Abstract

Popular tourist destinations face major governance challenges if their goal is to balance and reconcile the interests of different stakeholders, including companies, residents and tourists. Since Barcelona hosted the Olympic Games in 1992, the flow of tourists has not slowed down and, as a result, the number of accommodation places has grown steadily. Even the owners of residential properties have started offering their homes to visitors, a phenomenon that has led to a dramatic rise in the number of beds available for tourists in the city. The aim of this article was to analyse the way in which this accommodation category has grown with a view to reflecting on the most appropriate form of spatial distribution evenly throughout the city. The study used secondary data from Barcelona City Council’s records on tourist dwellings and data from Inside Airbnb on properties advertised through Airbnb. All processed data were used to create a weighted matrix based on objectives such as creating a fair economy or attracting everyday tourists. The research concludes with a new proposal of spatial distribution of tourist dwellings throughout the city based on the 15-minute city approach.

1. Introduction

Tourism is an economic, social, and cultural phenomenon that plays a role in urban transformation. Touristification is the process by which a city is turned into a monopolized, hyperspecialized setting by tourist activities and services (Lanfant, Citation1994). The expansion of hotels stemming from the acquisition of property by major investors, and, above all, the glut of tourist apartments is giving rise to a shift in residential patterns and changes in the value of housing (Cócola-Gant, Citation2018). These transformations as a consequence of its tourism consumption, have involved local governments to firstly create tourist resources and infrastructure (Colomb, Citation2012), and then, decide measures to limit the growth of tourism and to prevent the change of residential neighbourhoods into tourist areas. These local administration reactions to reshape the urban environment are present, for example, in the case of Barcelona and Berlin (Novy, Citation2013). On the other hand, there are also bottom-up initiatives to reframe the urban spatialities. For instance, Freytag and Bauder (Citation2018) analysed bottom-up transformation processes in Paris, firstly on the role of private accommodation, and Airbnb; and secondly, the urban mobility practices of pedestrians and cyclists by interconnecting various tourist hotspots and accommodation locations. On the demand side, new urban tourists look for everydayness and vernacular experiences, trying to immerse themselves in the local community (Füller & Michel, Citation2014). Thus, as Stors (Citation2022) pointed out, the pairing of new urban tourists and home-sharing trends are current bottom-up drivers of urban transformations, place making and image construction.

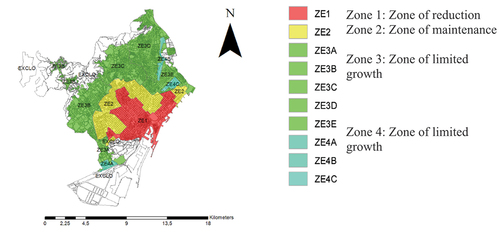

The objective of this article was to analyse how the positive evolution of tourist flows to Barcelona has given way to a rise in the city’s accommodation capacity, primarily tourist dwellings, thereby leading to changes in how the housing stock is used. Secondly, it has required from the authorities to pass legislation to curb the oversupply of tourist accommodation in certain parts of the city. The Special Tourist Accommodation Plan (PEUAT), which was approved in 2017, established areas where the tourist accommodation supply can increase (i.e., the least congested); areas where the current supply should stay the same; and areas where a reduction is encouraged. This plan responded to the need to make the city’s tourist accommodation compatible with a sustainable urban model and the lives of residents.

However, the PEUAT has been revoked in May 2021 by the courts. This article seeks to gain an insight into the impact of this containment plan. It examines how this expansion of tourist dwellings is expected to evolve and to determine the best way to tackle a spatial distribution more evenly throughout the city, given that today’s tourists seek immersion in the culture and daily life of the locals. For this reason, a new model for restricting tourist licences was formulated. This is, to find explicit answers to redistribute the tourism profit through the whole city and to reduce social vulnerability among neighbourhoods, as a counterpoint to the current PEUAT and face to GDS 11 to achieve sustainable cities.

In terms of methodology, the article used secondary data from the Government of Catalonia, Barcelona City Council and the platform of Airbnb with open data (www.insideairbnb.com) to identify the tourist housing offer in the city platform of Airbnb. The share of holiday rentals with respect to residential rentals was analysed through geographical information systems, in particular ArcGIS. All processed data were used to create a weighted matrix based on objectives such as creating a fair economy, attracting everyday tourists who want to assimilate into the neighbourhood, creating new tourist attractions, prioritizing tourist dwellings that have been granted tourist licences and avoiding high-density areas of tourist apartments. The results revealed the variables and actions that should be taken into account in future public policies and strategies in Barcelona city to distribute tourist housing throughout the city.

2. Touristification of urban destinations

Tourism plays a role in the urban transformation of cities (Hayllar et al., Citation2008). It primarily starts in terms of the expansion of private tourist accommodation through a shift in residential patterns and changes in the value of homes (Cócola-Gant, Citation2018; Gutiérrez et al., Citation2017). This so-called tourism gentrification has been analysed in different Spanish cities, such as Madrid and Barcelona (Crespi-Vallbona & Domínguez Pérez, Citation2021) or Seville (Jover & Díaz-Parra, Citation2020). Cities are also transformed as the traditional commercial fabric is replaced with new establishments intended for gastronomy and entertainment (Cordero & Salinas, Citation2017; López-Villanueva & Crespi-Vallbona, Citation2021). This hyperspecialization in business and tourist activities, known as the touristification process (Lanfant, Citation1994), whereby public spaces and cultural assets are resignified as consumable resources or marketing elements. As Nofre et al. (Citation2017) convey, this process of touristification is an epiphenomenon to other urban and social processes such as gentrification and the “recreational turn” of the post-industrial city. According to Hall (Citation2009), investments to adapt cities to attract tourists are prioritized, while the residents are overlooked.

In this sense, the willingness to geographically expand positive tourism effects has implied the creation of new centralities (as it is stated by Busquets, Citation2004) or new places (following Lew’s, Citation2017) of touristic interest. They are predominantly used and shaped by tourists and differentiated from non-tourist areas. Pappalepore et al. (Citation2014) framed these new tourism areas as vernacular and heterogeneous spaces, and their transformation involves gastronomic scene, creative and retail businesses, rising dwelling rents and a high volume of tourist sharing homes. Thus, tourism is understood in an economical diversified context, and according to a smart tourist destination (STD) perspective, its management involves five axes: technology, accessibility, sustainability, innovation, and governance (Segittur; Gretzel & Koo, Citation2021; Ivars-Baidal et al., Citation2019). As Vargas-Sánchez (Citation2016) pointed out the use of cutting-edge technologies creates an integrated network of management systems, platforms, and all kind of data (on mobility, energy consumption, etc.) that improve the whole management of the destination and, therefore, generate its differentiation and competitiveness. This will enable a more effective and efficient accessibility to products/services and promote tourist’s interaction (before, during and after the visit) with the destination and his/her integration in it. Furthermore, as Boes et al. (Citation2015) stated, a STD is built on the values of innovation and sustainability, working to improve the tourist’s experience and enhance the quality of life of local communities.

In short, a STD is an innovative destination with a technological base that guarantees sustainable and accessible economic development for all; that facilitates the interaction and integration of the visitor with the environment, increasing the quality of their experience at the destination; and that ensures the improvement of the quality of life of the resident. As Bouchon (Citation2022, p. 179) states, “using sustainable goals with smart technology will give a better yield for destinations and facilitate enhanced tourist experience in places facing over-tourism”.

