?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

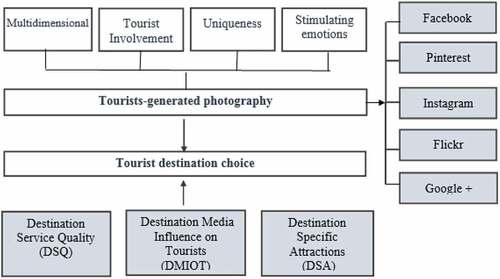

The aim of this study was to examine whether Tourist-Generated Photographs (TGP) and images shared by them, on online media channels can affect tourist destination decisions. The study conducted descriptive-survey research. The statistical population of the research included tourists who traveled to this city on 15 May 2022H15 May 2022 (Shiraz National Day). Simple random sampling was used to determine the research sample and distributed questionnaires among 415 tourists in six five-star hotels in Shiraz. The data collection tool is a researcher-made questionnaire that evaluates each dimension in the majority of the questions. According to the results, four factors, including multidimensionality, tourist involvement, uniqueness, and stimulating emotions by the photo, can have a significant effect on the impact of tourist-generated photography. Findings also revealed that three factors of service quality, media influence on tourists, and destination-specific attractions have a substantial impact on tourists’ destination choices. In the post-pandemic era cyberspace and its tourism function will be of great value, and pictures are the way tourists communicate with tourism and travel. Also, tourists’ photos in cyberspace can help destination marketing. The research findings emphasize that the tour operators of the Shiraz metropolis can take advantage of cyberspace more and better develop their tourism industry for post-pandemic travel.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The article “Application of Tourist-Generated Photography in Tourist’ Destination Choice: The Case of Shiraz Metropolis in Iran” highlights the importance of Tourist-Generated Photography (TGP) and its impact on tourists’ destination decisions. The research results showed that TGP factors such as multidimensionality, tourist involvement, uniqueness, and stimulating emotions have a significant effect on the impact of tourist-generated photography. Additionally, service quality, media influence, and destination-specific attractions were found to have a substantial impact on tourists’ destination choice. In a time where the tourism industry is facing a crisis, the use of cyberspace and TGP can play a significant role in managing tourists’ psychological needs. The findings of this research suggest that tour operators in Shiraz metropolis can take advantage of cyberspace and develop their tourism industry to attract post-pandemic travelers. The study’s implications can be useful for policymakers, tourism managers, and stakeholders to promote their destinations and enhance tourists’ experiences.

1. Introduction

During the COVID−19 pandemic era, online media assumed a more important role in the life of tourists, so it became an integral part of tourists’ lives (Mousazadeh, Ghorbani, Azadi, Almani, Zangiabadi, et al., Citation2023). During the quarantine times, tourists were only in contact with destinations using online media, and in this situation, a close relationship between tourists and the media was formed (Ghorbani et al., Citation2023). In other words, the media was the only link between the destination and the tourist during the pandemic, and now it can affect many tourists’ preferences and destination choices (Mousazadeh et al., Citation2023). On the other hand, the number of travel bloggers based on smartphones has also increased, and tourists are exposed to more quality and multi-dimensional images of diverse and new destinations, which can be effective in choosing a destination (Morabi Jouybari et al., Citation2023). Tourists photograph whatever seems interesting to them such as landscapes, nature, people, and things that correspond with thoughts of otherness and anything eye-catching, charming, or passionate (Höckert et al., Citation2018). According to Rezaei et al. (Citation2018), Information sources and destination image, information sources and motivation and travel experience, and destination image are related. Tourists are willing to share their travel pictures in online media along with interesting narratives. These photos are usually accompanied by exciting narratives that usually discuss the routes to reach the destination, risks and challenges, unique features, and the culture of a destination. Simultaneous sharing of photos and travel narratives can introduce the destination more clearly to other tourists (Mousazadeh, Ghorbani, Azadi, Almani, Zangiabadi, et al., Citation2023). Similarly, a lot of studies have shown that tourism and photography are inherently interlaced in such a way that they cannot be easily separated, and camera lenses have captured notable segments of tourist experiences as well as practices for a long time (Conti & Lexhagen, Citation2020; Qin et al., Citation2019; Suharyanto et al., Citation2020). In line with this notion, the emergence of online media has sped up the dissemination of travel experiences causing a new phenomenon known as smart marketing which is identified as interchanging and communicating a great amount of travel-related information by tourists through online media (Ghorbani, Danaei, Barzegar, et al., Citation2019). Owing to this, tourists have a chance to share their travel experiences online, using electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) (Kimmel & Kitchen, Citation2014). Social media content, which is generated and shared by public individuals, rather than paid promoters, through online communication channels is known as “user-generated content” (UGC) (Santos, Citation2022). Likewise, travel-related content produced and uploaded on social media by tourists is called “tourist-generated content” (TGC) (Sun et al., Citation2015). In line with this, Terttunen (Citation2017) asserted that visual elements constitute a great segment of traveling and are included in almost every social media platform, and photographs as one of the most impressive visual contents shared via online media, have become a focal point of so many researchers as well as marketers to investigate the characteristics of an influential image which impact on travelers’ destination choice and can lead them to find new strategies in this context. Thus, this paper aims to survey the impact that TGC, particularly in the form of photographs (i.e., TGP), has on tourists’ behavior in choosing a destination after being shared through various channels of communication. It can contribute significantly to a sustainable income (Faraji et al., Citation2021). Iran suffers from significant negative imagery in tourist-generating markets for decades, making this process even more complex. Old photos republished in cyberspace by travelers suggest that tourists travel in their memories, even non-physically (intangibly) when they share their diaries of past trips in the form of photos when they are not in a condition to travel (Chilembwe & Gondwe, Citation2020). It also gives new insights to governments as well as the public to utilize emerging technologies more wisely and offer the uppermost usage of such advances for post-pandemic time (Puspita, Citation2020). This study provides the opportunity for prospective tourists to choose “Shiraz” as their future destination by observing online pictures of this beautiful historical city shared by previous visitors. The most important novelty aspect of the current research is that it examines the characteristics of non-advertising photos that can change the preferences of tourists in choosing a destination and it is looking to identify what characteristics non-advertising photos should have that can change tourists’ preferences in the field of choosing and changing destinations. Therefore, the present study pursues the following questions:

_Non-advertising photos published in online media effective on tourists’ destination preferences?

