Abstract

The article consists in an in-depth interpretative study of Smart City in the case of the Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong, China. It proposes a framework of analysis as a heuristic tool to interpret narratives in general and those of Smart City Hong Kong in particular. The capacity of a narrative to confer meaning draws upon three criteria: its originality (degree of endogeneity); its sincerity (internal validity and trustworthiness), and its extension (its ability to provide a convincing account to the outside world for social phenomena). They are also affected by the form of diffusion and communication. Four types of account emerged from our empirical investigation: survey responses; written responses from official agencies; face to face interviews; and collective interviews in focus groups. By reconstituting chains of meaning in relation to the Smart City, the article interrogates the utility of technology, sustainability and e-governance narratives for public administration. Taken as a whole, Smart City appears as a rather hollow narrative, an empty signifier, a general term lacking clear meaning.

Public interest statement

The article aims at interpreting narratives of Smart City with Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China in focus. It develops an analytical framework to study narratives in general and those of Smart City Hong Kong in particular. Narratives can confer meaning depending on their originality, internal validity and trustworthiness, and ability to provide a convincing account to the outside world for social phenomena. Narratives are also affected by the form of diffusion and communication. The article collects data from survey responses, written responses from official agencies, face to face interviews, and collective interviews in focus groups. The article questions the usefulness of technology, sustainability, and e-governance narratives for public administration by reconstituting chains of meaning in relation to the Smart City. Taken as a whole, Smart City appears as a general term lacking clear meaning.

1. Introduction

In December 2020 the Hong Kong Government published the second edition of The Smart City Blueprint for Hong Kong (original December 2017). The Blueprint proposes measures to build Hong Kong into a world class smart city and makes recommendations with regard to six major smart areas of mobility, living, environment, people, government and economy. While the original Smart City Blueprint, published in 2017, identified 76 initiatives under the six dimensions, the revised Blueprint 2.0 of 2020 further expanded the number of initiatives to over 130 (Innovation and Technology Bureau, Citation2020). The missions are to raise the quality of life, attract the capitalization of businesses, promote social inclusion of the elderly, and make the city more environmentally friendly.

Through retracing three inductively reconstituted urban “narratives”, the article focuses on the Smart City in Hong Kong. The term “Smart City” has been used in different contexts since the 1990s, when it was first employed in the United States to describe the use of ICT (information and communication technologies) applications in modern urban infrastructures (Gibson et al., Citation1992). Various similar concepts have appeared such as digital city, intelligent city, knowledge city, and wired city, in the attempt to specify this fuzzy concept (Albino et al., Citation2015; Camero & Alba, Citation2019; Caragliu et al., Citation2011; Cocchia, Citation2014; Patrão et al., Citation2020; Sharifi, Citation2019, Citation2020). Common across these descriptors is the presence of ICT, which is used to enhance efficiency and address city development challenges, including safety and aging populations (Akande et al., Citation2019; European Commission, Citation2021; Patrão et al., Citation2020; Sharifi, Citation2019). At some points, scholars and stakeholders started to identify and address the importance of people, as the human is the basic unit of a city (Cavada et al., Citation2014; Govada et al., Citation2016). Therefore, this wider point of view places citizens, quality of life and human value in the smart city concept, in addition to pure technology.

The concept remains a contested one, however and there is still no general agreement and standard definition of the term “smart city” (Albino et al., Citation2015; Camero & Alba, Citation2019; Caragliu et al., Citation2011; Cocchia, Citation2014; Patrão et al., Citation2020; Sharifi, Citation2019, Citation2020). The main aim of the article is to reconstitute chains of meaning in relation to the Smart City, one of the most in vogue yet ambivalent concepts in urban studies (Lai & Cole, Citation2023). It proposes a framework of analysis as a heuristic tool to interpret narratives in general and those of Smart City Hong Kong in particular.

The article consists in an in-depth interpretative study of the Smart City. Taking Hong Kong as the central reference point, it evaluates the utility of technology, sustainability, and e-governance as public narratives. The article explores the contexts in which the urban narratives emerge, the actors or coalitions of actors sustaining specific narratives, the potential tensions that urban narratives may generate, and whether there is room for alternative narratives and in what contexts. The main objectives are academic, and practitioner focussed. In terms of academic inquiry, the article engages in a case specific, multiple methods enquiry into Smart City Hong Kong. It draws on a multi-disciplinary project that encompasses close academic disciplines (political science, geography, area studies) and uses multiple methods, each of which has a distinct logic: a public opinion survey, contextual interviews, and focus groups. This article presents the case study-based, qualitative dimension of a project that also incorporates a variable-focussed, index-based approach (Lai & Cole, Citation2023). The two approaches thereby meet the demand of Windelband and Oakes (Citation1980) to bridge idiographic (case study intensive) and nomothetic (variable focussed) approaches in social scientific inquiry. The article also draws lessons from and for practitioners. From stakeholders, the article captures primary evidence at a cardinal moment in recent history of Hong Kong; the researchers are grateful to all the participants. For stakeholders, our findings suggest that public narratives need to be exercised with great caution. A proud record in the field of digital services does not automatically transform itself into a convincing public message. Specific messages ought to be tailored towards those social groups (the younger, most educated, and liberal-minded) whose cooperation is required for making Smart City an inclusive experience.

Why the case study of Hong Kong? The Asian metropolis, consistently ranked as one of the world’s leading smart cities, is undergoing a period of disruptive change, as Hong Kong is increasingly integrated into the political (Liaison Office) and economic (Greater Bay Area) logics of mainland China. Fieldwork for this article took place during 2020–21, at a specific point in the recent history of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), namely that of the transition between the hybrid One Country Two Systems arrangement and the emergency politics of the post-National Security Act era (July 2020-). We guide the reader to the dense published literature on the events on 2019–2020 (Chung, Citation2020; Esposito et al., Citation2021; Ho & Tran, Citation2019; Jones, Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2020). In general, interlocutors were very unwilling to engage with ideas of Hong Kong’s past, present and future in the context of the events—the 2019 movement against the extradition bill, the 2020 National Security Law- that provided the backdrop of our empirical data collection. The subject matter—Smart City- might appear as peripheral by comparison to these epochal shifts. But it is central to the claim that the HKSAR administration has had a distinctive legitimacy throughout its short history, a claim restated during the 2019–2020 events. Smart City thereby serves as a constant through which to judge the pertinence of technology, sustainability and digital governance as narratives that inform public policy.