This requires governance with the agents involved to guarantee this sustainability and shared inclusiveness (Errichiello & Micera, Citation2021). According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, Citation2010), governance is a practice of government capable to be measured, oriented towards efficiently direct the tourism sector at its various levels of government, through forms of coordination and cooperation between them in order to achieve the goals shared by networks of actors involved in the industry, aiming to achieve opportunities and solutions based on agreements sustained in the recognition of interdependences and shared responsibilities. As Vargas-Sánchez (Citation2016) highlighted, it involves three sections: those related to demand (this is, understanding the incoming markets and their satisfactory needs); those related to supply (knowledge of resources and products, providing networking, collaboration, and cooperation among stakeholders) and the alignment or coupling between supply and demand. This last function mainly means maintaining balance between industry changes and changes of the tourism model desired by the local community (residents); this is, developing and implementing strategic plans in the destination with an integrated and systemic capacity to generate synergies and resolve contradictions. In sum, this means an extensive coordination effort among the various players that make up the tourist mesh in the destination, taking into account a responsible smart governance, this is, based on the principles of ethics and justice (Gretzel & Jamal, Citation2020).

3. The platform economy and “everyday” tourism

This touristification of urban destinations is exemplified in the tendency towards housing shortages for residents, the shift from residential to tourist use of homes and their subsequent advertising on peer-to-peer accommodation platforms—a phenomenon dubbed “airbnbification” by Richards (Citation2016). This shift in uses stems from the revaluation of property or a rise in purchase and/or rental prices and leads to the eviction of residents and invasion by tourists. Thus, there has been a rise in homes whose owners prefer to exploit and rent them for tourism, rather than use them for residential purposes. This occurs for several reasons, most obviously because renting to tourists is more profitable (Wachsmuth & Weisler, Citation2018) and demand from tourists for this type of accommodation is growing (Richards, Citation2016). Furthermore, in the specific case of Airbnb, this type of travelling and being accommodated has shaped a common culture and identity from both sides, hosts, and guests, sometimes even creating a cult for groups of participants and a feeling of affiliation and belonging to the Airbnb community (Thompson, Citation2014). This experience for these Airbnb tourists represents to feel close to the day-to-day life of the residents and immerse more deeply in the neighbourhood (Maitland & Newman, Citation2008). Then, as Chen et al. (Citation2022) point out, Airbnb is a strong contributor to the diversification of tourism’s accommodation value chain. Moreover, Cohen and Kietzmann (Citation2014), Zach et al. (Citation2020), and Chen et al. (Citation2022) among others, state that Airbnb reduces injustice and inequalities of market economies as it engages ordinary citizens by providing them with opportunities for new and additional sources of income, in the same line that the UNWTO (Citation2022) considers that Airbnb contributes to Sustainable Development Goal 10 (reduced inequalities), despite of Andreoni (Citation2019) highlights that this sharing accommodation platform mainly benefits the middle or upper income levels of local residents and other scholars (Dolnicar & Zare, Citation2020; Gil & Sequera, Citation2020; Ki & Lee, Citation2019; Serrano et al., Citation2020) point out the existence of professional hosts with multiple listings.

Thus, controversy is present. The origin of Airbnb was to provide ordinary people with novel ways to make money from renting out spare space in their homes and hence promote more inclusive tourism development (Scheyvens & Biddulph, Citation2018). Furthermore, the spatial location of listings and the further concentration of tourism activities remains mainly in touristy neighborhoods, with effects on the local housing market. However, Kadi et al. (Citation2019) introduced the case of Airbnb extent in Vienna, less concentrated in the touristic centre and thus more extended through all the city, to consider this platform (and others, such as Homeaway, 9Flats or Housetrip) as inclusive and socially sustainable tourism, being understood that they are relevant part of contemporary tourism activities.

This supply is the answer to the current demand, as tourists want to stay in these private apartments so that they can “live like a local” (Füller & Michel, Citation2014; Gravari-Basbas & Delaplace, Citation2015) and immerse into residential zones, away from touristified ones. This trend is analysed as “off-the-beaten-tract” tourism (Maitland & Newman, Citation2008) or “new urban tourism” (Füller & Michel, Citation2014) and Airbnb has fostered it (Freytag & Bauder, Citation2018; Ioannides et al., Citation2018). As Minca and Roelofsen (Citation2019) proved, the Airbnb algorithms squeeze out a wide myriad of aspects of everyday life. Despite COVID-19 interruption, post pandemic times maintain this demand interest in being and behaving as a local, and peer accommodation has recuperated its reservation levels (Dolnicar & Zare, Citation2020). This immersion to local life highlights the need to emphasize ordinariness, daily life, local cuisine, local music, authenticity, genuineness, folklore, uniqueness and experiences rather than contemplative visits, and to focus on emotions and first-hand experiences in this new tourist perspective. The unique features of a location are coveted by tourists, who seek out cosmopolitan lifestyles and cultural sensibilities (Miles, Citation2007; Stebbins, Citation1997), gastronomic and gourmet establishments (Crespi-Vallbona & Dimitrovski, Citation2016), musical styles, vintage shops, craft beers, and so on (Bridge & Dowling, Citation2001; Ernst & Doucet, Citation2014; Zukin, Citation2008). Thus, old spaces and buildings (heritage assets or not), certain customs and everyday settings have come to be considered as tourist attractions with a strong local identity (Todt et al., Citation2008). There has also been a rise in consumers who seek other, more subdued experiences, away from official discourse (Rubio-Ardanz, Citation2014). In other words, experiences that are far removed from tourist hotspots; ordinary, humdrum, unsophisticated places, without official tourist value. As Smith (Citation2012) states, tourism conquer new urban frontiers and convert them in new consumption spaces, i.e., former industrial areas, working-class neighbourhoods in a process of degradation, semi-rural areas close to the city, etc. In this way, visitors become prosumers -people who not only consume but also co-produce a place through their own presence and performance (Edensor, Citation1998; Larsen, Citation2008). There is a clear example with the current interest of street art (Crespi-Vallbona, Citation2021).

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that the most contemporary promotion channel of a destination image is the user-generated content posted in social media platforms (Alcázar et al., Citation2014; Marine-Roig & Clavé, Citation2015) opposed to traditional DMO projection (Garay‐Tamajón & Morales‐Pérez, Citation2022). As Garay‐Tamajón and Morales‐Pérez (Citation2022) state, these series of webpages, as Airbnb, showcase places connected to the ideals of community identity, authenticity, and attachment, as well as neighborhoods to socialize, despite they also observe the complex relationship between the home sharing phenomenon and the commodification of destinations.

4. Sustainable governance

This phenomenon of placemaking (Lew, Citation2017) entails those urban peripheries become center not just geographically, but also symbolically from a touristic perspective. These urban peripheries refer to those neighborhoods outside the tourist bubble but part of the inner city and are economically activated through public policies and private investments. Hence, as Freytag and Bauder (Citation2018) stated Airbnb can convert day-to-day spaces that do not resemble the common tourist areas, but take a different shape, far away from mass tourism, where different or new forms of tourism are practiced. Anyway, current trend of new urban tourism even contributes to the process of urban change and remaking of places, as Stors (Citation2022) conveys in the Reuterkiez neighbourhood of Berlin. Thus, according to the line of Colomb’s (Citation2012), new tourist areas emerge from both sides: market and demand.

