, while the results discussion was addressed in the fourth section. The last section provides the conclusion and recommendations that could be employed by decision-makers, designers, and architects.

2. Literature reviews and hypotheses development

The main backbone of the literature reviews attempts to show and build the linkage between IEQ and occupants’ productivity in facing the challenges arising from COVID−19.

2.1. Definition of Occupant Productivity (OP)

The term, Occupant Productivity (OP), is one of the priorities of every company’s management across different eras. Every company aims to achieve the maximum productivity with the highest degree of efficiency and effectiveness. From Marx 1818, through Taylor 1917 until now, researchers have paid great attention to OP. The definition of occupant productivity varies depending on the context and content of the input and output (Al Horr et al., Citation2016). Occupants’ productivity is the relationship or the ratio of output to input (Tangen, Citation2002). Occupants’ productivity is the main goal for each company’s management in any era. Many kinds of research are conducted yearly to study how to increase and improve the occupants’ productivity (Guo et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2022; Mehmood et al., Citation2022). Small increases in productivity, are enough to justify additional capital expenditure to improve the quality of the building’s services (Clements-Croome, Citation2018). The studies of B. P. Haynes (Citation2008a, Citation2008b) mentioned that a self-assessed measure of productivity is considered an acceptable approach. Ultimately, this results in establishing and supporting IEQ, which leads to reductions in energy consumption and maintenance costs. So, OP is considered acceptable and valuable to measure the occupant’s productivity from their perceptual. In response to these pressures, the companies aim to boost OP (Kotler & Armstrong, Citation2017). Wiik (Citation2011) defined indoor productivity as “The individual’s holistic response to the indoor environment as part of the systematic response patterns of other employees and relative to the ideal employee”.

2.2. Improving the work environment and the Occupant Productivity (OP) and COVID−19

The World Health Organization in Citation2020b defined coronavirus disease (COVID−19)” is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus”. As the WHO reported about the COVID−19 pandemic in June 2020, the number of confirmed cases is more than 8.998 million, and there have been 469,000 confirmed deaths COVID−19 has infected 216 countries worldwide. The WHO has issued worldwide alerts to protect public health and has confirmed the social measures that should apply to individuals, institutions, communities, local and national governments, and international bodies to limit or stop the penetration of COVID−19 in societies (World Health Organization, Citation2020a). The WHO’s declared group of measures consist of individual and environmental measures; discovering and isolating cases; contact-tracing and quarantine; social and physical distancing for mass gatherings; and international travel measures. All the measures urged countries to close all or some aspects of life in the earlier period and every country has developed a bundle of adaptive strategies that aim to protect the wheel of its economy. There is no doubt that there is an influence of environmental factors (such as temperature and humidity) on airborne viruses, but it is still not clear due to the complexities involved (Kakoulli et al., Citation2022).

The creation and provision of IEQ plays a vital role in aiding the occupants to perform and achieve higher productivity. IEQ has a great effect on OP and deserves to be studied in depth. Consequently, creating IEQ helps to attention recovery, psychological resilience, decrease psychological disorder particularly stress on occupants in facing COVID−19 negative effects. The study of (White et al., Citation2019) and (Núñez-González et al., Citation2020) highlighted the role of the benefits of reactiveness time with natural environments and improving mental health.

The mental health is not merely the absence of mental disorders, but rather a state of wellness in which everyone can realize their own potential, adapt to normal stress situations, work productively and meaningfully, and contribute to their local community (The World Health Organization). In addition, studies of (Gatchel et al., Citation1989; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., Citation1987, Citation1995) have confirmed that stress may have negative effects on the physiological, psychological, cognitive, behavioral, and social aspects of humans. (WHO) has referred to several conclusions related to mental health in the work environment. Work is beneficial to mental health, and a negative work environment can lead to physical and mental health problems. Depression and anxiety have economic implications, as their cost in terms of lost productivity to the global economy is estimated at the US $ 1 trillion annually. There are many effective and influential measures that organizations can take to promote mental health in the workplace. Likewise, measures such as these can be beneficial to productivity. For every US $ 1 invested in providing expanded treatment for common mental disorders, a return of US $ 4 is generated in terms of improved health and productivity. The organization has indicated that workplaces that promote mental health and support people with mental disorders reduce absenteeism, increase productivity, and benefit from the associated economic gains.

Regarding, COVID−19 specifically, studies of ((Al Mamun et al., Citation2021; Clemente-Suárez et al., Citation2021; Favreau et al., Citation2021; Markiewicz-Gospodarek et al., Citation2022) indicate the relationship between COVID−19 and mental disorders, and among these disorders is psychological anxiety, anxiety is the feeling of tension about things that happen around us or are about to happen. People become anxious about being diagnosed with the virus, along with anxiety that close people will become infected, and anxiety that self or close people will be subjected to social isolation or quarantine. This state of anxiety is expected to affect employee performance and productivity. IEQ may leading to stress by impact on occupants’ needs in the workplace (Rashid & Zimring, Citation2008). Consequently, managers should recognize IEQ roles are increasing to aid occupants psychologically after return to workplace.

The leader in workplace is a part of success of any organization (Yukl, Citation1989). Moreover, he effects on increasing the productivity and improving the occupant performance and effect on individual behaviors (Nicolaou-Smokoviti, Citation2004). The organizational development copes with the development of leadership theories. From great-man theory to servant, transformational and ethical leadership theory, the role of leader is increasing to create and maintain the work environment to achieve high productivity (Greenleaf et al., Citation1996). mentioned the importance of servant leader to support the followers to overcome anxieties and help them to be more autonomous and knowledgeable. Additionally, transformational theory focused on the motivation and morality of leaders and followers (House & Shamir, Citation1993).

In coronavirus (COVID−19) pandemic, the role of e-leadership increases to overcoming psychological disorder and raise the moral of occupants. The role of leader represents to facilitate and servant occupants. Lynn Shollen and Cryss Brunner (Citation2016) confirmed on role of leader in creating a positive interactive work environment. The result of (Kayworth & Leidner, Citation2002) indicated that leader in virtual work environment has a great impact giving feedback, supporting occupants to achieve their targets. The deeds and behaviors of leader in traditional or virtual work environment support indoor environment quality. In a Corona Virus pandemic, the role of leaders or e-leaders will help to decrease the worries and pressures and psychological issues of occupants. To achieve an integration work environment, the companies should merge between IEQ and role of leadership.

2.3. Indoor Environment Quality (IEQ) and Occupant Productivity (OP)

All companies are competing to improve their productivity. They can achieve it in several ways. Companies can train current employees better or hire new ones who will work harder or more skillfully (Kotler & Armstrong, Citation2017) or they can build and improve IEQ (Huang et al., Citation2012; Mujan et al., Citation2019). Where the quality of the indoor environment plays a fundamental role in well-being, health and productivity because occupants spend about 90% of their time indoors (Kakoulli et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2022; Qabbal et al., Citation2022). Wheeler and Almeida’s (Citation2006) and P. J. Paevere’s (Citation2008) findings show that a better working environment may increase OP by 19%. P. Paevere and Brown’s (Citation2009) findings indicate that, due to an improvement in the work environment, the OP increased by 4.9%. Mujan et al. (Citation2019) findings indicate that over the past 20 years more attention has been paid to IEQ and OP and the peak of interest was in 2018. Khoshbakht et al. (Citation2020) findings show that the components of OP and IEQ should be considered. Kakoulli et al. (Citation2022) proven that IEQ has influence on the occupants’ health, comfort, productivity, and general well-being.