In their work on validity in qualitative research, Adcock and Collier (Citation2001, p. 541) acknowledge that qualitative researchers ultimately rely on using their “knowledge of cases to assess alternative explanations”. The case is that of Smart City Hong Kong. Section one considers how best to operationalize narratives and presents the main methods employed. Section two presents three competing narratives of Smart City Hong Kong, drawn inductively from qualitative data analysis of the interviews, and presents the main actor-based networks. Section three drills down deeper into the interviews with a view to contrasting official public narratives and face to face semi structured interviews and focus groups and unveiling unspoken truths. The article concludes by evaluating the persuasiveness of various types of narratives of the Smart City to convince, influence and act as internally consistent heuristics that guide public action.

2. Operationalizing narratives

Terms such as storytelling, narrative and discourse are sometimes used interchangeably, creating a degree of conceptual confusion. It is not necessary to buy into the whole of post-structural discourse analysis to use narrative as a useful middle-level tool for understanding. According to Patterson and Renwick Monroe (Citation1998) a narrative “is essentially a story, a term more often associated with fiction than with political science”. Somers and Gibson (Citation1994) provide a useful taxonomy, in some sense reminiscent of the levels of analysis debate in social science. Ontological (or personal) narratives are individual stories, shaped socially, but that help us make sense of who we are. Public narratives are stories that belong to institutions or social formations. Conceptual narratives concern the intellectual constructs used to make sense of narratives by academic researchers. These are necessarily historical and contingent in nature. Meta-narratives are narratives of narratives. The grand narratives of our time contain “epic dualities” (the Republic against Religion in France, for example). They are abstract and universal.

Our principal concern here is with public narratives, those at the crossing point between personal and institutional experience. We use the general framework proposed by Somers and Gibson (Citation1994) to comprehend public narratives; in assessing whether there is a convincing relationship of parts, whether the causal plot is intelligible and convincing, whether there is selective appropriation of events and the importance given to time, sequence and place.

This requires further elaboration. In terms of the relationship of parts, Bruner (Citation1990, p. 35) argues that narratives are a principle through which “people organize their experience in, knowledge about, and transactions with the social world”. Events acquire meaning through their connection to other events in a timeline through a theme (Polkinghorne, Citation1988). This key theme is the plot, where the end often explains the logical connections between episodes. Hence, causal emplotment is the second dimension. Narrative can take the form of single actions, but it moves through time and constructs meaningful totalities out of scattered events (Portas, Citation2011). Narratives also exhibit other specific elements, chiefly causal claims. The third dimension is selective appropriation of events. Stories do not simply mirror reality but “involve selectivity, rearranging of elements, redescription and simplification” (Hinchman & Hinchman, Citation2001), in short, a story line. Finally, there is time, sequence and place. From Aristotle onwards, narratives are a “whole” which has a beginning, middle and an end (as cited in Portas, Citation2011, p. 13) and which comprises accounts of events that are chronologically connected.

There is only a limited number of sources aiming attention at the smart city narratives (Esposito et al., Citation2021; Struver & Bauriedl, Citation2020). Taking a cue from Healy and Morel-Journel (Citation2018) we address three subsidiary questions that are common to Hong Kong and to other cities. First, in which contexts do urban narratives emerge? Second, who are the actors or coalitions of actors sustaining specific narratives? Third, what are the potential tensions that urban narratives may generate? Is there room for alternative narratives and in what contexts? We refer to these questions throughout the article and return to them in the conclusion. The ensuing article draws on a territory-wide survey (n. 808, administered by Public Opinion Research Institute [PORI] in March-April 2021), a purposive interview sample (n.25, see Table ) and four specially convened focus groups, each lasting for around one hour.

Table 1. The dimensions of narratives

3. The methodological framework of analysis

The framework of analysis is proposed as a heuristic tool to interpret narratives in general and those of Smart City Hong Kong in particular. The research design is inductive and interpretative, rather than deductive and correlational (Durnová & Weible, Citation2020, p. 578). The proposed framework consists of three (qualitative) indicators, whereby the capacity of a narrative to confer meaning depends (in equal measure) on its originality, its sincerity, and its extension.

The first dimension is that of originality, conceived in terms of the degree of endogeneity of the narrative. How might the origins of the narrative be process traced? Is it obviously borrowed from elsewhere or endogenously constructed? Originality is assessed using process tracing via interviews with key actors drawn from a balanced purposive sample. We attribute scores to the sub-fields in terms of the following criteria: high refers to a distinctive, endogenous narrative; medium to a mixed, hybrid narrative, drawn from diverse sources, while low describes a narrative that is fundamentally imported from cross-national circulations. The scores are generated for this paper, building on previous work conducted by the lead author (Cole et al., Citation2021).

The second dimension is that of sincerity, which describes the internal consistency of the narrative, according to multiple accounts (stakeholders, collective interviews, surveys). We attribute scores to the sub-fields in terms of the following criteria: high indicates a clear concordance between accounts of stakeholders [official statements, face to face interviews, focus groups]; medium signifies mixed concordance between accounts, while low points to the existence of rival discursive coalitions around the domain. Does it provide a convincing and sincere account for the social phenomena it purports to describe? Sincerity includes, but goes beyond, internal validity (Carmines & Zeller, Citation1979) and involves researcher judgement on whether the “referent object” (i.e. the Smart City) describes the dynamics actually taking place.

The third dimension is that of extension, which measures the influence of the narrative beyond the narrow confines of the policy community. The principal question centres on whether the narrative has a large echo in public opinion or amongst selected audiences? We score high, when there is a clear resonance in public opinion (Hartley, Citation2021); medium, where there is mixed evidence for the sub-field in public acceptability (PORI survey, 2021); and low where there is little support for tenets of narrative (sub-field and overall) in public opinion [PORI survey, 2021]). Table develops these dimensions.