Hence, this interest in everydayness steers us towards the concept of the 15-minute city, an approach to transform urban spaces based on the relationship between space and useful time. This notion involves redeveloping all services so that they are accessible within 15 minutes of active mobility (i.e., by foot or by bike), rediscovering local amenities, ensuring that every area serves multiple purposes and salvaging public spaces to turn them into meeting places, living spaces. For Moreno (2015, cited in Mardones-Fernández de Valderrama et al., Citation2020), the quarter hour serves as a structural element; it is a time frame that allows residents to lead a more tranquil existence. It entails creating self-sufficient microcities within big cities, in which cars become less relevant and residents regain proximity to their fellow citizens. It also involves generating business models based on proximity or the economy of proximity. Ultimately, it consists of leaving urban planning to one side to focus on urban life planning. It is about thoroughly transforming urban spaces that are still highly monofunctional; turning single-centre cities and their particular amenities into cities with lots of centres to offer residents this quality of life within short distances and provide them with easier access to the six essential social functions of city life: living, working, supplying, caring, learning and enjoying. It is also important to reconstruct a sense of solidarity in cities where anonymity goes hand in hand with feelings of loneliness and suffering (Jacobs, Citation2013; Sennet, Citation2019). It is about moving towards a new model of urban life with multiple centres, breaking with a segmented functional urbanism and creating strong spatial and social segregation. 15-minute city reinforces the compact feature of life in urban areas giving new and renovated prominence to neighborhoods, local proximity, and everydayness (Barañano & Ariza, Citation2021; López-Villanueva & Crespi-Vallbona, Citation2023; Sennet, Citation2019).

Moreover, rediscovering proximity helps restore a sense of love for one’s local living spaces, i.e., topophilia, and thus create these essential new urban landscapes to satisfy tourists in search of everydayness. In fact, as Maitland (Citation2008) stated, parks and gardens are important places for tourists to have a rest, to refresh themselves, and to contemplate the urban environment, as well as to have the impression of mingling with the locals, sharing a moment with them, and feeling closer to their everyday experience.

In this sense, tourist policy that rules a destination has special interest, as its challenge is to find a balance between different interests: residents and tourists. This entails a new governance model in planning and developing new residents and tourists’ areas (Ioannides & Petridou, Citation2016). Innovative solutions are required to maintain the character and “authenticity” of neighborhoods, which in local cultural codes means the community atmosphere. Consequently, it requires the need of policy-makers regulations to find a balance between this complex dichotomy of tourism and citizenship, between tourism development and its real inclusiveness and profit distribution in the whole resident community, and negative effects of touristification by this home sharing phenomenon (Crespi-Vallbona & Domínguez Pérez, Citation2021; Morales-Pérez et al., Citation2020). In short, governance occupies a central place in tourism debates, where it is understood as the coordination of actors, social groups and institutions, whose objective is to obtain defined and deliberate results in a collective manner (Le Galès, Citation2010), solving existing situations of conflict, fragmentation, and inconsistency (Iglesias Alonso, Citation2021). In this sense, it is important to consider all potential actors, ranging from different levels of government, tourism businesses and private organizations, neighborhood associations, shopkeepers, and residents (Crespi‐Vallbona & López-Villanueva, Citation2023). In fact, as Rae (Citation2019) highlights there are desirable neighborhoods across the world that offer short-term rentals listed in home sharing platforms; these can be understood as neighborhood sharing and consequently, it becomes easier to understand residents’ opposition to not share their “globalhood” spaces with a worldwide cohort of travelers. These are the effects of fame and Instragramization. In consequence, as Bouchon (Citation2022) highlights, designing STD requires a greater focus on destination management style and governance mode.

5. Methodology and relevance of the study

The objective of this article was to analyse the rise in accommodation capacity in the city of Barcelona, especially tourist dwellings advertised through the platform economy, specifically on Airbnb. To that end, it was first necessary to contextualize Barcelona’s appeal as a tourist attraction. The next step was to analyse the way in which the accommodation advertised on Airbnb in the city of Barcelona has been growing. A projection of the future expansion of tourist dwellings in these territorial spaces was then shown, with a focus on the best way to distribute them evenly throughout the city and to please the new tourism demand trends.

In terms of methodology, the article used secondary data from the Government of Catalonia, Barcelona City Council and the platform Inside Airbnb. The data from the Inside Airbnb platform focus on the municipality of Barcelona. The open data available and free accessible from website of these institutions in CSV and SHP formats were processed and cleaned in GIS (geographical information system) programs, in this case ArcGIS (which is maintained by Esri). For the purposes of this study, several databases were processed: tourist dwellings, land registry maps (polygons), Airbnb listings, hotels, libraries, markets, hospitals, etc.

Data concerning of apartments listed on Airbnb website start in 2008 until now. Data related to tourism demand and accommodation infrastructure are from 1990 to now. Based on the data obtained, an analysis of the current situation was carried out. The databases were processed and cleaned to create heat maps and linked in order to identify study areas.

Based on the smart perspective and with the aim to provide sustainable, inclusive and competitive tourism options in a destination, all processed data were used to create a weighted matrix based on objectives such as creating a fair economy, attracting everyday tourists to assimilate into the neighbourhood, creating new tourist attractions, prioritizing tourist dwellings that have been granted tourist licences and avoiding a high density of tourist apartments. This made it possible to identify the variables and actions to include in future public policies and strategies in Barcelona with a view to distributing the positive impact of tourism evenly throughout the city and pleasing tourism demand of daily experiences.

6. Context: evolution of tourism in Barcelona

The turning point for tourism in Barcelona came in 1992, when the city hosted the Olympic Games and thus became a potential destination for many travellers. This put the city on the map and gave rise to the Barcelona brand. This intense evolution of demand flows in the city and its reception and accommodation of a huge volume of international tourists, except for during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure ), has gone hand in hand with various processes. First, the supply of amenities and cultural events to attract the interest of visitors has been bolstered. Second, the city’s accommodation capacity has increased steadily. Finally, the local DMO (destination management organization) has taken a holistic approach to governance to manage the different entities involved in tourism.

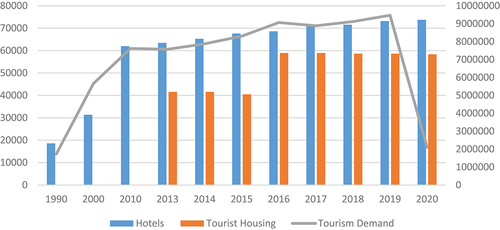

Figure 1. Evolution of tourism demand and tourist accommodation places in Barcelona (1990–2020).

This rise in the flow of tourists has been accompanied by a touristification process in the city due to the increased number of accommodation places to host the visitors (Figure ). In 1990, there were 18,569 hotel beds, compared to 73,700 in 2020. The system for granting licences for tourist dwellings was implemented in 2012 before the arrival of mass international tourism, thereby giving rise to a market for housing for non-residential purposes. Thus, this alternative type of regulated tourist accommodation also underwent significant growth, from 41,555 beds in 2013 to 58,333 in 2020.