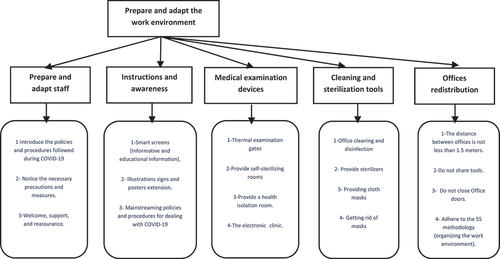

In KSA’s vision 2030, one of the highest priorities is the country’s citizens, and a great deal of attention has been paid to them whether through improving their health both at home and in the work environment. Therefore, KSA industries must have a moral responsibility to provide health facilities in which the occupants feel satisfied and comfortable and that these conditions lead to prosperity (Mujan et al., Citation2019). KSA companies contribute to achieving the country’s 2030 vision through creating and supporting the quality working environment. In turn, this will lead the occupants to produce more. As shown in Figure , the KSA’s Ministry of Commerce has developed a guide that contains all precautionary and preventive measures to back the workplace overcoming the threats posed by COVID−19. This guide is based on five points: namely, job analysis; development and creation of new policies; enabling electronic transformation; adapting the work environment; and communicating with occupants. Dong and Bouey’s (Citation2020) findings discuss psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, which will affect occupants as a consequence of the COVID−19 pandemic. The Ministry of Commerce has formulated, also, six pre-return procedures for workplaces to create a work environment to deal with and overcome the threats posed by COVID−19). These procedures are:

Figure 1. Prepare and adapt the work environment.

Office’s redistribution.

Provision of cleaning and sterilization tools.

Provision of medical examination devices.

Provision of informative and educational posters.

Designing guidelines.

Designing a program to prepare occupants on returning to the workplace.

(IEQ) is one of the main standards in the Green Building Rating System (GBRS) such as HQE, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method Gulf (BREEAM-G), Comprehensive Assessment System for Building Environmental Efficiency (CASBEE), Pearl Building Rating System (PBRS), the Jordan Green Building Guide (JGBG), German Sustainable Building Council (DGNB), the Green Building Assessment System of Taiwan (EEWH), Thai’s Rating Energy and Environmental Sustainability (TREES) and the Green Building Initiative (GBI). IEQ consists of several components. The GBRS came about after Al Horr et al. (Citation2016) reviewed over 300 papers from 67 journals, conference articles and books. They outlined that IEQ consists of seven components: namely, indoor air quality and ventilation; thermal comfort; lighting and daylighting; noise and acoustics; office layout; biophilia and views; look and feel; and location and amenities. In their studies, Kim et al. (Citation2022); Kakoulli et al. (Citation2022) Dykes and Baird (Citation2013); Kang et al. (Citation2017); Mujan et al. (Citation2019) and De Simone and Fajilla (Citation2019) have focused on the five components of IEQ. These include the following: acoustic environment; layout; air quality; thermal comfort; and lighting with occupant productivity. According to what was mentioned in previous studies, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1

IEQ has a positive and significant impact on OP.

2.3.1. Indoor Air Quality And Ventilation and COVID−19

There is vital concern about Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) and ventilation and, more particularly, its effect on occupant productivity in office environments. IAQ is characterized mainly by four environment categories, such as thermal comfort, indoor air quality, lighting, and acoustics (Kakoulli et al., Citation2022; Khovalyg et al., Citation2020). Although there are specific guidelines, directives and standards related to outdoor air quality in various countries, the legislative context is still missing indoors (Kakoulli et al., Citation2022). Moreover, with the increased state of panic from the spread of COVID−19 in the workplace, there is a need for increased attention to IAQ in the workplace to maintain the safety of both occupants and their clients (Kakoulli et al., Citation2022). In discussing problems of indoor air quality in office environments, Carrer and Wolkoff (Citation2018) emphasized the importance of developing programs for the cessation of smoking and stress and IAQ management to improve workplace health. Wyon (Citation2004) findings prove that poor indoor air quality and ventilation in an office environment can reduce OP and it allows customers to express their dissatisfaction. Gupta et al., (Citation2020) results show that the occupants’ productivity decreased when they were dissatisfied about air quality. The results show, also, that the OP decreased with low ventilation (Aguilar-Gomez et al., Citation2022; Ben David et al., Citation2019). Kang et al. (Citation2017) and Mujan et al. (Citation2019) findings show that indoor air quality and ventilation have positive impacts on OP. Moreover, a study Umishio et al. (Citation2022) found that the rate of satisfaction is higher about air quality in the home compared to offices during the period of obligating workers to work remotely during the COVID−19 pandemic. Moreover (Azuma et al., Citation2020), ensured the need of study the effect and role of indoor environmental quality control, particularly ventilation.

(Agarwal et al., Citation2021) found that poor air quality increased the COVID−19 infection in indoor spaces. Each company formulates and declares IEQ measures that aim either to reduce new infections or the spread of COVID−19 in the workplace by renewing and increasing the air quality. The Indian Society for Heating Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers (ISHRAE) recommends that 40 to 70% of relative humidity may cause COVID−19 infection. Therefore, companies’ managers need to confirm that the offices’ ventilation systems work properly (Centers for Disease Control and Preventions). in building Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems, it is essential that these protect the occupants from COVID −19. In 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Preventions recommend that the following steps should be applied in the workplace:

Increase air filtration external points to as high a level as possible without significantly decreasing design airflow.

Run the building ventilation system even during unoccupied times to increase dilution ventilation.

Generate clean-to-less-clean air movement.

Recommend to occupants to work in areas served by “clean” ventilation zones that do not include higher-risk areas such as customer reception or exercise facilities (if open).

Based on the literature review we posit the following hypothesis:

H2

Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation has a positive and significant impact on OP.

2.3.2. Thermal comfort and COVID−19

Thermal comfort is a major standard in IEQ. In the last few years, there has been a growing interest in studying the linking between thermal comfort and OP. Recently, Kaushik et al. (Citation2020) findings have confirmed dependencies of occupant thermal comfort and productivity in various indoor environment factors. Tabadkani et al. (Citation2020) findings show that there is a vital variation in thermal comfort among occupants because of the diversification of socio-cultural bases and adaptive behaviors. They have examined the effect of temperature on thermal comfort and self-reported productivity, Lipczynska et al. (Citation2018) findings show that the occupants’ productivity increased with high thermal comfort. Kang et al. (Citation2017) and Mujan et al. (Citation2019) findings show that thermal comfort has a positive impact on OP. In addition, the study (Umishio et al., Citation2022) found that the satisfaction rate is higher regarding the quality of the thermal environment at home compared to offices during the period of obligating workers to work remotely during the pandemic. Tabadkani et al. (Citation2020) results show that control strategies, which are responsible for increasing OP and limiting the risks of their discomfort, achieve, also, controllable energy.