Table 2. Conducted interviews summary

In addition to the purposive interview sample upon which the core of this paper’s analysis is based, a territory wide survey and four focus groups were an important part of the data collection, and they facilitated the scoring of narratives (the purpose of this article). The main findings of the survey, conducted by PORI in Hong Kong between 24 March and 16 April 2021, are now presented, while the focus group analysis is treated in the narratives as narratives section. The target population of the survey was that of Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong citizens of age 18 or above. Data was collected by polling a random sample of 808 respondents. The main findings of the survey, developed extensively elsewhere (Cole & Tran, Citation2022), can be summarised in three core results. First, that of the data trust paradox: there is high support for technology in a low trust environment. For 62% of survey respondents (28% undecided and 10% opposed), technologies “produced more benefit than harm”. Most Hong Kong residents are enthusiastic towards technology, yet most respondents expressed concerns about the uses the government might make of data and the vast majority (88%) considered that everyone should have the right to protect their personal privacy. Second, the findings related to the social impact of trust and the smart city. There was a strong correlation between support for the government and the development of Hong Kong as a Smart City, a position most prevalent amongst the older age cohorts, those born in the mainland and those with the least education (Lai & Cole, Citation2022). On the other hand, the most dissatisfied Hong Kong citizens were those between 18 and 29 years old, those holding a bachelor or postgraduate degree and those who politically identified themselves as localists. The social impact of the trust-mistrust nexus was explained in part by the politically charged situation of 2019–2020.

Third, it emerges from these factors that Smart City has difficulty in embodying what it sets out to describe. Our survey laid bare the challenges facing government policy: 41% of the interviewees did not understand the Smart City Blueprint, though they were more in favour of its component dimensions, such as mobility, living, people and the environment.

This challenge for a technical public discourse is explored in the main body of the article. We engage mainly in the meso-level analysis that underpins public narratives (capturing representations that mix personal experience and institutional location). Consistent with the public narrative approach, the accounts presented are those of former government officials, elected representatives of local authorities, but also of economic stakeholders, community leaders and more informal groups. They aim at telling a story about the city, its identity, its history, its development path, and future prospects. The “story” is principally collected from a purposive sample interviewed between July 2020 and December 2021, summarized in Table . The main types of types of actors included: governmental actors (former ministers, civil servants), smart city practitioners and urban providers; district councillors (including those associated with the opposition parties), local and foreign business actors involved in service delivery, and civic associations, especially in the field of sustainability. Each respondent was treated in the strictest confidence, in line with the ethical approval granted by the organisation. The framework of analysis also draws on the four focus groups (as a measure of sincerity) and the mass survey (to validate the extension of narratives).

3.1. Narratives of the Smart City: drilling down using Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis (CAQDAS)

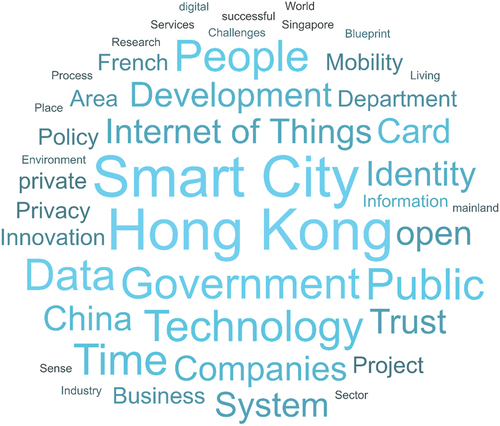

The lexical exercise initially involved drilling down into the content of the 25 interviews, each of which was fully transcribed and input into the NVivo software programme. In Figure , a word cloud provides a visual representation of the 50 most frequently enunciated words with at least four letters (once the process of elimination of prepositions and transitions has taken place). The larger the word appears, the more times it was cited in the interviews. Moving from visual representation to linking relationships between words, the cluster analysis feature of NVivo then allowed us to re-group the core themes in the interviews and interpret the relationships between them (using Pearson correlations). What are labelled as “couplings” are Pearson correlations between words in the cluster, as determined by the software. “Interpretation” refers to the interpretative tradition that inspires this article, whereby the researchers perform a key role in synthesising meaning. Researchers A and B were present at most interviews, and each reviewed the themes prompted by NVivo. Researchers C and D, who were not present at most interviews, similarly reviewed the overall themes. Figure presents the word cloud from 25 interviews carried out between July 2020 and December 2021, while Table presents a thematic cluster analysis.

Table 3. A thematic overview of the interviews, 2020–2021

The five lexical clusters themes emerging from the qualitative interviews were regrouped into three main interpretative frames for the purposes of mixed analysis, each derived from the polycentric concept of Smart City: Smart Public Services (Technological City), Smart Environment (Sustainable City), Smart Government (Hong Kong Governance). The fourth and fifth cluster referred very specifically to precise policies—Hong Kong identity card and waste management—and are hence excluded from this analysis. The next section now considers the three main frames emerging from the cluster analysis, as representing a largely inductive entry into the narrative.

4. Plural narratives of Smart City Hong Kong

The research inquiry centres on the interplay between three interpretations of Smart City in the specific case of Hong Kong. Standard definitions usually frame the Smart City as primarily technological. A lexical overview of the 25 interviews also points to the Smart Sustainable City as being an alternative framing to the technology focused one. Smart versus Sustainable reflects well the broader international debates over the Smart City (C. Chan, Citation2018; Govada et al., Citation2016; Sharifi, Citation2020). Smart Government refers principally to the world-wide movement towards e-government (Banerjee et al., Citation2015; Criado & Gil-Garcia, Citation2019; Manoharan et al., Citation2020). We deduce that Smart City is an essentially contested concept, open to contrasting interpretations, epistemological underpinnings, and methodologies.

4.1. Framing Hong Kong’s Smart City as a technological city

In Table , SMART emerged as one of the central clusters. The first word cluster refers to Smart City in terms of Innovation and Technology centred public services. A belief in technology comes as close as any other to representing a consistent story or overview of the history of Hong Kong. There has been an embrace of digitalization as a governmental project since the inception of the Special Administrative Region. The history of the smart city development case in Hong Kong can be traced back to the initial Digital 21 Strategy of 1998 (Holliday & Kwok, Citation2004). The Hong Kong Government is regularly the recipient of awards for the best practice of Government to Business (G2B) services, including the Electronic Service Delivery Scheme (ESD), which provides 38 different public services through eleven governmental agencies (Palvia & Sharma, Citation2007).

The first frame is captured by the “tech goggles” metaphor used by Green (Citation2019). Tech goggles cause their devotees to perceive complex, normative, and deeply political decisions as able to be reduced to objective, technical solutions. Smart city idealists describe cities as abstract technical processes that can be optimized using sensors, data, and algorithms. The Big Data variant of the Smart City emphasizes smart governance by implementing sensors for data collection to manage society and improve city services (Cavada et al., Citation2014; Grenslitt, Citation2021). In terms of official Hong Kong government policy, Smart City is presented in terms of technological prowess and promoted as an exercise of city branding.