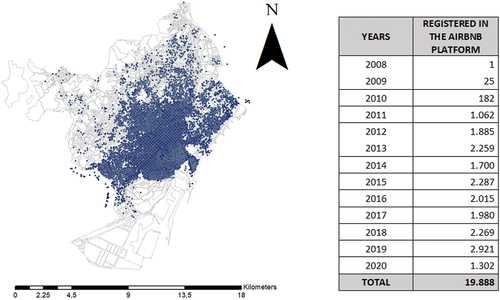

In addition, it is important to keep in mind that not all rooms and homes rented to tourists have the necessary licence to do so. Even though this practice is illegal, they are still advertised through peer-to-peer accommodation platforms such as Airbnb (Figure ).

Figure 2. Map of tourist flats listed on the Airbnb platform, 2020.

Barcelona’s rise as a popular tourist destination has immediate consequences for the citizens and the daily coexistence between tourists and permanent residents. This conflict with tourists has emerged as one of the key concerns expressed by residents. This rejection of temporary residents, together with the transformations that have affected the city (primarily gentrification and touristification), have forced the local authorities to plan actions and strategies to reconcile the needs of the different users and stakeholders who coexist in Barcelona and the metropolitan area. Such strategies include, for instance, the 2013 regulation to limit the capacity of Parc Güell by controlling access to the monumental area, which was declared a World Heritage Site, to avoid tourist overcrowding (Crespi-Vallbona & Smith, Citation2019).

Furthermore, the strategic plans prepared and approved by Barcelona City Council (1993, 2010 and 2016) sought to position Barcelona economically within the European framework, establish it as a tourist destination with a range of accommodation and cultural assets for both pleasure and knowledge, and ensure that permanent and temporary residents could continue to live together. In this regard, the PEUAT was approved in 2017. This defined city zones according to their accommodation capacity and encouraged or limited their growth, in addition to stepping up measures to control illegal or unregulated tourist apartments (Figure ). The plan defined zone 1, the reduction zone, which included Ciutat Vella, part of the Eixample, Poblenou, Vila Olímpica, Poble Sec, Hostafrancs and Sant Antoni, where new accommodation facilities cannot be opened and tourist licences cannot be issued; zone 2, the maintenance zone, where new facilities can only be opened if existing ones close; and zones 3 and 4, where growth is limited. For now, despite the cancellation of the plan, Barcelona City Council has suspended applications for permission to open new tourist apartments.

7. Evolution and density of tourist apartments in Barcelona

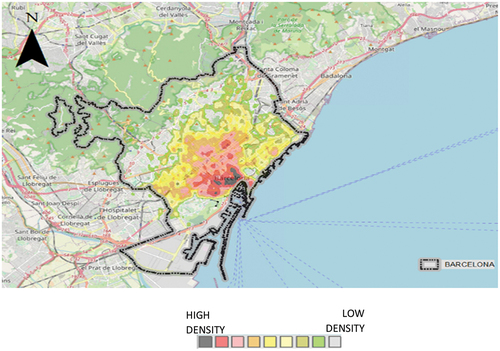

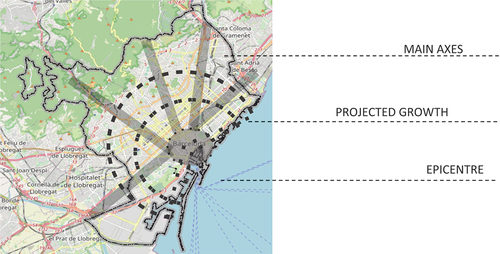

The appeal of the Barcelona brand lies in its historical and cultural centre, but its influence extends into the rest of neighborhoods. Airbnb is one of the most popular holiday rental booking platforms and the one that most reflects this remarkable growth (Figure ). The density of tourist apartments is concentrated in the historic centre of Barcelona (this is clearly visible in grey) and is gradually creeping into its boundaries (Figure ). The map also reveals how this density is spreading in a radial fashion throughout the territory, in the city’s various districts. This concentration of tourist dwellings in the city centre, which is home to the main amenities and tourist attractions, is a recurrent phenomenon in many popular tourist cities (Benítez-Aurioles, Citation2017).

Figure 4. Heat map of tourist flats listed on the Airbnb platform, 2020.

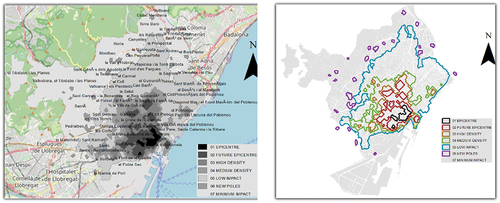

A detailed analysis of this growth in tourist dwellings in Barcelona made it possible to observe how this increase in tourist apartment listings on Airbnb is taking shape, with the formation of different polygons in the territory (Figure ).

Figure 5. Formation of polygons in the territory according to the density of apartments on Airbnb.

These heat maps revealed different density levels and made it possible to plot the parts of the territory with the greatest impact. The maps clearly show the epicentre and how growth is taking place in a radial fashion, thereby making it possible to predict future lines of growth (Figure ).

Figure 6. Projected growth of holiday rental listings on Airbnb.

This analysis of the historical evolution of tourist dwelling listings on the Airbnb platform concludes that this radial growth around the epicentre is due to two key variables: the location of the city’s tourist attractions, and the transportation and metro stations that connect the city. This is also confirmed by different scholars (Gutiérrez et al., Citation2017; Xu et al. (Citation2019).

Definitely, as Cuscó Puigdellívol and Font Garolera (Citation2015) state, Barcelona, due to its geographical conditions, as well as the diversity of its resources (natural and cultural), cannot ignore the growing importance of the tourism phenomenon and must integrate it into its territorial, urban, and sectoral policies. The tourist is today a temporary citizen who must be reckoned with and who will probably have to be reckoned with even more in the future, both as a customer of the conventional sector (hotels and tourist apartments) or as a user of conventional homes with tourist use.

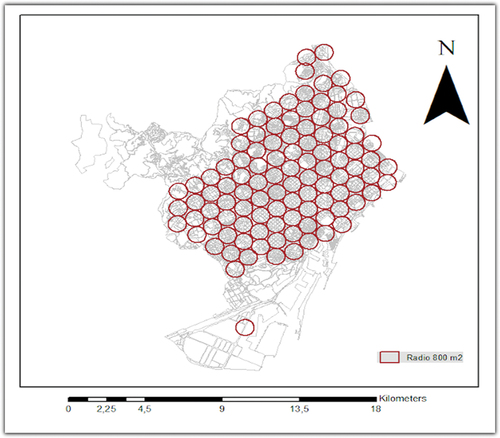

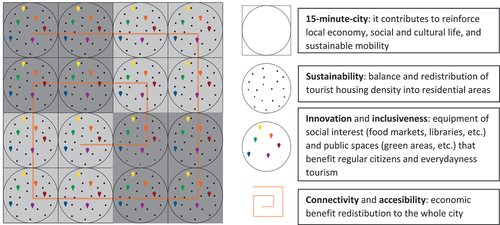

8. Projecting the growth in tourist dwellings

To project growth, the new “15-minute city” concept was considered; according to this model, all amenities needed for daily life should be available within an 800-metre radius, including those relating to healthcare, commerce, transport, culture and education. To achieve this, 800-metre radii were plotted across the city, as shown in Figure . Residents look for this proximity and everydayness (Jacobs, Citation2013; Sennet, Citation2019). Also everyday tourism appreciates these new consumption spaces (Smith, Citation2012).