From their findings, Khattabi et al. (Citation2020) consider that thermal comfort is one of the factors that is mainly responsible for the spread of COVID−19. In addition, Ashrae guidline (Citation2020) confirms that heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems in healthcare facilities affect the transmission of disease. Consequently, they have an essential role in dealing with the threats posed by COVID−19. Also, in April 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 2020 that the high temperatures reduce the effectiveness of dealing with COVID−19. While not making a definitive recommendation on the setpoint of indoor temperature. Ashrae guidline (Citation2020) recommend that this be studied on a case-by-case basis. On the contrary, Prata et al. (Citation2020) findings indicate that temperature has had a negative linear relationship with the number of confirmed cases. Usually, the workplace temperature is between 24° and 26° C and is controlled by the Air Conditioner (AC) system. However, as the COVID−19 results show temperatures must not go beyond 32°C to protect the occupants. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3

Thermal comfort has a positive and significant impact on OP.

2.3.3. Day lighting and lighting and COVID−19

Day Lighting and Lighting is an essential part of the occupants’ lives since it has a huge impact on their productivity (Boyce et al., Citation2003; Figueiro et al., Citation2002; Umishio et al., Citation2022). Using real-time simulation Jones and Reinhart (Citation2019) experimentally measured the effects of visual comfort on OP. Their results show that OP and satisfaction increased with respect to spatial daylight autonomy and the enhanced probability of simplified daylight glare. For several years, much effort has been devoted to the study of the effects of daylighting on human beings because its impact reduces the visual discomfort by improving human beings physically psychologically, physiologically, their moods and the performance of tasks (Boyce et al., Citation2003; Figueiro et al., Citation2002; Jones & Reinhart, Citation2019). From their review of experimental studies about integrated lighting control strategies, Jain and Garg’s (Citation2018) findings show the importance of studying blind and lighting control and automation systems. Also, Kang et al. (Citation2017) and Mujan et al’s (Citation2019) findings show that visual comfort has a positive impact on OP. On the other hand, Leaman and Bordass (Citation1999) findings show that lighting is insignificant with OP.

Daylighting and lighting impact on COVID−19 with indirect ways. Because the daylighting and light impacts on the occupants’ moods and can cause depression, which is the weakness of the occupants’ immune systems (Lima et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the rate of satisfaction was lower regarding lighting at home compared to offices during the period of obligating workers to work remotely during the pandemic (Umishio et al., Citation2022).

Consequently, the occupants’ health is fragile when faced by COVID−19 attacks. Moreover, daylighting and lighting benefit human beings in enabling them to produce Vitamin D (Webb, Citation2006). In daylighting, humans can obtain the required Vitamin D at the right time through exposure to daylight. An additional shortage of Vitamin D makes the human body susceptible to COVID−19 attacks (Lanham-New et al., Citation2020). This leads to the following hypothesis:

H4

Lighting and daylighting has a positive and significant impact on OP.

2.3.4. Noise and acoustics and COVID−19

However, to the best of the authors´ knowledge, there are very few publications that discuss the issue of the impact of noise and acoustics on OP. A source of noise affects each occupant differently source (Roskams et al., Citation2019). Leaman and Bordass (Citation1999) findings show that noise is most strongly associated with OP. In addition, the rate of satisfaction was higher regarding sound at home compared to offices during the period of obligating workers to work remotely during the pandemic (Umishio et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, Roskams et al. (Citation2019) and Lee and Aletta’s (Citation2019) findings indicate that acoustic comfort in open-plan offices has a large effect on OP and the effect appears with lower interactivity between colleagues and the perceived disturbances in concentration and the difficulties caused by speech and other factors. From studying the relationship between office type and conflicts in the workplace, Danielsson et al. (Citation2015) findings show that noise had an impact on conflicts in the workplace. These have side effects on OP. B. Haynes et al. (Citation2017) findings highlight that noise, distraction, and loss of privacy impact on OP. As reported by Seddigh et al. (Citation2014), noise in the workplace increases the occupants’ symptoms of stress. Also, Kang et al. (Citation2017) and Mujan et al. (Citation2019) findings show that acoustic comfort has a positive impact on OP. In addition, DiBlasio et al.’s (Citation2019) findings prove that noise reduces OP and increases their symptoms of mental health problems. Also, Kang et al. (Citation2017) results emphasize that, in university open-plan research offices, the quality of the acoustic environment impacts greatly on OP. More specifically, conversational noise has a negative and significant impact on OP. Kang et al. (Citation2017) and Rasheed et al. (Citation2019) results are consistent in showing that noise has a highly significant impact on OP.

On the other hand, few researchers have indicated that there is a positive side to noise and acoustics. In 2015, Rasila & Jylhä presented one positive effect of noise by mentioning that it may increase OP through keeping the occupants awake and by teaching newcomers timely and relevant feedback from their co-workers. Moreover, Klemmer and Snyder’s (Citation1972) results mention the importance of talking among occupants, where 50%−80% of working hours involved communication between them. Findings of (Paunović et al., Citation2011) proposed that increasing as their relationship with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates as results to noise and acoustics. Therefore, the symptoms of COVID−19 are increasing with existing of noise and acoustics. The previous literature leads to a proposed hypothesis:

H5

Noise and Acoustics has a positive and significant impact on OP.

2.3.5. Office layout and COVID−19

Decision makers have moved their interests from teamwork and employees’ conflicts to office layout (Khoshbakht et al., Citation2020). Results of World green building (Council, Citation2014) conclude that office layout affects OP. Bordass and Leaman’s (Citation2005) findings mention the essential role of office layout in the work environment. All kinds of offices relate greatly to OP (Al Horr et al., Citation2016). In addition, from investigating IEQ’s impact on OP, Kang et al. (Citation2017) findings show different outcomes depending on the different types of office layout.

There are many different types of office layout. Khoshbakht et al. (Citation2020) divided the office layout into two categories, namely, the Open-plan office and traditional solo offices. Open-plan offices contain large numbers of occupants, whereas solo offices (traditional offices) contain only one or two occupants. However, Duffy et al. (Citation2003) results mention four types of offices. These are as follows: Hive (cellular and open plan suitable to low interaction and individual work); Cell (suitable to individual work); Den (suitable to high group working); and Club (suitable to knowledge work). Open plan offices have a lot of benefits such as increasing teamwork, communication among occupants, reducing the costs and promoting shared values (Brennan et al., Citation2002; Khoshbakht et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, solo offices achieve privacy, reliable visibility and support more storage spaces (Khoshbakht et al., Citation2020). B. P. Haynes (Citation2008a) argues that open plan offices with high interactions among occupants have a positive impact on OP. Noise increases in open-plan workspaces with a high density of occupants, which may hinder concentration, and studies show employee dissatisfaction with such layouts (Ford et al., Citation2022).