To return to the first of our three organizing questions: in which contexts do urban narratives emerge? What are their salient features and aims? Hong Kong’s reputation in the field of employing technology is well-established. But this must not be equated with innovation and originality in terms of the technologies employed. In line with the primary first-hand evidence data gathering approach adopted here, we propose the following account from an insider (HK10):

If we go back a number of years to the first Smart City plan. It was written by Price Waterhouse Coopers – this is an ongoing habit of the Hong Kong administration. They don’t do it in house. Now, when you’re not doing it in house, you are not starting the process by going into different parts of the government. You’re contracting that whole process to a consultant. It’s a highly compromised document that does not really have a vision.

In short, the Hong Kong Smart City blueprint was drawn up by external consulting agencies. The “narrative” was not endogenous but derived from the circular international concept of the Smart City, itself mediated by the audit firm PWC. Aligning with international practice has many advantages as a strategy; in terms of narrative, it can also have drawbacks as it can be insincere and does not necessarily provide a genuine benchmark to judge its performance.

4.2. Framing Hong Kong’s Smart City as a sustainable city

SUSTAINABLE appears as the second cluster in the NVivo word analysis. There are clear sustainability issues for Hong Kong (Marsal-Llacuna, Citation2016). Hong Kong is a compact city, where a dense population lives in cramped housing conditions. It faces the challenges of urbanism and climate change as would any other coastal city, though, as one respondent remarked “honestly climate change is not an understandable topic for the Hong Kong citizens yet” (HK20). This lack of public awareness is most probably due to the prevailing attention to other problems as amplified by both local and mainland media.

The Smart and Sustainable variety of the Smart city has a distinct European and north American flavour, associated with cities such as Brussels in Belgium (Huré, Citation2016); Lyon in France (Odountan, Citation2021) or Boston in the US (Agbali et al., Citation2017). Such cities emphasize the smart environment by implementing technologies for ecological energy usage and encouraging smart and sustainable forms of mobility (by municipal e-bikes, for example). In Hong Kong, there were certainly some examples of good practice linking the environment and technology provided in interviews, as well as in the literature. One historic example was the website for the environmental impact assessment ordinance (EIAO) by the Environmental Protection Department (EPD). An interactive map of Hong Kong was introduced on the website for the information of designated projects, allowing the community to submit their comments (Sinclair et al., Citation2016). The smart dimension of environment policy has been coupled with other initiatives: such as the desire to better manage waste collection by improving traceability or to reduce pollution by introducing smart metering in factories.

In relation to the Smart and Sustainable city, the government information office, OGCIO, emphasized the environmentally sustainable ambition of the HKSAR government. It highlighted the government’s record in installing Light Emitting Diode (LED) lamps in public lighting systems, for example, as well as its use of building-based smart information technology and its record on renovating ageing buildings to make them fit to cope with climate change. From the critical perspective articulated in several interviews (HK17, HK10, HK19, HK20), these minimal positions did not address the core question of lessening mass consumption, the real problem in Hong Kong. Moreover, there were several examples of a perceived misfit between public declarations and actions, producing the sentiment of insincerity, or at least of making inconsistent and unsubstantiated engagements. The government identified the need to renovate disused districts (such as the East Kowloon Central Business District) for the smart city strategy, for example, but the planned Northern Metropolis Smart City would be constructed on previously unbuilt land. The field of climate control was a good example of misfit: the HKSAR government has authored ambitious foresight documents such as the Hong Kong Climate Action Plan 2030 and set out the objective of carbon neutrality by 2050, but there is little detail on how these will be implemented.

On balance, however, interviewees were divided on the link between Smart and Sustainability. In the opinion of one interviewee (HK19): “ICT has not been smartly and massively used to green the buildings, energy or urban planning. Buildings with poor insulation also create more burden on energy usage”, while for one environment activist (HK20): “The smart only refers to tools and technology, whereas we speak of a sustainable city”. Another interviewee in the powerful Hong King financial sector (HK18) downplayed the importance of sustainable finance (ESG), a phenomenon that is “more understood in Europe and North America”, but which was gaining some traction because of “the financial power and of the markets in the US”. These citations all strengthen the view that official discourse bordered on simple greenwashing.

4.3. Framing Hong Kong’s Smart City in terms of smart government or e- governance

There is a bewildering “noise” around e-government and e-governance. Best practices have been declared, performance indexes proposed (Palvia & Sharma, Citation2007), government websites evaluated in terms of their transparency (Manoharan et al., Citation2020) and lists of e-governance competencies advocated (Banerjee et al., Citation2015). The HKSAR government boasted a solid reputation in e. government, acknowledged in several interviews. The HKSAR government’s “open data policy” was announced in October 2018. By end-July 2020, the PSI Portal “contained about 4.180 different datasets, including the real time data from franchised bus companies and the Metropolitan Light Railway (MTR), and provided around 1.390 application programming interfaces (APIs)” (HK13). Moreover, a Smart Government Innovation Lab was established in April 2019 to encourage and assist government departments in adopting various information technology (IT) solutions to improve public services. The Next Generation Government Cloud Platform and Big Data Analytics Platform were launched in September 2020. Above all, the “iAM Smart” one-stop digital service platform was launched in the fourth quarter of 2020, enabling the public to conduct authentication and transactions online with a single digital identity. Other dimensions of e-government included the new e-ID card and the e-Health Records service.

In the case of Hong Kong, the balance of the interviews was that such initiatives fell short in terms of improving the relationships between the citizens and the state, with implications for governance processes. Though generally favourable to technology, public opinion was divided in relation to applications of technology that involve public authorities. Opinion was deeply split on whether to use the Leave-Home-Safe app, developed by the Hong Kong government as part of the anti-Covid-19 tracing process. There was a more widely diffused sense of opposition to government collecting personal data (much more so than in the case of private companies). In the survey statements about privacy, there was strong opposition to the idea that the government might collect personal data, even to improve public services (just under 44% did not welcome the government collecting personal data even to improve its services).

The literature review undertaken by Manoharan et al. (Citation2020) concluded that e-government refers narrowly to “public functions and institutions that have become digitized”, while e-governance “refers to the digitalization of all the relationships, and the governmental and non-governmental factors that contribute to the services and policy-making functions of public institutions”. Though e-government in Hong Kong might be adopted as an efficiency-enhancing tool for accomplishing defined purposes, the HKSAR’s strong ICT infrastructure and technological capacity has not produced an e-governance transformation, at least not in terms defined above.

Having established the existence of three types of Smart City narrative, the second part of the article now drills down further into these narratives, understood both as actor-based networks, and forms of public communication.

