?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic raised the need for an increase in public services to counter the negative economic ramifications of the pandemic. However, this meteoric emergence of coronavirus inadvertently gave birth to inefficiencies entrenched in the delivery of government interventions to contain the disease and its economic effects. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the efficiency in delivery of government services and interventions aimed at ameliorating the COVID-19 pandemic. This study uses descriptive statistics and ordinal regression analysis to identify the drivers of inefficiency perceptions among recipients of social security interventions during the pandemic. Survey data for a sample of 855 participants was drawn from King Cetshwayo District municipality in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. The key findings revealed that the delivery of most government interventions in South Africa was perceived as not well coordinated and poorly communicated, hence inefficient. Drivers of these perceptions included age, income level, race, and employment status. In addition, whether or not an individual had received some form of social security assistance during the pandemic also influenced their perceptions about government efficiency in providing social security support. We recommend strengthening monitoring and evaluation mechanisms across government service delivery initiatives and improving communication of government programs to improve user experience and access.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper is an attempt at reviewing the extent to which government programmes that were aimed at reducing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic were efficiently delivered. Anecdotal evidence reveals high levels of discontent among recipients of the services and the general public as cases of corruption and maladministration surfaced in the media. Misallocation and misuse of resources threatens the success of any programme and erodes public trust on public sector programmes. Our findings show that a high proportion of recipients of social security interventions in South Africa perceived the government as being inefficient in its delivery of these programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic period. We also show that some of the drivers of these perceptions include the age of the recipients and the type of social security service received.

1. Introduction

Although different countries around the globe developed intervention programs to counter the impact of COVID-19 crisis, the services were heterogeneous in nature and used various delivery channels (Anguera-Torrell et al., Citation2021; Martínez-Córdoba et al., Citation2021). The government of South Africa implemented several programs to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic (Mushayabasa et al., Citation2020). However, there have been public reports of inefficiencies and ineffectiveness in the methods used to distribute the available resources. Among others, Transparency International (Citation2020) bemoans increased corruption and misallocation of resources meant for assisting those affected by the pandemic in South Africa. Despite these reported inefficiencies in the delivery of government interventions aligned to the reduction of the impact of COVID-19 crisis, resulting largely from gross mismanagement and malpractices, there has been no formal inquiry into the delivery of these services.

Fewer studies have investigated efficiency in delivery of health programs (Martínez-Córdoba et al., Citation2021; Olanubi & Olanubi, Citation2022), electronic systems used during the pandemic (Hodzic et al., Citation2021) and support to businesses (Lalinsky & Pál, Citation2021). Martínez-Córdoba et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study on efficiency in the governance of the COVID-19 pandemic in 237 countries. However, the study was based on desktop research and could not specifically address the efficiency of government programs in South Africa. Similarly, Mamokhere et al. (Citation2021) carried out a study on the implementation of the basic values and principles governing public administration and service delivery in South Africa. However, their study was centred on reviewing the values and principles of public administration as applied to municipality service delivery programs and did not focus on evaluating COVID-19 interventions. Globally, Delis et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study on the efficiency of government policy during the COVID-19 pandemic in 81 countries using data envelope analysis and secondary data on policy interventions and deaths experienced during the pandemic. Their findings, which we corroborate, reflect low efficiency scores for South Africa. Our contribution stems from using primary data and users’ perceptions to evaluate the efficiency of the government’s delivery of services to ameliorate the COVID-19 pandemic. Our approach, which is widely acknowledged in the literature, has the advantage of capturing user experiences (Menezes et al., Citation2022; Rocheleau, Citation1986).

This paper distinguishes itself from its predecessors by focusing primarily on interventions of a social security nature, which were aimed at cushioning households against the negative repercussions of the pandemic. We acknowledge the heterogeneous effect of the coronavirus across different countries, which prompted different responses by governments (Gursoy & Chi, Citation2020; Oni & Omonona, Citation2020). Furthermore, responses to the crisis differed in depth and scale, depending on economy size and capacity, with developed and emerging economies using more resources compared to developing economies (Lacey et al., Citation2021; Lalinsky & Pál, Citation2021). However, these interventions have been marred with controversy and inefficiencies, which may have led to the erosion of public trust in government (Odeku, Citation2021; Transparency International, Citation2020). Not only that, the wave of misinformation and controversies from government experts embedded in the services has also heightened mistrust from the public. In response to this, the government of South Africa (Sa, Citation2020) established a collaborative and coordinating centre aimed at improving the efficiency in distribution of COVID-19 related support. However, no formal inquiry exists that seeks to establish whether these efforts were successful.

On the backdrop of scarce resources that South Africa has, it is critical to examine how efficient government was in delivering the interventions targeted at reducing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic, and the major determinants of inefficiency. This study is necessitated by the lack of empirical studies that analyse drivers of such inefficiency. In the long run, the efficiency of the government interventions may increase social and economic resilience to future crises. Considering that there are still some interventions which are being developed to recover successfully and fully from the pandemic, efforts at curbing the crisis need to be evaluated and recommendations implemented. In this paper, an evaluation of the efficiency of the government programs is conducted using perceptions of government social security recipients. We contribute to the literature on public sector efficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic through empirically analysing the drivers of inefficiency perceptions among recipients of targeted social security interventions in a largely rural district in South Africa.

The rest of the paper is as follows: section 2 reviews literature on public sector efficiency and the COVID-19 pandemic. Section 3 outlines the methodology used in the study. In section 4, the study presents and discusses the results from the analysed data. The paper concludes in section 5.

2. Literature review

Governments across the world scrambled with interventions in an effort to curb the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Banholzer et al., Citation2020). The unprecedented, rare event required emergency actions in the form of government interventions that could reduce its impact on the society and the economy. This section reviews the literature on the COVID-19 crisis, and the interventions from the government aimed at ameliorating the pandemic. Furthermore, we position this paper within the literature on public sector efficiency to link efficiency goals of the public sector to interventions made during the pandemic.