The results, offered by Sundstrom et al. (Citation1980), Hedge (Citation1982) and Brennan et al. (Citation2002); indicate that open office has a negative effect on OP. Additionally, B. P. Haynes (Citation2008b) findings indicate that distraction has a negative impact on OP. Therefore, Brennan et al. (Citation2002) findings recommend that organizations should design their open office protocols to control the occupants’ behaviors and to reduce the number of disturbances. In addition, Hedge (Citation1982) recommends that the occupants be educated and trained about the open plan office. As reported by Candido et al. (Citation2019), interior design is essential in increasing OP and, more particularly, in open-plan offices. Also, Sakellaris et al’s (Citation2016) findings mention that office layout includes office decoration and the amount of privacy.

Ong et al. (Citation2020) report that coronavirus (COVID−19) lives on surfaces for hours or days. Moreover, all precautions, such as medical masks, goggles, and gloves, will not succeed in protecting those occupants who are in contact with contaminated surfaces and do not wash their hands (Adams & Walls, Citation2020). Therefore, those, people (cleaning staff), who are responsible for cleaning and sterilizing workplaces, should clean continuously with disinfectants the surfaces, personal items, such as mobile phones, keyboards, and other items. In addition, the company’s management should support occupants with meticulous hand hygiene and sterilization. Therefore, the managers should reallocate the occupants to solo offices (closed offices), which contain as few occupants as possible; and achieve social and physical distancing. Also, they should improve the offices’ air ventilation and allow daylighting and, where possible, add more windows. In 2020, the WHO formulated a group of measures to ensure occupant healthcare. These measures are such as: wearing masks, gloves, and face shields; prohibiting occupants meeting in groups; establishing a medical isolation room in the workplace; increasing the distance between offices by 1.5 m and 2.0 m to minimize the transfer of the infection; and sustaining a virtual social connection between work colleagues. Furthermore, open office layouts have been linked to sick building syndrome (Ford et al., Citation2022). Based on the literature we formulate the following hypothesis:

H6

Office layout has a positive and significant impact on OP.

2.3.6. Biophilia and views and COVID−19

In the literature, several researchers, Wilson (Citation1984), Kellert and Wilson (Citation1993), Lundberg (Citation1998) and Griffin (Citation2004) have motioned to bring to human beings’ attention to associate biophilia and interaction with nature in their daily lives. Al Horr et al. (Citation2016) and Sanchez et al’s (Citation2018) findings indicate that there is a positive relationship in the workplace between the natural view and OP. As reported in Elzeyadi’s (Citation2011) study, poor views have a statistically significant impact on the occupants’ leaving hours. Davidson’s (Citation2015) and Almusaed’s (Citation2018) findings indicate that natural light and views of green spaces increase occupant’s productivity by 6%. Furthermore, Almusaed’s (Citation2018) findings discuss the impact of a natural view on the occupants’ moods and stress levels. (Gray & Birrell’s, Citation2014) results indicate that biophilic design has a highly positive effect in increasing OP. (Berger et al., Citation2022) found that plants had a significant effect on respondent’s emotion and aesthetic preference. Sanchez et al. (Citation2018) define biophilic design as the interactions and communications between human needs and nature. Mohora’s (Citation2019) results are consistent with earlier studies that the absence of a natural view has an immediate negative impact on OP.

Also, there is an indirect relationship between biophilia and views and COVID−19. According to Hartig et al. (Citation2014), a natural view has an essential impact on reducing depression. In addition, Gidlow et al. (Citation2016) findings indicate that the natural environment increases the inspiration and refreshment of individuals. Moreover, Ulrich’s (Citation1983) and Cox et al. (Citation2017) findings conclude that nature has a significant impact on the individuals’ mental health. Therefore, each company should do its best to create biophilia to achieve a bulk of benefits of renewing, refreshment, increasing aspiration and reducing the stress of occupants in the workplace (Toyoda et al., Citation2020). Consequently, the design of windows has a role to reduce depression (Hunter et al., Citation2019) and to create a positive mood (McMahan & Estes, Citation2015). In the absence of the natural environment, the alternative is recreated nature, known as “biophilia”, such as natural images, designs, and videos (Living & Start, Citation2020). Therefore, the roles of the natural view and biophilia are essential elements in combatting the threats posed by COVID−19. Accordingly, Salama’s (Citation2020) findings confirm the increasing importance of biophilic design after the COVID−19 pandemic. Consequently, the improvement of human beings’ psychological aspects is vital to supporting and increasing the human body’s immune system and, in turn, overcoming the probability of damage from COVID−19 (Centers for disease control and prevention [CDC], Citation2020). After reviewing the literature, we posit the following hypothesis:

H7

Biophilia and views have positive and significant impacts on OP.

2.3.7. Location and amenities and COVID−19

While location is not a direct part of the work environment (Al Horr et al., Citation2016), it plays an essential role in supporting the occupants’ lives. Also, amenities make it easier for the occupants to interact and become involved in work office activities. World green building Council (Citation2014) describes four types of amenities. The first type is the available services local to the building (e.g. shops; restaurants; post office; leisure facilities; healthcare facilities; childcare). The second type is any services within the buildings (e.g. canteen, onsite childcare facilities, gym, laundry/dry-cleaning service, etc.). The third type is the local public realm in terms of maintenance standards and perceptions of personal security (e.g. please provide photographs to illustrate aesthetics). The fourth type is any communal spaces conducive to interaction with colleagues (and people from adjacent enterprises). As indicated by Haider et al. (Citation2013) findings, when occupants stay nearer the locations of their offices, the travelling cost reduces because less fuel is consumed. They mention, also, a direct relationship between the time spent on commuting and stress. When occupants practice athletics for a few minutes every day, their moods and desire to work increases as does their OP.

Leaman (Citation1995) and El Asmar et al. (Citation2014) discussed the amenities that affected OP. Haider et al. (Citation2013) findings conclude that occupants, who face traffic congestion and spend a lot of time reaching their workplaces, suffer from a lot of the symptoms of stress and. From discussing the importance of facilities to boost OP, Duffy et al. (Citation1992) recommend that offices and workplaces should be well-equipped with IT infrastructures and should become more footloose. Moreover, amenities increase the occupants’ trust toward the company and motivate them to boost OP (Al Horr et al., Citation2016). OP affects the availability of amenities and services, such as transportation and the quality of the public realm. In light of the previous, we assumed the following hypothesis:

Within the COVID−19 period, the distinction among organization appears in the power of their IT infrastructures and how to serve, support and communicate with occupants and customers and provide a highly quality service. Therefore, internet services and supported applications have significant effects on increasing OP through working from a distance. Companies should check on their occupants every day at the workplace before they start their work. Moreover, they should prepare an isolation room and be in continuous contact with specific doctors to confirm the occupants’ healthcare and safety. Inadequate home workspaces negatively affected employees’ mental health and well-being. This is during the period of COVID 19. That period saw a drastic change in work practices, with forced work from home. This indicates the importance of employee satisfaction with their work environment, which will support their return to office spaces after the COVID−19 pandemic (Ford et al., Citation2022).

H8

Location and amenities have positive and significant impacts on OP.