_What is the most important feature of photos shared in online media that affects destination preferences?

Also, the final goal of the research is to present the relevant model

2. Literature review

2.1. Photography, tourism, and Tourism Destination Images (TDI)

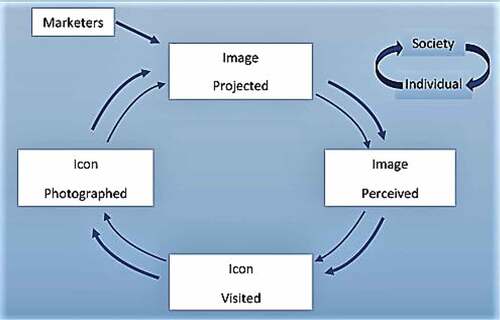

Travel and photography have been tied for a long time together to such an extent that their separation seems impossible (Nikjoo & Bakhshi, Citation2019), and the old saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” is most sincere in the context of travel (Jenkins, Citation2003). “Urry” perceives that a “tourist gaze” creates and mediates tourism. He believes while all feelings such as seeing, smelling, hearing, and touching might be involved in the tourist’s offline experience throughout the journey, the act of gazing (photographing) is the essence of this experience (Li et al., Citation2022). Photographs verify the presence of a tourist at a specific destination (Nikjoo & Bakhshi, Citation2019). Sharing their travel photos gives tourists the chance to produce more meaningful travel experiences (Taylor, Citation2020), which can be widely accessed by an audience and provoke in-depth emotional feedback (Balomenou & Garrod, Citation2019), thereby creating a favorable destination image (DI) in the minds of prospective travelers. “Tourism Destination Image (TDI)” or simply “Destination Image (DI)” is perceived as a totality of attitudes and feelings an individual forms based on the information about a destination from different sources at the time, which develops the mental portrayal of it (Gravari-Barbas et al., Citation2016). TDI is a notion that is of great importance in tourism studies (Hahm et al., Citation2018), and has been emphasized by so many researchers (Liang & Luo, Citation2019; Tan & Wu, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2021). TDI includes three discrete but hierarchically interdependent components: “cognitive”, “effective”, and “conative” (Wang et al., Citation2021). They respectively refer to an individual’s belief or information of attributes or features of a particular destination (cognitive) (Balomenou & Garrod, Citation2019), the feelings or sensations a person links to a specific destination (affective) (Ghorbani et al., Citation2015), and the last one is generated by the contribution of the two formers to building the final “tourist’s behavior” (conative component) (Sparks et al., Citation2013). In this context, Jenkins (Citation2003), suggests a concept called “the circle of representations by illustrating” presenting that there is a link between tourist destination images as symbolic photos and images taken by tourists as actual photos; both sources of photographs are informative and have an impact on each other. The “circle of representation” depicted in Figure illustrates that the pictures of the destination presented by mass media may affect individuals’ beliefs or perceptions and alter their behavior to travel to that specific destination and capture photos similar to those shown by the media (Balomenou & Garrod, Citation2019). Hence, a “hermeneutic circle” develops through following and recapturing the images by displaying them to family and friends to prove their visit. This circle is another factor forming and determining a positive TDI in the minds of potential travelers (Hahm et al., Citation2018).

Figure 1. Circle of representation (Jenkins, Citation2003).

TDI has also been constantly studied in scientific investigations on tourism (Perpiña et al., Citation2019). Although the main focus has been more on those images of the destination that are published for the purpose of marketing, and less attention has been paid to the images published by non-stakeholders. This is while the images published by non-beneficiaries of the destination can update the knowledge and information of online media users (Pan et al., Citation2021). Consequently impacting the final decision-making by individuals. Despite its universal availability and popular use, photography has had a somewhat ambivalent relationship with research methodology. Its potential for serving in academic research had been documented as early as the 1830s. Photographs have since been routinely employed by scientific researchers, not only as a means of collecting and cataloging data but also as furnishing proof of the findings from the analysis of such data (Ghorbani, Danaei, Barzegar, et al., Citation2019).