2.1. Theoretical framework

This paper was guided by X-efficiency theory. The theory was propounded by Leibenstein (Citation1966). X-efficiency theory relates to the extent to which efficiency is enforced by institutions under imperfect competition conditions (Frantz, Citation1988). The study by Silkman and Young (Citation1982) is one of the initial works to explore X-efficiency in the public sector delivery of social security support programmes. They question whether the outlays on public finances used by governments resulted in increased benefits to the targeted beneficiaries or not. According to Leibenstein (Citation1978), the organisation needs to obtain maximum outputs from injected inputs. In relation to this paper, the government institutions responsible for delivering the intervention programmes aimed at mitigating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic must ensure most citizens got access to goods and services, namely mask wearing, centralised quarantine, COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress Grant (temporary grant of R350=US$20), and unemployment relief. In contrast to neo-classical theories of efficiency, X-efficiency theory allows for irrational actions by the organisations in the market. In line with this paper, the irrational actions may include maladministration, negligence, lack of foresight, unwarranted red tape, untold delays, malpractices, and mismanagement of various relief programs. The theory further refutes the belief that organisations are rational as there is a difference between optimal efficiency and observed behaviour in practice. Other studies on public sector efficiency show that it is multifaceted due to the many goals that the government has (Hodzic et al., Citation2021; Manzoor, Citation2014). Thus, our main focus for evaluating efficiency will not be on the government system or a specific numerical output but on the experiences and perceptions of recipients of social security intervention recipients.

2.2. Delivery of government programs

The government interventions were much needed to curb the scourge of coronavirus. According to Akrofi and Antwi (Citation2020), the region of Southern African Development Community (SADC) required territorial approaches in the form of programs to counter the impact of COVID-19 crisis to fiscal fronts, social, economic, and health aspects. The impact of government interventions in response to COVID-19 crisis on provincial and local government finances is significant (Zhou et al., Citation2023). The programs deployed to contain the socio-economic crisis associated with COVID-19 has a profound detrimental impact on the finances of the government. This has a “scissors effect” which denotes the falling of revenue and a cumulative increase in expenditure (Ashraf, Citation2020). In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, the government of South Africa deployed two main government interventions, namely crisis management interventions and response-recovery interventions (Abdool-Karim, Citation2020). The crisis management intervention incorporates the crisis communication, governance, and whole-of-society responses, while response-recovery intervention includes lockdowns, restrictions, economic and financial support, health measures, and social policy. Abdoul-Azize and El-Gamil (Citation2021) define crisis management intervention as the government actions and policies executed to deal with the materialised catastrophe. Crisis management involves the appropriate response, at the right place and time by the government (Hassankhani et al., Citation2021). Managing critical modern crises like the COVID-19 pandemic require numerous role players, not only emergency services. However, it is without governance challenges as the intervention rolled out by the government are exposed to inefficiencies. Although the interventions linked to COVID-19 were managed by the national government of South Africa, the actual exercise of duty to attain the expected outcomes of each intervention program is conducted at subnational levels such as provincial and local levels. These subnational levels need to maintain transparency in the allocation of resources and clear communication to the public, as crisis of large-scale nature like COVID-19 has a great impact on community’s trust in government.

The efficiency of interventions implemented for “whole-of-society response” co-ordination, in particular, i) engagements with relevant stakeholders in strategic processes of decision-making; and ii) co-operation mechanisms across various categories of government, have not been adequately evaluated. It is also crucial to evaluate the efficiency of decentralisation of government interventions to manage the substantial shocks emanated from COVID-19 pandemic. The provincial and local governments were tasked to spearhead some of the intervention but that resulted in the rise of corruption, bribery, theft, nepotism, and tribalism (Zhao et al., Citation2020). In accordance with crisis communication, the quality of communication regarding COVID-19 crisis is scrutinised and efficiency in terms of how government screened falsified information is checked. The South African government utilised numerous channels of communication supported by state-of-the-art information technologies to disseminate information about coronavirus (Kollamparambil et al., Citation2021). The information shared was largely covering social distancing measures, lockdown compliance, and other infection control measures. In some instances, Stiegler and Bouchard (Citation2020) state that the government collaborate with civil society organisations and local actors to disseminate information about the pandemic. Hence, the efficiency of crisis management intervention such as communication of the crisis, arrangements of governance implemented to monitor the crisis, and measures within the programs deployed for whole-of-society response co-ordination, are evaluated in this paper.

In terms of response-recovery interventions and services, these are actions and policies carried out by the government in quest of reducing the impacts of the pandemic, as well as economic crisis on the general public and businesses (Phiri, Citation2021). These actions reduce welfare loss and support economic recovery. The interventions incorporate health measures sought to protect and treat the people; social policies targeted at containing the disease against vulnerable people; financial and economic support to the community, markets, and business to reduce the impact of economic quagmire; the restrictions and lockdown measures undertaken to lower the spread of the virus (Al-Saidi et al., Citation2020; Le-Grange, Citation2021; Nyabadza et al., Citation2020). Hence, the key response-recovery programs are income support package, health response and containment, and social distancing. The social distance policy includes the closure of public transport, parks, workplaces, and schools, among others. Meanwhile income package support incorporates financial assistance from government to the households which can be in the form of utilities payments, debt relief, and direct cash transfers (Hunt et al., Citation2021). The government proposed a temporary grant of R350 for coronavirus relief and a child support grant top-up for 6 months. Although the unemployment relief is extended to informal workers, it was difficult to access. Furthermore, in spite of government attempts to provide these rescue funds, it was still not adequate to cater for most of the population, particularly those who depend on informal sector income only. In terms of health response and containment interventions, the following are incorporated namely medical cooperation, testing and vaccination, classification of city epidemic risk level, patient quarantine, and close contact tracing (Hatefi et al., Citation2020). However, uncertainties were generated with respect to the efficiency of these government programs.