2.4. Measurement of Occupant Productivity (OP)

After reviewing more than 10 surveys, Peretti and Schiavon (Citation2011) conclude that there are no standardized methods to survey OP. While there is an open discussion about measuring IEQ, Al Horr et al. (Citation2016) findings highlight three schools of thought to measure OP. The first school considers occupant surveys to be the main tool to measure Occupant Productivity. Researchers can depend only on surveys (Peretti & Schiavon, Citation2011; Rajat et al., 2020). They mention that surveys have been applied mainly to office buildings as a measurement of OP. B. P. Haynes (Citation2008a, Citation2008b) study considers a self-assessed measure to be a justifiable approach. A survey can be conducted by the paper-based method (face-to-face approach) or via an electronic site (sending site link to a target sample). The second school has used surveys in addition to physical measurements (Bluyssen et al., Citation2011; Epa, Citation2003; Frontczak et al., Citation2012; Peretti & Schiavon, Citation2011; Toe & Kubota, Citation2013; Vischer, Citation2008; Wargocki et al., Citation2012). Moreover, the occupants’ responses to physical environment may be influenced by a range of complex factors such as physical measurements (e.g. psychological expectations, physical conditions, experience, etc.). Moreover, environmental conditions in buildings are transient and are frequently difficult to measure with accuracy and precision. The third school has used indirect assessment of OP. Indirect assessment of OP includes many measurement indicators such as employee’s absenteeism rate, the number of hours worked each week, number of employee’s complaints and the rate of employee turnover (Bordass et al., Citation2001; Feige et al., Citation2013). During the annual performance, these measurement indicators can be used to calculate employee productivity.

In summary, after an extensive review of the literature on the impact of IEQ on OP, there is still a gap in the debate about the effect of IEQ on OP. Most researchers focus on four main components of IEQ, but this research studied the impact of seven components of IEQ (indoor air quality and ventilation, thermal comfort, lighting and daylighting, noise and acoustics, office layout, biophilia and views, location, and amenities) on OP. Accordingly, it is essential to cover all components of IEQ and its impacts on OP. Moreover, there are few research studies related to telecommunications companies and, more specifically, in KSA. As a result of the COVID−19) pandemic and all measures to combat it, the companies tend to apply all measures in the workplace. There is a need to develop IEQ to make it more suitable to higher OP and for use as a powerful tool in dealing with the threats posed by COVID−19. Therefore, this study is one of the first to try to formulate a full picture of IEQ during the COVID−19 pandemic and concerned with OP in the telecommunication companies located in KSA’s Eastern Province.

3. Methodology

From reviewing the previous studies, the following Figure is developed, a model to assess IEQ components and to measure OP in telecommunication companies in KSA’s Eastern Province. In addition, the model measures the effect of IEQ components on OP through their personal assessments. Therefore, the following section outlines the research method.

3.1. Participants

In many countries, the telecommunications sector is of great importance in terms of investment and national income. The telecommunication sector in Saudi Arabia is a significant employer, offering employment opportunities across various roles and functions. Major telecommunication companies such as Saudi Telecom Company (STC), Etihad Etisalat (Mobily), and Zain Saudi Arabia employ a large workforce to manage their operations, customer service, network infrastructure, and technological advancements (KSA vision, Citation2030). The Saudi telecommunication market was valued at approximately $14.5 billion in 2020 and is projected to reach $17.4 billion by 2025) (Statista, Citation2023). The number of occupants working in the field of communications and information, as reported by the subscribers subject to social insurance systems and regulations, reached approximately 123,300 occupants by the end of the previous year, 2022. Saudis accounted for around 62.2% of the workforce, while foreigners represented 37.8%. The proportion of occupants in the sector the Eastern region with 7,109 occupants. The population of study consists of all the occupants of telecommunication companies in KSA’s Eastern Province. The respondents were in various departments of managerial level, for example, marketing, human resources, information system, financial management, and customer service.

3.2. Construct measurement

As shown in Table , the researchers based the construction of the components of IEQ and OP structures on many studies that are centrally related to research questions.

Table 1. The variables’ measurements of IEQ components and Occupants’ Perceived Productivity (OPP)

The researchers divided the framework into three parts. The first part is concerned with estimating OP on the seven components of IEQ. The second part measures OP from the personal self-assessments. The third part is concerned with the effect of the elements of IEQ on OP. In this study’s model, the independent variable is the IEQ components; these are measured by seven main antecedents which are Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation, Thermal Comfort, Lighting and day Lighting, Noise and Acoustics, Office Layout, Biophilia and Views, and Location and Amenities. The dependent variable is the OP, which expresses each occupant’s viewpoint of his/her productivity having regard to the comfort factors provided by the workplace. Before the study questionnaire was approved, we conducted a pilot study by using a sample of 35 occupants. Thereafter, we collected and analysed the data to develop the questionnaire and to check its reliability. Then, to check the internal consistency of the questions, we conducted Cronbach’s α and exploratory factor analysis. For measurement purposes, we used a five-point Likert scale with 5 being (Strongly Agree) and 1 being (Strongly Disagree) for OP and 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied) for measuring IEQ components.

3.3. Research questionnaire

The study is based on the development of the questionnaire of IEQ and productivity which were tested in previous research studies. The questionnaire consisted of three sections relating to IEQ, productivity, and personal data. The researchers employed validation procedures to test the questionnaire. Then, it was reviewed by three expert colleagues. We based on questionnaire’s designing according to Zeisel’s (Citation2006) Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) design and summarized by Preiser (Citation2002) in the National Academy Report Learning from our Buildings.

We narrowed the number of questions through validity and reliability testing at the pilot study stage. The remaining (39) items comprised the basis of the questionnaire used in the main survey. The final questionnaire consists of three parts. Part 1 is designed to collect the respondents’ personal data which include gender, age, education level, and monthly income. Part 2 is designed to collect overall assessment of OP by rating on a 5-point scale from 1 (very disagree) to 5 (very agree). Part 3 involves the occupants’ perceptions about the seven key IEQ aspects (Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation, Thermal comfort, Lighting and day Lighting, Noise and Acoustics, Office Layout, Biophilia and Views, and Location and Amenities) by rating them on a 5-point scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

3.4. Data collection and sampling

This study’s sample is occupants in telecommunication companies in KSA’s Eastern Province. The researchers used on Krejcie and Morgan’s (Citation1970) sampling table to select the total sample. The random sampling technique was executed. The questionnaire, which we used, was first designed in English, then translated into Arabic by native speakers and, finally, back into English to ensure accuracy and clarity of meaning. The selection process of the respondents launched randomly according to their proportion at these companies. The researchers informed them about aim of this study and, in addition, the answers would be confidential and used for scientific research purposes only. Researchers conducted the survey only as a paper and pen version. All versions were in the Arabic language and took into consideration the education of the participants. Then, distribution process began with 500 printed copies of the questionnaire to the telecommunication companies’ branch managers in nine provinces in KSA’s Eastern Province (Zain

—Mobily - STC). The group of data collecting team visited every branch to give the copies to the manager of every department. Each manager, in turn, distributed to the employees in his department, and then what was completed was collected, with the passage of the data collection team every week to collect what has been achieved. The distribution process of the questionnaires was in one stage and collected the questionnaires in 7 months. The researchers received back a total of 420 questionnaires, of which 385 were valid (a valid response rate of 91%).