2.2. Tourist-generated content and tourist-generated photographs

In former times, travel photo-sharing used to be done almost personally, restricted to a close circle of relatives and friends (Singh & Srivastava, Citation2019), usually accompanied by a verbal narration related to the story of each photograph. However, with the advent of digital photography, a basic change was founded in every aspect of travel photography as well as tourism photo-sharing procedure (Prideaux et al., Citation2018), resulting in the audience expanding beyond customary friends and family to a large number of acquaintances and strangers. Over the past decades, information and communication technologies (ICTs) along with the rapid growth of web-based communication channels have altered people’s lives to a large extent (Xia et al., Citation2018). Likewise, in tourism, by the transmission of their travel experiences through various types of media content including images, tourists supply potential travelers with information and other travel-related products or services (F. X. Yang, Citation2017). As a result, users who were traditionally passive receivers and powerless consumers of one-way tourism marketing communication have now turned into active contributors of media content since the end of the 20th century (Mak, Citation2017). The travel experiences shared in the form of visual images, comments, and reviews are accessible to other potential users of online communication channels (Ho et al., Citation2015). Such media content produced and published online by users outside professional practice is called “user-generated content” (UGC). In tourism, UGC is also termed “tourism-generated content” (TGC) or “travel-related content” (Mak, Citation2017), as a great amount of shared content is done by tourists during or after their travel. The significance of UGC (or TGC) in tourism as a powerful tool for gathering information and helping tourists make travel-related decisions (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, Citation2017), has to be considered for the following reasons. Firstly, as tourism is a hedonic experience, travelers desire to make the best out of their travel experience by making the right travel decisions with the help of online TGC available on online social media. Secondly, tourists who do not know about a destination before visiting, trust the information and experience of other tourists for making the best choices as information from other users seems to be more trustworthy than promotional content (Ukpabi & Karjaluoto, Citation2017). Indeed, UGC (or TGC) influences tourists more than promotional content because they believe that it mirrors the actual performance of tourists while traveling. Moreover, TGC has advantages like quick availability, rapid and constant updating, and flexibility for revision according to the needs of users (Timoshenko & Hauser, Citation2019). Similarly, users (including tourists) utilize UGC and TGC in various ways assessing costs and quality of products and services discovering the best destinations, food and entertainment and booking hotels or selecting desired accommodation before their travel. Recent research has shown that UGC has gradually accredited in social media (Nechita et al., Citation2019). Social media also provides people with opportunities to interact and constitute communities of common interests through sharing of media content even with unknown online users (Zhu et al., Citation2016). This practice most likely influences attitudes and beliefs about social standards and, consequently, their behavior (Batat & Prentovic, Citation2014). Yet, in their studies, many researchers claimed that when compared with photos, text cannot completely convey feelings behind seeing, listening, and smelling experienced by a tourist in a destination; a photograph can convey multilayered senses through its visual features. Moreover, while analog photography had limited users due to the prohibitive cost of film and printing process, and a delay between capturing and sharing of photographs, digital photography, on the other hand, has removed such barriers and paved the way for a low-cost simple storing and an easy-to-modify and significantly faster sharing practice (Prideaux et al., Citation2018). Moreover, the emergence of smartphones equipped with high-resolution cameras has hastened the process of photo-sharing with the instant transmission of photographs globally. This phenomenon of taking and sharing photographs through new technologies has thrown open research possibilities in understanding the link between photography and destination image and destination promotion. Nonetheless, a survey regarding this particular format of UGC, i.e., photographs captured and disseminated by tourists known as “tourist-generated photographs” (TGP) as an influential factor in promoting and developing new tourism, is still missing. Hence, this study has been done to evaluate the impact of TGP on tourists’ destination choice; the importance of this paper is due to the major role photographs play in the tourism economy as a vital medium in promoting TD (Gravari-Barbas et al., Citation2016). The tourism sector has been going through various types of crises from time to time since it is highly susceptible and influenced by external factors (e.g., environmental crisis, including geological and extreme weather events; societal and political crisis, including riots, crime waves, terrorist acts; health-related crisis, such as disease epidemics; technological crisis, including transportation accidents and IT system failures; economic, such as major currency fluctuations and financial crises). Irrespective of nature (whether it is human-made or natural) or scope (regional or global) crises always create downtime for tourism. The effects of this pandemic are still revolve around uncertainty and estimated to have a long-term impact (Mousazadeh, Ghorbani, Azadi, Almani, Zangiabadi, et al., Citation2023; Özdemir & Yildiz, Citation2020).

3. Research methodology

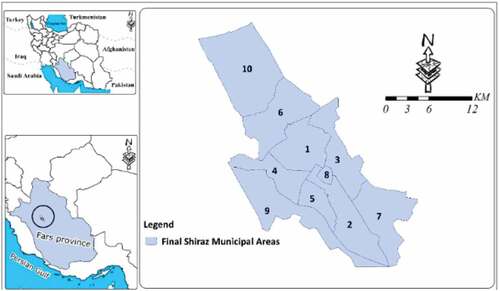

3.1. Study area

Shiraz is one of the most populous cities of Iran and the capital of “Fars Province” located in the southwest of Iran (Figure ). In addition to its nice climate, “Shiraz” is globally popular for its rich culture and long history, literature, and poets’ treasures, various spectacular places, and remarkable monuments. Another great point about “Shiraz” which made it a popular tourist destination is its adjacency to “Persepolis” (Takht-e-Jamshid). This city is one of the main and world-famous touristic cities in Iran which has a variety of unique historical, cultural, and natural tourist attractions, Shiraz has become a popular tourist destination for domestic and foreign tourists. Edward Browne (Citation1893), in his book “A Year Amongst the Persians”, described Shiraz (Shirazes) as follows:

“In Iran, Shiraz, which is known for strengthening the region in terms of historical structure as the most delicate, most innovative, everyone seems to like Shiraz”.

Moreover, as the largest city in southern Iran and one of the most beautiful metropolises in the Middle East, “Shiraz” has extensive potential for being a tourism destination, from literary tourism (Shaykh-Baygloo, Citation2021) to medical tourism (Gholami et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it hosts a large number of tourists from all over the world every year and will be a good population to study.

3.2. Sample

The statistical population of the research consists of tourists who have chosen the Shiraz metropolis as their destination. A simple random method was used to select the statistical sample of the research, and 415 tourists who stayed in 5-star hotels in Shiraz during Shiraz Day participated in the interview (Please see Table ). Ardibehesht 15 is called Shiraz Day in Iran, and every year on this day programs are organized for tourists and residents of this city by tourism organizations.