2.3. Efficiency and delivery of government programs

We do not find specific literature evaluating the efficiency of government services in South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, several studies have analysed public sector efficiency in South Africa (Mafunisa, Citation2004; Monkam, Citation2014; Ngobeni et al., Citation2020; Zere et al., Citation2001) and other countries (Olanubi & Olanubi, Citation2022). Menezes et al. (Citation2022) and Rocheleau (Citation1986) also review approaches to evaluation of public services using perceptions of users. Thus, our study can be positioned within the literature on evaluation of government services by users or recipients of such services. Mafunisa (Citation2004) and Ngobeni et al. (Citation2020) show that public service of South Africa is marred by poor responsiveness towards complaints from citizens, discourteous officials, poor consultation, and openness about the expected service standards and poor access to services. Increased service delivery can be realised through the efficiency of different government levels and public institutions. Through practicing efficiency, there can be a transition from having a negative perception to positive perceptions (Ngobeni et al., Citation2020). Unlike the private sector, where efficiency can be measured by material profit, the public sector just looks at general utility. While most aspects of the private sector can be measured, the public sector utilises immeasurable objectives. For efficiency to be advanced, favourable institutional climate which supports delivery of programs should be provided (Lalinsky & Pál, Citation2021). It should provide and foster an environment of impartiality and fairness. The community needs should be responded to without unnecessary wastage of resources. In the public service, it is not sufficient just to provide services but the price and time in which those goods and services must be considered. The services should be delivered and met with minimum resources. The programs provided to the community should be efficient. Efficiency in delivering programs implies the need to maximise the benefits while at the same time minimise the costs of generating or providing these benefits.

By investigating the efficiency of government interventions aimed at reducing the COVID-19 pandemic, the government can draw lessons in the preparation of rare, unknown, and sudden pandemic of similar nature in the future. Unnecessary wastage can be avoided at all costs to achieve optimal utilisation of scarce resources (Altmann et al., Citation2020). Due to the fact that the South African government implemented different combinations of interventions at different times in distinct orders, different resources that were injected brought different outcomes. The government mobilised resources to make the intervention programs succeed, which raises the question of how efficient these resources were used (Ranchhod & Daniels, Citation2021). Efficient use of resources could assist the government to cushion society against other catastrophes in the future. Therefore, disentangling the efficiency of each individual program is important.

While government interventions had an impact on reducing virus transmission, they had a distinct degree of cost to the economy and society. Government interventions such as complete lockdown put to a halt on most economic activities, therefore exposing the country to economic downfall and recession (Abdool-Karim, Citation2020). Some interventions such as wearing of masks were seen as cost-efficient due to easy implementation and low-cost of production (Hedding et al., Citation2020). However, even with these, infiltration of corruption became a key stumbling block to the efficient delivery of some COVID-19 crisis reduction interventions. This includes collusion in over-pricing the services, in some cases paid services are not rendered and nepotism was rife.

About US$29 billion (R500 billion) worthy of socio-economic intervention programs were developed and deployed to counteract the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic (South African Government, Citation2020). The government programs also constituted the relief package of R500 (US28) to cater for food parcels and temporary social grants which targeted less privileged people which amount to 16 million. The key social grant was called COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress grant and temporary employee or employer relief scheme. However, there was public anger regarding the manipulation of processes in which the food parcels were distributed (Aikins, Citation2022). There was an alleged abuse of the food parcel distribution where unscrupulous individuals comprising businesspeople, ward councillors, and politicians endeavoured to further their own interests through these programs. Despite the increased number of malpractices and mismanagement of various relief programs meant to cushion the impact of COVID-19 crisis, there has been a deafening silence from the government. Mlambo and Masuku (Citation2020) state that mismanagement of the relief programs has been associated with extreme lack of oversight, maladministration, unwarranted red tape, and untold delays. Although the few investigations have been undertaken, cases of corruption have been piling up at an alarming rate (Farzanegan & Hofmann, Citation2021). While there has been inordinate transparency and openness in the provision of updates pertaining to the statistics, there has been little evaluation of the manner in which the programs related COVID-19 were delivered. For instance, unethical inflated prices of government contracts to procure medical apparatus worth US$900 million was discovered.

The enforcement of social distancing program saved lives of many people while increasing the costs on the community due to the rapid slump of socio-economic activities. Hence, government interventions in particular travel restrictions and lockdowns have been implemented with a view of enforcing social distancing and such interventions were hardly efficient due to the hastiness in which they were executed. Stringent measures of social distancing in the form of hard lockdown lowered the chances of people getting infected, therefore they were effective in reducing new infections (Hussain, Citation2020). However, the manner in which people complied with orders of stay-at-home differs with their level of income. Low-income groups were inclined to ignore and breach the stay-at-home orders as they prioritised finding ways to get food for survival, as a result they were more susceptible to the virus infections. However, later, the deployment of generous income support programs to low-income earners motivated them to stay at home in compliance with lockdown restrictions. Although some interventions were seen as counterproductive, they had indirect economic benefits through lessening the COVID-19 pandemic impacts.

3. Material and method

This paper was a retrospective study in nature. The paper utilised the descriptive research design and in terms of philosophy, it is rooted in the positivist paradigm. Descriptive research design ensured that in-depth information and comprehensive findings are obtained in respect of the efficiency of the government interventions in mitigating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. This study employed a quantitative research approach to mathematically express and model the relationship between efficiency perceptions and delivery of government social security interventions. The study was conducted in the King Cetshwayo District municipality of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. The total population of households in the district at the time of the study was estimated to be 232 797 (Docgta, Citation2020). The sample size as determined by Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) formula is 385. However, due to availability of data, the researchers employed a larger sample size of 855 participants drawn from a total of 1500 questionnaires that were distributed, which gives a response rate of 57%. The reason for collecting a larger sample was that the study was of an evaluative nature and getting more responses was expected to assist in local government decision-making. However, as stated in Lin et al. (Citation2013) and Khalilzadeh and Tasci (Citation2017) using larger data sets requires caution as it can exaggerate statistical significance. To address this challenge, we follow suggestions by Faber and Fonseca (Citation2014) to estimate the same model with smaller random sample and compare the results. The results of this robustness test are provided in the Appendix A and they confirm the main results reported in the paper. Furthermore, we report on odds ratios to address the problem that arise with the effect size in large samples (Khalilzadeh & Tasci, Citation2017).