The results of the questionnaire reveal that out of the 385 respondents to the questionnaire, 327 were male and 58 were female. The percentage of female was very low, which it copes with women employment in KSA (HRSD report, Citation2020; Samargandi et al., Citation2019). The largest percentage, approximately 50%, of the respondents were aged between more than 20 years and less than 30 followed by 34% whose ages ranged between more than 30 and less than 40 years. The other ages were less than 15% of the study sample. As for the respondents’ level of education, the largest percentage of them, more than 54%, had a bachelor’s degree. This was followed by 32% with an average education ratio and, finally, and 10.5% have higher degrees. As for the number of years of experience, more than 50% of respondents have less than 5 years of experience. While the percentage of respondents who have more than 5 years of experience and less than 10 years reached 33% and the remaining percentage is respondents with more than 10 years of experience.

4. Data analysis and results

The data was entered into SPSS 24 V and was coded in specific variables. We used different statistical tests to quantitatively analyse and interpret the data using deferent. First, we tested the statistical reliability by using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient test. Second, we used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) construct validation, the evaluation of measurement invariance, and the process of scale development to examine the latent structure of a test instrument (Brown & Moore, Citation2012). Researchers used structural equation modelling to test the structural relationships using AMOS 23 V. The following sub-sections describe the results of the analysis.

4.1. Reliability and validity analysis

The study used Cronbach’s alpha to calculate the reliability of the items that make up the questionnaire factors and to assess the overall consistency of the questions. As shown in Table , the Alpha Cronbach coefficient in all elements of IEQ exceeds 0.6; this is the percentage accepted by (Hair et al., Citation2014). IEQ elements were ranked according to the Cronbach Alpha as follows: Noise and Acoustics, Location and amenities, Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation Office layout, Biophilia and views, Lighting and daylighting, and Thermal comfort in order. Their results are 0.842, 0.819, 0.753, 0.752, 0.728, 0.683, 0.60, respectively. While, as shown in Table , Cronbach’s alpha of the OP variable was 0.808.

Table 2. Validity and reliability results

Researchers conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to understand the construct variables of OP, and IEQ variables, and to assess the structure of the observed measures for the five independent variables and the other variables. Then, the study carried out CFA with maximum likelihood as the estimation method.

4.2. Hypotheses testing

We applied (CFA). Table shows the suitability of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model to test the data with the proposed model. The researchers used multiple criteria to evaluate the fit of the model, such as Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), the Normed Fit Index (NFI), RMSEA, and Incremental fit index (IFI). In total, there were 31 items for IEQ and 8 items for OP. During the CFA, the researchers excluded weak items to improve the model with criteria of eigenvalues greater than one. According to Hair et al. (Citation2014), all indexes come in the acceptable range as shown in Table .

Table 3. Model fit

The results also indicate that most of factor loadings were greater than the suggested standard of 0.7 except for some items are below the optimal values but they are still acceptable according to recommended value greater than 0.5 suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2014). So, the researchers kept these items because these items are contextual and theoretical relevance. Furthermore, the AVE and CR for latent construct and all constructs more than 0.5 and 0.7 for CR. The discriminant validity was conducted by comparing the R2 between the corresponding factors to the AVE values and none of R2 exceeded the AVE values. The results of the overall measurement model by CFA were fit as shown in Table . These results enabled us to move on to analyzing the structure model.

Table 4. Results of CFA

4.3. Structural equation modelling

To examine the effect between OP and the component elements of IEQ, we conducted the structural relationships in the developed model between IEQ components and occupant’s productivity. First, we claim the goodness-of-fit indexes for the structural model. Secondly, path analysis for hypothesized structure. The results confirmed on the acceptance of structure model and fit the data well (GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.89, CFI = 0.961, NFI = 0.923, RMR = 0.034, and RMSEA = 0.048). Accordingly, all measurement and structural models were within the acceptable criteria. As shown in Figure , the SEM results show that the R2 0.84 which confirmed on all IEQ components explained 84% of the variance in occupant’s productivity.

The findings showed a positive and significant relationship between the OP and between Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation, Noise and Acoustics, Lighting and day Lighting, Location and amenities, and Office layout. The findings also showed a negative and significant relationship between OP and Thermal comfort, and Biophilia and views. The results showed that all paths’ coefficients were statistically significant and in the positive direction, except for one path between OP and Noise and Acoustics as shown in Table .

Table 5. Summary of the results of structure model*

5. Discussion

This study was applied to the telecommunication companies in KSA Eastern Province because of their impact on the national economy and investment. The telecommunication companies’ buildings are divided into open halls for customer service in which the occupants interact with customers and the closed offices in other parts of these buildings are where other administrative and executive activities are carried out. Through the previous results as shown in Table , it became clear that the hypothesis stating that “Biophilia and views have significant impacts on OP” was rejected. This is due to the collected field data showing that those surrounding buildings do not have landscapes or green spaces and, also, inside these buildings, there are no plants or landscapes. However, these companies benefit from internal spaces by setting up screens to display their services and there are places to display the devices that they sell to their customers. The study’s results differed from those of Elzeyadi (Citation2011), Davidson (Citation2015), Almusaed (Citation2018), Sanchez et al. (Citation2018), Mohora (Citation2019), and (Berger et al., Citation2022).

This study’s results indicate the negative relationship between the thermal comfort factor and OP. Therefore, the hypothesis stating that “Thermal comfort has a positive significant impact on OP” is rejected. This study’s finding differs from those of Kang et al. (Citation2017), Lipczynska et al. (Citation2018), Mujan et al. (Citation2019) and Kaushik et al. (Citation2020). This means that the telecommunication companies are facing a problem related to low occupant satisfaction with the prevailing temperature in the work environment. The occupants’ satisfaction with the rates of temperature varied according to the workplace. It is possible to increase the temperature in the customer’s waiting halls due to the large number of people present in this place while, at the same time, occupants in closed offices may experience a lower temperature. The findings of this study are consistent with the findings of (Umishio et al., Citation2022).

In the light of the COVID−19 pandemic, it is expected that, through the application of precautionary measures, the companies’ top management will pay a great deal of attention to the thermal comfort component. Such measures will include physical distance within the workplace and more particularly the halls where the occupants deal with customers. This which may affect the level of satisfaction with the prevailing temperature in that place. This study’s results indicate the positive relationship between the lighting element and perceived productivity. Therefore, the hypothesis stating that “Lighting and daylighting has a positive and significant impact on OP” is accepted. This result is consistent with those of Kang et al. (Citation2017), Mujan et al. (Citation2019), and (Umishio et al., Citation2022). It is expected that after the COVID−19 pandemic the institutions will change their usual method of designing work offices to allow sunlight to enter and reach the largest possible area inside work offices. This is because the findings of some recent studies indicate that the sun’s heat kills 90% of COVID−19 within 6 minutes (National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center)

This study’s results indicate the positive relationship between the noise and acoustics component and OP. Therefore, the hypothesis stating that “Noise and Acoustics has a positive and significant impact on OP” is accepted. This study’s result differs from those of Kang et al. (Citation2017), DiBlasio et al. (Citation2019) Mujan et al. (Citation2019) and Umishio et al. (Citation2022). This study’s result is consistent with that of Rasila and Jylhä (Citation2015). They mention that noise may increase productivity through keeping the occupants’ awake, teaching a newcomer, timely, and relevant feedback from their co-workers. Also, this study’s results are consistent with those of Klemmer and Snyder (Citation1972). They mention the importance of conversations among occupants because communication between them accounts for 50%−80% of their working hours. The respondents to our survey indicate their agreement that the noise and acoustics that occur through the colleagues’ side talk, the movement of colleagues, the sound of machines, such as keyboards and telephones, and sounds outside the work environment contribute to raising OP.