5. Narratives as narratives and their uneven capacity for diffusion

The three varieties of Smart City narrative are linked to distinct actors and interests. Smart public services in general were the site of rivalries and a lack of communication between governmental bureaus, a common feature of complex organizations (Peters, Citation2018). But this was not just an account of bureaucratic politics; in each field, interviews uncovered evidence of close working relations between government bureau and specific think tanks and enterprises. The dominant actors, in each of the surveyed domains, consisted of formal government agencies, supported by sympathetic think tanks, some companies and the chambers of commerce. Urban coalitions were unable to express themselves totally openly and tensions over the delivery of types of public service were dwarfed by existential questions (C.-K. Chan, Citation2022) of the nature of the regime. Of course, there was a recognizable alternative coalition, in the form of the democratic forces which won 21 out of 22 District Councils in the local elections of December 2019, at the height of the anti-ELAB movement and its aftermath.

It is important not to reduce narratives to being a simple reflection of interests. Beyond their instrumental nature (what is the dominant actor, coalition, or actor-system behind the narrative), taking narratives seriously requires conjecture on their capacity to rise above the principals (identified as producers of meaning) and to extend their scope of persuasion. Even more than forming part of actor-based strategies, public narratives are a form of communication, a justification of official government policy. They are an extension of public acts and persuasion, and they ought to be judged on this basis.

The capacity of a narrative to confer meaning draws upon three criteria: its originality (degree of endogeneity); its sincerity (internal validity and trustworthiness), and its extension (its ability to provide a convincing account to the outside world for social phenomena). These three criteria form the core of the interpretative framework we propose. They are also affected by the form of diffusion and communication. Four types of account emerged from our empirical investigation: written responses from official agencies; face to face interviews; confidential discussions, and collective interviews in focus groups. The substantive message conveyed differed as much by the form, as by the (interest) of the interviewees.

5.1. Putting the best foot forward: official interviews

Official HKSAR government accounts came closest to the “tech goggles” approach and usually centred on the flagship policy, the Smart City Blueprint. Government spokespersons rarely deviated from the line expressed formally in the Smart City Blueprint, an umbrella for diverse policy programmes mobilizing distinct sets of interests and actors. Contact with government agencies took the form of formal written communications. In one such written communication, a full justification was given by the Office of the Government Chief Information Officer (OGCIO), the government communication agency, which robustly defended the key traits of the Blueprint. In the domain of Smart Mobility, for example, the “HKeMobility” mobile application was presented as an efficient technical tool for improving traffic flows. The other digital public services were mostly regrouped under Smart Living, inter alia the provision of free public Wi-Fi hotspots under the “Wi-Fi.HK” brand. In terms of Smart Economy, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority launched the multi-bank blockchain project of a trade finance platform “eTradeConnect” in September 2018, with the task of digitizing trade documents and automating trade finance processes. For its part, Smart people was mainly defined in terms of introducing a fast-track arrangement for admitting overseas and Mainland technology talents to undertake research and development (R&D) work in Hong Kong (the TechTAS scheme) and in promoting STEM subjects in schools. Government actors also proffered formal justifications in the fields of Smart Sustainable City and Smart Government.

These examples were those of a confident public communication. Or were they? Members of our panel were given to doubt. In the view of one interviewee, Smart City is a hollow narrative, both in its own terms of reference and because of the way it has been presented by the HKSAR government:

The whole point about publishing the smart cities and other policy papers is so that it can tell you what the government thinking is. Why is it doing what it’s going to do? These are policy or political papers. They are not the technical papers. These are documents where they want to carry the community along. I think the government is not good at that. (HK10)

The capacity for effective diffusion of such a narrative is limited. It is weak in terms of its extension, or its capability to convince, as judged by the PORI survey. There was little comprehension of the concept of the Smart City as defined in the HKSAR Blueprint. In our survey, we asked the question: overall speaking, how well do you understand the contents of this Smart City Blueprint? Fully 41% of the sample did not understand the question at all, and only 8% ventured a positive answer (PORI, 2021).

5.2. Confronting complex realities in face-to-face interviews

Face to face interviews were held with a majority of interviewees; as might be expected from the panel selection (involving a purposive sample containing plural elements), far greater diversity was expressed than in official governmental accounts.

First, there were far more critical accounts of the Smart City Blueprint. For one interviewee (HK17): “The narrative is overwhelmingly tech-driven, but we do not reflect on the meaning of technology, in context of all this smart city development”. This interviewee articulated well the consensus from interviews, centred on the weakness or absence of a coherent technical narrative. Most external regards were critical. For Interview HK20, for example, the Smart City was purely focused on the “technical and technological dimensions, such as the gadgets, or the installation of the latest technologies”. Representative of the sample was interviewee 15: “There seems to be relatively little cohesiveness among these different actions, it’s not very clear to me. All the IoT, big data, AI, 5 G, are on the table”. Interestingly, even the focus on STEM was criticized by one interviewee, who contrasted the technological smart city with art tech: “Art Tech could almost like be a STEAM engine for Hong Kong. STEAM, S-T-E-A-M (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics) against just STEM. We cannot have just talents that are all STEM-oriented” (HK17). Such narrative qualities—and those of digital storytelling in particular—are essential soft skills that could support this creative digital economy.

Interviewees were divided on the link between Smart and Sustainability. The smart dimension of environment policy has been coupled with other initiatives: such as the desire to better manage waste collection by improving traceability or to reduce pollution by introducing smart metering in factories. But Interview HK20 considered these efforts to be inefficient and used the plastic waste issue as an example. Ambitious policies adopted elsewhere, like waste-charging, were floated to control consumption-based emission: but they could not overcome the resistance of entrenched political and economic interests. To paraphrase one interviewee (HK05) one powerful alternative framing was that Hong Kong had developed as a free port: traders conduct business with the outside world and free trade must be remain, and in this perspective all taxation is bad, including any new environmental tax.

The Smart and Sustainable city in Hong Kong? Several interviewees offered the view that mainland China, and especially Shenzhen, was way ahead of Hong Kong in terms of smart, sustainable management. The small size of the territory also raised logistical problems: one interviewee (HK04) declared that it made no sense to develop a waste management facility in Hong Kong, as it is a small territory, with a limited population. This area was one where collaboration was needed across the Greater Bay area.