Table 1. Five-star hotels in Shiraz and the number of distributed questionnaires

3.3. Research instrument and data analysis

The data was collected using a researcher-made questionnaire. The questionnaire contains 28 questions designed in the form of a 7-point Likert scale. 4 questions are designed for each variable. The questionnaire was distributed to the participants on 15 May 2022. Meta-synthesis and experts’ Delphi methods were used to determine the raw and final variables. In the Delphi process, the raw indicators were screened in three stages to obtain the final indicators. According to the initial agreement at the beginning of the work, at least 50% of the experts could give a similar answer to one of the options for each indicator. The final agreement was reached in the third round with at least 55% similar responses, and the final variables were obtained. Finally, in accordance with the sample size and non-normal distribution of data, PLS software was used for data analysis.

4. Designing research hypotheses

First, researchers defined 2 groups of variables with 7 total dimensions (sub-variables) (Table−2). According to Table , the first group which deals with “the impact of Tourist-Generated Photography shared in cyberspace” (TGP)-(A1) consisted of 4 dimensions (sub-variables), and the second group concerned with “Tourist Destination choice” (TDC)-(A2) consisted of 3 dimensions (sub-variables). As demonstrated in Table , the first group’s (TGP) sub-variables respectively are:

Table 2. Variables and sub-variables defined to design the research model resource

“Multidimensionality” (A11), “Tourist Involvement” (A12), “Uniqueness” (A13), and “Emotion stimulation” (A14). The second group’s (TDC) sub-variables include “Destination Service Quality” (DSQ) (A21), “Destination Media Influence on Tourists” (DMIOT) (A22), and “Destination Specific Attraction” (DSA) (A23).

After finalizing the factors, the hypotheses were designed according to Table :

Table 3. Research hypotheses

5. Results

5.1. Correlation of research variables

Pearson correlation for the impact of Tourist-Generated Photography (TGP) shared in cyberspace and Tourist Destination Choice (TDC) was calculated (Table ). The results showed a high correlation (more than 0.5). A correlation above 0.5 indicates a high correlation for research variables (Akgün et al., Citation2020).

Table 4. Correlation analysis of the structures and indexes

5.2. Convergent Validity (CV)

CV is a quantitative measurement that shows the degree of internal correlation and alignment of the measurement items of a category. The narrative concept of the questionnaire validity answers the question of how well the measuring instrument measures the desired feature. Whenever a structure (latent variable) is measured on the basis of multiple items (observable variable), the correlation between its items can be examined by convergent validity. If the correlation between the factor loadings of the items is high, the questionnaire has a convergent validity. This correlation is essential to ensure that the test measures what needs to be measured. To calculate convergent validity, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be calculated. In simple words, AVE shows the degree to which a structure is correlated with its characteristics, and a higher correlation means a higher fit. Fornell and Larker (Citation1981) believe that convergent validity exists when the AVE is greater than 0.5 (Ghorbani, Danaei, Barzegar, et al., Citation2019).

5.3. Calculation of CV (Convergent Validity) in Smart PLS

The principles of calculating convergent validity in PLS software and also the technique of the least partial inputs are fixed, but this software, unlike the Lisrel software, gives the value of AVE and you do not need to calculate it manually. To calculate convergent validity in PLS software, one can just refer to the software output.

5.4. CR (Compound Reliability)

(CR) stands for Composite Reliability. Convergent Validity exists when the CR is greater than 0.7. CR must also be larger than AVE. In this case, there will be a convergent narrative condition (Table ). In short, the following relationships must be established for convergent validity (Ghorbani, Danaei, Barzegar, et al., Citation2019).

Table 5. Convergent Validity

CR > 0.

CR>AVE

AVE >0.5

5.5. Data analysis

Factor Loading (FL): Factor loading indicates the relationship between visible and hidden variables. FL is always between Zero and One. The relationship is regarded as weak when the FL is less than 0.3., and the relationship is desirable when FL is higher than 0.6. According to Table , the level of FL is appropriate (Mousazadeh, Ghorbani, Azadi, Almani, Zangiabadi, et al., Citation2023).

Table 6. Coefficient of FL

Where:

FL < 0.3

Weak

0.3≤ FL ≥ 0.6

Acceptable

0.6 ≤ FL

Desirable

(Ghorbani, Danaei, Barzegar, et al., Citation2019).

In the present research model, according to Table , all the coefficients of the factor loadings of the queries are greater than 0.5, meaning the variance of the indices with their corresponding constructs is acceptable.

5.6. Divergent validity (DV)

Divergent validity is used to describe evidence that measures constructs (Please see Table ). These measurements should not be highly related to each other and not highly correlated with each other. Practically, divergent validity should be smaller in magnitude than convergent validity coefficients (Gearhart, Citation2022).

Table 7. Divergent validity (Dv)

5.7. Hypothesis testing

According to Table , the effect of tourist-generated photography on the destination choice of tourists in the Shiraz metropolis has a coefficient of 0.743. In conclusion, we say that with 95% confidence, the TGPs published in cyberspace have a positive impact on attracting tourists to the Shiraz metropolis:

Table 8. The main hypothesis testing

6. Designing the final research model

After examining the hypotheses, the final research model was designed in Figure :

6.1. Model Goodness of Fit (GOF) Testing

The final step of Structural Equations Modeling (SEM) is to calculate the Goodness of Fit (GOF) of the model. It measures the overall goodness of fit for both the structural and measurement models collectively (Luo et al., Citation2022). The GOF is calculated with the following formula:

GOF interpretation:

GOF ≤0.10 Weak

0.10≤ GOF ≥ 0. 25 Acceptable

GOF ≥0.36 Desirable

If: Avg (Communalities) = 0.738

R2: 0.542

Therefore:

7. Discussion

With the development of technology in developing countries like Iran, the number of online media users and smartphones has increased significantly. On the other hand, the average age of users has also decreased greatly. Also, the number of travel bloggers whose aim is to introduce unknown destinations and access routes is also increasing. Users in different age groups are faced with an onslaught of images and content from different destinations, which can change and replace the destination. Destination planners and stakeholders should not be unaware of the effect of content produced in online media (Ghorbani et al., Citation2021). To investigate this issue, the main purpose of the present study was to examine the role of tourist-generated photography (TGP) in tourists’ destination choices in the Shiraz metropolis, Iran. For better measurement of the research subject, two groups of variables were prepared, and accordingly, the conceptual research model was designed. The first group of variables is related to effective photography criteria in tourism, and the second group of variables is concerned with the criteria for selecting a destination by potential tourists. The criterion was based on the images shared on five social media (Instagram, Facebook, Google+, Pinterest, and Flicker). Based on the software output in Tables , all hypotheses were confirmed (β = 0.743, p < 0.05). The hypotheses consisted of one main hypothesis and seven sub-hypotheses to better assess the issue. In other words, potential tourists in cyberspace who see pictures of the tourist attractions of Shiraz decide to travel to Shiraz in the future after the lockdown ends. Thus, the more a person trusts social media for tourism information, the more he/she gets involved in this media by sharing travel information. This means all the tourist images published from Shiraz in cyberspace can attract potential tourists to this city. As shown in Table , in addition to the main hypothesis, the sub-hypotheses of the research fall into two groups. The sub-hypotheses of the first group are related to the characteristics of tourism photography, and the sub-hypotheses of the second group are related to destination selection factors. According to the first hypothesis in Table (P < 0.05), the multidimensionality of the photo has a significant effect on the impact of tourist-generated photography shared in cyberspace. According to Bull (Citation2020), tourists respond better psychologically to photos that have different dimensions and different elements that should be observed in tourism marketing through photography. The second hypothesis assumes the tourist’s mental involvement considers the features of an effective tourist’s photo. In other words, the photo should psychologically fascinate the tourist’s mind, in such a way that pushes the tourist towards the destination. Hereby, Akgün et al. (Citation2020) argued about enduring involvement in travel motivation and the role of photography in this regard. The third hypothesis, according to Table , discusses respect to the uniqueness of the photo. Similarly, studies show that unique photographs have always attracted humans (Akgün et al., Citation2020). The fourth hypothesis—the last hypothesis of the first group’s hypotheses—evaluates the stimulating emotional feature of a photograph. It focuses on the mental processing of the image in the mind of the tourist. Based on the related result, the photo should stimulate the tourist’s feelings, and provoking the tourist’s feelings is a key factor in the formation of a successful tourism destination image (Ernawadi & Putra, Citation2020). The three hypotheses 5, 6, and 7 which are placed in the second group examine the factors influencing the choice of destination by tourists. The fifth hypothesis considers the quality of service at the destination as one of the factors affecting the tourist’s destination choice. In line with this, Hong et al. (Citation2020) argue that service quality is found to be significantly related to destination reuse. In the sixth hypothesis, the marketing power of the destination media was examined. Accordingly, it is stated that having powerful tourism marketing social media has a significant impact on the followers’ intention to visit a promoted destination (George, Citation2020). According to the result, the more skillful in using online platforms and the more trustful in social media for tourism information people are, the greater their use of social media, sharing comments, photos, videos and reviews related to visited destinations. Thus, the role of tourists might be transformed towards one that involves spreading authentic travel experiences. One implication could be that tourist services suppliers might benefit from the amplitude of the disseminating information process regarding their offers. At the same time, they become aware of the consequences generated by negative experiences of tourists and try to avoid them by offering higher quality services and honestly dealing with the forms of dissatisfaction expressed on social media. Finally, the seventh hypothesis highlights the role of the destination’s specific attractions captured by tourists’ photographs in attracting tourists. With this knowledge, tourism managers and operators at the destination can prepare specific plans in advance to prevent over-crowding in attractions and ensure visitors’ safety and pleasure. Parallel to this, L. Yang et al. (Citation2020) asserted that there are many attributes associated with a specific tourist destination. The research findings emphasize that the tour operators of the Shiraz metropolis as one of the most attractive cities in Iran and the Middle East can use cyberspace more and better to develop their tourism industry. The findings offer useful practical implications. Because this study is set in the general context of infectious diseases, its implications are not restricted to the present COVID−19 outbreak but are general to a broader context. When there is a destination-specific or global outbreak of infectious diseases, such as COVID−19, there is a threat to tourists and the tourism industry, the magnitude of which depends on the scale and severity of the epidemic. The role of photos shared by tourists in cyberspace in maintaining the relationship between society and the tourism industry and reducing psychological effects in the current quarantine situation could be a good choice for future research destination choice. In addition, this research has a significant contribution to the tourism literature and shows important concepts for DMOs in the field of destination marketing. It also enables tourists to explore important factors for attracting more tourists by using appropriate photo-sharing channels to effectively reach future tourists.