According to the WHO’s precautionary measures against the COVID−19 pandemic applied by the KSA’s Ministry of Health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia which recommend the prevention of social gatherings and divergence, these lead to a reduction in direct frictions between occupants and the dependence on remote working. Therefore, this reduces the inconveniences that may lead to a reduction in OP in telecommunication companies. The results, extracted from the statistical analysis, indicate that the element of Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation has a positive and statistically significant effect on OP. Therefore, the hypothesis stating that “Indoor Air Quality and Ventilation has a positive impact on OP” is accepted. This study’s results are consistent with those of Wyon (Citation2004), Kang et al. (Citation2017), Ben David et al. (Citation2019), Mujan et al. (Citation2019) and Rajat et al. (2020), and Aguilar-Gomez et al. (Citation2022)

This means that, in addition to adequate windows, the telecommunication companies’ top management #must pay attention to using air purifiers in the design of offices to allow entry and renewal of natural air. This will lead to the occupants’ feeling comfortable and breathing naturally and will have a positive effect on their OP. Air and ventilation is a very important component of the precautionary measures that have been taken in dealing with the COVID−19 pandemic. Since it is proven that there is a high prevalence of COVID−19 infection in closed places, this necessitates the exploration of new technological methods to raise the quality and purification of air in closed places. This study’s results indicate that the location and amenities have positive and statistically significant effects on OP. Therefore, this means the hypothesis that “location and amenities have a positive impact on OP” is accepted. The results of this IEQ variable are consistent with those of; Duffy et al. (Citation1992), Leaman (Citation1995), El Asmar et al. (Citation2014), World Green Building Council (Citation2014), Al Horr et al. (Citation2016), and Ford et al. (Citation2022)

The proximity of the location to the workplace leads to a reduction in time and effort to reach the workplace. This is reflected directly in the OP. The same applies to the available facilities related to the work location such as the availability of health clinics and transportation, places of entertainment, places of worship and restaurants. As a result of the difference or change in working methods due to the COVID−19 pandemic, there has been increased on remote working by using modern programs and technologies provided by many electronic applications to facilitate cooperation between colleagues in the same department and between the different departments involved. Consequently, tasks are performed easier and faster. This leads to the need to strengthen the technological infrastructure in the workplace and the need to train occupants on how to use this technology. This means that the priority has become based on an interest in technological infrastructure to keep pace with what has been imposed by the new variables arising from the COVID−19 pandemic in a world concerned with physical divergence for the safety of occupants and the safety of others.

It is expected that the importance of medical facilities and support in the workplace will increase, for example, detecting heat before entering the workplace, disinfectants, sterilizers, gloves, and face masks, and ensuring that safety instructions are followed to reduce the spread of infection and, thus, preserve company employees. These are in addition to providing psychological support to treat the psychological effects of the COVID−19 pandemic. As for office layout which is the last component of IEQ, the results show that this element has the most influence on OP. The results are consistent with those of the World Green Building Council (Citation2014) and Kang et al’s (Citation2017). This variable includes several sub-variables, which are closed office layout, open office layout, and decor facilities. As for the effect of sub-elements on OP, the results show that the open office layout has a negative impact on OP. This finding is consistent with the results of Sundstrom et al. (Citation1980), Hedge (Citation1982) and Brennan et al. (Citation2002). This result differs from that of B. P. Haynes (Citation2008a), and Ford et al. (Citation2022)

However, the closed office layout element has a positive impact on OP. This result is consistent with that of Khoshbakht et al. (Citation2020) because the occupants in departments, such as administration and accounting, desire a high degree of independence and privacy and, also, the availability of places to store files and various work-related purposes. Also, the effect of decor facilities has a positive impact on OP. This finding is consistent with those of Sakellaris et al. (Citation2016) and Candido et al. (Citation2019). This indicates that the attractive wall colors have a direct impact on the occupants’ mood and psychological state. This is reflected in the OP. The office layout component is expected to be of great importance in the light of the COVID−19 pandemic. According to the precautionary measures, it is necessary to redesign the open offices to suit the spacing procedures and to maintain specific distances between offices to prevent the spread of infection and protect the occupants. For closed offices, consideration needs to be given to reducing the number of occupants in one room to provide good ventilation outlets for air renewal. As for the decor and the color, the importance of designing components, which give optimism to occupants, will become clear and, more especially, in view of the psychological pressures associated with the COVID−19 pandemic.

6. Conclusion and recommendation

This study sought to identify the IEQ components that influence OP. Also, it sought to formulate future recommendations that enable the decision-makers to develop IEQ quality in the presence of the COVID−19 pandemic. This study contributed to improving our understanding and developing the influence of IEQ on OP and more particularly during the COVID−19 pandemic. We collected 385 valid questionnaires before the spread of COVID−19 pandemic. The results will be significant to prepare and develop the work environment after regular return to workplace. The study highlighted the importance of IEQ in combatting and overcoming the threats posed by the COVID−19 pandemic after reopening the economy and occupants returning to the work environment.

The air quality and ventilation may increase the stress through the interaction among occupants (Rashid & Zimring, Citation2008). After back to the workplace the pressure on occupants may increase, therefore the organization should develop IEQ, especially improved air quality and ventilation in the workplace. By cleaning and maintaining and renew and adding filtering devices to air quality and ventilation systems will face COVID−19 successfully.

The results of the study showed the importance of IEQ components and their effective role in facing the effects of the COVID−19 pandemic. Specifically, the air quality and ventilation component is an essential element in dealing with respiratory diseases in general and those that result from the coronavirus in particular. On the other hand, the employee’s movement from residence (quarantine) in a closed environment to the workplace (relatively open environment) would affect the psychological state of the occupants. Air quality and ventilation improve physiological and psychological conditions. In addition to the effect of the occupant’s movement and activity in the workplace on the psychological state.

The theoretical model proposed helps the management of the hospitality industry on creating and redesigning a healthy workplace that enables to increase in the occupant’s productivity and defeat the COVID− 19 affects after back to work, as we mentioned above. Practically, the hospitality industry will react to the challenge of COVID−19 effects, by developing the IEQ to increase the occupant’s productivity and reattract customers and deliver safety messages to the clients.