5.3. Collective interviews: testing sincerity in focus groups

These three narratives of the Smart City also circulated in the bespoke collective interviews (focus groups) we organized as part of the data collection in December 2021. Four specially convened focus groups, each lasting for around one hour, accompanied the survey and purposive interview sample. Group 1 (10 participants) consisted of young (18–25-years old) Chinese students; Group 2 (25–37 years old) was a mixed group, also with 10 participants; Group 3 consisted of 11 civil servants and public officials, while Group 4 encompassed 11 participants working for private companies. The focus group vignette closely matched the territory-wide survey (n. 808) and the interview schedule (n. 25) questions. There were many commonalities across all four groups. In terms of the three narratives, smart was understood first in terms of technology, second as mode of government and only third in terms of environmental quality. sets out the responses to the moderator’s question “what do you understand the smart city to be”

Table 4. Definitions of the Smart City

Smart as technology was the main reference for all four groups. Definitions of smart city centered on aspects of Smart technology, such as e. payment, Internet of Things, Smart ID card, one stop public services and police surveillance cameras. Smart as sustainable also had some currency. Smart City was even described as an “environmentally friendly” process by one participant. Rather like the main interview sample, the link between technology and the environment seemed distant, however, except for specific products such as e-vehicles and green energy. In relation to smart government, sophisticated responses raised the prospect of Artificial Intelligence allocating resources, self-governing robotics and cities ruled by algorithms.

There were also substantial differences of appreciation between the four groups, in relation to risks and benefits of the Smart City, trust in providers and data processes and comparisons with mainland China. In terms of risks and benefits of the Smart City, across all four groups the principal benefits of the Smart City were identified as efficiency and convenience. For some in the groups, the risks outweighed the benefits, especially amongst the Hong Kong citizens. There was a marked distinction between most mainland Chinese respondents, who emphasized convenience, security and safety, and the Hong Kong centric group, which raised dangers with facial recognition, mistrust of government, the digital divide (the exclusion of older generations from some public services), and the long-term consequences of non-human decisions being made by digital systems. There were also important contrasts between the public administration and private sector groups in relation to the respective roles of government and business as trustworthy service providers and custodians of data.

6. Discussion: comparing narratives

The article concludes with a comparison of the three main smart city frames according to the framework developed above. To recall, we use the general framework proposed by Somers and Gibson (Citation1994) as a heuristic to evaluate public narratives; in assessing whether there is a convincing relationship of parts, whether the causal plot is legible and convincing, whether there is selective appropriation of events and the importance given to time, sequence and place. Our more precise framework is formulated in terms of originality, sincerity, and extension. These three domains were assessed according to their quality as public narratives and their link with action.

Let us present each one in more detail. First, considering Smart Public services as an urban narrative, in terms of the Somers and Gibson (Citation1994) framework, there was a relationship of parts – of sorts. Smart public services produced a formal narrative presenting technological progress as a teleological, largely non-reflexive process. This narrative was promoted by certain types of actors; mainly by the trans-departmental actors within the machinery of State (OGCIO, the Environment Protection Bureau [EPB], the Information and Technology Bureau [ITB], the Smart City Bureau [SCB]).

Our first finding is that technology indeed lies at the heart of the Smart City, in its Hong Kong version, at least. Such a conclusion was validated in the focus groups, the survey, and the interviews. Hong Kong appears closer to the Big Data variant of the Smart City than the Smart and Sustainable one identified in European or North American cities (Lai & Cole, Citation2023). While the focus groups identified technology as the driving force underpinning the Smart City, the survey findings demonstrated how difficult it is to construct any narrative (in the form of a legitimizing discourse) given the degree of miscomprehension of citizens (just 9,60% understood the contents of the Smart City Blueprint). The consensus from the interviews was that of the absence of a genuinely joined-up narrative and a circular model of importing best practices from elsewhere. As a result, the causal emplotment is rather weak. There is no clear causality beyond the general belief in technological progress. In terms of selective appropriation, there is an equivalence between technology and benefits; the belief is a general one, rather than detailed defence of the 130 indicators that comprise the Smart City Blueprint as a whole. Finally, in relation to time, sequence, and place: the temporal dimension is one of technological progress, marked by the roll out of specific initiatives and programs. The sequence is defined in terms of successive iterations of the Smart City blueprint. The place is Hong Kong—but in this first narrative, it could be almost any large metropolis around the world (Lopes et al., Citation2019). Hence, in terms of evaluating narrative as narrative, we award the score of low-medium for originality, low-medium for sincerity and medium for extension. It is difficult to sustain smart public services as a unified public narrative.

Moving on to Smart and Sustainable as an urban narrative (and taking the framework proposed by Somers and Gibson (Citation1994), is there a relationship of parts? The linkage between technology and the environment is less centrally asserted than in the first example, a fact observed in interviews and focus groups (alongside mixed evidence from the survey). The weaker link with technology is reflected in the diversity of actors involved: firms, NGOs, specific governmental bureau, think tanks. The narrative is less centred on actors within the machinery of State; private firms and public private partnerships also perform a more important role. There is a stronger sense of emplotment, with clearer stories centred on causal narratives and on micro-level cases that link sustainability, creativity, and smartness. There is also a form of selective appropriation: mainly framing sustainability in terms of the environmental dimension, and only sometimes associating this with the digital element. Interestingly, in the NVivo dataset, environment and digital are not closely correlated. In terms of time, sequence, and place, finally, time is that of threatened environmental decline; the sequence is one of problems and solutions and the place concerns specific districts in Hong Kong, or spaces within Hong Kong (for example, the national parks), as well as walking paths and land reclamation throughout the territory. When evaluating the narrative as narrative, there is a better fit between the sustainability narrative and the place specific case of Hong Kong, with the challenges it faces. Hence, we award the score of medium for originality, medium-high for sincerity and medium-high for extension. There is a less solid link to Smart City, however, making the latter less capable of drawing on the attraction of sustainability to mobilize support for digital city.

Finally, on Smart Government as an urban narrative, to return to the analytical frames introduced by Somers and Gibson (Citation1994), there appeared to be a weak relationship of parts, pointing to a fractured public administration that is not joined-up in any key sense. There was also a frail sense of causal emplotment; identifying convincing causal narratives is problematic when there are “multiple audiences to satisfy”: the “local audience, mainland China and the international business community” (HK10). As far as selective appropriation of events is concerned, we observed an institutional void, part of a broader crisis linked to the transition from an old world (One country two systems) to a new one (the accelerated integration of Hong Kong into mainland China). Likewise, in terms of time, sequence and place, there was no very clear focus that could be tied into a convincing forward looking narrative: interlocutors were very unwilling to engage with ideas of Hong Kong’s past, present and future. That the HKSAR government pushed ahead with the revised edition of the Smart City blueprint (in December 2020) was interesting not only for what it revealed (business as usual), but also for the noise it created to occupy the public space during a period of high controversy in the surrounding political environment. Hence, evaluating narrative as narrative, we attribute low-medium for originality, medium for extension and medium for sincerity. Smart government was neither convincing as a narrative, nor did it maintain a very solid link—in focus groups, interviews, and the survey- to the Smart City (See Table ).