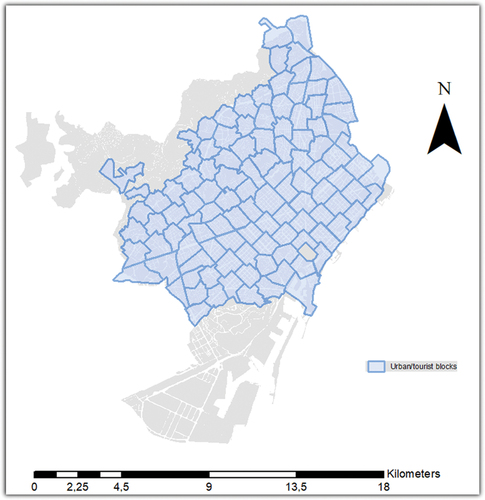

These radii created guidelines to plot the new polygons, called “urban/tourist blocks”, which covered an average area of approximately 100 km2 (Figure ). These urban/tourist blocks made it possible to conduct a more detailed study of the territory and how it is managed. Thus, the information was extracted individually, and a new georeferenced database was created to determine the suitability for granting new tourist dwelling licences in residential areas.

To obtain a new perspective on the redistribution of tourist dwellings, we implemented the weighted matrix methodology, which considered the following criteria in a hierarchical order: contribution to the local economy of economically and socially vulnerable neighbourhoods (according to Barcelona City Council’s Neighbourhood Plan); the interest in offering tourists an experience of everyday life; the existence of cultural and natural attractions; the number of regulated tourist accommodation establishments; and the density of tourist dwellings with or without licences. Table shows the different zones and their weighting.

Table 1. Weighted matrix

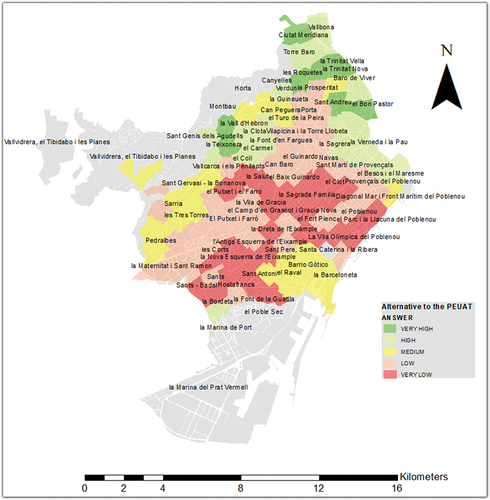

After applying the weighted matrix to each urban/tourist block, the total was coded by bands to show the level of interest in new tourist licences. In other words, a VERY HIGH level of interest in granting new tourist licences was indicated by a score of 11 to 14 points (zone 1); HIGH interest was 8 to 10 points (zone 2); MEDIUM interest was 5 to 7 points (zone 3); LOW interest was 2 to 4 points (zone 4); and VERY LOW or NON-EXISTENT interest was −1 to 1 points (zone 5). Once the weighted matrix had been applied to each urban/tourist block, the zones were marked out in five colours (Figure ).

Figure 9. Map of Barcelona with the proposed alternative to the PEUAT for granting tourist licences.

This alternative to the PEUAT for granting tourist licences according to each urban/tourist block resulted in five zones delineated by five colours. The dark green area (zone 1) included peripheral areas in which new tourist apartments represent a very high priority, since these areas require social and economic revitalization and have great potential to offer tourists a large dose of everyday life, according to the neighbourhood’s cultural and social amenities. The light green area (zone 2) is characterized by a high level of interest in granting tourist licences, since it too presents a certain degree of vulnerability and has great potential to provide new tourists in search of an immersive experience with everyday reality.

In the urban/tourist blocks with high and very high interest levels, both the council and tourism companies willing to invest in these areas must pay particular attention to infrastructure works.

According to the weighted matrix, the yellow area (zone 3) presents a certain balance. Thus, although Barcelona City Council considers the Gothic Quarter and Raval to be vulnerable neighbourhoods, and despite the fact that the epicentre of airbnbification started in these areas, it was evident after applying the weighted matrix that the level of interest in granting tourist licences was medium. In this special case, it was considered necessary to thoroughly review the tourist licences that have already been issued and ensure that the apartments listed on Airbnb are legal.

In the pink area (zone 4) and the red area (zone 5), there is very little or no interest in offering more tourist licences, since they already benefit from regulated accommodation, numerous tourist dwellings, tourist attractions and amenities, have not been identified as vulnerable by Barcelona City Council’s Neighbourhood Plan and are located in areas with mass tourism, such that the daily life of the locals is virtually indistinguishable.

This creation of urban/tourist blocks represents another approach to address the shifting use of housing in the city of Barcelona. The existing PEUAT focuses on creating zones in the city according to the tourist accommodation they offer. A recently published study used another model to rebalance the city’s levels of tourist accommodation (Pons, Citation2021). This is known as “derived proportional load”, which involves dividing the urban territory into small areas. Decompressive shock waves are distributed from the centre and the balanced level of tourist accommodation is estimated based on these. Thus, an algorithm is applied and when areas closest to the centre reach a certain, pre-agreed proportion of uses, the tourist quota that exceeds the stipulated quota is rerouted to the next concentric wave. These beds are projected to the next section and so on until the desired proportions are reached in different neighbourhoods, without being confined to pre-established enclaves. The study proposed a load and use index of 80% residential, 10% tourism, 5% offices and 5% commercial.

In our case, following an STD perspective, and thus, with the objective to provide sustainable, inclusive, accessible, innovative and competitive tourism options in a destination, the proposed model of redistribution of tourist accommodation licences was based on five strategic pillars: economic benefits for vulnerable neighbourhoods; tourist demand for everydayness; the existence of cultural and natural attractions; the density of regulated tourist accommodation; and the density of tourist dwellings. Ultimately, this model seeks to find a balance among all the stakeholders’ interests: residents, visitors, and private businesses. The Figure summarises this contribution, as, in the case of Barcelona, the need to reconsider the PEUAT and its exhaustive control of tourist licenses for housing, this model represents a fresh initiative to redistribute tourism benefits through the city.

The first pillar, concerning benefits for economically and socially vulnerable neighbourhoods, is underpinned by the need to contribute to the local economic wealth, since tourists spend more than half their time near their accommodation and tend to spend money on services close to their accommodation, including food, leisure, shopping, and small-scale transport. This aspect is linked to the concept of inclusive tourism development as tourist activity in these vulnerable neighborhoods can provide a holistic range of benefits and lead to more equitable and sustainable outcomes and an opportunity for these places to be on the tourism map (Scheyvens & Biddulph, Citation2018). Furthermore, tourists who want to experience day-to-day as locals in non-tourist areas are still tourists with all their tourist needs and demands and have a direct effect on the neighbourhood and the infrastructure. In that sense, Airbnb hosts assume the role of “cultural intermediaries’ to enact and convert humdrum and ordinary places in authentic and exotic enclaves, as Stors (Citation2022) described in the immigrant and poor neighbourhood of Reuterkiez in Berlin.