A self-administered questionnaire was utilised to gather primary data. The questionnaire was comprised of closed-ended questions because they are quick and easy to answer. The study used personal method in collecting data in which the questionnaires were physically and face-to-face distributed. It was chosen because it is associated with high response rate and was suitable among most rural households who do not have strong and consistent internet connectivities. The usable responses were 855. However, due to gaps in the data in one of the variables, the second and 3rd models estimated used 689 observations. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse the data. Variables considered in the study are given in Table . We use questions that inquired perceptions of respondents on government’s efficiency in providing social security interventions to ameliorate the pandemic to create our government's inefficiency variable ().

Table 1. Description of the study variables

Table 2. Cronbach's alpha

Table 3. Government’s management of the pandemic – pandemic was well managed

To analyse the drivers of efficiency or inefficiency of government social security interventions during the pandemic, we employ Ordinal regression technique. This technique is suitable given the nature of the dependent variable, government efficiency (Y in the equation below), which is categorical in nature. Therefore, our choice of analytic approach was driven largely by the nature of data. Specifically, the paper uses the proportional odds model (POM). Equations (1) and (2) show the cumulative probability of obtaining outcome Y given independent variables

Where is the cumulative probability of event

occurring given the set of explanatory variables

, which includes demographic factors, government social security interventions, and location. The

represents a vector of constants and

represents a vector of coefficients. To test for proportionality of odds, the Approximate Likelihood-Ratio Test (chi-squared) by Wolfe and Gould (Citation1998) is used whose null hypothesis is that proportional odds assumption holds. That is, we can estimate a single equation across all response categories. We also present results for other tests. In terms of ethical consideration, confidentiality was ensured by leaving out any identity identifiers such as name, identity number, and date of birth from the questionnaire and guaranteeing participants that the public had no access to the answered questionnaires. An institutionalFootnote1 ethics clearance certificate was applied for and granted, and permission was sought from district officials to undertake the research.

4. Results and discussion

As alluded to in the previous section, we employed a combination of graphical frequency analysis and cross tabulation with non-parametric tests to gauge the efficiency of government in delivering programmes aimed at reducing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. Our analysis was particularly guided by the responses to questions related to government management of the pandemic and the overall satisfaction of the participants with the way the COVID-19 grants were administered. This was then followed by an ordinal regression analysis of the determinants of consumer perceptions on government efficiency in provision of social security support interventions during the pandemic. We use the four questions on efficient provision of government interventions to create a factor variable that captures government efficiency. In the first step, we test for reliability of the scales used in the instrument by using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The results are shown in Table .

4.1. Descriptive statistics

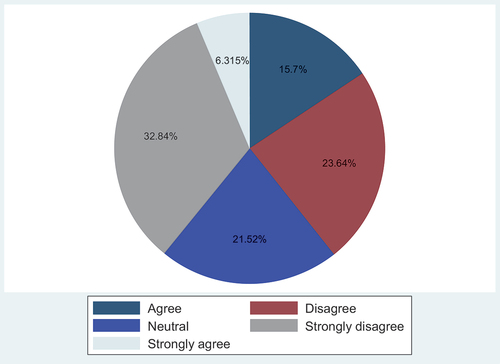

The entry point is a graphical display of responses to the proposition of government managing the pandemic well. Strikingly, as shown in Figure , 23 percent and 32 percent disagreed and strongly disagreed, respectively, to this claim. In other words, a combined 55 percent of the participants were not impressed by the way the government managed the COVID-19 pandemic. A possible explanation for this response may relate to the social dismay in general over the multiple corruption reports and allegations that surfaced during the early to mid-stages of the relief programs’ implementation. Corruption Watch, an organization that monitors the extent of corruption across countries, for example, alleges that less than half of those (households and businesses) eligible for relief grants did not receive them.

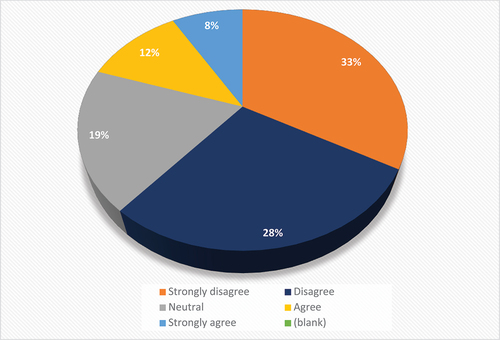

The next question was more specific, and it sought to inquire the perception of the participants on how well and efficient the government was in managing the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Social relief programs were primarily meant to shield and cushion households from the economic effects of the pandemic as the lockdown measures affected the income streams of households, particularly those that were heavily reliant on the informal sector. The efficiency of government in managing the pandemic from the economic consequences was therefore essentially gauged by how well participants perceived the government’s ability to meet these goals based on their experiences. As Figure displays, a combined 61 percent of the participants did not believe that the government managed the economic consequences of the pandemic well. Interestingly, for this less impressed group, a greater proportion of them (33 percent) were in the “strongly disagree” category. This is revealing insofar as it demonstrates a high degree of discontent among the research respondents regarding the government's ability to manage the economic consequences of the pandemic. Only 20 percent were affirmative in total, a figure that was barely above the proportion of neutral participants (19 percent).

The former result, however, needs to be interpreted with caution. On the one hand, it might be truly reflective of government’s inability to efficiently ameliorate the pandemic’s economic consequences. On the other hand, it may well be that government’s efforts were simply overwhelmed by the economic consequences which were difficult to anticipate during the early to mid-stages of the pandemic given the uncertainty that mulled the pandemic itself in terms of progression and a breakthrough in COVID-19 vaccine developments. Amid this high uncertainty as argued by Adegboye et al. (Citation2020), the pandemic eventually caused more than projected reduction in productivity, which consequently exerted a negative supply shock due to concomitant disruptions in global supply chains towards the back end of 2020.

One can only expect a more pronounced effect for South Africa given the country’s pre-existing, high, and unwelcoming levels of unemployment, poverty, and income inequality. Viewed this way, government’s efforts may have simply been overwhelmed by the severity of the pandemic and these pre-existing conditions. Empirically, Arndt, Robinson, and Gabriel (Citation2020) particularly found the economic impacts of the pandemic larger than anticipated in Africa for low-income and food-insecure households as the country’s lockdown policies were relatively more stringent. This study was carried out in locations that primarily comprise middle- to low-income households.