Rising up the ladder of abstraction, the three narratives were held with varying intensity and demonstrated a variable capacity for extension beyond the case of Hong Kong (Table ). Judging the narratives as narratives, how persuasive are the various types of narratives of the Smart City to convince, influence and act as internally consistent heuristics that guide public action? In terms of internal validity, Smart City is interpreted more in terms of technology (in the focus groups, interviews, and survey) than sustainability or e-governance. But the link is blurred and somewhat contradictory. Smart City sustains itself on the technology narrative—but Smart City as technology is caught in the crossfires of broader questions of trust in government, and it is here that the actor system takes on all its significance.

Table 5. The Continuum of Smart City narratives

The diffuse distrust of the Hong Kong government was clear and confirmed in our survey findings (see also Hartley, Citation2021). In the words of one interviewee: “People do not always trust the government, to be honest, so that makes the thing really worse”, a sentiment shared in several interviews. There appear to be no striking differences in the survey questions (on trust and the smart city) according to gender, professional occupation, income, religious belief, or locality, though age, place or birth and political loyalty did appear to be significant indicators in some respects. The opposition of the most joined-up, tech savvy elements of the population to key dimensions of the Smart City programme revealed a deeper problem of trust. In part, this expressed a mistrust of government in the aftermath of the 2019–2020 protests. The view was supported in the survey by the widespread opposition to government collecting personal data, even to improve its own public services. There were suspicions about the uses the government might make of data. In survey and interviews, opinion was particularly divided in relation to applications of technology that involve public authorities (especially the anti-Covid LeaveHomeSafe app, as well as the programme of Smart Lampposts).

7. Conclusion

The article has proposed a novel framework of analysis to interpret narratives in general and those of Smart City Hong Kong in particular. The capacity of a narrative to confer meaning is calibrated by its originality (degree of endogeneity); its sincerity (internal validity and trustworthiness), and its extension (its ability to provide a convincing account to the outside world for social phenomena). We observe the paradox that the most coherent narrative in its own terms of reference (sustainability) has the most distant relationship to the Smart City; that the technological narrative is deemed as hollow and non-heuristic by many actors interviewed; that Smart Government is considered in more general terms of trust and mistrust in government, rather than performance enhancing digital programmes. Taken as a whole, Smart City appears as a rather hollow narrative, an empty signifier, a general term lacking clear meaning.

The study focuses mainly on one set of interviews carried out at a specific period in recent history. Its strength lies the richness of drilling down into primary accounts, which is germane to the exercise of narrative analysis. Its limitations are both temporal (it captures meaning at a specific, politically charged period of history) and dimensional (it presents the case study-based, qualitative dimension of a project that also incorporates a variable-focussed, index-based approach [Lai & Cole,Citation2023]). Combining these two approaches (cases and variables) more systematically, in a mixed method design, would respond to the demand of Windelband and Oakes (Citation1980) to bridge idiographic (case study intensive) and nomothetic (variable focussed) approaches in social scientific inquiry. Such is a valid general ambition of social scientific research, though the interpretative approach is best served by following the recommendations we present here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alistair Cole

Alistair Cole is Head of the Department of Government and International Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University. He has published extensively, mainly in the field of French, British, and European politics. His publications are widely cited (with an H Index of 34 according to Google Scholar).

Dionysios Stivas is a Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Department of Government and International Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong. Pieces of his work appear in the Mediterranean Politics, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, and Journal of Risk and Financial Management.

Emilie Tran is Assistant Professor of Politics and Public Administration, in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Hong Kong Metropolitan University. Her research focuses on China’s relations with Europe, the Middle East and Africa, from two angles: the Chinese diaspora and health diplomacy.

Calvin Lai is a Research Associate at Technische Universität Darmstadt. His research interests cover Sustainable Urban Development with the background of Industrial Engineering and Product Design. Mr Lai is passionate about combining the sustainable perspective with smart city development in government and industry sectors.

References

- Adcock, R., & Collier, D. (2001). Measurement validity: A shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. American Political Science Review, 95(3), 529–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055401003100

- Agbali, M., Trillo, C., Fernando, T. P., & Arayici, Y. (2017). Creating smart and healthy cities by exploring the potentials of emerging technologies and social innovation for urban efficiency: Lessons from the innovative city of Boston. [University of Salford Institutional Repository]. http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/49898/

- Akande, A., Cabral, P., Gomes, P., & Casteleyn, S. (2019). The Lisbon ranking for smart sustainable cities in Europe. Sustainable Cities and Society, 44, 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.10.009

- Albino, V., Berardi, U., & Dangelico, R. (2015). Smart cities: Definitions, dimensions, performance, and initiatives. Journal of Urban Technology, 22(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2014.942092

- Banerjee, P., Ma, L., & Shroff, R. (2015). E-governance competence: A framework. Electronic Government, 11(3), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1504/EG.2015.070120

- Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Camero, A., & Alba, E. (2019). Smart City and information technology: A review. Cities, 93, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.014

- Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C., & Nijkamp, P. (2011). Smart Cities in Europe. Journal of Urban Technology, 18(2), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2011.601117

- Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage Research Methods. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985642

- Cavada, M., Hunt, D., & Rogers, C. (2014, November 1-30). Smart Cities: Contradicting definitions and unclear measures [Paper presentation]. 4th World Sustainability Forum, https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1756.5120

- Chan, C. (2018). Which city theme has the strongest local brand equity for Hong Kong: Green, creative or Smart City? Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 15(1), 12–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-018-0106-x

- Chan, C.-K. (2022). Shifting journalistic paradigm in post-2019 Hong Kong: The state–society relationship and the press. Chinese Journal of Communication, 15(3), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2022.2039256

- Chung, H.-F. (2020). Changing repertoires of contention in Hong Kong: A case study on the anti-extradition bill movement. China Perspectives, 2020(3), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.10476

- Cocchia, A. (2014). Smart and digital city: A systematic literature review. Smart City, 13–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06160-3_2