The second pillar takes account of the growing interest in today’s tourists who seek everydayness on their travels; ordinary, everyday spaces that allow them to really immerse themselves in the destination (Smith, Citation2012). The third pillar focuses on the territory’s cultural and natural attractions with a view to showcasing them (Colomb, Citation2012). The fourth pillar measures the number of regulated tourist accommodation establishments to avoid saturating the polygon. And finally, the fifth pillar also assesses the density of tourist apartments (both with and without licences and residential zone) to decongest and rebalance the tourist accommodation distribution areas in the city of Barcelona (following Ioannides & Petridou’s, Citation2016). Ultimately, this creation of urban/tourist blocks represents another approach to address the shifting use of housing in the city of Barcelona, now that it seems that the PEUAT will end up being definitively overturned by the courts. It represents a new, fairer and more inclusive redistribution model.

This model tries to solve conflicting interests among residents and visitors, and unequal distribution of economic resources and political power. It represents a major challenge for urban tourism developers managing their task to balance and regulate the spatio-temporal organization of multifunctional activities by visitors, residents, and various other economic, political, social and cultural actors in the city. It is a challenge for technicians and urban planners, to find new tourist sites of interest and new tourist packages for “everyday tourists” that are in harmony with the neighborhood.

9. Conclusions

As other cities, such as London (Xu et al., Citation2019), Madrid (Gil & Sequera, Citation2020) among others, the evolution of tourist accommodation in the city of Barcelona is characterized by radial growth, from a central hub to the surrounding neighbourhoods. Tourist dwellings specifically are located near tourist attractions, communication nodes and interurban public transport. This impact is also expected to spread from the epicentre of Barcelona to the surrounding neighborhoods. To that end, this research reveals the type of variables that should be taken into account in future public policies to address the impact of tourism, maintaining a balance among residents and everydayness interest of new trends of demand. Definitely, the objective is providing a new approach to policy reflection related to urban social cohesion and responsible smart tourism management.

Mobility between the city has intensified thanks to public transport and urban improvements. This has given rise to the dispersion and expansion of tourist dwelling listings on platforms such as Airbnb. Thus, tourism disregards the city’s geographical borders and its externalities spread. Tackling this situation requires broad agreement between institutions; confirmation of the value of public-private collaboration; and new governance tools to achieve consensus and activate fairer, more inclusive policies, such as the creation of urban/tourist blocks with a view to reviving the economy of the most vulnerable neighbourhoods and offering visitors in search of genuine immersion in their destination a dose of everyday life. As Stors (Citation2022) states, visitors of urban destinations are leaving the confines of tourist zones and venturing into residential and ordinary neighbourhoods, provided by sharing-platforms as shown in the residential neighbourhood of Reuterkiez (in Berlin).

Based on a STD perspective and with the aim to provide sustainable, inclusive, accessible, innovative and competitive tourism options in a destination, a new management model for redistributing tourist accommodation licences is proposed based on five strategic pillars: economic benefits for vulnerable neighbourhoods; tourist demand for everydayness; the existence of cultural and natural attractions; the density of regulated tourist accommodation; and the density of tourist dwellings and residential zone. This new redistribution model seeks a fair distribution of the wealth generated by tourism by supporting the trend toward everyday tourism and including vulnerable areas of the city. In addition, it facilitates the interaction and integration of the visitor with the environment, increasing the quality of their experience at the destination. A smart and sustainable governance implies a holistic vision, this is, focusing the attention on the economic viability and competitiveness of the city, taking into account the social needs of the vulnerable and also well-off citizens, and lastly, the management of tourists’ satisfaction. Therefore, the implementation of this model of smart tourism management and distribution flows through the whole city will depend on the politic ideals of the parties who run Barcelona, and the specific way they have understanding the balance and coexistence of tourism and citizenship in the same urban space or globalhood. Despite the tourismophobic social movements and some anti-tourism discourses of politicians and scholars, there is no doubt that tourism is an economic, cultural and social driving force and requires the courage of responsible managers to go against de current tide. But political parties depend on citizen votes to keep its power, and sometimes forget the well-being and future of the territory they run. In addition, it also should be noted that there are diverse tourist motivations that compile as embellished places as ordinary neighbourhoods, also peer accommodation and hotel infrastructure. Thus, a smart tourist destination just depends on the will to redistribute in a fair, inclusive, and transparent manner the tourism impacts for all and across the whole urban boundaries.

Future research will focus on residents and social fabric’s perception of this transformation of their neighbourhoods in attractive areas where placemaking policies will have driven the urban and commercial changes into new tourism centralities maintaining these places for their citizens. Not in vain, managing a smart tourism destination must ensure the improvement of the quality of life of its residents. In this sense, it will also be interesting to analyse the impact of bike lanes in the city and boundaries and tourist use of this public service of Bicing, and also the spread of green areas or Superilles to the whole city. It will be interesting to compare this model with other similar approaches in other cities, as tourism is not going to disappear, and has necessarily to coexist with residents’ quality of life and businesses which get profit with commercial activities. It also will be interesting to compare this case with other cities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Project entitled Nuevas movilidades y reconfiguracion sociorresidencial en la poscrisis: consecuencias socioeconomicas y demograficas en las areas urbanas españolas (RTI2018-095667-B-I00), approved by the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Montse Crespi Vallbona

PhD. Montserrat Crespi-Vallbona Researcher associate professor at the Business Department at the University of Barcelona (UB), Spain. Member of the Business Research Group (UB) and researcher at the Investigation Project (I+D) New mobilities and socioresidential reconfiguration in the postcrisis context. She has two lines of research. One is related to the analysis of the evolution and dynamics of tourism activity and its driving force. The tourism impacts on economic, social, cultural, and urban structures of the territory. This research is the continuation of her previous studies and analyzed data in my doctoral thesis (2002). Governance, gentrification, sustainability are the key words. The other area of research is linked to traditional and digital hospitality organizations, CSR, and human capital issues. Crucial aspects as motivation, professional skills, resilience, values, leadership, and women’s empowerment etc. that focus on the interest and success of companies.

Published papers: Satisfying experiences: guided tours at cultural heritage sites. Journal of Heritage Tourism (2020). Street Art as a Sustainable Tool in Mature Tourism Destinations: A Case Study of Barcelona. International Journal of Cultural Policy (2020). Wine lovers: their interests in tourist experiences. International Journal of Culture, Tourism, and Hospitality Research (2020). Managing Sociocultural Sustainability in Public Heritage Spaces. Tourism Planning and Development (2019). Desarrollo turístico inclusivo. El caso de los desmovilizados en Chocó, Colombia. Cuadernos Geográficos (2019). Urban food markets and their sustainability: the compatibility of traditional and tourist uses. Current Issues in Tourism (2019). Job satisfaction. The case of information technology (IT) professionals in Spain. Universia Business Review (2018). La transformación y gentrificación turística del espacio urbano. El caso de la Barceloneta (Barcelona). Eure, Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Urbano Regionales (2018). Urban Food Markets in the Context of a Tourist Attraction – La Boqueria Market in Barcelona, Spain”. Tourism Geographies (2018). Role of food neophilia in food market tourists’ motivational construct. The case of La Boqueria (Barcelona, Spain), Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing (2017). Food Markets from a Local Dimension –La Boqueria (Barcelona, Spain). Cities (2017). Food markets visitors: a typology proposal, British Food Journal (2016). Shared values in the Spanish company, Universia Business Review (2013). Determinant variables of job satisfaction in Spain, Cuadernos de Economía. Journal of Economics and Finance (2012). The meaning of Cultural Festivals: Stakeholder perspective in Catalunya, International Journal of Cultural Policy (2007). Books and chapters: La sostenibilidad turística de los centros urbanos. Los mercados de abastos (2019, CIS). Connections between Agritourism and Urban Food Markets: The Case of La Boqueria in Barcelona, Spain (2018, Routledge). Enología e identidad: maridaje turístico (2017, Síntesis). Cultural heritage, leisure, and citizenship: A case study of La Boqueria food market in Barcelona (Spain) (2017, World Leisure Organization). Turismo y ciudad (2015, Síntesis). Sistemas y Servicios de Información Turística (2014, Sintesis). Recursos turísticos (2011, Sintesis). Productos y destinos turísticos nacionales e internacionales (2006, Síntesis).