One important result gleaned from a recent study by Martínez-Córdoba et al. (Citation2021) is that geographical location matters when analysing the government’s level of efficiency in managing the pandemic. Against this backdrop, we proceeded to non-parametrically cross tabulate the responses related to government management of the pandemic and the geographical location from which the responses were sought. For those who were less impressed by government management looking at Table , much of the discontent was more observed in less economically developed areas such as Esikhawini followed by Melmoth and Eshowe (except Dlangezwa) as compared to urban places such as Richards Bay and Empangeni. This observation provides mild confirmatory support to a claim raised in Martínez-Córdoba et al. (Citation2021) which is that government’s level of efficiency is generally low in underdeveloped areas due to weak coordination systems. This is further exacerbated by the fact that economically deprived areas were relatively more affected by the pandemic compared to less economically deprived areas as raised by the OECD (Citation2021). The government’s approach to the pandemic was largely national hence the result in Table suggests that a territorial approach to the pandemic as implemented in the US, for example, might have aided the efficiency of government in managing the pandemic particularly in remote areas such as Mbonambi, Nkandla, and Eshowe. The probability value of the chi-square test is highly significant indicating a strong statistical association between the participant’s perception on government’s management of the pandemic and the geographical location.

4.1.1. Regression results

In Tables , we present the results from ordinal regression analysis. Model 1 is the baseline model to which we add controls for government interventions and location in model 2 and model 3. The estimations are done using STATA 14 and the command “ologit” and “oparallel ic” for testing the proportional odds assumption. The dependent variable, which is categorical in nature, encapsulates the opinions of respondents on whether the government efficiently managed the pandemic and its economic challenges well or otherwise. As discussed in section 3, we estimate a model in which the opinions of respondents about government efficiency or inefficiency are determined by demographic factors, whether or not they have received government social support and location. We test for the proportional odds assumption using Wolfe & Gould’s method, and all p-values for the test are above the 5% level of significance. Other post-estimation statistics are provided in Tables .

Table 4. Ordinal regression coefficients – determinants of government inefficiency perceptions

Table 5. Ordinal regression odds-ratios - determinants of government inefficiency perceptions

Our results show that the age of the household head is an important determinant of their thinking about government efficiency. In all three models the coefficient of age takes positive signs. For instance, the coefficient of age in model 1 is 0.4022 which translates to an odds ratio of 1.49, which is significant at 1% level. The result implies that being older, increases the odds of the respondent concluding that government service during the pandemic was efficient. This result is important because it shows the differences in confidence and experiences between the young and the old. Older individuals believe the government was efficient, which could be explained by the type of service they received from the government.

There were no big discrepancies about the belief on government efficiency across racial lines. We used the African race group as the base group and our findings show that only Indian households were most likely to think that the government did well compared to the African group. The results for coloured and white races are not significant. A significant finding draws from whether the household head was employed or not. This variable was categorical with higher values indicating self-employed or unemployed. The base value was formal employment. The results show that compared to those who were formally employed, unemployed, and self-employed individuals were of the opinion that the government fared poorly in providing COVID-19 related services. This might indicate the reportedly poor administration of the SRD grant and unemployment insurance fund.

In model 1, we also find higher-income households to have lower trust in government efficiency. In Table the odds ratio for

is 0.88, which is less than 1. Thus, increasing household income reduces the odds of believing that the government handled the pandemic efficiently. However, level of education, size of the household, and number of meals taken do not have a significant impact on efficiency perceptions.

In the second and third regressions, we control for government support received and location, respectively. Model 2 confirms most of the results from model 1. Two questions were used to capture government interventions (social security support). The first asked which support the respondent had received from the government during the pandemic, whereas the second only asked whether the grants should be increased or otherwise (variable ). The latter shows a positive and significant coefficient 0f 0.657, which gives an odds ratio of 1.92. Thus, compared to the baseline model, respondents who thought grants should not be increased were most likely to perceive the government as being efficient. On the contrary, those who thought grants were not enough and should be increased would most likely perceive the government as being inefficient.

We consider four specific interventions used by the government, which include social relief of distress (SRD) grant, unemployment insurance fund (UIF), tax relief, and government guaranteed bank loan as the support received. Note that our baseline variable is those that have received normal social grants including child support grant, old age and disability grants. Therefore, our interpretation of the results compares perceptions driven by these four interventions compared to individuals receiving the normal social grants. For instance, receiving an SRD grant (COVID-19 grant) reduces the odds of one holding the perception that the government has been efficient in providing social security support during the pandemic compared to the baseline model. The odds ratios for model 2 and model 3 are 0.73 and 0.70, respectively, which are less than 1. This result is strikingly important since it points to the inefficiencies, corruption, inaccessibility, and lack of information that characterised the distribution of the COVID-19 grants.

The coefficients for UIF are positive and significant in both models. From Table , the odds ratios for model 4 and model 5 are 2.54 and 2.37, respectively, and are both significant at 5% level. Compared to the base model, receiving UIF increases the odds of an individual perceiving the government as being efficient in providing social support during the pandemic.

Location variables cover the main areas under the King Cetshwayo district where the data was collected. The base location used in the study was Esikhaleni (Eskhawini) township, which is a rural township. Our coefficients are positive and significant for Nkandla, Melmoth, Mbonambi, Richards Bay, and Dlangezwa. The positive coefficient indicates odds ratios greater than 1 implying that compared to a person in Esikhaleni, being in any of these areas increases the odds of having positive perceptions about government social support during the pandemic. For instance, the odds ratio for Nkandla is 8.72 and is significant at 1% level. Thus, living in Nkandla increases the odds of rating government social security interventions as being efficient compared to living in Esikhaleni.

The only place in which perceptions were comparatively negative was Eshowe, which scored an odds ratio of 0.47. Therefore, being in Eshowe decreases the likelihood that the individual would rate the government as being efficient compared to being in Esikhaleni.