- Cole, A., Harguindéguy, J. B. P., Pasquier, R., Stafford, I., & de Visscher, C. (2021). Towards a territorial political capacity approach for studying European regions. Regional & Federal Studies, 31(2), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1548440

- Cole, A., & Tran, É. (2022). Trust and the Smart City: The Hong Kong Paradox. China Perspectives, 130(2022/3), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.14039

- Criado, J. I., & Gil-Garcia, J. R. (2019). Creating public value through smart technologies and strategies. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 32(5), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-07-2019-0178

- Durnová, A. P., & Weible, M. C. (2020). Tempest in a teapot? Toward new collaborations between mainstream policy process studies and interpretive policy studies. Policy Sciences, 53(3), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09387-y

- Esposito, G., Clement, J., Mora, L., & Crutzen, N. (2021). One size does not fit all: Framing smart city policy narratives within regional socio-economic contexts in Brussels and Wallonia. Cities, 118, 103329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103329

- European Commission. (2021). Smart cities. Retrieved May 12, 2023, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/eu-regional-and-urban-development/topics/cities-and-urban-development/city-initiatives/smart-cities_en

- Gibson, D., Kozmetsky, D., & Smilor, R. (1992). The Technopolis Phenomenon. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Govada, S., Spruijt, W., & Rodgers, T. (2016). Assessing Hong Kong as a Smart City. In T. M. V. Kumar (Ed.), Smart economy in Smart Cities (pp. 199–228). Springer.

- Green, B. (2019). The smart enough city: Putting technology in its place to reclaim our urban future. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11555.001.0001

- Grenslitt, J. (2021). Digital cities survey 2020 winners Aannounced. GovTech. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://www.govtech.com/dc/digital-cities/digital-cities-survey-2020-winners-announced.html

- Hartley, K. (2021). Public Trust and Political Legitimacy in the Smart City: A reckoning for technocracy. Science, Technology, & Human Values.

- Healy, A., & Morel-Journel, C. (2018, November 29-30). Urban narratives. (Re)building Cities Through Narratives – an Introduction [ Paper presentation]. Urban Narratives Conference, Lyon University.

- Hinchman, L. P., & Hinchman, S. K. (2001). Memory, identity, community. The idea of narrative in the human sciences. State University of New York Press.

- Holliday, I., & Kwok, R. (2004). Governance in the information age: Building E-Government in Hong Kong. New Media & Society, 6(4), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144804044334

- Ho, W. K., & Tran, E. (2019). Hong Kong–China Relations over Three Decades of Change: From apprehension to integration to clashes. China: An International Journal, 17(1), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1353/chn.2019.0009

- Huré, M. (2016). The metropolis and the market: Political rescaling through public-private bike-sharing policy in Brussels. In A. Cole & R. Payre (Eds.), Cities as political objects (pp. 218–240). Edward Elgar.

- Innovation and Technology Bureau. (2020). Smart City blueprint for Hong Kong (Blueprint 2.0). The Hong Kong Government. https://www.smartcity.gov.hk/modules/custom/custom_global_js_css/assets/files/

- Jones, M. (2020). The revolution of our times: Hong Kong’s history of protest and the 2019 protests. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 40(2), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2020.0033

- Lai, C. M. T., & Cole, A. (2022). Levels of public trust as the driver of citizens’ perceptions of Smart Cities: The case of Hong Kong. Procedia Computer Science, 207, 1919–1926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.09.250

- Lai, C. M. T., & Cole, A. (2023). Measuring progress of smart cities: Indexing the smart city indices. Urban governance, 3(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ugj.2022.11.004

- Lee, F. L. F., Tang, G. K. Y., Yuen, S., & Cheng, E. (2020). Five demands and (not quite) beyond: Claim making and ideology in Hong Kong’s anti-extradition bill movement. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 53(4), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1525/j.postcomstud.2020.53.4.22

- Lopes, K. M., Macadar, M. A., & Luciano, E. (2019). Key drivers for public value creation enhancing the adoption of electronic public services by citizens. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 32(5), 546–561. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2018-0081

- Manoharan, A., Ingrams, A., Kang, D., & Zhao, H. (2020). Globalization and worldwide best practices in E-Government. International Journal of Public Administration, 44(6), 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1729182

- Marsal-Llacuna, M. L. (2016). City indicators on social sustainability as standardization technologies for smarter (citizen-centered) governance of cities. Social Indicators Research, 128(3), 1193–1216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1075-6

- Odountan, E. (2021). Lyon: L’exemple Parfait d’une Ville Intelligente à la Française. Artur In. https://www.arturin.com/lyon-ville-intelligente-a-la-francaise/

- Palvia, S., & Sharma, S. (2007). E-government and e-governance: Definitions/domain framework and status around the world. https://www.academia.edu/6283380/E_Government_and_E_Governance_Definitions_Domain_Framework_and_Status_around_the_World

- Patrão, C., Moura, P., & Almeida, A. (2020). Review of Smart City assessment tools. Smart Cities, 3(4), 1117–1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3040055

- Patterson, M., & Renwick Monroe, K. (1998). Narrative in political science. Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.315

- Peters, B. G. (2018). The politics of bureaucracy. An introduction to comparative public administration. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315813653

- Polkinghorne, D. N. (1988). Narrative Knowing and the human sciences. State University of New York Press.

- Portas, P. (2011). The poetics of politics: Narrative production of national identity in contemporary galicia, 1970-1989. [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Cardiff University.

- Sharifi, A. (2019). A critical review of selected Smart City assessment tools and indicator Sets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 233, 1269–1283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.172

- Sharifi, A. (2020). A typology of Smart City assessment tools and indicator sets. Sustainable Cities and Society, 53, 101936. Article 101936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101936

- Sinclair, A., Peirson-Smith, T., & Boerchers, M. (2016). Environmental assessments in the internet age: The role of e-governance and social media in creating platforms for meaningful participation. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 35(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2016.1251697

- Somers, M. R., & Gibson, G. D. (1994). Reclaiming the epistemological “Other”: Narrative and the social constitution of identity. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Social Theory and the Politics of Identity (pp. 31–99). Blackwells.

- Struver, A., & Bauriedl, S. (2020). Smart City narratives and narrating smart Urbanism. In M. Kindermann & R. Rohleder (Eds.), Exploring the Spatiality of the City across Cultural Texts (pp. 185–205). Springer.

- Windelband, W., & Oakes, G. (1980). History and natural science. History and Theory, 19(2), 165–168. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504797