Sofia Galeas Ortiz

Mgs. Sofia Galeas Ortiz Urban architect from the Central University of Ecuador with a specialty in the development of tourist destinations and preparation of special territorial plans.

She worked for the Quito city council in planning and territorial development mainly in laws such as: Informal street commerce, food trucks, neighborhood identity and accessible public spaces, and was part of the planning team of the new city Yachay - Ecuador, through the application of transect and morphological codes.

Published paper: Desarrollo turístico inclusivo. El caso de los desmovilizados en Chocó, Colombia. Cuadernos Geográficos (2019).

References

- Alcázar, M., Piñero, M., & Maya, S. (2014). The effect of user-generated content on tourist behavior: The mediating role of destination image. Tourism & Management Studies, 10, 158–19. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3887/388743880019.pdf

- Andreoni, V. (2019). Sharing economy: Risks and opportunities in a framework of SDGs. In W. Filho & A. Azuk (Eds.), Sustainable cities and communities. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71061-7_60-1

- Barañano, M., & Ariza, J. (2021). Complejidades e incertidumbres en torno al impacto de la COVID-19 en las grandes ciudades: entre los arraigos y las movilidades. In O. Salido & M. Massó (Eds.), Socilogía en tiempos de pandemia. Impactos y desafíos sociales de la crisis del COVID-19 (pp. 91–104). Marcial Pons. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2zp4xbt.9

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. (2017). The role of distance in the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation. Tourism Economics, 24(3), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816617726211

- Boes, K., Buhalis, D., & Inversini, A. (2015). Conceptualising smart tourism destination dimensions. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015 (pp. 391–403). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14343-9_29

- Bouchon, F. (2022). Smart tourism destination. In D. Buhalis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of tourism management and marketing (pp. 127–130). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bridge, G., & Dowling, R. (2001). Microgeographies of retailing and gentrification. Australian Geographer, 32(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180020036259

- Busquets, J. (2004). Barcelona: La construcción urbanística de una ciudad compacta. Ediciones del Serbal.

- Chen, G., Cheng, M., Edwards, D., & Xu, L. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic exposes the vulnerability of the sharing economy: A novel accounting framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(5), 1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1868484

- Cócola-Gant, A. (2018). Tourism gentrification. In L. L. Y. En & M. Phillips (Eds.), Handbook of Gentrification Studies (pp. 281–293). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785361746.00028

- Cohen, B., & Kietzmann, J. (2014). Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organization & Environment, 27(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026614546199

- Colomb, C. (2012). Staging the New Berlin. Place marketing and the politics of urban reinvention post-1989. Sage.

- Cordero, L., & Salinas, L. A. (2017). Gentrificación comercial. Espacios escenificados y el modelo de los mercados gourmet. Revista de Urbanismo, 37(37), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5354/0717-5051.2017.45735

- Crespi‐Vallbona, M., & López-Villanueva, C. (2023). Citizen resistance in touristified neighbourhoods. A post-pandemic analysis. In E. Navarro-Jurado, R. Larrubia Vargas, F. Y. Almeida Garcia, & J. J. Natera Rivas (Eds.), Urban dynamics in the post-pandemic period: tourist spaces and urban centres. The urban book series In press. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36017-6

- Crespi-Vallbona, M. (2021). Gobernanza sostenible en los espacios públicos. Cuadernos de Geografía: Revista Colombiana de Geografía, 31(1), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcdg.v31n1.87168

- Crespi-Vallbona, M., & Dimitrovski, D. (2016). Food markets visitors: A typology proposal. British Food Journal, 118(4), 840–857. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-11-2015-0420

- Crespi-Vallbona, M., & Domínguez Pérez, M. (2021). Las consecuencias de la turistificación en el centro de las grandes ciudades. El caso de Madrid y Barcelona. Ciudad y Territorio, 2021, 61–82. Estudios Territoriales, LIII, Monográfico. https://doi.org/10.37230/CyTET.2021.M21

- Crespi-Vallbona, M., & Smith, S. (2019). Managing Sociocultural Sustainability in Public Heritage Spaces. Tourism Planning & Development, 17(6), 636–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1683885

- Cuscó Puigdellívol, E., & Font Garolera, J. (2015). Nuevas formas de alojamiento turístico: comercialización, localización y regulación de las ‘viviendas de uso turístico’ en Cataluña. Revista bibliográfica de geografía y ciencias sociales, Biblio 3W, XX(1.134). https://doi.org/10.1344/b3w.0.2015.26123

- Dolnicar, S., & Zare, S. (2020). COVID19 and Airbnb. Disrupting the disruptor. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961

- Edensor, T. (1998). Tourists at the Taj. Performance and meaning at a symbolic site. Routledge.

- Ernst, O., & Doucet, B. (2014). A window on the (changing) neighbourhood: The role of pubs in the contested spaces of gentrification. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 105(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12071

- Errichiello, L., & Micera, R. (2021). A process-based perspective of smart tourism destination governance. European Journal of Tourism Research, 29, 2909. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v29i.2436

- Freytag, T., & Bauder, M. (2018). Bottom-up touristification and urban transformations in Paris. Tourism Geographies, 20(3), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1454504

- Füller, H., & Michel, B. (2014). “Stop being a tourist!” New dynamics of urban tourism in Berlin-Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1304–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12124

- Garay‐Tamajón, L. A., & Morales‐Pérez, S. (2022). ‘Belong anywhere’: Focusing on authenticity and the role of Airbnb in the projected destination image. International Journal of Tourism Research, 25(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2551

- Gil, J., & Sequera, J. (2020). The professionalization of Airbnb in Madrid: Far from a collaborative economy. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(20), 3343–3362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1757628

- Gravari-Basbas, M., & Delaplace, M. (2015). Le tourisme urbain “hors des sentiers battus”. Coulisses, interstices et nouveau territoires touristiques urbains. Téoros: Revue de recherche en tourisme, 34(1–2). https://doi.org/10.7202/1038815ar

- Gretzel, U., & Jamal, T. (2020). Guiding principles for good governance of the smart destination. Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally, 42. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/ttra/2020/research_papers/42

- Gretzel, U., & Koo, C. (2021). Smart tourism cities: A duality of place where technology supports the convergence of touristic and residential experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1897636

- Gutiérrez, J., Garcia-Palomares, J. C., Romanillos, G., & Salas-Olmedo, M. H. (2017). The eruption of Airbnb in tourist cities: Comparing spatial patterns of hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation in Barcelona. Tourism Management, 62, 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.05.003

- Hall, C. M. (2009). El turismo como ciencia social de la movilidad. Síntesis.