Table 9. Subsidiary hypothesis testing

8. Conclusion

It must be said that with the emergence of digital technology and smartphones and concomitant improvement in the quality of accessible cameras and photography, photo dissemination has become an integral part of tourism. It is well understood that tourists capture images with various motivations. In postmodern tourism, the walls and borders have collapsed and pictures are observable from all over the world thanks to “hashtags”. Tourists write exaggerated captions on their photographs, inviting other tourists from across the globe. The pervasive power of photography in the travel industry is to the extent that tourists, even in these times of pandemic and lockdowns, review and disseminate memories of their past travels by sharing their old photographs in cyberspace, somehow conveying their desire to revisit a location. Shiraz metropolis as the largest city in southern Iran and one of the most beautiful cities in the Middle East hosts many tourists from all over the world every year. Furthermore, Shiraz is currently the center of medical tourism in the field of cosmetic surgery, such as dental tourism and hair transplant tourism, in the region; thus, tourism officials of Shiraz metropolis should pay more attention to related content shared in cyberspace because much inbound and outbound tourists travel to this beautiful destination using the Shiraz hashtags. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), in line with its advice to tourists at the time of the Covid−19 outbreak, recommended that in the current situation, pictures are the bridge of communication between tourists with tourism and travel and emphasized that tourists’ photos in cyberspace can help the psychological management of tourists during the quarantine period. Therefore, the role of photos shared by tourists in cyberspace in preserving the relationship between society and the tourism industry and reducing psychological effects in the current situation during the quarantine period can be a good subject for future research. Moreover, the research constitutes an indicative contribution to tourism literature and suggests important implications for DMOs in the context of destination marketing and empowers them to investigate significant factors for attracting more tourists by utilizing proper photo-sharing channels to reach prospective tourists effectively. In addition, further investigations can be done on supportive UGC or TGC elements such as narrative captions, reviews, comments, etc., for gaining a deeper perception of the behavioral preferences of tourists. Above these, the current study gives insight to tourism scholars to survey the specific emotional behavior of tourists while opting for their destinations. In the end, local distinctiveness is a changeable feature. This study illuminates marketers with an idea to modify the destination’s characteristics and uniqueness creatively according to consumers’ needs and pleasures. In this regard, the type of services that travelers care about more can be considered as distinctive features of a destination. Just like most exploratory surveys, some limitations can be pointed out to address future studies. First, the current study was done in the time of Covid − 19 outbreak, so there are some limitations with the homogeneity of the research population as the sample consisted of tourists who traveled to Shiraz, and with no doubt, many regular travelers from so many areas of the world are missing during this time period. Second, as this study sample is selected with no consideration of gender, age, educational level, nationality, etc., future research can consider such socio-demographic factors to obtain more precise results and conclusions. Third, the study has only investigated one format of UGC (i.e., photograph) namely TGC, so future studies can evaluate a multitude of factors together or comparatively, especially comments and reviews supporting an online image shared in social media. Finally, as the authors’ observations were based on five social media channels, future research can bring sincerer indications by investigating more online media channels such as Instagram, Whats App, Telegram and etc.

9. Research limitations and future research suggestions

The re-emergence of the pandemic in Iran coincided with the conduct of the research and created restrictions from the point of view of visiting hotels and interviewing tourists, and for this reason, many tourists did not want to interview researchers. Also, some hotels had imposed restrictions on the visit of non-residents to the hotel according to the conditions of the epidemic. In accordance with these conditions, one of the positive axes for future research can be to investigate the importance of non-advertising images published in the virtual space in marketing and introducing the destination. Also, the role of these images and content produced by tourists from the destination on the re-choice of the destination by tourists is also a practical suggestion. This issue is also important for the beneficiaries and destination planners because it can greatly affect their marketing activities. In this context, issues such as the homogenization of destination marketing activities with the content shared in online media can be a good suggestion for destination studies. Because tourists usually compare the content of marketing activities with tourists’ feedback before choosing a destination and one of the most important of this feedback is shared images.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amir Ghorbani

Hossein Mousazadeh, is a researcher in Community development and Tourism Management at Eötvös Loránd University. His research interests included Community development, Tourism Management and Quality of Life studies.

Amir Ghorbani is a Postdoc fellowship researcher in Tourism Management at the University of Isfahan. He is an editorial board member in the International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews and also a reviewer in tourism journals.

Azadeh Golafshan is a Lecturer in the Department of Television & Digital Arts at Shiraz University of Arts in Shiraz. She has a master’s degree in Communication & Journalism from Osmania University, Hyderabad, India.

Farahnaz Akbarzadeh Almani currently is a senior researcher in Budapest Business School-University of Applied Sciences in the field of Tourism Management. She is an Tourism enventor and senior researcher in Tourism management.

Lóránt Dénes Dávid is professor at Institute of Rural Development and Sustainable Economy, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He is an awardee of the Jean Monnet Professorship (EU Commission).

Hossein Mousazadeh

Hossein Mousazadeh, is a researcher in Community development and Tourism Management at Eötvös Loránd University. His research interests included Community development, Tourism Management and Quality of Life studies.

Azadeh Golafshan

Azadeh Golafshan is a Lecturer in the Department of Television & Digital Arts at Shiraz University of Arts in Shiraz. She has a master’s degree in Communication & Journalism from Osmania University, Hyderabad, India.

Farahnaz Akbarzadeh Almani

Farahnaz Akbarzadeh Almani currently is a senior researcher in Budapest Business School-University of Applied Sciences in the field of Tourism Management. She is an Tourism enventor and senior researcher in Tourism management.

Lóránt Dénes Dávid

Hossein Mousazadeh, is a researcher in Community development and Tourism Management at Eötvös Loránd University. His research interests included Community development, Tourism Management and Quality of Life studies.