4.1.2. Robustness test results

As explained in the methodology section, we proceed to estimate the same models using a smaller sample to address challenges that may arise due to the use of a large sample. The results are provided in Appendix A. Largely, our results remain the same except for the SRD grant coefficient, which becomes statistically insignificant but takes the same sign. The model diagnostics support estimation of the ordinal regression models, with all tests of the proportional odds assumption failing to reject the null hypothesis of proportional odds. We therefore conclude that our model estimations are robust to changes in sample size and continue with a discussion of the results. The following covers the discussion section

5. Discussion

The results of this study reveal that majority of the people were not impressed by the way government managed the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study are consistent with research conducted by Mafunisa (Citation2004) on efficiency in local government in South Africa. The findings revealed that mismanagement and lack of responsiveness to public services needs to be dealt with to increase efficiency in local government. However, these findings are contrary to research conducted by Van der-Berg et al. (Citation2010) on the efficiency and equity effects of social grants in South Africa, which points to the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their study indicated that there is a well-developed social assistance system in South Africa, which strongly lowers poverty. The negative sentiments of participants on the government’s management of the pandemic are not unique to South Africa as they have been observed in many other countries across the African continent for various reasons. In Cameroon, for example, according to Aikins (Citation2022), widespread concerns on government’s management of the pandemic were reported on the back of a 2021 audit which shockingly revealed the misuse of about US$333 million (R5,8 billion) meant for the pandemic response in 2020. Similarly, in Malawi, Aikins (Citation2022) documents a disapproval by social relief beneficiaries following reports of government officials colluding with the private sector to redirect and misuse US$1.3 million (R22.5 million) worth of COVID-19 funds through procurement and allowance irregularities. The findings of this study are consistent with research conducted by Abdoul-Azize and El-Gamil (Citation2021) on social protection in managing crisis. The results show that there was lack of comprehensive strategy to respond to COVID-19 pandemic in various countries. The results are in line with research conducted by Monkam (Citation2014) on local municipality productive efficiency and its determinants in South Africa. The results indicate that the number and skill levels of the top management of a municipality’s administration and fiscal autonomy influenced the productive efficiency of municipalities.

The findings indicate that the bulk of the people did not believe that the government managed the economic consequences of the pandemic well. This is revealing insofar as it demonstrates a high degree of discontent among the research respondents regarding the government's ability to manage the economic consequences of the pandemic. The study results are consistent with research conducted by Boateng (Citation2014) on technical efficiency and primary education in South Africa. Their study found that lack of technical efficiency caused extensive delays and misappropriation of funds. A further confirmation comes from a study carried out by Zere, McIntyre and Addison (Citation2001) on health technical efficiency and productivity of public sector in South Africa using a desktop review. The study found that productivity losses in public organisations were jeopardising government efforts to redress past injustices. The result however needs to be interpreted with caution. On the one hand, it might be truly reflective of government’s inability to efficiently ameliorate the pandemic’s economic consequences. On the other hand, it may well be that government’s efforts were simply overwhelmed by the economic consequences which were difficult to anticipate during the early to mid-stages of the pandemic given the uncertainty that mulled the pandemic itself in terms of progression and a breakthrough in COVID-19 vaccine developments. Amid this high uncertainty as argued by Adegboye et al. (Citation2020), the pandemic eventually caused more than a projected reduction in productivity, which consequently exerted a negative supply shock due to concomitant disruptions in global supply chains towards the back end of 2020. The results are in line with research conducted by Warren and Gary (Citation2016) on efficiency evaluation of urban and rural municipal water service authorities in South Africa. The results of Warren and Gary (Citation2016)’s study indicated that South Africa experience both poor and excellent technical efficiencies.

The results from the ordinal regression models in this study may reveal inefficiencies, corruption, inaccessibility, and lack of information that characterised the distribution of the COVID-19 grants. These findings of this study are mirrored by research conducted by Farzanegan and Hofmann (Citation2021) on effect of public corruption on the COVID-19 immunisation progress of countries. The results reveal that due to high degree of corruption in certain countries the vaccination process was unsuccessful. In addition, the findings of this study show that majority of people who resided in urban areas have positive perceptions about government social support during the pandemic. The findings of this study are further consistent with research conducted by Kollamparambil et al. (Citation2021) on the behavioural response to the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. The study found that measures such as social distancing were practised more by the educated and rich and ignored more by the low-income earners. The results show that unemployed and self-employed individuals perceived that the government fared poorly in providing COVID-19 related services. Furthermore, the findings of this study indicate that bulk of people who resided in rural areas had positive perceptions about government social support during the pandemic compared to urban dwellers. The findings of the current study are also in line with research conducted by Odeku (Citation2021) on the socio-economic implications of COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. The findings revealed that the pandemic ravaged the poor more than the rich people.

6. Conclusion

The paper sought to investigate the efficiency in delivery of government services and interventions aimed at ameliorating the COVID-19 pandemic. The study adopted descriptive research design and quantitative research approach. Despite having scarce resources in South Africa, the study revealed that there were inefficiencies in the delivery of government interventions targeted at reducing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. This has been corroborated by disparate streams of results in this study, among them including government fell short in managing the COVID-19 pandemic; the economic consequences of the pandemic were not well-managed; and people were not impressed by the way government managed the COVID-19 pandemic. The empirical results from the study show that perceptions of government inefficiency or efficiency were driven by demographic factors such as age of the recipient, race, employment condition, and household income. Furthermore, receiving some form of social security relief also influenced respondents’ perceptions about government service delivery during the pandemic. In particular, receiving the social relief of distress (SRD) grant negatively influenced perceptions about government efficiency. However, those who received UIFs were more likely to rate government services as efficient. We also find disparities in perceptions across the different areas covered by the study. Since we established the level of government efficiency in delivering the interventions targeted at reducing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic, the primary objective of this study was achieved.