- Hayllar, B., Griffin, T. & Edwards, D. Eds. (2008). City Spaces – Tourist Places: A Reprise. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-8195-7.00018-4

- Iglesias Alonso, A. (2021). La gobernanza local del turismo rural como respuesta a los efectos de la Covid-19. BARATARIA Revista Castellano-Manchega de Ciencias Sociales, 30(30), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.20932/barataria.v0i30.614

- Ioannides, D., & Petridou, E. (2016). Contingent neoliberalism and urban tourist in the United States. In J. Mosedale (Ed.), Neoliberalism and the political economy of Tourism (pp. 21–36). Routledge.

- Ioannides, D., Röslmaier, M., & van der Zee, E. (2018). Airbnb as an instigator of ‘tourism bubble’ expansion in Utrecht’s Lombok neighborhood. Tourism Geographies, 21(5), 822–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1454505

- Ivars-Baidal, J. A., Celdrán-Bernabeu, M. A., Mazón, J. N., & Perles-Ivars, Á. F. (2019). Smart destinations and the evolution of ICTs: A new scenario for destination management? Current Issues in Tourism, 22(13), 1581–1600. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1388771

- Jacobs, J. (2013). Muerte y vida de las grandes ciudades. Madrid. Capitan Swing.

- Jover, J., & Díaz-Parra, I. (2020). Who is the city for? Overtourism, lifestyle migration and social sustainability. Tourism Geographies, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1713878

- Kadi, J., Plank, L., & Seidl, R. (2019). Airbnb as a tool for inclusive tourism? Tourism Geographies, 24(4–5), 669–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1654541

- Ki, D., & Lee, S. (2019). Spatial distribution and location characteristics of Airbnb in Seoul, Korea. Sustainability, 11(15), 4108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154108

- Lanfant, M. (1994). Identité, mémoire et la touristification de nos sociétés. Sociétés. Revue des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, 46, 433–439.

- Larsen, J. (2008). De-exoticizing tourist travel: Everyday life and sociality on the move. Leisure Studies, 27(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360701198030

- le Galès, L. (2010). « Gouvernance ». In Boussaguet L. (eds.) Dictionnaire des politiques publiques (pp.299–308) Presses de Science Po.

- Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007

- López-Villanueva, C., & Crespi-Vallbona, M. (2023). Cuidados y arreglos. La importancia del arraigo al barrio en un contexto de pandemia. El caso de la ciudad de Barcelona. RES (Revista Española de Sociología).

- Maitland, R. (2008). Conviviality and everyday life: The appeal of new areas of London for visitors. International Journal of Tourist Research, 10(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.621

- Maitland, R., & Newman, P. (2008). Visitor–host relationships: conviviality between visitors and host communities. In B. Hayllar, T. Griffin, & D. Edwards (Eds.), City spaces – Tourist places: Urban tourism precints (pp. 223–242). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-8195-7.00011-1

- Mardones-Fernández de Valderrama, N., Luque-Valdivia, J., & Aseguinolaza-Braga, I. (2020). La ciudad del cuarto de hora, ¿una solución sostenible para la ciudad postCOVID-19? Ciudad y Territorio, Estudios Territoriales, LXII(205), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.37230/CyTET.2020.205.13.1

- Marine-Roig, E., & Clavé, S. A. (2015). Tourism analytics with massive user-generated content: A case study of Barcelona. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.004

- Miles, M. (2007). Cities and Cultures. Routledge.

- Minca, C., & Roelofsen, M. (2019). Becoming Airbnbeings: On datafication and the quantified Self in tourism. Tourism Geographies, 23(4), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1686767

- Morales-Pérez, S., Garay, L., & Wilson, J. (2020). Airbnb’s contribution to socio-spatial inequalities and geographies of resistance in Barcelona. Tourism Geographies, 24(6–7), 978–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1795712

- Nofre, J., Giordano, E., Eldridge, A., Martins, J., & Sequera, J. (2017). Tourism, nightlife and planning: Challenges and opportunities for community liveability in La Barceloneta. Tourism Geographies, 20(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1375972

- Novy, J. (2013). “Berlin Does Not Love You”. In M. Bernt, B. Grell, & A. Holm (Eds.), The Berlin reader: A companion on urban change and activism (pp. 223–238). Transcript. https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839424780.223

- Pappalepore, I., Maitland, R., & Smith, A. (2014). Prosuming creative urban areas. Evidence from East London. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.11.001

- Pons, T. (2021). Carga proporcional derivada: aplicación al destino Barcelona. EAE.

- Rae, A. (2019). From neighbourhood to “globalhood”? Three propositions on the rapid rise of short-term rentals. Area, 51(4), 820–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12522

- Richards, G. (2016). El turismo y la ciudad: ¿hacia nuevos modelos? Revista Cidob d´afers internacionals, 113(113), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2016.113.2.71

- Rubio-Ardanz, J. A. (2014). Antropología y Maritimidad. Entramados y constructos patrimoniales en el Abra y Ría de Bilbao. Museo Marítimo Ría de Bilbao.

- Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. (2018). Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1381985

- Sennet, R. (2019). Construir y habitar. Ética para la ciudad. Barcelona, Anagrama.

- Serrano, L., Sianes, A., & Ariza-Montes, A. (2020). Understanding the implementation of Airbnb in urban contexts: Towards a categorization of European cities. Land, 9(12), 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120522

- Smith, N. (2012). La nueva frontera urbana. Ciudad revanchista y gentrificación. Traficantes de Sueños.

- Stebbins, R. A. (1997). Identity and cultural tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 450–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-73839780014-X

- Stors, N. (2022). Constructing new urban tourism space through Airbnb. Tourism Geographies, 24(4–5), 692–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1750683

- Thompson, D. (2014). Turning customers into cultists. The Atlantic, 314(5), 26–32.

- Todt, H., Herder, J. G., & Dabija, D. C. (2008). The role of monument protection for tourism. Amfiteatru Economic, 10, 292–297.

- UNWTO. (2010). Project on governace for the tourism sector. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.11.001

- UNWTO. (2022). Tourism for SDGs. UNWTO: United Nation World Tourism Organization. http://tourism4sdgs.org/

- Vargas-Sánchez, A. (2016). Exploring the concept of smart tourist destination. Enlightening Tourism A Pathmaking Journal, 6(2), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.33776/et.v6i2.2913

- Wachsmuth, D., & Weisler, A. (2018). Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environment and Planning: Economy and Space, 50(6), 1147–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18778038

- Xu, F., Hu, M., La, L., Wang, J., & Huang, C. (2019). The influence of neighbourhood environment on Airbnb: A geographically weighed regression analysis. Tourism Geographies, 22(1), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1586987

- Zach, F., Nicolau, J., & Sharma, A. (2020). Disruptive innovation, innovation adoption and incumbent market value: The case of Airbnb. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102818

- Zukin, S. (2008). Consuming authenticity: From outposts of difference to means of exclusion. Cultural Studies, 22(5), 724–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380802245985