References

- Akgün, A. E., Senturk, H. A., Keskin, H., & Onal, I. (2020). The relationships among nostalgic emotion, destination images and tourist behaviors: An empirical study of Istanbul. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.03.009

- Balomenou, N., & Garrod, B. (2019). Photographs in tourism research: Prejudice, power, performance and participant-generated images. Tourism Management, 70, 201–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.08.014

- Batat, W., & Prentovic, S. (2014). Communicating responsible behaviour in tourism through online videos: A cross-cultural perspective. ACR North American Advances. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v42/acr_v42_17136.pdf

- Browne, E. G. (1893). A year amongst the Persians: impressions as to the life, character, & thought of the people of Persia, received during twelve months’ residence in that country in the years 1887-1888. A and C Black. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GM0oAAAAYAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=A+Year+Amongst+the+Persians&ots=ruFE6W7D5K&sig=1lQlkEGYQCN5S-1SWR5lPuBgJz4#v=onepage&q=A%20Year%20Amongst%20the%20Persians&f=false

- Bull, S. (Ed.). (2020). A companion to photography. John Wiley & Sons. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QFTGDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=Bull,+S.+2020.+A+Companion+to+Photography.+John+Wiley+%26+Sons%E2%80%8F.+Ed.&ots=AHSEkCG4zK&sig=WQu-LsbbCg30PHUhWGw9_vXR7GI#v=onepage&q=Bull%2C%20S.%202020.%20A%20Companion%20to%20Photography.%20John%20Wiley%20%26%20Sons%E2%80%8F.%20Ed.&f=false

- Chilembwe, J. M., & Gondwe, F. W. (2020). Role of social media in travel planning and tourism destination decision making. In Handbook of research on social media applications for the tourism and hospitality sector (pp. 36–51). IGI Global. https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/role-of-social-media-in-travel-planning-and-tourism-destination-decision-making/246369

- Conti, E., & Lexhagen, M. (2020). Instagramming nature-based tourism experiences: A netnographic study of online photography and value creation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 100650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100650

- Ernawadi, Y., & Putra, H. T. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of memorable tourism experience. Dinasti International Journal of Management Science, 1(5), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.31933/dijms.v1i5.280

- Faraji, A., Khodadadi, M., Nematpour, M., Abidizadegan, S., & Yazdani, H. R. (2021). Investigating the positive role of urban tourism in creating sustainable revenue opportunities in the municipalities of large-scale cities: The case of Iran. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(1), 177–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2020-0076

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Gearhart, M. C. (2022). A psychometric evaluation of the mutual efficacy scale: Factor structure, convergent, and divergent validity. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 49(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.15453/0191-5096.4547

- George, B. (2020). Inclusive sustainable development in the Caribbean region: Social capital and the creation of competitive advantage in tourism networks. https://essuir.sumdu.edu.ua/handle/123456789/80730

- Gholami, M., Keshtvarz Hesam Abadi, A. M., Miladi, S., & Gholami, M. (2020). A systematic review of the factors affecting the growth of medical tourism in Iran. International Journal of Travel Medicine and Global Health, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijtmgh.2020.01

- Ghorbani, A., Danaei, A., Barzegar, S. M., & Hemmatian, H. (2019). Post modernism and designing smart tourism organization (STO) for tourism management. Journal of Tourism Planning and Development, 8(28), 50–69. https://tourismpd.journals.umz.ac.ir/m/article_2268.html?lang=en

- Ghorbani, A., Mousazadeh, H., Akbarzadeh Almani, F., Lajevardi, M., Hamidizadeh, M. R., Orouei, M., Zhu, K., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). Reconceptualizing customer perceived value in hotel management in turbulent times: A case study of Isfahan metropolis five-star hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(8), 7022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15087022

- Ghorbani, A., Mousazadeh, H., Taheri, F., Ehteshammajd, S., Azadi, H., Yazdanpanah, M., Khajehshahkohi, A., Tanaskovik, V., & Van Passel, S. (2021). An attempt to develop ecotourism in an unknown area: The case of Nehbandan County, South Khorasan Province, Iran. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(8), 11792–11817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01142-w

- Ghorbani, A., Raufirad, V., Rafiaani, P., & Azadi, H. (2015). Ecotourism sustainable development strategies using SWOT and QSPM model: A case study of Kaji Namakzar Wetland, South Khorasan Province, Iran. Tourism Management Perspectives, 16, 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.09.005

- Gravari-Barbas, M., Graburn, N., Gravari-Barbas, M., & Graburn, N. (2016). Tourism imaginaries at the disciplinary crossroads. Routledge. https://routledge.com/Tourism-Imaginaries-at-the-Disciplinary-Crossroads-Place-Practice-Media/Gravari-Barbas-Graburn/p/book/9781032242446

- Hahm, J., Tasci, A. D., & Terry, D. B. (2018). Investigating the interplay among the Olympic Games image, destination image, and country image for four previous hosts. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(6), 755–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1421116

- Höckert, E., Lüthje, M., Ilola, H., & Stewart, E. (2018). Gazes and faces in tourist photography. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.09.007

- Ho, C. I., Lee, P. C., Brendan, T., & Dr, C. (2015). Are blogs still effective to maintain customer relationships? An empirical study on the travel industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 6(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-01-2015-0005

- Hong, S. J., Choi, D., & Chae, J. (2020). Exploring different airport users’ service quality satisfaction between service providers and air travelers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101917

- Jenkins, O. (2003). Photography and travel brochures: The circle of representation. Tourism Geographies, 5(3), 305–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680309715

- Kimmel, A. J., & Kitchen, P. J. (2014). WOM and social media: Presaging future directions for research and practice. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(1–2), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2013.797730

- Liang, R., & Luo, S. (2019). Research on image perception of Guilin tourism destination based on network text analysis. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 118, p. 03019). EDP Sciences.https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs/2019/44/e3sconf_icaeer18_03019/e3sconf_icaeer18_03019.html

- Li, M., Tucker, H., & Chen, G. (2022). Chineseness and behavioural complexity: Rethinking Chinese tourist gaze studies. Tourism Review, 77(3), 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2021-0088