6.1. Practical implication

The results of the analysis revealed a high mean generally in the total evaluation of IEQ. The sub-variables of the occupants’ self-evaluation are arranged according to their Mean as follows: the indoor air quality and ventilation factor; Location and amenities factor; Office layout factor; Lighting and daylighting factor; Noise and Acoustics factor; Thermal comfort factor; and Biophilia and views factor. Additionally, it is clear from this study’s results that companies need to re-visit the elements of IEQ in relation to the internal environment taking into account the effects and data arising from the COVID−19 pandemic. Clearly, the IEQ will change from traditional and physical concentration of the workplace to a virtual work environment. So, amenities components should take more interest and support separately from management. Based on this study’s results, we make the following recommendations to decision-makers, designers, and architects:

Participation of several parties in the design of the work environment, and the involvement of each of the organization’s management and medical bodies and specialists in the design of buildings and offices and their decorations.

Developing the technological infrastructure in a way that contributes to achieving social separation and remote working and, thus, increasing productivity.

The necessity of making some adjustments, such as adding windows that allow the entry of sunlight and improving ventilation outlets to raise air quality in the work environment.

Redesigning the offices in line with the recommended precautions from global and local health organizations in addition to those issued by KSA’s Ministry of Human Resources.

Protecting occupant’s health is key to increase and improve productivity through developing IEQ.

6.2. Theoretical implication

This study provides and enriches the current literature review by studying seven components of IEQ and its effects on OP. Although IEQ and OP are widespread studied among many researchers, few unique research has studied this factor regarding facing COVID−19 pandemic. Hence, the findings recommend that IEQ features influence not only the occupant’s productivity but also influences in facing COVID−19 pandemic in the telecommunications companies. This study’s results led to the acceptance of hypotheses H1, H2, H4, H5, H6 and H8, namely, that IEQ, indoor air quality, and ventilation, lighting and daylighting, noise and acoustics, office layout, and location and amenities have a positive impact on OP. However, this study’s results led to the rejection of both hypotheses H3 and H7, namely, thermal comfort and biophilia and views. This was because of the presence of a negative effect between thermal comfort and OP, and the absence of biophilia and views having a statistically significant effect on OP. In addition, this study will encourage and push toward multidiscipline research among the medicine field, architecture, design, and management.

6.3. Limitation and future studies

The research limitations were that this study applied only to telecommunications companies in KSA’s Eastern Province. The researchers collected 385 valid questionnaires from the target companies before the spread of COVID−19 pandemic between May 2019 and December 2019. The evaluation of the elements of the internal and productive environment depends on the self-evaluation of the occupants investigated among them, and not through measuring devices such as sensors. We intend to conduct further studies to assess the indoor environment in other service and industrial organizations and, more especially, after the COVID−19 pandemic. In the light of the COVID−19 pandemic, we intend to measure the impact of the indoor environment on other important variables such as organizational loyalty, job satisfaction, stress management, and conflict response within the work environment. We will focus on studying the effect of IEQ on organizational behaviors and how the COVID−19 pandemic has affected OP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sayed Hassan Abdelmajeed

Sayed Hassan Abdelmajeed is a full-time Assistant professor in the Department of Marketing, at Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, KSA. He has a degree PhD business administration from Cairo University, MBA in Marketing from Cairo University and MSc degree in Business administration from Suez Canal University. He has more than 15 years of academic experiences at well-known institutions. Currently, he has been teaching several Marketing courses. His research areas of interest are lie in marketing communication, sustainability, creativity, and sports marketing, etc

Mahmoud M. H. Alayis

Mahmoud Alayis is a faculty member at Imam Abdul Rahman Bin Faisal University, College of Applied Studies and Community Service. He is very interested in the field of entrepreneurship and human resources. Mahmoud M. Hussein Alayis received his PhD degree in Business Administration from Suez Canal University, Egypt in 2016. His research interests are in human resources, Entrepreneurship, Quality management, and administrative leadership.

Abdalla Zahri Amin

Abdullah Amin is a faculty member at Imam Abdul Rahman Bin Faisal University, College of Applied Studies and Community Service. In addition, he has many publications in Marketing and Business Administration. Abdalla Zahri Amin holds a Ph.D. in Business Administration, majoring in marketing, with a specialization in service marketing. He is interested in service marketing and brand-related knowledge. He is also interested in entrepreneurship and contributes in the academic field to developing the entrepreneurship course and specialized knowledge in the field. Abdalla Zahri Amin holds a Ph.D. in Business Administration, majoring in marketing, with a specialization in service marketing. He is interested in service marketing and brand-related knowledge. He is also interested in entrepreneurship and contributes in the academic field to developing the entrepreneurship course and specialized knowledge in the field.

References

- Adams, J. G., & Walls, R. M. (2020). Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. Jama, 323(15), 1439–29. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3972

- Afful, A. E., Osei Assibey Antwi, A. D. D., Ayarkwa, J., & Acquah, G. K. K. (2022). Impact of improved indoor environment on recovery from COVID-19 infections: A review of literature. Facilities, 40(11/12), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/F-02-2022-0021

- Agarwal, N., Meena, C. S., Raj, B. P., Saini, L., Kumar, A., Gopalakrishnan, N., Kumar, A., Balam, N. B., Alam, T., Kapoor, N. R., & Aggarwal, V. (2021). Indoor air quality improvement in COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Cities and Society, 70, 102942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102942

- Aguilar-Gomez, S., Dwyer, H., Zivin, J. S. G., & Neidell, M. J. (2022). This is air: The non-health. Effects of Air Pollution. https://doi.org/10.3386/w29848

- Alayis, M. M. H., Amin, A. Z., & Abdelmajeed, S. H. (2020). The Effect of Indoor Environment Quality on Customer Service Employees’ Creativity in Telecommunication Companies in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity & Change, 13(4), 1203–1222.

- Al Horr, Y., Arif, M., Kaushik, A., Mazroei, A., Katafygiotou, M., & Elsarrag, E. (2016). Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: A review of the literature. Building and Environment, 105, 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.06.001

- Al Mamun, F., Hosen, I., Misti, J. M., Kaggwa, M. M., & Mamun, M. A. (2021). Mental disorders of Bangladeshi students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 645–654. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S315961

- Almusaed, A., (Ed.). (2018). Landscape architecture: The sense of places, models and applications. BoD–Books on Demand. https://doi.org/10.5772/68006

- Amerio, A., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Aguglia, A., Bianchi, D., Santi, F., Odone, A., Costanza, A., Signorelli, C., Serafini, G., Amore, M., Capolongo, S., & Costantini, L. (2020). COVID-19 Lockdown: Housing Built Environment’s Effects on Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5973. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165973/

- Ashrae guidline (Ed.). (2020). Iwrapper. Retrieved December 23, 2022, from https://ashrae.iwrapper.com/ASHRAE_PREVIEW_ONLY_STANDARDS/GL_12_2020

- Azuma, K., Yanagi, U., Kagi, N., Kim, H., Ogata, M., & Hayashi, M. (2020). Environmental factors involved in SARS-CoV-2 transmission: Effect and role of indoor environmental quality in the strategy for COVID-19 infection control. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 25(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-020-00904-2