In terms of practical implications, the findings of the study indicated that using consumer perceptions to deliver government interventions to curtail the spread and impact of pandemic was inefficient. Hence, for local, provincial, and national governments to ensure efficient delivery of their programmes, focal practices of good governance which include transparency, accountability, fairness, and responsibility should be extensively enforced at all levels. These practices are geared towards efficiency in the delivery of social security programmes. Inefficiency in the delivery of government programmes is deleterious to the economy and society. Looking through the lens of the extant state of resources in South Africa, recognising the importance of efficiency in the delivery of government programmes is critical in these times of economic downturn. We recommend strengthening monitoring and evaluation mechanisms across government service delivery initiatives and improving communication of government programmes to improve user experience and access. Best governance practices can also be enforced, including clear linkages between the different spheres of government. In relation to theoretical implications, our paper broadens the literature on both social security programmes in times of crises and public sector efficiency. We provide empirical evidence on factors that drive inefficiency through identifying the determinants of inefficiency perceptions amongst recipients. However, like any study, this study also has limitations. The study was based in one province, KwaZulu-Natal, in South Africa. Hence, the generalisation of the results may not be extended to other eight provinces in South Africa due to different settings of the provinces. Therefore, future studies that incorporate other provinces may prove useful for generalisation and improvement of external validity of study’s results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

S. Zhou

Sheunesu Zhou is a senior Lecturer in the Department of Business Management at the University of Zululand. He has wider research interests in financial markets, macroeconomic policy formulation, development economics, and the application of econometric methods in economic policy analysis.

R. Utete

Reward Utete is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Business Management at the University of Zululand. He has research interests in governance issues, entrepreneurship, and industrial relations.

Notes

1. The study was conducted in accordance with the University of Zululand ethics policy and in line with prevailing national COVID-19 regulations in South Africa.

References

- Abdool-Karim, S. S. (2020). The South African response to the pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(24), 95. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2014960

- Abdoul-Azize, H. T., & El-Gamil, R. (2021). Social protection as a key tool in crisis management: Learnt lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Social Welfare, 8(1), 107–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-020-00190-4

- Aikins, E. R. (2022). Corruption in Africa deepens the wounds of COVID-19: The pandemic has been less deadly than elsewhere, but African economies have suffered a double blow due to graft. Retrieved May, 19 2022, from https://issafrica.org/iss-today/corruption-in-africa-deepens-the-wounds-of-covid-19

- Akrofi, M. M., & Antwi, S. H. (2020). COVID-19 energy sector responses in Africa: A review of preliminary government interventions. Energy Research & Social Science, 68(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101681

- Al-Saidi, A. M. O., Nur, F. A., Al-Mandhari, A. S., El Rabbat, M., Hafeez, A., & Abubakar, A. (2020). Decisive leadership is a necessity in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet, 396(10247), 295–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-67362031493-8

- Altmann, D. M., Douek, D. C., & Boyton, R. J. (2020). What policy makers need to know about COVID-19 protective immunity. Lancet, 395(1), 1527–1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30985-5

- Anguera-Torrell, O., Aznar-Alarcón, J. P., & Vives-Perez, J. (2021). COVID-19: Hotel industry response to the pandemic evolution and to the public sector economic measures. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1826225

- Arndt, C., Gabriel, S., & Robinson, S. (2020). Assessing the toll of COVID-19 lockdown measures on the South African economy. IFPRI Book Chapters, 31–32.

- Ashraf, B. N. (2020). Economic impact of government interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: International evidence from financial markets. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 27(1), 100371–100379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100371

- Banholzer, N., van Weenen, E., Kratzwald, B., Seeliger, A., Tschernutter, D., Bottrighi, P., Cenedese, A., Puig-Salles, J., Vach, W., & Feuerriegel, S. (2020). Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on documented cases of COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.16.20062141

- Boateng, N. A. (2014). Technical efficiency and primary education in South Africa: Evidence from sub-national level analyses. South African Journal of Education, 34(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412071117

- Delis, M. D., Iosifidi, M., & Tasiou, M. (2021). Efficiency of government policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. MPRA Paper No. 107292. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/107292/1/MPRA_paper_107292.pdf.

- Docgta. 2020. King Cetshwayo District: Profile and analysis of district development model. In: AFFAIRS, D. O. C. G. A. T. (ed.). Pretoria.

- Faber, J., & Fonseca, L. M. (2014). How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics, 19(4), 27–29. https://doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.027-029.ebo

- Farzanegan, M. R., & Hofmann, H. P. (2021). Effect of public corruption on the COVID-19 immunization progress. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02802-1

- Frantz, R. S. (1988). X-Efficiency: Theory, evidence and applications. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3799-7

- Gursoy, D. & Chi C. G. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 29(5), 527–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1788231

- Hassankhani, M., Alidadi, M., Sharifi, A., & Azhdari, A. (2021). Smart city and crisis management: Lessons for the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157736

- Hatefi, S., Smith, F., Abou-El-Hossein, K., & Alizargar, J. (2020). COVID-19 in South Africa: Lockdown strategy and its effects on public health and other contagious diseases. Public Health, 185(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.033

- Hedding, D. W., Greve, M., Breetzke, G. D., Nel, W., & Van Vuuren, B. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the academe in South Africa: Not business as usual. South African Journal of Science, 116(7–8), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2020/8298

- Hodzic, S., Ravselj, D., & Alibegovic, D. J. (2021). E-Government effectiveness and efficiency in EU-28 and COVID-19. Central European Public Administration Review, 19(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.17573/cepar.2021.1.07

- Hunt, X., Breet, E., Stein, D., & Tomlinson, M. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic, hunger, and depressed mood among South Africans. National Income Dynamics (NIDS)-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) Wave, 5, 6. https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/6

- Hussain, A. H. M. (2020). Belayeth, stringency in policy responses to Covid-19 pandemic and social distancing behavior in selected countries. SSRN Electronic Journal, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3586319 or. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3586319

- Khalilzadeh, J., & Tasci, A. D. (2017). Large sample size, significance level, and the effect size: Solutions to perils of using big data for academic research. Tourism Management, 62, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.026

- Kollamparambil, U., Oyenubi, A., & Goli, S. (2021). Behavioural response to the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa. Plos One, 16(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250269

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308

- Lacey, E., Massad, J., & Utz, R. (2021). A review of fiscal policy responses to COVID-19.