- Luo, L., Zhang, L., Zheng, X., & Wu, G. (2022). A hybrid approach for investigating impacts of leadership dynamics on project performance. Engineering, Construction & Architectural Management, 29(5), 1965–1990. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-02-2020-0094

- Mak, A. H. (2017). Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tourism Management, 60, 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.012

- Morabi Jouybari, H., Ghorbani, A., Mousazadeh, H., Golafshan, A., Akbarzadeh Almani, F., Dénes, D. L., & Krisztián, R. (2023). Smartphones as a platform for tourism management dynamics during pandemics: A case study of the shiraz metropolis, Iran. Sustainability, 15(5), 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054051

- Mousazadeh, H., Ghorbani, A., Azadi, H., Almani, F. A., Mosazadeh, H., Zhu, K., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). Sense of place attitudes on quality of life during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The case of Iranian residents in Hungary. Sustainability, 15(8), 6608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086608

- Mousazadeh, H., Ghorbani, A., Azadi, H., Almani, F. A., Zangiabadi, A., Zhu, K., & Dávid, L. D. (2023). Developing sustainable behaviors for underground heritage tourism management: The case of Persian Qanats, a UNESCO world heritage property. Land, 12(4), 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040808

- Nechita, F., Demeter, R., Briciu, V. A., Varelas, S., & Kavoura, A. (2019). Projected destination images versus visitor-generated visual content in Brasov, Transylvania. In Strategic innovative marketing and tourism: 7th ICSIMAT, Athenian Riviera, Greece, 2018 (pp. 613–622). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12453-3_70

- Nikjoo, A., & Bakhshi, H. (2019). The presence of tourists and residents in shared travel photos. Tourism Management, 70, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.08.005

- Özdemir, M. A., & Yildiz, L. D. S. (2020). How Covid-19 outbreak affects tourists’ travel intentions? A case study in Turkey. Social Mentality and Researcher Thinkers Journal, 6(32), 1101–1113. https://doi.org/10.31576/smryj.562

- Pan, X., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2021). Investigating tourist destination choice: Effect of destination image from social network members. Tourism Management, 83, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104217

- Perpiña, L., Camprubí, R., & Prats, L. (2019). Destination image versus risk perception. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348017704497

- Prideaux, B., Lee, L. Y. S., & Tsang, N. (2018). A comparison of photo-taking and online-sharing behaviors of mainland Chinese and Western theme park visitors based on generation membership. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766716682554

- Puspita, E. (2020). Designing and developing an integrative application based on cross-functional & virtual team as a COVID-19 case management. Available at SSRN 3591007. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3591007

- Qin, D., Xu, H., & Chung, Y. (2019). Perceived impacts of the poverty alleviation tourism policy on the poor in China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 41, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.09.004

- Rezaei, S., Shahijan, M. K., Valaei, N., Rahimi, R., & Ismail, W. K. W. (2018). Experienced international business traveller’s behaviour in Iran: A partial least squares path modelling analysis. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 18(2), 163–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358416636930

- Santos, M. L. B. D. (2022). The “so-called” UGC: An updated definition of user-generated content in the age of social media. Online Information Review, 46(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-06-2020-0258

- Shaykh-Baygloo, R. (2021). Foreign tourists’ experience: The tri-partite relationships among sense of place toward destination city, tourism attractions and tourists’ overall satisfaction-evidence from shiraz, iran. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100518

- Singh, S., & Srivastava, P. (2019). Social media for outbound leisure travel: A framework based on technology acceptance model (TAM). Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2018-0058

- Sparks, B. A., Perkins, H. E., & Buckley, R. (2013). Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tourism Management, 39, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.03.007

- Suharyanto, A., Barus, R. K. I., & Batubara, B. M. (2020). Photography and tourism potential of Denai Kuala Village. Britain International of Humanities and Social Sciences (BIoHs) Journal, 2(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.33258/biohs.v2i1.153

- Sun, M., Ryan, C., & Pan, S. (2015). Using Chinese travel blogs to examine perceived destination image: The case of New Zealand. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522882

- Tan, W. K., & Wu, C. E. (2016). An investigation of the relationships among destination familiarity, destination image and future visit intention. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.008

- Taylor, D. G. (2020). Putting the “self” in selfies: How narcissism, envy and self-promotion motivate sharing of travel photos through social media. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2020.1711847

- Terttunen, A. (2017). The influence of Instagram on consumers’ travel planning and destination choice. Master’s Thesis Degree Programme in 2017. https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/129932

- Timoshenko, A., & Hauser, J. R. (2019). Identifying customer needs from user-generated content. Marketing Science, 38(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2018.1123

- Ukpabi, D. C., & Karjaluoto, H. (2017). Consumers’ acceptance of information and communications technology in tourism: A review. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 618–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.12.002

- Wang, J., Li, Y., Wu, B., & Wang, Y. (2021). Tourism destination image based on tourism user generated content on internet. Tourism Review, 76(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2019-0132

- Xia, M., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, C. (2018). A TAM-based approach to explore the effect of online experience on destination image: A smartphone user’s perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.05.002

- Yang, F. X. (2017). Effects of restaurant satisfaction and knowledge sharing motivation on eWOM intentions: The moderating role of technology acceptance factors. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 41(1), 93–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013515918

- Yang, L., Chu, X., Gou, Z., Yang, H., Lu, Y., & Huang, W. (2020). Accessibility and proximity effects of bus rapid transit on housing prices: Heterogeneity across price quantiles and space. Journal of Transport Geography, 88, 102850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102850

- Zhu, D. H., Chang, Y. P., & Luo, J. J. (2016). Understanding the influence of C2C communication on purchase decision in online communities from a perspective of information adoption model. Telematics and Informatics, 33(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.06.001