- Lalinsky, T., & Pál, R. (2021). Efficiency and effectiveness of the COVID-19 government support: Evidence from firm-level data. EIB Working Papers. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/234992

- Le-Grange, L. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and the prospects of education in South Africa. Prospects, 51(1), 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09514-w

- Leibenstein, H. (1966). Allocative efficiency vs. “X-Efficiency”. American Economic Association, 1(2), 392–415. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1823775#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Leibenstein, H. (1978). X-Inefficiency xists: Reply to an xorcist. American Economic Association, 1(3), 203–211. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1809700#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Lin, M., Lucas, H. C., Jr., & Shmueli, G. (2013). Research commentary—too big to fail: Large samples and the p-value problem. Information Systems Research, 24(4), 906–917. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2013.0480

- Mafunisa, M. (2004). Measuring efficiency and effectiveness in local government in South Africa. Journal of Public Administration, 39(2), 290–301. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC51326

- Mamokhere, J., Musitha, M. E., & Netshidzivhani, V. M. (2021). The implementation of the basic values and principles governing public administration and service delivery in South Africa. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(4), e2627. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2627

- Manzoor, A. (2014). A look at efficiency in public administration: Past and future. SAGE Open, 4(4), 2158244014564936. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014564936

- Martínez-Córdoba, P. J., Benito, B., & García-Sánchez, I. M. (2021). Efficiency in the governance of the Covid-19 pandemic: Political and territorial factors. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00759-4

- Menezes, V. G. D., Pedrosa, G. V., Silva, M. P. D., & Figueiredo, R. M. D. C. (2022). Evaluation of public services considering the expectations of users—A systematic literature review. Information, 13(4), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13040162

- Mlambo, V. H., & Masuku, M. M. (2020). Governance, corruption and COVID-19: The final nail in the coffin for South Africa’s dwindling public finances. Journal of Public Administration, 55(3–1), 549–565.

- Monkam, N. F. (2014). Local municipality productive efficiency and its determinants in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 31(2), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2013.875888

- Mushayabasa, S., Ngarakana-Gwasira, E. T., & Mushanyu, J. (2020). On the role of governmental action and individual reaction on COVID-19 dynamics in South Africa: A mathematical modelling study. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 20(1), 100387–100388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2020.100387

- Ngobeni, V., Breitenbach, M. C., & Aye, G. C. (2020). Technical efficiency of provincial public healthcare in South Africa. Cost Effectiveness & Resource Allocation, 18(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-020-0199-y

- Nyabadza, F., Chirove, F., Chukwu, C. W., & Visaya, M. V. (2020). Modelling the potential impact of social distancing on the COVID-19 epidemic in South Africa. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 20(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5379278

- Odeku, K. O. (2021). Socio-economic implications of COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 27(1), 1–6. https://www.proquest.com/openview/b62d402988183a667fb31f4df734ef61/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29726

- OECD. (2021). First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/first-lessons-from-government-evaluations-of-covid-19-responses-a-synthesis-483507d6/

- Olanubi, O. E., & Olanubi, S. O. (2022). Public sector efficiency in the design of a COVID fund for the euro area. Research in Economics, 76(3), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2022.07.004

- Oni, O., & Omonona, S. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 on small retail. The Retail and Marketing Review, 16(3), 48–57. https://retailandmarketingreview.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/RMR16_3_48-57.pdf

- Pak, A., Adegboye, O. A., Adekunle, A. I., Rahman, K. M., McBryde, E. S., & Eisen, D. P. (2020). Economic consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: The need for epidemic preparedness. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 241.

- Phiri, M. Z. (2021). South Africa’s Covid-19 responses: Unmaking the political economy of health inequalities. ORF Issue Brief, 445. https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ORF_IssueBrief_445_SouthAfrica-Covid.pdf

- Ranchhod, V., & Daniels, R. C. (2021). Labour market dynamics in South Africa at the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic. South African Journal of Economics, 89(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12283

- Rocheleau, B. (1986). Public perception of program effectiveness and worth: A review. Evaluation and Program Planning, 9(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-71898690005-4

- Sa, G. (2020). Fighting corruption during Covid-19 [online]. Pretori: Government of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/anti-corruption/fighting-corruption-during-covid-19 [ Accessed].

- Silkman, R., & Young, D. R. (1982). X-efficiency and state formula grants. National Tax Journal, 35(3), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1086/NTJ41862452

- South African Government. (2020). Social grants - Coronavirus COVID-19. https://www.gov.za/covid-19/individuals-and-households/social-grants-coronavirus-covid-19.

- Stiegler, N., & Bouchard, J. P. (2020). South Africa: Challenges and successes of the COVID-19 lockdown. Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique, 178(7), 695–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2020.05.006

- Transparency International. (2020). In South Africa, COVID-19 has exposed greed and spurred long-needed action against corruption. Voices for Transparency, September, 04. https://www.transparency.org/en/blog/in-south-africa-covid-19-has-exposed-greed-and-spurred-long-needed-action-against-corruption

- Van der-Berg, S., Siebrits, F. K., & Lekezwa, B. (2010). Efficiency and equity effects of social grants in South Africa. Bureau for Economic Research, 1, 1–58. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1727643

- Warren, B., & Gary, S. (2016). Efficiency evaluation of urban and rural municipal water service authorities in South Africa: A data envelopment analysis approach. Water SA, 42(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v42i1.02

- Wolfe, R., & Gould, W. (1998). An approximate likelihood-ratio test for ordinal response models. Stata Technical Bulletin, 7(42), 1–10.

- Zere, E., Mcintyre, D., & Addison, T. (2001). Technical efficiency and productivity of public sector hospitals in three South African provinces. South African Journal of Economics, 69(2), 336–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2001.tb00016.x

- Zhao, Z., Li, X., Liu, F., Zhu, G., Ma, C., & Wang, L. (2020). Prediction of the COVID-19 spread in African countries and implications for prevention and control: A case study in South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, Senegal and Kenya. The Science of the Total Environment, 729(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138959

- Zhou, S., Ayandibu, A. O., Chimucheka, T., & Masuku, M. M. (2023). Government social protection and households’ welfare during the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, Vol. ahead, Vol. aheadofprint No. ahead No. aheadofprint. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-04-2022-0044